*本篇論文通訊作者:黃善華,通訊方式:shwang@twu.edu。

青少年對父職與母職的行為認知

黃善華

美國德州女子大學家庭學系副教授摘 要

ώࡁտўдᒢྋܦ͌ѐ၆ͭᖚϓᖚҖࠎ۞ᄮۢனڶĄࡁտଳפયסአߤ ڱĂֹϡFine et al., (1985) Ꮠ̄ᙯܼયסĄଳפ 291 Ҝέ៉Δొ۞ܦ͌ѐ̈́ 231 Ҝ઼࡚ڌΔొ۞ܦ͌ѐүࠎᇹώĂซҖ̙࣎Т̼͛гડ۞ܦ͌ѐ၆ͭᖚ ᄃϓᖚҖࠎᄮۢ۞ࡁտĄࢋࡁտඕڍт˭Ĉ ˘ă ͭᏐҖࠎᄃܦ͌ѐᙯܼᓁࣃᇴፂЯ઼ᚱ̙ТѣពᙯܼćϓᏐҖࠎᄃܦ ͌ѐᙯܼᓁࣃᇴፂ̙Я઼ᚱّٕҾயϠព ˟ă έ៉Δొշّܦ͌ѐ۞ᇹώᄃ઼࡚ڌΔొշّܦ͌ѐ۞ᇹώ၆αีͭᖚ Җࠎѣពّ۞ᄮۢमளĂέ៉Δొշّܦ͌ѐੵ˞၆ͭᏐ۞ޤঈၹ ࢬĂдϒࢬଐຏܑ྿఼ᄃͭᏐણᄃ۞ᄮۢ˯ӮҲٺ઼࡚շّܦ͌ѐ۞ ෞҤĄ ˬă ઼࡚۞ّ̃ܦ͌ѐྵέ៉۞ّ̃ܦ͌ѐдϒࢬଐຏܑ྿ᄃ఼ีͭᖚ Җࠎѣពّ۞ᄮۢमளĄ αă ੫၆ϓᖚҖࠎᄮۢෞҤĂ઼࡚۞շّᄃّ̃ܦ͌ѐ၆ϓᏐϒࢬଐຏܑ྿ ᄃ఼Ăͧέ៉۞շ̃ܦ͌ѐѣϒࢬ۞ᄮۢෞҤąѩमள྿זពड़ ڍĄ ޢĂֶፂ˯ඕኢ, ࡁտ۰೩វޙᛉĂүࠎͭϓᏐăछलϠ߿ିֈ रăۤົ࠹ᙯಏҜ̈́Ϗֽࡁտ̝ણ҂Ą 關鍵字:ܦ͌ѐᄮۢăͭᖚᄃϓᖚҖࠎăᏐ̄ᙯܼયסAdolescents’ Perceptions of Paternal and Maternal Behaviors:

An Exploratory Study

Introduction

The family itself is widely considered to be a crucial social context for the development of long-term well-being for children (Wenk, Hardesty, Morgan, & Blair, 1994). More importantly, children’s relationship with their parents plays a significant part in their lives, especially during the early stages of development. These perceptions are highly related to their experiences with parents through various interactions. According to Belsky (1984), various forces may vary the quality of parenting behaviors to a certain extent (i. e., marital conflict, financial stress). Therefore, the type of influences generated by parents on their children may be associated with the quality of child development.

In the past, research on parenting in the U.S. predominately used middle-class, white respondents. Furthermore, parenting was equivalent to mothering (Stevenson-Hinde, 1998) which excluded the significant contribution and influences made by fathers. Milkie, Simon, and Powell (1997) further argued that many studies of family roles and relationships are still adult-centered. Limited research has focused on adolescents’ perception of parental roles from other ethnic groups. Even if research attempted to examine multiple perspectives on parental behaviors, not surprisingly, research would suggest that a low agreement between parents and children on parental behaviors has been documented (Smith & Morgan, 1994; Tein, Roosa, & Michaels, 1994; Plunkett, Behnke, Sands, & Choi, 2009).

Parenting a child presents challenges as each child is different who is exposed to distinct learning experiences in various social contexts. In addition, each child is going through developmental changes and requires needs that are different from the previous stage (Putnick, Bornstein, Hendricks, Painters, Suwalsky, & Collins, 2008). During childhood, a great amount of physical care is needed from adults to enhance proper development and physical safety (Maccoby, 1992). However, adolescence is a stage which physical care and constant monitoring may not be as crucial as it was during the early childhood stage. Less frequent interaction, power shifts, and increased conflict mark typical parent-adolescent interaction (Putnick et al., 2008). Adolescents, on the other hand, require many families to make significant changes in their interactions with

one another (Seiffge-Krenke, 1999) to adapt to changes that associate with the development of adolescents. It is also a period that marks the transitions from childhood to adulthood with a number of inevitable physical, emotional, and interpersonal challenges (Wolman, 1998). Oftentimes, many struggles and problems for adolescents are to secure a balance between the dependence on their parents during the childhood and the independence on their own abilities in adolescence to reach physical and socio-emotional maturity. Hines and Paulson (2006) proposed that parents’ perception of storm and stress during adolescence is highly linked to the level of parental responsiveness. Possibly, the way in which an adolescent perceives his or her relationship with either parent differs from the way the parents approach their relationships with the developing adolescent whose development may be strengthened or impaired during this stage. However, the association between positive parenting behaviors and child well-being has been identified in various studies (Amato & Rivera, 1999; Mosley & Thomson, 1995). Furthermore, adolescents’ perceptions of positive parental influence in their lives have been found to be correlated with adolescents’ positive psychological well-being (Clark & Barber, 1994; Khaleque & Rohner, 2002) and conduct and psychosocial development (Gray & Steinberg, 1999; Plunkett, Behnke, Sands, & Choi, 2009).

