行政院國家科學委員會

獎勵人文與社會科學領域博士候選人撰寫博士論文

成果報告

The Vertical Information Transfer Effects of

Earnings Restatements along the Supply Chain

核 定 編 號 : NSC 96-2420-H-004-011-DR 獎 勵 期 間 : 96 年 08 月 01 日至 97 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學會計研究所 指 導 教 授 : 陳聖賢 博 士 生 : 賴淑妙 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 98 年 08 月 17 日

國立政治大學會計學系博士論文

Department of Accounting

National Chengchi University

Doctoral Dissertation

盈餘重編之供應鏈外溢效果

The Spillover Effects of Earnings Restatements Along the

Supply Chain

賴淑妙

Shu-Miao Lai

指導教授:李怡宗教授、陳聖賢教授

Advisor: Professor Yi-Tsung Lee; Professor Sheng-Syan Chen

中華民國

98 年 5 月

謝辭

本論文得以順利完成,首先感謝我的兩位指導教授 李怡宗老師與陳聖賢老 師。感謝李怡宗老師對我在研究思考及為學處事態度上的訓練,並引領我熟悉電 腦程式以效率性的方法處理實證資料。感謝陳聖賢老師在論文方向形成過程中的 訓練,讓我能有獨立思考的研究能力,其引導我找到研究的枝幹去發展更多的枝 葉。從兩位恩師的身上看到其對研究的熱忱與努力,是我未來從事學術研究的好 榜樣。此外,感謝口試委員林修葳老師、劉啟群老師、李書行老師、張清福老師、 周玲臺老師以及洪淑民老師提供許多寶貴建議與幫忙使論文得以更加完整。 回想博士班生涯的點點滴滴,從一個非會計背景的我到取得會計博士學位, 這一路走來,難以言喻的體會在心頭。博一初次接觸會計學研究是生疏的,忙著 補修大學部的基礎課程,以及兼顧博士班學程的課業,但日子卻是充實的。其中, 特別要感謝系上的大家長鄭丁旺老師所曾經給予我的幫助與鼓勵。博二開始接觸 到會計研究,感謝系上多位授課老師的用心教導,啟發了我對會計學術研究的興 趣。尤其感謝俞洪昭老師在 directed study 這門課的用心指導,讓我體會到奠定 良好研究態度的重要性。博三則是準備資格考,這期間非常感謝博班的同學素 芳、倩如、淑慧在資格考準備過程中能一同討論分享謮書心得、相互加油打氣, 使得我能以事半功倍的方式準備資格考。最後階段的論文口試,感謝學妹玉君以 及系上育琦助教所提供的一切協助,讓論文口試得以順利進行。 這一路走來,深感幸運的我,生命中有個重要的貴人,我的先生志諒。十幾 個年頭的求學生涯中,其扮演著良師益友的角色。當我有課業及論文相關問題 時,他總是不厭其煩地與我討論,更在我感到挫折、無助時成為我的精神食糧。 其對我的付出及呵護所累積的感謝及感動是此筆墨難以形容的。 最後,將此論文獻給我最敬愛的父親賴賜義先生與母親巫花女士,因為有您 們給我的關愛與支持,讓我得以幸福地成長並朝著自己的夢想前進。感謝我親愛 的手足淑伶、惠子、淑均及璟賢,因為有你們所營造的溫馨關懷與鼓勵,讓我即 使處在逆境都覺得求學生涯充滿歡樂,並有著更多的勇氣接受挫折與挑戰。同 時,感謝曾經給我有形、無形幫助的師長、朋友、學長姊以及學弟妹,因為有您 們鼓勵與支持讓我的求學生涯得以順利,願將這份小小的成就以及喜悅與您們共 享。 賴淑妙 謹識 於政大會計學系博士班 民國九十八年五月摘要

本研究主要探討盈餘重編宣告如何影響重編公司之供應商的股價評價與實質投 資決策。首先,本研究假設並發現,盈餘重編宣告除了導致重編公司的股價顯著下 跌外,亦誘發其上游供應商的股價顯著下跌。實證進一步發現,供應商的股價依盈 餘重編之資訊內涵而調整,促使投資人關注重編事件對上游供應商的預期盈餘之影 響,也提醒投資人去關心上游供應商的財務報表品質。其次,本研究假設,盈餘重 編宣告傳遞有關重編公司未來前景不佳及財務報表不實的資訊,將影響其供應商對 投入特定關係資產所能獲得收益之預期,進而影響其對重編公司所投入的特定關係 資產投資決策。實證結果支持前述假說,重編公司之供應商於重編宣告年度後將減 少其研究發展支出,且此研究發展支出之變動與重編宣告所引起的股價變動具顯著 關聯性。最後本文假設,重編公司扭曲其實際盈餘數字將影響供應商的投資決策, 進而影響供應商的投資效率性。研究發現,供應商在重編公司財務報表誤述期間有 顯著超額投資之現象。然而,此供應商之超額投資現象在盈餘重編宣告年度後不再 顯著。 關鍵詞:盈餘重編、資訊移轉效果、對特定關係資產投資、投資無效率、供應商。Abstract

This dissertation extends prior research on earnings restatements by examining the effects of earnings restatements on valuation and investment decisions of restating firms’ suppliers. First, this paper hypothesizes and finds that earnings restatements that adversely affect stock price of the restating firms also induce their suppliers’ stock price declines. These stock price declines are related to changes in analysts’ earnings forecasts and seem to reflect investors’ financial reporting quality concerns. Second, I hypothesize that earnings restatements contain information about the value of relationship-specific investments by suppliers. This information causes suppliers to revise their belief about the value of relationship-specific investments, and therefore affects their subsequent relationship-specific investment decisions. Consistent with my prediction, I find that changes in suppliers’ relationship-specific investments after restatement announcements are related to information in the restatements. Finally, I predict and find that a restating firm misreporting financial results induces its suppliers to make excess investments during the misreporting period, while excess investment is no longer positive after the restatement announcement.

Keywords: earnings restatements; information transfer effects; relationship-specific

