英語教學研究所碩士論文

A Master Thesis Presented to Institute of TESOL,

National Chiao Tung University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master of Arts

在英文為外國語言之情境下教師回應對學生寫作修正之影響

The Influence of Teacher Response on Students’ Revision

in an EFL Setting

研究生:李秋芸 Graduate: Chiu-Yun Li 指導教授:郭志華 教授 Advisor: Prof. Chih-Hua Kuo

中華民國 九十七 年 一 月 January, 2008

論文名稱:在英文為外國語言之情境下教師回應對學生寫作修正之影響 校所組別:國立交通大學英語教學研究所 畢業時間:九十六學年度第一學期 指導教授:郭志華教授 研究生:李秋芸

中文摘要

由於外語學習的熱潮與各國國際學生的日益增加,第二外語寫作(Second Language Writing)在過去數十年間已迅速發展。就英語而言,許多第二外語寫作的理論除了源自 於母語寫作(First Language Writing)的概念,同時也自行發展出許多更適合英語為外 國語言(EFL)之學習者的理論與教學法。此外,由於「過程導向」(Process Approach) 的寫作觀點廣被寫作研究學者與寫作教師們所推崇與採用,近十年的寫作流程也由過去 重視單篇文章中修正文法錯誤之練習方式,轉變成現在的先協助學生透過組織文章內容 充份表達自己的想法後,再專注於用字等語言文法錯誤的更正,期許透過多次修改 (Revision)的過程,讓學生可以提升真正寫作能力。 因此,許多第二外語寫作專家專注於探究教師回應(Teacher Response)在學生寫 作與修改過程所扮演的角色與其影響力。許多研究顯示,教師回應的模式對學生在文章 的內容上有幫助;然而,教師回應對學生在文法更正與掌握上的效果似乎還尚未定論。 而這些研究教師回應的文獻中,其研究對象皆為大專程度之學生,鮮少專文探究語言程 度較低的高中生。也因此,本研究著重於教師回應對高中生在英文寫作與寫作修改上的 影響。 本研究旨在探究兩種教師回應的方式施用在兩組各二十名的台灣高中生之影響,並 且藉由各組在英文寫作與修改上的表現、回顧報告(retrospective protocol)、問卷與訪 談等方式,針對這兩種書面回應方式的影響作量化與質化的分析探討。實驗組接受以問 題 為 主 的 回 應 方 式 ( Question-based TR ); 對 照 組 則 接 受 直 接 修 改 的 回 應 方 式 (Direct-correction TR)。這兩種書面回應皆包含針對文法錯誤的回應(grammar-focusedTR)與針對文章內容安排的回應(content-focused TR)。就文法部份,本研究僅探討學 生在時式上的錯誤;就內容組織上,本研究著重於學生文章是否含有主旨句(thesis statement)。 結果顯示,教師回應對學生寫作之修正有立即性的效果:兩組學生在修正版的文章 中文法錯誤皆明顯下降。然而,在面對主旨句的使用,接受教師提問的實驗組表現不如 對照組好。對另一研究問題,即教師回應在學生修正版本中的影響力是否持續至另一篇 新文章中,本研究發現無論實驗組或對照組,大多數的學生在新文章中都出現文法錯誤 增加的現象,對於主旨句的掌握亦有退步的現象;而這兩種退步的現象尤以接受直接修 改的對照組為嚴重。詳細分析每位學生的三篇文章、回顧報告、問卷與訪談,我們得知 多數學生沒有進步主要是在書寫新文章的時候相當粗心大意而非不懂應該使用何種時 式,因此在以簡單式的時式項目錯誤最多。此外,多數學生對英文寫作中「主旨句」的 概念似乎仍無法通盤理解與確切掌握,顯示中文缺乏時式與時態的使用與不大需要主旨 句的寫作風格影響了這群英語為外國語言的學習者。 雖然教師回應的持續影響效果在本研究中不明顯,絕大多數學生在問卷中表示對各 自所得到的教師回應則持肯定的態度,認為自己在這三次寫作經驗中學到一些東西,同 時也指出有試圖從教師回應中所學到的知識應用於新的文章之中。此外,學生的回顧報 告也讓本研究深入地探討學生對教師回應之看法與態度,較為特殊的發現為:實驗組對 教師的提問有較多的意見與反駁,而對照組對於教師的直接修改都完全接受。這反映了 以提問為主的教師回應讓學生有更多的思考空間,此外,提問也讓學生對個人錯誤較有 警覺。 最後,透過這四十位高中學生對這三次寫作流程與教師回應的意見,期能帶給高中 教師們有更多寫作教學上的想法與應用,也能為同領域的研究學者們在未來的研究上有 更多的參考與建議。

ABSTRACT

The development of second language writing has boomed with the wide spread of foreign language learning and the increasing number of international students over the last decades. In English, many L2 writing theories originate from L1 writing theories but meanwhile more theories and methods have been developed and adapted for EFL learners. In this decade, with the advocacy of process approach by writing researchers and teachers, students’ writing procedure has changed, from focusing on error correction in a single draft to focusing on content and organization first and then on grammar in multiple drafts. This process-oriented approach, by means of revising, is expected to improve students’ composing competence.

As a result, many L2 writing researchers have investigated the influences of teacher response (TR) on students’ writing and revising processes. A large number of studies have shown that TR is of help to content development while the effectiveness of the TR on students’ mastery of grammar and error correction seems unfixed. What is more, most research targeted students at the college level, but few studies have investigated students at the lower level such as senior high school students. Therefore, the present study aims at examining the influences of TR on senior high school students’ revision and subsequent writing.

The purpose of this study is to analyze two types of TR employed for two groups of students quantitatively and qualitatively via students’ writing performances over three drafts, retrospective protocols, questionnaires, and interviews. The experimental group received question-based TR and the control group received direct correction as TR. Both types of TR include grammar-focused TR on tense usages and content-focused TR on the use of a proper thesis statement.

have lower error ratios in the revision. However, in terms of the use of a thesis statement in an essay, students receiving question-based TR do not perform as well as those receiving direct correction. In addition, the immediate effect of the TR on the revision does not sustain in the new essay: in both groups, most students show more errors in tense usages in the new essay; their ability to use a thesis statement regresses as well, particularly in the direct-correction group. Students’ carelessness when they are writing contributes a lot to the increasing error ratios in the new essay. Besides, many students have difficulty using an appropriate thesis statement for their essay, suggesting the use of a thesis statement may be difficult for students at this level. This implies possible first language interference—there is no clear use of tense and aspect in Mandarin and no necessity of using a thesis statement in a Chinese essay.

Although the carry-over effect of the TR is not significant in this study, a majority of the students show a positive attitude towards the TR they receive, pointing out in the questionnaire that they learn something from the TR and also try to apply what they have learned from the TR to the new essay. Furthermore, students’ retrospective protocols also reveal students’ different reactions to TR. Those who receive TR in the form of a question have more opinions or disagreements while those who are given direct-correction TR tend to revise their drafts simply following the TR. This suggests that question-based TR gives students more opportunities to think over their problems and that asking questions may help student raise their consciousness of their own errors and problems.

Finally, the findings from this study, and opinions proposed by the participants in this study should render senior high school teachers useful pedagogical implications and provide L2 writing researchers with insightful suggestions for further research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

What a joyful event! This “masterpiece” was finally born! Without the support and encouragement from so many beloved people around me, this thesis research is definitely unable to be undertaken so smoothly. Now, I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to those who have helped me during my graduate studies and the accomplishment of this master thesis.

First, I would like to thank Prof. Chih-Hua Kuo (郭志華教授), my advisor, with my genuine affection. She is not only a knowledgeable scholar but also a respectable mentor. She always respects my research interests and provides possible directions for me to explore while I was wandering. She is absolutely a professional writing teacher. It is she that brings me to the academic writing realm where I relearn the core of English writing, review many useful writing theories and practice what I have learned in the past three years. Learning from her, I am amazed at the power of her critical and logical thinking; tutored by her face to face, I am marveled at the way she organizes an essay coherently and cohesively. And most of all, her warming encouragement always cures my frustration owing to the repeated failures to write the academic genre. I really learn a lot from this honorable teacher not only in her earnest attitudes but also her reasonable persistence. Thank you very much, my dearest advisor, Prof. Kuo.

