Factors influencing the mammography utilization among Taiwanese women with intellectual disabilities , a nationwide population-based study

Hsien-Tang Lai a,b,c, Pei-Tseng Kung d,1, Wen-Chen Tsai c,1* a. Dachien General Hospital, Miao Li, Taiwan, R.O.C.

b. Department of Business Management, National United University, Miao Li, Taiwan, R.O.C.

c. Department of Health Services Administration, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C.

d. Department of Healthcare Administration, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C.

1 The authors contributed equally to this work * Corresponding author: Professor Wen-Chen Tsai Tel: +886-422073070 Fax: +886-422028895 e-mail:wtsai@mail.cmu.edu.tw

Abstract

Women with intellectual disabilities (ID) have cognitive impairment and communication difficulties; for both caregivers and clinical personnel, discovering the early symptoms of breast cancer among women with ID is challenging. The mammography utilization rate of women with ID was significantly lower than that of women in the general population. This study employed a 2008 database of people with disabilities in Taiwan as a research target and analyzed the mammography utilization rate of women with ID aged 50–69 years. In addition, relevant factors influencing mammography utilization among women with ID were also investigated. A total of 4,370 participants were recruited and the majority were illiterate or had elementary-level educations (82.27%). The majority of the participants had ID that was more severe than mild (83.80%). The mammography utilization rate of women with ID was 4.32%, which was significantly lower than that of women in the general population (12%). The mammography utilization rate among women with ID who were married, had higher education levels, and had been diagnosed with cancer, diabetes, or mild ID was significantly higher. However, the mammography utilization rate among women with ID, who had elementary-level educations or were illiterate, was only 4.03%. The utilization rate among women with profound ID was only 2.65%. Women with ID who had undergone pap smears or had utilized adult

preventive health services demonstrated a significantly higher mammography utilization rate.This study identified that education level, a diagnosis of diabetes, and the application of pap smears or adult preventive health services were primary factors that influenced the mammography utilization rate among women with ID. This study also observed that in Taiwan, the mammography utilization rate of women with ID was lower than that of pap smears and adult preventive health services, and was only half of that of people with disabilities. An unequal situation existed in regard to the acceptance of breast cancer screening among women with ID, and a different form of strategic planning must be adopted in public health policy. Because ID differs from other disabilities and most women with ID are illiterate, tailored courses are required to train primary caregivers and clinical personnel in providing knowledge and services. The objectives are to diagnose breast cancer at an early stage to decrease the risk of mortality and ensure their rights to health.

Keywords: mammography; intellectual disabilities; heath prevention;cancer screening

Factors influencing the mammography utilization among Taiwanese women with intellectual disabilities , a nationwide population-based study

1. Introduction

In 2000, approximately 1.8% of women died of breast cancer worldwide (Sullivan et al., 2003). Advancements in medicine have prolonged the life expectancies of women with ID; thus, the risk of breast cancer has also increased (Davies & Duff, 2001; Hanna, Taggart, & Cousins, 2011; Taggart, Truesdale-Kennedy, & McIlfatrick,

2011; Sullivan et al., 2003). Approximately 50% of women with ID live up to 70 years; thus, the participants, aged 50 to 69 years, were in an age group subject to the highest risks of breast cancer (Sullivan et al., 2003; Taggart, Truesdale-Kennedy, &

McIlfatrick, 2011). Factors that have contributed to the onset of breast cancer among

women with ID include lifestyle sedentarism (McGuire et al., 2007), low levels of exercise (Temple & Walkley, 2003), nulliparity, which increased the risk by four times (Davies & Duff, 2001; Judkins & Akins, 2001; Sullivan et al., 2003), and sexual inactivity and loss of menstruation with low estrogen levels and a shorter menstrual cycle (Patja et al., 2001). In addition, long-term usage of hormone-based contraception (McPherson, Steel, & Dixon, 2000; Sullivan et al., 2003) and the consumption of a high-fat diet and obesity are also contributing factors (Ewing et al., 2004; Willett, 2001; Sullivan et al., 2003). Breast cancer incidence and mortality can be reduced by performing effective breast cancer screening (Blanks et al., 2000; Sullivan et al., 2003). Because of cognitive impairment and communication difficulties among women with ID, discovering breast cancer symptoms early is a challenge for both caregivers and clinical personnel. Furthermore, women with ID must rely on caregivers’ assistance during breast cancer screening (Hanna,Taggart, &

