台灣是否應成立國家主權基金之探討 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) . Abstract Because of global financial crisis since 2007, the financial subcommittee under the Office of the President, Republic of China, addressed the possibility of establishing Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) of Taiwan in 2008, in order to integrate resources in a more efficient way, and to stimulate domestic economy development. However, the comments regarding this issue are. 治 政 controversial and there are few people in Taiwan who understand 大 SWF. 立 ‧ 國. 學. Therefore, the subject of this thesis is to study “if it is appropriate for Taiwan to establish SWF, and the best process to establish SWF if it is”.. ‧. In Chapter II, I will introduce what is SWF. SWF is a government-owned investment. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. vehicle, which has already shown up since 1953 but be only noticed these years due to its. i n U. v. dramatic growth. The importance of SWF is the impacts that SWF brings, including both the. Ch. engchi. good sides (financial stabilization) and the bad sides (exacerbating market volatility and lacking of transparency). Also, the national security issue of the bad impacts and the relative regulation system are the most critical concerns for SWF host countries and recipient countries. In Chapter III, I use six criteria (Background, Funding Purpose, Scale, Source, Investment Policy, and Governance) to analysis six SWFs (GIC, Singapore Temasek, CIC, ADIA, Norway GPF, and KIC); trying to figure out the appropriateness for Taiwan to set up SWF, and the way how to establish if it is appropriate. The result of this analysis is posted in I .

(3) . the end of this study (Chapter IV)--Taiwan definitely has the capability to establish its own SWF, and the whole society will benefit from it: 1.. Background (1) Taiwan holds huge amounts of foreign exchange reserves.. (2) It is hard to find good objectives to invest overseas.. 政 治 大. (3) Taiwan domestic market needs capital injection to stimulate the domestic economy. 立. Funding Purpose. 學. ‧ 國. 2.. (1) Manage foreign exchange reserves more efficiently and seek for better investment. ‧. return; and. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. (2) Inject capital domestically to prompt industry upgrading or transforming; in order. Ch. to stimulate country development.. 3.. engchi. i n U. v. Scale. It should depends on how much does it take for SWF’s investment portfolio, or for the policy of upgrading domestic industry.. 4.. Source. Foreign exchange reserves is the best sources for funding SWF. Considering Taiwan is. II .

(4) . not the member of IMF and may need more foreign exchange reserves against hot money attacks, I use two ways to demonstrate that the foreign exchange reserves is absolutely sufficient as the source for SWF.. 5.. Investment Policy. (1) Put more weights on domestic investments.. 政 治 大. (2) Follow government industry policy, to invest capital in the future blue-chip industry.. 立. ‧ 國. Governance. ‧. 6.. 學. (3) Invest in those industries that Taiwan familiar with or good at.. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. government.. y. (1) Establish another company to manage the assets of SWF which were entrusted by. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. (2) Let external funds managers stand an appropriate proportion in all managers.. (3) Make the specific regulation about Taiwan SWF.. (4) Bottom-up periodic report mechanism and the up-down authorization system.. It is important that the suggestion above can only be done and be implemented by an integrity entity or government. Only when Taiwanese government takes preparation well beforehand, the advantages of SWF can be seen completely. III .

(5) . CONTENT ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ I CONTENT .......................................................................................................................... I FIGURE CONTENT ........................................................................................................II TABLE CONTENT ........................................................................................................ IV I.. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1. II.. LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................3. 立. 政 治 大. WHAT IS SWF? ........................................................................................................ 3. 2.. THE EMERGENCE AND THE GROWTH OF SWF........................................................ 8. 3.. THE INVESTMENT POLICY OF SWFS ..................................................................... 17. 4.. THE IMPACT THAT SWFS BRING ...........................................................................22. 5.. THE MANAGEMENT AND REGULATION OF SWFS .................................................. 30. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 1.. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. III. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................. 41. i n U. v. A. SINGAPORE – GOVERNMENT OF SINGAPORE INVESTMENT CORPORATION (GIC) 44. Ch. engchi. B. SINGAPORE - TEMASEK HOLDINGS .......................................................................... 53 C. CHINA - CHINA INVESTMENT CORPORATION (CIC)................................................ 60 D. NORWAY – GOVERNMENT PENSION FUND-GLOBAL (GPF) .................................... 64 E. ABU DHABI INVESTMENT AUTHORITY (ADIA)........................................................ 71 F. KOREA INVESTMENT CORPORATION (KIC) ............................................................. 74 IV.. CASE OF TAIWAN ................................................................................................ 81. V.. CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................... 93. VI.. REFERENCE .........................................................................................................94 I . .

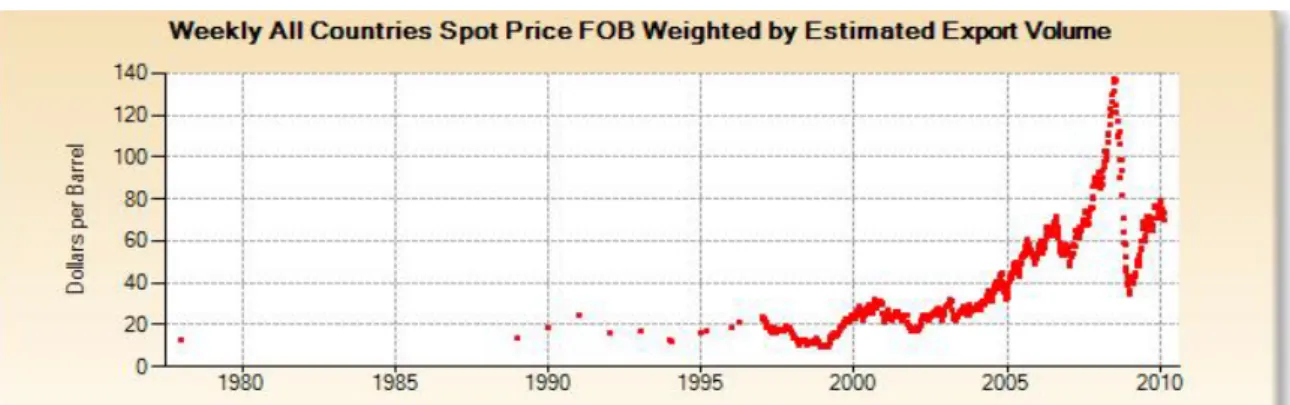

(6) . FIGURE CONTENT FIGURE 1. LAUNCH YEAR OF TOP50 SWFS, % SHARE BY NUMBER ......................................... 9 FIGURE 2. CURRENT ACCOUNT IMBALANCE .......................................................................... 10 FIGURE 3. GLOBAL FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES ............................................................ 11 FIGURE 4. CRUDE OIL PRICE .................................................................................................. 13 FIGURE 5. ASSET COMPARISON-INVESTMENT AND ASSET CLASSIFICATIONS ....................... 14. 立. 政 治 大. FIGURE 6. SWFS MARKET SHARE BY CONTINENT .................................................................. 15. ‧ 國. 學. FIGURE 7. TOP TARGET OF SWFS INVESTMENTS IDENTIFIED BY DEALOGIC (2000-2008) .. 20. ‧. FIGURE 8. SWF INVESTMENTS BY SECTOR............................................................................. 21. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. FIGURE 9. TRANSPARENCY AND INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT .......................................... 28. i n U. v. FIGURE 10. SOVEREIGN WEALTH TRANSPARENCY & INVESTMENT STRATEGY ................... 29. Ch. engchi. FIGURE 11. 4Q09 LINABURG-MADUELL TRANSPARENCY INDEX RATINGS RELEASED ......... 36 FIGURE 12. THREE LEVELS OF INVESTMENT DECISION OF GIC ............................................ 46. FIGURE 13.THE ACTUAL ASSET CLASS DISTRIBUTION OF THE PORTFOLIO AS OF 31 MARCH 2008.................................................................................................................................. 47. FIGURE 14.THE GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE PORTFOLIO AS OF 31 MARCH 2008 .......................................................................................................................................... 48. II .

