Experimenting Independent Commissions in Taiwan's Civil

Administrative Law System: Perils and Prospects

Jiunn-rong Yeh

Professor of Law, National Taiwan University, jryeh@ntu.edu.tw Abstract:

The idea of an independent commission primarily based upon the American model has been introduced and institutionalized in various legal and political contexts. Whether and to what extent can the institution of independent commissions be

adopted and function smoothly in civil law traditions, however, remains to be examined much more carefully. In Taiwan, the introduction of the first independent commission, National Communication Commission, based upon the American model has invited a great deal of misunderstandings and criticisms from local

administrative officials as well as scholars. For example, administrative appeals have long existed in civil administrative law systems, but should decisions of independent commissions be made appeals to the cabinet? If not, would that unfairly interfere with citizens' right to appeal? Similar problems occur everyday and generate local

suspicious on whether this American institution can be really adopted to civil

administrative law systems. Not to mention the much discussed issue of politicization when the idea of independent commissions being introduced to new democracies or contested political regimes. This paper would use Taiwan as a case study to

demonstrate perils and prospects on the introduction of independent commissions to civil administrative law systems and new democracies. Some experiences of South Korea may also be included for discussion.

Table of Content:

I. Introduction ... 2

II. The Road to National Communication Commission: Taiwan’s First Independent Commission ... 3

A. Creating commissions ... 4

1. Creating commission for representation: the 1940s... 4

2. Creating commissions for foreign voices: the 1950s & 60s ... 5

3. Creating commissions in response to growing social and political demands: since the 1980s ... 7

B. Creating independent commissions ... 7

1. The legal recognition of independent commissions in the government reform package ... 8

2. The establishment of National Communication Commission and controversies ... 9

3. Constitutional court rulings and political response ... 12

III. The Operation of Independent Commission and its Legal and Institutional Predicaments ... 18

A. Independence from the view of constitutional structure ... 18

B. Independence from the view of administrative functions ... 20

C. Independence from the view of administrative procedures ... 21

D. Independence from the view of regulatory policies and budget ... 23

E. Independence from the view of the relationship with bureaucracy ... 25

F. Independence from the view of state-society relationship ... 26

IV. Theories in Explaining the Establishment of Independent Commissions ... 26

A. Control, trust and insurance ... 27

B. Analyzing Taiwan’s social context for independent commission establishment………... 29

V. Capacity-building for the “Independence” of Independent Commissions ... 31

A. Analyzing independence: of plural representation, neutrality, and independence………... 31

B. Institutional capacity-building towards meaningful independence ... 33

VI. Conclusion ... 33

I. Introduction

In responding to digital convergence and global competitiveness, Taiwan’s DDP Administration reorganized scattered regulatory authorities and set up the National Communication Commission (NCC) in 2005, the first ministerial level independent regulatory commission in Taiwan. Not surprisingly, this establishment triggered rounds of serious political confrontations, partisan fights and constitutional court rulings against the backdrops of contentious polity in a new democracy.

The idea of an independent commission primarily based upon the model of American independent commission has been introduced and institutionalized in various legal and political contexts.1 Whether and to what extent can the institution of independent commissions be adopted and function in different socio-political context, however, remains to be examined. This paper uses Taiwan as a case study to

demonstrate perils and prospects on the introduction of independent commissions to civil administrative law systems and new democracies. It first looks into the larger historical and political context by identifying stages of development in creating commissions, followed by institutional and functional analysis of “independence” associated with independent commissions. This paper concludes that while there are merits in building up independence in some of the regulatory functions the operation of which is strong linked to the embedded social context, constitutional structure and legal tradition. In a world of increasing regional integration and global governance, some level of relativity in dealing with independent commissions is called for.

II. The Road to National Communication Commission: Taiwan’s

First Independent Commission

In Taiwan, quite a number of government agencies are called as commissions but very few of them are independent. These commissions were created at different times for various reasons, none of which was about independence. Rather, they were created for representation, foreign intervention, political strategy and even expediency. In the following, I shall first briefly discuss how these commissions were created and what functions they shouldered, and next explain why the idea of creating a real

1

For the evolution of independent commissions in the United States, see e.g. Marshall J. Breger & Gary J. Edles, Established by Practice: the Theory and Operation of Independent Federal Agencies, 52 ADMIN.L.REV. 1111 (2000)

independent commission came in after democratization with its surrounding controversies.

A. Creating commissions

The Constitution2 leaves open the organization of the Executive Yuan,

functioning as a cabinet and delegates it to be determined by law.3 The Organic Act of the Executive Yuan, however, fixes it with eight ministries, two commissions and five to seven ministers without portfolio.4 The last revision to this act was in 1980. In the last two decades, many new ministerial positions and government agencies were created by respective organic statutes, and despite several attempts at revising this act, the agenda on government reforms was not put on the table until the first regime change in 2000.

1. Creating commission for representation: the 1940s

The Organic Act of the Executive Yuan stipulates two commissions besides eight ministries: the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission (MTAC) and the Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission (OCAC).5 The creation of these two

2

The Republic of China Constitution (hereinafter, ROC Constitution or Constitution) was created in 1947 and brought by the Nationalist (Kuomintang, KMT) government to Taiwan in 1949 with its defeat and retreat. For further details on Taiwan’s constitutional change, see Jiunn-rong Yeh,

Constitutional Reform and Democratization in Taiwan: 1945-2000, in TAIWAN’S MODERNIZATION IN

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 47-77 (Peter Chow ed, 2002).

3

See Art. 61 of the Constitution. The text of ROC Constitution and its Additional Articles are

available

at http://www.president.gov.tw/en/prog/news_release/document_content.php?id=1105498684&pre_id =1105498701&g_category_number=409&category_number_2=373&layer=on&sub_category=455 (last visited Apr. 10, 2009)

4

There are also two ministerial offices, the Government Information Office and the

Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting & Statistics. See Art 3, 4, 5 of the Organic Law of the Executive Yuan.

