TAIWANESE FIRMS AND THEIR SUBSIDIARIES IN MAINLAND CHINA

Shyh-J er CHEN

Institute of Human Resource Management National Sun Yat-sen University

Kaohsiung, Taiwan Phone: 886-7-5252000 ext. 4927

Fax: 886-7-5254939 e-mail: schen@cm.nsysu.edu.tw

J ohn LAWLER

Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

504 East Armory Avenue, Champaign IL 61820, USA

Phone: (217)333-1482 Fax: (217)244-9290 e-mail: j-lawler@uiuc.edu

J ohngseok BAE

College of Business and Economics Hanyang University 17 Hangdang-dong, Sungdong-ku Seoul, Korea 133-791 Phone: 82-02-290-1069 Fax: 82-02-296-9587 e-mail:jsbae@email.hanyang.ac.kr

ABSTRACT

In recent decades, as business activities are becoming more internationalized and many foreign subsidiaries of multinational companies have been established, the comparison of employment relations (human resource management and industrial relations) among countries have gradually become important research focus. Researchers are interested in investigating the convergence/divergence issue of human resource management and industrial relations. The success of the foreign companies is directly related to understandings of employment relations in host countries.

Since the opening of China’s border for foreign direct investment and trade in 1978, Taiwanese businessmen initially had to invest in China via third countries, such as Japan and Hong Kong. Two major events— the Taiwanese government’s lifting, in 1987, of its ban on visits to China by Taiwan nationals, and the passage, in 1988, of a series of investment policies by China’s government encouraging

Taiwanese businesses to invest— create the heated wave of investment by Taiwanese in Mainland China. As Taiwan is such a large investor in China, the employment practices Taiwan firms introduce through subsidiaries are bound to have important consequences for China.

In this study, we examine the differences in employment practices between Taiwan and China and empirically compare the various employment systems used by Taiwanese firms in Taiwan and in China.

Intr oduction

In recent decades, as business activities are becoming more internationalized and many foreign subsidiaries of multinational companies have been established, the comparison of employment relations (human resource management and industrial relations) among countries has gradually become important research focus. Researchers are interested in investigating the convergence/divergence issue of human resource management and industrial relations. The success of the foreign companies is directly related to understandings of employment relations in host countries.

Taiwan and China have been separated from each other for more than fifty years. Since the opening of China’s borders for foreign direct investment and trade in 1978, Taiwanese businessmen began to enter into China for business investment via third areas, such as Japan and Hong Kong. The reasons why Taiwanese businessmen chose China as their major target to invest revolve around the arguments that China and Taiwan share the same culture and use the same language (Seo, 1993). Therefore, Taiwanese managers may expect Chinese workers to act in similar ways to their counterparts in Taiwan, but cultural and social changes that have occurred in China in this period often make employment practices that work well in Taiwan ineffective or counter productive in China. How Taiwanese firms manage their subsidiaries in China effectively becomes an important factor for the success of the firms.

In this study, we examine the differences in employment practices between Taiwan and China and empirically compare the various employment systems used by indigenous Taiwanese firms and their subsidiaries in China.

Review of Economic Refor m and Labor Mar ket Development

China is characterized by a centrally planned economic system through

government. Under this system, the Chinese government set the rules to regulate all economic activities of the enterprises. Before the economic reform in 1978, the most significant business entities were state-owned enterprises. The other types of

enterprises include urban collectives, town and village industries, and individual enterprises. State-owned enterprises produced almost 80 percent of total gross value of industrial output. In addition, most of the work force was employed by the state-owned enterprises, and enjoyed a “cradle to the grave” welfare system and so-called “iron-rice bowl” (Warner, 1996).

In addition, the state-owned enterprises have been seen as a major obstacle in the road of economic development due to low productivity of workers and decreasing efficiency of management. Zhu and Dowling (1995) pointed out that one third of state-owned enterprises were losing money in 1992. Management reform for the enterprises has been an important issue for China government. In recent years, reform in state-owned enterprises has resulted in large-scale unemployment of workers.

The “open-door policy” in 1978 marked a significant transformation for economic development in China. The ratio of total value produced by the

state-owned enterprises dropped rapidly since then because of the increase in foreign investment. There are several types of foreign investment, including joint ventures, cooperative ventures, and wholly foreign-owned. The total value of output produced by the firms from foreign investment has surpassed that of state-owned enterprises in past years.

