Betel nut chewing is associated with increased risk of

cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in Taiwanese men

1,2

Wen-Yuan Lin, Tai-Yuan Chiu, Long-Teng Lee, Cheng-Chieh Lin, Chih-Yang Huang, and Kuo-Chin Huang

ABSTRACTBackground: Betel nut chewing is related to several kinds of cancer, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Whether it is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality, however, remains unclear.

Objective: We aimed to investigate the association between betel nut chewing and CVD and all-cause mortality.

Design: A baseline cohort of 56 116 male participants욷20 y old

were recruited from 4 nationwide health screening centers in Taiwan in 1998 and 1999. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to estimate the relative risks (RRs) of CVD and all-cause mortality for betel nut chewers during an 8-y follow-up period. Results: There were 1549 deaths during the follow-up period, 309 of which were due to CVD. After adjustment for age, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, lipids, smoking, alcohol consump-tion, physical activity, income, and education level, the RRs (95% CI) of CVD and all-cause mortality among the former betel nut chewers were 1.56 (1.02, 2.38) and 1.40 (1.17, 1.68), respectively, and those among current chewers were 2.02 (1.31, 3.13) and 1.40 (1.16, 1.70), respectively, compared with persons who had never chewed betel quid. Current and former betel nut chewers had a higher risk of CVD mortality (RR: 2.10; P쏝 0.05) than did current and former smokers. Greater frequency of betel nut chewing was asso-ciated with greater CVD and all-cause mortality.

Conclusions: Betel nut chewing was independently associated with a greater risk of CVD and all-cause mortality in Taiwanese men. Regular screening for betel nut chewing history may help prevent excess deaths in the future. An anti-betel nut chewing program is urgently warranted for current chewers. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87:1204 –11.

INTRODUCTION

Betel nut (Areca catechu) is the fourth most widely used

addictive substance in the world. Betel nut chewers now make up

욷10% of the world’s population (1, 2). There are many different

ways to prepare betel nut. For example, in South Asia, people

chew the fresh, dried, or cured betel nuts with slaked lime, betel

leaf (Piper betle vine), and tobacco leaves (2, 3). In Taiwan,

however, people chew betel nuts in combination with P. betle

(inflorescence or leaf) and lime but without tobacco leaves (3, 4).

Four main arecal alkaloids (ie, arecoline, arecaidine, guvacine,

and guvacoline) are absorbed during betel nut chewing (1).

The arecal alkaloids have been shown to be inhibitors of

␥-aminobutyric acid receptor and also to have many physiologic

and metabolic effects on the brain, cardiovascular system, lung,

gut, and pancreas (1).

Betel nut chewing is linked not only to the development of oral

and esophageal caner, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver

cir-rhosis (1, 5–10) but also to obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension,

hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and chronic kidney

dis-ease (11–16). However, it is unclear whether betel nut chewing

is associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is one of

the leading causes of death worldwide (17). In Taiwan, the

prev-alence of betel nut chewing is as high as 16.9% (31% in men and

2.4% in women, respectively) (15). Until now, however, there

has been no study of the long-term effect of betel nut chewing on

CVD and all-cause mortality. Therefore, we investigated the

association between betel nut chewing and CVD and all-cause

mortality in a large Taiwanese cohort.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects and measurements

The data were collected from 4 private nationwide MJ Health

Screening Centers in Taiwan in 1998 and 1999. The registered

health practitioners in these centers provide a multidisciplinary

team approach to the health assessment of their members. Most

of the members undergo a health examination every 3– 4 y, and

앒30% of them will receive the same health check-up every year.

A total of 58 771 male adults

욷20 y old, out of 124 513 subjects,

were recruited into the study; female betel nut chewers were

excluded because the prevalence of betel nut chewing in women

was very low (0.46%). Among the 58 771 male adults, 2655 did

not complete the items pertaining to betel nut chewing habits on

the questionnaire. Therefore, the baseline cohort analyzed in the

study comprised 56 116 participants. The population structure in

1From the Department of Family Medicine, China Medical University

Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (W-YL and C-CL); the Department of Family Medicine and the Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Science (W-YL and C-CL) and the Graduate Institute of Basic Medical Science (C-YH), College of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; the Department of Family Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (W-YL, T-YC, L-TL, and K-CH); and the Institute of Health Care Admin-istration, College of Health Science, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan (C-CL).