(7) . FIGURE 15. THE FLOW CHART OF GIC GOVERNANCE ACCOUNTABILITY.............................. 50 FIGURE 16. THE GIC ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE ........................................................... 52 FIGURE 17. PORTFOLIO BY GEOGRAPHY (%) ........................................................................ 55 FIGURE 18. CIC’S ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE ................................................................ 63 FIGURE 19. GPF’S REGIONAL BREAKDOWN OF THE PORTFOLIO ON 31 MARCH 2009 ......... 67. 政 治 大. FIGURE 20. THE DELEGATION RELATIONSHIP OF GPF.......................................................... 70. 立. FIGURE 21. ADIA INVESTMENT PROCESS ............................................................................... 72. ‧ 國. 學. FIGURE 22. ADIA ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE .................................................................. 73. ‧. FIGURE 23. PORTFOLIO WEIGHTING US $ 20 BILLION PORTFOLIO (AS OF DEC. 31, 2008) .. 76. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. FIGURE 24. KIC INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................................................... 78. Ch. i n U. v. FIGURE 25. KIC ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE.................................................................... 80. engchi. FIGURE 26. TAIWAN FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES ............................................................. 85. III .

(8) . TABLE CONTENT TABLE 1. DEFINING THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN: SWFS, SOES, AND PUBLIC PENSION FUNDS ........................................................................................................................ 4 TABLE 2. TOP 10 COUNTRIES BY FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES .......................................... 12 TABLE 3. ESTIMATES OF ASSETS UNDER MANAGEMENT FOR SWFS .................................... 16 TABLE 4. SWFS MAJOR INVESTMENTS IN FINANCIAL INSTITUTES, FROM 2007 TO 2008 ...... 25. 治 政 -M T 大. TABLE 5. PRINCIPLES OF THE LINABURG. 立. ADUELL. RANSPARENCY INDEX ....................... 35. ‧ 國. 學. TABLE 6. LEGISLATION ACTIONS BY DEVELOPED COUNTRIES ............................................... 37. ‧. TABLE 7. GIC’S MAJOR DIRECT FOREIGN INVESTMENTS TILL 2008...................................... 49. Nat. er. io. sit. y. TABLE 8. TEMASEK HOLDINGS’ MAJOR DIRECT FOREIGN INVESTMENTS ............................. 57 TABLE 9. CIC’S MAJOR DIRECT FOREIGN INVESTMENTS (PUBLIC) ....................................... 62. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. TABLE 10. FIXED INCOME PORTFOLIO ON 31 MARCH 2009 BY CREDIT RATING ................... 68 TABLE 11. GPF’S LARGEST EQUITY HOLDINGS ON 31 MARCH 2009 ..................................... 68 TABLE 12. DIRECT FOREIGN INVESTMENT (PUBLIC) ............................................................. 72. TABLE 13. CURRENCIES AND COUNTRIES IN INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS AS OF THE END OF 2008 ......................................................................................................................... 77. TABLE 14. TAIWAN EXCESS FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES VIA GREENSPAN- GUIDOTTI RULE (2009 Q3, UNIT: $BN) .................................................................................... 86 IV .

(9) . TABLE 15. TAIWAN EXCESS FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES UNDER THE CRITERION THAT FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES WITHHOLD SHOULD SUPPORT 6 MONTHS IMPORT VALUE (END 2009, UNIT: $BN) ................................................................................. 87. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. V . i n U. v.

(10) . I. Introduction On Oct. 1st, 2008, the financial subcommittee under the Office of the President, Republic of China, addressed the possibility of establishing Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) of Taiwan in order to integrate resources in a more efficient way, and to stimulate domestic economy development. However, there were controversial comments and discussions regarding this issue. There were many commentators asserting their opinions about the. 政 治 大. appropriateness for Taiwan to establish SWF, and the discussions were becoming more and. 立. more intensive. Thanks to those controversies, SWF became the centre of spotlight for the. ‧ 國. 學. first time in Taiwan.. ‧. Most people in Taiwan do not understand SWF or even have not heard about it before,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. even though SWF, which is the government owned-investment vehicle, was not new. This term has already shown up since 1953. The subject of this thesis is to study “if it is. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. appropriate for Taiwan to establish SWF, and the best process to establish SWF if it is”. At the beginning of this study, it is necessary to review the literature in order to understand SWF clearly. At the beginning of literature review (Chapter II), I will clarify the definition of SWF and its categories. Second, I will introduce the emergence and the growth overview of SWF. Third, I will introduce how SWF operates and illustrate some investment policies. Fourth, I will mention what impact SWF may bring, including both the good sides (financial stabilization) and the bad sides (exacerbating market volatility and lacking of. 1 .

(11) . transparency); at the same time, I will highlight the controversial issue about SWF- the national security issue of the bad impacts. And at the last, I will discuss the relative management and the regulation about SWF. After having a basic understanding about SWF, the case-study method will be used in Chapter III. I will choose some SWFs as examples to demonstrate their characteristics, including their country backgrounds; establishment purposes; funds’ scales and sources;. 政 治 大. investment policies; and the governance. The country backgrounds of some cases mentioned. 立. here are similar to Taiwan, such as Singapore, China, and Korea. On the contrary, some. ‧ 國. 學. country backgrounds are different from Taiwan, such as Norway and Abu Dhabi. Through. ‧. analyzing each SWF thoroughly, it is aimed to gain some valuable information and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. experiences as references for Taiwanese government if SWF is eventually established. At the end of this study, in Chapter IV, I will come back to the main purpose of this. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. study—whether it is appropriate for Taiwan to establish SWF. In this chapter, I will analyze the circumstances around Taiwan to see if there are any advantages for Taiwan to set up SWF. Also, I will indicate what crucial elements that should be considered if Taiwan decides to set up its own SWF. These elements will be the characteristics used in cases: country backgrounds; establishment purposes; funds’ scales and sources; investment policies; and the governance. Ultimately, I hope this study can provide the Taiwanese government some advices for better decision making, and furthermore, to stimulate the domestic economy development.. 2 .

(12) . II. Literature Review 1.. What is SWF?. 1.1. Definitions There are lots of government organizations, international financial institutions, and private researchers publishing research results and reports about SWFs in these years. Those reports have their own definitions of the SWFs. Until now, the definition of SWF is still. 政 治 大. vague. The definition of SWF may vary with the characteristics they have—the investment. 立. policies, the ownership, the accountability, or the investment subjects.. ‧ 國. 學. Some investment banks and private research institutes define SWF as a separate pool of. ‧. government-owned or government-controlled asset that invests in a portfolio with wide range. er. io. sit. y. Nat. of classes and risks.. However, the most accepted definition of SWF is from IMF (February, 29, 2008): SWFs. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. are government-owned investment funds, set up for a variety of macroeconomic purpose. They are commonly funded by the transfer of foreign exchange assets that are invested long term, overseas.1 Lots of people would mix up SWFs with other two sovereign investment vehicles, State Owned Enterprises (SOE) and Public Pension Funds. As Table 1 shows, the key differences are (1) the ownership and controller of SWF is government, but SOE and Pension Funds. 1. Mark Allen and Jaime Caruana, “Sovereign Wealth Funds—A Work Agenda”, IMF, February 29, 2008, 4-5 3 . .

(13) . aren’t; and (2) the sources of SWF are from commodity or non-commodity exports, but SOEs are from earnings, and Pension Funds are from contributions. Table 1. Defining the difference between: SWFs, SOES, and Public Pension Funds2 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Source: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. ‧ y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. To summarize those various definitions, in my opinion, SWF is a large pool of capital. v. n. with 4 characteristics: (1) owned by sovereign government, (2) funded for the purpose of. Ch. engchi. i n U. national interests, (3) mostly sourced by excess reserves and revenues from international trade surplus, and (4) invests in wide range of subjects with different classes and risks with long term investment horizon.. 1.2. The Categories of SWFs There are several categories for the SWF. The most common method to classify SWF is 2. Sovereign Wealth Fund Institutes. http://www.swfinstitute.org/research/investmentvehicles.php 4 . .

(14) . based on two criteria: one classification is used according to the resource of the funds (Kimmitt, 2008) and the other is used according to the SWFs’ purposes or policies.. Classification by Sources According to the classification cited by Kimmitt, the SWFs can generally be divided into two categories according to the source of the foreign exchange assets: Commodity SWFs and Non-commodity SWFs.. 立. (1) Commodity SWFs. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Commodity SWFs are funded by commodity exports that are either owned or taxed by. ‧. the government (Kimmitt, 2008). This kind of funds serves different purposes, like fiscal. sit. y. Nat. revenue stabilization, balance-of-payments, and intergenerational saving3. Because of the. n. al. purpose of fiscal stabilization. er. io. current extended rise in commodity prices, many funds were initially established for the. v i n orCbalance-of-payments h e n g c h i U sterilization. have evolved into. intergenerational savings funds. Typical examples of this type of SWFs are the SWFs funded by oil-exporting countries, like Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. (2) Non-commodity SWFs Non-commodity SWFs are typically established through transfers of assets from official. 3. Here, an intergeneration saving is a saving from selling natural nonrenewable resources by older generation, which used to share with the younger generation in case of running out of nonrenewable resources. 5 . .

