影響大眾環境風險認知及政策支持因素之跨層次分析 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 影響大眾環境風險認知及政策支持因素之跨層次分析 Predicting Environmental Risk Perception and Policy Support: A Multilevel Model. 研究生: 蘇民欣. Student: Min-Hsin Su. 指導教授: 施琮仁. 政 治 大. 學. ‧ 國. 立. Advisor: Tsung-Jen Shih. 國立政治大學. ‧. 國際傳播英語碩士學位學程. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. 碩士論文. Ch. eAnThesis gchi. i n U. v. Submitted to International Master’s Program in International Communication Studies National Chengchi University In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the degree of Master of Arts. 中華民國 103 年 3 月 March 2014 II.

(3) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Tsung-Jen Shih, my thesis advisor, for his constant support and guidance during the course of this investigation. Dr. Shih has provided me with valuable insights about research and about life, showing me how to be an independent thinker and a warm person. Deepest appreciation also goes to my committee members, Dr. Mei-Ling Hsu and Dr. Wen-Ying Liu, whose constructive suggestions and kind encouragement have greatly contributed to the completion of this thesis.. 政 治 大 I am also indebted to all my立 kind and generous friends, who kindly share with me. ‧ 國. 學. their thoughts, feelings, and life stories. They see me becoming the person I am. I would also like to thank Yu-Ting Chen for his unconditional love and support. With. ‧. him by my side, every adventure is like coming back home. Finally, I would like to. sit. y. Nat. express my deepest love and gratitude to my family for their complete trust and. n. al. er. io. support for every decision I made in life.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. This thesis marks a particular stage of my life, recording numerous important events that happened along the way. I believe all the strengths and nutrition acquired in this process will be with me on my next journey.. Min-Hsin Su March, 2014. III.

(4) ABSTRACT Environmental issues have received much public and media attention abroad and at home. With the increased environmental awareness, there is a strong call for relevant policies and regulations aimed at sustainable development. To ensure sufficient public support, it is crucial to develop a fuller understanding of factors and processes underlying people’s willingness to help protect the environment when making decisions as consumers and citizens. This study aims to predict people’s environmental risk perception and policy support as a function of their values. Specifically, Schwartz’s self-transcendence and self-enhancement value clusters will be examined as determinants to understand why few people choose to make collectively beneficial decisions. Three extensions were made. First, instead of focusing on low-cost lifestyle changes, this study examined policy support that requires substantial personal costs. Second, global and local environmental risk perceptions are treated as two qualitatively different constructs according to their geographical scales. Finally, this study moves beyond an individualistic approach, incorporating country-level forces into the model. Information about the individuals are based on variables measured in the World Value. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Survey (2005), while cultural orientations and levels of development are measured by the Schwartz Value Survey (2005) and the Human Development Index (2005) respectively. Hierarchical regression are employed, with the nature of interaction being revealed by plotting techniques. The results suggested that perception and responses to environmental risks reflect their most basic value priorities and life goals. Consequently, environmental persuasive messages are most effective when intended behaviors are framed as fulfilling important life goals. However, the effects of person-level constructs greatly vary with social contexts and issue scales, suggesting that different strategies are. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. preferred when dealing with risks associated with different geographical frame. Finally, cultural orientations and levels of development will influence the way members of a society respond to environmental threats. Practical implications for environmental risk communication are proposed and discussed.. Keywords: environmental risk perception, policy support, self-transcendence, self-enhancement, cultural orientation, development levels. IV.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 Literature Review ........................................................................................................ 7 Environmental Risk Perception ................................................................................. 9 Definition ............................................................................................................... 9 Predicting Environmental Risk Perception .......................................................... 10 Environmental Policy Support ................................................................................. 11 Definition ............................................................................................................. 11 Predicting Environmental Policy Support ........................................................... 11 Personal Values ........................................................................................................ 12 Definition ............................................................................................................. 12 Schwartz’s Model of Basic Human Values .......................................................... 13 Self-transcendence and Self-enhancement .............................................................. 16 Risk Perception and Policy Support ........................................................................ 18 Geographical Scales of Environmental Risks .......................................................... 19 Moderating Value-Perception Relations .............................................................. 21 Moderating Perception-Support Relations ........................................................... 22. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Country-level Influences .......................................................................................... 23 Cultural Orientation ............................................................................................. 24 Development Levels ............................................................................................ 30 Country-level Characteristics as Moderators ....................................................... 33. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. Methods ....................................................................................................................... 39 Data .......................................................................................................................... 39 World Value Survey ............................................................................................. 40 Cultural Orientation ............................................................................................. 41 Development Levels ............................................................................................ 42. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Measurement ............................................................................................................ 42 Environmental Risk Perception ........................................................................... 42 Environmental Policy Support ............................................................................. 43 Personal Values .................................................................................................... 44 Cultural Orientation ............................................................................................. 45 Development Levels ............................................................................................ 45 Control ................................................................................................................. 45 Analytical Approach ................................................................................................ 47 Hierarchical Linear Regression............................................................................ 47 Plotting the Interaction ......................................................................................... 47. V.