2Address reprint requests to K-C Huang, Department of Family Medicine,

National Taiwan University Hospital, 7 Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan 100. E-mail: bretthuang@ntu.edu.tw.

Received September 2, 2007.

Accepted for publication January 8, 2008.

1204

Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1204 –11. Printed in USA. © 2008 American Society for Nutritionat National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

our study was similar to the national data for adult males

pub-lished by the Taiwanese government (18). Deaths were

ascer-tained by computer linkage to the national death registry by using

identification numbers. All deaths that occurred between study

entry and December 2005 were included. Deaths with

Interna-tional Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes

390 – 459 were classified as CVD deaths (19).

Anthropometric characteristics, blood pressure, and plasma

fasting glucose and lipid concentrations were measured and were

described in an earlier report (20). In brief, trained staff measured

the height (to the nearest 0.1 cm) and weight (to the nearest 0.1

kg) of each participant by using an autoanthropometer

(KN-5000A; Nakamura, Tokyo, Japan). Waist circumference was

measured (to the nearest 0.1 cm) at the midway point between the

inferior margin of the last rib and iliac crest in a horizontal plane

by using a nonstretchable tape. Body mass index (BMI; in kg/m

2)

was calculated. The blood pressure (BP) was measured in the

right arm of a seated participant by using an appropriately sized

cuff and a standard mercury sphygmomanometer after

partici-pants had

욷5 min of rest. Blood was drawn with minimal trauma

from an antecubital vein in the morning after a 12-h overnight fast

(20). Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose concentration

욷 7.0 mmol/L and a history of diabetes or of taking oral

hypo-glycemic agents or insulin (or both). Hypertension was defined

as systolic BP

욷 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP 욷 90 mm Hg (or

both) and a history of hypertension or of taking antihypertensive

drugs (or both).

All patients provided written informed consent. Approval for

patient recruitment and data analyses was obtained from the MJ

Research Foundation Review Committee in Taiwan.

Questionnaire

Betel nut chewing, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption,

and physical activity histories were recorded for each subject

from a questionnaire. Current, former, and never users were

defined as those who reported the current use, any prior use, and

TABLE 1

Baseline characteristics by status of betel nut chewing

Betel nut chewing

P Never (n҃ 44 565) Former (n҃ 5568) Current (n҃ 5983) Age (y)2 43.4앐 14.33 40.4앐 12.5 40.1앐 11.6 쏝0.001 Height (cm)2 168.6앐 6.3 168.6앐 6.2 168.5앐 6.1 0.922 Body weight (kg)2 67.3앐 10.3 68.6앐 11.3 68.8앐 11.1 쏝0.001 BMI (kg/m2)2 23.7앐 3.2 24.1앐 3.6 24.2앐 3.5 쏝0.001 WC (cm)2 81.6앐 9.7 82.5앐 10.1 82.8앐 9.7 쏝0.001 Systolic BP (mm Hg)2 123.3앐 17.7 122.2앐 17.4 121.9앐 17.7 쏝0.001 Diastolic BP (mm Hg)2 75.5앐 11.3 75.6앐 11.4 75.8앐 11.8 0.312 Fasting glucose (mg/dL)2 100.2앐 22.7 101.5앐 28.9 100.0앐 24.7 쏝0.001 TCHOL (mg/dL)2 203.1앐 37.8 203.4앐 40.2 200.5앐 40.0 쏝0.001 Triacylglycerol (mg/dL)2 136.6앐 105.1 160.9앐 158.9 180.8앐 187.8 쏝0.001 HDL-C (mg/dL)2 43.5앐 14.1 41.5앐 15.0 41.3앐 16.5 쏝0.001 Diabetes [n (%)]4 2225 (5.0) 330 (5.9) 306 (5.1) 0.012 Hypertension [n (%)]4 9876 (22.2) 1090 (19.6) 1191 (19.9) 쏝0.001 Alcohol drinking [n (%)]4 쏝0.001 Never 30 513 (71.3) 2111 (39.7) 1833 (32.4) Former 2054 (4.8) 685 (12.9) 231 (4.1) Current 10 238 (23.9) 2522 (47.4) 3587 (63.5) Smoking [n (%)]4 쏝0.001 Never 24 682 (56.7) 567 (10.5) 573 (10.0) Former 5204 (12.0) 1064 (19.7) 376 (6.6) Current 13 626 (31.3) 3770 (69.8) 4783 (83.4) Physical activity [n (%)]4 쏝0.001 None or mild 18 010 (41.8) 2857 (54.8) 3263 (59.6) Moderate 17 235 (40.0) 1632 (31.3) 1601 (29.3) Vigorous 7805 (18.1) 721 (13.8) 609 (11.1) Income [n (%)]4 쏝0.001 Low 12 150 (28.3) 1900 (35.8) 1861 (33.0) Middle 25 884 (60.3) 3051 (57.6) 3379 (59.9) High 4857 (11.4) 350 (6.6) 402 (7.1) Education [n (%)]4 쏝0.001 Low 6198 (14.1) 1082 (19.8) 1242 (21.3) Middle 12 874 (29.3) 2953 (54.2) 3412 (58.5) High 24 826 (56.6) 1416 (26.0) 1176 (20.2)

