An Alternative to Reading Instruction: Implementing

Literature Circles in a College-Level EFL Classroom

Wen-Hsin Chen1, Mei-ching Ho2

1National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei 106, Taiwan 2University of Taipei, Taipei 100, Taiwan

Abstract

Many college students in Taiwan learn English because it is a required subject in school, not because of their intrinsic interests. In addition, many of them are not motivated to read English texts both inside and outside the classroom. This paper outlines the use of Literature Circles (LCs) to more effectively engage English language learners in the classroom, enhance their motivation to read and learn English, and improve their literacy skills. Drawing on Harvey Daniels’s (1994) definitions of LCs, this paper delineates the 11 key components of LCs. Special emphasis is placed on the procedure of implementing LCs in a college-level English language course in Taiwan, an EFL context. Moreover, practical suggestions for running LCs and setting up reading and discussion groups are provided, and student roles are discussed. The results suggest that LCs promote active learning among the students and support the students’ literacy learning.

Keywords: Literature Circles, Student-Centered Approach, Second Language Acquisition

閱讀教學的另一項選擇:

文學圈在台灣大學英文課中的運用

陳玟心1、何美靜2 1臺灣 臺北市 106 國立臺北科技大學 2臺灣 臺北市 100 臺北市立大學摘 要

本文概述如何利用文學圈(Literature Circles, LCs)來提升 EFL 英語學習者 的課堂參與度,提高他們閱讀和學習英語的動機,並培養其讀寫能力。本文特 別介紹如何在台灣一所科技大學的英語課中實施 LCs。此外,本文也提供如何 建立閱讀及討論小組的建議,並討論學生在小組中伴演的角色。結果顯示 LCs 可促進EFL 大學生的主動學習,並提升他們的讀寫能力。 關鍵詞:文學圈、以學生為中心教學法、第二語言習得 * 通訊作者:何美靜 通訊地址:100 臺北市中正區愛國西路一號 電子郵件:mch_clair@utaipei.edu.tw DOI:10.6701/TEEJ.201806_65(2).0004

Introduction

In the early 1990s, Harvey Daniels and his colleagues brought the idea of informally talking about stories and literary books into the Reading and Literature courses for L1 students at the elementary and secondary schools in Chicago (Furr, 2004a). He designed an in-class collaborative reading activity, called Literature Circles (LCs), to engage students in collaborative extensive reading. In LCs, students, reading the same literary books or articles, form small discussion groups to share thoughts and interpretations of what they have read (Daniels, 1994, 2002). While reading and discussing texts with peers, students are usually required to take on different roles or carry out different focused tasks in order to facilitate their contributions to the post-reading discussions (Daniels, 1994, 2002; Shelton-Strong, 2012, p. 214).

Since Daniels’ first use of LCs in Language Arts courses in the U.S., many language teachers in L1 settings have taken up, adapted, and employed this student-centered reading activity. Success in implementing LCs in mainstream L1 teaching and its effectiveness in fostering students’ reading skills have been well documented in the prior literature. It has been suggested that engaging students in LCs could not only promote reading but also cultivate their critical thinking skills (Bell, 2003; Liao, 2009). Discussing literary pieces and articles in groups encourages meaning negotiation and sharing of different viewpoints and interpretations of the reading text (Day, 2003; Ketch, 2005). Since LCs are learner-led activities, using them in language arts classes also promotes learner autonomy and guides students towards becoming independent readers (Hsu, 2004; Shelton-Strong, 2012).

Features of LCs

Daniels (1994, 2002) suggests the following 11 key elements of a successful LC for L1 students:

1. Students choose their own reading materials.

2. Small temporary groups are formed based on book choice. 3. Different groups read different books.

4. Groups meet on a regular, predictable schedule to discuss their reading.

5. Students use written or drawn notes to guide both their reading and discussion. 6. Discussion topics come from students.

7. Discussion meetings aim to be open, natural conversations about books, so personal connections, digressions, and open-ended questions are welcome.

8. The teacher serves as a facilitator, not a group member or instructor. 9. Evaluation is by teacher observation and student self-evaluation. 10. A spirit of playfulness and fun pervades the room.

11. When books are finished, readers share with their classmates and then new groups form around new reading choices (2002, p. 18).

Since a number of studies have documented success in implementing LCs in Language Arts classes in L1 settings, many L2/FL researchers and teachers also adapted LCs for use in ESL and EFL contexts in recent years and have found positive results regarding the effectiveness of LCs in enhancing L2/FL learners’ reading skills and learning motivation (see Bedel, 2016; Furr, 2004a, 2004b; Hsu, 2004; Lenters, 2014; Liao, 2009; Morales & Carroll, 2015; Schoonmaker, 2014).

For successful and effective implementation of LCs in ESL/EFL settings, especially when used with students with low to high-intermediate levels of English proficiency, Furr (2004a, 2004b) suggests some modifications in Daniels’ (1994, 2002) model regarding the 11 key elements of LCs. He made changes to the first four elements and proposed a new version:

1. Instructors select materials appropriate for their student population.

2. Small temporary groups are formed, based on student choice or the instructor’s direction.

3. Different groups are usually reading the same text.

may provide additional information to “fill in some of the gaps” in student understanding (i.e., “backloading the instruction”). After the group projects or additional instruction, new groups are formed, based on student choice or the instructor’s discretion (Furr, 2004b, p. 5).