Cousins, 2011; Taggart, Truesdale-Kennedy, & McIlfatrick, 2011). Women with ID

do not understand why they need mammography and how it is performed; thus, they experience more fears and anxieties than women in the general population (Sullivan et

al., 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2011). In Taiwan, the population with ID is approximately 100,363, or 0.46% of the total population, and 43% are women (Ministry of the Interior, 2012). Breast cancer is the cancer with the highest incidence among Taiwanese women (2006 standardized incidence rate = 50 per 100,000 person-years). Furthermore, the age of breast cancer incidence was earlier than in the US and Europe, ranging from approximately 45–64 years, and breast cancer is the fourth most common fatal cancer among women (2006 standardized mortality rate = 11 per 100,000 person-years) (Health Promotion Administration, 2012). Beginning in 2004, the Taiwan Health Promotion Administration has been providing free mammography screening once every two years for women aged 50–69 years. In 2007 and 2008, the ratio of women aged 50–69 years that had received mammography screening within the preceding two years was 12% (Health Promotion Administration, 2012).

An Australian study reported that women with ID had a lower incidence of breast cancer (64.0 per 100,000 person-years) compared with women in the general population (146.7 per 100,000 person-years). This may have resulted from the shorter life expectancy or lower mammography utilization rate among women with ID. In the Australia, the utilization rate of women with ID was 34.7%, which was lower than that of women in the general population (54.6%) (Sullivan et al., 2003). A study conducted in Ontario, Canada, indicated the number of women with ID that did not undergo mammography screening was 1.5 times that of women in the general population (Cobigo et al., 2013). In the US the utilization rate of women with ID was 53%, compared with 85% of general population (Wilkinson et al.,2011;Parish et al., 2013).The Disability Rights Commission (2004) reported that in the UK, people with learning disabilities were four times more likely to die of preventable causes than the general population, and that this was an extremely challenging problem of unequal

human rights (Hanna, Taggart, & Cousins, 2011). Davis also found that 30% of women with ID had never been invited to receive mammography. This study analyzed the mammography utilization rate of women with ID and relevant factors. The objective of this study was to draw the attention of public health policymakers, increase the mammography utilization rate among women with ID, and decrease the incidence and mortality rate of breast cancer.

2. Methods 2.1. Data sources and processing

This study analyzed a 2008 database of people with disabilities who registered with the Ministry of the Interior in Taiwan; by also referencing the National Health Insurance Research Database of the National Health Insurance Administration, we analyzed the mammography utilization rate among women with ID aged 50–69 years. The Andersen model was employed to analyze the mammography utilization of women with ID and the independent variables were as follows: (a) the predisposing component included demographics (i.e., gender, age, marital status, and aboriginal status), social status (i.e., education) and health beliefs (i.e., utilization of pap smears and adult preventive health services); (b) the enabling component included personal and family resources (i.e., monthly salary) and community resources (i.e.,

urbanization,the first level had the highest urbanization and the eighth level had the lowest urbanization); and (c) the need component included diagnoses of catastrophic illness, cancer, and diabetes, and ID severity, which was divided into four levels—

mild was defined as having an intelligence quotient of at 55-69, moderate (40-54), severe (25-39), and profound (<24).The dependent variable was the utilization of mammography.