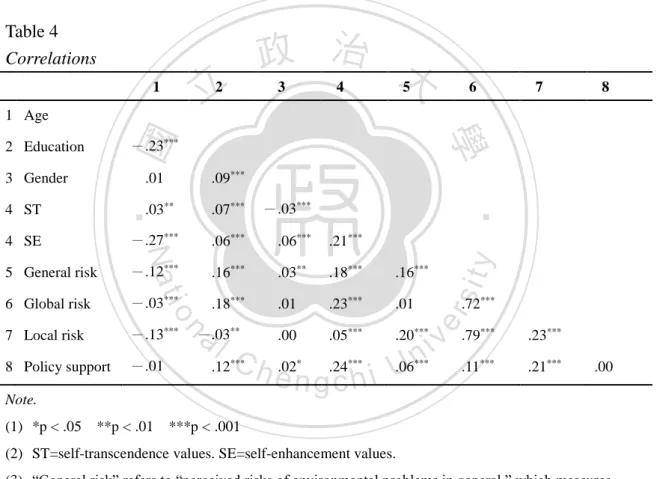

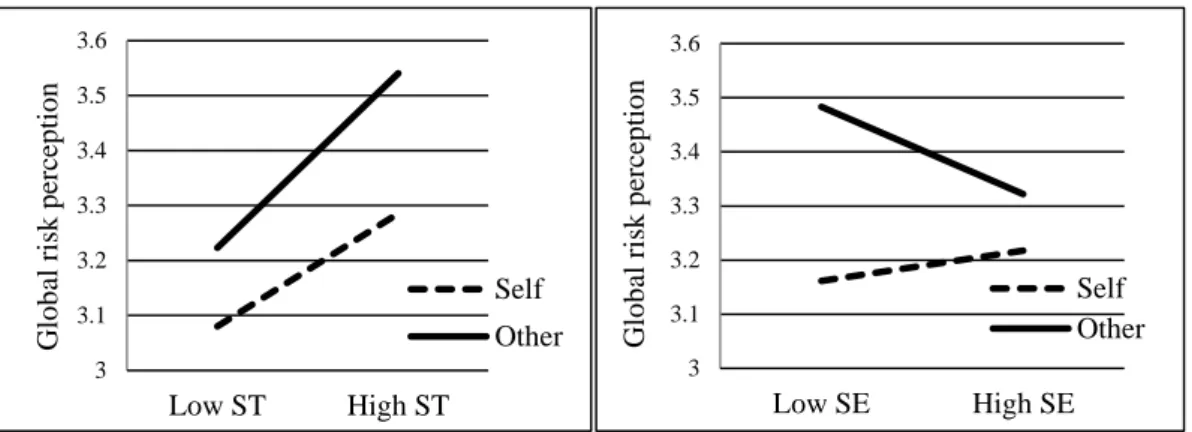

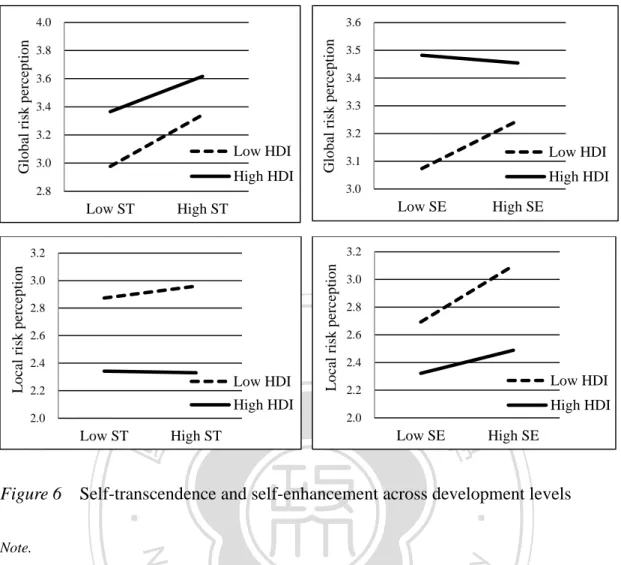

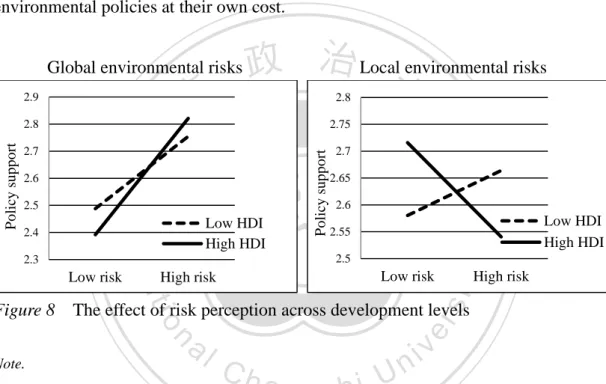

(6) Result........................................................................................................................... 50 Person-level Influences ............................................................................................ 51 Country-level Influences .......................................................................................... 56 Direct Effects ....................................................................................................... 56 Cross-level Moderation: Value-Perception Relations .......................................... 58 Cross-level Moderation: Perception-Support Relations ...................................... 63 Discussion.................................................................................................................... 66 Demographics .......................................................................................................... 67 Age ....................................................................................................................... 67 Education ............................................................................................................. 68 Gender .................................................................................................................. 69 Self-transcendence and Self-enhancement Values ................................................... 71 Environmental Risk Perception and Policy Support ................................................ 72 Country-level Characteristics as Direct Effects ....................................................... 73 Cultural Orientation ............................................................................................. 74. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Development Levels ............................................................................................ 75 Cross-level Interaction ............................................................................................. 76 Moderating the Effect of Self-transcendence ...................................................... 77. ‧. Moderating the Effect of Self-enhancement ........................................................ 77 Moderating the Effect of Risk Perception on Policy Support .............................. 79 Practical Implications............................................................................................... 80 The Case of Taiwan.................................................................................................. 82 Limitations and Implications for Future Studies ..................................................... 83. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. i n U. v. Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 87. Ch. engchi. References ................................................................................................................... 90 Appendix. VI.

(7) LIST OF TABLES Schwartz’s model of basic human values .................................................... 14 Schwartz’s model of cultural dimensions .................................................... 28 Descriptive statistics .................................................................................... 46 Correlations .................................................................................................. 50 Hierarchical regression predicting environmental risk perception and policy support at the individual level .…..………………………………...52 Table 6 Global and local risk perception across nations ........................................... 53 Table 1 Table 2 Table 3 Table 4 Table 5. Table 7 Hierarchical regression predicting environmental risk perception and policy support across geographical scales…………………………………54 Table 8 The role of global risk perception and local risk perception in shaping policy support across nations ....................................................................... 56 Table 9 Hierarchical regression predicting environmental risk perception and policy support based on individual attributes and country-level factors ..... 58. 立. 政 治 大. Table 10 Cross-level moderation ................................................................................. 59. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. VII. i n U. v.

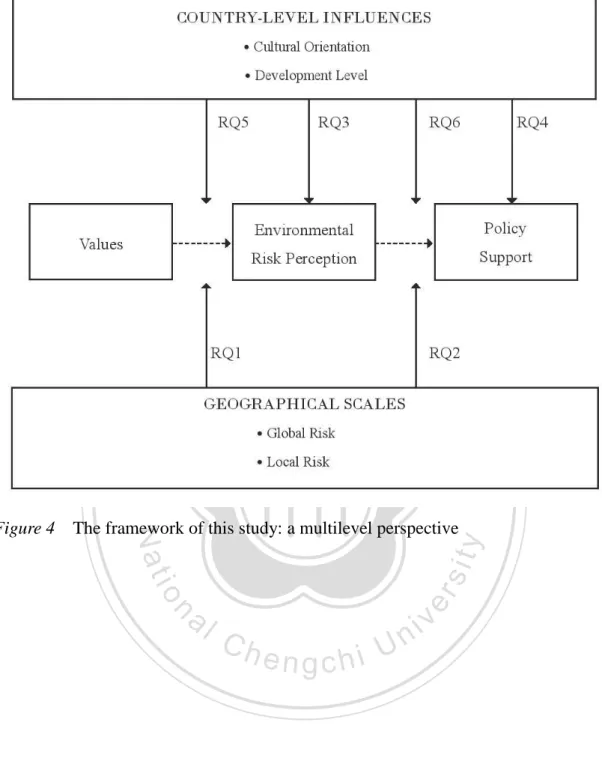

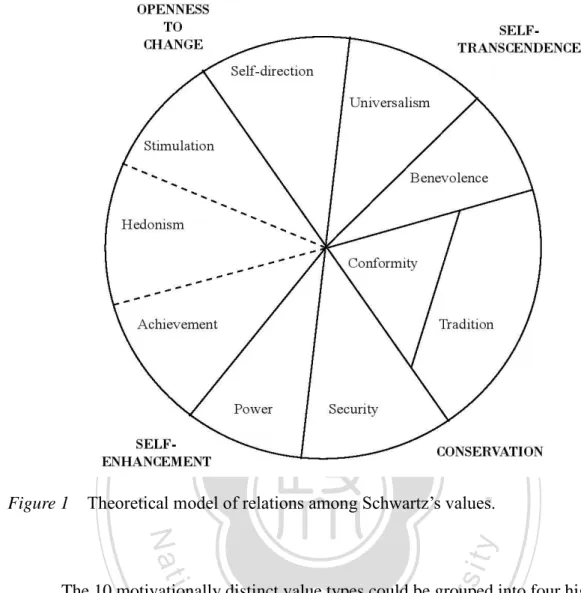

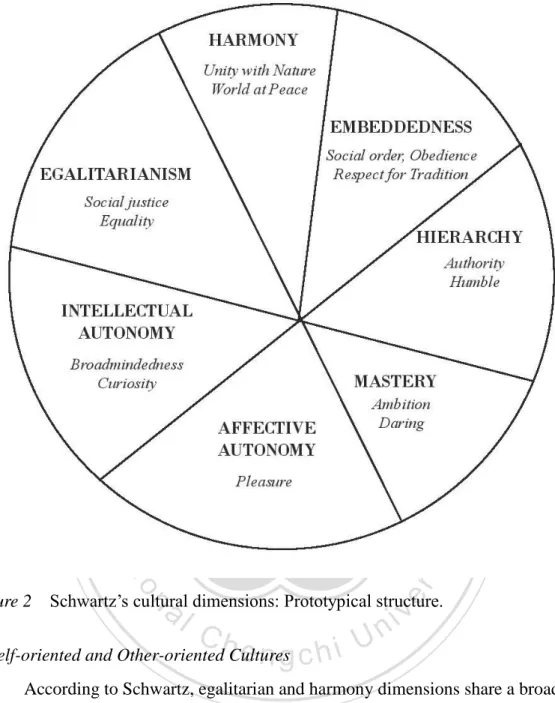

(8) LIST OF FIGURE Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5 Figure 6 Figure 7. Theoretical model of relations among Schwartz’s values………………...15 Schwartz’s cultural dimensions: Prototypical structure…….…………… 29 The framework of this study: an individual-level analysis…...……...…...37 The framework of this study: a multilevel perspective .............................. 38 Self-transcendence and self-enhancement across cultural contexts ........... 61 Self-transcendence and self-enhancement across development levels ....... 62 The effect of risk perception across cultural contexts….. .......................... 64. Figure 8. The effect of risk perception across development level ............................. 65. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. VIII. i n U. v.

