台灣大學生的英語關係子句習得

全文

(2) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The accomplishment of this thesis is due to many people’s help. I would like to say “thank you” to the following people for their having confidence in me and supporting me in the journey of my thesis writing. First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my adviser, Dr. Shyu, Shu- ing, for her warm and continuous support in the preparation and writing of the thesis. She was always there to listen, to talk to me about my ideas, to give advice, to proofread and mark up my papers and chapters, and to ask me good questions to help me think through my problems. Without her warm encouragement and constant guidance, I could not have finished this thesis. I am also grateful to the committee members of my oral defense, Dr. Lin, Yuh-huey and Dr. Chang, Lan-hsin, who gave insightful comments and reviewed my work on a very short notice. Their precious comments and constructive suggestions helped me a lot in the refinement of my work. My sincere thanks also go to Dr. Yang, Tai-hsiung, Teacher Chen, Szu- yu, and Teacher Tzen, Tsai- mei, whose students served as the subjects in my study.. Without. their generous assistance, I could not be able to collect the data for my study so quickly and successfully.. I am also indebted to Dr. Chang, Fu-chuen, who gave me. good advice when I had question about statistics. I also thank the instructors and my classmates in the Department of English at NSYSU, and my advisor, Teacher Chang Chieh-hsiang, in Shih Chuan Elementary School in Kaohsiung, for giving me generous help whenever I was in need. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my fa mily: my parents, for unconditional support and encouragement to pursue my interests; my husband for believing in me and listening to my complaints when I was struggling with my writing. i.

(3) 摘要 論文名稱:台灣大學生的英語關係子句習得 校所組別:國立中山大學外文系碩士班 畢業時間:九十四學年度第一學期 指導教授:徐淑瑛 教授 研究生:周怡慧 論文摘要內容: 本論文旨在研究台灣大學生的英語關系子句習得,藉由三個不同理論基礎的 假設 NPAH (Noun Phrase Accessibility Hypothesis)、PDH(Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis)與 SOHH (SO Hierarchy Hypothesis)以了解學習者在習得過程中會受 到哪些因素的限制。這些因素可能包括語言普遍性原則(universal principles),母 語,以及人類的認知系統(human cognition)。同時,本研究也將分析學習者在形 成英語關係子句時會採用哪些迴避策略(avoidance strategies)。 本研究對象為 84 位中山大學非英語系的學生。以三種測驗方式:合併句子 (sentence combination test)、中翻英(Chinese-English translation test)以及文法是非 判斷(grammaticality judgment test)引出 12 種類型的英語關係子句:SS, SO, SIO, SOPREP, SGEN, SOCOMP, OS, OO,OIO, OOPREP,OGEN, 以及 OOCOMP。 本研究發現大致上三個假設 NPAH、PDH 與 SOHH 皆獲得支持。語言普遍 性原則(universal principles),母語,以及人類的認知系統(human cognition)都是有 可能的限制因素。學習者在習得過程中普遍覺得中央嵌入句(center-embedded sentences)與 OCOMP 關係子句是較困難的,同時在也最常在這兩種情況使用迴 避策略(avoidance strategies)。. ii.

(4) ABSTRACT. This study set out to examine the Taiwan college students’underlying knowledge of English relative clauses in attempt to see what the factor(s) is/are that constrain(s) the learners’ language acquisition process, whether it is the universal factor, the native language, or human general problem solving skill. Three predictor hypotheses were used in this investigation: NAPH, PDH, and SOHH, which are motivated by different theoretical backgrounds. The NPAH is based on the typological markedness, the PDH is based on the notion of human limited capacity of short term memory, and SOHH the combination of NPAH and PDH, and the structural difficulty of relative clause.. The data from 84 non-English major college students of NSYSU were. elicited using three kinds of tasks: sentence combination test, Chinese-English translation test, and grammaticality judgment test. 12 types of English relative clauses were analyzed in this study, namely SS, SO, SIO, SOPREP, SGEN, SOCOMP, OS, OO,OIO, OOPREP,OGEN, OOCOMP. In addition, the learners’avoidance strategies were extensively analyzed to see what was actually avoided as they were engaged in the formation of English relative clauses. Implicationally, the results suggest that Universal Grammar may be still operative in the minds of the adult FL language learners. Overall, we have the following findings: 1. The learners’ acquisition of relative clauses is largely constrained by the universal markedness by NPAH, except GEN, and the order between IO and OPREP. 2. The retention of pronoun is largely constrained by the linguistic universals of NPAH, but Chinese also has certain influence on the learners’choice of supplying resumptive pronoun. 3. The learners largely did experie nce more difficulty in center-embedded relative clauses, which matches PDH. iii.

(5) 4. Largely, SOHH is a valid prediction of the learners’ acquisition of relative clauses. 5. The learners tended to avoid relativization on the positions low on the NPAH, except GEN. 6. The learners did frequently avoid OCOMP relatives and center-embedded relative clauses.. iv.

(6) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement ..................................................................................................i Chinese Abstract .....................................................................................................ii Abstract ...................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents ..................................................................................................v List of Tables ..........................................................................................................viii List of Figures .......................................................................................................x. CHAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION. 1.1 Background and motivation ............................................................................1 1.2 Three predictor hypotheses .............................................................................3 1.2.1 Noun phrase accessibility hierarchy hypothesis (NPAH) ...................3 1.2.2 Perceptual difficulty hypothesis (PDH) ................................................6 1.2.3 SO hierarchy hypothesis (SOHH).........................................................8 1.2.4 Summary of the three hypotheses .........................................................10 1.3 The role of L1 ...................................................................................................10 1.4 Purpose of the study..........................................................................................12 1.5 Signifiacnce of the study...................................................................................13. CHAPTER TWO. LITERATURE REVIEW. 2.1 English Relative Clauses .................................................................................15 2.1.1 Definition ............................................................................................15 2.1.2 Head- initial ..........................................................................................16 2.1.3 Rrelativization process ........................................................................16 2.1.4 Relativization strategies ......................................................................17 2.1.5. Relative pronoun variables and resumptive pronoun...........................18 2.1.6 Center embedding and right embedding ...............................................19 2.2 Chinese Relative Clauses..................................................................................20 2.2.1 Definition ............................................................................................20 2.2.2 Head-final ............................................................................................20 2.2.3 Relativization process and relative marker ...........................................21 2.2.4 relativizable positions .........................................................................22 2.2.5 resumptive pronoun ............................................................................23 2.3 Similarities and Differences between English and Chinese relative clauses ....24 v.

(7) 2.4 Previous studies in the acquisition of relative clauses ......................................26 2.4.1 Acquisition of English relative clauses and relative clauses in other languages...............................................................................................27 2.4.2 Summary...............................................................................................36 2.4.3 Acquisition of Chinese relative clauses ................................................40 2.4.4 Summary...............................................................................................44. CHAPTER THREE. METHODOLOGY. 3.1 Research questions ............................................................................................45 3.2 The subjects.......................................................................................................46 3.3 Research design.................................................................................................46 3.4 The relative clause type tested ..........................................................................48 3.5 Measuring instruments ....................................................................................50 3.5.1 Combination task ................................................................................51 3.5.2 Translation task ...................................................................................51 3.5.3 Grammaticality judgment task ............................................................53 3.6 Procedures .......................................................................................................54 3.7 Scoring ............................................................................................................56. CHAPTER FOUR RESULTS 4.1 The accuracy order of relative clauses ..............................................................59 4.1.1 Sentence combination test.....................................................................59 4.1.2 Chinese-English translation test ..........................................................61 4.1.3 Grammaticality judgment test .............................................................63 4.1.4 Summary for the results of the accuracy order .....................................64 4.2 Resumptive pronoun .......................................................................................66 4.2.1 Sentence combination test.....................................................................66 4.2.2 Chinese-English translation test ..........................................................68 4.2.3 Grammaticality judgment test .............................................................69 4.2.4 Summary...............................................................................................72 4.3 Avoidance strategies ........................................................................................72 4.3.1 Sentence combination test.....................................................................72 4.3.2 Chinese-English translation test ..........................................................75 4.3.3 Summary .............................................................................................77. vi.

(8) CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION 5.1 The main findings from the research results .....................................................84 5.2 The unexpected result in grammaticality judgment test ...................................85 5.3 GEN and IO and OPREP relatives ....................................................................86 5.4 The interference of Chinese ............................................................................88 5.5 The implication of UG ......................................................................................90 5.6 Summary and Conclusion ...............................................................................92 REFERENCES ......................................................................................................95 APPENDIX ..........................................................................................................102. vii.