2.2 Statistical analysis

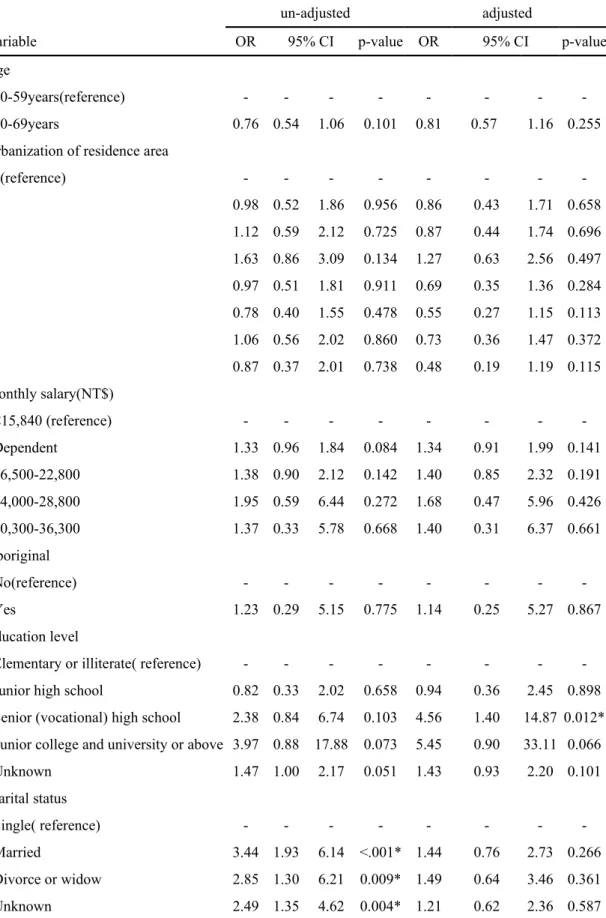

SAS version 9.1 was used to perform data analysis. Univariate analysis was employed to calculate descriptive statistics and determine the numbers of people and percentage. Subsequently, the times and percentages of mammography utilization among women with ID were analyzed; the results are shown in Table 1. In bivariate analysis, the t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Chi-squaretest were used to check for statistical significance. Variables that yielded p < .05 in the Chi-square test were submitted to multivariate analysis. Logistic regression was used to analyze the factors that influenced mammography utilization among women with ID; the level of

significance was p < .05. Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted values of the original data (the effects of individual variables were examined after controlling for other variables). This study has been approved by the research ethics committee in China Medical University and Hospital (IRB No. CMU-REC-101-012).

3. Results 3.1 Demographics of women with ID

In total, 4,370 women with ID were recruited; the majority were 50–59 years (69.20 %), married (47.19%), and were illiterate or had elementary-level educations (82.27%). Regarding health beliefs, 28.54% and 21.28% of the women with ID had underwent pap smears or had utilized adult preventive health services, respectively. Based on the salary data, the majority had monthly salaries in the range of the minimum wage of NT$15,840(50.09%)or were dependents (34.37%). Regarding urbanization of residence areas, 75.57% of the participants lived in areas with an urbanization level greater than Level 2. Regarding health status, 13.23% of the participants had been diagnosed with catastrophic illnesses; approximately 2.2% had cancer; and 15.58% had been diagnosed with diabetes. Regarding ID severity, 16.2% had mild ID, and 83.8% had moderate to profound severity (Table 1).

3.2 The mammography utilization rate among women with ID

The mammography utilization rate among women with ID was 4.32% (Table 1). A significantly higher mammography utilization rate was observed among women with ID who were married (5.48%), compared with women with ID who were single (1.66%). The mammography utilization rate also differed significantly by education level; women with ID with higher education levels had a higher mammography utilization rate, whereas those who were illiterate or had elementary-level educations had a mammography utilization rate of only 4.03%. The mammography utilization

rate of women with ID who had undergone pap smears (12.51%) was significantly higher than that among women with ID who had not undergone pap smears (1.06%). The mammography utilization rate among women with ID who had used adult preventive health services (8.28%) was significantly higher than that among women with ID who had not used adult preventive health services (3.26%). The

