www.elsevier.com / locate / ijcard

Arterial blood pressure and blood lipids as cardiovascular risk factors and

occupational stress in Taiwan

a ,

*

b c dChien-Tien Su

, Hung-Jen Yang , Chin-Feng Lin , Ming-Chuan Tsai ,

e c

Ying-Hua Shieh , Wen-Ta Chiu

a

School of Public Health, Taipei Medical University, 250 Wu-Hsing St., Taipei, 110 Taiwan b

Department of Internal Medicine, Min-Sheng Healthcare, Taoyuan, 330 Taiwan c

Department of Occupational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Wan-Fang Hospital, Taipei, 116 Taiwan d

School of Medical Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, 110 Taiwan e

Department of Family Medicine, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei, 110 Taiwan

Received 4 January 2001; received in revised form 15 August 2001; accepted 7 September 2001

Abstract

Background: This study is to determine whether occupational stress (defined as high psychological demands and low decision latitude on the job) is associated with increased blood pressure and abnormal level of blood lipids as cardiovascular risk factors. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study at three work sites of 526 white-collar male workers aged 20 to 66 years without evidence of cardiovascular disease. Systolic, diastolic blood pressure, serum total, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and plasma triglyceride were measured. Occupational stress index was derived from data collected in the job strain questionnaire. Results: In multiple linear regression models, occupational stress index was significantly related to diastolic blood pressure and plasma triglyceride, after adjusting for age, education, smoking, and alcohol consumption. A higher occupational stress index was directly associated with higher systolic, diastolic blood pressure and higher level of plasma triglyceride. Conclusions: These data from a white-collar working population confirm independent relations between occupational stress defined in the job demand–control model and diastolic blood pressure observed in predominantly Western populations and extend the range of associations to plasma triglyceride than do previous studies. 2001 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Blood pressure; Triglyceride; Occupational stress; Job strain

1. Introduction able attention. Occupational stress, in Karasek’s job

strain model, is characterized by the work environ-The importance of behavioral and psychosocial ment and the extent to which it may allow individuals factors is increasingly recognized in the prevention, to modify the stress response [4,5]. The concept holds development, and treatment of cardiovascular dis- that stress caused by an imbalance between demands eases (CVD) [1]. Mental stress is considered one of on a worker and the worker’s ability to modify those these factors [2,3]. The role of occupational stress in demands. Low decision-making control coupled with the etiology of CVD has recently received consider- high job demands leads to high strain or to a stressful situation. High demands and low control work syner-gistically to have more impact than either factor

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 1886-2-2736-1661; fax:

1886-2-2738-alone. Workers reporting high levels of occupational 4831.

E-mail address: ctsu@tmu.edu.tw (C.-T. Su). stress were found to have elevated risks of

psycho-0167-5273 / 01 / $ – see front matter 2001 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. P I I : S 0 1 6 7 - 5 2 7 3 ( 0 1 ) 0 0 5 6 5 - 4

logical distress, psychosomatic and physical health comparison, there were no differences between study

complaints [6–10]. subjects and subjects excluded due to missing data in

The cardiovascular health consequences of occupa- age, education, smoking, alcohol consumption, blood tional stress are well documented in Western popula- pressure, blood lipids and occupational stress index. tions: individuals with high occupational stress are at

increased risk of smoking [11–13], hypertension [13–

15], CVD and its risk factors [16]. However, it 2.2. Cardiovascular risk factors remains unclear whether the relations between

occu-pational stress and cardiovascular risk factors ob- After overnight fasting, blood specimens were served among individuals in Western work culture collected by venous puncture and handled according also apply to individuals in East Asian work culture. to prevailing clinical practice for analysis of serum Hence, data from working populations in East Asian total, HDL cholesterol, and plasma triglyceride in the countries can be informative. Unfortunately, scant company clinics. Immediately after specimen collec-data are available on the association between job tion, vials were stored under appropriate conditions, strain and cardiovascular risk factors in East Asian refrigerated (4–88C), or frozen (2208C) until they countries. We therefore examined the relation of were shipped to a single analytical laboratory for occupational stress to systolic, diastolic blood pres- testing.

sure, serum total, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) Blood pressure measurements were obtained by cholesterol and plasma triglyceride using data from a trained nurses after subjects had been seated for 10 cross-sectional survey of a male white-collar working min by using a mercury manometer and appropriately

population in Taiwan. sized cuffs according to standard protocols. Triplicate

measurements on the same arm were taken, with at least 30 s between readings. Each subject’s systolic

2. Materials and methods and diastolic blood pressures were calculated as the

mean of the three independent measures.

