Quality Management Approaches in

Libraries and Information Services

P

AO-N

UANH

SIEH; P

AO-L

ONGC

HANG; K

UEN-H

ORNGL

UDept. and Graduate Institute of Library and Information Science, National Taiwan University, Taipei; Institute of Business and Management; National Chiao Tung University, Taipei;

Dept. of Industrial Engineering and Management; National Kaohsiung Institute of Technology, Kaohsiung;

Taiwan, Republic of China

The increasing expectations of users for better services have motivated libraries to view quality management as an effect-ive means of incorporating quality improvement into their related services. Effectively implementing quality manage-ment in libraries requires an understanding of applying ap-propriate quality management concepts and techniques.

This article reviews the quality management tools and tech-niques developed over the last five decades and, then, cate-gorises them into three broad approaches. In addition, a framework of quality management approaches and tech-niques is developed and applied to assess and improve the service quality of libraries and information services.

Introduction

The increasing expectations of users have chal-lenged libraries to improve their quality of ser-vices. Limited by increasingly tighter budgetary restrictions, library managers feel more pressure to fully exploit available resources. Therefore, several libraries and information services have adopted quality management practices in recent years. Among the various initiatives imple-mented include ISO 9000 standards (Johannsen 1996), 5S movement (Taipei Municipal Library 1996), and benchmarking (Zairi and Hutton 1995; Garrod and Kinnell 1996; Garrod and Kinnell 1997; Buchanan and Marshall 1996). By adopting quality management, the library’s image and service quality can be improved, and librarians can increase productivity while focusing on the

customer’s needs (Johannsen 1992; Taipei Munici-pal Library 1996).

Quality management has been extensively ap-plied within the manufacturing industry for over a decade. More recently, the service industry has increasingly emphasised this area. The public sector has also put forward major initiatives to improve quality. Closely examining available quality management techniques in service in-dustries and the public sector reveals their ef-fectiveness and positive impact on the customers. Quality management is increasingly integrated into library services, following their perceived success in manufacturing industries, with par-ticular emphasis on improving service quality.

Libraries have developed numerous programs to fulfil user requirements. In general, libraries concentrate mainly on maintaining

administra-Printed in Germany · All rights reserved ____________________________________________

Libri

ISSN 0024-2667

Pao-Nuan Hsieh is Associate Professor at Dept. and Graduate Institute of Library and Information Science, National Taiwan University, 1, Roosevelt Rd., Sec. 4, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China. 106. Fax: (+886) 2-23632859, Tel: (+886) 2-23626582, email: pnhsieh@ccms.ntu.edu.tw

Pao-Long Chang is Professor at Institute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University, 4F, 114, Sec. 1, Chung Hsiao W. Rd., Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China. 100. Fax: (+886) 2-23610656, Tel: (+886) 2-23146515 ext. 305, email: paolong@ cc.nctu.edu.tw

Kuen-Horng Lu is Associate Professor at Dept. of Industrial Engineering and Management, National Kaohsiung Institute of Technology, 415, Chien Kung Rd., Kaohsiung, Taiwan, Republic of China. 807. Fax: (+886) 7-3923375, Tel: (+886) 7-3814526 ext. 7117, email: log@cc.nkit.edu.tw

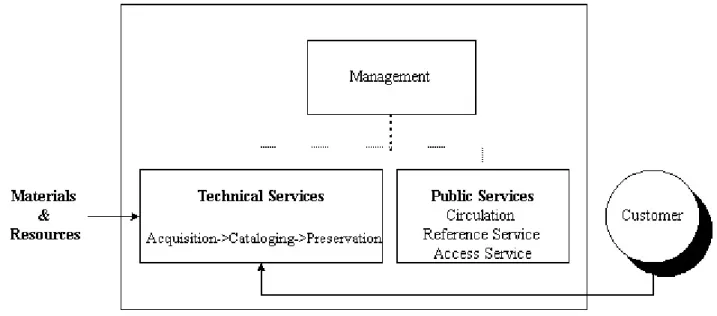

tive activities, building the collection, and serv-ing the users. Therefore, the functions of a library can be broadly categorised as administrative management, technical services and public ser-vices. Administrative management defines the objectives of the library, allocates the resources to achieving such objectives, co-ordinates related activities, and assesses the performance of related services. Technical services largely focus on build-ing the collection and makbuild-ing the collection more accessible for users. The activities of technical services include acquisition, information organisa-tion, and preservation. While all library activities strive to, public services serve the customers most directly. Related activities consist of circula-tion, reference and access service.

