ICT’s Nurturing and Fruiting in a Global Knowledge-based Economy: A Comparative Study of Taiwan and Korea

1. Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) play a pivotal role in the world economy. The ICT sector is increasing its trend share of economic activity, and ICTs are an important input for economic performance. Over the last two decades, the ICT-producing sector has become increasingly globalised. The sector’s underlying structure and dynamics ensure its position at the forefront of globalisation, although the role of its different segments varies.

ICT development varies immensely between Asian countries. In countries like South Korea and Taiwan a sharp increase of Internet use took place during the late 90s and at the beginning of the millennium. In other countries, however, like India and China the Internet adoption still remains low. Korea and Taiwan are identifiable as knowledge- and/or techno-based economic growth areas in East Asian, where ICTs play a role in supporting their level of competitiveness in the global economy. Understanding the role played by ICTs in the transformation of industrial societies to information societies, and subsequently in the preparation for knowledge-based societies is a key issue.

When we look at those catch-up strategies from countries like Korea or Taiwan, we see they broke with traditional patterns of technological development and were characterized by radical innovations in those globally fast growing sectors they specialized, such as ICTs and electronics. Some studies point at their stock of well-trained human resources as the reason behind their success (Kim, 1990; Young, 1995). However, it derives from a narrowly neoclassical view of separating inputs as between labour, capital and technology – but if we note that technology policy may be reflected in the rapid and consequent growth of quality-enhanced factor inputs rather than just in exogenous ‘R&D’, then its primary role in the development process can easily be restored. It is difficult to reject the view that the rapid growth of highly-skilled labour and advanced capital in countries like Taiwan came about because of technological change and restructuring in the light of policy, as well as facilitating it. Therefore, the dynamism of technology development in these countries cannot be simply explained by their stock of human resources. The so-called "Tigers" since the 1970s concentrated their investment, their R&D, their infrastructural development, their training and their technology input on the electronic and telecommunication industries (Hobday, 1995).

communication technologies (ICTs) in generating both economic and social development in these two geographic areas which are competing globally. This study especially will focus on understanding the role played by ICTs in the transformation of industrial societies to information societies, and subsequently, in the preparation for knowledge-based societies. The study will also aim to identify what the resulting characteristics of these transformations might be, and how they may be affected by the tensions between economic growth, social equity, quality of life and individual satisfaction.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The next section, we have a quick sketch the methodology adopted by this study. The section 3 and 4 introduces the nurturing and fruiting for ICT sector in Korea and Taiwan underlying the frame of analysis. The paper finishes with concluding remarks in Section 5.

2. Methodology

The methodology aims at determining the means to describe the relevant socio-economic characteristics of these two regions, and the relationships which can be identified between them. It intends to point out where they share policy approaches, as well as where they differ. The methodology we would be thinking of developing is therefore system-based. Therefore Korea and Taiwan growth has to be studied as a system – of innovation, but more widely of production, including systems of organization, finance, markets, government/private interaction, etc. To meet the general aim of the study, an in-depth analysis of the economic, technological, institutional of Taiwan and Korea is suggested.

Besides, the methodology based on the “comparative study”, and thus be to compare these heterogeneities and establish whether there are any regularities or instead that national (and maybe regional) systems of innovation prevail. The principal objective here will be to establish the ‘correlates’ of economic growth – to what extent differences in growth patterns as between these two countries match differences in the clutch of possible growth drivers suggested by dynamic competition.

The access to ICTs has been growing at high speed in these two countries. Especially during the late 90s ICT evolved at great speed and was corresponded by economic growth after the Asian crisis. The rapid growth of the ICTs has been partly driven by demand side factors, such as increasing internet use and mobile phones on the one hand

and by supply side factors such as regulatory reforms, cost and prices, technological innovation an the other. Therefore, this study will be explored in terms of four dimensions, they are respectively characterization of the ICT sector for individual case studies, supply side factors, demand side factors and ICT Policies and related initiatives (see figure 1). All these dimensions are interplay and interdependency within the context and process of dynamic environment.

3. Korea Case

3.1 Characterization of Korean ICT sector

The Asian financial crisis has undoubtedly resulted in tremendous economic and social consequences in South Korea. This disruption mainly stemmed from fundamental structural weaknesses in its institutions that support national innovation. The crisis has resulted in numerous negative consequences in the short-term, but also provided a rare opportunity for South Korea to fix its system in the long-term.

In order to understand the impressive growth of ICT in Korea – particularly in the 1990s – many publications point to the government policy as a major factor. In fact, to explain why Korea's ICT growth was so rapid within such a short period of time, it is best to look at the national strategies rather than the market mechanisms. Above all, the privatization of the telecommunications service market and the introduction of competition in 1990, 1994 and 1995 resulted in the raise of efficiency, the acceleration of private investment and in structural change in the IT industry as a whole (see UNESCAP 2004: 64). Now, the IT/ICT industry has become a growth engine for the Korean economy since that crisis.

deems "strategic". The government makes small, strategic investments that evolve into much larger investments from the private sector. Examples include textile and shoe manufacturing in the 1960s, the shipbuilding industry in the 1970s, the automobile industry since the 1980s and electronics in the 1990s. More recently, the government has successfully promoted different schemes to allow Korea to take a leadership role in emerging technologies (e.g. CDMA technologies, home networks, digital content, system-on-chip, telematics, embedded software, digital television).

During the development and implementation of a series of key national ICT related initiatives or programmes, strategic cooperation between the government and the private business sector was made possible by the emergence of competitive private enterprises – like in the telecommunication market – and the expansion of the domestic ICT market. The government played a primary role in initiating national projects at the beginning, but once the market had developed, it devolved that role to the market and switched its

attention to the next generation of projects (Hwang 2005: 129).

3.2 Supply Side Factors for ICT growth and fruitfulness

3.2.1 HR Development

With the emergence of the new IT businesses and the steering of traditional industries into the IT sector, the demand for skilled labour is increasing rapidly. Therefore, the government has invested 33.5 billion won in support of education in the ICT area, establishment of a technical high school specializing in software development, and basic research in related subjects (UNESCAP 2004: 72). Furthermore, the government has provided support for the development of a University Information and Communication Research Center, an Information and Communication University Overseas Scholarship Program for ASIC design and Java training.

The government has also sponsored information and communication training courses for the unemployed with high academic backgrounds from traditional industries. This will assist such qualified unemployed to find jobs in the IT sector or to start new IT businesses. In addition, government support has been provided to IT professional education organizations, cyber universities involved in the field of information and communication, the invitation and training of foreign IT specialists and experts. To further develop human resources in the IT field, the government has provided computer literacy training and education aimed at elementary and middle schools, housewives, the military, and the disabled.

The Korean government will invest approximately 430 billion won in expanding the involvement of regular educational organizations in information and communication education, as well as cooperation with overseas schools and universities (UNESCAP 2004: 73). The government also plans to sponsor the retraining of industrial workers, bridge the digital gap among the populace, and develop a highly skilled workforce for the IT field. The government will expand its investments in discovering the gifted IT

talents in their early stages and nurturing them to contribute to the world economy.