(9) Introduction. Environmental issues have received much public and media attention in the past few years. With the increased environmental awareness, there is a strong call both from the environmentalists and the general public for more environmental policies and regulations being made by the governments and companies around the world. However, any policies and regulations must have strong support from the public to yield substantial effects. As a consequence, it is crucial to develop a fuller understanding of factors and processes underlying people’s willingness to help protect. 政 治 大. the environment when making decisions as consumers and citizens.. 立. There is a growing body of literature suggesting that people’s environmental. ‧ 國. 學. beliefs and behaviors are greatly influenced by their fundamental worldviews and values (Bamberg & Möser, 2007; Biel & Nilsson, 2005;Hansla, et al., 2013;. ‧. Leiserowitz, 2006; Milfont, et al., 2010; Milfont, et al., 2010; Poortinga, et al., 2011).. y. Nat. io. sit. For example, those with materialist or individualist values are found to be less. n. al. er. concerned about environmental issues (Kilbourne, Grünhagen, & Foley, 2005). As. i n U. v. people’s perception and responses to environmental risks are expressions of more. Ch. engchi. fundamental values, it would be difficult to change one’s environmentally unfriendly behavior without first addressing underlying values that motivate and provide coherence for such behaviors (Schultz & Zelezny, 2003;Smallbone, 2005). Given the importance of values, this study aims to predict people’s environmental risk perception and policy support as a function of their broad values. In an attempt to investigate the role of values, Schwartz’s theory of basic human values (1992) is used as the categorizing structure that identified ten motivationally distinct value types based on findings obtained from 97 samples in 44 countries from all inhabited continents between 1988 and 1993. These ten value types 1.

(10) (achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security) could be grouped into four higher order value clusters organized as two bipolar dimensions. The first dimension contrasts self-enhancement with self-transcendence, while the second dimension contrasts openness to change with conservatism (Schwartz, 2006). With the specific research goal, the thesis will focus on self-transcendence and self-enhancement values, as they express the degree to which individuals put their own interests ahead of others. In general, past studies predicting public environmental concerns based on. 政 治 大 Slimak & Dietz, 2006;Whitfield et al., 2009) tend to suggest that people with stronger 立. self-transcendence and self-enhancement values (e.g., Onur, Sahin, & Tekkaya, 2012;. self-transcendence values (e.g., helping, responsible, forgiving) are more sensitive to. ‧ 國. 學. environmental risks and report higher levels of commitment than those putting. ‧. emphasis on self-enhancement values (e.g., power, achievement, social recognition).. io. er. aspects unexplored, calling for further investigation.. sit. y. Nat. Despite some useful insight, these value-basis studies still have several important. First, a great number of studies focused their attention on general. al. n. v i n C hlifestyle changes,Usuch as recycling (Barr, 2007; environmental concerns or low-cost engchi Chung & Leung, 2007), household energy use (Poortinga, Steg, & Vlek, 2004;Steg,. 2008), or green purchase intention (Hansen, Risborg, & Steen, 2012; Zagata, 2012). Few studies probed into levels of commitment when substantial costs are involved and specified. This neglects an important aspect of environmental protection as a social dilemma, when the public are often faced with a choice either to maximize collective good, or to act upon personal interests (Dawes, 1980, as quoted in Gupta & Ogden, p. 378, 2009).The open conflict between self-interests and care for others explain why few people choose to make collectively beneficial decisions despite widespread concerns for the environment expressed in the abstract (Costarelli & 2.

(11) Colloca, 2004; Leiserowitz, Kates, & Parris, 2006; Markle, Thompson, & Wallace, 2011). Hence, to view environmental protection as a social dilemma, the present study focuses on factors predicting environmental policy support rather than lifestyle behavioral changes, as it often involves substantial personal costs but has less observable environmental impact. Second, most environmental psychology studies do not distinguish environmental issues associated with different geographical scales (e.g., Stern, Dietz, & Kalof, 1993). In this way, broad and distant threats are not distinguished from. 政 治 大 psycho-spatial distance of environmental risks could be crucial in terms of 立. situated and close-to-home dangers. Some scholars, however, suggested that the. understanding the public’s environmental attitudes and subsequent behaviors (Gökşen,. ‧ 國. 學. Adaman, & Zenginobuz, 2002; Gifford et al., 2009). Therefore, it is suggested that the. ‧. global/international environment and the local/national environmental should be. sit. y. Nat. viewed as two separate contexts in order not to miss important qualitative differences. io. er. between broad risks to the world and close-to-home risks to the local community (Gifford, 2011; Schultz et al., 2005; Spence & Pidgeo, 2010; Uzzell, 2007). The. al. n. v i n C hwith respect to people’s distinctions between spatial scales environmental risk engchi U. perception constitute an area of research that calls for further investigation (Lai et al., 2003). Thereby, in exploring the link between values, risk perception, and policy support, global and local risks are considered separately. Third, previous studies have predominantly argued from an individualistic perspective, exploring relations between individuals’ psychological constructs such as values and beliefs at the individual level (Boeve-de Pauw & Van Petegem, 2013; Roccas & Sagiv, 2010). However, as individuals are born into, and grow up in larger socio-cultural contexts, the way they perceive and respond to environmental risks are inevitably influenced by forces beyond their own attributes (Beck, Lash, & Giddens, 3.

(12) 1997). As such, this thesis put the individual back into the context, examining both personal attributes and country-level characteristics as predictors of public risk perception and policy support, as well as a potential interaction between the two layers of constructs (Bond, 2002; McLeod, Pan, & Rucinski, 1995). Among all features that define a nation at the aggregate, cultural orientation and development level are included into this multi-level model, as these two dimensions are believed to provide important reference frames regarding what values are desirable and what kind of behavior is appropriate (Lehman, Chiu, & Schaller, 2004; Matsumoto & Juang, 2008).. 政 治 大 With these research goals, this study draws upon data both about personal 立. factors and contextual influences. Information pertaining to the individuals was based. ‧ 國. 學. on variables measured in the 2005 World Value Survey (WVS). Using nationally. ‧. representative samples, this module provides the latest available data on a wide range. sit. y. Nat. of basic values and beliefs across nations by the time this thesis is composed. The use. io. er. of WVS largely minimizes the validity and reliability problems typically associated with cross-cultural research (Jen, Jones, & Johnston, 2009). At the aggregate level,. al. n. v i n C hwere obtained based nation scores for cultural orientation on data from Schwartz engchi U. Value Survey provided by the Israel Social Sciences Data Center (ISDC) from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, while development levels are measured by the Human Development Index. The reasons for choosing Schwartz’s model as the primary theoretical framework in comparing culture across nations are as follows. First, unlike many other models that provide categorizing structures only at the aggregate (e.g., Hofstede, 2001; Inglehart, 1997; Wildavsky & Dake, 1990), Schwartz proposed instruments intended to measure value differences across individuals and across nations, which allows for an investigation of potential interactions between constructs at two levels 4.

(13) (2006). More importantly, Schwartz’s model has dimensions that directly address the degree to which a society promotes the pursuit of self-interests and care for others, a core aspect this study attempts to probe into. Additionally, unlike a number of widely used cultural models that derived their dimensions based exclusively on modern Western-centered nations, Schwartz’s dimensions were derived from cross-cultural data covering a fuller heterogeneity of cultures, bringing into countries where value systems were influenced by state socialism (e.g., China, Poland, Estonia, East Germany, Hungary, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Zimbabwe) and other often neglected. 政 治 大 present study from previous ones, as Schwartz’s cultural dimensions are less explored 立. forces (Schwartz, 1994a). The use of Schwartz’s cultural model also distinguishes the. in the field of environmental psychology, compared to some widely used categorizing. ‧ 國. 學. structures such as Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (2001), Wildavsky and Dake. ‧. (1990)’s cultural theory, and Inglehart (1997)’s postmaterialism theory. As a. io. er. Schwartz’s value dimensions can be revealed.. sit. y. Nat. consequence, it is hoped that the potentially underscored theoretical value of. It is worth noting that although Schwartz’s complete model proposes ten. al. n. v i n motivationally distinct values atC the individual level and h e n g c h i U seven cultural orientations at the aggregate, this study will focus on self-transcendence and self-enhancement as. two important person-level life goals. Likewise, the analysis will be constrained to the influence of self-oriented versus other-oriented culture, for this cultural dimension is the most relevant in the contexts of this study addressing the conflict between self-interests and common welfare. Hierarchical regression was used as the primary statistical tool, in which individual- and country-level variables were entered into the model according to their causal order of relationship. To further assess the moderating role of geographical scales and cultural orientation, interactions terms were computed and entered into the 5.