To facilitate students’ participation in meaningful face-to-face discussions about the reading materials, Furr suggests ESL/EFL teachers choose graded reading materials that match learners’ ability and interests (2004b, p. 2). Since participating in LCs usually requires both intensive and extensive reading skills, the reading materials need to be appropriate for extensive reading. According to Furr, one approach to checking whether a text/book is suitable for ESL/EFL learners is to follow Waring and Takahashi’s (2000) recommendation for extensive reading:

Here are some good ‘rules of thumb’ for students to find their reading level: There should be no more than 2-3 unknown words per page. The learner is reading 8-10 lines of text or more per minute. The learner understands almost all of what she is reading with few pauses (Waring & Takahashi, 2000, p. 11). For basic leaners, teachers can consider “a graded reader that is one level below the actual student reading level” since LCs require students to not only read but also discuss the texts in English (Waring & Takahashi, 2000, p. 11). A student who can comprehend the text in general may not be able to engage in group discussions in English with their peers. Therefore, selecting materials one level below learners’ true reading levels makes the LCs manageable and lowers learners’ reading anxiety in an L2/FL (Furr, 2004b). In addition, unlike L1 students, ESL/EFL learners may lack historical or cultural backgrounds of the stories they read. Having all students read the same text/book is the key to assuring a successful LC. When each student reads the same text, teachers can add a mini-lecture after individual small-group discussions to boost students’ curiosity on the questions and topics they have discussed.

Another modification has to do with the grouping of LC discussion groups. It has been suggested that teachers assign students into groups according to their reading levels, interests, and learning styles, instead of having students form groups themselves based on choice of books. Drawing on his own personal teaching experience, Furr (2004a) also points out that in a group of five or six, having at least two stronger learners in each group would help increase the effectiveness of LCs.

Among the 11 key elements of LCs, the fifth component regarding the facilitation of small group discussions is a key one. When implementing LCs in ESL/EFL classrooms, teachers could provide guidance to have students assume difficult roles during discussion. Daniels (1994, 2002) proposed five basic roles for L1 students engaging in LCs (Liao, 2009):

1. Summarizer offers a brief summary of the reading.

2. Question Writer creates a number of questions about reading to increase comprehension.

3. Connector finds a way to connect the reading to his or her own life, world knowledge or other texts.

4. Vocabulary Enricher selects a few words that might be challenging, interesting, or important. He/she needs to provide a definition and an example for each word. 5. Illustrator draws some pictures, diagrams, flow charts, or cartoons that are related

to the reading. (Day, 2003; Liao, 2009, p. 95)

Drawing on Daniels’ model, Furr (2004b) modified some of the five roles and added two additional roles for higher-level thinking and for a more productive discussion group: Discussion Leader and Cultural Collector. Students are usually provided with a role sheet before discussing the readings in groups. The role sheet that Furr (2004b) used with the EFL students in Japan includes the following roles (Shelton-Strong 2012):

1. Discussion Leader: maintains the interaction of the discussion through questions and invitations to participate;

3. Word Master: responsible for choosing new important, or interesting words and multiword expressions to share, define, and contextualize;

4. Passage Person: chooses key passages, explains reasons for choice, and offers and elicits comments;

5. Connector: makes connections between real-life people and events with the story content and prepares questions to invite similar comments;

6. Cultural Collector: looks for cultural similarities and differences between story and own culture and brings them to light, inviting comments through questions to circle members;

7. Artistic Adventurer: draws or creates something to represent an element of the story, sharing and communicating the rationale to the group. (2012, p. 216)

LCs in ESL/EFL contexts

In the past decade, how to effectively integrate LCs into language classes in L2 and FL contexts has gained increasing scholarly attention. A number of studies have explored the use of LCs in ESL/EFL classrooms at primary and secondary schools (e.g., Bains, 2014; Calzada, 2013; Cameron, Murray, Hull, Cameron, 2012; Chen, 2013; Huang, 2016; Maraccini, 2013; McDown, 2012; Thein, Guise, & Sloan, 2011; Tsai, 2017; van Keulen, 2011). However, relatively less research focuses on how LCs facilitate ESL/EFL reading skills at the tertiary level (see Anderson, 2012; Bowers-Campbell, 2011; Fredricks, 2012; Furr, 2004a, 2004b; Heineke, 2014; Hsu, 2004; Huang, 2009; Liao, 2009; Schoonmaker, 2104; Shelton-Strong, 2012; Su & Wu, 2016; Thomas, 2013; Yamin, 2015).

Some prior studies on LCs in ESL/EFL contexts examined the impacts of LCs on several aspects of L2/FL reading, including students’ reading comprehension and motivation, students’ perceptions of reading before and after the implementation of literature circles, and their attitudes towards the LC activity. Others looked at teachers’ perceptions of LCs in ESL/EFL classrooms and still others investigated

students’ challenges and experiences while engaging in LCs. More recently, thanks to the advancement of the information and communication technology (ICT) in education settings, several scholars and researchers have begun to explore the effects of participating in virtual LCs on language learning.