(15) . foreign exchange reserves (Kimmitt, 2008). Non-commodity exporters with large amounts of balance-of-payments surpluses can take advantage of these huge “excess” foreign exchange reserves, transfer them to stand-alone investment funds to be managed, and chase for higher returns. Typical examples of this type of SWFs are some Asia exporting countries, like China Investment Corporation in China and Khazanah National Berhad in Malaysia.. 立. Classification by Purpose. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. SWFs can also be classified into several types according to the purpose or the dominant. y. sit er. io. (1) Stabilization funds. Nat. relevant reports4.. ‧. objectives they serve. The followings are five types of SWFs that are commonly accepted in. al. n. v i n Stabilization funds are set up C by countries with abundant h e n g c h i U natural resources in order to insulate the budget and economy from volatile commodity prices (e.g., usually oil prices). For those countries with abundant natural resources, establishing stabilization funds can help to smooth fiscal revenue or sterilize foreign currency inflows. These funds build up assets during the years of ample fiscal revenues to prepare for leaner years. (2) Savings funds Savings funds, or intergeneration funds, are established to share wealth across . 4. IMF, ”Global Financial Stability Report”, October 2007,p 46 6 . .

(16) . generations. For countries with rich natural resources, setting savings funds can transfer non-renewable assets into a diversified portfolio of international financial assets. Thus, they can provide wealth for future generations, or take advantage of wealth on other long-term objectives. Therefore, they can reduce the impacts of running out of non-renewable resource in the future. (3) Reserve investment corporations. 政 治 大. Reserve investment corporations are usually established as a separate entity. Its purpose. 立. is either to reduce the negative cost-of-carry of holding reserves or to pursue investment. ‧ 國. 學. policies with higher returns. Usually, the assets in this type of arrangements are still counted. ‧. as reserves.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. (4) Development funds. Development funds are set up for country development. These funds allocate resources. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. for funding priority socioeconomic projects, such as infrastructure. (5) Pension reserve funds Pension reserve funds have identified pension or contingent-type liabilities on the government’s balance sheet. Sometimes, the development funds and Pension reserve funds can be considered as subsets of SWFs that are linked to long-term fiscal commitments. Other purposes may include enhancing the transparency in managing revenues from commodity exports and fiscal policy. In practice, SWFs have multiple purposes or gradually. 7 .

(17) . changing objectives when situations change. For example, some countries establish SWFs for savings and stabilization purposes, but when the circumstances change, the purpose they emphasis may also change (e.g., change to development funds). This is especially true for countries that export natural resources.. 2.. The emergence and the growth of SWF. 政 治 大 The first SWF recognized in the modern era can be traced back to the 1950s. In 1953, 立. ‧ 國. 學. the Kuwait Investment Board was set up with the aim of investing surplus oil revenues to reduce the country’s reliance on its finite oil resources (Steffen Kern, 2007)5. In 1965, it was. ‧. sit. y. Nat. replaced by the Kuwait Investment Office (KIO), a subsidiary of the Kuwait Investment. n. al. er. io. Authority (KIA). Today, KIA organization manages a substantial part of the Future. i n U. v. Generation Fund (FGF), which allocates 10% of the country’s (Kuwait) oil revenues annually.. Ch. engchi. The second SWF was established by is British colonial administration in the Gilbert Islands (the Republic of Kiribati since 1979) in 1956, the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund (RERF). This fund was set up to hold royalties from phosphate mining in trust for the Pacific island state. It is the major source of revenues for the country and well diversified with investments overseas. Since its inception, assets under management by RERF have 5. Steffen Kern, “Sovereign wealth funds-state investments on the rise”, Deutsche Bank Research, September 10, 2007, p.4 8 . .

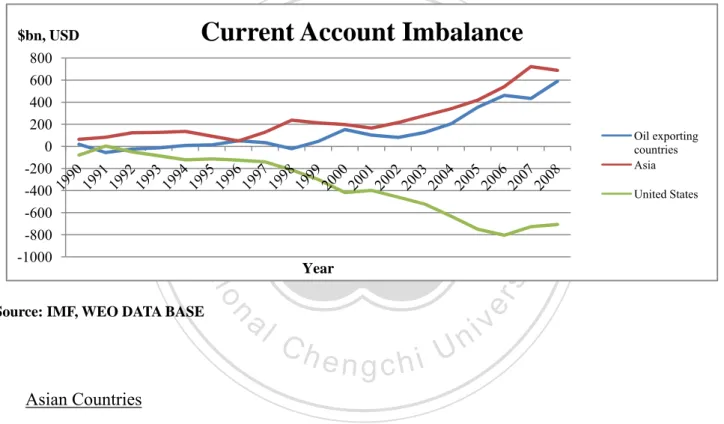

(18) . grown to nine times of Kirbati’s GDP (AUD 636 millions) and returned investment income of around 33% of GDP (Steffen Kern, 2007). After these first two funds were established, the SWFs have been set up essentially in two major waves (Steffen Kern, 2007). The first one is in the 1970s, (e.g., the Singapore’s Temasek Holdings in 1974 and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, ADIA, in 1976), and the second one began since 1990s with setting up of Norway’s Government Pension Fund-Global.. 政 治 大. However, the massive increasing trend of SWFs is from 2000. According to International. 立. Financial Service London (IFSL) research (Figure 1), there are 56% of top 50 SWFs which. ‧ 國. 學. set up between 2000~2009. The fact behind this phenomenon is the current account. ‧. imbalance between main developed countries and developing countries.. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. Figure 1. Launch year of top50 SWFs, % share by number6 . Ch. i n U. Pre‐1990 27%. engchi. 2000‐2009 56%. v. 1990‐1999 17%. Source: International Financial Service London (IFSL) Research. As Figure 2 shows, the current account deficit of U.S.A. has been increasing since 1991; what the worse is that the deficit was more than 800 billion dollars in 2006, or 6% of. 6. “Sovereign Wealth Funds 2010”, International Financial Service London (IFSL) Research, March 2010, p3 9 . .

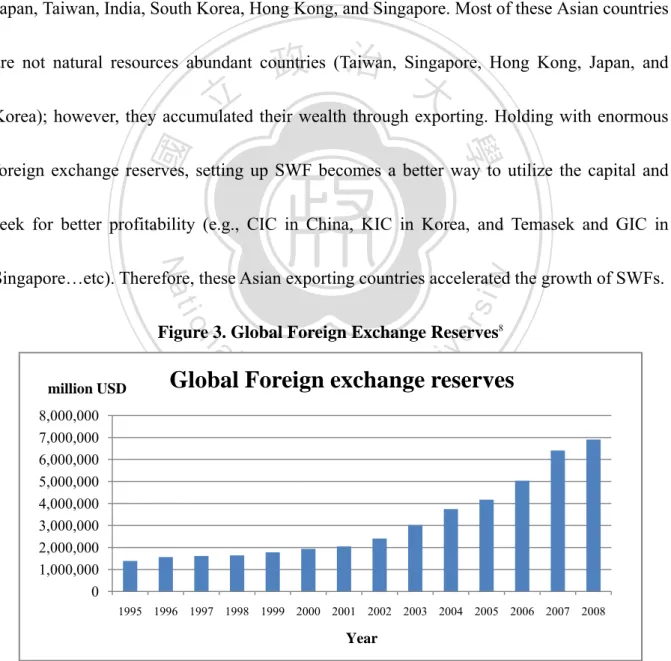

(19) . American GDP. This huge deficit would be a serious worry for America, and also reflect the increasing current account surplus in Asia and oil-exporting countries. Therefore, due to holding with huge current account surplus, Asian countries and oil-exporting countries have lots of incentives to take advantage of it, and these countries became the main forces to stimulate the fast growing of SWFs. Figure 2. Current Account Imbalance7 $bn, USD 800 600 400 200 0 -200 -400 -600 -800 -1000. Current Account 政 治Imbalance. 大. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. United States. Year. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Source: IMF, WEO DATA BASE. Oil exporting countries Asia. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Asian Countries As Figure 3 shows, the global foreign exchange reserve has been increasing more than three times since 2000, and it almost reached 7000 billion dollars at the end of 2008. This phenomenon is important because the distribution of these foreign exchange reserves is very concentrate to Asian countries. 7. IMF, WEO DATA BASE. Asian countries are China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Oil exporting countries are Saudi Arabia, Russia, Norway, Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Nigeria, and Algeria. 10 . .