(14) model as the last block, with the nature of interaction being revealed by plotting techniques. The significance of this study lies in several aspects. First, it moves beyond low-cost individual behavioral change that past studies typically addressed, focusing instead on policy support involving explicit financial sacrifice and less observable environmental impact. Second, environmental risks are distinguished by their geographical scales, hoping to bring more insight for the design and communication of environmental messages. Finally, to supplement previous studies that limited their. 政 治 大 beyond an individualistic approach commonly seen in most environmental research, 立 scope and findings to national or even regional samples, the present study moves. addressing the issue from a multi-level perspective in a cross-national context. By. ‧ 國. 學. exploring the relationship among individual psychological constructs within a. ‧. cross-cultural research framework, the present study integrates social-psychological. sit. y. Nat. and cross-cultural perspectives of public support for environmental protection,. io. er. allowing for a broader and more complete understanding of this phenomenon. Significant implications will be discussed in terms of the design of. al. n. v i n C hmessages targetingUdifferent cultural groups and environmental risk communication engchi dealing with issues of different geographical proximity. With more find-tuned and. value-congruent appeals and strategies used, it is hoped that meaningful and durable public commitment to environmental protection will be generated, even in face of substantial personal costs.. 6.

(15) Literature Review. Past research exploring factors influencing people’s environmental concerns and behaviors mainly consists of two streams. One line of studies focused on socio-demographics such as age or gender as determinants (e.g., Berger, 1997; Felix, Asuamah, & Darkwa, 2013; Kalof, Dietz, Guagnano, & Stern, 2002). Studies of the second stream, however, suggested that structural variables were not by themselves reliable predictors of environmental engagement (Dietz, Kalof, & Stern, 2002). Rather, broader values that people hold onto as their primary life goals may play a larger part,. 政 治 大. influencing the way people perceive and respond to environmental threats (Bamberg. 立. & Moser, 2007; Schultz et al., 2005; Nordlund & Garvill, 2002).. ‧ 國. 學. There is a growing body of literature linking people’s value priorities to their environmental risk concerns and subsequent behaviors (Milfont et al., 2010). For. ‧. example, researcher suggested that those holding on to conservative values (Schultz &. y. Nat. io. sit. Zelezny, 2003; Stern et al., 2008; Whitfield, Rosa, Dan, & Dietz, 2009), materialistic. n. al. er. values (Kilbourne & Pickett, 2008), or individualist values (Carlisle & Smith, 2005;. i n U. v. Contorno, 2012; Marris et al., 2006) tend to be less sensitive to environmental risks.. Ch. engchi. Additional studies demonstrated that decreased risk perception was associated with lower willingness to support environmental policies and regulations (Amerigo & Gonzalez, 2001; Corraliza & Berenguer 2000; Schultz, 2001; Story & Forsyth, 2008; Kilbourne et al., 2001; Oreg et al., 2006). Although these studies have offered some useful insight into how values might influence people’s environmental risk perception and policy support, there are still several important less-explored dimensions that call for further investigation. First, a majority of environmental protection studies focused only on general concerns expressed at the abstract, or low-cost behavioral changes that do not have substantial 7.

(16) impact, such as refusing plastic bags or purchasing recycled papers (Gatersleben, Steg, & Vlek, 2002; Poortinga et al., 2004). Other forms of commitment, such as supporting environmental policies and regulations, though only affecting the environment indirectly, may have larger impact on the environment. This line of studies, however, has received far less attention (Stern, 2000). More importantly, such low-cost behavior studies (e.g., Marquart-Pyatt, 2012) failed to address the potential conflicts inherent in many environmentally protective behaviors between pursuing self-interests through the exploitation of nature and cooperating for long-term. 政 治 大 beneficial decisions even when perfectly aware of the long-term benefits protecting 立 collective welfare. This explains why few people are willing to make collectively. the environment will bring to the society as a whole (Gupta & Ogden, 2009).. ‧ 國. 學. Consequently, forms of environmental engagement examined in previous studies need. sit. y. Nat. impact but require substantial personal costs.. ‧. to be extended to other public-oriented behaviors that bring tangible environmental. io. er. Second, most environmental psychology studies do not distinguish between risks at different spatial scales (e.g., Milfont & Sibley, 2012; Onur, et al., 2012;. al. n. v i n Nordlund & Garvill, 2003; SternCet al., 1993; Steg, Dreijerink, & Abrahamse, 2005). hengchi U. However, it is suggested that the global/international and local/national environments are better treated as two separate spatial contexts in order not to miss important qualitative differences between broad risks to the world and local risks to one’s community (Gifford, 2011; Spence & Pidgeo, 2010; Uzzell, 2004; Schultz et al., 2005). This psycho-spatial distance has important implications in understanding how the public perceive and respond to different environmental threats (Olli et al., 2001; Schultz et al., 2005; Uzzell, 2000). To address this gap, this study will distinguish environmental risks according to their associated geographical scales. The third limitation is that the role of values in relation to environmental risk 8.

(17) perception and policy support has been predominantly examined at the individual level (e.g., Milfont, Wilson, & Diniz, 2012). Few studies attempted to explore whether individual psychological attributes such as values and risk perception will have different effects across nations with different cultural emphases and development levels (Boeve-de Pauw & Van Petegem, 2013; Franzen & Meyer, 2010). As a consequence, the present study is hoping to contribute to the literature by bringing into contextual influences beyond personal traits. What’s more, country-level characteristics will be examined not only as direct effects but also as potential. 政 治 大 the individual level will vary across cultural contexts. The next section is a short 立. cross-level moderatos. This will allow us to know whether relations typically found at. review of studies that predict people’s environmental risk perception and policy. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. support.. y. sit. io. er. Definition. Nat. Environmental Risk Perception. Environmental risk perception is defined as people’s judgment and assessment. al. n. v i n C h that might poseUimmediate or long-term threats of environmental hazards and dangers engchi. to their health and well-being (Adeola, 2007). Many studies have found that. perception of environmental risks is an important cognitive precondition for subsequent proenvironmental behaviors (Brody, Zahran, Vedlitz, & Grover, 2008; Oreg et al., 2006; Spence, Poortinga, Butler, & Pidgeon, 2011). For example, Oreg et al. (2006) found that perceived environmental threat enhances public engagement in a range of proenvironmental behaviors across 27 countries (i.e., recycling, refraining from driving, and environmental citizenship). Bain et al. (2012) also argued that to secure sustainable public support for environmental policies, it is necessary to convince the public of the existence and 9.

(18) seriousness of environmental threats.. Predicting Environmental Risk Perception Several theories have been proposed to explain why different people make different estimates of the severity of risks. A large number of studies predicting environmental risk perception were conducted within the psychometric paradigm (Slovic, 2010; Sjöberg, Moen, & Rundmo, 2004; Slovic, Finucane, & Peters, & MacGregor, 2004). This line of studies (e.g., Bickerstaff, 2004; Leiserowitz, 2006). 政 治 大 Instead, public perceptions of environmental risks are less determined by technical 立. argued that the public does not weight information carefully before making decisions.. rationality, but have more to do with trust, affects, and characteristics of the risks such. ‧ 國. 學. as dread and unknown.. ‧. Another line of research focused on demographic variables such as race, class,. sit. y. Nat. and gender, with a general conclusion that women, younger people, the socially. io. er. underprivileged, and the politically liberal are more sensitive to environmental risks (e.g., Biel & Nilsson, 2005; Carlisle & Smith, 2005; Dietz, Kalof, & Stern, 2002;. al. n. v i n Hunter, Hatch & Johnson, 2004;CXiao & McCright, 2007). h e n g c h i U However, the influences of these socio-structural variables are often found to be mediated after more underlying cognitive constructs are controlled for (e.g., Lerner, Gonzalez, Small, & Fischhoff, 2003). More recently, it is suggested that perception of environmental risks goes beyond temporary affective arousals experienced when risk judgments are made. Rather, it has something to do with what people believe and how they perceive the world, as these fundamental worldviews and values may function as perceptual filters of relevant risk information (Dietz, Fitzgerald & Shwom, 2005; Slimak & Dietz, 2006). As a consequence, the present study will argue within the value-basis tradition, 10.

(19) exploring how values may predict the subjective judgment that people make about the seriousness of environmental threats. Environmental Policy Support Definition Poortinga et al. (2004) defined policy support as the willingness to accept environmental measurements and regulations aimed at facilitating sustainable development. Although policy support does not directly influence the environment, it may have greater impact by significantly shaping the context in which policies and. 政 治 大. regulations are made (Poortinga et al., 2004).. 立. Predicting Environmental Policy Support. ‧ 國. 學. What makes a person more willing to support environmental policies and regulations against their own interests, and what refrains one from doing so? A. ‧. number of studies turn to cost and benefit analysis to explain public willingness to. sit. y. Nat. help protect the environment. These studies (e.g., Gardner & Abraham, 2010; Kaiser,. al. er. io. 2006; Montano & Kasprzyk, 2008; Oreg & Katz-Gerro, 2006) mainly draw on Ajzen. v. n. (1991)’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as their theoretical framework.. Ch. engchi. i n U. According to TPB, environmental behavioral intentions are best predicted by three conceptually independent determinants: (1) attitude toward the behavior (the general attitude toward a behavioral option based on the sum of the perceived positive and negative consequences through rational evaluations); (2) subjective norms (the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior); (3) behavioral control (the perceived ease and difficulty of performing the behavior due to past experience as well as anticipation of future impediments) (for recent reviews, see Armitage & Christian, 2003; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2005). Although studies of this line have provided some useful insight, it is suggested 11.

