行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

心理擁有感的前因與情境(第 2 年)

研究成果報告(完整版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 96-2416-H-004-005-MY2 執 行 期 間 : 97 年 08 月 01 日至 98 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學企業管理學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 韓志翔 計畫參與人員: 博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:江旭新 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 98 年 11 月 12 日

Psychological Ownership: Its Antecedents and Conditions

Abstract

Compared to extensively studied topics in organizational behavior (OB) (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment etc.), psychological ownership is a new construct recently attracting the attention of academics. Nevertheless, relative to other mature area of study in OB, there exists large room to improvement in the field of psychological ownership in terms of quantity and quality. Along with the growth of knowledge-intensive work, monitoring and motivating these employees become more and more difficult than that under the conditions with conventional labor-intensive jobs. Thus, in recent years, new incentive schemes (e.g., profit sharing, employee stock ownership etc.) and participative management have been adopted by many business firms, in particular in high-tech industries. These new incentive schemes and management styles have been proved to positively affect employees’ attitude and behaviors, as well as performance. However, relatively few studies have investigated the psychological process variables (e.g., psychological ownership) and conditions that may enhance this psychological state. Therefore, this study proposes an integrative model for the antecedents and conditions for psychological ownership. Based on analytical results, employee participation in decision making, perceived organizational insider, person-organization fit, and perceived organizational support are positively related to psychological ownership. Education is negatively related to psychological ownership. Important implications for academics and practitioners in a knowledge economy follow.

Introduction

With the coming of knowledge-based economy, high-skilled workers have become critical resources for achieving competitive advantage (Pfeffer, 1994). However, greater mobility among high-skilled workers also shifts the balance of the employment relationships between employees and employers (Arthur, Inkson, & Pringle, 1999), especially in high-technology firms (Rousseau & Shperling, 2003). That is, high-technology firms become increasingly dependent on high-skilled workers and, employers make significant efforts often by providing incentives to attract and retain these employees. Typically the incentives are oriented towards employee stock ownership programs, that align employees’ shared financial interests with the organization, and strengthening employees’ feeling of being owners of the business (Wagner, Parker, & Christiansen, 2003). Hence, the issue of highly-skilled employees experience the feeling of psychological ownership for the organization has been important for both academic and practical fields (Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004). Psychological ownership is the psychologically experienced phenomenon in which an employee develops possessive feelings for the target (e.g., the organization) (Pierce, Kostova, & Dirks, 2003). Recent studies have demonstrated that psychological ownership leads to higher organizational commitment, job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior (Vandewalle, Van Dyne, & Kostova, 1995), and overall organizational performance (Wagner et al., 2003). However, the antecedents of psychological ownership did not appear to have been addressed in current literature.

ownership: controlling the target, coming to intimately know the target, and investing the

self into the target. However, studies building on this approach have only tested the

connection between “controlling the target” and psychological ownership (e.g., Pierce, O’Driscoll, & Coghlan, 2004). The linkage and empirical evidence of a connection between the other two routes (i.e., coming to intimately know the target and investing the self into the target) and psychological ownership remains untested. An organization may adopt practices that let employees have rights to participate in organizational decision making in order to integrate the interests and goals of employees and the organization (Rousseau & Shperling, 2003). Employees who have right to control over the target may experience the target as a part of self which is regarded as the route of psychological ownership (Pierce, Rubenfeld, & Morgan, 1991). The extent to which employees invest themselves into the target is regarded as the third route to psychological ownership (Pierce et al., 2001). That is, those employees who invest themselves into the organization may produce psychological ownership. As argued by Zardkoohi and Paetzold (2004), those employees who have a higher level of general human capital (i.e., higher education) can apply their skills easily in other organizations, and then reduce the feeling of psychological ownership toward an organization. The antecedents of psychological ownership, which include employee participate in decision making, employees’ tenure, and employees’ education, are less discussed by prior research, representing another research gap needed to be explored.