Theor etical Backgr ound and Hypotheses

During the past two decades, many researchers have pointed out that employers have tended to implement many work and employment practices to increase

workplace efficiency in the US and other countries (Appelbaum and Batt, 1994; Kochan et al., 1986). Many employers installed ‘high performance work systems’ that purportedly develop more flexible and productive workforces when facing the challenge of global competition. These practices include: empowering employee with higher task autonomy; reducing job titles and layers of management; an increasing the use of outsourcing; extensive training and employee selectivity; information-sharing programs; the use of performance-based pay; and gain (profit)-sharing programs. Much research has showed that these practices yield positive results for employers (Delaney and Huselid, 1996; Huselid, 1995; Huselid, Jackson, and Schuler, 1997). These practices have resulted in reduced turnover rate, increased worker productivity, and higher firm profit.

Many researchers have tried to construct the categories of HRM strategies. Anthony, Perrewe, and Kacmar (1996) propose four types of HRM systems, including HR acquisition, HR maintenance, maximization of HR productivity, and turnover management. Dessler (1994) distinguishes HRM into five activities, such as selection, training, compensation, labor relations, and employee security. In addition to identifying different types of HRM activities, these researchers also try to tie HRM types to organizational effectiveness.

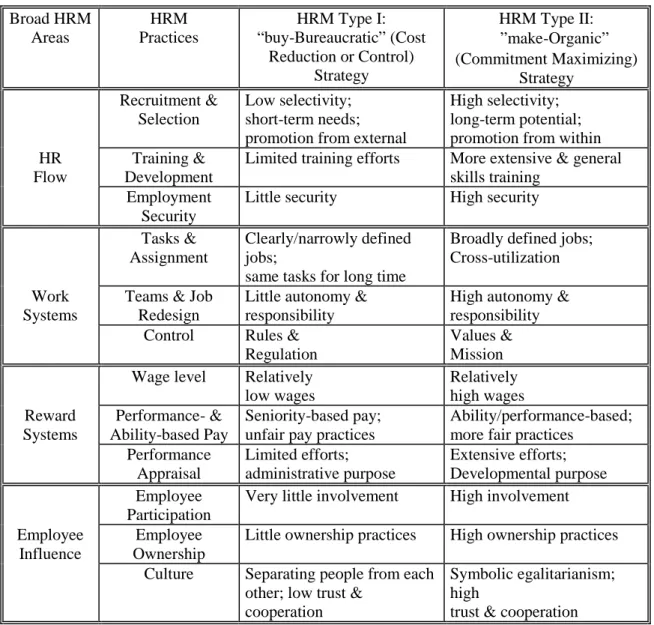

Following Bae, Chen, and Lawler (1998), we investigate four broad HRM activities. They are HR flow (recruitment, selection, training and development), work systems (control, teamwork, job specificity), reward systems (wages and performance assessment) and employee influence (employee participation and ownership). These HRM practices can be defined as a continuum of bundles. Bae (1997) has conceptualized them, ranging from a ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM systems to a ‘make-organic’ HRM system. The ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM system is similar to ‘cost-reduction’ or ‘control’ HRM systems, while the ‘make-organic’ HRM system is equivalent to ‘high-performance-work-system’ (Arthur, 1992; Pfeffer, 1994; Walton, 1985). As table 1 shows, the ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM system refers to these HRM practices as external hiring, limited training investment, narrowly defined job assignments, little autonomy in job, seniority-based pay, and little employee

participation. In contrast, the ‘make-organic’ HRM system includes internal promotion, extensive training investment, broadly defined jobs, high autonomy in

jobs, performance-based pay, and extensive employee participation.

The question if HRM/IR practices can be transferred among different cultures has been always an important issue in the past several decades. The ‘convergence hypothesis’ proposed that HRM/IR in various cultural settings could converge toward one unitary type. Kerr et al. (1960) predicted that ‘industrialism in the end may become one, but it certainly will have found its initial beginnings in the many’ (p.60). However, the ‘divergence hypothesis’ questioned the convergence of HRM/IR practices across national and cultural boundaries. They proposed that different cultures have their own organizational control mode, strategies, and so forth (Dole, 1973; Taira, 1992).

