國立交通大學

碩士論文

幽默在臺灣大學英語課堂

Humor in the Taiwan EEL University Classroom

所別:英語教學研究所

學號: 9459511

姓名:鐘雷恩 Ryan M Jones

指導教授: 孫于智博士

i 摘要 這篇論文調查幽默如何在台灣大學英文課程中被使用。總共有十二堂語文技巧課程,六堂 是由外籍英文老師授課,而另外六門是由臺灣籍教師授課。兩段的記錄影片是在台灣北部 兩所公立大學所錄製。此論文是在探討學生和教師使用的幽默量、最常使用的幽默類型、 以及幽默如何被運用在臺灣的大學英文課程中。相反於刻板印象,根據紀錄影片幽默被學 生和教師廣泛普遍的使用於課堂上。此外,可以從課堂中找出十一種幽默類型。學生和教 師都會使用到的幽默在有趣聞、流行文化或學生生活的話題、機智、文字遊戲、詼諧的評 論、以及各種素材等…分析顯示出幽默在臺灣大學英文課程裡有兩個基本功能:作為課堂 管理的目的和教學工具(教導語言學,應用,文化等方面的語言)。此論文提供實例說明幽 默在臺灣大學的英文課程裡的種類和形式。建議運用定性研究方法,更深入地探討幽默的 數量、種類和功能,將會更明確的了解幽默在各式各樣的臺灣英語教學情境裡的數量、種 類和功能。此外,根據不同的國籍教師授課的英文課程情境下,也許更多的研究能檢示出 台灣和其他國家文化使用幽默的差別。

ii ABSTRACT

This thesis investigates the use of humor in the Taiwan University English as Foreign Language (EFL) classroom. A total of twelve EFL skill classes—six classes taught by Native English speaking instructors (NEI) and six classes taught by a Taiwanese Instructors (TI) — were video recorded two times at two public universities in Northern Taiwan. The paper examined the

amount of humor used by the students and instructors, the most common types of humor, and how humor was used in the Taiwan EFL university classroom. Contrary to the stereotype, humor was pervasive and used extensively by both instructors and students throughout all the classes recorded. In addition, eleven types of humor used by instructors and students were identified. Examples of humor used by both instructors and students include personal anecdotes, references to popular culture and student life, comedic comparisons/contrasts, wit, word play/code switching, tongue-and-cheek comments, and third party humor, etc. An analysis of the functions of humor in the Taiwan EFL University classroom revealed that humor has two basic functions: for classroom management purposes and as a pedagogical tool to teach the linguistic, pragmatic, and cultural aspects of the language. This paper provides illustrative examples of the types of humor and the way humor is used in the Taiwan University EFL classroom. It is suggested that more research examining the amount, types, and functions of humor in other Taiwan EFL classroom contexts, as well as other content courses, using ethnographic research methods will allow for a broader picture of the amount, types and functions of humor across a wide variety of EFL classroom contexts across Taiwan. In addition, in light of the different nationalities present in the Taiwan EFL classroom context, perhaps more research could be conducted examining the difference in humor used by Taiwanese students and instructors and other cultures.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis could not have been completed without the time, help, knowledge, advice, energy and enthusiasm of many people.

First of all, I am deeply indebted to the instructors and the students who allowed me to record their classes and, in addition, give up their free time in order to go over all the material after the recordings with me. Without their kindness, this paper could have never been written. I am also forever grateful to Amanda Shih, Amber Jeng, and Chynny Chen for spending their evenings and weekends helping me translate and transcribe all the data; their hard work was unprecedented. I am also grateful to Irene Shu and Iris Liu for helping me translate some parts of the thesis. I would also like to thank Cathy Hung who spent many afternoons to help me transfer the videos from cassette to disc and also for all the encouragement and the late afternoon talks.

I would also like to take the time to thank my colleagues Thomas Casterline, Andrew Chard, Tessa Edwards, JS Goyette, and Nancy Chen for help with proofreading.

To all my professors, I would like to give many thanks for instilling in me the theories and research methods that encompass the field of TESOL. I firmly believe that I have become a better teacher and researcher because of the TESOL department at NCTU. In particular, I give my greatest debt to my advisor Dr. Yu-Chih Sun for her support and patience over the last couple of years. I would like to thank her giving me guidance—not only in regards to being a student but also in life—and the freedom to wonder where ever my research takes me. It has truly been a rewarding educational and life experience to work with her. I would also like to give thanks to my committee members Dr. Johanna Katchen and Dr. Fang-Ying Yang for their hard work and

detailed comments that added to the final vision of this thesis. I would like to thank Dr. Katchen for all support and encouragement over the years and all the hilarious meetings in her office. This

iv

thesis has also benefited from the comments of Dr. Shu-Chen Huang. I would like to give thanks to her for all her advice and all the late evening talks.

I would also like to take the time to say thank you to all my classmates. I had a wonderful time being in class and hanging out with all of you. I am so sorry for making you speak English all the time.

I would also like to give thanks to my university advisor and friend Dr. Marshall Johnson. If you were not for him, I would have never known about Taiwan.

This paper is dedicated to my mom, Elaine Jones, my Aunt Beverly and my dear friend James Hanson (who both passed away during the process of this thesis). Throughout my life they have always encouraged me to be the best I can be and not take life too seriously.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHINESE ABSTRACT………....i ENGLISH ABSTRACT………...ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………..iii TABLE OF CONTENTS……….v LIST OF TABLES………vviCHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION……….1

1.1 Overview………...1

1.2 Motivation of the Study………...2

1.3 The PresentStudy………..4

1.4 The Organization of the Study………. ………5

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW……….6

2.1 Overview of Humor Research………...6

2.1.1 Theories of Humor………...7

2.1.2 Humor in Taiwan……….8

2.1.3 Defining Humor………..8

2.1.4 Types of Humor in Literature………10

2.1.5 Social Functions of Humor………...13

2.2 Classroom Humor Research………15

2.2.1 Methods of Classroom Humor Research………...16

2.2.2 Taxonomies of Classroom Humor………....19

2.2.3 Frequency of Humor in the Classroom………...20

2.2.4 Functions of Classroom humor……….20

2.3 Humor as a Pedagogocal Tool in Language Classrooms………...22 CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY

vi

3.1 Overview ………...28

3.2 Participants ………28

3.3 Procedures for Collecting Data………..29

3.4 Participant Knowledge of Study………31

3.5 Data Analyses……….31

3.5.1 General Laughter………....31

3.5.2 The Intent of the Speaker………...32

3.5.3 Point of View of the Researcher……….32

CHAPTER FOUR RESULTS 4.1 Overview………35 4.2 Reseach Question 1………35 4.3 Result………...35 4.4 Research Question 2………..37 4.5 Results. ………..37 4.6 Research Question 3………..51 4.7 Results………51