This study extends Pierce et al.’s (2001) psychological ownership model in four ways. First, we examined the relationships of three routes to psychological ownership in one study. Thus we could fill the research gap described above by testing the effects of

the other two routes in Pierce et al.’s (2001) model. Second, Pierce et al. (2003) and Van Dyne et al. (2004) have appealed for more research to test the generalizability of psychological ownership in collectivist cultures. In order to echo the call, this study was conducted in Taiwan where collectivism is a cultural norm (Hofstede, 1997). Third, to explore the emergence of psychological ownership amongst high-skilled employees (Rousseau et al., 2003), we chose R&D employees of high-technology firms since this seemed appropriate to achieve sample relevance (Sackett & Larson, 1990). Hopefully, we can echo recent suggestions, and further explore the boundaries of psychological ownership model (Whetten, 1989).

Theory and Hypotheses

Psychological ownership for the organization

According to Dittmar (1992), it is common for people to psychologically experience the connection between self and various targets of possession. Possessions (i.e., feeling as though an object, entity, or idea is ‘MINE’ or ‘OURS’) plays an dominant role in the owner’s identity that turns into a part of the extended self. Furby (1978) and Rudmin and Berry (1987) also argued that the core of psychological ownership is a sense of possession. Drawing from above arguments, Pierce et al. (2001, 2003) defined psychological ownership as the state in which an individual feels that an object (i.e., the organization) is experienced possessively (i.e., it is ‘MINE’ or it is ‘OURS’). In this study, we focus on the organization as the target of psychological ownership and explore the “routes” to psychological ownership in the next section.

Antecedents to Psychological Ownership

How could employees come to experience psychological ownership towards the organization? Pierce et al. (2001) theorized three major routes (i.e., paths or mechanisms) through which psychological ownership emerges. The first route to psychological ownership is the amount and the ability to control over the target. When individuals perceive they have increasing amounts of control over the target then, the more the target is experienced as a part of self (Pierce et al., 1991). Organizations can provide employees with many opportunities to have control over the organization. For example, Wagner et al. (2003) proposed that employees who participate in profit sharing plans would have the feeling of control over the organization. This practice helps to integrate the interests and goals of employees and the organization (Rousseau & Shperling, 2003). Additionally, employee stock ownership plans also produce positive social-psychological effects owing to the right of employees to be the owner of organization (Culpepper, Gamble, & Blubaugh, 2004). Therefore, employees who have rights to participate in decision making may produce the feeling of psychological ownership.

Ownership typically entails a right to influence decisions. Having the authority to make decisions is perhaps the most powerful way to achieve a sense of ownership (Rousseau & Shperling, 2003). When the organization allows employees to have influence over organizational decisions or procedures, then it is more likely that employees will feel that “This is MY organization”. Employees who have the authority to participate in decision making about job contents not only experienced higher level of

perceived control (Pierce et al., 2004), but also identified with and involved in the organization more (VanYperen, van den Berg, & Willering, 1999). To sum up, we propose:

Hypothesis1 . The level of employee participation in decision making is positively related

to psychological ownership for the organization.

The third route to psychological ownership is the extent to which employees invest themselves into the target. The more employees invest themselves into an organization, the stronger their psychological ownership for the organization emerges (Pierce et al., 2001). Employees’ self-investment comes in many forms, including investment of one’s time, physical energy, opportunity costs, and so on. From the viewpoint of side-bet theory (Becker, 1960), employees gain seniority and status with the organization through increased tenure (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Greater periods of tenure reflect employees’ increasing investment in time and effort in the same organization, and is associated with related costs of leaving (Cohen, 1993). Therefore, employees’ tenure can be seen as a proxy of investment towards the organization. Building on these arguments, we propose:

Hypothesis 2. Employees’ tenure is positively related to psychological ownership for the

organization.

The length of time spent in education is a kind of self-investment in general human capital (Smith, Collins, & Clark, 2005). However, when employees invest time and effort

in their education or profession, the benefit will accrue to their professional identity rather than the organization explicitly (Blau, 2003). Zardkoohi and Paetzold (2004) also argued when employees have a higher level of general human capital, their voluntary turnover intention will be higher since they can apply their skills easily in other organizations. Therefore we assert that the more years employees invest in education may reduce their psychological ownership for organization.