Besides, I also want to show my gratitude to Prof. Yi-Chih Sun (孫于智教授) and Prof. Po-Sen Liao (廖柏森教授). Prof. Sun in my proposal reminded me of something I’d never noticed. The suggestions from both the two professors in my oral defense further help me revise my thesis and make this thesis qualified. In addition, I would also like to thank Prof. Ching-Fen Chang (張靜芬教授), the first teacher I was instructed by after I transferred to this department. I was inspired in almost every of her class, thus becoming more and more interested in TESOL, which was originally new to me.

Now, it’s my family’s turn. They are really my most valued people in the world. When I cried telling them I wanted to transfer to this department, it was my father that first respected my decision. When I wailed because of the failure of teacher exams, it was my mom that consoled me with “There is always a way.” While I was almost exhausted by the schoolwork of the graduate studies and the overload of the teaching job, it was my two sisters that tried whatever they could do to help me alleviate my burden and pressure. Of course, without my considerate Justin, I might have become an ill-tempered person! Over the last three years, he is not only my soul mate but also my second mentor, standing by me passing through many setbacks as well as inspiring me with words of wisdom. In a word, it is they

that make me have unfailing courage to pursue my goal, to realize my dream, and to make my life well-rounded.

Last but not least, I am very grateful for all my friends who have directly or indirectly come to their aid: Siin, my movie partner, whose sencha livens me up in numerous nights of writing my thesis; Jean and Mandy, my colleagues, whose insights into English writing instruction enlighten me in many aspects; Susan, my college roommate, who teaches me how to make a table of contents with Word; Livia, my graduate schoolmate, who provides many spiritual supports during my thesis writing; Shang-wei, whose encouraging call before my oral defense lessens my anxiety; my “wine-and-meat” colleagues, who always supply me with greatest friendship in the final two stressful months of my thesis; finally, my lovely students—this thesis is never done without them. Even with all friends listed here, I am still unable to completely show my appreciation for their company during my graduate studies. But I still have to say, “Thanks, all my friends! Thank anyone who has done me a favor. ^^”

TABLE OF CONTENTS

中文摘要 ...i

ABSTRACT... iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...v

TABLE OF CONTENTS...vii

A LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES...ix

List of Tables ...ix

List of Figures ...ix

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION ...1

Background ...1

Rationale of the Study...3

Purpose of the Study ...4

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW ...7

L2 Writing and L1 Writing ...7

L2 Writing and Revision...10

L2 Writing Revision and Revision Difficulties ...10

Teacher Response and L2 Students’ Revision ...12

Teacher Response to L2 Students’ Writing ...14

Background ...15

The Roles of the Teacher and the Students...16

Modes of Teacher Response ...20

Types of Teacher Response in Terms of Explicitness ...22

Other Types of Teacher Response ...25

Focus of Teacher Response...26

Discussion on Teacher Response with Different Focus ...32

Students’ Revision...34

Students’ Reactions to Teacher Response...34

Effects of Teacher Response on Between-draft Performance ...37

Revising Strategies Used by Students ...38

Longitudinal Effects on L2 Students’ Writing Proficiency ...40

Other Factors Relevant to Students’ Revision ...41

Students’ Language Proficiency and Needs ...41

Summary: Relationship between Revision and Teacher Response ...42

CHAPTER THREE METHOD...44

Participants...44

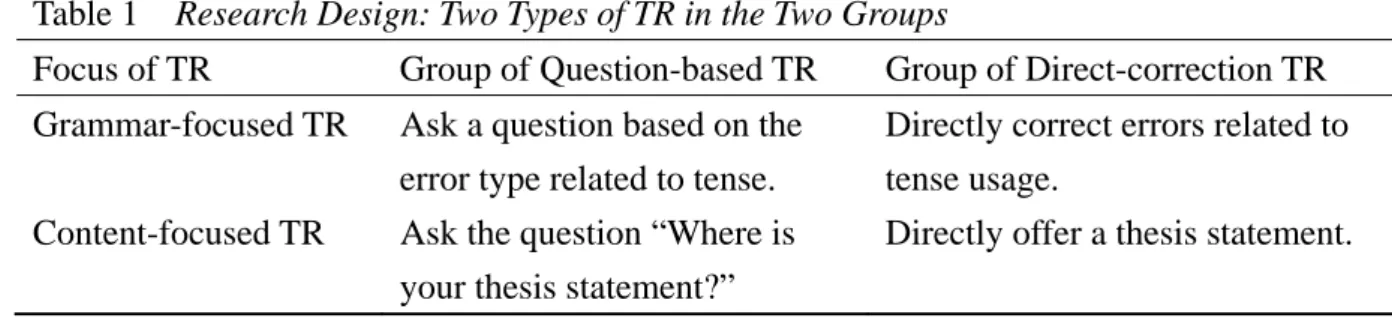

Types of Teacher Response in the Study...45

Procedure ...46

Data Analysis ...48

Validity...51

CHAPTER FOUR RESULTS...53

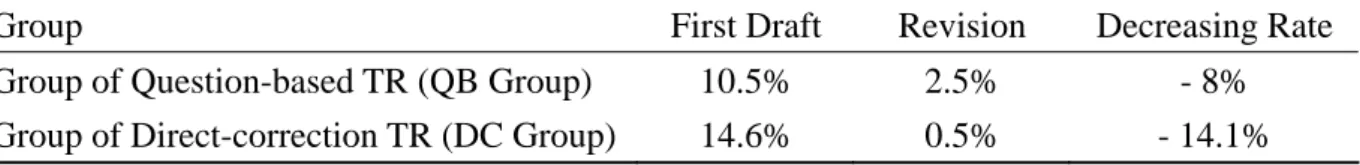

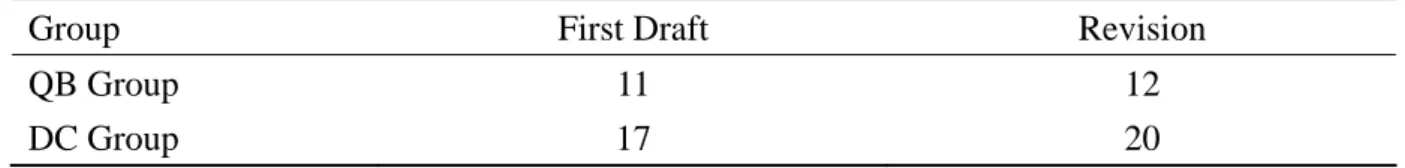

The Influence of TR on Students’ Revision...53

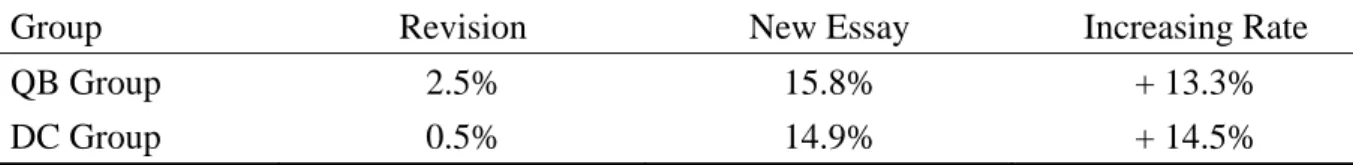

The Influence of TR on Students’ New Essay ...56

Students’ Viewpoints on Thinking Process ...63

Students’ Attitude toward Teacher Response ...66

The Protocols ...67

The Questionnaires and Interviews...72

Other Information from the Questionnaire ...80

CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSIONS, CONCLUSIONS, AND IMPLICATIONS ...87