Table of contents

謝辭 i

Abstract ii

Table of contents iii

List of tables v

1. Introduction 1

2. The vertical information transfer effects of earnings restatements along the supply chain 4

2.1. Introduction 4

2.2. Literature review and hypothesis development 8

2.2.1. Earnings restatements and valuation effects 8

2.2.2. Earnings restatements and intra-industry information transfers 9

2.2.3. Vertical information transfer hypotheses 10

2.3. Data 14

2.3.1. Sample selection 14

2.3.2. Characteristics of suppliers 16

2.4. Empirical results 16

2.4.1. Abnormal returns to restating firms and suppliers 16

2.4.2. Supplier contagion returns and analysts’ earnings forecast revisions 19

2.4.3. Supplier contagion returns and accounting quality of suppliers 20

2.5. Robustness checks and sensitivity tests 27

2.5.1. Industry-level information transfer effects 27

2.5.2. Restatements with negative valuation effects 28

2.5.3. Alternative measure of accounting quality 28

2.6. Summary 29

3. The impact of earnings restatements on suppliers’ relationship-specific investments 37 3.1. Introduction 37

3.2. Literature review and hypothesis development 41

3.2.1. Financial reporting and suppliers’ investment decisions 41

3.2.2. Earnings restatements and relationship-specific investments by suppliers 42 2.2.3. Hypotheses 44

3.3. Research design 45

3.3.1. Proxy for relationship-specific investments by suppliers 46

3.3.2. Changes in suppliers’ relationship-specific investments 46

3.3.3. Empirical model 47

3.3.4 Sample 49

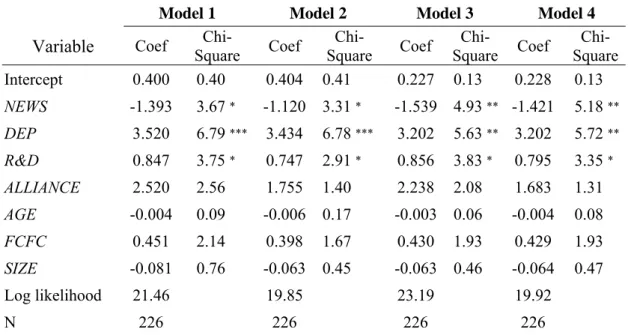

3.4. Empirical results 51

3.4.2. Changes in suppliers’ R&D intensity and restatement news 52

3.4.3. Cross-sectional variation analysis 55

3.4.4. Earnings restatements and duration of supplier and the restating firm relationships 56

3.5. Summary 59

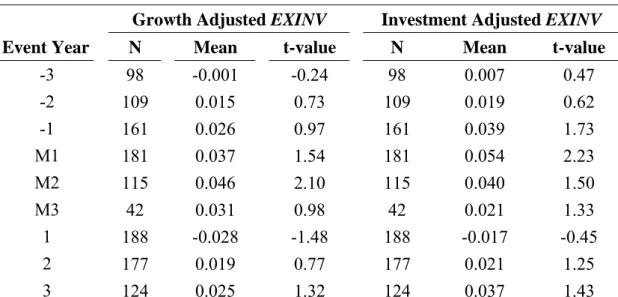

4. Earnings restatements and the efficiency of supply chain capital investments 67

4.1. Introduction 67

4.2. Literature review and hypotheses 70

4.2.1. Financial reporting quality and investment decisions 70

4.2.2. Financial reporting quality and suppliers’ investment decisions 71

4.2.3. Hypothesis development 73

4.3. Research design 74

4.3.1. Identifying excess investment of suppliers 74

4.3.2. Empirical procedures 75 4.3.3. Sample 76 4.4. Empirical results 78 4.4.1. Descriptive statistics 78 4.4.2. Primary results 79 4.5. Summary 83 5. Conclusions 91 References 92

List of figures

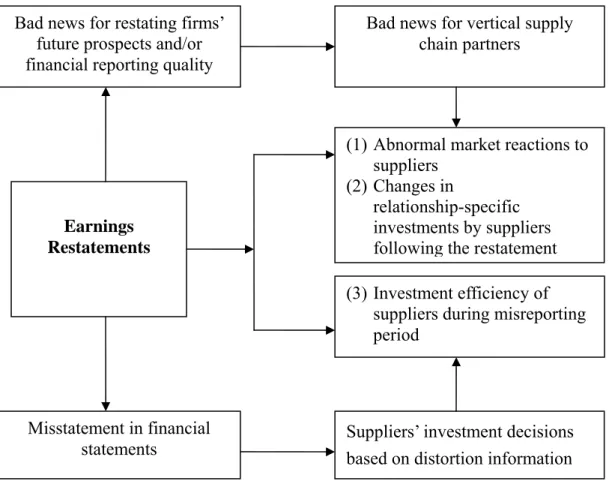

Figure 1.1 Research Framework 3

List of tables

Table 2.1 Sample distribution 31Table 2.2 Characteristics of suppliers 32

Table 2.3 Abnormal returns to restating firms and suppliers 33

Table 2.4 Revisions in analyst earnings forecast surrounding earnings restatement announcements 34

Table 2.5 Cross-sectional analysis for suppliers 35

Table 2.6 Abnormal returns to supplier industry 36

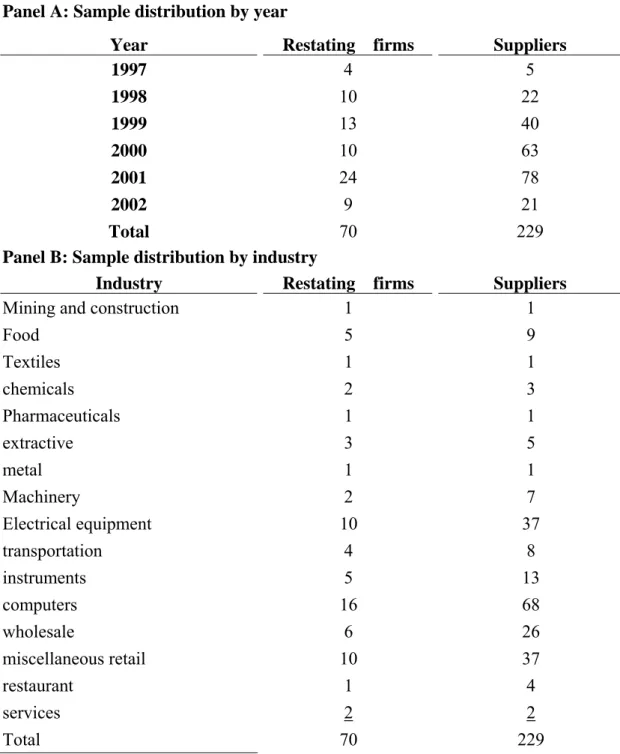

Table 3.1 Sample distribution 60

Table 3.2 Annual changes in suppliers’ R&D investments around the restatement announcement 61

Table 3.3 Descriptive statistics 62

Table 3.4 Changes in suppliers’ R&D as a function of the news in the restatement 63

Table 3.5 Changes in suppliers’ R&D as a function of the types of earnings restatements 64

Table 3.6 The impact of the economic bond on the relation between changes in suppliers’ relationship-investment and news in the restatement 65

Table 3.7 Duration analysis 66

Table 4.1 Sample distribution 85

Table 4.2 Sample summary statistics 86

Table 4.3Excess investment through event time 87

Table 4.4 Excess investment through event time-by level of severity of restatements 88

Table 4.5 Mean investment through event time-relative to control Firms 89 Table 4.6 Excess investment through event time-by the types of earnings restatements 90

1. Introduction

Earnings restatements occur when financial reports are discovered not to be consistent with the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Empirical evidence indicates that restating firms experience a significant decline in their stock price (Palmrose et al. 2004), suggesting restatement announcement conveys incremental information. Furthermore, it appears that restatement information is transferred from restating firms to the rivals in their industry. Existing research finds that rival firms of the restating firm also suffer significantly negative abnormal returns at restatement announcement (Xu et al. 2006; Gleason et al. 2008).1 The information in restatements also alters rivals to revise their belief about the value of the investments, and therefore affects their subsequent investment decisions (Durnev and Mangen 2008). This suggests that earnings restatements provide new information to rivals about the value of their investment projects.

Earnings restatement information released by one firm has a resulting effect on the firm’s suppliers, suggesting that vertical spillover effects of earnings restatements spread along the supply chain. In the customer-supplier relationship, the correlation in the economic activities of restating firms and their suppliers is positive. With a positive correlation in economic activities of restating firms and their suppliers, restatement information which conveys information about the restating firms will also convey news about a supplier, therefore affects the suppliers’ stock price and investment decisions. In addition, prior research suggests that suppliers use major customer’s financial reports as an information source for their investment decisions (Raman and Shahrur 2008), suggesting that restating firms misreporting financial results will affect the supplier’s investment decisions. To date, few studies have examined whether and how earnings restatements affect

suppliers’ stock price and capital investment decisions. My dissertation contributes to restatement research by examining whether and how earnings restatements released by one firm have valuation and investment implications for firms that are linked in the supply chain.