In a collectivistic society such as Taiwan, most families highlight the importance of family unit than the individual wellbeing when approaching family life compared to the Western families (i.e., America) that highly emphasize independence and autonomy of each individual family member (Coles, 2006). In Taiwan, roles and responsibilities in a family are typically assigned from a hierarchical system that is generally based on gender, age, and social class (Huang, 2005). A great emphasis is typically placed on harmonious interpersonal relationships through interdependence, loyalty, and conflict avoidance; personal dreams and development are sacrificed to maintain family harmony. For example, couples in a more traditional Asian family typically place the wellbeing of the husband and his family members above and beyond her own needs and wellbeing (Adler, 2003). This type of family interactions differs from that of America which may explain partially the uniqueness of parent-child relationships. In a traditional Asian family, the mother typically assumes the roles of nurturance and support whereas the father’s role rests heavily on discipline (Lee & Mock, 2005). Taking the cultural practices exerted by mother and fathers in an Asian culture (i. e., Taiwan), it may be highly possible that a developing adolescent finds an imbalance distribution of roles between mothers and fathers.

Studies in regard to parent-child relationship in other cultures commonly suggest that unique dynamics have been found in terms of how resources are allocated, power delegated, and responsibilities relinquished. Children growing up in a collective culture are generally expected to honor and conform to group norms, relational harmony, and the family well-being (Chao, 1994; Mbito, 2004). As a result, parents may emphasize more on control and monitoring when interacting with their children. Conversely, collectivistic societies may place less emphasis on parent-child interactions and closeness. Therefore, children’s perceptions of parental behaviors from at least two geographical areas in different cultures appear to be a reasonable step to take in understanding of parental behaviors. On the other hand, an individualistic society such as America emphasizes individual autonomy and emotional expressions of feelings. An individualistic society is typically characterized by the core values of self sufficiency, individualism, and independence (Hess & Hess, 2001). In such society, individuals are encouraged to pursue independence and autonomy so that they will not depend on each other. As a result, parents are expecting their children to move out and become independent by the age of 18. This would be something that parents would stress (Webb, 2001). On the other hand, children in such cultural beliefs also tend to be encouraged to build interpersonal relationships through the display of affection, communication, and emotional expression. In many cases, the needs of an individual oftentimes are equally taken care of as to that of the family unit. Contrast to Asian families, American family has been characterized as “child-centered” structure that parents seek children’s opinions and involve them in decision making process. Evident in such culture, parents are encouraged to actively engage themselves in the lives of their children. Although storm and stress is an apparent stage, active communication and affection expression are highly promoted. Therefore, the overall perceptions of teens from an individualistic society may be more positive compared to their counterparts in a collectivistic society.

The linkage between parental support and adolescent adjustment has been established. Henry, Robinson, Neal, and Huey (2006) proposed that positive parental support increases teens’ general competence, self-esteem, academic performance, and family life satisfaction. Parental supportive behaviors and interactions have been found to facilitate the development of teens’ self esteem in countries such as Russia, China, and America (Bush 2000; Bush, Peterson, Cobas, & Supple, 2002). A supportive model of fathering behaviors refers to a father’s voluntary investments of himself in helping children to develop positive

knowledge and skills in order to face challenges in adolescence (Palkovitz, 1997). Interestingly enough, it appears that fathers are more likely to initiate nurturing behaviors when it is made clear that such behaviors will make a significant difference in the lives of their children (Simons, Johnson, & Conger, 1994) whereas mothering is not linked to the appraisal of their behavior done to children. Supportive fathering behaviors are more likely to establish good father-child relations and also decrease the likelihood of developing behavioral problems of children without taking peer relations and antisocial behaviors into account (Coughlin & Vuchinich, 1996). Adolescents who perceive their overall family functioning to be marked by warmth, closeness, and flexibility also viewed their parents as supportive (Henry, Robinson, Neal, & Huey, 2006). Parental warmth, flexibility, and emotional closeness provide a strong sense of psychological stability that becomes a crucial protective factor in the midst of changes happen to adolescents. Conversely, adolescents are detrimentally influenced by parental rejection and neglect (Berndt, 1996) that may confuse their pursuit of self identity. Furthermore, the likelihood for children raised in high conflict and aggressive families to demonstrate negative and aggressive behaviors toward others is significantly higher than for those who were raised in a minimal hostile or negative family environment.

On the other hand, mothers have historically assumed or been given the role of care giving responsibilities at home, particularly during the formative years of young children (Bigner, 2006). In the recent years, a substantial increased number of women participate at the work force continuously both in Taiwan and the U.S. This directly limits their available time to invest at housework. However, it is still expected that mothers are the ones who display nurturance and affection toward family members based on cultural beliefs. This is particularly true in Asian families that mothers heavily invest their time in caring for children and other family members (in-laws in some cases) above their own needs and career opportunities. On the other hand, most mothers in the U.S. are culturally socialized to help their children develop a self-sufficient, independent identity (Hess & Hess, 2001) so that each child will be able to pursue his or her autonomous, independent lifestyle. In particular, mothers will attempt to assist their teenage children during the identity formation stage to develop skills for independence and autonomy that are important in adulthood (Hamner & Turner, 2001; Webb, 2001). Their primary role is clearly prescribed within the nuclear family structure that mostly does not involve other extended family members who reside in the same household on a regular basis. In an international study of

parenting in multiple countries, mothers in seven countries found satisfaction with parental roles (Stevenson-Hinde, 1998). The likelihood remains high for the appraisal of mothering which is solely based on her abilities to provide care for the entire household. Unfortunately, the quality of mothering could be affected by many factors. Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, and Wierson (1990), examining the role of disrupted mothering on the relationships between marital conflict and poor adolescent adjustment, found that the role of disrupted mothering functioned as a mediator between marital conflict and poor adolescent adjustment with adolescents from intact families. Also, distress experienced by either spouse in a marital relationship may sensitize each to an increased use of anger and conflict (Cummings & Davies, 1994). In fact, mothers who may not intentionally display negative emotions or behaviors toward their children can be indirectly affected by poor marital quality and high conflict level with their spouse. Consequently, the increased use of hostile arguments or physical aggression might become common solutions to deal with interspousal problems, which may influence poor adolescent adjustment by altering the quality of parenting behaviors.

