Study of Backpackers

Shan-Ju L. Chang

Library Trends, Volume 57, Number 4, Spring 2009, pp. 711-728 (Article)

Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press

For additional information about this article

Access Provided by National Taiwan University at 08/17/10 7:05AM GMT http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/lib/summary/v057/57.4.chang.html

Abstract

In the modern, increasingly flat world, many individuals have seen an increase in the amount of leisure time they have available. This leisure time is used for different purposes, often including travel and tourism. Among the many types of travel and tourism, back-pack or budget travelling is becoming more and more popular. This increasingly common leisure activity presumably involves intensive information search activities.

This study places the backpackers’ search for travel information in an everyday life information seeking (ELIS) perspective. The search for information by backpackers can be seen as a three-stage information search process. In each stage, depending on the type of task, backpackers use various information resources for different purposes. Such sources may be used for more than one purpose and in more than one information search stage. However, their relative importance varies depending on the characteristics of the source of information and the information search stage in which the source is being used.

In this article I suggest that studies of leisure information behav-iors and leisure activities show theoretical and practical value for both the information seeking public and the information science community. We also suggest that library and information science scholars and practice communities direct attention and research resources to leisure research in general, and the concept of serious leisure and its structured information acquisition and sharing activi-ties in particular.

an Empirical Study of Backpackers

Shan-Ju L. Chang

LIBRARY TRENDS, Vol. 57, No. 4, Spring 2009 (“Pleasurable Pursuits: Leisure and LIS Re-search,” edited by Crystal Fulton and Ruth Vondracek), pp. 711–728

Introduction

Leisure time and leisure activities increasingly play an important role in modern societies. The importance of leisure information is well acknowl-edged in public library services. One of the major functions of public libraries is to provide information for various social communities in the planning and implementation of safe and interesting leisure activities. In order to achieve this, a deeper understanding of how people acquire or seek out leisure information, and what would constitute a useful interface for finding the information they seek is desirable.

According to a telephone survey conducted in February-March 2007 by PEW (2007), “fully 83 percent of online Americans say they have used the internet to seek information about their hobbies, and 29 percent do so on a typical day. Looking for information about hobbies is among the most popular online activities, on par with shopping, surfing the web for fun, and getting news.”

Advances in technology, changing social structures, and growing global economics have led to increases in the amount of time available for lei-sure activities in modern societies. For many people this growing leilei-sure time allows them to pursue hobbies, with travel and tourism often being a popular choice.

Such hobby travel feeds into the worldwide tourism industry, provid-ing a growprovid-ing source of revenue in the world’s economy. Among the many forms of travel and tourism, backpacking has quickly become a popular option (Cohen, 2003). Younger travelers on a limited budget often choose backpacking over conventional pre-packaged group tours or mass tourism (Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995).

When compared with conventional mass tourism, backpacker tourism is characterized by independent travelers who autonomously pursue travel experiences and often experience and, in fact expect: lower safety during a trip, greater demand on the traveler’s language capability, and higher flexibility in the arrangement of travel plans and itineraries. Furthermore, in contrast to mass tourism, with its often preset budget in terms of food, accommodations, and transportation, backpack travelers usually plan and adjust their travel budget along the way (Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995; Richards and Wilson, 2004).

According to Slaughter (2004), many studies on backpackers show that most of them are budget travelers and are relatively young. The vast ma-jority of such backpack travelers are younger than thirty years of age. In terms of their culture, low-cost travel options are popular, such as youth hostels and budget flights. Public transport is usually important to back-packers. Richards and Wilson (2004) point out that backpackers also tend to have an emphasis on relatively long travel durations and social con-tact with fellow travelers. Cohen (2003) further suggests that, for many backpackers, the main purpose or allure is to have “hedonistic enjoyment,

experimentation and self-fulfillment under relatively simple (and afford-able) circumstances.”

In order to address the kinds of issues a backpacker might need to deal with and to make the best out of the trip, backpack travel presumably in-volves intensive information search activities. However, though backpack-ers presumably have certain information tasks to accomplish, leading to a number of questions of interest for information studies, little information research has been done to explore relationships between information, information behaviors, and leisure activities.

Although literature on information seeking and use is abundant in li-brary and information science, most user studies have focused on scholars, researchers, or professionals and their unique information needs within their specialized work contexts (Wilson, 1999). Most studies of informa-tion seeking are problem oriented, and were conducted in academic or work environments rather than recreational settings (McKechnie et al., 2002). Relatively few studies specifically investigate how and why people who travel as a leisure activity conduct information searches.

In this study, we pose the following questions in order to explore the information search behaviors of backpack and budget travelers within the context of everyday life information seeking, with particular reference to leisure activity search behaviors:

• What do people do when they plan to travel as a backpacker? What, if any, tasks are involved?

• What kinds of information do backpackers need, and what kinds of information do they seek?