Hypothesis

Previous research has shown that employment practices of home countries have some influences on those of multinational companies (MNCs) in host countries. Lawler et al. (1992) found that western firms in Thailand had more systemic, rationalized and professionalized HRM practices when compared with Thai

companies. In addition, many foreign subsidiaries have mindsets of ‘ready-to-leave’ when the host countries are under hostile investment environment. China has been listed as an area of higher risky investment environment though it has attracted a large amount of investment in the past decade. Therefore, foreign subsidiaries in China would tend to be much careful.

Hypothesis 1: With the ‘ready-to-leave’ mindsets and risky investment environment, we expect Taiwanese firms in China are more likely to utilize ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM strategy than indigenous Taiwanese firms.

Since the 1950s, China government believed that China should pursue a low wage policy, that is, ‘to feed five people with the food of three people’. Under this policy, the Chinese government tried to keep the wage as low as possible. The average nominal wage increased only 1.04 percent and the average wage increased 0.3 percent between 1953 and 1978 annually (Jackson and Littler, 1991). Wages and benefits are planned by the central government and characterized by absolute egalitarianism (Zhu and Dowling, 1995). All workers are paid under one of three wage systems (8-grade, occupational, and cadre wage systems). Workers assigned to the same position are supposed to get the same pay regardless of their performance. The wage systems are called ‘iron wage system’. The ‘iron wage’ together with ‘iron rice bowl’ and ‘iron position’ has been criticized as the major reasons of low

workers’ productivity in China.

Guaranteed employment and wage, which have fostered a ‘civil service’ mentality and a lack of emphasis on the connection between pay and performance, have resulted in differences in management attitude and style toward workers. Therefore,

management style toward workers in China relative to workers in Taiwan.

Hypothesis 2b: Firms with human resource as an important priority tend to be more likely to have ‘make-organic’ HRM strategy than firms with human resource not as important priority.

Chinese trade unions cannot be understood in terms of western perspective because trade union law, which was promulgated in 1950 and revised in 1992, is replete with ideological terminology, such as ‘mass organization’, ‘working-class’, and ‘democratic centralism’ (Warner, 1995). One of main functions of trade unions is to provide political education for workers on behalf of the Communist Party. Trade unions in China play the role of ‘transmission-belts’ between the Communist Party and the working class (White, 1996). This is in sharp contrast to the functions of western trade unions.

Trade unions in Taiwan are regulated by the Labor Union Law, enacted in 1929 and last amended in 1975. This law set forth the structure, formation, and obligations of trade unions. ‘One plant, one union’ is the basic rule for the organization of union. Union membership is mandatory, that is, all workers are required to be union members if their workplace has been unionized. If workers refused to join unions, workers could be suspended from employment for a prescribed period of time by the trade union, based on the Enforcement Rules of the Labor Union Law. In spite of the suspension, many workers, in fact, do not join unions because the penal provision is

not implemented effectively. Trade unions in Taiwan are criticized as

‘employer-sponsored unions’ because they usually receive subsidies from employers (Chen and Taira, 1995). Therefore, trade unions are questioned about their

independence.

Because of a close relationship between trade unions and the Communist Party in China, foreign companies are much more likely to try to avoid unionization.

Furthermore, the different functions of trade unions in China are likely to make foreign companies unorganized. Therefore,

Hypothesis 3: We expect that union density of Taiwanese-owned firms in China tends to be lower than that of indigenous firms in Taiwan.

Porter (1985) distinguishes organizational strategies into two different typologies. There are ‘cost-leaders’ and ‘differentiators’. A firm that selects a cost leadership strategy seeks to become the low-cost producer in its industry, which create a sustainable competitive advantage. In contrast, a differentiator organizational strategy seeks to make its products unique along one or more dimensions valued by customers, such as technical prowess, product durability, outstanding services. If successful, these features would provide a sustainable competitive advantage.

