中國在中亞的能源安全政策以及美國在其中扮演的角色 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 中國在中東的能源安全政策以及美國在其中扮演的角色 China’s Energy Security Policy in the Greater Middle East and Its Relations with the United States. Student: Serafettin Yilmaz 姚仕帆 Advisor: Dr. Liu Fu-kuo 國劉復. Dissertation Submitted to International Doctoral Program in Asia-Pacific Studies National Chengchi University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. March 2014.

(3) Summary Global energy politics has undergone a structural change in recent years. In general terms, production and consumption centers have been realigned along with changes in the cores of manufacturing and economic development. Energy consumption has become denser in East Asia whereas the former consumption center, North America, has achieved greater independency thanks to new technologies, stagnant or declining consumption and further shift toward service-based and less energy-intensive industries. The center of global energy production, in the meanwhile, remains to be the Middle East (ME), specifically the Persian Gulf, however, its dominant status has been undermined recently with decreasing energy dependency of the United States. In this structural shift of energy geopolitics, thus, China and the U.S. have witnessed their positions vis-à-vis the Middle East began to shift. Essentially, this research offers critical policy analysis in a comparative setting. It attempts to empirically evaluate the Chinese and U.S. foreign policy strategies in the Greater Middle East and investigate how they relate to each other. From this analysis, it hopes to reach conclusions that will shed light on the China-U.S. relationship in the Middle East. Then, drawing on the conclusions reached, it offers policy recommendations on how to prevent a great power confrontation in the Middle East in order to better manage the regional peace, considering at once Beijing’s energy and Washington’s geopolitical interests. Thus, this it offers a ‘quantitative first, qualitative primary’ perspective. Qualitatively, comprehensive policy investigation, historical narrative and in-depth interviews assist the research. Quantitatively, extensive data on energy and energy related economic and military activity are analyzed. In a nutshell, this research is comparative in its scope, focusing on China’s relations with key regional energy producers in the Greater Middle East. By incorporating a critical analysis of the recent geopolitical developments, it puts China’s growing energy dependency and engagement in the larger context of China-U.S. competition and cooperation for greater influence in the region and speculates on how this would impact the regional and global peace. More specifically, this research contributes to the existing literature by offering a comprehensive analysis on China’s energy security policy in the Middle East.. ii.

(4) Acknowledgements As famously put, “no man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Throughout the two and a half years that I have been a student of IDAS, I received numerous invaluable help from teachers, officials and friends. First and foremost, I am indebted to my advisor, Dr. Liu Fu-kuo, for his patience, incisive feedback, and friendship. Dr. Liu has not only been a great teacher to me, but also a mentor who enabled me to venture out a number of academic pursuits beyond the classroom. His incredibly solid and rich international horizon and knowledge have given me the opportunity to better understand the political- security environment in the Asia-Pacific. I was extremely also lucky to have an outstanding committee, including my supervisor in Academia Sinica, Dr. Lin Cheng-yi. I am thankful to the rest of my committee, Dr. Chang Chung-young, Dr. Lee Ming and Dr. Wang Kaocheng whose constructive help and endeavor to respond to my frequent calls and messages have definitely facilitated the process of the research. I should acknowledge with appreciation that my committee members have patiently gone through and revised my paper and made numerous invaluable corrections and suggestions. Without their contribution and advice, I could not have come this far. Doubtlessly, I further benefitted greatly from a number of professors inside and outside the department and received constructive advice, including the former and current IDAS directors, Dr. Berman and Dr. Holm and former IMAS director, Dr. Kuan. Furthermore, I would say my dissertation process would have been much less efficient had I not had very precious help and support from my dear friends Angel at the IDAS office, Vivian at the MCSS and, Angela, former IMAS secretary. And surely, all the friends, old and new, have been an inspiration and encouragement to move forward at times of crisis and joy alike. In this respect, I feel obliged to mention my good friend Janet and her continuous multilateral support. In the workshops that she singlehandedly brought forth was my dissertation research further tested, purged and sharpened. All that said, let there be no doubt, whatever shortcomings this dissertation may have are of my own.. iii.

(5) Contents List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ vi List of Figures .......................................................................................................................vii List of Maps......................................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Literature Review .................................................................................................................................... 13 Power Shift Theories ........................................................................................................................... 13 Energy Security and Middle East ........................................................................................................ 24 Methodology and Data Analysis ............................................................................................................. 34 Conceptualization and Operationalization ............................................................................................. 39 Data Collection, Data Analysis and Data Sources ................................................................................... 41. Chapter 2: China’s Energy security: Structure and Dynamics ................................................ 43 The Structure .......................................................................................................................................... 43 National Oil Companies (NOCs) .......................................................................................................... 53 Strategic Petroleum Reserves (SPR) and Energy Efficiency ................................................................ 57 China’s Overland Energy Routes: Pipelines ........................................................................................ 59 Defining Energy Security ......................................................................................................................... 64 How China Securitizes Energy? ............................................................................................................... 69. Chapter 3: China in the Middle East ..................................................................................... 78 China’s Political Presence in the Middle East ......................................................................................... 78 China’s Economic Presence in the Middle East ...................................................................................... 82 China’s Energy Security Policy in the Middle East .................................................................................. 86 Case 1: The Partition of Sudan and China-Sudan Energy Relations: China’s Growing Clout .................. 92 China’s Multi-Track Diplomacy in Sudan ............................................................................................ 94 Sudan: History, Conflict and Partition................................................................................................. 96 China-Sudan Relations: Before and After Partition ............................................................................ 99 China’s multi-track diplomacy strategy ............................................................................................ 102 US Reaction to China’s Sudan Policy ................................................................................................. 104 Conclusion of the Case: Implications for China-US Relations ........................................................... 106. Chapter 4: US in the Middle East........................................................................................ 108 iv.

(6) US Political and Military Presence in the Middle East .......................................................................... 108 US and Middle East Energy ................................................................................................................... 114 Case 2: The Iranian Nuclear Dilemma: Comparing Chinese and US Strategy ....................................... 121 Iran’s Nuclear Energy Program: Chinese and US Strategies ............................................................. 123 US: From Friend to Foe ..................................................................................................................... 125 China: An Act of Strategic Balancing ................................................................................................. 128 The Iranian Nuclear Energy Dilemma ............................................................................................... 133 Conclusion of the Case: Implications for China-US Relations ........................................................... 135. Chapter 5: Energy and Maritime Security: The Development of the Chinese Navy (Case 3) . 138 The Mahanian Theory of Sea Power: How Beijing Reads It? ............................................................ 141 The Energy Connection: China in the Persian Gulf ........................................................................... 147 Doctrinal and Technological Transition of the Chinese Navy ........................................................... 152 Protection of the Sea Lanes and Chokepoints: China’s Naval Strategy ............................................ 158 Implications for China-US Relations.................................................................................................. 161. Chapter 6: Analysis: The US-China Strategic Competition in the Middle East ...................... 164 Chapter 7: Conclusion ........................................................................................................ 188 Bibliography ...................................................................................................................... 198 Appendix 1: Data Type and Sources ................................................................................... 220 Appendix 2: Abbreviations ................................................................................................ 222 Appendix 3: List of Interviewees ........................................................................................ 223. v.