Lerner et al. (1996) proposed that the stage of adolescence involve multiple changes that happen at both the individual and contextual levels, requiring adolescents to experience new challenges that might put the adolescent at risk. At the individual level, for example, adolescents experience biological changes that could affect the way they view themselves either positively, negatively, or with mixed perceptions altogether. At the contextual level, their relationships with parents and peers change in terms of the amount of time spent with each. Typically, the amount of time that is spent with parents or other families may be significantly reduced. Adolescence is a time for children to experiment with their interpersonal skills in building relationships with others, particularly with their own parents. Parental rejection and neglect provide them with minimal to no constructive information on how to establish proper interpersonal relationships with others which are conducive to optimal social life and a preparation for intimate relationships in adulthood.

Almeida and Galambos (1991) suggested that engaging in activities with children through supportive fathering behaviors might promote healthy emotional development in children. This is highly promoted and encouraged to fathers in the western societies such as America. Constant exposure to a non to low distressed family environment regardless of cultural context is positively linked to the emotional well-being in adolescents who tend to be in a better position when trying to establish other intimate relationships outside of familial context.

Moreover, supportive fathering behaviors such as father’s time, supportiveness, and his close relations with children were all negatively associated with children’s problem behaviors (Amato & Rivera, 1999; Noller, 1997). It has been suggested that some mothers play a gate-keeping role between father-child relationships (Allen & Hawkins, 1999). Mothers’ beliefs and attitudes about the influence of the father toward her children are associated with how often she may encourage fathers to engage children in various activities. When she believes that the level and type of involvement from the child’s father has great potential to make positive influences on her children, she tends to relinquish time and opportunities to allow them happen more frequently. Conversely, mothers, the gatekeeper, will manage to limit the quantity of time and his involvement with her children.

Although active father involvement with their children is encouraged, many men still assume their main familial responsibility through financial provision. Many children in the U.S. are involved in extracurricular activities (i.e., sports), some fathers (also mothers) take advantage of the opportunities to be present at sports events. This is a culturally specific context which is preferred by children. It directly provides an avenue for regular interactions. However, many teenagers in Taiwan heavily invest their time in education which does not afford fathers time and a preferred context to interact with their children. Father-child relationship can be distant, particularly for many Asian fathers who work long hours which limit their ability to interact with children. Physical fatigue, job-related stress, and low in father-child communication further distance their relationship with children.

When fathers are under stress (particularly economic stress), increased negative fathering behaviors are likely to occur (Peterson & Hawley, 1998). In this circumstance, fathers tend to perceive their teenage children to be difficult to interact with (Simons, Johnson, & Conger, 1994) whereas mothers’ perceptions of children differ from fathers when under chronic stress. In addition, negative fathering behaviors may begin to emerge when marital conflict and economic hardship are increasing (Harris, Furstenberg, & Marmer, 1998; Papp, Cumming, & Goeke-Morey, 2009). On the other hand, mothers tend to redirect their time and energy toward children when marital conflict remains as a problem. Mothers in general tend to have a better skill to differentiate her marital problem from parent-child relationships. Almost all studies in the literature strongly suggested that negative fathering behaviors create detrimental effects on children. Adverse disciplinary behaviors employed by fathers seemed to implicitly send a message to

adolescents by silently allowing them to utilize aggressive, negative modes of behaviors while interacting with others. This might lead them to encounter accumulated difficulties with peers who hold a negative view about aggressive behaviors. Specifically, paternal harsh discipline was correlated significantly and negatively with conduct problems of children (Wagner, Cohen, & Brook, 1996), especially for sons (Hosley & Montemayor, 1997). As a direct result, hostile fathers were more likely to have acting out children (Elder, Conger, Foster, & Ardelt, 1992). Thus, adolescents will increasingly exhibit maladjustment problems when negative fathering behaviors are present in a familial context with financial stress and interspousal conflict. In this case, positive influence both in emotional and social aspects exerted by mothers may serve as protective factors to buffer negative effects displayed by fathers when the quality of father-child relationship seems rough. This means that relationship between teens and their mothers and quality of communication provide a haven for children who experience relational problems within and outside the family. Therefore, teens’ perceptions of paternal and maternal behaviors can shed some light on how they appraise fathering and mothering behaviors during their adjustment in adolescence stage.

The purpose of the present investigation was to better understand adolescents’ perceptions of parental behaviors from two different geographic areas. In particular, the study assessed whether subject’s country of origin and gender of the subject affected adolescents’ perceptions of parenting behaviors. It was hypothesized that male and female adolescents as well as adolescents from two different cultural contexts would perceive their parenting behaviors differently.

Method

The sampling in this study was based on convenience sampling. Participants of this sample in Taiwan were 291 adolescents recruited who were middle and high school students in the northern part of Taiwan. Students who participated were from three classes in a middle school and three classes in a high school. This sample consisted of 163 (56%) males and 128 (44%) females. The age ranged from 12 to 18 years and the mean age of the participants was 14.6 years, with a standard deviation of 1.4 years. Participants of this sample in the U.S were 231 adolescents recruited from three classes in a middle school and 3 classes in a high school in the mid-Atlantic states. In this region of America, students begin middle school education at age 11 which is the sixth grade. This sample consisted of 125 (53%) males and 106 (47%) females. The age ranged from 11 to 19 years

and the mean age of the participants was 14.7 years, with a standard deviation of 1.9 years.