In the past decade, Taiwan faces a shortage of labor and experienced out-migration of businesses. The shortage of labor has resulted in the import of

foreign labor. Simultaneously, many industries, such as textile and shoes, close their plants and move out to foreign countries because of gradual increase in labor cost in Taiwan. Most of these industries are labor-intensive. They move out because they would like to take advantage of low labor cost in foreign countries. Therefore,

Hypothesis 4: Taiwanese firms in China are more likely to adopt ‘cost-leader’ organizational strategies than indigenous firms in Taiwan.

Resear ch Methods Data

We developed a questionnaire to measure the various components of HRM system in firms. The questions focused on HRM practices only for non-managerial employees. The data were collected both in Taiwan and China during 1999. Since Taiwanese firms in China are widespread, the questionnaires were distributed through the organizations of Taiwanese business in China and are mainly from Southeast China.

The data for the Taiwanese firms in China were obtained from one hundred and nineteen firms. In terms of company size, around 77 percent of surveyed firms reported that they have less than 500 employees. More than 70 percent of the firms have been running their business for less than 10 years in China. The average firm age was 8.6 years. In addition, around 70 percent of the sample reported that their employees were not unionized in workplace. The sample represents 85.7 percent of

firms in manufacturing sector. The other is in service sector.

We also collected data from one hundred and eighty-two indigenous Taiwanese firms. The questionnaires were sent out to the top 1000 manufacturing firms and top 500 service firms in Taiwan. The return rate was 12 percent. 65 percent of firms have employees less than 500. 50 percent of the sample reported that they have existed for more than 20 years. 76 percent of firms do not have been unionized. In the sample, 84 percent was from manufacturing sector.

Variables

HRM system We are interested in comparing the similarities and differences between indigenous Taiwanese firms and Taiwanese-owned firms in China with regard to HRM practices. Bae, Chen, and Lawler (1998) have developed several scales and used to measure the differences in Taiwan and Korea. A total of twenty-seven items were used to measure HRM practices in the form of 6-point Likert’s scale ranging from “very inaccurate” to “very accurate.” These scales measure the firm’s human resource flow, work systems, reward system, and employee influence within the firms.

Firms that are high on the 10-item human resource flow scale utilize extensive selection and training procedures and have relatively high job security. Sample questions are: ‘Our firm provides employment security for non-managerial employees’, ‘It is very important for our firm to select the best person for a given

non-managerial job’ and ‘High priority is placed on training non-managerial employees in our firm.’ The 6-item work systems scale covers job design, control type, and team. Companies with higher scores of this scale tend to use jobs defined with enriched design and team-based work organization with high autonomy. Sample items include: ‘Non-managerial employees in our firm engage extensively in problem-solving and decision in matters which involve their jobs’ and ‘Coordination and control are based more on shared goals, values, and traditions rather than rules and regulations’.

The 7-item reward system scale represents the degree of relationship between workers’ performance and their pay level. Firms at the high end of the scale

emphasize pay performance. Sample items include: ‘Pay raises and promotions are closely tied to performance appraisal for non-managerial employees’ and ‘When performance is discussed with non-managerial employees, much emphasis is placed on finding avenues of personal development for the employees’. The 4-item

employee influence scale measures the extent to which workers are involved in decision-making related to their jobs and workers participate in organizational issues. Sample items include: ‘The opportunity of employee participation is very extensive through many different kinds of programs (e.g., information sharing, quality circle, work team, etc.)’ and ‘In our firm, we have minimum status differentials between management and employees to enhance egalitarianism (e.g., common

Organizational strategy We include a five-item scale that measures the degree to which a firm follows a differentiator rather than cost leader strategy. This is based on responses to Likert-style items on our survey form assessing such things as the firm’s commitment to product quality and service to customers rather than competing on the basis of price.

Sample items we ask in this variable include: ‘Providing customers with a variety of different kinds of products (or services)’; ‘Providing customers with specialized products (or services) to satisfy customers’ tastes’; and ‘Maintaining tight control of the quality of products (or services)’. Firms that have higher scores in this scale tend to utilize differentiator strategy instead of cost leader strategy.

HRM values Following Bae (1997), the management HRM values scale is assessed. Questions about management’s prioritization of human resource issues in the firm, management’s valuation of human resources in relation to financial resources and management’s beliefs about contribution of HRM policies and practices to firm performance are used to construct this scale.