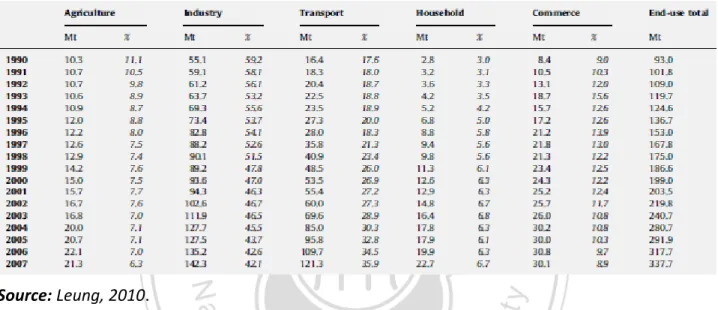

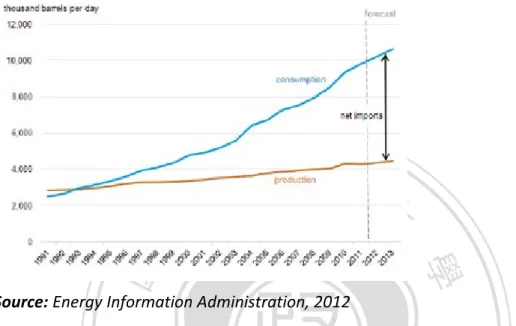

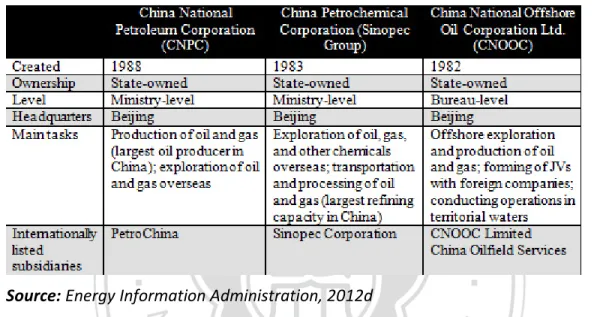

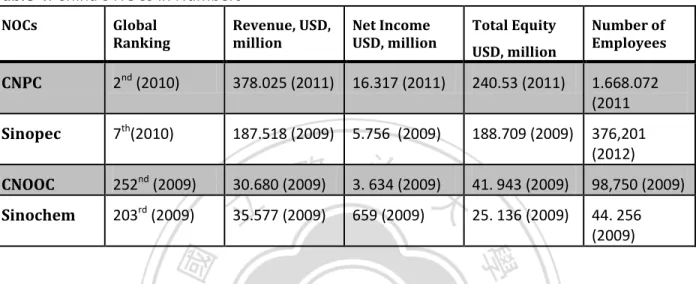

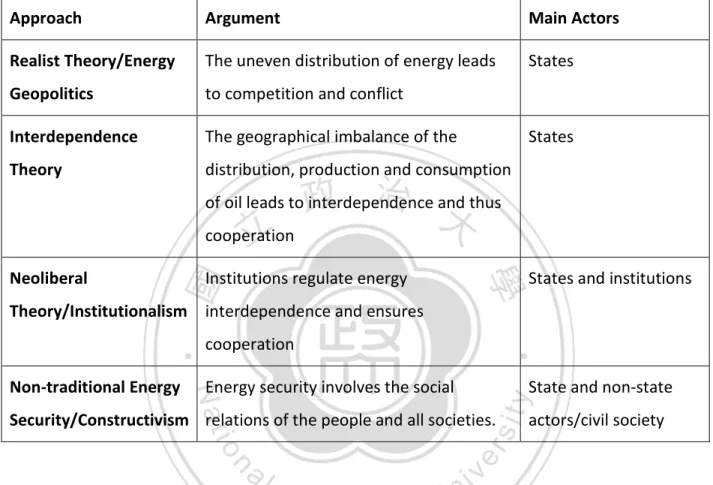

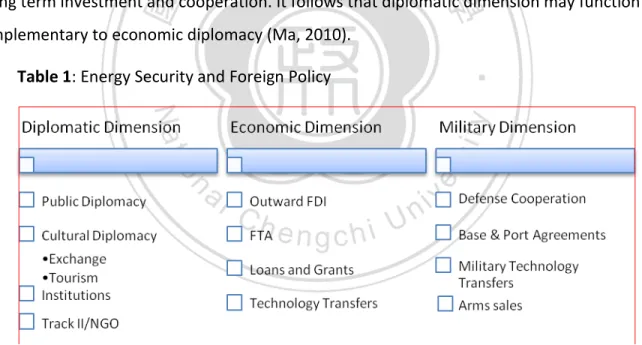

(7) List of Tables Table 1: Energy Security and Foreign Policy……………………………………………………………………..……………………35 Table 2: China’s end-use consumption of oil, 1990-1997…………………………………………………………..………….47 Table 3: China’s Main National Oil Companies………………………………………………………………..…….….……….….54 Table 4: China’s NOCs in Numbers…………………………………………………………………………..…….…………….………..56 Table 5: Major Theoretical Approaches to Energy Security…………………………………..………..………….………….67 Table 6: China-US Policy Discord in the Middle East………………………………………..……….…….……….…………..184. vi.

