R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

Factors and symptoms associated with work

stress and health-promoting lifestyles among

hospital staff: a pilot study in Taiwan

Yueh-Chi Tsai

1,2and Chieh-Hsing Liu

2*Abstract

Background: Healthcare workers including physicians, nurses, medical technicians and administrative staff experience high levels of occupational stress as a result of heavy workloads, extended working hours and

time-related pressure. The aims of this study were to investigate factors associated with work stress among hospital staff members and to evaluate their health-promoting lifestyle behaviors.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study from May 1, 2010 to July 30, 2010 and recruited 775 professional staff from two regional hospitals in Taiwan using purposive sampling. Demographic data and self-reported symptoms related to work-related stress were collected. Each subject completed the Chinese versions of the Job Content Questionnaire (C-JCQ) and The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLSP). Linear and binary regression analyses were applied to identify associations between these two measurements and subjects’ characteristics, and associations between the two measurements and stress symptoms.

Results: Self-reported symptoms of work-related stress included 64.4% of subjects reporting nervousness, 33.7% nightmares, 44.1% irritability, 40.8% headaches, 35.0% insomnia, and 41.4% gastrointestinal upset. C-JCQ scores for psychological demands of the job and discretion to utilize skills had a positive correlation with stress-related symptoms; however, the C-JCQ scores for decision-making authority and social support correlated negatively with stress-related symptoms except for nightmares and irritability. All items on the HPLSP correlated negatively with stress-related symptoms except for irritability, indicating an association between subjects’ symptoms and a poor quality of health-promoting lifestyle behaviors.

Conclusions: We found that high demands, little decision-making authority, and low levels of social support were associated with the development of stress-related symptoms. The results also suggested that better performance on or a higher frequency of health-promoting life-style behaviors might reduce the chances of hospital staff developing stress-related symptoms. Our report may contribute to the development of educational programs designed to encourage members of high stress groups among the hospital staff to increase their health-promoting behaviors.

Keywords: Healthcare workers, Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLSP), Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), Occupational stress

* Correspondence:t09010@ntnu.edu.tw

2Department of Health Promotion and Health Education, National Taiwan

Normal University, No. 162, Ho-Ping E. Road, Sec 1, Taipei 106, Taiwan, Republic of China

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2012 Tsai and Liu; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

Healthcare workers in hospitals are exposed to high levels of occupational stress resulting from heavy work-loads, extended working hours and high levels of time pressure. Hospital staff members, including physicians and nurses, are at a higher risk of suffering from depres-sive disorders than is the general population [1]. The hazards associated with the prolonged hours worked by resident physicians and interns have been documented. Depressed residents made 6.2 times as many medication errors per resident month as did residents who were not depressed [2]. Hospital staff nurses who had frequent overtime had difficulties in staying awake on duty and reduced sleep times, and had nearly triple the risk of making an error [3].

Recently, considerable concern about job stress has given rise to a theoretical approach that focuses on a demand-control-support model of job strain, as pro-posed by Karasek et al. This model predicts that job strain will occur when psychological work demands are high and the worker’s job control is low, while a low level of workplace social support will increase the risk of negative health outcomes. The psychological demand dimension relates to "how hard workers work" (mental work load), organizational constraints on task comple-tion, and conflicting demands. Job control, discretion in utilizing ones’ skills, and decision-making authority are measured by a set of questions that assess the level of skill and creativity required on the job and the flexibil-ity permitted the worker in deciding what skills to em-ploy. [4]. A Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) was developed by Karasek et al. based on the demand-control-support model. The model predicts that job strain will occur when the psychological demands of the job are high and the worker’s decision-making lati-tude is low, while a low level of support increases the risk of negative outcomes [4].

A study of nurses in Taiwan, found that occupational stress was associated with young age, marital status (widowed/divorced/separated), high psychological de-mand, low workplace support, and threat of assault at work. A lower score for general health was associated with low job control, high psychological demand, and perceived occupational stress. A lower mental health score was associated with low job control, high psycho-logical demand, low workplace support, and perceived occupational stress [5].

While the JCQ is able to evaluate psychosocial aspects of workplace stress, it does not consider individual per-sonalities or lifestyle factors that may influence responses to those stressors. Job stress has been linked to a range of adverse physical and mental health out-comes, such as cardiovascular disease, insomnia, depres-sion, and anxiety [6]. Increasing employee participation

and control through workplace reorganization based on the "demand-control-support" model improved both psychological and physical health [7].