Sample questions include: ‘Top management (or management group) of our firm considers the person in charge of human resources as a strategic partner in

formulating and implementing business strategy’; ‘Top management (or

management group) of our firm strongly believes that people and human resource policies and practices are sources of competitive advantages’. Firms scoring high on

this scale tend to assign high priority to HRM concerns.

Other Variables Other variables used here include firm size, unionization, and industry. Firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of full-time employees. Union (unionized firms coded as 1) and industry (manufacturing coded as 1) are dummy variables. In addition, firms located in China (China coded as 1) also represent a dummy variable, compared to firms located in Taiwan.

Results and Discussions

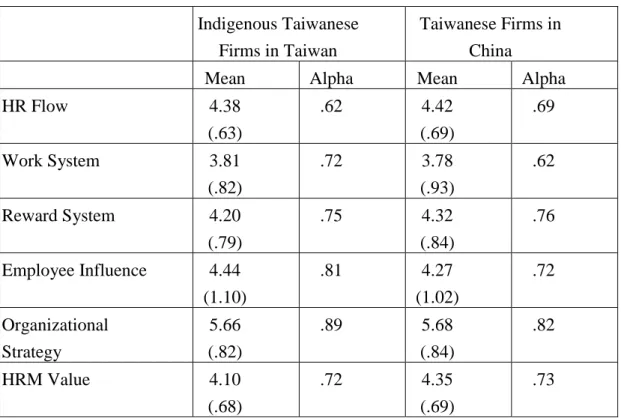

The reliability coefficients for HRM value scale, Organizational Strategy and the four HRM sub-functions are presented in Table 2. The alpha values are all acceptable except the values of HR Flow in both indigenous Taiwanese firms in Taiwan and Taiwanese firms in China (.62 and .69 respectively) and the value of the work system scale for the Taiwanese firms in China (.62). However, these values are reasonable close to the acceptable valuse of .70. The reliabilities all other coefficients scles exceed more than .70.

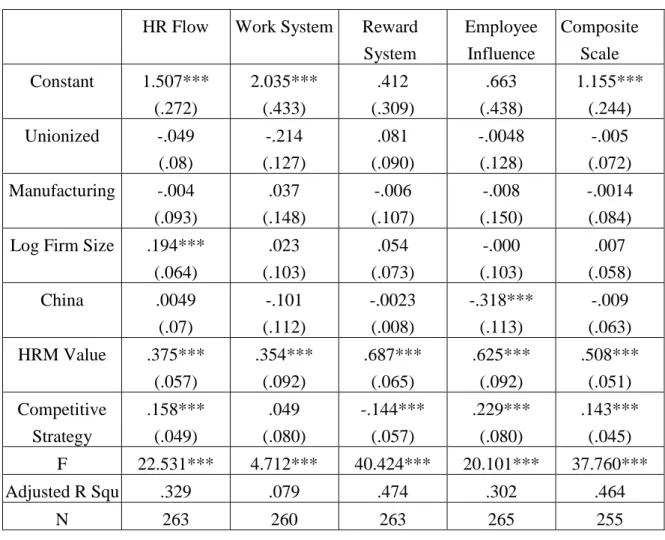

The results of multiple regression analysis for the four HRM areas and a composite scale (HRM system as a whole) are presented in Table 3. F-tests for the five regression models are significant at the .001 level. The adjusted R-squares are between .079 for Work System and .474 for Reward System.

Among the independent variable in Table 3, most unionized dummies negatively affected dependent variables, except in the case of reward system. In addition, most manufacturing dummies have a negative impact on HRM policies, except for Work System. Both unionized and manufacturing variables do not show significant impacts in the table. Firm size has positively effects on HR Flow, that is, larger firms are more likely to have extensive selection and training programs.

HRM values have positive and significant effects on all four HRM areas and composite scale. The results show that firms considering the person in charge of human resources as a strategic partner in implementing business and firms believing human resource policies as sources of competitive advantages tend to use

‘make-organic’ HRM strategy (Hypothesis 2b). Most competitive strategy variables have positive effects on HRM areas, except for Reward System. Firms that pursue market differentiation, operating efficiency, and economies of scale tend to use extensive selection in recruitment, to have training programs, to have higher employee involvement.