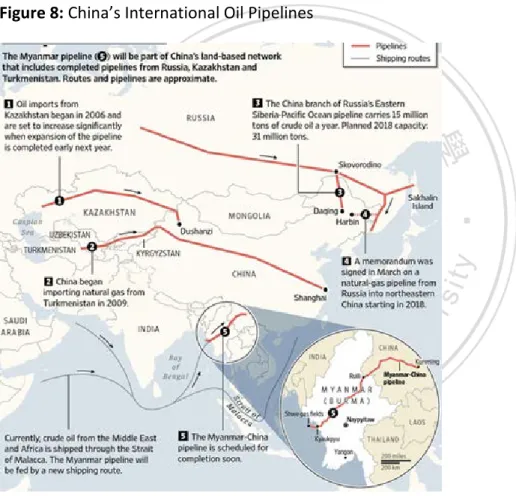

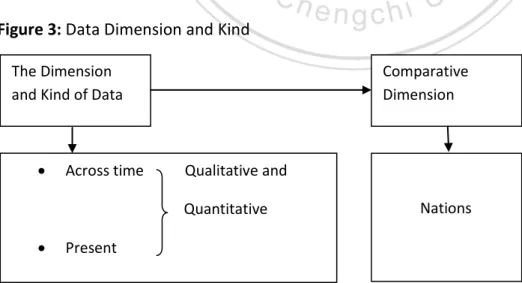

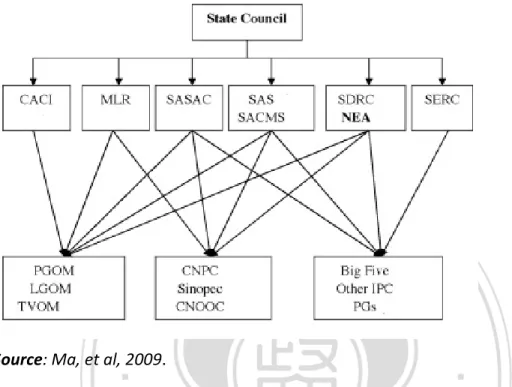

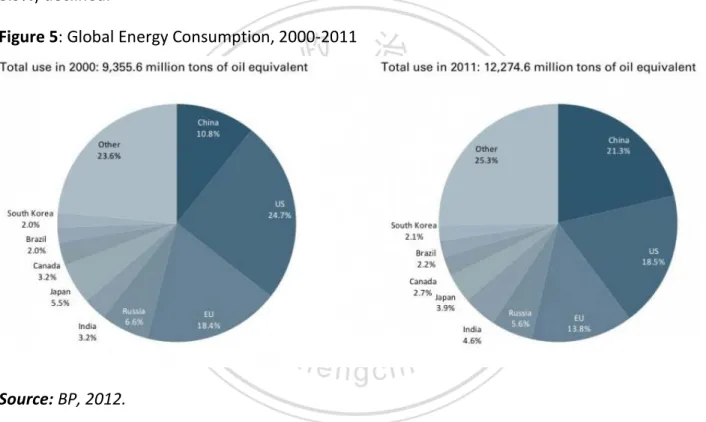

(8) List of Figures Figure 1: China-US Strategic Competition…………………………………………………………………….…..…………………..10 Figure 2: The process of Inductive Measurement…………………………………………………..…………….……………....40 Figure 3: Data Dimension and Kind………………………………………………………………………….…………………………….40 Figure 4: Government Structure for Energy Sector as Set up in 1998……………………….………………..………...44 Figure 5: Global Energy Consumption, 2000-2011……………………………………………………………….……..……..…46 Figure 6: China’s Domestic Oil Production and Consumption, 1990-2013………………….………………..……….50 Figure 7: China's Oil Supply Balance……………………………………………………………………………….…………………….52 Figure 8: China’s International Oil Pipelines……………………………………………………………………...……………….…61 Figure 9: China’s State of Energy Supply Security…………………………………………….……………………..…………….70 Figure 10: Systems-based Approach………………………………………………………………….…..…………………………..…95 Figure 11: Estimated Energy Production of US, Russia and Saudi Arabia……………………………………..……..117 Figure 12: Percentage of US Oil Import by Region in 2012…………………………………………………..……………..119 Figure 13: North America Total Liquids Supply Projections……………………………………………………..………….120 Figure 14: Middle East Oil Export by Destination…………………………………………………………..…………………...174 Figure 15: Net oil and Gas Dependency in Selected Countries……………………………………..……………………..174 Figure 16: National Power Index -- Base Case…………………………………………………………..………………………...179 Figure 17: Four-Component Power Forecast………………………………………………………….……………………….…..180. vii.

(9) List of Maps Map 1: Detailed Map of the Greater Middle East……………………………………………………………………………………3 Map 2: China’s Major Overland and Off-shore Oil Reserves…………………………………………………………………51 Map 3: World Oil Transit Chokepoints…………………………………………………………………..………………………………74 Map 4: Oil Industry in Sudan and South Sudan…………………………………………………………………………………..…98. viii.

(10) Chapter 1: Introduction Global energy politics has undergone a number of changes in recent years. In most general terms, production and consumption centers have been realigned along with industrial development and economic shifts. Energy consumption has become denser in East Asia whereas the former consumption center, North America, has achieved greater independency thanks to new technology, stagnant or declining consumption and further shift toward servicebased and less energy-intensive industries. The center of global energy production, in the meanwhile, remains to be the Middle East (ME), specifically the Persian Gulf, however, its dominant status has been undermined recently with decreasing dependency of the United States on Middle Eastern energy. In this structural shift of energy geopolitics, thus, China and the US have witnessed their positions vis-à-vis the Middle East and each other shift dramatically. More specifically, two recent developments are likely to change the way US - China energy geopolitics in the Middle East is debated in the contemporary scholarship: First of all, over the past decade a major shift altered the dynamics of these two countries’ energy dependency. China’s import from the Middle East has increased exponentially, while the US import dependency has decreased from its peak of 60% in the mid-2000s to 40%. According to various projections, this inverse relationship will continue for the foreseeable future and in a decade or so the US will achieve near-zero dependency on the Middle Eastern oil whereas China’s dependency will reach over 80% of its total import (IAE, 2012b). This unique development will unavoidably have implications for the US-China relations, forcing them to reconsider their long-held regional policies. Furthermore, due to divergent policy motivations, China and US see their interests clash more often since shifting positions in the two countries’ respective strategies create friction. Second, the past two decades has seen a phenomenal rise of China in economic, technological and military power. On the other hand, the United States has endured two costly wars and a deep financial crisis, which took a heavy toll on the country’s economic and political leadership, leading to a decline in relative strength. Numerous studies began to point out China’s overtaking of the US in, first, economic and technological development, and then, in 1.

(11) military power in the coming decades.1 Hence, it is hypothesized that a series of policy disagreements in the Greater Middle East due to the changing regional energy dynamics of China and the US, and China’s growing national power and US’ relative decline might lead to a destructive competition between Beijing and Washington in the Middle East and beyond if the two countries fail to bridge their differences and accommodate each other’s national geopolitical (including energy) security needs. 2 To categorize the nature of US-China relations in the Middle East, this dissertation offers the term “policy discord” and defines it as the existence of a strategic chasm in the foreign policy of two competing great powers. In this sense, discord means a divergence of the national strategies of two states in certain areas such as nuclear policy (US-Iran), energy policy (ChinaU.S), or human rights (EU-Sudan). The China-US policy discord in the Middle East means a clash of national strategies of the two countries with extensive national power and capacity to effectively confront each other. If the differences are not bridged but further widened, the discord would lead to destructive competition. Although the US still maintains advantage over China in terms of military, China is now more able to rival the US with its greater economic and technological capability (OECD, 2013). Thus, China’s growing power to compete with the US and its dependency on the hydrocarbon 1. Although the reputation of forecasting is highly disputed even for the short term, national development strategies do need to consider future trends in the global environment no matter how difficult it may be. This research recognizes that discontinuities and shocks, by their very nature, are difficult to anticipate. Ideas, technologies, events, and individual actions can sometimes snowball into powerful forces of change. Any projections, for that matter, needs to be considered with this fact in mind. For forecasts on China-US power balance, see, “When will China overtake America?” The Economist, December, 16th 2010; “What Milestone Will China Achieve Next?” US Global Investors, February 2, 2012; “China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative High-Income Society,” The Washington Post, <http://www.washingtonpost.com/r/20102019/WashingtonPost/2012/02/27/Foreign/Graphics/New-China-2030-overview.pdf>; “World Development Indicators,” World Bank, Washington, DC: September, 2011. 2 The term Greater (or, Extended) Middle East was coined by the Bush administration in the early 2000s. Under this definition, about 20 countries across North Africa and Central Asia are included in the traditional list of Middle East countries. Hence, the Greater Middle East “stretches from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean and the Arab Middle East through the Persian Gulf area to embrace Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and, now, at its furthest extreme, India.” In this study, the terms “Middle East” and “Greater/Broader/Extended Middle East” are used interchangeably although the unit of analysis involves countries such as Sudan, which is a country in North Africa, that are listed under the Greater Middle East. See Map 1. For an historical overview, see Fradk, 2005. “The ‘Greater’ Middle East: The New Geopolitical Environment and Its Implications for Obama Administration Policies,” Hudson Institute (Date not indicated); Jeremy M. Sharp, “The Broader Middle East and North Africa Initiative: An Overview,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report for Congress, 2005. 2.

