A Study of EU-China relations EU-China Relations after China’s WTO Entrance in 2001 Does the EU need a new China-Policy?

全文

(2) 論文題目 Thesis Topic. Student:Erik Jan Class Professor:Wang Ding-Shu. 國立政治大學 亞太研究英語碩士學位學程. 立. 治 政 碩士論文 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 A Thesis. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. Submitted to International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific Studies National Chengchi University. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the degree of Master in China Studies. 中華民國 101 年 7 月 July 2012.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(5) Acknowledgement. I hereby want to express my gratitude to all those who helped me finish my thesis. It gives me great pleasure in acknowledging the support and help of Professor Wang Ding-Shu. His help, stimulating suggestions and encouragement helped me throughout the research and writing of this thesis. In addition, I appreciated the very helpful guidance and insightful comments. 政 治 大 I also want to thank Jennifer Chang, David Musayelyan and Ben Burkhard for their 立 of Professor Wu Chun-Kuang and Professor Lien Hong-Yi.. great help and assistance during my studies.. ‧ 國. 學. My special thanks go to my Mother, Father and sister. Their continued support. ‧. and encouragement helped me to finish my thesis.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(6) Abstract. China's rise is the most important change in our time. China with a population of 1.3 billion, annual economic growth rates above 10 percent and a successful economic transition has become the second biggest economic power worldwide. Since its economic opening, initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China has gradually opened itself, welcomed international investors for Foreign Direct Investment and advocated. 政 治 大. international multilaterism. At the same time, China has successfully. 立. secured its own interests. Beijing has, while keeping its currency. ‧ 國. 學. artificially low, implemented several economic and trade policies, which mostly benefit Chinese companies. At the same time, China reacts highly. ‧. sensitive to interference in internal affairs and even punishes states,. y. sit. Nat. which are too critical of the Chinese government. China’s new, strong. er. io. role has also transformed the unipolar international system, which was. n. a States after the end ofvthe Cold War, towards a dominated by the United i l C n h e nsee multipolar system. Many actors h i U within a rapidly changing g cthemselves international system and are forced to react to the environment and conduct appropriate foreign policies towards China. This paper discusses EU-China relations from 2001 to 2009 and examines EU’s foreign policy towards China. The purpose of this study is to determine the weakness of Brussels’ China policy and to answer the question of whether or not the EU needs to adjust its policy in order to create a more thorough stance towards China. Keywords: EU, China, foreign policy, EU-China relations, economic rise.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 8 1.1. Importance and Purpose of Study .................................................................... 8 1.2 Literature Review and Methodology .............................................................. 25 2. EU-China Relations ............................................................................................. 31 2.1. EU-China Relations from 1949-2001 ............................................................ 32. 政 治 大 2.3 EU’s Foreign Policy towards China ................................................................ 36 立 2.2. EU-China Relations from 2001-2009 ............................................................ 34. 2.3.1 EU’s policy of Unconditional Engagement .............................................. 39. ‧ 國. 學. 2.4. China’s Foreign Policy towards the EU ......................................................... 44 3. The Impact of the United States on EU-China relations ........................................ 52. ‧. 4. The Role of EU Member States in EU-China relations ......................................... 54. Nat. sit. y. 5. The Role of the “Big Three” in EU-China Relations ............................................ 63. io. al. er. 5.1 Germany in EU-China Relations .................................................................... 63 5.2 France in EU-China Relations ........................................................................ 67. n. v i n 5.3 Great Britain in EU-China 70 C h Relations .............................................................. U i e h n gc 6. Conclusion and Policy Implications ..................................................................... 74.

(8) 1. Introduction. 1.1. Importance and Purpose of Study. China's economic rise is the epochal change in our time. With annual economic growth rates of 10 percent over the past 40 years, the country with a population of 1.3. 政 治 大. billion has advanced to become the second biggest economic power, and leading export. 立. nation. China was in the 1970s, still an economy under autarky conditions, it is now the. ‧ 國. 學. central industrial workshop of the world. Both, China’s process of industrialization and the transformation from a socialist planned economy to a capitalist market economy were. ‧. successfully.. Nat. sit. y. The Middle Kingdom has managed many different development stages, such as. n. al. er. io. modernization of its agriculture, opening the country to trade and foreign direct. i n U. v. investment, privatization of state-owned enterprises, the establishment of an efficient. Ch. engchi. infrastructure, reform of the financial sector, the growth of its exports, the development of the domestic provinces and the strengthening of rule of law, improvements of government administration, macroeconomic control and public services. 1 The number of absolute poor in China has declined significantly as part of that process. The World Bank estimates, that around 407 million people have emerged from the absolute poor to the. 1. Andrew J. Nathan and Tianjian Shi, China's Transition (New York Columbia University Press 1999),. 336, Doug Guthrie, China and Globalization: The Social, Economic and Political Transformation of Chinese Society (New York and London Global Realities, 2008), 44.. 8.

(9) growing middle class – and that in less than 15 years (from 1990 to 2004) 2 . China's dynamic development is also reflected in the global financial and economic crisis in 2007-2009 –as well as in the Asian crisis of 1997/98 – when the Chinese economy deflected the crises. 3 During the crisis in 2009, among the world's largest economic powers, only China was able to make substantial contribution to world economic growth. 4 China's rapid rise, resurgence of its old size 5 and its international integration is, given the scale of the country, the historical challenge of our time. Due to the size of the country, China's economic growth has immediate consequences for international politics,. 政 治 大 While China's economic rise – beyond frictions and the effects of worldwide 立. foreign relations, world trade, the global investment and capital traffic.. redistribution - has created an overall economic win-win situation, the political rise of the. ‧ 國. 學. country is ambivalent to assess. First of all, affected by the People's Republic’s increase. ‧. of power, both the United States, whose hegemonic role is threatened, as well as Europe,. sit. y. Nat. are threatened to be marginalized or at least forced to give up influence and power. In. io. er. matters of global governance China is now an actor who competes with the EU, therefore the idea of a G2, consisting of the United States and China, attracts certain attention. n. al. Ch. among pragmatic-realist circles in Washington.. engchi. i n U. v. A lot of attention has been paid to how Washington is reacting to the PRC’s growing economy and political influence; however, it seems that the relation between the 2. Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, “The Developing World Is Poorer Than We Thought, but No Less. Successful in the Fight Against Poverty” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, MIT Press, vol. 125(4), (2010): 1577-1625. 3. Peter Nolan “China in the Asian Financial Crisis,” (Cambridge: University of Cambridge 2004): 300.. 4. Fan Junmei “Experts: China little affected by US financial crisis” China.org.cn, (Septembter, 19.2009),. accessed July, 01. 2012, http://www.china.org.cn/business/news/2008-09/19/content_16504424.htm. 5. The economist Angus Maddison calculated that China contributed in 1820 one third to the World GDP.. Angus Maddison, “Chinese Economic Performance in the Long-Run,” Paris: OECD Development Centre, (1998).. 9.

(10) European Union and China has been rather neglected by the academic world. The bilateral relations of different European countries towards China have been especially neglected. 6 EU’s economic power and Soft Power and China’s rapidly rising political and economic power are strong reasons to take a thorough look at the interactions of the two actors. Even though the Washington – Beijing relations are comparatively much more dynamic and controversial, but taken in mind, that the European Union is the largest economy worldwide and thus, arguably the strongest economic player, 7 China and its huge population of 1,3 billion citizens means chances for cooperation as well as risks for. 政 治 大 Both, EU and China, have keen interests to establish close and stable 立. conflicts. In the last 20 years trade between the two global actors has developed impressively.. 8. relations. In other words, China’s miracle-like economic growth and strengthening. ‧ 國. 學. economic, political and military power implies great opportunities and risks. Only a. ‧. strong and comprehensive foreign policy of the EU is able to manage the deepening. sit. y. Nat. relations and secure EU’s interests.. io. er. However since its establishment, the EU has been scrambling to build an effective, democratic and consistent foreign policy which enables the EU to deal in world politics.. al. n. v i n C h the main objectives In 2003 the EU Commission published of the EU’s China-policy : engchi U 6. 9. Eberhard Sandschneider, “China’s Diplomatic Relations with the States of. Europe”, The China Quarterly, 169: 33-44. (2002): 33. 7. According to the World Bank and the CIA Factbook, the European Union has been over the past two. centuries the biggest economy. World Bank https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/fields/2195.html, CIA Factbook http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD/countries. 8. Josh Fineman and Alexis Leondis, “Europe Overtakes North America as World’s Wealthiest”, Bloomberg,. (September 15, 2009), accessed July 1, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aL5a46f2RjVA. 9. European Commission, “A maturing partnership - shared interests and challenges in EU-China relations. and the Chinese government,” (August 9.2003), accessed July 1.2012, http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2000:0552:FIN:EN:PDF.. 10.