Health-promoting behaviors were described by Walker et al. as behaviors that were directed toward sustaining or increasing the individual’s level of well-being, self-actualization and personal fulfillment [8]. A Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile (HPLSP) scale was developed by Walker based on this concept [8]. Pender suggested that health-protecting (preventive) and health-promoting behaviors might be viewed as complementary compo-nents of a healthy life-style and proposed the Health Pro-motion Model as a paradigm for explaining health promoting behavior. Health-protecting behavior, an ex-pression of the stabilizing tendency of humans, is direc-ted toward decreasing the individual’s probability of encountering illness [9]. A study conducted by Lee et al. found that nurses in Taiwan had a high level of work pressure but they had better strategies for coping with stress as well. On the HPLSP, self-actualization and health responsibility correlated negatively with work stresses. [10].

The present study proposed that, for the professional staff in a hospital, the extent of job stress (measured by the JCQ) and performance in health-promoting lifestyle (measured by HPLSP) may correlate with stress-related symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has examined the correlations among the factors related to stress in a cross section of hospital staff professionals.

Methods

Participants

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 1069 subjects who worked in regional hospitals in Chia-Yi and Hsin-Chu in Taiwan, were selected based on purposively sam-pling (deliberate, non-random samsam-pling of the target population) from May 1st, 2010 to July 30th, 2010. The retrieval rate was 72.5% (775/1069) and 467 subjects were in Chia-Yi and 308 subjects in Hsin-Chu. After the study was explained to participants, all subjects provided written informed consent. The institutional review boards of the two hospitals approved the study protocol.

Measurements

The participants were asked to complete a self-reported questionnaire about basic characteristics including job, marriage, education, location of hospital, length of work experience, average number of hours worked per day and symptoms related to work-related stress. These symptoms were chosen based on related articles in the literature [11-13] and discussion by a panel of experts. Cronbach’s α coefficient for this part of the question-naire was 0.87. Participants were also asked to complete

two questionnaires: the Chinese version of Karasek’s Job Content Questionnaire (C-JCQ) [14] and the HPLSP [15].

Instruments

The C-JCQ [14] is a modification of the scale originally developed by Karasek et al. [4]. It consists of three dimensions: psychosocial work demands (5 items), job control (skill discretion, decision-making authority; 9 items), and workplace social support (coworker social support, supervisor social support; 8 items). Each item is measured on a four-point Likert scale (1: strongly dis-agree to 4: strongly dis-agree). Cronbach’s α coefficient for the work demands subscale was 0.71, while those for the job control and workplace social support subscales were 0.69 and 0.81, respectively. Overall Cronbach's α was 0.72, and only those items with a Content Validity Index (CVI) over 0.8 were included in the final version of the C-JCQ.

A short form of the Chinese version of the HPLSP scale was developed by Wei & Lu in 2005 [15] as a modification of the HPLP scale originally designed by Walker et al. [8]. The scale consists of a set of 24 items that assess six dimensions of healthy behavior: Self-actualization, Health responsibility, Nutrition, Exercise, Interpersonal support, and Stress management. The Chinese version of the scale uses a four-point self-reported Likert scale scored as “never” (1), “sometimes” (2), “usually” (3), or “always” (4) to determine the fre-quency of reported behaviors. Internal reliability for the total scale was previously determined to be 0.90 with a range of 0.63 to 0.79 for the subscales [15].

Statistical analysis

Subjects’ characteristics were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and count (n) with percentage (%) for categorical variables. Measurements on the JCQ and HPLSP were represented as mean ± SD and range (min. - max.) Spearman’s correl-ation analysis, point biserial correlcorrel-ation analysis, and point multiserial correlation analysis were utilized to show the coefficients of correlation. Binary logistic re-gression analysis was also utilized to identify symptoms of work-related stress while considering subjects’ charac-teristics, JCQ, and HPLSP. All statistical assessments were considered significant at p < 0.05. Statistical ana-lyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Among the 775 subjects, 107 were male and 668 were female. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and stress-related symptoms of the 775 subjects. Overall, 376 (48.5%) worked as nursing staff, 248 (32%) as

administrative staff, 116 (15%) as medical technicians, and 35 (4.5%) as physicians. Among all subjects, 400 (51.6%) were married and 360 (46.5%) were single; 669 (86.3%) had completed college or university. The average work experience of all subjects was 9.88 years (SD = 6.46) and the time period of average daily work was 8.77 hours (SD = 1.66). For self-reported symptoms of work-related stress, 499 (64.4%) of the subjects reported being nervous, 261 (33.7%) had nightmares, 342 (44.1%) had irritability, 316 (40.8%) had headache, 271 (35.0%) had insomnia, and 342 (41.4%) had gastrointestinal upset.