mammography utilization rate among women with ID who had been diagnosed with cancer (9.38%) was significantly higher than that among women with ID who had not been diagnosed with cancer (4.21%). The mammography utilization rate of women with ID who had been diagnosed with diabetes (8.37%) was significantly higher than that of women with ID who had not been diagnosed with diabetes (3.58%). The mammography utilization rate among women with ID differed significantly by their ID levels, and the utilization rate decreased with the severity of ID. Women with mild and profound ID had the highest and lowest mammography utilization rates, of 6.07% and 2.65%, respectively (Table 1).

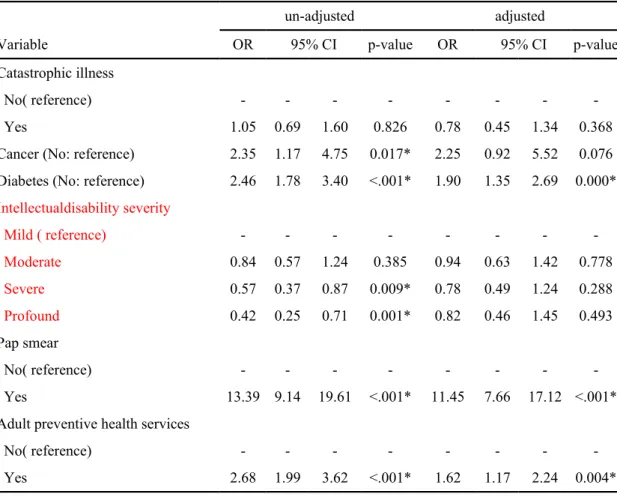

3.3 Factors influencing the mammography utilization among women with ID This study determined that education, pap smear and adult preventive health services utilization, and a diagnosis of diabetes were primary factors that significantly influenced the mammography utilization rate among women with ID (Table 2). The results indicated that the mammography utilization rate of women with ID who had

senior high-level educations and above was 4.56 times higher than that of women who were illiterate or had elementary educations (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4– 14.87). The mammography utilization rate among women with ID who had

undergone pap smears was 11.45 times that of women with ID had not undergone pap smears (95% CI = 7.66–17.12). The utilization rate among women with ID that used adult preventive health services was 1.62 times higher that of women with ID that did not use adult preventive health services (95% CI = 1.17–2.24); the utilization rate of women with ID who had been diagnosed with diabetes was 1.90 times greater than that of women with ID without a diagnosis of diabetes (95% CI = 1.35–2.69).

4. Discussion

This study found that the mammography utilization rate among women with ID in Taiwan was only 4.32%, which was lower than the utilization rates for pap smears and adult preventive health services; furthermore, it was half of that of people with disabilities (8.49%) (Kung, Tsai, & Chiou, 2012), was only one-third of that of women in the general population (12%) (Health Promotion Administration, 2012), and was significantly lower than that among Australian and American women with ID. An unequal situation exists in regard to women with ID accepting breast cancer screening; therefore, public health policy interventions must be implemented to care for people with ID and ensure their rights to health.

Women with ID are seldom targeted in health education, health promotion activities, and health screening (Hanna,Taggart, & Cousins, 2011). In Taiwan, more than 80% of women with ID are diagnosed with severity more than mild. Women with severe or profound ID account for half of the women with ID; after entering adulthood, their mental ages mostly range from 3–6 years, and they cannot be educated. Because they are illiterate, they cannot understand the importance of mammography. Thus, tailored health promotion courses for women with ID were required. Such courses should focus on breast cancer screening knowledge and healthy lifestyles, and use pictures, symbols, signs, and simple words to facilitate an understanding of mammography among women with ID and their caregivers