(11) The main goals of its policy is to assist the PRC’s economic opening and governance and the EU aims at assisting China’s transition to an open economy and a society based on the rule of law and the respect for human rights. The most important part of the bilateral relations between the EU and China relations has been trade. China is Europe’s second biggest trading partner (after the United States) and bilateral trade is accelerating even further. After China’s opening under Deng Xiaoping, a growing number of European companies, mainly from Germany, France or the UK have been active in China since the late 1990s. Through investing in. 政 治 大 China in developing their country and helping to pursue an economic transformation. 立 Chinese factories and pursuing technology transfer, western companies are assisting. Moreover, the political relations between the Brussels and Beijing have been improving. ‧ 國. 學. as well since 2001. The most important factor for this development was certainly the “US. ‧. factor". Georg W. Bush’s “War on Terror” and his invasion of Iraq led to alienation. sit. y. Nat. between the “old continent” and the Washington. The German chancellor Gerhard. io. er. Schröder (1998 – 2005) and the France’s President Jacques Chirac (1995 - 2007) were the strongest opponents against the Bush administration’s “War On Terror”. The. al. n. v i n C h between the EU disagreement damaged the relationship and Washington, and let Brussels engchi U. balanced towards other states, especially towards the PRC. 10 It is not surprising that the period from 2003 to 2004 has been described as a “honeymoon” between the EU and China. 11 Furthermore polls among Chinese indicate that Chinese citizens had a very positive view of the EU. During that time a long list of mutual high level visits in China and the EU signalize the warm relations between the two on all levels. In 2003 Brussels 10. CNN, “China adds voice to Iraq war doubts”, (January 23, 2003), accessed July 1. 2012,. http://edition.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/asiapcf/east/01/23/sprj.irq.china/index.html. 11. Zhu Liqun “Chinese perceptions of the EU and the China-Europe relationship”, in China-Europe. Relations: Perceptions, Policies and Projects, ed. David Shambaugh, Eberhard Sandschneider and Zhou Hong, (Londong and New York: Routledge, 2008): 43.. 11.

(12) and Beijing published a new political agenda, which strengthened closer ties between the two players and facilitated a comprehensive framework of bilateral relations (European Commission (2003): “A maturing partnership - shared interests and challenges in EUChina relations” and the Chinese government (2003): “China’s EU policy paper”). However during the year of 2005 the relations between Brussels and Beijing cooled down significantly. One of the reasons was a rising trade deficit of the EU and pressing issues, such as granting China a market economy status, several anti-dumping cases in the WTO 12 China has been pursuing an economic transformation from an export-. 政 治 大 quality, high technology goods, produced for its own market. For reaching this long-term 立 oriented economy towards a more economic structure, which is mainly focused on high. goal of economic transition, China is more in need for foreign technology and knowhow. ‧ 國. 學. and Beijing has, while keeping its currency artificially low, implemented several. ‧. economic and trade policies which for instance forces foreign companies to build-up. sit. y. Nat. joint-ventures with Chinese companies, and to open-up there technology and prohibit. io. er. them to transfer their profits back to their headquarters. As the European Union institution, EUbusiness, states “Growing nationalism and lobbying by local firms is making China. al. n. v i n C h foreign firms.”UWhile the trade volume has been more protectionist and hostile towards engchi 1. rising annually, so has the trade deficit. In 2009, imports from China were 215 billion Euros; Exports were only 80 billion, which is approximately a trade deficit of more than 130 billion Euros. And the gap is rising year by year. The same negative trend can be observed when looking at FDI. In 2009, European companies invested more than 5.3 billion Euros, however the inflow of Chinese investments was only 0,3 billion Euros. This trend has created huge concerns among the EU and its member states. It was just last year that German top managers from the two biggest investors in China (Siemens and BASF) 12. David Barboza and Paul Meller, “China to Limit Textile Exports to Europe,” New York Times (June 11. 2005), accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/11/business/worldbusiness/11textile.html.. 12.

(13) have for the first time articulated their concerns about China’s trade policies. 13 Interestingly enough, immediately after the meeting, Wen JiaBao, the Chinese Premier, denied all accusations by the German delegation and stated that the remarks by the German managers "… not exactly correspond to our views of a partnership”3 During the last EU-China summit in October 2010, European politicians were eager to address their complaints again and try to persuade their Chinese counterparts to stop pressing down the Chinese currency Yuan, but all demands by the EU were blocked by Beijing’s officials. Policymakers in Brussels seem to be disillusioned about the extent and speed at which the. 政 治 大 is taking place. In 2007, warned the former EU Trade Commissioner, Peter Mandelson, 立 expected convergence of the Chinese economic system with Western market economies. that the trade relations with China would be “at the crossroads”.. ‧ 國. 學. However, not only did the EU face difficulties in pursuing its economic interests,. ‧. but starting 2005 several political conflicts came up, which further pressured bilateral. sit. y. Nat. relations. Most importantly China has been increasingly putting pressure on the EU to. io. er. abolish its weapon embargo. The embargo was imposed on China after the Tiananmen Square Incident of 1989. 14 Already in 2004, on the height of bilateral relations, China. al. n. v i n C h the EU and itsUmember states into an abolishment was very close to successfully talking engchi. of the weapon embargo, only a severe interference of the United States, which has an immense interest in a continued embargo, prevented it.15 After China was not able to push the EU to lift the arms embargo, it changed its approach in response and moved its efforts away from EU institutions, especially EU Commission, and put more pressure to 13. Euobserver, "German business chiefs criticize China”, (July 19.2010), accessed July 1. 2012,. http://euobserver.com/884/30499. 14. Gudrun Wacker, “Lifting the EU arms embargo against China U.S. and EU positions,” German Institute. for International and Security Studies, (February 2005), 13, accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/2005_02Wkr_eu_embargo_ks.pdf. 15. Ibid., 14.. 13.

(14) the key member states. 16 As a result several EU countries, most importantly France, Germany and Spain, agreed to vote for a lifting of the embargo the lobbying of Chinese delegates. However despite convincing several EU member states, China could build up a majority inside the EU and a final decision of the EU has been delayed. 17 The above mentioned problems between the players showcase the inability of the EU to pursue its own interests. Several EU-experts, politicians and think tanks have fiercely criticized EU’s weak policy. 18 Very intriguing is that the pan-European think tank, European Council on Foreign Relations, annually publishes the “European Foreign. 政 治 大 towards other important countries. EU’s policy towards China has been disapproved 立. Policy Scorecard” in which the researchers examine and discuss EU’s foreign policy. several times and granted with a low grade of “C+” or “C”. 19. ‧ 國. 學. This paper aims to contribute on European foreign and security policy applying a. ‧. multilevel model which takes all factors, which are influencing the EU’s foreign policy,. y. sit. William A. Callahan, “Future imperfect: The European Union’s encounter with China (and the United. io. States),” Journal of Strategic Studies, Volume 30, Issue 4-5, (2007):. n. v i n Andrew Retman, “EU to keep ChinaC arms despite massive investments,” euobserver, January h eembargo ngchi U. 777-807. 17. al. er. 16. Nat. into account. The main purpose of this study is to explore if the EU’s foreign policy has. 05.2011, accessed July 1. 2012, http://euobserver.com/884/31592,. Euronews, “Reservations remain on lifting EU’s China arms embargo,” (February 05.2011) accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.euronews.net/2011/01/05/reservations-remain-on-lifting-eu-s-china-arms-embargo/. 18. Hans G. Hilpert, Strategischer Wirtschaftsdialog der EU mir China,” SWP-Aktuell, 43, 1-4 (May 2008),. accessed July 1.2012. http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/aktuell/2008A43_hlp_ks.pdf, François Godement Jonas Parello-Plesner, et al., ”The Scramble For Europe,” European Council on Foreign Relations, (July 2011), accessed July 1 2012 http://www.ecfr.eu/page//ECFR37_Scramble_For_Europe_AW_v4.pdf, Katinka Barysch and Charles Gran, et al., “Embracing the dragon The EU’s partnership with China,” Center for European Reform, (May 2005), 18. 19. The European Council on Foreign Relations China Overall grade C+ http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-. /ECFR29_2010_SCORECARD_CHINA.pdf, The European Council on Foreign Relations, EUROPEAN FOREIGN POLICY SCORECARD 2012 http://www.ecfr.eu/page//ECFR_SCORECARD_2012_WEB.pdf.. 14.