Instruments

The questionnaire consisted of two paper and pencil instruments which are used. However, each one will be used for analysis in this study which is described below.

Parent-Child Relationship Survey (PCRS). The first instrument administered

was the 48-item Parent-Child Relationships Survey (Fine, Moreland, & Schwebel, 1983). This scale assesses, on a 7-point Likert scale, participants’ perceptions of their relationships with their parents on a number of dimensions. These consist of: perceived level of father involvement; positive affection; maternal role; perceived parental identity; anger toward parents; communication with parents; and influence of parents in the child’s life. This survey is comprised of two 24-item scales, the Father Scale and the Mother Scale. According to Fine, Worley, and Schwebel (1985), each scale is primarily unidimensional, assessing a positive affective dimension. 4 scales were created to capture domains of perceptions of fathering (positive affection, father involvement, communication, and angry at father) whereas 4 scales for domains of perceptions of mothering. This survey is designed to measure perceptions of older children and could work effectively when measuring teenagers (Fine, Worley, & Schwebel, 1985).

Demographic questionnaire. Participants completed a demographic

questionnaire which included questions about their sex, age, religion, grades, socioeconomic status, parents’ age, education, and job.

Results

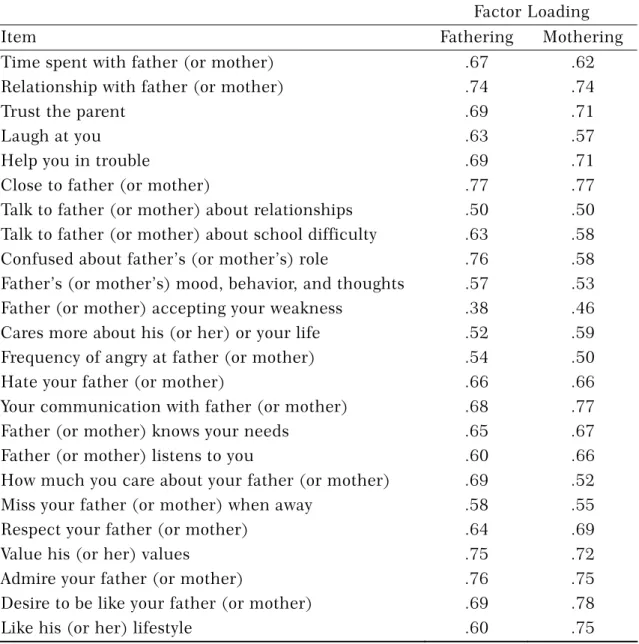

Factor analysisI performed a series of item and factor analyses to provide evidence for sound psychometric characteristics, factor variance, and internal consistency. With each step, each item loaded a factor with a minimum loading of .40 which can be located in Table 1. Only one item that almost reach .40 (father accepting your weakness) is present. Since this is an exploratory study, I decided to keep this item.

Table 1. Item Factor Loadings for Parent Child Relationship Survey for perception of fathering and mothering (N = 522)

Factor Loading

Item Fathering Mothering

Time spent with father (or mother) .67 .62 Relationship with father (or mother) .74 .74

Trust the parent .69 .71

Laugh at you .63 .57

Help you in trouble .69 .71

Close to father (or mother) .77 .77 Talk to father (or mother) about relationships .50 .50 Talk to father (or mother) about school difficulty .63 .58 Confused about father’s (or mother’s) role .76 .58 Father’s (or mother’s) mood, behavior, and thoughts .57 .53 Father (or mother) accepting your weakness .38 .46 Cares more about his (or her) or your life .52 .59 Frequency of angry at father (or mother) .54 .50 Hate your father (or mother) .66 .66 Your communication with father (or mother) .68 .77 Father (or mother) knows your needs .65 .67 Father (or mother) listens to you .60 .66 How much you care about your father (or mother) .69 .52 Miss your father (or mother) when away .58 .55 Respect your father (or mother) .64 .69 Value his (or her) values .75 .72 Admire your father (or mother) .76 .75 Desire to be like your father (or mother) .69 .78 Like his (or her) lifestyle .60 .75

Reliability analyses

To investigate scale reliability, I examined internal consistency by running Cronbach’s alpha. Measures of internal consistency were computed for each scale which is the 24 items for fathers and mothers. Coefficient as were .94 and .94 for the Father and Mother Scales, respectively, suggesting each scale measures its constructs consistently. Furthermore, the alpha coefficient value of fathering behaviors for each subscales were as follows: positive affection = .92, father

involvement = .83, communication = .88, and angry at father = .65. Whereas the alpha coefficient value of mothering behaviors for each subscales were as follows: positive affection = .95, role confusion = .83, communication = .90, and identification = .65. Reliability of approximately .70 or greater are statistically considered acceptable (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Since this is an exploratory study, we will still include ones that are close to .70.

Parent-child relationships.

The hypothesis was tested by computing two separate two-factor univariate analyses of variance. The purpose of this analysis was to test whether differences existed for the perceptions of paternal and maternal behaviors due to country of origin and/or gender. The dependent variables for each analysis were the total scores of ratings for the biological father and biological mother of the Parent-Child Relationships Survey. As proposed by Fine, Worley, and Schwebel (1985), only the total scale scores and not the individual scores should be used as the dependent variables to undergo analysis. The two factors used in analysis were subject’s country of origin and gender of participants. The main effect for subject’s country of origin was significant (F = 20.842, p<.000) for father-child relationships whereas the main effect for gender of the subject was not significant for father-child relationships. Also, the main effects for subject’s country of origin and gender of the subject were not significant for mother-child relationship.