Summary of the Findings...87

Students’ Attitude...90

Students’ Language Proficiency ...91

Time Limitation ...92

Pedagogical Implications ...93

Limitations of the Study...97

Suggestions for Future Research ...97

REFERENCES...99 APPENDICES ... 112 Appendix A ... 112 Appendix B ... 113 Appendix C ... 115 Appendix D... 117

A LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

List of Tables

Table 1 Research Design: Two Types of TR in the Two Groups...46

Table 2 TR for Errors in Tense Usage ...46

Table 3 Error Ratios in the First Draft and Its Revision ...53

Table 4 Amount of Drafts with a Thesis Statement in the First Draft and the Revision ...55

Table 5 Error Ratios in the Revision and the New Essay ...57

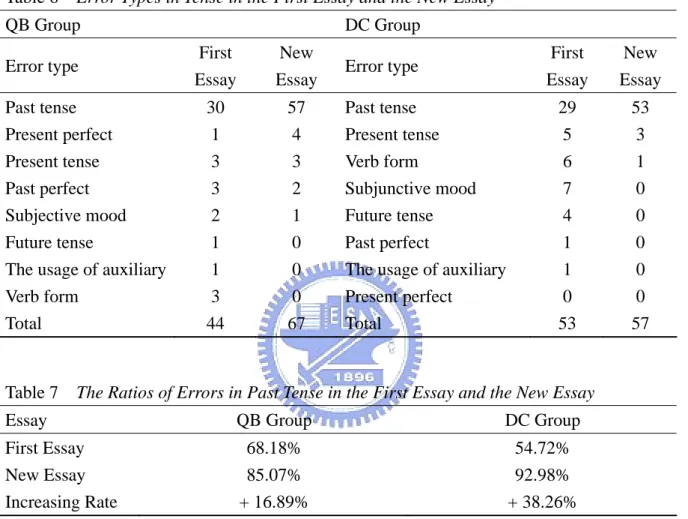

Table 6 Error Types in Tense in the First Essay and the New Essay ...58

Table 7 The Ratios of Errors in Past Tense in the First Essay and the New Essay...58

Table 8 Extracted Sentences with Problems from Students’ Error Profile ...60

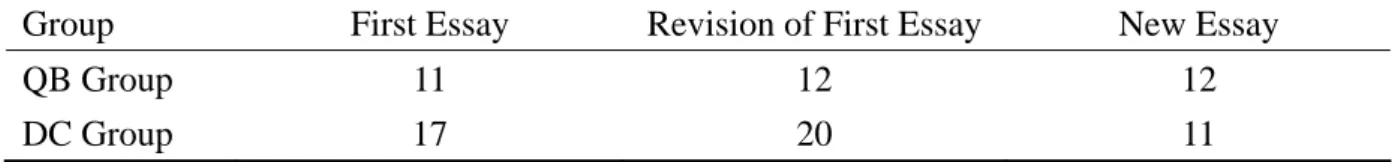

Table 9 Group Amount of Drafts with a Thesis Statement Across Three Drafts...61

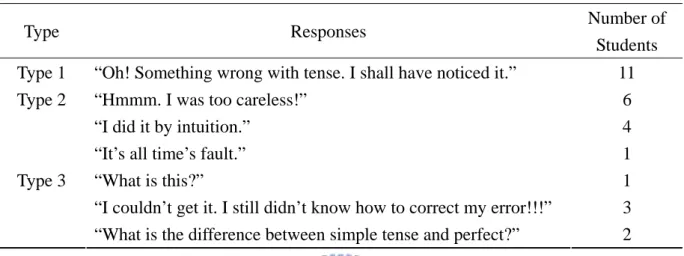

Table 10 Retrospective Protocol of the Question-based Group...68

Table 11 Retrospective Protocol of the Direct-correction Group ...69

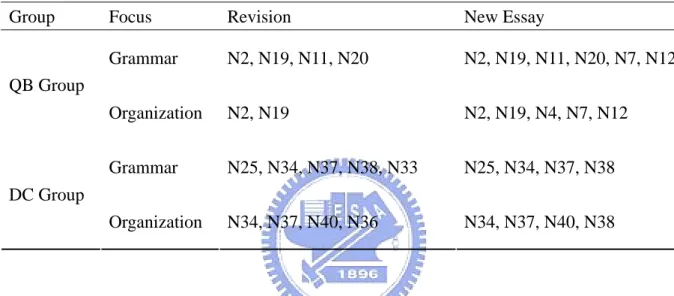

Table 12 Students’ Attitude toward the Influence of the TR ...73

Table 13 Students’ Attitude toward the Effect of the TR on the Revision and the New Essay ...75

Table 14 Students Showing Disagreement with the Influences of TR on Tense or Organization ...76

Table 15 Students’ Attitude toward Three Writing Processes...81

Table 16 Students’ Expectations for TR ...83

Table 17 Other Methods Students Hoped to be Treated with in Their Writing ...85

List of Figures Figure 1 Students’ Overall Impression on Whole Writing Activity………..73

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Background

Second language writing has drawn a great deal of attention in the past two decades. Both theories and pedagogical practices of first language (L1) writing have contributed a lot to the development of second language (L2) writing (e.g., Friedlander, 1990; Edelsky, 1982; Johns, 1990; Raimes, 1985). Inheriting theoretical premises from L1 writing, L2 writing specialists attend to the production of L2 writing, the recursive process of apprentice writers, the incorporation of teacher response (henceforth TR) in students’ revision, and the impact of TR during students’ composing process.

New trends of L2 writing, on the other hand, gradually emerge focusing on the distinctive nature of L2 learning, such as the role of vocabulary and grammar in L2 writing, L2 reading-writing connection, and genre analysis (Matsuda, 2003). More recently, the advances in computer technology also provide new possibilities for L2 writing and new techniques for incorporating computers into writing instruction. Lastly, academic writing is becoming a booming arena with the flourishing development of EAP writing in North America, which has attracted a large number of researchers to investigate and analyze its distinctive linguistic features in various important genres.

Of all L1 writing power over L2 writing development, the most dominant and influential is the process approach. Introduced to L2 studies by Zamel (1976), writing as a process is the primary notion of the process-based approach. The upholders of this approach advocates “ESL writing teachers need to have students write multiple drafts, to give feedback at intermediate stages of the writing process, to give feedback on content only on early drafts,

saving form-based feedback for the end of the process” (Ferris, 2003, p. 6).

Despite the wide spread of this approach in the academic field, many L2 writing teachers still follow traditional writing pedagogy, regarding students’ writing texts as final products and emphasizing surface linguistic accuracy. With regard to TR, research has indicated that the way a writing teacher responds to students’ work is often inconsistent and vague (e.g., Sommers, 1982). The validity of the teachers’ red mark on students’ writing drafts is inevitably under stringent debate (e.g., Ferris et al., 1997; Zamel, 1985).

Consequently, many L2 writing specialists have worked strenuously to probe into the relation between TR and students’ revision from a wide range of perspectives (see Leki, 1990; Reid, 1994; Silva, 1988), not only attempting to clarify how internal factors (e.g., the focus of the response) and external factors (e.g., students’ attitudes toward the responses they receive) may influence students’ performance on the subsequent writing practice, but also striving for a more viable and practical response system. In addition to the endeavor on the effects of TR upon students’ first draft and revision, many L2 writing experts have also tried to compare different types of TR in depth, with a view to finding effective guidelines for TR in an L2 setting.

The scope of L2 writing investigation on TR includes issues on the types of TR and the nature of TR (e.g., Ferris, 1997; Ferris et al., 1997; Hyland, 1998; Straub, 1996). The former line of the research explores topics such as the effectiveness of direct response (i.e., correcting errors directly) versus indirect response (i.e., indicating the erroneous part) (e.g., Ferris & Roberts, 2001; Frantzen, 1995; Makino, 1993; Polio et al., 1998). As for the nature of TR, three aspects are examined most frequently: (1) the mode of TR (e.g., static or dynamic), (2) the type of TR (e.g., direct or indirect correction), and (3) the focus of TR (e.g., grammar-oriented or content-oriented). Plenty of studies have compared the effectiveness of different types of TR with different focuses (e.g., Fathman & Whalley, 1990; Kepner, 1991; Robb et al., 1986; Russikoff & Kogan, 1996; Semke, 1984; Sheppard, 1992).