Although previous research has well documented the successful use of LCs in ESL and EFL classrooms at primary, secondary, and tertiary school levels, it should be noted that extremely few scholars and teacher researchers have investigated the use of LCs in a technological university (TU), a new type of school offering both 4-year BA/BS degree and 2-year associate degrees in various disciplines in Taiwan. Recently, the number of students enrolled in this new type of school has increased dramatically. How Taiwanese non-English majors enrolled in a TU engage in LCs has remained largely underexplored. The goal of this article is to provide an overview of how an EFL instructor at a TU in Taiwan successfully integrated LCs into a sophomore English class, a required course for all second-year, non-English majors enrolled in the particular TU.

Implementing Literature Circles at a Technological

University in Taiwan

According to Furr (2007), LCs “are based on the ability of our students, not only to read but also to discuss the texts in English, so the materials must be manageable” (p. 16). Therefore, it is important for the instructor to choose texts at an appropriate reading level for EFL students. Furthermore, if different groups read the same text, it will be 1) much easier for the instructor to monitor the progress of each discussion group, and 2) more possible for the instructor to assign different group projects or extension activities to further deepen students’ comprehension of reading texts.

This paper is concerned with the implementation of LCs in an EFL classroom especially when a course instructor used a textbook that was assigned for the

curriculum. Thus, some changes are made in order to better integrate LCs into a language classroom and to better benefit EFL learners. Following Furr’s (2004a, 2007) suggestions, course instructors, rather than the students, should choose reading texts (that is, selected units or chapters of the required textbook), and students form their groups according to their preferences.

Pilot Study

Context and Participants. LCs were first applied in a sophomore English course at a large technological university in northern Taiwan in Fall 2016. This class consisted of 27 Taiwanese students (aged between 19 and 20 years) at an English language level of CEF B1/B2 (equivalent to IELTS 4-6.5) (Exam English, 2014). Their majors included Industrial Design (n = 6), Interaction Design (n = 8), Cultural Vocation Development (n = 4), and Architecture (n = 9).

This sophomore English course was a semester-long course including 50 minutes of class on Wednesday and 100 minutes of class on Thursday every week for 18 weeks. This course was designed to provide pre-service Design major students with the adequate skills of the English language to facilitate their current academic and future career pursuits. Moreover, students were encouraged to utilize their domain expertise to participate in professional communication in English. The required textbook for this course was Huang and Phelp’s (2014) book, English for Cultural and Creative Industries, which includes 12 theme-based units, with each unit divided into five sections—warm-up activities, main article, dialogue, cultural notes, and exercises.

Many students, especially non-English majors, at this technological university take English courses mainly because they would like to fulfill the requirement for graduation, not because these students are interested in learning English. This also applies to students registering for this sophomore English course as they are usually found to play with their smartphones or work on assignments for other courses in class. In addition, a lot of the students in this sophomore English course expected the

instructor to lecture during the entire class session. In order to instill students’ motivation to learn English and enhance their comprehension of reading texts, LCs were incorporated as part of regular classroom activities.

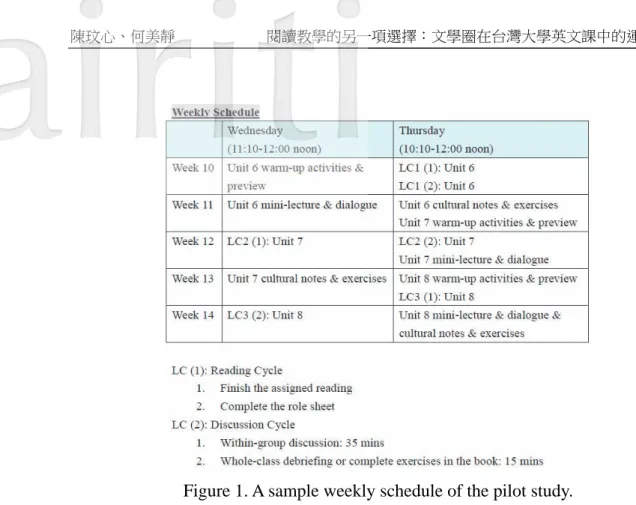

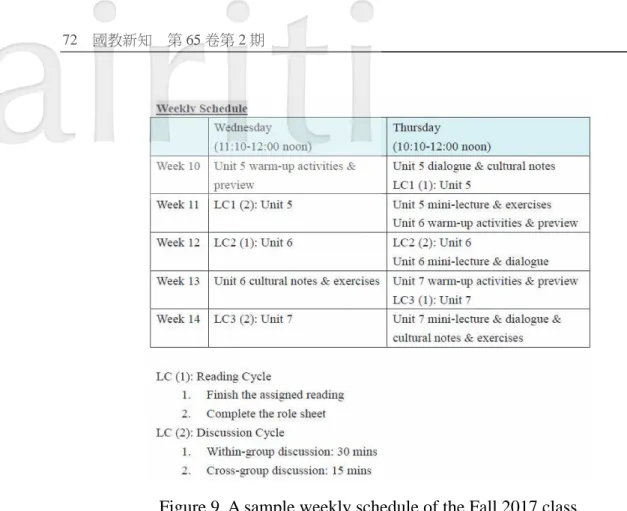

Procedure. During the first half of the semester (week 1 to week 9), students followed the regular syllabus of the class and became familiar with each other, the instructor, and course policies and requirements. From week 10 to week 14, students participated in three rounds of LCs, with each round focusing on different book units. Students read Unit 6 on “Video Games” in the first round of LCs, Unit 7 on “Music Videos” in the second round, and Unit 8 on “Pop Music” in the third round. For each unit, students were requested to read the main article section, which was about 300-500 words in length. Students would do some warm-up activities and were given a short preview of the unit before they started reading the assigned text. After students finished reading and discussing the text, the instructor gave a mini-lecture related to the reading to the entire class. A sample weekly schedule is given in Figure 1.