(9) LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1 Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy ........................................................4 Table 1.2 Example sentences for pronoun retentions ................................................5 Table 1.3 Typological patterns for retention or deletion of pronominal copies in relative clauses ..........................................................................................6 Table 1.4 Order of difficulty predicted by PDH ........................................................7 Table 1.5 Order of Difficulty by SO Hierarchy Hypothesis ......................................9 Table 1.6 Summary of the Three Hypotheses. ...........................................................10 Table 2.1 Center embedding in English relative clauses ...........................................19 Table 2.2 Right embedding in English relative clauses .............................................19 Table 2.3 Left embedding in Chinese relative clauses ...............................................23 Table 2.4 Center embedding in Chinese relative clauses ...........................................24 Table 2.5 Relative clause patterns in English and Chinese ........................................25 Table 2.6 The order of acquisition in the three hypotheses........................................32 Table 2.7 Summary of Schumann’s study..................................................................34 Table 2.8 Order of difficulty of English relative clauses in Izumi’s three tasks ........36 Table 2.9 The Accessibility Hierarchy for –Genitive and +Genitive.........................38 Table 2.10 Summarization of the studies on English relative clauses .......................38 Table 2.11 Four basic constructions of relative clause ..............................................41 Table 2.12 The order of difficulty as predicted by the three hypotheses ...................41 Table 2.13 The order of difficulty of Chinese relative clauses in the four studies ....43 Table 3.1 Advantages and disadvantages of cross-sectional design ..........................48 Table 3.2 12 types of relative clauses in the three tasks in this study.....................49 Table 3.3 The Accessibility Hierarchy for –Genitive and +Genitive (Repeated) ......50 Table 3.4 Three categories of errors in the grammaticality judgment task ................54 Table 3.5 The categorized avoidance strategies .........................................................58 Table 4.1 Total correct responses on sentence combination test by relative clause type and Matrix position type ....................................................................60 Table 4.2 Total correct responses on Chinese-English translation test by relative clause type and Matrix position type .........................................................62 Table 4.3 Mean accuracy scores on Grammaticality judgment test by relative clause type and Matrix position type ....................................................................64 Table 4.4 The order of accuracy of relative clauses in the three tests........................65 Table 4.5 The order of accuracy of relative clauses considering the matrix NP and relative pronoun in the three tests ..............................................................66 Table 4.6 Comparison of the orders in three tests against the three hypotheses ........66 viii.

(10) Table 4.7 Number of the resumptive pronouns on sentence combination test by relative clause type and Matrix position type ............................................68 Table 4.8 Percentage of resumptive pronouns on Chinese-English translation test by relative clause type and Matrix position type .......................................69 Table 4.9 Percentage of resumptive pronouns on Grammaticality judgment test by relative clause type and Matrix position type ............................................71 Table 4.10 The order of resumptive pronoun in the three tests..................................73 Table 4.11 The frequency of avoidance in the subject matrix position on sentence combination by relative clause type and avoidance type .........................74 Table 4.12 The frequency of avoidance in the object matrix position on sentence combination by relative clause type and avoidance type .......................74 Table 4.13 Total number of avoidance on sentence combination test by relative clause type and matrix position type........................................................74 Table 4.14 The frequency of the avoidance in the subject matrix position on translation test by relative clause type and avoidance type .....................76 Table 4.15 The frequency of the avoidance in the subject matrix position on sentence combination by relative clause type and avoidance type ........76 Table 4.16 Total frequency of avoidance on translation test by relative clause type and matrix position type...........................................................................76 Table 4.17 The total number of avoidance by avoidance type...................................79 Table 4.18 Summary of the avoidance order in the two tasks ...................................79 Table 4.19 Example of the learners’avoidance .........................................................79 Table 5.1 The accuracy order in previous studies......................................................88. ix.

(11) LIST OF FIGURES Figure 2.1 Percentage of sentences correct on combining task (all group) ...............28 Figure 4.1 Percentage of correct respones on sentence combination test by relative clause type and matrix position type........................................................61 Figure 4.2 Percentage of correct responses on Chinese-English translation test by relative clause type and matrix position type...........................................63 Figure 4.3 Percentage of the mean accuracy scores on Chinese-English translation test by relative clause type and matrix position type. ..............................64 Figure 4.4 Mean number of the pronoun retention on sentence combination test by relative clause type and matrix position type...........................................68 Figure 4.5 Mean number of the pronoun retention on Chinese-English translation test by relative clause type and matrix position type. ..............................70 Figure 4.6 Mean number of the pronoun retention on grammaticality judgement test by relative clause type and matrix position type. ..............................72 Figure 4.7 The total number of avoidance by relative clause type on sentence combination test .......................................................................................75 Figure 4.8 The total number of avoidance by relative clause type on Chinese-English translation test ..........................................................................................77. x.

(12) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION. 1.1Background and motivation. Relative clause has attracted the attention of a lot of SLA researchers and ESL and EFL educators due to its complex syntactic structures (Gass and Selinker, 2001), and hence the learning problem to the language learners. Keenan and Comrie (1977) looked into fifty languages in the world and generalized Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy (NPAH), hypothesizing that there is an acquisition order of various relative clauses owing to the different difficulty level each relativizable position takes in the hierarchy.. This hypothesis gives rise to a large amount of studies dedicating to. seeing whether the implicational hierarchy as predicted by NPAH constrains learners’ acquisition of relative clauses (e.g. Gass, 1979, 1980; Hyltenstam, 1987, 1990; Pavesi, 1986; Izumi, 2003; Cook, 1996; Doughty, 1991; Eckman, 1991).. While NPAH. concerns only the positions of the noun phrase within the relative clause, there is also a consideration taken in where the noun phrases are in the matrix clause, as in Kuno’s (1974) Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis (PDH), which assumes that center-embedded relative clauses are more difficult to process than right-embedded one s.. A third. hypothesis that is of concern in terms of relative clause acquisition is SO Hierarchy proposed by Hamilton (1994). Cook (1993) has succinctly differentiated NAPH from PDH by indicating the former as being linked to implicational universals of language and the latter as associated to constraint of language processing.. On the other hand, SOHH takes. account of both the center embedding discontinuity and phrasal boundary 1.

(13) discontinuity, which, as explained by O'Grady and Choo (2003) are responsible for the processing difficulty of various relative clauses. The importance of English relative clause for Chinese learners has been clearly pointed out by Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999), who stated that relative clause is crucial because of its high frequency in both spoken and written form, its complex construction, and its different structural configuration between English and Chinese. Specifically, the difference between Chinese and English relative clause poses three dimensions of difficulty for Taiwan EFL Learners, namely 1) position, 2) relative pronoun, and 3) pronominal reflex (Schachter, 1974).. The first dimension. arises due to the different branching direction of the two languages in question, where the relative clause follows the head NP in English, and the relative clause precedes the head NP in Chinese.. Apparently, Taiwan EFL learners are facing a no easy task of. learning English relative clauses, the problems being the complex syntactic structure of the relative clause itself, the distinction in the head direction, and other aspects between English and Chinese. Although, a bulk of research focuses on the acquisition of relative clauses, the empirical results have never been conclusive and consistent. Some of the problems may be linked to the theoretical dimension (Tsao, 1990; Jones, 1990 in Ellis, 2003). Some may be methodological as Izumi (2003) note that different measuring instruments may confound the results. This study thus aims to see whether the three hypotheses mentioned above can predict Taiwan EFL learners’acquisition of relative clauses, to further Izumi’s (2003) research. In addition, the role of the native language as manifested in learners’avoidance behaviors will be extensively examined.. 2.

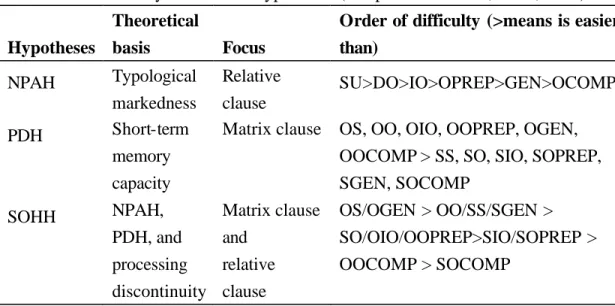

(14) 1.2 The three predictor hypotheses. In the acquisition of relative clauses, three hypotheses are frequently tested, namely, Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis (Keenan and Comrie, 1977), Perceptual Differential Hypothesis (Kuno, 1974), and SO Hierarchy Hypothesis (Hamilton, 1994). This section will go through these three hypotheses in detail in order to provide a theoretical background for the study.. 1.2.1 Noun phrase Accessibility hierarchy hypothesis (NPAH). Within Greenberg’s (1966) typological framework, Keenan and Comrie (1977), by examining some fifty languages in the world, generalized several linguistic universal constraints on relative clause formation.. Several claims are important in. this Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis. First, it is generalized that the various grammatical functions that noun phrases can fulfill in the relative clauses form a hierarchy (Table 1), in which the subject, being the easiest to relativize, takes the highest position, and the object of comparative, being the most difficult to relativize, takes the lowest position. Note that it focuses on the grammatical function the relative pronoun serves in the relative clauses only, not involving the head NP in the matrix sentence. For example, the noun phrase, teacher, in Jerry likes the teacher who explained the answers to the class, functions as the subject in the relative clause, who explained the answers to the class.. 3.