5

For the English website of MTAC, see http://www.mtac.gov.tw/pages.php?lang=5 (last visited Apr. 8, 2009). For the English website of OCAC, see http://www.ocac.gov.tw/english/index.asp (last visited Apr. 8, 2009).

commissions represented the KMT government’s attempt at representing “the entire China” despite a persistent gap between what it could rule and what it imagined to rule.6

The history of the MTAC may be traced somehow to Qing dynasty.7 Its current existence, however, could be understood only in the context of representation

reinforcing. In 1912, the newly born Republic of China established an agency

regarding Mongolian and Tibetan affairs within the Ministry of Internal Affairs. After its relocation to Taiwan, the KMT government elevated the previous agency to the level of ministry to represent -however nominal- a de jure control over Mongolia and Tibet.

The OCAC is the other side of the same token regarding this representational myth created by the KMT government. An agency that dealt with overseas Chinese affairs was already established and subordinated to the Executive Yuan in the 1930s. It was later elevated to a ministerial level to bestow the KMT government with an image that it was the government of all Chinese people around the globe despite the fact that it could rule only the tiny island of Taiwan. The organizational form of commission also serves a convenient way to invite overseas leaders of respective countries and regions to serve on the commission.

2. Creating commissions for foreign voices: the 1950s & 60s

6

Jiunn-Rong Yeh, The Cult of Fatung: Representational manipulation and Reconstruction in

Taiwan, in the PEOPLE’S REPRESENTATIVES:ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION 23-27 (Graham Hassall & Cheryl Saunders eds., 1997)

7

Qing dynasty created the Court of Colonial Affairs to oversee the relationship of the Qing court to its Mongolian and Tibetan dependencies. During the years of Emperor Kuang Hsu, it was reorganized as the Ministry of Minority Affairs. It then evolved to the current Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission.

Two very distinctive commissions were established as a way to represent foreign voices in the postwar reconstruction of Taiwan. They were the Council for U.S. Aid (CUSA) and the Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction (JCRR). Today, the former became the Council for Economic Planning and Development (CEPA) while the latter became the Council of Agriculture (COA), and both are still ministerial organs despite largely transformed missions.

The CUSA was established as part of the Sino-American Economic Aid

Agreement signed between the Republic of China and the United States in 1948. The agreement was aimed to create stable economic conditions in Taiwan. American financial aid was provided to Taiwan, and the CUSA was created to supervise their appropriation and utilization. Again, its collegial structure made easier for American advisors to participate decision-making processes. After several times of

reorganization8, it evolved as the current CEPD to promote comprehensive national economic development in 1977.

Similarly, the JCRR was established in 1948 in Nanjing as part of an economic agreement between the United States and the Republic of China. Several members of the Commission were American. It came with the KMT government to Taiwan in 1949. As its missions ended and the agreement terminated in 1979, it was reorganized as the Council for Agricultural Planning and Development (CAPD) and later became the current COA.

8

In September 1963, CUSA was re-formed as the Council for International Economic Cooperation and Development (CIECD), which in turn became the Economic Planning Council (EPC) in 1973 for the purpose of strengthening the Executive Yuan's planning and research functions. In 1977, the EPC was merged with the Executive Yuan's Finance and Economic Committee and reorganized as the CEPD.

3. Creating commissions in response to growing social and political demands: since the 1980s

Government organization tends to expand in response to growing social and political demands. The 1980s witnessed a drastic economic boost and related social and political changes. Demands for health care, environmental protection, consumer protection and social security brought about a sharp increase of statutes as well as regulatory agencies. But as indicated earlier, the Organic Act of the Executive Yuan fixes the number of ministries, and thus generates the difficulty in government reorganization. Nevertheless the law permits the Executive Yuan to set up

commissions if deemed necessary.9 The government took it as a most expedient way and quickly created many commissions to expand its structure in response to growing social demands.

As a result, over the last two decades, nineteen commissions were created through this particular provision. In table 1, commissions such as Financial

Supervisory Commission, Mainland Affairs Council, National Youth Commission, Veterans Affairs Commission, Atomic Energy Council, are all products of this expedient strategic action despite the rather rigid legal framework. Absent a coherent and consistent organizing principle, the governmental organization is evidently confusing and renders inefficiency.

B. Creating independent commissions

As discussed earlier, administrative commissions have become an ordinary means in establishing new governmental organs, but their organizational principle has

9

far from being independent. The idea of creating a real, independent commission came in after democratization and the first regime change in 2000.

1. The legal recognition of independent commissions in the government reform package

Taiwan has since the 1990s undertaken seven rounds of constitutional reform but much of the agenda was focused on the rearrangements of constitutional institutions. While much discussed, government reforms were never fully being included into part of the agenda.10 The constitutional reform of 1997, however, brought about a real opportunity. In streamlining provincial governments, two articles were also added to allow a great deal of flexibility in the arrangement of central government and lessen legal restrictions in establishing administrative agencies.11 Despite this constitutional opportunity, not much action was undertaken until the first regime change that came in four years later.

Once in power, the Democratic Progressive Party, the long-time opposition in the past authoritarian regime, took government reform as part of its major political agenda. A presidential committee on government reform was called in November 2001 and the committee was directly chaired by President Chen, Shui-bian. In June 2002, another committee on government reform was formed in the Executive Yuan

10

The introduction of governmental reform in Taiwan, please see Jiunn-Rong Yeh, Globalization

and Government Reform: Challenges and Tasks, Globalization and Blocs: Lawyers’ Perspectives,

Seoul, Feb. 23-24, 2007

11

Sec. 3, Art.3 of the Additional Article prescribes that “the powers, procedures of establishment, and total number of personnel of national organizations shall be subject to standards set forth by law.” Para. 4 of the same article reads that “the structure, system, and number of personnel of each

organization shall be determined according to the policies or operations of each organization and in accordance with the law as referred to in the preceding paragraph. The text of ROC Constitution and its Additional Articles are available

at http://www.president.gov.tw/en/prog/news_release/document_content.php?id=1105498684&pre_id =1105498701&g_category_number=409&category_number_2=373&layer=on&sub_category=455 (last visited Apr. 10, 2009)

that began to push through major bills for government reforms. One of the most important was the Standard Act of Central Executive Agencies and Organizations (hereinafter Standard Act) that was finally enacted on June 23, 2004. This Standard Act was the realization of the aforementioned constitutional provisions and was thought to be a framework guideline for the arrangement of central government agencies. It was in this Standard Act that the legal foundation for creating a real independent commission was provided for. The definition of independent commission is stipulated as “a collegial commission that acts independently in accordance with

the law and without subject to supervisions of other organs”.12 Such an independent commission is designed to have five to seven full-time commissioners with fixed terms, appointed by premier13 with legislative approval. It is also added that certain number of commissioners shall not be from the same political party.14 Upon the passage of the Standard Act, the DPP government released its government reform package with a plan to reduce thirty-seven government agencies to only twenty-four and to formally recognize five independent commissions that include a National Communication Commission.15

2. The establishment of National Communication Commission and controversies

12

See Cl.2, Sec.1 Art. 3 of the Standard Act.