4.7.1 Humor Used for Classroom Management………..51

4.7.2 Humor Used as a Pedagogical Tool………57

CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION……….64

5.1 Discussion………..64

5.2 Recommendations for Future Research……….69

5.3 Conclusion……….69

REFERENCES………..71

APPENDIX 1 Key to transcriptions………76

vii

TABLES

Table 1—List of Classes Recorded………30

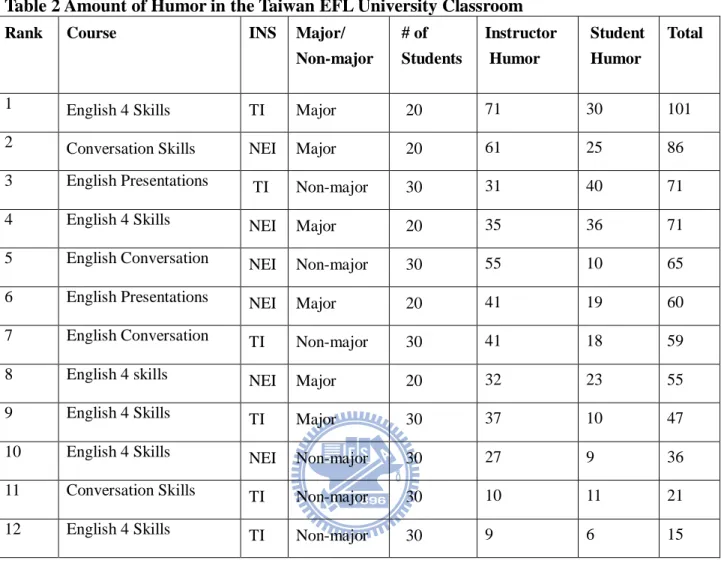

Table 2---List of the Amount of Humor in Each Class………...36

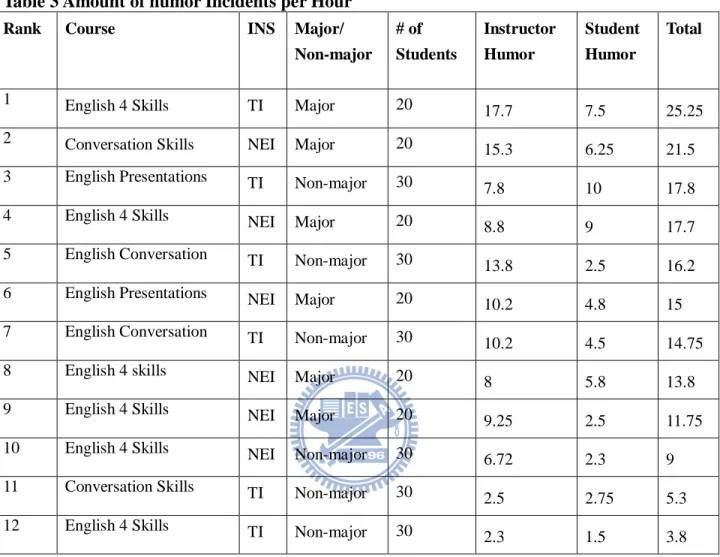

Table 3—List of the Amount of Humor Per-hour in Each Class………37

i

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Overview

Over the last three decades, humor research has become prominent in a wide variety of

disciplines. Scholars from multiple fields have been investigating humor from a wide variety of perspectives. In fact, humor research has become so pervasive that there is even a regular journal entitled “Humor: International Journal of Humor Studies” that is dedicated to the investigation of humor theories and humor research methodologies. Specifically, research on classroom humor has become increasingly prolific. For example, numerous studies have documented the positive effects of humor in classrooms, (i.e. Adams 1974, Askildson, 2005, Berwald 1992, Bryant and Zillman 1989, Gorham 1998, Gorham and Christophel 1991, Loomax and Moosavi 1998, Friedman, Friedman and Amoo 2002, Wandersee, 1982). However, until recently, humor research within the context of the Foreign Language classroom has received relatively little attention. Currently, there are many misunderstandings and misconceptions postulating the use of jokes and humor in foreign language classrooms, but there is a lack of empirical evidence that documents how humor is actually used within foreign language contexts not only by teachers, but students as well. This thesis intends explore humor within the EFL classroom in Taiwan from a sociolinguistic perspective in hopes of fulfilling this gap.

2

1.2 Motivation for Present Study

My interest in language teaching, pragmatics, sociolinguistics, and, more precisely humor arise from my own experience as a teacher of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in Taiwan and in my interactions with many non-native English speakers (NNS) in Taiwan and China. First, as a language educator in Taiwan and China, I have shared a similar experience as to what

Trachtenberg (1979) experienced in her English as a Second language classroom: the huge difference in students‟ personalities when speaking their native language as compared to their second language. Of course, Trachtenberg (1979) admits that the students‟ speech behavior in their native language was far more natural and spontaneous than their speech behavior in English. But, according to her, the biggest difference in the students‟ personalities was humor. This, too, is something that I have observed in classrooms in Taiwan and China over the years. And, for me, like Trachtenberg (1979), the biggest difference is humor. It is almost like students have two different personalities (they are two different people). This has piqued my interest in pedagogical humor in language learning (L2) classrooms as, I feel, that to ignore the humor element in the target language (TL), is to deny a part of one‟s social identity in the language learning process. As Trachtenberg (1997) puts it: “the projection of a sense of humor is in fact a key element that must be encouraged if the student of English as a second language is indeed to be himself in an English speaking milieu,” (p. 90).

In addition to the experience in the classroom, in my interactions with NNS in Taiwan and abroad, I have experienced and observed what Harder (1980) called “reduced personality.” This, according to Harder (1980), is when NNS are ascribed a lower than normal status in conversations with NS because of their language ability. He claims that this comes as a result of NNS using non-target like discourse patterns. According to Harder (1980), this can include the

3

learners‟ inability to use and understand jokes and humor. In his words “being a foreigner entails not understanding jokes and therefore having a choice between sitting quiet or being a simpleton who asks for an explanation,” (p. 262). This is something that I have witnessed many times in my own NS-NNS interactions here in Taiwan and abroad: the NNS‟ inability to use and understand L2 humor causing them to be left out of lively, interesting, and knowledgeable conversations resulting in the projection of a boring, uninteresting, and, perhaps, inept

personality. In addition, I have also noticed that I have been a “reducer” of personalities in my own right in interactions with NNS attempts at humor. For example, there have been times in which I did not appreciate the humor of my NNS friends and acquaintances, the humor of classmates, and even the humor from my instructors. Finally, there are also times when I “toned down” my own humor in interactions with NNS for fear they would not understand or might be offended by it.

Furthermore, the topic of my thesis also seemed to garner interest from many of my Taiwanese students and friends. After hearing about my topic, many of them told me stories about not be able to understand American humor. For instance, most of them told me about not being able to enjoy popular Hollywood movies because they did not understand the humorous parts, or feeling embarrassed on vacations in the United States because they were the only ones not laughing hysterically when the tour guide told a joke.

All these stories have inspired me to investigate the role of humor in the intercultural context of Taiwan, with particular emphasis on the university EFL classroom. An understanding of this, I believe, is necessary for EFL practitioners and those interested in intercultural

communication. Findings from this study may enable practitioners to further explore humor in foreign language classrooms and perhaps add to the increasing amount of research that is

4

investigating how humor is in used L2 classrooms. It is not my intention to argue for the inclusion and/or exclusion of humor in the EFL classrooms or to impart “facts” that should be incorporated into pedagogy. My intention is merely to develop a dynamic description of the types of humor and how they are employed in EFL classrooms. This, I feel, will allow for specific insights which may help illuminate pedagogy and interaction within an intercultural context.