(15) Table 1.1. Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy. SU>DO>IO>OPREP>GEN>OCOMP (>means is more accessible than) Explanation of symbols and example sentences: SU= subject The dog that bit the man… DO= direct object The man that the dog bit… IO= indirect object The girl that I wrote a letter to… OPREP= object of preposition The house that I talked to you about… GEN= genitive The woman whose son is John… OCOMP= object of comparative The woman that I am taller than…. Second, on the basis of this hierarchy, an implication is in order. That is, within the relative clauses, if a language can relativize a noun phrase in a given grammatical function in the hierarchy, then it can relativize a noun phrase in any grammatical function higher in the hierarchy, but not conversely.. This generalization thus. accounts for the fact that there are languages that can relativize subject and direct object, indirect object, object of preposition, and genitive, but can not relativize object of comparative. An example is Chinese (Keenan and Comrie, 1977). This generalization also accounts for the fact that there are no languages that can relativize indirect object but can not relativize direct object or subject. Third, the claim that the presence of one property implies the presence of another, but not conversely, imposes a markedness relationship within the NPAH. Hyltenstam (1987) provided a general notion of markedness: Expressed at a very general level, one can say that linguistic phenomena that are common in the world ’s languages, that seem easier for linguistic processing, and that are more “natural” than others, are unmarked as opposed to their marked variants.. 4.

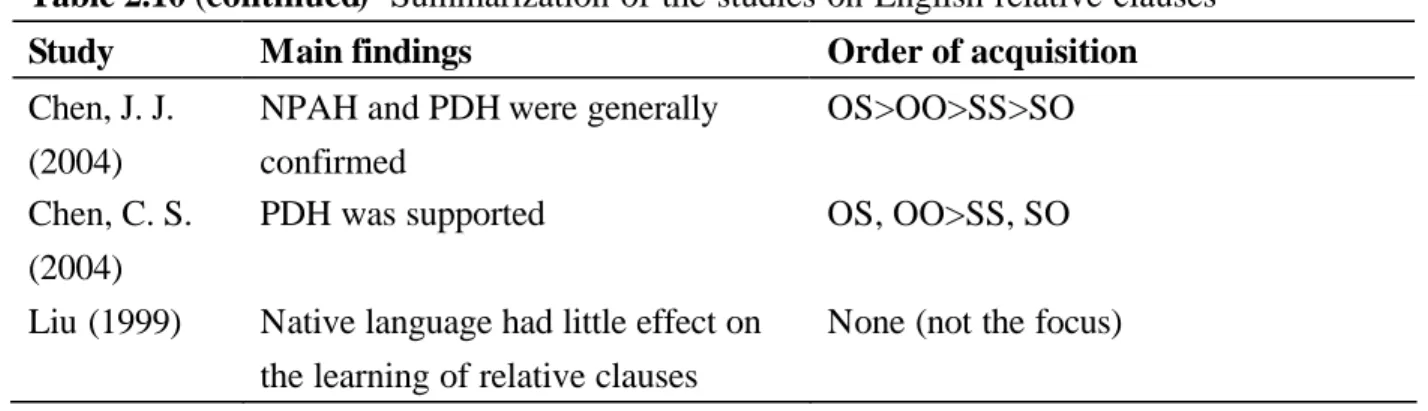

(16) Here we refer to another notion of markedness, the implicational markedness (Greenberg, 1966), in which the implied form is unmarked and the implying form is marked. In the case of NPAH, for example, a language which allows relativization of direct object is more marked than a language that allows relativization of subject only, where the direct object is the implying form and subject the implied form.. The. notion of the markedness relationship entails that learners tend to progress from less marked form to more marked from in the process of language acquisition (Braidi, 1999). There is another aspect that is of concern here: the resumptive pronoun, the retaining or copying of the pronoun in the relative clause. English normally does not allow resumptive pronoun, so if there are resumptive pronouns occurring, the ungrammatical sentences will be produced as shown in Table 1.2:. Table 1.2. Example sentences for pronoun retentions. RP Function. Example of ungrammatical sentences. SU DO IO OPREP GEN OCOMP. *The man who he spoke to me… *The woman who the car hit her… *The boy who I gave the book to him… *The girl that I talked to you about her… *The man whose his car broke down… *The girl that I am taller than her…. The resumptive pronoun facilitates comprehension of relative clause; thus it is more likely that the resuptive pronoun occurs in the lower positions in the NPAH, where without the pronoun retention the semantic meaning are difficult to retain (Keenan and Comrie, 1977). The potentiality of appearance of resumptive pronoun in the NPAH can be realized as the following.. Table 1.3 presents the relationship between. pronoun retention and markedness (Hyltenstam, 1987, 1990). It illustrates that the less marked the form is, the mo re likely that the resumptive pronoun is retained. 5.

(17) Resumptive Pronoun Hierarchy OCOMP> GEN> OPREP> IO> DO> SU (>means resumptive pronoun is more likely to occur in this position than) (adapted from Gass and Selinker, 2001). Table 1.3 Typological patterns for retention (+) or deletion (- ) of pronominal copies in relative clauses SU DO IO OBL GEN OCOMP + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +. most marked. least marked (from Hyltenstam, 1990). 1.2.2 Perceptual difficulty hypothesis (PDH). Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis is based on the notion that the limitation of the human temporary memory affects processing of sentences (Kuno, 1974). Specifically, it is argued that the center-embedded syntactic construction is perceptually more difficult than the right-or left-embedded construction because the center-embedded clause interrupts the flow of the sentence and taxes more on the short term memory. For example, the center-embedding in sentence (a), where the clause the cat chased is center-embedded in the clause the rat… ate, which in turn is center-embedded in the matrix sentence, makes the sentence extremely hard to comprehend. On the other hand, the right embedding construction in (b) is 6.

(18) comparatively easy to understand.. (a) Center embedding The cheese that the rat [[that the cat chased] ate] was rotten. (b) Right embedding The cat chases the rat [that ate the cheese [that was rotten]]. (Adapted from Kuno, 1974: 119). Although the order of difficulty was not intended by Kuno, the difficulty order of the various relative clauses, according to this hypothesis, would be as in Table 1.4.. Note. that the first letter stands for the grammatical function of the noun phrase in the matrix sentence, and the rest stand for the grammatical function of the noun phrase in the relative clause.. Therefore, the relative clause I know the girl who I am taller. than would be represented by OOCOMP.. Table 1.4. Order of difficulty predicted by PDH. OS, OO, OIO, OOPREP, OGEN, OOCOMP>SS, SO, SIO, SOPREP, SGEN, SOCOMP Note: (a) > means is easier than (b) Meaning of the first letter O= object S= subject (c) Meaning of the other letters S= subject O= direct object IO= indirect object OPREP= object of preposition GEN= genitive OCOMP= object of comparative. 7.

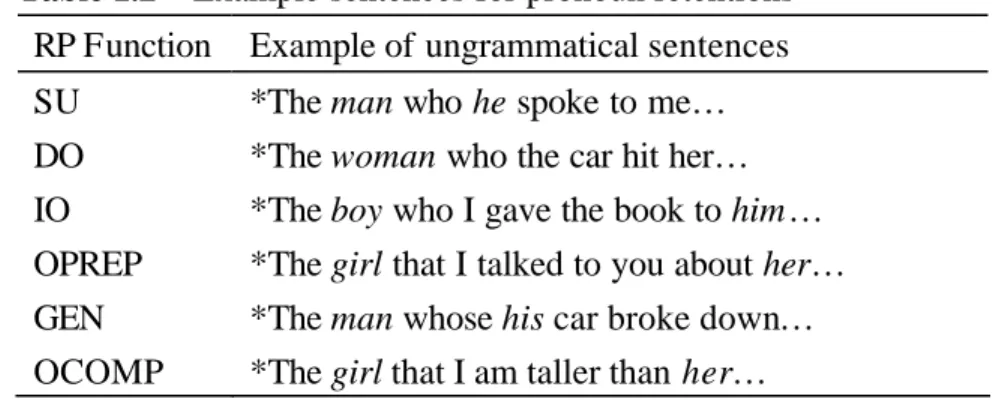

(19) 1.2.3 SO hierarchy hypothesis (SOHH). Motivated by NPAH, PDH and the notion of depth of embeddedness (O’Grady, 1987, 3003), Hamilton (1994) proposed the SO hierarchy on the basis of two main assumptions: (1) Center embedding of the relative clause sets up a processing discontinuity in the main clause; and (2) relativized subject sets up a single discontinuous S, whereas relativized object sets up two phrasal discontinuities within the relative clause (S and VP), as in the following.. Relativized subject The man who i [s ti saw us]. Relativized object. The man who i [s we [vp saw ti ]. (From Hamilton, 1994:135). Originally, this hierarchy is of three level, OS<OO/SS<SO (<means is implicated by) (Hamilton, 1994). By counting the depth of embedding of the gap (the counting method that was employed by O’Grady, 2003), we are here to extend and have the following six- level hierarchy, which embraces the various relative clauses.. 8.