Specifically, this dissertation addresses this research issue in three essays by examining (1) whether and how information released by earnings restatements affects the valuation of the restating firm’s suppliers surrounding the restatement announcement, (2) whether and how earnings restatements discovered at one firm affect the incentives of suppliers to undertake relationship-specific investments following the restatement, and (3) whether a firm misreporting financial results induces its suppliers to make suboptimal investments during the misreporting period.

The remainder of this dissertation is organized as follows. In the chapter 2, chapter 3, and chapter 4, I present the three studies related to the effects of earnings restatements on suppliers. In each of these studies, I describe the research methodology and present my empirical results, after that I discuss the findings. The chapter 5 I conclude the major findings of these studies, whereas I indicate possible limitations and suggest some potential directions for future research.

Figure 1 Research Framework

Bad news for vertical supply chain partners

Misstatement in financial statements

Earnings Restatements

Bad news for restating firms’ future prospects and/or financial reporting quality

(1) Abnormal market reactions to suppliers

(2) Changes in

relationship-specific investments by suppliers following the restatement (3) Investment efficiency of

suppliers during misreporting period

Suppliers’ investment decisions based on distortion information

2. The vertical information transfer effects of earnings

restatements along the supply chain

2.1. Introduction

The collapse of Enron and the sharply increasing number of earnings restatements have raised widespread loss of investor confidence in the content and credibility of financial reporting.2 This loss of market trust is a cumulative process with spillover effects. For example, the day after WorldCom announced it would restate earnings to the tune of $3.8 billion, rival firms with questionable reporting, such as Qwest, experienced noteworthy crashes in their stock prices. In addition, WorldCom’s restatement announcement also induces adverse effects on its key suppliers’ stock prices.3 This suggests that the vertical information transfer of earnings restatements spread along the supply chain.

This paper examines whether and how information released by earnings restatements affects the valuation of the restating firm’s suppliers. In customer-supplier relationship, the partner firms are stakeholders in each others’ operation. This contractual relationship between a firm and its supply chain partners may be either implicit or explicit. Theory suggests that reported earnings are informative about one firm’s futureprofitability, and often use in contracts or sever as monitoring mechanisms (Bushman and Smith 2001). Thus, information in earnings restatements to one of the firms in the relationship has a resulting effect on its supply chain partners.

Earnings restatements are likely to convey value-relevant information that will affect stock prices of suppliers for two reasons. First, some restatements have a material adverse effect on restating firm value (Palmrose et al 2004; Hribar and

2 Through the end of October, there were 1,031 restatements, compared with 650 for all of 2004 and

only 270 in 2001, the year Enron collapsed, according to figures compiled by Glass, Lewis.

3 See for example, “Impending WorldCom Bankruptcy?” (RHK Telecommunications Industry Analysis, June 27, 2002).

Jenkins 2004), which provides evidence that restatements are really bad news for restating firms’ future earnings prospects. Second, restatements are acknowledgement that prior financial statements were misstatement. They indicate a breakdown in a firm’s internal control system (Kinney and McDaniel 1989), which increases information risk for investors. Consequently, earnings restatements will convey information that alters investors’ perceptions about the future earnings performance and/or financial reporting quality of suppliers of restating firms, because such event is a salient negative firm-specific event.

This paper hypothesizes that earnings restatements have negative implications for the restating firm’s stock prices will also convey bad news about the value of its suppliers for two reasons. First, earnings restatements with negative implications for restating firms’ future prospects could convey information that the ability and incentive of the restating firm to honor its explicit or implicit commitments for customers and suppliers is perceived to be lower. As suggested by implicit contract studies, financial health influence the restating firm’s incentive to continue to invest in upholding its reputation for dealing honestly with suppliers, for providing quality products to it customers, and for its overall integrity (see, e.g., Bowen et al. 1995; Burgstahler and Dichev 1997; Cornell and Shapiro 1987; Maksimovic and Titman 1991). Second, earnings restatements revealing improper accounting practice and accounting irregularities may also convey unfavorable information about the accounting quality of the restating firms’ suppliers, which likely damages the investors’ confidence in the accounting practices of the restating firm’s suppliers. Thus, the bad news embodied in restating firms’ restatement announcements will be incorporated into the suppliers’ stock prices.

Using firm-level data, I find that significant negative abnormal returns to major suppliers surrounding earnings restatement announcements. This is evidence that

investors update their valuation about suppliers that has made an implicit or explicit business transaction commitment based on the information conveyed by restatements. I also find supplier contagion effects are more prominent for restatements that result in a more negative abnormal return to the restating firm at the time of restatement announcements and for restatements that are to correct revenue recognition errors. Moreover, I find supply chain contagion effects are more prominent for restatements that involve accounting fraud, suggesting fraud restatements cause more concerns about the financial reporting quality of suppliers, thus the stock price effects on suppliers are likely to be most evident around fraud events.

In addition to examining whether earnings restatements induce supply chain information transfer effects, my analysis further extends previous research by considering how earnings restatements provide useful information about the future prospects of the restating firm’s suppliers. To test this economic prospect concern, this paper hypothesizes that revisions in analysts’ earnings forecasts convey information about future earnings prospects for suppliers. Consistent with this conjecture, I find that analysts revise their earnings expectations for suppliers downward after the announcement of restatements. Changes in analyst earnings forecast revisions for suppliers are positively related to proxies for information in earnings restatements, such as suppliers’ and restating firms’ abnormal returns surrounding the restatement announcements.

To test whether earnings restatements induce accounting quality concerns over suppliers, I conduct a cross-sectional variation in restatement information transfer effect on suppliers. As expected, I find that suppliers suffer greater negative valuation effects when they have high performance-adjusted discretionary accruals, suggesting earnings restatements alter investors’ perceptions about the financial reporting quality of suppliers. Furthermore, I find that accounting fraud restatements increase perceived

risk/uncertainty for suppliers and so are associated with more negative supplier contagion stock returns. This suggests that fraud restatements are more likely to prompt investors to question over the suppliers’ accounting quality. Finally, I use several variables (suppliers’ sales dependence and alliance agreement) to measure the extent to which economic activities of suppliers rely on the restating firm. I find that suppliers suffer greater negative valuation effects when their economic activities are more reliant on the restating firms. This evidence suggests that the stock market reaction to earnings restatement announcements takes into account the economic activities that relate suppliers to the restating firms.

This paper makes several contributions to literature on earnings restatements and information transfers. First, this study extends the recent evidence in Gleason et al. (2008) of earnings restatements induce intra-industry contagion effects on rivals in the same industries. As indicated by Olsen and Dietrich (1985) and Bernard (1985), the information transfers are not necessarily limited to firms’ industry rivals. My paper provides new evidence that investors update their valuation about suppliers of the restating firm based on the information conveyed by earning restatements. Second, my findings also complement prior research on supply chain information transfer (e.g., Olsen and Dietric 1985; Hertzel et al. 2006; Pandit et al. 2007). My paper provides new evidence, in the context of material accounting irregularities, complements a much richer setting in accounting and finance literature regarding to how material earnings-related information affects the valuation for the restating firm’s supply chain partners. Finally, this paper also documents several factors that help explain cross-sectional variations in the supplier’s stock price response to restatement announcements. Thus, my findings further shed some light on how

restatement-induced vertical information transfers operate (e.g., Schipper 1990).4 The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2.2 reviews prior research and develops hypotheses. Section 2.3 describes research design and sample selection. Section 2.4 presents my empirical results. Section 2.5 provides robustness tests. My conclusions are presented in Section 2.6.