3.2.2 Initiates for R&D development

The government has all along supported the development of the ICT sector and has created favourable conditions for Korean companies to participate in the sector. Against the background that research and development (R&D) can be considered as one of the driving factors of competitiveness and innovativeness, R&D investments of the Korean government in ICT (and some other technologies) has a strategic relevance. For the period 1994-2001, the average growth rate of R&D expenditure in ICT was about 33%. In 2001, R&D investment in ICT accounted for more than half of the total R&D spending in Korea. Although major parts of R&D in ICT have been financed and performed by private businesses, the Korean government has been actively involved in major R&D projects such as TDX technologies and CDMA.1 In 2001, approximately 12.3% of the total R&D expenditures in ICT were financed by the Korean government (KISDI 2005: 65).

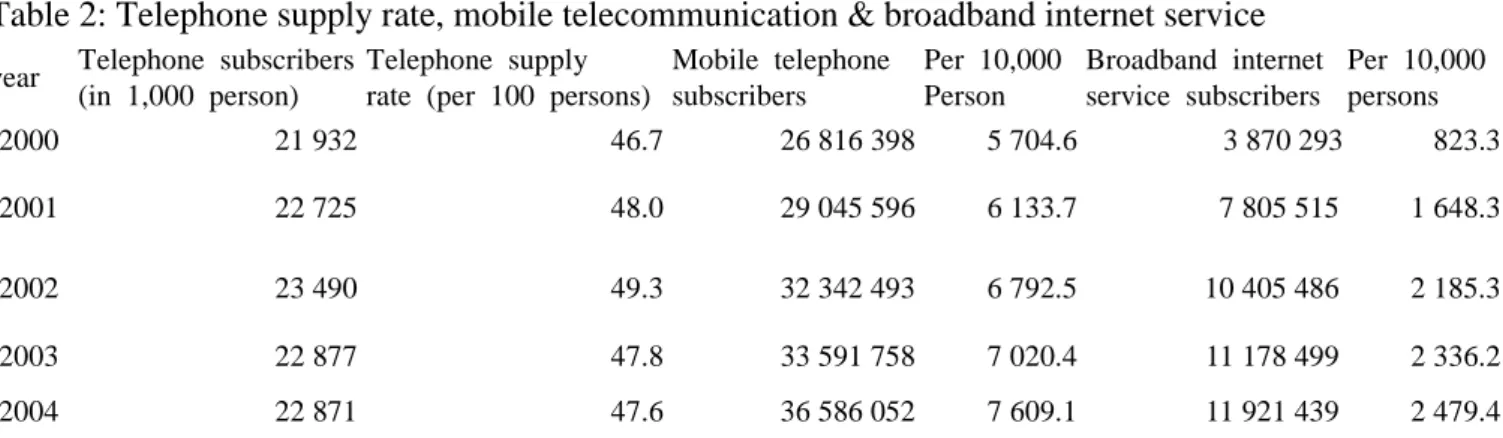

Table1: R&D expenditures on Information & Telecommunication

In 100 million won Year R&D Expenditures R&D expenditures on information & telecommunication As % of GDP Public Private 2001 161 105 94 205 1.51 15 839 78 336 2002 173 251 89 556 1.31 11 269 78 287 2003 190 687 92 824 1.28 9 783 83 041 2004 221 853 104 765 1.35 8 881 95 884 Source: Ministry of Science & Technology, and Institute of Information Technology Assessment

1 Lee/Lim (2001: 479) point out, that the two most important roles of the government in Korea are the guaranteed market protection and export subsidies as well as joint R&D with the private sector. This applies especially for D-RAM and CDMA mobile phones, whereas they provided market protection only for automobiles, and the PC industry, and offered incentives for the use of domestic products in the case of the machine tools industry.

As a source of public R&D investments in ICT investments, the so-called

Informatization Promotion Fund (IPF) plays an important role. The IPF was established

in 1997 and ensures stable funding for long-term R&D projects and enabling policy makers to flexibly respond to rapid changes in ICT. The Korean government recognized early on that these funds could be strategically reinvested in the telecommunications and ICT sector as a way to help Korea become a world leader in ICTs. The fund, in total, holds around US$ 5 billion and disperses around US$ 500 million each year on projects to help encourage access to information (see National Computerization Agency, ITU 2005: 8). These investments have produced phenomenal results in Korea, including establishing its position as the world's broadband leader. The Korean example shows how careful use of spectrum fees can help boost overall connectivity in the society, to

the benefit of the industry rather than as a tax upon it.

The Korean government has provided financial incentives to the private sector including preferential loans, tax incentives, and reduced tariffs on imports of R&D equipment, deduction of R&D expenditures and human resource development costs from taxable income, and support for small technology-based companies. It has no doubt, that the

government incentives eased the way for companies to invest in riskier R&D projects.

While the main target group of the above mentioned public R&D programmes are SMEs, supplementing policies to promote entrepreneurial activities in ICT (IT Venture) were developed. The government is an important player in fundraising. Since 2001, when private investors became pessimistic2, venture capital fundraising relied heavily upon the government. In the short run, it helps stabilize the fundraising for the venture capital industry which showed severe fluctuation in accordance with the business cycle. However, in the long run, the government may displace private efforts for fundraising. The financial system as a supporter of creativity (e.g. new business idea), Korean government establish the KOSDAQ stock market (comparable with NASDAQ in the United States). Only two years after its establishment, KOSDAQ has emerged as an important financing institution for hundreds of small- and medium sized venture companies and start-ups.

After the financial debacle in 1997, the Korean government initiated tax reduction for high-tech businesses, businesses in foreign investment zones and service businesses in assistance of advanced industries (national tax for 10 years, local tax for 15 years).

2 Although the number of certified ventures has decreased drastically since 2001, IT based ventures still take a large share (above 40%). During the IT boom in 1999-2000, VC investments in IT-based firms reached up to 70% out of the total VC investments (Hong 2005).

Rent reduction policy is also underway in industrial complexes for foreign companies, 25 national industrial complexes, and foreign investment zones (100% of reduction for high-tech businesses and 75% of reduction for general manufacturing industries). The total foreign direct investment (FDI) in Korea reached approximately USD 12.78 billion in 2004. The FDI in the IT sector amounted to USD 32 billion in 2004 or 25% of the total foreign investments. In recent 5 years, Korea has reached a very outstanding performance in ICT industry. ICT industry as a growth stimulus to the Korean economy: the IT industry’s relative importance to GDP has increased from 8.6% in 1997 to 14.9% in 2002, and the IT sector has also contributed 40% of the total increases in GDP in the past 5 years. The share of IT products as a share of overall exports has increased from 23% in 1997 to 28.6% in 2002. Among the leading products are the world’s best semiconductors, mobile communication, and TFT-LCD (MIC website, Korea).