• How do backpackers search for or collect information throughout the course of their travels?

• How do backpackers make use of information they collect throughout the course of their travels?

• What factors are influential in determining backpackers’ information needs and search behaviors?

This article summarizes an empirical study undertaken to explore the above questions. More specifically, we explore how backpackers go about collecting and searching for the information they need to make travel plans and/or to make their travel experiences worthwhile. We review re-lated work, present the results of our empirical study, and follow with a discussion that explores implications drawn from this study and their ap-plicability to library and information services. Suggestions for possible fu-ture research conclude the paper.

Related Work

Information Research in Tourism

Current studies in the literature on travelers and tourists tend to be con-ducted from psychological (Clawson, 1963; McIntosh and Goldner, 1990) or sociological perspectives (e.g., Wang, 2000; Murphy, 2001). Such stud-ies usually focus on general topics and questions, such as what types of tourists are to be found (e.g., Uriely, Yonay, & Simchai, 2002), and what it is that drives people to travel (Thomas, 1964; McIntosh, 1990; Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995). Thomas, for example, showed that there are eighteen types of travelers motivated by four types of motivators for travel: educational/cultural, relaxing and recreational, ethnic traditions, and other motivators, such as to be fashionable or adventurous (Thomas, 1964). More recently, members of the Association of Tourism and Leisure Education (ATLAS) Backpacker Research Group (BRG) conducted a re-search program attempting to answer questions such as why do people become backpackers, what do they experience on their travels, how has the backpacking experience changed over time, and what impact does backpacking have on later life (Richards and Wilson, 2004).

In addition, various types of surveys are often carried out to answer questions about and to design strategies for the marketing and develop-ment of tourism (Fodness and Murray, 1997). Fodness and Murray (1997) described the relationship between information provision and traveling decision making in order to devise better marketing strategies. They clas-sified the source of tourist information according to two dimensions: com-mercial vs. noncomcom-mercial, and personal (face-to-face) vs. nonpersonal (publications). Such research was often drawn from the marketers’ per-spective, rather than that of backpackers. In fact, as Cohen (2003) points out, although backpacking is a rapidly expanding phenomenon, it is a relatively little studied form of tourism.

Although information seeking and use by backpackers is not well re-searched, information seeking studies in general have long been a promi-nent subject in library information science. Thus the body of literature on information seeking, needs, and use is quite extensive (see Case, 2002 for a more comprehensive review). For this study, only research in the lit-erature that is most relevant to leisure pursuit will be discussed here. With a few exceptions, information research related to leisure activities is still relatively new in library and information science.

Information Seeking

Kuhlthau’s seminal work proposed a process view of information seeking (Kuhlthau, 1991). In Kuhlthau’s information search process (ISP) model, six distinguishable stages of the search process were identified, each with distinctive needs for information and associated channels for acquiring

information, leading toward the completion of an educational task like writing a term paper. Kuhlthau contends that as one moves through each stage, the information seeking behaviors and associated information uses are changed accordingly. However, the process model has not been applied to information seeking studies outside of educational environments.

In such information seeking research, increasingly more attention is being paid to everyday life information seeking (ELIS) behaviors (Case, 2002). Among the scholars who are interested in information seeking in nonwork environments, Savolainen’s work on information seeking in the context of way of life is most relevant here (Savolainen and Kari, 1995; Savolainen, 2005). Savolainen proposed a model of ELIS, suggesting that personal interests and hobbies as a way of life involves information seeking and use in everyday life. The material, social, and cultural capital owned by the individual all have bearings on the seeking and use of information. The individual would have preferences regarding information sources and channels that are guided by habitus, a socially and culturally deter-mined system of thinking, perception, and evaluation that is internalized by an individual and used for making choices in life. Backpacking, in this case, is considered as a hobby. Backpackers might thus demonstrate their personal preferences in terms of the media used in seeking information relevant to their interests in the context of everyday life.

Recently, some research has been done investigating information be-haviors in leisure activities. For example, Ross (1999) shows that people do not seek, but rather find information for pleasurable reading. Chang and Liu (2001) explored both the book finding strategies used by participants of an online community in the context of reading for pleasure and the influential factors for choosing specific strategies. They found that sources and strategies used to find materials for pleasurable reading were, in many ways, different from those reported in library user studies. Their results show that information sharing and social interaction among members of an online community is an important strategy for finding information on pleasurable readings. In a study related to information behaviors in a daily life context, Fulton (2005) emphasizes the role of social networks as an important source for genealogical information. In our study we look at the backpackers’ search for information in a daily life context.

Information Need and Use

In this line of research, the motivations and needs that drive information searches are the major concerns. In order to understand the need for information or the causes for information seeking in terms of the prob-lems, tasks, and situations one might encounter, the concept of task, and any specific problems a task might be associated with, becomes important (Bystrom and Hansen, 2005; Vakkari, 2003; Wildemuth and Hughes, 2005).