Hypothesis 3. Employees’ years of education are negatively related to psychological

ownership for the organization.

Conditions for psychological ownership

Person-organization (P-O) fit is an organizational behavior (OB) construct which has attracted increasing attention from academics in OB areas in recent years. It refers to the compatibility between individual employees and their organizations (Kristof, 1996). This compatibility manifests itself in the match between individual needs and their organization’s contributions that generate perceptions of fit. Drawing on the needs-supplies theory, Kristof (1996) argued that organizations may utilize their resources and provide opportunities to fulfill employees’ needs. These resources and opportunities include financial, physical and psychological resources as well as social rights (e.g., training opportunities, economic benefits), which can strengthen individual employees’ perceptions of organizational membership status due to high-degree perceptions of need fulfillment. When individual employees develop such perceptions, they tend to feel like an important insider in their organizations, which will enhance their

experiences of possession of their organizations. Thus, we propose that,

Hypothesis 4. The degree of P-O fit is positively associated with psychological ownership.

Perceived organizational support (POS) refers to the extent to which employees perceive their organizations value their contributions and care about their well-being (Eisenberger et al., 1986). Organizations can adopt policies and practices that are perceived by employees as supportive (e.g., training opportunities, fair procedures, due process, benefits etc.) to enhance employees’ perceptions of being valued and cared (Eisenberger et al., 1997). Once employees perceive that they are valued and cared by their organizations, they tend to generate a sense of mattering and hence strong perceived organizational membership. As Master and Stamper (2003) stated, perceived organizational membership is highly associated with the concept of psychological

ownership. Hence, we hypothesize that,

Hypothesis 5. Perceived organizational support is positively related to psychological ownership.

Organizational identification refers to employees’ perceptions of belonging to their organizations. Based on social identity theory, stating that people tend to classify themselves and others into various social groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1985), employees who strongly identify with their organizations tend to define themselves as the organizations’

members, becoming psychologically intertwined with the organization and sharing in its successes and failures (Mael & Ashforth, 1995). Perceived insider status refers to employees’ perceptions of being treated as organizational insider by their superiors (Stamper & Masterson, 2002). Perceived insider status shows that employees have a place inside their organizations and are accepted by their organizations. According to Pierce et al. (2001), psychological ownership represents that employees perceive they have a place inside the organizations. Thus, we hypothesize that,

Hypothesis 6. Perception of insider status is positively related to psychological ownership.

The level of position employees hold may be associated with psychological ownership. In general, employees holding high-level positions inside the organization usually have more power and influence on organizational decisions. Furthermore, these high-level employees have more discretion and autonomy over the work they perform. Hence, they may feel more about the ownership of their work and/or organizations. Thus, we hypothesize that,

Hypothesis 7. The level of position in the organizational is positively related to psychological ownership.

Method

Participants for this study were R&D employees randomly chosen from 8 high-technology firms in Taiwan. To ensure that the firms in the sample had similar basic environmental characteristics, we adopted to Smith et al.’s (2005) approach to check if the sample firms conformed to Milkovich’s (1987) definition of high-technology firms. That is, these firms should emphasize invention and innovation in their business strategy, deploy a significant percentage of their financial resources to R&D and, employ a relatively high percentage of scientists and engineers in their workforce (Milkovich, 1987: 80).

We contacted these companies by telephone to ascertain their mailing address. Given the considerations of the cost and willingness to cooperate, we sent 35 questionnaires to 20 firms. A total of 600 questionnaires were mailed, and 239 valid questionnaires were returned and that equated to a valid response rate of 39.8 percent. Participants were predominantly male (52.4 percent). Most participants (62 percent) graduated from university. Eighty-three percent of the respondents had less than nine years organizational tenure.

Measures

In order to ensure the content validity of measurements (Schwab, 2005), all measurements were translated into Chinese by the authors, and then reviewed by five experts who majored in organizational behavior to assess the appropriateness and adequacy of the translation.

Psychological ownership for the organization: Psychological ownership for the organization was measured with Van Dyne and Pierce’s (2004) scale.

Employee participation in decision making: We adopted six items from Locke and Schweiger’s (1979) scale to measure the level of participation in decision making. Respondents were asked to evaluate the degree of employees’ participation in following decisions: the change of work flow, altering of work procedure, the design of job content, managing job rotation, setting working hours, and establishing work rules. Responses were made on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all; 1 = My supervisor provided me with related

information but I did nothave the right to express my opinions; 2 = I had the right to express my opinions; 3 =My supervisor discussed the decision with me; 4 = The decision was made by me and my supervisor altogether).

Employees’ tenure and years of education: In order to collect the data about employees’ tenure, respondents were asked to fill out the number of years that they had worked in their current organization. As for the year of education, respondents were asked to fill out their level of education. Then the authors calculated and translated this data into the years of education.

Person-organization fit. This study proposes to adapt the items used by Kristof (1996) to measure person-organizational fit. Five-point Likert scale will be used to measure the extent of person-organization fit.

Perceived organizational support. This study proposes to adapt the items used by Eisenberger et al. (1997) to measure perceived organizational support. Five-point Likert scale will be used to measure the extent of person-organization fit.

Perceived insider status. This study proposes to adapt the items used by Stamper & Masterson (2002) to measure perceived insider status. Five-point Likert scale will be used to measure the extent of perceived insider status.

Validity of measures

To evaluate the discriminant and convergent validity of measures, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using LISREL 8.52. With a maximum likelihood estimation, we compare the fit of a one-factor model (all items in this study were loaded on a common factor) and a five-factor model (psychological ownership, employee participation in decision making, perceived organizational insider, person-organization fit and perceived organizational support) (see Korsgaard & Roberson, 1995).

Results

Discriminant and convergent validity

Matrix phi was utilized by this study to understand the degree to which a construct is really distinct from other constructs. According to Jöreskog and Sörbom (1981), they pointed out that one concept was distinct from another if PHI+1.96 * standardized error

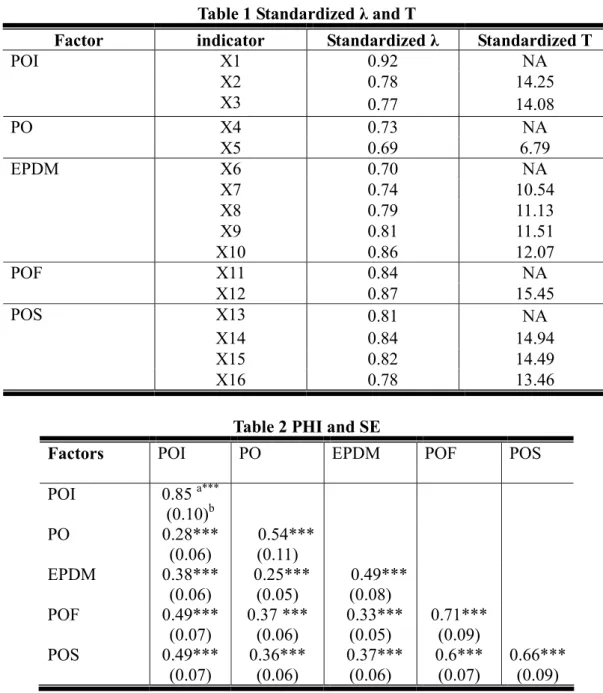

excluded 1. As reported Table 1, the discriminant validity existed among constructs. Furthermore, convergent validity represents the degree to which measures of the same concepts are correlated. According to results showed in Table 2, values of standardized λ and T indicated every construct had convergent validity.

Table 1 Standardized λ and T

Factor indicator Standardized λ Standardized T

X1 0.92 NA X2 0.78 14.25 POI X3 0.77 14.08 X4 0.73 NA PO X5 0.69 6.79 X6 0.70 NA X7 0.74 10.54 X8 0.79 11.13 X9 0.81 11.51 EPDM X10 0.86 12.07 X11 0.84 NA POF X12 0.87 15.45 X13 0.81 NA X14 0.84 14.94 X15 0.82 14.49 POS X16 0.78 13.46 Table 2 PHI and SE

Factors POI PO EPDM POF POS

POI 0.85 a*** (0.10)b PO 0.28*** (0.06) 0.54*** (0.11) EPDM 0.38*** (0.06) 0.25*** (0.05) 0.49*** (0.08) POF 0.49*** (0.07) 0.37 *** (0.06) 0.33*** (0.05) 0.71*** (0.09) POS 0.49*** (0.07) 0.36*** (0.06) 0.37*** (0.06) 0.6*** (0.07) 0.66*** (0.09) a PHI,bStandardized Error

Common method variance

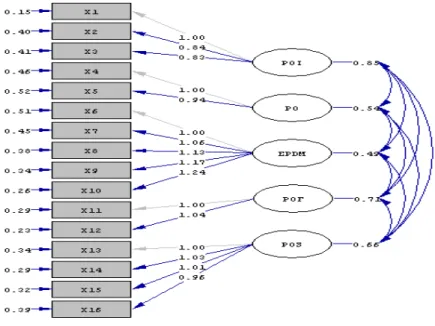

Figure 1 Measure Model

Confirmative factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to examine validity of this study. Two steps were processed to examine model validity. First, all items were concluded to one general factor, and analytical results for fitness included: χ2= 2654.76; D.F. = 299; CFI= 0.88; GFI= 0.54; NNFI= 0.86; RMSEA=0.18, representing that the fitness of one-factor model was poor. Second, all items were measured according to five-factor model. As showed in figure 1, the analytical results for fitness included: χ2= 198.35; D.F. = 94; CFI= .98; GFI= 0.91; NNFI= .98; RMSEA=0.068, indicating fitness of five-factor model was sufficient. Based on above-mentioned results, the problem of common method variance was solved.

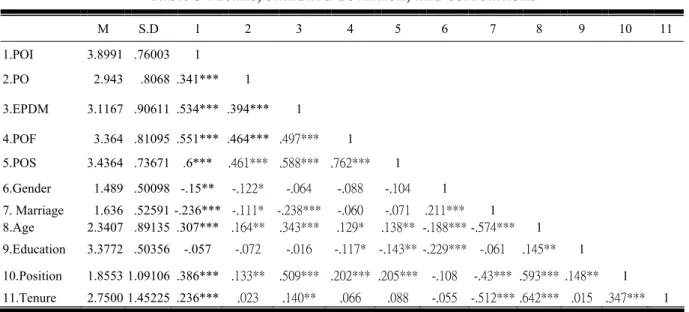

Table 3 Means, standard deviation, and correlations

1. * P<0.1, **P<0.05, ***P<0.01

2. POI: Perceived Organizational Insider; PO: Psychological Ownership; EPDM: Employee Participation in Decision Making; POF: Person-organization Fit; POS: Perceived Organizational Support

After analyses, Cronbach’s α for each construct, which included perceived organizational insider, psychological ownership, employee participation in decision making, person-organization fit, perceived organizational support, was 0.85, 0.71, 0.88, 0.85, 0.89 respectively. The results revealed that stability of this study was sufficient. Table 3 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations. The means from high to low are perceived organizational insider, perceived organizational support, person-organization fit, employee participation in decision making, and psychological ownership. Correlations reported in Table 3 shows that psychological ownership is positively related to perceived organization insider (r=0.341***, P<0.01), employee participation in decision making (r=0.394***, P<0.01), person-organization fit (r=0.464***, P<0.01), perceived organizational support (r=0.461***, P<0.01), age (r=0.164**, P<0.05), and position (r=0.133**, P<0.05). Psychological ownership is positively related to tenure, but not significant. Furthermore, psychological ownership is