(20) that support for environmental protection has a moral dimension that cannot be fully explained without considering the role of values (Gärling, Fujii, Gärling, & Jakobsson, 2003). Scholars of this line believe that individuals can be motivated to act in favor of the environment even when external constraint exist or substantial material costs are involved , if such behavior will lead to outcomes they value. These value-basis studies often employed Stern et al. (1994)’s value-belief-norm theory (VBN) to explain how trans-situational values will have impact on people’s environmental attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Cordano et al., 2011; Jakovcevic & Steg, 2013; Jansson, Marell, &. 政 治 大 According to VBN, support for environmental protection constitutes 立. Nordlund, 2011; Menzel & Bögeholz, 2010).. norm-based behaviors which are determined by three factors: acceptance of particular. ‧ 國. 學. values, beliefs that things important to these values are under threat, and beliefs that. ‧. actions initiated by the individual can help alleviate the threat and restore the values. y. Nat. (for a review see Dietz, Fitzgerald, & Shwom, 2005). This thesis will argue in line. environmental risk perception and policy support.. n. al. Personal Values Definition. Ch. engchi. er. io. sit. with value-basis theories, exploring the role of values in influencing people’s. i n U. v. Schwartz (2006) defined values as trans-situational goals ordered by subjective importance that serve as guiding principles in life. This definition summarizes five common features identified in most of the definitions in the literature. According to this definition, values are (a) concepts or beliefs, (b) about desirable end states or behaviors, (c) that transcend specific situations, (d) guide selection or evaluation of behavior and events, and (e) are ordered by relative importance (Schwartz, 2006). Several models are proposed to systematically describe the content and 12.

(21) structure of universal human values (e.g. Rokeach, 1973). Rokeach (1973), for instance, classified human values into either modes of conducts (instrumental values) or end-states of existence (terminal values). Among them, Schwartz (1992, 1994)’s model of value dimensions will be used in this study as the categorizing structure, as it contains a value dimension that directly addresses the subjective importance of self-interests as opposed to group goals. Schwartz’s Model of Basic Human Values Schwartz (1994) summarized findings obtained from 97 samples in 44. 政 治 大 value types by their motivational 立 goals (achievement, hedonism, stimulation,. countries from all inhabited continents between 1988 and 1993 and identified ten. ‧ 國. 學. self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security). These values differ in the type of motivational goals they express: the more important a. ‧. value is to a person, the more this person is motivated to attain the goal it represents. sit. y. Nat. (Roccas & Sagiv, 2010) (see Table 1 for the details of Schwartz’s 10 value types).. n. al. er. io. Although importance attributed to different values may vary from person to. i n U. v. person, the structure is held to be similar across cultures (Schwartz & Bardi, 2001;. Ch. engchi. Sagiv & Schwartz, 2007). Figure 1 shows the schematic structure that portrays the pattern of relations among the ten basic values organized by motivational similarities and dissimilarities. The farther two values are, the more likely behaviors promoting one of the conflicting values will impede the attainment of the other (Schwartz, 2006).. 13.

(22) Table 1 Schwartz’s Model of Basic Human Values A world at peace Inner harmony. Power Social power Authority Wealth Preserving public image. Benevolence Helpful Honest Forgiving Loyal. Achievement Successful Capable Ambitious Influential Intelligence Self-respect. Responsibility True friendship A spiritual life Mature love Meaning in life. 政 治 大 Tradition. 立. Devout Accepting portion in life Humble. ‧ 國. 學. Hedonism Pleasure Enjoying life. Stimulation: Daring A varied life An exciting life. ‧. Moderate Respect for tradition Detachment. y. Nat. sit. Conformity Politeness Honoring parents and elders Obedient Self-discipline. n. al. er. io. Self-direction Creativity Curious Freedom Choosing own goals Independent. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Security Clean National security Social order Family security Reciprocation of favors Health Sense of belonging. Universalism Protecting the environment A world of beauty Unity with nature Broad-minded Social justice Wisdom Equality. Note. Adapted from “Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values,” by S. H. Schwartz, 1994, Journal of social issues, 50(4), p.33.. 14.

(23) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 1 Theoretical model of relations among Schwartz’s values.. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. The 10 motivationally distinct value types could be grouped into four higher. i n U. v. order value clusters organized as two bipolar dimensions. Reanalyses of the. Ch. engchi. individual-level data using confirmatory factor analysis (Schwartz & Boehnke, 2004) and multidimensional scaling (Fontaine, Poortinga, Delbeke, & Schwartz, 2008) support the theorized structure of 10 value types positioned along the two dimensions. Analyses with independent datasets also replicate the same structure (e.g., Perrinjaquet, Furrer, Usunier, Cestre, & Valette-Florence, 2007; Spini, 2003). The first dimension contrasts self-enhancement with self-transcendence. Self-enhancement emphasizes the pursuit of self-interest by focusing on one’s relative success (achievement) and domination over others (power). Self-transcendence, on the other hand, emphasizes concern and care for those with whom one has frequent 15.

(24) contact (benevolence) or for all human beings and all life forms regardless of group membership (universalism). On the other hand, the second dimension contrasts openness to change with conservatism. Openness to change emphasizes autonomy of thought and action (self-direction) and excitement (stimulation), whereas conservatism emphasizes commitment to past beliefs and customs (tradition), adherence to social norms and expectations (conformity), and preference for stability and safety (security). Hedonism shares elements of both openness and self-enhancement, and are in conflict. 政 治 大. with both self-transcendence and conservatism (Roccas & Sagiv, 2010; Schwartz, 2008).. 立. Given the specific research focus on conflicts between self-interests and care. ‧ 國. 學. for others, this thesis will limit its discussion to the roles of self-transcendence and. ‧. self-enhancement.. Nat. sit. y. Self-transcendence and Self-enhancement. al. er. io. There is much evidence suggesting that self-transcendence values increase. v. n. people’s perceived risks of environmental problems, making them more likely to. Ch. engchi. i n U. engage in environmentally protective behaviors. On the other hand, self-enhancement values were found to negatively influence public risk perception and proenvironmental intention (De Groot & Steg, 2008; Dietz et al., 2005; Lea & Worsley, 2005; Milfon et al., 2010; Nordlund & Garvill, 2002, 2003; Steg, & Vlek, 2009; Slimak & Dietz, 2006; Whitfield, 2009). For example, Beckmann et al. (1997) found in a cross-national study of Spain, Netherlands, and Denmark that individuals describing self-transcendence values as their primary life goals tend to judge environmental problems as more serious. On the other hand, self-enhancing individuals are less sensitive to environmental threats, 16.

(25) which makes them less willing to trade off personal benefits for environmental causes. In support, Slimak and Dietz (2006) noted that self-transcendence values directly increased the perceived seriousness of environmental problems and indirectly through shaping proenvironmental worldviews. Whitfield (2009) also found in a U.S. national sample that individuals emphasizing elf-transcendence individuals are more likely to report higher risk perception than those who view self-enhancement as their primary life goals. In addition to perceived seriousness of environmental problems,. 政 治 大 which people are willing to act in favor of the environment (De Groot & Steg, 2007; 立 self-transcendence and self-enhancement were also found to influence the degree to. Hansla, Gärling, & Biel, 2013; Nordlund & Garvill, 2002, 2003; Schultz, 2001;. ‧ 國. 學. Schultz & Zelezny, 2003; Stern & Dietz, 1994). Schultz and Zelezny (2003), for. ‧. instance, noted that individuals with self-transcendent values are more likely to. sit. y. Nat. engage in proenvironmental behavior, while those with self-enhancement values were. io. er. found to engage in fewer environmental behaviors. This connection holds across cultures (Schultz & Zelezny, 2003) and for a wide variety of environmental issues. al. n. v i n (Collins, Steg, & Koning, 2007;C Dietz, Dan, & Shwom, h e n g c h i U2007; Poortinga et al., 2011). The role of self-transcendence and self-enhancement in shaping risk. perception and influencing behavioral choices could be explained by the motivational goals behind (Schultz & Zelezny, 2003). Specifically, as self-transcendence comprises life goals that “promote the interests of other persons and the natural world,” people high on self-transcendence are more concerned with others and are prone to universalize their actions by considering the larger consequences beyond themselves. Consequently, self-transcendence values such as helping and responsible induce people to act in ways that benefit others even at some net cost to self (Schwartz, 1994b, p. 101). In contrast, since self-enhancement expresses life goals that “promote 17.