Vakkari (2003) discusses the notion of task and its importance in under-standing information search behavior. Bystrom and Hansen (2005) assert that there are embedded relationships between work task, information seeking task and information search task in a workplace. Wildemuth and Hughes (2005) suggest that more empirical studies of tasks in information seeking are desirable. However, because the concept of task has been stud-ied mostly in work environments, it is unclear how applicable the concept of task is in research of leisure activities. A deeper understanding of task and problem solving in leisure activities, such as backpacking, is called for. Serious Leisure Research

Among the sociological approaches to studying leisure, Robert Stebbins’ work is most relevant here. Stebbins (1982, 2001) classified leisure into two types—casual and serious, and proposed the concept of “Serious Lei-sure,” defined as the systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist, or volun-teer of a core activity that is found to be so substantial, interesting, and ful-filling that participants spend a large proportion of their time and efforts acquiring and expressing the special skills, knowledge, and experience unique to that activity (emphasis added). This conceptualization affirms the roles that information and the acquisition of information play in enabling such leisure experiences. Stebbins described three broad categories of serious leisure, relating to three types of participants: the amateur, the hobbyist, and the volunteer. Backpacking fits within the hobby category of serious leisure activities, and as hobbyists, backpackers are motivated to acquire and express specialized knowledge and skills—but little is known about how they do so.

In summary, the notions of process, task, problem solving, and the individual’s experience and preferences are all important for exploring backpackers’ information behavior in the context of ELIS.

The Design of an Empirical Study

The experiences and processes backpackers encounter in their informa-tion search activities were the foci of our empirical study. A naturalistic inquiry approach was adopted, and a critical incident technique was ap-plied. Data was collected from semi-structured interviews with thirty sub-jects living in Taiwan whose mother tongue is Mandarin, each of whom had at least one experience backpacking in a foreign country. Partici-pants were selected using snowballing techniques, and also by asking for volunteers from an online forum on backpacking.

The research instruments created for this study were based on ques-tionnaires and interview guides described in the literature on information need and use studies in general, and tourists in particular. In addition, the researcher’s personal experience in backpacking was also drawn upon in the design of the questions for interviews.

A brief questionnaire was used to collect the participant’s demographic and background data, consisting of sixteen items in two categories, includ-ing demographic information (gender, age, education, occupation, an-nual budget for international travel, etc.) and backpacking experience (such as frequency and type of previous travel; general travel experience before traveling as a backpacker; and first experience as a backpacking traveler including age of first experience, destination, duration of travel, and number of accompanying travelers).

The interviews consisted of two parts. Each participant was first asked to describe their most recent and memorable experience with backpack-ing. Various questions were then asked, such as: How did the participant prepare for traveling as a backpacker? What information did the partici-pant search for, how did they search for that information, and why did they choose to search for that information? What problems or difficult situations did the participant encounter during their trip? What could the participant have done, in hindsight, to avoid those problems or difficult situations? How did the participant use the information they searched for and collected throughout the course of their trip?

Another part of the interview explored the participant’s use of travel websites. Participants were asked to characterize the most useful or mem-orable backpacker-specific website that he/she had encountered (if the participant did not have such experience, he/she was asked to explore a well-known local travel website prior to taking part in the interview).

Interviews were conducted in person and lasted for an hour on aver-age. Interview data was then transcribed and analyzed according to the themes relevant to the research questions.

Description of Participants

Of the thirty participants interviewed, two-thirds were selected using snowballing techniques, and the remaining one-third was selected from the online forum. The participant’s age ranged from 20 to 39, with an average of 26.7 years old. The male/female gender ratio was 3 to 2. Most participants were students, accounting for 36.7 percent of the intervie-wees. Also included were journalists, banking staff, teachers, engineers, information service professionals, Web administrators, and art editors.

Out of the thirty participants, seven had one distinct backpack travel experience (or one trip as a backpacker), eleven had two to four experi-ences, and twelve had more than five trips involving experience as a back-pack traveler. In the last group, four out of the twelve have traveled as a backpacker at least eight times.

The destinations mentioned by the interviewees included cities such as New York, Tokyo, Shanghai, or larger areas such as Southwestern or Northwestern China, and whole countries such as Japan, Mainland China, Canada, Nepal, Egypt, Israel, England, France, Italy, Australia, Spain, the

Netherlands, Czech Republic, Northern European countries, and Guam, etc. Asian countries were mentioned more often than others, and Japan was the most popular single destination, followed by the United States.

Findings of the Study

Information Seeking by Backpack Travelers Is Process Oriented with Three Distinct Stages

Travelers seek and collect information in order to make travel plans be-fore they travel. However, there is an assumption that information ac-tivities stop once a trip has begun. Our study found that information is searched for and acquired throughout three stages of a backpack travel-ing trip: before travel, durtravel-ing travel, and after travel.