(15) failed to reach the main objectives of its China-policy and if there needs to be a new policy towards Beijing. The timeframe of this paper is from 2001 when China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and finally entered the international world stage fully, and ends in 2009 with the beginning of the European sovereign debt crisis. The second main purpose of this study is to determine the main factors involved. The following purpose is to explain how these factors are influencing EU’s China policy. The last purpose of this study is to explain why these factors lead to an ineffectiveness of. 政 治 大 EU and China. Only in chapter 3, where the impact of the Unites States on EU-China 立. the EU’s China policy. This study will mainly focus on the bilateral relations between the. relations is discussed, the role of other actors is neglected. It is argued that other powerful. ‧ 國. 學. states, such as Russia have a weak influence on EU-China relations during the discussed. ‧. time frame of 2001-2009.. sit. y. Nat. The main question can be divided in hypothesized proposition and several sub-. io. n. al. er. questions. The Hypothesized propositions are as followed:. i n C h policy towards China? 1. What characterizes the EU foreign engchi U. v. 2. In which way do the EU Member States weaken a coherent common foreign policy of the EU? 3. How do the United States influence Brussels’s foreign policy towards China? 4. How is China approaching the EU? 5. How do the “The Big Three” (Germany, France, UK) and their national policies influence EU’s China policy.. 15.

(16) In this study it is hypothesized that the EU’s China-policy is insufficient since China’s WTO accession. This hypothesis can be further developed into the following logically consequential sub-propositions:. 1. The EU has adopted a rather weak foreign policy towards China.. 政 治 大 country’s transition. They argue that Beijing has been incrementally integrated into the 立 European Member States believe that China's peaceful rise as the most likely result of the. major multilateral organizations. This view is rooted in the European experience of. ‧ 國. 學. economic integration, the support of democracy and regional integration. Traditionally. ‧. European Member States support the idea that the democratization process in China can. sit. y. Nat. be promoted by engaging China. Because of a less security commitments in East Asia. io. er. (Taiwan or Japan), the EU has been much more willing to strengthen economic interactions and generally engage with China. One part if this engagement is the idea, that. al. n. v i n C hcan be familiarizedU with international standards and through political dialogue China engchi. behavior and finally is a responsible member of the international community. In an open world economy newly-rising economic powers have been relentless agents of structural change. As they moved into manufacturing they quickly took over low- tech, labor intensive manufacturing, climbing the technology ladder more or less quickly. After a devastating World War II, European countries’ fast economic recovery and the two warlosers Germany and Japan were successfully integrated into a stable international system. The two scholars John Fox and François Godement used the term “unconditional engagement” to describe EU’s policy towards China. According to them 16.

(17) “… the EU’s China policy is based on an anachronistic belief that China, under the influence of European engagement, will liberalize its economy, improve the rule of law and democratize its politics”. The underlying idea is that engagement with China is positive in itself and should not be conditional on any specific Chinese behavior.” 20 The term “unconditional engagement” was introduced by Constantine C. Menges, when he described US foreign policy towards China. He wrote the opposite of unconditional engagement. 政 治 大 enormous economic benefits accruing to China from trade with the US as an 立. “… is not isolation, but rather a policy of realistic engagement. This would use the. incentive for its acting peacefully and cooperatively internationally and it’s. ‧ 國. 學. complying domestically with the human rights commitments China has freely. ‧. assumed.” 21. sit. y. Nat. Applying the term of unconditional engagement Fox and Godement criticize EU. io. er. politicians that the theory that economic development and economic exchanges between the West and China will establish Western values such as democracy, rule of law and. al. n. v i n human rights in China. One of C the main pillars of this h e n g c h i Uapproach was China’s entrance to the WTO in 2001. Believing in this approach Brussels has been trying to persuade Beijing. that the EU’s demands, such as rule of law or climate change, are also in the interests of China. However, as many observers argue, the hopes of the EU have been disappointed. Since China has become a WTO member the reform has been slowed down or even 20. John Fox and François Godement, “A Power Audit of EU-China Relations”, European. Council on Foreign Relations, 1. accessed, April 1.2009, July 1. 2012, http://ecfr.3cdn.net/532cd91d0b5c9699ad_ozm6b9bz4.pdf. 21. Constantine C. Menges, “China: a Policy of Realistic Not Unconditional Engagement,” Hudson Institute,. http://www.hudson.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=publication_details&id=3175&pubType=RusChin.. 17.

(18) stopped. 22 The case of WTO also shows that the hopes of the EU have been disappointed: “Examples of Europe’s failure to mould China in its own image are legion. Political liberalization seems to have stalled, or even reversed: China has tightened restrictions against NGOs, stepped up pressure on dissidents, and stopped or rolled back local electoral reforms. At the UN, Beijing has built an increasingly solid coalition of general assembly votes, often mobilized in opposition to EU values such as the defense of human rights.” 23. 政 治 大 2. EU Member States follow a national, short term oriented policy rather than 立 supporting a coherent EU China policy.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 sit. y. Nat. As the US-China Congress Commission writes even if the EU-China relations have been. io. er. becoming more comprehensive, the final word still lies with the Member States: “although the European Union will continue to play a greater role in shaping a. al. n. v i n C h policy among member common foreign and security states, implementation of any engchi U comprehensive policy, especially for China, is complicated by the fact that while. 22. Hans G. Hilpert, „Chinas globale wirtschaftliche Herausforderung - für eine kohärente. Außenwirtschaftspolitik Europas,“ Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit, (Dezember 2010), accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2010_S29_hlp_ks.pdf, Margott Schüller, “The EU’s Policy on China on Economic Issues: Between Disillusion and Dialogue.” In American and European Relations with China, Advancing Common Agendas, David Shambaugh, Gudrun Wacker, ed., Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit, (December 2010), 65-78, accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2008_RP03_shambaugh_wkr_ks.pdf. 23. John Fox and François Godement, “A Power Audit of EU-China Relations”, European. Council on Foreign Relations,( April 1.2009, July), 1, accessed, 1. 2012, http://ecfr.3cdn.net/532cd91d0b5c9699ad_ozm6b9bz4.pdf.. 18.

(19) the EU has assumed significant responsibility for management of external trade relations, member states have retained final authority over security policies, the most critical security-related decision will be determined at the national level” 24 This paper emphasizes the importance of the political structural framework of the EU. It is argued, that at the national level of 27 member states, which all have different political and economic interests towards China and therefore a different political agenda in Beijing, have a main effect on EU’s China policy. This creates, as this paper argues, a political environment, where it is difficult for the policy makers in Brussels to build a. 政 治 大 words, the potential of the European Union to pursue its long term goals towards China is 立. political consensus in the EU and implement a coherent policy towards China. In other. (mostly economic) short-term advantages.. 學. ‧ 國. undermined by unilateral actions of the EU member states, who are interested in gaining. ‧. For example, Germany as the biggest trading partner of China within the EU lifted its. io. er. bypass a common EU approach. 25. sit. y. Nat. bilateral relation with the PRC by starting an “intergovernmental consultations” and. Furthermore, EU Member states can be divided into different groups according to. al. n. v i n C hTheir policy is mostly their foreign policy towards China. driven by economic interests or engchi U political goals such as human rights or environmental protection. One of main factors is how to build a united front to deal with economic issues. The 27 EU Member states compete for business in China and either unilaterally lean towards Beijing or a national. 24. May-Britt Stumbaum, “Engaging China – Uniting Europe? The EU’s Common Foreign and. Security Policy towards China”,. in The Road Towards Convergence: European Foreign Policy in an Evolving International System, Costanza Musu and Nicola Casarini (eds.), (London: Palgrave MacMillan), 65. 25. inhuanet, “China, Germany to launch inter-governmental consultation”, (April 1 2011), accessed July 1. 2012, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-04/01/c_13809476.htm. 19.