(20) Table 1.5 Order. RC Type SS SO SIO SOPREP SGEN SOCOMP OS OO OIO OOPREP OGEN OOCOMP. Order of Difficulty by SO Hierarchy Hypothesis OS/OGEN>OO/SS/SGEN>SO/OIO/OOPREP>SIO/SOPREP> 1 2 3 4 OOCOMP>SOCOMP 5 6 Example sentences The man [who i [ IP ti needed a job]] helped the woman. The dog [thati [ IP the woman [vp owns ti ]]] bit the cat. The woman [who i [IP Bill [vp passed a note [ppto ti]]]]is a nurse. The candidate [who i [ IP I [vp vote [pp for t i]]]]didn’t win the election. The man [[whosei wallet]j [ IP tj was stolen]] called the police. The person [who i [IP John [vp is taller [cp than[IP ti [vp e ]]]]]]is Charles. Jerry likes the teacher who i [IP ti explained the answers the class]. A man bought the clock thati [ IP the woman [vp wanted ti]]. The teacher looked at the girl who i [IP I [vp explained the sentence [pp to ti]]]. I saw the woman who i [IP I [vp went to elementary school [pp with ti]]]. I know the man [whosei bicycle]j [IP tj is new]. I know the hotel whichi [IP Hilton [vp is cheaper [cp than[IP ti [vp e]]]]].. No. of discontinuity 2 3 4 4 2 6 1 2 3 3 1 5. Note: the first letter showing the grammatical function of the NP in the main clause and the second one showing the function of the NP in the relative clauses.. 9.

(21) 1.2.4 Summary of the three hypotheses. In comparison, these three hypotheses base on different theoretical grounds, and have disparate focus, which in turn give rise to dissimilar, yet complementary order of difficulty of relative clause (Izumi, 2003). They can be summarized as follows:. Table 1.6. Summary of the three hypotheses (Adapted from Chen, X. L., 2004).. Theoretical Hypotheses basis NPAH PDH. SOHH. Typological markedness Short-term memory capacity NPAH, PDH, and processing discontinuity. Order of difficulty (>means is easier than). Focus Relative clause Matrix clause. Matrix clause and relative clause. SU>DO>IO>OPREP>GEN>OCOMP OS, OO, OIO, OOPREP, OGEN, OOCOMP > SS, SO, SIO, SOPREP, SGEN, SOCOMP OS/OGEN > OO/SS/SGEN > SO/OIO/OOPREP>SIO/SOPREP > OOCOMP > SOCOMP. 1.3 The role of L1. The role of L1 in second acquisition has long been debated. In reaction to the Contrastive Analysis (Lado, 1957; Ellis, 1996a), some researchers downplayed the role of L1 in the process of L2 acquisition. For example, the frequently cited research by Dulay and Burt (1973) demonstrated that only 3% of learners’errors came from native language transfer and called the second language acquisition a process of Creative Construction (Ellis, 1996b), in which L2 learners are guided by innate universal principles instead of old habits from native language. Recent views hold. 10.

(22) that language transfer does not necessarily be seen as associated with behaviorism but, rather, is a cognitive activity (Gass, 1996; Gass and Selinker, 2001; Ellis, 1996a).. A. broader definition has been held that language transfer can be observed phenomenon such as avoidance, delayed rule restructuring, or different paths of acquisition (Sharwood Smith and Kellerman, 1986; Ellis, 2003; Gass and Selinker, 2001). Kleinmann (1977) provided a definition for avoidance strategies: “they are behaviors that the subjects use when they deliberately and consciously choose not to use the target form, possibly due to the difficulty or the partial mastery of the structure”.. A. case in point was the study by Schachter (1974). She examined production of English relative clauses by Persian, Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese and found that Chinese and Japanese learners made far fewer relative clauses than Persian and Arabic learners did and thus made fewer errors. She concluded that the mismatch of the branching direction between English and Chinese and Japanese (English being left-branching and Chinese and Japanese right-branching) caused the Chinese and Japanese learners to avoid using English relative clauses in composition. While Schachter didn’t look into the phenomena as to what learners were avoid ing, Gass (1980) specifically examined this issue. She investigated the combination task in her study and found that learners tended to avoid relativizing on the lower positions of the NPAH.. In particular, she pinpointed the four ways in which the learners avoid. relativization: (1) substitution of one lexical item for another; (2) switching the order of the two sentences so as to embed the sentence which was intended as the matrix; (3) changing the identical NP; and (4) changing the syntactic structure of the second sentence.. 11.

(23) 1.4 Purpose of the study. As mentioned before, despite that in the acquisition of English relative clauses, learners in Taiwan EFL context encounter many problems, studies that probe the issues in Taiwan context are relatively few, and the scope or coverage of the relative clause types is limited to SS, SO, OS, and OO (see the studies done by Chen, J. J., 2004; Chen, C. S., 2004; Chen, X. L., 2004).. Seeing this limitation, the current. study further investigates all the relative clause types that English manifests; namely SS, OO, SO, OS, SIO, OIO, SGEN, OGEN, OOPREP, SOPREP, SOCOMP, and OOCOMP (please refer to Table 1.5 for detailed illustration). What is more, even in non-Taiwan ESL studies, the OCOMP position is seldom included for inspection. Though OCOMP is a rarely used position in real life English, the inclusion of this position in the present study is important for us to explore the research question. Besides, while grammaticality judgment test is a common task type used in SLA research (Gass, 1979, 1980; Izumi, 2003; Ioup and Kruse, 1977), it seems that none of the studies done in Taiwan EFL context incorporates this measurement. In view of the above, in the present thesis, the research purpose is two fold. First, English relative clauses from Taiwan EFL college learners will be elicited using three kinds of tasks, sentence combination, Chinese-English translation, and grammaticality judgment. And the data will be analyzed to see the order of acquisition of different relative clause types.. Second, learners’avoidance behaviors. in the formation of English relative clauses will be explored. Particularly, it is intended to see how learners cope with the object of comparative (OCOMP), which is not readily relativizable in Chinese. To be specific, the positions that are relativizable in English (12 types) will be. 12.

(24) examined as well as the matrix positions as is concerned in PDH (concerning discontinuity in the main clause), and SOHH (concerning discontinuity in the main and relative clauses). Two sub-aspects are of special interest here. First, given that previous research indicated that genitive, indirect object, object of preposition fluctuated in the positions they took in the difficulty order, close attention will be paid to these positions.. Second, because most existing studies focused on OS, OO, SS,. and SO, more research is needed for other types of relative clauses. For example, GEN is a relatively frequently used relative clause in real life English, SGEN and OGEN are definitely worthy of investigation. There is a line of research investigating second language acquisition of relative clause by resorting to the head-direction parameter model of Universal Grammar (Flynn, 1989a, 1989b).. Flynn argues that the language universal of UG plays a. significant role in the learners’acquisition of relative clauses by resetting the head-direction parameter.. Although the typological universal (i.e., NAPH) and. Universal Grammar (Chomsky, 1965) are different in terms of the approaches the y are based upon, their goal of searching for the commonalities of the world languages is not different from one another (Ellis, 1996c; Ritchie and Bhatia, 2003).. In view of. this, the last part of the thesis will be devoted to discussing the implication of UG in the EFL acquisition of relative clauses.. 1.5 Significance of the study. The importance of English relative clauses for Taiwan EFL learners has been identified right from the beginning of this thesis: they are the forms that are highly frequently used in daily life of English native speakers; however they are very 13.

(25) complex in the structure and quite different from Chinese relative clauses. A review of the major ESL textbooks in Taiwan (Azar, 1999; Murphy, 1994; Riggenbach and Samuda, 2000; Thewlis, 2000) shows that, among other grammatical dimensions, a large part of these textbooks has been devoted to the delineation of and providing practices for relative clauses. The positions that are relativizable in English are included in these textbooks, except for OCOMP.. Unfortunately, the existing local. research focusing on relative clauses as topic does not looked into all the types but OS, SS, OS, and OO only, for the consideration of methodology or any other practical reasons.. However, in order to obtain a more complete picture of Taiwan EFL. learners acquiring relative clause, the previous accomplishment is too limited. Therefore, the present study is significant in including all the relativizable positions of English relative clauses and in contributing to a better understanding of foreign language acquisition. Apart from the incorporation in the thesis of the more complete types of relative clause, another contribution of the thesis is the thorough inspection of the learners’ behaviors of avoidance in the formation of relative clauses vis a vis the avoidance strategies claimed by Gass (1979, 1980). There is another contribution of this thesis, which adopts grammaticality judgment task in investigating learner’s intuitional data in contrast to the previous Taiwan based studies (Chen, J. J 2004 used learner’s composition; Chen, C. S., 2004 used a variety of tests including translation but not grammaticality judgment test; and Chen, X. L., 2004 used sentence combination test.. 14.

(26) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW. In this Chapter, a description of the linguistic properties of relative clauses in English and Chinese is given first, accompanied by a comparison and contrast of the two languages. Last is a review of the relevant previous studies in the acquisition of relative clauses.. 2.1 Englis h Relative Clauses. 2.1.1 Definition. The present study specifically concerns English restrictive relative clauses, which should not be confused with non-restrictive relative clauses. An example of English restrictive relative clause would be the man that I saw yesterday left this morning, in which the clause that I saw yesterday is specifically referred here as restrictive relative clause. It is so called because this clause serves to delimit or restrict the potential referents of the head noun the man. On the other hand, non-restrictive relative clauses would be who arrived yesterday as in the man, who had arrived yesterday, left this morning. In this kind of sentence, it is assumed by the speaker that the hearer can identify which man is being talked about, and the relative clause serves merely to give additional information to the hearer about an already identified entity, but not to identify that entity (Comrie, 1989:138). Li and Thompson (1981) provide a more concise definition, “a restrictive relative clause in any language is a clause that restricts the reference of the head noun. ” 15.