As pointed out by Shelton-Strong (2012), to apply LCs in an ESL/EFL context, a number of five to six learners per group is suggested and three or four should be the minimum. In this sophomore English course, the students were grouped into six groups based on their personal preferences and without regard to their reading ability, with three groups of four students and three groups of five students.

Figure 1. A sample weekly schedule of the pilot study.

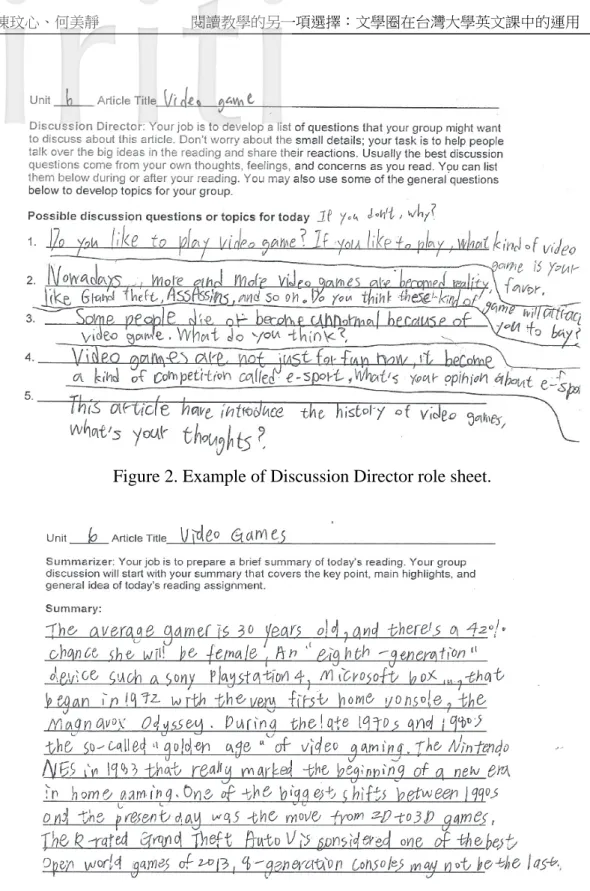

The roles assigned to students were adapted from Daniels’ model of LCs and prompted each individual to read the text from a different viewpoint and to prepare for the group discussion. The roles used in this class were entitled Discussion Director, Summarizer, Connector, Illustrator, and Vocabulary Enricher. The job responsibilities of each role are described as follows.

1. Discussion Director kept the discussion flowing through questions. In this class, Discussion Director was asked to come up with at least four open-ended questions and to call on other group members to share with others their opinions. Moreover, everyone within the group had to answer each of the discussion questions. An example is provided in Figure 2.

2. Summarizer gave a concise but complete summary of the text (as shown in Figure 3). In this class, it was suggested that Summarizer present his or her summary early in the discussion, which helps everyone recall the content of the text.

3. Connector made connections between the text and the real world where he or she lives. For instance, Connector may show the relationships between the text and personal concerns, home life, school life, or other literary works. In this class, Connector was requested to find at least three connections. An example is offered in Figure 4.

4. Illustrator drew or created a picture related to the reading (as demonstrated in Figure 5). In this class, it was suggested that Illustrator do not explain his or her drawing immediately; rather, other group members talked about their speculation about what the picture meant and connected the picture to their own ideas about the reading. Following this, Illustrator shared what he or she thought the picture meant, where it came from, or what it represented to him or her.

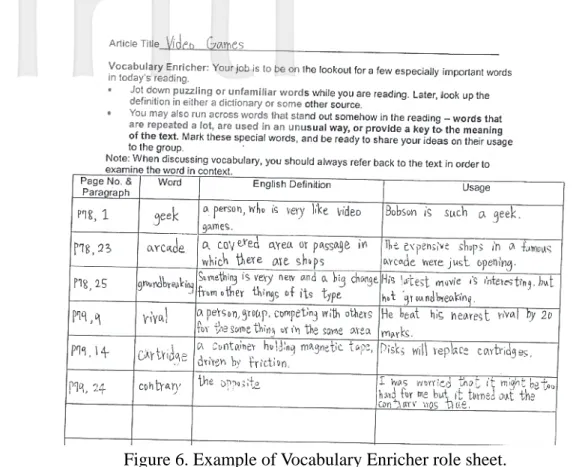

5. Vocabulary Enricher chose at least six words or phrases that he or she thought were important to understand the reading; additionally, for each of these words, Vocabulary Enricher prepared the answers to the following questions: “Where is the word found?,” “What does the word mean?,” and “How to use the word in a sentence?” An example is provided in Figure 6.

The role sheets helped students enact their roles during reading and discussion cycles. Students completed the role sheets during and after the reading. The roles were rotated for each new reading cycle. By so doing, students had a chance to play different roles, giving them a different focus for reading and discussing a given text.