Library services can be viewed as an open sys-tem with materials, resources and information needs of customers as input. In other words, the activities involved in providing and using library services are more interrelated than isolated. Fig-ure 1 depicts the interaction within a totally in-tegrated library system. While the library only exists for serving customers, the service delivery system should be user-oriented. Although all functions and activities focus on customers, the direct interaction between library and customers occurs in public services. That is, librarians work-ing in circulation, reference and access service re-spond and translate the customer’s expectations to the technical service department and

adminis-trative management. Depending on the ability of public services to accurately interpret customer requirements, all functions of the library can be directed to satisfying the quality requirements and information needs of customers.

Quality management in libraries and informa-tion services has received considerable atteninforma-tion, with a majority of those investigations describing quality concepts, quality management principles, related processes, and limitations (Jurow and Barnard 1993; O’Neil 1994; Brophy and Coulling 1996). From the perspective of library services, adopting quality programs increases the effective-ness of the library and satisfies increasingly higher customer expectations. Most quality man-agement-related literature is based on experience drawn from industrial organisations, particularly on the manufacturing of tangible products de-livered to the end-user at a later stage. Recent years have witnessed the increasing acceptance of quality management into services-related and non-profit organisations, such as education. De-spite the significant level of adaptation within service organisations and the public sector, there exists missing link between quality management principles/tools and the implementation of quali-ty management in libraries and information ser-vices. Johannsen (1992) foresaw the risk:

... as the general principles of quality control have originally been developed in private sector and industrial

environments, you may expect problems, when you wish to use those principles to manage quality of an intangible resource, information, in organizations, where structures, culture, management style, business strategies and cus-tomers are often very unlike industrial organizations.

Effectively implementing quality management in libraries and information services requires an understanding of the following:

• The unique characteristics of library operations • The nature of interaction between librarians and

cus-tomers

• The making of recommendations on the application of appropriate quality management concepts and tech-niques.

These issues are discussed herein.

Quality management approaches

Quality management approaches can be catego-rised broadly into three stages according to the evolution of management control. Management can implement control before an activity com-mences, while the activity occurs, or after the ac-tivity has been completed. Consequently, three types of control are feedforward, concurrent and feedback (Robbins and De Cenzo 1998). The most desirable type of management control is feed-forward control that is future-directed and takes place in advance of the actual activity. Feed-forward control is advantageous because it allows management to prevent anticipated problems rather than having to cure them later and to avoid wasting resources. Concurrent control, as its name implies, takes place while an activity is in progress. When control is enacted while the ac-tivity is being performed, management can cor-rect problems before they become too costly. The most conventional means of control relies on feedback. The feedback control takes place after the activity. However, a disadvantage of this ap-proach is that the damage will have already occurred by the time that the manager has the in-formation to take corrective actions. Consequently, feedforward control is the most economic ap-proach and can meet the requirement of custom-ers, followed by concurrent control and feedback control, respectively. Interestingly, quality manage-ment approaches developed and applied to as-sess and improve product quality can be related

to types of management control from the per-spective of an open system.

Quality management approaches were origi-nally developed as being product-oriented. Feed-back control, an inspection-based quality control approach, was introduced to detect inferior pro-ducts at the after-production stage. Realising that quality could not be improved by merely in-specting the finished product, subsequent efforts switched the emphasis of quality management from inspection to process control: from feedback control stage to concurrent control stage. The un-derlying premise regarding quality in the con-current control stage is that quality is equivalent to meeting or exceeding customer expectations. Manufacturing products that reflect the diverse needs of customers, is more of a function of good design than of good control of a process. There-fore, quality management has gradually shifted to emphasis on the design phase: from concurrent control stage to feedforward control stage. In the following, we discuss the three approaches of quality management and related techniques.

Quality by inspection

The inspection-based system was perhaps the first scientifically designed quality control system to evaluate quality. The system is applied to in-coming raw materials and parts for use as inputs for production and/or finished products. Under this system, some quality characteristics are ex-amined, measured and compared with required specifications to assess conformity. Therefore, the inspection-based system is a screening process that merely isolates conforming from non-con-forming products without having any direct mechanism to reduce defects.

Reducing the damage to final products, sam-pling plans were developed to control product quality. Although an effective technique, a quality control system based on sampling inspection does not directly achieve customer satisfaction and continuous improvement. Producing fewer defects through process improvement is the only means of reducing defects.