1WC, waist circumference; BP, blood pressure; TCHOL, total cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol. 2ANOVA was used for comparing mean values of continuous variables between groups.

3x 앐 SD (all such values).

4Pearson chi-square test was used for categorical data.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

no use of betel nuts, respectively, at baseline survey.

Further-more, current betel nut chewers were divided into 2 groups

ac-cording to the frequency of use: those who reported chewing

betel nut 1– 6 times/wk and those who reported chewing it

욷7

times/wk. Current, former, and never smokers were defined as

those who reported current use, prior use, and no use of cigarette

smoking, respectively. Current, former, and never drinkers of

alcohol were defined as those who reported current use, prior use,

and no use of alcohol, respectively. Physical activity was divided

into 3 levels: none to mild (exercised

쏝1 h/wk), moderate

(ex-ercised 1– 4 h/wk), and vigorous (ex(ex-ercised

쏜5 h/wk) physical

activity. Income was divided into 3 levels: low (

쏝$12 500/y;

US$1

҃ 32 New Taiwan dollars), middle ($12 500–$37 500/y),

and high (

쏜$37 500/y). Education was also divided into 3 levels:

low (elementary school and below), middle (junior and senior

high school), and high (college or university and above).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the means and SDs for continuous

variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was assessed before

further analyses, and log transformation was used for variables

with significant deviation from normal distribution. Student’s t

TABLE 2

Baseline characteristics by survival status and causes of death1

Survivors (n҃ 54 567) CVD deaths (n҃ 309) All-cause deaths (n҃ 1549) Age (y)2 42.2앐 13.63 64.5앐 12.34 62.0앐 13.44 Height (cm)2 168.7앐 6.2 164.7앐 6.14 165.1앐 6.14 Body weight (kg)2 67.7앐 10.4 65.4앐 10.74 64.1앐 10.94 BMI (kg/m2)2 23.8앐 3.3 24.1앐 3.4 23.5앐 3.44 WC (cm)2 81.7앐 9.7 86.5앐 9.84 84.2앐 10.74 Systolic BP (mm Hg)2 122.7앐 17.3 142.3앐 24.64 135.6앐 23.84 Diastolic BP (mm Hg)2 75.5앐 11.3 81.6앐 13.64 78.5앐 13.04 Fasting glucose (mg/dL)2 99.9앐 22.6 117.3앐 43.94 113.8앐 45.54 TCHOL (mg/dL)2 202.8앐 38.1 215.2앐 43.44 204.6앐 45.1 Triacylglycerol (mg/dL)2 143.5앐 122.9 164.9앐 149.85 152.0앐 144.56 HDL-C (mg/dL)2 43.0앐 14.4 42.5앐 16.9 43.1앐 16.8

Betel nut chewing [n (%)]7

Never 43 345 (79.4) 246 (79.6) 1220 (78.8) Former 5402 (9.9) 31 (10.0) 166 (10.7) Current 5820 (10.7) 32 (10.4) 163 (10.5) Smoking [n (%)]7 Never 25 275 (47.6) 112 (37.7)4 547 (36.4)4 Former 6356 (12.0) 64 (21.5) 288 (19.2) Current 21 512 (40.5) 121 (40.7) 667 (44.4)

1WC, waist circumference; BP, blood pressure; TCHOL, total cholesterol; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Statistical analysis

was performed to compare variables between survivors and CVD deaths and between survivors and all-cause deaths.

2Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables. 3x 앐 SD (all such values).

4P쏝 0.001. 5P쏝 0.01. 6P쏝 0.05.

7Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categorical data.

TABLE 3

Relative risks (and 95% CIs) of betel nut chewing for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality in several different models using Cox proportional hazards regression analyses adjusted for some potential confounders

Betel nut chewing Mortality Model 11 Model 22 Model 33

Never CVD 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference)

Former CVD 1.79 (1.23, 2.62)4 1.62 (1.06, 2.47)5 1.56 (1.02, 2.38)5

Current CVD 2.02 (1.39, 2.95)6 2.01 (1.30, 3.10)4 2.02 (1.31, 3.13)4

Never All-cause 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference) 1.00 (reference)

Former All-cause 1.78 (1.51, 2.10)6 1.22 (1.30, 1.75)6 1.40 (1.17, 1.68)6

Current All-cause 1.85 (1.57, 2.19)6 1.21 (1.28, 1.78)6 1.40 (1.16, 1.70)4 1Adjusted for age and BMI.

2Adjusted for age, BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity status, income, and education level.

3Adjusted for age, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triacylglycerol, alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity

status, income, and education level.

4P쏝 0.01. 5P쏝 0.05. 6P쏝 0.001.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

test for unpaired data was used to compare mean values between

2 groups. Proportions and categorical variables were tested by

the chi-square test and by the 2-tailed Fisher’s exact method

when appropriate. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses

adjusted for possible confounders were used to estimate the

rel-ative risks (RRs) for CVD and all-cause mortality. Survival

curves adjusted for other covariates were drawn for current and

never betel nut chewers, never smokers, and never betel nut

chewers, respectively (21, 22). These statistical analyses were

performed by using SPSS statistical software (version 13.0;

SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

There were 1549 deaths over 8 y of follow-up; of these deaths,

309 were due to CVD. At the baseline survey, there were 44 565

(79.4%) never chewers, 5568 (9.9%) former chewers, and 5983

(10.7%) current betel nut chewers. The current betel nut chewers

were younger and had higher BMI, waist circumference, and

triacylglycerol than did never chewers, as is shown in Table 1.

There was a higher proportion of smoking and alcohol

consump-tion among current and former betel nut chewers than among

never chewers. As shown in Table 2, participants who died of

CVD were older and had greater waist circumference, higher

systolic and diastolic BP, and fasting glucose, total cholesterol,

and triacylglycerol concentrations than did survivors.

Partici-pants who died of any cause also were older and had greater waist

circumference, higher systolic and diastolic BP, and higher

fast-ing glucose and triacylglycerol concentrations than did

survi-vors.

Using Cox proportional hazards regression analyses with

ad-justment for potential confounders, the RRs for CVD and

all-cause mortality were higher among current and former betel nut

chewers than among never chewers (Table 3). Among the 3

models, there was no interaction (P

쏜 0.05) between betel nut

chewing and smoking status for predicting the risk of CVD and

all-cause mortality. The adjusted RRs for CVD and all-cause

mortality were 1.56 (95% CI: 1.02, 2.38) and 1.40 (1.17, 1.68) in

former users and 2.02 (1.31, 3.13) and 1.40 (1.16, 1.70) in current

users, respectively (model 3 in Table 3).

