漢語兒童在同儕互動中言談標記「好」和「對」的使用 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) MANDARIN-SPEAKING CHILDREN'S USE OF DISCOURSE MARKERS HAO ‘OKAY’ AND DUI ‘RIGHT’ IN PEER INTERACTION. BY. 立. 治 Kanyu Yeh 政 大. n. er. io. al. Ch. engchi. January 2013 . sit. y. •. • 國. ㈻㊫學. Nat. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Institute of Linguistics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. i n U. v.

(3) ThelnelmbersUftheCUlIllIlitteeapprUvethethesisUfYeh,Kanw. defendedUnJan28th,2U13.. PrUfessUr. iung-chihI-Iuang. AdvlsUr. PrUfessUrKawaiChui CUmmitteeⅣ Ielllber. CUllmitteeⅣ Ielnber. ApprUved:. KaⅥ niChui.D虹 ectUr,GraduateInsj㏑ teUfLinguisucs.

(4) . 立. 政 治 大. •. • 國. ㈻㊫學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2013 Kanyu Yeh All Rights Reserved iii . i n U. v.

(5) Acknowledgements My warmth and appreciation go to my dearest advisor, Professor Chiung-chih Huang, for her invaluable support. Without her guidance, I would not have been able to achieve what I have. There have been times when it was beyond my imagination to be sitting here typing my acknowledgements. I would like to thank her for her wisdom and encouragement, for allowing me to work on my thesis at my own pace, for all the cheers and smiles and free rides. I would also like to thank her for being the mentor to me not only academically but also in my life in general. She guided me through difficult phases. By providing me with armor and a spear, she has helped me become braver and stronger and to achieve my dreams. I would also like to thank my committee members, Professor Kawai Chui,. 政 治 大. Professor Chia-Ling Hsieh, for giving me their precious advice which has had a. 立. positive impact on the overall quality of my thesis and helped to make it more. • 國. ㈻㊫學. detailed and better organized.. I would like to thank all of the instructors in our graduate institute, Professor. •. One-Soon Her, Professor Yuchau Hsiao, Professor I-Ping Wan, Professor Hsun-huei Chang, and Professor Hui-chen Chan, for sharing their copious amounts of knowledge. Nat. sit. y. and offering courses which have been enlightening. From them I have learnt logical. io. er. thinking and the beauty of language from various perspectives. I would also like to thank 助教惠鈴學姐, for her solid support, for always looking after me and having a. n. al. Ch. willingness to answer any questions I had.. engchi. i n U. v. I would like to thank all my friends and classmates in the Graduate Institute of Linguistics, especially those who I spent a lot of time with in the Language Acquisition Lab, Yi-hsien Lin, Eva Jong, Tristy Chen, Meihsing Kuo and Bruce Huang, for keeping things fun and meaningful. I must say thank you to all my dears, Coocoo, Christine, DJ, Anit, Tzi-rong, and Hsuan Ho, for letting me know there is always someone I can turn to. They always see the good in me and accept my weaknesses and help me to overcome them without hesitation. With them, I always feel safe and at ease. I would also like to thank Miss “just call her name and she’ll be there”, my adorable idol, Chi-Ju Chiu, for the incredibly useful knowledge and skills about technology, databases and software;. iv .

(6) Chou Seph and Jonathan Chang for being the true friends; and Miyuki Ishida for the inspiring and wonderful afternoons. I would like to thank Hsiung Yi, Eunice Chu and Bella Li for bringing me loads of laughter, for keeping things interesting and amusing; and Li-Ya Su for being a laconic but loyal friend. I would also like to thank Yoyo for the chitchats and the great songs, for encouraging and reminding me never forget to look back to see what I have got so far. Yes, all the dots will connect in the end. I would like to thank Mui and Lam2 for their wit and warmth and for always showing up at the right time. Last but not least, I would like to thank Professor Wen-hui Sah for her generous support, for her insight and guidance. I would also like to thank her for looking after. 政 治 大. me ever since I was at college. She has taught me everything. If it weren’t for her, I would not be where I am today.. 立. Above all, I would like to thank my family members for their love and tolerance.. • 國. ㈻㊫學. I have to apologize for not being able to list all the names, who have helped me all the way. I must say thank you to those people who have given me much support in. •. their own unique ways. They are my beloved angels in disguise. Without anyone of them, this journey would not be as wonderful and memorable as it is today.. Nat. sit. y. Thank God. I’m finally here.. al. er. io. But I know deeply in my heart that it is not the end.. n. It is just the beginning.. Ch. engchi. v . i n U. v.

(7) Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ iv Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables ...................................................................................................................................................... viii Chinese Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. ix English Abstract .................................................................................................................................................... x . Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Motivation ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Organization of the thesis .................................................................................................... 3 . 治 政 大 Chapter 2 Literature review ............................................................................................. 5 立 2.1 Discourse markers ................................................................................................................. 5 . •. • 國. ㈻㊫學. 2.2 Discourse coherence .............................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Discourse markers in Mandarin Chinese ....................................................................... 13 2.4 Children’s acquisition of discourse markers ................................................................. 20 2.5 The role of peers in children’s development .................................................................. 26 . Chapter 3 Methods ........................................................................................................... 31 . y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 3.1 Participants and data .......................................................................................................... 31 3.2 Analytical framework ......................................................................................................... 32 3.2.1 The exchange structure ............................................................................................................... 33 3.2.2 The action structure ..................................................................................................................... 34 3.2.3 The ideational structure .............................................................................................................. 35 3.2.4 The information state .................................................................................................................. 37 . Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Chapter 4 Results .............................................................................................................. 39 4.1 Hao and dui in different structures of discourse ........................................................... 39 4.2 Hao in different structures of discourse ......................................................................... 41 4.2.1 Hao as a marker in the information state ............................................................................. 41 4.2.2 Hao as a marker in the exchange structure .......................................................................... 43 4.2.3 Hao as a marker in the action structure ................................................................................ 51 4.2.4 Hao as a marker in both the exchange structure and the action structure ................. 56 4.3 Dui in different structures of discourse .......................................................................... 61 4.3.1 Dui as a marker in the information state .............................................................................. 61 4.3.2 Dui as a marker in the exchange structure ........................................................................... 63 4.3.3 Dui as a marker in the ideational structure .......................................................................... 69 . Chapter 5 Discussion ........................................................................................................ 73 vi .

(8) Chapter 6 Conclusion ....................................................................................................... 81 6.1 Summary ............................................................................................................................... 81 6.2 Limitations and suggestions .............................................................................................. 83 . Appendix A Transcription conventions and gloss abbreviations ........................... 85 Reference ............................................................................................................................. 86 . 立. 政 治 大. •. • 國. ㈻㊫學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat al. Ch. engchi. vii . i n U. v.

(9) List of Tables Table 1. Discourse use of hao (Miracle, 1991, p. 56) ............................................................ 13 Table 2. Subject combination and time duration of each recording section ................... 32 Table 3. Distribution of hao and dui in different structures of discourse ........................ 40 . 立. 政 治 大. •. • 國. ㈻㊫學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat al. Ch. engchi. viii . i n U. v.