2.1. Subjects

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Taipei 2.3. Occupational stress indicators City, Taiwan. All white-collar male workers

em-ployed in three private insurance companies were A self-administered occupational stress ques-invited to participate. Almost all of the workers were tionnaire embedded with the Karasek job strain professionals, technicians, managerial or clerical model and its measures was used to measure work-workers. Recruitment of participants was performed ers’ perception of job strain, psychological demands through announcements in the internal newsletters and decision latitude. Psychological demands were and a personalized e-mail of invitation to each measured by a five-item scale including quantity of worker. A total of 684 white-collar male workers work, quality of work intellectual requirements, aged 20 to 66 with more than 40 working hours per conflicting demands, and time constraints. Decision week were invited. Non-respondents were contacted latitude was measured by an eight-item scale includ-by telephone calls. Among the recruited, those with ing skill discretion factors: learning new things, skill clinical hypertension (n545) or taking medication for development, skill requirement, task variety, repeti-CVD (n518), which may lead to modification of tion, creativity requirement and decision authority regular health behaviors were excluded from the factors: freedom of making decisions, choice of ways study. Missing data on systolic, diastolic blood to perform work. All questions were scored on a pressure, serum total, HDL cholesterol or plasma Likert scale of 1 to 5. Scale reliability was acceptable triglyceride profiles (n512) or on the occupational for decision latitude (Cronbach’sa50.80), and

psy-stress index (n58) were also excluded. The study chological demands (Cronbach’s a50.76).

Occupa-sample was comprised of 526 male white-collar tional stress index was defined as a ratio of psycho-workers. The overall participation rate was 77%. In logical demands score to decision latitude score.

Table 1

2.4. Sociodemographic information and

health-Characteristics of study sample related behaviors

N5526

Percentage Data of sociodemographic information, and

health-Sociodemographic data and health-related behaviors

related behaviors were collected during interviews. Smoker 29.5

These variables were used as confounders to control Drinking alcohol 39.4 Education illiterate or elementary school 1.3 for potential confounding. Demographic variables

high school 20.6

included education and age at examination. The

college or above 78.1

health-related behaviors included current smoking

and alcohol consumption. Weight and height were Mean (S.D.)

Age (years) 48.25 (11.56)

measured during a physical examination before blood 2

Body mass index (kg / m ) 28.24 (5.69) specimen collection. The body mass index (BMI)

was calculated from weight and height using the

2 Table 2 equation: body mass index5weight (kg) / height (m) .

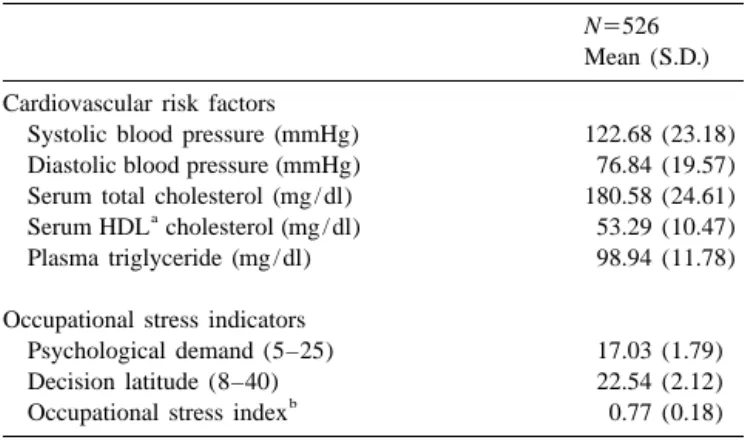

Mean values of cardiovascular risk factors and occupational stress indicators

2.5. Statistical analysis N5526

Mean (S.D.) Descriptive statistics including means, standard Cardiovascular risk factors

deviations, and percentages were used to summarize Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 122.68 (23.18) Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 76.84 (19.57) the cardiovascular risk factors, occupational stress