1.3 The Present Study

The present study heeds Schmitz‟ (2002) call for a closer examination of the role that humor has in foreign language classrooms. The purpose of this study is to examine the use of humor in the EFL classroom, in particular, the EFL university classrooms in Taiwan from a sociolinguistic point of view (Hymes, 1972). I intend to classify and determine the different kinds of humor that are used by non-native English speaking instructors (NNS) and native English speaking

instructors (NS) and students. I will also examine how often humor is used. The results of the study will lead to preliminary decisions on the role that humor has in the foreign language classroom in Taiwan. My research questions are as follows:

1) How much humor is used in the Taiwanese University classroom? 2) What types of humor are used by students and instructors?

3) What are the functions of the humor and is there any evidence it is used as a pedagogical tool?

5

Taiwan. Six classes taught by Taiwanese instructors (TI) and six class taught by native English Speaking instructors (NEI) participated in the study. The amount of humor was documented, twelve types of humor were put forth, and a functional taxonomy was presented. Also, the study examined if humor was used in any way as a pedagogical tool.

1.4 Organization of the Study

This thesis in made up of five chapters. Chapter One explains the motivation for the study Chapter Two will review the pertinent literature regarding humor research. This will include theories of humor, humor in Taiwan, contemporary definitions of humor, the types of humor, and the social functions of humor. I will then discuss past relevant findings that specifically refer to humor in classroom contexts. The specific methodology of this paper will be discussed in Chapter Three. The reason for choosing the methodology, the design of the project, the

participants, the procedures of collecting information, and the data analysis will be addressed. In Chapter four, I will present the empirical findings if of the study. Chapter Five will conclude the study with a summary of major findings, pedagogical implications, limitation of study and suggestions for future research.

6

CHAPTER TWO

LITERTURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

Although humor as been a topic that has fascinated humans for centuries, it was only in the last quarter century that it blossomed into a serious interdisciplinary and multifaceted field of study. Scholars from anthropology, sociology, education, linguistics, communications, management, and psychology have investigated the various aspects of humor and joking. Needless to say, despite the breadth of scope, the following discussion, by necessity, is a very limited review when compared to the huge amount of literature that exists on humor. It merely provides background information which, I feel, is relevant for the formulation of this thesis. The main caveat of this thesis is that the literature is for the most part derived from Anglo-Saxon contexts, as humor research with specific reference to Taiwan is lacking. Thus, I limited my discussion to literature that, I feel, would be directly relevant to the topic of my thesis.

This chapter is divided into two parts. The first section intends to be a general overview of humor research. This will include research that explores various definitions and types of humor. I will also review the social functions of humor. The next section will discuss the research that specifically refers to classroom humor: reviews on classroom humor taxonomies, and studies that examine the functions of classroom humor and finally, I will conclude this section by discussing research that documents how humor can be used as a specific illustrative tool to teach specific aspects of the target language. I will begin by discussing the theories of humor.

7 2.1.2 Theories of Humor

There are various theories of humor that have been put forth by scholars. For the most part these theories have been broadly divided into three theoretical perspectives: superiority/disparagement theories, arousal/relief theories, and incongruity theories.

Superiority or disparagement theories are based on the notion that we enhance our feelings of superiority by laughing at the imperfections and errors of others (Norrick, 1993). Zillman and Cantor (1976) point out that there is an element of hostility in that we tend to laugh more at a disliked target than a liked target.

Arousal/ relief theories propose that laughter is a result of a sudden psychological and physiological shift in which nervous tension and repressed energy are released (Norrick, 1993).

Incongruity theories propose that humor is experienced when we perceive and react to similar/dissimilar stimuli. For example, the oxymoron “jumbo shrimp” could possibly stimulate laughter or a smile in that it combines two contradictory terms (Graham, Papa, & Brooks, 1992). Suls (1972) presented a two-stage incongruity-resolution model that describes the cognitive process involved in the humor comprehension of the incongruity. The first stage involves the recognition of the incongruity. That is, the discrepancy between what is expected to happen and what has actually occurred in the event. The second stage represents the problem-solving task the learner goes through in order to solve the incongruity. It is at this stage that incongruity becomes meaningful.

Obviously, these theories are not that comprehensive and the ways in which they interrelate are somewhat complex, but they do provide a basis for the majority of research on humor. Needless to say, it is not my intention in this thesis to delve into why something is funny or not. Instead I will be concentrating on humor, and how it occurs within the context of the EFL university classroom in Taiwan.

8 2.1.3 Humor in Taiwan

In China and Taiwan, humor has been given little respect. According to Yue (2010), this is mainly because traditional Confucian ideals emphasize proper and civil manners in all social interactions. Yue (2010) mentions that once in 500BC Confucius executed humorists for having “improper performances” in front of high ranking officials. Liao (2003) mentions that in Taiwan, humor is rarely academically studied. However, over the last ten years more and more humor research has been sprouting up.

The term for humor in Chinese was translated by Mr. Lin Yutang (林語堂) in 1923 from huaji (滑稽) to youmo(幽默) as he was trying to promote the use of humor in Chinese society (Kao 1974). Youmo (幽默) basically describes humor that is thought of in the west as clever, witty, ironic, and just generally funny (Kao 1974). He contended that youmo (幽默) should contain a thoughtful smile and not explicit laughter—or a high class type of humor. To the contrary, Huaji— considered the earliest form of humor and literally translated as “滑,” meaning “slippery” or “smoothen”; and the character “稽,” meaning “trick,” (Yue 2010, p. 404)—was deemed low class, despicable behavior that causes laughter. For example, laughing at someone slipping on a banana peel tends to be more huaji (滑稽), while more respectable, verbal

humorous interaction tends to be youmo (幽默). Liao (2003) puts forth that many Chinese deem youmo as a Western influence. However, Yue (2010) contends that humor has had a long

tradition in China similar to that in the Western world.

2.1.4 Defining Humor

The difficulty of defining humor is well documented in the field. Nevertheless, many

9

smile,” (Ross, p.1). This definition overlaps with both Long and Graesser (1988). Apte (1985) approaches humor from an anthropologic perspective and offers three definitions: “1) sources that act as potential stimuli 2) the cognitive and intellectual activity that are responsible for perception and evaluation of these sources leading to humor experience and 3) behavioral response that are expressed as smiling and laughter,” (p. 13-14). In agreement to this thesis, the first definition presented by Apte (1985) will be adequate in that I will be focusing on student and teacher humor within the EFL classrooms.

More recently, most definitions of humor center around two kinds: the SLA definition and the sociolinguistic definition. For L2 researchers, the term “humor” is used in conjunction with Cook‟s (2000) idea of “language play” (cf. Bell 2005; Tarone and Bonner 2001). For Cook (2000), language play is a combination of three features: 1) linguistic patterning of forms, 2) semantic reference to imaginary worlds, situations, characters, and events, and 3) pragmatic contextual meanings. In essence, these all include a wide range of activities, including jokes, songs, rhymes, verbal dueling, tongue twisters, puns and riddles, narratives and fictional stories, and play languages. According to some practitioners (cf. Bell 2005), obviously not all of these activities can be considered humorous all the time. As Bell (2005) points out, songs and rhymes may fall outside of the category “humorous language play,” (p.71) in that these they do not necessarily invoke laughter.