13

That is, the President of the Executive Yuan, who is appointed directly by President but is responsible to the Legislative Yuan, the parliament. See Sec. 1, Art. 3 of the Additional Article.

14

See Art. 21 of the Standard Act. This is different from the way that the American independent commission would have regulated. In the American context, no political party shall dominate half of the commissioners. The reason that the Standard Act did this was, not surprisingly, partly for a political compromise and partly for subsequent statutory enactments to set up the reasonable ratio. For example, the Organic Act of the National Communication Commission now requires that no political parties shall dominate half of the commissioners.

15

The five independent commissions are National Communication Commission(NCC), Central Bank, Financial Supervisory Commission, Fair Trade Commission, and Central Election Commission.

The passage of the Standard Act seemed to provide for a momentous

opportunity for government reform, and the DPP government pressed further on the creation of National Communication Commission. Party politics, however, worsened as President Chen continued into his second term in 2004. Losing the presidential race for the second time was unexpected by the KMT, which has never ceased to be the dominant political party in the Legislative Yuan. Facing the challenge, the KMT decided to usurp its legislative dominance and boycotted major legislation, policies and budget proposed by the DPP government.16 In contrast, aided with presidential victory, the DPP pushed for further progressive reforms, part of which targeted against the KMT on its large amount of party assets and party-controlled enterprises.

The KMT was itself a media tycoon that controlled China Television Company (CTV), Broadcasting Corporation of China (BCC) and Central Motion Pictures Company (CMPC). Pressed upon the issue of its party asset and perhaps faced with financial difficulty as a result of losing presidential campaign, the KMT under the chairmanship of Ma, Yin-jeou sold rather quickly its major shares in the three media companies to the China Times Group before the end of 2005. Suspicions abound, regarding whether there were any under-table deals or whether Chinese Communist Party was even involved. The Government Information Office (GIO), at the time still in charge of media regulation, vowed to undertake a thorough investigation.17

Against this political background, it was thus easy to understand why at the time the KMT and the DPP -to a certain extent- welcomed the proposal to establish the

16

The gunshot incident that took place one day before the presidential election in 2004 and its related legal disputes afterwards also exacerbated political confrontation between the KMT and the DPP.

17

National Communication Commission (NCC).18 The KMT was pleased that the NCC would substitute the GIO, thus undermining the DPP government’s regulatory control over the media. On the side of the DPP, media reform had always been on its own agenda and it also endorsed the idea of a neutral regulatory commission.

Notwithstanding a thin agreement in the NCC creation, the two parties turned into serious confrontation as the KMT sought to entrench its political dominance in the composition of the NCC. The KMT -in defiance with the Standard Act19- came up with a novel way to appoint commissioners in accordance with the percentage of seats enjoyed by major political parties, thus leaving the Premier only ceremonial power in appointment.20 It should be noted that perhaps reactionary to the KMT’s partisan formula, some of the DPP government officials began defying the Standard Act and arguing that the NCC commissioners should be appointed directly by the Premier since all ministers must be appointed as such stipulated in the Constitution.21 A political minority in the parliament, the DPP found no way to stop the KMT’s partisan formula except petitioning its case to the Council of Grand Justices, the Constitutional Court. On November 9, 2005, the Organic Act of the National Communication

18

It should be noted that when it was made clear that the KMT might take more advantage in the creation of the NCC, some DPP members and government officials began to have a second thought on this and even opposed it strongly.

19

Art. 21 of the Standard Act provides that commissioners shall be appointed by Premier with legislative approval.

20

It was provided that a total of fifteen members of the NCC would be recommended based on the percentages of the numbers of seats of the respective parties (or political groups) in the Legislative Yuan, and, together with the three members to be recommended by the Premier, should be reviewed by the Nomination Committee, which would be composed of eleven scholars and experts as recommended by political parties (or political groups), again, based on the percentages of the numbers of seats of the respective parties (groups) in the Legislative Yuan, via a two-round majority review by more than three-fifths and one-half of its total members, respectively. And, upon completion of the review, the Premier shall nominate those who appear on the list as approved by the Nomination & Review

Committee within seven days and appoint the same list upon the confirmation by the Legislative Yuan.

See Sec. 2 & 3, Art. 4 (now abolished) of the NCC Organic Act. 21

Commission (hereinafter NCC Organic Act) was passed.22 Surrounded by protests and controversies, the commissioners were appointed in accordance with such a partisan formula23 and the NCC was established on February 22, 2006. Not

surprisingly, the NCC quickly renewed the license of BCC24 and found neither legal violations nor irregularities in the KMT’s sale of its shares in the aforementioned three media companies.

3. Constitutional court rulings and political response

In July 2007, the Constitutional Court (hereinafter Court)rendered Interpretation

No. 613, finding the way that commissioners were appointed as in violation of the

Constitution as it deprived the Premier of his powers in the determination of commissioners.25 The Court first discussed about whether it was constitutional to establish such a so-called independent commission, and if the answer would be affirmative, it would then discuss how commissioners would be appointed and whether the current way of appointment violated the Constitution.26

In terms of the first issue, the Court reasoned that “under the principle of

administrative unity, the Executive Yuan must be held responsible for the overall

22

The English translation of the NCC Organic Act is available

at http://www.ncc.gov.tw/english/news.aspx?site_content_sn=17&is_history=0 (last visited, Apr. 10 2009)

,

23

As a gesture to protest, those commissioners who were sided with the DPP government resigned their post immediately after their appointment. They also urge their colleagues sided with the KMT to resign in order to rescue integrity of this newly established institution.