Because of the nature of this instrument, four distinct dimensions of the biological father scale and the biological mother scale can be separately analyzed to better understand specific domains of parent-child relationships.

Dimensions of father-child and mother- child relationships by gender of the subject and country of origin.

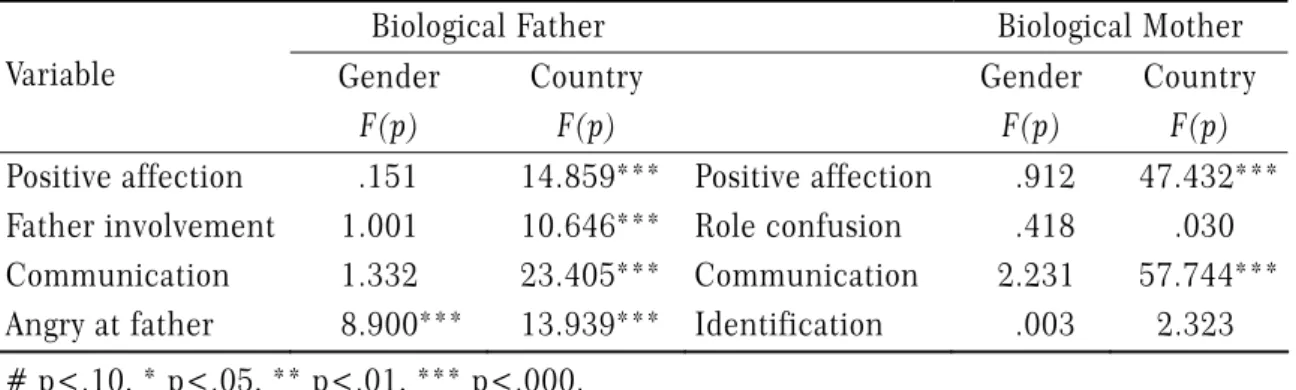

As shown in Table 2, two separate multivariate analyses of variances (MANOVA) were computed. Besides the use of the total scores of perceptions of paternal and maternal behaviors to test any potential differences, it was further suggested by Fine et al., (1985) to test the domains of parenting behaviors. The dependent variables in the first analysis were four domains of fathering behaviors which were adolescents’ perceptions of positive affection, father involvement, communication, and angry at father. Two covariates included in this analysis were country of origin (1= Taiwan and 2 = U.S.) and gender of the subject which male and female teens were treated as one single variables. The goal was to test whether there was significant difference perceived by teens in each sample in regard to fathering and mothering behaviors. Also, the dependent variables in the

second analysis for four domains of mothering of the Parent-Child Relationship Survey were adolescents’ perceptions of positive affection, role, identity, and communication.

In Table 2, positive affect shown by father (F =14.859, p<.000), the level of father involvement (F = 10.646, p<.001), communication with father (F = 23.405, p<.000) and child’s angry at father (F = 13.939, p<.000) were significant by subject’s country of origin. Teens in the U.S. sample perceived their fathers more positively in all four domains except the level of anger. Teens in Taiwan assessed their fathers with high level of anger. However, gender of the subject showed no significant across four domain of father-child relationships except for child’s angry at father (F = 8.900, p<.000). In terms of mother-child relationships, positive affect shown by mother (F = 47.432, p<.000) and communication with mother (F = 57.744, p<.000) were significant between U.S. adolescents and Taiwanese adolescents. Interestingly, all four domains of mother-child relationship were not significant when examining gender differences in their perception of mothering behaviors.

Table 2. MANOVA analysis of four dimensions on the biological father and biological mother of the Parent-Child Relationship Survey by Gender and by country of origin

Biological Father Biological Mother Variable Gender F(p) Country F(p) Gender F(p) Country F(p)

Positive affection .151 14.859*** Positive affection .912 47.432*** Father involvement 1.001 10.646*** Role confusion .418 .030 Communication 1.332 23.405*** Communication 2.231 57.744*** Angry at father 8.900*** 13.939*** Identification .003 2.323 # p<.10, * p<.05, ** p<.01, *** p<.000.

Gender 1= male, 2 = female Country 1 = U.S 2 = Taiwan

Adolescents’ perceptions of parental roles varied significantly due to adolescents’ country of origin in Table 2. In terms of how different male and female perceptions of their parenting behaviors were, it was not examined in Table 2 because male and female teens were lumped together as one single variable. Consequently, separating male and female adolescents to study their

perceptions closely could be necessary. Male and female adolescents were recoded to two different groups. Two MANOVAs were tested (not shown) to see whether boys and girls in both countries perceived their parenting behaviors differently. The results indicated that both male adolescents (F = 11.410, p<.001) and female adolescents (F = 9.456, p<.002) in these two countries perceived fathering behavior significantly different. Furthermore, the results showed that both male adolescents (F = 39.862, p<.000) and female adolescents (F = 16.670, p<.000) in these two countries perceived mothering behaviors significantly different. Therefore, the importance of investigating the different perception of parental roles in each gender from different country is evident.