M S.D 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1.POI 3.8991 .76003 1 2.PO 2.943 .8068 .341*** 1 3.EPDM 3.1167 .90611 .534*** .394*** 1 4.POF 3.364 .81095 .551*** .464*** .497*** 1 5.POS 3.4364 .73671 .6*** .461*** .588*** .762*** 1 6.Gender 1.489 .50098 -.15** -.122* -.064 -.088 -.104 1 7. Marriage 1.636 .52591 -.236*** -.111* -.238*** -.060 -.071 .211*** 1 8.Age 2.3407 .89135 .307*** .164** .343*** .129* .138** -.188*** -.574*** 1 9.Education 3.3772 .50356 -.057 -.072 -.016 -.117* -.143** -.229*** -.061 .145** 1 10.Position 1.8553 1.09106 .386*** .133** .509*** .202*** .205*** -.108 -.43*** .593*** .148** 1 11.Tenure 2.7500 1.45225 .236*** .023 .140** .066 .088 -.055 -.512*** .642*** .015 .347*** 1

negatively related to gender (r=-0.122*, P<0.1) and marriage (r=-0.111*, P<0.1). Psychological ownership was negatively related to education, but not significant. The above-mentioned results are consistent with hypotheses proposed by this study, revealing that these relationships require further exploration.

Regression Analysis

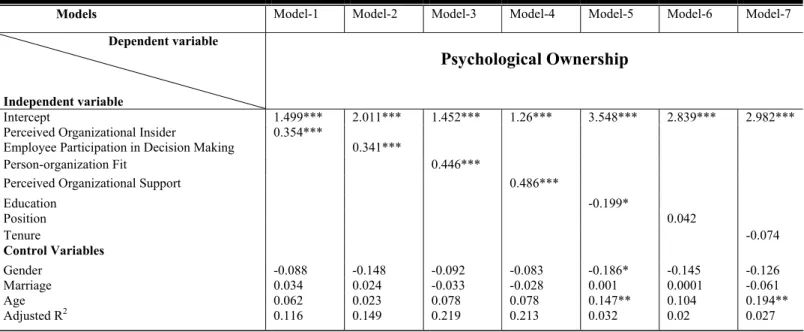

Table 4 Regression Analysis

* P<0.1, **P<0.05, ***P<0.01

Based on results in Table 4, psychological ownership is positively affected by employee participation in decision making (β=0.341***, p<0.01), person-organization fit (β=0.446***, p<0.01), perceived organizational support (β=0.486***, p<0.01), and perceived organizational insider (β=0.354***, p<0.01), indicating that hypothesis 1, 4, 5, and 6 were supported. Furthermore, psychological ownership is negatively affected by

Models Model-1 Model-2 Model-3 Model-4 Model-5 Model-6 Model-7

Dependent variable

Independent variable

Psychological Ownership

Intercept 1.499*** 2.011*** 1.452*** 1.26*** 3.548*** 2.839*** 2.982***

Perceived Organizational Insider 0.354***

Employee Participation in Decision Making 0.341***

Person-organization Fit 0.446***

Perceived Organizational Support 0.486***

Education -0.199* Position 0.042 Tenure -0.074 Control Variables Gender -0.088 -0.148 -0.092 -0.083 -0.186* -0.145 -0.126 Marriage 0.034 0.024 -0.033 -0.028 0.001 0.0001 -0.061 Age 0.062 0.023 0.078 0.078 0.147** 0.104 0.194** Adjusted R2 0.116 0.149 0.219 0.213 0.032 0.02 0.027

education (β=0.199*, p<0.1), revealing that hypothesis 3 was supported. However, psychological ownership is positively affected by position ( β=0.042, p>0.1) and negatively affected by tenure (β=-0.074, p>0.1), but not significant. The results revealed that hypothesis 2 and 7 were not supported.

Discussion

According to Pierce et al. (2001), three roots of psychological ownership include having a place or home, efficacy and effectance, and self-identity. Employees with psychological ownership may produce three traits which include positive attitudes, self-concept, and sense of responsibility toward a target (Van Dyne et al., 2004). However, few studies investigate organizational mechanisms that induce psychological ownership of employees. Based on results, employee participation in decision making positively influences employee psychological ownership which is important to arouse positive employee attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, it is important for an organization to allow employees to participate in decision making and then make employees benefited from these procedures. Psychological ownership is positively affected by person-organization fit which is regarded as the important factor that may awaken employee’s altruistic spirit and then contribute to job performance. Therefore, an organization may utilize practices of person-organization fit to select employees who have similar personal values that contributes to psychological ownership. Furthermore, the result that perceived organizational support positively contributes to psychological ownership represents that employees who perceive organizational support may generate affective attachment that

contributes to psychological ownership. An organization may adopt policies and practices that make employees perceive that they are supported valued and cared (Eisenberger et al., 1997). The result that perceived organizational insider also positively influences psychological ownership is consistent with arguments of Pierce et al. (2001). It revels that employees who perceive they have a place inside the organization may produce psychological ownership. As argued by Blau (2003), employees who invest time and effort in their education, the benefit will accrue to their professional identity rather than the organization explicitly, and the argument is proved by the analytical result.