(Taggart,Truesdale-Kennedy, &McIlfatrick, 2011). Furthermore, actual barriers

preventing women with ID from receiving breast cancer screening include the insufficient knowledge of primary caregivers, negative attitudes, consent problems, physical health, transportation, and inability to schedule a doctor’s appointment. The obstacles of clinical personnel were their attitudes and lack of training for serving women with ID (Kirby & Hegarty, 2010; Taggart,Truesdale-Kennedy, &McIlfatrick,

2011; McIlfatrick,Taggart, & Truesdale-Kennedy, 2011). A UK study showed that only 7.5% of clinical personnel had received training regarding people with ID and cancer (Hanna,Taggart, & Cousins, 2011). When women with ID undergo

mammograms, medical personnel must provide explanations and doctors must explain why mammography must be performed, the details of the examination, and how long it takes. Demonstration methods (e.g., videos) that are intelligible to illiterate viewers should be employed. This is necessary to prepare women with ID to undergo

mammography (Wilkinson et al., 2011).

An Australian study reported that unmarried, urban women with severe ID and concomitant physical disabilities were less willing to receive breast cancer screening (Sullivan et al., 2003). In Taiwan, the majority of women with ID aged above 50 years are married, and the mammography utilization rate among married women is higher. Thus, breast cancer prevention strategies should focus on family members and primary caregivers. Primary caregivers are crucial in providing knowledge regarding breast cancer to women with ID, as well as in-home breast self-examination and screening. One effective strategy was to educate and train women with ID by community ID teams, enabling regular and steady self-examination by primary caregivers (Davies & Duff, 2001).

A study found that recent influenza vaccination was a relevant factor that influenced whether women with ID underwent mammography (Wilkinson, et al., 2011). This study reported that that the mammography utilization rate among women with ID who had diabetes or cancer was higher than that of women with ID without

diabetes or cancer. Because women with ID and chronic diseases or cancer visit the hospital regularly, they are more likely to obtain preventive healthcare. After regular check-ups, a specialist might further suggest mammography. Lantz (1997) also claimed that preventive healthcare utilization was higher among patients who visited the hospital regularly. In a study conducted in Birmingham, UK, people with

disabilities who seldom received treatment were found to be in poor health (Shaw, Maclaurin, & Foster, 1986). Another study found that the major reason patients underwent regular health examination was on the suggestions of doctors (Lerman et al., 1990). This study also discovered that the mammography utilization rate among women with ID who also underwent pap smears or used adult preventive health services was significantly higher. Because mammography is highly uncomfortable, it is a challenge for women with ID. Promoting mammography together with more comfortable practices that have higher utilization rates, such as pap smears and adult preventive health services, is a tenable strategy to increase the mammography

utilization rate. Notably, among women with ID, the relative risk of death from breast cancer versus the relative risk of death from cervical cancer was 7:1, and sexual inactivity is a protective factor against cervical cancer, but nulliparity is a risk factor for breast cancer (Davies & Duff, 2001; Kelsey et al., 1993). Women with ID do not undergo mammography because the examination experience is upsetting (Brown &

Gill, 2009). In addition, following the guidelines for mammography is difficult for women with ID; therefore, breast ultrasounds or clinical breast examination may be attempted as alternatives to resolve this problem (Sullivan et al., 2003) and achieve the objective of protecting women with ID. Furthermore, enhancing the education among primary caregivers and women with ID regarding breast self-examination, early signs and symptoms of breast cancer, and establishing healthy lifestyles as a protective factor is necessary to reduce cancer risk and morbidity (Hanna,Taggart, &

Cousins, 2011).

5. Conclusion

In Taiwan, the mammography utilization rate among women with ID is significantly lower than that among women in the general population. The primary factors influencing the mammography utilization among women with ID were education level, a diagnosis of diabetes, use of pap smear and adult preventive health services utilization. People with ID are different from people with disabilities, but share the same rights to health. Different planning strategies must be adopted in public health policy to improve the perceptions of primary caregivers and clinical personnel in assisting women with ID in establishing healthy lifestyles and diagnosing breast cancer at an early stage to decrease cancer mortality risk.