Quality by process control

Defects inevitably add to the production cost and waste resources. Therefore, a business strives for

zero defects. The quality management system based on sampling inspections has been replaced by the approach of continuously improving the process. This concept, as pioneered by Deming, moves from detecting defects to preventing them and continuing with process improvement to meeting and exceeding customer requirements on a continuous basis. The continuous cycle of process improvement is based on the scientific method for addressing problems, commonly re-ferred to as the Deming cycle. Deming’s approach consists of four basic stages: (1) a plan of what to do; (2) do or carry out the plan; (3) study what has done; and (4) act to prevent errors or improve the process. The planning stage consists of study-ing the current situation, gatherstudy-ing data, and plan-ning for improvement. Related activities include (a) defining the process, its inputs, outputs, cus-tomers, and suppliers; (b) understanding customer expectations; (c) identifying problems; (d) testing theories of causes; and (e) developing solutions. In the do stage, the plan is implemented on a trial basis to evaluate a proposed solution and pro-vide objective data. The study stage determines whether or not the trial plan is working correctly and if any further problems or opportunities are identified. In the final stage, act, the final plan is implemented and the improvements become standardised and implemented continuously. This process then returns to the plan stage for further diagnosis and improvement (Evans and Lindsay 1996).

The Deming Cycle can enhance communica-tion between the staff involved and help employ-ees to use the wheel to improve processes. Some of the specific tools used to improve processes are control charts, process capability studies, seven (quality control) tools, seven new (quality man-agement) tools, and seven creativity tools (GOAL/ QPC 1997). However, the appropriate tools must be applied for the specified purpose. For ex-ample, cause-and-effect diagrams and process flow charts could be more appropriate during the planning stage of the Deming wheel, whereas control charts may be most appropriate during the stage of checking (Rahman 1995).

Quality by design

The Deming approach shifted the focus of quality management a step back from inspection to

pro-cess control. The approach of quality by design makes a further step back from process to design. By definition, Quality by design implies that quality must be built in early in the development and design stage. By doing so, the final product can satisfy the customers. Two important tech-niques for designing quality products are quality function deployment (QFD) and Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA).

Quality function deployment is a structured approach that: (a) identifies and ranks the rel-ative importance of customer requirements; (b) identifies design parameters (or engineering characteristics) that contribute to the customer requirements; (c) estimates the relationship be-tween design parameters and customer require-ments and among different design parameters; and (d) sets target values for the design param-eters to best satisfy customer requirements. A QFD matrix (or house of quality) is frequently used to translate prioritised customer require-ments into identifiable and measurable product specifications and engineering requirements to reduce functional variation and costs, thereby facilitating the decision-makers in making design-related decisions. Many investigators have suc-cessfully applied QFD in product and service design (Guinta and Praizler 1993; Armstrong 1994; Pitman et al. 1996; Lam and Zhao 1998).

Failure Mode and Effect Analysis is a methodi-cal approach to examine a proposed design for possible ways in which failure can occur (Juran 1989, 1993). FMEA consists of (a) identifying and listing modes of failure and the subsequent faults; (b) assessing the probability of these faults; (c) assessing the probability that the faults are detected; (d) assessing the severity of the con-sequences of the faults; (e) calculating a measure of the risk; (f) ranking the faults on the basis of the risk; (g) attempting to resolve the high-risk problems; and (h) verifying the effectiveness of the action by using a revised measure of risk (Gil-christ 1993). In addition to providing preliminary information on reliability prediction, product and process design, FMEA helps engineers identify potential problems in the product earlier, thereby avoiding costly changes or reworks at later stages (Teng and Ho 1996).

Closely scrutinising quality management re-veals that many techniques are based on ex-perience derived from manufacturing tangible

products. Whether or not quality management practices can be transferred to a service industry delivering intangible services has received con-siderable attention. Many investigators confer that (a) the service and manufacturing industries differ in terms of the characteristics of quality, (b) different criteria must be used for measuring these industries, and (c) the focus of quality man-agement is rather different than similar (King 1987; DelMar and Sheldon 1988; Kackar 1988; Mitra 1993). The final manufacturing products can be measured objectively, while the quality can be managed by output control. Meanwhile, the deliverables of services are frequently in-tangible, which is difficult to measure objectively. In addition to the simultaneously delivery and consumption of services, the quality certainly cannot be managed by either output control or process control.

Brophy and Coulling (1996) indicated that with the broad applications in the service sector, the sector has come to the recognition that some as-pects of quality management must be approached somewhat differently in the service industry. The most distinguishing characteristic between serv-ice and manufacturing industries is that in the former, there is usually a direct interaction be-tween the customer and the service. Libraries and information services have intensive direct inter-action and also indirect contact with the custom-ers. Because of the immediacy of the interface, libraries must develop their own framework when integrating quality management approaches into libraries.