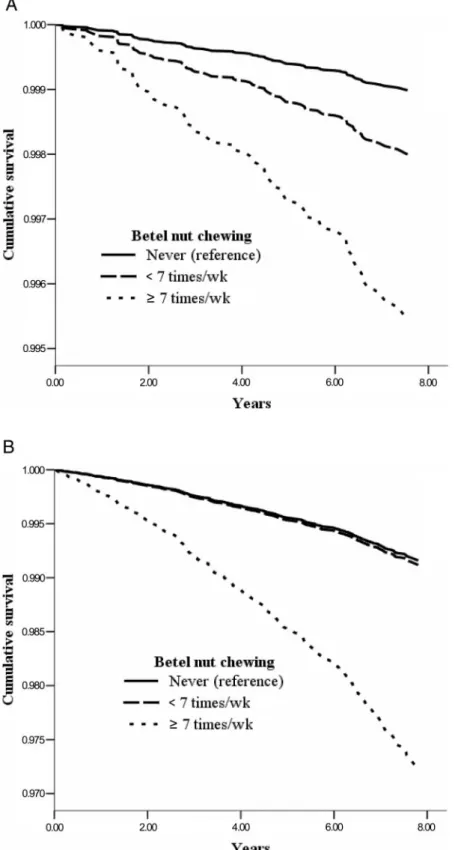

Among the current and never chewers, increased frequency of

betel nut chewing was associated with greater CVD and all-cause

mortality. The adjusted RRs for CVD and all-cause mortality

were higher among those who currently chewed betel nut

욷7

times/wk than among those who currently chewed betel nut

쏝7

times/wk and the never chewers (Figure 1). The adjusted RRs for

CVD and all-cause mortality among the current chewers who

chewed

욷7 times/wk were 2.37 (1.07, 5.23) and 2.18 (1.53,

3.10), respectively, compared with those who chewed

쏝7 times/

wk. Similarly, among the never smokers, the adjusted RRs for

CVD and all-cause mortality were also higher among those who

currently chewed betel nut

욷7 times/wk than among those who

currently chewed betel nut

쏝7 times/wk and never chewers

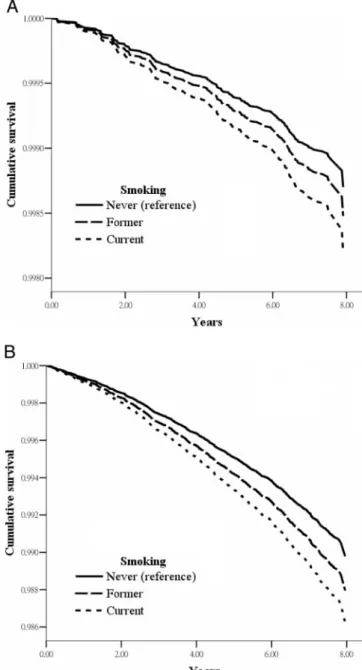

(Fig-ure 2). Among the never chewers, the adjusted RRs for CVD and

all-cause mortality in the current smokers were higher than that

among the never smokers (Figure 3).

The adjusted RRs for CVD and all-cause mortality among

various combinations of smoking and betel nut chewing status

are shown in Table 4. Current and former betel nut chewers had

higher risks of CVD (RR: 2.10; P

҃ 0.05) and all-cause (RR:

1.19; P

҃ 0.354) mortality than did current and former smokers.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based prospective study, we showed that

betel nut chewing was associated with greater CVD and all-cause

mortality in Taiwanese men. Similarly, Lan et al (4) showed that

areca nut chewing is associated with greater CVD and all-cause

mortality in the Taiwanese elderly. In addition, we also found

FIGURE 1. Survival curves for current and never chewers (n҃ 50 548)

after adjustment for other covariates. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were adjusted for age, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, total choles-terol, HDL cholescholes-terol, triacylglycerol, alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity status, income, and education level. A: The adjusted relative risk (RR) (and 95% CIs) for CVD mortality among subjects who currently chewed betel nut욷7 times/wk and 쏝7 times/wk was 2.77 (1.58, 4.88) and 1.55 (0.86, 2.80), respectively, compared with those who never chewed. B: The adjusted RR for all-cause mortality among subjects who currently chewed betel nut욷7 times/wk and 쏝7 times/wk was 2.02 (1.57, 2.60) and 1.09 (0.84, 1.42), respectively, compared with those who never chewed.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