6. Limitations

The research resources employed in this study were the secondary databases and certain relevant factors could not be identified, such as health behaviors and health perceptions of women with ID and their primary caregivers. In addition, this study could not distinguish the study participants living in an institution or living with family members.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants (CMU101-ASIA-14, DOH9805006A) from China Medical University, Asia University, and the Health Promotion Administration. The preventive healthcare files were obtained from the Health Promotion

Administration, Taiwan. We are also grateful for the use of the National Health Insurance Research Database as provided by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. The interpretations and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Health Promotion Administration, Taiwan.

REFERENCES

Blanks, R.G., Moss, S.M., McGahan, C.E., Quinn, M.J.& Babb, P.J.(2000). Effect of NHS breast screening programme on mortality from breast cancer in England and Wales, 1990–8: comparison of observed with predicted mortality. British Medical Journal, 321, 665–669.

Brown, A.A., Gill, C.J.(2009). New voices in women’s health: perceptions of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual Developmental

Disabilities, 47(5), 337-347.

Bureau of Health Promotion. (2012). Statistical report of Bureau of Health Promotion. Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Cobigo, V., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Balogh, R., Leung, F., Lin, E. & Lunsky, Y. (2013). Are cervical and breast cancer screening programmes equitable? The case of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of

Intellectual Disability Research, 57(5), 478-88.

Davies, N., Duff, M. (2001). Breast cancer screening for older women with intellectual disability living in community group homes. Journal of

Intellectual Disability Research, 45(3), 253–257.

Ewing, G., McDermott, S., Thomas-Koger, M., Whitner, W. & Pierce, K. (2004). Evaluation of a cardiovascular health program for participants with mental retardation and normal learners. Health Education and Behaviours, 31, 77–87.

Hanna, L.M., Taggart , L. & Cousins, W. (2011). Cancer prevention and health promotion for people with intellectual disabilities: an exploratory study of staff knowledge. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(3), 281-91.

Judkins, A.F., Akins, J. (2001). Breast cancer: initial diagnosis and current treatment options. Nursing Clinics of North America, 36(3), 527–542.

Kelsey, J.L., Gammon, M.D. & John, E.M. (1993). Reproductive factors and breast cancer. Epidemiology Review. 15(1), 36-47.

Kirby, S., Hegarty, J. (2010). Breast awareness within an intellectual disability setting. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14(4), 328-336.

Kung, P. T., Tsai, W. C. & Chiou, S. J. (2012). The assessment of the likelihood of mammography usage with relevant factors among women with disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(1), 136-143.

Kung, P. T., Tsai, W. C. & Li, Y. H. (2012). Determining factors for utilization of preventive health services among adults with disability in Taiwan. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(1), 205-213.

Lantz, P. M., Weigers, M. E. & House, J.S. (1997). Education and income

differentials in breast and cervical cancer screening. Policy implications for rural women. Medical Care, 35(3), 219-236.

Lerman, C., Rimer, B., Trock, B., Balshem, A. & Engstrom, P. F. (1990). Factors associated with repeat adherence to breast cancer screening. Preventive Medicine,

19(3), 279-90.

McIlfatrick, S., Taggart, L. & Truesdale-Kennedy, M . (2011). Supporting women

with intellectual disabilities to access breast cancer screening: a healthcare professional perspective. European Journal of Cancer Care , 20(3), 412-20.

McPherson, K., Steel, C.M. & Dixon, J.M. (2000). Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, and genetics. British Medical Journal,321,624–628.

McGuire, B. E., Daly, P. & Smyth F. (2007). Lifestyle and health behaviours of adults with an intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research , 51, 497– 510.

Ministry of the Interior. (2012). Statistical report of interior. R.O.C. Taipei Taiwan.

Patja, K., Eero, P. & Livanainen, M. (2001). Cancer incidence among people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 45, 300–307.