Framework of quality management approaches

in libraries

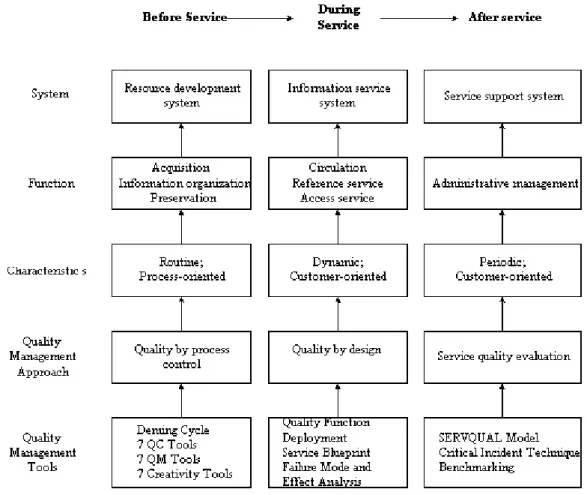

Having different characteristics, library services require special approaches of quality manage-ment that go beyond the simple adoption of manufacturing techniques for a product. Quality management related to library functions can be viewed in three phases: before service, during service, and after service. Library services ulti-mately focus on satisfying the information needs of customers. Before services are provided, the technical service departments should have re-quired books and information resources collected and value-added to enhance their value to the customers. Therefore, the customer-oriented

li-brary should regard technical services as resource development system to ensure that every cus-tomer has resources properly acquired, organ-ised, displayed or accessed. Having direct contact with customers, the public services should be regarded as information service delivery system and focus on providing information to customers accurately, promptly, and responsively to help customers solve problems, and build up custom-ers’ knowledge and ultimately enhance their productivity. Administrative management should be regarded as the service support system to co-ordinate and allocate resources as well as provide support for technical services and public services to satisfy customers’ needs, and to evaluate serv-ice performance periodically and to continuously improve service quality. Figure 2 shows the quali-ty management approaches and techniques as-sociated with the stages of service delivery in libraries.

Resource development system

Largely concerning itself with backstage activi-ties, a resource development system is the off-line preparation for public services and has no direct contact with customers. For services in which the customer need not be present, the service trans-action can be de-coupled and standardised. For example, acquisition is considered to be a cus-tomised service. Convenient access to Web-accessi-ble public access catalogue (webpac), however, has weaned customers from present interaction with live librarians to interaction via online pur-chase request and, consequently, only routine or-der preparation and communication is required. Most activities related to technical services have technical and procedural standards to follow, accounting for why each function is characterised by a high routine and process-orientation. Inter-national or domestic rules govern the catalogu-ing, classification, and information organisation. In addition, standardised practices also exist for acquisition and preservation, e.g. how order re-quests are to be formulated and transmitted. In fact, many practices in technical services are standardised by actual work routines and for-malised based on a detailed and systematic study during library automation. Therefore, the quality management of a resource development system should emphasise the concurrent control of

pro-cess to ensure that all books and resources have been accurately collected, accessed and value-added appropriately. Quality by process control is the best quality management strategy for a re-source development system.

Deming’s PDSA cycle, together with the seven quality control tools, the seven quality manage-ment tools, and the seven creativity tools can be applied in technical services to improve service quality.

The PDSA Cycle (or “the Deming cycle”), as shown in Figure 3, is focused on satisfying cus-tomer needs. This requires an attitude of putting the customer first and a belief that this principle is the object of one’s work. Implicit in the Deming PDSA approach is that improvement in quality results from continuous, incremental turns of the wheel (Brophy and Coulling 1996).

Seven simple tools − cause-and-effect diagrams, run charts, scatter diagrams, flowcharts, Pareto diagrams, histograms and control charts − have

been termed the Seven Quality Control Tools (7QC tools) by the Japanese (Johannsen 1992;

Figure 2: Framework of quality management approaches in libraries

Jurow 1993; Brophy and Coulling 1996; GOAL/ QPC 1996). In the early 1970s, as Total Quality Control expanded to service and administrative areas, it became clear that the 7QC tools were not always appropriate. So, the seven new QC tools or the seven management tools – affinity dia-grams, interrelationship digraphs, tree diadia-grams, matrix diagrams, prioritisation matrixes, process decision program charts, and activity network diagrams – were developed under the leadership of Nyatanni (GOAL/QPC 1996). Among these the affinity diagram is a tool for organising lan-guage data. After ideas are brainstormed and written on cards, they are grouped together with similar ideas. A header card is created which captures the meaning of each group of ideas. This is a creative, right brain, activity. The Seven Crea-tivity Tools are problem definition, brainstorm-ing, brainwritbrainstorm-ing, creative brainstormbrainstorm-ing, word and picture association, advanced analogies, and the morphological chart (GOAL/QPC 1996).