(27) 2.1.2 Head-initial. English restrictive relative clauses, as noun modifiers, are inside NPs to modify the head noun. In (1), it is obvious that the relative clause who have sixteen cats follows the head noun the woman in the right hand direction. English is in this respect head-initial.. (1). NP NP. S. the women who have sixteen cats. NP containing head noun. Relative clause (From Kaplan, 1989:303). 2.1.3 Relativization process. Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) make clear the process that is involved in deriving English relative clauses. English derives relative clauses by embedding a subordinate clause within another superordinate clause so that the embedded clause becomes a part of the superordinate clause. Before the embedding is complete, the redundant co-referential head NP in the embedded clause should be replaced by a relative pronoun. For example, embed the subordinate clause (b) within the superordinate clause (a), and replace they with who, as follows:. 16.

(28) (a) The fans had to wait in the line for three hours. (b) They were attending the rock concert. The fans [who were attending the rock concert] had to wait in line for three (NP[S]) hours. (from Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman, 1999). 2.1.4. Relativiza tion strategies and resupmtive pronoun. English allows relativization on various positions including subject, direct object, indirect object, object of preposition, genitive, and object of comparison. However, in the cases other than subject and genitive (which is in a subject NP), a gap (or trace) will occur after the fronting of the relative pronoun, as the examples in (2). The non-canonical word order makes the relative clause harder to comprehend; therefore languages (such as Chinese) tend to supply a resumptive pronoun in the gap, especially in the positions lower on the NPAH (Keenan and Comrie, 1977). In contrast to languages that employ resumptive pronoun strategy, English largely retains gap strategy. (2) a. Subject The woman who have sixteen cats left early. b. Direct object Max restored the car which Frank had owned [ ] in 1948. c. Indirect object This is the aunt who I sent those books to [ ] today. d. Object of preposition I learned the trick by which Huey deceived the voters [ ] when he ran for editor. e. Gentive This the kitten whose ear I tweaked. 17.

(29) f. Object of comparative You are the only person that I am shorter than [. ].. 2.1.5. Relative pronoun variables. English has several relative pronouns to choose from. The choice between who and which depends on the feature [± human] (human or non-human) of the NP. Who is used with a human antecedent and which with a non-human one. Whom can be optionally used for who when it is a relativized object (including direct object, indirect object, object of preposition, and object of comparative). And which and who can be alternatively replaced by that, as in (3).. (3) a. The man who(m) I recommended b. The man that I recommended c. *The man which I recomended d. The apartment which we rented e. The apartment that we rented f. *The apartment who(m) we rented. (adapted from Kaplan, 1989: 310). English sometimes omits the use of relative pronoun when the direct object, indirect object, object of preposition, and object of comparative are relativized, but not in the case of subject and genitive, as in (4).. (4) a. the apartment (which) we rented b. the guy (whom) you told me about c. the girl (whom) I sent a long-stemmed rose to d. the man (whom) John is taller than. 18.

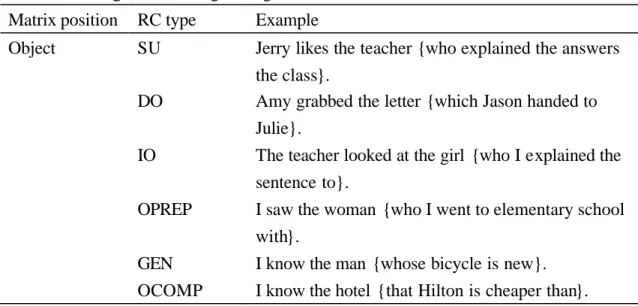

(30) 2.1.6 Center embedding and right embedding. English is a head- initial language, which makes the relative clauses that have the head NP function as subject in the matrix sentence center-embed within the matrix sentence, and the relative clauses that has the head NP function as object in the matrix sentence right-embed within the matrix sentence. Tables 2.1 and 2.2 provide the examples ({} shows the relative clause boundary).. Table 2.1. Center embedding in English relative clauses. Matrix position. RC type. Example. Subject. SU. The boy {who is standing at the gate} is my brother. The author {who he mentioned} is well known. The woman {who Bill passed a note to} is a nurse. The candidate {who I vote for} didn’t win the election. The man {whose wallet was stolen} called the police. The person {who John is taller than} is Charles.. DO IO OPREP GEN OCOMP. Table 2.2. Right embedding in English relative clauses. Matrix position. RC type. Example. Object. SU. Jerry likes the teacher {who explained the answers the class}. Amy grabbed the letter {which Jason handed to Julie}. The teacher looked at the girl {who I explained the sentence to}. I saw the woman {who I went to elementary school with}. I know the man {whose bicycle is new}. I know the hotel {that Hilton is cheaper than}.. DO IO OPREP GEN OCOMP. 19.

(31) 2.2 Chinese Relative Clauses. 2.2.1 Definition. Similar to English, Chinese makes distinction between restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses (Tang, 1979). As is clear in the examples (5), Chinese makes the distinction the way as English does: use of comma to distinguish between restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses. In this study, we focus on the Chinese restrictive relative clauses to compare with English ones.. (5) Restrictive relative clause xihuan nei— ben shu de nei— ge ren lai— le. like that— CL book Rel. Mar. that— CL person come— ASP “The man who likes the book has come.” (From Tsao, 1996) Non-restrictive relative clause nei— ge ren, xihuan nei— ben shu de, lai— le. that— CL person like that— CL book Rel. Mar. come— ASP “The man, who likes the book, has come.” (Adapted from Tang, 1979). 2.2.2 Head-final. Like English, Chinese restrictive relative clauses are inside NPs to modify the head NP. But unlike English, Chinese has the relative clause precede the head NP. The simplified diagram in (6) illustrates that Chinese is head- final.. 20.

(32) (6) Zhangsan mai de shu Zhangsan buy Rel.Mar. book “The book which Zhangsan bought” NP CP. NP. Zhangsan mai de shu. Relative clause. NP containing head noun. (Adapted from Chiu, 1996). 2.2.3 Relativization process and the relative marker. Chinese involves the relativization process that is similar but not identical to that in English. Chinese relative clauses do not contain relative pronouns, but use an invariant relative marker “de” to mark the relative clauses (Tang, 1979). In addition, the use of the relative marker is obligatory, not optional as English relative clauses are. After the co-referential NP in the subordinate clause (b) is deleted, a relative marker ‘de’ is attached to the end of the clause. The subordinate clause is placed ahead of the co-referential head NP, as opposed to English, in which the NP occurs at the end of the NP. (7) a. nei- ge ren lai- le. ‘The man has come.’ b. nei- ge ren Xihuan nei-ben shu. ‘The man likes the book.’ Xihuan nei-ben shu de nei- ge ren lai- le. Like that— CL book Rel.Mar that— CL person come ‘The man who likes the book has come.’ (Adapted from Tsao,1996) 21.

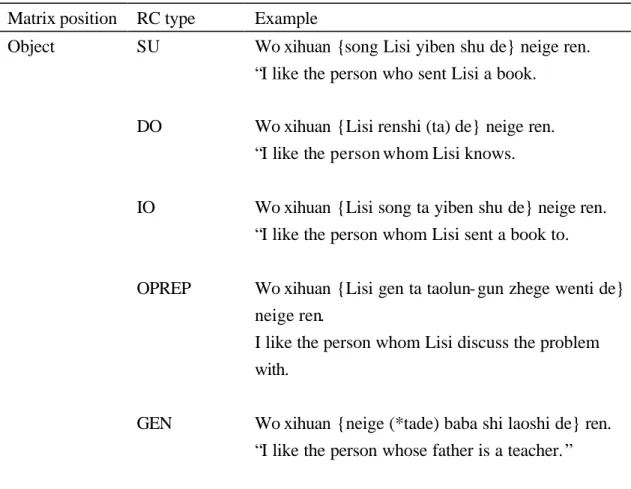

(33) 2.2.4 Relativization strategies and the resumptive pronoun. The positions that Chinese can relativize are subject, direct object, indirect object, object of preposition, and genitive, but not object of comparative, which English does (Keenan and Comrie, 1977). Chinese does not allow resumptive pronoun in subject and genitive relatives (which has subject NP) relativizations (Tsao, 1996). Optionally, it allows resumptive pronoun to occur in object relatization (Li and Thompson, 1981). The relativized positions that invariably require resumptive pronoun are indirect object and object of preposition. (8) a. Subject (*ta) song Lisi yiben shu de neige ren he send Lisi one book Rel.Mar that— CL person “the peron who sent Lisi a book” b. Direct object Lisi renshi (ta) de neige ren Lisi know him Rel.Mar. that— CL person “the person whom Lisi knows” c. Indirect object Lisi song ta yiben shu de neige ren Lisi send him one book REl.Mar. that— CL person “the person whom Lisi sent a book” d. Object of preposition Lisi gen (ta) taolun- gun zhege wenti de neige ren Lisi with him discuss-GUO this problem Rel.Mar that— CL person “the person whom Lisi discussed the problem with” e. Genitive neige (*tade) baba shi laoshi de ren that— CL his father is teacher Rel.Mar. person “the person whose father is a teacher” (Adapted from Chiu, 1996) 22.