2.2 Literature review and hypothesis development 2.2.1. Earnings restatements and valuation effects

There has been substantial empirical research examining whether earnings restatements are associated with changes in stock prices. A large majority of studies have documented that restatement announcement typically has a substantial adverse valuation effect on the restating firms. The short-window cumulative average abnormal returns surrounding the restatement announcement range from –9.2 percent (Palmrose et al. 2004) to -12 percent (Turner et al. 2001). In addition, Dechow et al. (1996) find a –6 percent average return for a subset of restatement announcers that eventually subject to SEC enforcement actions.

The loss in market value can be attributed to diminished economic prospects, as measured by a downward revision in future expected earnings (Griffin 2003; Palmrose et al. 2004), 5 and a increase in information uncertainty/risk, as measured by an increase in analyst forecast dispersion (Palmrose et al. 2004) and cost of capital (Hribar and Jenkins 2004). 6 Consistent with diminished economic prospects agreement, Palmrose and Scholz (2004) found that 18 percent of restating firms are subsequently delisted and/or eventually file for bankruptcy protection. Restatements also have an adverse impact on the reputation of management and outside directors.

4 In Schipper (1990, p.101) notes that when compared to whether information transfers exist or not,

“so far little attention has been given to explaining how such transfers operate.”

5 Consistent with this notion, Griffin (2003) finds that analysts are more likely to revise forecasts

down in the month of or up to six months after restatement than before.

6 Information uncertainty/risk is uncertainty about the realized values of earnings caused by financial

Some restating firms’ management (Desai et al. 2006) and outside directors (Srinivasan 2005) suffer high turnover, and the incidence of lawsuit filed against firms following the restatement is high (Palmrose and Scholz 2004). Overall, these findings suggest that earnings restatements are negative firm-specific information events, and they are very costly for restating firms.

2.2.2. Earnings restatements and intra-industry information transfers

Information transfer or contagion effect is firm-specific information event at one firm can have valuation implications for other related firms. This information transfer has been documented for different types of firm-specific information events in an the intra-industry setting, suggesting news releases of a given firm within an industry will impact on non-announcing firms in the same industry surrounding the information events announcement date. 7 Perhaps the most commonly investigated information events are related to earnings announcement.8

Recognizing the importance of the restatement-induced contagion effects on the restating firms’ rivals, recent research documented that information conveyed by restatements is transferred from restating firms to their rivals in the same industry, in which rivals experience significantly negative abnormal returns at the restatement announcement (e.g., Xu et al. 2006; Gleason et al. 2008). This supports the notion that the restatements induce intra-industry contagion effects. This intra-industry information transfer is greater for industry rivals with lower earnings quality which measured by abnormal accruals (Gleason et al. 2008), and with more severe prior investment inefficiency of rival firms (Durnev and Mangen 2006). 9 In addition, Xu

7 This is termed intra-industry contagious effects or intra-industry information transfers.

8 See, for example, Forster (1981), Clinch and Sinclair (1987), Pownall and Waymire (1989), Han

and Wild (1990), Freeman and Tse (1992), Ramnath (2002), Baginski (1987), Han et al. (1989), and Pyro and Lustgarten (1990).

9 Durnev and Mangen (2006) argue that the restatement signals for inefficient investment due to

erroneous assumptions about the restating firms and document that restatement-induced contagion effect can be explained by prior inefficient investment.

et al. (2006) find the contagion effect is driven by revision in the expectation of short-term future earnings of the rival firms. Overall, these findings suggest that one firm’s earnings restatements convey information useful to investors in updating stock price for other firms in the same industry.

Despite the intra-industry information transfer effects of earrings restatements are well documented, prior research provided no evidence on whether and how earrings restatements detected at one firm have valuation implications for its suppliers. This paper extends prior research by examining the stock price effects of earnings restatements on suppliers. I believe this to be the first paper to provide more precise evidence on whether and how restatement effects spread along the supply chain.

2.2.3. Vertical information transfer hypotheses

Given the significant valuation implications of earnings restatements, it seems plausible that there could be an impact on related firms in supply chain. For example, the day WorldCom announced it will restate earnings to the tune of $3.8 billion, suppliers in equipment markers such as Juniper Network Inc., Nortel and Cisco Systems Inc., experienced noteworthy crashes in their stock prices (e.g., Berman 2002). In particularly, Juniper Networks’ stock drops more than 18 percent.10 The anecdotal evidence supports the notion that earnings restatements could induce the vertical information transfer effects along the supply chain.

This vertical information transfer occurs when earnings restatements convey information useful to investors in pricing the value of related firm in the supply chain. In this paper, I consider two potential reasons for vertical information transfers: (1) earnings prospect concerns; and (2) accounting quality concerns.

Earnings Prospect Concerns

One potential reason is restatements will induce future earnings prospect

concerns about the restating firms’ suppliers, and thus alter investors’ future earnings expectation about the restating firms’ suppliers. On the one hand, the correlation in the economic activities of the restating firm and its suppliers is likely to be positive because the restating firms are important source of revenue to a supplier. With a positive correlation in the economic activities between restating firm and its suppliers, earnings restatements which convey bad news about a restating firm’s economic prospects will also convey bad news about the economic prospects of suppliers (e.g., Olsen and Dietrich 1985).

On the other hand, earnings restatements may impose spillover costs on a given supplier that has made an implicit/explicit commitment. Extant implicit contracting studies (Brown et al. 1995, Cornell and Shapiro1987, Maksimovic and Titman 1991) suggest that one firm’s financial health affects its incentives and abilities to fulfill the implicit/explicit commitments to customers and suppliers. Prior research finds that restating firms have weaker financial health than non-restating firms (Kinney and McDniel 1989; DeFond and Jiambalvo 1991; Sennetti and Turner 1999). In addition, a restating firm’s management attention and financial resource may be diverted around the litigation caused by the restatement (Palmrose et al. 2004). In these cases, the restating firm may reduce current levels of business to its suppliers, postpone the payment for suppliers, or cut corners in other ways to response litigation penalties caused by the restatement as well as to attempt to improve its financial health. Accordingly, the future earnings prospects of suppliers are perceived to be worse, such that suppliers also suffer negative stock price effects at the restatement announcement.

Accounting Quality Concerns

The second reason is that restatements detected at one firm might induce investors to question over the financial reporting quality of restating firm’s suppliers.

Recent research documents that earnings restatements prompt investors to question whether rival firms in the same industry also adopt similar accounting practices as the restating firm (e.g., Raman and Shahrur 2008). Anecdotal evidence also suggests that earnings restatements induce accounting concerns for non-restating firms. For example, comment on WorldCom’s restatement, one analyst stated that “The rotten egg here is not WorldCom and the telecom sector, but the accounting practices that are highly susceptible to interpretation” (Dignan 2002). This suggests that accounting quality concern is not restricted in the same industry as the restating firm.

In the customer-supplier relationship, accounting information plays an important role in firms’ dealing because the terms of trade are determined in part by reputation considerations. Financial image is important to supply chain partners in assessing a related firm’s reputation for explicit and/or implicit contract performance (Cornell and Shapiro 1987). Accordingly, the explicit and/or implicit claims have an effect on supply chain partners’ choice of accounting methods (e.g., Bowen et al. 1995; Burgstahler and Dichve 1997). Specifically, firms with higher implicit claims have stronger incentive to use income-increasing accounting methods (Matsumoto 2002).11 Applying this idea, I argue that the restating firm’s suppliers may have stronger incentives to use income-increasing accounting methods to signal a good financial health to the restating firm, so that they could obtain better terms of trade before the restatement. In addition, restating firm and its suppliers may collude and use similar accounting practice to manage their financial statements. Supply chain relations are potentially important information channels as investors infer value relevant information from such economic links (Cohen and Frazzini 2006). The stock prices of these stakeholders then changes as investors alter their perceptions about the

11 Matsumoto (2002) finds that implicit claims are positively related to the frequency of positive

credibility of suppliers’ past financial statements based on the information revealed by earnings restatements.