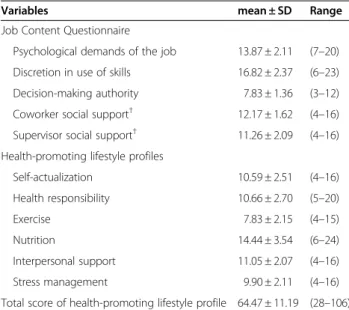

Table 2 summarizes the measurements from the C-JCQ and HPLSP questionnaires. Average scores for each sub-category of the C-JCQ were: 13.87 ± 2.11 for psychological demands on the job, 16.82 ± 2.37 for dis-cretion in use of skills, 7.83 ± 1.36 for decision-making authority, 12.17 ± 1.62 for coworker social support, and 11.26 ± 2.09 for supervisor social support. The outcomes on HPLSP measurement showed that both exercise

Table 1 Subjects’ demographic characteristics and work-related symptoms (N = 775)

Variables (N = 775)

Job position

Physician 35 (4.5)

Nurse 376 (48.5)

Medical technician staff 116 (15.0)

Administrative staff 248 (32.0) Marriage status Married 400 (51.6) Not married 360 (46.5) Other 15 (1.9) Education High school 59 (7.6) College or University 669 (86.3) Master’s or PhD 47 (6.1) Location of hospital Chai-Yi 467 (60.3) Hsin-Chu 308 (39.7)

Work experience, years 9.88 ± 6.46

Daily work time, hours 8.77 ± 1.66

Symptoms of work-related stress

Nervousness 499 (64.4) Nightmares 261 (33.7) Irritability 342 (44.1) Headaches 316 (40.8) Insomnia 271 (35.0) Gastrointestinal upset 321 (41.4)

Data are represented as n (%) for categorical variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables.

(7.83 ± 2.15) and stress management (9.90 ± 2.11) had relatively low scores. The total score for health-promoting life-style reached only 64.47 ± 11.19 with a range from 28 to 106.

Table 3 shows the correlations between subjects’ char-acteristics and C-JCQ categories. The results show that gender was positively correlated with psychological demands, but negatively correlated with discretion in use of skills as female staff had greater psychological demands but less discretion in their use of skills. Job position ranked in the order of physicians, nurses, med-ical technician staff and administrative staff was nega-tively correlated with psychological demands, discretion in use of skills and decision-making authority, as physi-cians had greater psychological demands, discretion in

their use of skills and decision-making authority than did nurses, followed by medical technician staff, and ad-ministrative staff.

Longer work experience was positively correlated with discretion in use of skills and decision-making authority but showed a negative correlation with coworker social support and supervisor social support. (Table 3) Daily work times were positively correlated with psychological demands, discretion in use of skills and decision-making authority. (Table 3)