Before travel, information is needed and used for planning. During travel, it is used for confirming information acquired before travel, pro-viding more details, updating information, and acquiring information that was not available before the trip began. Thus, information seeking does not only take place before travel during planning stages, but also takes place throughout the backpacking journey.

Backpackers Search Information for Making Plans, Solving Problems, Satisfying Curiosity, and Sharing Knowledge

For backpackers, the role of information in leisure pursuits like backpack-ing is important. Specifically, before travelbackpack-ing abroad, backpackers search for information during the planning stages of a trip, which results in the construction of an itinerary. Once the decision to undertake a backpack travelling style trip is made, backpackers begin to plan their trip itinerary.

Three different strategies, reflecting different priorities, for planning a backpacking trip were used by the participants. The most common strat-egy, noted by seven interviewees, was to decide on the destination (sight-seeing places) first. Two interviewees stated that choice of transportation method was their first priority. Two other interviewees prioritized activity choice as their first concern. One interviewee remarked that both the desired destinations and preferred method of transportation must be si-multaneously considered in order to avoid conflicts.

Planning a trip involves a process in which travel ideas and trip events and decisions, such as the selection of sightseeing sites, arrangement of transportation and routes to follow, and the length of time for staying in a chosen place, are arranged in a scheduled sequence. During this plan-ning stage, information about the natural landscape, cultural landscape, and special local activities of the destination tend to take priority in infor-mation searches.

During their travels, backpackers search for information that will help them overcome problematic situations that might be encountered along the way. As a form of tourism “characterized by independent international

travel with minimum of budget use” (Loker-Murphy and Pearce, 1995), backpacking is adventurous, novelty seeking and full of uncertainty. These characteristics also mean that backpackers are often faced with unex-pected problems during their journey. For example, the development of a health problem, mild or serious, needs to be anticipated. Some partici-pants mentioned getting information and advice from other travelers as to whether one can drink tap water in areas they are visiting. Other unex-pected situations may arise during a trip as well. For example, backpackers often travel to locations specifically in order to take part in cultural events or festivals. Unexpected changes in schedule for such events can create difficulties for backpackers. Running out of cash and needing to find out about accepted forms of payment at the time of buying entrance tickets; or even how to register for local activities and events are other sorts of situ-ations that a backpacker may face. In these situsitu-ations, human networks are an important source for useful information.

After traveling, information is sought to satisfy curiosity and to allow travelers to share their knowledge or experience, often on travel websites. In the former information activity, backpackers might go back and read additional information about the site or look for additional materials (e.g., books on the history of a visited place) in order to clarify puzzles or answer questions that arose during the trip. In the latter situation, backpackers coming back from the trip regularly participated in backpacking-related online forums in order to exchange/share experiences and knowledge with other backpacking enthusiasts.

The Trip Planning Stage Was Made Up of Distinct Information Search Tasks We found that there are distinct tasks that need to be carried out by back-packers in planning their travel. Information search tasks carried out by backpack travelers evoke the concept of task in leisure activities in an ev-eryday life information seeking context. During the planning stage, infor-mation search activities fell into seven distinct task categories, including: • Where to go: Selecting destinations/sightseeing locations

• How to get there: Deciding on transportation methods • When to do what: Arranging schedules/itineraries

• Where to stay: Finding accommodations, such as hostels and/or motels

• What to be aware of: knowing about safety/cultural issues (local ta-boos, safety of the surroundings, etc.)

• What to budget: Controlling expenses, learning about local currency • How to use “extra time”: Allocating down time (e.g., transportation

connections, waiting to check into a room, etc.)

Although these trip planning tasks seem to be generic to all travel plan-ning, the detailed processes and information seeking involved with each

task are often taken care of by a travel agency for tourists who purchase travel packages or join group tours. Backpackers, on the other hand, deal with these tasks on their own, usually without much help from travel agents. Furthermore, depending on how much knowledge and experience back-packers have about the destination countries they are planning to go to, preparation for such a trip may yield different degrees of challenge and thus lead to different degrees of complexity in information seeking.

According to the interview data, there are four factors that influence the needs for information in general, and the search tasks in particular.

Reasons for Choosing Backpacking as the Form of Traveling Fifty percent of the interviewees stated that backpacking as a hobby or habitual behavior is their primary reason to choose backpacking as their form of traveling. They said backpacking has become a routine in their lives. Also, 13 per-cent of the interviewees chose their destinations because of the lack of language barriers. In addition, 10 percent of the interviewees reasoned that backpack traveling is more economic than packaged tours. Another 10 percent responded that backpacking was decided upon based on per-sonal situations, such as having spare time to fill during a business trip. The last 7 percent of interviewees said that they chose backpacking be-cause they had traveling needs that could be met by most pre-packaged tours, like adventuring or exploring further into places they’ve already visited, and understanding local historical or cultural features, etc.