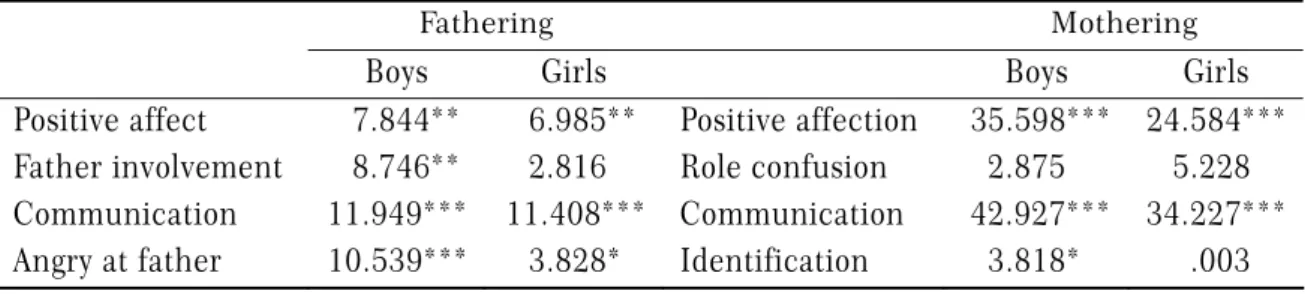

As shown in Table 3, two separate MANOVAs were computed. The dependent variables in the first analysis were four domains of fathering. In Table 2, each gender was lumped into a group which did not differentiate gender specific difference found in each region. The purpose of Table 3 attempted to find out gender specific difference found in each geographical area. One covariate included in the first analysis was male adolescents (1= Taiwan and 2 = U.S.) and one covariate included in the second analysis was female adolescents (1 = Taiwan and 2 = U.S.). The purpose was to test whether gender specific differences existed. Also, the dependent variables in the second analysis for four domains of mothering were included. In Table 3, each domain of fathering behavior reached significance level except for the level of father involvement perceived by female adolescents in either country whereas positive affection shown by mothers and communication with mothers were significant by both genders and only mother’s identification was significant between male adolescents in these two cultures. It is important to note that male adolescents in Taiwan perceived communication with mothers more positively than that with their fathers.

Table 3. MANOVA analysis of male and female perception on fathering and mothering

Fathering Mothering

Boys Girls Boys Girls

Positive affect 7.844** 6.985** Positive affection 35.598*** 24.584*** Father involvement 8.746** 2.816 Role confusion 2.875 5.228 Communication 11.949*** 11.408*** Communication 42.927*** 34.227*** Angry at father 10.539*** 3.828* Identification 3.818* .003 # p<.10, * p<.05, ** p<.01, *** p<.000.

Concluding Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine differences in adolescent males’ and females’ perceptions of their father’s and mother’s parenting roles in two cultural contexts. The findings with fathers in their involvement in these two samples were consistent with other studies that the perception of father involvement showed significantly different between male and female adolescent children (Milkie et al., 1997; Shek, 2000; Thompson & Walker, 1989). Expressive, affectionate traits are deemed important in the western societies, including America. As a result, parents are exposed to the ideology of positive affection, parental support, and warmth to their children. According to Shek (2000), Chinese culture generally discourages fathers from displaying expressive, affectionate traits when interacting with children because these traits are supposed to be expressed by mothers. This type of father-child relationship may weaken his positive influences on adolescents during this critical stage of development which needs parental support and guidance in the process of search of role identity. The likelihood may be high for adolescents in Taiwan to perceive their fathers as less affectionate in their interactions that may indirectly be associated with low desire to initiate further interaction with fathers. If this is true, a lower level of communication with their fathers perceived by adolescents in Taiwan may be a natural byproduct of minimal paternal affection. Taking low affection and communication altogether, the level of anger toward father was high, possibility due to lack of support and understanding from family members. Kuan (2004) argued that teens in Taiwan tend to avoid escalating conflicts which in turn may avoid further interactions with their fathers. Putnick et al (2008) proposed that fathers’ perceived acceptance may be more affected by their own distress and stress associated with parent-adolescent interactions whereas mothers’ perceived acceptance was more affected by stress linked to adolescents’ behaviors.

When looking at mothering domain, perceived affection shown by mothers to adolescents and communication with mothers showed significant difference in these two cultures. Mothers are typically perceived as the emotional support and ones who openly express care to their children in the U.S. whereas collectivistic culture such as Taiwan deemphasizes the importance of emotional expression and affection display to their family members, including children. Mothers who are affectionate and engage in meaningful communication may serve as a buffer mechanism to compensate low affection and communication displayed by fathers

in Taiwan.

Parenting is a complex familial issue (Lawson, 2004) that has been an interest to researchers, educators, and practitioners. Parenting in a distinct ethnic context may be greatly influenced by cultural norms rather than widely promoted conducts (LaRoosa, 1988), and the situation could be that affection shown by parents to children and communication with adolescents may not be considered as important parenting skills in Taiwan. After separating by gender in each cultural context, the aforementioned conditions still held true that male adolescents in each sample perceived fathering differently in all four domains whereas female adolescents in each sample only perceived fathering differently in the affection and communication domains. When examining mothering, positive affection shown by mothers and communication with mothers showed significantly different regardless of gender and country of origin.

A few limitations need to be discussed. First of all, the primary instrument designed by Fine et al., (1983) may not capture unique perceptions of parental behaviors by adolescents in another ethnic group. Cultures such as Taiwan place little emphasis on the importance of affection and communication may lead adolescents to assume their fathers are less involved and yet the nature of their involvement could be understood differently by fathers. Second, samples used in Fine and his colleagues’ studies to complete Parent-Child Relationship Survey mainly were college students from various family structures. However, the main focus of this study was on adolescents who may possess distinct ways of understanding parental behaviors and meanings of their interactions. Therefore, comparisons between this study and Fine’s studies may have distinct value. Finally, sample selected for this study in each group only represented a very small area in each society. Therefore, use of the findings requires special caution, particularly in applying to the large population.

Implications

Some suggestions for family life educators can be made based on this study. First of all, the results suggested that there is a possibility that father involvement was perceived differently between male and female adolescents in these two cultural contexts. Thus, educators should consider gender-sensitive activities for father-son interaction and father-daughter interaction. Milkie et al., (1997) suggested that shared activity between a father and his adolescents create nurturing interactions that are important for adolescents’ development. Mothers

are also encouraged to support her husband to be involved with the children. This can be done through family outings, movie night, or going out shopping as a family.