Each round of LCs consisted of one reading and one discussion cycles. The reading cycle took one class period (50 minutes), during which students formed their groups, decided who would take on which role, and then completed the assigned reading independently. In the discussion cycle, which took another class period (50 minutes), the students met in their groups in class and participated in a within-group discussion, directed by the roles they had selected and prepared, for about 35 minutes. Following the within-group discussion, the students had whole class debriefing or completed the exercises in the book.

Figure 2. Example of Discussion Director role sheet.

Figure 4. Example of Connector role sheet.

Figure 6. Example of Vocabulary Enricher role sheet.

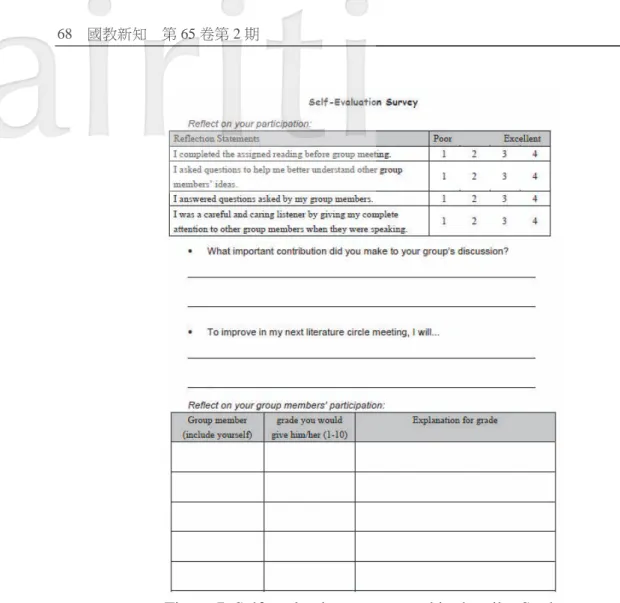

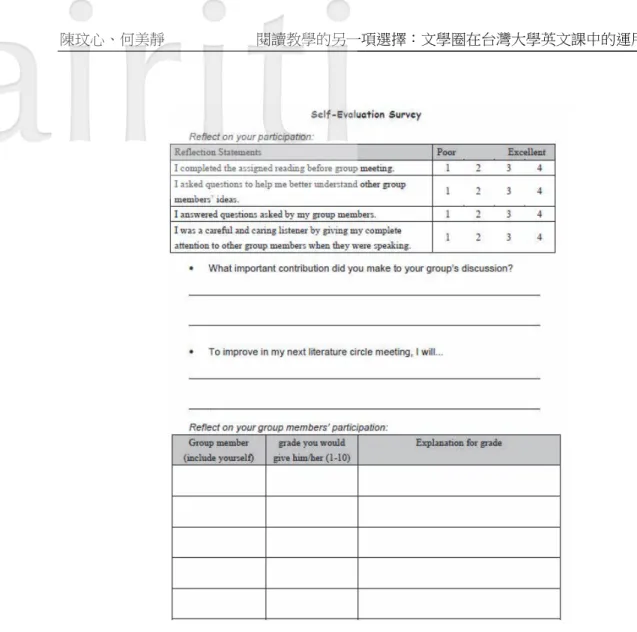

Once each discussion cycle was concluded, the students filled out a self-evaluation survey (as shown in Figure 7); it required the students to rate their abilities as discussants, to evaluate the level of participation of each member during group discussion, and to write about what important contributions they made to the group discussion and how to improve their performance in the next LC meeting. When each book unit was finished, new groups were formed, based on student choice, and new roles were allocated for the next round of LCs.

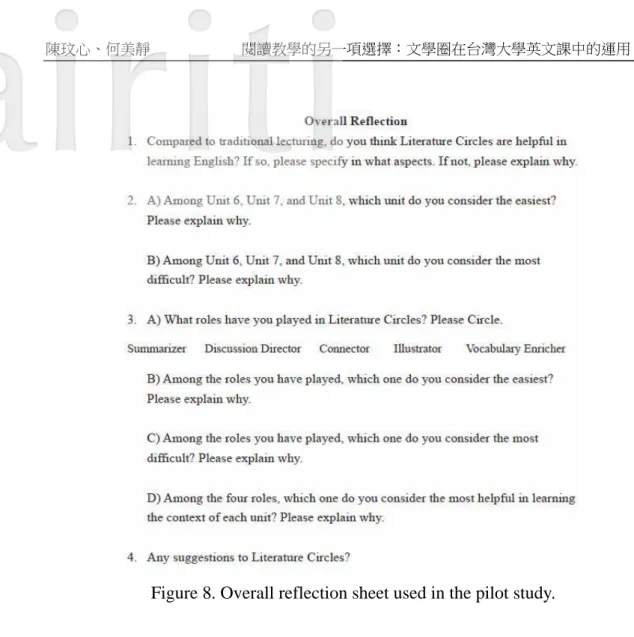

After the three rounds of LCs, the students completed an overall reflection sheet about their opinions on LCs, what they enjoyed and what they found difficult in terms of the units and the roles during their LC experience (as presented in Figure 8). Their feedback, combined with the instructor’s personal observations, was used to make decisions about the structural changes to future implementation of LCs in an EFL classroom.

Figure 8. Overall reflection sheet used in the pilot study.