Individual Differences in Backpacking Experience The individual differ-ences in terms of frequency of backpack travel, and degree of acquain-tance with countries visited or choice of destination influence the needs for information. Such differences affect the length of time spent on prep-aration before a trip and the types of information a backpacker needs to collect.

Available Time Four interviewees (13 percent) suggest that informa-tion gathering for backpacking is more like an ongoing activity; they can-not estimate how much time is really needed for preparation. How much time a person is able to devote to information gathering is also an impor-tant factor (e.g., attending an imporimpor-tant examination right before travel may reduce available time).

Personal Motivation or Expectation of Tourism Twenty percent of the in-terviewees suggest that a backpacker’s expectations from each travel ex-perience influences the need for information in terms of the amount of information collected and its complexity (the depth and width of infor-mation needed).

A Variety of Sources Were Used to Search for Different Types of Information at Different Stages for Different Tasks or Purposes

Different sources of information were sought at different stages, for dif-ferent tasks or purposes, to satisfy seekers’ needs. In a given seeking task,

such as finding out where to go or where to stay, backpackers initiate sev-eral search tasks in which specific information and the sources of infor-mation are identified and consulted.

For example, in seeking information as a part of deciding where to go, that is, to select a destination or travel site, information about natural attractions, cultural landscape, and featured local activities of a country or city can be identified as distinct categories of information needed and particularly sought after.

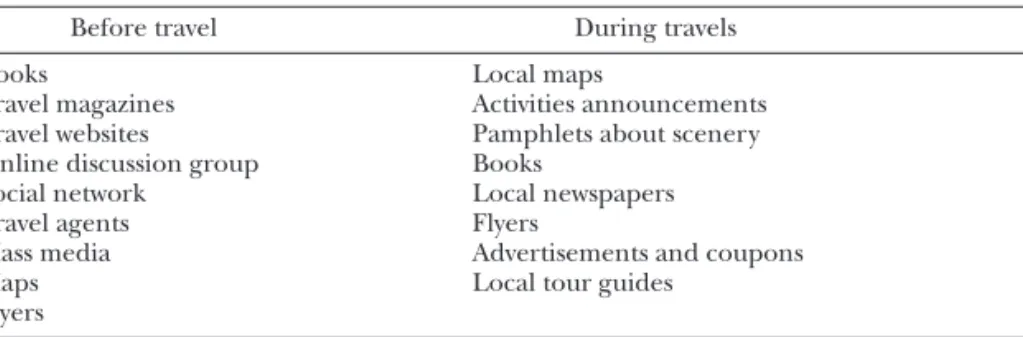

Comparing the types of information sources consulted before and dur-ing a trip, a vast majority of backpackers consulted books and travel maga-zines before traveling, while all interviewees used local maps during their backpack travel (table 1).

Before travel, the top four sources used were books, travel websites, online forums, and social networks. Mass media and maps were consulted to a much lesser degree. During travel, the top four sources reported were local maps, activity announcements, information pamphlets, and books. On the other hand, interviewees reported that online forums on the In-ternet and books were mostly used after travel.

There are not a lot of information sources common to both stages. Most items listed under “Before Travel” tend to draw from fixed or global sources of information (some from the Internet), while during a trip, trav-elers often refer to local information sources, which may change over time and thus have more dynamic features.

Table 1. Type of Information Source Consulted Before and During a Trip

Before travel During travels Books Local maps

Travel magazines Activities announcements Travel websites Pamphlets about scenery Online discussion group Books

Social network Local newspapers Travel agents Flyers

Mass media Advertisements and coupons Maps Local tour guides

Flyers

As shown in table 1, in seeking travel and tourist information, sources that are consulted before, during, and after travel tend to differ. The types of information sources consulted were dependent on the specific charac-teristics of the information sources, and on the information those sources provided. Take book searches for example. The participants reported searching for three types of books, each with a different purpose of use. All participants reported that they use “tour guides,” but explained that

they look for distinct types of tour guides, including books in the trav-eler’s native language, foreign publications from destination countries, and translations of foreign publications. Tour guides are used to select specific destinations to visit. Backpackers also look for “general works on history or social studies” including books about the history, cultural back-ground, and society of a travel area. Some participants also search for “lan-guage books” including textbooks and phrase books in the local lan“lan-guage. Such books are used to practice speaking the language before traveling in order to allow for smoother travel and to show goodwill to the local people.

In terms of the information channels used, backpackers collected proper tour guides by browsing in bookstores (76 percent), obtaining rec-ommendations from related organizations such as backpackers associa-tions or tourism bureaus (17 percent), or from human networks such as friends or online users (17 percent), or libraries (10 percent). Assessment criteria for selecting tour guides are completeness regarding travel sites, whether a tour guide is up-to-date, appropriateness for a particular trip, usability of content (logical arrangement of content, etc.), convenience (easy to carry), and the provision of detailed maps.