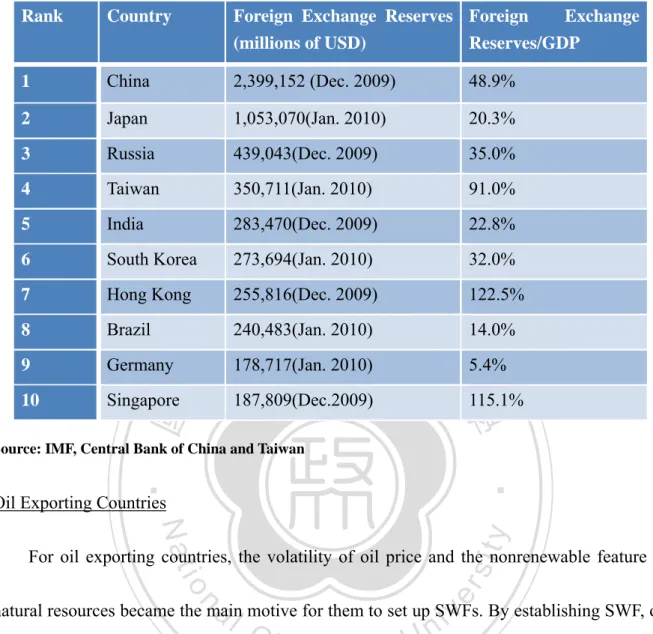

(20) . Table 2 shows the top 10 countries with foreign exchange reserves. It is obvious that China and Japan are the 1st and the 2nd biggest countries holding with foreign reserves (2,399,152 million dollars and 1,053,070 million dollars respectively); Hong Kong and Singapore have the huge percentages of foreign exchange reserves relative to their GDP (122.5% and 115.1% respectively); and 7 of top 10 countries are Asian countries: China, Japan, Taiwan, India, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Most of these Asian countries. 政 治 大. are not natural resources abundant countries (Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, and. 立. Korea); however, they accumulated their wealth through exporting. Holding with enormous. ‧ 國. 學. foreign exchange reserves, setting up SWF becomes a better way to utilize the capital and. ‧. seek for better profitability (e.g., CIC in China, KIC in Korea, and Temasek and GIC in. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Singapore…etc). Therefore, these Asian exporting countries accelerated the growth of SWFs. Figure 3. Global Foreign Exchange Reserves8. al. n. v i n Ch Global Foreign e n gexchange c h i U reserves. million USD 8,000,000 7,000,000 6,000,000 5,000,000 4,000,000 3,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 0. 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008. Year Source: IMF, COFER DATA. . 8. IMF, COFER DATA BASE 11 . .

(21) . Table 2. Top 10 countries by foreign exchange reserves9 Rank. Country. Foreign Exchange Reserves Foreign Exchange (millions of USD) Reserves/GDP. 1. China. 2,399,152 (Dec. 2009). 48.9%. 2. Japan. 1,053,070(Jan. 2010). 20.3%. 3. Russia. 439,043(Dec. 2009). 35.0%. 4. Taiwan. 350,711(Jan. 2010). 91.0%. 5. India. 283,470(Dec. 2009). 22.8%. 6. South Korea. 273,694(Jan. 2010). 32.0%. 7. Hong Kong. 255,816(Dec. 2009). 122.5%. 8. Brazil. 240,483(Jan. 2010). 14.0%. 9. Germany. 10. Singapore. 政 治 大 立178,717(Jan. 2010). ‧ 國. 115.1%. 學. 187,809(Dec.2009). 5.4%. Source: IMF, Central Bank of China and Taiwan. ‧. Oil Exporting Countries. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. For oil exporting countries, the volatility of oil price and the nonrenewable feature of. v. natural resources became the main motive for them to set up SWFs. By establishing SWF, oil. Ch. engchi. i n U. exporting countries have more investment choices; they can reduce their reliance on nonrenewable natural resources and stabilize their national income from volatile oil price. As Figure 4 shows, the world crude oil price had been increased dramatically since 2000, and reached the highest price is $137.11 per barrel in July 2008. Hence, oil exporting countries accumulated lots of national wealth during this period and make use of this capital for setting up SWFs. This raise of oil price boosted the rapid growth of SWFs. . 9. IMF, The people’s bank of China, Central Bank of R.O.C.(Taiwan) 12 . .

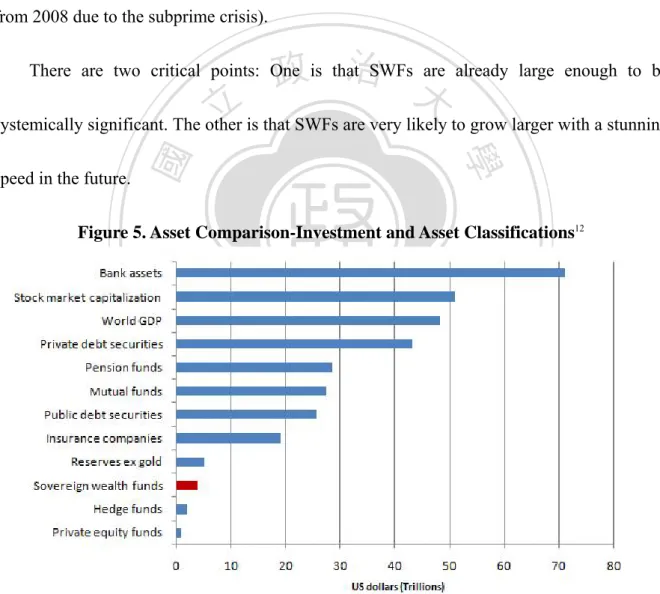

(22) . Figure 4. Crude Oil Price10 . Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration. 政 治 大. Since last decade, what attracted the world’s attention about the SWFs was the. 立. anticipated rate of growth. The combined heft of SWFs is currently estimated to be $3.9. ‧ 國. 學. trillion in 2009, or between 1 and 1.5 percent of global asset markets. They have grown at an. ‧. annual rate of 24 percent over the past five years. The persistence of global macroeconomic. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. imbalances and the inelastic demand and high price of oil lead many analysts to predict an. v. n. annual 20 percent growth rate over the next decade. The total valuation could range in size. Ch. engchi. i n U. from $9 trillion to $16 trillion by 2015, or close to 4 percent of global asset markets. (Daniel W. Drezner, 2008)11 Whether this size is large or small depends on what it is compared with. Figure 5 shows the comparison among SWFs and other assets. If one wants to make SWFs appear large, one can compare SWFs’ scale to those of Pension Fund and Private Equity Fund. That will be. . 10. U.S. Energy Information Administration Daniel W. Drezner, “Sovereign wealth funds and the (in)security of global finance”, Journal of International Affairs, Fall/Winter 2008, Vol. 62, No.1.,p 116 . 11. 13 .

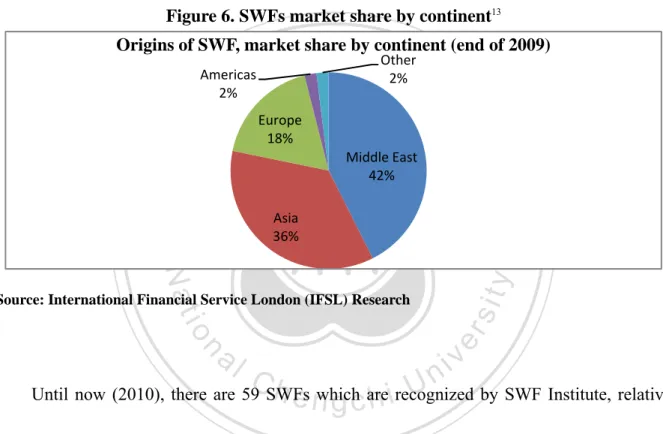

(23) . $3~$3.9 trillion with SWFs compares to estimated $1.7 trillion with Hedge funds, and $0.7 trillion with Private Equity Fund (IFSL estimate, 2009). On the contrary, if one wants to make SWFs to appear small, one can compare the number with other figures, like the world’s GDP (which is around $48 trillion); or note that the $13.9 trillion is only a fraction of the global financial assets, which are roughly $140 trillion in March, 2009($50 trillion reduction from 2008 due to the subprime crisis).. 政 治 大. There are two critical points: One is that SWFs are already large enough to be. 立. systemically significant. The other is that SWFs are very likely to grow larger with a stunning. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. speed in the future.. Figure 5. Asset Comparison-Investment and Asset Classifications12 . n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: SWF Institute. As Figure 6 shows, till the end of 2009, Middle East countries and Asian countries hold . 12. SWF Institute, http://www.swfinstitute.org/research/assetcomparison.php 14 . .