(12) resources from the ME reinforce the existing strategic discord. This study, in this regard, offers a comprehensive analysis on the China-US relations in the Middle East from the comparative perspective of China’s energy-led and US’ security-led Middle East policy and explores the measures that would help the two countries to manage their differences to enable peaceful coexistence and, thus, regional stability. To this end, this research aims to investigate the nature of China-US interaction in the Middle East and whether the existing policy discord is sustainable. Map 1: Detailed Map of the Greater Middle East. In this research certain concepts are used to explain China-US relations in the ME. Of the concepts used, national power is the most frequently visited 3 while it is at the same time one of the less agreed upon among the scholarship (Young, 2006: 5-7). Nevertheless, this research defines national power as the sum of a country’s hard power capabilities based on economic 3. Although international relations experts hold major differences of opinion regarding the fundamental components of national power, they seem to have reached consensus on dividing those components into ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ power. Later on, smart power (a combination of hard and soft power) has been added to the classification. 3.

(13) and technological development. Doubtlessly, one can add to or extract from this definition certain components based on one’s level and purpose of analysis. Drawing from various studies by Organski, Kugler and others, this study identifies four components that together compose of a country’s hard power: GDP, population, technology and military capacity (Organski, 1958 and Organski and Kugler, 1980). Here, the indicators of soft power are excluded because, energy security as it is today is a factor of hard power in which ideational components that relate to soft power(such as culture, citizen diplomacy, education, media, and NGO activity) play little role. Hence, growing national power and capacity, in the case of China, on the one hand, enables, and on the other, obliges Beijing to seek energy security in the Middle East. Energy security has appeared on Beijing’s foreign policy agenda for the second time when the nation lost its status as energy independent in the early 1990s (1993, to be exact) after a three-decade of self-sufficiency. China’s booming heavy industry sector, 4 its large commercial export sector, and the rapidly expanding middle class that purchase two times more cars monthly than that of the US have led to an exponential increase in the demand for oil with no sign of easing in the foreseeable future. As domestic production failed to match civilian and industrial consumption, the Chinese government has come to see energy dependency as a national security issue to be tackled with a wide array of national and international policy instruments (Cornelius and Story, 2007). For example, domestically, Beijing bolstered exploration activities, set up more stringent energy efficiency standards for industrial and civilian use and, starting from 2007, began to build a strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) to eventually have a 90-day supply capacity by 2020 and invested in alternative energy resources such as wind, hydro and solar. Internationally, Beijing devised a go-abroad policy in the early 2000s to enable its national oil companies (NOCs) to gain long-term control over natural resources in foreign countries through government-to-government agreements and equity oil concessions. 5 However, as it engages the international energy market, China’s energy policy has. 4. Indeed, “the share of heavy industry in China’s economy has steadily increased since the early 2000s. China now produces more than half of the world’s steel and cement output, and the growth of heavy industry is one of the major factors responsible for China’s rising energy consumption.” See, Yang, 2012. 5 As of 2010, Chinese NOCs had equity stakes in production in 20 countries and the NOCs’ overseas equity shares reached 1.36 mb/d, nearly one-third of China’s net imports in 2009. See, Julie Jiang and Jonathan Sinton, Overseas 4.

(14) elicited criticism in Washington which sees it as being run by the state and securitized – a clear distinction from the Western market-led approach. Nevertheless, judging by historical precedence, Beijing’s state-driven energy security strategy has striking similarities with that which was embraced by the Western governments at the time of their industrialization throughout the 19th century. To be sure, going abroad strategy was first adopted by the US government from the mid-1930s until the late 1970s. Under the scheme, large private oil firms received help from the state to secure long-term concessions from foreign governments under lucrative terms. To be able to compete with the Europeans that had an advantage over the US oil companies because of their early arrival into the global energy scene, particularly the ME, the US government provided active support through economic instruments such as tax credits and subsidies for overseas investment. Indeed, “In a material sense, oil was at the center of the redistributive system of American hegemony. In Saudi Arabia, and to a lesser extent in other areas of the Persian Gulf, major US oil companies benefited from special relationships between the United States and the producing countries and from the protection and support of the American government” (Keohane 1984: 139). Also, when deemed necessary, US governments mobilized the State Department and US military to protect its national energy interests (Lei and Yen, 2007). Thus, China’s modern day state-led going-abroad strategy has some similarities with that of the US from the 1930s onwards with the exception that currently the Chinese military (PLA) does not play an active role (although its role as a provider of sea lane security has been growing) in national energy policy unlike that of the symbiotic relationship between the US military and the energy industry in the early and mid-20th century. In its current form, China’s energy strategy remains much less military-oriented as it currently lacks a strong PLA backing although it may not be the case in the medium to long-run as the Chinese Navy achieves greater force projection capabilities. However, as opposed to Western companies (First British and other major European firms in the beginning of the 20th century and then US firms from the mid-1930s), which investments by Chinese National Oil Companies: Assessing the Drivers and Impacts, Information Paper Prepared for the Standing Group for Global Energy Dialogue of the International Energy Agency, Paris, February 2011. 5.

(15) managed to forge political and economic relationships with key producing countries in the Middle East and elsewhere as far as nearly a century ago, today Chinese companies are facing a less promising international energy environment. The PRC government realizes that the US and European companies have an almost five-decade advantage over China’s new comers. Therefore China’s NOCs will hardly enjoy equal opportunity in the markets long appropriated by Western multinationals. Hence, Beijing finds itself in a less than optimum energy security environment constrained by its lack of historical and geopolitical depth in the Middle East (Beng and Li, 2005). Accordingly, China’s contemporary energy policy is composed of three interrelated strategies. The first strategy involves seeking oil agreements in neighboring countries such as Russia, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan and building overland routes (highway, railway tracks and pipelines) for the delivery of hydrocarbon resources. The second strategy requires China to go further and engage the particular countries in the Extended Middle East and Latin America where the energy interests of Western companies are not as strongly entrenched as in other places. The final strategy includes deals with countries such as Iran, Sudan and Syria that have been marginalized and reduced to pariah states through sanctions and other means by the West and; therefore, are not available for US and Europe investment. It is seen from the three strategies that as one goes down the list of strategies, the security implications of doing business in energy increase considerably (Calabrase, 1998; Lee, 2013; Yao, 2007). In addition to economics, politically and militarily, too, Western states, particularly the US, have a strong footing in the energy-rich regions, especially the Middle East. The US has a long-developed comprehensive relationship with oil-producing countries and, in addition to a host of military bases across the region, operates a naval base in Bahrain, home to the US Naval Forces Central Command and the Fifth Fleet, which is responsible for an area stretching across the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and the Arabian Sea as far south as Kenya in East Africa. Also, when necessary, the US has the capacity to effectively intervene in the countries in the region, using the available political, economic and military instruments to achieve its objectives (Harris, 2010). Indeed, especially militarily, the United States can seriously disrupt China’s existing oil interests in the region. 6.