While books provide comprehensive contents with selective informa-tion and many pictures or maps, and they are convenient in terms of car-rying while travelling, the information they contain is sometimes not as up-to-date as other information sources. In contrast, travel agents’ web-sites are a preferred source due to their frequent updates and interactive features, as well as the provision of photographs. However, information from such websites tends to be fragmented, and it is more time consuming to find appropriate, practical materials using websites.

A backpacker online community is often turned to for obtaining ba-sic information as well as in-depth commentary on backpack travel. Such online virtual communities are considered precious sources of informa-tion, offering opportunities to learn from other backpackers based on their real experiences interacting with local residents of foreign countries. Some backpackers also look for travel partners using these online com-munity sources of information.

Human networks play an important role as sources of information throughout the whole process of traveling, providing backpackers with information about relevant books, travel magazines, travel websites, travel agents, personal recommendations, etc. Backpackers rely on social net-works, including friends and relatives with real backpacking experience, for personal recommendations before traveling (during the planning stage). During travel, backpackers look for recommendations from tour-ist information centers or other places where backpackers congregate, such as hostels. In these places backpackers often exchange information through conversation. After travel, backpackers often organize their travel

experiences and “publish” on websites or online communities. In addition they may offer personal recommendations to other backpackers through these various social networks.

It is worth noting that traveling to different destinations leads to dif-ferent needs for information. When asked “Are there any differences in seeking information for different destinations to be visited? (e.g., going to different countries)” more than half of the interviewees (56.7 percent) said yes. From the analysis of our interview data, there are five factors that influence the information seeking for tourist information when different destinations are under consideration:

• The amount of tourist information provided in the travelers’ own country

• The traveler’s purpose in backpacking

• Personal previous experience in backpacking in the countries to be visited

• The backpacker’s language abilities

• The degree of development of the tourism industry in the destination countries

Thus the availability of tourist information about different foreign tries varies in relationship to a backpackers’ own country. In the coun-try where the backpackers of this study live, some international places are more readily available and accessible than the others. For example, there is less tourist information about Eastern Europe than there is of the United States or Japan. For very popular places, such as Tokyo, there may even be too much information, which makes it difficult to sort and select what is pertinent. For less popular destinations (like locations in Eastern Europe), there is little information available. In addition, the language in which information is made available on the Web, or whether a back-packer’s language abilities allow him/her to understand the content, puts limits on the usability of the information found.

Multiple Information Channels Were Used Before Travel as Well as During Travel Unlike scholars who prefer to search for information in specific informa-tion channels, such as databases of journal articles, backpackers use many information channels to collect tourist information (for a general review on scholars’ information behavior, see Case, 2002).

A comparison of where and how backpackers acquire traveling infor-mation before and during their travel shows that inforinfor-mation channels used are also specific to the stage of travel (see table 2). Backpackers often visit local institutions or confer with people before travel, whereas during their travel, they are inclined to look for available information anywhere they go and to interact with people, especially in hostels or dining places, to find out about interesting local activities and places to visit.

In comparison of information seeking activities among different stages, information seeking after travel was not as prevalent as informa-tion seeking before and during the course of travel. However, five intervie-wees stated that information seeking does not stop when the trip is over. Post-trip seeking behaviors were manifested in four aspects. A traveler may seek information to answer questions raised during the trip, participate in an online backpacking forum in order to keep updated on the types of stories backpackers typically enjoy, compare his/her perceptions of a place visited to stories in books and magazines, and attempt to learn more about a visited place in which the backpacker developed an interest dur-ing travel.

Note that information gathering in daily life is also part of information activities that backpackers engage in. This ongoing nature of information seeking in leisure pursuit in ELIS is different from job-related informa-tion seeking at workplaces, which tends to focus on a limited number of pre-determined formal sources of information available through formal channels such as libraries or scholarly database providers. These findings also lead to a conceptualization of dynamic information seeking processes in leisure pursuits like backpacking.

Based on the findings, we suggest that information provision for backpacking as a leisure activity can be usefully classified according to the information sources needed, the different stages during which the information is to be used, and/or the different purposes for which the information is to be used.

Information Sharing as a Habitual Activity in Leisure Pursuit

When asked why they chose backpacking as their preferred form of trav-eling, more than 50 percent of the participants answered that backpack-ing is a routine activity in their lives. In many cases, backpackbackpack-ing can be considered as a type of serious leisure activity—people engage in it as a hobby. For some, backpacking is considered a way of life—a habitual be-havior in an ELIS context.

