Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 9, No. 2: 79-104

Practicing Deliberative Democracy in Taiwan

Processes, Impacts, and ChallengesTong-yi Huang and Chung-an Hsieh

Abstract

In 2000, the first power transfer between political parties in Taiwan’s history created a window of opportunity for institutional innovations. The rise of deliberative democracy in Western academia in the 1990s seemed to suit the new ruling party’s pursuit for legitimacy and good governance. Since 2002, academia and practitioners in Taiwan have experimented systematically with various deliberative mechanisms and have attempted to introduce them into Taiwan’s formal policy process. As a front-runner of new democracies in Asia and with a relatively open society, Taiwan’s experience in practicing deliberative democracy has referential value for democratic counterparts in Asia and other areas. In this essay, the authors use Taiwan as a case to illustrate how deliberative democratic mechanisms developed in this new democracy, and to explain both their influences on academia, the state, and society, and the challenges for the future. The authors also propose suggestions to address these challenges in order to incorporate deliberative democracy into the existing representative democratic system to improve the quality of democracy.

Keywords: Deliberative democracy, democratization, consensus conference.

S

tarting in 1990, the theory of deliberative democracy took a powerful turn1 in Western political science2 and among scholars in the field of publicTong-yi Huang is Professor in the Department of Public Administration, National Cheng-chi

University, Taipei, Taiwan. <tyhuang@nccu.edu.tw>

Chung-an Hsieh is a Ph. D. student, also in the Department of Public Administration, National

Cheng-chi University. <Chung-an Hsieh, 99256501@nccu.edu.tw>

1 See John S. Dryzek, Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

2 Bruce Ackerman and James S. Fishkin, eds., Deliberation Day (New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, 2004); James Bohman and William Rheg, eds., Deliberative Democracy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998); Dryzek, Deliberative Democracy and Beyond; James S. Fishkin, Democracy

and Deliberation: New Directions for Democratic Reforms (New Haven, CT: Yale University

administration in academia.3 Advocates of this new democratic theory believe

that democratic legitimacy in modern states should be enhanced by promoting effective deliberative opportunities and capabilities during the process of developing policy among those who are subject to collective decision making. Although this trend has its theoretical roots among Western political thinkers such as Edmund Burke, John Stuart Mill, John Dewey, John Rawls, and Jürgen Habermas, the revival of this thought has been attributed to one 1980 article published by Joseph Bessette.4 Bessette critiqued representative

democracy, creating the concept of deliberative democracy, in an attempt to counter inadequacies in the existing electoral system.5 Since then, deliberative

democracy has become a trend. Beyond inspiring scholarly debates regarding deliberative democracy, it has responded to research concerning representative democracy in the field of political philosophy6 and has significantly influenced

modern democratic governance. However, as Bohman stated, “Realist theories without aspirational ideals are empty; but aspirational ideals without empirical inquiry and testing are blind.”7 To substantiate the principles of deliberative

democracy, the Danish Board of Technology adopted a detailed design of deliberative democracy and implemented citizen deliberation in the process of formulating policy decisions,8 thus realizing the ideal put forward by

Bessette.

Paralleling the rise of the theory of deliberative democracy, Taiwan began its regime transition in the 1980s. This transition culminated in 2000,

Blackwell, 2003); Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson, eds., Why Deliberative Democracy? (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004); David Kahane et al., Deliberative Democracy

in Practice (Toronto: UBC Press, 2010); and Ian Shapiro, The State of Democratic Theory

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2003).

3 Terry L. Cooper, Thomas A. Bryer, and Jack W. Meek, “Citizen-Centered Collaborative Public

Management,” Public Administration Review 66 (2006): 76-88; Frank Fisher and John Forester, eds., The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning (London: UCL Press, 1993); John Forester, The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999); and Charles J. Fox and Hugh T. Miller, eds., Postmodern

Public Administration: Towards Discourse (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995). 4 Dryzek, Deliberative Democracy and Beyond, 2.

5 Joseph M. Bessette, “Deliberative Democracy: The Majority Principle in Republican

Government,” in How Democratic Is the Constitution? ed. Robert A. Goldwin and William A. Shambra (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1980), 102-116.

6 Joshua Cohen, “Deliberative Democracy Legitimacy,” in Deliberative Democracy in London: Essays on Reason and Politics, ed. James Bohman and William Rehg (London: MIT Press,

1997): 67-91; Shapiro, The State of Democratic Theory; and Helene E. Landemore, “Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and Why It Matters,” Journal of Public Deliberation 8, no.1 (2012), http://services.bepress.com/jpd/vol8/iss1/ (accessed October 29, 2012).

7 James Bohman, “Epistemic Value and Deliberative Democracy,” The Good Society 18, no. 2

(2009): 28-34.

8 John Gastil and Peter Levine, eds., The Deliberative Democracy Handbook: Strategies for Effective Civic Engagement in the 21st Century (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005).

when the first power transfer in Taiwan’s history occurred, in which the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) won the presidential election due to a breakup in the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT). With less than 40 percent of the electoral support and a minority in the Legislative Yuan, the DPP was in strong need of political ammunition and allies to compete with the KMT. Western political thought and the deliberative mechanism to renew democratic legitimacy under a representative system provided leverage to the DPP to compete with the Nationalist Party for legitimacy. In addition, like Western democratic countries, Taiwan’s vibrant democracy has suffered from declining public trust in government, mainly arising from the corruption and inefficiencies of the legislative branch, as well as from a lack of legitimacy in the policy-making process. The rise of deliberative democracy in Western academia caught the attention of scholars and practitioners in Taiwan, and they began to experiment with various deliberative mechanisms and attempted to introduce them into the formal policy process. As a front-runner of new democracies in Asia with a relatively open society, Taiwan’s case in practicing deliberative democracy has referential value for democratic counterparts in Asia and other areas. Therefore, this analysis uses Taiwan as a case study to discuss how the deliberative democratic mechanism developed in Taiwan, how it has influenced academia, the state, and society, and what challenges lie ahead for the future. Beyond demonstrating the process of how a theory or mechanism is transplanted or diffused to other countries, this study can act as a research case for theoretical and institutional diffusion. This has value as a reference for other developing democracies and for academia. Moreover, this study provides practical suggestions regarding likely challenges and effective responses to them, as the people of Taiwan consider the future of deliberative democracy in the island’s democratic development.

Democratic Legitimacy and the Development of Deliberative Democracy

Although there were academic works on deliberative democracy in the 1990s, systematic introduction of the theories and their application to public policy did not start until after the DPP took control of the executive branch of the central government in 2000. The DPP’s attempt to adopt deliberative democracy lies in its search for democratic legitimacy at three levels. The first level concerns its competition with the KMT for legitimacy of rule. The KMT claimed the Republic of China (ROC)-in contrast to the People’s Republic of China (PRC)-as the sole legitimate government representing greater China (including the mainland). Unlike the KMT, the DPP has hesitated to accept Republic of China as the official name of the country, if not advocated the establishment of a brand new country. After it won power, the DPP strongly embraced the value of democracy to strengthen its authority. Deliberative democracy, which places great emphasis on legitimacy, thus fulfilled the DPP’s need for justifiability when confronting competition from the KMT.

The search for democratic legitimacy at the second level regarded the problem of the gradual loss of public trust in representative democracy and its legitimacy. In 1987 after Taiwan’s central government announced the lifting of martial law, party restrictions were abolished as Taiwan began democratization. Then, after parliamentary reforms and various elections for the central legislative body, representative democracy in Taiwan was realized. Following the first presidential election in 1996, democratization in Taiwan peaked again. In 2000, the presidential election resulted in the first transfer of power between parties in the central government, and in 2008, the second party turnover was completed. Consolidation of democracy in Taiwan demonstrated the freedom, democratic values, and vitality of Taiwanese society. However, over the last few years, the operations of Taiwan’s democracy have faced problems, such as the general distrust of the people toward the legislature, the lack of policy legitimacy, values controversies, and intensified conflicts among stakeholders throughout policy processes.

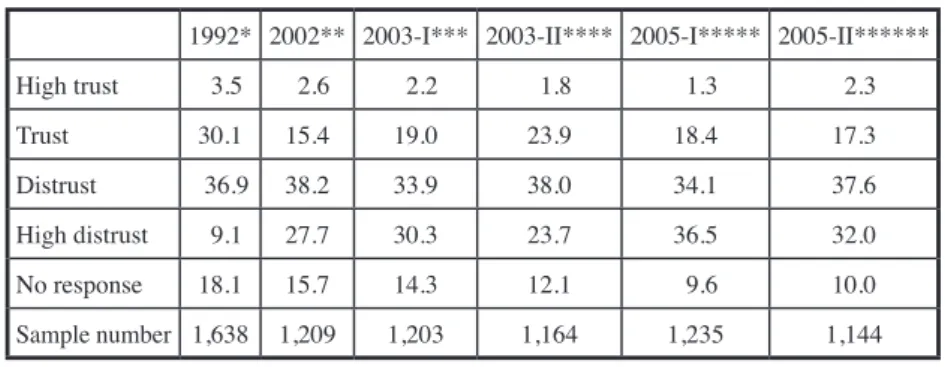

Even though the design of the democratic constitutional system permits the people to elect legislators regularly, research over the years reflects an increasing popular distrust of the Legislative Yuan. Table 1 shows the frequency distribution, summarizing data retrieved from online databases. The data reveal that Taiwanese people’s distrust of the legislative body increased from 46 percent to 56 percent between 1992 and 2002. Since 2002, distrust always has been over 60 percent; in 2005, the first survey showed that as much as 70 percent of the people distrusted legislative bodies. The statistical data mean that, even though Taiwanese democracy has reached a stage of consolidation, representatives generally have been unable to gain the trust of the people. This phenomenon corresponds with the early experience of Western democracy, which contributed to the academic exploration of the theory of deliberative democracy as a supplement to the current system.

The search for democratic legitimacy at the third level pertains to a lack of citizen involvement in the policy-making process. The political system in Taiwan has a structure of checks and balances regulating the authorities of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and the people directly elect the highest-level administrative authorities. Thus, one would expect officials to have considerable grounding in the will of the people. Recent analysis of the challenges faced by the government’s policy process, however, has shown that, among the many cases of the promulgation of policies at central- or local-government levels, the people gradually have started to doubt the legitimacy of government decisions. Such doubts have dissatisfied many, and this has resulted in obstacles to the implementation of policy.9 The failure of policy

9 Tsung-hsueh Hsieh, “The Political Economy of the Selection of Policy Instruments: Debating the Issue of the Minimum Wage in the National Economic Development Advisory Conference,”

Journal of Public Administration 9 (2003): 89-121; Yen-wen Peng, “An Implementation Research

Journal of Public Administration 28 (2008): 115-151; and Ching-ping Tang and Chung-yuan

Chiu, “Professionalism and Democracy: The Operation and Adaptation of Environmental Impact Assessment in Taiwan,” Journal of Public Administration 35 (2010): 1-28.

Table 1. Taiwanese People’s Trust in the Legislative Yuan (unit: %)

1992* 2002** 2003-I*** 2003-II**** 2005-I***** 2005-II****** High trust 3.5 2.6 2.2 1.8 1.3 2.3 Trust 30.1 15.4 19.0 23.9 18.4 17.3 Distrust 36.9 38.2 33.9 38.0 34.1 37.6 High distrust 9.1 27.7 30.3 23.7 36.5 32.0 No response 18.1 15.7 14.3 12.1 9.6 10.0 Sample number 1,638 1,209 1,203 1,164 1,235 1,144 Sources:

*Chin-chun Yi, “The Social Image Survey (General Survey of Social Attitudes in Taiwan): Regular Periodical Reports, Feb. 1992,” Preparation of National Science Council Project Reports, 1992, https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/group/sciitem/3/28 (accessed October 29, 2012).

**Chin-chun Yi, Nai-teh Wu, Chih-jou Jay Chen, Ying-hwa Chang, and Hei-yuan Chiu, “The Social Image Survey in Taiwan by Computer Assisted Telephone Interview Si02B, Dec. 2002,” Preparation of the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica Project Reports, 2002, https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/group/sciitem/3/78 (accessed October 29, 2012). ***Hei-yuan Chiu, “The Social Image Survey in Taiwan by Computer Assisted Telephone Interview Si03B, Dec. 2003,” Preparation of the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica Project Reports, 2003, https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/group/ sciitem/3/142 (accessed October 29, 2012).

****Yun-han Chu, “Taiwan’s Election and Democratization Study, 2003,” Preparation of National Science Council Project Reports, 2003, https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/group/ sciitem/3/939 (accessed October 29, 2012).

*****Hei-yuan Chiu, “The Social Image Survey in Taiwan by Computer Assisted Telephone Interview Si2005a, Jun. 2005,” Preparation of the Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica Project Reports, 2005, https://srda.sinica.edu.tw/group/sciitem/3/244 (accessed October 29, 2012).

******Wen-shan Yang, “The Social Image Survey in Taiwan by Computer Assisted Telephone Interview Si2005b, Dec. 2005,” Preparation of Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica Project Reports, 2005, https://srda.sinica.edu.edu.tw/group/ sciitem/3/245 (accessed October 29, 2012).

has resulted mainly from the fact that, during the policy process, central and local governments in Taiwan generally do not benefit from adequate public participation. A lack of appropriate mechanisms for participation produces public policies that are unacceptable to citizens, ultimately resulting in challenges to the legitimacy of policies and declining trust in the government.

In addition to problems due to the lack of participation channels, many scholars have observed the policy cases of Taiwan from the angle of stakeholders,10 discovering that the policy process involves diverse and complex

stakeholders with divergent values and interests. These varied positions often can cause difficulties in the establishment and implementation of public policies, resulting in major pressure on the government. Such shortcomings show that, even though according to Huntington’s view Taiwan has achieved consolidated democracy, in fact, Taiwan’s democracy is not fully mature, in part because the government’s policy decision-making process lacks effective participation and communication with the country’s citizens.

In addressing such problems, Wen-may Rei and Bingyan Lu reviewed past cases, finding that people’s doubt about the legitimacy of policies means that they believe the government’s decision-making processes insufficiently understand the popular will, especially regarding the disparate positions and attitudes of different stakeholders.11 To solve this problem, a carefully

designed platform should be used for dialogue and communication among policy stakeholders; Wen-may Rei believes that citizen forums founded on the principles of deliberative democracy can fulfill this role.

In an effort to search for legitimacy in competition with the KMT and in response to the pathologies of representative democracy-while also riding the wave of contemporary interest among Western political scientists in deliberative democracy-in the late 1980s, several articles were published in Taiwan to introduce deliberative democratic theory and to explore the possibility of its application in resolving environmental disputes. In 2002, two years after the DPP won the presidential election, the Department of Health of the Executive Yuan commissioned a research team, consisting of scholars from public health, sociology, and public administration, to hold the “Policy-Making of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance: The Pilot Project of the Citizen Conferences,” beginning the practice of deliberative democracy in Taiwan. In addition to the Citizen Conferences, this research team experimented with the pilot run of 10 Kun-jung Liao and Ya-feng Chen, “Local Developmental Policy in the Perspective of

Post-materialism: The Pin-Nan Case of Tainan County,” Chinese Public Administration Review 12, no. 4 (2003): 43-76; Guang-xu Wang, “Policy Network Analysis from the Action-System Perspective: A Case Study of the Taichung Industrial Park Road-Extension Controversy,”

Political Science Review 37 (2008): 151-210; Morgan Chih-tung Huang and Richard Ruey-chyi

Huang, “Saying ‘Not Safe’ is Not Enough: When Different Moral Worlds Collide on the Issue of Importing US Beef,” Journal of State and Society 9 (2010): 151-188; and Chun-chieh Ma, “A Study on the Cognition of Public Participation in Local Cultural Creative Industry Policy,”

Journal of Public Administration 40 (2011): 2-40.

11 Wen-may Rei, “An Institutional Design to Enhance Citizen Participation in the Policy-Making of

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance: The Pilot Project of Citizen Conferences as an Example,”

Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 1, no. 4 (2004): 57-81, and Bing-yan Lu, Yuen-hsiu Lin, and

Shuo-wen Wu, “From Policy Argument to Policy Discourse: A Case Study of Taiwan’s Bed and Breakfast Policy,” Chinese Journal of Administration 82 (2010): 1-22.

Deliberative Polling, the Scenario Workshop, and Forums with Citizens and Social Groups. All these novel forms of citizen participation were used to clarify issues and to forge consensus on Taiwan’s National Health Insurance.

The National Health Insurance Task Force not only introduced theories and hosted deliberative forums, but also held training workshops to disseminate the ideals of, and expertise for, practicing deliberative democracy. In 2004, three lines of development began with the central government, academia, and community colleges. Within the central government, the National Youth Commission of the Executive Yuan held innovative youth events, including the Youth National Affairs Conference, with preparatory meetings in northern, central, southern, and eastern Taiwan. During this conference, more than six hundred youth participated in deliberation about national issues. The regional conferences culminated in a national conference in Taipei to forge consensus regarding the issues discussed in the regional meetings. This was the first major large-scale deliberative event in Taiwan. In academia, there also were consensus conferences. Different departments and bureaus of the central and local governments commissioned universities to implement these conferences, diverging from the model of pure government implementation of the Youth National Affairs Conference. For example, at the grass-roots level, Beitou Community College held two consensus conferences related to matters of community development.

In practicing deliberative democracy, the research team not only applied the models developed in Western democracies, but also attempted to invent new deliberative mechanisms to apply to different arenas. In the 2005 campaigns of the Tainan County gubernatorial election and the 2008 Taipei City mayoral election, deliberative debate forums were held in which ordinary citizens, instead of celebrities, were sampled to raise questions for the candidates in a nationally televised debate. These events were scholarly efforts to combine the theories of deliberative democracy and representative democracy. Sponsors of the events hoped that informed and rational interaction and dialogue between the people and the candidates, which was televised, would allow the electorate to better understand the positions and attitudes of candidates toward major policies, and, in turn, help the people to elect candidates who could effectively respond to their needs.

The return of the KMT to the central government in 2008 witnessed a decline in the momentum of practicing deliberative democracy. However, the idea has diffused to different sectors of society, and several governmental departments and bureaus still rely on deliberative mechanisms to resolve policy disputes. In addition, since the KMT took control of the central government in 2008, the government has encountered opposition from local citizens and social groups, which has hampered the implementation of major projects such as the construction of the Guo-kuang Petroleum Plant and Taichung Science Park III as well as several city renewal projects. In 2012, the government encouraged different departments to hold deliberative meetings in keeping

with the model of the “World Café." The follow-up, however, is not clear at the time of writing.

Academia and Deliberative Democracy in Taiwan

The internal political context explains the efforts of the DPP to adopt deliberative democracy in policy processes. These efforts, however, could not have succeeded without the facilitation of academia. As illustrated previously, scholars not only introduced the theory of deliberative democracy but also played a key role in innovating and applying deliberative mechanisms in the public policy process as well as in electoral campaigns. Due to academia’s systematic introduction and experiments, Taiwan’s scholarly discussions and practice of deliberative democracy also reflect the problems of the theory. Next, a look at the development of deliberative democracy in the West is warranted.

Development of Deliberative Democracy in the West

In the 1980s, many political philosophers began to critique contemporary mainstream democratic systems.12 Bessette believed that the principle of

majority rule and institutional mechanisms of constitutionalism would produce many paradoxes and be unable to genuinely reflect popular will.13 However,

social choice theorists criticized the mainstream democratic system the most.14

Primarily, they believed that majority rule would cause problems, such as arbitrariness and minority control,15 in turn, leading to distrust in democracy.

The theory of deliberative democracy gradually strengthened within the context of growing distrust of the democratic system.

In 1990, the Danish Board of Technology used citizens’ meetings and other models to realize the practice of deliberative democracy, which further promoted other related discussions. These discussions in past literature can be divided into three categories. The first is the perspective from political philosophy that explores the pros and cons of deliberative democracy from a theoretical standpoint. This line of research includes considerations of how deliberative democracy can enhance civic participation in the collective decision-making process, elevate democratic legitimacy,16 address the challenge of activists

toward deliberative democracy,17 and advance deliberative democracy and

12 Bessette, “Deliberative Democracy”; Dryzek, Deliberative Democracy and Beyond; and

Shapiro, The State of Democratic Theory.

13 Bessette, “Deliberative Democracy.”

14 Dryzek, Deliberative Democracy and Beyond, and Shapiro, The State of Democratic Theory. 15 Shapiro, The State of Democratic Theory.

16 Landemore, “Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and Why It Matters.”

17 Iris Marion Young, “Activist Challenges to Deliberative Democracy,” Political Theory 29, no.

group representativeness.18 The second category concerns the practice of

deliberative democracy, which explores conditions conducive to the realization of the deliberative principle and the difficulties that are faced. Scholars argue that the objective of deliberative democracy is to revive civic culture and to improve the nature of public deliberation, in the belief that political solutions to urgent problems require effective action.19 In this regard, some scholars have

discussed the procedures and conditions for deliberative democracy,20 political

justice,21 multiculturalism,22 the practical role of valuing freedom and equality,

assessment of the model of citizen participation,23 the debate over procedural

justice,24 and the possibility of e-democracy.25 The third category focuses

on the effect of deliberative democracy, more specifically, on its influences on policy outcomes and society as a whole. Fishkin and Rosell state that the operational model of deliberative democracy can help governments improve policy consultation that has been limited to opinion polls, public hearings, and focus groups. In these traditional consultation models, people have insufficient understanding of policy, and may acquire biased policy attitudes.26 Compared

to exploring the role of deliberative democracy in the policy process, Kanra concludes that observation of practical experiences shows that people holding different values are more engaged in social learning through exchanges of their 18 Pablo De Greiff, “Deliberative Democracy and Group Representation,” Social Theory and Practice 26, no. 3 (2000): 397-415, and Cynthia V. Ward, “The Limits of Liberal Republicanism:

Why Group-Based Remedies and Republican Citizenship Don’t Mix,” Columbia Law Review 91 (1991): 581-607.

19 Edward C. Weeks, “The Practice of Deliberative Democracy: Results from Four Large-Scale

Trials,” Public Administration Review 60, no. 4 (2000): 360-372.

20 Bohman and Regh, Deliberative Democracy.

21 James S. Fishkin, “Deliberative Democracy and Constitutions,” Social Philosophy & Policy 28,

no. 1 (2011): 242-260, and Dhanaraj Thakur, “Diversity in the Online Deliberations of NGOs in the Caribbean,” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 9, no. 1 (2012): 16-30.

22 Isabel Awad, “Critical Multiculturalism and Deliberative Democracy: Opening Spaces for More

Inclusive Communication,” Javnost-The Public 18, no. 3 (2011): 39-54.

23 Gastil and Levine, The Deliberative Democracy Handbook.

24 Mauro Barisione, “Framing a Deliberation: Deliberative Democracy and the Challenge of the

Framing Process,” Journal of Public Deliberation 8, no. 1 (2012), http://services.bepress.com/ jpd/vol8/iss1 (accessed October 29, 2012).

25 Lincoln Dahlberg, “The Internet and Democratic Discourse: Exploring the Prospects of Online

Deliberative Forums Extending the Public Sphere,” Information, Communication, and Society 4, no. 4 (2001): 615-633; Robert Carlitz and Gunn Rosemary, “E-rulemaking: A New Avenue for Public Engagement,” Journal of Public Deliberation 1, no. 1 (2005), http://services.bepress. com/jpd/vol1/iss1/ (accessed October 29, 2012); and Kimmo Grönlund, Lim Strandberg, and Staffan Himmelroos, “The Challenge of Deliberative Democracy Online: A Comparison of Face-to-Face and Virtual Experiments in Citizen Deliberation,” Information Polity 14 (2009): 187-201.

26 Jame S. Fishkin, and Steven A. Rosell, ”Choice Dialogues and Deliberative Polls: Two

ideas.27 Since the practice of deliberative democracy affects learning, some

scholars have begun to promote the spirit of deliberation in other areas-at the current time, most prominently in educational philosophy28-hoping to

introduce relevant courses to cultivate students’ abilities in communication and discourse.

Academic and Research Development in Deliberative Democracy in Taiwan

In academic research in Taiwan, the first article on deliberative democracy was published in 1998 by political philosopher Jun-hong Chen. The article explored the correlation between sustainable development and democratic politics and introduced deliberative democratic theory in an attempt to discover possibilities for environmental sustainability in the problematic setting of traditional representative democracy and liberal democratic mechanisms.29

Thereafter, the academic and practical sectors of Taiwan began to hold diverse discussions and deliberative events.

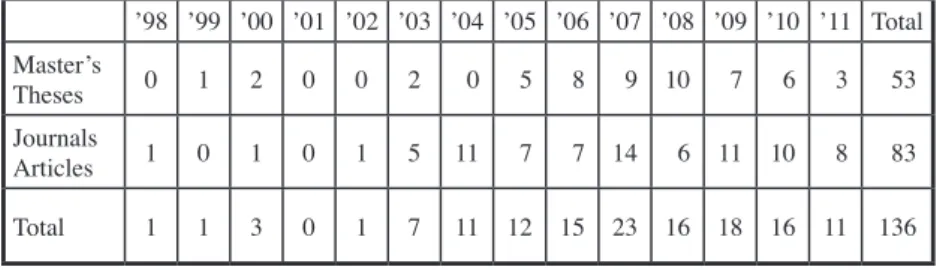

Academic works show the extent of the attention paid to deliberative democracy by academics in Taiwan. The effect of deliberative democracy in Taiwan was first demonstrated in the publication of books. Twenty-one books and translated works about deliberative democracy have been published in Taiwan since 2005. Aside from books, table 2 illustrates that, in 1998, studies of deliberative democracy began to appear in academic journals, earlier than the commissioned research projects by the National Science Council; the

27 Bora Kanra, “Binary Deliberation: The Role of Social Learning in Divided Societies,” Journal of Public Deliberation 8, no.1 (2012): 1-24, http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol8/iss1/

art1(accessed October 29, 2012).

28 Scott Fletcher, “Deliberative Democracy and Moral Development,” Philosophy of Education

(2005): 171-174.

29 Under the system of pluralism and representative democracy, the economic behavior of people

is to pursue personal interest blindly, ignoring the environmental protection-related public issues to such an extent that “The Tragedy of Commons” happened, and the environment could not be sustained. From Chung-hong Chen, “Sustainable Development and Democracy: Approaches to Deliberative Democracy,” Soochow Journal of Political Science 9 (1998): 85-122.

Table 2. Theses and Journal Articles on Deliberative Democracy in Taiwan (unit: piece) ’98 ’99 ’00 ’01 ’02 ’03 ’04 ’05 ’06 ’07 ’08 ’09 ’10 ’11 Total Master’s Theses 0 1 2 0 0 2 0 5 8 9 10 7 6 3 53 Journals Articles 1 0 1 0 1 5 11 7 7 14 6 11 10 8 83 Total 1 1 3 0 1 7 11 12 15 23 16 18 16 11 136

following year, a graduate thesis on the topic was completed. However, there were few academic works between 1998 and 2003, which did not change until 2004. In 2004, even though there were no associated graduate theses, eleven articles on deliberative democracy were published in the academic journals of Taiwan. One might say that the golden age of deliberative democracy in Taiwan’s academia has been between 2004 and the present, with more than ten journal articles and graduate theses published annually. In addition to academic publications, it is possible to use the volume of nationally subsidized research to understand the emphasis on deliberative democratic theoretical research. From 1999 to 2012, National Science Council research funding for deliberative democracy projects shows that there were twenty-five approved applications, with a total funding of over twenty-five million New Taiwan Dollars. This demonstrates that, in Taiwanese academia, deliberative democracy gradually has become a significant academic field.

Like academia in the West, academic discussion of deliberative democracy in Taiwan can be broadly categorized into three areas: philosophy, practice, and evaluation. Political philosophy primarily focuses on exploration of the philosophical roots of deliberative democracy and critique of this thought. Some scholars also have gone beyond criticizing deliberative democracy and attempted to understand whether there are opportunities for the combination of deliberative democracy and existing mainstream democratic systems.30

Regarding the practice of deliberative democracy, some scholars, mainly sociologists, are concerned primarily with the relationship between the state and society, as they attempt to understand the effects of introducing deliberative democratic models on the relationships among state, society, and the people.31 In line with this focus on the practice of deliberative democracy,

some public administration scholars concentrate mainly on the processes and dimensions of civic participation in policy. They use many case analyses in an attempt to discuss the possibilities and effects of the public’s participation in public policy, as well as the possibilities of dialogue among citizens, social 30 Chao-cheng Chen and Chih-long Tseng, “A Reflection on Chantal Mouffe’s Critics on

Deliberative Democracy,” Soochow Journal of Political Science 30, no. 1 (2012): 81-134; Juin-lung Huang, “Anti-intellectualism and the Rule of Law: Plato on Deliberative Democracy,”

SOCIETAS 35 (2010): 103-145; Ching-chane Hwang, “Deliberative Democracy: The Feminist

Pros and Cons,” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 5, no. 3 (2008): 33-69; Roy Kuo-shiang Tseng, “The Moral Constraints of Deliberative Democracy: Isaiah Berlin on Political Freedom and Political Judgment,” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 4, no. 4 (2007): 71-108; Chiu-yeoung Kuo, “Theory of Polyarchal Democracy: A Theoretical Foundation for Citizen Deliberation,” Taiwan

Democracy Quarterly 4, no. 3 (2007): 63-107; and Chen, “Sustainable Development and

Democracy.”

31 Kuo-ming Lin, “State, Civil Society, and Deliberative Democracy: The Practices of Consensus

Conferences in Taiwan,” Taiwan Sociology 17 (2009): 161-217; Kuo-ming Lin, “Public Sphere, Civil Society and Deliberative Democracy,” Reflexion 11 (2009): 181-195; and Huo-Wang Lin, “Deliberative Democracy and Civic Education,” National Taiwan University Philosophical

groups, government officials, and experts.32 Other scholars have gone further

and explored applications of the deliberative spirit and other dimensions, such as the application of deliberative democracy in education.33 When evaluating

deliberative democracy, scholars have used deliberative principles as yardsticks for assessing policy deliberation in the Legislative Yuan.34 Scholars in the field

of public administration also are concerned with evaluating the mechanisms of deliberative democracy; determining whether the people’s opinions in deliberative conferences can effectively influence government decisions;35

and comparing different types of civic participation.36 The development of

32 Ya-hui Fang and Chao-cheng Lin, “Promotion of Local Residents to Engage in Public

Participation in the Community University: A Case Study of the Community Supervisor Learning Course on the Betiou Cable Car,” Journal of Adult Lifelong Education 17 (2011): 107-147; Mei-fang Fan and Chih-ming Chiu, “The UK’s Public Debate on GM Crops and Foods: Evaluation of the Model of Public Participation in Science and Technology Decision-Making,”

Journal of Public Administration 41 (2011): 103-133; Ya-hui Fang, “The Learning Process

of Active Citizenship in the Context of Deliberative Democracy: Case Study on the Scenario Workshop of the Yanshuei River Belt,” Journal of Adult Lifelong Education 14 (2010): 33-73; Yun Fan, “Story-telling and Democratic Discussion: An Analysis of an Ethnic Dialogue Workshop in Civil Society,” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 7, no. 1 (2010): 65-105; Tze-luen Lin and Liang-yu Chen, “Return to the Policy Science of Democracy: The Concept and Approach of Deliberative Policy Analysis,” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 6, no. 4 (2009): 1-47; Hung-jeng Tsai, “Technocracy, Democratic Participation, and Deliberative Democracy: The Case Study of the Cable Car Citizen Conference,” Taiwanese Journal of Sociology 43 (2009): 1-42; Wen-ling Tu, Kuo-wei Chang, and Chia-chun Wu, “The Experiment of Deliberative Democracy on the Spatial Issue: The Case of ‘the Scenario Workshop’ on the Safe Routes to Schools around the Chung-Kang Drainage Channel,” Journal of Public Administration 32 (2009): 69-104; and Kuo-ming Lin and Dung-sheng Chen, “Consensus Conference and Deliberative Democracy: Citizen Participation in Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Policies,” Taiwan Sociology 6 (2003): 61-118.

33 Chun-wen Lin, “A Study of Teachers’ Deliberative Democratic Competence and Its Implications

for Multicultural Education,” Journal of National Pingtung University of Education 36 (2011): 241-280.

34 Pei-yin Liu and Tong-yi Huang, “Content Analysis of Administrators’ and Legislators’ Discourse

in Policy Legitimation: Deliberative Democracy Perspective,” Journal of Public Administration 38 (2011): 1-47.

35 Dung-sheng Chen, “The Limits of Deliberative Democracy: The Experience of Citizen

Conferences in Taiwan,” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 3, no. 1 (2006): 92-104, and Tong-yi Huang, “After Deliberation: Exploring the Policy Connection of the Consensus Conference from Public Sectors’ Perspectives,” Soochow Journal of Political Science 26, no. 4 (2008): 59-96.

36 Don-Yun Chen, Tong-Yi Huang, Chung-Pin Lee, Naiyi Hsiao, and Tze-Luen Lin, “Deliberative

Democracy under ICTs in Taiwan: A Comparison between On-line and Face-to-Face Citizen Conferences,” Public Administration & Policy 46 (2008): 49-106; Frank Cheng Shan Liu, “The Challenges of Practicing Deliberative Democracy in Taiwan and a Possible Solution,” Chinese

Public Administration Review 17, no. 2 (2009): 109-132; Jin Lo, “Degree of Deliberation for

Online Discussion: Examination of the Su-Hua Highway Forum,” Public Administration &

Policy 51 (2010): 125-170; Chung-pin Lee and Tong-yi Huang, “The Practical Value and Status

of Deliberative Democracy in Taiwan: An Exploratory Case Analysis of Citizen Conferences,”

academic research pertaining to deliberative democracy described above shows that, although research on deliberative democracy has not been affected as strongly in Taiwan by the deliberative trend as stated by Dryzek, research on deliberative democracy is highly significant in Taiwanese academia.37

Deliberative Democracy and the State

The previous section on academic research in Taiwan shows that scholars have placed great emphasis on the theory and practice of deliberative democracy, as reflected in the funding of projects by the National Science Council, and reveals that the first practice of deliberative democracy arose due to interaction between the state and Taiwan’s academic communities.38 However, by tracing

the development of deliberative democracy in Taiwan, one discovers that-aside from the pilot projects regarding National Health Insurance-the Youth National Affairs Conference held by the National Youth Commission of the Executive Yuan between 2004 and 2007 was the driving force behind the spread of the vision of deliberative democracy in Taiwan.39

After DPP President Chen Shui-bian was reelected in 2004, he faced a group of students protesting at Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall for the right to participate in national affairs. President Chen met with the students and promised to create a platform from which youth could express their opinions about national policy. Thereafter, the head of the National Youth Commission, Cheng Lichun, introduced the spirit of deliberative democracy by holding four Youth National Affairs Conferences. At this time, the government devoted much energy to convening deliberative events and cultivating youth with capabilities in organizing and sponsoring them, in the hope of using the training process to disseminate the ideals and practical methods of deliberative democracy. However, the government did not hold deliberative gatherings only in response to pressure from the people. Research results in Taiwan indicate that the government was forced to establish a platform for public participation by the divided government, the Blue-Green political hostility, and the value conflicts among stakeholders.40 The main benefits of deliberative conferences

are that they respond to the popular will, can be used to help persuade parliament to adopt and fund the administration’s policy, and help convince

between Informed Citizens and Public Governance,” Open Public Administration Review 22 (2011): 159-179.

37 Dryzek, Deliberative Democracy and Beyond. 38 Lin, “State, Civil Society, and Deliberative Democracy.” 39 Ibid.

40 Chia-yi Tseng and Tong-yi Huang, “Why Does Government Adopt the Consensus Conference?

The Policy Learning Perspective,” paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Taiwanese Political Science Association, Politics in the Age of Unrest: Theory and Practice, July 2009, Hsuan Chuang University, Hsinchu.

elected administrative officers to support the executive branch. Because they consult diverse stakeholders and enhance the transparency of policy,41

deliberative conferences also are alternative sources of gaining legitimacy for the mechanisms of government decision making.42

The Government and Deliberative Democratic Practice in Taiwan

Although academics in Taiwan had engaged in discussions about the theory of deliberative democracy by 1998, the practice of deliberative democracy did not start until 2002. The Department of Health of the Executive Yuan commissioned a second-generation health insurance planning team to hold the National Health Insurance Payment consensus conference, which set a precedent for joint promotion by the government and scholars. The consensus conference of 2002 not only stimulated academia but also greatly affected nonprofit organizations, local governments, and communities.

In 2004, the National Youth Commission held the first national deliberative conference, the Youth National Affairs Conference. The president of the Executive Yuan, Yu Shyi-kun, instructed the departments of the Executive Yuan to introduce the consensus conference model with the spirit of “deliberative democracy” to address controversial public policies.43

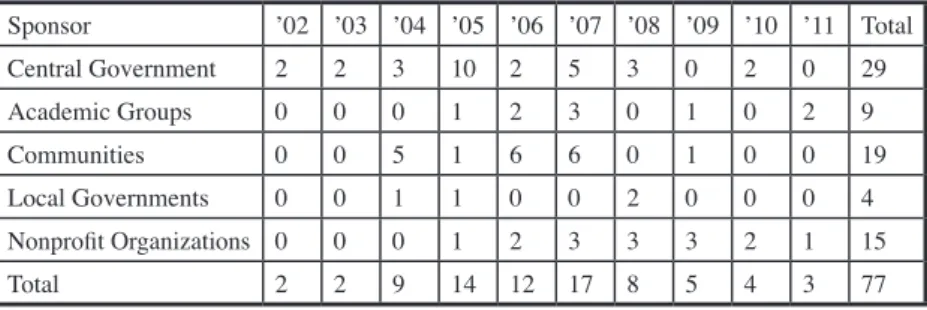

By 2008, the central and local governments had commissioned over twenty consensus conferences. The spirit of deliberative democracy was emphasized not only in Chen Shui-bian’s administration. After 2008, when the National Youth Commission stopped holding Youth National Affairs Conferences and the central and local governments commissioned fewer gatherings, there were relatively few conferences until 2012. Most were deliberative events held by nonprofit organizations and groups. However, in 2012, the Environmental Protection Administration of the Executive Yuan was the first to use the World Café model for a national deliberative conference. After the conference, Prime Minister Chun Chen stated that the World Café model, with its deliberative spirit was a tool suitable for resolving controversy in policies.44 At this time,

various sectors in Taiwanese society became interested in holding World Café conferences; there have been three such conferences to date. Table 3 shows that among the seventy-seven deliberative forums held before 2011, thirty-three were sponsored by the government. This means that, even though academic groups, communities, and nonprofit organizations have played important roles in promoting deliberative democracy in Taiwan, past trends indicate that government is still the primary motivator, whose intentions directly or 41 Huang, “After Deliberation.”

42 Tsai, “Technocracy, Democratic Participation, and Deliberative Democracy.

43 Huang, “After Deliberation,” and Lin, “State, Civil Society, and Deliberative Democracy.” 44 He-ying Tsai, “Prime Minister Chen Chun Recognizes the World Café Model,” Central News

Agency (2012), http://www.cna.com.tw/News/aALL/201206210123.aspx (accessed October

Table 3. Experiences in Holding Deliberative Democratic Conferences in Taiwan Sponsor ’02 ’03 ’04 ’05 ’06 ’07 ’08 ’09 ’10 ’11 Total Central Government 2 2 3 10 2 5 3 0 2 0 29 Academic Groups 0 0 0 1 2 3 0 1 0 2 9 Communities 0 0 5 1 6 6 0 1 0 0 19 Local Governments 0 0 1 1 0 0 2 0 0 0 4 Nonprofit Organizations 0 0 0 1 2 3 3 3 2 1 15 Total 2 2 9 14 12 17 8 5 4 3 77

Source: The Archives of Deliberative Democracy, http://140.116.67.117/d4/caseview. php?csid=6 (accessed October 29, 2012).

indirectly affect other sectors.

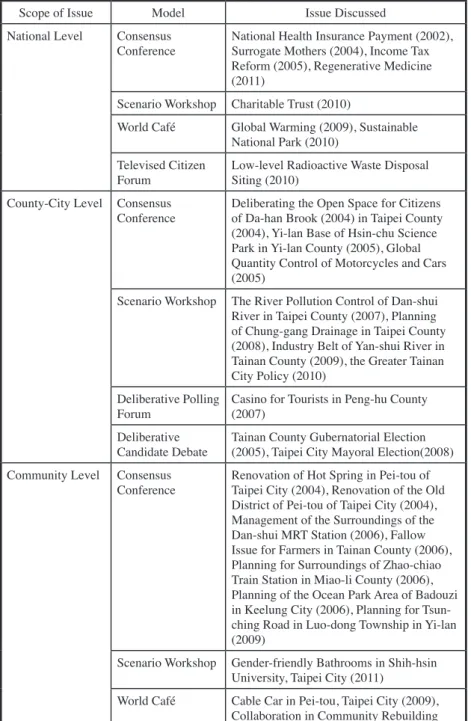

Table 4 classifies major forums according to the administrative level of the issue and the model employed. As illustrated in the table, there are several models employed in Taiwan at different levels to engage ordinary citizens, stakeholders, experts, and government officials in policy deliberations. Except for the deliberative campaign debate that was innovated in Taiwan, the other models are adapted from Western literature.45 Although the procedures of

different models vary in terms of their roles in the policy process, recruitment and number of participants, discussion format and length, and effects on policy, these models practiced in Taiwan distinguish themselves from traditional citizen participation in three respects. First, the recruitment of the participants is relatively open, which reflects the principle of fairness, emphasized by advocates of deliberative democracy. The number of participants varies from hundreds, such as in deliberative polling, to as few as a dozen, as in a consensus conference. Second, participants in these deliberative forums are better prepared than those in traditional public meetings because the organizers of the forums offer readable materials or hold expert sessions to equip participants with the necessary knowledge to engage in meaningful discussions on an equal footing. Last but not least, the forums are well-structured so that the expert knowledge and diversified values of stakeholders are incorporated into the process. Experienced facilitators are employed to conduct the meetings in order to maintain a sense of equality and meaningful dialogue and to realize the ideal of reciprocity.

Table 4 also lists the issues discussed in major deliberative forums held in Taiwan since 2002. According to the nature of the topics, they can be divided into national, county-city, and community levels. In different deliberative 45 Gastil and Levine classified these models into the consensus conference, national issues forum,

deliberative polling, citizen juries, and electoral deliberation. Their work also details the procedures of different models and illustrates them with specific cases. See Gastil and Levine,

forums, such as the consensus conference and the scenario workshop, citizens discuss controversial matters such as national health insurance, surrogate mothering, tax reform, and the selection of nuclear waste disposal sites. Some of the problems have been resolved (national health insurance and tax reform), while others (nuclear waste site selection and surrogate mothering) are still in dispute. County-level deliberation focuses mainly on environmental concerns, including river pollution and traffic control, as well as casino gambling. Meetings at this level also include general discussion on city or county development with candidates for county governor or city mayor. Community deliberation is closely concerned with spatial planning for specific areas. At the initial stage, Community Colleague invested great effort in facilitating these conferences. Also worth mentioning is the key role played by the Pei-tou Cultural Foundation, a grass-roots association supported by a local medical doctor, Der-ren Hong, who sponsored the consecutive consensus conferences held in the Peit-tou community.

Connection between Deliberative Democracy and Policy

Although Taiwan has abundant experience in deliberative practice, there are a limited number of cases that have affected policy. Discussions from three past conferences that have concretely affected policy have centered on surrogate mothers, National Health Insurance, and the I-lan Science Park. The first deliberative conference with clear policy effects was the consensus conference on surrogate mothers in 2004. Conference debate focused on “whether surrogate mothers should be permitted and legalized,” an issue that had been controversial for over ten years. The conference was held at the request of social groups and civic representatives and with the support of government officials.46 In

addition to having support from certain social groups and government sectors, the conference attracted much media attention due to its controversial nature, placing significant pressure on the government to respond. Ultimately, the conference affected the direction of policy.47 The other deliberative consensus

conference that influenced policy was the one on National Health Insurance in 2005. Even though Taiwan National Health Insurance has benefited Taiwanese people, it has been continuously under enormous financial pressure. It was hoped that the conference would illuminate the “problem of health insurance finances” and propose suggestions and views. Indeed, conclusions drawn from the conference were applied in subsequent policy planning.

The most classic case, however, was the 2005 Hsinchu Science Park I-lan Base consensus conference. Prior to holding this conference, the National Science Council had approved the “I-lan South Base” project, planned completion of the infrastructure at the base, and established a plan for the 46 Lin, “State, Civil Society, and Deliberative Democracy.”

Table 4. Deliberative Models and Issues Discussed (2002-2012)

Scope of Issue Model Issue Discussed National Level Consensus

Conference National Health Insurance Payment (2002), Surrogate Mothers (2004), Income Tax Reform (2005), Regenerative Medicine (2011)

Scenario Workshop Charitable Trust (2010)

World Café Global Warming (2009), Sustainable National Park (2010)

Televised Citizen

Forum Low-level Radioactive Waste Disposal Siting (2010) County-City Level Consensus

Conference Deliberating the Open Space for Citizens of Da-han Brook (2004) in Taipei County (2004), Yi-lan Base of Hsin-chu Science Park in Yi-lan County (2005), Global Quantity Control of Motorcycles and Cars (2005)

Scenario Workshop The River Pollution Control of Dan-shui River in Taipei County (2007), Planning of Chung-gang Drainage in Taipei County (2008), Industry Belt of Yan-shui River in Tainan County (2009), the Greater Tainan City Policy (2010)

Deliberative Polling

Forum Casino for Tourists in Peng-hu County (2007) Deliberative

Candidate Debate Tainan County Gubernatorial Election (2005), Taipei City Mayoral Election(2008) Community Level Consensus

Conference Renovation of Hot Spring in Pei-tou of Taipei City (2004), Renovation of the Old District of Pei-tou of Taipei City (2004), Management of the Surroundings of the Dan-shui MRT Station (2006), Fallow Issue for Farmers in Tainan County (2006), Planning for Surroundings of Zhao-chiao Train Station in Miao-li County (2006), Planning of the Ocean Park Area of Badouzi in Keelung City (2006), Planning for Tsun-ching Road in Luo-dong Township in Yi-lan (2009)

Scenario Workshop Gender-friendly Bathrooms in Shih-hsin University, Taipei City (2011)

World Café Cable Car in Pei-tou, Taipei City (2009), Collaboration in Community Rebuilding after Disaster, Kahsiung County (2009)

recruitment of companies for three predetermined sites in I-lan in 2005. However, the I-lan Community College held a consensus conference to initiate dialogue between the local people and the government. In the end, the National Science Council cited the outcome of this consensus conference as one of the reasons for changing the site and preventing technology manufacturing industries from entering I-lan. The high-pollution science park base finally left the San-sin Township of I-lan.48

Compared with the number of deliberative forums held over the past years, the number of forums that have had policy impact is limited. According to research that assessed the policy effects of the consensus conferences held between 2002 and 2006, political appointees and civil servants did not have confidence in deliberative forums because of their uncertainty and lack of expertise. In addition, civil servants were accustomed to a traditional top-down policy-making process, which heavily relied on the intensions of their superiors.49 The idea of deliberative democracy in Taiwan also spread to the

National Examination of Civil Services, when the term first appeared on the National Examination in 2005. Since then, there have been questions about deliberative democracy nearly every year, which means that the civil servants who are recruited by the government need to have a basic understanding of deliberative democracy and accept participation by the people. Accommodation of deliberative democracy is not deeply seeded in the minds of civil servants, however.

Deliberative Democracy, the Public, and Social Movements

Since its first implementation in Taiwan in 2002, the effects of deliberative democracy on various sectors of society have been reflected in academic research; Taiwan’s Youth National Conferences; national policy deliberative conferences held by the central government; consultations by local governments; the consensuses of community colleges concerning community development; and the deliberations of social organizations over policy. Furthermore, newspaper and magazine discussions over the years show that Taiwanese society as a whole has been influenced by deliberative democracy and consensus conferences. For example, table 5 shows that, between 2004 and 2006, when there were many citizen deliberation events in Taiwan, these events resulted in much reporting and discussion regarding the relatively novel ideas of deliberative democracy and consensus conferences. However, when the deliberative practice began to be guided by academia and social organizations 48 Ping-yi Kuo, “The National Science Council Abandoned Samsung Hong Chai Lin Site,” China

Times, January 17, 2007, 2. 49 Huang, “After Deliberation.”

in 2008, there was relatively less media reporting, but still a certain degree of exposure in newspapers.

Discussions of deliberative democracy have drawn a certain amount of attention from the public in Taiwan. The theory of deliberative democracy could (1) make up for insufficiencies in the representative democratic system; (2) provide a deliberative process through which to invite people to engage in rational policy discussion; and (3) offer a means to try to create public policy with greater legitimacy. Iris Young believes that, in the current mainstream representative system, even if social groups are incorporated into the deliberative mechanism, they are unable to effectively influence policy.50

Social activists argue that, in an unequal political structure, the path and output of deliberation is affected by advantaged groups and elites.51 Even though

deliberative democracy may offset the various problems of representative democracy, in the existing constitutional system, if the political power structure cannot be changed, the practice of deliberative democracy still will not alter the current situation of inequitable power distribution. Thus, the democratic models that follow deliberative norms will tend toward more powerful authorities. Dung-sheng Chen believes that, in addition to inequalities in the political structure, participation by socially advantaged people (such as the political elite, economically advantaged classes, experts, and scholars) exacerbates the unequal structure of the conference and, thus, also biases the conclusions of the conference toward the advantaged groups.52 Therefore, activists believe

that those promoting social justice should be more proactive in their opposition activity, rather than deliberate with people who support the existing power structure or benefit from it. In response to this line of argument, supporters of deliberative democracy posit that activists tend to be advocates of specific social issues. While they seek social justice, they cannot balance the various interests of different stakeholders in society and can achieve only partial social benefit. The theoretical tensions between social activists and deliberative democracy have been exhibited in the practice of deliberative democracy in Taiwan.

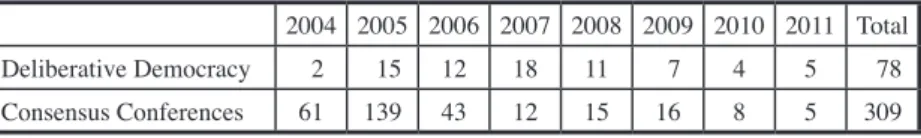

Table 5. Newspaper Reports in Taiwan on Deliberative Democracy (unit: piece)

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Total Deliberative Democracy 2 15 12 18 11 7 4 5 78 Consensus Conferences 61 139 43 12 15 16 8 5 309

Sources: Various newspaper databases.

50 Young, “Activist Challenges to Deliberative Democracy.” 51 Ibid.

The Challenge of Social-Movement Organizations to Consensus Conferences

When Taiwan first began to hold consensus conferences, participants from social-movement organizations questioned the “rationality,” “fairness,” and “openness” of this new form of citizen participation, qualms which strengthened after members participated in consensus conferences. Their doubts can be classified into three categories, explained under the following three subheadings.53

Expert Rationality vs. Social Movement Advocacy

Compared to the lay knowledge of the general public, expert knowledge has greater “empirical objectivity” and “logical validity.” Lay knowledge frequently is accumulated from experiences in daily life, and it is more difficult for the public to use precise words and logic for discourse, tending instead toward expressions that are sensational or emotional. Conversely, expert knowledge, which is the outgrowth of professional training and long-term research, tends to be more persuasive. Thus, even when public social-movement organizations have a few experts in the group on specific concerns, it is difficult for the organizations to train all members as proficient experts. As described by Young, the main characteristic of activist social-movement organizations is to use action to oppose the political structure;54 in other words, during the early

stages of deliberative democracy in Taiwan, social-movement organizations that were adept at street demonstration advocacy found it difficult to effectively participate in conferences or even to trust the output from conferences affected by the structure and government officials.

Reluctance to Endorse Government Policy

A few case studies in Taiwan have shown that social-movement organizations have questioned why government officials have held consensus conferences to seek endorsement from the people.55 In a society which strongly favors

development, when the government engages in policy discourse about major public construction that can stimulate economic growth, the public often is unable to resist the seduction of the benefits of the economic policy. Social-movement organizations (especially environmental conservation groups) question whether government departments gain an advantage in opinion polls by hosting consensus conferences. With the aim of winning greater popular support for developmentalist policies, consensus conferences may be held through certain procedures to sample participants56 and to build support

53 Tsai, “Technocracy, Democratic Participation, and Deliberative Democracy.” 54 Young, “Activist Challenges to Deliberative Democracy.”

55 Tsai, “Technocracy, Democratic Participation, and Deliberative Democracy.”

56 This case is the Cable Car Consensus Conference in 2004. The local environmental group,

TANGO, charged that the executive team of the consensus conference had been biased in the selection of participants and had manipulated the conclusions of the conference. It asked for

for a predetermined policy. Thus, when social-movement organizations see that government departments act this way, they criticize the government for avoidance of direct dialogue with the social-movement organizations and for procedural manipulation to gain support from the people. The few social activists who participate in a consensus conference might be trapped into becoming endorsers of the government’s policy, thus helping the government to achieve policy legitimacy.

Conference Agendas: Procedures, Organizers, and Time Constraints

The third reason why social-movement organizations doubt deliberative democracy is the design of conference agendas. In early consensus conferences, most people did not understand the procedures or even the democratic meaning of such conferences, thus they were unable to proficiently participate in deliberation. As a result, many participants responded that the time for a conference was too short and raised doubts about the host who led it.57

Definitive discussion of issues, the limited timeframe for deliberation, and effective control over the topic of discussion are meant to enhance effective communication and dialogue, but this is premised on the attendance of participants who are familiar with the agenda and issues. However, most people, including members of social movements who are familiar with these matters, have incomplete knowledge of the nature and procedures of deliberative events. Therefore, unless there is in-depth, advance knowledge of the procedures and the issues, one is unable to proficiently express individual opinions and criticism. This situation tends to occur when the participants have backgrounds that are very different, resulting in variations in the time to express ideas and the persuasiveness of content, in turn, affecting the conclusions of the conference.58

In response to the suspicion of social activists, advocates of deliberative democracy have incorporated the representatives of social groups into deliberative mechanisms. In organizing deliberative conferences, in order to balance diverse positions regarding the issue under discussion, event organizers have invited leaders of different social groups to serve on the steering committees and as panel experts. They also have taken care to ensure that leaders of social groups help to supervise the framing of the issue to be discussed, develop readable materials and the conference agenda, and recruit participants, with the hope to achieve fair participation, elicit diverse opinions, and gain the trust of various sectors of society. In addition, community colleges, which have close ties with activist groups, have committed great effort to promoting the

reselection of the participants; however, being refused, its representatives resigned from the executive committee. From Chen, “The Limits of Deliberative Democracy,” 96.

57 Tsai, “Technocracy, Democratic Participation, and Deliberative Democracy.” 58 Chen, “The Limits of Deliberative Democracy.”

idea of deliberative democracy and practicing different deliberative models. The period between 2004 and 2008 was a lively time for community colleges in holding deliberative democracy events. Social-movement organizations began to hold deliberative conferences in 2006. Each year, there were similar meetings in the expectation that the deliberative model would create a communication platform for diverse stakeholders, while also improving the people’s impression that social-movement organizations were simply radical. In 2012, social-movement organizations proactively participated in the World Café, held by the Environmental Protection Administration. Overall, tensions between social activists and deliberative democracy seem to be moderate in Taiwan, and there is collaboration between these two forces.

Taiwan’s Deliberative Democracy in Comparison and Its Challenges

East Asia consists of societies deeply influenced by Confucian culture. How is it likely to be influenced by a brand new democratic theory from the West? How will deliberative democracy manifest itself in the contexts of different political systems and social cultures? How can other Chinese societies learn from the unique Taiwan experience in its comparison to other cultures?

Previous discussion shows that the development of deliberative democracy in Taiwan was rooted in a particular political context under which the new ruling DPP party pursued legitimacy at constitutional, representative, and governance levels. Academia played a key role by introducing the theory and mechanisms from Western society and by acting as a facilitator in promoting the practice of the novel forms of deliberative democracy. In the initial stage, the government commissioned academic communities to hold deliberative conferences. Then, the government held national conferences. In recent times, social and academic groups have carried the torch by holding the conferences, continuing the deliberative practice in Taiwan. There has been a wide range of discussions, including at the national, county, city, community, campus, and youth levels.59 The models have been spirited and diverse, including consensus

conferences, scenario workshops, group forums, study circles, online citizens’ forums, open spaces, deliberative debates, and world cafés. Taiwan has a varied and lively political culture and a social context with various views that coexist. This open society permits experiments with different models as well as the innovation of new models, such as group forums and deliberative debate.

Compared to the liberal and pluralistic society of Taiwan, China is relatively limited in terms of practicing deliberative democracy, since there are restrictions on freedom of assembly and deliberative events are mainly 59 Chun-sung Liao, “A Comparative Study of Deliberative Democracy between Taiwan and

Mainland China,” paper presented at the Third International Conference on Public Management in the 21th Century: Opportunity and Challenge, October 2008, University of Macau, Macau.

top-down promotions by the government.60 China’s practice of deliberative

democracy began later than in Taiwan. The first deliberative conference was the consideration by Zeguo Township in Zhejiang about how to use its construction funding.61 Compared to Taiwan, the scope of issue discussion

is narrower, and has witnessed practical experience at only the township, community, and campus levels. Currently, the Chinese models include the “consultation conference,” “deliberative polling,” “citizen juries,” and the “project panel.”62 The Chinese experience shows that, even though China is

less socially liberal than Taiwan, it seems to have an advantage over Taiwan in effectively implementing deliberative conferences because authoritarian power can force participation;63 consequently, the sample error is reduced

due to the greater representativeness of conference participants. However, the process has been exposed to the peril of manipulation, which is detrimental to the very foundation of deliberative democracy.

Hong Kong and Macau have recently attempted to introduce the deliberative democracy model to resolve problems in public affairs. The first practice of deliberative democracy in Macau was a public consultation meeting in 2010 to confer with people about the reclaimed area in Xincheng.64 This meeting and

deliberative polling show that the practice of deliberative democracy in Macau currently is the same as in China, which is primarily a top-down operational model, with the government as initiator and consideration of only topics related to regional issues. In comparison with China and Macau, Hong Kong is still in the evaluation stage and has not actually promoted deliberative practice.65 In

2011, it held the first workshop on “deliberative democracy, public opinion, and deliberative polling,” in which scholars organized an international academic conference to further consider deliberative democracy.66 The Macau media has

published reasons why Hong Kong is currently unable to promote deliberative practice. It speculates that, in Hong Kong social culture, young people use primarily the Internet to express their opinions or to protest in the streets, and rarely are willing to participate in face-to-face meetings. Thus, it is difficult to 60 Ibid.

61 Bao-gang Ho, Deliberative Democracy: Theory, Method and Practice (Beijing: China Social

Science Publisher, 2008).

62 Ibid.

63 Yi Tseng, “Can Deliberative Democracy Modify the Crisis of Representative Democracy?” Macao Daily, August 3, 2011, E06.

64 Direcção dos Serviços de Solos, Obras Públicas e Transportes [Land, Public Works and Transport

Bureau of the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China] http:// urban planning.dssopt.gov.mo/cn/new_city01.php (accessed October 29, 2012).

65 “Plans to Introduce Deliberative Polling to Hong Kong,” Hong Kong Economic Journal (June

2011), http://cdd.stanford.edu/polls/hongkong/ (accessed October 29, 2012).

66 Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, http://esc.nccu.edu.tw/modules/tinyd8