(10) 國立政治大學研究所碩士論文提要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:漢語兒童在同儕互動中言談標記「好」和「對」的使用 指導教授:黃瓊之博士 研究生:葉侃彧 論文提要內容: 本研究使用 Schiffrin (1987) 提出的言談結構(discourse structure)為分析 架構,旨在觀察漢語兒童在同儕互動中使用口語中常出現的言談標記「好」和 「對」的情形,藉以檢驗其如何反映漢語兒童的溝通技巧以及同儕互動的特性。. 政 治 大. 研究語料來自六位五歲的漢語兒童兩兩之間互動的對話,共 237 分鐘。. 立. 研究發現五歲漢語兒童能掌握言談標記「好」和「對」在三個言談結構的. • 國. ㈻㊫學. 功能,且他們使用此兩個言談標記的不同功能時有所異同。首先,「好」和 「對」主要使用於交談順序結構(exchange structure)作為表同意的標記。雖然. •. 在成人對話中「好」和「對」皆可用於交談順序結構及語意結構(ideational. sit. y. Nat. structure ) , 作 為 表 知 曉 ( acknowledgement ) 的 反 饋 應 答 標 記 和 話 題 轉 換. er. io. (topic transition)標記,但研究結果發現漢語兒童在交談順序結構中只使用. al. 「好」作為表知曉的反饋應答標記;在語意結構只用「對」作為話題轉換標記。. n. iv n C 研究結果顯示五歲漢語兒童在與同儕互動時,已能夠使用反饋標記「好」表現 hengchi U. 參與對方話題的意願,而他們不使用「對」則可能與「對」作為反饋應答標記 時的用法和應答詞(backchannels)相似有關。根據先前研究指出應答詞屬於兒 童較晚才習得的溝通技巧(Hess & Johnston, 1988)。此外,五歲漢語兒童亦展 現出使用話題轉換標記「對」的能力,顯示他們已知道如何使用言談標記幫助 建構言談連貫性(discourse coherence);而他們選擇使用「對」而非「好」來 轉換話題,則可能與「好」的此項功能所隱含的發話者權威性有關(Chen & Liu, 2009),若使用這類帶有發話者權威的言談標記,則可能損害其與同儕間 的關係。本研究因而推論漢語兒童在同儕互動中言談標記「好」和「對」各種 功能的使用,不僅僅顯示出他們的溝通技巧,同時也反映了同儕互動的特性。 ix .

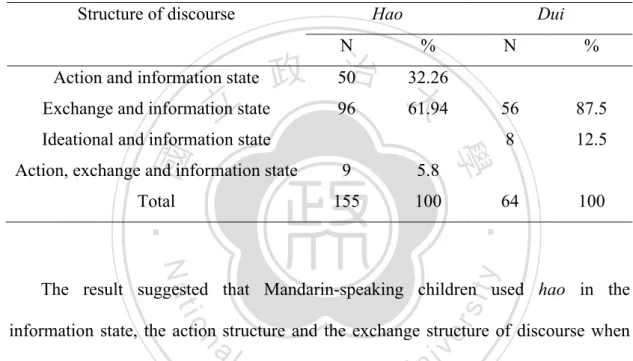

(11) Abstract The thesis aims to investigate Mandarin-speaking children’s use of two frequently appearing discourse markers, hao ‘okay’ and dui ‘right’, when interacting with peers in order to examine how their use of these markers may reflect their communicative skills and the characteristics of peer relation. The data included 237 minutes of 5-year-old Mandarin children’s conversations with friends while playing. Schiffrin’s (1987) model of discourse structures, which includes the exchange structure, the action structure, the ideational structures, the participation frameworks, and the information state, was used for the analysis. The results showed that Mandarin-speaking children used hao in the information state, the exchange structure and the action structure while dui in the. 政 治 大. information state, the exchange structure and the ideational structure. The functions of. 立. hao and dui in the present data demonstrated several similarities and differences. Both. • 國. ㈻㊫學. markers were used by the children in the exchange structure to show the speaker’s agreement. However, only hao functioned as an acknowledgement marker to indicate. •. the receipt of information in the exchange structure while only dui marking topic transitions in the ideational structure, even though both markers can serve these two. Nat. sit. y. functions in adult conversation. Mandarin-speaking children’s use of hao and dui to. io. er. express agreements, which indicates their collaborative stances, may help them establish alliances with each other (Wang et al., 2010). Moreover, Mandarin-speaking. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. children at age five demonstrated their ability to use hao as an acknowledgement. engchi. marker to show their intention to participate in their peer’s current talk. In addition, that only hao but not dui served as an acknowledgement marker may result from the similarity between the acknowledging function of dui and that of backchannels, which has been considered among the last acquired communicative skills (Hess & Johnston, 1988). Furthermore, Mandarin 5-year-old children had the ability to use dui as a topic transition marker to establish discourse coherence. Meanwhile, that dui, instead of hao, was chosen by the children as a transition marker may reflect the relatively equal relations between peers, since hao is usually used by a speaker with higher status to control the topics in adult conversation (Chen & Liu, 2009). It is concluded that Mandarin children’s use of the two markers not only demonstrates their communicative skills but also reflects the particular nature of peer interaction. x .

(12) Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Motivation In the past few decades, discourse markers have been widely investigated by many researchers for their dynamic functions in conversations (Fraser, 1990; Halliday, 1994; Schiffrin, 1987; Wang, Tsai, Goodman, & Lin, 2010). As these research suggested, discourse markers play an important role in conversations. They serve various functions in different discourse levels. There is a widely accepted. 治 政 characteristic of discourse markers that “they impose大 a relationship between some 立 aspect of the discourse segment they are part of… and some aspect of a prior. • 國. ㈻㊫學. discourse segment…” (Fraser, 1999, p. 938). Cross-linguistic studies have also been. •. done on various discourse markers and their functions in terms of discourse coherence. sit. y. Nat. (Andersen, Brizuela, DuPuy, & Gonnerman, 1999; Jisa, 1984, 1987; Kroon, 1998).. al. er. io. These studies revealed that languages around the world seem to have a set of. v. n. discourse markers to connect segments in conversation. Some of these studies focused. Ch. engchi. i n U. on children’s acquisition of various discourse markers. These works suggested that children’s choices and uses of markers reflected their cognition about social relations. Andersen et al. (1999) found the asymmetrical uses of discourse markers when children involved in pretend plays. Children who acted in high status roles used certain discourse markers that rarely appeared in the production of children acting in low status roles. This finding demonstrated that children’s recognition about social relations to one another was reflected in their use of discourse markers. Kyratzis (2005) suggested that children used because at different levels of discourse, especially in participation frameworks, as a marker of collaborative stance in peer interactions. 1 .

(13) 2 . . Her results showed that English children as young as four years old used because in validating justification to support the partner’s or his/her own proposal. Earlier scholars have also put emphasis on the importance of peers in children’s development (Bandura & Walters, 1963; Mead, 1934; Piaget, 1932; Sullivan, 1953). They believed that not only parents play a crucial role in children’s development, significant others, such as siblings, out-of-home caregivers and peers, are all influential to children’s development. These significant others helped children develop their social skills, language ability and social cognition. Because relations. 政 治 大 peer interactions provide a suitable and valuable context for children to have an 立. with peers could be distinguished from those with adults both in forms and functions,. • 國. ㈻㊫學. adaptive development. Through the interaction with peers, children gain the opportunities to experience conflicts, to negotiate and to discuss various perspectives,. •. thereby developing the ability to understand other people’s thoughts, emotions and. sit. y. Nat. intentions (Doise & Mugny, 1984; Piaget, 1932; Selman & Schultz, 1990). Moreover,. n. al. er. io. with the perspective-taking ability, children establish an organized self system. i Un. v. comparative to the others (Mead, 1934). Earlier researchers also claimed that peers. Ch. engchi. function as appropriate social models for children’s personality shaping (Sullivan, 1953) and behavior shaping (Bandura & Walters, 1963). By directly taught or indirectly observing their peers’ social behaviors, children learned about the social world around them and how to behave appropriately in such social context (Bandura & Walters, 1963). While a large and growing body of literature has investigated children’s acquisition of different discourse markers, few studies have focused on how Mandarin-speaking children use the various functions of these markers. According to previous research, hao ‘okay’ and dui ‘right’ were two frequently used discourse .