(24) . over three-quarter of global SWFs’ market share (42% and 36% respectively). This distribution means the economic status change is happening now. For the past years, developed countries had always played a dominant role in the world economic growth; however, the developing countries are becoming more and more powerful and influential since they hold the huge capital- SWFs. Figure 6. SWFs market share by continent13 Origins of SWF, market share by continent (end of 2009) Americas 2%. Europe 18%. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 2% 政 治Other 大. Middle East 42%. ‧. Asia 36%. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Source: International Financial Service London (IFSL) Research. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Until now (2010), there are 59 SWFs which are recognized by SWF Institute, relative only 35 SWFs as 2008. Table 3 indicates the estimates of assets under management for main SWFs. The top 3 SWFs are all funded from oil revenues; the biggest is ADIA of UAE, which is about 16.5% of global SWFs scale; the second biggest is SAMA Foreign Holdings of Saudi Arabia, which is 11.4% of global SWFs scale; and the third one is GPFG of Norway, which is 10%. SWFs in China, Singapore and Hong Kong are funded from foreign exchange reserves;. 13. “Sovereign Wealth Funds 2009”, International Financial Service London (IFSL) Research, March 2010, p3 15 . .

(25) . CIC of China is 7.6% of global SWFs scale; the GIC in Singapore is 6.5%; Temasek Holding is 3.2%, and Hong Kong Monetary Authority IP is 3.7%. Kuwait and Russia are 5.3% and 4.4% respectively. These SWFs (with assets more than 100 billion dollars) gain over 68% of global SWFs assets, and most of them are developing countries, or say, oil-exporting countries and south-east Asian countries.. 政 治 大 Name of Fund 立. Table 3.Estimates of Assets Under Management for SWFs14 Assets ($ bn). Source. Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA). Saudi Arabia. SAMA Foreign Holdings. Norway. Government Pension Fund-Global. China. China Investment Corporation. Singapore. Government of Singapore Investment Corporation. Kuwait. Kuwait Investment Authority. Russia. Russia National Welfare Fund & Oil Stabilization Fund. Hong Kong. Hong Kong Monetary Authority Investment Portfolio. Singapore. Temasek Holdings. Libya. Libyan Investment Corporation. 70. Oil. Qatar. Qatar Investment Authority. 65. Oil. Australia. Future Fund. Algeria. Revenue Regulation Fund. 47. Oil. Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan National Fund. 38. Oil, Gas, Metals. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. UAE. n. er. io. Ch. sit. y. Nat. al. engchi U. v ni. IMF, “Sovereign Wealth Funds—a work agenda”, February 29, 2008; SWF Institute 16 . . Oil. 433. Oil. 380. Oil. 288.8. Non-commodity. 247.5. Non-commodity. 202. Oil. 168. Oil. 139.7. Non-commodity. 122. Non-commodity. 49.3. 14. 627. Non-commodity.

(26) . Brunei. Brunei Investment Agency. 30. Oil. Korea. Korea Investment Corporation. 27. Non-commodity. UAS(Alaska). Alaska Permanent Fund. Malaysia. Khazanah Nasional Berhad. 25. Non-commodity. Iran. Oil Stabilization Fund. 23. Oil. Chile. Pension Reserve & Social and Economic Stabilization. 26.7. 21.8. Oil. Copper. Fund Source: IMG, SWF Institute. 政 治 大 To make a summary about立 the emerging and growth of SWFs: SWFs had been existed in. ‧ 國. 學. the world since 1950s, but it grew dramatically only during these years (from 2000) due to. ‧. the increasing oil price and current account imbalance. The SWFs assets scale are estimated. sit. y. Nat. to 3.8 trillion in the end of 2009, and over 68% of SWFs are composed of (1) natural. n. al. er. io. resources abundant countries (oil-exporting countries) and (2) exporting countries (Asian. Ch. i n U. v. developing countries). The distribution of origin countries of SWFs, the government-owned. engchi. feature of SWFs, and the fast growth rate of SWFs, make it more and more important and grab the world’s attention.. 3.. The Investment policy of SWFs. Generally speaking, the governments usually invest their foreign exchange reserves in safe, low return and low risky portfolio, such as Government Bonds (T-Bond). However,. 17 .

(27) . SWFs have different investment attitude even though they are owned by government as well; they can endure more risks and they want to seek better profits. Because SWFs lack transparency, we cannot know exactly the investment policy of each SWF, but we can sum up some common characteristics of SWFs’ investment activities. Typically, SWFs (1) adopt a long term investment horizon; (2) use low leverage; (3) have higher risk tolerance; (4) have wide range distribution of portfolio; and (5) choose the investment target which can satisfy. 政 治 大. their funding purposes or national interests; (6) seek higher expected returns than central. 立. bank foreign currency reserves (John Gieve, 200815).. ‧ 國. 學. Nevertheless, SWFs have considerable freedom with their assets allocation; hence, these. ‧. features may differ significantly according to each SWF’s different purpose, objectives, and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. constraints. Take stabilization SWF as example (e.g., oil stabilization SWFs), the purpose of these SWFs is to reduce the impact of short term national liquidity and financing needs (e.g.,. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. capital shortage); therefore, they will adopt long term investment horizons. According to Drezner (2008), the returns of 53 SWFs equity purchases from 1989 to 2008 indicated that on average SWFs’ two-year abnormal returns amounted to negative 41 percent. And McKinsey Global Institute also estimates that as of July 2008, SWFs had collectively lost $14 billion from recent investment in the financial sector.16. . 15. John Gieve, “Sovereign Wealth Funds and Global Imbalance”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2008 Q2, p196 16 Daniel W. Drezner, “Sovereign wealth funds and the (in)security of global finance”, Journal of International Affairs, Fall/Winter 2008, Vol. 62, No.1.,p 123 18 .

(28) . Investment Target For investment target aspect, SWFs are used to investing overseas, and putting lots of focuses on finance region; besides, the investment attitude was more passive. But this situation has been changing in recent years since the financial crisis in 2007, which hit the performances of SWFs badly. Due to the financial crisis, SWFs became more cautious when doing investment activities. Investments trends of SWFs have been changing in these years. 政 治 大. and recent transactions suggested that the acquisition would become smaller and more diverse in the coming years.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. First, SWFs usually invest overseas, especially focused on developed countries, but. ‧. currently, they invest domestically. SWFs are used to taking control of companies through. y. Nat. er. io. sit. cross-border mergers and acquisitions or acquiring monitory stakes; such investments totaled $187 billion between 1995 and July 2008 (IFSL 2009), and over half of them were in finance. n. al. sector.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Figure 7 indicates that America is the major target of SWFs investments ($48,006.00 million dollars), over 44% of top 10 investment targets; and United Kingdom is the 2nd one ($16,115.53 million dollars), 15% of top 10 investment targets. But since sub-prime crisis, (1) developed countries tightened their capital invested in developing countries (most of them are SWFs countries), and (2) SWFs experienced significant losses from investing foreign companies; the investment trends had gradually changed. SWFs in some oil-exporting. 19 .

(29) . countries have switched their focuses from the Western markets to their domestic markets recently. They invested more SWFs in domestic market as a way to inject liquidity domestically and help to revive their local economies. Second, the target sector of SWFs investment activities was finance, but since the sub-prime crisis, they changed the weights of investment targets. As Figure 8 shows, it was 62% that SWFs invest in finance sector in 2008, but this proportion decreased to 42% in 2009;. 政 治 大. and SWFs put more weights on other targets such as Services.. 立. Figure 7. Top Target of SWFs Investments Identified by Dealogic (2000-2008)17 . ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: United states Government Accountability Office. 17. “Sovereign Wealth Funds”, United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) Highlights, September, 2008, 34 20 . .