(16) Iran and Sudan are two cases in which the United States and its allies have negatively affected Beijing’s energy prospects for the past two decades. Iran has constantly been threatened with military action and also heavily sanctioned due to its contentious nuclear energy program although currently there is a chance for a lengthy (and never guaranteed) normalization process. US pressure not only slowed down the investment by the Chinese NOCs in the country’s under-invested energy sector, it also forced Beijing to refrain from signing new equity agreements to develop Iran’s vast untapped fields (Downs and Maloney, 2011; Zahirinejad and Vrushal, 2010). Similarly, international pressure on the Sudanese government led to the partition in 2011. After the split, Khartoum, a close energy partner for Beijing, lost control over vast energy fields in the South, which accounted for more than three quarters of oil produced in the pre-partition era Sudan. Also, China suffered from the pre and post-partition environment especially in 2011 and 2012 because of the South’s perception of China as a longtime ally of the North. Recent developments in the break-away South Sudan have further endangered China’s energy prospects. Nonetheless, Beijing has few options other than seek its energy fortune in the Extended Middle East. Now world’s largest energy consumer since 2010 and the largest importer of crude oil since November 2013, China is highly reliant on the Middle East to meet its energy needs. The region accounts for over 50% of the nation’s total crude oil imports. In 2012, out of the seven biggest providers of oil, five were located in the Middle East. It is estimated that by 2015, the share of Middle Eastern oil in China’s total import will climb to 70% (Ma, et al., 2012; IEA, 2011a). Hence, although certain security issues in the oil producing countries (such as socio political instability or foreign intervention) may seriously disrupt or even fully stop China’s exploration and production activities, Beijing needs to maintain its presence in these geographies and seek further strategic depth. Threats to China’s energy security are not limited to those that it may face in exploring and extracting foreign oil but also in transporting it. Now maritime security occupies even a larger space in Beijing’s strategic calculations as country’s trade, including trade in energy, is overwhelmingly carried out by sea routes. At the moment, US retains full naval control over strategic chokepoints in the Persian Gulf and the Malacca Strait along which China’s oil imports 7.

(17) from the ME flow (Newmyer, 2009: 218). The Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf serves as the exit gate for the shipping of goods and commodities from the region. Most of the crude oil exported from Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait and Iraq goes through this four-mile wide channel between Oman and Iran. Needless to say that more than two third of this oil is shipped to East Asia, primarily, to China, Japan, India and South Korea. Similarly, the Strait of Malacca links the Indian and Pacific Oceans and, with an estimated 15.2 million b/d flow in 2011, it connects Middle Eastern oil to the Asian markets (EIA, 2013a&c). Hence, in the face of hard realities such as the strong military presence of the US in the Middle East and East Asia, its ability to intervene and disrupt international oil flow, the standoff with Iran over its nuclear energy policy, the ongoing Syrian crisis, the popular Arab dissent across the Middle East as well as other non-traditional security threats such as piracy and terrorism, China’s energy policy occupies a central place in the nation’s strategic calculations and is inadvertently securitized. Therefore, although it is not as comprehensive as that of the US and much less militarized, Chinese involvement in the Middle East has become decidedly multidimensional, consisting of diplomatic, economic and military dynamics. Placing each level of energy security (access, exploration, extraction, transportation, and processing) at the center of its Middle East policy, as this research has found out, Beijing has taken economic, political and military steps involving various combinations of these dynamics. As China engages the energy rich region in more comprehensive way, its policies eventually come into collision with those of the US on economic, political and military fronts. It appears that two developments are becoming manifest in the China-US relations in the Middle East. First, the US has been reducing its energy dependency on the Middle East due to growing domestic production that is made possible with new extraction techniques, higher efficiency, growth in services-based industries and stagnant consumption (Clapper, 2012; Eland, 2011). This offers Washington a greater space in the region because of less constraint on its. 8.

(18) foreign policy making that energy dependency normally brings about. 6 United States’ warm embrace of the Arab Spring is one of the consequences of such strategic breadth. Second, at the time when the US is adopting a more or less anti-status quo posture in the Middle East as is exemplified by its nation-building efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, China, in line with its growing power and national capability, is becoming more assertive and pursue its energy interests with less consideration to the US geopolitical concerns while pushing for incremental and internallydriven change in the Middle East. Such conflict of interest would be even more pronounced if a major war in the Middle East pushed the sides deeper into their political and ideological quarters. Unless proper policies are not taken, China’s growing energy dependency and the existing policy discord between the US and China may lead to a deeper competition and confrontation even in the absence of a major regional crisis in the region (Chen, 2008). Building on the relationship described above, the main argument of this research is that the China-US policy discord has led to a strategic competition in the Middle East. Unless proper policy measures are taken, this competition may lead to a destructive power struggle in the Middle East, threatening regional and global peace. It is hypothesized that the underlying reason for this policy discord is the radically different nature of the two countries’ Middle East policies: Whereas China’s conduct in the region is dominantly economics (energy)-driven and status-quo oriented, US approach is largely security-driven and a dynamic combination of status quo and revisionism. Essentially, this study offers critical policy analysis in a comparative setting. It attempts to empirically evaluate the Chinese and US foreign policy strategies in the Greater Middle East and investigate how they relate to each other. From this analysis, it hopes to reach conclusions that will shed light on the China-US relationship in the Middle East. Then, drawing on the conclusions reached, it offers policy recommendations on how to prevent a great power confrontation in the Middle East in order to better manage the regional peace, considering Beijing’s energy and Washington’s geopolitical interests. 6. It must also be noted that importing countries may have a certain level of leverage on the exporting nations especially if the oil producing country is export dependent. However, policy constraints outweigh policy leverages. A proper example would be the U.S-Saudi relations in which US dependency has constrained Washington in pushing for reform and democratization in the Kingdom, a clear contradiction with the US policy toward Iran. 9.

(19) It is acknowledged in this research that strategic decision-making requires considering the worst-case scenario and strategizing accordingly, drawing on verifiable empirical facts. Future is filled with uncertainties for states, as for individuals, and strategy-making leaves no room for optimist projections. Rather, the objective of strategizing is to remain prepared to and be able to address successfully the likely threats to national security no matter how far-fetched they seem at the moment. Therefore, in the case of China-US relations in the Middle East, the policy analysis this dissertation undertakes assumes that future holds a more contentious and competitive relationship due to an empirically-verifiable policy discord and offers recommendations accordingly. To further refine the policy analysis and draw on a larger theoretical basis, this research utilizes certain theoretical concepts such as national power, parity and overtaking as offered in power shift theories, primarily power transition and hegemonic decline models. National power includes GDP, population, military capacity and technology. It is observed that along with its growing national power, China has become more attentive and assertive in protecting its global strategic interests, including energy interests. It is also observed that (as will be shown in the case studies in the proceeding chapters) the US-China strategic competition in the Middle East primarily arises from a discord in each side’s conflicting policies: Whereas the US involvement in the region is more security-driven (explained by the US’ declining energy dependency and its historically strong political and military entrenchment), Chinese involvement is more energydriven (explained by China’s growing energy dependency and its minuscule military presence).This relationship is schematized in Figure 1 below: Figure 1: China-US Strategic Competition Independent Variables Independent Variables: China’s energy policy in the Middle East US security policy in the Middle East. Linking Variables China-US Policy Discord. National power (China-US power parity). 10. Dependent Variable Dependent Variable: China-US strategic competition.