Despite many investigations and discussions on TR, the results, unfortunately, seem mixed. The influences of TR on students’ writing drafts are still in great dispute, because divergent findings have brought about flaming contentions about the utility of the teacher response on students’ writing. As a matter of fact, some L2 writing investigators even strongly recommend the abolition of grammar-focused TR, since they argue that studies have suggested low effect or even negative impact of grammar correction (e.g., Truscott, 1996, 1999). From these perspectives, the effectiveness of TR seems to require further explorations.

On the other hand, ever since 1960s, particularly before 1980s, the development of L2 writing mostly focused on the needs of international students in the U.S. higher education (Matsuda, 2003). Many insights from these studies have contributed a lot to the consolidation of L2 writing research. However, few studies have been conducted aiming at L2 students at the lower level such as high school students of English as a foreign language (EFL). A great need can be perceived for examining this group of students since English writing is also required for high school students in Taiwan.

Rationale of the Study

Therefore, this study is conducted on the premise that little research is performed targeting EFL novice writers at the high-school level. With lower language proficiency than university students’, high school students confront more challenges during their writing process; most of them are still at a stage of working hard to master linguistic aspects that are distinctively different from their first language. Some of them may even regard writing an English essay as a formidable task on account of their limited vocabulary and sentence patterns. Thus, we can imagine how revision may further compound their frustration of writing in English if they receive vague or unreadable TRs. To understand more about what exactly happens during the writing process of L2 high-school students and what kind of TR can be effective in facilitating their writing ability, the present study intends to examine the

influences of TR on their writing works.

Additionally, current high-school English writing instruction in Taiwan is often neglected, provided irregularly or with poor design, owing to the constraints of time allotted to the English writing course. Usually, students will wait till their final year to have a couple of opportunities to practice English writing; few of them can receive well-designed, effective writing instruction. It is common that writing teachers merely correct the errors in students’ writing drafts directly; such a traditional approach to error treatment, however, seems to have limited effects on students’ habitual errors. Some teachers, for the purpose of saving time, would simply mark students’ texts with underlines, circles, or question marks. These markers often confuse students, especially as students are not highly aware of their own errors. In a word, it seems hard for novice writers at the high-school stage to have clear ideas about how to revise an English composition without proper responses from their writing teachers. Since TR plays an essential role for novice writers, investigating different types of TR can further shed light on the influences of TR during students’ writing process.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is, therefore, to examine different types of TR in terms of its influences on students’ writing performances in revision and subsequent writing. This study also explores a new type of TR, written responses in the form of a question, which is hoped to be viable and widely adopted in EFL secondary school settings. Since the findings of previous studies on direct correction have been mixed, this study is carried out in the hope to get encouraging results from this question-based TR. Many researchers have indicated indirect response involves more “cognitive engagement” (Ferris, 2002, p. 19); as a result, the question-based response is expected to elicit more thinking process of the students who receive it. Furthermore, this thinking process is also expected to help students improve their ability to notice and tackle their errors in the subsequent writing.

This study, in consequence, attempts to examine two types of TR, delving into each influence on students’ revision as well as the new composition. Specific research questions are formed as follows:

1. Does teacher response influence students’ revision? If so, does this effect sustain? 2. Do different types of teacher response make differences in students’ revision? 3. Does grammar-focused response help reduce students’ grammatical errors in

revision?

4. Does content-focused response lead to students’ writing progress in text organization?

5. What attitudes do students have towards teacher response? How do they perceive different types of teacher response?

Initiated by an interest in L2 writing process, this study casts much concern with the relationship between teachers’ commentary and students’ writing performance, or more specifically, what impact a writing teacher’s response may have on students’ revision and subsequent writing. To investigate the influences of different types of TR on students’ following drafts, this study, from a more qualitative perspective, also looks into students’ thinking process as they were revising and their reactions to the TR they received.

The research design of the present study is as follows. Two groups of high school students were treated with different types of TR—one with direct correction as TR and the other with responses in the form of a question. The students then revised their compositions. Differences in students’ revision were analyzed to compare the influences of the two types of TR quantitatively and qualitatively. A new essay was given three weeks after the revision so that whether the effects of the different TRs sustained could be assessed.

To sum up, this investigation hopes to make contribution to L2 writing by providing insights into EFL high school novice writers’ performances with the aid of teacher response.

The results from both quantitative and qualitative analyses should offer inspirational pedagogical implications for high-school (writing) teachers in designing applicable writing curricula for writers with lower language proficiency.

In the next chapter, a detailed literature review is provided. After a general comparison between L1 and L2 writing, the difficulties arising from L2 writing process will be briefly discussed. Since this study is intended to scrutinize the effects of TR on students’ writing products, the nature of TR is mainly focused, including (1) the mode of TR, (2) the type of TR, and (3) two primary focuses of TR. What is more, as learning involves considerable external and internal factors, relevant factors which may make influences on the progress of students’ composing ability will also be discussed in the final subsection of the literature review.

In the third chapter, a thorough description of the methodology adopted in this study is presented. Targeting participants at the high-school level, this study employs different types of teacher response in two groups. The experimental group receives the response in the form of a question and group performances over three drafts are compared with that of the control group, which is treated with direct correction. Students’ writing and revising processes are accessed through their retrospective protocol, questionnaire, and interview.

Chapter four displays the findings of this study, arranged in the following sequence: immediate effect on revision, carry-over effect on subsequent writing, and students’ perception of the TR they received. The quantitative part of the findings is shown with the support or explanation of the qualitative findings from students’ protocols, questionnaires, and interviews, so that the influences of TR can be scrutinized and discussed in depth. The last chapter, discussions, conclusions and implications, starts with a summary of the findings, then discusses pedagogical implications and limitations of the study, and finally, provides suggestions for future research.

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter gives an extensive review of important studies in the research areas involved in second language writing. Firstly, we offer a general introduction to the development of L2 writing and gradually narrow the focus down to the revision in L2 writing. The effectiveness of teacher response (TR) on students’ revising process is discussed, from different types of TR to different focuses of TR. Findings and results related to the present study are highlighted. Besides, we also examine various perspectives on TR, such as teachers’ attitude toward TR and students’ attitude towards the role of TR in their writing process. Finally, we move to other possible reasons which may affect the effectiveness of TR on students’ writing.

L2 Writing and L1 Writing

The development of second language (L2) writing research has received much impact from research on first language (L1) writing. Many L2 writing researchers turned to the theoretical as well as pedagogical practices in L1 writing for guidance (e.g., Edelsky, 1982; Friedlander, 1990; Johns, 1990; Raimes, 1985).

Among all L1 writing theories, the process approach is the most influential on L2 writing evolvement. It has been widely adopted in L1 composition classrooms in the United States since early 1970s when the structuralist view of language was harshly criticized (e.g., Elbow, 1973; Garrison, 1974; Zamel, 1976). Different from product-oriented approach, the process approach focuses on the process of writing and revising and advocates multiple drafting. Upholders for this approach regard writing as a thinking process; it is a “non-linear,

exploratory, and generative process whereby writers discover and reformulate their ideas” (Zamel, 1983, p. 165; cited in Silva, 1990, p. 15). Hence, it is believed that “composition means thinking” (Raimes, 1983, p. 165; cited in Silva, 1990, p. 15) and that “content, ideas and the need to communicate would determine form” (Silva, 1990, p. 15). In light of these concepts, both student writers and writing teachers should attend to the composing process rather than the final product.

The process approach soon made waves in L2 writing research field. In many L2 writing conferences in the 1980s, there were an increasing number of studies exploring the practice and effect of the process approach in various L2 contexts (Leki, 1992).