(30) . Figgure 8. SWF F Investmeents by secttor18 . 政 治 大 Strategiic Asset Maanagement (SAA) ( of SW WFs 立 Source: Internationa I l Financial Seervice Londoon (IFSL) Ressearch. ‧ 國. 學. Strrategic asseet allocationn (SAA) refflects the fu und’s returnn objective, risk toleran nce, and identifieed constraiints (such as investm ment horizo on, financinng and liqquidity neeeds, and. ‧. sit. y. Nat. regulatoory requirem ments). Theere are two major considerations that t play a ccritical role guiding. n. al. er. io. the alloocation and distributionn of SWFs assets. a One is the accum mulation annd withdraw wal rules. i n U. v. regardinng the fundd’s future caash flows where w appliicable. The other is thhe fund’s ob bjectives (IMF, 2007). 2. Ch. engchi. Thherefore, different typees of SWFss can have different SAA S decisiions to mattch their differennt needs abbout the coonstraints annd purposees. For exam mple, SWF Fs in oil-prroducing countriees may inveest in assetss which are negative co orrelation too oil prices, like energy y stocks, to reduce the variance of govvernment revenue. Tak ke stabilizaation funds for instancce, these funds are a generallly more conservative about theirr SAA deciision (shortt-term invesstments) 18. “Soveereign Wealth Funds 2009””, Internationaal Financial Service S Londoon (IFSL) Research, March h 2009 & 2010 21 .

(31) . since they are typically designed to insulate the trade shocks and to meet contingent financing requirements. Under this consideration, they have to satisfy the safety and liquidity requirement first, and this requirement results the conservative SAA decision. Take savings funds as the opposite example, this type SWFs are more likely to have long-term objectives, and may be better able to accommodate short-term volatility in asset returns. To summarize, the information of investment policies of SWFs are limited, but we can. 政 治 大. come up to some common features: SWFs (1) have long term investment horizon; (2) use low. 立. leverage; (3) have higher risk tolerance; (4) have wide range distribution of portfolio; and (5). ‧ 國. 學. choose the investment target which can satisfy their funding purposes or national interests; (6). ‧. seek higher expected returns than central bank foreign currency reserves. However, according. y. Nat. different needs about the constraints and purposes.. n. al. 4.. Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. to different purposes of different SWFs, each SWF has its different SAA decision to match its. i n U. v. The Impact that SWFs bring. One of the reasons why SWFs play a more and more critical role and attracted everyone’s attention in global market is the impacts they bring. The influence followed by SWFs can be roughly divided into two angles, advantages and disadvantages. Just like a good quote from French journalist Christian Chavagneux: “Like Janus, sovereign funds have a double face. Like the Roman god, they look 22 .

(32) . simultaneously to East and to the West. It is said that his reign was peaceful and that he was a god of peace. But specialists do not forget to recall that he was also the guardian of the gate of hell. (Chavagneux 2008: 12: translation)19”.. Advantages (1) Financial Stabilization. 政 治 大 in global financial markets. First, 立 due to the long-term investment strategy of SWFs, they Lots of commentators emphasize the key function that SWFs bring, the stabilizing role. ‧ 國. 學. have no imminent call on their assets. Therefore they can stick to their investment objectives. ‧. longer during the market downturn or even against the market trend. In this point, they can. sit. y. Nat. accommodate the short-term volatility. Second, because of SWFs diversified investment. er. io. allocation, SWFs can dampen the asset price volatility and lower liquidity risk; at the same. al. n. v i n C hglobal market efficiency. time, they can also contribute to greater engchi U (2) Increase global capital liquidity. The capital of SWFs is mainly from trade revenues. Through international trade, the capital flows from developed countries (mostly from U.S.A.) to developing countries (mostly are oil-exporting countries and Asian exporting countries). After that, this capital flows to other countries over the world (mostly are western countries) via SWFs’ investment activities.. . 19. Benjamin J. Cohen, ”Sovereign Wealth Funds And National Security: The Great Tradeoff”, Department of Political Science University of California, August 20,2008, p.6 23 .

(33) . Through this capital flow circle, the existence of SWFs increases the global capital liquidity. At the same time, because of the frequently capital shifting between Middle East (oil-exporting area) and Asia, SWFs would also stimulate the growing of Asian financial market, Middle East and its neighbors (e.g., Egypt and Jordan). (3) Abundant capital injection The growing size of SWFs provides an abundant capital injection. If the capital injects. 政 治 大. into SWFs’ original countries, it can promote domestic economy growth and developments.. 立. On the other side, if the capital injects overseas, this abundant capital played as a Savior role. ‧ 國. 學. to rescue those almost got bankrupt banks and financial institutions. The following table. ‧. (Table 4) arranges the major investments (capital injections to those almost bell-out financial. y. Nat. er. io. sit. institutions from this sub-prime crisis) of SWFs from 2007 to 2008. During this short period (2007 ~ beginning of 2008), at least 5 financial institutes (Blackstone Group, Carlyle Group,. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch) accept capital injection help from SWFs. Without SWFs, the bankruptcy of financial institution from financial crisis would even worse.. 24 .

(34) . Table 4. SWFs major investments in financial institutes, from 2007 to 200820 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: United states Government Accountability Office. 20. “Sovereign Wealth Funds”, United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) Highlights, September, 2008, p44,45 25 . .

(35) . Disadvantages (1) Exacerbating market volatility With large size and vague investment purpose, SWFs are just like a knife with two blades. Without the accountability to publish their investment strategies and objectives, they can alter their SWFs purposes and change their structures sharply for any reason, and this action may lead to exacerbate market volatility in some assets price. In other words, they. 政 治 大. have the potential to cause market disturbance by shifting amounts of capital from one asset. 立. to another.. ‧ 國. 學. Besides, due to lacking of transparency, SWFs may attract another concern: unfair. ‧. competitiveness of information gathering. For instance, the governments may take advantage. y. Nat. er. io. sit. of the ownership by SWFs to learn how other companies operate, and use this information to bolster rival state-owned enterprises. Another possible situation is that the governments may. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. use SWFs’ advantage to gather information that is not available for normal private companies or investors. (2) National security The national security issue is the most controversial when talking about SWFs. Like private equity funds and pension funds, SWFs have no accountability to publish their information to public, including their SWF’s structure, investment policy, objectives, and investment purpose…etc. But unlike PE funds and pension funds, SWFs are owned by. 26 .

(36) . countries. The “government-owned” characteristic makes SWFs home countries have potential to influence the policies and capabilities of recipient countries. The most direct way can be to get the direct ownership and control the strategic and sensitive industry or critical infrastructure in recipient countries. Practically, the national security concerns are truly considerable. SWF’s home countries have potential to seek strategic interests rather than maximize financial returns through. 政 治 大. investments. As Tonelson (2008) mentioned, “If, for example, the Chinese government held. 立. market-makers, and if our nation’s current period of financial weakness persists, how willing. ‧ 國. 學. would Washington be to stand up to Beijing in a Taiwan Straits crisis?”21. ‧. There are some examples to manifest this political concern. (1) China agreed to buy. y. Nat. er. io. sit. $300 million Costa Rican bonds as an incentive for Costa Rica to drop its diplomatic recognition of Taiwan in favor of China instead; (2) Temasek Holdings’ purchased of the. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. telecom businesses of Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra22; (3) Norway’s SWF has a policy against investment in certain armory manufacturers, and in 2005, that fund sold its stake in Wal-Mart, citing human rights concerns.23 According to Drezner (2008), “there is indeed a strong relationship between SWF. . 21. United States House of Representatives, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission,” Hearing on the Implications of Sovereign Wealth Fund Investment for National Security”, testimony be Alan Tonelson, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., 7 February 2008 22 January 23, 2006, the Shinawatra-family sold its remaining 49.6% stake in Shin Corporation, a leading Thai telecommunications company 23 Anna L. Paulson, “Raising capital: The role of sovereign wealth funds”, Chicago Fed Letter, No. 258, January 2009 27 .