24

The license was renewed in 2006. For the statement of the NCC,

see http://www.ncc.gov.tw/chinese/news_detail.aspx?sn_f=755 (last visited, Apr. 10, 2009)

25

J. Y. Interpretation No. 613 (2006/7/21). For the text in English, see http://www.judicial.gov.tw/

26

There was also a minor legal -but big in terms of political- issue concerning pending decisions at the GIO that were transferred by the NCC Organic Act to be reviewed by the NCC. The Court, however, did not find it as unconstitutional. As a result, the pending decision concerning the media company previously owned by the KMT was constitutionally transferred and remade by the NCC. Not surprisingly, the decision was in favor of the media company. See also supra note 23.

performance of all the agencies subordinate to it, including the NCC.” Because of the

principle of administrative unity, the establishment of independent agency must be regarded as exceptional and can be justified “only if the purpose of its establishment is

indeed to pursue constitutional public interests.”27 The Court derived the

exceptionality of creating independent commissions from the text of the Constitution, administrative unity, and principles of democracy as well as accountability. The Court reasoned:

“….The administration must consider things from all perspectives. No matter how the labor is to be divided, it is up to the highest

administrative head …to direct and supervise so as to boost efficiency and to enable the state to work effectively as a whole… Article 53 of the Constitution clearly provides that the Executive Yuan shall be the highest administrative organ of the state,…thus enabling all of the state’s

administrative affairs,… , to be incorporated into a hierarchical

administrative system where the Executive Yuan is situated at the top.… Democracy consists essentially in politics of accountability. A modern rule-of-law nation, in organizing its government and

implementing its government affairs, should be accountable to its people either directly or indirectly. …the Constitution is also intended to hold the Premier responsible for all of the administrative affairs under the control and supervision of the Executive Yuan,…

Accordingly, where the Legislative Yuan establishes an independent agency through legislation, separating a particular class of administrative affairs from the tasks originally entrusted to the Executive Yuan,

removing it from the hierarchical administrative system and transferring it to an independent agency so as to enable the agency to exercise its

functions and duties independently and autonomously pursuant to law, the administrative unity and the politics of accountability will inevitably be diminished.28

27

Id.

28

With regard to the second issue, the Court found that the way of selecting and appointing NCC commissioners “deprive the Premier of the power to decide on

personnel affairs of the Executive Yuan substantially,” and “thus violating the principles of politics of accountability and separation of powers.” The design of

partisan representation was criticized by the Court as against the impartiality and neutrality of the NCC.

“…it is very clear that the Executive Yuan, in fact, has mere nominal authority to nominate and appoint …members of the NCC. In essence, the Premier is deprived of virtually all of his power to decide on personnel affairs. In addition, the executive is in charge of the enforcement of the laws whereas the enforcement depends on the personnel. There is no administration without the personnel. Accordingly, the aforesaid

provisions,…, are in conflict with the constitutional principle of politics of accountability, and are contrary to the principle of separation of powers since they lead to apparent imbalance between the executive and legislative powers.

…Although the lawmakers have certain legislative discretion to decide how to reduce the political influence on the exercise of the NCC’s authorities and to further build up the people’s confidence in the NCC’s fair enforcement of the law, the design of the system should move in the direction of less partisan interference and more public confidence in the fairness of the said agency. Nevertheless, the aforesaid provisions have accomplished exactly the opposite by inviting active intervention from political parties…and, in essence, nominate, members of the NCC based on the percentages of the numbers of their seats, thus affecting the impartiality and reliability of the NCC in the eyes of the people who believe that it shall function above politics.29

Despite the finding of unconstitutionality, the Court did not immediately void the relevant provisions. It declared that the said provisions would remain in effect by

29

December 31, 2008 unless being revised earlier. It further added that “the legality of

any and all acts performed by the NCC will remain unaffected” before its final

nullification.30

With the release of Interpretation No.613, many of the DPP leaders urged an immediate resignation by the NCC commissioners in order to facilitate prompt legislative actions. But the chief commissioner, Dr. Su, refused to do so. Instead, he released his determination to the public that he and his colleagues would continue to serve till January 2008, when the term of the current legislature would expire, and urged the legislature to complete revisions no later than such a date. The revised NCC Organic Act was completed by the end of 2007, and it stipulated that the NCC should be composed by seven members with a four-year term, appointed by the Premier with legislative approval. No party shall dominate more than half of its members.31

In January 2008, the KMT won a landslide in the legislative election that was undertaken by a new electoral rule in the constitutional amendment.32 The KMT was assured its political dominance and thus not at all hurried in implementing the revised law. In March, the KMT presidential candidate, Ma, Ying-jeou won the election and assumed office in May. In August, the second-term Commissioners of the NCC were appointed by the Premier appointed by President Ma with the approval of the

legislature where the KMT occupied almost three-fourth. Now the NCC continued its

30

Id.

31

For the revised text of Art. 4 of the NCC Organic Act,

see http://www.ncc.gov.tw/english/news.aspx?site_content_sn=17&is_history=0 (last visited, Apr. 10 2009

,

32

The constitutional revision was done in 2005 to reduce the seats in the parliament from 260 to 113 and to adopt proportional representation system with two votes (one vote for party and the other for candidates).

operation with seven commissioners, three from the backgrounds telecom, one from law, two from media, and one from economics.33

33

Their respective backgrounds are available at the website of the NCC, http://www.ncc.gov.tw/default.htm (last visited, Apr. 10, 2009)