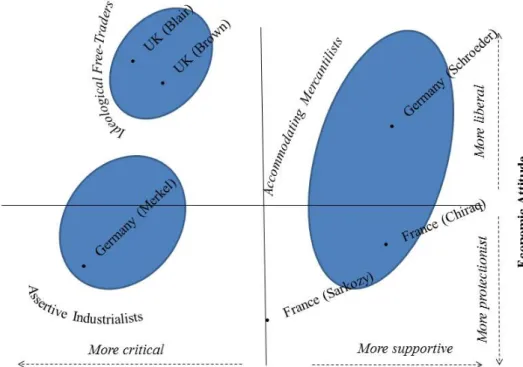

(20) government criticizes Beijing. The ladder has proved to be rather ineffective; the Communist Party tends to ignore the opinion of “smaller and unimportant” countries. However, Germany UK, Italy and France, have gained from China’s huge demand for machinery and other high quality products. Other EU countries, who are directly competing with Chinese exports in labor-intensive manufacturing, such as textiles or shoes, take a more assertive standpoint against China. In the “battle of investment and export” many Member States are willing to abuse short-term advantages. There seems to be a sort of “before-it-is-too-late-mentality”. Some EU Member States seem to ignore that. 政 治 大 interests such as technology transfer and intellectual property rights. 立. this behavior not only undermines a coherent EU strategy, but also might risk long term. Moreover, Member States follow the belief that they have more to gain from a. ‧ 國. 學. national China policy than from an integrated EU approach. Many Member states transfer. ‧. more “uncomfortable” topics, such as human rights or Tibet to the EU to deal with. They. sit. y. Nat. rather focus themselves on topics which won’t create irritations with China in order to. io. er. have smoother bilateral relations with Beijing. The paper uses the results of the recently published study by the European Council on Foreign relations, EU-China relations have. al. n. v i n Ch been analyzed on the basis of questionnaires and interviews conducted in all 27 member engchi U. states, in Brussels institutions and in China. The paper divides the 27 EU member states into different categories according to their China-policy:. • “Assertive industrialists” • “Ideological free-traders” • “Accommodating mercantilists” • “European followers”. 20.

(21) The focus of this analysis lies on China’s three biggest trading partners in Europe: Germany, UK and France. These three major EU members, also called the “Big Three” states have been the key players in influencing the bilateral relations between Brussels and Beijing. It will be explained how the bilateral relations with each partner has developed since the year 2001. A special focus will lie on how the three countries have been involved within the decision making process of the EU. In other words, it will be explained how the EU member state while following their own national policy, lead to an incoherent EU China-policy.. 立. 政 治 大. implement a comprehensive foreign policy.. 學. ‧ 國. 3. The United States, are affecting EU-China relations in a way that the EU cannot. ‧ sit. y. Nat. io. er. After the end of World War 2 the hesitance of West European Powers in their ambition to secure US involvement in Europe while keeping an independent foreign. al. n. v i n C h between EuropeU and China. influenced the relations engchi. policy also. Under US pressure,. Western European states were hesitant to establish full diplomatic relation with China. The North European countries and the Dutch government were an exception and immediately recognized the new Chinese government after its establishment in 1949. 26 The French government finally established full relations with Beijing in 1964, however, Washington’s pressure still kept other European states to seek diplomatic ties with Beijing. Thus, West Germany established diplomatic relations with the PRC only in 1972.. 26. The Netherlands in 1950 was the first Western European government to do so.. 21.

(22) Until now, the main external influencing factor of EU-China relations is the US. The US and EU have traditionally close ties and also seek similar interests towards China. However one of the main issues which have been influencing EU-China relations is the questions of lifting the weapon embargo. Not only has Beijing vehemently lobbied in EU capitols, but also EU Member States with big weapon companies, such as France, Germany or Britain have had growing interest to (partly) lift the embargo. However, a transfer of EU weapon technology to Asia’s rising power is strongly opposed by Washington. The US, which has military interests in Asia and has wide military. 政 治 大 power to stop a lift of the embargo. One of the reasons why the EU and the US has been 立 responsibilities in East Asia (Taiwan, North Korea), has several times used its diplomatic. clashing so vehemently over the arms embargo is that Americans and Europeans tend to. ‧ 國. 學. interpret the rise of China rather differently. Even if the two sides sorted out their. ‧. differences on arms sales tomorrow, China would remain one of the key topics in. sit. y. Nat. transatlantic relations for years to come. However, existing transatlantic institutions are. io. al. n. policies on arms sales.. er. not well suited for the EU and the US to exchange their views and co-ordinate their. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 4. China is rising and becoming more powerful, at the same time, it has adopted an effective foreign policy which exploits institutional shortcomings in the EU-system. The Chinese government is successfully using the political system of the EU to its own advantage. Beijing follows strategies of “divide e impera” (“divide and rule”) and “using the barbarians to control the barbarians” (yiyi zhiyi). 27 Fox and Godement describe China’s skillful EU-policy as a “game of chess, with 27 opponents crowding the other 27. Nicola Casarini, “Remaking Global Order: The Evolution of Europe China Relations and Its Implications. for East Asia and the United States”.(Oxford: Oxford University Press 2009): 24.. 22.

(23) side of the board and squabbling about which piece to move.” 28 As a China-expert commented “they push us much as they can and hope to create a crack in the EU common front.” 29 The EU Member States (in particular the large ones have adopted commercial strategies towards China aimed at promoting their national companies' business interests. As long as European Member States are willing to betray each other, the Chinese leadership can easily exploit this situation. Such a strategy is being skillfully implemented by the Chinese leadership in order to obtain political concessions. One important issue in EU-China relations is the question of whether the EU. 政 治 大 the EU on the People's Republic of China as a reaction to the Communist Party’s 立. should lift its arms embargo against China. The arms embargo on China was imposed by. suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. 30 14 years later, France and. ‧ 國. 學. Germany started a discussion on lifting the ban. In late 2003 the Chinese Ministry of. ‧. Foreign Affairs issued its very first policy paper on the EU. The document called for. sit. y. Nat. improved military relations and repeated its desire for a lifting of the arms embargo.. io. er. Beijing since the introduction of the arms embargo has put great efforts to lobby for an end of it. Besides ongoing demands by the Chinese government to lift the arms embargo,. al. n. v i n C hEU were to lift its U Beijing also has argued that if the arms embargo it would allow EU to engchi. 28. John Fox and François Godement, “A Power Audit of EU-China Relations”, European. Council on Foreign Relations, (April 1.2009),5, accessed, July 1. 2012, http://ecfr.3cdn.net/532cd91d0b5c9699ad_ozm6b9bz4.pdf. 29. May-Britt U. Stumbaum, “The EU and China. EU Decision-Making in Foreign and Security Policy. toward the People’s Republic of China", (Baden-Baden: Nomos 2009), 99. 30. Gudrun Wacker, “Lifting the EU arms embargo against China - U.S. and EU positions,” Presentation at. the 1st colloquium of the TFPD-Working Group "China's Rise", 17th February 2005, Washington, DC, 3, accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/2005_02Wkr_eu_embargo_ks.pdf .. 23.