(34) 2.2.5 Center embedding and left embedding. Chinese is a head-final language, so after process of relativization, Chinese will have the center-embedding occur in the sentences that have the head NP functioning as object , whereas those that the head NP functioning as subject result in left embedding relative clauses. This is just the opposite of English. Tables 2.3 and 2.4 have the illustration ({} represents the boundray of relative clause).. Table 2.3. Left embedding in Chinese relative clauses. Matrix position. RC type. Example. Subject. SU. {Song Lisi yiben shu de} neige ren lai— le. “The peron who sent Lisi a book came.”. DO. {Lisi renshi (ta) de} neige ren lai— le. “The person whom Lisi knows came.”. IO. {Lisi song ta yiben shu de} neige ren lai— le. “The person whom Lisi sent a book to came.”. OPREP. {Lisi gen ta taolun- gun zhege wenti de} neige ren lai— le. “The person whom Lisi discussed the problem with came.”. GEN. {neige (*tade) baba shi laoshi de} ren lai— le. “The person whose father is a teacher came.”. 23.

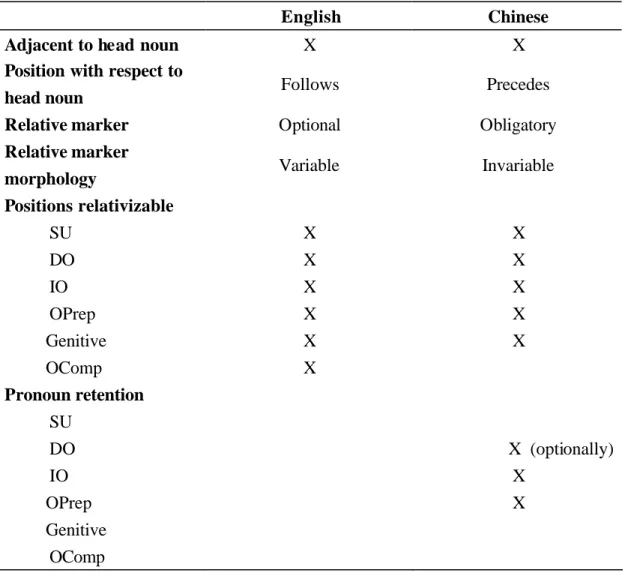

(35) Table 2.4. Center embedding in Chinese relative clauses. Matrix position. RC type. Example. Object. SU. Wo xihuan {song Lisi yiben shu de} neige ren. “I like the person who sent Lisi a book.. DO. Wo xihuan {Lisi renshi (ta) de} neige ren. “I like the person whom Lisi knows.. IO. Wo xihuan {Lisi song ta yiben shu de} neige ren. “I like the person whom Lisi sent a book to.. OPREP. Wo xihuan {Lisi gen ta taolun- gun zhege wenti de} neige ren. I like the person whom Lisi discuss the problem with.. GEN. Wo xihuan {neige (*tade) baba shi laoshi de} ren. “I like the person whose father is a teacher. ”. 2.3 Similarities and Differences between English and Chinese relative clauses. To sum up, one thing that English and Chinese relative clauses have in common is that they are both adjacent to the head NP. However, for the most parts, they are quite different. First, while English relative clauses are head- initial, Chinese ones are head-final. Second, use of English relative pronouns is optional, but use of Chinese relative marker is mandatory. Third, English has a number of relative pronoun choices whereas Chinese invariably makes use of “De” as the relative marker. The positions English can relativize include subject, direct object, indirect object, object of preposition, genitive, and object of comparative. On the other hand, Chinese can relativize the positions that English does, but without object of. 24.

(36) comparative.. The similarities and differences between English and Chinese relative. clauses are summarized in table 2.5.. Table 2.5 Relative clause patterns in English and Chinese, adapted from Gass (1980). Adjacent to head noun Position with respect to head noun Relative marker Relative marker morphology Positions relativizable SU DO IO OPrep Genitive OComp Pronoun retention SU DO IO OPrep Genitive OComp. English. Chinese. X. X. Follows. Precedes. Optional. Obligatory. Variable. Invariable. X X X X X X. X X X X X. X (optionally) X X. 25.

(37) Table 2.5 (continued) Relative clause patterns in English and Chinese, adapted from Gass (1980) English Center embedding S SU DO IO OPrep Genitive OComp O. Chinese. X X X X X X. SU DO IO OPrep Genitive OComp. X X X X X. 2.4 Previous studies on the acquisition of relative clauses. Quite a number of research has been devoted to seeing whether there is a universal order of acquisition of relative clauses. The issue that has been frequently explored is whether the universal markedness relationship as predicted by NPAH is adhered to in second language learners’interlanguage (Gass, 1979, 1980; Pavesi, 1986; Hyltenstam, 1987, 1990). At the same time, transfer issue is taken into account in the investigation of linguistic universals as native language is deemed a significant influencing factor (Odlin, 1989). On the other hand, psycholinguistic factors are also considered in determining the order of acquisition (Ioup and Kruse, 1977; Schumann, 1980). In this section, literature regarding the acquisition of relative clauses will be subdivided into two subsections: the first subsection concerns the acquisition of 26.

(38) relative clauses in English and non-Chinese languages and the other concerns the acquisition of Chinese relative clauses.. 2.4.1 Acquisition of relative clauses in English and in non-Chinese languages. In the attempt to better determine the relationship between transfer and universal factors in the second language acquisition, Gass (1979) investigated the acquisition of English relative clauses by adult second language learners, who had a variety of linguistic backgrounds. The nine native languages of the learners were Arabic, Chinese, French, Italian, Korean, Persian, Portuguese, Japanese, and Thai. Data from 17 high- intermediate and advanced learners were elicited with two elicitation tasks: grammaticality judgment and sentence combination. 12 types of relative clauses were involved. Note that the indirect object and object of preposition were then collapsed as under one category. Gass claims that language transfer is evident in the acceptance or rejection of the resumptive pronouns in the English relative clauses. The groups whose native languages have resumptive pronouns are more likely to accept ungrammatical English sentences that have resumptive pronouns. The tendency is evident in the three highest positions on the NPAH, but not in the lowest two positions: genitive and object of comparative. The author argues that we cannot yet determine whether the acceptance of resumptive pronoun in the genitive and object of comparative is due to the influence of native languages or language universal for lack of conclusive evidence. In addition, universal orders as predicted by NPAH were found to be accorded to, the easiest position to relativize being subject and the most difficult position object to comparative. However, genitive was the exception.. Gass provided two possible explanations for this. First, genitive is 27.

(39) uniquely coded for case/grammatical relation in English, and there are no variants such as that or which. Second, it is possible that learners treat whose son in (9) as a unit, the subject of the verb came. In doing so, learners might perceive genitive like subject, the highest position on the NPAH, thus making genitive easier to relativize.. (9) The man whose son just came home. In conclusion, it was claimed that language universals played the leading role since they were dominant both in assigning relative orders of difficulty and in determining where language transfer occurs.. Figure 2.1 Percentage of sentences correct on combining task (all group)(from Gass, 1979). In 1980, Gass conducted a similar study. However, as the 1979 study was based only on the accuracy rate with which learners acquired relative clauses, the 1980 one looked also at the frequency of the relative clauses learners produced. Gass compared the number of the relative clauses used by given subjects with the same subjects’ performance on the combining task. It was hypothesized that if the number of the relative clauses was related to difficulty, then it would positively. 28.

(40) correlate with actual difficulty on the combining task. The correlation was however not significant. To further investigate what learners were actually avoiding in producing relative clauses, Gass examined larner ’s relative clauses in combining task and found four types of avoidance strategies learners used as in (10) (From Gass, 1980):. (10) 1.. Substitution of one lexical item for another. Example: The woman danced. The man is fatter than the woman. →The woman that is thinner than the man danced. (Persain and Chinese). 2.. Switching the order of the two sentences so as to embed the sentence which was intended as the matrix. Example: He saw the cat. The dog jumped on the cat. →The dog jumped on the cat that he saw. (Arabic). 3.. Changing the identical NP. Example: He saw the woman. The man is older than the woman. →He saw the man who is older than the woman. (French). 4.. Changing the syntactic structure of the second sentence. Example: He saw the woman. The man kissed the woman. →He saw the woman who was kissed by the man. (Arabic). There are other studies that have similar results to Gass’s concerning the grammatical judgment of resumptive pronoun. Hyltenstam (1987, 1990) found that his subjects who learned Swedish (which, like English, does not manifest resumptive pronoun) as second language tended to use resumptive pronoun in their interlanguage, no matter whether their native languages have resupmtive pronoun or not. For example, although resumptive pronoun does not occur in Finnish and Spanish, learners in these groups used resumptive pronoun in oral elicitation task. The pattern 29.