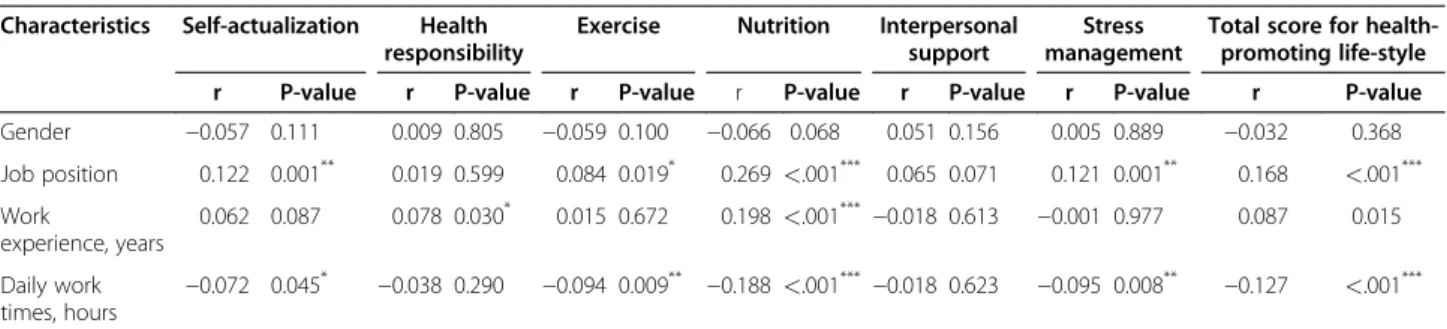

The correlation of subjects’ characteristics with HPLSP categories is shown in Table 4. The total HPLSP score was positively correlated with job position (r = 0.168, P < 0.001) but negatively correlated with daily work time (r=−0.127, P < 0.001). Physicians had the lowest score in HPLSP among the four positions, followed by nurses, medical technician staff, and administrative staff in that order.

Among the subcategories of HPLSP, most (Self-actualization, Exercise, Nutrition, Stress management) were positively correlated with job position. Physicians had less self-actualization, fewer chances to exercise, cared less about nutrition, and did not manage stress well. They were followed by nurses, medical technician staff, and administrative staff in that order. (Table 4) Health responsibility and interpersonal support were positively correlated with work experience, as staff with longer work experience took greater health responsibility and had more interpersonal support. Most subcategories (Self-actualization, Exercise, Nutrition, Stress manage-ment) were negatively correlated with daily work times, as staff who worked longer had less self-actualization, did less exercise, cared less about nutrition, and did not manage stress well. (Table 4)

Table 5 shows the association between subjects’ char-acteristics (gender, job, work experience, daily work time), C-JCQ and HPLSP scores, and stress symptoms as determined by binary logistic regression analysis. Fe-male workers had more stress-related symptoms than did male workers, except for gastrointestinal upset.

Table 2 Summary of measurements on Job Content Questionnaires (JCQ) and health-promoting lifestyle profile (HPLSP) for all 755 subjectsa

Variables mean ± SD Range

Job Content Questionnaire

Psychological demands of the job 13.87 ± 2.11 (7–20) Discretion in use of skills 16.82 ± 2.37 (6–23) Decision-making authority 7.83 ± 1.36 (3–12) Coworker social support† 12.17 ± 1.62 (4–16) Supervisor social support† 11.26 ± 2.09 (4–16) Health-promoting lifestyle profiles

Self-actualization 10.59 ± 2.51 (4–16) Health responsibility 10.66 ± 2.70 (5–20) Exercise 7.83 ± 2.15 (4–15) Nutrition 14.44 ± 3.54 (6–24) Interpersonal support 11.05 ± 2.07 (4–16) Stress management 9.90 ± 2.11 (4–16) Total score of health-promoting lifestyle profile 64.47 ± 11.19 (28–106)

a

Data are represented as mean ± SD and range (min. - max.).

†Those two items asked for the need for social support. In other words, a

higher score stands for not enough social support from either coworkers or supervisor.

Table 3 Correlation of Job Content Questionnaire with subjects’ characteristics (N = 755) Psychological Demands of Job Discretion In Use of Skills Decision-making authority Coworker social

supporta Supervisor socialsupporta

r p-value r p-value r p-value r p-value r p-value

Gender .085 0.018* -.127 <.001*** -.057 0.113 .011 0.764 -.015 0.682

Job position -.235 <.001*** -.297 <.001*** -.103 0.004** .014 0.702 -.010 0.785 Work experience, years .002 0.947 .146 <.001*** .115 0.001** -.095 0.008** -.079 0.027* Daily work times, hours .326 <.001*** .296 <.001*** .107 0.003** -.016 0.647 -.033 0.358

r, coefficient of correlation of Job Content Questionnaire with gender was derived through the point biserial correlation analysis (male, 1; female, 2); with job position through the point multiserial correlation analysis (physician, 1; nurse, 2; medical technician staff, 3; administrative staff, 4); with work experience or with daily work times through Spearman’s correlation analysis.

*

P< 0.05,**

P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001, indicate significant correlation between health-promoting life-style profiles and characteristics. a

These two items indicate perceived needs for social support. In other words, a higher score stands for not enough social support from either coworkers or supervisors.