(24) sell high value high technology products. 31 The European Union was divided within itself on lifting the embargo. France and to a lesser extent Germany were the main forces within the EU in calling for closer relations with China. In 2004 Paris even declared 2004 as the ‘Year of China’ and holding joint naval exercises. 32 France and Germany were also the two European states which pushed for the initiative to lift the embargo. 33 France and Germany and also the United Kingdom and Italy were interested in extending its export to and sell arms sales to China. The initiative was proved by the European Parliament but was finally stopped. After the unsuccessful attempt by Beijing, the Chinese government. 政 治 大 Member States, especially with the German, British and French government. 立. decided to pursue for bilateral “strategic partnership” with the most important EU 34. China not only picks its close allies inside the European Union to pursue its own. ‧ 國. 學. goals, but Beijing also singles out certain members who harmed Chinese interests. In. ‧. 2008, the year that China hosted the Summer Olympics, European leaders expressed their. sit. y. Nat. criticism over the human rights situation in China because of the Chinese crackdown on. io. er. Tibetan protesters. The leaders of several European nations, including the French president, Nicholas Sarkozy, who at the time held the presidency of the European Council,. al. n. v i n C h of human rightsU in China. The response from the expressed concern over the violations engchi 31. Pradeep Taneja, “China-Europe relations : The limits of strategic partnership,” International Politics,. (May-July 2010), 371-387. 32. David Shambaugh “China and Europe: The Emerging Axis”, Current History,. (September, 2004), 243-8, accessed July 1.2012 http://www.brookings.edu/views/articles/shambaugh/20040901.pdf., Frank Umbach, “EU’s links with China pose new threat to transatlantic relations,” European Affairs (Spring 4-6 2004), 1–8. 33. Gudrun Wacker, “Lifting the EU arms embargo against China U.S. and EU positions,” German Institute. for International and Security Studies, (February 2005), 13, accessed July 1. 2012, http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/2005_02Wkr_eu_embargo_ks.pdf. 34. Kay Möller, “Europe’s Policy: Neither Multipolar Nor Multilateral,” in: China’s Rise: The Return of. Geopolitics?, ed Gudrun Wacker (Berlin Stiftung für Wissenschaft und Politik 2006), 69.. 24.

(25) Chinese leadership was to cancel a planned EU-China summit in December 2008. 35 The criticism from European leaders ceased quickly and no additional measures (e.g. sanctions) were used. 36. 5. The “Big Three” implemented national-oriented policies towards China and neglected a coherent EU-approach.. The differences between the 27 Member States are the biggest obstacle to an. 政 治 大. improved EU China policy; no progress is possible unless the EU finds a way to deal with. 立. them. In principle, Germany, France and the UK have approved the objectives of a. ‧ 國. 學. common EU policy and the EU-China strategic partnership. In practice however, division and rivalries between the “Big Three” often undermine EU objectives. Political. ‧. disagreement and economic competition are the main reason for the internal division in. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. the EU.. Ch. engchi. 1.2 Literature Review and Methodology. i n U. v. China 37 is the world’s most populous nation and a growing world power. Among scholars of international affairs, there is little doubt that the “Rise of China” is the most. 35. Cameron Fraser (2009: The Development of EU-China Relations, European Studies, Volume 27, (2009),. 58. 36. Ibid., 60.. 37. In this paper the China will refer to the People’s Republic of China and the two self-governing special. administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau, excluding the Republic of China, Taiwan.. 25.

(26) remarkable event or development since the end of the Cold War. 38 Since then, China has experienced unprecedented economic growth which, arguably, has increased China’s influence in the international system. With double-digit growth rates, China’s market is now certainly one of the most important for manufacturers around the world. Moreover, in recent years Beijing has begun to strengthen its role as an important actor in international politics. Many scholars of International Relations argue that the unipolar international system, which was established after the end of the Cold War, has now been replaced by a multipolar system in which China is one of the most influential actors.39. 政 治 大 conduct efficient foreign policies. This fact applies as well to the European Union. The 立 These developments in international politics have changed the situation for other actors to. literature about China’s rise looking from a European perspective is a comparatively new. ‧ 國. 學. approach, the study of how the EU is dealing which Chinese rise remains limited.. ‧. Explaining European Union foreign policy is a great challenge to the main. sit. y. Nat. International Relations theories, because even the Union itself has no fully determined. io. er. status: is it a quasi-state or is it an international organization? Scholars who are analyzing the European Union are facing an even greater challenge, because foreign policy is. al. n. v i n traditionally defined by actionsCof a sovereign state. h e n g c h i UWhat, however, is the European Foreign policy? As Stummbaum writes: ”European Foreign Policy goes beyond the. collective foreign policies of its Member states and is more than simply the foreign policy. 38. For further reference, e.g. Nicholas D. Kristof, “The Rise of China,” Foreign Affairs Vol. 72, No. 5. (1993), 59-74, Richard Rosecrance, “Power and International Relations: The Rise of China and its Effects,” International Studies Perspectives (February 2006), 31-35, Bijian Zheng, “China's 'peaceful rise' to grate power status,” Foreign Affairs, (Number 5, Sept/Oct 2005), 18-24. 39. John G. Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West,” Foreign Affairs, 87:1, (Jan/Feb. 2008), 23-37.. 26.

(27) of the EU.”40 For the last decade, a wide range of different approaches have been introduced to analyze European foreign policy. 41 Part of the field is the study of the China policy of particular Member States. Several studies on this subject have been published. 42 However, the study of EU-China while examining the role of EU Member States remains rare. As Sandschneider states “little has been writing on the [coexisting] national foreign policies towards China”.. 43. This study will emphasize the role of the member states.. Especially the “Big Three” (Germany, France Great Britain” will be examined in depth.. 政 治 大 Krahmann argues that an analysis of EU foreign policy. Several scholars recommend multi-level approaches in order to understand the process of EU policy-making.. 立. 44. international actors within the European context 45. 學. ‧ 國. needs a multilevel approach to include the behavior of national, transnational and. ‧. The author writes that Foreign policy making “appears to be influenced by a broad. y. sit. 40. Nat. variety of public and private actors at the national, transnational and international May-Britt U. Stumbaum, “The EU and China. EU Decision-Making in Foreign and Security Policy. io. al. er. toward the People’s Republic of China", (Baden-Baden: Nomos 2009), 30. Ibid.. 42. n. v i n C h und sicherheitspolitische Kay Möller „Europa-China: Die ordnungse n g c h i U Dimension” (presentation fort the forum "Europa-China" in Munich, Germany), 20.11.1999., Christoph Neßhöver, „Deutsche und. 41. französische Chinapolitik 1989 bis 1997 im Vergleich,“ Asien Heft 73 (1999), 29-45., Markus Taube, „Entwicklung und Status quo der Wirtschaftsbeziehungen der Europäischen Union zur Volksrepublik China, in: Susanne Luther and Opitz, Peter, ed. Die Beziehungen der Volksrepublik China zu Westeuropa. Bilanz und Ausblick am Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts, Argumente und Materialien zum Zeitgeschehen, (Munich 2000), 47-66. 43. Eberhard Sandschneider “China’s Diplomatic Relations with the States of Europe,” China Quaterly, No.. 169, (2002), 33. 44. Elke Krahmann, “Multilevel Networks in European Foreign Policy”, (Aldershot: Ashgare, 2003), Sybille. Bauer and Eric Remacle. “Theory and Practice of Multi-Level Foreign Policy: The European Union’s Policy in the field of Arms Export Controls,” in B. Tonra and T. Christiansen, Rethinking European Foreign Policy, (Manchaster Manchester University Press), 2004. 45. Elke Krahmann, “Multilevel Networks in European Foreign Policy”, (Aldershot: Ashgare, 2003), 3.. 27.

(28) level of analysis.” 46 Krahmann emphasizes the growing diversity and interdependence of foreign policy actors.. 47. As other authors acknowledge since the late 1960s, an increasing. interdependence of nations has occurred. 48 This leads to an increasing number of governmental and non-governmental actors, who are participating on the international world state and shaping foreign policies as well. Moreover, differences between the EU Member States play a crucial role in the decision-making process. Government functions have been transferred to the international. 政 治 大 national state level up to the supranational “EU-level” level has accelerated this process. 立. level and deepening and strengthening these institutions. A power transformation from the 49. This development has led increasing differences between Member States. Bigger and. ‧ 國. 學. more powerful states have more national sovereignty compared to smaller ones. Bigger. ‧. states also don’t face the problem of more limited resources for participating on the. sit. y. Nat. supranational EU level and can more effectively influence the outcome of decision-. io. er. making processes. In his study of the foreign policy Krahmann includes the theories of rational choice and multi-level games in order to examine the different levels of decision-. al. n. v i n C hthe involved actors; making processes and understand however, to examine Brussels’ engchi U foreign policy towards the Peoples Republic, his approach needs to be altered.. Brian White argues that there are three types of activities in the European Foreign Policy system that are characterized by different core actors and different competences. 46. Ibid., 1.. 47. Ibid., 5-9.. 48. William Wallace and Helen Wallace, “Policy Making in the European Union”, 4th ed., (Oxford: Oxford. University Press 2000). 49. Burkard Eberlein and Abraham L. Newman, “Escaping the international governance dilemma?. Incorporated transgovernmental networks in the European Union,” Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, (vol. 21, no. 1, January 2008): 25–52.. 28.