(14) 3 . . markers now in Mandarin conversations (Tsai, 2001; Wang & Tsai, 2005; Wang et al., 2010; Yu, 2004; Zhang, 2006). This thesis therefore intended to investigate how Mandarin-speaking children manipulate the various functions of the two frequently appearing discourse markers – hao ‘okay’ and dui ‘right’ – especially when interacting with peers, since peers, as suggested in earlier studies, are influential in children’s development. Five-year-old children were chosen in the study as our subjects for they have developed the preliminary ability to use some discourse markers (Huang, 2000). Also, children at this age are usually considered to have fairly more chances than the younger ones to engage in peer interactions. The purpose of. 政 治 大. this thesis is to investigate how Mandarin-speaking children use the discourse markers. 立. hao ‘okay’ and dui ‘right’ in peer interactions in order to examine their. • 國. ㈻㊫學. communicative skills and moreover to see whether it reflects the characteristics of. How do Mandarin-speaking children use the discourse marker hao in. sit. y. Nat. (1). •. peer relation. The research questions are as followings.. al. n. (2). er. io. different discourse structures while interacting with peers?. i Un. v. How do Mandarin-speaking children use the discourse marker dui in. Ch. engchi. different discourse structures while interacting with peers? (3). How do Mandarin-speaking children’s uses of the discourse markers hao and dui reflect the characteristics of peer interaction?. 1.2 Organization of the thesis The reminder of the thesis is laid out as follows. Chapter 2 consists the literature review of previous studies, which include the definition of discourse markers, discourse coherence, and earlier research about the multifunction of hao and dui in. .

(15) 4 . . Mandarin. Cross-linguistic studies about children’s use of discourse markers are included in chapter 2 as well. Chapter 3 describes the methodology and analytical framework of the present study. The results are presented in chapter 4. Finally, discussions and conclusions are made in chapter 5 and 6 respectively.. 立. 政 治 大. •. • 國. ㈻㊫學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat al. Ch. engchi. . i Un. v.

(16) Chapter 2 Literature review Cross-linguistic studies have revealed the dynamic functions of discourse markers in conversations, especially those related to discourse coherence (Fraser, 1990; Halliday, 1994; Schiffrin, 1987; Wang et al., 2010). Some of the studies investigated children’s acquisition of different markers (Andersen et al., 1999; Kyratzis, 2005; Kyratzis & Ervin-Tripp, 1999; Sprott, 1992). In this chapter, related studies of discourse markers are reviewed and presented in the following order. In. 政 治 大. section 2.1 and 2.2, the existing literature on discourse markers and discourse. 立. coherence is reviewed. The studies about discourse markers hao ‘okay’ and dui ‘right’. • 國. ㈻㊫學. in Mandarin Chinese and those concerning children’s acquisition of discourse. •. markers are illustrated in section 2.3 and 2.4 respectively. Finally, in section 2.5, earlier research on the roles of peers in children’s development is discussed.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat 2.1 Discourse markers. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Discourse markers have been widely investigated by many researchers in the past decades. Different but similar definitions have been provided (Fraser, 1990; Lenk, 1998; Schiffrin, 1987). Among them, the most well known definition was the one given by Schiffrin (1987). According to Schiffrin, discourse markers are “linguistic, paralinguistic, or non-verbal elements that signal relations between units of talk by virtue of their syntactic and semantic properties and by virtue of their sequential relations as initial or terminal brackets demarcating discourse units” (p. 40). Discourse markers are used by speakers to make the relations between the previous 5 .

(17) 6 . . and ongoing texts salient in order to build the coherence of discourse units. That is, they have a coherence building function in discourse. Schiffrin suggested that in addition to the semantic content about the real world, discourse markers also mark relations at other levels of discourse. She proposed a framework consisting of five components of discourse organization, which are the ideational structure, the action structure, the exchange structure, the participation framework and the information state. She claimed that discourse markers select and display both the meaning (i.e. contrastive, resultative etc.) and structural relations (i.e. which utterance is a main/subordinate/coordinate unit) between the preceding and. 政 治 大. following utterances. Discourse markers therefore function as the “contextual. 立. coordinates” of an utterance at one or more levels of discourse organization. That is,. • 國. ㈻㊫學. they index an utterance to a certain plane of discourse in which it is produced and is to. •. be interpreted. She argued that it is not the marker itself conveys social and expressive meanings but the discourse slots it situated. For instance, but itself does not have the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. meaning of ‘challenge’, however, in some contexts the utterance following it may be interpreted as a challenge. Schiffrin also identified several common features that. al. n. iv n C qualify an expression to function asha discourse marker. e n g c h i U These features could also be. viewed as the characteristics of discourse markers. The features are listed as following. It has to be syntactically detachable from a sentence. It has to be commonly used in initial position of an utterance It has to have a range of prosodic contours E.g. tonic stress and followed by a pause, phonological reduction It has to be able to operate at both local and global levels of discourse, and on different planes of discourse.. .

(18) 7 . . This means that it either has to have no meaning, a vague meaning, or to be reflexive (of the language, of the speaker). (Schiffrin, 1987, p. 328) In addition to Schiffrin, Fraser (1990) also defined a discourse marker as “a pragmatic marker which provides a commentary on the following utterance; that is, it leads off an utterance and indicates how the speaker intends its basic message to relate to the prior discourse.” In both Schiffrin’s (1987) and Fraser’s (1990) analyses, they discussed mainly about the relations between adjacent units at the local coherence level in discourse. Lenk (1998) further pointed out that discourse markers. 政 治 大. signal relations between larger discourse segments such as topics, situations or. 立. background and foreground knowledge, as well as smaller segments like adjacent. • 國. ㈻㊫學. units. In other words, except the local level, discourse markers can be used to. •. establish coherence at the global level of discourse. Briefly speaking, the function of discourse markers, as previous scholars suggested, is to identify relations between. y. Nat. er. io. sit. segments in the context, both locally and globally, and thereby construct the coherence of the whole discourse (Fraser, 1990; Lenk, 1998; Shiffrin, 1987; Wang,. n. al. Tsai, & Lin, 2007).. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 2.2 Discourse coherence Because discourse markers serve the coherence-building function in discourse, earlier researchers have proposed various frameworks for explaining planes/levels of discourse (Halliday, 1994; Miracle, 1991; Schiffrin, 1987). Schiffrin (1987) established a framework of discourse coherence with five components, which includes the action structure, the exchange structure, the ideational structure, the participation framework and the information state. She suggested that discourse .

(19) 8 . . markers signal meanings at the exchange structure, the action structure and participation framework as well as the ideational structure. The details of the five structures are illustrated below. The action structure refers to a structure where speech acts are situated. Actions are considered as situated because they do not appear randomly. They occur in a constrained linear order. The action structure accounts for the order of actions, that is, what actions tend to precede, what are intended to follow and what actually follows, and also for the speakers’ identities and social setting. It is a structure about “ritual requirements of talk” (Goffman, 1981a), which concerns with “the management of. 政 治 大. oneself and others so as not to violate appropriate standards regarding either one’s. 立. own demeanor or deference for another” (Schiffrin, 1987). English discourse markers. • 國. ㈻㊫學. such as oh, well, and, but, so, and because, all serve their meanings in this structure.. •. In example (1), because functions at the action structure to modify or support a speech act which is a request. According to Schiffrin, causal connectives operate in. y. Nat. er. io. sit. the action structure serves the function as justification of various speech acts. In Redeker’s (1990) analysis, she named action level uses “pragmatic” uses.. al. n. iv n C (1) Mei (4;03): Can I have that h daddo? Because I like e n g c h i U him. (Kyratzis et al., 1990) The exchange structure is where the speaker establishes “conditionally relevant. adjacent-pair parts”. Relevant adjacency pairs, for example, question-answer, requestcompliance and greeting-greeting, are all built in the exchange structure. According to Schiffrin’s definition, this structure is “the outcome of the decision procedures by which speakers alternate sequential roles and define those alternations in relation to each other.” It parallels to that in Goffman’s (1981a) analysis named the “system constraints of talk”, which are the constraints for interlocutors to give appropriate and interpretable feedbacks to each other. In English, discourse markers such as well, and, .