Sullivan (2000), too, defines humor as “play” that is “accompanied with laughter” (p. 122). This play, according to Sullivan, includes, “teasing and joking, puns and word play, and oral narratives (p. 122).

Sociolinguistic definitions tend to define humor from two different perspectives: the point of view of the speaker and the point of view of listener/audience (Holmes, 2000). In

10

regards to the former, something is humorous only when the speaker intends it to be humorous. Contextual, paralinguistic, and prosodic clues are important in determining mirthful intent. This definition can also include failed attempts at humor. The latter definition focuses only on the audience‟s interpretation. From this perspective, many practitioners propose laughter is the key auditory clue that determines if a stimulus is humorous or not. According to Norrick (1993), laughter can include a conventional “aw” or mirthless “haha.” Norrick (1993) adds that other things may elicit laughter, such as embarrassment and nervousness. The second definition usually excludes failed attempts at humor.

Finally, some researchers (i.e. Martineau 1972) use both speaker intention and audience interpretation in their definition. However, the speakers‟ intent must evoke an appropriate response.

In this thesis, I will include audiences‟ response, for the most part laughter, and speaker intent. I will discuss more precisely the definition that I will use for this thesis in Chapter 3.

2.1.5 Types of Humor in Literature

In this section I will briefly review some of the taxonomies of the types of humor that have been developed by researchers. For the most part, I am merely concerned with the form the humor takes. Literature abounds with discussions of such humor taxonomies and reviewing them all would not be very useful. So, basically, I chose a few that would appear to be more beneficial for pedagogical purposes.

Vinton‟s (1989) taxonomy of humor is as follows: (1) puns

(2) goofing around (3) jokes/anecdotes

11 (a) humorous self-ridicule

(b) bawdy jokes (c) industry jokes (4) teasing

(a) teasing to get things done (b) bantering—the great leveler

Although Vinton (1989) places jokes and anecdotes together, some researchers keep them apart (cf. Norrick, 1993). According to Norrick (1993), jokes differ from anecdotes because they end in a punch line; their aim is to elicit a single mirthful response from the listener/s. Anecdotes, on the other hand, have no punch line and, in contrast to jokes, offer several propositions that can elicit laughter from listeners. Norrick (1993) also proposes that jokes are more of a performance ; whereas, anecdotes are personal and tend grow out of personal experience.

Narratives differ from anecdotes in that they are funny stories about events that are not personal to the speaker (Norrick, 1993). These stories can be funny in their own right or the speaker may adopt a funny perspective on them (Norrick 1993). Narratives also have no punch line, and may offer several propositions that can elicit laughter.

Norrick (1993) places puns in a wide category of wordplay that also consists of spoonerisms, allusions, hyperbole, mocking and metaphors.

Norrick (1993) describes irony and sarcasm as basically the same thing. Definitions of irony/sarcasm include saying something different or the exact opposite of what is literally meant.

Norrick (1993) and Sullivan (2000) do mention teasing quite frequently; however, Boxer and Cortex (1997) discuss teasing more extensively. They describe teasing as a humorous statement directed at someone present in the conversation. This could either be directed at the

12

speaker or the listener. They also mention that teasing occurs on a continuum from “nipping to biting.” Nipping tends to bond individuals, whereas, biting can offend.

Hay‟s (1995) taxonomy of humor in spontaneous conversations presents some more categories of humor that are not identified by Norrick (1993) and Sullivan (2000). These include insults and self-depreciation. Insults occur when the speaker puts someone down. The humor usually occurs because the insult is unexpected. Self-depreciation occurs when the speakers puts him or herself down.

Finally, Morreall (1983,) presents a full taxonomy of humor that for the most part is based on incongruities. Most of these categories can be placed into the aforementioned categories. The only possible exception is mimicking. Mimicking is defined as copying something or someone closely with speech or gestures for humorous effect.

Fillmore (1994) provided a taxonomy of humor in academic discourse that includes amongst others, tongue-in-check comments and the use of inappropriate registrars. The former refers to comments that are not intended to be taken seriously. The latter refers to use of colloquial language mixed with academic language and vice versa.

In the context of Taiwan, Liao (2001) mentions that Taiwanese generally prefer three types of humor, wit, self-depreciating humor and word play. Xue (2010) explains that Chinese humor can be mostly characterized as joke-telling and funny show performing.

Later, I will outline the taxonomy used for this thesis. Some of it will be drawn from the literature and further modified to suit the Taiwan EFL classroom context.

2.1.6 Social Functions of Humor

The functions of humor can be studied from various points of view. However, in order to fully understand the functions of humor in the Taiwan University EFL context, it is best to borrow the framework set by Urios-Aparisi and Wagner (2008), which is drawn from the field of

13

pragmatics. They basically posit that in order to gain a full understanding of the functions of humor in the context of the classroom, it is important to investigate humor in the context of classroom discourse (Urios-Aparisi and Wagner 2008; from Kottoff 1998). Thus, the humor found in the classroom context tends to show similar characteristics to the humor used in our daily lives. With this in mind, the video-recordings for this research took place in weeks six though ten of the 2007 fall term. Therefore, in some cases there was time for the teacher-student, student-teacher, and student-student relationship to develop, and as a result the instructors and students were probably able to become more aware of each other‟s emotional, social, and values systems in regards to humorous interactions (Urios-Aparisi and Wagner 2008; from Kottoff 1998).

Therefore at this point it is important to understand the difference between the primary and secondary functions of humor (Attardo 1994, 323). The primary function of humor is to achieve communicative goals and be social. Attardo (1994) pointed out that humor has four basic social functions: social management, decommitment, mediation, and defunctionalization. Social management maybe specifically suitable for the classroom context as it can facilitate interaction and achieve social control. That is to say, humor can not only reinforce social bonds and

strengthen in-group relationships, but also be a social corrective. In the context of the EFL classroom in Taiwan this is particularly crucial as humor can be deemed a “face-saving device” to correct inappropriate or unacceptable behavior by fostering and creating common ground.

By decommiting, the speaker can carry less responsibility and deny any serious or harmful intention. By probing, the speaker can test and explore the reactions of the listener then determine if he/she wants to detract from the statement.

14

discourse, especially when critiquing someone or something or when taboo topics are discussed. Similarly, Martineau (1972) identifies three social functions of humor: consensus, conflict, and control. Consensus humor narrows the social distance between individuals and initiates the development of social relationships. Conflict humor allows us to introduce and foster conflict in an acceptable form. Ridicule is a key component of conflict humor. Control humor allows us to influence the behavior of others by expressing what cannot be expressed otherwise.

Pogrebin and Poole (1988) also identify three functions of humor. The first is solidarity: laughing at each other or at the same things shows we share a mutual understanding and a common perspective. Humor is also used as a strategy to explore and test attitudes, perceptions and beliefs of others in a non-threatening manner and without losing face. The third function of humor identified by Pogrebin and Poole (1988) is coping. Humor used in this way helps deal with circumstances outside our control. Fink and Welker (1977) also propose that humor is used as face-saving technique in embarrassing situations.