Overall, both arguments imply that earnings restatements convey the information about the economic prospects and/or accounting quality of suppliers. This leads to changes in stock prices of suppliers at the time of earnings restatement announcement. Thus, the first hypothesis, stated in alternative form, is as follows:

H1: Earnings restatement announcements will induce significant stock price

effects on suppliers of the restating firm at the restatement announcement. The focus of H1 is on whether investors update their valuation for the restating firms’ suppliers based on the information revealed by the restatements. An important issue to consider is whether such vertical information transfer is signaling future earnings prospects of suppliers. If earnings restatements have implication for future earnings prospects of restating firms’ suppliers, one should observe changes in analyst earnings forecast revisions for the restating firms’ suppliers following the restatement announcements and such revisions should be related to the information in the restatement. This suggests that investors and analysts adjust their earnings forecasts for customers and suppliers based on the news revealed by restatements of the restating firm. Examining the extent to which investors and analysts use this information provides further insights into how earnings restatements influence the earnings expectations for suppliers, thus determining stock prices of suppliers. This leads to my second hypothesis:

H2: Changes in analyst forecast revisions for suppliers following earnings

restatement announcements are associated with the information in earnings restatements.

As discussed above, earnings restatements will induce supply chain accounting quality concerns, and therefore affect the stock prices of the restating firm’s suppliers.

If earnings restatements of one firm provide information that alters investors’ beliefs about the accounting quality of the restating firms’ suppliers, one would expect that the abnormal returns of the restating firm’s suppliers surrounding restatement announcement are positively related to the measure for difference in earnings quality of the suppliers. This lead to my third hypothesis (in alternative form):

H3: Restatement-induced contagion stock price effects surrounding restatement

announcements are positively associated with cross-sectional differences in earnings quality of suppliers.

2.3. Data

2.3.1. Sample selection

I first obtain a preliminary sample of 919 restating firms that announced restatements from January 1, 1997 to June 30, 2002 as provided in Government Accounting Office Report (2002). 12 I require restating firms covered by CRSP and Compustat. To do so, I checked all of the company names after merging the GAO data with CRSP and Compustat (207 firms). Based on previous study, I then exclude financial firms (SIC codes between 6000 and 6999) and utilities (SIC codes between 4900 and 4999) (63 firms). I also exclude firms with multiple restatements (48 firms).

I next follow the approach of Fee and Thomas (2004) and Hertzel et al. (2008) to identify major suppliers of restating firms. This approach is based on the segment sales information disclosure requirement. In accordance with the Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 131, firms are required to disclose the

12 Following Gleason et al. (2008) and Wilson (2008), I use restatement firm reported in GAO (2002)

as our research sample. The database includes instances in which financial statements were not fairly presented in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAO 2002). Restatements resulting from stock splits, mergers and acquisitions, or changes in accounting principles are not included in the report. During this period, the public concern on the reliability of financial reporting and corporate governance grew, leading to the passage of Sarbanes-Oxley Act in July 2002. Thus, there was no significant shift in the legal regime during our sample period.

identity of any customer that contributes at least 10% to the firm’s total revenues.13 This customer information is available on Compustat segment files, but the database reports only the name of the customer. And, further adding to the difficulty, sometimes it reports only the abbreviated versions of the names. To link the customer name with company in the CRSP or Compustat database, I use the following procedure. First, for each firm I determine whether the customer is another company listed on the CRSP or Compustat file and I assign it the corresponding CRSP permno number. To do so, I use a text-matching program to generate a list of potential matches to the customer’s name to one of CRSP or Compustat firm. Subsequent to the text matching by computer, I hand-matched the customer to the corresponding permno number by visually inspecting customers’ name, segments, and industry information to ensure accuracy.14

Next, I use the resulting database following above procedure to identify my sample of restating firm suppliers, I identify all firms in the database that list a restating firm as a major customer in either of the three year prior to (and including) the restatement announcement year. My sample selection procedure results in a total of 88 restating firms that have at least one supplier.

For each restating firm with at least one supplier in our sample, I further confirm announcement date and the nature of the restatements. I obtain new reports form the ProQuest Newspaper database, Lexis-Nexis, and press release attached to 8-ks file with the SEC. Consistent with prior work (e.g., Hennes, et al. 2007), I exclude 9 technical restatements that do not imply an improper accounting in the original filing

13 Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 14 required firms to report certain financial

information for any industry segment that comprised more than 10% of consolidated sales or revenues between 1977 and 1997. Effective 1998, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 131 now governs required segment disclosures.

14

While some discretion is involved in visually inspecting customer abbreviation with firm identities, I am conservative in conducting visual inspection that could reduces the sample size but ensures all matches are certain.

(e.g., restatements for merges and change in principle)15. I also eliminate interim restatements that are viewed as less severe than restatement of audited annual reports (4 firms). Finally, to provide the most powerful test of hypotheses, I only focus on restatements that result from aggressive accounting practice. Thus, I drop firms that make income-decreasing restatements (6 firms). Following these screens, my final sample of restating firms contains 70 earnings restatements and I identify a total 229 individual suppliers. The distribution of restating firms and suppliers are presented in Table 2.1. The distribution of these samples over time is reported in Panel A of Table 2.1

[Insert Table 2.1 here]

Panel B of Table 2.1 reports summary information on the sample distribution by industry. Industries are as defined in Beneish et al. (2008). Panel B indicates that restating firms are widely distributed among industries, with some clustering of firms in durable manufacturers, computers, and retail industry.

2.3.2. Characteristics of suppliers

Table 2.2 shows that on average 19.8 percent of a supplier’s sales are sold to the restating firm. This result confirms that I have selected relationships where the supplier sells a substantial fraction of their output to the restating firm. The mean (median) of performance-adjusted discretionary accruals for suppliers is 0.096 (0.063). I find that smaller firms are relatively more likely to be identified as the restating firm’s suppliers.

[Insert Table 2.2. here]

2.4. Empirical results

2.4.1. Abnormal returns to restating firms and suppliers

15 The GAO database includes restatement following the adoption of SAB No. 101 “Revenue

Recognition in Financial Statements (SEC 1999). Restatements prompted by adoption of SAB No. 101 are excluded (6 firms) and the issuance of various EITF Consensuses. .

To investigate whether earnings restatements by one firm in supply chain induce vertical contagion stock price effects, I first examine the abnormal returns (CAR) to the restatement firms and suppliers. I use the date that the firm announces that it will restate earnings as the announcement date. Following prior research, I use event study methodology to estimate abnormal returns to firm i at date t (AR ) as follows: it

) ( i i mt

it

it R R

AR = − α +β (1) where R is the return on the CRSP value-weighted market portfolio on date t, mt R it

is the realized return on firms i on date t, and intercept (αi) and beta (βi) are parameters estimated using a market model. I use an estimation period from day -220 to day -21 relative to the earnings restatement date (day 0). Also, I require at least 100 trading days over the estimation window for a firm to be included in the sample. My valuation effect on restating firms and suppliers is defined as the cumulative abnormal return (CAR).