According to the feedback obtained from the overall reflection sheets filled out by the students in the Fall 2016 class as well as the instructor’s personal observations, some students indicated that Unit 8, “Pop Music,” was the most difficult because it contained many unknown words or phrases; in addition, this unit introduced western pop music only and some of the students were more familiar with Asian pop music. Therefore, it was decided to remove Unit 8 and select Unit 5, “Game Apps,” in the formal implementation of LCs.

With respect to the roles, some students remarked that Vocabulary Enricher was the easiest as well as a less interesting one to enact. They further mentioned that they could fulfill the duties as a Vocabulary Enricher without reading the full text or understanding the content. In view of this, it was decided to take out the role of

Vocabulary Enricher in the formal implementation of LCs.

Several of the students were found to be slower in completing the role sheet, especially when the text was longer in length or contained some unfamiliar words, and they needed more than one class period to complete their work. This observation led to the decision that the reading and discussion cycles should always take place on two different days in the future implementation of LCs and this was also suggested by the students.

Some of the students commented that they liked LCs, and it would be more fun if they could interact with members of other groups by sharing interesting or thought-provoking discussion questions their original group discussed. Thus, in the formal implementation of LCs, students were given time to share their thoughts with members of other groups.

With reference to the self-evaluation survey, it was observed that when rating their abilities as discussants on a 4-point scale (1= poor, 4= excellent), many students tended to select 3 and some reported that they cannot understand how rating their abilities as discussants contributed to their English learning. They suggested this part be removed. In addition, a lot of the students considered the responsibilities of their roles the most important contribution they made to the group discussion (e.g., “connecting the article with our life experience” a sample response by a Connector; “asking questions to help others understand the article” a sample response by a Discussion Director). Furthermore, when being asked about how to improve their performance in the next LC meeting, many of the students simply answered “I will read the article several times” or “I will write more/ draw well/ ask more questions/ explain words clearly next time.” Therefore, the self-evaluation survey went through major revisions by adding the section concerning the cross-group discussion and deleting the parts of rating one’s abilities as discussants, commenting on the important contribution one made to the group discussion, and suggesting ways to improve one’s performance in the next meeting.

Formal Implementation

Context and Participants. The revised LC activities were implemented to 36 Taiwanese students taking the same course with the same instructor at the same school in Fall 2017. These students were similar in terms of language background and English proficiency to the students in the Fall 2016 class (see previous section). The majors of these students consisted of Industrial Design (n = 13), Interaction Design (n = 14), and Architecture (n = 9). The students in the 2017 class were divided into nine groups according to their personal preferences.

Procedure. Three rounds of LCs were conducted from week 10 to week 14. Students completed in order the reading of Unit 5 on “Game Apps,” Unit 6 on “Video Games,” and Unit 7 on “Music Videos.” A sample weekly schedule is given in Figure 9.

The roles used in the Fall 2017 class included Discussion Director, Summarizer, Connector, and Illustrator. The descriptions of these four roles were the same as those described in the Fall 2016 class.

Each round of LCs was made up of one reading and one discussion cycles, with each cycle lasting about one class period. In the discussion cycle, unlike the one described in the Fall 2016 class, the students first engaged in a within-group discussion for about 30 minutes, and the remainder of class time was spent on the so-called cross-group discussion, in which two members of one group regrouped with two members of another group. In the cross-group discussion, members of two different groups shared with each other one of the discussion questions discussed in their original group and their own answers to the question. In addition, they were required to talk about their answers to the discussion question another group shared.

Figure 9. A sample weekly schedule of the Fall 2017 class.

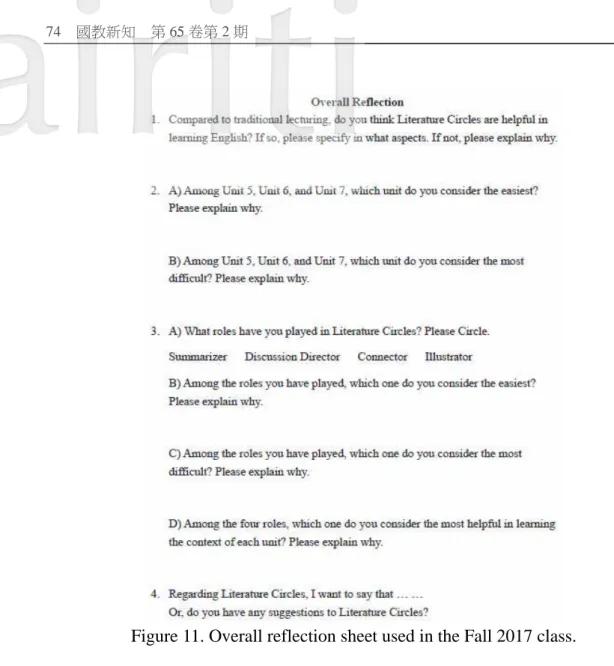

After concluding each discussion cycle, students were requested to complete a self-evaluation survey (as shown in Figure 10). The survey asked students to assess the level of participation of each member in discussion groups and to write down the discussion questions and their corresponding answers being shared during the cross-group discussion. Once the three rounds of LCs were completed, students filled out an overall reflection sheet similar to the one used in the Fall 2016 class (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Overall reflection sheet used in the Fall 2017 class.