In Table 3, the country dummy variable (China) in the regression result has negative and significant impact on Employee Influence. Taiwanese firms in China tend to give employee less involvement and less symbolic egalitarianism than indigenous Taiwanese firms in Taiwan. Three of the other four regressions have negative, although not significant, effects on dependent variable exerted by the country dummy variable. The results partially show Taiwanese firms in China are

more likely to utilize ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM strategy than indigenous Taiwanese firms (Hypothesis 1).

Table 4 presents the regression result for HRM values. The result shows that Taiwanese firms in China have significant and positive impacts on HRM values. That is, Taiwanese firms in China tend to be more likely to consider human resource as a strategic partner and believe human resource policies as sources of competitive advantages. The result contradicts with the hypothesis 2a.

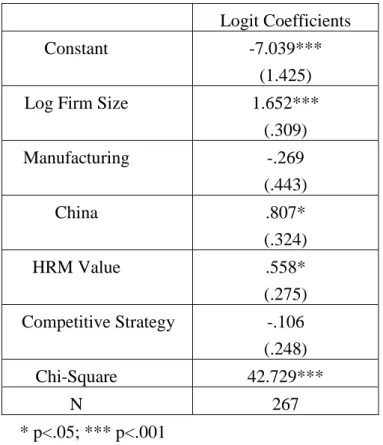

The related issue in this paper is to explore whether Taiwanese firms in China are more or less likely to be unionized compared to indigenous firms in Taiwan. To test the hypothesis 3, we use logistic regression to analyze union status. The union status here is a dummy variable. Independent variables include firm size, manufacturing sector, HRM value, competitive strategy, and China (also a dummy variable). Results are presented in Table 5. The overall equation for the unionization is highly significant. F value is significant at the .001 level. Firm size shows a positive and significant effect on union status, that is, larger firms are more likely to have union in workplace. In addition, Taiwanese firms in China tend to be more likely to have unions than indigenous firms in Taiwan. ‘China’ variable is positive and significant at the .05 level. This result also contradicts with hypothesis 3.

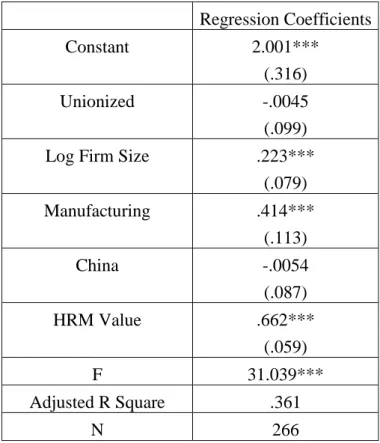

To understand the competitive strategy in both types of firms, we use competitive strategy as dependent variable to test the effect. The result is presented in Table 6.

‘China’ variable in this table has a negative, but not significant, effect on competitive strategy. The result shows that Taiwanese firms in China are more likely to adopt ‘cost-leader’ organizational strategy than indigenous firms in Taiwan (hypothesis 4). Furthermore, HRM value has a positive and significant impact on competitive strategy. This result shows that firms putting human resource as a partner tend to utilize ‘differentiator’ organizational strategy.

Conclusion

Let us review our findings with regards to the basic hypotheses. Several conclusions emerge from the analysis. First, Taiwanese firms in China are more likely to use ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM strategy. Although the empirical results are not all significant, ‘China’ variables are negative in four of five regressions. The

explanations for the results are partially consistent with the hypothesis that because the investment environment in China is risky, foreign countries sometimes have mindsets of ‘ready-to-leave’. Therefore, Taiwanese firms in China tend to utilize ‘buy-bureaucratic’ HRM strategy, including less employee influence, clearly defined jobs, little autonomy for employees and so forth.

Second, HRM value has been an important variable to influence HRM strategy. Firms that consider human resource as a major competitive advantage tend to utilize ‘make-organic’ HRM strategy. Therefore, firms that put human resource in a priority are more likely to have extensive selection, broad training, high autonomy, and

highly involvement. In addition, Taiwanese firms in China try to take advantage of low labor cost and many industries in China are labor-intensive. Therefore, These firms in China are more likely to use ‘cost-leader’ organizational strategy, compared to their counterparts in Taiwan.