Table 4 Correlation of Health-promoting life-style profiles with subjects’ characteristics (N = 755) Characteristics Self-actualization Health

responsibility

Exercise Nutrition Interpersonal support

Stress management

Total score for health-promoting life-style r P-value r P-value r P-value r P-value r P-value r P-value r P-value Gender −0.057 0.111 0.009 0.805 −0.059 0.100 −0.066 0.068 0.051 0.156 0.005 0.889 −0.032 0.368 Job position 0.122 0.001** 0.019 0.599 0.084 0.019* 0.269 <.001*** 0.065 0.071 0.121 0.001** 0.168 <.001*** Work experience, years 0.062 0.087 0.078 0.030* 0.015 0.672 0.198 <.001*** −0.018 0.613 −0.001 0.977 0.087 0.015 Daily work times, hours −0.072 0.045* −0.038 0.290 −0.094 0.009** −0.188 <.001*** −0.018 0.623 −0.095 0.008** −0.127 <.001*** r, coefficient of correlation of health-promoting life-style profiles with gender was derived through the point biserial correlation analysis (male, 1; female, 2); with job position through the point multiserial correlation analysis (physician, 1; nurse, 2; medical technician staff, 3; administrative staff, 4); with work experience or with daily work times through Spearman’s correlation analysis.

*

P< 0.05,**

P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001, indicate significant correlation between health-promoting life-style profiles and characteristics.

Table 5 Association of subjects’ characteristics, Job Content Questionnaire, and Health-promoting life-style profiles with symptoms of work-related stress through binary logistic regression analysisa

Variables Nervousness Nightmares Irritability Headaches Insomnia Gastrointestinal upset OR (95% CI.) OR (95% CI.) OR (95% CI.) OR (95% CI.) OR (95% CI.) OR (95% CI.) Gender Male 1 1 1 1 1 1 Female 2.56 (1.69– 2.56)* 1.69 (1.05 – 1.69)* 1.92 (1.25 – 1.92)* 1.82 (1.16 – 2.86)* 1.82 (1.12 – 2.86)* 1.33 (0.87 – 2.04) Job Physician 1 1 1 1 1 1 Nurse 2.79 (1.38 - 5.64)* 3.95 (1.60 - 9.73)* 2.45 (1.19 - 5.07)* 4.64 (1.98 - 10.89)* 5.51 (2.09 - 14.51)* 1.50 (0.75 - 3.02) Medical technician staff 1.34 (0.63 - 2.86) 1.76 (0.67 - 4.65) 1.13 (0.51 - 2.50) 1.80 (0.72 - 4.50) 2.29 (0.82 - 6.41) 0.68 (0.31 - 1.46) Administrative staff 1.08 (0.53 - 2.18) 1.38 (0.54 - 3.49) 0.85 (0.40 - 1.79) 1.61 (0.67 - 3.84) 1.67 (0.62 - 4.51) 0.50 (0.24 - 1.04) Work experience, years 0.96 (0.94 - 0.99)* 0.98 (0.95 - 1.00)* 0.97 (0.95 - 0.99) 0.97 (0.95 - 1.00)* 0.97 (0.95 - 1.00)* 0.99 (0.96 - 1.01) Daily work time, hours 1.09 (0.99 - 1.19)* 1.09 (0.99 - 1.19)* 1.06 (0.97 - 1.15) 1.12 (1.02 - 1.23)* 1.07 (0.98 - 1.17) 1.15 (1.05 - 1.27)* Job Content Questionnaire

Psychological demands of job 1.50 (1.37 - 1.63)* 1.39 (1.28 - 1.51)* 1.52 (1.40 - 1.66) 1.49 (1.37 - 1.62)* 1.37 (1.27 - 1.48)* 1.55 (1.42 - 1.69)* Discretion in using skills 1.10 (1.04 - 1.17)* 1.13 (1.06 - 1.21)* 1.04 (0.98 - 1.11) 1.10 (1.03 - 1.17)* 1.07 (1.00 - 1.14)* 1.13 (1.06 - 1.21)* Decision-making authority 0.86 (0.77 - 0.97)* 0.79 (0.71 - 0.89)* 0.76 (0.68 - 0.85) 0.81 (0.72 - 0.90)* 0.83 (0.74 - 0.93)* 0.86 (0.78 - 0.96)* Coworker social support† 0.99 (0.91 - 1.09)* 1.01 (0.92 - 1.11) 0.89 (0.81 - 0.97) 0.89 (0.81 - 0.97)* 0.95 (0.87 - 1.04)* 0.93 (0.85 - 1.02) Supervisor social support† 0.98 (0.92 - 1.06) 0.96 (0.89 - 1.03) 0.83 (0.77 - 0.89) 0.91 (0.85 - 0.98)* 0.92 (0.86 - 0.99)* 0.86 (0.80 - 0.92)* Health-promoting life-style profiles