(20) It must be underlined that the policy discord mentioned in this article does not arise from a competition between the US and China over scarce energy resources in the Middle East. As a matter of fact, US’ growing independency from the Middle Eastern energy resources is one of the fundamental causes for discord. Obviously not every two country experiences strategic competition only because they experience discord. Policy discord is possible when/if two states achieve near parity in national power. Because, when there is disparity, the powerful side can mobilize its hard or soft power mechanisms (or a combination of the two) to coerce/persuade the other side into its will. When there is parity (or near parity), however, existing disagreements could lead to protracted crises if the interests, priorities and policies of the two sides are incongruent. China’s energy-driven strategy in the Middle East is becoming less compatible with those of the U.S Among others, this could be ascribed to the simultaneous growth in Beijing’s national power and energy dependency. Consequently, as China moves from the traditional confines of its Middle East policy, a China-US strategic competition becomes intensified. The rivalry will likely continue as the US achieves greater energy independency as inversely proportional to China, which is projected to be more reliant on the Middle East in the coming decades. Unless policy congruency is sought and a certain level of interest equilibrium is reached, US-China relations will be less cooperative for the US currently has greater leverage and a larger room for maneuver in the Middle East as opposed to China’s energy dependency and lack of strategic depth. 7 Essentially, China-US relations are in transition and characterized by China’s growth and US’ relative decline. This transition distinguishes China-US relations from others. Building on this premise, this dissertation attempts to look at the impact of China’s energy security policies in the Middle East within the context of China-US great power interaction. To this end, it relies on primary and secondary data sources. The objective of this research is to offer an analysis on China’s energy policy in the Middle East by seeking an answer to the main question: What is the impact of energy security on China-US relations in the GME? 7. For example, China has no base agreements or any military contingency in the Middle East, which is a stark contrast to the United States’ overwhelming military presence. 11.

(21) From this, the following five research questions could be derived: i.. How do China’s energy security policy in the Middle East impact on US-China relations?. ii.. What internal and external dynamics shape China’s energy policy in the ME?. iii.. What are the consequences of the policy discord?. iv.. What would be the implications of China-US strategic rivalry in the Middle East for regional stability and peace?. Certain historical developments have triggered a change in China’s approach to energy security in the Middle East. Among those are the growing share of the region in China’s total energy import, the US political and military leverage in the region, US Navy’s control on the strategic sea routes and choke points through which most of China’s energy import is carried, and, finally, China’s speedy ascension to a great power status. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation of China’s policy behavior and interaction with the existing systemic leader, the US, in the Middle East may help gather greater insight into one of the world’s geopolitical hotspots, assist decision makers to better manage the China-US bilateral relations and promote regional peace. In a nutshell, this research is comparative in its scope, focusing on China’s relations with key regional energy producers in the Greater Middle East. By incorporating an analysis of the most recent political developments, it puts China’s growing energy dependency and engagement in the larger context of China-US competition and cooperation for greater influence in the region and speculates on how this would impact the regional and global peace. More specifically, this research contributes to the existing literature by offering a comprehensive analysis on China’s energy security policy in the Middle East in the light of recent developments. In this research, Chinese and US policy toward the Middle East is investigated comparatively, drawing on an extensive data and in depth interview with experts.. 12.

(22) Literature Review This chapter examines the contemporary scholarship on power shift theory and energy security. Thus, it is composed of two sections: In the first section, a detailed narrative of the scholarship on two select power shift theories, mainly the power transition and hegemonic decline theories, is given. To this end, the analysis begins with a general introduction, then proceeds with the explanation of basic concepts used by the power shift theories and, finally, it looks at the literature on the US-China relations within the context of power transition. The second part offers an analysis of the literature on China’s energy security. Similarly, it moves from general to specific. Thus, it first discusses energy security as a broad concept. Then it looks at the scholarship on China’s securitization of energy. In the third step, it reviews the recent scholarship on China’s energy policies in the Middle East. Finally, the chapter analyses the research done on the implications of China’s energy policies in the Middle East for US-China relations. Power Shift Theories Realist theory offers two divergent approaches to explain the distribution of power among states and its consequences. Whereas balance of power theory insists that (near) equality in power leads to peace, power shift school argues that balance in aggregate power is conducive to war. Classical realists such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz have dominated the international relations (IR) theory for decades and claimed that balance of power would create peaceful structural conditions (Mergenthau, 1993). This theory was later challenged by power shift theorists such as Kenneth Organsky and Jacek Kugler, hegemonic decline theorists such as Gilpin and Kennedy, and global cycles theorists such as George Modelski and William Thompson, all of whom attempted to prove that history and logic of power run contrary to what the classical realists have come to believe. The major argument of the power-shift theory is that the likelihood of systemic instability and wars increase, rather than decrease, in case of a power parity between two states. Preponderance in power, therefore, creates a situation more conducive to peace. Although they hold a common perspective of great power rivalry, power shift theories can be grouped according to their central argument: Power transition (Organski and Kugler), 13.

(23) hegemonic stability (Gilpin), global cycles (Modelski and Thompson), Kondratieff waves (Goldstein), and the world-system (Wallerstein, Chase-Dunn). Power transition differs from classical balance of power in three fundamental ways. First, it claims that international order is hierarchically structured, rather than anarchical. Second, power transition claims “that a large power gap dividing the dominant nation from the next layer of major powers facilitates maintenance of the international order, as created by the dominant nation. Instability arises when the power gap between the dominant nation and a challenger narrows” (Danilovic, 2003: 79).Third, the balance of power remains to be a theory of statics, while the power transition is a theory of dynamics” (Danilovic, 2003: 79) -- meaning that power transition perceives state relations as fluid in which they may surpass others and may be surpassed by them. Hegemonic decline theorist, Robert Gilpin, argues that although the international system is anarchical, it nevertheless maintains a level of control over the behavior of the state actors. To him, the system is stable as long as power is unevenly distributed and dominant state provides public goods. Hence, as long as both the system and its hegemon benefit from the uneven power distribution, stability is maintained. However, after a while, the cost of maintaining the order may become too big for the systemic leader. In this case, smaller powers that are not encumbered by such cost of maintenance may be able to rise relative to the hegemon and eventually challenge it (Gilpin, 1981). According to global cycles theory, international system evolves through cycles. Each period is composed of four phases: In macro-decision period, severe violence occurs but also the question of leadership is settled. Alternatively, leadership transition may also take place peacefully. In implementation phase the leader lays out the rules and expects others to comply. In agenda setting phase, the legitimacy of the status quo is questioned by the unsatisfied states. Finally, in the colitioning (decentralization) phase the field is once again open to the challengers which, if successful, set out new rules (Modelski, 1987). The World-System argues that major wars are the periodic phases in the expansionary patterns of world capitalism. The modern world is divided between core and periphery states 14.