Backpackers acquired and shared information in online communities through the use of travel websites, or through publishing their experience

Table 2. Information Channel Used Before and During Travel

Before Travel During Travel Bookstores Tourist information centers Tourist organizations/institutions Personal contacts

Social network Exhibition halls

Libraries Transportation stations (e.g., airports, train stations) Web links Accommodations (hostels)

Book reviews Local bookstores in the country visited Daily accumulations Dining places

and thoughts of backpack travels in online forums. Some participants in this study make a habit of routinely participating in backpackers’ online forums in order to exchange experiences and information with other backpacking enthusiasts. Some of the participants were either in the pro-cess of writing up what they had experienced while backpacking or had plans to do so, with the goal of publishing their experiences as a way of documenting their lives throughout these unique journeys.

According to our findings, taking part in activities that sustain or en-rich a hobby is to engage in habitual behaviors, which is related to ongo-ing processes of information acquisition and sharongo-ing in a daily life context. One characteristic of such information acquisition is the search for or exchange of relevant experience, or “empirical knowledge,” as opposed to “theoretical knowledge.” Important sources of such information were social networks, which backpackers often contact through online commu-nities or during encounters on their journey.

In summary, this study of backpacking, as a hobby or habitual activity, shows the ongoing nature of information seeking in daily life and sheds light on the nature of information seeking in serious leisure.

Discussion and Implications

The notion of Task in an everyday life information seeking context emerged in this empirical study, as did the concept of Stage in leisure information acquisition.

That the notion of task is important to an understanding of informa-tion seeking and informainforma-tion search in work environments is commonly supported in the literature (Bystrom and Hansen, 2005; Wildemuth and Hughes, 2005). In response to the current debate on how applicable the notion of task is in nonwork environments, we argue that there is a com-patible notion of task in leisure pursuits, such as backpacking, which have clear beginning and ending points, entail seven distinguishable tasks that motivate information seeking, and need to be accomplished using the information found.

It is also worth noting that a process view of information seeking in lei-sure pursuit is also applicable. Our study of backpackers as hobbyists in se-rious leisure, following Kuhlthau’s process model of information seeking, suggests that the backpacker’s search for tourist information is a dynamic process, consisting of three stages characterized by distinctly different in-formation needs, seeking, and use.

This study of backpacking as a hobby or habitual activity also shows the ongoing nature of seeking nonwork-related information in daily life and sheds light on the nature of information seeking in serious leisure. Indeed, some interviewees in our study also suggest that the information-related activities and experiences garnered during a trip continue to have an impact on searching behaviors during later trips. For those who

consider backpacking as a way of life or a habitual leisure activity, informa-tion seeking is an ongoing journey that is to be pursued throughout daily life.

Practically speaking, our study suggests several ideas, based on the backpack traveler’s perspective, which could be used by travel content pro-viders and travel website administrators as they design and organize infor-mation content. First, inforinfor-mation service agencies and libraries should provide information that will help accomplish various information search tasks, and that would help solve typical problems that might be encoun-tered while traveling in general, and backpacking in particular. Second, for travel websites, information can be more effectively structured and or-ganized according to travelers’ search tasks and the typical problems one might encounter while travelling as a backpacker. Third, travel content providers can also provide methods or mechanisms for online interaction to facilitate the sharing of travel experiences or travel information among backpackers.

Our study may also have implications for information services in educa-tional contexts. Many student clubs in schools and colleges are established according to shared hobbies and interests, such as hiking clubs, dancing clubs, reading clubs, etc. Thus, college libraries often provide useful lei-sure information, especially on their websites. Knowledge gained through information research on those leisure activities as demonstrated in our study may be used for the activities the students in these clubs may engage in. For example, during the planning stages of a club hiking activity, mem-bers of a hiking club may seek out information on different geographic environments, changing climates, tools and skills for emergencies, and medical treatments, etc. Based on this kind of understanding, librarians may organize related information according to the tasks discovered in each specific stage of such leisure activities.

Our study suggests that it is important for library and information sci-ence professionals to have a better understanding of how people acquire, seek out, or share information in planning leisure activities and/or sus-taining their hobbies. Furthermore, demand for leisure information can be expected to increase along with a growing knowledge economy and increasing life spans. In an aging society people may have more time to pursue hobbies as lifelong learning, which can be considered as a type of serious leisure activities that involves information seeking and use. This area calls for the attention of the researchers in the LIS field.

For leisure information services and research in the future, some chal-lenging issues our study raises are: Can and should information for lei- sure be classified by depth or other criteria? What is the unique informa-tion phenomenon within? What information is needed in corresponding varying levels of involvement by different groups in a particular hobby or leisure activity? What characteristics of information are there? How do

hobbyists evaluate or judge information that is relevant or useful? These are some challenging issues that could be raised for leisure information research. Questions and answers to such questions may help information professionals in the future as leisure arrangements become increasingly important to global economies, as the population engaged in serious lei-sure activities increases due to life span increases, and as leilei-sure industries continue to become more integrated parts of different societies. In such a social context, the provision of leisure information for library users will be a future trend of library services.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers’ helpful com-ments on the early manuscript of this article.