Serum total cholesterol (mg / dl) 180.58 (24.61) indicators, sociodemographic information and health- a

Serum HDL cholesterol (mg / dl) 53.29 (10.47) related behaviors of the study sample. Plasma triglyceride (mg / dl) 98.94 (11.78)

Multivariate linear regression was used in our

Occupational stress indicators study to examine the relations between occupational

Psychological demand (5–25) 17.03 (1.79) stress index and cardiovascular risk factors, simul- Decision latitude (8–40) 22.54 (2.12)

b

Occupational stress index 0.77 (0.18) taneously controlling for age, education, current

a

smoking, and alcohol consumption. In separate HDL, high density lipoprotein. b

Occupational stress index, ratio of psychological demand to decision models, we used systolic, diastolic blood pressure,

latitude. serum total, HDL cholesterol and plasma triglyceride

as dependent variables. In analyses treating

occupa-errors from separate regression models predicting tional stress index as a categorical variable, average

systolic, diastolic blood pressure, plasma triglyceride, differences were calculated in systolic, diastolic

serum total and HDL cholesterol. In all these models, blood pressure, serum total, HDL cholesterol and

occupational stress index was treated as a continuous plasma triglyceride and their 95% confidence

inter-variable. After adjusting for age, education, BMI, vals. The significance level for all statistical analyses

was set at a probability of less than 0.05 (two-tailed

Table 3 test). All data in this study were analyzed by the

Regression coefficients for cardiovascular risk factors by occupational Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 10.0

stress index (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Dependent variables Beta S.E.

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 8.21 0.79 Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 17.32* 3.42

3. Results Serum total cholesterol (mg / dl) 22.14 1.56

Serum HDL cholesterol (mg / dl) 6.37 1.44 Plasma triglyceride (mg / dl) 18.61* 3.31 Characteristics of the study population are

pre-*P,0.05. sented in Table 1. Table 2 presents the mean values

Age, education, BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption were adjusted and standard deviation of cardiovascular risk factors

for using multiple linear regression.

and occupational stress indicators of the study sam- Beta, regression coefficient for the occupational stress index; S.E., ple. Table 3 shows parameter estimates and standard standard error; HDL, high density lipoprotein.

Table 4

Estimated average differences in means and 95% confidence intervals for cardiovascular risk factors by occupational stress index Quartiles of occupational stress index (median value)

1 2 3 4

(0.46) (0.68) (0.84) (0.93)

Average 95% CI Average 95% CI Average 95% CI

difference difference difference

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 0 (ref) 3.42 1.34, 5.12 7.63 6.57, 8.94 10.21 8.83, 12.75 Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 0 6.84 4.54, 8.11 10.79 8.22, 13.54 17.97 14.95, 19.62 Serum total cholesterol (mg / dl) 0 8.35 4.18, 10.75 6.25 4.09, 9.98 9.12 6.77, 12.15 Serum HDL cholesterol (mg / dl) 0 1.51 0.46, 3.57 23.17 26.67, 22.11 6.94 4.36, 8.86 Plasma triglyceride (mg / dl) 0 6.93 4.43, 8.15 11.73 7.89, 14.13 13.06 8.73, 16.25

Age, education, body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption were adjusted for using multiple linear regression. CI, confidence interval; HDL, high density lipoprotein.

smoking, and alcohol consumption, occupational index and diastolic blood pressure and plasma tri-stress index was found to significantly predict dias- glyceride. No significant association between occupa-tolic blood pressure. Occupational stress index was tional stress index and systolic blood pressure, serum also positively and significantly associated with plas- total or HDL cholesterol was detectable in our study ma triglyceride level. In the models predicting sample.