FIGURE 2. Survival curves for never smokers (n҃ 25 822) after adjustment for other covariates. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were

adjusted for age, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triacylglycerol, alcohol consumption, physical activity status, income, and education level. A: The adjusted relative risk (RR) (and 95% CIs) for CVD mortality among subjects who currently chewed betel nut욷7 times/wk and 쏝7 times/wk was 4.49 (1.04, 19.5) and 1.98 (0.47, 8.36), respectively, compared with those who never chewed. B: The adjusted RR for all-cause mortality among subjects who currently chewed betel nut욷7 times/wk and 쏝7 times/wk was 3.34 (1.63, 6.84) and 1.05 (0.46, 2.38), respectively, compared with those who never chewed.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

that the RRs for CVD and all-cause mortality increased with the

frequency of betel nut chewing. Furthermore, betel nut chewing

was associated with a higher risk of CVD and all-cause mortality

than was smoking. Betel nut chewing, therefore, has become a

big challenge to public health in Taiwan as well as in other areas

with high prevalence of betel nut chewing.

Although most of the world’s betel nut chewers are in Asia (2),

the growing number of immigrants from Asia to Europe and

North America means that betel nut chewing is becoming a

global problem. The number of betel nut chewers has been

esti-mated at up to 600 million worldwide (3). Previous studies have

clearly shown arecal alkaloids to be carcinogens, which increase

the risk of various cancers of the oral cavity, esophagus, and liver

(3, 8, 9, 23, 24). In addition, betel nut chewing has been found to

be associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and

chronic kidney disease (13, 14, 16, 25). Although these diseases

are closely related to the development of CVD, the relation

be-tween betel nut chewing and CVD remains unclear.

In the present study, we found that current and former betel

nut chewers had greater CVD mortality than did never

chew-ers. Furthermore, betel nut chewing and smoking were

inde-pendently associated with CVD mortality. We also found that

current and former betel nut chewers had a higher risk of CVD

mortality (RR: 2.10; P

쏝 0.05) than did current and former

smokers. Moreover, the RRs for CVD and all-cause mortality

increased with the frequency of betel nut chewing. Therefore,

betel nut chewing should be treated as a major risk factor

for CVD. Developing a cessation program should be

consid-ered as an intervention strategy for CVD among betel nut

chewers.

Several possible mechanisms may explain the relation

be-tween betel nut chewing and greater CVD mortality. First,

betel nut chewing appears to activate the sympathetic nervous

system, thereby inducing the secretion of adrenal

cathe-cholamines (1, 26). Second, arecal alkaloids act as inhibitors

of

␥-aminobutyric acid receptor. The blockade of the

inhibi-tory effects of

␥-aminobutyric acid on glucagon and

soma-totrophin may result in the secretion of glucagon and

subse-quently in the development of diabetes. Greater appetite and

glucose intolerance due to

␥-aminobutyric acid inhibition and

diabetogenic arecal nitrosamines may also play an important

role in the development of diabetes (1, 11, 13, 14, 25, 27, 28).

Third, betel nut chewing enhances oxidative stress, which

increases the risk of CVD (29, 30). Fourth, betel nut chewing

may induce periodontal disease, which is a chronic

inflam-matory disease with T cell activation and production of

in-flammatory mediators (31). Among these factors, interleukin-6

and tumor necrosis factor-

␣ are proinflammatory cytokines

re-lated to the development of CVD (32–34). It is interesting that, in

a meta-analysis of 9 cohort studies, Janket et al (35) showed that

persons with periodontal disease have a greater incidence of

CVD than do those without periodontal disease. Therefore, the

complex pathogenesis of CVD related to betel nut chewing

de-serves further study.

Although we have shown that betel nut chewing is associated

with a greater risk of CVD and all-cause mortality, the present

study has some limitations. First, the questionnaires were lacking

in details about betel use, such as the numbers of quids used per

day, the duration of the habit, and the preparation used.

There-fore, the exact duration and cumulative exposure of betel nut

could not be quantified in the present study. Similar limitations

were noted for smoking status. Second, our study population was

drawn from generally healthy volunteers who attended health

screening centers rather than from nationally representative

sub-jects. External validation is necessary in future studies. Third, the

fact that only baseline data for these participants were available

may have led to possible misclassifications of betel nut chewing

status during follow-up.