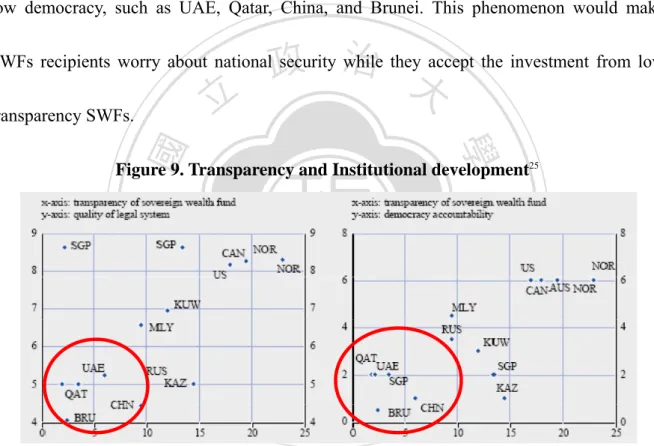

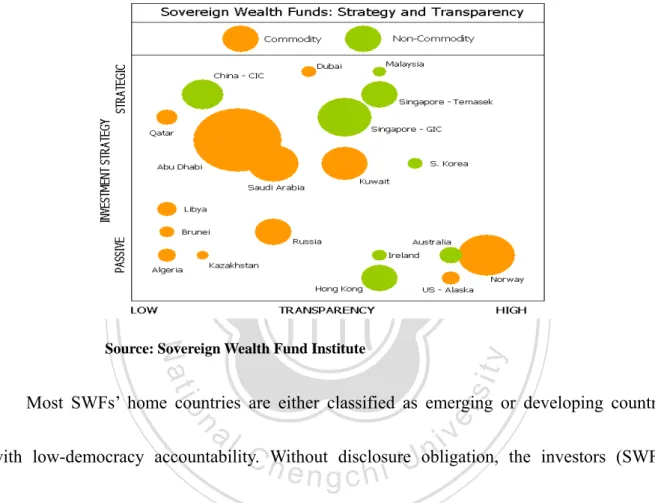

(37) . transparency and the political characteristics of the home country. The transparency of government investment vehicles is closely and positively correlated with the home country’s rule of law and democratic accountability.”24 Figure 9 (Truman 2007) shows the relationship between SWFs’ transparency and home countries’ democracy and quality of legal system. It is obvious that the SWFs with low transparency also have low quality of legal system and low democracy, such as UAE, Qatar, China, and Brunei. This phenomenon would make. 政 治 大. SWFs recipients worry about national security while they accept the investment from low. 立. transparency SWFs.. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 9. Transparency and Institutional development25 . ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: Truman (2007), International, Country Risk Guide. Figure 10 is the coordinate axis which exhibits the top 20 SWFs’ transparency and investment strategies. It is obvious that SWFs in developed countries are more willing to disclose their SWFs’ information. And from this axis, what should be highlighted are those . 24. Daniel W. Drezner, “Sovereign wealth funds and the (in)security of global finance”, Journal of International Affairs, Fall/Winter 2008, Vol. 62, No.1.,p 122 25 Roland Beck and Michael Fidora, “The impact of sovereign wealth funds on global financial markets”, European Central Bank Occasional Paper Series, No 91 , July 2008, p13 28 .

(38) . SWFs in the upper left corner of the location. Those SWFs such as Saudi Arabia, CIC, and ADIA, have more strategic investment policies, but with low-transparency. These SWFs are more easily to trigger political (national security) concerns. Figure 10. Sovereign Wealth Transparency & Investment Strategy26 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. sit. y. Source: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. er. io. Most SWFs’ home countries are either classified as emerging or developing country. al. n. v i n C hWithout disclosureUobligation, accountability. engchi. with low-democracy. the investors (SWFs. countries government) have the potential to invest in some sensitive industries, like energy industry, telecommunications industry, or military industry. On the other hand, the recipient countries may also doubt the “real purpose behind the actions”. For recipient countries, it is a dilemma to accept SWFs. Although they really need SWFs to inject ample capitals into their domestic market; they are worried about exposing their national security under SWFs’ actions. 26. SWF Institute, http://www.swfinstitute.org/research/strategytransparency.php 29 . .

(39) . If the national security concerns cannot be eliminated, it is possible to cause protectionism triggered by recipient countries, especially developed countries. It also makes developed countries fall into a dilemma situation. For decades, the world economic rule is “free market”, that is also what developed countries advocate extremely, but now, the situation reverses. If SWFs really trigger the next national financial protectionism wave, the effect they bring is the overall change of global economic rule in a dramatic way.. 政 治 大. To make a simple conclusion from above, the impacts that SWFs bring can be. 立. 學. Advantage. ‧ 國. generalized as below:. Disadvantage. Exacerbating market volatility. Increase global capital liquidity. National security. Nat. y. ‧. Financial Stabilization. er. io. sit. Abundant capital injection. SWFs can stabilize global financial markets due to their long term investment horizon;. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. increase global capital liquidity via their wide range of investment objectives; provide an abundant capital injection to those in need. However, they may also exacerbate the global financial market to become more volatile since they can change their investment activities without any reasons; trigger the national financial protectionism and national security concerns, as most big SWFs lack transparency about their operation. 5.. The management and regulation of SWFs There is no precise model to manage SWFs now, but there are two regular ways be seen. 30 . .

(40) . One way is to be managed by the central bank directly; the other way is to set up a new investment entity insulated from the central bank to take charge of SWFs. The advantage of setting up SWFs under the central bank is that it can strengthen the function of the central bank. Like HKMA (Hong Kong Monetary Authority), it sets up two different investment portfolios under the central bank; according to different purpose, risk, and horizon, to meet the needs of liquidity and higher investment returns purpose.. 政 治 大. The advantage of setting up an independent investment entity for SWFs is that it can. 立. divide the different roles from the owner of SWFs and the owner of foreign exchange. ‧ 國. 學. reserves strictly. This kind of management can be classified into two types. One is to make a. ‧. special law to regulate SWFs, like what KIC (Koran Investment Corporation) did. Korean. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Congress promulgates Korean Investment Corporation Act to establish KIC aiming to manage their SWF. There are precise regulations in this Act to stipulate how KIC operate.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The other type is to manage SWFs by normal Company Law and be monitored by financial inspection authority, like GIC and Temasek Holdings in Singapore. These two institutions were established by Singapore Ministry of Finance, but their operation is insulated from the government. The government only has the rights to monitor the operation and receive the annual report, but no rights to intervene the companies’ business decisions. Although lots of commentators and recipient countries fear that the national security may be threatened by SWFs’ home countries, there is no direct evidence to proof the SWFs. 31 .

(41) . home countries have the political investment strategy till now. At this moment, the most important thing is to find the balance between western calls for transparency and the funds’ insistence on fair treatment. Not only the recipient countries but also the home countries should step back since that- if SWF is really economically driven, both sides would benefit from the investment activities. Here are some responses and the relative regulations for SWFs.. 5.1. Principles for both sides. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Both SWFs themselves and the countries in which SWFs invest in have responsibility to. ‧. resolve the dilemma. According to Kimmitt (2008), there are 4 principles for recipient. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. countries and five principles for SWFs home countries to achieve this goal.. Principles for recipient country (1) Avoid protectionism. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Countries should not raise counterproductive barriers for investments. No matter the investors have the controlling of national firms or not, erecting the investment obstacle is never a friendly behavior. (2) Uphold fair and transparent investment frameworks Investment policies, processes, and regulations should be public clearly, no vagueness, no discriminating, and should be predictable, especially the rules which relate to national 32 .

(42) . security considerations. (3) Respect investor decisions Recipient countries should respect investors’ decisions. Do not ask investors or intervene how to do their SAA decisions, especially those decisions are relative to investor’s gains and losses. The rights how to allocate the investment objectives should belong to investors. (4) Treat investors equally. 政 治 大. Any relative regulations and laws for investors should not be discriminating, not only. 立. between domestic and foreign investors but also between different foreign investors.. ‧ 國. 學. Principles for home country. ‧. (1) Invest commercially, not politically. y. Nat. er. io. sit. SWFs investment decisions should be purely based on economic consideration rather than political or foreign policy purpose. In order to eliminate recipient countries’ fear,. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. investors should incorporate this principle into their basic investment management policies. (2) Convey world-class institutional integrity Because of SWFs’ huge size and state-owned characteristic, obscure investment policy would raise recipient countries’ worries. Therefore SWFs should be transparent about their investment policies, including their purpose, objectives, governance structure, and internal controls. (3) Compete fairly with the private sector. 33 .

(43) . Since SWFs have more potential to get the competitive advantage information than private entities, they should be careful not to take advantage of this information to erect unfair competing environment. (4) Promote international financial stability As public-sector entities which can benefit from healthy global markets, SWFs have the responsibility to promote the international financial stability. Especially during times of. 政 治 大. financial crisis, SWFs should try to do something to sustain the regular operation of global. 立. 學. ‧ 國. economic market. (5) Respect host-country rules. ‧. SWFs should comply with all regulation established by countries which invest in and. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. co-operate what the host-country rules ask, such as disclosing required information.. Ch. 5.2. Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index. 27. engchi. i n U. v. The Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index was developed by Carl Linaburg and Michael Maduell at the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. This index is a rating system for measuring transparency of sovereign wealth funds. SWFs, as a state-owned investment vehicle, will receive more unethical concerns and suspicions than private investors from public. Therefore, there are calls to make a regulation or rating system aiming at those SWFs with large opaque or non-transparency in order to show their investment intentions. . 27. SWF institute, http://www.swfinstitute.org/research/transparencyindex.php 34 . .