Zamel, for example, is one of the most articulate L2 writing researchers who advocate the application of L1 writing tenets and principles, particularly, the process approach, to L2 writing research and pedagogy. Zamel (1985, 1987) proposed that

ESL writing teachers need to have students write multiple drafts, to give feedback at intermediate stages of the writing process, to give feedback on content only on early drafts, saving form-based feedback for the end of the process, and to utilize teacher-student conferences and peer response (cited in Ferris, 2003, p. 16).

Besides Zamel, Silva (1990) considered this seemingly ubiquitous approach one of the four influential L2 writing approaches between 1945 and 1990. Similarly, Johns (1990) discussed L1 composition theories, including the process approach, and indicated their implications for L2 writing development.

The trend of taking insights from L1 writing for L2 writing research and pedagogy is clearly shown in Silva (1988), who commented on Zamel (1987):

Work in native language composition has had a powerful impact because it has established the prima facie need to examine what writers do, what strategies they employ, what problems they experience, what notions they adhere to, in order that we may determine appropriate and effective instruction (Silva, 1988, p. 521).

On the surface, we have good reasons to believe that there are many similarities between L1 and L2 writing on the grounds that a similar fundamental cognitive process is involved in

both (Farch & Kasper, 1986). However, concerning the linguistic, cultural, and experiential aspects of writing, L1 and L2 writing are very different (Silva, 1988).

First, L2 writers experience a different writing process from L1 writers. Many studies have indicated that “the process of writing in an L2 is startlingly different from writing in our L1” (Raimes, 1985, p. 232). Direct application of L1 writing theories to L2 settings is therefore imprudent and improper (Silva, 1988). A similar conclusion was also made by Johns (1990) who indicated that no theory of L2 writing could be comprehensive merely based on L1 writing insights, because “world views among theorists, researchers, and teachers in both the first language and ESL differ” (Johns, 1990, p. 33). Johns (1990) suggested such difference in the light of four basic writing components which were first mentioned by Berlin (1982): the writer, the audience, reality and truth, and the source of language.

More convincingly, Silva (1993), examining 72 research reports, further revealed the distinct nature of L2 writing from L1 writing. From the perspective of composing processes and features of written texts, his study disclosed salient differences in three sub-processes: planning, transcribing, and reviewing. According to Silva (1993), L2 writers do less planning than L1 writers, spend more time referring to a prompt and consulting a dictionary, exhibit more concern and difficulty with vocabulary, write at a slower rate, and produce fewer words in a written text. L2 writers also show less reviewing involvement, with less rereading and less reflecting on written texts. This further echoes the findings in many studies which have reported that L2 writing involves more revision (Gaskill, 1986; Hall, 1987, 1990; Schiller, 1989; Tagong, 1991). Namely, these research results reflect the fact that L2 writers encounter more difficulties and frustrations at various stages of writing than L1 writers.

With regard to written text features, Silva (1993) also unveiled differences between L1 and L2 in terms of fluency, accuracy, quality, and structure. On the whole, L2 writing is a less fluent process, and tends to contain fewer words than L1 writing. L2 writers make more

errors overall. Even, L2 texts are also regarded as less effective than L1 texts (Campbell, 1987, 1990; Connor, 1984; Hafernik, 1990; Reid, 1988; Xu, 1990). Finally, in information structure, L2 writers’ texts manifest different features from the texts by native English speakers (NES) in terms of general textual patterns, argument structures, and narrative structures.

To sum up, as Silva (1993) has pointed out, although both L1 and L2 writers are observed to experience a recursive composing process, “L2 writing is strategically, rhetorically, and linguistically different in important ways from L1 writing” (p. 669). These differences, therefore, should be taken into consideration when L2 writing teachers face L2 writers and their writing.

L2 Writing and Revision

With the prevalence of the process approach, writing teachers try to adopt multiple drafting, emphasizing the importance of revision. As part of the writing and thinking process, revising is generally believed to give student writers more chances to practice conceiving their ideas, planning their organization, and thinking about how to iron out the problems they encounter. Thus, the process of revision turns to be valued and many researchers have devoted themselves to exploring the relation between writing and revising.

L2 Writing Revision and Revision Difficulties

As indicated in Silva’s (1993) survey, writing in a foreign language is a different and more difficult experience/process in comparison to writing in the native language. An L2 writer’s culture, social background, and rhetorical and linguistic conventions can exert considerable and sophisticated influence on their strategies and styles in learning and writing (Silva, 1997). Along with another Silva’s (1993) finding that L2 writing involved more revision, L2 writers are confronted with greater challenge in the L2 writing process. The

problem that makes most students challenged may be their poverty of ideas about how to construct a text with logical and persuasive content and their lack of appropriate lexicon and structural patterns.

From this perspective, opportune guidance from writing teachers can be helpful. The role of a writing teacher, as a result, has become a major concern in L2 writing research. Thanks to the development of this trend, the topic of teacher response (TR) to student writers captures much attention, since the provision of TR to students’ writing may have a direct impact on their revision as well as their writing proficiency.

Aside from the aforementioned challenge emerging from the composing process, L2 students may also confront other setbacks. First, L2 apprentice writers are less capable of revising in an intuitive manner of “revising by ear,” namely, on the basis of what “sounds” good (Silva, 1993, p. 662). Many L2 writers know where they may err but fail to revise appropriately. This weakness to exploit a more intuitive, native-like manner in revision may mainly result from students’ low language proficiency. On account of lower linguistic competence, ESL/EFL writers have to face more inevitable challenges than English-speaking writers in the use of more refined rhetorical skills when writing.

Second, even if L2 writers eventually accomplish their seemingly good composition, they may be frustrated by the hardship of revising processes, during which many L2 writers have been found sticking themselves in the mud of red marks on their texts. Influenced by the process-oriented pedagogies of L1 writing, many L2 researchers highly enthrone multiple drafts for a single writing assignment (e.g., Ferris, 2003; Sommers, 1982; Zamel, 1982, 1983, 1985). Accordingly, in L2 writing classrooms, more and more L2 students surely face the complicated procedure of writing the first draft, receiving the draft with or without TR, and submitting the revised draft. This “cycle of revision” (Butturff & Summers, 1980, p. 103) sometimes even takes place iteratively for the same writing product, but the effect is relatively limited. This practice is thus often complained by student writers and even writing

teachers (Ferris et al., 1997; Hairston, 1986).

The last difficulty L2 learners may encounter is revision strategies. It seems that both native speakers and non-native speakers are limited to their repertoire of strategies for revising compositions (Cohen, 1987). In particular, when given implicit or inconsistent TR, many student writers might just look at the red marks at their wits end. In view of this, both L1 and L2 writing research have been investigating the explicitness of TR for the sake of making TR more effective and efficient.

To date, the existing research on TR and revision has been discussed in full detail in the following subsections. Generally, three major facets are included: (1) the explicitness of TR, (2) the forms of TR—including response mode, response type, and response with different focuses, and lastly (3) the influence of various types of TR, such as the effectiveness on students’ revisions from either a short-term or a long-term perspective, and its impact on students’ attitude.

Teacher Response and L2 Students’ Revision

Beason (1993) noted that “feedback and revision are valuable pedagogical tools…… the research typically indicates that high school and college students improve their drafts upon receiving feedback” (p. 396). Clearly, students tend to follow their writing teacher’s feedback to revise their drafts since TR to some extent serves as a kind of guidance for writing. In Taiwan, it is very common that students depend on TR revising their writing. This is partly because teachers, in a sense, are authoritative, and partly because teachers’ instruction usually plays an essential role in students’ learning process.

The provision of TR is often regarded as an indispensable job for Taiwanese writing teachers. Writing teachers, on the one hand, feel it their duty to offer commentary on their students’ writing; students, on the other hand, expect and follow guidance from their teacher(s). However, as pointed out by Ferris (1995, 1997), while students are expected to

pay attention to TR so that they can make substantial and effective revisions, some students, unfortunately, may sometimes selectively ignore the written responses or avoid correcting based on the TR they received (Beason, 1993; Hyland, 1998, 2003; Sommers, 1982). The effectiveness of TR is thus of interest and concern to writing researches in Taiwan.