Table 3, Panel A presents cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) to restating

firms and suppliers by window type. I first present the abnormal returns to the restating firms. Consistent with prior research, I confirm that restating firms experience significant negative abnormal returns at earnings restatement announcement. For example, the mean (median) three-day abnormal return for our sample of restating firms is -10.07 (-4.76) percent.16 Consistent with the finding of Gleason et al. (2008), I also find that restating firms experience a significantly negative mean abnormal return of -3.02 percent over the nine trading days preceding the restatement announcement. My findings also confirm that there exists post-announcement stock price decline for restating firms. The mean abnormal return for restating firms is -1.95 percent over the nine trading days following the

16 The mean CAR for restating firms is similar to mean result found in other studies (range of -9.0

restatement announcement.

[Insert Table 2.3 here]

The evidence in Panel A of Table 2.3 also shows that restating firm’s suppliers suffer significant adverse stock price effects surrounding restatement announcement. The CAR to suppliers averages a significant -1.98 percent (p<0.01) for the (-1, 1)

window, -3.45 percent (p<0.05) for the (-5, 5) window. For longer window (-10, 10), the CAR to suppliers averages a significant -3.65 percent (p<0.05). In addition, we find there is evidence of information transfer from restating firms to its suppliers prior to the announcement. Subsequent to announcement day, the mean (median) abnormal return of suppliers is significantly different from zero, suggesting there is vertical information transfer between the restating firms and suppliers following the announcement.

Panel B of Table 2.3 reports the mean and median three-day abnormal returns to suppliers based on the four types of earnings restatements for each sample. 17 The first three types of restatements are based on GAO categories. In addition, following prior research’s (e.g., Farber 2005) use of the SEC’s AAERs to proxy for fraud, I also identify restatements with related SEC investigations as fraud restatements. Note that the categories with the most negative abnormal returns to the restating firms surrounding the restatement date are accounting fraud (-19.88 percent) and revenue recognition (-16.23 percent). Consistent with my prediction, I also find that suppliers experience more negative stock price effects for restatements involving accounting fraud (-3.60 percent) and for restatements to correct revenue recognition errors (-2.12 percent).

To examine how vertical supply chain effects interact with restating firms’

17 As sensitivity tests, I also use the CAR over 5-days reaction window -2 to 2 in my analysis. In the

valuation effects, this paper tests supplier stock price effects conditioning on whether restatement firms’ abnormal returns are less than or greater than median. Consistent with Wilson (2008), I use changes in stock price of restating firm at the restatement announcement as a proxy for the investor’s concern on the impact of the restatement for future earnings. I define that the more perceived severe restatements are those for which the three-day cumulative abnormal returns surrounding the restatement announcement date is below the median CAR (i.e., more negative) for the restating firms.

Table 2.3, Panel C reports evidence that supplier information transfer effects are clearly more prominent when there restating firms have a severely negative stock price reaction to earnings restatement announcement. For example, suppliers experience an abnormal return of -3.52 percent (p<0.01) for restatements in which restating firms have abnormal returns are less or equal to median. Overall, my findings provide new evidence that negative valuation effects of earnings restatement extend to suppliers.

2.4.2. Supplier contagion returns and analysts’ earnings forecast revisions

In the previous section, I report evidence suggesting that there is vertical information transfer from restating firm to suppliers surrounding the restatement announcement. To test H2, in this section, I investigate whether a restatement by one firm in the supply chain conveys new information about the future earnings prospects of the restating firms’ suppliers. If earnings restatements by one firm in the supply chain induce economic prospect concern, the news in earnings restatements will affect analysts’ EPS forecast for suppliers, and if so, earnings forecast revisions will be related to the information provided by the earnings restatement announcement. To test this conjecture, I analyze earnings forecast revisions for suppliers following the announcement. I measure analyst annual EPS forecasts

revisions by subtracting the mean EPS forecast outstanding 60 days after the restatement from the mean EPS forecast on day -1 before the announcement day.

[Insert Table 2.4 here]

Panel A, Table 2.4 supports that mean analyst forecasts for suppliers decline significantly subsequent to the earnings announcement. This decline is statistically different from zero at the 5 percent significance level. Panel B of Table 2.4 reports the relation between changes in analyst EPS forecast revision and severity of earnings restatements. Using Pearson correlation analysis, I find that analyst earnings forecast decline is significantly associated with more negative abnormal returns to restating firms (ARRE) and more negative abnormal returns to suppliers (CAR). These results

support the notion that restatements convey new information bout deteriorating economic of suppliers. In addition, earnings forecast revisions are associated with fraud restatements (more negative forecast revisions for restatement involving accounting fraud) and revenue restatements (more negative). I attribute downward revisions in analyst earnings forecast for suppliers to that the restating firm is important source of revenue to suppliers.

Overall, I find the evidence suggests that the investors and financial analysts revise their expectation of earnings to suppliers downward following restatement announcement. This is support the notion that restatements signal information which affects the market participant’s assessments of the distribution of future earnings expectation of the restating firm’s suppliers.

2.4.3. Supplier contagion returns and accounting quality of suppliers

Empirical Model

The main objective of this section is to test whether restatement-induced supply chain contagion stock returns are related to proxy for earnings quality of suppliers and customers.

To test accounting quality concern, I use performance-adjusted discretionary accruals to proxy for suppliers’ earnings quality (denoted by DA). Following Hribar

and Collins (2002), I use the direct approach to compute the total accruals (TACC). I

estimate a modified Jones model (Dechow et al. 1995) on a cross-sectional basis for each Fama and French (1997) industry with 20 or more firms in year t:18

ε β

β

α + Δ −Δ + +

= (1/ ) ( / / ) ( / )

/A A 1 SALES A REC A 2 PPE A

TACC (2)

Where TACC equals to operating income less operating cash flows adjusted for

discontinued operations and extraordinary items; A is total Assets at the end of year

t-1; ΔSALES is change in sales for firm i in year t; ΔREC is change in accounts

receivable for firm i in year t; PPE equals property, plant and equipment for firm i in

year t.

I compute the performance−adjusted discretionary accruals based on Cahan and Zhang (2006), an alternative approach to control for companies’ performance effect. That is, for each Fama and French (1997), I divide my sample into deciles based on sample companies’ return on assets (ROA). I then adjust each discretionary accrual

estimated from Equation (2) by subtracting the median discretionary accruals for the firm’s industry-ROA deciles.19 I predict that supplier chain effects are related to performance-adjusted discretionary accruals.

In addition to capturing whether earnings restatement trigger investors to concern the accounting quality of other firms in supply chain, I also consider factors that extant literature suggests might lead to cross-sectional variations in the nature and extent of supplier and customer contagion. I first consider the severity of the restatement. The abnormal returns to the restating firm capture the information in the

18 Following prior research (e.g., Kothari et al. 2005; Cahan and Zhang 2006), I winsorize all

distributions to the 1st and 99th percentiles in estimating Equation (2).

19 This approach does not impose linearity on the relation between accruals and the performance

restatement (Durnev and Magen 2008). I include the restating firm’s three-day abnormal stock return (ARRE) to control for differences in investor perceptions of the

severity and importance of the restatement and related information in the announcement. Given the underlying economics of the relationship between suppliers and the restating firms, one would expect to observe the coefficient on ARRE is

positive.