While the original seven QC tools are oriented towards the analysis of quantitative data, the sev-en managemsev-ent tools and sevsev-en creativity tools are designed to handle unstructured, verbal in-formation in group-base problem-solving or de-cision-making processes (Johannsen 1992; GOAL/ QPC 1996). All these tools can be used separately or complementarily. For example, the acquisition department can use control chart to evaluate the performance of dealers, and build partnership with the best dealer. The serial department can use the cause-and-effect diagram not only to an-alyse the causes of missing issues but also use relation diagrams to control the order status of critical serials to ensure the completeness and promptness of serials collection. In addition, the Pareto diagram can be used in the cataloguing department to collect the data on bibliographic verification and copy cataloguing for further an-alysing the feasibility of enhancing productivity and shortening the processing time.

Information service system

The information service system is a service de-livery system that has direct contact with custom-ers. In circulation, access and reference services, the customer often serves as the co-producer and works with the librarians and the library system to produce a final product which enhances

knowl-edge, skills, or promotes the enjoyment of leisure activities. The service encounter is always initiated by the customer. Therefore, the major function of an information service system is dynamic and customer-oriented. Because of direct interaction with public service librarians, customers require the service to be done right the first time and to be consistent every time. Consequently, quality by design is the best quality management strategy for information service system. Quality manage-ment tools that can be applied are quality func-tion deployment, failure mode and effect analysis, and service blueprinting which is specially de-signed for effectively managing the service en-counter.

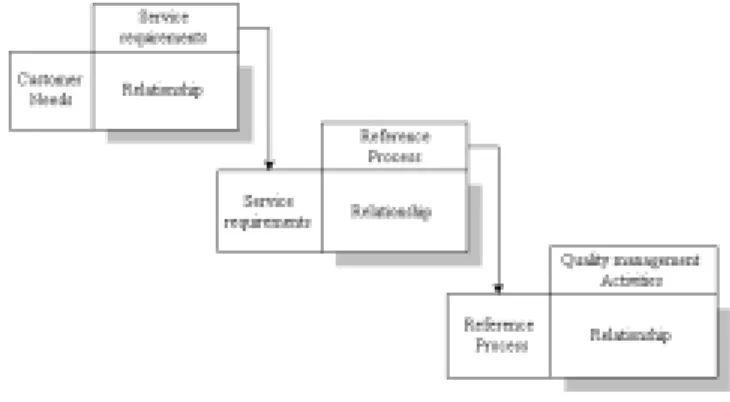

Reference service has direct encounters with customers, and the service quality depends highly on the performance of the reference librarians and their interactions with customers. Therefore, the design of reference service can adopt the tech-niques of quality function deployment. Chang and Hsieh (1996) proposed a modified frame-work of quality function deployment for refer-ence service, as shown in figure 4. There are four phases to facilitate communicating service quirements from the customer to the activities re-lated to quality management of reference service delivery. The first phase is to identify the cus-tomer’s needs and requirements. The second phase is to define the service requirements and design the co-service system so that the right quality is built in from the very beginning of service design. The third phase consists of pro-cess planning which is a matter of selecting the co-service process “best” producing what the customer needs. Phase four involves the plan-ning of the quality management activities. It

phasises translating reference processes into quality management activities in order to ensure quality both before and during the reference en-counter.

The first task of applying QFD to reference services is to identify customer needs, which are descriptions in the customer’s own words of the benefits they want the reference services to pro-vide. The opinions posted on the library web site or BBS (Bulletin Board System), customer com-plaints, records of reference interviews, previous user studies, and so on, will all contribute to the list of customer needs. In reference services, the primary customer needs might be categorised as “good employees,” “right answers” and “nice en-vironment.” In order to manage the customer needs, the primary needs need to be structured into a hierarchy. For example, the primary need for “good employee” might be elaborated as “good attitude” and “good skills” in serving cus-tomers. And the “good attitude” is subdivided into “kind and polite,” “does not have to wait,” “assists users in looking up information,” and “properly dressed.” Each customer need is, then, to be met in terms of professional terminology – that is, service requirements. For example, the words “kind and polite” express the customer’s concept, but librarians need these words trans-lated into their vocabulary in order to actually build a service delivering standards and quality management activities. In delivering reference service, “kind and polite” may be described in terms of the responsiveness, approachability, attentiveness, and courtesy. The service require-ments of reference services translated from cus-tomer needs might be grouped into answer, process, and environment, using an Affinity Dia-gram. For example, the quality of answer might be evaluated according to two perspectives – re-sults and sources. And the quality of source might be evaluated according to the indicators of credibility, acceptability, accessibility and avail-ability. After the service requirements have been identified and prioritised, the most important requirements must be linked to reference process to design the co-service system to satisfy the cus-tomer needs.