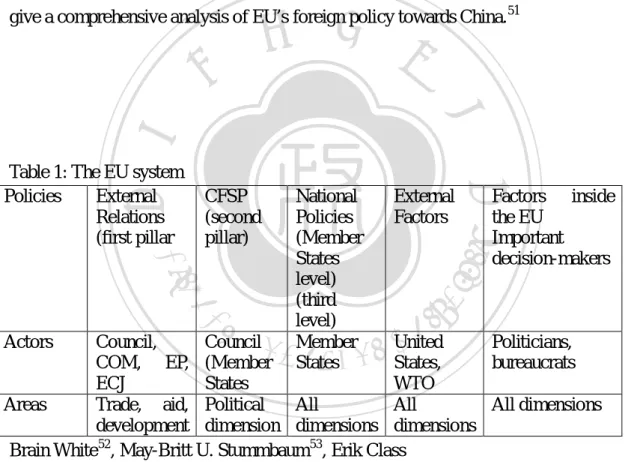

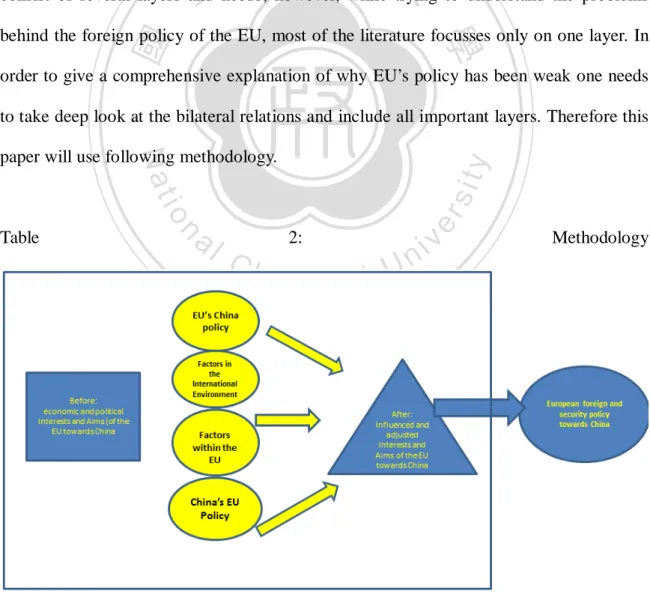

(29) within the decision making process. 50 In White’s analyses, the first type refers to external relations in the first pillar, with the European Community (EC) and thus the Commission (COM) as prime actor in the areas trade, aid, development. The second type concerns Common Foreign Policy as prime actor in the political dimension (EU Foreign Policy) and based on intergovernmental decision-making. The third includes national foreign policies of the Member States in all dimensions, with national governments as the core actor. However, Whites analysis does not include the factors “outside” the EU and important decision-making inside the EU. Thus, a new, extended model was created to. 政 治 大. give a comprehensive analysis of EU’s foreign policy towards China. 51. 立. n. Actors. Ch. Factors inside the EU Important decision-makers. y. External Factors. sit. io. al. National Policies (Member States level) (third level) Member States. er. CFSP (second pillar). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. Table 1: The EU system Policies External Relations (first pillar. iv n United U. Council, Council Politicians, COM, EP, (Member States, bureaucrats ECJ States WTO Areas Trade, aid, Political All All All dimensions development dimension dimensions dimensions Brain White 52, May-Britt U. Stummbaum 53, Erik Class. engchi. 50. Brian White, “The European challenge to foreign policy analysis,” European Journal of International Relations, (vol. 5, no.1 1999): 37-68., Walter Carlsnaes and Helene Sjursen et.al., Contemporary European Foreign Policy. (London: Sage Publishers 2004). 51 Ibid. 37-68. 52 Ibid. 39. 53 May-Britt U. Stumbaum, “The EU and China. EU Decision-Making in Foreign and Security Policy toward the People’s Republic of China", (Baden-Baden: Nomos 2009). 29.

(30) Moreover, the literature about EU China relations covers following topics. -. US influence and US EU-China relations. -. Economic and political Dimension of EU –China relations. -. EU Member States and EU-China relations. -. China’s EU-policy. -. EU-China relations and decision-making process inside process. However, there is little literature which takes a comprehensive study of the topic. Because. 政 治 大 consist of several layers and 立needs; however, while trying to understand the problems of the political system of the EU and its 27 national Member States, EU-China relations. ‧ 國. 學. behind the foreign policy of the EU, most of the literature focusses only on one layer. In order to give a comprehensive explanation of why EU’s policy has been weak one needs. ‧. to take deep look at the bilateral relations and include all important layers. Therefore this. Nat. sit. n. al. Ch. 2:. engchi. er. io. Table. y. paper will use following methodology.. i n U. v. Methodology. 30.

(31) This model describes this study’s methodology. As the model shows, this paper takes five layers “Factors in international environment”, “EU’s China policy”, “Factors within the EU”, and “China’s EU policy” into account and develops a comprehensive study of EUChina relations. Each dimension symbolizes an important part of the relations which influences the outcome of EU’s foreign policy. It is argued that only with taking those all of this dimensions into consideration, it is possible to fully examine the effectiveness of EU’s China policy.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 2. EU-China Relations. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat. This chapter will discuss EU-China relations. First the time period of 1949-2001 will be. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. briefly discussed. In the next chapter the relation between 2001 and 2009 will be. engchi. explained more thoroughly. Furthermore, EU’s foreign policy will be explained and the new term of “Unconditional Engagement will be discussed. The last part of this chapter will deal with China’s policy towards the EU.. 31.

(32) 2.1. EU-China Relations from 1949-2001. The basis of the relations between Europe and China was grounded on the “China Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement”. In the early 1985, the European Economic Community (EEC) 54 and the PRC signed it as the first agreement between each other. It still serves as the main legal framework between the sides. (The cooperation has been depended on in 1994 and 2002) 55. 政 治 大 The EEC condemned the response of the CCP and cancelled all high level contracts and 立. Bilateral relations were greatly disturbed by the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989.. ‧ 國. 學. loans. The EEC even planned a resolution at the United Nations and criticized China’s human rights violations. Furthermore, the EU started wide-range sanctions on China,. ‧. which were lifted later in 1992, and imposed an arms embargo (as well as the United. sit. y. Nat. States, Japan and Australia) which is still maintained.. io. al. er. With the economic success of the Four Asian Tiger States and China’s successful economic reforms, the EU, which was traditionally more westward looking, began to shift. n. v i n C hmore economical Urelations establish engchi. its focus and start to. with Asian countries. 56. European businessman were highly interested in China’s huge and yet undeveloped market. Thus, the European States signed its first Asian Strategy paper in 1994 and the. 54. The European Communities or European Community were were governed by the European Coal and. Steel Community (ECSC), the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom). They shared the same governing institutions from 1967 until they became they were integrated into the European Union. 55. See Appendix: “Chronology of EU-China relations.”. 56. Ezra F. Vogel, “The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia” (Cambridge, MA:. Harvard University Press, 1991).. 32.