(24) and the strong core exploits the weak periphery. However, as the cost of hegemon’s rise begins to exceed the gains (such as excessive spending on military), it begins to decline relative to other core states. As each core strives to restructure the world economy to its advantage, war might ensue. Also, the theory argues that an uneven growth between a hegemon and the rising power might eventually lead to a war – often a war of preemption by the declining super power to maintain leadership (Wallerstein, 1980). In this study, frequent reference is made to power transition and hegemonic decline theories as they are related to the contemporary China-US relations. Of the two theories, power transition model seems to be more relevant to the study at hand, so greater emphasis is put on it. Power transition provides an alternative reading of the world system. It challenges the assumptions of liberal institutionalism and realist balance of power as briefly introduced above. It sees that the post-World War II order has not deterred nations from turning to military build-up in spite of the existence of various international organizations and of power parity between the US and the USSR. In fact, balance of power encouraged an arms race between the Eastern and Western blocs, bringing them closer to a nuclear catastrophe. Consequently, it is understood that power tends to create imbalances and resultant crises (Organski, 1968). Although under-researched, one of the most crucial concepts utilized by power transition is satisfaction. Satisfaction influences the behavior of a contending country and the nature of its relationship with the international status quo regime and its leader (Kugler and Lemke, 1996). Although without much elaboration, Organski states that whereas some great powers are satisfied with the existing global order because it is perceived as offering the best opportunity to achieve certain national goals, others are not satisfied because they “have grown to full power after the existing international order was fully established and the benefits are already allocated” (Organski, 1958: 366). Accordingly, even though great powers grow within the existing global regime by utilizing the instruments such as open sea lanes for trade, international arbitration for disputes, or benefits from membership in elite institutions, they may not implicitly endorse it, first, because of the lack of a sense of full utilization (e.g., the US and EU ban on the export of sensitive technologies to China or China’s worries about its energy 15.

(25) security due to lack of control on the source and the transportation routes) and, second, because of some inherent inequalities within the system toward the late comers (such as the appropriation of secure and stable areas of natural resources by Western companies, leaving less secure and stable areas in the Middle East and North Africa to Chinese companies for expropriation). A distinction is made between states being dissatisfied with each other and with the international system (Bueno de Mesquita, 1990). The former case may lead to competition and conflict more often but its scale remains small whereas, in the latter case, the competition may result in a deeper crisis such as a large scale armed confrontation although its occurrence is less frequent. However, distinction between these two types of dissatisfaction gets blurred in a great power-dominant power dyad. Given that the dominant power assumes a key role in establishing and protecting the international system, dissatisfaction leveled at the systemic leader is by default leveled at the system itself, as well. However, not all cases of dissatisfaction may lead into a conflict (Kugler and Lemke, 1996). There may be numerous reasons to persuade the challenger to tone down its rhetoric against the leader and the leader to seek compromise with the challenger. As it has been found elsewhere, the strength of power transition depends to a great extent on the measures applied and cases selected (De Soysa, et al., 1997). Related to the theory of power transition is parity and overtaking (See Figure 2). Parity in a dyad is achieved when one of the powers registers a sustained and faster growth rate, higher population and greater political capacity than the system leader (Kugler and Lemke, 1996). In that stage, the leader’s hegemonic position within the hierarchy suffers a decline because the challenger manages to continue to increase its national power and the risk of conflict increases. Parity is reached when the challenger state achieves 80% of the dominant state’s national power and ends when its power exceeds 20% or more that of the leader. “Defined as the passing of one major power by the other,” overtaking may happen at both regional and global levels. There may also be transitions between the levels. However, the most destabilizing transition is when a rising regional power attempts to overtake a declining global power (Kugler and Lemke, 2006).. 16.

(26) Parity and overtaking by themselves may not be a direct cause for conflict. For systemic transitions to become conflictual, the rising state must be willing to challenge and attempt to revise the status quo. If the dominant power is suspicious of the challenger’s behavior, then it may choose to defend the status quo by preempting the challenger’s rise. An overtaking may be peaceful if both the challenger and defender are satisfied with the status quo (Tammen, et al., 2000). This is the case in which the system leader shares certain traits (e.g., political and economic ideology, culture, and language) with the rising state and the dyad maintain a strong alliance after the overtaking, thereby retaining for the declining dominant power most of the benefits that it derived globally by virtue of being the leader. In this case, the new emerging power continues from where the former dominant power has left off. China’s status as a rising power is little disputed. The question whether Chinese overtaking of the existing dominant power will be peaceful or conflictual less agreed upon (Legro, 2007; Waldron, 2005; Glaser and Medeiros, 2007). Studies interpret the post- WWII resurgence of China from different perspectives. Liberal school, more specifically, the liberal institutionalists, argue that economic interdependence coupled with Beijing’s increased participation in the international institutions will socialize it into the global norms, decreasing a likelihood of a challenge that is potentially destabilizing (Goldstein, 2007; Olimat, 2008). Classical liberals place full faith in the market processes and hold that as the Chinese middle class grows, the potential for a democratic transformation will become inevitable. Democratic peace theory within the liberal tradition further maintains that, when the Chinese institutions adopt democratic values, the prospects for conflict with the US will be extremely reduced. Hence, they believe that the current liberal international order might accommodate China’s rise successfully as China suits itself into it (Choo, 2009). On a similar vein with the liberals, skeptics hold that China’s rise is not absolute in terms of the decline in US power because, some serious structural problems notwithstanding, the US is not in the course of a decline reminiscent of the Soviet Russia. In fact, it still retains leadership in many fields of international economy and has a clear advantage over China with respect to influence on international politics, economics and culture. Constructivists, on the other hand, argue that “a shared identity will determine whether two states view each other as 17.

(27) threats” (Wendt, 1999: 1). They maintain that China has in fact moved from an aggressive revolutionary model of governance to a market-oriented global citizenship and become interconnected with the international community, increasingly abiding by the established rules and regulations (Wendt, 1994). Constructivists, consequently, argue that China’s increasing international participation at various levels will cause a change in its “strategic culture, in the norms of international behavior accepted by its leaders, and ultimately in their conceptions of national identity” (Friedberg, 2005: 35). Most realists do not hold a similar optimism; rather, they perceive China’s continuous growth in national power as a potential catalyzer of a destructive power struggle (Mearshimer, 2001 and 2006; Walt, 2010). They maintain that if a bipolar world emerges as a result of a USChina competition, a security dilemma might arise. In this case, as China increases its influence, the US, together with its allies, may be forced to balance these moves, which in turn may lead to an arms race. This concern stems from the belief that China’s growing strength will enable it to pursue its interests more assertively and less respective of international rules and norms (Glaser, 2011). Consequently, whereas offensive realists call for preemptive policies to stave off China’s growing might before it is too late, defensive realists consider precautionary policies (such as strengthening regional alliances and containment) to be sufficient to prevent China from being over-ambitious. The power transition theory holds a mostly pessimistic view of great power relations although it agrees that there may be certain conditions under which a transition proceeds smoothly. It asserts that parity between two great powers is a potentially dangerous phenomenon and only when power is asymmetrically distributed that is peace assured (Kugler and Organski, 1989). Thus, the theory offers the concept of power preponderance to replace hegemony. A great power remains dominant but does not become a hegemon; it maintains the power preponderance by managing the international system under rules that are beneficial to its allies and satisfy their aspirations (Lemke, 1997). Power transition’s approach to the rise of China stems from two major concerns: The first arises from the conviction that, despite of its relative opening-up since the late 1970s, China has yet to become a full pledged member of international community. Indeed, China 18.