(26) one’s own interests regardless of others,” people high on self-enhancement orientation are induced to adopt a domination mentality, as they view the pursuit of self-interests as their primary concern and seek to further their own power and achievements (Schwartz, 1994b, p. 101). Schultz (2001, p. 336) proposed a similar explanation, linking self-transcendence and self-enhancement values with the concept of self. From this perspective, self-transcendence and self-enhancement values express a broad cognitive representation of the self, reflecting the extent to which individuals define. 政 治 大 inclusion, those high on self-transcendence tend to be more environmentally 立. themselves as part of nature. Since self-transcendence reflects higher levels of. concerned and engage in more environmental behavior. On the contrary, as. ‧ 國. 學. self-enhancement denotes the dominant perspective of the self over the non-self, those. ‧. subscribing to self-enhancement life goals are more likely to hold egoistic concerns. sit. y. Nat. about environmental issues and report lower willingness to help protect the. io. er. environment (also see Schultz et al., 2005).. Based on the literature, relations between values, risk perception, and policy. n. al. Ch. support are hypothesized as follows:. engchi. i n U. v. H1a: Self-transcendence values positively influence environmental risk perception. H1b: Self-enhancement values negatively influence environmental risk perception. H2a: Self-transcendence values positively influence environmental policy support. H2b: Self-enhancement values negatively influence environmental policy support. Risk Perception and Policy Support Empirical evidence suggested that perception of higher environmental risks increases public willingness to help protect the environment (Banerjee & McKeage, 1994; Beckmann et al., 1997; Eriksson, Garvill, & Nordlund, 2006; Laroche, 18.

(27) Bergeron, & Barbaro-Forleo, 2001; Nordlund & Garvill, 2003; Story & Forsyth, 2008). For instance, in a cross-national study of Spain, Denmark, and the Netherlands, Beckmann et al. (1997) found that individuals who perceive higher environmental threats are more willing to trade off personal benefits for environmental causes. Nordlund and Garvill (2002) also demonstrated that environmental risk perception will activate a personal norm that compels individuals to act in an environmentally responsible way. In a similar vein, Story and Forsyth (2008) argued that individuals. 政 治 大 threats and believe the danger posed by the threat to be great. Supporting this, 立. will be most likely to respond to environmental challenges when they are aware of the. Laroche et al. (2001) pointed out that green consumers are often those who believe. ‧ 國. 學. that the current environmental conditions are deteriorating and posing serious threat to. ‧. things they value. Conversely, consumers who show lower environmentally. y. Nat. responsible purchase intention tend to believe that environmental problems are not. er. io. sit. serious and will “resolve themselves.” These studies all pointed to an important conclusion that public risk perception of environmental hazards will influence their. n. al. Ch. willingness to make sacrifice for the environment.. engchi. i n U. v. Based on the above, one hypothesis regarding the relation between environmental risk perception and policy support is proposed:. H3: Environmental risk perception positively influences policy support. Geographical Scales of Environmental Risks As stated above, previous studies have demonstrated that citizens’ risk perception of environmental problems will influence whether or not they choose to act pro-environmentally (Steg & Sievers, 2000). However, for the most part, environmental risk perception has been predominantly studied at the local level 19.

(28) involving only people’s immediate surrounding (Gifford et al., 2009). Though largely ignored in the early risk perception literature, recent studies (Olli et al., 2001; Schultz et al., 2005; Uzzell, 2000) have suggested that geographical scales may play a crucial part in influencing public risk perception of and responses to environmental threats. Fairbrother (2012), for example, noted that local and global risk perception measure different aspects of broad environmental concern and are better treated as different cognitive constructs driven by different causal factors. Many scholars (e.g., Gifford et al., 2009; Lai, Brennan, Chan, & Tao, 2003) also called for future research on the. 政 治 大 Of a few studies that explored this phenomenon, evidence suggested that the 立. assessment of environment risks at different spatial scales.. public tend to perceive lower risks associated with their immediate environment. ‧ 國. 學. compared to their perception of geographically distant and broader dangers (Hatfield. ‧. et al., 2001; Pahl, Harris, Todd, & Rutter, 2005). The reason behind might be that. sit. y. Nat. discounting personally relevant risks can help reduce levels of anxiety (Schultz et al.,. io. er. 2012). Gifford et al. (2009) refers to this psychological tendency to discount local environmental problems and exaggerated global ones as “spatial optimism.” As one of. al. n. v i n Cthis a few early attempts looking into Musson (1974)’s study found that h ephenomenon, ngchi U people in the U.K. tended to believe their local areas were less affected by. overpopulation than the country as a whole (as cited in Gifford et al., 2009). Later studies confirmed such spatial bias, showing that perceived environmental risks increase, as the spatial level expands from local, national, and to global (Fornara, Bonnes, & Schultz, 2012; Schultz et al., 2012; Schultz et al., 2005; Uzzell, 2000). This tendency to underestimate the severity of environmental problems in one’s local community might prevent individuals from acting locally to help protect the environment (Gifford, 2011). Despite its potential significance, few studies have attempted to investigate 20.

(29) whether risk perception of global and local environmental hazards are driven by different sets of values and will arouse different patterns of responses. This study, hence, set out to address this gap.. Moderating Value-Perception Relations Past studies suggested that self-transcendence and self-enhancement differentially affect people’s risk ratings of environmental problems perceived at different spatial scales (Hansla, Gamble, Juliusson, Gärling, 2008; Schwartz, Bardi, Bianchi, 2000). Schwartz et al. (2000), for example, found that self-transcendence. 政 治 大. values deflect people’s attention away from local environmental hazards while. 立. increase their concerns for distant and broader hazards affecting the world as a whole.. ‧ 國. 學. In contrast, those who emphasize self-enhancement tend to perceive higher risks for hazards affecting their local community but express lower concerns over hazards. ‧. located at broader geographical scales. In a similar vein, Hansla et al. (2008) indicated. y. Nat. io. sit. that people with strong self-enhancement orientation are more sensitive to hazards. n. al. er. affecting themselves, while those committed to self-transcendence life goals are more. i n U. v. likely to believe that global environmental problems are posing serious threats to the world as a whole.. Ch. engchi. While self-enhancement decreases the perceived seriousness of distant and broad risks, self-transcendence values such as helping and protecting make people more sensitive to both global and local threats. Schultz and Zelezny (2003) explained that this is because self-transcendence induces people to care for others’ welfare, including those with whom they have frequent contact (benevolence) and all human beings regardless of group membership (universalism). As a consequence, the positive impact of self-transcendence values is expected to hold both for global and local environmental issues. Due to the lack of empirical evidence, a research question 21.

(30) rather than a hypothesis is proposed to delineate how values may influence distant and impending risk respectively:. RQ1: How does geographical scale influence relations between personal values and environmental risk perception?. Moderating Perception-Support Relations It is expected that perception of local threats specific to one’s community would be more effective in activating support for environmental protection compared. 政 治 大 problems are often those that 立people feel least responsible for and most powerless to to global risks affecting the world as a whole. For one thing, global environmental. ‧ 國. 學. influence (Gifford et al., 2009; Schultz et al., 2012; Uzzell, 2000). For another, rational citizens have stronger incentives to free ride on others’ contribution when the. ‧. issue at stake involves all humanity (Lubell, 2002).. sit. y. Nat. Recent studies provided initial evidence supporting stronger association. n. al. er. io. between local risk perception and people’s proenvironmental behaviors (e.g., Larock. i n U. v. & Baxter, 2013). For example, Hirsch and Baxter (2011) found that people are more. Ch. engchi. responsive to risks that are “situated” and “contextualized” in the immediate experiences of their everyday lives. Mouro and Castro (2010) also illustrated that attachment to local communities increases support for biodiversity conservation practices, especially for the high vested interest and in low trust conditions. Expanding on these findings, this thesis is interested in knowing whether the positive association between risk perception and behavioral support will be stronger when the issues involved are geographically closer to the individuals, as explored in RQ2:. RQ2: How does geographical scale influence relations between environmental risk 22.