(20) 9 . . but, or, so, and you know all operate in this structure. Example (2) illustrates the use of because in young children’s discourse to introduce turns in the exchange structure. Because in the example carries no meaning of events or speech acts. (2) A: It’s mine [reaching for the toy that B is holding]. B: Because it’s mine [keeping toy out of A’s reach]. (Sprott, 1992) There is also a structure concerning the organization of ideas within the discourse, which is named, in Schiffrin’s term, the ideational structure. In contrast to the action structure and the exchange structure, which are pragmatic, the relations in the. 政 治 大 relations, which are cohesive relations, topic relations and functional relations. The 立 ideational structure are semantic. The ideational structure consists of three types of. • 國. ㈻㊫學. cohesive relations (coherence) of discourse are built when “interpretation of an element in one clause presupposes information from a prior clause because of the. •. semantic relationship underlying a text” (Schiffrin, 1987, p. 26). The organization of. sit. y. Nat. topics and subtopics is also a part of the ideational structure. The other part of the. n. al. er. io. ideational structure includes the functional relations between ideas. That is, the roles. i Un. v. ideas play in relation to the others and within the whole text. English markers and, but,. Ch. engchi. or, so, and because all function in this structure. In example (3), the connective because signals the causal relation between the two events in the real world. It functions as a semantic marker linking the propositional content of two clauses in the ideational structure of discourse. (3) I sprained my ankle ‘cause I was hitting my father’s shoe. (7;05. Kyratzis et al., 1990) The next plane of discourse in Schiffrin’s model is the participation framework. It is a term introduced by Goffman (1981b). The participation framework includes relations between both the speaker and the hearer, and the speaker and his utterances. .

(21) 10 . . Goffman (1981b) suggested that there are various levels of identity a “speaker” and a “hearer” could have through talk. He differentiated the term “speaker” for different “production formats”, such as the speaker who presents talk (an animator) from the one who is presented through talk (a figure), and the one who takes responsibility for the content and implication of talk (a principal). The term “hearer” is also categorized for various “reception formats”, which includes addressees and overhearers (the intended or unintended recipients), passive participants or the expected contributors of talk. The relations between the speaker and the hearer also include institutional relations such as teacher/student and doctor/patient, and interpersonal differences of. 政 治 大. power and solidarity. Another aspect of the participation framework is how a speaker. 立. could relate to the utterances (the proposition, actions and turns) he produced. For. • 國. ㈻㊫學. example, speakers may evaluate, commit to or distance from their ideas; they may. •. perform their actions indirectly or directly; or they may claim or relinquish their turns. The way a speaker relates to his/her utterances influences the relation between the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. speaker and hearer. Discourse markers in the participation frameworks “serve to shift the roles in the talk of participants, or introduce upcoming talk as relating to concerns. al. n. iv n C or questions raised in prior talk” (Schiffrin, This shift of roles can be seen as h e n g1987). chi U suggesting a new episode or phase in an exchange or activity. For instance, the. marker well is often used to signal upcoming talk as contradicting expectations rose in prior utterances or questions. The last component of discourse in Schiffrin’s model is the information state. The information state refers to interactions between speakers and hearers in their cognitive states. Namely, it focuses on the organization and management of both the speaker and hearer’s knowledge and meta-knowledge. In other words, both the speaker and hearer need to understand what they know and what other interlocutors know .

(22) 11 . . respectively, and what information they share in order to give sufficient information for their hearers to interpret their messages. The interactions in the information state are interactive and dynamic processes that would change frequently throughout the conversation. Similar to Schiffrin, Halliday (1994) proposed another model for explaining discourse coherence. He also assumed that language is multifunctional and metafunctional. In his model, he divided discourse into three levels: the ideational level, the textual level and the interactional level. The ideational level is where. 政 治 大 where links between situations are made and where the cohesive texts are constructed. 立. “language serves to express logical and experiential meanings”. The textual level is. • 國. ㈻㊫學. The interactional level is where the interlocutors use languages as a set of actions on each other to build up relations between themselves and their addresses. It is where. •. speaking,. previous. researchers. suggested. that. sit. Nat. Generally. y. social relationships are established and maintained.. language. is. n. al. er. io. multifunctional. A linguistic unit, such as a discourse marker, may operate in more. Ch. i Un. v. than one discourse structures at the same time. Theoretically it is possible for each. engchi. discourse marker to function in all structures. However, in real world situations, the structures where a certain discourse marker could situate are restricted. It is due to the limited discourse slots one marker could locate. For one marker, some functions in certain discourse structures are more easily found than the others. For instance, in English, well, okay and now only function in the action structure, the exchange structure and the participation frameworks, but are seldom found in the ideational structure. Because serves as a marker in the action structure, the exchange structure and the ideational structure, but is hardly found in the participation frameworks (Kyratzis & Ervin-Tripp, 1999). .

(23) 12 . . Moreover, previous studies suggested that discourse markers could be used to build up both the local and global relations (Lenk, 1998; Schiffrin, 1987). Local relations consist of those between adjacency pairs. According to Sacks and colleagues (1974), the organization of conversations is generally based on “adjacency pairs”. Adjacency pairs are “consecutive, contingently related utterances produced by two different speakers” (Wang et al., 2007, p. 683). They can be both reciprocal like greeting-greeting, and non-reciprocal such as question-answer. An adjacency pair consists of two parts. The “first pair part” projects an adjacency pair can carry out various types of the “second pair part”. For example, a statement as the first part in an. 政 治 大. adjacency pair may be followed by another statement, an agreement, a refusal, a. 立. counter-statement, or nothing at all. Among the wide range of possible second pair. • 國. ㈻㊫學. parts, there are certain ones that are preferred by speakers than the others. These. •. preferred second pair parts demonstrate the alignment between interlocutors. They are spoken out without any signals of hesitation and are usually made up of simple. y. Nat. er. io. sit. sentence structures. On the other hand, dispreferred second pair parts usually follow a pause or other hesitation markers, such as um. In addition, for being polite, they are. al. n. iv n C usually initiated by signals of agreement an apology or appreciation h e norg acceptance, chi U. and are usually with explanations (Levison, 1983; Pomerantz, 1975). Well, for instance, is one of the most common used discourse markers in adult conversations as the marker of dispreferred responses in adjacency pairs (Pomerantz, 1984). The relations of adjacency pairs construct the local structure of discourse. Moreover, discourse markers can also mark global relations. Global relations are the relations between larger chunks of discourse, topics and phases. Schiffrin (1987) and Polanyi and Scha (1983) have proposed that so in English could function at the global level of discourse to signal returns of digressed topics. It is, in their term, a “pop-marker”. In. .