systolic blood pressure and serum total cholesterol, The observed association is supported by the occupational stress index had positive regression stress–response pathophysiologic link. Stress re-coefficients, indicating that higher occupational stress sponse involves two neuroendocrine systems — the index might be associated with increased levels of sympathoadrenal medullary system, which secretes these two factors. However, none of the regression the catecholamines: adrenalin, and noradrenalin, and coefficients reached statistical significance. Table 4 the pituitary–adrenal cortical system, which secretes presents the average differences in means and 95% corticosteroids such as cortisol. Under demanding confidence intervals for systolic blood pressure, dias- conditions where the organism can exert control in tolic blood pressure, serum total, HDL cholesterol the face of controllable and predictable stressors, and plasma triglyceride across quartiles of occupa- adrenalin level increases, but cortisol decreases [17– tional stress index after adjusting for all confounders 19]. In low demand–low control situations, cortisol of interest. Compared with the lowest quartile of elevates, although catecholamines elevate only mildly occupational stress index (median value50.46), the [17]. However, in demanding low control situations value of systolic, diastolic blood pressure and plasma (analogous to the increase of occupational stress triglyceride increased monotonically with increasing index in our study), both adrenalin and cortisol are levels of occupational stress index. A higher occupa- elevated [17–19]. Elevated levels of both catechol-tional stress index was directly associated with higher amines and cortisol appear to have severe conse-systolic, diastolic blood pressure and higher level of quences for myocardiac pathology [20]. The effect of

plasma triglyceride. high occupational stress status on the well-established

cardiovascular risk factors may explain, at least in part, the association between occupational stress and

4. Discussion increased cardiovascular disease risk observed in a

number of previous studies [8,21–29].

These cross-sectional analyses of the data from a This study has several strengths. Firstly, it is sample representative for the white-collar male work- conducted in a representative sample of white-collar ing population in Taiwan support the existence of male workers. The response rate was reasonably high significant relations between occupational stress and (77%), which therefore limited the potential of cardiovascular risk factors. We observed significant selection bias. Participants having conditions that and positive associations between occupational stress could lead to modification of health behaviors were

excluded, which limited the potential of information The degree of increase in diastolic blood pressure bias. Secondly, statistical analyses were performed associated with occupational stress among white-col-with adjustment for a number of potential confoun- lar male workers in our study is similar to that ders. Confounders such as age, educational attain- observed in previous studies in Western countries ment, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and [16]. The underlying psychophysiological mecha-body mass index were included, which limited con- nisms of the association between occupational stress

founding bias. and blood pressure might be common between

West-It also needs to be kept in mind that this study may ern countries and Taiwan, suggesting the involvement be subject to several limitations. The observed as- of a biological response or basic cognitive process sociation between occupational stress index and rather than a culture-dependent response.

diastolic blood pressure and plasma triglyceride Our study did not support previous findings of a generally supports the existence of possible pathways relation between occupational stress and systolic that link occupational stress to cardiovascular dis- blood pressure [13,34]. However, our result is con-eases. However, differences in genetic predisposition sistent with an Australian baseline study [35] and a for variations in diastolic blood pressure and plasma study done among employed Danish workers [36]. As triglyceride could not be taken into account. The Chapman et al. pointed out in a prospective study on cross-sectional design could result in information bias perceived work stress and blood pressure change and selection bias, which could lead to either over- or [14], the cross-sectional design may be responsible underestimation of the true association. Lack of for the lack of support to the hypothesis. Another evaluation of the effect of occupational stress dura- reason for the negative or weak findings could be the tion due to cross-sectional data used could lead to an utilization of casual measures of blood pressure underestimation of the true association. The use of a conducted away from the work, which may be less self-administered questionnaire to measure occupa- reliable and less relevant than ambulatory measures. tional stress may be subject to response bias. How- Occupational stress where the level of job demands ever, no reliable objective measurement of occupa- exceeds the individual’s ability to control or deal with tional stress was available. Perceptual measure of those demands creates a challenge that activates the occupational stress may be a better indicator than sympathetic nervous system and leads to an elevation some external stressors that might not be perceived or of blood pressure at work. Long-term exposure to felt like stressors by workers. Objective formulation occupational stress ultimately results in a sustained of the questionnaire used in this study is also an elevation of blood pressure that then causes structural

appropriate way. and functional damage in the cardiovascular system.