Circulation and access service is the major con-tact between the customer and the library, and is usually the starting point for customers to use all other library services. With information networks,

most customers can remotely access the webpac or search networked databases. After identifying the availability of certain books or documents, the customer is physically present in the library to check out those books or photocopy the re-quired documents. If the collection or documents needed by the customers are unavailable, the customers can also apply for an interlibrary loan or document delivery service. Encounters between the customer and library are integral and con-tinuous, with each customer possibly encounter-ing many points of services and interactencounter-ing with varying service facilities and librarians. There-fore, the circulation and access service should be designed by integrating all of the service points to provide seamless services to customers.

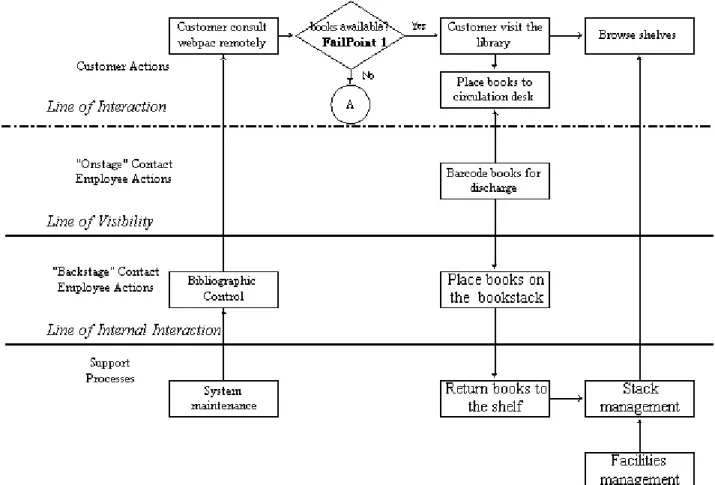

The service blueprint is a customer-focused service process analysis tool (Shostack 1987). Fig-ure 5 gives an (incomplete) example of a typical service blueprint for access service. A service blueprint is a detailed map or a flow chart of the service process. However, creating a flow chart can only depict the workflow of internal opera-tions from the perspective of the librarian. Such a flow chart neither provides understanding of the interaction between the librarian and the custom-er; nor can it integrate these encounter points with related activities that support these encoun-ters. Therefore, the concepts of “line of interaction” and “line of visibility” are used in a service blue-print to improve service encounters. Consequently, the service delivery process can be simultaneously viewed from the perspectives of the librarian and the customer. The line of interaction differentiates actions performed by the customer from actions performed by the librarians. Customer actions are placed above the line. Actions performed by the librarians (regardless of whether they are by access services librarians or by mechanical or automated means) are located below the line. These actions are charted on the service path pro-ceeding from left to right. Along the line of interaction, the encounter points, i.e. the points in the service process where the customer receives the access services, can be easily specified. The line of visibility in a service blueprint distin-guishes those processes that are visible to the cus-tomer from those that are behind the scenes. This concept facilitates the understanding of the inter-connection between “below-the-line” and “above-the-line” service processes and the recognition

that the latter processes where the customers’ ex-periences directly depend on the former processes that customers do not experience (Shostack 1984; Kingman-Brundage 1989; George and Gibson 1991; Chang and Hsieh 1998).

The blueprinting exercise also provides librari-ans with opportunities to identify potential fail points (for example, books unavailable by cus-tomer) and, then, use the failure mode and effect analysis to design “foolproof” procedures to avoid such an occurrence, thereby ensuring the delivery of high-quality services.

The purpose of failure mode and effects analy-sis is to identify all the ways in which a failure can occur, to estimate the effect and seriousness of the failure, and to recommend corrective de-sign actions. An FMEA usually consists of specify-ing the followspecify-ing information for each critical component: failure mode (how the component can fail), cause of failure, effect on the product or system within which it operates (safety, down-time, repair requirements, tools required),

correc-tive action, and comments (Dale, Boaden, Wilcon and McQuater 1998).