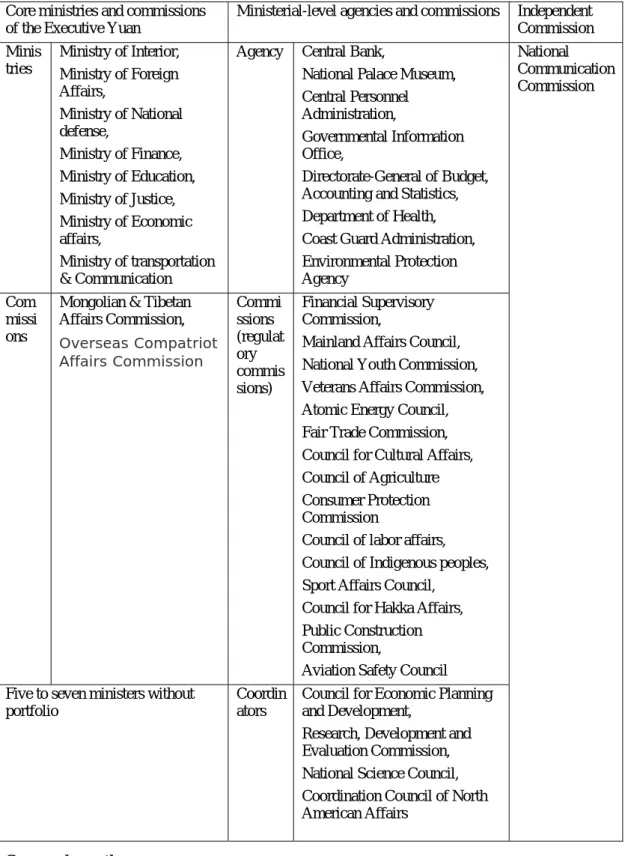

Table 1: Ministries, Commissions and Agencies of the Executive Yuan

Core ministries and commissions of the Executive Yuan

Ministerial-level agencies and commissions Independent Commission Minis tries Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of National defense, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Economic affairs, Ministry of transportation & Communication

Agency Central Bank,

National Palace Museum, Central Personnel Administration,

Governmental Information Office,

Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Department of Health, Coast Guard Administration, Environmental Protection Agency National Communication Commission Com missi ons

Mongolian & Tibetan Affairs Commission, Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission Commi ssions (regulat ory commis sions) Financial Supervisory Commission,

Mainland Affairs Council, National Youth Commission, Veterans Affairs Commission, Atomic Energy Council, Fair Trade Commission, Council for Cultural Affairs, Council of Agriculture Consumer Protection Commission

Council of labor affairs, Council of Indigenous peoples, Sport Affairs Council,

Council for Hakka Affairs, Public Construction Commission,

Aviation Safety Council Five to seven ministers without

portfolio

Coordin ators

Council for Economic Planning and Development,

Research, Development and Evaluation Commission, National Science Council, Coordination Council of North American Affairs

III. The Operation of Independent Commission and its Legal and

Institutional Predicaments

Independent commissions have been established and in operation around the globe with divergent degrees of success.34 The first independent commission in Taiwan -despite all controversies surrounding its creation- is now well into its third year in operation. In what ways would the operation of independent commissions be affected by the existing legal and institutional administrative frameworks? What factors have dominated the institutional setting and practical operations of independent commissions? For example, is constitutional government structure, presidential, parliamentary and mix systems, a dominate factor? Or, does the divide between common law and civil administrative law traditions matter? What are other hidden factors that deserve our attention? The following discussion seeks to analyze institutional and legal predicaments against which independent commissions must work to achieve their assigned functions while leaving their “independence” intact.

A. Independence from the view of constitutional structure

Presidential and parliamentary democracies assign different functions to respective presidents and parliaments. In a presidential democracy, executive functions are carried out primarily by a president and his/her departments with supervision by a parliament. Creating an independent commission with regulatory functions in a presidential democracy means to separate such a commission from the president and to block executive control over the chosen regulatory arena. Creating or

34

See e.g. Andras Sajo, Neutral Institutions: Implications for Government Trustworhtiness in East

European Democracies, in BUILDING A TRUSTWORTHY STATE IN POST-SOCIALIST TRANSITION 29-51 (J. Kornai & S. Rose-Ackerman eds.,2004) (contending not successful with regard to the experiment of independent commissions in Eastern and Central Europe.)

not creating an independent commission and to what extent it remains control by the executive is basically the fight between president and parliament.

The scenario is slightly changing in a parliamentary democracy, where executive functions are carried out by the cabinet that is subject to the will of the parliament. In this case, from which should an independent commission be independent? If an independent commission is intended to be independent from the cabinet which

however is subject to parliamentary control, is it also intended to be independent from the parliament? Here we may easily contemplate two scenarios: first is an independent commission that is independent from the cabinet but not from the parliament, and second is an independent commission that is independent from both the cabinet and the parliament. In the former, creating an independent commission -from the view of parliament- is similar to creating any agencies but only making it a little detached from the cabinet. In the latter, however, an independent commission is elevated to be independent from the parliament that centers upon party politics but also lies with ultimate political legitimacy.

Evidently challenges facing independent commissions vary from presidential system to parliamentary system. In a presidential system, independent commissions must keep attentive in relationship with the president, whereas in a parliamentary structure, they shall focus on the degree of distance from which they should be kept with the parliament. The role of independent commissions in a mixed system such as that of Taiwan would only get even muddier. In a mixed system, if the president’s political party fails to enjoy a parliamentary majority, an independent commission would have a hard time to decide from which it should be kept distance. The

parliament would certainly demand it to be separated from the president, whereas the president would demand otherwise. This was certainly reflected from the fight

between the DPP government and the KMT legislature surrounding the NCC creation. The KMT insisted to extend its legislative influence over the NCC and separated the NCC from the DPP government, whereas the DPP argued that the NCC in exercising administrative powers must still be kept under certain control with the DPP executive.

B. Independence from the view of administrative functions

In the U.S. context, one character of independent commissions is that they exercise quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial powers in additional to traditional administrative powers.35 Their exercise of quasi-powers suffices to make them distinctive from traditional administrative agencies over which the president exerts full controls.

In civil administrative law system, however, such quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial powers have been always exercised by administrative agencies. For instance, agencies are traditionally enabled to make administrative dispositions (Verwaltungsakt) that have final legal binding effects on rights and legal interests of individuals.36 Surely, individuals may make appeals to further judicial proceedings, but the exercise of these quasi-judicial powers has been in no difference between independent commissions and traditional agencies. The same to the power of making delegated legislative rules or even non-delegated rules.

35

Humphrey's Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602, 618 (1935). (regarding president’s removal power to members of Federal Trade Commission.)