Self-actualization 0.83 (0.78 - 0.88)* 0.83 (0.78 - 0.88)* 0.78 (0.73 - 0.83) 0.81 (0.76 - 0.86)* 0.79 (0.74 - 0.84)* 0.85 (0.80 - 0.90)* Health responsibility 0.94 (0.89 - 0.99)* 0.94 (0.88 - 0.99)* 0.91 (0.86 - 0.96) 0.92 (0.87 - 0.97)* 0.94 (0.89 - 0.99)* 0.98 (0.93 - 1.03) Exercise 0.89 (0.83 - 0.96)* 0.91 (0.85 - 0.97)* 0.90 (0.84 - 0.96) 0.92 (0.86 - 0.98)* 0.94 (0.88 - 1.01)* 0.93 (0.87 - 0.99)* Nutrition 0.88 (0.84 - 0.92)* 0.89 (0.85 - 0.93)* 0.86 (0.82 - 0.89) 0.86 (0.82 - 0.90)* 0.85 (0.81 - 0.89)* 0.89 (0.85 - 0.93)* Interpersonal support 0.92 (0.86 - 0.99)* 0.86 (0.80 - 0.93)* 0.88 (0.82 - 0.95) 0.88 (0.82 - 0.95)* 0.92 (0.85 - 0.98)* 0.98 (0.91 - 1.04) Stress management 0.85 (0.79 - 0.92)* 0.82 (0.76 - 0.89)* 0.77 (0.71 - 0.83) 0.77 (0.71 - 0.83)* 0.77 (0.71 - 0.83)* 0.82 (0.77 - 0.89)* Total score of health-promoting life-style 0.96 (0.95 - 0.98)* 0.96 (0.95 - 0.97)* 0.95 (0.94 - 0.96) 0.95 (0.94 - 0.97)* 0.95 (0.94 - 0.97)* 0.97 (0.96 - 0.98)* a

Results are represented as estimated odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI.) on binary logistic regression analysis. *P < 0.05 for estimated OR.

Participants with longer work experience had a signifi-cantly higher chance of having stress-related symptoms, except for irritability and gastrointestinal upset. Partici-pants with longer daily work times had more stress-related symptoms, except for irritability and insomnia.

For C-JCQ items, scores on psychological demands of the job and decisions to utilize skills had a positive cor-relation with stress-related symptoms, except for irrit-ability; however, decision-making authority scores had a negative correlation with stress-related symptoms, ex-cept for irritability. Both the scores for coworker social support and supervisor social support had negative cor-relations with stress-related symptoms except for night-mares and irritability. All items on the health-promoting life-style profiles had a negative correlation with stress-related symptoms, except for irritability.

Discussion

High job demands, little decision-making authority, and low social support were associated with the development of stress-related symptoms. Relationships were also shown between job category and dimensions of the JCQ. Male workers had fewer psychological demands on the job than did females but had greater discretion in utiliz-ing their skills. Hospital nursutiliz-ing staff, medical techni-cians and administrative staff had significantly less discretion in utilizing their skills and decision-making authority than did physicians. Longer work experience was associated with significantly higher discretion in utilizing skills and decision-making authority among all workers. Longer daily work times were associated with significantly higher psychological demands on the job, discretion in utilizing skills, and decision-making author-ity. Psychological demands on the job were somewhat associated with gender and daily work time. In terms of symptoms, being female, having a longer work experi-ence, and working longer hours each day were asso-ciated with significantly greater stress-related symptoms, except for irritability. Nervousness, headache, and, to a lesser extent, gastrointestinal upset were reported more frequently.

Staff responses to HPLSP categories revealed that nurses performed less well in self-actualization and nu-trition categories when compared to other types of workers. Participants with longer work experience per-formed better in self-actualization, health responsibility and nutrition categories. Staff with longer daily work times performed less well in nutrition, indicating that time constraints on the job interfered with their ability to eat well. The total scores for health-promoting life-style indicated that hospital staff did have an interest in health-promoting measures but did not always perform them well. All items on the HPLSP correlated negatively with stress-related symptoms except for irritability,

indicating an association between subjects’ symptoms and their self-reported, low-quality, health-promoting lifestyle behaviors.