In our study, diastolic blood pressure was associ- To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time ated with occupational stress. This is consistent with occupational stress has been found to be related to previous studies with similar measures of occupation- plasma triglyceride. This finding requires replication al stress [15,30]. Other studies of the association in other designs and settings to establish its validity. between occupational stress and diastolic blood pres- The exact role of hypertriglyceridemia as a risk factor sure have produced mixed findings. Negative results for cardiovascular disease remains elusive [37]. Al-were reported for Israeli workers and the Framin- though high plasma triglyceride levels are generally gham study, although in the Framingham study, predictive of cardiovascular risk, multivariate adjust-female clerical workers, who are likely to have high ment for other risk factors weakens this association stress, had higher rates of coronary heart disease [38,39]. Furthermore, significant individual variation [31,32]. On the other hand, the Air Traffic Control- exists in plasma triglyceride levels, which probably lers study reported higher prevalence of hypertension leads to substantial bias [40].

in workers in high-traffic density situations, who are We failed to show an association between occupa-usually under high stress [33]. The negative finding tional stress, serum total and HDL cholesterol. Previ-may be due to lack of statistical power associated ous studies in Western countries have reported no with the use of a proxy measure for occupational significant effect of occupational stress on serum total

occupa-[8] Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and tional stress on serum total and HDL cholesterol

cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample might be less clear than that on blood pressure. of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health

It is also noteworthy that the results cannot be 1988;78:1136–42.

[9] Astrand NE, Hanson BS, Isacson SO. Job demand, job decision over-generalized. Our sample was small and was not

latitude, job support, and social network factors as predictors of representative of the general population. The

differ-mortality in a Swedish pulp and paper company. Br J Ind Med ences of means were small and some associations 1989;46:334–40.

[10] Bourbonnais R, Brisson C, Moisan J. Job strain and psychological may have appeared by chance in our analyses. Not

distress in white-collar workers. Scand J Work Environ Health many cohort studies so far have evaluated the relation

1996;22:139–45.

between occupational stress and cardiovascular risk [11] Green KL, Johnson JV. The effects of psychosocial work organiza-factors and even fewer among East Asian popula- tion on patterns of cigarette smoking among male chemical plant

employees. Am J Public Health 1990;80:1368–71. tions. Further data will be collected on a longitudinal

[12] Mensch BS, Kandel DB. Do job conditions influence the use of basis for this study sample of white-collar male

drugs? J Health Soc Behav 1988;29:169–84.

workers to evaluate the long-term effect of occupa- [13] Pieper C, Lacroix AZ, Karasek RA. The relation of psychosocial dimensions of work with coronary disease risk factors: a meta-tional stress exposure.

analysis of five United States data bases. Am J Epidemiol In conclusion, this study suggests that occupational

1989;129:483–94.

stress index is associated with diastolic blood pres- [14] Chapman A, Mandry JA, Frommer MS, Edye BV, Ferguson DA. sure and plasma triglyceride which may explain the Chronic perceived work stress and blood pressure among Australian government employees. Scand J Work Environ Health 1990;16:258– link between occupational stress and increased

car-69.

diovascular disease risk. [15] Matthews KA, Cottingen EN, Talbott E, Kuller LH, Siegl Jm. Stressful work conditions and diastolic blood pressure among blue collar factory workers. Am J Epidemiol 1987;126:280–91. [16] Schnall PL, Landsbergis PA, Baker D. Job strain and cardiovascular

disease. Annu Rev Public Health 1994;15:381–411.

Acknowledgements

[17] Frankenhauser M. A biopsychosocial approach to work life issues. Int J Health Serv 1989;19:747–58.

Supported in part by grant 85-D-134 from Taipei [18] Frankenhauser M, Johansson G. Stress at work: psychobiological and psychosocial aspects. Int Rev Appl Psychol 1987;42:539–55. Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan. The authors

[19] Karasek RA, Russell RS, Theorell T. Physiology of stress and acknowledge the assistance and support of the staff in

regeneration in job related cardiovascular illness. J Hum Stress

the three companies involved. 1982;8:29–42.

[20] Steptoe A. Neural and endocrine factors in cardiovascular control. In: Psychological factors in cardiovascular disorders, London: Academic, 1981, pp. 17–38.

[21] Haan M. Job strain and cardiovascular disease. A ten-year

prospec-References

tive study. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:532–40.

[22] Johnson JV, Hall EM, Theorell T. Combined effects of job strain and [1] US Department of Health and Human Services. National Heart, social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in Lung, and Blood Institute Report of the Task Force on Behavioral a random sample of the Swedish mail working population. Scand J Research in Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Health and Disease, Work Environ Health 1989;15:271–9.