36

According to Art. 92 of the Administrative Procedure Act, administrative disposition

(Verwaltungsakt) is defined as “a unilateral administrative act with direct external effects, rendered by an administrative authority in making a decision or taking other actions within its public authority, in respect of a specific matter in the area of public law. The English text is available

he

Having said that, one may wonder what -if any- renders independent

commissions a salient and novel institution in a civil administrative law tradition? Definitely not in terms of quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial powers. Perhaps in a civil administrative law tradition, collegial deliberation and related institutional setting are what makes independent commissions unique. This heightened level of deliberation in decision-making of independent commissions marks a great departure with traditional decision-making of ministries and agencies.

C. Independence from the view of administrative procedures

Suppose an independent commission exercises powers no different from agencies, what kind of “independence” it must enjoy in terms of its decisions, decision-making process and even subsequent appeals?

In a civil administrative law system, administrative dispositions may be made appeals for review by their supervisory authority.37 Before individuals litigate their cases to administrative courts, however, they must first make administrative appeals to the higher supervisory authority.38 For instance, administrative dispositions made by the Environmental Protection Agency must first be made administrative appeals to the Executive Yuan before being litigated to administrative courts.39 In the case of t NCC, should their administrative dispositions be made appeals to the Executive Yuan?

37

See Art. 3 of the Administrative Appeals Act. The English text is available

at http://db.lawbank.com.tw/Eng/FLAW/FLAWDAT0201.asp (last visited, Apr. 11, 2009).

38

See Art. 4 of the Administrative Litigation Act.

39

If administrative dispositions are made by the Executive Yuan, they would be made administrative appeals to itself. See Art. 3 of the Administrative Appeals Act.

This issue was debated in the drafting process of the NCC. If one has the

American model of independent commissions in mind, one would definitely think that administrative dispositions made by the NCC should not be reviewed by the

Executive Yuan and instead should be allowed to litigate directly in administrative courts. Interestingly however, most scholars trained in German administrative law as well as judges in Taiwan contended otherwise. They argue that making administrative appeals against dispositions is a vested individual right, and that the review of

administrative appeals is on the lawfulness of decisions rather than the appropriateness, thus posing no threat to the “independence” of independent commissions. In the end, the NCC Organic Act left open this issue without a final solution.

Even more interestingly, administrative appeal review is not done by an agency itself but rather by an administrative appeal committee. According to the

Administrative Appeals Act, every competent administrative authority (including the Executive Yuan, ministries, commissions and agencies) must set up an administrative appeals committee, half members of which must be from scholars, experts and

righteous persons with specialty in law outside such an authority.40 In other words, the appeals committee comprises more outsiders -mostly law professors and

attorneys- than internal administrative officials. Such a design is to ensure an internal independence of the appeals committee within the agency. Now it is interesting to ask whether such an administrative appeals committee should be created within an

independent commission such as the ICC, and if affirmative, how should such a committee be composed and appointed by whom? Should administrative dispositions

40

by an independent commission be reviewed -even in terms of law- by another

independent appeals committee, either of itself or of the higher authority, namely the Executive Yuan? This is again an open question in Taiwan facing the NCC. For the time being, the NCC set up an administrative appeals committee that has more than members from outside experts to review its own administrative dispositions.41

Another open question is to what extent -lesser or more stringent- independent commissions should abide by procedures required in the Administrative Procedural Act (APA). According to the APA, agencies must give individuals the opportunity to be heard before rendering an administrative disposition.42 Agency rule-making is also required to follow a notice and comment procedure.43 These requirements do not exclude their application to decision-making of independent commissions, but should they do so? Similar issues apply to the question of judicial scrutiny. Should the court take a different standard of review when it comes to decisions made by independent commissions? In the view of political accountability, a more exacting scrutiny may be argued,44 but it may well be contended otherwise if taken collegial mechanism, deliberative rationality and plural (or nonpartisan) representation into account.

D. Independence from the view of regulatory policies and budget

41

The organization and decisions of the committee are available

at http://www.ncc.gov.tw/chinese/gradation.aspx?site_content_sn=371 (last visited, April 10, 2009),

42

Art. 102 of the APA prescribes that, “An administrative authority shall, before rendering an administrative disposition to impose restraint on the freedom or right of a person or to deprive him of the same, give the person subject to the disposition an opportunity to state his opinions, unless a notice has been given to the person subject to the disposition under Article 39 hereof to enable him to state his opinions or it has been decided that a hearing will be held, except where it is otherwise prescribed by law.” English text available at http://db.lawbank.com.tw/Eng/FLAW/FLAWDAT0201.asp (last visited, Apr. 11, 2009)

43

Art. 154 & 155 of the APA.

44

Randolph J. May, Defining Deference Down: Independent Agencies and Chevron Deference, 58 ADMIN.L.REV. 429 (2006) (arguing for a departure from Chevron when it comes to review

Notwithstanding “independence”, independent commissions exercise primarily regulatory functions -quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial- most of the time. A massive amount of regulations in a modern welfare state certainly require delicate

coordination, not to mention accountability.45 Regulatory coordination takes place at least on three levels. First and foremost is at the level of budget planning. Who should be empowered to decide on how much resources must be allocated to any particular areas of administration and regulations, for instance any particular independent commission? To what extent would independent commissions be empowered to have any say in this budget allocation process? In a presidential democracy where the budget power remains at a president’s hand, in what sense would independent commissions remain independent?46 Even in a parliamentary system where a parliament barely goes into much of the details, in what ways should independent commissions be in at least budgetary coordination with other ministries and agencies?

The second level of coordination occurs in a much more mundane sense of administrative chores. Certain policies such as paper reduction, gender statistic, regulatory impact assessment or even eco-friendly office are often coordinated by president administration or cabinet office. Should these policies apply to independent commissions? Would this affect their “independence”? In contrast with mundane administrative coordination, the third type involves with much more delicate policy concerns. After all, it is difficult -and perhaps even unrealistic- to imagine that a central bank can do its job without policy coordination with other economic-related ministries as well as basic works of statistic and accounting bureaus. Nor any

45

See E. Kagan, Presidential Administration, 114 HARV.L.REV. 2245, 2331 (2001).