I also consider that the economic bond between the restating firm and its suppliers. The literature suggests a vertical information transfer between two firms increase with their correlation in economic activities (Pandit et al. 2007; Olsen and Dietrich 1985). Applying this notion, I expect that suppliers will suffer more pronounced supplier contagion effects when suppliers’ economic activities are more dependent on the restating firm. To measure the strength of economic bond between the restating firm and its suppliers (DEPENDCENC), I use the percentage of sales

made by a supplier to the restating firm to assess the how reliant the supplier is on the restating firms for sales revenues.

Prior studies have viewed alliance as a form of relationship-specific investment by suppliers (e.g., Fee et al. 2006; Raman and Shahrur 2008). When suppliers invest in more relationship-specific investments to doing business with the restating firm, the more implicit/explicit claims held by customers and suppliers depend on the restating firm. Specifically, this variable captures the presence of specific contracts between the restating firm and its suppliers and customers. Thus, my second proxy for economic bond is alliance agreement. I expect that suppliers with alliance agreement with the restating firm will suffer pronounced supplier contagion. To gather information on alliances, I search for whether the restating firm and its suppliers were listed together in the Securities Data Corporation (SDC) strategic alliance database. I define ALLIANCE as a dummy variable that takes a value of one

if the firms in a relationship had a formal alliance agreement with the restating firm over three years before earnings restatement and zero otherwise.

Prior research documented that supplier power have an effect on suppliers by influencing the term of trading contracting. For example, restating firm relies on a larger suppler for its product as alternative source is not available or large enough. Thus, I expect that larger suppliers suffer less negative stock price effects at the time of earnings restatement announcements. Following prior research, I measure the degree of concentration of the restating firm by the sale-based Herfindahl index

(HERFINDAHL), which equals the sum of the squared fraction of industry sales by

all firms in the industry.

To mitigate problems of potentially omitted correlated variables, I include several variables into my cross-sectional regression to control for the characteristics of the restating firm, customers, and suppliers that might affect contagion stock returns to customers and suppliers. Other information transfer studies have indicated that the size of the restating firm may have an impact on stock returns (e.g., Gleason et al. 2008). Thus, I add RESIZE, the natural log of total assets, into the regression.

The supplier long-term debt and debt in current liabilities divided by total assets

(LEVERAGE) is used to control for the potential impact of financial leverage on

abnormal returns to suppliers at the restatement announcement date (Hertzel et al. 2008). I also consider the effect of suppliers’ firm size on the contagion effects (SIZE). CFS, sales to cash flows ratio, enters the regression is to control the profitability of

suppliers. Finally, Book-to-market ratio (BM) is to control for suppliers’ growth

opportunity.

In summary, to conduct my main tests of accounting quality concern argument, I estimate Equation (3) for suppliers:

ε CFS BM SIZE LEVERAGE β HERFINDAHL RESIZE β COST REVENUE FRAUD ALLIANCE DEPENDENCE DA ARRE CAR + + + + + + + + + + + + + + = 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 β β β β β β β β β β β β (3)

Where CAR is the restatement-induced contagion stock returns to suppliers

during the three-day event period (-1, 1) surround the restatement announcements, the

independent variables are as described above, and ε is a random disturbance term. Empirical Results

Table 2.5 presents cross-sectional analysis of the three-day abnormal returns of the restating firms’ suppliers.20 The results reported here use individual firm observations although the portfolio regressions yield similar conclusions.21 The

t-values are computed with heteroskedasticity consistent standard errors if the tests

reject homoskedasticity at the 10% significance level (White 1980). 22 To conduct my analysis, I winsorize all the dependent and independent variables at the 1st and the 99th percentiles in order to reduce the effect of outliers on my results.

[Insert Table 2.5 here]

In Model 1, the results show that the coefficient of ARRE is significantly

positive, after including other potentially important variables in the regression.23 This result is anticipated from the results shown in previous section. The supply chain effects are more severe for restating firm that have larger negative abnormal returns around the restatement announcement. The finding supports the notion that the extent of the announcement effects on suppliers are significantly influenced by the extent to which the restatement valuation effects on the restating firms.

20 The results of the analyses for the 21-day abnormal returns are qualitatively similar to the results

in this section.

21 Examining individual supplier firm, as opposed to supplier portfolio, allows me to test the

importance of firm-specific variables in explaining the cross-sectional variation in abnormal returns to suppliers (as in Gleason et al. 2008 and others).

22 The samples in Table 4 are smaller because of financial data unavailability.

23

Variance inflation factor diagnostic statistics do not indicate multicollinearity as a problem (VIFs are less than 2.0).

As prediction, suppliers with high performance-adjusted discretionary accruals experience a more pronounced contagion stock price decline. This supports my hypothesis H3. The coefficients on DA are negative and significant, indicating that

suppliers that have higher performance-adjusted discretionary accruals experience a more pronounced contagion stock price decline than do low-accruals firms. This finding supports the notion that earnings restatements provide useful information that alters investors’ perceptions about the financial reporting credibility of restating firms’ suppliers.

In all models, I add three variables related to types of restatements. As in the univariate results, I find that restatements of accounting fraud are associated with more negative supplier contagion stock returns. Consistent with prior research, my results support the notion that accounting fraud have more negative implications for restating firms’ accounting quality, which in turn increases perceived risk/uncertainty for suppliers and so will induce more severe supply chain contagion effects on suppliers. However, I fail to find significant evidence that REVENUE and COST have any effect on abnormal returns of suppliers after controlling for ARRE

and FRAUD.24

Note that as reported in Model 1, accounting fraud increases perceived risk/uncertainty for suppliers and so is associated with more negative supplier contagion stock returns. Thus, I add an interaction between accounting fraud and performance-adjusted discretionary accruals (FRAUD*DA) into regression model. If

the fraud restatements are more likely to prompt investors to question over the suppliers’ accounting quality, then I expect a negative coefficient on the interaction terms. In Model 2, I present the coefficient on the interaction between the proxies for

24 Consistent with prior research (e.g., Palmrose et al. 2004), the result in model 2 suggests a

meaningful association between fraud and revenue recognition restatement. I find the correlation between fraud and revenue recognition restatement is positive and significant (p-value<0.01).

earnings quality of suppliers and the accounting fraud. The evidence in Model 2 indicates negative and significant coefficients on the interaction term. This suggests that restatements involving accounting fraud are likely to cause greater concern about the credibility of financial information of restating firms’ suppliers.

To further explore the relation between accounting quality of suppliers and restatement-induced supplier contagion returns, this paper examines that whether contagion stock price effects are more pronounced when restating firm and suppliers use the same external auditor, identify the restating firm’s auditor for the fiscal year before the restatement is announced. Approximately 21 percent of the suppliers in my sample use the restating firms’ auditor. Thus, I add a common-auditor indicator variable (COM_AUDITOR) and an interaction between common-auditor indicator

variable and performance-adjusted discretionary accruals into regression model. In Model 3, I present the coefficients on the interaction between the proxies for earnings quality of suppliers and the common-auditor (COM_AUDITOR*DA). I find

that contagion stock returns are negatively related to the incremental effect of DA

when suppliers and the restating firms use the same auditor. This suggests that investors seem to impose an incremental contagion penalty on suppliers with high discretionary accruals when the supplier and restating firm employ the same extern auditor.

The coefficient on DEPENDENCE is negative and significant in Model 1,

supporting my prediction. This variable measures how reliant the suppliers are on the restating firms for sales revenues and, hence, supplier switching costs. The more dependent the supplier is on a restating firm the more negative will be the supplier’s stock price reaction to the earnings restatement announcement. This evidence suggests that the stock market reaction to earnings restatement announcements takes into account the economic activities that relate suppliers to the restating firms. In

addition, I also find the coefficient on ALLIANCE is negative and significant,

suggesting that suppliers have a formal alliance agreement with the restating firm suffer more negative contagion stock price effects.