Parish, S.L., Swaine, J. G., Son, E. & Luken, K. (2013). Receipt of mammography among women with intellectual disabilities: medical record data indicate substantial disparities for African American women. Disability and Health Journal, 60(1)36-42.

Shaw, L., Maclaurin, E. T. & Foster, T. D. (1986). Dental study of handicapped children attending special schools in Birmingham, UK. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 14(1), 24-27.

Sullivan, S.G., Glasson, E.J., Hussain, R., Petterson, B.A., Slack-Smith, L.M., Montgomery, P.D. & Bittles, A.H. (2003). Breast cancer and the uptake of mammography screening services by women with intellectual disabilities. Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 507-12.

Taggart, L., Truesdale-Kennedy, M. & McIlfatrick, S. (2011). The role of community nurses and residential staff in supporting women with intellectual disability to access breast screening services. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(1), 41-52. Temple,V. A. & Walkley, J.W. (2003). Physical activity of adults with intellectual

disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 28(4), 342–353. Willett, W.C. (2001). Diet and breast cancer. Journal of Internal Medicine, 249, 395–

411.

Wilkinson, J.E., Deis, C.E., Bowen, D.J. & Bokhour, B.G. (2011).‘It’s easier said than done’: perspectives on mammography from women with intellectual disabilities. Annals of Family Medicine, 9(2), 142-147.

Wilkinson, J.E., Lauer, E., Freund, K.M. & Rosen, A.K. (2011). Determinants of mammography in women with intellectual disabilities. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 24(6), 693-703.

Table1.2007-2008 mammography utilization among women with ID and bivariate analysis Used Non-use χ2 Variable % n1=189 % n2=4181 % p-value Gender -Women 4370 100.00 189 4.32 4181 95.68 Age 0.1 50-59years 3024 69.20 141 4.66 2883 95.34 60-69years 1346 30.80 48 3.57 1298 96.43

Urbanization of residence area 0.341

1 360 8.24 15 4.17 345 95.83 2 708 16.20 29 4.10 679 95.90 3 624 14.28 29 4.65 595 95.35 4 438 10.02 29 6.62 409 93.38 5 770 17.62 31 4.03 739 95.97 6 609 13.94 20 3.28 589 96.72 7 613 14.03 27 4.40 586 95.60 8 248 5.68 9 3.63 239 96.37 Monthly salary(NT$) 0.331 Dependent 1502 34.37 73 4.86 1429 95.14 <15,840 2189 50.09 81 3.70 2108 96.30 16,500-22,800 596 13.64 30 5.03 566 94.97 24,000-28,800 43 0.98 3 6.98 40 93.02 30,300-36,300 40 0.92 2 5.00 38 95.00 Aboriginal 0.775 Yes 38 0.87 2 5.26 36 94.74 No 4332 99.13 187 4.32 4145 95.68 Education level 0.041* Elementary or illiterate 3595 82.27 145 4.03 3450 95.97

Junior high school 151 3.46 5 3.31 146 96.69

Senior (vocational) high school 44 1.01 4 9.09 40 90.91 Junior college and university or above 14 0.32 2 14.29 12 85.71

Unknown 566 12.95 33 5.83 533 94.17

Marital status 0.000*

Married 2062 47.19 113 5.48 1949 94.52

Table1.2007-2008 mammography utilization among women with ID and bivariate analysis(continued) Used Non-use χ2 Variable % n1=189 % n2=4181 % p-value Divorce or widow 284 6.50 13 4.58 271 95.42 Unknown 1240 28.38 50 4.03 1190 95.97 Catastrophic illness 0.826 Yes 578 13.23 26 4.50 552 95.50 No 3792 86.77 163 4.30 3629 95.70 Cancer 0.014* Yes 96 2.20 9 9.38 87 90.63 No 4274 97.80 180 4.21 4094 95.79 Diabetes <.001* Yes 681 15.58 57 8.37 624 91.63 No 3689 84.42 132 3.58 3557 96.42 Intellectualdisability severity 0.001* Mild 708 16.20 43 6.07 665 93.93 Moderate 1489 34.07 77 5.17 1412 94.83 Severe 1304 29.84 46 3.53 1258 96.47 Profound 869 19.89 23 2.65 846 97.35 Pap smear <.001* Yes 1247 28.54 156 12.51 1091 87.49 No 3123 71.46 33 1.06 3090 98.94