1998, Available at: http: / / www.nhlbi.nih.gov / resources / docs / tas- [23] Alfredsson L, Theorell T. Job characteristics of occupations and kforc.htm. Accessed March 1, 2000. myocardial infarction risk effects of possible confounding factors. [2] Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological Soc Sci Med 1983;17:1497–503.

factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implica- [24] Karasek RA, Baker D, Marxer F, Ahlbom A, Theorell T. Job tions for therapy. Circulation 1999;16:2192–217. decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a pros-[3] Bjorntorp P. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Acta Physiol Scand pective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health 1981;71:694–

Suppl 1997;640:144–8. 705.

[4] Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: [25] Karasek RA, Theorell T, Schwartz J, Schnall P, Pieper P, Michela J. implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–308. Job characteristics in relation to the prevalence of myocardial [5] Karasek RA, Theorell T. Healthy work: stress, productivity, and the infarction in the US HES and US HANES. Am J Public Health

reconstruction of working life, New York: Basic Books, 1990. 1988;78:910–8.

[6] Jonge J, Bosma H, Peter R, Siegrist J. Job strain, effort–reward [26] Schwartz J, Pieper C, Karasek RA. A procedure for linking job imbalance and employee well-being: a large-scale cross-sectional characteristics to health surveys. Am J Public Health 1988;78:904– study. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1317–27. 9.

[7] Falk A, Hanson BS, Isacsson SO, Ostergren PO. Job strain and [27] Reed DM, La Croix AZ, Karasek RA, Miller D, McLean CA. mortality in elderly men: social network, support, and influence as Occupational strain and the incidence of coronary heart disease. Am buffer. Am J Public Health 1992;82:1136–9. J Epidemiol 1989;129:495–502.

[28] Mollar L, Kristensen TS, Hollnagel H. Social class and cardiovascu- [36] Netterstrom B, Kristensen TS, Damsgaad MT, Olsen O, Sjol A. Job lar risk factors in Danish men. Scand J Soc Med 1991;19:116–26. strain and cardiovascular risk factors. A cross-sectional study of [29] Alterman T, Shekelle RB, Vernon SW, Burau KD. Decision latitude, employed Danish men and women. Br J Ind Med 1991;48:684–9.

psychological demand, job strain, and coronary heart disease in the [37] NIH Consensus Conference. Triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein, Western Electric study. Am J Epidemiol 1994;139:620–7. and coronary heart disease. NIH Consensus Development Panel on [30] Schnall PL, Pieper C, Schwartz JE et al. The relationship between Triglyceride, High-Density Lipoprotein, and Coronary Heart

Dis-job strain, workplace diastolic blood pressure, and left ventricular ease. J Am Med Assoc 1993;269:505–10.

mass index. J Am Med Assoc 1990;263:1929–35. [38] Pasternak RC, Grundy SM, Levy D, Thompson PD. 27th Bethesda [31] Shiorm A, Eden D, Silberwasser S, Kellermann JJ. Job stresses and Conference. Mating the intensity of risk factor management with the risk factors in coronary heart diseases among five occupational hazard for coronary disease events. Task Force 3. Spectrum of risk categories in kibbutzim. Soc Sci Med 1973;7:875–92. factors for coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:978– [32] Haynes S, Feinleid M. Women, work, and coronary heart disease. 90.

Findings from the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Public Health [39] LaRosa JC. Triglycerides and coronary risk in women and the 1980;70:133–41. elderly. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:961–8.

[33] Cobb S, Rose RM. Hypertension, peptic ulcer, and diabetes in air [40] Brenner H, Heiss G. The intraindividual variability of fasting traffic controllers. J Am Med Assoc 1989;224:489–92. triglyceride — a challenge for further standardization. Eur Heart J [34] Theorell T, Perski A, Akerstedt T et al. Changes in job strain in 1990;11:1054–8.

relation to changes in physiological state. A longitudinal study. Scand J Work Environ Health 1988;14:189–98.

[35] Frommer MS, Edye BV, Mandryk JA, Grammeno GG, Berry G, Ferguson DA. Systolic blood pressure in relation to occupation and perceived work stress. Scand J Work Environ Health 1986;12:476– 85.