Second, perceptions of father involvement, positive affection of father, communication with father and anger toward father significantly varied in these two cultures. One interesting finding through this study was that both male and female adolescents in Taiwan perceived that their fathers initiate lower level of communication and a higher level of anger toward their fathers. Educators may want to explore the perceived substantial gap between these two important parenting behaviors to better understand adolescents’ perception when working with this particular group, paying particular attention to each gender so teens’ perception can be realized. Consequently, adolescents may be educated to examine their perception of communication needs and preference. The results of this study also indicated that male adolescents in Taiwan perceived more positively about communication with their mothers which may serve as a buffer mechanism when father involvement and communication was negatively perceived. In fact, educators can remind and prepare mothers to establish line of open communication with male adolescents who are in difficult times since mothers are generally perceived as the ones who are more approachable and nurturing than fathers. Third, many fathers still assume the provider role (Gaunt & Benjamin, 2007) which may create increased stress when job market becomes unstable. Bernard (1981) argued that the provider role directly defines masculinity for many men. To many men, the breadwinning role was a significant characteristic and indicator of how a good father was appraised. Therefore, many men believe that good fathers were good providers, whereas good providers made good fathers (Cohen, 1993; Palkovitz, 1997). This might be the case with fathers in Taiwan who could be influenced by this notion. So, it could also be important to address culturally acceptable parenting behaviors to fathers in Taiwan while introducing the benefits of displaying positive communication and affection to their adolescents. At the same time, mothers can be educated for their unique roles in the family to balance out or lower stress level from the economy. After this is done, fathers may be taught different ways of showing these two positive paternal behaviors. If the information learned is appropriately implemented, it is very likely that fathers have greater chance to maintain positive interactions with their adolescents.

References

Adler, S. (2003). Asian American families. In J. J. Ponzetti, Jr. (Ed.),

International encyclopedia of marriage and family (pp. 82-91). New York, NY:

Macmillan Reference USA.

Allen, S. M., & Hawkins, A. J. (1999). Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of

Marriage and Family, 61 (1), 199-212.

Almeida, D. M., & Galambos, N. L. (1991). Examining father involvement and the quality of father-adolescent relations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 1, 155-172.

Amato, P. R., & Rivera, F. (1999). Paternal involvement and children’s behavior problems. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 375-384.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child

Development, 55, 83-96.

Bernard, J. (1981). The good-provider role: Its rise and fall. American

Psychologist, 36(1), 1-12.

Berndt, T. J. (1996). Transitions in friendship and friend’s influence. In J. A. Graber, J.

Brook-Gunn, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence, (pp. 57-84),

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Bigner, J. J. (2006). Parent-child Relations: An Introduction to Parenting. 7th Edition Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/ Prentice Hall.

Bush, K. R. (2000). Parenting behaviors and the self-esteem and academic

achievement of European-American, Mainland Chinese, and Russian adolescents: Conformity and autonomy as intervening variables.

Unpublished dissertation, Ohio State University.

Bush, K. R., Peterson, G. W., Cobas, J. A., & Supple, A. J. (2002). Adolescents’ perceptions of parental behaviors as predictors of adolescent self-esteem in Mainland China. Sociological Inquiry, 72, 503-526.

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training.

Child Development, 65, 1111-1119.

Clark, J., & Barber, B. (1994). Adolescents in postdivorce and always-married families: Self-esteem and perceptions of fathers’ interest. Journal of Marriage

Cohen, T. F. (1993). What do fathers provide? Reconsidering the economic and nurturant dimensions of men as parents. In J. C. Hood (Eds.), Men, work,

and family. (pp. 1-22). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication, Inc.

Coles, R. L. (2006). Race and family: A structural approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Coughlin, C., & Vuchinich, S. (1998). Family experience in preadolescence and the development of male delinquency. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58, 491-501.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. (1994). Children and marital conflict: The impact

of family dispute and resolution. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Elder, Jr. G. H., Conger, R. D., Foster, E. M., & Ardelt, M. (1992). Families under economic stress. Journal of Family Issues, 13, 5-37.

Fauber, R., Forehand, R. Thomas, A. M. & Wierson, M. (1990). A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on poor adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child

Development, 61, 1112-1123.

Fine, M. A., Moreland, J. R., & Schwebel, A. I. (1983). Long-term effects of divorce on parent-child relationships. Developmental Psychology, 19, 703-713.

Fine, M. A., Worley, S., & Schwebel, A. I. (1985). The parent child relationship survey: An examination of its psychometric properties. Psychological Reports,

57, 155-161.

Gaunt, R., & Benjamin, R. (2007). Job insecurity, stress and gender: The moderating role of gender ideology. Community, Work, and Family, 10, 341-355.

Gray, M. M., & Steinberg, L. (1999). Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. Journal of Marriage and Family,

61, 574-587.

Harris, K. M., Furstenberg. Jr., F. F., & Marmer, J. K. (1998). Paternal involvement with adolescents in intact families: The influence of fathers over the life course. Demography, 35, 201-216.

Hamner, T. J., & Turner, P. H. (2001). Parenting in contemporary society. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Henry, C. S., Robinson, L. C., Neal, R. A., & Huey, E. L. (2006). Adolescent perceptions of overall family system functioning and parental behaviors.

Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 319-329.

In N. B. Webb (Eds.), Culturally diverse parent-child and family

relationships (pp.307-333). NY: Columbia University Press.

Hines, A. R., & Paulson, S. E. (2006). Parents’ and teachers’ perceptions of adolescent storm and stress: Relations with parenting and teaching styles.

Adolescence, 41(164), 597-614.