(31) perception and policy support?. Country-level Influences It is suggested that people’s environmental attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are influenced in part by forces beyond their psychological attributes. Country-level characteristics also play some part (Johnson, Bowker, & Cordell, 2004; Lynch, 1993; Menzel & Bögeholz, 2010). Such contextual influences may exist above and beyond direct effects, since relations among person-level constructs are largely shaped by specific contexts in which they operate (Schwartz, 2008; Schwartz & Rubel-Lifschitz,. 政 治 大. 2009). Consequently, it is suggested that researchers need to consider contextual. 立. factors in studying public risk perception and policy support.. ‧ 國. 學. The influence of country-level factors was well evidenced in the literature. For example, Lai et al. (2003) found that Chinese people tend to judge environmental. ‧. hazards as more risky than those in Western cultures, because Chinese people are. y. Nat. io. sit. more sensitive to risk information than their Western counterparts. Kilbourne and. n. al. er. Polonsky (2005) also found that public environmental risk perception were closely. i n U. v. related to broader cultural contexts, illustrating that the primary elements of the. Ch. engchi. dominant social paradigm (DSP) specific to Western industrial societies (i.e., economic liberalism, technological optimism, and liberal democracy) significantly decreased the perceived seriousness of environmental problems, which in turn brought about less behavioral engagement. One dimension that distinguishes between cultures is the prevailing value orientations that members of a given society are exposed to and socialized to accept. Beyond cultural value orientations, each society’s development level is also progressively identified as an important country-level factor influencing how members of a society perceive and respond to environmental threats (e.g., Inglehart, 1995). As a consequence, the thesis will specifically focus on cultural 23.

(32) value orientation and development levels as potential sources of influence at the aggregate. Cultural Orientation Cultural value orientations represent shared abstract ideas about what is good, right, and desirable in a society (Roccas & Sagiv, 2010; Schwartz, 2008). They are broad goals that members of a society are encouraged to pursue (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2007). Compared to other aspects of a culture, cultural orientations are relatively stable, constitute the most central feature of a culture, and influence every aspect of. 政 治 大 Specific to the issue立 at stake, cultural value orientations are found to be one of. how we live (Hofstede, 2001; Schwartz, 2006).. ‧ 國. 學. the most important country-level determinants shaping each society’s distinct responses to environmental risks (Milfont et al., 2012). For example, Lynch (1993). ‧. noted that Latin Americans tend to view humans as “protectors or consumers of. sit. y. Nat. nature,” while Anglo environmentalism is characterized by a humans-in-nature. n. al. er. io. perspective, relying mainly on technical solutions to deal with human-nature relations.. i n U. v. This cultural differences explain why people in Latin American countries (e.g.,. Ch. engchi. Mexico, Peru, Brazil) express more concerns for environmental issues than the U.S. public (as well as Canadian, English, German, and Russian) (Noe & Snow, 1990). To compare value differences across cultures, several models have been proposed, suggesting dimensions by which countries can be positioned relative to each other. These models include Hofstede (2001)’s cultural dimensions, Inglehart (1995)’s postmaterialism theory, Douglas and Wildavsky (1982)’s cultural theory, and Schwartz (2006) cultural value theory. Although not conceptually related to environmental issues, these dimensions have all been successfully applied to environmental research. 24.

(33) Among these models, the present study will utilize Schwartz (2006)’s cultural dimensions as the categorizing instrument. The reasons are several. First, Schwartz suggested that value structure appropriate for comparing societies is different from that appropriate for comparing individuals. Instead, he proposed two separate value models, suggesting 10 motivationally distinct value types at the individual level, and seven cultural dimensions at the aggregate (Schwartz, 2008). This allowed for the simultaneous examination of different-level constructs as well as a potential cross-level interaction (Schiefer, 2013).. 政 治 大 dimensions based on Western-centered nations, Schwartz’s model is characterized by 立 Second, unlike previous models (e.g., Hofstede, 2001) that derived their. a more comprehensive data collection process (De Clercq, Fontaine, & Anseel, 2008;. ‧ 國. 學. Schwartz, 2006). Evidence suggested that, as it covers a fuller heterogeneity of. ‧. cultures and has the meaning equivalence cross-cultural controlled, major. sit. y. Nat. motivationally distinct values likely to be recognized across cultures are all included. io. er. (Fontaine, Poortinga, Delbeke, & Schwartz, 2008; Schwartz, 2006). In the next section, Schwartz’s cultural dimensions will be discussed in more detail.. n. al. Ch. a. Schwartz’s Cultural Dimensions. engchi. i n U. v. Schwartz proposed seven cultural orientations that form three bipolar dimensions expressing alternative solutions to basic social issues each society is confronted with when regulating human activities (Schwartz, 2006). The first dimension deals with the relations between individuals and the group, which distinguishes a cultural emphasis on embeddedness from autonomy (Schwartz, 2008). In highly embedded cultures, such as Malaysia, Georgia, and Nepal, individuals are expected to find meanings through social relations, to identify with the group goals, and to participate in its shared way of life. In contrast, in highly autonomous cultures, 25.

(34) such as Netherlands, Canada, and France, individuals are expected to cultivate their own preference, feelings, ideas, and abilities, and to find meanings in their own uniqueness (Milfont, 2012; Schwartz, 2006; Schiefer, 2013). The second dimension expresses each society’s preferred way to ensure socially productive behaviors in order to preserve stable social fabric. This dimension yields a cultural emphasis on hierarchy in contrast to egalitarianism. In hierarchical cultures such as China, India, and Zimbabwe, social fabric is preserved via power differences and role obligations, whereas in cultures emphasizing egalitarian. 政 治 大 voluntary cooperation and recognition of others as moral equals. As a consequence, 立 commitment, such as Finland, Italy, and Netherlands, social fabric is preserved via. hierarchical cultures view an unequal distribution of power and resources within. ‧ 國. 學. society as a natural and desirable condition, whereas egalitarian cultures promote the. ‧. internalized commitment to cooperate and act voluntarily for the welfare of others. sit. y. Nat. (Schwartz, 2006; Milfont, 2012).. io. er. The third dimension deals with the relation of humans to nature. This dimension distinguishes between a cultural preference to harmony and an emphasis. al. n. v i n on mastery. In harmony culturesC such as Slovenia andU h e n g c h i Estonia, individuals are induced to fit into the environment and to sustain a harmonious relation with nature, while in mastery cultures such as the United States and Japan, individuals are encouraged to exploit, change, and direct the world in order to attain personal goals (Schwartz, 2006; Milfont, 2012). Table 2 provides a description of the resulting cultural dimensions. The shared and opposing assumptions inherent in these cultural orientations yield a coherent circular structure of relations among them, as presented in Figure 2. The more compatible certain values are (the closer they are to each other in the circle), the more likely a cultural group will hold these values simultaneously. On the contrary, an emphasis on one value type will be accompanied by a de-emphasis on its polar 26.

(35) value. Schwartz’s model was not widely examined in environmental behavior research. Among the three bipolar dimensions, the most widely studied one is the mastery-harmony contrast, as it expresses each society’s distinct way to deal with human-nature relations. Milfont and Sibley (2012), for example, found that Schwartz’s harmony scores were positively related to country-level environmental performance. However, contradictory result was found in Oreg and Katz-Gerro (2006)’s cross-cultural study across 27 countries, which reported no significant role of. 政 治 大 point to the need for further research. 立. harmony in shaping perceived threats and proenvironmental intention. Mixed results. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 27. i n U. v.

(36) Table 2 Schwartz’s Model of Cultural Dimensions Dimensions. Description. Exemplary value. Countries. Conservatism. Cultural emphasis on maintenance of the status quo, and restraint of actions and inclinations that might disrupt the status quo or the traditional order. Social order, respect for tradition, family security. Nepal Malaysia Georgia. Intellectual Autonomy. Cultural emphasis on encouraging individuals’ pursuit of their own ideals and intellectual directions Cultural emphasis on encouraging individuals’ pursuit of affective positive experiences Cultural emphasis on the. Curiosity, Netherlands creativity, France broad-mindedness. Social power,. China. legitimacy of inequality in the distribution of power, roles, and resources Cultural emphasis on transcending selfish interests in favor of commitment to promoting the welfare of others Cultural emphasis on. authority, wealth. Zimbabwe India. Ambition,. United States. succeeding through active self-assertion Cultural emphasis on fitting harmoniously into the environment rather than on changing or exploiting it. success, daring. Japan. n. Mastery. Harmony. Ch. Greece New Zealand East Germany. y. sit. Equality, social justice, responsibility. er. io. al. ‧. Nat. Egalitarianism. 學. Hierarchy. 立. 政 治Pleasure, exciting 大 life, varied life. ‧ 國. Affective Autonomy. engchi. i n U. v. Finland Italy Netherlands. Unity with nature, Slovenia protecting the Estonia environment, Czech Republic world of peace. Note. Adapted from “Cultural differences in environmental engagement” in The Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology (p.186), by T. L. Milfont, 2012, Oxford University Press.. 28.

