合作式翻譯學習任務設計研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Design-Based Research on Developing Cooperative Translation Tasks. A Dissertation Presented to Department of English,. 立. 政 治 大. National Chengchi University. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Hui-chuan Wang June, 2010.

(3) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to the following individuals who have assisted me in finishing this dissertation. I am grateful for the tremendous support that I have received from my esteemed advisors, Dr. Yan-hao Chen and Dr. Chin-chi Chao, throughout my doctoral career. They have treated me as family and taught me much, not only about my dissertation, but also my academic career, health, and life. Their support gave me the strength and confidence to complete my work. My appreciation also goes to all my committee. 政 治 大 suggestions to make this study better, Dr. Hui-zung Perng, Dr. Yuan-shan Chen, and 立. members for the meticulous attention they devoted to my manuscript and thoughtful. ‧ 國. 學. Yi-Ping Huang.. Special thanks go to Dr. Charles Ruey-tsuen Chang, who believed in my potential. ‧. and encouraged me to pursue a doctoral degree. I also wish to extend my appreciation. Nat. sit. y. to my colleague and good friend, Feng-mei Doris Chao, for her participation as. n. al. er. io. another translation teacher in my study, and Dr. Wen-chi Vivian Wu, and Ling-ling. i Un. v. Yen at Providence University for their research suggestions and counseling. My. Ch. engchi. thanks also go to my classmates Cher and Michael for their continuous encouragement throughout the study and support in my proposal defense. Finally, I would like to thank my parents and parents-in-law for their help with family responsibilities so that I could devote my time to this study. My gratitude also goes to my husband, Chi-Wei Yang, for keeping me happy and allowing me not to worry about money. His love gave me the strong belief that I could finish this study. My last thanks go to my pet, a ferret, Mei Mei, for accompanying me continuously when I sat at my desk, working on this study. I hereby dedicate this dissertation to my family. iii.

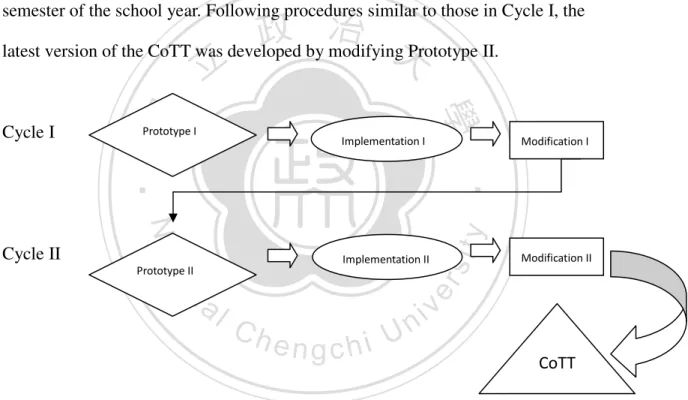

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement……………………………………………………………...... iii. English abstract ………………………………………………………………...... ix. Chinese abstract………………………………………………………………….. xi. CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION……………………………………….……. 1. Background of the Study…………………………………………………… 1 Purpose of the Study....................................................................................... 6 Research Questions......................................................................................... 6. Definition of Terms......................................................................................... 7. Significance of the Study................................................................................ 9. Organization of the Present Study….............................................................. 10. 政 治 大 Research on Translation Teaching………..................................................... 立 Cooperative Learning……………………...................................................... CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW…………………………………….. 12. 學. ‧ 國. 12 21. Peer Response................................................................................................. 29. Design-based Research (DBR)………........................................................... 37. ‧. 45. CHAPTER THREE ETHODOLOGY………………………………………….... 47. y. Nat. Summary of Chapter 2………………………................................................ Design of the Study......................................................................................... 55. er. sit. 47. io. Design of the Cooperative Translation Task (CoTT)...................................... al. n. iv n C Cycle I…………………………………………………………… hengchi U. Design Procedures…………………………………………………… 55 56. Cycle II…………………………………………………………... 59 Differences in the Design between Cycle I and II……………….. 62. Analysis of Data……………………................................................... 64 Summary of Chapter 3.................................................................................... 66. CHAPTER FOUR IMPLEMENTATION OF PROTOTYPE I OF THE CoTT… 67 Pre-presentation Stage.................................................................................... 68 Presentation Stage........................................................................................... 80. Post-presentation Stage................................................................................... 110. Summary of Chapter Four………………………………………………….. 118. iv.

(5) CHAPTER FIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROTOTYPE II OF THE CoTT… 120 Pre-presentation Stage.................................................................................... 121 Presentation Stage.......................................................................................... 125 Post-presentation Stage................................................................................... 144. Summary of Chapter Five…………………………………………………... 147. CHAPTER SIX DISCUSSION …………………………………………………. 150. Domain Theories…………………………………………………………… 150 Nature of Learners…………………………………………………….. 151. Nature of Teachers…………………………………………………….. 170. Nature of Learning Setting..…..………………………………………. 171 Nature of Interaction…..……………………………………………… 172 Design Framework…………………………………………………………. 179. 政 治 大 Session 1: Written Peer Response…………………………………...... 立. The Latest Cooperation Translation Task and Design Framework……….... 190 190. Session 2: Student Seminars and Teacher Seminar………...…………. 192. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Session 3: Translator’s Sharing of Collected Comments……………... 193 Session 4: Oral Peer Response…………………………………........... 196 Session 5: Oral Teacher Response…………………………………..... 198 Session 6: Final Revisions…………………………………………….. Nat. y. 199. sit. Summary of Chapter Six…………………………………………………… 201. al. er. io. CHAPTER SEVEN CONCLUSION……………………………………………. 203. v ni. n. Main Findings of the Present Study……………………………………........ Ch. engchi U. 203. Implications………………………………………………………………… 213 Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research………………………..... 220. Conclusions………………………………………………………………… 221 REFERENCES…………………………………………………………………... 223 APPENDIX …………………………………………………………………........ 235. Appendix A: The Teaching Guidelines of MOE’s English Translation I……….. 235. Appendix B: Consent Form……………………………………………………... Appendix C: A Sample of Student-chosen Story for Translation………………... 236 237. Appendix D: Peer Response Sheet……………………………………………..... 238 Appendix E: Language Level Checklist…………………………………………. 239. Appendix F: Post-Task Survey…………………………………………………... 242. Appendix G: Seminar Sheet for Individual student…………………………….... 245. v.

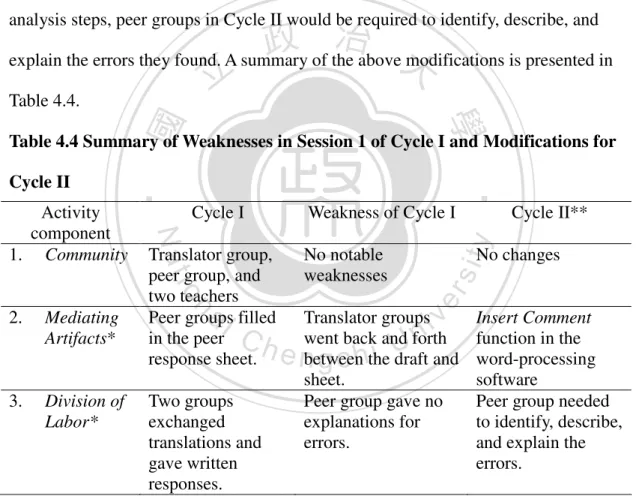

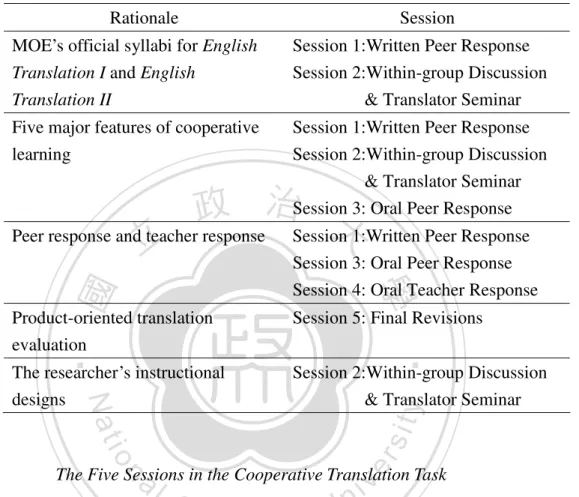

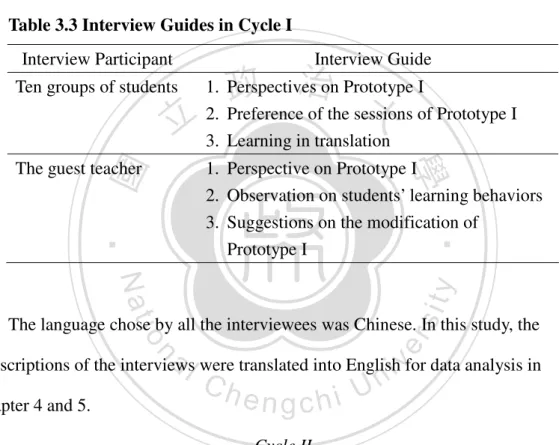

(6) LIST OF TABLES. io. y. al. n. Table 6.1 Table 6.2 Table 6.3 Table 6.4. Nat. Table 5.1 Table 5.2 Table 5.3 Table 5.4. ‧. Table 4.9. 學. Table 4.8. 立. sit. Table 4.7. 政 治 大. er. Table 4.5 Table 4.6. Summary of the Rationales of the CoTT and Its Application……… The Five Sessions of the CoTT in Three Stages…………………… Interview Guides in Cycle I………………………...…………….... Interviews Conducted in Cycle II………………………………….. Five Sessions of the Prototype I of the CoTT in Three Stages…….. Descriptive Statistics of Written Peer Response…………………… Example of the Response Method…………………………………. Summary of Weaknesses in Session 1 of Cycle I and Modifications for Cycle II………………………………………............................. Five Roles and the Responsibilities………………………………... Summary of the Weaknesses in Session 2 of Cycle I and the Modifications for Cycle II………………………………………...... Summary of Weaknesses in Session 3 of Cycle I and Modifications for Cycle II………………………………………............................. Summary of Weaknesses in Session 4 of Cycle I and Modifications for Cycle II………………………………………............................ Summary of Weaknesses in Session 5 of Cycle I and Modifications for Cycle II………………………………………............................. Five Sessions in Cycle I and Cycle II…………………………........ Descriptive Statistics of Peer Response by Each Group……............ Seminar Sheet for Students………………........................................ Summary of the Modifications in the Five Sessions and Remaining Problems…………………………………………………………….. ‧ 國. Table 3.1 Table 3.2 Table 3.3 Table 3.4 Table 4.1 Table 4.2 Table 4.3 Table 4.4. Ch. engchi. i Un. 52 53 59 62 67 72 77 79 88 96 104 110 117 120 123 134. v. 149 Summary of the Characteristics of Learners...................................... 163 Summary of the Emerging Issues...................................................... 169 Seminar Sheet for Individual Student (simplified version)………… 185 Six Sessions of the Latest Version of the CoTT………................... 190. vi.

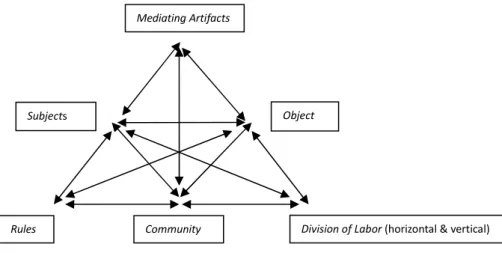

(7) LIST OF FIGURES. ‧. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. Figure 6.6 Figure 6.7 Figure 6.8 Figure 6.9 Figure 6.10 Figure 6.11. 學. Figure 6.1 Figure 6.2 Figure 6.3 Figure 6.4 Figure 6.5. 立. 政 治 大. er. Figure 4.4 Figure 4.5 Figure 4.6 Figure 4.7 Figure 4.8 Figure 5.1. Flowchart of the Design Procedures Components of the Activity System……………………………… Activity System…………………………………………………... Session 1 in Activity System……………………………………... Flow of Written Peer Response Activity and the Use of Peer Response………………………………………………………….. Session 2 in Activity System……………………………………... Movement Pattern Chart for Translator Group…………………… Session 3 in Activity System……………………………………... Session 4 in Activity System……………………………………... Session 5 in Activity System……………………………………... Differences in Movement Pattern for Simulated Seminar in Cycle I and Cycle II……………………………………………………... Learners’ Use of Peer Response and Teacher Response………….. Factors to Influence Face-to-face Student-student Interactions…. Students’ Mixed Feeling Toward or Away from the Teacher……... Learners’ Review System…………………………………………. Latest Version of Training of Giving Description and Explanation Session……………………………………....................................... Latest Version of Written Peer Responses Session………………... Movement Pattern for Student Seminar…………………………... Latest Version of Student Seminar & Teacher Seminar Session….. Latest Version of Translator’s Sharing of Comments Session……. Latest Version of Oral Teacher Response Session………………... Latest Version of Final Revision Session………………………….. ‧ 國. Figure 3.1 Figure 3.2 Figure 4.1 Figure 4.2 Figure 4.3. Ch. engchi. vii. i Un. v. 55 65 68 69 76 81 91 97 105 112 127 165 166 167 168 192 193 194 196 197 199 200.

(8) LIST OF PICTURES E-classroom in Cycle I…………………………………………… E-classroom in Cycle I....………………………………………… Classroom with One Lectern and One Microphone in Cycle II…... 立. 政 治 大. 學 ‧. ‧ 國 io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Picture 3.1 Picture 4.1 Picture 5.1. Ch. engchi. viii. i Un. v. 57 101 136.

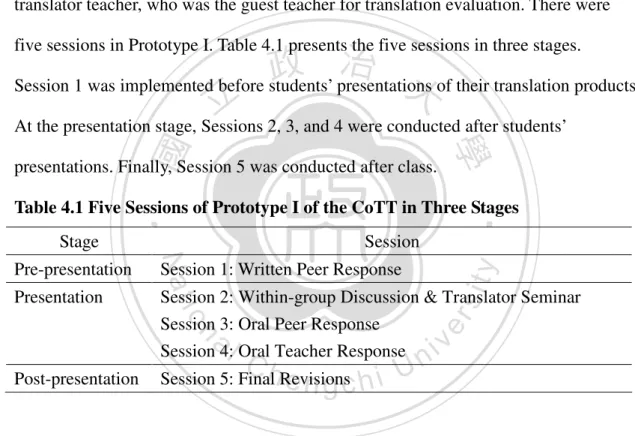

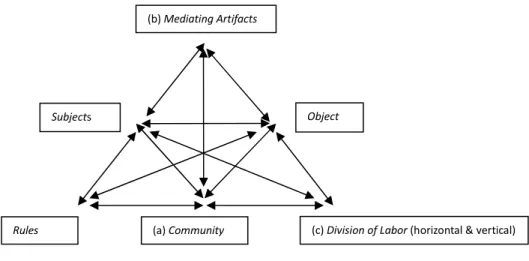

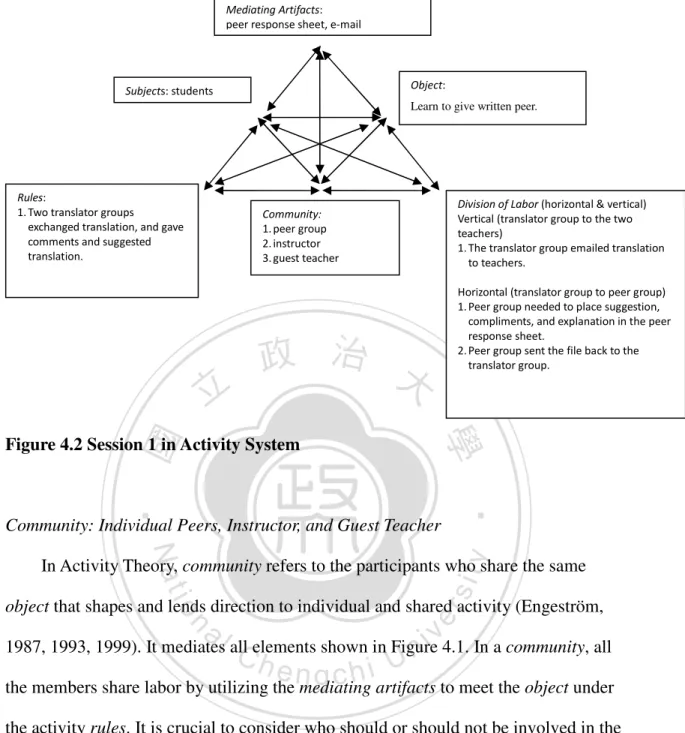

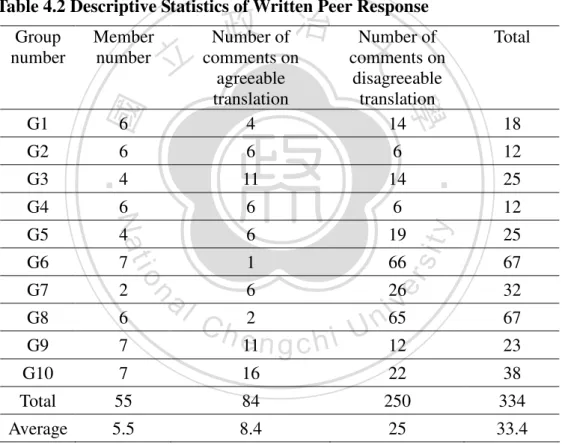

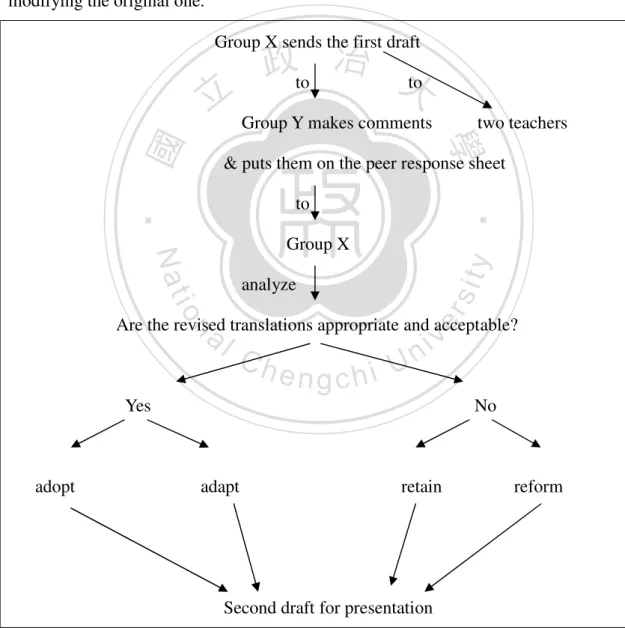

(9) ABSTRACT For the past decade, translation learning has been one of the main foci for university language learners, but a number of studies have found that many translation teachers still utilize traditional translation teaching methods (Chang, Yu, Li & Peng, 1993; Dai, 2003; Mu, 1992). In traditional classrooms, students tend to depend heavily on teacher-centered instruction, and teachers accept or encourage the students’ passive learning attitudes (Kiraly, 1995). As a result, students only follow the teachers’ suggestions and rarely reflect up their own translating process, translation styles, and problem-solving approaches. The goal of this study was to design a translation learning task called the Cooperative Translation Task (CoTT). It was achieved in three phases: (a) the initial design of the CoTT; (b) the implementations of two prototypes of the CoTT and (c) the finalized CoTT. The current study followed a design-based research (DBR) framework to clarify the complicated interactions in an authentic learning environment. In total, there were five sessions in Prototype I:Session 1: Written Peer Response; Session 2: Within-group Discussion & Translator Seminar; Session 3: Oral Peer Response; Session 4: Oral Teacher Response; and Session 5: Final Revisions. The student participants in both cycles were technological university students, including 56 students in Cycle I and 25 in Cycle II. Two translation teachers participated in the study. For data collection, triangulation data were collected, including videos, interviews, and student documents. The data was put into the framework of Activity theory to diagnose implementation problems in terms of community, division of labor, and mediating artifacts, and innovations with solutions were provided. Following the second prototype, the latest version of the CoTT has been constructed. In Session 1, training in describing and explaining errors is conducted. In Session 2, a peer group gives written responses for the translator group to make revisions. To encourage students to give explanations to their own peers, individual accountability is included. The peer group uses the Comment function in the word-processing software to identify, describe, and explain the agreeable and disagreeable translations. In Session 3, a student seminar and a teacher seminar are conducted simultaneously. To help students take organized notes on the results of their discussions, and to prevent students from not accepting responsibility in the discussions, an individual seminar sheet is given to each student. The teacher seminar finishes earlier than the student seminar so that the members can return to the original seminar and share the teachers’ suggestions with the group. In Session 4, the translator group needs to present the comments from each seminar. In Session 5, the. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. ix. i Un. v.

(10) two teachers can use multiple criteria for error analysis. In Session 6, translator members use the Comment function in the word-processing software to insert collected comments, their acceptance level, and the reasons why they accept or reject each suggestion. Each group needs to turn in the final product, one copy with and one without the comments, to the instructor. The present study has found that students have a tendency to trust and use the teachers’ comments. However, this distrust of peers’ review increased students’ autonomy. Students underwent a process of analysis of the suggested translations and reformation of the translation. The influential factors in student-student interaction are an Asking and Answering communication mode and Acquaintance (2A), and students’ values in peer response. When giving a linguistic-level evaluation, students provided the most comments on mechanics, then comments vocabulary and sentences. As for the types of responses, they focused mainly on the identification of translations, provision of suggested translations, and some compliments on agreeable translations. They seldom gave explanations for either agreeable or disagreeable translations. The present study has both its theoretical and practical implications. This design-based study offers three kinds of theories: domain theories, a design framework, and design methodologies. The CoTT and its six sessions provide translation teachers an alternative way to teach, especially for teachers trained in other professions.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i Un. v.

(11) 中文摘要. 過去十年,翻譯學習已成為外文系大學生學習的重點之一,但是許多研究發 現教師仍使用傳統的翻譯教學法。在傳統的教室,學生過度依賴以教師為中心的 學習,教師本身亦接受或間接鼓勵被動的學習方式。學生只想聽取教師的建議, 而鮮少了解自己的翻譯過程、翻譯風格及自我解決問題的方法。 本研究的目的在設計一個翻譯學習活動:「合作式翻譯任務」。此設計經過 三個階段:(一) 初步設計;(二) 施實「合作式翻譯任務」的二個原型;(三) 完 成合作式翻譯任務的設計。本研究採用設計本位研究方法 (Design-based research. 治 政 method),並試圖對真實學習情境作深入地了解。在原型(一)共有五個活動:活 大 立 動一為書面同儕回饋、活動二為組內討論及翻譯者研討會、活動三為口頭同儕回 ‧ 國. 學. 饋、活動四為口頭教師回饋、活動五為最終校正。. ‧. 研究的參與者為科技大學的外語系學生,在第一循環共有 56 位學生參加,. sit. y. Nat. 在第二循環有 25 位學生參加,另有二位翻譯教師參與此研究。本研究採用三角. io. er. 測量研究法 (triangulation) 來收集資料,包含影片、訪談及學生的翻譯文本等。 研究分析的工具為「活動理論」 ,並從社群、分工、媒介三方面進行分析,以尋. n. al. 求可能解決設計問題的方法。C h. engchi. i Un. v. 經過二個原型的實施,本研究設計出「合作式的翻譯任務」 。活動一為訓練 學生描述及解釋翻譯錯誤的能力。活動二為個人的書面同儕回饋,學生需使用文 書處理軟體中的「新增註解」功能給予回饋。活動三為學生研討會及教師研討會。 每位學生需記錄自己在研討會的討論結果。教師研討會的時間較短,以便讓與會 的學生回學生研討桌分享研討的結果。活動四為學生翻譯員上台分享在學生研討 會中得到的回饋及達成的共識。活動五為二個教師給予口頭回饋。活動六為學生 使用「新增註解」註明所收集到的回饋、是否接受建議及理由。每組需交出一份 校正後的翻譯,及附有註解的檔案。. xi.

(12) 研究發現學生較相信教師的評語,但是對同儕評語的不信任卻增加學習自主 性。學生經分析同儕建議的翻譯、重組或修改後才採用。影響學生互動的因素為 問答的溝通模式、同儕間的熟悉度及對同儕回饋的信念。學生的回饋方式傾向於 找出有問題的翻譯、提供建議的翻譯及給予讚許。但他們很少給予針對自己的評 語作解釋。 本研究提供理論上及實務教學的建議。在理論方面,本研究提出三種理論: 領域理論、設計框架、及設計實施方法。在實務教學方法,合作式翻譯任務提供 翻譯教師另一種教學模式,以期達到最佳的教學成效。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xii. i Un. v.

(13) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. Background of the Study Motivation Five years ago, I started to teach translation, even though I had majored not in that area, but in English teaching. Without knowing much about translation studies, I focused on the textbooks and tried to provide a variety of language exercises, such as sentence-level translation and vocabulary memorization. However, I suffered. My. 治 政 students got bored with language-based translation assignments 大 and expected me to 立 provide so-called ‘ideal’, ‘perfect’ or ‘correct’ translation products. I spent a lot of ‧ 國. 學. time correcting their work, but found that my students did not really improve.. ‧. Also, I found that I could not give either language or translation instructions. sit. y. Nat. effectively. When I focused on language learning, translation strategies seemed to be. io. er. neglected. If I emphasized translation theories, the course was fairly boring because. al. most of the time was spent on translation textbooks. According to Dai (2003), around. n. iv n C 80% of translation teachers studiedh other areas, such as e n g c h i UTESOL, literature, or. linguistics. Therefore, many translation teachers confront similar difficulties in knowing what to teach and how to teach. With translation textbooks in hand, most of these teachers can solve the problem of what to teach, but the problem of how to teach still exists, especially since little research has been done on translation pedagogy. One may say that language teachers can just shift the language pedagogy to a translation one. However, learning translation is actually much more complicated than learning a single language skill. Kelly and the AVANTI research group (2007) have shown the complexity of translation competence in their categorization. The translator needs to have communicative and textual competence in two languages and cultures, 1.

(14) to be familiar with subject areas and the instrumental tools for using resources, to hold a serious attitude toward translation work, to cooperate with others such as fellow translators, and to use appropriate translation strategies. From these sub-competences, it can be easily found that translation competence is not just the ability to transfer meaning between two languages. Language pedagogy, which focuses only on language learning, may not meet instructional needs for the development of translation competence. Due to my continuous interest in teaching translation, over the past five years, I have experimented with various instructional designs in my class and observed my. 治 政 students’ learning attitudes toward them. The results of大 these studies in 2007, 2009, 立 and 2010 will be discussed in Chapter 2. From these studies, I found that it was ‧ 國. 學. important to consider class dynamics and student interactions. Students were more. ‧. involved in class when they had a chance to discuss their work with their peers or. sit. y. Nat. with me, especially when they were assigned roles for translation criticism. However,. io. er. the instructional designs of these studies were not integrated into a complete and. al. systematic translation task for teachers to employ. Therefore, in order to design a. n. iv n C motivating, student-centered translation as well as to help translation teachers h e nclass, gchi U solve the problem of how to teach, I decided to design a cooperative translation task for translation teachers. Current Translation Education Scheme In recent years, English teaching and learning have been getting considerable attention in Taiwan. Among all the areas of language learning, translation is one of the educational goals set by the government. In the Executive Yuan’s proposal to create an English environment, one main goal is to cultivate professional translators, and universities and colleges have been encouraged to train students to be competent translators. To meet this need, since 2003, the MOE has included English Translation 2.

(15) I and English Translation II as core courses for students majoring in applied English/foreign languages to develop their translation competence. Furthermore, the MOE has administered a Chinese and English Translation and Interpretation Competency Examination since 2007 and has attempted to build a database of translators by enlisting the examinees who have passed the exam. It seems clear that the MOE is attempting to develop more professional translators and reduce the shortage in translators. A closer look at the MOE’s official syllabi and guidelines in English Translation I and English Translation II reveals that the MOE suggests a variety of learning. 治 政 activities for teachers to utilize in the classroom, including 大 (1) group discussion and 立 presentation, (2) peer correction, (3) error analysis, (4) translation criticism, and (5) ‧ 國. 學. comparative analysis. These activities seem to share two main features. First, they. ‧. encourage more interaction and cooperation among students through such activities as. sit. y. Nat. group discussion and peer correction. Second, problems are not identified by the. io. er. instructor alone, but also through students’ error analysis, translation criticism, and. al. n. comparative analysis. In other words, to foster students’ abilities in translation. i n analysis and review is one main C learning objective. U hengchi. v. Although for the past decade, translation learning has been one of the main foci for university language learners, a number of studies have found that many translation teachers still utilize traditional translation teaching methods (Chang, Yu, Li & Peng, 1993; Dai, 2003; Mu, 1992). In traditional classrooms, students tend to depend heavily on teacher-centered instruction, and teachers accept or encourage the students’ passive learning attitudes (Kiraly, 1995). As a result, students only follow the teachers’ suggestions and rarely reflect up their own translating process, translation styles, and problem-solving approaches. 3.

(16) Moreover, teacher- and text-centered, and writing-based, teaching methods are implemented without considering class dynamics and student interactions (González Davies, 2004). There are almost no interactions between the teacher and students and among students. Even worse, because of the students’ inherent belief in the teacher’s authority, students only trust the teachers’ evaluations and ignore the importance of peer responses. Teachers become the providers of a ‘perfect’ or ‘correct’ translation, which simply does not exist in the real world. Students do not work toward developing a text that is consistent and coherent, adequately meets the initiator’s or the target reader’s expectations, and communicates the original message efficiently. 治 政 (González Davies, 2004), but instead expect and receive 大rigid answers from teachers. 立 With the increasing importance of translation learning, and the need for a ‧ 國. 學. systematic method to incorporate the various teaching techniques suggested by the. io. er. Theoretical Background. sit. y. Nat. teachers.. ‧. MOE, it is necessary to develop an alternative teaching approach for translation. al. In the past two decades, translation work has undergone a dramatic change. Zhou. n. iv n C (1997) pointed out that translation is customer-oriented, taking hgetting e n gmore chi U. customers’ needs as priorities; therefore, communicative translation has been emphasized. Today’s translators need to choose the final products and translation techniques by considering the effects on the users of the translation. However, traditional translation instruction still focuses on transferring from one language to another; therefore, translation learning may be incomplete and fragmentary (Kiraly, 1995). According to Ulrych (2005),. 4.

(17) The way translation is taught has important implications for students’ future professions as translating is no longer carried out in isolation. …A further component of professional translation is the development of client-related skills in establishing sound interpersonal relations with authors, publishers, and requesters. It was therefore encouraging to see that teacher/student and student/student interaction featured prominently in the translation classroom. (p. 15) With the changes in translation work and the need to develop students’ communicative translation competence, more and more translation scholars and teachers have called for alternative methods of translation instruction. Colina (2003). 政 治 大 which has underlying philosophies resembling those of Communicative Language 立 and Kiraly (1995, 2000) advocated Communicative Translation Teaching (CTT),. ‧ 國. 學. Teaching (CLT). The main instructional goal for communicative translation teaching is to cultivate students’ communicative translation competence and to emphasize the. ‧. social contexts of texts. Consequently, CTT requires not only communicative. Nat. sit. y. competence in L1 and L2, but also cross-language and cross-culture communicative. n. al. er. io. competence (Colina, 2003). To build up communicative translation competence,. i Un. v. teachers need to integrate multiple tasks, cooperative learning, peer tutoring, and authentic materials.. Ch. engchi. Cooperative learning, which is essentially social in nature, can be applied to translation classes, as translation is counted as cross-language and cross-culture communicative competence (Colina, 2003). However, few studies have attempted to apply cooperative learning to translation. With the need to develop students’ communicative translation competence for future profession, this study aims to develop a cooperative translation task for translation teachers.. 5.

(18) Purpose of the Study The purposes of this study were twofold. First, this study aimed to help translation teachers decide how to teach and to provide them with a feasible task to directly adopt or adapt to their own classrooms for effective teaching. The second purpose was to propose an alternative teaching approach in translation pedagogy and thus solve some problems in the traditional translation classroom. In order to explore the feasibility of the Cooperative Translation Task (CoTT), the current study followed a design-based research (DBR) framework to clarify the complicated interactions in an authentic learning environment through two cycles of. 治 政 implementation. This study addressed the following research 大 questions. 立 Research Questions ‧ 國. 學. The primary research questions to be addressed in this study were as follows: What were the results of implementing the first prototype of the Cooperative. ‧. 1.. sit. y. Nat. Translation Task (CoTT)?. io. al. er. a. What were the results when Prototype I was implemented in Cycle I?. n. b. How did the results from Cycle I facilitate the modification of Prototype I for Cycle II? 2.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. What are the results of implementing the second prototype of the Cooperative Translation Task (CoTT)? a. What were the results when Prototype II was implemented in Cycle II? b. How did the results from Cycle II facilitate the modification of Prototype II for the latest version of the CoTT?. 3.. What was the latest version of the CoTT, following the second prototype and its implementation guidelines?. 6.

(19) Definition of Terms With the circular implementation and modification of the CoTT, new terms emerged to replace the previous ones in the process. To distinguish the differences among similar terms, the definitions of the following terms are provided. 1.. Task, Session and Step: A task is “a chain of activities with the same global aim and a final product. The full completion of a task usually takes up several sessions (González Davies, 2004, p.23),” and a session consists of several steps. Written Peer Response: This is a session conducted by a peer group outside. 治 政 the classroom. This group has to not only identify 大 agreeable and 立 disagreeable translations but also provide suggested translations for further 學. ‧ 國. 2.. revisions.. Oral Peer Response: This is a session conducted by a comment-giver group. ‧. 3.. sit. y. Nat. in class. This group has to orally point out agreeable and disagreeable. io. er. translations, and provide explanations. Giving suggestions is optional,. al. n. which is different from the written peer response. Suggested translations are. ni C hresponses. obligatory in written peer U engchi 4.. v. Oral Teacher Response: This session is conducted by the teachers in class only after Oral Peer Response has been completed so that the students will not simply repeat the teachers’ comments in the peer-response session. The teacher orally identifies, describes, and explains the errors. Some suggested translations may be provided, but giving suggestions is optional.. 7.

(20) 5.. Translator Seminar: This seminar, held by the translator group in Cycle I, is conducted simultaneously with within-group discussion. Each group sends one member to this seminar to ask the translator group questions, to search for explanations, or to work together for a better translation. The guest teacher sits with the translator group to provide counseling.. 6.. Student Seminar: This seminar, held by the students in Cycle II, is conducted simultaneously with the Teacher Seminar. Each group sends one member to this seminar according to the roles they play, such as the vocabulary-level role. One of the translators takes part in and is responsible. 學. ‧ 國. 7.. 治 政 for answering questions and giving explanation 大to seminar participants. 立 Teacher Seminar: This seminar, led by the teachers in Cycle II, is conducted simultaneously with the Student Seminar. Each group has to send one. ‧. member to this seminar to discuss translation errors with the teachers.. y. sit. Agreeable and disagreeable translation: The students’ translation which. io. er. 8.. Nat. Teachers and students cooperate to produce a better translation.. al. students’ peers agree or disagree on. For disagreeable translation, peers. n. iv n C point out the weakness orherrors and provideUrevision suggestions to make engchi translation more agreeable. Translator groups can reexamine the translation from readers’ points of views and make a decision on the necessity of the revisions to be made. 9.. Acceptable and unacceptable translation: The students’ translation which teachers accept or do not accept. The acceptable level can be based on the teachers’ evaluation criteria. For unacceptable translation, teachers point out the weakness or errors and require the translator group to make translation more acceptable based on the teacher’s revision suggestion. 8.

(21) Significance of the Study The significance of the study is its contribution to the field of applied translation studies in a broader sense, as well as the existing translation pedagogies in particular. In the field of applied translation studies, translator training is one of the important domains (Holmes, 1988). It includes teaching methods, testing techniques, and curriculum design; however, it has received less attention than translation studies. The current study, focusing on an instructional design for cooperative, experiential, and negotiated translation learning, provides an alternative approach for effective translation training.. 治 政 As for translation pedagogy, the task itself and its practical 大 implications from the 立 study are helpful in several aspects. First, the CoTT and its five sessions provide ‧ 國. 學. translation teachers an alternative way to teach, especially for teachers trained in other. ‧. professions. This innovation and other advantages of this task can improve translation. sit. y. Nat. instruction beyond the conventional form. Second, students learn to work on teams,. io. er. which they will have to do in the real world. At the same time, their beliefs in their. al. translation competence and translating styles may be strengthened through text. n. iv n C analysis, translation peer review, and peer responses. U Finally, the practicality of this he ngchi proposed task is demonstrated through a cyclical research process, so it is expected that this study will persuade more translation practitioners to employ the CoTT and transform their translation classrooms into more interactive, collaborative, communicative learning environments. In addition to pedagogical implications, this design-based study offers three kinds of theories: domain theories, a design framework, and design methodologies. First, the domain theories were developed based on the description of learning situations involving students, teachers, learning environments, and interactions in translation classrooms. The nature learning of students at a technological university was closely 9.

(22) explored and examined. With these theories in mind, it would be easier for teachers to adopt and adapt the CoTT to their own classrooms. The second kind of theories refers to a design framework of the CoTT, which was developed during the iterative process and ongoing modification in order to solve problems in the design. The last theories are related to design methodologies, the methods used to implement the model. To promote the practicability of the CoTT in real classrooms, it is important to provide teachers with the methodologies, or implementation guidelines, to conduct the CoTT. With the domain theories, design framework, and design methodologies provided, translation teachers can have a better understanding of a cooperative translation. 治 政 context, and the methodologies for implementation and大 problem solving therein. 立 Organization of the Present Study ‧ 國. 學. Chapter 1 describes the background of the study up to the construction of the. ‧. CoTT for translation teachers, including the motivation from the researcher’s teaching. sit. y. Nat. experiences, the new trend of translation pedagogy, and the theoretical rationale. The. io. addressed as well.. er. purposes of the current study and its contribution to the translation education are. al. n. iv n C Chapter 2 reviews three theoretical and one research method. The h e nframeworks gchi U. theoretical frameworks include related research on translation teaching and a literature review of cooperative learning and peer response. Finally, the research method employed in this study, Design-based research, is introduced. Chapter 3 discusses two designs. The first one is the design of the Cooperative Translation Task (CoTT). The second is this study’s research design, which supports two cyclical research processes. The participants, procedures, and data collection for each cycle are introduced respectively. Chapter 4 provides answers for the first research question. The results of implementing the first prototype of the CoTT are analyzed in the Activity Theory. 10.

(23) Based on the analysis, modifications of the second prototype are provided. Chapter 5 provides answers for the second research question. The results of implementing the second prototype of the CoTT are analyzed in the Activity Theory. Based on the analysis, modifications of the latest version of the CoTT are provided. Chapter 6 provides answers for the third research question. The results of the two prototypes are analyzed and the domain theories and design frameworks are developed. By utilizing these two kinds of theories, the latest version of the CoTT is constructed, including both implementation guidelines and design methodologies. Chapter 7 summarizes the major findings of the results of Cycle I and II, and. 治 政 three kinds of theories. Pedagogical implications are also 大reviewed. This chapter 立 closes by pointing out its limitations and suggesting future research. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 11. i Un. v.

(24) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. The literature review of this chapter is based on four theoretical frameworks. The first one reviews related studies on translation instruction. The second one introduces cooperative learning, including its definition, theoretical background, features, and main activities. The third one addresses peer response, one kind of cooperative group work (Lui & Hansen, 2005).The last one deals with the introduction of the research method utilized in the study, design-based research.. 治 政 Research on Translation Teaching 大 立 In the area of translation teaching, Kiraly (1995) expressed his surprise that “as ‧ 國. 學. late as the mid-nineties the communicative revolution seemed to have passed. ‧. translation teaching by” (p.253). With this notice, the stress on language function,. sit. y. Nat. communicative competence, creativity, and active student participation has slowly. io. er. come to the world of translation didactics (Cronin, 2005). The translation theorists in. al. the 1990s on the development of the autonomy and self-confidence of the student. n. iv n C translator, such as Giles (1995), Kussmaul Kiraly (1995) and Robinson (1997), h e n g(1995), chi U are thus trying to keep up with the pedagogical spirit of the age with its aim to ‘deschool’ education and hand the learning initiative over to the learner, moving away from top-down, teacher-centered approaches. However, a number of scholars found that that many translation teachers still utilize traditional translation teaching, and the typical activities are teacher’s lecture, translation exercises, teacher’s correction, and appreciation of good translation works (Chang et al., 1993; Mu, 1992; Dai, 2003). The possible reason why teachers still use traditional teaching methods could be a lack of related research on translation pedagogy, as compared with the abundant research on English teaching methodology. 12.

(25) Moreover, there is a lack of a systematic and well-designed translation teaching approach for teachers to shift the class into a more communicative one. Despite a number of advantages of traditional translation teaching methods, such as delivering translation theories in lectures, some problems have been found in these methods as well. Kiraly (1995) claimed that traditional translation classes seem to lack both pedagogical guidelines and a motivating component. As Kiraly (1995) put it: “There has been little or no consideration of learning environment, student-teacher roles, scope and appropriateness of teaching techniques, coordination or goal-oriented curricula, or evaluation of curriculum and instructor” (p. 11). González Davies (2004). 治 政 also found that traditional translation classrooms are usually 大 teacher- and 立 text-centered and writing-based, without consideration of class dynamics and ‧ 國. 學. interaction. She reported that these traditional translation classrooms usually share the. ‧. characteristics of transmitted knowledge, teacher-centered instruction, and the. sit. y. Nat. ignorance of respecting learning styles, teaching styles, and translation styles. In other. io. er. words, in translation classrooms, students may have low learning motivation; a lack of. al. respect for peers’ translation styles, peer response and self-response; and no identity. n. iv n C of being professional translators. Many just followers of teachers’ suggestions. h e are ngchi U. With the hope of filling the pedagogical gap and improving traditional translation instruction, Kiraly (1995) proposed communicative translation teaching (CoTT) in an attempt to change a passive and singular-perspective student into an active and multi-perspective translator. To do so, he proposed the following: 1. Change classes from teacher-centered to student-centered. 2. Use teaching methods that foster responsibility, independence, and the ability to see alternatives. 3. Use role-plays and simulations. 4. Foster creativity and cooperation through small-group exercises. 13.

(26) 5. Give students the tools for using parallel texts and textual analysis to improve translation. 6. Teach translation as a realistic communicative activity. 7. Adopt new approaches to translation evaluation, such as commented translations. Sharing a perspective toward translation teaching similar to that of Kiraly (1995), González Davies (2004) observed that translation training is relatively close to language learning. She attempted to draw teaching approaches and ideas from the language-learning field, and then select, integrate and adapt the special characteristics. 治 政 of translation studies. She advocates incorporating four大 approaches, Humanistic 立 Teaching Principles, The Communicative Approach, Cooperative Learning, and ‧ 國. 學. Social Constructivism, so that the procedures, including activities, tasks and projects,. ‧. help students to:. sit. y. Nat. 1. Reflect on their beliefs about translation and self-concept as translators.. io. er. 2. Overcome personal and professional constraints.. al. n. 3. Understand the importance of updating not only their computer & marketing. ni Ch skills, but translation knowledge. U engchi. v. 4. Motivate them. 5. Become autonomous problem solvers. 6. Develop problem-spotting and solving abilities. 7. Identify and respect text types and conventions of presentation and style. 8. Understand the full importance of translation assignment and reader. Similarly, for university students who are studying translation, Malmkjær (2004) suggested that undergraduate translation students’ activities should motivate them, train them as more autonomous problem solvers, develop their skills in problem-spotting and solving, and raise awareness of the importance of conventions 14.

(27) of presentation and style, and the translation assignments. Kiraly (1995) emphasized that a teacher’s responsibility is to help students to see alternatives, the range of possible translations, and these will be paths for learners to become more independent. González Davies (2004) further proposed experiential learning and task-based learning. Classrooms are often considered artificial and cannot help students to overcome possible problems in their future profession. However, it is impossible to go back to the apprenticeship system or to unplanned “in-house on-the-job training” (Gile, 1995, p. 8). Thus, she suggested transforming the classroom into a discussion. 治 政 forum with hands-on workshops, and contacting the outside 大 world by means of 立 projects involving professionals. It is important to include as many real-life situations ‧ 國. 學. as possible so that the students have the chance to live in the professional world.. ‧. Moreover, this kind of environment should enhance students’ potential and respect. sit. y. Nat. different learning styles. It is apparent to see that the notion of cooperation underlying. io. er. translation classrooms, such as a discussion forum, is little different from the one in. al. language classrooms, with the common goal being to develop the ability to. n. iv n C communicate in the real world. Thehgoal of the cooperation e n g c h i U is to bridge the gap between the students and the professional world. Similar to the experiential learning of González Davies (2004), Nord (2005) believes that team work and management skills are qualifications of a professional translator, whether s/he works for a translation agency or free-lance, while in the traditional translation classroom, these qualifications cannot be acquired. Thus, she advocates role-playing and acquiring responsibility in training. Each student has the chance to play various roles: client, reviser, terminologist, documentation assistant, free-lancer, in-house translator, and so on. The teacher’s role is that of monitor and fire-brigade, but students learn to manage their translation projects autonomously. 15.

(28) As for task-based learning, González Davies (2004) advocated function-, process- and product-based teaching. As she (2004) put it: “In task learning, a chain of activities are related to each other and are sequenced in such a way that they lead to a final product” (p. 23). Functional-based teaching attempts to make students aware of why, where and when the translation assignment is carried out. This is the information that should be known by students before doing translation (Nord, 1997). Process-based teaching asks for awareness of the translation strategies and solutions used by students themselves in their assignments. This approach increases their self-confidence and contributes to greater coherence, quality, and speed in their. 治 政 translation. Finally, product-based teaching looks at what 大the students achieve. In 立 other words, it focuses on the final translation produced by the student. ‧ 國. 學. Though a notion similar to communicative translation teaching (CTT) has been. ‧. promoted by a number of scholars (Colina, 2003; Kiraly, 1995; González Davies. sit. y. Nat. (2004), few empirical studies have been published to date. Romney’s (1997) study is. io. er. the only published journal article that specifically examines the possibilities of using. al. collaborative learning in translation classrooms with an attempt to provide an. n. iv n C alternative to traditional classroom h structure and increase e n g c h i U student participation. Romney (1997) claimed that in traditional classrooms, the teacher is usually the judge of the quality of the translation, so only the bravest students are dared to offer alternative translations. Accordingly, students only learn through their own individual efforts and gain limited and erroneous results. Romney’s (1997) results showed that collaborative learning in a translation course can facilitate the understanding of the source text and help students reach greater degrees of grammatical correctness, accuracy, and faithfulness through discussion and negotiation. Moreover, social support is an important element in sharing the difficulties. It has been found that students gain in self-confidence and become more tolerant of different opinions, and 16.

(29) that they appreciate the non-threatening atmosphere of group work. Another survey study, conducted by Ulrych (2005), examined the translation teaching methodology adopted by the various institutions and the rationale underlying the features of course content. It is found that in response to the question on classroom management and dynamics, more and more instructors recently have been using collaborative discussion/corrections in class in three kinds of interactions: teacher/student, students in group, students in pairs. The underlying rationale is to train students to cooperate with others such as fellow translators or clients in their future professions.. 治 政 Studies on Translation Teaching 大In Taiwan 立 Information on translation instruction in Taiwan is quite limited, especially that on ‧ 國. 學. alternative translation teaching methods. However, some of the studies seem to follow. ‧. the new trend of communicative translation teaching. For example, Lai (2002). sit. y. Nat. conducted translation projects with the professional world in different fields,. io. er. including a book publisher, a television station that plays movies, and a public. al. television station. The main purposes of the intern projects were to offer students. n. iv n C chances for contact with real practitioners understand the needs and challenges of h e nand gchi U a career in translation in the hopes of helping students prepare for their future careers and further study. Lai’s (2002) attempt has opened the possibilities of bridging the gap between the students and the professional world, as González Davies (2004) proposed. Following the trend of humanistic teaching and constructivism in recent years, Liao has been promoting communicative translation teaching and attempted to provide a more creative and student-centered approach of instruction. Liao and Chiang (2005) explored the possibilities of using portfolios as an alternative method to teach translation. The process of portfolio instruction, including the teaching 17.

(30) materials and assessment criteria, and questionnaire results were provided in that study. Based on class observation, it was found that students generally went through four stages. Students started with high interest and engagement, followed by learning anxiety about filling in forms and producing peer response. In the third stage, students began to adjust to this approach and demonstrated learning autonomy. Finally, students accepted this approach and learned how to be responsible translators, aware of their own learning process and progress. The survey results showed that 92% of the students believed that portfolios facilitated their learning, and all of the students agreed that it improved their English comprehension. However, he also found that. 治 政 college students’ reflective ability was not well developed, 大 which may result from 立 long-term passive learning and a transmissionist teaching approach. ‧ 國. 學. In 2009, Liao (2009) proposed a theoretical basis of constructivism for teaching. ‧. translation in Taiwan’s colleges, with the use of communicative translation teaching.. sit. y. Nat. Meaningful tasks, cooperative learning, peer tutoring, and on-line learning platforms. io. er. have been included as teaching techniques. That study found that generally students. al. had a very positive view of the course design. Students were aware of the major. n. iv n C difference in the teacher’s role; the h teachers became facilitators of the learning engchi U. process. The on-line communication mode increased the interactions among the learning Community, the teacher, and the other students, and even the materials. Moreover, the on-line questioning lowered students’ anxiety about asking questions before class and created a more autonomic and collaborative learning climate. Sharing a similar perspective toward the innovation of alternative translation approaches and techniques, I also conducted a series of studies on incorporating collaborative learning and a communicative approach in translation classrooms. In order to construct a more student-centered classroom, in 2007, I conducted two needs analysis studies for Chinese to English Translation learning and English to Chinese 18.

(31) learning in a technological university. In 2008, I compared the results of these two studies and wished to draw some conclusions about students’ expectations toward the study of translation. To closely relate that to the present study, only the most related results will be reviewed here. First, concerning grouping, both groups preferred group work. The subjects’ agreement (E-C vs C-E) on group work was 61% and 75%, on pair work was 39% and 27%, on individual work was 27% and 19%, and on the whole class work was 4% and 2 %. In regard to the learning activities, two groups of subjects preferred ‘training of language skills’, ‘group in-class translation’, and ‘discussion on translation’. It. 治 政 seems that students expected to sharpen their language大 skills as their first priority, and 立 they needed partners to work on translation problems. Finally, discussion of ‧ 國. 學. translations helps them to identify and analyze errors. However, we may not jump to. sit. y. Nat. ranked sixth in the E-C group, and fifth in the C-E group.. ‧. the conclusion that students prefer more cooperation in response, as peer-editing was. io. er. Based on the results of the needs analysis and the exploration of the importance. al. of cooperative learning, I started to design peer activities. In 2007, I explored. n. iv n C students’ perspectives toward peer-response translation through blogs. h e n gincEnglish hi U Each group received responses and corrections from the other nine groups each week, and at the end of the semester, each group needed to turn in their final-version translation, revised according to peer response. In 2009, I further examined students’ learning logs and found that students became aware of the importance of collaborative learning through log writing. With the emerging evidence from these two studies, I began designing more practical, authentic, and complicated cooperative translation tasks, including a study on translator seminars between a translator and a student audience, and a task-based translation project with a non-profit organization (NPO) in 2009. It was found that the translator seminars raised students’ motivation to dig out 19.

(32) the best translation through negotiation with peers and with teachers. They started to look at the translation from other perspectives instead of their own or the teachers’. They learned to insist on their own perspective, to argue for their stand, and also to listen to peers’ suggestions through debate and negotiation. The task-based project with the NPO brought them into the real world of translation work. Reviewing the above theories suggested by leading scholars in translation teaching and learning, the present research notices that they contribute significantly to the development of alternative translation pedagogy, despite the fact that at present, research focusing on the areas of translation teaching is still very scarce. It is still. 治 政 worth emphasizing that the newly promoted teaching methodologies analyzed above 大 立 have shifted from transmitted knowledge to transformational knowledge, ‧ 國. 學. teacher-centered to student-centered, individual work to collaborative work,. ‧. molecular learning to social-constructive learning. These teaching methods can train. sit. y. Nat. students as more autonomous problem solvers and efficient communicators between. io. er. the source and target text. These methods also need to meet the needs of modern. al. translation practice. College learners’ translation studies should not only focus on the. n. iv n C use of language but also the development qualifications of a professional h e nofgthe chi U. translator, especially for the students at a technological university. Cooperative team work and management skills for their translation projects should be included. With the benefits from both product-based and process-based teaching advocated by scholars, it seems that none of each should be neglected in alternative translation instruction. With my growing research interests in incorporating collaborative learning in translation instruction, the present study will follow that new trend and continue my research orientation to explore the possibility of realizing a communicative approach and cooperative learning in translation classrooms. In the next section, the characteristics of cooperative learning (CL) will be discussed in order to explore the 20.

(33) possibility of incorporating it into translation teaching and learning. Cooperative Learning Cooperative learning (CL) has been defined by many scholars (Olsen & Kagan, 1992; Johnson & Johnson, 1994; Slavin, 1994). Johnson, Johnson, and Holubec, leaders in cooperative learning, offer the definition: “Cooperative learning is the instructional use of small groups so that students work together to maximize their own and each other’s learning (1993, p. 9). Generally speaking, Cooperative Learning is a group-work approach, allowing students to actively participant in their own learning and in the construction of knowledge (Slavin, 1997). One more point should be. 治 政 covered in the definition of cooperative learning. For some 大 educators, cooperative 立 learning is synonymous with collaborative learning (e.g., Romney, 1997). Romney ‧ 國. 學. sees cooperative learning being used in primary and secondary education, and. ‧. collaborative learning with older students. On the other hand, Chung (1991) views. sit. y. Nat. collaborative learning as an umbrella term that includes cooperative learning. Sharan. io. er. and Sharan (1992) suggested that there exists a wide range of options in terms of. al. teacher influence of student-student interaction, and that the cooperative learning. n. iv n C technique called Group Investigation allows students U a great deal of control over such he ngchi matters as selection of topic, group mates, and collaboration procedures. The present study agrees with Sharan and Sharan’s (1992) broad interpretation; the term cooperative learning should be understood as including collaborative learning. Theoretical Perspective of Cooperative Learning The theories underlying cooperative learning can be discussed from four theoretical perspectives: the motivational perspective, the cognitive developmental perspective, the cognitive elaboration perspective, and social interdependence theory. The motivational perspective suggests that intrinsic motivation, high expectations for success, high incentive to achieve based on mutual benefit, high epistemic curiosity, 21.

(34) high continuing interest in achievement, high commitment to achieve, and high persistence promote the motivational system (Johnson & Johnson, 1999). Dörnyei (1994) suggested that the motivational complex underlying L2 learning is a multidimensional construct comprising three independent levels: (1) language level; (2) learner level; and (3) the learning situation level, and that the learning situation level has the greatest impact on learner motivation. Dörnyei (1997) further identifies motivational components at the learning situation level, including classroom goal structure, group cohesiveness, goal-orientedness, and a reward system. In other words, the operation of these motivational components can strengthen students’ motivational. 治 政 system and increase their intrinsic motivation and high大 incentive to achieve mutual 立 goals in a cooperative context. ‧ 國. 學. The cognitive developmental theory is mainly based on the theories of Piaget,. ‧. Vygotsky, cognitive science, and academic controversy (Johnson & Johnson, 1999).. sit. y. Nat. In the Piagetian tradition, a student’s intellectual development is accelerated by asking. io. er. him or her to reach consensus with students who hold opposing opinions. In the. al. Vygotsky tradition, it is claimed that knowledge is socially constructed from. n. iv n C cooperative efforts. From the perspective science, cooperative learning h e nofgcognitive chi U involves modeling, coaching, and scaffolding. The learner must cognitively rehearse and restructure information to be retained in memory and incorporated into existing cognitive structures (Webb, 1985). It was suggested by Johnson and Johnson (1985) that oral rehearsal, or mentally rehearsing and presenting information to others, enhances one’s own retention of information (Putnam, 1997). The socially and cognitively constructed knowledge can be built through oral discussion with peers and presentations of learning products. In cognitive elaboration theory, it is believed that through mutual concern and discussion of various perspectives, students’ personal and intellectual growth will be 22.

(35) enhanced (Flurkey, 1992). For example, students learn to construct knowledge through the peer tutoring process and enhance comprehension of the new materials. This mutual concern falls under social interdependence, which exists when individuals share common goals and each individual’s outcomes are influenced by the actions of others (Johnson & Johnson, 1998). According to Johnson and Johnson (1998), positive interdependence (i.e., cooperation) results in promotive interaction, as individuals facilitate each others’ efforts to learn. Negative interdependence (i.e., competition) brings about oppositional interaction, as individuals hinder each others’ efforts to achieve. The absence of interdependence (individual efforts) brings no. 治 政 interaction, as individuals work independently (Johnson, 大Johnson, & Holubec, 2002). 立 In a word, to create a cooperative learning context, teachers should encourage positive ‧ 國. 學. interdependence among students, and avoid negative interdependence.. ‧. Features of Cooperative Learning. sit. y. Nat. Generally, there are five main features of Cooperative Learning, which make it. io. er. more effective in learning: (1) positive interdependence; (2) face-to-face interaction;. al. (3) interpersonal and small group skills; (4) individual accountability; and (5) small. n. iv n C and heterogeneous groups. Johnson,hJohnson and Holubec e n g c h i U (2002) asserted that. positive interdependence is the first and the most important element of cooperative learning. Johnson and Johnson (1994) developed many applications of the concept of interdependence to education and attempted to find ways to increase the feeling of positive interdependence within learning groups. They believed that when students believe that they sink or swim together, learning activities become meaningful (Johnson & Johnson, 1994) and students become an alternative source of positive reinforcement for one another. According to Johnson and Johnson (1994), positive interdependence can be achieved through mutual goals (goal interdependence); sharing materials, resources, or information with group members (resource 23.

(36) interdependence); division of labor (task interdependence); assigning complementary and interconnected roles (role interdependence); and giving a joint reward (reward interdependence). These interdependences can make students aware of what they need from each other, and collaboration can take place. Face-to-face interaction engages students in higher-level thinking skills, such as analyzing, explaining, synthesizing, and elaborating (Hilke, 1990). Several studies have proven that interaction facilitates comprehension better than conditions without the interaction component (Gass & Varonis, 1994; Loschky, 1994; Polio & Gass, 1998). With face-to-face interaction, knowledge can be comprehended better through. 治 政 students’ stimulating talk and the integration of various大 perspectives. 立 Though positive interaction is the key to successful learning, it is important to ‧ 國. 學. teach social skills in order to promote effective communication, respect, and trust. ‧. within groups. It is generally agreed by scholars that the more socially skillful. sit. y. Nat. students are, the higher the achievement that can be expected within cooperative. io. er. learning groups (Mesch et al, 1986). When students have these skills, they naturally. al. increase interpersonal relationships, promote achievement, and have psychological. n. iv n C health. Moreover, low achievers will and supported by group mates, h feel e naccepted gchi U which leads to positive attitudes towards learning (Adam & Hamm, 1990). Hilke. (1990) suggested that social skills can be learnt from well-functioning groups, which will help students to communicate effectively and to develop respect and trust within the group. Johnson and Johnson (1994) suggested that the social skills can be characterized by such qualities as communicating accurately, accepting and supporting each other, and resolving conflict constructively. With explicit instruction in social skills, high quality cooperation can be reinforced. Individual accountability is the key to ensuring that all group members are strengthened by cooperative learning (Slavin, 1997). When members have a sense of 24.

(37) personal responsibility to their mates, they will contribute their shares to the groups’ success, knowing at the same time that they can seek support and assistance from them (Hilke, 1990). However, making students understand their personal responsibility to help others for the group’s success is a difficult task for teachers. Johnson and Johnson (1994) provided some suggestions to structure individual accountability. First, teachers should keep the size of the group small. The smaller the size of the group is, the greater individual accountability will be. Second, students can be randomly called on to present a group’s work to the teacher or to the entire class. Third, teachers should observe the interactions within each group and take note of. 治 政 each member’s contributions to the group work. Fourth, 大it is important to assign one 立 student in each group the role of leader, and one of his/her responsibilities is to make ‧ 國. 學. sure that each member participates. Finally, teachers should give students a chance to. ‧. teach what they have learned to others, which is called simultaneous explaining.. sit. y. Nat. Several principles can be drawn from Johnson and Johnson’s suggestions. First,. io. er. individual accountability requires monitoring from the instructor and a group member,. al. such as a group leader. It may imply that without monitoring, it is likely that students. n. iv n C will try to avoid individual responsibility. the awareness of individual efforts h e nSecond, gchi U depends on group cohesiveness. A small group size means physical closeness and more independent shared responsibility. As Dörnyei’s (1997) suggested on group cohesiveness, proximity and physical closeness is one way to enhance group cohesiveness. Third, the demands for sharing and presenting the group work motivate students to contribute their individual efforts. It is found that one potential barrier to effective group learning is a lack of sufficient heterogeneity (Johnson & Johnson, 1994). For example, with similar ability, some groups perform better than low-achiever groups, as they are all high achievers, which demotivates low-achievers. Hilke (1990) suggested that students be placed in 25.

數據

相關文件

To share strategies and experiences on new literacy practices and the use of information technology in the English classroom for supporting English learning and teaching

develop a better understanding of the design and the features of the English Language curriculum with an emphasis on the senior secondary level;.. gain an insight into the

To provide suggestions on the learning and teaching activities, strategies and resources for incorporating the major updates in the school English language

Literature Strategically into English Learning Inside and Outside the

After students have had ample practice with developing characters, describing a setting and writing realistic dialogue, they will need to go back to the Short Story Writing Task

- Informants: Principal, Vice-principals, curriculum leaders, English teachers, content subject teachers, students, parents.. - 12 cases could be categorised into 3 types, based

• School-based curriculum is enriched to allow for value addedness in the reading and writing performance of the students. • Students have a positive attitude and are interested and

Through an open and flexible curriculum framework, which consists of the Learning Targets, Learning Objectives, examples of learning activities, schemes of work, suggestions for