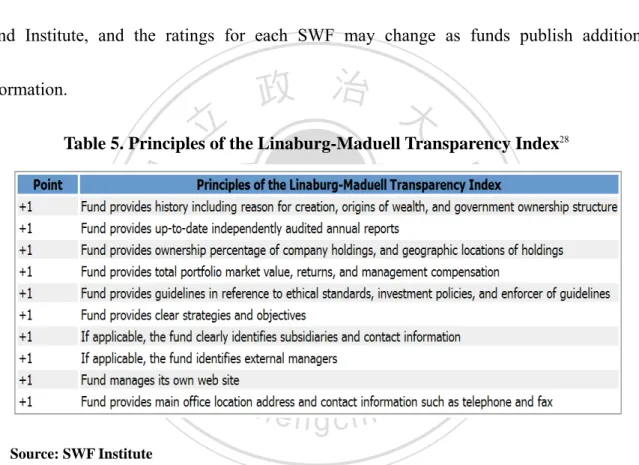

(44) . The index is based on ten principles that illustrate SWFs transparency to the public. Table 5 presents the principles, and each principle adds one point of transparency when calculating the index rating. The minimum rating a fund can receive is a 1, but according to the recommends of Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, the minimum rating to ensure SWFs have adequate transparency is 8. This index is still an ongoing project in Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, and the ratings for each SWF may change as funds publish additional. 政 治 大. information.. 立. Table 5. Principles of the Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index28 . ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: SWF Institute. The following figure (Figure 11) is the latest release (4st quarter in 2009) for LMTI ratings. From the figure, most of the SWFs home countries with grades over 8 are high quality legal system, or high democracy countries. Like Singapore, Ireland, USA, Norway, New Zealand, Canada, and Australian. 28. SWF institute, http://www.swfinstitute.org/research/transparencyindex.php 35 . .

(45) . Figure 11. 4Q09 Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index ratings released29 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: SWF institute. 5.3. Legislation by advanced economies Because of the political fears brought by SWFs and no particular regulation until the publishing of GAPP (Generally Accepted Principles and Practices ) in 2008, many advanced 29. SWF institute, http://www.swfinstitute.org/research/transparencyindex.php 36 . .

(46) . economies issued or revised their laws which are related to foreign investment activities. The most famous is the FINSA (Foreign Investment and National Security Act) promulgated by United States. The United States Congress passed the FINSA in 2007 and its responsibility is to monitor the acquisitions by government-owned entities, mandate the involvement of high-level officials in CFIUS30 , and report to Congress.. 政 治 大. The other developed countries also did some legislative actions to respond. Table 6. 立. collects those legislations issued by France, Japan, Canada, Australia, Germany, and United. ‧ 國. 學. States. Those legislations are established for recipient countries’ national security concerns. ‧. and make precise ordinance for foreign investors.. y. Nat. Oct.2007. Passed FINSA to do the scrutiny of acquisitions by government-owned. al. investments. France. Dec.2005. er. U.S.A. Legislation Description. n. Year. io. Country. sit. Table 6. Legislation actions by developed countries31 . Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Published a new ordinance mandating prior authorization for foreign investments that may affect “national defense interests.”. Japan. Aug.2007. Emended its inward investments regulation to address the words “changed security environment surrounding Japan and trends in international investment activity.”. Canada. Dec.2007. Published “clarifications” of its rules on foreign investment for state-owned enterprises under the Investment Canada Act.. Australia. Feb.2008. Announce six principles that govern reviews of foreign investments by SWFs and other government-linked entities.. Germany. Apr.2008. Published new legislation authorizing policy makers to pre-examine selected foreign investments, especially those coming from SWFs.. Source: Department of Political Science. 30. CFIUS, an interagency body created in 1975, which was led by Treasury Department and its responsibility is to monitor and review incoming investments 31 Benjamin J. Cohen, ”Sovereign Wealth Funds And National Security: The Great Tradeoff”, Department of Political Science University of California, August 20,2008, p.9 37 .

(47) . 5.4. International Regulation Institutes Since there is no particular rule for SWFs actions, international organizations are asked to do something about SWFs regulation. IMF and OECD got a strong pressure from the finance ministers and central bank chiefs of G-7 to identify the “best practices” for all the SWFs players (including both sides). After the summit meeting of the Group of Eight in June 2007, IMF and OECD start trying to develop related guidelines. The IMF would take charge. 政 治 大. of the behavior of SWFs, and the OECD would manage guideline for recipient countries.. 立. The International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IWG) was established in. ‧ 國. 學. a meeting with SWFs countries attended during April 30 to May 1st, 2008. IWG comprises. ‧. representatives from 26 IMF member countries with SWFs, and it would be initiated,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. facilitated and coordinated by IMF. The aim for IWG is to develop a generally accepted principles and practices (GAPP) for SWFs home countries to reflect their investment. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. practices and objectives properly. And finally, the GAPP was published in October 2008 and it became the main and formal principles about SWFs in the world. At the beginning in PART II of GAPP, it indicates that the principles and practices are based on a voluntary code of conduct, and hope to alleviate recipient countries’ fears that SWFs might operate in political purpose. The followings are the simple introduction about the guidelines and purpose of GAPP32: 32. Source are all from “Sovereign Wealth Funds Generally Accepted Principles and Practices- Santiago Principles” 38 .

(48) . Guiding principles of GAPP (1) Help to maintain a stable global financial system and free flow of capital and investment. (2) Comply with all applicable regulatory and disclosure requirements in the countries where the funds invest. (3) Invest on the basic consideration of economic and financial risk and return. (4) Create and maintain a transparent and sound governance structure that provides for. 政 治 大. adequate operational controls, risk management, and accountability.. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Purposes of GAPP. (1) Identify the framework of generally accepted principles and practices that reflect proper. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. on a prudent and sound basis.. sit. governance, accountability arrangements, and the conduct of investment practices by SWFs. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. (2) Help to improve both the recipient and home countries’ understanding of SWFs as economically oriented entities. (3) Stabilize the global financial system, reduce the protectionism, and maintain a stable and open investment surrounding.. Summing up the management and regulation about SWFs; there are two common ways to manage SWFs: one is to set up SWFs under central bank; the other is to establish another independent institution to manage SWFs. The advantage of the prior way is to strengthen the 39 .

(49) . function of central bank; the advantage of the latter one is to divide the different ownership of SWFs’ capital and foreign exchange reserves. With regard to the regulation aspects, there are lots of principles suggested by commentators, and those principles are based on respect, indiscriminate, commercial oriented criteria. Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index was developed by SWF Institute, and the minimum rating to ensure SWFs have adequate transparency is recommended to be over 8. GAPP is the newest and most formal principle. 政 治 大. which is published by IWG. Its purpose is to identify the generally accepted principle about. 立. SWFs; improve the relationship between SWFs’ home countries and recipient countries, and. ‧ 國. 學. stabilize the global financial system.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 40 . i n U. v.

數據

相關文件

During the Sejong era of the fifteenth century in particular, Korean science and technology had reached its climax, thus its accomplishments could reveal themselves clearly in the

To stimulate creativity, smart learning, critical thinking and logical reasoning in students, drama and arts play a pivotal role in the..

To nurture in students positive values and attitudes and enhance their literacy skills development through appreciation of and interaction with literary texts in the junior

The Government also established the Task Force on Promotion of Vocational and Professional Education and Training in April 2018 to evaluate the implementation

In consideration of the Government agreeing to grant a tenancy of the School Premises at a nominal rent to the IMC and providing financial subsidy, assistance and

Since huge quantities of transactions are involved in daily operations of a hotel, the accounting department always has to deal with complicated calculations which undoubtedly

明清兩代, 君主獨攬大 權,君主權力高漲而臣 下權力低落 。明朝太祖 和成祖兩代, 已形成君 主集權之勢;清代則經 康熙、雍正收束權柄 , 君權更高度集中

(1983), Foreign Direct Investment in the United States:Old Currents,New Waves and the Theory of Direct Investment, in Kindleberger etc.The Multinational Corporation in the 1980s,