Service support system

The performance of a customer-oriented library should be evaluated on the basis of quality and quantity. Quantitative evaluation in terms of out-put measure is the basic element of a statistical report, which is mainly prepared for account-ability not for improving service. Meanwhile, customer satisfaction significantly contributes to improving service quality. Based on the evalua-tion results, the service support system should allocate resources to those services that custom-ers deem as having low satisfaction. In practice, the SERVQUAL model, critical incident tech-niques and benchmarking can be used to evaluate and improve service quality in library services.

Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985) de-veloped a multiple-item scale called SERVQUAL for measuring the five dimensions of service

quality (i.e. reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy, and tangibles). A score for the quality of service is calculated by computing the differences between the ratings that customers assign to paired expectation and perception of each of twenty-two statements. This instrument has been designed and validated for use in a variety of service encounters. In addition, many investiga-tors have adapted the SERVQUAL measures to evaluate the service quality of libraries (White and Abels 1995; Chang and Hsieh 1996; Nitecki 1996; Rowley 1996; Coleman et al. 1997).

Critical incident techniques can be used to an-alyse the service encounters between the customer and librarians. Customers and employees are interviewed separately to describe their experi-ences of the service experience. By doing so, the cause of success or failure of the service en-counter can be analysed; the critical factors of service encounters can be identified as well. Cor-respondingly, staff training and development courses can be designed to enhance the capacity of librarians and library instruction. Moreover, information literacy programs can be designed to equip the capacity of customers (Radford 1996, 1999).

For every quality dimension, some organisa-tions (not just libraries) have earned the reputation of being “best in class” and, thus, a benchmark for comparison. Benchmarking, however, volves more than comparing statistics. It also in-cludes visiting the leading organisation to learn firsthand how such outstanding performance has been achieved (Garrod and Kinnell 1997; Robert-son and Trahn 1997).

Conclusion

Manufacturing-based models and techniques for managing quality may be unproductive unless a clear understanding of the particular nature of the service sector is used to re-focus the model and select an appropriate set or sequence of tools or techniques. This article presents a novel frame-work for incorporating quality management into library and information services. All libraries can select the appropriate techniques for their pro-gram with the framework dimensions proposed herein.

Quality management approaches and tech-niques can help libraries, but do not always

guarantee the outcome. Libraries wanting to con-tinuously improve their service quality and com-pletely satisfy customers must create a customer-oriented culture in their organisation. First, a framework of total quality management must be established for the library by promoting a quality culture before applying any particular technique. The techniques must be considered as an integral part of the total quality system. Importantly, man-agers must identify and suggest appropriate methods by analysing issues such as organisa-tional culture, competence, skills, missions, and accessibility of resources and information. Above all, what is required is the support and com-mitment of senior management to make the ap-plication of these approaches and techniques meaningful and useful.

References

Armstrong, B. 1994. Customer focus – obtaining cus-tomer input. In Total Quality Management in Li-braries. Rosanna M. O’Neil, ed. Englewood, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited.

Brophy, P and K. Coulling. 1996. Quality Management for Information and Library Managers. London: Aslib Gower.

Buchanan, H.S. and J.G. Marshall. 1996. Benchmarking reference services: step-by-step. Medical Reference

Services Quarterly 15 (Spring): 1–13.

Chang, P.L. and P. N. Hsieh. 1996. Using quality function deployment to improve reference services quality. Journal of Library Science 11: 65–96.

Chang, P.L. and P. N. Hsieh. 1996. Evaluating univer-sity libraries’ service quality: from user’s point of view. Bulletin of the Library Association of China 56: 49–68. [Text in Chinese.]

Chang, P.L. and P. N. Hsieh. 1998. Managing quality in access services through blueprinting. Presented at International Symposium on Decision Sciences, Hong Kong, June 13.

Coleman, V., B. Chollett, L. Bair and Y. Xiao. 1997. Toward a TQM paradigm: using SERVQUAL to measure library service quality. College & Research

Libraries 58 (May; 3): 237–45.

Dale, B., R. Boaden, M. Wilcox and R. McQuater. 1998. The use of quality management techniques and tools: an examination of some key issues. International

Journal of Technology Management 16 (4/5/6): 305–25. DelMar, D. and G. Sheldon. 1988. Introduction to

Quality Control. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing. Evans, J.R. and W.M. Lindsay. 1996. The Management

and Control of Quality. 3rd

ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing.

Garrod, P. and M. Kinnell. 1997. Benchmarking devel-opment needs in the LIS sector. Journal of Information

Science 23 (2): 111–18.

Garrod, P. and M. Kinnell. 1996. Performance meas-urement, benchmarking and the UK library and information services sector. Libri 46 (3): 141–8. George, W.R. and B. E. Gibson. 1991. Blueprinting: a

tool for managing quality in service. In Service Quality: Multidisciplinary and Multinational Per-spectives, ed. Stephen W. Brown and others. New York: Lexington Books.