However, there is no evidence to suggest that the concentration of supplier

(HERFINDAHL), leverage (LEVERAGE), restating firm size (RESIZE),

book-to-market ratio (BM) and cash flows to sales ratio (CFS) are relevant to

determine supplier contagion stock returns.

2.5. Robustness checks and sensitivity tests 2.5.1. Industry-level information transfer effects

Using firm level analysis, in previous sections I have found that there are significant vertical information transfer effects for the restating firms’ key suppliers at firm level. There are at lease two reasons to expect that other firms in suppler industries could be affected by the information event of the restating firms. First, firms in the supplier industries could be potential suppliers of the restating firm even if not identified in SFAS No. 131 disclosures (Raman and Shahrur 2008). Second, earnings restatements announcements by a restating firm may reflect supply chain industry-wide economic prospects, and so other potential supplier firms in these industries could also suffer contagious effects of earnings restatements. To measure contagious effects on supplier industries, I use all firms with the same four-digit SIC code in my supplier industry as potential suppliers.

[Insert Table 2.6 here]

The results in Table 2.6 show evidence that restatement-induced contagion effects spread beyond key suppliers to their respective industries. Panel A of Table 6 shows that supplier industries suffer negative and significant three-day abnormal returns (-0.96 percent). The results in Panel B indicate that supplier industries suffer negative and significant abnormal returns for the subsample of restatement sample in

which restating firms are with abnormal returns less than sample median. My industry level analysis shows that vertical information transfer spread beyond suppliers to firms in their respective industries. As suggested by Bernard (1985), this industry effects could be attributes to earnings restatements convey information with industry-wide implications for potential suppliers, regardless of the existence of firm-to-firm contracts, thus affecting all suppliers in a major supplier industry.

2.5.2. Restatements with negative valuation effects

To do a robustness check, I also exclude restatements that did not result in negative stock price effects on the restating firms. I focus only on restatement with negative valuation effects. The mean (median) three-day abnormal returns to suppliers is -2.73 (-0.79) percent (p-value<0.01). Overall, I find evidence that vertical information transfer effects improved when I focus on restating firms that have negative stock price reaction to earnings restatement announcement.

2.5.3. Alternative measure of accounting quality

To do a robustness check, I also use alternative measure to capture whether restatement announcements cause investors to question over the suppliers’ accounting quality. As a form of monitoring, auditing mitigates incentive problems between managers and outsiders (Butler et al. 2004). Specifically, the auditor plays an important role in determining whether the financial statements include a material misstatement or departure from GAAP. Thus, prior research has viewed audit opinions as a good measure for a firm’s financial reporting quality. For example, extant research finds that modified audit opinion is positively associated with abnormal accruals (Francis and Krishnan 1999; Bartov et al. 2002; Butler et al. 2004). Thus, I predict that the coefficient on modified audit opinions is negatively associated with contagion stock returns, suggests that suppliers with modified audit opinions suffer more negative stock price effects at the time of restatement

announcement.

The auditor opinion data is from Compustat database. Under the SAS 58 regime, Compustat code 2 opinions include only qualifications for scope limitation and departures form GAAP. Other modifications, such as changes from one generally accepted accounting method to another and material uncertainties, should be classed as unqualified opinion with explanatory language (Compustat code 4). Following the approach of Butler et al. (2004), I define modified audit opinion

(OPINION) as suppliers with a qualified opinion or unqualified with explanatory

language and zero otherwise.

The coefficient on OPINION are negative and significant (Coef = -0.097, t-value= -2.52), indicating that suppliers that have modified audit opinions before

the restatement announcement experience a more pronounced contagion stock price decline than do firms with clear auditor opinion. This finding further confirms the idea that earnings restatements provide useful information that alters investors’ perceptions about the accounting quality of restating firms’ suppliers.

2.6. Summary

This paper is to investigate whether and how information released by earnings restatements affects the valuation of the restating firm’s suppliers. Using event study, I find suppliers suffer negative stock price effects surrounding the restatement announcement. This supply chain contagion effect is more prominent for earnings restatements that result in a more negative abnormal return to restating firms around restatement announcements and for restatements that involve revenue recognition errors and accounting fraud. Information in earnings restatements is found to induce investors to worry about suppliers’ future earnings prospects. I find a significant downward revision in suppliers’ earnings forecasts following the restatement, which is positively correlated with the market reaction to earnings restatements. More

importantly, I find that suppliers suffer more stock price decline when they have high performance-adjusted discretionary accruals, suggesting supplier contagion effects can be attributed to investors’ concerns over suppliers’ accounting quality. Overall, my findings suggest that earnings restatements induce restating firms’ suppliers facing increasing concerns about earnings prospects and accounting quality, and affect the stock prices of these firms.

Table 2.1

Sample distribution Panel A: Sample distribution by year

Year Restating firms Suppliers

1997 4 5 1998 10 22 1999 13 40 2000 10 63 2001 24 78 2002 9 21 Total 70 229

Panel B: Sample distribution by industry

Industry Restating firms Suppliers

Mining and construction 1 1

Food 5 9 Textiles 1 1 chemicals 2 3 Pharmaceuticals 1 1 extractive 3 5 metal 1 1 Machinery 2 7 Electrical equipment 10 37 transportation 4 8 instruments 5 13 computers 16 68 wholesale 6 26 miscellaneous retail 10 37 restaurant 1 4 services 2 2 Total 70 229

Panel A presents the distribution of restating firms and suppliers by years. Panel B reports the distribution of restating firms and suppliers by industry. Suppliers are identified through SFAS No. 131 disclosures and this information is available on COMPUSTAT Segment file. The first column shows the number of restating firms that have at least one supplier. The second column reports the number of suppliers of the restating firms at individual firm level. Industries are defined in Beneish et al. (2008).

Table 2.2

Characteristics of suppliers

Variable Mean Median 75

th

Percentile

25th

Percentile Standard Deviation

ARRE -0.127 -0.053 -0.006 -0.105 0.141 DEPENCENCE 0.198 0.157 0.236 0.119 0.153 ALLIANCE 0.285 0.091 1.000 0.000 0.501 RESIZE 9.481 8.882 9.809 10.434 1.485 DA 0.096 0.063 0.121 0.042 0.161 HERFINDAHL 0.194 0.166 0.253 0.084 0.147 SIZE 5.009 3.963 4.798 5.743 1.677 LEVERAGE 0.212 0.143 0.336 0.007 0.249 BM 0.419 0.128 0.413 0.617 0.387 CFS 0.544 1.000 1.000 0.000 0.499

ARRE= the three-day abnormal returns to the restating firms; DEPENDENCE= supplier sales to

restating firm divided by suppliers’ total sales; ALLIANCE =a dummy variable that takes a value of one if the restating firm and its suppliers had a formal alliance agreement preceding the year of earnings restatement announcement and zero otherwise; DA= the absolute value of performance-adjusted discretionary accruals of suppliers before the restatement announcement;

HERFINDAHL = the Herfindahl index of the suppliers; RESIZE = the natural logarithm of restating

firms’ total assets in restatement announcement year; LEVERAGE= total debt divided by total assets of suppliers at the end of the fiscal year before the restatement announcement; SIZE=the natural logarithm of suppliers’ total assets; BM = suppliers’ book value of equity divided by equity market value at the end of the fiscal year before the restatement announcement; CFS= operating cash flows to sales of suppliers at the end of the fiscal year before the restatement announcement.