As in the study by Shen et al. [5], lower general health scores measured by the JCQ were associated with low job control, high psychological demand, and perceived occu-pational stress. A lower mental health score was asso-ciated with low job control, high psychological demand, low workplace support, and perceived occupational stress. In the present study, low job control was represented by low scores for decision-making authority and discretion in utilization of skills. We found that scores for psychological demands on the job and discretion in utilizing skills corre-lated positively with stress-recorre-lated symptoms while decision-making authority scores correlated negatively with stress-related symptoms.

McElligott et al. [16] examined the health-promoting lifestyle behaviors of acute-care nurses using the Health Promotion Model. Their results showed overall low scores for health-promoting behavior, with particular weaknesses in stress management and physical activity. In our study, we also found that almost all items on the HPLSP correlated negatively with stress-related symp-toms, indicating an association between high-quality health-promoting lifestyle behavior and fewer stress-related symptoms.

In the present study, nurses sensed a lack of social support from peers and supervisors and, in expressing a need for more social support, placed a high value on relationships at work as being an important aspect of the work environment. Work relationships were also cited as a direct source of stress by Hope et al. as hos-pital nurses who experienced high work stress were more apt to seek professional support and the support of family and friends or“having a good cry” [17]. Seeking support from coworkers or supervisors may actually rep-resent health-protecting behavior that could help diffuse the impact of stressors in the workplace. Based on our results regarding the expressed need for support among hospital staff, measures such as conflict resolution and peer support groups could help increase health-promoting skills and thereby reduce the development of stress-related symptoms.

Solutions must fit the problem and different settings have produced different explanations for work-related stress. A recent study by Chen et al. explored job stress and specific stressors along with coping strat-egies and overall job satisfaction among nurses and found that the main stressors were related to the type of hospital, patient safety issues, and administrative feedback. They recommended implementation of standard operating procedures, security measures and increases in the quantity and quality of stress relief courses [18]. Other studies have suggested that

health-promotion skills should be integrated into nursing education. This could have a ripple effect that may improve both the nurses’ own health status and enhance their role as health promotion advocates [17,19].

Many researchers in Taiwan have studied job stress, coping strategies and health promoting behavior among hospital staffs [5,14,18,20,21], and in other occupations [22]. The present study is the first to comprehensively investigate associations between scores on the C-JCQ and HPLSP and stress-related symptoms among hospital staff members in Taiwan.

There are several limitations to our study. First, 48.5% of the subjects worked as nursing staff and only 4.5% as physicians; therefore, nursing staff responses may disproportionally affect the overall scores on the questionnaires, and, to a lesser extent, reflect the job content and life-style profile of male physicians. Second, our study population of 775 healthcare workers was recruited from only two re-gional hospitals, and this may preclude generalization of the results to larger and smaller institutions such as medical centers, local hospitals, and clinics. Third, odds ratios in logistic regression may not be appro-priate for a cross-sectional study, and a prospective study should be conducted in the future. Finally, a fu-ture study will be needed to demonstrate whether a high quality of health-promoting lifestyle can really reduce the stress-related symptoms associated with high demand, low control and low social support.

Conclusions

Little decision-making authority and a lack of social sup-port from either coworkers or supervisors are associated with the development of stress-related symptoms. Better performance in or higher frequency of health-promoting life-style behaviors might reduce the chances of develop-ing stress-related symptoms. We suggest that our results may be useful in the development of educational pro-grams designed to encourage highly stressed hospital staff members to pay more attention to health-promoting lifestyles and to increase health-health-promoting behaviors as protection against the demands of the hos-pital work environment.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authors’ contributions

YC Tsai designed the study, wrote the protocol, managed the literature searches, data acquisition and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Dr. CH Liu was the supervisor for the project, was closely involved in creating the hypothesis and study design, and undertook the manuscript editing and review of the rough draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council (NSC 98-2511-S-003-060) of Taiwan.