Gilchrist, W. 1993. Modeling Failure modes and effects analysis. International Journal of Quality & Reliability

Management 10(5): 16–23.

GOAL/QPC Research. 1996. 7 QC tools, 7 MP tools, 7 creativity tools. GOAL/QPC Research Page. On-line. Internet. [4/8/2000]. Available WWW at URL: http: //www.goalqpc.com/RESEARCH/

Guinta, L.R. and N. C. Praizler. 1993. The QFD Book. New York: American Management Association. Johannsen, C.G. 1992. The use of quality control

principles and methods in library and information science: theory and practice. Libri 42 (4): 283–95. Johannsen, C.G. 1996. ISO 9000-managerial approach.

Library Management 17 (5): 14–24.

Johannsen, C.G. 1996. Quality management and in-novation: findings of a Nordic quality management survey. Libri 45 (September/December; 3/4): 131– 44.

Juran, J.M. and F. M. Gryna. 1993. Quality Planning and Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Juran, J.M. 1989. Quality Control Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jurow, S. 1993. Tools for measuring and improving performance. Journal of Library Administration 18 (1/2): 113–26.

Jurow, S. and S. B. Barnard, ed. 1993. Integrating total quality management in a library setting. New York: Haworth Press.

Kackar, R.N. 1988. Quality planning for service in-dustries. Quality Progress, 21 (8): 39–42.

King, C.A. 1987. A framework for a service quality assurance system. Quality Progress 20 (9): 27–32. Kingman-Brundage, J. 1989. The ABCs of service

sys-tem blueprinting. In Designing a Winning Service Strategy. Chicago: American Marketing Associa-tion.

Lam, K. and X. Zhao. 1998. An application of quality function deployment to improve the quality of teaching. International Journal of Quality & Reliability

Management 15 (4): 389–413.

Mitra, A. 1993. Fundamentals of Quality Control and Improvement. New York: Macmillan.

Nitecki, D.A. 1996. Changing the concept and measure of service quality in academic libraries. Journal of

Academic Librarianship 22 (May; 3): 181–90.

Parasuraman, A., V. A. Zeithaml and L. L. Berry. 1985. A conceptual model of service quality and its im-plications for future research. Journal of Marketing 49 (Fall): 41–50.

Parasuraman, A, V. A. Zeithaml and L. L. Berry. 1988. SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of

Retailing 64 (Spring; 1): 12–40.

Pitman, G, J. Motwani, A. Kumar and C. H. Cheng. 1996. QFD application in an educational setting: a pilot field study. International Journal of Quality and

Reliability Management 13(4): 99–108.

Pritchard, S.M. 1995. Library benchmarking: old wine in new bottles? Journal of Academic Librarianship 21(6): 491–6.

Radford, M.L. 1996. Communication theory applied to the reference encounter: an analysis of critical in-cidents. Library Quarterly 66(2): 123–37.

Radford, ML. 1999. The reference encounter: interper-sonal communication in the academic library. Chi-cago: Association of College and Research Libraries. Rahman, S. 1995. Product development stages and as-sociated quality management approaches. The TQM

Magazine 7(6): 25–30.

Robbins, S.P. and D. A. De Cenzo. 1998. Fundamentals of Management: Essential Concepts and Applica-tions. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inter-national.

Robertson, M. and I. Trahn. 1997. Benchmarking aca-demic libraries: an Australian case study. Australian

Academic and Research Libraries 28 (June; 2): 126–41. Rowley, J. 1996. Managing quality in information

ser-vices. Information Services & Use 16 (1): 51–61.

Shostack, G.L. 1984. Designing services that deliver.

Harvard Business Review (January–February): 133–9. Shostack, G.L. 1987. Service positioning through struc-tural change. Journal of Marketing 51 (January): 34–43. Taipei Municipal Library. 1996. Improving service

image: the how-to-do-it manual. Taipei, Taiwan: Taipei Municipal Library. [Text in Chinese]

Teng, S.H. and S. Y. Ho. 1996. Failure mode and ef-fects analysis: an integrated approach for product design and process control. International Journal of

Quality & Reliability Management 13 (5): 8–26.

White, M.D. and E. G. Abels. 1995. Measuring service quality in special libraries: lessons from service mar-keting. Special Libraries 86 (Winter; 1): 36–45.

Zairi, M. and R. Hutton. 1995. Benchmarking: a process-driven tool for quality improvement. The TQM