Third, we hypothesized that union density of Taiwanese firms in China would be lower than that of indigenous firms in Taiwan because trade unions have close relations with Communist party in China and employers are reluctant to be unionized in their workplace (hypothesis 3). The hypothesis seems to be rejected from the empirical finding. The result may be due to the characteristics that trade union exerts an important influence on the workplace. The Communist Party usually persuades and encourages foreign companies to form a trade union.

Refer ences

Anthony, W. P., Perrewe, P. L., and Kacmar, K. M. (1996) Strategic Human Resource Management. The Dryden Press Harcourt Brace College Publishers. Appelbaum, E. and Batt, R. (1994) The New American Workplace: transforming Work Systems in the United States. Ithaca and London: ILR.

Arthur, J. (1992) “The Link between Business Strategy and Industrial Relations Systems in American Steel Minimills,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 45(3): 488-506.

Bae, J. (1997) Competitive Advantage, HRM Strategy and Firm Performance: The Experiences of Indigenous Firms and MNC Subsidiaries in Korea and Taiwan. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Bae, J., Chen, S. and Lawler, J. (1998) “Variations in Human Resource Management in Asian Countries: MNC Home-country and Host-country Effects.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9(4): 653-670.

Beer, M., Spector, B., Lawrence, R.R., Mills, D.Q., and Walton, R.D. (1985) Human Resource Management: A General Manager’s Perspective. New York: The Free Press.

Chen, S. and Taira, K. (1995) “Industrial Democracy, Economic Growth, and Income Distribution in Taiwan.” American Asian Review, 13(4): 49-77

Delaney, J.T. and Huselid, M.A. (1996) “The Impact of Human Resource

Management Practices on Perceptions of Organizational Performance,” Academy of Management Journal, 39(4): 949-969.

Dessler, G. (1994) Human Resource Management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

Dole, R.C. (1973) British Factory/Japan Factory. Berkeley and Los Angeles: The University of California Press.

Huselid, M.A. (1995) “The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance,” Academy of Management Journal, 38(3): 635-672.

Huselid, M.A., Jackson, S.E. and Schuler, R.S. (1997) “Technical and Strategic Human Resource Management Effectiveness as Determinants of Firm

Jackson, S. and Littler, C.R.(1991) “Wage Trends and Policies in China: Dynamics and Contradictions,” Industrial Relations Journal, 22(1): 5-19.

Kerr, C., Dunlop, J.T., Harbison, F. and Myers, C.A. (1964) Industrialism and Industrial Man: The Problems of Labor and Management in Economic Growth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kochan, T.A., Katz, H.C. and McKersie, R.B. (1986) The Transformation of American Industrial Relations. New York: Basic Books.

Lawler, J.J., Atmiyanada, V. and Zaidi, M. (1992) “Human Resource Management Practices in Multinational and Local Firms in Thailand,” Journal of Southeast Asia Business, 8(1): 16-40.

Pfeffer, J. (1994) Competitive Advantage through People. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage. New York: Free Press.

Seo, K.K. (1993) “Economic Reform and Foreign Direct Investment in China before and after the Tiananmen Square Tragedy,” in Lane Kelley and Oded Shenkar (eds.) International Business in China. New York: Routledge, pp. 109-136.

Taira, K. (1992) “The End of Convergence Theories: Japanization of U.S. Human Resource Management and Industrial Relations.” In Negandhi, A.R. and Serapio, M.G. (eds.) Research in International Business and International Relations, Vol 5. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp. 241-58.

Walton, R. E. (1985) “From Control to Commitment in the Workplace.” Harvard Business Review, 62(2): 77-84.

Warner, M. (1995) The Management of Human Resources in Chinese Industry. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Warner, M. (1996) “Economic reforms, industrial relations and human resources in the People’s Republic of China: An overview,” Industrial Relations Journal, 27(3): 195-210.

White, G. (1996) “Chinese Trade Unions in the Transition from Socialism: Towards Corporatism or Civil Society?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 34(3): 433-457.

Zhu, C.J. and Dowling, P.K. (1995) “The Impact of the Economic System upon Human Resource Management Practices in China,” Human Resource Planning, 17(4):1-21.