Findings

LCs were effective teaching strategies that could foster active learning, based on the instructor’s personal observations. For instance, in Unit 5, “Game Apps,” one discussion topic a Discussion Director came up with was the question “What will be the next page of game apps?” and it sparked energetic discussions among students. They talked about Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Mixed Reality (MR), their definitions, and the differences between them. Although AR, VR and MR are not introduced in this textbook, students were able to rely on their real

world knowledge and online research to discuss and share their viewpoints with their peers. Take Unit 7, “Music Videos,” for another example. This unit mentions several music videos of different times. In order to comprehend the assigned text and complete her role sheet, one student watched every music video introduced in the textbook online. She found that in the music video “Video Killed the Radio Star,” released in 1979 by the Buggles, the reflection of the moonlight on the waves was produced by two staff members shaking plastic bags (TheBugglesVEVO, 2010). This student shared this finding with her peers and they all felt so amazed. They further discussed how shooting techniques have changed since 1980s and how technology has influenced the making of music videos. Compared to traditional lecturing, in which students passively receive information given by the instructors, LCs encouraged students’ active involvement in the learning process.

In addition to promoting active learning, LCs were found to cultivate critical thinking skills among the Taiwanese non-English majors enrolled in the technological university examined in this paper. For example, in Unit 6, “Video Games,” students discussed such questions as “The eighth generation of video game consoles is predicted to face competition from smartphones, tablets, and smart TVs. Do you agree or disagree? Why?” or “The author says that playing video games was seen as a hobby for lonely teenage boys in the past, but nowadays 42% of gamers are female. Why are there more female gamers nowadays?” For the second question, students talked about gender discrimination, gender equality, feminism, and how the status of women has changed over the years in Taiwan and in other countries. In Unit 7, “Music Videos,” for another example, the following questions were asked during the discussion cycles: “Why does the author say, ‘Did YouTube kill MTV?’” or “Why are sexually explicit dance moves the norm in music videos nowadays? Do you think this is a good thing or bad thing?” When doing LCs, students did not simply answer factual questions; they had to analyze, evaluate or reflect on the information presented in the assigned readings to solve problems or make decisions, all of which enhance critical thinking.

Students’ Views and Experiences with Literature Circles

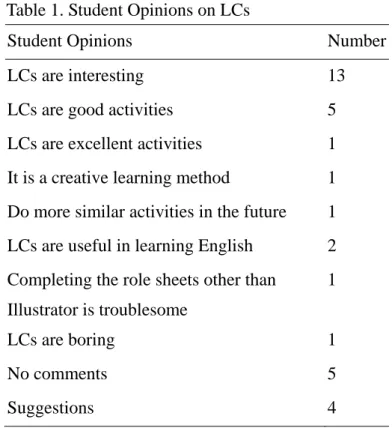

In the Fall 2017 class, the overall reflection sheet, in which students provided open-ended comments, ran after the three rounds of LCs and had a response rate of 92% corresponding to 34 students. Of the students who responded to the question of their opinions on LCs or any suggestions to LCs, 23 were positive about many of the LC activities, five left no comments, and two held negative attitudes towards the implementation of LCs in their class. The remaining four students made some suggestions, such as reading articles other than those on the textbook, having four rounds of LCs, integrating group competitions into LCs, and allowing more time for group discussions. Sample student opinions on LCs are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Student Opinions on LCs

Student Opinions Number

LCs are interesting 13

LCs are good activities 5

LCs are excellent activities 1 It is a creative learning method 1 Do more similar activities in the future 1 LCs are useful in learning English 2 Completing the role sheets other than

Illustrator is troublesome

1

LCs are boring 1

No comments 5

Students were also asked to comment on whether LCs are helpful in terms of English learning. Thirty-three of them agreed that they have benefited from LCs. Specifically, LCs helped enhance their comprehension of the reading texts (n = 13), develop thinking skills (n = 8), and sharpen the listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills (n = 2, 18, 3, 4, respectively). The remaining one student stated that all roles other than Illustrator helped improve his writing and communication skills. Some comments about LCs included:

1. Literature circles helped me learn English. Literature circle discussions made me try my best to express myself in English, and as a result, I noticed what I did not know. (Female)

2. Compared to my previous English classes, literature circles were more fun. Through group discussions, literature circles helped increase my understanding of what I read. (Female)

3. Literature circles made English classes less boring. They improved my speaking skills and made me think deeply about the article. (Male)

4. Literature circles were helpful. I made some progress in terms of my reading skills and my vocabulary knowledge. Reading the texts by myself and before lectures helped me become more familiar with the texts. (Male)

Conclusion

The goal of LCs is to encourage active learning by providing students with opportunities for focused reading and collaborative discussions. In the case of the EFL college students examined in this paper, LC role sheets were found effective in engaging students in different types of tasks, providing them with an opening to discussions at a deeper level than those offered by the so-called “discussion-based” textbooks which are commonly used in EFL classrooms. Moreover, LCs motivated students to read the reading materials critically, to share with each other their feelings, opinions, and responses to the reading materials, and to ask questions of one

another in a way that is not always possible for students in traditional language classrooms.

The use of LCs in EFL contexts seems to be viable and fit well with established teaching practices. Additionally, LCs promote student-centered, collaborative learning, and are largely compatible with what is usually considered a pedagogically sound approach to stimulating second language acquisition.