(33) first China-Communication paper was issued in 1995. 57 The next step of a normalization of relations with the Middle Kingdom was reached with the agreement of the introduction of the specific dialogue on human rights issues in 1995. In the year of 1995 also the trade agreement “Multi-Fibre Arrangement” was signed. 58 Since then the EU has been overwhelmed by increasing number of Chinese textile products. Many European countries, especially Spain, France and Italy, who saw their domestic industries endangered and experienced rising trade deficits with China, successfully pressured the EU for the establishment of the EU-China High-Level Economic and Trade Dialogue. 政 治 大 which aroused worldwide attention. In many European countries the public responded 立. (HED) in 2007. 59 In 2008 EU-China relations were challenged by the Tibetan issue. sensitively to media reports about China’s bad human rights record. In 2008, many voices. ‧ 國. 學. demanded that the EU should boycott the Olympic Games opening ceremony. 60. ‧. 2008, the EU-China Summit scheduled to be held in Lyon during the French. sit. y. Nat. Presidency was cancelled by China due to the planned meeting between the French. io. n. al. er. President Sarkozy and the Dalai Lama.. 57. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. European Commission, “A long-termpolicy for China-Europe relations”, 1995, accessed 1. July 2012,. http://eeas.europa.eu/china/docs/com95_279_en.pdf. 58. O.G. Dayaratna-Banda and John Whalley, “After the Multifibre Arrangement, the China Containment Agreements,” Asia-Pacific Trade and Investment Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, ( June 2007), accessed July 1.2012. 59 Jing Men, “The EU-China Political Dialogue”, EU-China Observer (Issue 5, 2010): 5. 60 Philipp Lichterbeck, „Ein Jahr vor Olympia: Boykottaufrufe und Proteste,“ Tagesspiegel, (August 08.2007), accessed July 1.2012, http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/international/olympische-spiele-2008-ein-jahr-vorolympia-boykottaufrufe-und-proteste/1008650.html, Süddeutsche Zeitung „EUAußenkommissarin droht mit Boykott“, (March 03.2008), accessed July 2012, http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/olympische-spiele-in-peking-eu-aussenkommissarindroht-mit-boykott-1.269777. 33.

(34) 2.2. EU-China Relations from 2001-2009. Starting in the year of 2000, after a series of EU-China summits, the relations between the EU and China dramatically improved. In 2000, Zhu Rongji, the Prime Minister of the PRC, visited the Commission in Brussels and in 2001 China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). 61 Between 2000 and 2005 China-EU trade doubled and Europe became the largest destination for Chinese goods and China became Europe's biggest importer.. 政 治 大. In 2003 the European Commission wrote a new policy paper with the title "A. 立. maturing partnership - shared interests and challenges in the EU-China relations". 62 The. ‧ 國. 學. paper most importantly states "strategic partnership” is actively being emphasized within. ‧. the EU. Additionally, the paper stresses the importance of the EU to engage China through an upgraded political dialogue in the international community. 63 Since then, the. y. Nat. io. sit. relationship between the EU and China is classified as a strategic partnership. 64. n. al. er. In 2006 after further years of booming economic exchange and political. Ch. i n U. v. interactions, the European Commission issued another paper. It acknowledges China’s. engchi. economic rise and growing political importance and urges the EU to respond effectively to China’s renewed strength. It states that:. 61. WTO, “China and the WTO,” accessed July 1.2012,. http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/china_e.htm. 62. European Commission “EU-China relations: a maturing partnership,” (2003), accessed July 1.2012,. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2003:0533:FIN:EN:PDF. 63. Marcin Zaborowski, “EU-China Security Relations,” in Stanley Crossick and Etienne Reuter China-EU:. A Common Future (World Scientific Publishing Company, 2007), 45. 64. Ibid. 43.. 34.

(35) “China is one the EU’s most important partners. China’s re-emergence is a welcome phenomenon. But to respond positively and effectively, the EU must improve policy co-ordination at all levels, and ensure a focused single European voice on key issues. We have a strong and growing bilateral relationship. But we must continue building on this. The recommendations in this Communication, which the Council is invited to endorse and complement through Council Conclusions, represent a challenging agenda for the EU to do so, and the Partnership and Co-operation Agreement provides an important practical mechanism to move this agenda. 政 治 大 But with this comes an increase in responsibilities, and a need for openness which 立 forward. A closer, stronger strategic partnership is in the EU’s and China’s interests.. will require concerted action by both sides.” 65. ‧ 國. 學. This stage of the relations between the EU and China can be described as very good even. ‧. as a “honeymoon”. Romani Prodi, former president of the European Commission, even. sit. y. Nat. stated in 2004 "if it’s not a marriage, it is a very serious engagement". 66. io. er. However, the good relations or the "serious engagement" were disturbed by growing concerns of the EU concerning the development of the economic relations with. al. n. v i n C hand economic interactions China. The growing trade volume between the EU and China engchi U. could not prevent a political deterioration between the strategic partners. An economic imbalance and Chinese protectionist behavior have resulted in a series of criticism in Europe.. 65. Commission of the European Communities “EU – China: Closer partners, growing. responsibilities,” 2003, accessed July 1.2012, http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2003:0533:FIN:EN:PDF. 66. May-Britt U Stumbaum, "Risky Business? The EU, China and Dual-Use Technology", Occasional Paper, EU Institute for Security Studies: Paris No.80 (October 2009). 35.

(36) 2.3 EU’s Foreign Policy towards China. While analyzing the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy one has to face the problem that there is no “Common Strategy” towards China.. 67. It is rather a. “conglomerate of EU policies and national policies of the EU Member States. 68 As part of these efforts, the “The Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union” (CFSP) was established in 1993 in the Treaty of the European Union. 政 治 大 EU treaties. The CSFP is part of a three pillar system of the EU. 立. (the Treaty of Maastricht). Since then, the CFSP has been developed further in all later 69. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 67. Ibid., 48.. 68. Ibid., 48.. 69. This structure was introduced with the Treaty of Maastricht 1993, and was eventually abolished in 2009. after the signing of the Treaty of Lisbon.. 36.

(37) Table 3: Three pillar system of EU. Table 3: EU70, Erik Class. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. The first pillar “The European Communities” handles economic, social and environmental policies. The first pillar owns a legal personality, consisting of the. ‧. European Community(EC), the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC, until its. sit. y. Nat. expiry in 2002), and the European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM).. n. al. er. io. The second pillar “Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)” is responsible for. i n U. v. foreign policy and military matters. The third pillar “Justice and Home Affairs” aims for. Ch. engchi. cooperation in the fight against crime.. Given the nature of the European Union and its three main bodies, the European Council, the European Parliament, the European the European Commission and its currently 27 member states one can argue that the European Union and its foreign policy is distinct from any other international actor. However, due to the limited scope of the CFSP, when analyzing the EU’s foreign policy one needs to include all actions of its. 70 Europa.eu, “Pillars of the European Union,” accessed July 1.2012, http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/glossary/eu_pillars_en.htm.. 37.

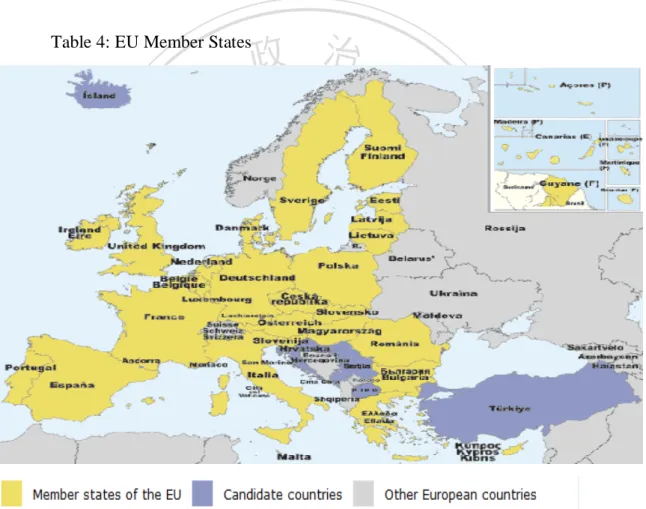

(38) Member States. As Hill argues, the European foreign policy is the sum of what the EU and its Member States do in International relations. 71 Thus the analyses must go beyond the “second pillar” or the CFSP. The European Foreign Policy is, arguably, not only heavily influenced by the “decisions and actions of core European states and their multilateral organization”, but also by external factors, such as states or organization. 72 External factors, such as other countries or international organization and powerful and influential leaders of EU Member States are factors that influence the EU’s foreign policy.. 政 治 大. Table 4: EU Member States. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Table 4 Europe EU, countries http://europa.eu/about-eu/countries/index_en.htm. 71. Christopher Hill, “European Foreign Policy: Power Bloc, Civilian Model – or Flop” in R. Rummel (ed.),. The Evolution of an International Actor, (Boulder Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1992): 84. 72. Elke Krahmann, “Multilevel Networks in European Foreign Policy”, (Aldershot: Ashgare, 2003).. 38.