46

For the delicate budgetary relationship between independent commissions and the president, see RICHARD J.PIERCE,JR. ET AL,ADMINISTRATIVE LAW AND PROCESS 86-90 (4th, 2004)

independent communication commission -such as the NCC in Taiwan- in deciding licenses of competing telecommunication industries can ignore completely decisions of other equally independent commissions -such as the Fair Trade Commission- and policies of related ministries such as Ministry of Transportation or National Science Council. In what ways can any independent commissions strike a balance with such delicate relations while keep their “independence”?

E. Independence from the view of the relationship with bureaucracy There is yet another perspective in which the “independence” of independent commissions must be assessed: their relationship with bureaucracy. To ensure independence as well as high-quality of expertise, commissioners are often sought from outside and they often do not serve for a long time due to their own career concerns.47 As a result, commissioners become very much dependent upon the bureaucracy, their knowledge on the field and assessments on particular issues. They run a greater risk in being captured by a bureaucracy that represents entrenched technical biases and even worse, business interests.48 In this way, independent commissions are not really different from any of ordinary ministries and agencies. If any independence-minded commissioners choose to fight with career bureaucrats, they are only left to realize that their institutional advantages (outside expertise, term limits, and independence from the central administration) become much of their grave disadvantages (outsider, short-time, no support).49

47

Most of them, for example, are from university professors and tend to go back to universities after serving for one, two -often no more than three- terms.

48

See e.g. Katsuya Uga, Administrative Commissions in Japan (Roundtable), 4 NATIONAL TAIWAN

UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW 2 (forthcoming September 2009).

49

F. Independence from the view of state-society relationship

The last perspective in which the “independence” of independent commissions should be assessed is state-society relationship. After all, the creation of independent commissions represents distrust with the state and seeks to bring in societal influence to dismantle and even to democratize the state.50 This must presuppose an actual separation between state and society particularly regarding experts, their trainings and even to certain extent available resources. For many states especially new

democracies, however, such an autonomous society full of experts and resources simply does not exist or is still emerging. In selecting commissioners, it is more often than not that public university professors, researchers for state labs or retired senior bureaucrats would be on the list. They do not really represent even slightly different sets of knowledge, backgrounds or entrenched interests from what may be carried by traditional ministries and agencies. The same line-up may appear in ministries or independent commissions. Such rather entrenched state-society relationship posts perhaps most greater challenge for any independent commissions to gain

“independence” in their realization of regulatory functions.

IV. Theories in Explaining the Establishment of Independent

Commissions

In a modern bureaucratic governance, why one decides to designate an agency as independent in lieu of a cabinet agency or under it? One way to address this issue is subject sensitive. For example, the regulation of telecommunication, one may argue, requires an independent establishment in order to sustain social pluralism and free

50

speech.51 Scant rationale, however, could be reasonably placed as to why for example National Labor Relationship Board was designated as independent commission while Food and Drug Administration was not. An alternative way is to look into the

institutional dynamics and interest alliance of the actors including Congress,

President, Ministries and bureaucrats.52 Further, one may investigate the creation of the independent commission in particular social context, such as democratic transition or divided society.53 Divergent as they seem to present, these all lead to the question of model building in explaining the establishment of independent commissions.

A. Control, trust and insurance

Observing the development of independent commissions in a broader scope, one may easily find that states set up independent commissions in different context and for different reasons. Three models could explain this diversity.

The first can be called control model, in which the organizational form of independent commission was chosen to prevent political dominance of the current. Despite divergent variations in each independent commission, the establishment of which in the United States was primarily for the prevention of dominance by the current President54 from partisan perspective, be it bipartisan or nonpartisan. At a

51

Taiwan’s Constitutional Court interpretation No. 613 confirm the constitutionality of setting up National Communication Commission as an independent commission on the ground that it is consistent with the constitutional intent of protecting the freedom of communications and thus further ensuring the expression and distribution of diversified opinions of the society and serving the purposes of public supervision.

52

See e.g. Neal Devins & David E. Lewis, Not-so Independent Agencies: Party Polarization and

the Limits of Institutional Design, 88 B.U. L. Rev. 459 (2008) 53

See e.g. Andras Sajo, Neutral Institutions: Implications for Government Trustworthiness in East

European Democracies, in Janos Kornai and Susan Rose-Ackerman eds., BUILDING A TRUSTWORTHY

STATE IN POST-SOCIALIST TRANSITION, 29 (2004)

54

Peter L. Strauss, The Place of Agencies in Government Separation of Powers and the Fourth Branch, 84 COLUM.L.REV. 573, 589-91 (1984); Neal Devins & David E. Lewis, supra, at 464

time when members of the Congress concern the influence of the current President on policy, they tend to create independent agency to implement their policies. In this connection, non-intervention in terms of political control is essential in conceiving commission’s “independence”.

Since independence was placed against President’s control, major points of concern for the operation of independent commission are fix-term protection of the commissioners and just cause removal by the President.55 Operational transparency or level of expertise, while meaningful in constructing independent commission, is not the essential points of concern for independent commissions.

Secondly, in some societal settings where social distrust is prevailing, the organizational form of independent commission was chosen to win social trust in some regulatory areas. Society in profound transition, where large scale

reconstruction of economic and political order was in place, requires a level of stability in the flux of political exchange that generates distrust. The creation of independent commissions in the Central and East Europe, where planned economy was transformed into market economy, could be placed into this category. In trust model, control or not is not the primary concern, neutrality is. A neutral institution in transitional politics may serve to downplay short term democratic welfare

redistribution that harms long term sustainability. On the other hand, neutral institutions may be credited with safeguarding vested interest against politically motivated redistributive policies.56 Neutrality thus generates a sense of security in the flux or transitional democratic transactions. In trust model, the function of

55

See e.g. Myers v. U.S., 272 U.S. 52 (1926), Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935), and Wiener v. United States, 357 U.S. 349 (1958).

56

András Sajó, Constitution without the Constitutional Moment: A View from the New Member

independent commission goes beyond non-intervention in the control model.

Institutional betterments towards neutrality such as plural representation or diversified expertise are all called for in this context.