Also, Liao (2001, from Dai and Lao) pointed out that Taiwanese generally like to use self-depreciating humor and word play as it is entertaining and creates rapport. She also mentions that humor tends to be a pleasant reprimand.

In summary, research on humor is vast and I have only briefly covered some relevant material. It can be seen that some of the material is somewhat confusing and overlapping and there is need for more research in spontaneous and cross-cultural settings. As Norrick (1993) points out:

“Comparative studies of [humor] based on different social groups representing various ages, professions, races, and so on would certainly reveal other preferences in

15

The next section will look more closely at classroom humor.

2.2 Classroom Humor Research

So far, I have presented some of the theoretical frameworks of humor, discussed the

contemporary definitions of humor in Taiwan and the West, and have highlighted some of the types and functions of humor that have been presented in literature. I want shift away from these topics and now focus on what the literature says about humor in classroom contexts.

Historically in Taiwan, effective classroom management and teaching has perceptually been deemed strict and serious in nature, and that the use of humor in the classroom was

considered low-class (Liao, 2003). Kao, (1974, xxiii) explains that when Chinese tell jokes, they tend to use the metaphor pen-fan (or “spew the rice”), whereas people from the west tend to see humor as “hold the belly.” According to Liao (2001, 17) this may mean that Chinese view humor as merely “meal-time entertainment” (p. 17), and it should not be considered in serious and formal situations, which may include educational contexts, and in particular, classroom contexts in Taiwan.

However, over the last ten years or so, research in Taiwan has suggested other things. For example, Liao (2003) found that students in Taiwan at the university, high school, junior high and elementary school levels rank humor as a “key quality” of being a good teacher,

especially in the EFL classroom. Ho and Lin (2001, from Yue) sampled 1039 junior high schools student and seemed to find that situational humor production and humorous coping skills had a moderating effect on anxiety, insomnia, and social dysfunction. The results of the research mentioned above certainly do add to the growing body of research on classroom humor in Taiwan. Thus, it is the hope of this paper to contribute more by gathering qualitative and

16

that, I would like to discuss past methods of classroom research.

2.2.1 Methods of Classroom Research

Past methods of studying humor in classrooms have been based on three kinds: experimental studies, field studies, and questionnaires and surveys.

The most prominent experimental studies of classroom humor are perhaps Kaplan and Pascoe (1977) and Ziv (1988). Kaplan and Pascoe (1977) investigated the effects of humorous examples on students‟ comprehension and retention of lecture material. In this study, students were exposed to four versions of a 20-minute videotaped lecture: one serious lecture where no humor was present, one presented with humor related to the concepts of the lecture, one presented with humor unrelated to the concepts, and one lecture with a combination of non-related and non-related concept humor. A test of comprehension and retention was then given immediately after the lecture. Results of the study indicated that the use of humor did enhance retention of the concept related subject matter. Ziv (1988) undertook two semester-long experiments intending to explore the influence of humor on learning outcomes in higher education venues. In the first experiment, Ziv (1988) used two sessions of a fall introductory statistics course in which in one of the sessions, the experimental group was exposed to relevant concept humor whereas the other session, the control group, was exposed to no humor. The teacher who participated in the study underwent special training on using humor as a teaching strategy the summer prior to teaching the course. At the end the semester, Ziv (1988b) compared the final exam scores of each class. Ziv found that the experimental group had higher test scores.

The most prominent field research that examined humor in the classroom is perhaps Bryant et al. (1979) and (1980) and Nussbuam et al. (1985). The former study unobtrusively tape-recorded 70 undergraduate university classes: whereas, the latter study video-recorded 57

17

undergraduate university classes. The purpose of these studies was to show how often humor was used and what types of humor were used.

Numerous studies have also used questionnaires to examine humor (i.e Gorham and Christophel, 1991, Askildson 2005). The questionnaires vary in their approach. Some are looking specifically at types of humor used in classrooms, how often humor is used by instructors or ask for descriptions of instructors who the respondents thought were funny.

From a sociolinguistic point of view, the above methods of collecting data do not really shed light on how humor is actually used in classrooms. Even more striking is the paucity of research on classroom humor that has actually used video-taped data.

2.2.2 Taxonomies of Classroom Humor

Research on classroom humor has documented various classification schemes of humor. Bryant et al (1979) and Bryant et al (1980) identified six-categories of classroom humor: jokes, riddles, puns, funny stories, funny comments, and “other.” The “other” category was expanded to include visual and vocal humorous attempts such as a prolonged sneeze or mimicking of animal sounds (i.e. a professor making Donald Duck sounds). They also examined if the humor was sexual or non-sexual, hostile or non-hostile, if the humor “distracted from the educational point” of the class and if the humor was prepared or spontaneous. They also accounted for all

participants that were involved in the teachers‟ humor; whether it was the instructor; a student in the class, another person, or none, and whether the humor disparaged the instructor, a student in the class, or another person and/or group.

Downs, Javadi, and Nussbaum (1988) in their study of college teachers‟ use of verbal communication in the classroom used a different scheme to classify humor. They classified and coded the teachers‟ use of humor into a verbal coding scheme developed by Nussbaum,

18

Comadena and Holladay (1985). This coding scheme places each humor attempt into one of five different types of “play offs.” That is, the teachers‟ humorous comment was “played off” or directed toward the (1) self, (2) students, (3) others not in class, (4) course material (5) other object or thing. Two other categories were added that determined if the humor was relevant or not relevant to the course content. The results of the study indicated that there was an average o f thirteen humorous attempts per fifty-minute lecture. Results also indicated that most humor “played off” the course material and was related to the course.

Contrary to the previous coding scheme that was deductively derived, Gorham &

Christophel (1990) inductively developed a taxonomy scheme of humor incidents in the college classroom by using a grounded theory constant comparison method. In this study the student-participants were asked to observe the teachers use of humor over five class meetings and record the incidents as they happened in a diary. After the five class meetings the diaries were collected and each incident was transcribed and combined to generative categories for analysis. The results indicated 13 different types of humor that were used by instructors. Six of the thirteen categories were referred to as “brief tendentious comments directed at” (1) an individual student, (2) the class as a whole, (3) the university, department, or state, (4) world events or personalities or at a popular culture, (5) class procedures, or the topic, subject of the class, (6) at the self. The next four categories consisted of personal or general anecdotes or stories related to the self, or

subject/topic of the course. The last three categories consisted of jokes, physical or vocal comedy and other. Results in the study found that humor directed at the topic, subject of the course, or class procedures were mostly used.

Neuliep (1991) further developed yet another scheme for teachers‟ use of humor in the classroom after surveying 388 high school teachers in Wisconsin. In open-ended questions,

19

teachers were asked to describe their last use of humor in class. From this, Neuleip (1991) inductively derived a 20-item category scheme of the teachers‟ use of humor in the classroom. The taxonomy included five major sections: 1) teacher-targeted humor, 2) student-targeted humor, 3) external source humor, 4) untargeted humor, and 5) nonverbal humor. Within these sections, Neuliep listed six types of teacher-targeted humor: unrelated-related self-disclosure and embarrassment disclosure, related and unrelated teacher role-play, and teacher self-deprecation. Four types of student-targeted humor were also categorized: teasing in a non-hostile manner, teacher giving the student a friendly insult, a student role-play, and the teacher identifying a student error and joking about it. Untargeted humor included awkward

comparisons, joke telling, punning, and exaggerations told by the teacher. External source humor included historical humorous events, third party humor that was unrelated or related to the content, and natural phenomena humor. The last category was non-verbal humor that was

delineated as: affective display humor (i.e. teacher making a funny face) and physical body humor.