In reality, both L1 and L2 writing research have indicated the inconsistency of TR to students’ texts. This phenomenon may partly explain why some students are unable to understand or even disregard the response from their writing teachers. In an ESL setting, Cumming (1983) found that “teachers’ response to the same text differ, and that the application of error-identification techniques varies considerably” (cited in Zamel, 1985, p. 85). Similarly, Zamel (1985) reported that, in agreement with much of what had been found about L1 writing teachers’ feedback, ESL writing teachers

are inconsistent in their reactions, make arbitrary corrections, write contradictory comments, provide vague prescriptions, impose abstract rules and standards, respond to texts as fixed and final products, and rarely make content-specific comments or offer specific strategies for revising the text (p. 86).

Indeed, there is no denying that few writing teachers can provide consistent and systematic responses to students’ texts; many may just mark students’ errors at will. Interestingly enough, most writing teachers, especially L2 writing instructors, would wonder why students keep making habitual mistakes in their writing. Some experienced teachers even concluded that providing responses has merely slight effect on students’ revision; written TR cannot facilitate students’ writing development from a longitudinal view.

Numerous studies have investigated the effects of TR on students’ revision and subsequent drafts. The findings are mixed, ranging from affirmative recognition to extreme denial: some support the instructive function of TR (e.g., Ferris, 1997, 1999a, 1999b; Ferris et al., 1997; Hyland, 1998, 2003; Lalande, 1984) whereas others report the futility of employing TR (e.g., Hendrickson, 1978; Kepner, 1991; Robb et al., 1986; Semke, 1984). Despite the controversy, many studies have provided profound discussion over TR with specific focus,

namely, on content or mechanics (e.g., Ferris, 1997; Kepner, 1991; Semke, 1984), and have given valuable insights into TR by inquiring different types of responses (e.g., Ferris et al., 1997; Hyland, 1998, 2003).

As mentioned in Hedgcock and Lefkowitz (1994), “Effective revision in L1 and L2 requires the engagement of the learner, as well as the careful application of feedback practices which can guide the writer to an awareness of the informational, rhetorical, and linguistic expectations of the intended reader” (p. 145). Whatever TR is adopted, the most important and worthwhile to do is whether students can take TR as meaningful input and apply them to their revision; then the effect of TR can be carried over to another assigned writing. Student writers’ involvement in writing and revising processes and their attitudes towards TR thus become pivot in the writing instruction.

Teacher Response to L2 Students’ Writing

Teacher response (TR) to students’ writing has aroused considerable disputes over several decades in both L1 and L2 writing research, even though both writing instructors and student writers may often intuit that written responses “should” have positive effect on writing (also see Ferris et al., 1997; Leki, 1990). However, as indicated earlier, teachers often respond inconsistently; moreover, learners and teachers may not share the same ideas about what kind of feedback teachers should provide for students’ writing (Ferris et al., 1997; Sperling & Freedman, 1987). While some students may call for more direct error correction, others may desire more comments on content or rhetorical advice. In addition to teachers’ personal belief and teaching philosophy, students’ individual belief also affects the effectiveness of TR (Hyland, 2003). Moreover, it was discovered that many TRs might be misinterpreted by both L1 and L2 students (e.g., Hayes & Daiker, 1984; Wall & Hull, 1989). These factors all contribute to the complicated nature of the TR to students’ composition.

the last decades, then the roles of the teacher and the students in the process approach setting. After that, different modes of TR are introduced and the nature as well as merits and limitations of each type of TR are discussed. Then the next subsection introduces two types of TR, the central concern of this study. Finally, two main focuses of TR are discussed in depth with a view to providing further information about teacher response.

Background

Research on L1 writing responses dated back to 70s and early 80s, when many L1 writing investigators (e.g., Searle & Dillon, 1980; Sommers, 1982) tended to conclude that written feedback “is of poor quality, focuses on the wrong issues, and is often ignored, misunderstood or misinterpreted by the student writers” (Hyland, 1998, p. 255). Following the development of L1 writing, the investigation of the TR to L2 writing began in the mid-1980s.

During 1980s, many L2 writing teachers tended to concern themselves with “error identification,” namely, paying attention to “the accuracy and correctness of surface-level features of writing” (Zamel, 1985, p. 84). Instead of giving written commentary and using multiple drafts, L2 writing instructors adhered to single-draft, error-focused models when responding to L2 writing texts. This interest in grammatical and mechanical accuracy may probably derive from the in-service training system in 1980s; that is, most L2 teachers did not receive appropriate training in the instruction of rhetoric and composition (Applebee, 1981; Ferris, 2003). Very few curricula were designed to train teachers-to-be to teach writing in second language settings.

However, this model of single-draft, error-focused writing instruction started to change in the beginning of 1990s. Many studies in early to middle 1990s reflected an increasing number of writing teachers who tended to use TR which dealt with more global issues (e.g., Caulk, 1994; Ferris, 1995; Hedgcock & Lefkowits, 1994; Lam, 1991; Saito, 1994). In other

words, rather than focusing on sentence-level errors, more teachers and researchers shifted their attention to the organization of the composition and the idea development.

More recently, a series of studies by Ferris (1997) and her colleagues revealed that of over 1500 verbal comments on 110 ESL students’ writing, 15% in the margins and in endnotes focused on grammar and mechanics issues such as spelling, while the remaining 85% of teachers’ commentaries centered on students’ ideas and rhetorical development. Another case study by Conrad and Goldstein (1999) also reported this shift from local errors to more global issues such as coherence/cohesion, paragraphing, content, purpose, lexical choice and the fluency of the writing.

In a word, thanks to the prosperity of the process approach in the North American academic setting, the way L2 writing teachers respond to students’ writing has made the shift over the past 15 years, from offering error-focused TRs in one single draft (product-oriented approach) to providing TRs focusing on a broader spectrum of issues across multiple drafts (response-and-revision writing cycle). Despite some negative pronouncements against the employment of TR, especially in the form of written commentary (e.g., Hillocks, 1986; Knoblauch & Brannon, 1981), positive arguments for it have been increasingly reported (e.g., Ferris & Hedgcock, 1998; Hairston, 1986). For L2 novice writers, responses from their writing teachers are always expected (e.g., Leki, 1986) since they can at least receive some comment or advice on their “masterpiece.” On the one hand, TR shows a teacher’s concern and care for students and their works; on the other, it also serves as a medium of communication and interaction between students and teachers.

The Roles of the Teacher and the Students

With the shifting focuses of TR over the last decades, the role of the writing teacher also changes. According to Kepner (1991), process writing “is subject to formative rather than summative evaluation…… the teacher-as-responder should function as a diplomatic

coach who offers reactions and advice first to content issues…. Correction of discrete errors should occur only at the final stage of editing” (p. 306). A writing teacher who adopts process approach may act as a diplomatic coach in the initiate stage of students’ writing process and students’ revision. However, their role may change to a corrector at the final stage of editing. In other words, the role a teacher plays may vary from draft to draft.

In fact, the prevalence of process-oriented approach in writing classrooms not only affects the roles a writing teacher plays but also changes the roles of the students. Now teachers are expected to expand their roles from an “examiner, critic, and judge” to a “reader, coach, mentor, fellow inquirer, and guide” (Straub, 1997, p. 92). Students, on the other hand, as an apprentice writer though, are anticipated to become an independent writer who can actively plan his/her composing process and can consciously monitor and edit the use of appropriate language for the creation of a writing product.