3.3 Demand Side Factors for ICT

Table 2: Telephone supply rate, mobile telecommunication & broadband internet service year Telephone subscribers

(in 1,000 person)

Telephone supply rate (per 100 persons)

Mobile telephone subscribers Per 10,000 Person Broadband internet service subscribers Per 10,000 persons 2000 21 932 46.7 26 816 398 5 704.6 3 870 293 823.3 2001 22 725 48.0 29 045 596 6 133.7 7 805 515 1 648.3 2002 23 490 49.3 32 342 493 6 792.5 10 405 486 2 185.3 2003 22 877 47.8 33 591 758 7 020.4 11 178 499 2 336.2 2004 22 871 47.6 36 586 052 7 609.1 11 921 439 2 479.4

Source: Ministry of Information & Communication (www.mic.go.kr )

3.4 ICT related policies

3.4.1 Organizational and legal arrangement for an information society

Korea's policies on ICT or informatization are shaped and promoted by several responsible bodies, including the Ministry of Information and Communication (MIC), the National Computerization Agency (NAC), as well as central and local government. With a view to effectively pursuing informatization, the Korean government established the MIC in December 1994 as a government body responsible for implementing informatization policies, IT industry policies, and telecommunication regulation policies. This ministry was to integrate policy functions on telecommunications, broadcasting, and IT industry that had been dispersed to several ministries into MIC and get synergy from coordinating both demand and supply. In August 1995, the “Basic Act on

informatization, establishing the statutory basis for the MIC to effectively carry out informatization projects through coordinated efforts among the related agencies.

Based on the above legislation, the MIC established the Informatization Promotion Committee (IPC) as an organization facilitating informatization. As the highest deliberating body for various informatization policies and measures, the IPC is chaired by the Prime Minister, participating in the committee for discussion and review of major policies and plans. Moreover, to manage systematic and unified promotion of IT policies, the IPC deals with many important issues regarding the implementation of the Master Plans and key initiatives, Baseline Framework for e-commerce promotion, long-term plan for the e-government project, and Management of Digital Contents. Besides, the Informatization Strategic Meeting (ISM), chaired by the President, focuses on coordinating and checking major flagship projects that were included in the master plans.

Regarding the IPRs and Patent Law, the main administrative body in Korea, which deals with patent law and intellectual property rights, is the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO), which was established in 1977 as an external administration of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. In 1995 Korea joined various treaties, administered by the World Trade Organization (WTO), including the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). In 1994 KIPO has enacted the Invention Promotion Act, in the year 2000 it has organized the Patent Technology Commercialization Council and in 2003 it has built the Intellectual Property Service Center.

3.4.2 Promotion policy and initiates for ICT

The explosive growth of ICT in the late 1990s can be regarded as the cumulative result of a series of national projects which already begun 20 years ago. The government consolidated wired telephone networks, data networks and major databases with the goal of quickly building an information society via ICT utilisation and ICT industry development (Hwang 2005: 129).

In order to understand the impressive growth of ICT in Korea – particularly in the 1990s – many publications point to the government policy as a major factor (see Hwang 2005, ITU 2005, UNESCAP 2004). In fact, to explain why Korea's ICT growth was so rapid within such a short period of time, it is best to look at the national strategies rather than the market mechanisms. Above all, the privatization of the telecommunications service market and the introduction of competition in 1990, 1994 and 1995 resulted in

the raise of efficiency, the acceleration of private investment and in structural change in the IT industry as a whole (see UNESCAP 2004: 64).

The Korean government has been very successful at fostering certain industries that it deems "strategic". The government makes small, strategic investments that evolve into much larger investments from the private sector. More recently, the government has successfully promoted different schemes to allow Korea to take a leadership role in emerging technologies (e.g. CDMA technologies, home networks, digital content, system-on-chip, telematics, embedded software, digital television).

During the development and implementation of a series of key national ICT related initiatives or programmes (see below), strategic cooperation between the government and the private business sector was made possible by the emergence of competitive private enterprises – like in the telecommunication market – and the expansion of the domestic ICT market. The government played a primary role in initiating national projects at the beginning, but once the market had developed, it devolved that role to the

market and switched its attention to the next generation of projects (Hwang 2005: 129).

In addition to the initial funding of the government, the private sector has massively invested in the construction of the national information infrastructure centered on large cities and businesses in order to offer universal service to the public and to handle the growing traffic volume. Particularly in the 1990s, the government devoted much of its energy to the ICT industry or to informatization. Both the government and the private sector have concentrated their investments on building up a more efficient and faster information infrastructure.

Since 1999, the Korea government establishes Cyber Korea 21 as the blueprint for the new information society of the 21st century in order to overcome the Asian Economic crises and to transform the Korean economy into a knowledge-based one. Followed, they established “e-Korea Vision 2006” in April, 2002 with a plan to constantly upgrade the information infrastructure and to strengthen the informatization capacity of government, institutions, and individuals, all in order to present a vision for Korea to emerge as the global leader in this area. Its objectives are to (1) maximize the ability of citizens to utilize ICT to actively participate in the information society, (2) strengthen global competitiveness of the economy by promoting informatization in all industries, (3) realize a smart government structure with high transparency and productivity through informatization efforts, (4) facilitate continued economic growth by promoting the IT

industry and advancing the information structure and (5) become a leader in the global information society by playing a major role in the international cooperation.

In response to the launch of the "participatory government" in February 2003, the cyber attack of January 25, 2003, and the completion of the 1st stage of e-government , "e-Korea Vision 2006" has been revised or improved (see MIC 2003: 16). Thus, the government established the "Broadband IT Korea Vision 2007" in December 2003. This new plan adds some new projects to the previous plan and focuses on improving national productivity, in strengthening international competitiveness and individual quality of life through informatization ("digital welfare society", see MIC 2003: 16). It calls for a doubling of Korea's IT exports until 2007 and also envisions the commercialization of telematic applications, next generation computers and sophisticated service robots.

Part of this plan is also the Broadband Convergence Network (BcN) project which pursues the goal of building super-high-speed networks that will facilitate the integration of telecommunications and broadcasting services and of wired and wireless networks using high quality-of-services features and IPv6. The aim is to create an environment that allows users to access all products and services conveniently, regardless of the information transmission model (see Hwang, 2005). Convergence will mean that Koreans have seamless access to fast, robust information wherever they happen to be in the country. The new Korean network will likely to be one the first of its kind in the entire world and that other developed countries will likely be following the lead of Korea, implementing everything from Korean equipment (hardware components and handsets), to policy lessons pulled from the Korean experience.

Besides, with a goal to develop a new virtuous cycle, the Ministry of Information and Communication (MIC) drew up the IT839 Strategy (Under the value chain, the introduction of 8 new services will prompt investment into the building of 3 essential networks and these networks will pave the way for the 9 new sectors to grow fast, creating synergic effects.). ITU (2005) underlines the importance of this strategy for achieving a ubiquitous network society ("U-Korea"), and for sustaining industrial competitiveness. Compared to the previous foci of the key government initiatives which focussed mainly on simple IT investments and a strategy centered on outcomes and benefits of individual projects, the emphasis now is on a common basic structure such as architecture, standard, interoperability and interface (see: www.mic.gv.kr ). Considering the two recent government initiatives – BcN and IT 839 – one of the main aims of the Korean government ICT policies, which is expressed in the White Paper 2003 of the Ministry of Information and Communication is pursued: "We need to be at the forefront

of the digital revolution which is characterized by "digital convergence" and "ubiquitous" (MIC 2003: 11). Meanwhile, in order to construct a world’s best

information and communication infrastructure country, Korea : 1) completion of construction on a high speed information and communication network (155M-5Gbps) that connects 144 main cities nationwide in 2000 and construction of the world’s best information infrastructure. 2) Construction of the world’s best high-speed, user friendly internet with 26,270,000 internet users and 10,400,000 high speed internet users as of the end of 2001.

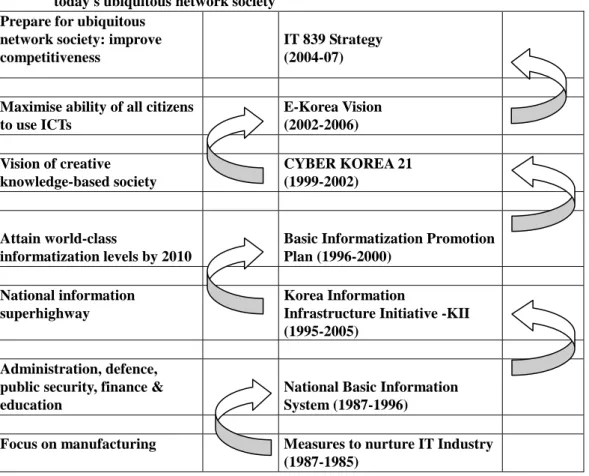

Figure 2: Government Push - Two decades of programmes designed to prepare Korea for today's ubiquitous network society

Prepare for ubiquitous network society: improve competitiveness

IT 839 Strategy (2004-07)

Maximise ability of all citizens to use ICTs E-Korea Vision (2002-2006) Vision of creative knowledge-based society CYBER KOREA 21 (1999-2002) Attain world-class informatization levels by 2010

Basic Informatization Promotion Plan (1996-2000) National information superhighway Korea Information

Infrastructure Initiative -KII (1995-2005)

Administration, defence, public security, finance & education

National Basic Information System (1987-1996)

Focus on manufacturing Measures to nurture IT Industry (1987-1985)

Source: ITU 2005, adapted from MIC Korea (see www.mic.gov.kr )

3.5 Performance: Towards ubiquitous content and network societies

The concept of the Korean ubiquitous network society includes that anyone, at anytime and anywhere may use any device, any service with any security to access information. Korea is a good example for studying the scope of such an approach, due to the very high ICT adoption there.

As early as 1993 the Korean government realised, that a nationwide fiber backbone would be vital for Korea's economic development. Rather than funding the backbone completely, the government invested about US $ 1 billion, and then agreed to become a

tenant on the line, to ensure sufficient demand (e.g. in government offices). The Korean experience shows, that governments can play a major role in network provision, by becoming a tenant on the line.

Korea is currently the world's broadband leader and the access is fast and the prices are among the lowest in the world. Broadband internet services were launched in July 1998. Until 2004 more than three-quarters of all households had a broadband subscription (24.9 broadband subscribers per 100 inhabitants) (ITU website, 2005). The regulatory environment in Korea enabled the exceptional growth in broadband penetration and service offerings. The open access policy has allowed for competition and lowered the prices. The market for broadband networks is competitive and extensive. Korea's competitive situation has contributed to the ambitious goals for universal, high-speed broadband access. Korea is among the few countries that have real competition at the infrastructure level.

Another way of promotion mobile success in Korea by the Korean government was the policy on handset subsidies. The Korean government instituted a policy were mobile providers were not allowed to lock subscribers into a two-year contract in exchange for a free handset. The government kept the maximum price providers were allowed to charge high enough, that mobile carriers could earn enough to pay the manufacturers for the handsets. This enabled them to buy phones in a bulk, reducing costs per unit and giving the away the mobile phones for free. The mobile triangle constitutes itself of the government, mobile operators and the equipment manufacturers. This helps to promote the settling of standards, policies and business models that ensure a dynamic market with high innovative activity. To complete the view on the Korean mobile market place, the additional services still have to be considered. Koreans use their mobile phones for various activities, such as internet, payment, banking, video applications, gaming etc. Therefore, they are open to take on new services and applications. This fosters the need for the provision of ubiquitous networks and access.

3.6 Concluding remarks

The Korean government has promoted the ICT industry for two decades as part of its strategy to diversify the electronics industry beyond consumer electronics. The three major sectors targeted were computers, semiconductors, and telecommunications. During the 1980s and 1990s, the Korean government employed a combination of import protection, financial subsidies, and R&D consortia to promote computer production (Dedrick and Kraemer, 1998). It also developed government computer networks to

promote computer use and create demand for domestic producers. Finally, in the 1990s, the government took steps to promote software development and has begun implementing a major plan called Korea Information Infrastructure (KII).

Korea's informatization plans were led by the government, not the private sector or the market. In other words, national informatization was pushes for through government's direct intervention, not through voluntary participation of the private sector (Kim 2005). Korea's industrial promotion policy using government budget and aids means that the government intervenes with the market in the process of resource allocation. In particular, the Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) has been leading the process. The MIC is responsible for creating an information society, promoting the IT industry, and regulating ICT services simultaneously. Therefore, it has incentives to use other policy means to achieve one policy objective.

Despite the success of Korea's ICT industry in recent years, Dedrick and Kraemer (1998) judge Korea's policy for the computer industry as less than effective. The development of effective ICT policy in Korea has been hampered in recent years by bureaucratic competition, similar to the situation in Japan. In addition, there has been a lack of focus as the government has directed resources into a broad range of hardware technologies. There has been no clear emphasis on leveraging Korea's strengths in components manufacturing, nor has the government effectively addressed shortcomings in design and software capabilities.

4. Taiwan Case

4.1 Characterization of Taiwan ICT sector

According to Mathews (1997: 30), Taiwan's ICT industry's growth and development within a favourable industrial ecology can be viewed as an institutional framework or dynamic structure that both facilitates and disciplines development of competitive firms. The ingredients of this ecology or system include:

• private sector firms – both small and large firms,

• inter-organizational structures, e.g. trade associations and product development consortia,

• government regulatory and coordination agencies, and • public sector research institutes and infrastructure.

In just 15 years, from the early 1980s, Taiwan has emerged as a leading producer of hardware for nearly every major computer vendor in the world, despite little previous experience in high-technology industries. In 1980, Taiwan had no computer production to speak of, and showed little evidence of comparative advantage in high-technology industries such as information technology. An important milestone in the development of Taiwan's ICT industry is the outreach of its constituent firms starting from the late 1980s, with their outward investment initially being directed towards Southeast Asia, and more recently towards China and elsewhere in the world (Chen and Liu 2002: 273). Thus, labour-intensive manufacturing that has dominated Taiwan's industrial sector since the mid-1960s, have gradually been replaced by capital and technology-intensive industries, such as chemicals, petrochemicals, ICT, electrical equipment and electronics. In 2000, laptop computers, monitors, PCs and motherboards accounted for about 80 percent of the production value of the IT industry.

For the past two decades, the government has been promoting emerging industries such as computer hardware and software, telecommunications, precision machinery, aerospace, energy, environmental industries, advanced materials and chemicals, life sciences, and biomedical industries. For Kraemer et al. (1996: 216), Taiwan's success in the computer industry has been due to a coordinated government strategy to support private entrepreneurship by a large number of small, flexible, innovative companies. The government has closely complemented the activities of the ICT companies in the international markets by carrying out research and development and transferring technology to the private sector, by conducting market intelligence for private sector use, and by providing engineering and technical manpower. Since the designation of information technology as a "strategic" industry in 1981, a broad range of policy

initiatives has been taken by government to support the computer industry, including incentives to the private sector, demand stimulation through government procurement, training of computer professionals, and support for R&D.