Note

Part of this paper first appeared in “The concepts of task, search stage and source of informa-tion in leisure activities: A case study of backpackers” by Shan-Ju Chang and Hui-Chieh Su. In: Proceedings of ASIST 2007 Annual Meeting.

References

Bystrom, K., & Hansen P. (2005). Conceptual framework for task in information studies. Journal

of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 56(10), 1050–1061.

Case, D. O. (2002). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and

behavior. New York: Academic Press.

Chang, S-J., & Liu, Y-L. (2001). An investigation into book finding strategies and its influential factors in the context of reading for pleasure: A case study of the virtual community of the online forum on reading at National Taiwan University. Journal of Information,

Communica-tion, and Library Science, 8(2), 23–37.

Clawson, M. (1963). Land and water for recreation: Opportunities, problems, and policies. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Cohen, E. (2003). Backpacking: Diversity and change. Tourism and Cultural Change, 1(2), 95–110.

Fodness, D., & Murray, B. (1997). Tourist information search. Annals of Tourism Research,

24(3), 503–523.

Fulton, C. (2005). Social networks of information seeking and lifelong learning: The case of genealogists exploring their Irish ancestry. ASIS&T 2005 Proceedings of the 68th Annual

Meeting, 42. Sparking Synergies: Bringing Research and Practice Together. October 28–November

2, 2005, Charlotte, NC.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process. Journal of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, 42(5), 631–371.

Loker-Murphy, L., & Pearce, P. L. (1995). Young budget travelers: Backpackers in Australia.

Annuals of Tourism Research, 22(4), 819–843.

McIntosh, R. W., & Goldner, C. R. (1990). Tourism: Principles, practice, philosophies. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

McKechnie, L. E. F., Baker, L., Greenwood, M., & Julien, H. (2002). Research method trends in human information behavior. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 3, 113– 125.

Murphy, L. (2001). Exploring social interactions of backpackers. Annals of Tourism Research,

28, 50–67.

PEW/Internet and American Life Project. (2007, September 19). Internet Activities. Retrieved May 15, 2008, from http://www.pewinternet.org/trends/Internet_Activities_2.15.08 .htm

Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2004). The global nomad: Backpacker travel in theory and practice. Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Ross, C. S. (1999). Finding without seeking: The information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783–799.

Savolainen, R. (2005). Information seeking in everyday life. In K. E. Fisher, S. Erdelez, & L. McKechnie (Eds.) Theories of Information Behavior. Medford, NJ: Published for the Ameri-can Society for Information Science and Technology by Information Today, 2005. Savolainen, R., & Kari, J. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching

informa-tion seeking in the context of “way of life.” Library & Informainforma-tion Science Research, 17(3), 259–294.

Slaughter, L. (2004). Profiling the international backpacker market in Australia. In G. Richards & J. Wilson (Eds.), The global nomad: Backpacker travel in theory and practice (pp.168–179). Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Stebbins, R. A. (1982). Serious leisure: A conceptual statement. Pacific Sociological Review,

25(2), 251–272.

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). New direction in the theory and research of serious leisure. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellon Press.

Thomas, J. A. (1964). What makes people travel. ASTA Travel News, 64–65.

Uriely, N., Yonay, Y., & Simchai, D. (2002). Backpacking experiences: A type and form analysis.

Annuals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 520–538.

Vakkari, P. (2003). Task-based information searching. Annual Review of Information Science and

Technology. 37, 413–464.

Wang, N. (2000). Tourism and modernity: A sociological analysis. Kidlington, Oxford: Elsevier Science.

Weiss, D., & Weiss, P. W. (1990). Travel tips for the 90’s. Merrillville, ID: ICS Books.

Wildemuth, B. M., & Hughes, A. (2005). Perspectives on the tasks in which information behaviors are embedded. In: K. E. Fisher, S. Erdelez, & L. McKechnie (Eds.), Theories of

Information Behavior. Medford, NJ: Published for the American Society for Information

Science and Technology by Information Today, 2005.

Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation,

55, 249–270.

Shan-Ju Chang is a professor in the Department of Library and Information Science at National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. Chang published a seminal work on brows-ing in Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST) in 1993. Chang’s research centers on human information behaviors, including searching and browsing, and users of both physical and digital libraries. She has taught courses on research methods, human information behavior, and marketing of library and information services. Chang’s recent research on leisure activities explores leisure reading and hobby-related information behaviors, examining the information acquiring strategies of online communities of book lovers on leisure reading, and information acquiring behaviors exhibited by backpackers, with a goal to suggest user-oriented system design and information services for everyday life information seeking.