(39) When analyzing the EU’s policy towards China, it must be kept in mind that the European Union consists of a large number of member states with different levels of economic development. Despite these differences, national strategy papers, key statements by officials, and bilateral agreements or specific development programmers on China, designed by individual EU Member States contain similar goals, such as increased economic openness or stronger environmental protection. These similarities are also the outcome of the EU-policymaking process. Member States can channel their national interests via committees working on EU Joint Statements or strategy papers on China.. 政 治 大 have agreed to transfer their bargaining power to the EU Commission. The complex 立. These official policy documents, however, need the consensus of all Member States who. process of EU policymaking is time-consuming, because the largest common. ‧ 國. 學. denominator between all involved decision-makers need to be found.. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.3.1 EU’s policy of Unconditional Engagement. In this chapter the term of “Unconditional Engagement” will be introduced.. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. Unconditional Engagement The term “unconditional engagement” was introduced by the. engchi. former advisor to US-president Ronald Reagan, Constantine C. Menges, when he described US foreign policy towards China. He wrote unconditional engagement “… is not isolation, but rather a policy of realistic engagement. This would use the enormous economic benefits accruing to China from trade with the US as an incentive for its acting peacefully and cooperatively internationally and it’s. 39.

(40) complying domestically with the human rights commitments China has freely assumed.” 73 Applying the term of unconditional engagement Fox and Godement criticize EU politicians that the theory that economic development and economic exchanges between the West and China will establish Western values such as democracy, rule of law and human rights in China. One of the main pillars of this approach was China’s entrance to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. The statement by Romano Prodi reflects the EU’s motivation in its political relations with China:. 政 治 大 “Europe needs to project its model of society into the wider world. We are not 立. simply here to defend our own interests: we have a unique historic experience to. ‧ 國. 學. offer…. We have forged a model of development and continental integration. ‧. based on the principles of democracy, freedom and solidarity—and it is a model. sit. y. Nat. that works.”74. io. er. Believing in this approach Brussels has been trying to persuade Beijing that the EU’s demands, such as rule of law or climate change, are also in the interests of China.. n. al. Ch. However, as Fox and Godement criticize,. engchi. i n U. v. “[that there] has been a steady increase in the number of objectives the EU formulates for its China policy; these are often changed as new topics acquire urgency. These objectives are seldom followed through. The EU has never carried. 73. Constantine C. Menges, “China: a Policy of Realistic Not Unconditional Engagement,” Hudson Institute,. http://www.hudson.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=publication_details&id=3175&pubType=RusChin. 74. Romano Prodi, ‘2000-2005: Shaping the New Europe’, speech to the European Parliament, Strasbourg,. Speech 00/41, (15 February 2000), 3, accessed 1.July http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=SPEECH/00/41&format=HTML&aged=1&langu age=EN&guiLanguage=en.. 40.

(41) out a proper evaluation of the success of its individual policies.” 75 Furthermore, Brussels is eager to integrate China into the international community so that not only cooperation between the two sides will be improved, but also the EU’s role in the world will be strengthened. To accomplish that goal, the EU invested for its first China National Indicative Programme (2002-2006) 250 million Euro 76 and spent in the following one (2007- 2010) 225 million Euro.77 However, China’s progress seems to be unsatisfactory. However, as many observers argue, the hopes of the EU have been disappointed.. 政 治 大 Rights and on Political and Civil Rights, the Chinese National People’s Congress has not 立. Although China has signed both of the UN Covenants on Economic, Social and Cultural. ratified the second covenant eleven years after its signature. Furthermore, since China has. ‧ 國. 學. become a WTO member the reform has been slowed down or even stopped.. 78. The case. ‧. of WTO also shows that the hopes of the EU have been disappointed:. sit. y. Nat. “Examples of Europe’s failure to mould China in its own image are legion.. io. er. Political liberalization seems to have stalled, or even reversed: China has tightened restrictions against NGOs, stepped up pressure on dissidents, and. al. n. v i n CPower John Fox and François Godement, “A of EU-China h e Audit i URelations”, European h n c g Council on Foreign Relations, (1), accessed July 1. 2012, 75. http://ecfr.3cdn.net/532cd91d0b5c9699ad_ozm6b9bz4.pdf. 76. European Commission, “European Council, National Indicative Programme 2005-2006 – China ” (2005),. accessed July 1.2012,http://eeas.europa.eu/china/csp/05_06_nip_en.pdf. 77. European Commission, “China Strategy Paper, 2007-2013,” (2006), accessed July 1 2012,. http://eeas.europa.eu/china/csp/07_13_en.pdf. 78. Hanns Günther Hilpert, „Chinas globale wirtschaftliche Herausforderung Für eine kohärente. Außenwirtschaftspolitik Europas,“ (2010): accessed 1 July 2012,http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2010_S29_hlp_ks.pdf, Margott Schüller, „The EU’s Policy on China on Economic Issues: Between Disillusion and Dialogue,” in American and European Relations with China, Advancing Common Agendas. German Institute for International and Security Affairs, David Shambaugh and Gudrun Wacker, ed., 65-78, (2008), accessed 1 July 2012, http://www.swpberlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2008_RP03_shambaugh_wkr_ks.pdf.. 41.

(42) stopped or rolled back local electoral reforms. At the UN, Beijing has built an increasingly solid coalition of general assembly votes, often mobilized in opposition to EU values such as the defence of human rights.” 79 Observers criticize that the policy of unconditional engagement is too convenient for EU policy-makers, as there is too less political will for EU leaders to push Beijing hard enough on political values. 80 One can take the EU-China Human Rights Dialogue as an example. The dialogue was introduced in 1995 and is considered a soft, low-profile approach of influencing. 政 治 大 century of national humiliation by Western powers into consideration. However, after 立 China. It tries to take China’s dignity and values and the countries sensitivity after a. only ten years the EU already expressed for the first time its dissatisfaction with the. ‧ 國. 學. results of that softer approach, and openly questioned the usefulness and effectiveness of. ‧. the EU-China Human Rights Dialogue. EU documents from 2006 indicate that the EU’s. sit. y. Nat. expectations are not being fulfilled.. io. er. The organization “Human Rights Watch” criticizes that the EU-China Human Rights dialogue has "consistently failed" to produce substantive results because it is not. al. n. v i n linked to other issues such as C trade, investment andUthe environment. hengchi. 81. The advocacy. director of Human Rights Watch, Sophie Richardson, said that. "for too long, the EU-China human rights dialogue has been a toothless talk shop which has failed to meaningfully address the Chinese government's poor record on human 79. John Fox and François Godement, “A Power Audit of EU-China Relations”, European. Council on Foreign Relations, (20), accessed, (April 1.2009), July 1. 2012, http://ecfr.3cdn.net/532cd91d0b5c9699ad_ozm6b9bz4.pdf. Mikael.Mattlin, “A Normative EU Policy Towards China: Mission Impossible?” (Finland: Finnish Institute for International Affairs), September 2010. 80. Ibid.. 81. Human Rights Watch, “EU: China Summit Needs Rights Focus,” (May 19, 2009), accessed 1 July 2012,. http://www.hrw.org/news/2009/05/19/eu-china-summit-needs-rights-focus.. 42.

數據

相關文件

It is l ocated on the China-Pakistan border between Baltistan and the Xinjiang, China....

The importation should conform to the regulations of "Consolidated List of Conditional Import Items of Mainland China Origin and Regulations Governing Import of Mainland

This shows that, up until the mid to late Tang Dynasty, objects made of glass and crystal still were both called liuli, whereas the term poli was used to refer to

z 可規劃邏輯區塊 (programmable logic blocks) z 可規劃內部連接

Late Qing Master Taixu, recognized as the leader of Buddhist reform movement, and several Buddhist intellectuals collaborated to remodel and revive Buddhist

FPGA –現場可規劃邏輯陣列 (field- programmable

FPGA –現場可規劃邏輯陣列 (field- programmable

With regard to spending structure, visitors from Mainland China spent 60% of the per-capita spending on shopping, whereas those from Hong Kong and Taiwan, China spent 79% and 74% of