Author details 1

Department of Family Medicine, Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei City 10449, Taiwan, Republic of China.2Department of Health Promotion and

Health Education, National Taiwan Normal University, No. 162, Ho-Ping E. Road, Sec 1, Taipei 106, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Received: 11 July 2011 Accepted: 16 July 2012 Published: 16 July 2012

References

1. Alpert JS: Physician depression. Am J Med 2008, 121:643.

2. Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, Edwards S, Wiedermann BL, Landrigan CP: Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008, 336:488–491.

3. Rogers AE, Hughes RG: The Effects of Fatigue and Sleepiness on Nurse Performance and Patient Safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD); 2008. Apr. Chapter 40. Advances in Patient Safety. 4. Karasek R: Brisson, Kawasaki N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B: The Job

Content Questionnaire: an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 1998, 3(4):322–355.

5. Shen HC, Cheng Y, Tsai PJ, Lee SH, Guo YL: Occupational stress in nurses in psychiatric institutions in Taiwan. J Occup Health 2005, 47(3):218–225. 6. Nakao M: Work-related stress and psychosomatic medicine. Biopsychosoc

Med 2010, 4(1):4.

7. Egan M, Bambra C, Thomas S, Petticrew M, Whitehead M: Thomson H. The psychosocial and health effects of workplace reorganisation. 1. A systematic review of organisational-level interventions that aim to increase employee control. Epidemiol Community Health 2007, 61(11):945–954.

8. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ: The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile: development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs Res 1987, 36(2):76–81.

9. Pender NJ, Walker SN, Stromberg MF, Sechrist KR: Predicting health-promoting lifestyles in the workplace. Nurs Res 1990, 39:326–332. 10. Lee WL, Tsai SH, Tsai CW, Lee CY: A study on work stress, stress coping

strategies and health promoting lifestyle among district hospital nurses in Taiwan. J Occup Health 2011, 53(5):377–83.

11. Krantz G, Berntsson L, Lundberg U: Total workload, work stress and perceived symptoms in Swedish make and female white-collar employees. Eur J Public Health 2005, 15(2):209–214.

12. Ekvall Hansson E, Hakansson E, Raushed A, Hakansson A: Multidisciplinary program for stress-related disease in primary health care. J Multidiscip Healthc 2009, 2:61–65.

13. Estryn-Behar M, Kaminski M, Peigne E, Bonnet N, Vaichere E, Gozlan C, Azoulay S, Giorgi M: Stress at work and mental health status among female hospital workers. Br J Ind Med 1990, 47(1):20–28.

14. Wang LJ, Chen CK, Hsu SC, Lee SY, Wang CS, Yeh WY: Active Job, Healthy Job? Occupational stress and depression among hospital physicians in Taiwan. Ind Health 2011, 49:173–184.

15. Wei MH, Lu CM: Development of the short-form Chinese health-promoting liestyle profile. J Health Edu 2005, 24:25–46.

16. McElligott D, Siemers S, Thomas L, Kohn N: Health promotion in nurses: is there a healthy nurse in the house? Appl Nurs Res 2009, 22(3):211–215. 17. Hope A, Kelleher CC, O'Connor M: Lifestyle practices and the health

promoting environment of hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs 1998, 28(2):438–447.

18. Chen CK, Lin C, Wang SH, Hou TH: A study of job stress, stress coping strategies, and job satisfaction for nurses working in middle-level hospital operating rooms. J Nurs Res 2009, 17(3):199–211. 19. Alpar SE, Senturan L, Karabacak U, Sabuncu N: Change in the health

promoting lifestyle behavior of Turkish University nursing students from beginning to end of nurse training. Nurs Ed Prac 2008, 8:382–388.

20. Lin HS, Probst JC, Hsu YC: Depression among female psychiatric nurses in southern Taiwan: main and moderating effects of job stress, coping behaviour and social support. J Clin Nurs 2010, 19(15–16):2342–2354. 21. Chen MY, James K, Wang EK: Comparison of health-promoting behavior

between Taiwanese and American adolescents: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2007, 44(1):59–69.

22. Huang SL, Li RH, Tang FC: Comparing disparities in the health-promoting lifestyles of Taiwanese workers in various occupations. Ind Health 2010, 48(3):256–264.

doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-199

Cite this article as: Tsai and Liu: Factors and symptoms associated with work stress and health-promoting lifestyles among hospital staff: a pilot study in Taiwan. BMC Health Services Research 2012 12:199.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of:

• Convenient online submission • Thorough peer review

• No space constraints or color figure charges • Immediate publication on acceptance

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar • Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit