Article

Promises and Pitfalls of Using National

Bioethics Commissions as an Institution to

Facilitate Deliberative Democracy—Lessons

from the Policy Making of Human Embryonic

Stem Cell Research

*Wenmay Rei

**& Jiunn-Rong Yeh

***ABSTRACT

Rarely has any scientific development stirred more public controversies than recent researches that make use of human embryos to harvest stem cells or clone another person. Facing these issues, policy-makers worldwide have been seeking counsels from national bioethics commissions of all varieties. By “national bioethics commissions,” this paper refers to commissions set up to advise government policy-makers on bioethics-related public policy, such as U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics, National Ethics Council of Germany, and Human Genetic Commission of the United Kingdom.

This article sees these national bioethics commissions as an opportunity to serve as an institution that can help realize the ideal condition for policy-making advocated in theories of deliberative democracy. Nevertheless, given the highly political nature of the issues, and national commissions’ vulnerability to be

*** Research of this paper is supported by research grant from National Science Council of

Taiwan “Law and Ethics of Biomedical Research in the Post-Genomic Era: Rethinking Research Subjects’ Rights Toward Their Body and Tissue Samples” (NSC 97-3112-H-010-002). It is a substantial revision of a series of paper which has been presented at the conference of “Bioethics Across Borders” jointly held by American Society for Bioethics and Humanities & Canadian Bioethics Society, October 22-26, 2003, Montreal, QC, Canada, and the IV Asian Conference of Bioethics: Asian Bioethics in the 21st Century, November 22-25, 2002, Seoul National University,

Seoul, Korea.

*** Associate Professor, Institute of Public Health, National Yang-Ming University.

*** Professor of Law, College of Law, National Taiwan University.

manipulated, there are also good reasons to be wary of its pitfalls. Hence, by drawing in experiences of bioethics commissions worldwide, particularly their recommendation for stem cell research, this article seeks to provide a critical examination of national commission’s ability to facilitate deliberative democracy and make concrete institutional suggestion as to how it can achieve it. With a size small enough to allow deliberative debate, yet pluralistic enough to reflect possible societal viewpoints, we argue that if properly structured, national bioethics commissions’ opinions can set a de facto burden of reasoning for public policy makers should they seek to decide otherwise. This in turn would create a pressure for sound moral reasoning in a policy area that tends to be infused with bio-politics and hence realize the ideal of deliberative democracy.

Keywords: National Bioethics Commissions, Deliberative Democracy, Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research

CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION... 72

II. THE NEED FOR DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY: BIO-POLITICS AND THE IDEAL CONDITIONS FOR DEBATE OF BIOETHICS ISSUES... 76

A. The Bio-Politics of Stem Cell Research... 76

B. Ideal Conditions for Moral Debates in Bio-Politics ... 78

III. BIOETHICS ADVISORY COMMISSIONS: THEIR PROMISES AND PITFALLS... 81

A. BAC’s Potential to Realize Deliberative Democracy: Recommended Functions in Theory ... 82

1. Clarify Factual Information Involved ... 83

2. Pinpoint Issues to Debate... 83

3. Allow People with Diverse Viewpoints to Participate... 83

4. Facilitate Reasoning for Moral Persuasion... 83

5. Provide Signal of Future Principles or Policies... 84

6. Keep the Public Informed... 84

7. Fortify Government Policy’s Political Legitimacy ... 84

B. Negative Lessons from U.S. Presidents’ Council on Bioethics... 85

IV. INSTITUTIONAL DESIGNS TO FACILITATE DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY: HOW CAN NATIONAL BIOETHICS COMMISSIONS BE USEFUL? ... 88

A. Some Concrete Suggestions... 88

1. Substantive Factors ... 89

2. Constitutive Factors ... 90

3. Capacity and Impact Factors... 94

B. Experts’ Legitimacy in Deliberative Democracy?: A Dual Track of Dialogue in Constitutional Democracy... 99

V. CONCLUSION... 101

I.INTRODUCTION

Combining the miracle of life and science, path-breaking developments in biomedicine tend to become front-page news and raise high hopes among patients and the general public. For instance, using embryonic stem cells, scientists are trying to revive degenerated tissues or develop organs.1 Should

they succeed, these developments would be a paradigmatic change in medicine and may solve the eternal problem of organ shortage that has prevented people from receiving life-saving organ transplantation. Using stem cell from embryos cloned from the patient’s cell, the technology of therapeutic cloning can further produce organ that may avoid graft versus host diseases. With techniques of somatic nuclear cell transfer, some even claim that they can clone people should they desire offspring with genes exactly identical with them.

Novel technologies as such have stirred moral concerns about the proper limit of science. As these concerns involve profound issues such as moral status of embryos or what makes humans human, they often reflect different attitudes that stems from more fundamental differences in religion, culture as well as political ideologies. This in turn makes disagreements in these issues morally too fundamental to compromise thus most difficult to resolve.

Policy frameworks worldwide are mostly ill-equipped to provide much guidance on these issues. Although issues like the permissibility to conduct embryonic stem cell research may fall within the periphery of regulations for reproductive medicine and relevant research, existing law is often inadequate to address these concerns since such novelty often did not occur to legislators in the past.

To cope with these situations, policy-makers worldwide have been seeking counsels from national bioethics commissions of all varieties. Many of these commissions were established to follow the legacy of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research2 that published the influential Belmont Report3 in the

1. So far, stem cell from bone marrow and umbilical cord blood are routinely used to treat leukemia, and scientists are experimenting to use stem cell to treat cancer, parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injuries, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis and muscle injuries. Developments for using stem cell to treat kidney diseases, heart diseases and liver diseases are also in progress. For an overview of the current status, see Preeti Chhabra et al., Regenerative Medicine and Tissue

Engineering: Contribution of Stem Cells in Organ Transplantation, 14 CURRENT OPINION ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION 46 (2009).

2. The Commission was established by the National Research Act, Pub. L. No. 93-348, 88 Stat. 342 (1974).

3 . For a history of the report, see Tom L. Beauchamp, The Origins, Goals and Core

Commitments, The Belmont Report and Principles of Biomedical Ethics, in THE STORY OF BIOETHICS:FROM SEMINAL WORKS TO CONTEMPORARY EXPLORATIONS 17, 39 n.7 (Jennifer K. Walter & Eran P. Klein eds., 2003).

United States, or the Warnock Committee4 that paved the way for the

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act in the United Kingdom.

An observation of these commissions indicates that, though mostly advisory in their nature, they often are expected to set the benchmark of the government’s bioethics policy. This influence sometimes comes from subsequent legislations that codify the commissions’ decision. But administrative agencies with decision-making powers may also adopt their recommendation directly and make it their policy.

As a result, from different perspectives, the performance of national bioethics commissions has been constantly under scrutiny. For instance, many scholars criticized U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics’ recent operation as partisan politics.5 George Annas also expressed his pessimism

in pointing out that “bioethics has been called on primarily by politicians to help them neutralize contentious issues, or to provide ethical cover for policy decisions that have already been made . . . , and when called on has usually been called on late and treated like a second-class citizen.”6 After

comparing blue ribbon bioethics commissions’ political influence in the U.S. and in the U.K., Riley and Merrill argues that although national bioethics advisory commissions may serve to inform the public, they cannot reach consensus when there is none in a society like the U.S.7

But whether commissions’ recommendation is adopted as the final policy or legislation should not be the only criteria to evaluate its performance, since it may also serve to clarify facts, probe issues, share perspectives, increase mutual understanding among opposing parties that are necessary for on-going public debate. Likewise, the fact that recent bioethics commissions tend to be tied up with politics only reminds us of the reality of bioethical policy, but does not provide us a reason to dismiss their value altogether. In fact, if properly structured and operated, national bioethics commissions may clarify facts and issues, facilitate opposing parties’ mutual understanding and lead toward better quality of decision-making in the future, if not right now. The real problem is how we can properly structure these commissions to make better use of them.

We think that the idea of deliberative democracy provides important insights for governments seeking to cope with moral disagreements in

4. MARY WARNOCK, A QUESTION OF LIFE: THE WARNOCK REPORT ON HUMAN FERTILISATION AND EMBRYOLOGY, viii-ix (1985).

5. Udo Schuklenk, National Bioethics Commissions and Partisan Politics, 22 BIOETHICS ii (2008).

6. George J. Annas, Will the Real Bioethics (Commission) Please Stand Up?, 24(1)HASTINGS CENTER REP. 19, 21 (1994).

7. Margaret Foster Riley & Richard A. Merrill, Regulating Reproductive Genetics: A Review of

American Bioethics Commissions and Comparison to the British Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, 6 COLUM. SCI. & TECH. L. REV. 1 (2005).

bioethical issues. According to Gutmann and Thompson, deliberative democracy is “a form of government in which free and equal citizens (and their representatives), justify decisions in a process in which they give one another reasons that are mutually acceptable and generally accessible, with the aim of reaching conclusions that are binding in the present on all but open to challenges in the future.”8

Although literature of deliberative democracy abounds, scholars constantly question how this ideal can be achieved through concrete institutional designs.9 In response, scholars have been experimenting

different formats of public participation such as citizen conference, citizen jury, deliberative polls or public consultations of more informal forms. Yet, except in Denmark, most of these forms of citizen participation are not institutionalized into ordinary structure of policy making.10 Moreover, what

relationship should these forms of public participation have with existing political institutions is unclear.

Given national bioethics commissions’ prominent presence in bio-politics worldwide and their possible influence over policy-making in bioethical issues, we think they deserve more critical analysis from a deliberative democratic point of view, particularly their potential to cope with intricate moral issues resulting from paradigmatic developments in biotechnology. Hence, instead of looking into substantive issues abound in bioethics, this paper chooses to examine “how” should these issues be decided, and “how” to structure a better bioethics commission that can facilitate a moral consensus in a democratic society.

In order to explore this issue, this article uses government policy of embryonic stem cell research as an example, because the intricate moral, political and religious issues involved crystallize the difficulties a government may encounter in coping with moral disagreements. This article will look into anecdotal studies based on national bioethics commissions including, but not limited to, the President’s Council on Bioethics of the U.S., and other commissions whose performance is available in the literature, and examine their promises and pitfalls in facilitating the idea of deliberative democracy which we think is most crucial for the policy making regarding embryonic stem cell research.

By relying upon literature on the operation of national bioethics commissions, this article obviously cannot claim to be a comprehensive or

8. AMY GUTMANN & DENNIS THOMPSON, WHY DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY 7 (2004). 9. For a survey of these discussions, see James Bohman, Survey Article: The Coming Age of

Deliberative Democracy, 6 J. POL. PHILOSOPHY 400, 419-22 (1998).

10. For a more introduction of how Denmark institutionalizes citizen participation into the policy making of science, see Lars Klüver, Consensus Conferences at the Danish Board of Technology, in PUBLIC PARTICIPATION IN SCIENCE: THE ROLE OF CONSENSUS CONFERENCES IN EUROPE 41 (Simon Joss & John Durant eds., 1995).

exhaustive study of all the pros and cons of national bioethics commissions’ function to facilitate deliberative democracy. Moreover, this article sees the ideal of deliberative democracy as a moral ideal that one must strive to achieve. Hence, even if we may not be able to identify clear causation between these commissions’ recommendation and the final government policy, it may only mean they have not succeeded yet, and that more work is required. In this sense, this study is just a beginning.

The term “bioethics commissions” requires some clarification upfront. Regardless of their actual title, modern societies often make use of commissions of various kinds to cope with bioethical issues. These commissions typically include people with backgrounds from medicine, biology, law, philosophy, and social sciences that can provide expertise or relevant view points useful in making a recommendation or decision.

Some of them have a legal status in the sense that the law mandated their existence and that their opinion has legal effects on individual cases. These include institutional review boards or research ethics commissions that approve researches involving human subjects or while monitoring the progress, intervening into researchers’ unethical conducts when necessary.

A second strand of ethics commissions refers to those with pure advisory function, and exits in non-governmental organizations such as hospital ethics commissions or ethics commissions in medical societies that advise their colleagues on ethical issues, mostly also in particular cases. Some of their decisions might lead to further discipline within the organization, but the authority to do so stems from bylaws of these private institutes or societies rather than statutes passed by the Legislature.

A third kind of ethics commissions refers to those set up by the government to provide bioethical counseling on a policy level rather than

case by case, to the ultimate policy-maker, be it the President, the Congress,

or a particular regulatory agency. These types of bioethics commissions exist in all levels of government or non-government organization in many formalities. This is the type of bioethics commissions we intend to explore in this article. We also choose to focus on national commissions simply because they tend to be the more important ones and have generated more recommendations for study. But our discussion applies to this type of commissions in all level of governments.

Reviewing bioethics commissions worldwide, Dodds and Thomson once distinguished the third type of commissions further into advisory commissions and policy-making commissions, depending on whether they report primarily to the public, or to government agencies that await their advice.11 But since some commissions that they categorize as policy-making

also make their recommendation and reasoning public, we think that this difference is more in a matter of degree, and will not distinguish the two in this article.

As of 2006, there are at least 89 national bioethics commissions existing in the world,12 such as the U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics, Germany’s

National Ethics Council, and Human Genetic Commission of the United Kingdom. Although their opinions may be advisory in nature, they carry a lot of weight in a democratic society because of their high level in the central government and visibility in the public.

In the following section, we first explain the nature of policy making of embryonic stem cell research, particularly on the fundamental issues that it raises and why traditional democratic politics is ill-equipped to cope with them. From a deliberative democracy point of view, we then explain ideal conditions for approaching the policy-making of such issue. Using anecdotal evidence from national bioethics commissions worldwide, we then identify promises and pitfalls of using them to facilitate deliberative democracy, and finally make concrete suggestions to policy-makers who seek to make use of them.

To sum up, this paper sees national ethics commissions as an opportunity to institutionalize deliberative democracy when coping with highly scientific, yet moralistic issues such as bioethics. Though without any formal decision-making power, national bioethics commissions with adequate transparency, accountability and inclusive membership are better equipped to conduct moral deliberation of highly scientific nature than other institutions in the constitutional democracy. With a size small enough to allow deliberative debate, yet pluralistic enough to reflect possible societal viewpoints, if properly structured, national bioethics commissions’ opinions can set a de facto burden of reasoning for public policy makers should they seek to decide otherwise. This in turn would create pressure for sound moral reasoning in a policy area that tends to be infused with bio-politics and hence realize the ideal of deliberative democracy.

II. THE NEED FOR DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY: BIO-POLITICS AND THE

IDEAL CONDITIONS FOR DEBATE OF BIOETHICS ISSUES

A. The Bio-Politics of Stem Cell Research

Since James Thomson first discovered a method to grow and isolate embryonic stem cell in 1998, the potential of human embryonic stem cell

Bioethics Organizations, 20 BIOETHICS 326, 328-30 (2006).

12. Id. at 326 (citing from the website of WHO. The website provided in this article no longer

research has raised many expectations among scientists and patients.13 With

embryonic stem cell’ ability to renew and regenerate tissues and organs, scientists are using it to revive injured spinal cord, hoping to allow patients to walk again.14 Scientists and patients are hoping that it could also be

applied in diseases such as cancer, vision loss, burns, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other degenerative diseases.

Yet, with the material it uses, human embryonic stem cell research is bound to raise controversy. Many societies have long been struggling with the moral status of human embryo in the issue of abortion.15 The legitimacy

to conduct stem cell research rekindles the issue upfront because here the embryo exists alone in a Petri dish rather than in a woman’s womb. In exploring the proper protection a government must provide for an embryo, it forces the government to weigh the lives of an embryo against potential therapeutic benefits it may yield for many patients, and challenges how far science should explore when it will sacrifice an embryo’s life.16

Unfortunately, although most countries have regulations in place to govern moral issues in abortion and reproductive medicine, the legality of embryonic stem cell research was not foreseen in the past and thus often not covered in these regulatory frameworks. Hence, often the agencies in charge have to make groundbreaking decision or seek statutory revision when necessary.

As the people’s representative body, the legislature is the legitimate decision-making institution to decide a policy issue as such. Yet, legislature’s agenda often is overloaded with more mundane issues such as public construction or social welfare where legislators can turn political interests more easily into future votes for reelections. Compared with them, potential developments that may benefit patients and proper protections a government should give to embryo are too delicate and sensitive to touch, unless there is clearer consensus among the society’s stakeholders and citizens. The administration that wishes to shore up their legitimacy or to hasten legislative authorization must clear the way for the legislature. Against this backdrop, it would be useful for administrative agencies with decision-making power to establish bioethics advisory commissions that are

13. James A. Thomson et al., Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts, 282 SCI. 1145 (1998).

14. H. S. Keirstead et al., Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cell

Transplants Remyelinate and Restore Locomotion After Spinal Cord Injury, 25J. NEUROSCI. 4694 (2005).

15. E.g. MARY ANN GLENDON, ABORTION AND DIVORCE IN WESTERN LAW (1987); LAWRENCE H. TRIBE, ABORTION: THE CLASH OF ABSOLUTES (1992).

16. E.g. Dan W. Brock, Is A Consensus Possible on Stem Cell Research? Moral and Political Obstacles, 32J. MED. ETHICS 36 (2005).

more than their adviser but also a facilitator for public awareness, debate and consensus.

Though being a moral debate in its essence, any issue like the moral status of embryo is bound to be permeated with politics because it challenges the very notion of human nature and personhood, and tends to be confluent with bioethical, social, religious and legal issues. Moreover, the issue raises concern of whether government should restrict scientists’ freedom of research with its coercive power in the name of embryo protection. Unfortunately, the scientific knowledge and the uncertainty of embryonic developments and risks greatly hamper ordinary people from comprehending, discussing, and even participating in the decision-making, which further reinforces the difficulty of resolving this issue.

B. Ideal Conditions for Moral Debates in Bio-Politics

Acknowledging the inevitableness of moral disagreements and the inadequacy of traditional democracy to cope with disagreements, Gutmann and Thompson propose deliberative democracy as a way to promote legitimacy of collective decisions, encourage public spirited perspectives on public issues, foster mutually respectful processes of decision-making, and finally, to help correct mistakes within the inevitable existence of moral disagreements.17 They argue that, under a more traditional aggregative or

interest-based model, politics is not meant to reshape interests, but rather to broker arrangements so that the final decision may reflect the majority’s preference.18 Yet, without asking any justification, this aggregative model of

democracy takes preferences as given and merely seeks to combine them in various ways that may seem fair and efficient.19 Hence, some reasonable

and fair preferences may be ignored or discounted simply because they do not produce an optimal result or do not pass the political wrestling.20 The

wrestle between economic development and environmental protection in public policy demonstrates this point: although an environmentally friendlier policy is crucial for the sustainable development of a country, these values tend to lose out in the political wrestling because of the more powerful interest groups behind economic development both in representative democracy and political lobbying.

In contrast, rather than simply a form of politics, the alternate idea of

17. GUTMANN & THOMPSON, supra note 8, at 10-12.

18. Joshua Cohen, Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy, in THE GOOD POLITY: NORMATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE STATE 17 (Alan Hamlin & Philip Pettit eds., 1989); Cass R. Sunstein, Preference

and Politics, 20 PHIL. & PUB. AFF. 3 (1991); Jack Knight & James Johnson, Aggregation and

Deliberation: On the Possibility of Democratic Legitimacy, 22 POL. THEORY 277 (1994). 19. GUTTMAN & THOMPSON, supra note 8, at 13.

deliberative democracy argues that politics ought to be a framework of social and institutional conditions that can facilitate free discussions among equal citizens, which includes, but not limited to, providing favorable conditions for participation, association and expression, and can tie the authorization to exercise public power to these discussion, by establishing a framework ensuring the responsiveness and accountability of political power to it through regular elections, conditions of publicity and so forth.21

Placing public reasoning, deliberation and justification in the center of democracy, Joshua Cohen raises four procedural standards for deliberative democracy. First, the deliberation should be proceeded in the form of argumentation so that information and reasons provided by the parties are critically tested in the process. Second, deliberation should be inclusive and public so that those who might be affected can participate equally. Third, deliberation must be free from external coercion. Fourth, deliberation should be free from internal coercion so that every participant has an equal opportunity to be heard, to bring in issues, to contribute, and to argue and to criticize proposals.22

But the implication of deliberative democracy is more than procedural standards. Indeed, David Estlund questions whether a decision that meets the procedural requirements is a good one in reality.23 Hence, scholars have

been proposing substantive principles to regulate the procedure. For instance, Gutmann and Thompson argue that deliberative democracy is more than just a procedural requirement. It also has substantive principles, including principle of reciprocity, principle of publicity and principle of accountability.24 To show mutual respect to fellow citizens that are free and

equal, the principle of reciprocity regulates the kind of reasons that should be given in the deliberation by requiring citizens that make moral claims appeal to reasons or principles that can be shared by fellow citizens similarly situated.25

In addition, the principle of publicity regulates the forum in which the reasons should be given. Namely, the reason given must be accessible to all citizens to whom they address, which means the deliberation must take place in public, and the content of the reason must be understandable to all.26

Finally, the principle of accountability regulates the agents to whom and by

21. Joshua Cohen, Procedure and Substance in Deliberative Democracy, in DEMOCRACY AND DIFFERENCE: CONTESTING THE BOUNDARIES OF THE POLITICAL 95, 99 (Seyla Benhabib ed., 1996). 22. Cohen, supra note 18, at 21-23.

23. David Estlund, Making Truth Safe for Democracy, in THE IDEA OF DEMOCRACY 71 (David Copp et al. eds., 1993).

24. AMY GUTMANN & DENNIS THOMPSON, DEMOCRACY AND DISAGREEMENT 52 (1996). 25. Id. at 55-57.

whom the reasons should be given.27

Likewise, Joshua Cohen proposes three other sets of principle, which begins with a principle of deliberative inclusion that guarantees wide expressive liberties such as freedom of religion.28 Secondly, Cohen proposes

the principle of the common good where a policy must at least advance the interest of all, and finally, the principle of participation where there is equal opportunity for all to have equal political influence.29

All of these substantive principles seek to ensure ideal conditions where free and equal citizens can conduct open dialogues and deliberation regarding their disagreements. To see why this could be possible under the idea of deliberative democracy, Gutmann and Thompson emphasize two additional characteristics of deliberative democracy that help to facilitate the deliberative process. First, the decision the reason tries to justify is binding only temporarily both morally and politically, since it will be continuously under scrutiny and may be modified or abandoned when it is proven to be imperfect, or even wrong.30 This may make it easier for opposing parties to

accept the decisions made. A second characteristic of deliberative democracy is its dynamic process which further requires citizens and their representatives to try to find justification that minimizes their differences with their opponents. This latter requirement is called “the principle of economy of moral disagreement,” which Gutmann & Thompson argue is useful to promote the value of mutual respect and encourage citizens to find common grounds.31

Having advocated for using deliberative democracy to cope with moral disagreements, Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson point out the potential for the “deliberation conditions” of moral debate in bioethics forums:

In some sense, bioethics was built on conflicts. Abortion, physician-assisted suicide, patients’ demand for autonomy all are staple and contentious issues. And the controversies continue to proliferate. What forum best serves such debates? A look at political theories of democracy can help answer that question. The most promising for bioethics debates are theories that ask citizens and officials to justify any demands for collective action by giving reasons that can be accepted by those who are bound by the action. This conception has come to be known as deliberative democracy.32

27. Id. at 128.

28. Cohen, supra note 21, at 102-08.

29. Id.

30. See GUTMANN & THOMPSON, supra note 8, at 6, 110-19. 31. GUTMANN & THOMPSON, supra note 24, at 85-94.

32. Amy Gutmann & Dennis Thompson, Deliberating About Bioethics, 27(3)HASTINGS CENTER REP. 38 (1997), reprinted in APPLIED ETHICS: CRITICAL CONCEPTS IN PHILOSOPHY 133, 133 (Ruth F.

Yet, in painting such a rosy picture for coping with moral disagreements in bioethics, Gutmann and Thompson stop short of providing any institutional suggestions as to “how” bioethics debates can be carried out in light of the idea of deliberative democracy, and what the possible institutional designs are. Given the need for interdisciplinary expertise, diverse moral perspectives, and dialogical setting required, we think that national bioethics commissions may be a potential institution to realize the ideal conditions for bioethics debate under a model of deliberative democracy. The following section explores this possibility.

III. BIOETHICS ADVISORY COMMISSIONS: THEIR PROMISES AND PITFALLS

Although national bioethics commissions have begun to proliferate in the past few years, using ad hoc commissions to provide advisory opinion on ethically controversial issues is not new. In response to the Tuskegee scandal, the U.S. federal government set up the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research that produced the famous Belmont Report in 1974 after the Congress so mandated. Facing the moral controversies raised by the birth of Louis Brown, the U.K. government set up the Warnock Committee to advise the government on the regulation of reproductive medicine that led to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act.33

Anticipating new bioethical issues to face, in the late 1990s, governments worldwide have been setting up bioethics commissions in the national level. This includes Austria’s Bioethics Commission, Canada’s Governing Council’s Standing Committee on Ethics, Denmark’s Danish Council of Ethics, Germany’s National Ethics Council and Ireland’s Irish Council for Bioethics.34 Other national bioethics commissions that have been quite visible have also been re-organized to reflect the government’s new agenda. President Bush of the United States set up his own President’s Council on Bioethics in 2002 to replace the former National Bioethics Advisory Committee. After a thorough review in the 1999, the government of the United Kingdom also set up the Human Genetic Commission in complement with other commissions that formed a regulatory and advisory framework.

Chadwick & Doris Schroeder eds., 2002).

33. For a survey of historical developments of national ethics councils, see MICHAEL FUCHS, NATIONAL ETHICS COUNCILS: THEIR BACKGROUNDS, FUNCTIONS AND MODES OF OPERATION COMPARED (2005), available at http://www.ethikrat.org/_english/publications/Fuchs_International_ Ethics_Councils.pdf.

34. Sources of these come from each national bioethics commission’s website available in English. They are provided merely as examples, and we do not claim to have made a comprehensive survey.

Formations of members for these commissions vary. A sketchy investigation through their English web cites show that they are mostly the creation by and advisors of the President or relevant administrative agencies. Commissions such as Australian Health Ethics Committee35 and Danish

Council of Ethics36 have enabling statutes, but most of the commissions are

set up by executive orders by the President or the head of relevant administrative agencies.

Most commission members are selected and appointed with fixed terms by the President or head of the relevant administrative agencies and act as policy advisors to them. But in some commissions like Danish Council of Ethics,37 a parliamentary committee joins the relevant agency in appointing

half of the commission members.

All of their opinions are advisory in nature, and they make suggestions mainly to the President or the head of the relevant agency. But the Health Council of the Netherlands and the Danish Council of Ethics both act as liaisons to the parliament and can also make suggestions to the parliament.38

Since their recommendations are not binding, they do not raise legitimacy issue at least from a legal point of view. Indeed, it is the legislature or the administration that decides to accept their recommendation or not, that must bear political responsibility through their decision-making power. Nevertheless, from a political point of view, given their interdisciplinary membership, bioethics advisory commissions (hereinafter BACs) can serve important functions in democratic societies if properly structured. The following section addresses this possibility.

A. BAC’s Potential to Realize Deliberative Democracy: Recommended

Functions in Theory

At the center of theories of deliberative democracy is their emphasis that all affected parties should have a say in the policy-making process; the final decision must be justified by sound reasoning; and the reasons must be given in a form that is understandable to the parties both substantively and procedurally. National bioethics commission may be able to help realize the conditions for moral debate by providing the following functions:

35 . Australian Health Ethics Committee (AHEC) Website, http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about/ committees/ahec/index.htm (last visited July 27, 2009).

36. Danish Council of Ethics Website, http://www.etiskraad.dk/sw294.asp (last visited July 27, 2009).

37. Members of the Danish Council of Ethics, http://www.etiskraad.dk/sw374.asp (last visited July 27, 2009).

38. Id.; Health Council of the Netherlands, http://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/en (last visited July

1. Clarify Factual Information Involved

One of the reasons ethics commissions invite scientists and physicians of different specialties is that they introduce technical expertise that governments may need in the policy-making of bioethical issues. Technologies may still be premature, and their impacts often are uncertain. Having experts in the ethics commissions may help to clarify the basic facts and provide the knowledge basis necessary to conduct meaningful debate. This is critical especially for bioethical policies that involve highly technical details difficult for the public to understand yet critical for decision-making.

2. Pinpoint Issues to Debate

Policy-making related to science and technology tends to involve subtle issues of moral significance disguised under highly technical issues. Issues of different levels in logic and priority are easy to get tangled together. National bioethics commissions can help to pinpoint important issues and scrutinize their priorities.

3. Allow People with Diverse Viewpoints to Participate

Usually members of the national bioethics commission are people with different trainings and values including, but not limited to, physicians, philosophers, sociologists, lawyers, scientists, and people with religious alliance. It is also crucial to include people that can reflect concerns of those whose interests are most affected. This will enhance the commissions’ understanding of the interests at stake, and make sure that the debate and deliberation is not biased.

4. Facilitate Reasoning for Moral Persuasion

Most national bioethics commissions distribute extensively written reports that should explain not only the different perspectives involved, but also why the commissions reached their decisions. This includes why did the commissions put certain values in priority, how did the commissions weigh the importance of all values involved, and its response to opposing opinions. Doing so would help the national bioethics commissions to facilitate on-going moral dialogue within the society, and is most critical for issues that are hotly debated and when the society is divided by very different viewpoints.

5. Provide Signal of Future Principles or Policies

Most national ethics commissions, though advisory in nature, may set ethical standards for the people to follow. They might also signal the governments’ regulatory policies in the future, simply because members that have certain intellectual expertise or cultural authority on that issue tend to be chosen as members in the first place, and the commissions often make their decisions for good reasons. For instance, the Belmont Report of 1978 was widely known for articulating the ethical principles that later became the foundation of Tom Beauchamp and James Childress’s influential textbook: the Principles of Biomedical Ethics.

6. Keep the Public Informed

With proper clarity and publicity, the commissions’ findings and recommendations help to inform the public with the issues being debated. This function is important because, though the public may or may not be able to express their opinion when members of the commission deliberates, the policy-maker that has political authority will have to accept or reject recommendation in light of the public’s opinion and their political wisdom. Therefore, it is important to keep the public informed as early as possible, and to allow public participation as early as possible, even during the commission’s deliberation.

7. Fortify Government Policy’s Political Legitimacy

Perhaps the most imporatant and common reason to set up these commissions are that, they provide legitimacy to government policy, even if it is an unpopular one, or even if it comes late. Again, although the commission does not enjoy any legal authority, the reputation of the members, the reaonings it provided, and sometimes the deliberative procedure they went through gives weight to their decision that the government later might endorse.

To sum up, in the post-genome era where fundamental values are often challenged and the future of the techonological development uncertain, national bioethics commissions may serve as a useful mechanism for governments to achieve multiple goals. This is more so when relevant parties and issues are highly politicalized. The format of a commission ensures wider participation, yet insulates decision-making process from politcal forum that is easy to loose control.

B. Negative Lessons from U.S. Presidents’ Council on Bioethics

Although bioethics advisory commissions could perform the foregoing functions, whether they do achieve them in reality is another matter. In fact, take those in the U.S. for example, although the federal government has established bioethics advisory commissions of different titles and formalities, most agree that only the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1974-1978) and the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1979-1983) are the two that are successful because their recommendations have been turned into legislation or widely referred to.39 But none of the current studies provide definite reason as to why these two succeeded.

But rather than trying to explain why a commission succeeded, it is often easier to explain what went wrong with a particular commission. Part of the reason is that there is limited information about the internal operation of one particular commission, and that mere observation of the recommendation does not explain much of the causations between success and failure.

While there have been a few studies on the history and operation of bioethics advisory commissions worldwide,40 none of the commissions has

raised as much public controversy as the recent U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics. Hence, drawing from its experience in making the controversial report “Human Cloning and Human Dignity: an Ethical Enquiry,” this section uses the Council as an example to generate lessons for how a bioethics commission should not operate, if it seeks to facilitate deliberative democracy.

The President’s Council on Bioethics was born in a time when the American society is most divided. Though with fewer popular votes compared to his opponent, George W. Bush won his presidency with a slight majority (271: 266) in electoral votes among which 25 of them were in dispute and took the court to settle it.41

Nevertheless, George Bush took a strong position on embryonic stem cell research right after he assumed the presidency. Not long after his inauguration, President George W. Bush announced in his first press conference a ban to use any federal funding for embryonic research unless

39. Riley & Merrill, supra note 7, at 8-14, 17-22, 36-37.

40. E.g. Bradford H. Gray, Bioethics Commissions: What Can We Learn from Past Successes and Failures?, in SOCIETY’S CHOICES: SOCIAL AND ETHICAL DECISION MAKING IN BIOMEDICINE 261, 286-87(Ruth Ellen Bulger, et al. eds., 1995); FUCHS, supra note 33; Riley & Merrill, supra note 7.

41. Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000); FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, 2000 OFFICIAL PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS (2001), http://www.fec.gov/pubrec/2000presgeresults. htm.

the research uses cell lines that were created before August 2001.42

At the same time, President Bush created the President’s Council on Bioethics. According to Executive Order 13237, the Commission’s mission is “to undertake fundamental inquiry into the human moral significance of developments in biomedical and behavioral sciences and technology.”43 Its

first task was to make recommendations on the ethics of human cloning including reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning that is crucial for stem cell research. In the cloning report, the opinion was divided, with 10 members favoring a four year moratorium on research, and 7 members favoring regulated permission.44 All three of the full-time scientists favored

regulated permission.

The report was criticized widely. Editorial of Bioethics, the official journal of International Association of Bioethics, charged the commission and its report as partisan politics and abuse of tax payers’ money.45 Other

commentators pointed out more specifically its questionable presumption of embryo’s moral status, unwillingness to make any comparison of cost and benefit when there are patients’ lives are at stake, and its inconsistency in banning federal funding but leaving the private sector free from committing what they think is wrong.46

As one of the only three full-time scientists among the members, Elizabeth Blackburn openly criticized the Commission being biased. Recounting her experience participating in the discussion of cloning issue in the Commission, “the best possible scientific information was not incorporated and communicated clearly in the council’s report, suggesting that the presentation was biased.”47

Corresponding to Blackburn’s comment, relevant critics also questioned the integrity of Bush’s Commission’s analysis. In February 2004, over 62 leading scientists, including 20 Nobel laureates published a statement accusing the Bush government of manipulating the objectivity and impartiality of scientific knowledge for its own political agenda;

42. President’s Address to the Nation on Stem Cell Research from Crawford, Texas, 37 WEEKLY COMP.PRES. DOC. 1149 (Aug. 9, 2001).

43. Exec. Order No. 13,237, 66 Fed. Reg. 59,851 (Nov. 28, 2001).

44 . PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL ON BIOETHICS, HUMAN CLONING AND HUMAN DIGNITY: AN ETHICAL INQUIRY (2002), available at http://www.bioethics.gov. Those supporting complete ban are Rebecca S. Dresser, Francis Fukuyama, Robert P. George, Mary Ann Glendon, Alfonso Gómez-Lobo, William B. Hurlbut, Leon R. Kass, Charles Krauthammer, Paul McHugh, and Gilbert C. Meilaender. Those favoring regulated permission are Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Daniel W. Foster, Michael S. Gazzaniga, William F. May, Janet D. Rowley, Michael J. Sandel, and James Q. Wilson.

45. Schuklenk, supra note 5, at ii.

46. Brock, supra note 16; Susan M. Wolf, Law and Bioethics: From Values to Violence, 32J.L. MED. & ETHICS 293, 298 (2004); Russell Korobkin, Embryonic Histrionics: A Critical Evaluation of

the Bush Stem Cell Funding Policy and the Congressional Alternative, 47 JURIMETRICS J. 1 (2006). 47. Elizabeth Blackburn, Bioethics and the Political Distortion of Biomedical Science, 350 NEW ENG. J. MED. 1379, 1380 (2004).

systematically replacing scientific experts with unqualified ones in federal advisory commissions; and suppressing unfavorable reports by the government’s own scientists.48 Donald Kennedy, the editor of another

prominent journal, Science, and also a commissioner of the Federal Drug Administration during the Carter Administration, also echoed this observation.49 He pointed out that the Bush administration often shut down

advisory commissions, reassembled it with new members, and screen candidates according to their loyalty.50

In fact, there has been a lot of controversy as to the Commission’s membership. Some said the membership was diverse at least before 2004,51

but many said it was biased from the very beginning.52 George Bush

replaced William E. May and Elizabeth Blackburn who both favored regulated permission with two more conservative members in 2004 when their term was over, but extended other members’ appointments. Many critiques also pointed out that the Commission’s conservative chairman Leon Kass and his staff had a firm grasp of the agenda and operation.53

In addition, commentators argue that compared with all Commissions that have made recommendations on embryonic research, the President’s Council on Bioethics differs in how it placed the burden of proof upon the opposite: other Commissions see it their duty to show enough justification to recommend the government to ban scientists’ freedom of research, but the President’s Council of Bioethics assumes that it is the science community’s burden of proof to show why their researches are not dangerous and should be free from regulation.54

The language the Commission used also mattered. Sheila Jasanoff observed that the Commission deliberately substituted the term “reproductive cloning” with “Cloning-to-produce-Children” to insulate its linkage with people’s reproductive freedom; and likewise replaced the term “therapeutic cloning” that could signify beneficial outcome of the cloning,

48. 2004 Scientist Statement on Restoring Scientific Integrity to Federal Policy Making (Feb. 8, 2005), http://www.ucsusa.org/scientific_integrity/abuses_of_science/scientists-sign-on-statement.html. The examples given by these scientists include childhood lead poisoning, environmental health, genetic testing, reproductive health, the protection of research subjects, and workplace safety. As of 2008, the statement has been endorsed by over 150,000 scientists since its announcement. For more detail, see also Robert Steinbrook, Science, Politics and Federal Advisory Committees, 350 NEW ENG. J. MED. 1454 (2004).

49. Donald Kennedy, An Epidemic of Politics, 299SCI.625, 625 (2003). 50. Id.

51. Riley & Merrill, supra note 7, at 33-36.

52. Arthur L. Caplan, Free the National Bioethics Commission, 19ISSUES IN SCI. & TECH. 85, 86 (2003); E. M. Meslin, The President’s Council: Fair and Balanced?, 34(2) HASTINGS CENTER REP. 6, 6-8 (2004); E. M. Meslin, Some Clues About the President’s Council on Bioethics, 32(1) HASTINGS CENTER REP. 8, 8 (2002).

53. Riley & Merrill, supra note 7, at 83-84; Caplan, id. at 86. 54. Riley & Merrill, supra note 7, at 33-36.

with “cloning-for-biomedical-research” that reminds people of the uncertainty and abuse that may result from researches.55

Lessons from the U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics thus teach us how political bioethics commissions can be. However, when George Annas expresses his pessimism in politicians’ tendency to use bioethics commissions to fulfill their own political agenda, he remains hopeful that bioethics can learn how to influence politics without being corrupted by it, and that these commissions’ merits depend on whether recommendations they make are well-articulated and well-reasoned, rather than being a government supported entity.56 Problems remain, however, as to whether we

can only rely on commission members’ good faith in making good recommendations? Or are there any institutional arrangements that can better ensure this to happen, at least more likely than not? The following section seeks to make some suggestions.

IV. INSTITUTIONAL DESIGNS TO FACILITATE DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY: HOW CAN NATIONAL BIOETHICS COMMISSIONS BE USEFUL?

A. Some Concrete Suggestions

Since the idea of deliberative democracy emphasizes mutual respect and on-going communication, whether a commission’s recommendation becomes the final law or policy may not serve as a good indicator to evaluate its performance. Nevertheless, what then are the important factors for such commissions to facilitate deliberative democracy?

In studying different types of bioethics commissions in the U.S., the Committee on the Social and Ethical Impacts of Developments in Biomedicine established by the Institute of Medicine provided three groups of criteria of success that we think are quite enlightening. First, the commissions must have intellectual integrity, which means that their analysis must be logical, the information they rely upon must be well-informed and used with sound judgment.57 Second, the commissions must be sensitive to democratic values, which includes showing respect for affected parties, ensuring that diverse perspectives can be represented in the discussion, and openness. 58 Finally, the commissions must be effectiveness in

communication with its audience, such as providing well-written reports that

55. SHEILA JASANOFF, DESIGNS ON NATURE: SCIENCE AND DEMOCRACY IN EUROPE AND THE UNITED STATES 195 (2005).

56. Annas, supra note 6, at 20-21.

57. Ruth Ellen Bulger et al., Criteria for Success, in SOCIETY’S CHOICES: SOCIAL AND ETHICAL DECISION MAKING IN BIOMEDICINE, supra note 40, at 150, 153-55.

policy-makers or the public can understand, and the commission must have authority from the sponsoring body and earn respect from the public with the soundness of the report.59

Similarly, Jonathan Moreno once summarized the criteria raised by the U.S. Congress’s Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) for a commission to operate successfully:60

(1) Relatively free of political interference. (2) Flexible to address issues.

(3) With processes and findings opened and well-disseminated. (4) Formed by members that have diverse backgrounds and

experiences, and are free of ideology.

(5) Not mandated to handle issues like abortion that might be “a priori” divisive.

(6) Adequate funding that allows enough staff to evaluate different perspectives with relative objectivity.

Nevertheless, many of these criteria have to be translated into institutional design in order to be useful for our discussion for national bioethics commissions. Hence, based on the procedural and substantive criteria raised by theorists of deliberative democracy and the foregoing observation of the promises and pitfalls of bioethics commissions, this section attempts to make concrete evaluations of how can they facilitate deliberative democracy.

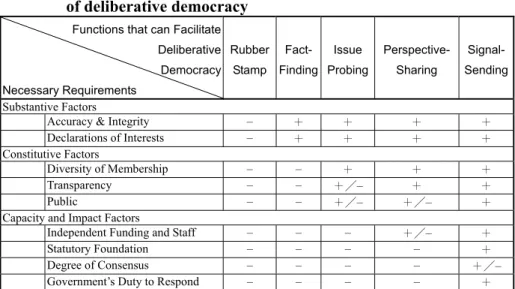

Based on their significance for commissions, we divide our suggestions for the institutional design of national bioethics commission into three factors: substantive factors, constitutive factors and finally, capacity and impact factors. We first explain their importance, and then argue that, the more requirements a commission fulfills, the more they will be able to facilitate deliberative democracy (Table 1).

1. Substantive Factors

By substantive factors, we refer to criteria that the substance of the commissions’ recommendation must meet. These serve as a minimum requirement for commissions to be able to facilitate deliberative democracy at all. Without meeting these criteria, the commission risks its own credibility in becoming rubber stamps of its sponsoring agency that no one would care about.

59. Id. at 159-60.

60. JONATHAN D. MORENO, DECIDING TOGETHER: BIOETHICS AND MORAL CONSENSUS 83 (1995).

(a) Accuracy in Facts & Integrity in Analysis

Of all the substantive criteria a commission must meet, the accuracy of facts and logics in analysis is the minimum. The foregoing discussion of Bush’s President’s Council on Bioethics manipulating scientific information for its own political agenda best demonstrates this lesson. When the editorial of Bioethics criticized it of playing partisan politics, they also pointed out that “the U.S. National Council on Bioethics . . . has well succeeded in reducing what has once been an influential voice in bioethics to pretty much that, a partisan political loud speaker that is more or less ignored by bioethicists and ridiculed in mainstream mass media.”61

(b) Declaration of Conflict of Interest

Given the technicalities often involved in bioethical issue, it is not always easy for lay person to evaluate the foregoing integrity of a commission. Thus, it would be helpful if the public can be informed of possible conflicts of interests that may affect the members’ integrity. This is most crucial for scientific experts because those who are most knowledgeable of cutting-edge technologies are often those involved in them. Depending on the availability of alternative candidates and balancing power of other members, sometimes it may not be possible or appropriate to exclude them from serving as a member in the commission. Facing this situation, the Human Genetic Commission of the U.K. requires its members to disclose their interests that might have any concern with the issues discussed, and withdraw from the meeting if their interests are direct and pecuniary or belongs other categories of interest that are prohibited from participating.62 As this would influence the content and the formation of the

Commission’s recommendation, the requirement to declare existing conflicts of interests serves a different purpose from the requirement of transparency that will be discussed below in the constitutive factors that influence the performance of a bioethics commission. A requirement to disclose conflicts of interests helps to ensure the neutrality of members, and also help establish the public’s trust in the commission.

2. Constitutive Factors

The foregoing requirement of intellectual integrity in the commission’s report is only a minimum requirement. Without proper institutional design, a commission could be biased from the beginning it sets its agenda, gather its information and conduct its debate, and will influence the constitution of the

61. Schuklenk, supra note 5, at ii.

62. Human Genetic Commission, Code of Practice for Members, http://www.hgc.gov.uk/Upload Docs/Contents/Documents/CODE%20OF%20PRACTICE%20FOR%20MEMBERS.pdf (last visited Aug. 31, 2009).

Commission’s substance. Hence, we further propose the following requirements in a commission’s institutional design:

(a) Diversity of Membership

An important feature for deliberative democracy is its commitment to allow all whose interests are affected to be heard. Hence, a necessary requirement for national commissions to realize the ideal condition for moral debate would be to bring in members that can reflect viewpoints of different perspectives. This institutional design corresponds to Gutmann’s principle of reciprocity and Cohen’s principle of deliberative inclusion discussed in the earlier part of this article that is most crucial to facilitate deliberation.

Again, George Bush’s PCB provides a lively example of what happens when the member is not diverse. As it reshuffled its membership more and more conservatively, its recommendation eventually was largely ignored by bioethicist and is often ridiculed by mass media.63

Nevertheless, whether these members should be elected representatives or experts familiar with the perspectives at stake is a more difficult issue. One model is to elect representatives from interest groups whose interests are affected, and to see the resulting decision as a compromise among different interest groups. But Dodds and Thomson argue that people may uncritically determine who gets to be represented simply by historical or cultural assumptions without sound justification.64 This mentality tend to

make lawyers or priests that have credential or higher social status one of the member, yet fail to include representatives from people with disabilities that lack credentials for their status, but whose voice may be more critical in bioethical issues. Hence, selecting members according to this model will allow representatives to pre-frame the debate of the issue and leave more pervasive problems and anxieties unaddressed.

Because of this reason, Dodds & Thomson favor a “contested deliberation model” where the issues to address and the representatives considered must be subjected to community hearings to before they can be appointed.65 This model sets a high standard for diverse membership of

these commissions, but they did not provide more information on how to prevent the issue of pre-framing in this additional procedure that is subject to public contest.

In any case, openness in the selection and appointment procedure would be useful to ensure the diversity of membership. In this regard, the Human Genetic Commission of the U.K. has opened its membership to anyone who cares to volunteer.66 Although this does not guarantee those who volunteer

63. Schuklenk, supra note 5, at ii.

64. Dodds & Thomson, supra note 11, at 334.

65. Dodds & Thomson, supra note 11, at 335-37.

do become members, it may broaden the candidates’ pool and allow more people that are less socially visible but motivated enough to contribute their perspectives in the deliberation.

Yet, additional design would be needed to overcome the barriers of achieving a diverse membership. Cass Sunstein, for instance, raises a concern that members of a deliberating group may become more extreme after the process of deliberation, because people with similar opinions tend to reinforce each others’ opinions and opinions from people who are socially disadvantaged tend to be ignored in the group dynamic.67 Hence, while he

advocates that deliberation must have opinions that can reflect those of relevant groups, it is desirable to make room for enclave deliberation among socially disadvantaged people so that they can form enough confidence and strong arguments for deliberation among a more diverse group.68

Facing these challenges, commissions should explore creative ways to broaden the scope of perspectives and opinions that can be considered beyond diverse membership. For instance, when a particular issue is most pertinent for minority communities, commissions can invite their representatives to participate in the discussion, or create sub-groups that include both members and external participants to look into the specific issue. In other occasions, commissions can also conduct public consultation to anticipate concerns of the general public that may not be reflected in the commissions’ membership. If necessary, commissions can even commission experts or social groups to present papers that can reflect important information or values that may be neglected in the membership.

Ultimately, there will also be a limit as to what perspective can be represented in a commission, and since people’s time and attention is limited, an appropriate level of heterogeneity should exclude opinions that are too invidious or implausible.69 With limited members able to participate

and the foregoing group dynamic that tend to reinforce majoritarian perspectives, these commissions may not be able to realize ideal condition of deliberation or reach any consensus. But at the minimum, diverse membership can foster a communicative democracy where people reach more understandings that allow better deliberation and cooperation in future dialogues.70

the Commission. Although we cannot find official documentation from HGC’s website, similar information can also be found in Michael Fuchs’ survey of HGC. See FUCHS, supra note 33, at 31. 67. Sunstein, supra note 18, at 27-34.

68. Id. at 19-24.

69. Id. at 19.

70. Iris Marion Young, Communication and the Other: Beyond Deliberative Democracy, in DEMOCRACY AND DIFFERENCE: CONTESTING THE BOUNDARIES OF THE POLITICAL, supra note21, at 120, 128-33.

(b) Transparency

The institutional requirement of transparency corresponds with Gutmann’s principle of publicity. Ideally, this would require publication of members list so that their integrity is subject to public scrutiny after they assume the responsibility. Moreover, to be truly accountable to the public and facilitate deliberative democracy, commissions should make an effort to make the content and process of their reasoning as transplant as possible. Such effort would include disclosing basic facts that they rely upon in languages understandable to the general public, detailed minutes of the process of discussion, and a well-written recommendation that reflects the perspectives taken into consideration, pros and cons that was being balanced, and the final conclusion. Particularly when there is serious disagreement among the members, commissions should also allow members of minority opinion to present dissenting opinions in the final report. The more transparent a commission’s operation is, the more thorough it can be subject to public scrutiny, hence the more accountable and trustworthy it will become.

(c) Public Participation

Some commission’s authorizing statute requires them not only to report to governmental agencies, but also to consult public opinions. For instance, the National Bioethics Advisory Commission of the U.S. was not required to incorporate public participation, but Australian Health Ethics Committee was legally required to do so.71

For public consultations to be meaningful, it is important to keep the public informed in advance of the basic facts involved, the issues that require deliberation, the agenda and timetable of the consultation, and ensure that relevant social groups have a chance to participate. Indeed, Dodd & Thomson argues that these formal consultations usually do not allow genuine public participation, because the scope of public response usually are very limited, and only very limited groups will be approached and asked to respond.72

Because of the foregoing limits, Dodds and Thomson’s “contested deliberation” model requires a three stage procedure where the issue, membership and deliberation will be each subjected to public scrutiny and that the final recommendation must take into account the viewpoints presented.73 But again, although one can appreciate the extensive procedure

that increases the opportunity and intensity of public participation, it is hard to see how they can avoid the public participation from becoming mere formalities.

71. Dodds & Thomson, supra note 11, at 330.

72. Id. at 335.

In fact, there may be a limit to what can be transparent and the degree of public participation. When Gutmann & Thompson raise the principle of publicity as a substantive principle to regulate deliberative process, they make it clear that this principle is acceptable only as a presumption, since sometimes secrecy is necessary.74 Other than occasions that involve

individual privacy, the most important justification for secrecy here is when secrecy is beneficial for deliberation.75 For instance, people tend to be more

creative and open without pressure from the public that tend to have high expectation.76 Moreover, it is also easier for people to admit their ignorance

and their need for more information without being embarrassed in the public.77 Worrying that such justification may be abused, Gutmann &

Thompson thus argue that for such secrecy to be justifiable, in most situation an operating government can and should justify the necessity of secrecy to its public in advance, and subject its outcome to scrutiny after the decision is made in secrecy.78

Indeed, to realize the idea of deliberative democracy, it is important not only to make sure that public participation is not compromised by unjustifiable excuses, but also to make sure that it is effective. This would require some innovation. For instance, to have a better grasp of experiences of people with genetic diseases, the Human Genetic Commission has invited people with such condition to volunteer as member of their consultative panel. Using different formats of public participation for different occasion and purpose, the Danish Board of Technology of Denmark has also developed formats such as citizen panel, consensus conference, and various other efforts to inform the public and simulate meaningful public participation.79 Ultimately, to facilitate deliberative democracy, at least the

final report must give reasons as well as its recommendations. Requiring more public consultation through effective forms would also reinforce representation of minority perspectives.

3. Capacity and Impact Factors

Once commissions establish intellectual integrity and have favorable constitutions that are conducive to deliberation, they would further require resources and legitimacy to enjoy political influence. We think that it would

74. GUTMANN & THOMPSON, supra note 24, at 95-127. 75. Id. at 114-26.

76 . Minou Bernadette Friele, Do Committees Ru(i)n the Bio-Political Culture? On the

Democratic Legitimacy of Bioethics Committees, 17 BIOETHICS 301, 311 (2003). 77. Id. at 312.

78. GUTMANN & THOMPSON, supra note 24, at 115-17.

79. For more information, see the Danish Board of Technology Website, http://www.tekno. dk/subpage.php3?page=forside.php3&language=uk (last visited July 29, 2009).

be desirable for them to have independent funding and staffs, enabling statutes, high degree of consensus, and most importantly, sponsoring agencies’ duty to respond to their recommendations.

(a) Independent Funding and Staff

Deliberation is costly. The federal government of U.S. authorized Bush’s PCB $5 million per year for four years, and during the 39 months of its operation, the members met 28 times which each generally spend 2 days, and published 17 reports.80

While having funding and staffs does not guarantee a well-reasoned recommendation from an unbiased commission, it would be almost impossible without independent funding and staffing. A commission with diverse membership, transplant operation and wide spread public consultation would need a capable group of administrative staffs to coordinate conference and public consultation; it would also need research staffs to help prepare the basic facts and issues. Without independent funding and staffs, their influence will be seriously limited.

(b) Statutory Foundation Providing Clear Terms of Reference

Early commissions in the U.S. had greater policy impacts and usually had statutory enabling acts.81 Later commissions, including the National

Bioethics Advisory Commission and the President’s Council on Bioethics were established by executive orders.82 These enabling statutes or executive

orders usually stipulate the commissions’ mission, and corresponds to Gutmann’s principle of accountability. Although this is not sufficient for a bioethics commission to have political influence, it is a necessary requirement in a modern constitutional democracy, and may also help to establish authority in its recommendations.

(c) Degree of Consensus and Room for Dissenting Opinion

In a liberal democratic society, moral disagreements are bound to exist in bioethical policies such as those in human embryonic research. According to John Rawls, when there is a conflict in what constitutes the “good” a society ought to achieve, the decision should not require everyone to agree. Rather, it should be decided by a procedure that will lead to a decision that

80. Ruth Ellen Bulger et al., Conclusions and Recommendations, in SOCIETY’S CHOICES: SOCIAL AND ETHICAL DECISION MAKING IN BIOMEDICINE, supra note 40, at 168, 191.

81. For instance, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was created by the National Research Act (Pub. L. 93-348) and the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavior Research was created by 42 U.S.C. § 300v (2006).

82. Bill Clinton established National Bioethics Advisory Committee with Executive Order 12975 in October 1995 when he became the president of the United States. Yet, its charter expired October 2001. By then, the new President George Bush appointed a new committee name President’s Council on Bioethics by executive order 13237. For more information on the history of these two committees, see JASANOFF, supra note 55, at 179-80.