Adult preventive health services <.001*

Yes 930 21.28 77 8.28 853 91.72

No 3440 78.72 112 3.26 3328 96.74

Table 2 Logistic regression models for utilization of mammography among women with ID

un-adjusted adjusted

Variable OR 95% CI p-value OR 95% CI p-value

Age

50-59years(reference) - - -

-60-69years 0.76 0.54 1.06 0.101 0.81 0.57 1.16 0.255

Urbanization of residence area

1(reference) - - - -2 0.98 0.52 1.86 0.956 0.86 0.43 1.71 0.658 3 1.12 0.59 2.12 0.725 0.87 0.44 1.74 0.696 4 1.63 0.86 3.09 0.134 1.27 0.63 2.56 0.497 5 0.97 0.51 1.81 0.911 0.69 0.35 1.36 0.284 6 0.78 0.40 1.55 0.478 0.55 0.27 1.15 0.113 7 1.06 0.56 2.02 0.860 0.73 0.36 1.47 0.372 8 0.87 0.37 2.01 0.738 0.48 0.19 1.19 0.115 Monthly salary(NT$) <15,840 (reference) - - - -Dependent 1.33 0.96 1.84 0.084 1.34 0.91 1.99 0.141 16,500-22,800 1.38 0.90 2.12 0.142 1.40 0.85 2.32 0.191 24,000-28,800 1.95 0.59 6.44 0.272 1.68 0.47 5.96 0.426 30,300-36,300 1.37 0.33 5.78 0.668 1.40 0.31 6.37 0.661 Aboriginal No(reference) - - - -Yes 1.23 0.29 5.15 0.775 1.14 0.25 5.27 0.867 Education level

Elementary or illiterate( reference) - - -

-Junior high school 0.82 0.33 2.02 0.658 0.94 0.36 2.45 0.898 Senior (vocational) high school 2.38 0.84 6.74 0.103 4.56 1.40 14.87 0.012* Junior college and university or above 3.97 0.88 17.88 0.073 5.45 0.90 33.11 0.066

Unknown 1.47 1.00 2.17 0.051 1.43 0.93 2.20 0.101 Marital status Single( reference) - - - -Married 3.44 1.93 6.14 <.001* 1.44 0.76 2.73 0.266 Divorce or widow 2.85 1.30 6.21 0.009* 1.49 0.64 3.46 0.361 Unknown 2.49 1.35 4.62 0.004* 1.21 0.62 2.36 0.587

Table 2 Logistic regression models for utilization of mammography among women with ID(continued)

un-adjusted adjusted

Variable OR 95% CI p-value OR 95% CI p-value

Catastrophic illness

No( reference) - - -

-Yes 1.05 0.69 1.60 0.826 0.78 0.45 1.34 0.368

Cancer (No: reference) 2.35 1.17 4.75 0.017* 2.25 0.92 5.52 0.076 Diabetes (No: reference) 2.46 1.78 3.40 <.001* 1.90 1.35 2.69 0.000* Intellectualdisability severity Mild ( reference) - - - -Moderate 0.84 0.57 1.24 0.385 0.94 0.63 1.42 0.778 Severe 0.57 0.37 0.87 0.009* 0.78 0.49 1.24 0.288 Profound 0.42 0.25 0.71 0.001* 0.82 0.46 1.45 0.493 Pap smear No( reference) - - - -Yes 13.39 9.14 19.61 <.001* 11.45 7.66 17.12 <.001* Adult preventive health services

No( reference) - - -

-Yes 2.68 1.99 3.62 <.001* 1.62 1.17 2.24 0.004*