(28) carried out a number of market reforms and liberalized its economy to some extent; however, its political system remains unchanged notwithstanding some internal reforms, which is the result of an extreme incrementalism the Chinese government has been practicing. Furthermore, contrary to the expectations, Chinese political model showed strength and durability, as exemplified by the last successful leadership transition. The second concern is related to China’s great power behavior, namely, the question of compliance with the rules of international status quo regime. China is poised to overtake the US in terms of the size of its economy. According to the OECD projections, China will surpass the US to become the world’s largest economy as early as 2016. Furthermore, using a new model for projecting growth in 34 OECD member states and eight major non-OECD G20 economies over the next 50 years, the report, Looking to 2060, states that China will surpass the EU in one or two years and, by 2025, the combined GDP of China and India will surpass that of the major seven (G7) OECD economies. Hence, it is “the differential rate of change between the international distribution of power and the other components of the system that produces a disjuncture or disequilibrium” (Gilpin, 1981: 41). An overtaking of the US by China may create conflict in the China-US dyad and deep fluctuations in the international system if there is no change in China’s evaluation of the status quo or in the behavior of the US toward China’s rise. The power transition sees China’s high-speed ascension to great power status as potentially disruptive of the existing great power peace. According to Organski, the speed of the rise of a state to great power status might have a “stunning effect” on the dominant country, thereby reducing its capability to make adjustments in the system to accommodate the upstart and protect the status quo (Organski, 1968: 335). The result of such a systemic crisis might lead to a Cold War-like confrontation or an outright war as was witnessed during the rise of the German state in 1930s and the response to it by then dominant, albeit declining, power, the UK (Lemke, 1997). There is a growing conviction among some scholars and policy-makers in the West that China is” trying to turn the tables and redefine the powerful concept of the international community” (Ching, 2012). This idea is directly linked to the question whether China is status quo-oriented power or not (Chang, 2012). Some see China’s rise as problematic since the CCP 19.

(29) has no intention to democratize itself, let alone integrating with the norms of developed democracies. Furthermore, as they argue, China is working against the global governance by creating its own set of alliances clustered around a different set of norms. It is for this reason that the Chinese government prefers the ASEAN+3 over the APEC. In short, they claim that China’s participation in international organizations is not genuine; it is not to transform itself but to transform those organizations or at least prevent them from turning against itself (Friedman, 2011). In the similar vein, John Mearsheimer argues that “a wealthy China would not be a status quo power but an aggressive state determined to achieve regional hegemony” (Mersheimer, 2001: 4012). Mearsheimer’s views reflect a major strand in the US strategy circles. According to them China cannot be expected to adopt the US-led model because, in proportion to its economic, political and military capabilities, Beijing will demand more and when the international system is unable to meet its demands, China will attempt to remold it. Obviously, the preferences of the Chinese government are not free from external influences. Some argue that, in fact, structural conditions may lead to integration (Efird et al., 2003). In their empirical study, Brian Efird et al. show that although sometimes domestic constituency and policy makers influence relations between states, it is international structure that really impacts the international behavior of a state. Hence, the choice between China as a “strategic partner” and China as a “strategic competitor” will determine China-US transitional relations to a large extent (Efird et al., 2003, 21). The discussion on China’s international behavior as it ascends to great power status comes down to the important distinction made between satisfied and dissatisfied nations, a concept that is central to the power transition discourse. Satisfaction is related to a “distribution of power and allocation of benefits” (Chan, 2004). Consequently, it is not simply an issue of material prosperity (benefits) but also of sharing the responsibility of international governance (power). If a great power that is capable of exerting influence on the international system is only allowed to participate in but not to modify the existing status quo as it deems fit, this may create dissatisfaction. Great powers are not always revisionist by default, but the greater the differences between the challenger and the leader’s vision of international system, the greater the chance 20.

(30) for the start-up to adopt revisionism. It is argued that China’s structural differences from the US make it a non-status quo candidate. In fact, according to many, it is already one. China’s energy policies in North Africa and the Middle East, its relationship with nations such as Iran and Venezuela, or its arms sales are oft cited examples of China’s global attitude (Kent, 2007; Friedman, 2008; Hanre, 2008; Legro, 2007; Medeiros, 2007). It is instructive to look at China’s approach toward its energy security in the Middle East because it sheds light on the projections on the US-China relations. Among the indicators for China’s energy security strategy, participation, or compliance, is one of the most important. This is due to the fact that, for many, China is considered “the least-likely case of compliance by virtue of its history, cultural traditions, and power” (Kent, 2007: 2). Indeed, as crucial as the quantity of participation, if not more, is the quality of it, an issue which attracts opinion from both China pessimists and optimists (Xia, 2001; Johnston, 2003). One of the hypotheses put forward in this research is that as China grows exponentially in national power and international influence while at the same time its energy dependency deepens, the nature of its energy-driven ME policy will slowly change from one of reactive to proactive, creating policy discord with the US Obviously, the Chinese policy making does not function in a vacuum; any action that Beijing takes with respect to participation in international energy regime occurs within the larger context of external and internal forces. Like any other state actors, Chinese behavior influences others and is influenced by them. It needs to be stressed that non-cooperation does not necessarily mean defection; rather, it may suggest an attempt to modify and change the system from inside, hence the difference between system change and systemic change. How the keepers of the existing regime respond to this desire will determine whether this great power relationship is poised to be conflictual or peaceful (Xia, 2001). This calls for another distinction between compliance and cooperation. Comparatively speaking, compliance is easier to achieve; however, as long as there is dissatisfaction, cooperation may not be that easy to materialize. Compliance designates “the need to move beyond sole consideration of formal compliance (and non-compliance) in evaluating the integration of a state into the international system;” hence, it is a broader 21.

(31) concept than cooperation and actually suggests willing and active participation (Kent, 2007: 16). Most of the discussion on China’s participation is in fact centered on the degree of cooperation, rather than compliance, because, in a sense, the international regime leaves few options but participate. Cooperation is more qualitative and harder to measure. One may take Iran and Israel’s non-proliferation regimes as an example. Whereas the former is signatory to the NonProliferation Treaty (NPT), hence participates in it, the latter is not, hence, does not participate. However, the quality of Iran’s compliance (political implementation) does not convince most of the international community of its level of cooperation (political internalization), whereas Israel, which does not participate, is nevertheless considered compliant and cooperative. In the same vein, Anne Kent argues that while China complies with international rules and norms, “it has not often cooperated with them.” Rather, China demonstrated an “uneven pattern of compliance.” However, on a positive note, even though China has thus far lacked a genuine participation, it has had a positive “impact on the international system and on the development of international law” (Kent, 2007: 5). Communication with international pressures has led China to put more effort to align its domestic (or, national) interests with those of the international community. Yet, China’s participation is still not seen as fully cooperative and thus not fully meaningful. From the perspective of energy security, China’s participation and level of cooperation is questioned by the US policy makers and strategists. For example, on the issue of China-Iran energy relations, the 2011 Report to Congress by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC) states in rather strong terms that “Despite US efforts to sanction Iran for its support of international terrorism and pursuit of weapons of mass destruction, China remains a large investor in Iran’s petroleum industry and a major provider of refined oil products…. China’s investment in Iran’s petroleum industry, and its continued provision of gasoline and advanced conventional weapons may be at odds with US laws.” Hence, it has been claimed that China has often neglected US security concerns in its economic relations with the countries on the US blacklist especially when it has felt that its energy interests and security are compromised.. 22.

數據

Outline

相關文件

• helps teachers collect learning evidence to provide timely feedback & refine teaching strategies.. AaL • engages students in reflecting on & monitoring their progress

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

How does drama help to develop English language skills.. In Forms 2-6, students develop their self-expression by participating in a wide range of activities

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it

(a) the respective number of whole-day and half-day kindergarten students receiving subsidy under the Pre-primary Education Voucher Scheme (PEVS) or the Free Quality

O.K., let’s study chiral phase transition. Quark