REFERENCES

Anderson, A. R. (2012). Implementing literature circles: An experimental study in an English language learners’ classroom. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Capella University, Minneapolis, MN.

Bains, J. (2014). The reading attitudes and motivation of adolescents participating in literature circles. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Saint Mary's College of California, Moraga, CA.

Bedel, O. (2016). Collaborative learning through literature circles in EFL. European Journal of Language and Literature, 6(1), 96-99.

Bell, J. (2003). Chapter 1: Critical thinking: Teaching college and university students to think critically and evaluate. Retrieved from http://www.curriculumproject. com/pdfs/Critical_Thinking_Resources-Curry%202013.pdf

Bowers-Campbell, J. (2011). Take it out of class: Exploring virtual literature circles. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(8), 557-567.

Calzada, S. M. (2013). Reading as a means of promoting social interaction: An analysis of the use of literature circles in EFL teaching. Encuentro: Revista De Investigación e Innovación En La Clase De Idiomas, 22, 84-97.

Cameron, S., Murray, M., Hull, K., & Cameron, J. (2012). Engaging fluent readers using literature circles. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years, 20(1), i-vii. Chen, W. L. (2013). An action research on enhancing junior high school students’

(Unpublished Master’s thesis). National Kaohsiung Normal University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Daniels, H. (1994). Literature circles: Voice and choice in book clubs and reading groups. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Daniels, H. (2002). Literature circles: Voice and choice in book clubs and reading groups. (2nd ed.). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Day, R. (2003). Teaching critical thinking and discussion. The Language Teacher, 27(7), 25-27.

Exam English. (2014). Comparisons of CEF levels and scores for the various exams. Retrieved from https://www.examenglish.com/examscomparison.php

Fredricks, L. (2012). The benefits and challenges of culturally responsive EFL critical literature circles. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(6), 494-504.

Furr, M. (2004a). Literature circles for the EFL classroom. Proceedings from the 2003 TESOL Arabia Conference, Dubai. United Arab Emirates: TESOL Arabia. Furr, M. (2004b). Why and how to use EFL literature circles. Retrieved from

http://www.eflliteraturecircles.com/howandwhylit.pdf

Furr, M. (2007). Reading circles: Moving great stories from the periphery of the language classroom to its centre. The Language Teacher, 31(5), 15-18.

Heineke, A. J. (2014). Dialoging about English learners: Preparing teachers through culturally relevant literature circles. Action in Teacher Education, 36(2), 117-140.

Hsu, J. Y. T. (2004). Reading without teachers: Literature circles in an EFL classroom. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED492558

Huang, C.-W. (2009). Effects of virtual literature circles on university students’ reading attitudes and reading comprehension in EFL context. (Unpublished Master’s thesis). Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan.

Huang, M. (2016). A study of implementing literature circle in a senior high EFL classroom. (Unpublished Master’s thesis). National Taiwan University of

Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan.

Huang, S.-J., & Phelps, L. (2014). English for cultural and creative industries. Taipei: Cosmos Culture Ltd.

Ketch, A. (2005). Conversation: The comprehension connection. The Reading Teacher, 59(1), 8-13.

Lenters, K. (2014). Just doing our jobs: A case study of literacy-in-action in a fifth grade literature circle. Language and Literacy, 16(1), 53-70.

Liao, M. H. (2009). Cultivating critical thinking through literature circles in EFL context. SPECTRUM: NCUE Studies in Language, Literature, Translation, (5), 89-115.

Maraccini, B. J. (2013). Teacher perceptions of the use of literature circles and student engagement in reading. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Piedmont College, Demorest, GA.

McDown, D. C. (2012). Novice secondary teachers' experiences supplementing textbooks with trade books in a literature circle format. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX.

Morales, A., & Carroll, K. (2015). Using literature circles in the ESL college classroom: A lesson from Puerto Rico. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 193-206.

Schoonmaker, R. G. (2014). A blended learning approach to reading circles for English language learners. University of Hawai'i Second Language Studies Paper, 33(1), 1-22.

Shelton-Strong, S. (2012). Literature circles in ELT. ELT Journal, 66(2), 214-223. Su, Y. C., & Wu, K. H. (2016). How literature circles support EFL college students’

literary and literacy learning in a children’s and adolescent literature course. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education, 7(3), 2874-2879.

TheBugglesVEVO. (2010, October 8). Video killed the radio star [Video file]. Youtube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/W8r-tXRLazs

Thein, A. H., Guise, M., & Sloan, D. L. (2011). Problematizing literature circles as forums for discussion of multicultural and political texts. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(1), 15-24.

Thomas, D. M. (2013). The effects of literature circles on the reading achievement of college reading students. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN.

Tsai, Y.-H. (2017). Action research on implementing literature circles in teaching English reading at a senior high school. (Unpublished Master’s thesis). National Dong Hwa University, Hualien, Taiwan.

van Keulen, B. J. (2011). Effects of literature circles on comprehension and engagement. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Southwest Minnesota State University, Marshall, MN.

Waring, R., & Takahasi, S. (2000). The why and how of using graded readers. Tokyo: Oxford.

Yamin, B. M. (2015). Literature circles in EFL literature classroom settings. Retrieved from https://www.asjp.cerist.dz/en/downArticle/184/3/7/28926