FIGURE 3. Survival curves for never chewers of betel nut (n҃ 44 565)

after adjustment for other covariates. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were adjusted for age, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, total choles-terol, HDL cholescholes-terol, triacylglycerol, alcohol consumption, physical ac-tivity status, income, and education level. A: The adjusted relative risk (RR) (and 95% CIs) for CVD mortality among subjects who were current and former smokers was 1.39 (1.01, 1.91) and 1.17 (0.82, 1.68), respectively, compared with those who never smoked. B: The adjusted RR for all-cause mortality among subjects who were current and former smokers was 1.35 (1.17, 1.56) and 1.18 (1.00, 1.39), respectively, compared with those who never smoked.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

In conclusion, we have shown betel nut chewing to be

inde-pendently associated with greater CVD and all-cause mortality

after control for possible confounders in Taiwanese men. The

RRs for CVD and all-cause mortality increased with the

fre-quency of betel nut chewing. Furthermore, betel nut chewing had

a greater risk of CVD mortality than did smoking. At the national

level, it is crucial to develop a special program to help betel nut

chewers quit their habit. For physicians and other health workers,

it is important to screen people for betel nut chewing in their

clinical practices. Furthermore, the detailed relation between

betel nut chewing and CVD requires further investigation.

We thank T-C Lee (Graduate Institute of Chinese Medicine Science, China Medical University) for her help with respect to statistics.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—W-YL: the study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript draft; T-YC: participated in the data collection and study design; L-TL and C-CL: assisted in data manage-ment and interpretation of results; C-YH: contributed to the concepts inves-tigated and statistical analyses; K-CH: synthesized the analyses and was responsible for the writing of the manuscript; and all authors: approved the final manuscript. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Boucher BJ, Mannan N. Metabolic effects of the consumption of Areca catechu. Addict Biol 2002;7:103–10.

2. Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol 2002;7:77– 83.

3. IARC Working Group on the Evaluatin of Carcinogenic Risks to Hu-mans. Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 2004;85:1–334. 4. Lan TY, Chang WC, Tsai YJ, Chuang YL, Lin HS, Tai TY. Areca nut chewing and mortality in an elderly cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:677– 83.

5. Wollina U, Verma S, Parikh D, Parikh A. [Oral and extraoral disease due to betel nut chewing]. Hautarzt 2002;53:795–7 (in German). 6. Zhang X, Reichart PA. A review of betel quid chewing, oral cancer and

precancer in Mainland China. Oral Oncol 2007;43:424 –30.

7. Sciubba JJ. Oral cancer. The importance of early diagnosis and treat-ment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001;2:239 –51.

8. Tsai JF, Jeng JE, Chuang LY. Habitual betel quid chewing and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis. Medicine 2004;83: 176 – 87.

9. Wu IC, Lu CY, Kuo FC, et al. Interaction between cigarette, alcohol and betel nut use on esophageal cancer risk in Taiwan. Eur J Clin Invest 2006;36:236 – 41.

10. Hsiao TJ, Liao HW, Hsieh PS, Wong RH. Risk of betel quid chewing on the development of liver cirrhosis: a community-based case-control study. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:479 – 85.

11. Yen AM, Chiu YH, Chen LS, et al. A population-based study of the

association between betel-quid chewing and the metabolic syndrome in men. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1153– 60.

12. Chung FM, Chang DM, Chen MP, et al. Areca nut chewing is associated with metabolic syndrome: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, leptin, and white blood cell count in betel nut chewing-related metabolic de-rangements. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1714.

13. Chang WC, Hsiao CF, Chang HY, et al. Betel nut chewing and other risk factors associated with obesity among Taiwanese male adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:359 – 63.

14. Tung TH, Chiu YH, Chen LS, Wu HM, Boucher BJ, Chen TH. A population-based study of the association between areca nut chewing and type 2 diabetes mellitus in men (Keelung Community-based Inte-grated Screening Programme no. 2). Diabetologia 2004;47:1776 – 81. 15. Guh JY, Chen HC, Tsai JF, Chung LY. Betel-quid use is associated with

heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1229 –35.

16. Kang IM, Chou CY, Tseng YH, et al. Association between betelnut chewing and chronic kidney disease in adults. J Occup Environ Med 2007;49:776 –9.