(41) is also dependant on the first language structure, as there are more pronoun retentions in the Swedish of those learners whose L1 uses this strategy more frequently. In particular, the universal hierarchy as predicted by NPAH was generally adhered to, except the genitive and object of comparative and indirect object and object of preposition. It was argued that the order between OCOMP and GEN and that between IO and OBL should be inverted to reflect a psychologically real acquisition order rather than the typological one. The acquisition order obtained by Hyltenstam was further supported by Pavesi (1986). Pavesi (1986) set out to investigate the possible influence learning context could have in the acquisition of English relative clauses. For the learning context, Pavesi means the different type of discourses: formal and informal, which learners were mostly exposed to. Two groups of speakers of Italian were involved: 48 EFL Italian high school students, who received formal English input through instruction; and 38 Italian workers in Edinburgh, who had only informal English input from daily contact with English speakers. It was presumed that the acquisition order as predicted by NPAH would be yielded by both groups and that the formal groups would exhibit more marked structures than the informal groups. The elicitation technique used was oral task with pictorial cues as in the study by Hyltenstam, in which subjects were expected to orally produce the intended relative clauses when an interviewer asked questions with illustrated pictures. For example, when the interviewer asked who is No.6? the expected answer was No. 6 is the man who is running. A “+” would be assigned when a correct relative clause was produced 80 percent of the time, otherwise a “- ” would be assigned. Two major conclusions were reached. First, the results generally came out as assumed: both formal and informal groups conformed to the implicational order on the NPAH. Second, more formal learners mastered target- like relativization. 30. However, the pattern for.

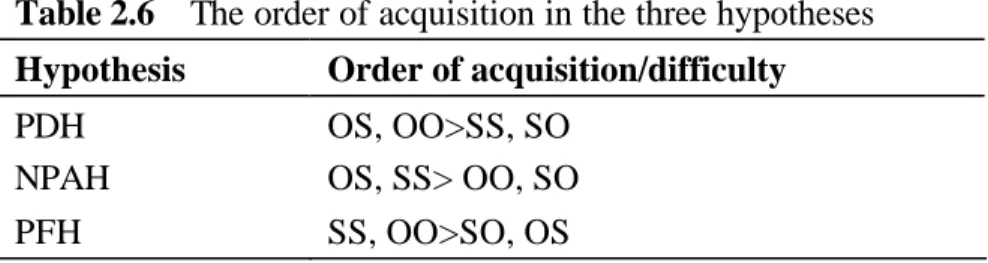

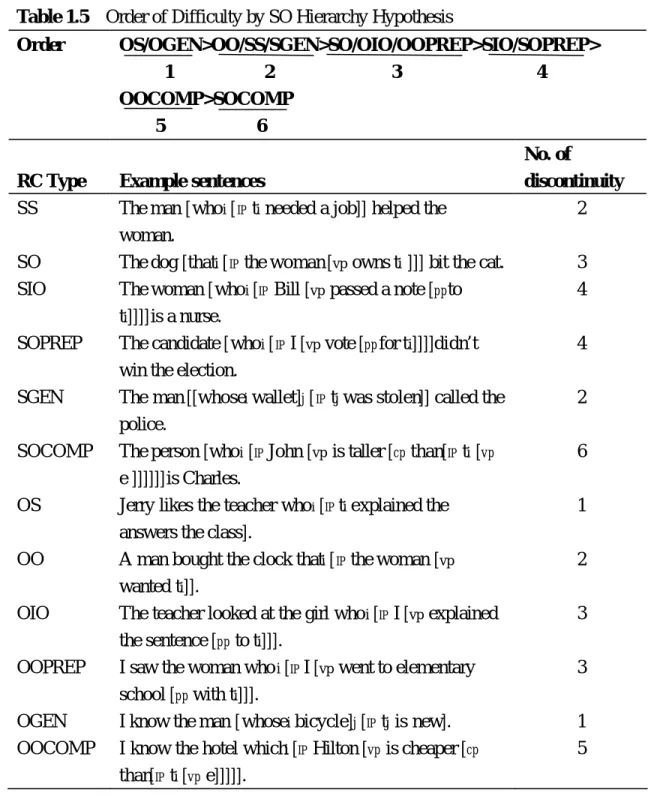

(42) indirect object and object of preposition and also for genitive and object and comparative was not always as expected as on the NPAH. That is, the learners tended to invert the order of indirect object and object of preposition, and genitive and object of comparative. Tarallo and Myhill (1983) investigated acquisition of relative clauses in Chinese, Portuguese, German, Japanese, and Persian by native speakers of English who were asked to judge the grammaticality of relative clauses. The findings were three- fold. First, the use of resumptive pronouns in interlanguage was a universal phenomenon. This generalization was made because while English is a language that does not allow resumptive pronoun, it was found that learners’ accepting resumptive pronouns in L2 languages was a common practice. Second, learners generally followed the order in the NPAH, except for object of preposition and indirect object. The order of difficulty was SU/DO>OPREP>IO>GEN (> means is more easier than). Third, there was evidence for transfer effect. For example, German and Chinese do not have preposition in indirect object relativization, but English does. Learners of German and Chinese rejected the relativization of indirect object more often than did that of subject and direct object, showing that learners of these two languages were transferring the feature of English to German and Chinese. Ioup and Kruse (1977) tasted three hypotheses, PDH (Kuno, 1974), NPAH and parallel function hypothesis (PFH) (Sheldon, 1973) to see whether the native language interference or language universals best describe second language acquisition of English relative clauses. Learners of divergent linguistic backgrounds were involved: Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Persian, and Spanish. They were to judge grammaticality of 36 written sentences which were comprised of OS, OO, SS, and SO types of relative clauses. Recall that PDH predicts the order of difficulty of OS, OO>SS, SO, (> means is easier than) based on the notion that center embedding is perceptually 31.

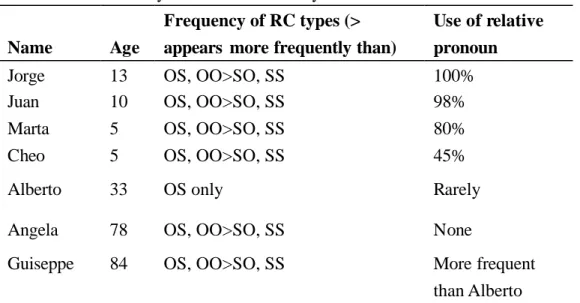

(43) more difficult than right embedding; and that NPAH predicts the order of acquisition of OS, SS> OO, SO, on the basis that relative clauses on subjects will be easier than those formed on objects. The PFH Sheldon proposed maintains that relative clauses which are most easily to acquire are those in which the relative pronoun has the same function as the head noun, thus having the difficulty order of SS, OO>SO, OS. In answering the research question, Ioup and Kruse analyzed the variables of language group, sentence type, and the combination of the two, and found that contrary to the CA hypothesis, sentence type rather than native language background is the most reliable predictor of error. Besides, the data showed that Kuno’s hypothesis: PDH received the most support, establishing that center-embedding as the parameter of perceptual complexity is the most significant variable in relative clause processing.. Table 2.6 The order of acquisition in the three hypotheses Hypothesis. Order of acquisition/difficulty. PDH NPAH PFH. OS, OO>SS, SO OS, SS> OO, SO SS, OO>SO, OS. Schumann (1980) analyzed relative clauses in the production data of international subjects who lived in the U.S. to determine the frequency with which the various relative clause types were used. An analysis of the frequency with which relative pronouns are present or absent in both obligatory and optional contexts was also made. One subject named Jorge was a 13 year-old Colombian boy who attended an all English school where he had only very minimal instruction in English as a second language. He mostly produced OS and OO types (with the OS predominating) and relatively few SO and SS. As for relative pronoun, Jorge always supplied a relative pronoun where required and supplied it over 60 percent of the time. 32.

(44) where it was optional. 10- year-old Juan was Jorge ’s younger brother. He had the same kind of exposure to English as Jorge did. The relative clauses he produced were mostly OS and OO with SO and SS occurring less frequently.. He also supplied. a relative pronoun where required and did so almost 80 percent of the time where it was optional. Marta was a five- year-old girl who attended all- English nursery school in Cambridge. OS and OO were more frequent in her spoken data than were SO and SS, and relative pronouns occurred 80 percent of the time in obligatory contexts but only 21 percent in optional contexts. Cheo, the five-year-old boy who attended an all-English kindergarten in Boston, produced more OS and OO types than SO and SS ones. Relative pronouns were supplied by him 45 percent of the time where required and 12 percent where optional. Alberto was a 33-year-old man who worked in a frame manufacturing factory. While receiving little instruction in English when he was in Costa Rita, he essentially used OS relative clauses and virtually supplied no relative pronouns at all. Angela was 78-year-old woman who had lived in the U.S. since she was 37, and received no English instruction.. She. used few relative clauses, and when she did, OO and OS were more frequent than SO and SS. Like Alberto, She did not use relative pronouns. Guiseppe was Angela’s 84-year-old husband. His exposure to English was greater than his wife due to work. The relative clauses he used were more OS and OO types than SO and OO ones. He used more relative pronouns than his wife did, especially in obligatory contexts. In conclusion, equaling low frequency with difficulty and high frequency with ease, it was claimed that OO and OS sentence types were preferred to SS and SO ones, in support of Kuno’s (1974) PDH that center-embedding is the most crucial factor in processing relative clauses. This finding also confirms the research results in Ioup and Kruse’s study (1977).. Table 2.7 presents the. 33.