All these schemes add wonderful insight into the teachers‟ use of humor in the classroom; however, they are still somewhat limited. For example, in Bryant‟s et al. (1979 & 1980) six-category scheme, 38 of 234 humorous attempts were categorized as “other” and no further description of those humorous attempts was given. This, perhaps, indicates that the taxonomy may not be extensive enough. In addition, Bryant‟s et. al. (1979) study was conducted over one class session. The Nussbaum (1985) and Gorham (1990) studies were different in that one was deductively derived and one was inductively derived, however both of the taxonomies do not focus on the content of the humor and/or how the humor was used. All of the taxonomies, as Schmitz (2002) suggests, perhaps are not representative of foreign/second language classrooms

20

as these classes presumably have students and instructors from the same culture. Schmitz (2002) concludes that some of the humor items may not be appropriate for the second/ foreign language classroom. Moreover, few studies have investigated the use of student humor.

Currently, there is no research in Taiwan offering taxonomies of humor in the classroom.

2.2.4 Frequency of classroom humor

There are a few quantitative studies that have documented the amount of humor used in classrooms. Bryant et al. (1979) found that university teachers used humor on average of 3 times per 50-minute class—the most being 17. Nussbaum et al. (1985) found that university teachers used humor on average of 13 times per 50-minute class. Bryant et. al (1980) study found that teachers who used humor more often received high scores on the teacher evaluations.

To date, there appears to be no qualitative or quantitative studies that look at the amount of humor used in any classroom context in Taiwan.

2.2.5 Functions of humor is the classroom

The preceding classification schemes present various different methods of analyzing humor in the classroom. However, the most extensive amount of research on classroom humor focuses on the effect that humor has on the general classroom environment, and how that correlates with learning outcomes. To date, there is still much debate on both of these issue.

Some practitioners argue that humor has an effect on classroom “affective factors,” which in turn leads to increased student learning. The most significant research on this matter places humor within a larger set of communication behaviors, known as immediacy behaviors. Specifically speaking, immediacy behaviors are a set of non-verbal and verbal communication behaviors that enhance the closeness and reduce the social and psychological distance between

21

individuals, (Anderson, 1979). Originally, the concept made no specific reference to educational contexts; however, recently, there have been a number of studies that have evidenced immediacy having a positive effect on student cognitive learning and affecting learning outcomes in

classrooms (Anderson, 1979; Gorham, 1988; Gorham and Christophel (1990); Richmond (1987). Specifically, Gorham and Christophel (1990) found that more immediate teachers used more humor than nonimmediate teachers and the teachers‟ use of humor was related to learning. Gorham and Christophel (1990) conclude that because teachers are likely to use humor “to reduce tension, to facilitate self-disclosure, to relieve embarrassment, to save face, to disarm others, to alleviate boredom, to entertain, and to convey good will,” the student teacher

relationship is enhanced resulting in positive cognitive learning outcomes. Welker (1977) also suggested that humor can serve as an “attention getter” and can be used to

create a relaxed atmosphere within the classroom. Welker (1977) suggested one of the best ways to establish this trait is for the teacher to demonstrate the ability to laugh at his/her mistakes.

Welker (1977) points out “to err is human” and in many cases “to err is to be humorous.” Many language educators have proposed that humor has a substantial place in L2 classrooms, in

particular, the communicative classroom (i.e. Askildson, 2005, Berwald 1992, Deniere 1995, Toasta 2002, and Trachtenberg, (1979). Deniere (1995) discusses at great length the fundamental differences between traditional classrooms and foreign language classrooms: the foreign

language classroom, in contrast to traditional classrooms, is a highly interactive context in which learners are expected to communicate in a language which, for the most part, is novel and

unfamiliar in front of their peers. This, as some researchers point out, may lead to an excessive amount of tension, anxiety, and low-self esteem that may consequently hinder learners‟ language production. This point has been of significant study in L2 research. For example, Krashen‟s

22

(1982) “Affective Filter Hypothesis” asserts that anxiety and tension can “keep the input from getting in,” (p. 25) Thus, he adds, “the newer methods, the more successful ones, are the ones that encourage a low filter. They provide a relaxed atmosphere where a student is not on the defensive.” As a result, many researchers postulate humor can be helpful in this context. Furthermore, as Deniere (2005) points out, through humorous situations created by teachers, students and/or materials, learners will be able to construct ideas and behaviors in creative and original ways, thus enhancing projecting their identity in the TL.

For this research I will draw from the above functions to explain the functions of humor in the Taiwan EFL university classroom in a similar fashion to Urios-Aparisi and Wagner (2010). In their study they used the above functions of humor in the context of the “World” language classroom. In their study, they found that humor played a significant role in classroom

management. In this regard, they found that humor was used to defuse behavioral or language mistakes made by students, to call on students, and to get their attention. I will use a similar model in my study.

2.3 Humor as a Pedagogical Tool in the Language Classrooms

In this section I will briefly examine some of the literature that describes how humor can be used as a pedagogical tool in foreign language classrooms. Most of this research is merely perceptual and does lack empirical evidence. However, more and more studies are popping up that are showing specifically how humor could be used as a pedagogical tool, specifically Ackildson (2005), Deneire (1995), Berwald (1992) and Trachetenberg (1979), among others. This research does represent a basis for exploring the use of humor in L2 classrooms in Taiwan. The literature mainly focuses on humor to present and explain the linguistic, cultural, and pragmatic aspects of the target language. Most research that discusses how to use to humor in the L2 classroom tends

23

to illustrate how jokes can be used as a tool to teach the discrete structural aspects of the target language. They point out that the humor in jokes often depends on the phonological, morphological, lexical, and syntactic elements of a language. For specific descriptions please see Deniere (1995) and Ross (1998, Chapter 2).

Berwald (1992) also explains how teachers can use jokes in the foreign language classroom to reinforce syntactic, phonetic, and lexical aspects of the TL. He offers numerous examples of how to take simple English jokes and translate them into French. In addition to the syntactic, phonetic and lexical elements, Vizmuller (1979) suggests that jokes and humor in the classroom environments provide both cognitive and creative benefits for language learners as they allow students to divert from the formulaic expressions that they are used to in the language classroom. The cognitive aspect refers to recognizing the ambiguity; whereas, the creative aspect focuses on the creation of the incongruity.

Trachtenberg (1979) specifically suggests how riddles and narrative jokes can be used as mini grammar, lexical, and speech pattern lessons. For example, she explains how riddles and joke questions can be used to reinforce positive and negative interrogative forms. For example, “What has four legs and flies? A garbage truck,” (p.93). Not only does this joke present the interrogative form, but it also demonstrates the lexical ambiguity of the word “flies.”