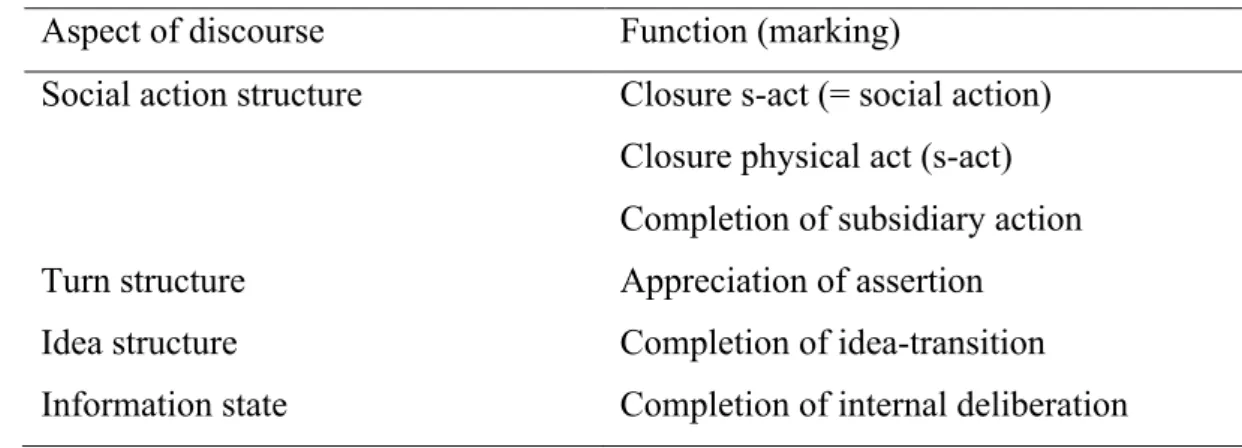

(24) 13 . . other words, a global-level discourse marker is a boundary marker indicates changes of topics or episodes. In brief, according to earlier researchers, discourse markers are multifuntional. They may serve more than one functions at different discourse structures at the same time.. 2.3 Discourse markers in Mandarin Chinese In terms of discourse markers in Mandarin, some studies have focused on the use of hao ‘okay’ and dui ‘right’ in conversations. Lu (1980/2004) suggested that hao in. 政 治 大. Mandarin serves to express different moods. It is a marker of agreement, conclusion. 立. and counter-expression that resembles an interjection. His analysis captured the. • 國. ㈻㊫學. essential meaning of hao, however, it did not explain clearly the multifunction of hao. •. in discourse. Miracle (1991) was the first researcher who analyzed the various. sit. y. Nat. functions of hao in spoken discourse based on four discourse levels. He observed that. io. er. hao marks three types of relations: (1) the development and closure of social and physical actions, (2) the speaker’s assertion of previous utterance and (3) the. al. n. iv n C transition to a new topic or social activity. h e nTable i U Miracle’s analysis of hao in g c h1 shows different discourse levels. Table 1. Discourse use of hao (Miracle, 1991, p. 56) Aspect of discourse. Function (marking). Social action structure. Closure s-act (= social action) Closure physical act (s-act) Completion of subsidiary action. Turn structure. Appreciation of assertion. Idea structure. Completion of idea-transition. Information state. Completion of internal deliberation. .

(25) 14 . . In the social action structure, hao is related to the development and closure of commissive or requestive actions. Hao also marks assertions in the turn structure. In the idea structure, it functions as a marker of idea management indicating transitions to a new topic or a social activity. According to Miracle, the core function of discourse marker hao in Mandarin is to mark closures and transitions. Some researchers have analyzed the various functions of hao in terms of its grammaticalization process (Biq, 2004; Bybee, 1994; Haiman, 1994; Wang, 2004; Wang, 2005). Biq (2004) investigated the use of hao in certain constructions. 政 治 大 categorized from a lexical item (a stative verb) to a marker of mood and subjectivity. 立. conveying stances. She pointed out that hao in such constructions has been de-. • 國. ㈻㊫學. Wang (2004) analyzed the various functions of hao and its directionality of different changes from both synchronic and diachronic perspectives. She claimed that hao has from. a. predicative. adjective. to. both. •. changed. a. discourse. marker. of. sit. y. Nat. agreement/acceptance and a marker of transition/closure. Bybee (1994) and Haiman. n. al. er. io. (1994) have also come to the same conclusion of the grammaticalization process of. i Un. v. hao. They further pointed out that the semantic change of hao from a predicative. Ch. engchi. adjective to a discourse marker of agreement and a marker of closure went through the conventionalization of implicature and ritualization. Wang (2005) investigated the multifunction of hao in relation to its grammaticalization process. She argued that the grammaticalization process of hao went through three different paths. It developed from (1) a predicative adjective to a resultative complement then to a phase marker, (2) a predicative adjective to an intensifier, and (3) a predicate to a discourse marker. She pointed out that these meanings of hao are closely related to each other because they all derived from the primary predicative meaning. Hao in Mandarin originally meant ‘good’. During the grammaticalization process, it obtained the meaning of ‘very’, .

(26) 15 . . ‘satisfaction’, and ‘finishing doing something’, that is, hao lost some of its lexical meaning and became more grammatical. Differing from the studies considering the grammaticalization process, Shao and Zhu (2005) analyzed the discourse functions of hao in Mandarin. They found out that hao serves three types of discourse functions, which are (1) the active answering function (appraisal, promise, and affirmation), (2) the passive answering function (acceptance of indirect refusal, concession, and irony), and (3) the discourse coherence function (discourse boundary marking, transition, and closure). They also. 政 治 大 an independent unit (i.e. without combing with other discourse elements). Hao a 立 discussed the functions of hao when it appears with particles such as a, ba and le as. • 國. ㈻㊫學. signaled the speaker’s appraisal toward the previous utterance. Hao ba marked reluctant agreements and hao le indicated concessions or the pre-closure of a topic.. •. Similarly, Xu (2005) analyzed the discourse functions of hao in teenagers’ telephone. sit. y. Nat. conversations and face-to-face interactions in terms of gender differences. He. n. al. er. io. suggested that hao presents four discourse relations: (1) the beginning of a turn, (2). i Un. v. the pre-closures, (3) the speaker’s acceptance, and (4) asking for opinions when hao. Ch. engchi. co-occurs with sentence-final particles, such as ba, and ma. His results showed that the teenagers used hao more frequently in telephone conversations than face-to-face interactions. This may result from the lack of visual and gestural information in telephone conversations. Other devices, for instance, hao, were therefore needed to help make the conversations coherent. Besides, girls tended to use hao to express acceptance and ask for opinions while boys preferred using it to mark the beginning of a turn or the pre-closure of a topic. Wang and Tsai (2005) further investigated the meanings of hao in spoken Mandarin discourse. They adopted Halliday’s (1994) three-dimension model with the .

(27) 16 . . ideational level, the textual level and the interactional levels. They analyzed the use of hao in both daily conversations and radio interviews. At the ideational level, hao can be an adjective meaning ‘good, fine, nice, okay, all right, yes’ or a degree adverb similar to ‘very’ in English. At the interactional level, hao functions as an agreement/acceptance marker. It signals the speakers’ positive evaluation of the previous interactional move. Depending on the nature of the previous move, hao can mark an agreement, compliance, acceptance, or concession. Sometimes it could be used to acknowledge that it is the speaker’s obligation to take the present turn in order to release the other interlocutor from the responsibility to continue his/her turn.. 政 治 大. Besides, the appearance of hao in discourse also indicates the speaker’s intention to. 立. end the present exchange and to start a new one. Wang and Tsai (2005) further. • 國. ㈻㊫學. analyzed speakers’ uses of hao at the textual level. They found that there were. •. contextual differences of the various meanings of hao. In radio interviews, hao was used more frequently by the host to signal the end of a talk as a (pre-. y. Nat. er. io. sit. )closure/transition marker. In daily conversations, it was used more constantly as a marker to convey the speaker’s agreement and a concession marker to negotiate the. al. n. iv n C closure of the current topic. Lu (2006) that hao has its pragmatic functions h esuggested ngchi U. such as evaluation, transition, marking closure of speech acts or conversations, and showing agreement or acceptance. According to Xian (2007), hao serves the functions of topic transition, social deixis and speech acts of directive declarations. Generally speaking, similar to other discourse markers, the various functions of hao are used to build up relations between utterances, in other words, to establish discourse coherence. The use of hao has no reference to the described situation in the real world but only has something to do with the speaker’s own beliefs about discourse coherence, especially correlations between situations.. .

(28) 17 . . In addition to the studies of hao in Mandarin conversations, research about dui ‘right’ and its discourse functions has also been conducted (Chui, 2002; Tsai, 2001; Wang et al., 2010; Yu, 2004). Chui (2002) investigated the ritualization process of dui developing from a verb to a discourse particle in spoken Mandarin. Originally dui is a verb conveys the speaker’s positive belief toward the truthfulness of the previous proposition. According to Chui, in conversations, the speaker can use question tags such as dui-bu-dui ‘true-not-true’ to confirm the truthfulness of the information from his addressee. The addressee’s habituated answer is dui. On the other hand, the addressee would also ask zhende-ma ‘Really?’ or shi-ma ‘Is that so?’ to seek for truth. 政 治 大. confirmation from the speaker. And the habituated answer of the speaker is also dui.. 立. Such adjacency pairs of question-answer form the conversational routines in that dui. • 國. ㈻㊫學. was ritualized and used frequently by both the speaker and the addressee to commit. •. the truth of his own or others’ utterances even though the other interlocutors did not ask for it. Because of these two paths to conventionalized routines, dui has gained its. y. Nat. er. io. sit. pragmatic functions to indicate agreement or strengthen the truthfulness of the proposition conveyed. Tsai (2001) and Yu (2004) both focused on the discourse. al. n. iv n C functions of dui in Mandarin spokenhdiscourse. They suggested that dui serves various engchi U functions in conversations. In addition to the affirmative meaning, dui also has pragmatic meanings, such as showing agreement, acknowledgement and confirmation or as a device of textual organization. Dui also serves the functions of reaction tokens. or backchannels to express speaker’s attention and interests on the current talk. According to Clancy and colleagues’ (1996) categorization of reactive tokens, reactive expressions are the “short no-floor-taking words or phrases” a non-primary speaker uttered during the interaction. The typical reactive expressions are assessments, such as zheyang hao ‘such PRT’ and dui ‘right’ in Mandarin. Tsai and. .

(29) 18 . . Yu argued that because of the context-sensitive nature of dui, its real meaning could be better understood by considering the sequential and social contexts it involved in. Wang and colleagues (2010) further analyzed the functions of hao and dui in Taiwan Mandarin conversations and compared the similarities and differences between the two discourse markers. They proposed that both hao and dui function in the textual and the exchange structures of discourse. Dui functions as a continuity marker and an agreement marker in the two structures respectively. Dui could be used in the speaker’s own turn to affirm and strengthen the truthfulness of his subjective. 政 治 大 exchange structure, dui is used by the addressee to show agreements and meanwhile 立. beliefs and imply continuity in the textual structure. On the other hand, in the. • 國. ㈻㊫學. acknowledge what the speaker has said was true. This function is similar to that of right in English (Watts, 1989). Dui signals not only the perception and understanding. •. of shared information but also the shared orientation towards it. Sometimes, when dui. sit. y. Nat. forms a single turn, other than expressing agreement, it also acknowledges the. n. al. er. io. speaker’s right to continue his current turn. In this case, dui serves very similar. i Un. v. function as other short verbal responses such as backchannels.. Ch. engchi. Dui could also. combine with other discourse particles. Combining with particle le, dui le functions as a marker of information management that enables the speaker to interrupt the current topic and starts a new and unrelated one. In other words, dui le as a transition marker sets up an expectation that a new topic is to begin. In the study, Wang and colleagues’ suggested that hao as well as dui functions both in the textual structure and the exchange structure. In the textual structure hao functions as a boundary marker while in the exchange structure it marks agreement or acceptance. When hao combines with different particles, it conveys a wider range of interactional functions. For example, hao la, hao ba, hao ma all indicate concessions, especially the reluctant ones (Biq, .

(30) 19 . . 2004). Hao with particles a or ya expresses the speaker’s personal concern. The particles a and ya do not add extra information to the original propositional content but help contextualize the utterances and meanwhile manage the information flow and shared knowledge. Particle le also co-occurs with hao, it marks the “change of state” (Chu, 1999) and the “currently relevant state” (Li &Thompson, 1981). Hao le therefore identifies a reference time of a situation and indicates the relationship of the current state to that situation. When hao combines with particle la, it implies the speaker’s intention to close the current topic and conversational turn.. 政 治 大 that in Mandarin conversations dui not only signals agreement but also displays weak 立 Besides all the functions mentioned above, Wang and colleagues also suggested. • 國. ㈻㊫學. disagreement. Most of the time disagreement is a face-threatening act. For being polite, speakers tend to express their disagreement in a less direct way such as. •. minimizing the extent of their disagreement. They may, for example, express these. sit. y. Nat. dispreferred second pair parts with softeners or with partial agreement, using “yes,. n. al. er. io. but…” strategy (Pearson, 1986) to make their disagreement less threatening.. i Un. v. Pomerantz (1984) categorized the combination of partial agreement and partial. Ch. engchi. disagreement as weak disagreement in contrast to strong agreement, which is expressed in an immediate and direct way. According to Wang et al. (2010), in Mandarin, weak disagreements or partial agreements usually start with an agreement token such as dui or hao. The agreement tokens hao and dui function as facepreserving devices to show the speaker’s shared understanding (Holmes, 1986) or positive politeness in Brown and Levinson’s (1987) term. To sum up, Wang et al. (2010) claimed that hao and dui in spoken Mandarin are both used by the speaker to negotiate with the hearer for consensus about the propositional contents and relevance of utterances in the textual structure and the interactional structure to establish .

(31) 20 . . alignment and coherence of discourse. Hao serves as a positive response to requests, suggestions, plans and proposals to agree with previous speaker’s act or move. Dui, on the other hand, confirms the truthfulness of the previous speaker’s assessment or information and as a result indicates the speakers’ agreement. Furthermore, dui indicates not only shared knowledge between interlocutors but also shared orientation toward that information. It thus can sometimes co-occur with contrastive markers such as danshi/keshi/buguo ‘but’ to express weak disagreement. Moreover, hao and dui can both combine with discourse particles to express a wider range of interactional functions. For example, as a topic transition marker in the ideational. 政 治 大. structure, hao with particle le indicates the speaker’s intention to close the current. 立. topic while dui le sets up an expectation that a new but unrelated topic is to begin.. • 國. ㈻㊫學. Both dui and hao are used by Mandarin speakers to show their involvement in the. et al., 2010).. •. conversation, and therefore build up the alignment and coherence of discourse (Wang. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. Although earlier studies have discussed the various functions of hao and dui in. i Un. v. Mandarin conversations, little has been done in the contexts of child discourse. Since. Ch. engchi. hao and dui are two frequently used discourse markers in adult conversations, it would be beneficial to investigate Mandarin children’s use of these markers in order to understand the functions of the markers more thoroughly.. 2.4 Children’s acquisition of discourse markers Children’s acquisition of discourse markers has come into focus of many studies in the fields of cognitive science and sociolinguistics. Earlier research suggested that children’s uses of discourse markers reflect their ability to differentiate levels of .

(32) 21 . . discourse. These studies have revealed children’s understanding of discourse levels and their abilities to represent local and global relations. Moreover, they have shown that there were developmental and contextual differences in children’s uses of discourse markers (Andersen et al., 1999; Huang, 2000; Kyratzis & Ervin-Tripp, 1999; Sprott, 1992). Earlier findings have shown that there is a developmental shift from the action to the more ideational uses of discourse markers in children’s production (Kyratzis et al., 1990; Kyratzis & Ervin-Tripp, 1999). Researchers believed that the persuasive uses of languages were more frequently used in the young children’s practical lives because they are more useful for the children to achieve their. 政 治 大. conversational goals. According to Bamberg (1987) and Berman and Slobin (1994),. 立. the ability to take perspectives and orientations of their addressees emerged relatively. • 國. ㈻㊫學. late in children’s narratives. Researchers therefore expected that the function of. •. boundary marking of discourse markers would also appear later in children’s development (Kyratzis & Ervin-Tripp, 1999). Earlier investigation has proved that the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. uses at the action level indeed appeared earlier than those at the ideational or descriptive level in child discourse.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Some cross-linguistic research has also been done on children’s acquisition of the textual uses of discourse markers in English, French and Hebrew (Andersen et al., 1999; Berman, 1996; Jisa, 1984; Kyratzis & Ervin-Tripp, 1999; Sprott, 1992). Sprott (1992) investigated English-speaking children’s use of discourse markers in verbal disputes. He included children from 2;7 to 9;6 in his study and investigated their uses of five discourse markers, because, so, and, but, and well, in terms of their textual functions. He analyzed these markers according to a cline of the interactional to ideational functions, in other words, from the exchange functions, the action functions, the local ideational functions to the global ideational functions. The result showed that .

(33) 22 . . children used these discourse markers differently as they grew up. Young children’s uses of discourse markers were first limited on local levels that index the action structure or the exchange structure. Functions of the ideational structure appeared later in children’s development and the ideational uses at the global level were the latest developed. Children organized discourse coherence mainly at the local level when they were 3;6 to 4;0. After that, they started to construct the global level relations all the way to adulthood. As children started to mark relations at the global level, because and but were the first ones children used in verbal disputes since they present reasons and contradictions which are the important parts of disputes. Sprott. 政 治 大. claimed that as children grow up, the markers are used either to express more. 立. functions or they may lose the primary functions and fulfill other functions.. • 國. ㈻㊫學. Kyratzis and Ervin-Tripp (1999) investigated English-speaking children’s. •. acquisition of discourse markers when they interacted with peers. They collected data. sit. y. Nat. from both 4- and 7-year-old best-friend dyads involving in a doll play situation and. n. al. er. io. story re-telling. Schiffrin’s (1987) model was adopted in their study, which includes. i Un. v. the exchange structure, the action structure, the ideational structure, and the. Ch. engchi. participation frameworks. Discourse markers because, but, so, well, ok and now were identified and coded in terms of their functions. The results showed that there were age differences and contextual differences in children’s use of discourse markers. Children’s use of three makers, okay, now and so changed from the local to the global level. The meanings of but and because in child conversation underwent a shift from the action structure to the ideational structure. Furthermore, Kyratzis and ErvinTripp’s results suggested that younger children, especially boys, marked the discourse relations in the action structure while older children tended to mark them in the ideational structure and the participation frameworks. Moreover, older children .

(34) 23 . . tended to mark more global relations rather than only local ones. In other words, young children predominately used discourse markers in the action structure and the exchange structure. They seldom marked relations in the ideational structure and the global level. The contextual differences were found in children’s choices of the types of markers and the discourse structures they operated in. Different contexts prompted different discourse markers. In the doll-play section, English children used more action level and participation markers when negotiating with their partners. All the four types of discourse uses, including the action level, the ideation level, boundary markers and participation frameworks, operated in emplotment/enactment in doll play.. 政 治 大. On the other hand, story re-telling consisted more of the uses at the ideational level,. 立. participation frameworks and global boundary markers. Kyratzis and Ervin-Tripp. • 國. ㈻㊫學. proposed that negotiation yielded predominately action-level uses of discourse. •. markers may result from the facts that the proposal of one speaker has been challenged and therefore the speaker needs to give reasons for the challenge. Based. y. Nat. er. io. sit. on the finding that younger children only had the narrative-like uses of discourse markers in emplotment rather than in story re-telling, Kyratzis and Ervin-Tripp. al. n. iv n C argued that emplotment may be a scaffold children to acquire these narrative-like h e n for gchi U uses of markers. They further suggested that communicative functions of discourse markers emerged earlier than pure representative ones. Communicative functions of these markers, such as the action-level uses and the ideational uses in emplotment, were better understood by young children. Previous research has also demonstrated that children learned textual functions of discourse markers earlier than their registered functions. According to Kyratzis and Ervin-Tripp (1993), English-speaking children acquired the textual uses of discourse markers well before age five or six, which is the time they first began to use the .

(35) 24 . . sociolinguistic functions of these discourse markers. The studies of the acquisition of French discourse markers showed similar results. Jisa (1984, 1987) also found that young French-speaking children at first used the connective et puis ‘and then’ for all purposes. As they grow up, they then limited their use of et puis when they acquired other connectors, such as alors ‘then’. Andersen and colleagues (1999) have conducted a cross-linguistic study about early acquisition of discourse markers and how these markers function as markers of social relation. They compared earlier findings of 4 to 7 years old American English,. 政 治 大 puppet role-play section in terms of the acquisition process of discourse markers as 立. Lyonnais French (Andersen, 1990, 1996) and Chicago Spanish-speaking children in a. • 國. ㈻㊫學. registered variables. They analyzed the children’s usage of discourse markers signaling the relations between the interlocutors on the participation frameworks. •. based on Schiffrin’s (1987) model. The results revealed developmental differences in. sit. y. Nat. all the three groups. The frequency of discourse markers children used increased with. n. al. er. io. age. Their results also indicated that there were cross-linguistic similarities when. i Un. v. children used discourse markers to convey social meanings and to manipulate social. Ch. engchi. power relations before such relations have established. Linguistic parallels were found between the three groups in terms of the frequency of discourse markers in different roles, the distribution of both lexical and non-lexical markers and the use of stacking. Children at age six or seven in all groups used “place holders” or “boundary markers” such as well, okay, now, um, oh and uh more frequently in high status roles. Moreover, they chose more lexical markers when playing high status roles while non-lexical boundary markers in low status ones. Furthermore, when children acted as the high status roles, they tend to combine some discourse markers together, or so-called “stacking”. For English-speaking children at age six, they acquired a fair number of .

(36) 25 . . discourse markers and understood how to use them to convey status asymmetry depends on various roles and situations. In other words, they chose certain discourse markers when playing specific roles. They knew how to manipulate social relations by using discourse markers before these relations were established. The use of different discourse markers when playing various roles reflected the children’s understanding and abilities to establish social relations. Kyratzis (2005) investigated how English children used because as a marker of collaborative stance in peer interaction. Her findings showed that children used. 政 治 大 used because in three situations: (1) to continue a participant’s idea cross turns, (2) to 立. because in the participation frameworks to mark solidarity or collaboration. They. • 國. ㈻㊫學. justify the speaker’s agreement with the other’s proposal, (3) to justify the speaker’s elaboration of the other’s proposal in his/her own turn. The results also demonstrated. •. gender differences in children’s usage of because. When justifying their moves, girls. sit. y. Nat. tended to validate their thoughts while boys preferred oppositional justifications.. n. al. er. io. Besides, girls used more marking on justification with because. In both girls and boys. i Un. v. data, validating justifications received more because marking than the other two types.. Ch. engchi. Huang (2000) conducted a developmental study about Mandarin children’s acquisition of discourse marker hao. He divided sixty 3-5 year old Mandarin-speaking children into three age groups and investigated their casual conversations with both adults and peers. His results suggested that there is a developmental process of Mandarin-speaking children’s use of hao as a discourse marker. Older children had the ability to use more functions of hao. The three-year-old children used hao mostly in the action and the exchange structures of discourse. They used hao to mark closures of physical actions and complaints of other people. Besides, they also used hao to acknowledge assertions in request-compliance pairs. Mandarin-speaking .

(37) 26 . . children started to use hao in the ideational structure at around age four. Hao in 4 year olds’ production can mark the termination of a hesitation pause. This function acknowledged the children’s ability to organize and manage their information states (cognitive states). Both 4- and 5-year-old children had the ability to manipulate hao as a turning-grabbing marker. They used hao in the exchange structure to grab the turns from other interlocutors. The evidence came from the increased frequency of overlapping in their conversations. Moreover, Mandarin speaking children at age four and five used hao to initiate elaboration questions in the information state. Furthermore, the 5 year olds had shown the ability to manipulate two more functions. 政 治 大. of hao in the ideational structure, which were topic shifting and linking of two phases.. 立. Generally speaking, Mandarin-speaking 3 and 4 year olds used hao mostly at the local. • 國. ㈻㊫學. level (i.e. the action structure and the exchange structure) while 5 year olds have. •. shown the ability to use hao at the global level (i.e. the ideational structure).. sit. y. Nat. Cross-linguistic studies have been carried out on children’s acquisition of. n. al. er. io. discourse markers (Andersen et al., 1999; Berman, 1996; Jisa, 1984, 1987; Kyratzis &. i Un. v. Ervin-Tripp, 1999; Sprott, 1992). However, relatively less research has focused on. Ch. engchi. Mandarin-speaking children’s use of discourse markers, not to mention those concerning the various functions of Mandarin discourse markers. The thesis therefore aims to investigate Mandarin-speaking children’s use of the multifunction of discourse markers in order to examine their communicative skills.. 2.5 The role of peers in children’s development Children’s development has been of interest to many researchers in various areas such as psychology, linguistics, and education. Previous studies have revealed several .

(38) 27 . . factors that may influence children’s development. Earlier scholars have suggested that not only parent-child relationships play an important role in children’s development, interactions with significant others, such as siblings, out-of-home caregivers and peers, all have a potential influence on children’s development (Bandura & Walters, 1963; Mead, 1934; Piaget, 1932; Sullivan, 1953). These significant others help children develop their social skills, language abilities and cognition. Moreover, peer relations represent suitable and valuable contexts for children to have an adaptive development. Children without experiencing normal peer interactions may easily go through maladaptive development (Rubin, Coplan, Nelson, & Lagace-Seguin, 1999).. 立. 政 治 大. • 國. ㈻㊫學. Piaget (1932) was the most well known scholar who emphasized the importance of peer interactions in children’s development. He suggested that children’s relations. •. with peers could be distinguished from those with adults, either in forms or functions.. sit. y. Nat. Children’s relationships with parents or other adults are asymmetrical and. n. al. er. io. complementary. They fall along a vertical plane of power assertion and dominance.. i Un. v. Children normally accept adults’ rules for obedience instead of completely. Ch. engchi. understanding such rules. On the contrary, peer relations are more symmetrical and balanced. Unlike adult-child relations, peer relations fall along a more horizontal plane of dominance and power assertion. It is, Piaget claimed, the experiences of interacting with peers provide children the opportunities to examine conflicting ideas and to develop the ability to negotiate and discuss various perspectives. Not until children understand how to negotiate with others could they decide whether to compromise with or reject others’ suggestions. It is believed that one of the best and effective ways for children to solve conflicts with peers is through the cooperative exchange of questions, explanations and reasoned conversations (Rogoff, 1990). .

(39) 28 . . Therefore, these interactions with peers may bring out good outcomes of the positive and adaptive development for children in many aspects, such as the abilities to understand others’ thoughts, emotions and intentions (Doise & Mugny, 1984; Selman & Schultz, 1990). With the social understanding of other people’s minds, children were believed to be able to consider the consequences of their own or others’ social behaviors both for themselves and for other people. This ability then results in their production of socially appropriate behaviors (Dodge & Feldman, 1990). Similar to Piaget, Mead (1934), Sullivan (1953), Bandura and Walters (1963). 政 治 大 children’s ability of perspective taking 立. also pointed out the importance of peers in children’s development. Mead (1934) suggested that. developed from their. • 國. ㈻㊫學. interactions with peers. Through the participation in rule-governed activities with peers, children learned to recognize and coordinate various perspectives of others.. •. They then conceptualized the idea of “generalized others”, and established the. sit. y. Nat. systemized sense of “self”, which is comparative to “the others”. In Mead’s theory,. n. al. er. io. peer interactions were essential for children’s development of both perspective-taking abilities and the organized self system.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Sullivan (1953) believed that children’s interactions with peers helped them develop “the concept of mutual respect, equality and reciprocity”. Moreover, he emphasized the significance of “special relationships”, such as friendship, for developing these concepts. When these concepts of mutuality became central to children’s close friendships, they started to acquire a more complex understanding of social relationships. Sullivan suggested that as children grew up, peers became more and more important in children’s personality shaping. Peers have significant influence on children’s awareness of the construction of social roles such as dominance and. .

(40) 29 . . deference, competition and also cooperation. The understanding of friendships turned out to have noteworthy impacts on other relationships. Bandura and Walters (1963) proposed another theory known as the social learning theory, which has been influential to many current studies on peer interaction. In the social learning theory, children learn about the social world around them and how to behave appropriately in such social contexts through directly taught by peers or indirectly observing others’ social behaviors and consequences. In other words, children’s interaction with peers provides a suitable environment for them to acquire. 政 治 大 behavior shaping and controlling agents to each other. These social behaviors would 立. knowledge about the social world and appropriate social behaviors. Peers become. • 國. ㈻㊫學. in return help children to maintain, establish or disrupt their relations with peers. Briefly speaking, peers are influential in children’s cognitive development, as. •. well as their personality and social behavior shaping. They not only help each other. y. Nat. er. io. for each other.. sit. understand others’ emotions, intentions and thoughts but also behave as social models. al. n. iv n C Previous researchers have discussed h e nhow h i U markers build up discourse g cdiscourse coherence, what functions they serve in discourse and how children acquire these markers. These studies revealed that discourse markers are multifunctional. They may operate at more than one discourse structures at the same time and serve various functions. Developmental and contextual differences were also found in children’s acquisition of these markers. In addition, earlier research illustrated that peers play a significant role in children’s cognitive development and in shaping each other’s behavior as social models. These studies have shed light on the importance of peers in children’s development. However, few studies focused on Mandarin-speaking. .

數據

Outline

相關文件

As students have to sketch and compare graphs of various types of functions including trigonometric functions in Learning Objective 9.1 of the Compulsory Part, it is natural to

(a) In your group, discuss what impact the social issues in Learning Activity 1 (and any other socials issues you can think of) have on the world, Hong Kong and you.. Choose the

In this paper, we have shown that how to construct complementarity functions for the circular cone complementarity problem, and have proposed four classes of merit func- tions for

This thesis mainly focuses on how Master Shandao’s ideology develops in Japan from the perspective of the Three Minds (the utterly sincere mind, the profound mind, and the

If necessary, you might like to guide students to read over the notes and discuss the roles and language required of a chairperson or secretary to prepare them for the activity9.

此種情況在弱智兒童猶為顯著,大部份弱智兒童的

Therefore, how to promote and the maintenance service quality can continue forever topic of the management, becomes the research once more focal point.So, how to try to

The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the geometric design of curvic couplings and their formate grinding wheel selection, and discuss the geometric