Implication

Several critical implications are discussed as follows. First, based on the result of Hypothesis 1, employee participation in decision making is positively related to psychological ownership, revealing that employees who have rights to participate in decision making produce higher sense of psychological ownership that contributes to positive behaviors in employees’ day-to-day operations. That is, employees who frequently interact with customers in daily jobs may give good suggestions to their organization when they have right to participate in decision making. Second, the result of H4 represents that person-organization fit positively contributes to psychological ownership of employees. It shows that an organization can recruit employees with high person-organization fit because employees with high person-organization fit may produce a positive feeling toward their organization. In fact, an organization may utilize HR practices to improve employees’ cognitions of person-organization fit that may inspire

psychological ownership of employees. Third, the result of H5 represents that perceived organizational support positively contributes to psychological ownership. That is, when employees perceive that they are valued and cared by an organization, they may produce psychological ownership. Therefore, an organization may adopt HR practices (such as promotion and compensation) to make employees perceive that they are valued and cared, and then contribute to employees’ positive behaviors. Fourth, the result of H6 shows that perceived organizational insider positively contributes to psychological ownership. That is, it is important for an organization to make employees perceive that they are organizational insiders. Employees who identify their organization to define themselves as organizational members may psychologically intertwine with the organization, and then contribute to an organization. Fifth, the result of H3 shows that psychological ownership is negatively affected by education, which is consistent with arguments that employees with higher level of general human capital may apply their skills easily in other fields or organizations (Zardkoohi et al., 2004). Therefore, an organization may adopt HR practices (e.g., high salary, compensation, reward etc.) to retain those employees who have a higher level of general human capital.

Contribution

Antecedents and conditions of psychological ownership, which were less discussed by prior research, were investigated by this study to foster theory of psychological ownership. As for antecedents of psychological ownership, the level of employee participation in decision making is positively related to psychological ownership and

employees’ years of education are negatively related to psychological ownership. Based on the results, an organization may understand to adopt policies and procedures enhance psychological ownership. For example, an organization may let employees participate in decision making and reward employees with high education in order to make employees produce psychological ownership. As for conditions of psychological ownership, factors of person-organization fit, perceived organizational support, and perceived organizational insider positively contribute to psychological ownership. An organization may understand what conditions may influence psychological ownership in accordance with the results. HR practices may be adopted by an organization to select employees with person-organization fit and make employees not only perceive organizational support but also perceive organizational insider in order to enhance psychological ownership of employees.

Limitation and Future Study

This study collected data from high technology industry, the generalizability may be limited; therefore, future studies may collect data from different industries so as to solve the problem. The data utilized in this study was unable to eliminate the biases of common method variance; therefore, future studies can adopt a longitudinal design using different time stages or collect data from different sources so as to solve the problem (Podsakoff et al. 2003). This study only investigates antecedents and consequents of psychological ownership, future studies may further investigate consequences of psychological ownership, such as organizational citizenship behaviors and contextual performance. In

addition, standards that evaluate employees are different from original standards because of dynamic environments. Thus, future studies should investigate the relationship between psychological ownership and adaptive performance in order to enhance the theory of psychological ownership.

References

Arthur, M. B., Inkson, K., & Pringle, J. K. (1999). The new careers: Individual action

and economic change. London: Sage.

Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of

Sociology, 66: 32-42.

Blau, G. (2003). Testing for a four-dimensional structure of occupational commitment.

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76: 469-488.

Culpepper, R. A., Gamble, J. E., & Blubaugh, M. G. (2004). Employee stock ownership plans and three-component commitment. Journal of Occupational and

Organizational Psychology, 77: 155-170.