Additionally, Trachtenberg, (1979) discusses how the beginnings of narrative jokes can be used to teach typical native-English speaker speech patterns. As she stresses, the opening of jokes must have a precise form, for example:

A guy walks into a psychiatrist‟s office … A man is driving down a freeway … An old lady is walking along the beach …

24 (Trachtenberg, 1979, p. 95).

Trachtenberg (1979) admits that there are many different forms narrative jokes can take, but she suggests that teachers should be aware of the “verbal strategies” that these jokes offer. For example, they are often told in the present tense, they offer the use of demonstratives, and the exact description of the person and situation.

Language instructors also posit that the use of humor in language classrooms can enhance learners‟ culture competence in and pragmatic knowledge of the target culture. Berwald (1992) expounds the importance of humor when teaching language and culture. In particular, he

explains that using humorous examples of cultural faux pas in the language classroom is a great way to learn about the target cultures‟ unwritten social rules. Berwald (1992) himself states “the humor caused by the clash of cultures serves as an excellent teaching device that can prepare students to function in another setting,” (p 189). Berwald (1992) also suggests the use of comics and humorous advertisements as a great way to transfer cultural clues to students.

Trachtenberg (1979) specifically contends that jokes and humor represent a culture and when used in an L2 classroom, can serve as important conveyors of the target cultural values. Trachtenberg (1979) argues that some jokes may be considered too culture-bound, Schmitz (2002) argues that theoretically all jokes and humor could be considered appropriate in the classroom in that jokes and humor serve as a mirror of the target culture‟s socio-cultural norms and values and by introducing humor in the classroom, students can reflect critically on the humor of the target culture.

Deniere (1995) contends that humor is an important part of communicative competence and that learners should learn what situations are suitable for joking and what topics are appropriate to joke about in the TL. In order to do this, learners must have a certain amount of

25

cultural knowledge. Humor, he argues, fosters in-group relations and is often geared at out-groups. As a result, it is extremely difficult for language learners to learn the humor of the target culture. Deniere (1995) proposes in order to construct and understand humor in an intercultural context, language learners need to learn to appreciate differences between cultures and to view the target culture as the people of the target culture do. Specifically he proposes learners need to be aware that: “1) every culture has its own internal coherence, integrity, and logic, 2) all

cultures are equally valid and 3) all people are at least partially culture bound,”(p. 295). He mentions this is not particularly easy, and learner must overcome many obstacles. However, as Harder (1980) puts it “in order to be a wit in a language, you have to be a half wit.”

Practitioners have also put forth that humor can be a formidable tool to teach socio-pragmatic concepts of the target language. Specifically, Askildson (2005) draws on Berwald‟s (1992) examples of funny cultural faux pas as an effective way to teach the pragmatic norms of the target language. He mentions that by observing violations of norms, learners will become aware of the norms themselves. Askildson (2005) offers a rather humorous example:

“An illustrative example in an English context might include a humorous

anecdote of a newly arrived immigrant to the United States who is casually asked, “How are you?” by an American colleague—out of simple politeness and with the cultural expectation of a short or one word response, if any at all—but responds with a ten minute saga of his/her minor problems of the day,” (p. 53).

This example of humor, according to Ackildson (2005), allows students to “enjoy a comedic episode through teacher assisted understanding of the proper and expected pragmatic use of a

26

greeting,” (p. 54). Moreover, Trachtenberg (1979) explains that beginnings of oral narratives can also be used to teach the common opening lines of jokes such as “Did I ever tell you about …” or “Did you ever hear that one about …?” in which the listener must respond with a “no, go ahead tell me,” or “yeah, I heard that one.” By giving these examples to students, students can became aware of native speaker joking interactions in which “go ahead” gives the speaker the message to proceed and tell the joke. Alternatively, “yeah, I heard that one,” gives the indication to move on the something else.

To sum up, previous research on classroom humor has yielded several classification schemes that have shed light on the types of humor that are used in classrooms contexts. Past research has also evidenced that humor is used quite often in university classrooms. Needless to say, there appears to be some degree of uncertainty as to how humor actually benefits classroom contexts. For instance, it is still unclear if humor assists in the retention of new information. Numerous studies have been conducted; however, because of unsystematic researcher methods, it is hard to have a consistent understanding of how humor affects learning outcomes.

A majority of the research on classroom humor tends to focus on the effect that humor has on the classroom “affective” environment. Immediacy, which is a behavior that enhances the closeness between two individuals, currently appears to be the most significant framework in which researchers investigate humor in classrooms. They posit that humor used to reduce tension, to facilitate self-disclosure, to relieve embarrassment, to save face, to disarm others, to alleviate boredom, to entertain, and to convey good will enhance the student teacher relationship, resulting in positive cognitive learning outcomes.

Closely linked to the immediacy framework, some EFL practitioners have documented that classroom humor has the ability to get students‟ attention, relieve tension, make learning more

27 fun, and make the class more positive.

There are also discussions in literature about how too much or inappropriate humor can have negative effects on the classroom “affective” environment.

In regard to L2 classroom humor research, empirical studies are still lacking. The literature for the most part offers examples of how humor can be used in language classrooms to sensitize learners to the linguistic, cultural, and pragmatic aspects of the target language. However, currently, there is very little research available that actually offers examples of what types of humor and how humor is used in L2 classrooms. Thus, numerous researchers are calling for a more comprehensive examination on how humor is used in L2 classrooms (i.e. Deniere 1995; Schmitz 2002).

28

CHAPTER THREE

METODOLOGY

3.1 Overview

This section will discuss the methodology that employed in my study. The main goal of my study is to identify categories of humor that are employed in the EFL classrooms in Taiwan. More specifically, I hope to explore what types of humor that are employed in the EFL classrooms in Taiwan by instructors and non-native English speaking students. In addition to identifying the types of humor, I will also examine how humor is accomplished inductively and in accordance with the literature review.

3.2 Participants

All students that participated in this study are, for the most part, ethnic Taiwanese and were in their first or second year of university study. They had been learning English for at least six years.

The instructors participating in this study are aged 25-52. Four had earned doctorates from American universities. Eight of the instructors had earned master‟s degrees: four of which had been earned in Taiwan; two had been earned in the USA; all instructors had at least 3 years of experience teaching English in Taiwan.

I approached, in person, all twelve instructors and asked them if they could help me with data collection for my research. I told them that video recordings of classroom interaction were needed and that I was looking for NEST and NNEST classes to video record. I discussed the problems and constrictions that I was having and asked them if they could think of anyone that would not mind helping me. According to Hay (1995), this method has many advantages. Firstly, many of the instructors know me or were approached by someone who knows me and therefore

29

were more comfortable about discussing the project than if approached by someone they did not know. Secondly, I knew most of the instructors which made it easier for me to transcribe their humor. I was not in the classroom at the time of the video recordings.

3.3 Procedures of Collecting Information

For this study, consistent with the current trends in humor research that I have adopted more ethnographic research methodologies, such as using audio and/or video tape recordings of spontaneous speaking instead of questionnaires or surveys, (Holmes, 2000). Recording in the classroom can be very difficult, particularly if you are trying to be as unobtrusive as possible to allow for more naturalistic data. In setting up the recording equipment, I arrived at the class as early as possible. If there was a class before the class that I was recording, I set the video camera up before that class. Then I told the instructor of that class that I was not recording their class and it was for another class. This only happened twice, as most of the classes I was recording were back to back, say one from 8-10 in the morning and the other was 10-12, or there was no class before the class I was recording. The video camera was placed in the back of each classroom. During the break time of the classes a student of the class was responsible for switching the cassette in the video camera; this was arranged prior to the class.