Advocators of the process approach from an “expressivist” view (see Faigley, 1986) regard teachers as a facilitator who designs in-class activities to promote students’ writing fluency and who encourages students to take power over their writing act (Elbow, 1973, 1981). Another group of process-approach upholders from the “cognitivist” perspective believe that the goal of a writing teacher is to produce good writers and to help them “guide their own creative process” (Flower, 1985, p. 370; cited in Johns, 1990, p. 26). They encourage students to plan their ideas extensively and translate their plans into words; in consequence, the writing process is never considered to be completed until revising and editing are done.

According to Leki (1990), there are three personas for writing teachers: teacher as a real reader (Probst, 1989; Zamel, 1985), teacher as a coach (Purves, 1984), and teacher as an evaluator (Flower, 1988; Land & Whitley, 1989). Combining many writing researchers’ suggestions for the role of the instructor in students’ writing process, Straub (1996) proposed that a teacher can respond “as a facilitator,…as a teacher reader, a guide, a friendly adviser, a

diagnostician, a coach, a motivator, a collaborator, a fellow explorer, a common reader…an idiosyncratic reader, a sympathetic reader, a trusted adult, and a friend” (p. 225).

In fact, the teacher-student relationship and their respective roles are determined by the way in which the teacher responds to students and their writing works. Straub (1996) indicated that the nature of teacher response is “either directive or facilitative, authoritative or collaborative, teacher-based or student-based” (p. 224). As a result, the teacher may act as a director or a facilitator, an authority or a collaborator in some way.

Notwithstanding the wave of the process-oriented approach in L2 writing research, many L2 writing teachers remain to rely on product-oriented approach. They tend to focus on accuracy and correctness of surface-level features on students’ single draft. As Cumming (1983) mentioned, “error-identification appears to be ingrained in the habitual practices of second language teachers who perhaps by reason of perceiving their role solely as instructors of the formal aspects of language” (p. 6). In many cases, it has been discovered that students’ attention was taken away from their original purpose because of their teacher’s error correction (Sommer, 1982). The fact that students shift their “attention [to] the teachers’ purpose in commenting” (Sommer, 1982, p. 149) has led to increasing criticism about teachers’ appropriation.

Given the ingrained power relation in the classroom, teacher’s comments, to a certain extent, are surely “evaluative and directive” (Straub, 1996, p. 247). It is understandable that students revise their writing according to the changes that teachers impose on their drafts. However, as indicated by Hyland (1998) that “writing is a process in which meaning must be given priority” (p. 281), the purpose of writing for students should lie in learning how to express themselves with proper and acceptable language and structure. Therefore, the essence of writing is to allow writers “to make their own writing decisions and learn to make better choices” (Straub, 1996, p. 248).

independent writer and meanwhile make compositions readable for readers (Leki, 1990; Zamel, 1985). If student writers are forced to revise their drafts on the basis of the standards set by the teacher, they are just urged to follow “idealized texts” (Straub, 1996, p. 223); that is, they are imposed by the teacher’s ideas, not conceiving their own ideas. In this sense, teachers are appropriating students’ writing products but not judging and evaluating their texts as a reader or an audience.

As proposed by Zamel (1985), the attempt to over-manipulate the intellectually complex writing assignments may result in “breakdowns or setbacks” (p. 95) of student writers’ efforts in challenging composing tasks. The teachers’ appropriation in terms of content can be avoided if the teacher is highly aware of the “serious aftereffect” of the appropriation. However, in terms of grammar, writing teachers may easily confront the dilemma of whether a grammar correction should be offered, particularly when facing students at a lower level who may require more linguistic corrections and instructions in their grammatical errors.

With overwhelming evidence showing teachers’ attention to surface-level features (e.g., Collins, 1981; Moran, 1981; Murray, 1982; Sommers, 1982), many apprentice writers were subject strictly to their teacher’s “instructions” and some even relied on them very much, valuing their own writing based on these grammar-focused responses. In this regard, students were no longer an author but a secretary who followed exactly the instructions of an authoritative boss. Their writing teachers, on the other hand, were thus criticized for looking upon themselves as primarily language teachers rather than composition instructors (Cumming, 1983, 1985).

In conclusion, no matter which role a writing teacher plays, students’ writing must be respected enough. In this case, students may have more courage to try again and again. Similar to Purves (1984), Zamel (1984) suggested that teachers need to “play a whole range of roles as readers of student writing…… [by] probing, challenging, raising questions, and

pinpointing ambiguities, [we can] help students understand that meaning-level issues are to be addressed first” (p. 96). After all,

to accentuate the role of composing in discovering new knowledge is to show students why their writing matters, therefore to increase their motivation to write, and therefore, ultimately, to increase the likelihood of improvement because they have become more aware of the purpose and value of making meaning (Knoblauch & Brannon, 1983, p. 468).

Finally, as has been noted by Sommers (1982) and Branno and Knoblauch (1982), teachers can choose to “resist taking over student texts and instead to make comments that share responsibility with the writer” (Straub, 1996, p. 224-225) rather than eagerly offer comments or corrections. In reality, it is definitely more meaningful for writing teachers and researchers to meditate what instructional philosophy a composition instructor should hold and what kind of role a writing teacher should play in students’ writing process.

Modes of Teacher Response

In literature, many researchers use “mode” to clarify the status of teacher response: static versus dynamic. Roughly speaking, written TR is static while oral TR is dynamic. Traditionally, written TR is used by most writing teachers for the sake of convenience. In static modes, teachers may offer their responses in the form of (1) direct correction, (2) coding/minimal markers to indicate the error, (3) suggestions for content development, (4) questions asking for more specific description, or even (5) imperatives. On the other hand, oral response lays more emphasis on its interactive nature, and it is therefore highly recommended recently (e.g., Carnicelli, 1980; Sokmen, 1988; Zamel, 1985). Such activities as holding a teacher-students conference or an individual face-to-face meeting are two typical practices of dynamic response.

During the 1970s, many L1 scholars enthusiastically endorsed the dynamic TR such as conference or individual meeting as an ideal approach because this mode of TR was

interactive and instructional in nature (e.g., Carnicelli, 1980; Elbow, 1973; Garrison, 1974). As two-way negotiation, writing conference was favored by L1 experts over one-side written directives (Brannon & Knoblauch, 1982; Sommers, 1982). Zamel (1985) even suggested ESL teachers hold conference because “dynamic interchange and negotiation is most likely to take place when writers and readers work together face-to-face” (p. 97). Indeed, a face-to-face meeting is actually a forum where writing problems, particularly those too complicated to negotiate in a written mode, can be immediately addressed through the dynamic in-person discussion, and where efficiency and effectiveness of feedback can be improved.

What is more, student writers in an ongoing dialogic process may encounter more cognitive challenge such as questions raised by instructors or peers in real time. Ambiguity or questions in the dynamic mode would be immediately clarified because any doubts could be asked in the presence of the feedback giver. In fact, it has been claimed that cognitive involvement benefits students because through “cognitive engagement” (Ferris, 2002, p. 19) students are guided to make reflection and to learn problem-solving by themselves.

As the dynamic feedback is generally more comprehensible than the static feedback, some researchers have suggested that written response along with face-to-face student-teacher conference may be a desirable way to help students with their revision as well as the subsequent compositions (e.g., Hyland, 1998). Hedgcock and Lefkowitz (1994) in their survey even reported that 60% of the respondents preferred written feedback combined with writing conferences, while 30% chose written-only feedback as the most meaningful mode and merely 10% selected verbal-only responses.

Considering dynamic and static features of TR, Knoblauch and Brannon (1981) appealed to teachers for more concerns about the ongoing dialogue between students and themselves. If a teacher’s written response could have more interaction in nature, novice writers may be more involved as if there were in a writing conference.

writing process, as we already indicated that teacher should avoid appropriation. Instead, it is high time for teachers to ponder over when responses should be given, just as we would choose a proper timing to interrupt in a conversation. In a study by Ziv (1984), it was revealed that when the teacher intervened appropriately in students’ writing and revising process, students’ final product got improvement over the intermediate drafts (see also Feedman, 1987).