4.2 Supply Side Factors for ICT growth and fruitfulness

4.2.1 Education System and Human Capital

Faced with the fierce global competition of globalization in the 21st century, Taiwan must cultivate human resources with first-rate skills in design, production, and services in order to promote the development of knowledge-intensive industries.

Taiwan had a total of 162 higher education establishments in 2005 School Year (from 2005/8-2006/7), 89 of which were universities. The student population of higher education for the same year was 938,648 students, 449,695 of whom belonged to the science and technology field, including 2,165 doctoral students and 42,334 masters students (Ministry of Education website: www.edu.tw, 2006). Compared with other nations, Taiwan has a higher registration ratio, with education and training in accord with national competitiveness requirements (Tzeng and Lee, 2001). This advanced educational achievement has been one of the primary factors in the vigorous development of the information industry.

An overview of the Taiwan educational system reveals that, in 2004, the government allotted 39.0% of its budget to the higher education. Public education enrolment rates reached 99.2% in the 2004 School Year, an achievement that compares favourably with other nations. The incorporation of science into the compulsory curriculum and the development of students’ interest in technology also foster the rapid development of science.

4.2.2The Input of ICT

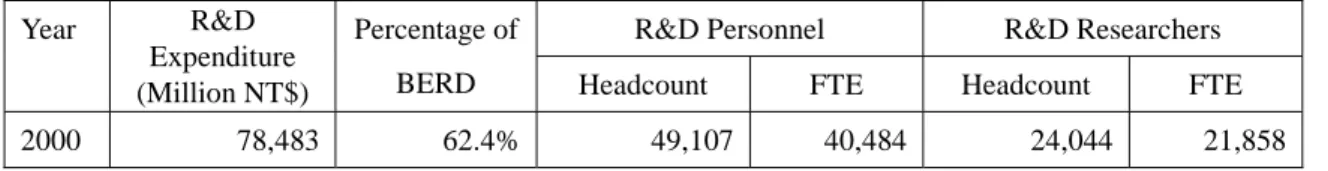

R&D investments in high-tech manufacturing industry accounts for 70.6% of all R&D investment, higher than all other main countries; this rate was 50.1% in 1995. In R&D investment by high-tech industry, office, accounting & computing machinery is 20.8% and television & communication equipment 45.4%, which are related to ICT, account for 66.2% of the total.

Table 3: R&D Expenditure and Personnel in the ICT Industry, 1999-2004 R&D Personnel R&D Researchers Year R&D

Expenditure (Million NT$)

Percentage of

BERD Headcount FTE Headcount FTE

2001 85,893 65.9% 51,069 43,034 26,609 24,992

2002 94,914 68.0% 57,328 46,789 30,265 27,157

2003 104,555 69.5% 63,882 51,895 32,940 30,002

2004 118,032 70.3% 69,421 57,686 36,410 33,385

Source: Indicators of Science and Technology (Table 2-2-7), Republic of China, 2005

Note: The range of ICT is based on the definition of the OECD Frascati Manual, 2002; FTE= Full-Time Equivalents.

Table3 shows that the R&D investment of domestic industries mostly centres on the ICT industry; the proportion of ICT R&D expenditures to whole-enterprise innovation expenditure reached 70.3% in 2004. However, the density of R&D investment in Taiwan’s high-tech manufacturing and ICT industries is relatively lower than other countries. This phenomenon may be related to the operational mode of Taiwan’s ICT industry, mostly OEM/ODM; though the operational scale of ICT-relevant industries is quite large, innovation investment is still relatively low.

4.2.3 Venture Capital

At the initial stages as Taiwan started to develop in the high-tech field, there was no venture capital business. Thus, the government established the Development Fund of Executive Yuan in 1973 to invest in venture capital and coordinated Chiang Tung Bank to provide refinance for venture capital. However, the preliminarily introduced venture capital created only a few successful cases that led the industrial development. The first venture capital company was established in 1984 after reinvestment by Acer. The number of venture capital companies increased slightly to the early 1990s The number of venture capital firms in Taiwan then grew to 259 in 2004. Their accumulated capital increased from NT$200 million in 1984 to NT$ 184.5 billion in 2004, growing over 922 times within two decades.

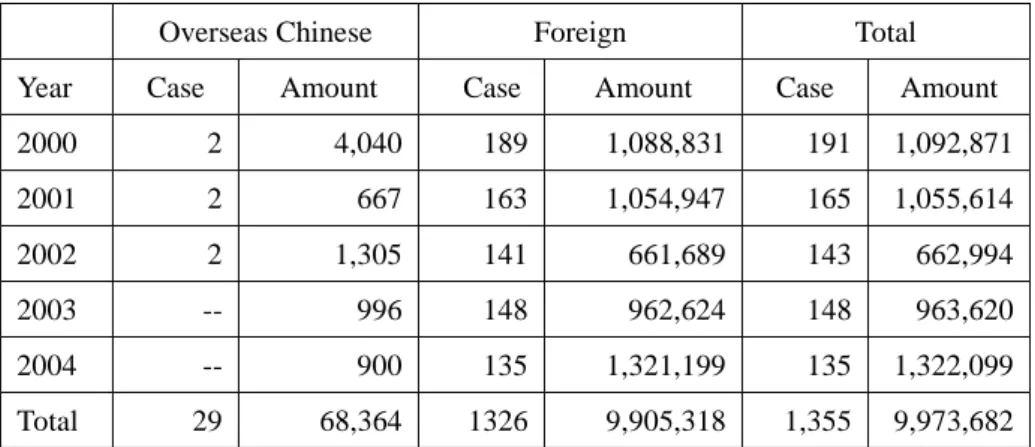

4.2.4 The status of FDI

The investment in Electronic & Electrical Appliances by overseas Chinese and foreign companies in Taiwan has had a tendency to rise gradually in recent decades. The year 2000 was a watershed, reflecting the first rotation of political party in Taiwan, and when FDI attained high levels. However, the political and economic situation after the political change (such as political infighting among parties, the economic emergence of Mainland China and India, etc.) was not as good as anticipated; and the cases and amounts of overseas Chinese and FDI have reduced year by year after 2001. In 2004 the total of approved cases dropped to the minimum since 2000 but increased considerably in amounts. This phenomenon was mainly because the government opened up an increasing range of sectors to foreign participation. This was particularly so in ICT, where

there were changes to foreign investment regulations, particularly in foreign ownership levels in the telecommunications sector.

Table 4 : Electronic & Electrical Appliances approved for Overseas Chinese and Foreign Investment in Taiwan, 1995-2004

Overseas Chinese Foreign Total

Year Case Amount Case Amount Case Amount

2000 2 4,040 189 1,088,831 191 1,092,871 2001 2 667 163 1,054,947 165 1,055,614 2002 2 1,305 141 661,689 143 662,994 2003 -- 996 148 962,624 148 963,620 2004 -- 900 135 1,321,199 135 1,322,099 Total 29 68,364 1326 9,905,318 1,355 9,973,682

Source: Annual Report of Overseas Chinese & Foreign Investment, Outward Investment and Mainland Investment, Investment Commission, MOEA (2004:23, 39)

4.2.5 Science-based parks

Taiwan’s science parks have the goals of attracting high-tech industries and manpower, encouraging domestic technological innovation, promoting industrial upgrading, balancing regional development, and achieving nationwide economic growth. The Hsinchu Science Park is a hotbed of the semiconductor and information industries; the Central Taiwan Science Park specializes in nanotechnology-based optoelectronics, aerospace, and precision machinery; and the Southern Taiwan Science Park is a stronghold of the optoelectronics industry. This science park system conforms to the government’s industrial development maxim of “ICs in the north, nanotechnology in the centre, and optoelectronics in the south”, and it fosters the emergence of dominant core industries. The objectives of science-based industrial parks are (a) to establish a base from which to develop high-tech industries, and (b) to cater exclusively to the needs of high-tech development, utilizing resources from industry, government, and academia to create an innovative environment that smoothly integrates R&D and manufacturing, and promotes the upgrading of Taiwanese industries, and (c) to improve links between technology generation and industrial diffusion of technologies.

4.3 Demand Side Factors for ICT 4.3.1 Deregulation of telecommunications

those regarding the Asia-Pacific Regional Operations Center and the National Information Infrastructure, and is opening up the island’s telecommunications market through a staged progression. In the first step toward liberalization, the ownership of terminal equipment by subscribers was opened up in 1987, thus initiating competition in the terminal equipment market. Later in 1989, the step taken was the opening of the market to value-added services so as to provide consumers with a diversity of such telecommunications services. The passage of three telecoms-related laws in 1996 led to the formal separation of the Directorate General of Telecommunications (DGT), which is in charge of telecommunications industry regulation, and the Chunghwa Telecom Co., which is responsible for operating the telecoms business. This separation more firmly established the policy directions for liberalization, and later further liberalization steps were taken particularly in services of mobile telecommunications and satellite telecommunications.

After 1999, liberalization has continued in various fields of services, such as integrated fixed network telecommunications, international submarine cable leased-circuit, local and long-distance leased-circuit cable, resale business, and third-generation mobile telecommunications (3G). The short-term objective of telecom liberalization is thus completed. After releasing 3G mobile telecommunication business to the public in 2002, the government released all telecommunication business and Taiwan’s telecom market has move into full liberalization.

In general, telecommunications liberalization policy in Taiwan has introduced competition mechanisms successfully, revitalizing the telecommunications industry structure and leading to the effective growth of telecommunications business. However the ratio of telecommunications revenues to GDP, though gradually increasing, is still below the world average of 3.4%, indicating that the domestic telecommunications market is not yet fully expanded.

4.3.2 ICT competitive Indicator

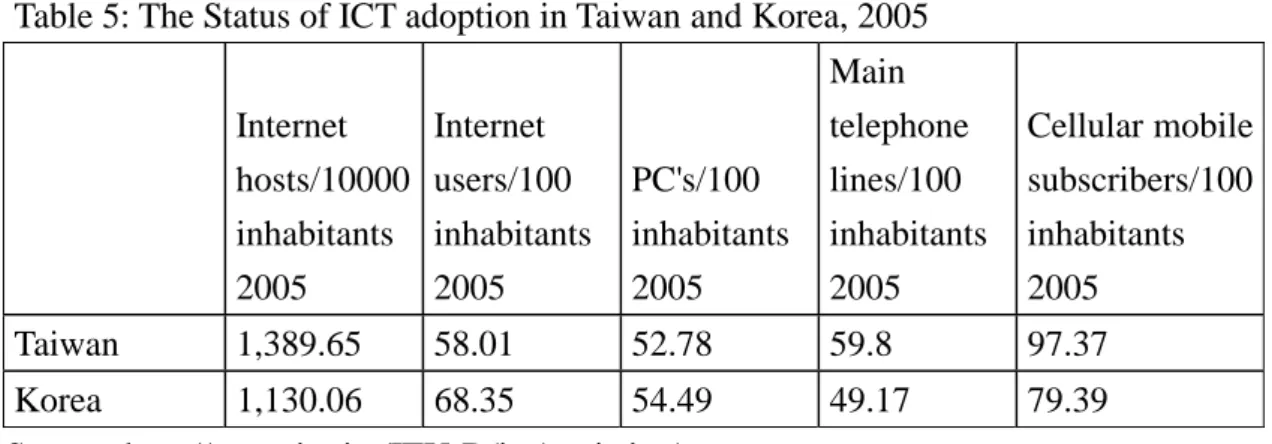

The Taiwanese economy changed heavily since the 80s. Today Taiwan has the fourth largest ICT hardware industry and semiconductor industry. While the penetration of fixed telephone lines developed slowly, mobile telephone services expanded with great speed since the year 1999 and nearly doubled between the years 1999 and 2001. The Internet penetration rate expanded rapidly as well which can be attributed to the availability of broadband services. While in the year 2001 only 35 % of the population had internet access, the availability increased and reached 54% in the year 2004.A good overview of the recent state of ICT ( in 2005) adoption provides the following table 5.

Table 5: The Status of ICT adoption in Taiwan and Korea, 2005 Internet hosts/10000 inhabitants 2005 Internet users/100 inhabitants 2005 PC's/100 inhabitants 2005 Main telephone lines/100 inhabitants 2005 Cellular mobile subscribers/100 inhabitants 2005 Taiwan 1,389.65 58.01 52.78 59.8 97.37 Korea 1,130.06 68.35 54.49 49.17 79.39 Source: http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/ 4.4 ICT Policy

4.4.1 Organizational and legal arrangement for an information society

The Taiwanese government integrates itself and the private sector to boost ICT development. Several organizations are commissioned by the government to promote ICTs. The two most important government planning and coordination bodies are the leading ministry in charge of economic development and industrial policy, the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) and the National Science Council (NSC). The Ministry of

Economic Affairs has a major role in technology policy, providing incentives for private

sector R&D, promoting technology imports, and supporting a number of research organizations. Actual implementation of industrial development and technology policy is centralized within the MOEA and its affiliates.

The National Science Council (NSC) is the highest government agency responsible for promoting the development of science and technology (S&T). The NSC draws up development policies and programmes, plans and implements basic and applied research, improves the research environment, and trains and recruits related manpower. Following the enactment of the Fundamental Science and Technology Act in 1999 and the Seventh National Science and Technology Conference in 2005, the NSC drew up the National Science and Technology Development Plan (2005-2008) and issued the White Paper on

Science and Technology (2003-2006). The National Information Infrastructure Enterprise Promotion Associate is the first non-profit organization in Taiwan to improve

its national information infrastructure and promote advanced applications. In addition, one of its objectives is to connect government's policies and private sector technology to promote ICTs and national information infrastructure. The Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), and the Institute of Information Industry (III) will be described more precisely in the following:

4.4.2 The Industry Technology Research Institute (ITRI)

At its establishment in 1973, ITRI was only an electronics research and development centre; however it became a ‘quasi-government corporation’ as a result of the accelerated upgrading of industrial technology and the promotion of industrial performance. Now, after 28 years, ITRI is composed of seven laboratories and nine research centres handling research in electronics, computers & telecommunications, energy & resources, mechanics, chemistry, optoelectronics, industrial safety and health, measurement standards, aviation and space, biomedical engineering, and materials science. In regard to ITRI’s budget, about a third of this comes from the private sector for contract research and various joint development projects, while two thirds come from various government sources (Mathews, 1997: 31). For years, ITRI served as a bridge between academic studies and industrial applications and provided strong backing to develop industries.

Since its inception in 1973, ITRI has played a major role in upgrading Taiwan’s industrial technology. ITRI created Taiwan’s semiconductor industry from scratch, led the development of its other high-tech industries, and helped traditional industries raise productivity, to catch up with advanced economies. ITRI participates in this role, fostering young companies and new technologies until they are able to survive on their own.

4.4.3 The Institute for Information Industry (III)

Since its inception in 1979, the Institute for Information Industry (III) has been a key technology contributor to Taiwan’s ICT industry, while also playing a vital role in promoting the adoption of ICT in both public and private sectors. Its founding mission, which continues today, was to increase Taiwan’s global competitiveness through the development of its information technology infrastructure and industry.

III’s current work can be summarized as aiding Taiwan in becoming a world-class ICT leader. This leadership involves not only having a vibrant ICT industry, but also ensuring that public and private institutions in Taiwan can take full advantage of the benefits of ICT, such as increasing productivity, raising efficiency, and improving quality of life.

Kraemer et al. (1996: 228) point out, that Taiwan has had a well-defined structure for policy formulation, coordination, and implementation. The actual implementation of industry and technology policy is centralized within the MOEA and its affiliates. Frequent consultation occurs at various levels with international experts, industry

associations, and industry leaders in this institutional structure. This chain of command has been empowered by the political leadership to design and implement a coordinated policy approach and has enabled Taiwan to develop a coherent strategy for its computer industry.

4.4.4 The role of universities

The Taiwanese government has always promoted cooperation between industries and universities in recent years; for example, the “TDP for Academia” which the Industrial Development Bureau in MOEA brought out is a best policy action scheme. The

interaction between industries and universities is largely confined to the supply of talent, the reasons being as follows:

• Taiwan has established an intact research system: The government has set up industrial science and technology research institutes such as ITRI and III to develop industrial technology, and transfers the technology to domestic proprietors, which serves as the backing for industrial R&D (especially for SMEs).

• For a long time, the major tasks government has given universities are teaching and research, not promoting the development of industries; that is to say, the incentive mechanism which the government offers leads the energy of universities to academic research, lacking contact with the foresight research required by industry. Accordingly, the industrial circles are short of inducements and opportunities to seek support from academic circles.

• Taiwanese universities and colleges have quite high proportions of high-level research manpower.

• In terms of “innovation”, the interaction between industries and universities and the degree of reciprocal support still have space to improve and be promoted.

4.4.5 Patents and related acts

In 1950, the National Bureau of Standard (NBS) was put in charge of patent and related affairs. Four years later, the NBS was also given the authority for trademark and related issues. Based on the 1993 "Guideline on Comprehensive IPR Protection Program", an agency responsible for IPR protection was established under the Ministry of Economic Affairs. In 1998, the Organisational Statute of the Intellectual Property Office was ratified and promulgated. In 1999, a reorganisation of the NBS into the Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) of the Ministry of Economic Affairs took place. The Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) is in charge of patent, trademark, copyright, integrated circuit layout, trade secret and other IP related affairs. Taiwan distinguishes three patent types: invention, utility model and design, with different patent terms for invention: 20 years for invention, 12 years for design and 10 years for utility model according to the Patent

Law from 2003. Trademarks are valid for 10 years after registration whereas copyright protection is the author's life plus 50 years. Integrated Circuit Layouts are protected for 10 years. The protection of intellectual property rights in order to support Taiwan's attractiveness, to upgrade industrial capacity and to remain globally competitive is a core element of Taiwan's national policy. The role of IP protection is supposed to be increasing in the context of a shift of the economic structure from a skill-intensive to knowledge-based. The general IP development is presented in action plans. The IPR Action Plan 2006-2008 focuses on the fulfilment of international responsibilities and improvement of legislation quality by comprehensive IPR legislation and policies, the support of IPR.-specific policy forces and facilities, on enhanced border controls and decreasing counterfeit and piracy product trade as well as on providing trainings, and promoting the use of licensed goods. Innovation and patenting are rewarded and education promotion programmes are strengthened. (TIPO website)

4.4.6 IC Policy

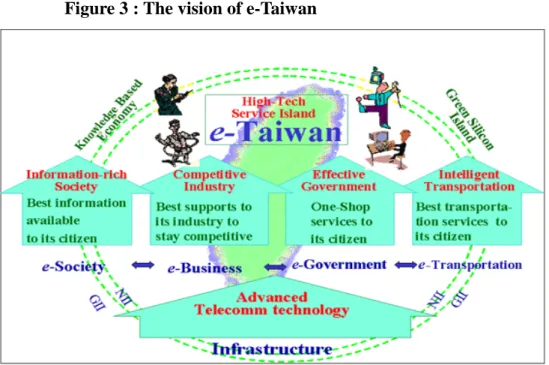

Regarding Taiwan’s ICT development also have fruitful outcomes. In June 2002, Taiwan government proposed the "Two-Trillion and Twin-Star" program to create the digital content one of the industries with annual production value of over NT$1 trillion. Facing the changes of the digital world, the Taiwan government has actively worked to promote digitization through a number of initiatives in recent years to improve the nation's IT proficiency and the competitiveness of domestic IT industries. In May 2002, the NICI and other government agencies worked together to launch the “E-Taiwan Program” as a part of the Challenge 2008 Program. There are five integral parts in this plan, i.e. “6 million broadband users”, “e-Society”, “e-Industry”, “e-Government” and “e-Opportunity”. “6 million broadband users” is expected to deliver the following results by 2007: (1) broadband network is fully installed with implementation of IPv6 and wireless LAN environment, (2) small & medium enterprises are mostly brought online, (3) safety standards, regulation, strategy and legislation are properly installed and in full operation, (4) IC security enforcement is strictly observed and capable of fostering the related industries, (5) CA cards have been successfully issued and commonly accepted as a primary means of identification.

With the need of a sound e-business framework and application standards, DOIT of MOEA commissioned ACI of III to undertake long-term research and promotion work with regard to the “E-Business Standard Research Plan”. Besides, in order to continually strengthen the enterprises’ digital capacities, “ABCDE Projects” aim to create an e-business supply chain system, lay the foundations for a new business model where "orders are received in Taiwan, production can take place anywhere in the

world".

Figure 3 : The vision of e-Taiwan

Source: NICI (2005). The vision of e-Taiwan.

The third IT revolution aims to forge the personal computers, internet and mobile communications into a "Ubiquitous Network". By utilizing this network, the government, entrepreneurs and end-users are able to get the information they need by any device, at any time and anywhere – more efficiently, more conveniently, and giving better quality of life. With the advantages of the world’s No.1 production value of WLAN products and mobile phone penetration rates, the Taiwan government has actively promoted Mobile-competitiveness. The National Information and Communication Initiative (NICI) committee of Executive Yuan (Cabinet), Ministry of the Interior (MOI) and Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) coordinated to propose the “M-Taiwan Program” with a budget of NT$37 billion in five years. The M-Taiwan Program is expected to build up the wireless networks, integrate mobile phone networks, set up optical-fibre backbones, and execute the Integrated Beyond 3rd Generation (iB3G) Double Network Integration Plan. It is also expected to shift Taiwan from an ‘e-nation’ to an ‘m-nation’, and to reach the vision of “Mobile Taiwan, infinite application, and a brave new mobile world”. This project has three core aspects: m-Life, m-Service and m-Learning.

The industry value of ICT hardware sector and IT software sector respectively is 684.1 and 49.4 hundred million US$ in 2004. And the proportion of ICT expenditure to GDP is 1.7% in 2004. And the According to the survey conducted

by FIND of III, the Internet subscribers (Internet access accounts) in Taiwan reached 9.98 million as of December 2004. In 2004, 61% of households in Taiwan have connected to the Internet, and 81% of Taiwan enterprises have Internet accesses. In 2004, the bandwidth used for international Internet connection in Taiwan exceeded 70 Gbps; there were over 5 million Mobile Internet subscribers in Taiwan; Taiwan government has offered 847 government services online as of the end of 2004

(FIND website, Taiwan).

4.5 The current status of the Information Society in Taiwan

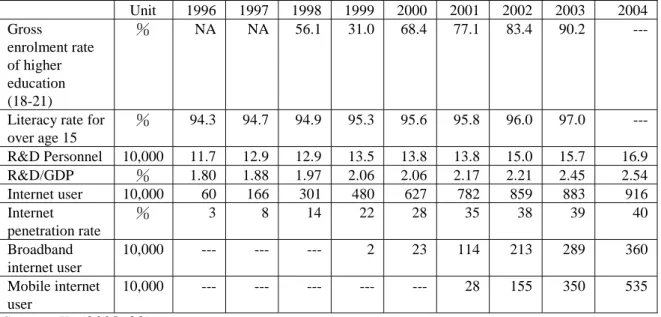

Table 6: Status of Education, R&D, and Internet Application in Taiwan,1996-2004 Unit 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 Gross enrolment rate of higher education (18-21) % NA NA 56.1 31.0 68.4 77.1 83.4 90.2

---Literacy rate for over age 15 % 94.3 94.7 94.9 95.3 95.6 95.8 96.0 97.0 ---R&D Personnel 10,000 11.7 12.9 12.9 13.5 13.8 13.8 15.0 15.7 16.9 R&D/GDP % 1.80 1.88 1.97 2.06 2.06 2.17 2.21 2.45 2.54 Internet user 10,000 60 166 301 480 627 782 859 883 916 Internet penetration rate % 3 8 14 22 28 35 38 39 40 Broadband internet user 10,000 --- --- --- 2 23 114 213 289 360 Mobile internet user 10,000 --- --- --- --- --- 28 155 350 535 Source: Ke (2005: 29)

Note: 1. Broadband Internet users include xDSL, Cable Modem, Fixed Line with Fibre Connection

2. Mobile Internet users include WAP, GPRS, PHS or 3G

After cultivating IT for so many years, Taiwan has made great progress in informational social readiness, as shown in education, R&D quality and internet penetration rate (Table 6).

1. Education: In 1992, the gross enrolment rate of high education was 90.2% which was no worse than most developed countries, typically between 50% and 80%. In 2003, the literacy rate for those over 15 in Taiwan reached 97%.

2. R&D quality: In 2004, the number of researchers in Taiwan was about 169,000; annual papers in the SCI came to 12,939; annual papers in EI were 10,980; numbers of US patents (excluding “New Design”) was 5,938; and R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP (excluding defence) was 2.54 and rising.

3. Internet: the number of Taiwan’s internet users was 12.21 million in 2004; 54% of the Taiwan citizens had used the Internet, increasing by 2% compared with the previous year’s result of 52%. Taiwan’s home PC penetration rate increased slightly from 71% in 2003 to 73% in 2004. According to III’s survey, in 2004, 61% of households in Taiwan have connected to the internet, and 78% of the online households use broadband internet connections. Broadband subscribers in Taiwan reached 3.57 million as of the end of 2004 (DSL subscribers 89% and Cable modem subscribers 11%). Besides DSL and Cable modem, there are 30,000 Leased-line and FTTx subscribers in Taiwan.

4.6 Assessment of Taiwan's ICT policy mix

Taiwan's government has played a critical function in supporting the ICT industry, by developing technology, providing market intelligence, and training engineers and computer professionals. Its role has been to fill the gaps in the capabilities of the private sector, while letting the private sector make its own investment and production decisions. This approach has been effective in tapping the energy of Taiwan's entrepreneurs rather than trying to direct the industry from above. Taiwan's government has consolidated most policies for computer production and use under the Ministry of Economic Affairs and its affiliated institutions (primarily the Industrial Development Bureau, III, and ITRI). This is not to say that there are no complaints about Taiwan's policy institutions. The private sector complains about competition from ITRI and III, claiming that ITRI subsidizes research that is then spun-off into commercial products by its own engineers, and that III competes unfairly for government service contracts. But, Taiwan has been able to avoid the bureaucratic competition that has marked Japan and Korea, and it has usually worked with and through the private sector to make and implement policy. The government has also tapped the knowledge of overseas Taiwanese and foreigners to guide its policymaking, thus avoiding the insularity that sometimes afflicts Japan and Korea.

4.7 Government-Industry collaboration and coordination

Taiwan's technology policies have been described as "diffusion oriented", with the "principal purpose of diffusing technological capabilities throughout the industrial structure, thus facilitating the ongoing and mainly incremental adaptation to change" (Ergas, 1986). This focus on flexible adaptation to change is a hallmark of both government and company strategy in Taiwan. Taiwan's companies take advantage of a highly flexible, varied, and geographically clustered manufacturing structure to respond rapidly to market opportunities mainly created by U.S. and Japanese market leaders – the "fast follower" strategy. The government has compensated for the liabilities caused

by the small size of companies by providing technology, capital, and market intelligence geared to the dynamics of the market. Government policies are developed with broad participation by the public and private sectors and are continuously modified to respond to changing conditions. The strategy for technology development differs from Japan and Korea, whose government policies encourage large firms to conduct R&D themselves or through government-industry consortia. In Taiwan, most firms lack the resources to undertake large R&D projects, so the government has taken a more direct role, creating public institutions that conduct research and disseminate technology to the private sector.

References

FIND website, 2005/12/17, http://www.find.org.tw/eng/index.asp

Hobday, M. (1995), Innovation in East Asia: the challenge to Japan, Edward Elgar, Aldershot. ITU (2005), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators, ITU.

Ke, J.S. (2005), Improving Information Society, Strengthening e-Competitiveness,

Information Society Review, Initial Issue, Taipei: III.

Mathews, J.A. (1997), A Silicon Valley of the East: Creating Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry, California Management Review, Vol.39, No.4, pp.26-54.

KISDI (2005), IT Industry Outlook of Korea 2005, Korea

MIC website, 2005/12/15, surfed on the website of http://www.mic.go.kr/index.jsp TIPO website: http://www.tipo.gov.tw/

UNESCAP(2004) , Good Practices in Information and Communication Technology Policies in Asia and the Pacific (2005): Promotion of Enabling Policies and Regulatory Frameworks for Information and Communication Technology Development in the Asia-Pacific Region ,New York. March 2006 download: http://www.unescap.org/publications/detail.asp?id=1051

Young, A. (1995), ‘The tyranny of numbers: confronting the statistical realities of the East Asian growth experience’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 641-80.