Hosley, C. A. & Montemayer, R. (1997). Fathers and adolescents. In M. E. Lamb (Eds.), The roe of the father in child development (pp. 162-178). NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Huang, W. (2005). An Asian perspective on relationships and marriage education.

Family Process, 44, 161-173.

Khaleque, A., & Rohner, R. P. (2002). Perceived parental acceptance-rejection and psychological adjustment: A meta-analysis of cross-cultural and intracultural studies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 54-64.

Kuan, P. Y. (2004) Peace, not war: Adolescents’’ management of intergenerational conflicts in Taiwan. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35(4), 591-614. LaRossa, R. (1988). Fatherhood and social change. Family Relations, 37,

451-457.

Lawson, K. L. (2004). Development and psychometric properties of the perceptions of parenting inventory. The Journal of Psychology, 138(5), 433-455.

Lee, E., & Mock, M. R. (2005). Asian families: An overview. In M. McGoldrick, J. Giordano, & N. Garcia-Preto (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (pp. 269-289). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Eye, A. V., Ostrum, C. W., Nitz, K., Talwar-Soni, R., & Tubman, J. G. (1996). Continuity and discontinuity across the transition of early adolescence: A developmental contextual perspective. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence:

Interpersonal domains and context (pp.3-22). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Maccoby, E. E. (1992). The role of parents in the socialization of children: A historical overview. Developmental Psychology, 28(6), 1006-1017.

Mbito, N. M. (2004). Adolescence social competence in Sub-Sahara Africa: The

relationship between adolescents’ perceptions of parental behaviors and adolescents’ self-esteem in Kenya. Unpublished dissertation.

Milkie, M. A., Simon, R. W., & Powell, B. (1997). Through the eyes of children: Youths’ perceptions and evaluation of maternal and paternal roles. Social

Mosley, J., & Thomson, E. (1995). Fathering behavior and child outcomes: The role of race and poverty. In W. Marsiglio (Ed.), Fatherhood: Contemporary

theory, research and social policy (pp. 148-165). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Noller, P. (1994). Relationship with parents in adolescence: Processes and outcome. In R. Montemayor, G. R. Adams, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Personal

relationships during adolescence (pp. 37-77). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications, Inc.

Palkovitz, R. (1997). Reconsidering “involvement”: Expanding conceptualizations of men’s caring in contemporary families. In A. J. Hawkins, & D. C. Dollahite (Eds.), Generative fathering: Beyond deficit perspective (pp. 200-216). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, Inc.

Papp, L. M., Cumming, E. M., & Goeke-Morey, M. C. (2009). For richer, for poorer: Money as a topic of marital conflict in the home. Family Relations, 58, 91-103.

Peterson, J., & Hawley, D. R. (1998). Effects of stressors on parenting attitudes and family functioning in a primary prevention program. Family Relations,

47, 221-227.

Plunkett, S. W., Behnke, A. O., Sands, T., & Choi, B. Y. (2009). Adolescents’ reports of parental engagement and academic achievement in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 257-268.

Putnick, D. L., Bornstein, M. H., Hendricks, C., Painter, K. M., Suwalsky, J . T., Collins, W. A. (2008). Parenting stress, perceived parenting behaviors, and adolescent self-concept in European American families. Journal of Family

Psychology, 22(5), 752- 762.

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (1999). Families with daughters, families with sons: Different challenges for family relationships and marital satisfaction. Journal of Youth

and Adolescence, 28(3), 325-342.

Shek, D. T. L. (2000). Differences between fathers and mothers in the treatment of, and relationship with, their teenage children: Perceptions of Chinese adolescents. Adolescence, 35(137), 135-146.

Simons, R. L., Johnson, C., & Conger, R. D. (1994). Harsh corporal punishment versus quality of parental involvement as an explanation of adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 591-605.

Smith, H. L., & Morgan, S. P. (1994). Children’s’ closeness to father as reported by mothers, sons and daughters. Journal of Families Issues, 15(1), 3-29.

Stevenson-Hinde, J. (1998). Parenting in different cultures: Time to focus.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Tein, J. Y., Roosa, M. W., Michaels, M. (1994). Agreement between parent and child reports on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 341-356.

Thompson, L., & Walker, A. (1989). Gender in families: Women and men in marriage, work, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51, 845-871.

Wagner, B. M., Cohen, P., & Brook, J. S. (1996). Parent/adolescent relationships: Moderators of the effects of stressful life events. Journal of Adolescent

Research, 11(3), 347-374.

Webb, N. B. (2001). Culturally diverse parent-child and family relationships. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wenk, D., Hardesty, C. L., Morgan, C. S., & Blair, S. L. (1994). The influence of parental involvement on the well-being of sons and daughters. Journal of

Marriage and Family, 56, 229- 234.

Wolman, B. B. (1998). Adolescence: Biological and psychological perspectives. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Adolescents’ Perceptions of Paternal and Maternal Behaviors:

An Exploratory Study

Shann Hwa Hwang1

Abstract

The current study investigated adolescents’ perception of paternal and maternal behaviors in two cultures. Participants included 291 adolescents in the Northern part of Taiwan and 231 adolescents in the middle Atlantic region of the U.S. The Parent-Child Relationships Survey was administered. Results from two-factor analysis of variance indicated that the total score of father-child relationship showed significant differences by adolescents’ country of origin whereas the total score of mother-child relationships was not significant. However, perceived fathering behaviors were significantly different among male adolescents across four domains of paternal roles in these two cultures compared to two domains by female adolescents. When examining four domains of mothering, the results showed that both positive affection shown by mothers and communication reached significant levels perceived by male and female adolescents. Limitations of this study and some implications for family life educators were provided.

Keywords: Adolescents’ perception, parenting behaviors, parent-child relationship survey