Zamel (1985) also indicated the importance of establishing the priority of teacher response. Taking a similar view, Straub (1996) proposed that writing teachers ask themselves “what kind of comments will be best for this student, with this paper, at this time” (p. 247). He further concluded that

the best responding styles will not feature certain focuses and modes of commentary and excluded certain others…[but] will create us on the page in ways that fit in with our classroom purposes…enable us to interact as productively as we can with our students (Straub, 1996, p. 248).

Despite the fact that creating a two-way negotiating channel might do student writers good, a final but also important point is, as mentioned before, whether this intervention of feedback generates benefits to students’ success in composing. It is indicated that TRs might be most effective and meaningful if they could be incorporated into the subsequent assignments of the students (Hillocks, 1986; Leki, 1990). However, little research to date has ever expatiated exact means by which apprentice writers can well amalgamate their teacher’s feedback with their later assignments.

To sum up, this subsection has suggested that written TR with dynamic nature might be more effective. Besides, writing teachers are also advised to devise feedback which student writers can incorporate into their revision and the subsequent texts.

Types of Teacher Response in Terms of Explicitness

of explicitness, we have direct feedback and indirect feedback. This classification is based on the extent to which a teacher provides clues for the correction or revision of the text. Direct feedback is considered explicit; on the other hand, indirect feedback is relatively implicit. Further analyzing indirect feedback to see its degree of clearness, in the same vein, we can identify coded feedback and uncoded feedback. As mentioned, many student writers have difficulty interpreting TRs due to the lack of consensus with their teachers on the meaning of feedback. Explicitness thus turns out to be an important issue in students’ reaction to TRs.

According to Ferris (2002), indirect feedback “occurs when the teacher indicates that an error has been made but leaves it to the student writer to solve the problem and correct the error” (p. 19). Though somewhat vague for some students, indirect feedback has been claimed to be more helpful to student writers than direct feedback (e.g., Lalande, 1984; Ferris, 1995b; Ferris & Hedgcock, 1998; Reid, 1998). On account of more “cognitive engagement” (Ferris, 2002, p. 21) such as reflection and problem-solving during the writing process, indirect response is favored by many researchers either from a short-term or a long-term perspective. Ferris and Roberts (2001) suggested that indirect feedback techniques, such as locating the type of error and asking students to correct error themselves, may be of help for “untreatable” errors, like word choice and sentence structure (Ferris, 1999a, p. 6). In a longitudinal study by Frantzen (1995), compared with grammar-supplementation group treated with direct feedback, students in the non-grammar group receiving indirect feedback showed overall improvement (see also Lalande, 1982). This suggests that implicit response is pedagogically significance: it allows students to learn on their own by thinking over possible errors so that they can correct and revise independently.

On the other hand, direct feedback which “provides the correct linguistic form for students” (Ferris, 2002, p. 19) appears to receive more criticisms. Of all the opponent research against the employment of direct feedback, the strongest argument is proposed by Truscott (1996, 1999), who claimed that grammar correction was often ineffective and even

harmful. Truscott (1996) suggested the abeyance and even the abolition of error correction in L2 writing classes, for substantial research in both L1 writing and L2 writing showed grammar correction did not work (e.g., Hendrickson, 1978; Knoblauch & Brannon, 1981; Krashen, 1992; Leki, 1990). What is more, because many studies had disclosed that there was no difference between the experimental group, who received error correction, and the control group, who received other types of response or even no response (Frantzen & Rissell, 1987; Kepner, 1991; Robb et al., 1986; Semke, 1984; Sheppard, 1992), Truscott (1996) thus claimed that it was “necessary to undermine the intuitions, to show that correction does not have to help and in fact should not be expected to help” (p. 341).

Despite Truscott’s conclusion that “correction was not only unhelpful in these studies but also actually hindered the learning process” (Truscott, 1996, p. 333), Ferris (1999a), one of the strongest grammar-correction advocators, argued that students could improve their language accuracy through feedback on form if the erroneous constituent is “treatable” rule-governed errors such as verb tense, verb form, subject-verb agreement, article usage, plural and possessive noun endings, sentence fragments, run-ons, punctuation, or spelling. As for “untreatable” errors, such as word choice errors, preposition usage, and personal narrating style which is sometimes idiosyncratic and not so idiomatic, a more directive tactic like reformulation or complete correction may help improve (p. 6; see also Ferris, 1999b, 2002).

Another issue related to the explicitness of TR is how explicit indirect response needs to be. Some writing teachers may just underline errors; some tend to mark the problematic items with special symbols or codes. Some may offer a list of coding symbols to students as reference. In terms of indirect feedback, it is clear that responses with a wide range of explicitness are being adopted now.

According to Ferris (2002), indirect feedback is further classified into “coded” and “uncoded” (p. 20). The former is the way in which errors, such as verb tense or spelling, are clearly indicated, while the latter means the writing instructor just circles or underlines an

error but leaves it for students to diagnose and solve the problem on their own. In this sense, coded feedback is more explicit than uncoded feedback.

Whether TR with different explicitness shows more effectiveness has been investigated for long. Robb et al. (1986) examined responses with a continuum of progressively less explicitness. They divided 134 EFL university students into four groups receiving (1) direct correction, (2) coded feedback, (3) uncoded feedback, or (4) marginal feedback, finding that there was no apparent difference among them. The findings of Robb et al. (1986) concur with considerable research studies which indicated that explicitness of feedback did not enable students to improve their revision or subsequent writing (e.g., Ferris and Roberts, 2001; Ferris et al., 2000).

Although no significant difference was found between more-explicit and less-explicit feedback in revision, from a longitudinal perspective, Ferris and Roberts (2001) argued that “this strategy (of giving less explicit response) may not provide adequate input to produce the reflection and cognitive engagement that helps students to acquire linguistic structures and reduce errors over time” (p. 177). They thus insisted on the affirmative function of the more explicit (coded) indirect marking techniques exploited during students’ writing process.

To sum up, in this subsection, many types of TR are introduced on the basis of the degree of explicitness. The most explicit is the direct correction and the most implicit is the uncoded indirect correction; in the middle of them is the coded indirect correction. Although the results of TRs with different degree of explicitness remain mixed so far, each of them has shown respective effects on students in some aspects.

Other Types of Teacher Response

In addition to direct versus indirect feedback and coded versus uncoded feedback, marginal notes and endnotes are two other common types of written TR. Ferris et al. (1997) examined the nature of comments made by the teachers in their study, finding that a high

proportion of marginal notes were characterized by text-based comments (81.3%); besides, many of marginal comments appeared in the form of a question asking for further information. On the other hand, fewer text-specific comments were found in endnotes (67.4%); however, an overwhelming number of endnotes were in the form of statements (rather than questions or imperatives). Generally, marginal notes were used more often than end notes.

Recently, with the promotion of multiple teaching methods to provide students with diverse learning stimuli, a variety of TR types are employed by teachers, inclusive of peer response, teacher-student conference, audio-taped commentary, and computer-based commentary. In particular, face-to-face discussion has been widely recommended on account of its prompt interaction (Hyland, 1998); therefore, relevant investigations have been conducted in both L1 and L2 writing research (e.g., Carnicelli, 1980; Goldstein & Conrad, 1990; Sokmen, 1988; Walker & Elias, 1987).

Notwithstanding manifold types of TR available now, handwritten commentary remains the primary form of response more accessible for students (Ferris, 1997); it is still the most viable and common form of TR on students’ compositions (Ferris et al., 1997). Since the purpose of the present study is to investigate the written response, further discussion will focus on only written TR.

Focus of Teacher Response

In history, the focus of TR fluctuated between form and content is never stopped. In the 19th century, rhetoric was taught and little attention was centered on grammatical correctness (Connors, 1985). This trend of using content-oriented feedback did not change until the end of the 19th century; in the 20th century, with the growing interest in grammatical correctness, form-focused TR was commonly used. Particularly from 1976 to 1986, a fair amount of research related to error feedback in L2 classes (Ferris, 2003). However, in recent years,