Thirdly, in a political insurance theory, the creation of independent commission was to prevent sliding effect arising from possible regime change and/or transitional justice deficit. In new representative democracies, where regime change suddenly becomes possible in every major national election, there is a strong tendency that major political factions would opt for a mutual insurance to prevent a worst scenario arising from the shift of powers. This is particularly true for current power holders who are not clear about next triumph, or for the defeated that are not sure about coming back. Studies show that the percentage of new agencies with insulating characteristics correlates with periods of divided government in the United States.57 The establishment of NCC in Taiwan during the DPP Administration shows strong correlation to this political insurance model.

B. Analyzing Taiwan’s social context for independent commission establishment

The development of independent commissions in Taiwan took two steps. The establishment of Chinese Expatriate Commission and Mongolia and Tibetan Commissions, in lieu of ministerial establishments, was an institutional design to serve plural representational purpose. The motive of including representatives of overseas Chinese from all continents was the underlying consideration for choosing the commission format. The same goes to the Mongolian and Tibetan Commission.

57

See David Lewis, PRESIDENT AND POLITICS OF AGENCY DESIGN, 49-55 (2003); Neal Devin and

as

This commission format in the early Republic entrenched into the late 20th century. It was until after the first regime change in 2000, the concept of independent

commission got materialized in the establishment of NCC against the backdrop of digital, and global, convergence in contentious democratic politics. Why the concept of independent commission got developed so late in Taiwan when the organizational concept of commission had taken shape so early?

The unusually long and continuous authoritarian ruling of the Nationalists has prevented the idea of constitutional check and balance from happening.58 While it w argued in Japan that bureaucrats tend to block the establishment of independent commission in terms of control, there is no clear indication of this sort in Taiwan. Democratization has brought about partisan competition in the political arena, resulting in contentious partisan politics. In a large scale government reform bid by the DPP administration soon after the first regime change in 2000, the idea of independent commission got materialized by the first establishment: National Communication Commission.

On the one hand, the establishment was initiated and carried out by the new regime, though a minority government in the Legislature, after the first regime change since democratization. On the other hand, the subject matter falls into communication regulation where prior ruling party (KMT) dominance were still of existence and free speech, critical foundation to new democracy, was of concern. The creation of NCC, the first independent commission, thus bears social and institutional underpinnings beyond control model as set forth above. Designating NCC as independent

commission was not for non-intervention by the President in power, but a way to

58

respond social transitionality. One can easily link the story to insurance model, a need recognized by both green and blue camps in safeguarding sudden political change. But the social bearing goes even further. At stake was media and telecommunication regulation, foundation to democratic consolidation in new democracies, complicated further by KMT’s ownership of radio, television and newspaper even after regime change. The deficit of transitional justice in partisan politics placed great hope for NCC, maybe too heavy a burden but at least it was so desired.

V. Capacity-building for the “Independence” of Independent

Commissions

Designating a public body as independent is one thing, whether and how it could sustain independence in day to day political dealings is quite the other. Institutional capacity-building towards independence, be it desirable or not, has been a critical challenge to modern independent commissions. In line with the social context argument above, institutional capacity building should be advanced in accordance with the explaining models set above.

A. Analyzing independence: of plural representation, neutrality, and independence

Under control model, non-intervention by the current governing power was the key to underpin independence of the independent commissions. The corresponding institutional arrangement for it was just cause removal requirements. This

non-intervention/just cause removal thesis, however, only set up a basic foundation under control theory. It fails, however, to provide sufficient foundation under trust model, by which the establishment and operation of independent commission was to

win social trust in the flux of transitional political exchange. Neutrality, an

institutional conscious resistance to take side, be it on religious, partisan, factional or ideological grounds, was deemed to be essential to win social trust.

Neutrality has been promoted in some aspects of the regulatory framework for a long time. This could take various forms. Being religiously neutral has been a value imposed to administrative function in modern administration. Neutrality of the bureaucracy has been a build-in element of democracy to prevent instability arising from constant regime changes following elections. In the East and Central European context, the institutional interests of the inherited agencies and the shrinking of government activities and large scale privatization have increased the need for neutral regulatory agencies.59

Independence in an insurance theory, however, goes beyond being neutral, their must be something extra to impartiality. Being neutral and neutral only, an

independent commission may avoid making a timely and right decision. Indeed, in democratic transitional social context, it is beyond a luxury to expect every decision by independent commission to be “neutral” or color blind. Every decision by

independent commission must take side; there is no way for their decisions not to be characterized as “partisan.” Accordingly, the reading of independence should go beyond being neutral or impartial, but responding to social need with convincing argumentation.

By the same token, independence in so reading is different from plural representation, so mechanism regarding partisan or non-partisan representation or interest-group representation is helpful, but not essential.

59

B. Institutional capacity-building towards meaningful independence If a creation of independent commission were to succeed, what are their

institutional requirements? In a situation where the expectation to independence goes beyond being neutral, what should be on the top of it? The spatial gap between neutrality and independence in fact marked the legitimacy of independence. What in this spatial zone? Possible answers to it could include institutionally built-in expertise, procedural rationality, and nature of regulated areas. Institutional capacity building along this line all account for extra legitimacy.

Note, however, the difficulties of making each decision accountable by independent commissions; thus the assessment should be placed on institutional foundations and capacity-building to making credible decisions in the long run. Transparency, collegial deliberation, and diversified expertise are all essential elements for institutional capacity-building. But, maybe more importantly, the scope of the power conferred to independent commissions must be confined to areas of adjudicatory nature.

VI. Conclusion

Independent commission as an organizational form developed originally in the United States and evolved into modern days.60 Similar concept was introduced in other soils with divergent social context that dictates the function and corresponding institutional capacity of independent commission. The creation of NCC in Taiwan exemplified a unique social context that makes the very conception of agency independence different from its American counterpart. Regime change, transitional

60

constitutional order, transitional justice deficit and global networking are salient features involving the creation of the first independent commission. Combined, these social backdrops form a model of independence beyond the conception of control or intervention. Broader institutional and operational capacity-building must be shown in order to live up to the social trust and contextual needs of democratic transition.