(37) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. Figure 2 Schwartz’s cultural dimensions: Prototypical structure.. Ch. engchi. b. Self-oriented and Other-oriented Cultures. i n U. v. According to Schwartz, egalitarian and harmony dimensions share a broad concern for self-transcendence (Schwartz, 1994b, p. 96), while hierarchy and mastery can be subsumed under the category of self-enhancement (Schwartz, 1994b, p.106). With the specific research goal, the present study will focus on one cultural dimension that contrasts self-oriented cultures with other-oriented ones. The degree to which a given society stresses altruistic concerns over self-interests were measured by summing up Schwartz’s nation scores for egalitarian and harmony, with higher scores expressing collective emphases on other-oriented values. The use of a scale can avoid 29.

(38) the concern for multicollinearity (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Development Levels a. Inglehart’s Theory: Mixed Results Years of empirical studies have shown that levels of development play an important role in shaping environmental concerns and behaviors of citizens across countries. Many cross-cultural studies also provided evidence that development levels correlate with a number of individual psychological constructs (e.g. Leung & Bond, 2004), suggesting the need to consider stages of development as potential influences. 政 治 大 A majority of environmental psychology studies exploring the impact of social 立. the aggregate.. development turned to Inglehart’s postmaterialism theory (1995) as their theoretical. ‧ 國. 學. basis. The theory posits that environmental concerns are expressions of a general. ‧. value shift process that takes place when a society develops from an industrial to. sit. y. Nat. postindustrial one. The rationale is that as societies become more developed, their. io. er. members are less pre-occupied with economic struggles for survival and are free to pursue what Inglehart termed post-materialistic goals, such as political freedom,. n. al. Ch. self-fulfillment, and environmental protection.. engchi. i n U. v. From the start, the emergence of postmaterialist values is associated with levels of social development. Specifically, postmaterialist values in general, or environmental concerns in particular, are far likelier to be found among the publics of highly developed societies than in less developed countries (Abramson & Inglehart 1994). That is, people in more developed countries are more likely to feel concerned about the conditions of the environment than those in less developed ones. This positive impact of social development has been supported in a number of studies (e.g., Franzen, 2003). For example, Franzen (2003)’s cross-cultural analysis revealed that support for environmental protection strongly correlated with national 30.

(39) economic conditions. Specifically, citizens in wealthier nations were found to express higher concerns for the environmental than those in poorer countries. However, contradictory evidence was also found elsewhere, suggesting that environmental concern is a global phenomenon independent of social development (Brechin & Kempton, 1994; Grendstad & Selle, 1997; Kemmelmeier et al., 2002; Davis, 2000). Dunlap and Mertig (1995) even found overall national wealth to be negatively rather than positively related to concerns for environmental quality. In response to these mixed findings, Inglehart (1995) later proposed an. 政 治 大 public support for environmental protection could occur in countries with severe 立. alternative “subjective feelings and objective problems hypothesis,” suggesting that. objective problems, even in the absence of postmaterialist values. Using cross-cultural. ‧ 國. 學. data from the World Values Survey, he confirmed that the greatest support for. ‧. environmental protection could be found in countries with the most severe. sit. y. Nat. environmental problems and with the strongest postmaterialist values (Inglehart,. io. er. 1995). In other words, two independent causes of environmental concerns were proposed, first the widespread of postmaterialist values that accompany social. al. n. v i n C h to concrete andUimmediate environmental development, and second, the exposure engchi. problems that threaten individuals’ health, properties, or even survival. Public support for environmental protection, therefore, might not be “a luxury” that could only be found in economically better-off societies. Rather, as citizens of more developed countries take on proenvironmental attitudes in the process of a general value shift, the public in less developed ones also display great concerns for a number of concrete and pressing local threats. What drives their concerns, however, might not be those broad and remote risks perceivable only at the abstract, but were more likely to be local threats that they are directly exposed to, such as air pollution, lack of access to clean water, and soil degradation in their community. These two independent causes 31.

(40) of environmental concerns suggested the need to distinguish between global and local environmental threats when considering the impact of social development. b. Development Levels and Geographical Scales According to Inglehart (1995)’s “subjective feelings and objective problems hypothesis,” in less-developed countries, public environmental concerns are driven by exposure to some pressing and concrete local environmental threats. On the contrary, citizens in more developed countries express environmental concerns as a consequence of a general postmaterialist mindset. This is because as societies become. 政 治 大 less developed counterparts, 立which tend to strive for economic advances even at the. more developed, they are more likely to be free from environmental hazards than their. ‧ 國. 學. cost of the environment. With a presumably better living environment, public environmental attitudes and behaviors in more developed countries are less likely to. ‧. be formed in response to concrete environmental threats that directly affect them. As a. sit. y. Nat. consequence, development levels may increase concerns for broader and distant. al. er. io. environmental problems but decrease concerns for local and close-to-home threats.. v. n. Franzen and Meyer (2010)’s study also provided evidence that social. Ch. engchi. i n U. development levels do not have consistent effects when different environmental issues are under discussion. Specifically, their study showed that only with respect to global environmental issues, such as carbon dioxide emissions, does public willingness to pay for the environment increase with development levels. For close-to-home hazards that one experiences in their local community, an inverted U-shaped relation was proposed instead. Numerous studies (e.g., Ehrhardt-Martinez, Crenshaw & Jenkins, 2002; Antweiler, Copeland & Taylor, 2001) lent support to this “environmental Kuznets curve”, showing that public willingness to pay for the environment increases as pollution becomes more serious due to economic development. However, as 32.

(41) pollution becomes less serious with more regulations and controls, the public show lower willingness to pay extra than they currently do. Such “environmental Kuznets curve” only takes place for local environmental issues such as regional air and water pollution (Khanna & Plassmann 2004; York, Rosa & Dietz, 2003; Smith & Ezzati, 2005). In support, Gökşen et al. (2002) suggested that citizens of countries at different stages of development may pay selective attention to local and global issues respectively due to their value priority variance. Their study found that the public in. 政 治 大 concerned about local environmental problems. In contrast, those from more 立. less developed countries tend to endorse materialist concerns, which make them more. developed countries, with a strong postmaterialist mindset, are willing to pay for both. ‧ 國. 學. global and local environmental problems. Given the above, two research questions are. ‧. proposed:. y. Nat. er. io. sit. RQ3: How do cultural orientation and development levels influence people’s environmental risk perception? Does this pattern of association vary with. n. al. Ch. geographical scales of the risks?. engchi. i n U. v. RQ4: How do cultural orientation and development levels influence people’s environmental policy support? Country-level Characteristics as Moderators Prior environmental research exploring the aggregate influences has predominantly focused on their main effects (e.g. Cordano et al., 2010; Mukherjee & Chakraborty, 2010; Oreg & Katz-Gerro, 2006). For example, Mukherjee and Mukherjee and Chakraborty (2010)’s study found that environmental sustainability 33.

數據

Outline

相關文件

在南京條約的政治方面,在 條約割讓香港會令中國政治 影響力下降,因為英國在華 的勢力坐大,中國慢慢失去

Examples of relevant concepts: equality, discrimination, cultural differences, community resources, self-concept, vulnerable groups, community work, community support

Examples of relevant concepts: equality, discrimination, cultural differences, community resources, self-concept, vulnerable groups, community work, community support

• Empower and up-skill others – encourage greater responsibility for own development at all levels through coaching, support creativity, risk. taking

The results revealed that (1) social context, self-perception, school engagement, and academic achievement were antecedents of dropping out; (2) students’ self-factor was a

因此在表 5-4 評估次項目中,統計結果顯示政治穩定度、房產政 策、官僚政治以及景氣是接受度最高的,可以顯示政局安定以及當局

本研究採用的方法是將階層式與非階層式集群法結合。第一步先運用

Theory Z’( Maslow,1971) , 在 生理、安全、愛、自尊、自我實現之 上,有一最高的需求層次,就是個人 靈性成長 (Spiritual Growth) 或自 我超越 (Self Transcendence)