The data were collected from two public universities in northern Taiwan. A total of 12 two-hour undergraduate English courses were recorded twice in week‟s six to eight in the fall of 2007. This resulted in a total of 48 hours of data. Five of the classes consisted of English majors and rest had students with various other majors. Table 1 presents the list of classes recorded.

30 Table 1 List of Recorded Classes

Name of Class Instructor No. of students Total Hours English Conversation Taiwanese Instructor 30 4

English Conversation Taiwanese Instructor 30 4 English Conversation Native English Speaker 30 4 English Conversation Native English Speaker 20 4 English Four Skills Taiwanese Instructor 20 4 English Four Skills Native English Speaker 20 4 English Four Skills Native English Speaker 20 4 English Four Skills Native English Speaker 30 4 English Four Skills Taiwanese Instructor 30 4 English Four Skills Taiwanese Instructor 30 4 English Presentation Native English Speaker 20 4 English Presentation Taiwanese Instructor 30 4

I was able to record all classroom speech events. The classroom speech events included: teacher-student discussion, teacher lecture, student presentation, and student role plays. At first, I thought it would be difficult to record student group discussions. However, it was quite easy as most of the time the instructor of the class walked around the class engaging in discussions, as a result I was able to record and decipher the interaction.

3.4 Participant Knowledge of the Study

Three of the twelve instructors were aware that I am interested in humor, although they did not know exactly what I was looking for. In fact, during the interview session of my research, I

31

asked the instructors about being videotaped. One instructor said “I was totally unaware of the recording, once you‟re teaching you just start teaching, plus I still don‟t remember what days you were recording.” Another instructor said “I have been recorded so many times, it has become natural for me, and in fact many students have recorded my class this term.” And the final instructor stated “I am not sure what you are looking for, I forget, oh yeah something about student interaction.” I responded “no humor,” to which the instructor responded “oh, I thought you changed your topic.” The rest of the instructors and all of the students in all the classes were unaware of my exact topic. Basically all students and instructors were told that the data I was collecting was for research investigating classroom interaction. After all the recordings were complete, I gave all the participants a more complete description of the project. The signature statement is as follows

All the instructors mentioned that the video recordings did not affect or create any problem or havoc in their classes.

3.5 Data Analysis

Here, I will discuss how I will identify the humor. For the most part, the definitions overlap with the definition defined in the literature review.

3.5.1 General Laughter

To identify humorous instances in the EFL classroom, I was for the most part interested in identifying laughter; however, it is important to remember that, as Achakis and Tsakona (2005) point out, the absence of laughter does not always mean the absence of humor. This is in

accordance with Liao (2001) who mentioned that Taiwanese tend to not laugh out-loud that often. However, this was not the case in this study as laughter was for the most part present, and at time,

32

there was very loud laughter. In my data, I considered it humor if there was some laughter (Holmes, 2000) For instance, if the instructor made a comment to one student and that student laughed, I counted it as a humorous incident. If the teacher made a comment to a group of students and only some students laughed, this too was counted as a humorous incident. If a comment was made to the entire class and most or all of the students laughed, I counted it as humorous incident. Finally, if a comment was made to the entire class, and some of the students laughed, then I counted it as a humorous incident.

3.5.2 Intent of the Speaker

With laughter, I also took into account the speakers‟ tone of voice (Holmes 2000). For instance, sudden changes in pace, pitch, and/or rate of an utterance and use of a laughing or smiling voice were taken into consideration. The use of a video-recorder assisted in identifying mirthful facial expressions and as well as other paralinguistic features that I observed. I also paid attention to speaker laughter as it could indicate humor, (Jefferson 1979) Furthermore, I took into account marked lexical choices and/or unusual voices as they may indicate an intention to be humorous, (Bell, 2005). Norrick (1993) and Hymes (1974) both suggest that if the speaker refers to an utterance by its folk name and/or uses certain formulaic expressions this can signal attempts at humor. For example, using phrases such as “That was really funny,” or “I was just kidding” can also indicate humor.

3.5.3 Point of View of the Researcher

Holmes (2000) points out that the point of view of the analyst is also an important consideration when identifying instances of humor. That is to say, when working with audio and

33

videotape data, the analyst‟s identification of instances of humor becomes increasingly prolific. The ability to stop and play back data for further analysis allows for a more objective view of the humor. I am fully aware that the above methods may not be comprehensive enough; I believed they were adequate enough to allow me to correctly identify humorous episodes in the EFL classroom in Taiwan. Moreover, as Bell (2005) asserts, I was fully aware that my own cultural bias and preferences may have caused me to misinterpret humorous attempts, or select instances of humor that were not intended to be mirthful by the speaker(s) and/or any participants‟

involved.

In this respect, in the six classes in which the Taiwanese instructors were present, two native Mandarin speakers helped me transcribe and identify humor. Basically, I watched the recordings myself in an attempt to find the humor, then they separately watched the videos and marked the time they felt there was a humorous incident. This was quite time consuming, however, when we came together to compare, our agreement was 100% the same. I then took their data and interviewed the Taiwanese instructors and students to double check the humor and it was 100% correct.

All humorous incidents by students and the instructors were transcribed and coded textually by the researcher. As there were NNS participating in this study, material presented in the NNS native language was transcribed by two (2) researchers who have the same native language. In addition, the material preceding and following the humor was transcribed to provide adequate context. To confirm that the humorous incidents were indeed humorous, the instructors and two students from each class were asked to review the material to determine if the material was indeed humorous. Because of limited time, not all humorous incidents were

34 accurate in 98 percent of the incidents.

With regards to coding each humorous incident, each event that has a response or intent that includes laughter, will be counted as one humor incident (refer to Holmes 2007). For example, the following transcript includes three humor incidents.

*INS: What is inside the red envelope..

*S: Money The red envelope…nice….and what

*INS: Money…money is good….Taiwan is so useful (smiling) [students laugh]

*INS: in America you get gifts you don‟t really want [instructor laughs]…but in Taiwan you just get money very useful. In the US, you always get what your parents think it‟s useful like really warm sweaters that are very ugly you never want to wear but you because it‟s a Christmas gift you have to “yeah, thank you [instructor laughs] [Students laugh]

With regards to third-party humor, which also tended to be long and drawn out, I only included it as one humor incident. This was basically because most of the third-party humor involved one basic punch line. However, if an instructor or student showed three separate funny pictures in a presentation, then I counted that as three incidents.

35

CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS

4.1 Overview

In this section, I will present the results of my study. I will begin by looking 1) how much humor there is used in the Taiwan EFL university classroom? 2) What types of humor are used in the university classroom? 3) How is the humor used and is there any evidence that humor is used as a pedagogical tool?

4.2 Research Question 1

How much humor is used in the Taiwan EFL university classroom?

4.3 Results

Table three shows the number of humor events in each of the recorded classes. Obviously, there was more humor present in some classes than others; however, in all of the classes, humor was presentwith the most class having 101 instances of humor and the least having 15.