Cohen, A. (1993). Age and tenure in relation to organizational commitment: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 14(2): 143-159.

Dittmar, H. (1992). The social psychology of material possessions: To have is to be. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82: 812–820.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchinson, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71: 500-507.

Furby, L. (1978). Possession in humans: An exploratory study of its meaning and motivation. Social Behavior and Personality, 6(1): 49-65.

analysis with reading. New York: Macmillan.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1981). LISREL V: Analysis of linear structure

relationship by the method of maximum likelihood. Chicago: National Educational

Resources.

Korsgaard, M. A. & Roberson, L. (1995). Procedural justice in performance evaluation: The role of instrumental and non-instrumental voice in performance appraisal discussions. Journal of Management, 21(4): 657-669.

Kristof-Brown, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurements, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49: 1-49.

Locke, E. A., & Schweiger, D. M. (1979). Participation in Decision-Making: One More Look. Research in Organizational Behavior, 1: 265-339.

Mael. F. A., & Ashforth, B. E. (1995). Loyal from day one: Biodata, organizational identification, and turnover among newcomers. Personnel Psychology, 48: 309-333. Masterson, S. S., & Stamper, C. L. (2003). Perceived organizational membership: An

aggregate framework representing the employee-organization relationship. Journal

of Organizational Behavior, 24: 473-490.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A there-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1): 61-89. Milkovich, G. T. (1987). Compensation systems in high tech companies. In C. S.

technology firms: 103-114. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Pfeffer, J. (1994). Competitive advantage through people. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2001). Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 26(2): 298-310. Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2003). The state of psychological ownership:

Integrating and extending a century of research. Review of General Psychology,

7(1): 84-107.

Pierce, J. L., O’Driscoll, M. P., & Coghlan, A. (2004). Work environments structure and psychological ownership: The mediating effects of control. The Journal of Social

Psychology, 144(5): 507-534.

Pierce, J. L., Rubenfeld, S. A., & Morgan, S. (1991). Employee ownership: A conceptual model of process and effects. Academy of Management Review, 16:121-144.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88: 879-903.

Rousseau, D. M., & Shperling, Z. (2003). Pieces of the action: Ownership and the changing employment relationship. Academy of Management Review, 28(4): 553-570.

Rousseau, D. M., & Shperling, Z. (2004). Ownership and the changing employement relationship: Why stylized notions of labor no longer generally apply─A reply to Zardkoohi and Paetzold. Academy of Management Review, 29(4): 562-569.

property. The Psychologcial Record, 37: 257-268.

Sackett, P. R., & Larson, J. R. (1990). Research strategies and tactics in I/O psychology. In M. D.

Schwab, D. P., 2005. Research Methods for Organizational Studies (2nd ed.), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Smith, K. G., Collins, C. J., & Clark, K. (2005). Existing knowledge, knowledge creation capability, and the rate of new product introduction in high-technology firms.

Academy of Management Journal, 48(2): 346-357.

Stamper, C.L., & Masterson, S. S. (2002). Insider or outsider? How employees perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational

Behavior, 23: 875-894.

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In Steven Worchel and William G. Austin (Eds.). Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2, 7-24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Van Dyne, L., & Pierce, J. L. (2004). Psychological ownership and feelings of possession: Three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25: 439-459.

Vandewalle, D., Van Dyne, L., & Kostova, T. (1995). Psychological ownership: An empirical examination of its consequences. Group & Organization Management,

20(2): 210-226.

VanYperen, N. W., van den Berg, A. E., & Willering, M. C. (1999). Towards a better understanding of the link between participation in decision-making and organizational citizenship behavior: A multi-level analysis. Journal of Occupational

and Organizational Psychology, 72: 377-392.

Wagner, S. H., Parker, C. P., & Christiansen, N. D. (2003). Employees that think and act like owners: Effects of ownership beliefs and behaviors on organizational effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 56(4): 847-871.

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of

Management Review, 14(4): 490-495.

Zardkoohi, A., & Paetzold, R. L. (2004). Ownership and the changing employment relationship: A comment on Rousseau and Shperling. Academy of Management