(45) Table 2.7 Summary of Schumann’s study Name. Age. Frequency of RC types (> appears more frequently than). Use of relative pronoun. Jorge Juan Marta Cheo. 13 10 5 5. OS, OO>SO, SS OS, OO>SO, SS OS, OO>SO, SS OS, OO>SO, SS. 100% 98% 80% 45%. Alberto. 33. OS only. Rarely. Angela. 78. OS, OO>SO, SS. None. Guiseppe. 84. OS, OO>SO, SS. More frequent than Alberto. Flanigan (1995) tested the comprehension and production of restrictive relative clauses (SS, SO, OO, and SO). The comprehension task involved asking subjects to identify the referent in the relative clauses and the production task is sentence combination.. The subjects were young elementary students who were speakers of. nine languages: Chinese, Indo/Malay, Korean, Icelandic, Arabic, Spanish, Sinhalese, and Hebrew. The data revealed that the learner proficiency and task type significantly affect the performance, with high proficiency performing better than low proficiency and with performance on the production section worse than on the comprehension section. The order of accuracy obtained for the four relative clause types were OS>OO>SS>SO. The most important constraint on relative clause interpretation and production was claimed to be center-embedding that interrupt the flow of the matrix sentence interpretation. Besides, an analysis of the use of resumptive pronoun did not show evidence of transfer for lack of correlation. Izumi (2003) tested three hypotheses of the acquisition of relative clauses: NPAH, PDH, and SOHH. The subjects were 61 ESL learners who spoke different native languages: Chinese, Arabic, French, Japanese, Kazah, Korean, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish, Thai, and Turkish. Both productive and receptive tasks were 34.

(46) used as measuring instrume nt since it was believed that tasks in different modalities may present different degrees and/or types of difficulty in learners’ language processing.. The author used sentence combination task to examine subjects’. productive ability, and interpretation task and grammaticality task to measure subjects’ comprehension of relative clauses. The relative clause types that were focused were SO, SS, OO, OS, SOPREP and OOPREP. Note that the SDO and SIO were collapsed into SO, and ODO and OIO into OO. This clearly is a weakness that was also indicated by the author, because the exclusion of SG, OG, SOCOMP, and OCOMP makes the study not so comprehensive. Data were analyzed separately under the three measurements, which yield the order of difficulty as in table 2.8. It was found that the overall order of difficulty can be predicted by the matrix positioning, with the matrix object position being easier than the matrix subject position, and within each matrix position, the difficulty order can be predicted, at least partly, by the RC types as specified in the AH. According to these results, the author came to the conclusion that NPAH and PDH, being based on different rationales, can be seen to be complimentary to each other since NPAH is associated to the effect of canonicity within the RC and PDH is related to the notion of processing interruption in the matrix sentence. As to SOHH, the research results did not lend a full support to it, which the author explained by stating that “a simple statistical counting of the number of discontinuities in a sentence, in any case, may be too coarse to predict acquisition difficulty.”. 35.

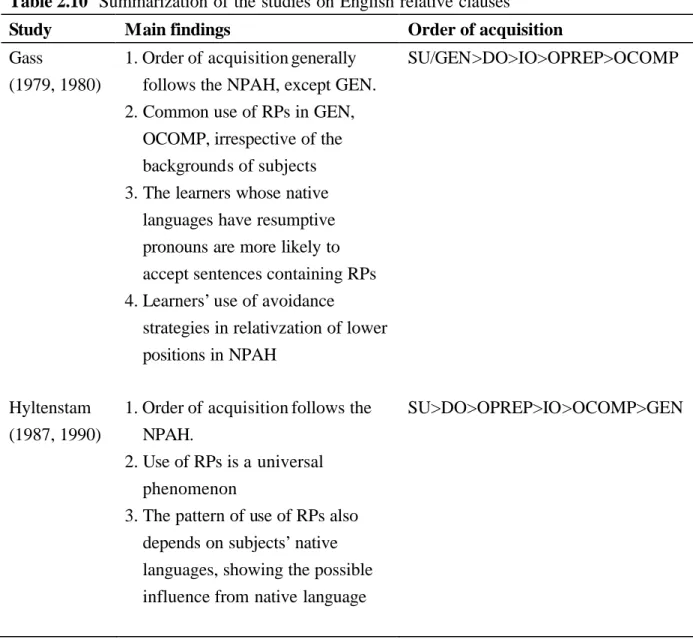

(47) Table 2.8 Order of difficulty of English relative clauses in Izumi’s three tasks task. Order of difficulty in Izumi ’s study. Sentence combination test. OS>OO>OOPREP>SS>SO>SOPREP. Interpretation test. OS>OOPREP>OO>SS>SOPREP>SO. Grammaticality judgment. OS>SS>OOPREP>OO>SO>SOPREP. Note: the order of difficulty by SO Hierarchy is OS>OO/SS> OOPREP/SO>SOPREP. There is some research done in the EFL Taiwan context. Chen, J. J. (2004) investigated production of English relative clauses in composition by 102 university students who majored in English. The results demonstrated the order of acquisition of OS>OO>SS>SO.. Chen, J. J. claimed that this order generally followed the. predictions made by NPAH and PDH. Chen, C. S. (2004) conducted an analysis of errors of English relative clauses produced by senior high school students in Taiwan. Data in his study also showed that Kuno ’s PDH was supported. Liu (1999) focused on the issue as to whether years of learning and native language had any effect on learners’ acquisition of English relative clauses. The author claimed that whereas years of learning English played an important role, L1 had little effect.. 2.4.2 Summary. As is evident in the summarization table for the studies on English relative clauses (Table 2.10), there are some discrepancies about the order across the studies. They exist mostly in the order among indirect object and object of preposition, and genitive. To reiterate, Pavesi (1986) found that there was a reverse relationship between indirect object and object of preposition. Besides, instead of object of comparison being the most difficult one to relativize, genitive was the most difficult 36.

(48) one in Pavesi’s order. Hyltenstam (1990) had the exact same outcome as in Pavesi’s. Tarallo and Myhill (1983), who did not investigate object of comparison, had identical order to Pavesi’s and Hyltenstam’s. On the other hand, Gass’s (1980) research showed that genitive was the easy one to relativize, just next to subject. Interestingly, there were some researchers who argued against the theoretical validity of Accessibility Hierarchy in terms of genitive. Jones (1991, cited in Ellis, 2003) argues that it is a mistake to include genitive in the hierarchy because it has a separate and complete hierarchy of its own (Table 2.9). Tsao (1990: 35) indicates that Accessibility Hierarchy is incorrect in its prediction that languages will exhibit a greater tendency to use pronoun retaining strategies as we descend the Accessibility Hierarchy, since Chinese does not have pronoun retention in the relativization of genitive (subject function). And Chinese relativized genitive (subject function) actually act like relativized subject. In view of the above, which was mentioned in Chapter one, the order of genitive, indirect object, and object of preposition will be closely observed in this study. Apart from the discrepancy issue, it is apparent in the literature that most of the research focused on the four types of relative clauses: OO, OS, SS, SO. Though, Izumi (2003) also looked at SIO, OIO, OPREP, and SOPREP, they were collapsed into SOPREP (including SIO and SOPREP) and OPREP (OIO and OPREP). Therefore, further research is needed for other types of relative clauses.. 37.

(49) Table 2.9 The Accessibility Hierarchy for –Genitive and +Genitive (Adapted from Jones, 1991, in Ellis, 2003) Function. –Genitive. +Genitive. SU DO IO. The man who came… The man Whom I saw … The man whom I gave the book to… The man whom I looked at. The man whose wife came… The man whose wife I saw… The man whose wife I gave the book to… The man whose wife I looked at… The man whose wife I am bigger than…. OBL OCOMP. The man whom I am bigger than…. Table 2.10 Summarization of the studies on English relative clauses Study. Main findings. Order of acquisition. Gass (1979, 1980). 1. Order of acquisition generally follows the NPAH, except GEN. 2. Common use of RPs in GEN, OCOMP, irrespective of the backgrounds of subjects 3. The learners whose native languages have resumptive pronouns are more likely to accept sentences containing RPs 4. Learners’use of avoidance strategies in relativzation of lower positions in NPAH. SU/GEN>DO>IO>OPREP>OCOMP. Hyltenstam (1987, 1990). 1. Order of acquisition follows the NPAH. 2. Use of RPs is a universal phenomenon 3. The pattern of use of RPs also depends on subjects’ native languages, showing the possible influence from native language. SU>DO>OPREP>IO>OCOMP>GEN. 38.

數據

相關文件

Table 12 : Sampling errors of per-capita shopping spending of interviewed visitors by place of residence and type of expense. Table 13 : Interviewed visitors’ comments on services

Table 12 : Sampling errors of per-capita shopping spending of interviewed visitors, by place of residence and type of expense. Table 13 : Interviewed visitors’ comments on

Table 12 : Sampling errors of per-capita shopping spending of interviewed visitors, by place of residence and type of expense. Table 13 : Interviewed visitors’ comments on

第六节.

二、多元函数的概念 三、多元函数的极限

refined generic skills, values education, information literacy, Language across the Curriculum (

From these results, we study fixed point problems for nonlinear mappings, contractive type mappings, Caritsti type mappings, graph contractive type mappings with the Bregman distance

To have a good mathematical theory of D-string world-sheet instantons, we want our moduli stack of stable morphisms from Azumaya nodal curves with a fundamental module to Y to