Table 1: A Typology of HRM Systems and HRM Pr actices Broad HRM Areas HRM Practices HRM Type I: “buy-Bureaucratic” (Cost Reduction or Control) Strategy HRM Type II: ”make-Organic” (Commitment Maximizing) Strategy Recruitment & Selection Low selectivity; short-term needs; promotion from external

High selectivity; long-term potential; promotion from within HR

Flow

Training & Development

Limited training efforts More extensive & general skills training

Employment Security

Little security High security Tasks &

Assignment

Clearly/narrowly defined jobs;

same tasks for long time

Broadly defined jobs; Cross-utilization Work

Systems

Teams & Job Redesign

Little autonomy & responsibility

High autonomy & responsibility Control Rules &

Regulation

Values & Mission Wage level Relatively

low wages Relatively high wages Reward Systems Performance- & Ability-based Pay Seniority-based pay; unfair pay practices

Ability/performance-based; more fair practices

Performance Appraisal Limited efforts; administrative purpose Extensive efforts; Developmental purpose Employee Participation

Very little involvement High involvement Employee

Influence

Employee Ownership

Little ownership practices High ownership practices Culture Separating people from each

other; low trust & cooperation

Symbolic egalitarianism; high

trust & cooperation Source: Adapted from Bae, Chen, and Lawler (1998), p. 655.

Table 2: Means and reliabilities for HRM scales (standard deviations in parenthesis)

Indigenous Taiwanese Firms in Taiwan

Taiwanese Firms in China

Mean Alpha Mean Alpha

HR Flow 4.38 (.63) .62 4.42 (.69) .69 Work System 3.81 (.82) .72 3.78 (.93) .62 Reward System 4.20 (.79) .75 4.32 (.84) .76 Employee Influence 4.44 (1.10) .81 4.27 (1.02) .72 Organizational Strategy 5.66 (.82) .89 5.68 (.84) .82 HRM Value 4.10 (.68) .72 4.35 (.69) .73

Table 3: Results of Regression for Four HRM Areas: Pooled Data (standard errors in parentheses)

HR Flow Work System Reward System Employee Influence Composite Scale Constant 1.507*** (.272) 2.035*** (.433) .412 (.309) .663 (.438) 1.155*** (.244) Unionized -.049 (.08) -.214 (.127) .081 (.090) -.0048 (.128) -.005 (.072) Manufacturing -.004 (.093) .037 (.148) -.006 (.107) -.008 (.150) -.0014 (.084) Log Firm Size .194***

(.064) .023 (.103) .054 (.073) -.000 (.103) .007 (.058) China .0049 (.07) -.101 (.112) -.0023 (.008) -.318*** (.113) -.009 (.063) HRM Value .375*** (.057) .354*** (.092) .687*** (.065) .625*** (.092) .508*** (.051) Competitive Strategy .158*** (.049) .049 (.080) -.144*** (.057) .229*** (.080) .143*** (.045) F 22.531*** 4.712*** 40.424*** 20.101*** 37.760*** Adjusted R Squ .329 .079 .474 .302 .464 N 263 260 263 265 255 *** p<.001

Table 4: Regression for HRM values: Pooled Data (standard errors in parentheses)

Regression Coefficients

Constant 3.984***

(.217)

Unionized .208

(.102)

Log Firm Size .0054

(.081) Manufacturing -.0091 (.117) China .274*** (.089) F 4.384** Adjusted R Square .048 N 271 ** P<.01; *** p<.001

Table 5: Logit Analysis of Unionization Status: Pooled Data (standard errors in parentheses)

Logit Coefficients

Constant -7.039***

(1.425)

Log Firm Size 1.652***

(.309) Manufacturing -.269 (.443) China .807* (.324) HRM Value .558* (.275) Competitive Strategy -.106 (.248) Chi-Square 42.729*** N 267 * p<.05; *** p<.001

Table 6: Regression for Competitive Strategy: Pooled Data (standard errors in parentheses)

Regression Coefficients

Constant 2.001***

(.316)

Unionized -.0045

(.099)

Log Firm Size .223***

(.079) Manufacturing .414*** (.113) China -.0054 (.087) HRM Value .662*** (.059) F 31.039*** Adjusted R Square .361 N 266