17. Thom TJ. International mortality from heart disease: rates and trends. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:S20 – 8.

18. Taiwan Public Health Report 1998-2000. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Health, 2001.

19. Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA 2002;288:2709 –16.

20. Huang KC, Lin WY, Lee LT, et al. Four anthropometric indices and cardiovascular risk factors in Taiwan. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:1060 – 8.

21. Lee ET, Go OT. Survival analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health 1997;18:105–34.

22. Ghali WA, Quan H, Brant R, et al. Comparison of 2 methods for calcu-lating adjusted survival curves from proportional hazards models. JAMA 2001;286:1494 –7.

23. Ko YC, Huang YL, Lee CH, Chen MJ, Lin LM, Tsai CC. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:450 –3.

24. Thomas SJ, Bain CJ, Battistutta D, Ness AR, Paissat D, Maclennan R. Betel quid not containing tobacco and oral cancer: a report on a case-control study in Papua New Guinea and a meta-analysis of current evidence. Int J Cancer 2007;120:1318 –23.

25. Guh JY, Chuang LY, Chen HC. Betel-quid use is associated with the risk of the metabolic syndrome in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1313–20. 26. Chu NS. Neurological aspects of areca and betel chewing. Addict Biol

2002;7:111– 4.

27. Okamoto H. [Molecular mechanism of degeneration, oncogenesis and regeneration of pancreatic beta-cells of islets of Langerhans]. Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi 1988;77:1147–56 (in Japanese).

28. Okamoto H. Degeneration, oncogenesis and regeneration of pancreatic beta-cells of islets of Langerhans. Nippon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi 1988; 64:1236 –7.

29. Lai KC, Lee TC. Genetic damage in cultured human keratinocytes stressed by long-term exposure to areca nut extracts. Mutat Res 2006; 599:66 –75.

TABLE 4

Relative risks (and 95% CIs) among the various combinations of smoking and betel nut chewing status for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality using Cox proportional hazards regression analyses1

CVD All-cause

Never smoking and never betel nut chewing (n҃ 24 682) 1.00 (Reference) 1.00 (Reference) Former smoking and never betel nut chewing (n҃ 5204) 1.17 (0.81, 1.67) 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) Current smoking and never betel nut chewing (n҃ 13 626) 1.27 (0.92, 1.74) 1.30 (1.13, 1.49)2

Current or former betel nut chewing and never smoking (n҃ 1140) 2.91 (1.43, 5.93)3 1.61 (1.11, 2.34)4

Current or former betel nut chewing and current or former smoking (n҃ 9993) 2.03 (1.38, 3.00)2 1.80 (1.52, 2.12)2 1Model adjusted for age, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triacylglycerol, alcohol consumption, physical activity status,

income, and education level. There was no interaction between betel nut chewing and smoking status for predicting the risk of CVD (P҃ 0.192) or all-cause (P҃ 0.087) mortality.

2P쏝 0.001. 3P쏝 0.01. 4P쏝 0.05.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org

30. Molavi B, Mehta JL. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease: molec-ular basis of its deleterious effects, its detection, and therapeutic consid-erations. Curr Opin Cardiol 2004;19:488 –93.

31. Jeng JH, Wang YJ, Chiang BL, et al. Roles of keratinocyte inflammation in oral cancer: regulating the prostaglandin E2, interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha production of oral epithelial cells by areca nut extract and areco-line. Carcinogenesis 2003;24:1301–15.

32. Mellick GD. TNF gene polymorphism and quantitative traits related to cardiovascular disease: getting to the heart of the matter. Eur J Hum Genet 2007;15:609 –11.

33. Gallucci M, Amici GP, Ongaro F, et al. Associations of the plasma interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels with disability and mortality in the elderly in the Treviso Longeva (Trelong) study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2007; 44(suppl):193– 8.

34. Liu Y, Berthier-Schaad Y, Fallin MD, et al. IL-6 haplotypes, inflamma-tion, and risk for cardiovascular disease in a multiethnic dialysis cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:863–70.

35. Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003;95:559 – 69.

at National Taiwan Univ. Hospital on October 8, 2009

www.ajcn.org