This article was downloaded by: [National Chiao Tung University 國立交通大學] On: 26 April 2014, At: 06:11

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wbbm20

Organizational Justice in the Sales Force: A Literature

Review with Propositions

Chia-Chi Chang a & Alan J. Dubinsky b

a

Department of Management Science , National Chiao-Tung University , 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, Hsinchu, Taiwan 300, ROC

b

School of Consumer and Family Sciences, Purdue University , West Lafayette, IN Published online: 17 Oct 2008.

To cite this article: Chia-Chi Chang & Alan J. Dubinsky (2005) Organizational Justice in the Sales Force: A Literature Review with Propositions, Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 12:1, 35-71, DOI: 10.1300/J033v12n01_03

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J033v12n01_03

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http:// www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Organizational Justice in the Sales Force:

A Literature Review with Propositions

Chia-Chi Chang Alan J. Dubinsky

ABSTRACT. Many factors have been identified as having an impact on salespeople’s work outcomes. Although a plethora of empirical research has determined that organizational justice influences employees’ job-re-lated responses, minimal attention has been given to the effects of organi-zational justice in a selling context. The nature of the sales position, as well as the fact that organizational justice is managerially controllable, suggests that this variable warrants research attention. The purpose of this paper is to elucidate the concept of organizational justice and develop propositions regarding linkages among components of this variable and salespeople’s performance, job satisfaction, extra-role behavior, organi-zational commitment, and intention to quit. Implications for sales manag-ers and researchmanag-ers are also offered.[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <docdelivery@ haworthpress.com> Website: <http://www. HaworthPress.com> © 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS. Industrial selling, salesperson performance, organiza-tional justice

Chia-Chi Chang is Assistant Professor, Department of Management Science, Na-tional Chiao-Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Road, Hsinchu, Taiwan 300, ROC.

Alan J. Dubinsky is Professor, School of Consumer and Family Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN.

Address correspondence to: Alan J. Dubinsky, School of Consumer and Family Sci-ences, Purdue University, 1262 Matthews Hall, West Lafayette, IN 47907-1262 (E-mail: dubinskya@cfs.purdue.edu).

The authors gratefully acknowledge anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, Vol. 12(1) 2005

http://www.haworthpress.com/web/JBBM 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.

Digital Object Identifier: 10.1300/J033v12n01_03 35

Employees expend their effort and time to acquire rewards from the organization. In fact, “work settings can be characterized by the outcomes stemming from them” Cropanzano and Greenberg (1997, p. 319). From performance appraisal to pay reviews and promotion decisions, such ac-tivities are ultimately related to issues surrounding resource or reward al-location. Employees have concerns about the fairness with which such rewards are distributed, as they seek equity when resources are allocated (Cropanzano and Greenberg 1997). Feelings of inequity can lead to unde-sirable consequences, such as employee physical or emotional with-drawal (Skarlicki and Folger 1997). Several alternative fairness norms have been observed in previous research, including the equity, equality, and needs norm; the equity norm, though, is the most prevailing norm in the organization (Leventhal 1976; Lin 1992).

Industrial and organizational psychologists have determined that the fairness of resource allocation decisions (i.e., the amount of the reward), as well as the process through which reward allocation decisions have been made, influences employee attitudes and behaviors. For instance, justice in an organization, or employees’ perceptions of fairness, have been identified as a key predictor of performance (e.g., Hendrix et al. 1998; Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991), job satisfaction (e.g., Folger and Konovsky 1989; Leung et al. 1996; Martin and Bennett 1996; McFarlin and Sweeney 1992), extra-role behavior (e.g., Malatesta and Byrne 1997; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994; Masterson et al. 2000; Moorman 1991; Niehoff and Moorman 1993), organizational commitment (e.g., Hendrix et al. 1998; Tang and Sarsfield-Baldwin 1996), and intention to leave the organization (e.g., Hendrix et al. 1998; Masterson et al. 2000; Robbins et al. 2000).

Notwithstanding the abundance of empirical work that has examined the issue of organizational fairness vis-à-vis employee outcomes, little research has been dedicated to exploring the effect of justice in a sales organization. This is surprising given that, salespeople, like other kinds of employees, not only have concerns about the fairness with which pay and promotions are dispensed, but also about such unique aspects of their jobs as territory assignment and quota allocation decisions. The few exceptions that have examined the effects of organizational justice have chiefly focused on the fairness of the outcome amount (Dubinsky and Levy 1989; Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995; Tyagi 1982; 1985)–or what is referred to as “distributive justice.” They generally have not investigated the process with which those allocation decisions were made–which is referred to as “procedural justice” (for an excep-tion, see Roberts, Coulson, and Chonko 1999).

36 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

The importance of salespeople’s perceptions of distributive and pro-cedural justice and the dearth of research in the area were the impetuses behind the present work. The purpose of this paper is to review salient literature in industrial and organizational psychology and sales manage-ment in an effort to propose linkages between salespeople’s perceptions of organizational justice and five key salesperson outcomes–perfor-mance, job satisfaction, extra-role behavior, organizational commit-ment, and intention to leave. Essentially, the current work extends extant sales management literature in two ways:

1. As noted above, most sales management equity research has fo-cused on distributive justice, or the amount of the reward alloca-tion decision. The present work will consider both the amount of the reward and the process of that decision–or both distributive justice and procedural justice.

2. Recent studies in industrial and organizational psychology (sub-sequently discussed) have found that procedural justice can be di-vided into two components–“interactional procedural justice” and “formal (or structural) procedural justice.” Both kinds of proce-dural justice are likely to be pertinent in selling and therefore will be introduced to the sales arena in the present paper.

The remainder of this paper will initially justify why perceptions of organizational justice are pertinent and important in a sales setting. Sec-ond, the three kinds of justice–distributive, formal procedural justice, and interactional procedural–will be described. Next, relationships among the three kinds of justice and the foregoing salesperson job-re-lated variables will be proposed. Finally, implications for managers and researchers will be offered.

IMPORTANCE OF JUSTICE IN SALES MANAGEMENT Organizational justice is important to employees in general and sales personnel in particular. The nature of the sales position suggests why it is of import in the selling arena.

Physical and Psychological Separation

Field salespeople are usually physical, socially, and psychologically separated from other company personnel (Dubinsky et al. 1986).

Al-Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 37

though this distancing can augment salespeople’s job latitude, it may also lessen salespeople’s “voice opportunity.” That is, salespeople might have fewer chances to express their opinion or provide input into the design and implementation of organizational policies. Accordingly, sales personnel might assume that because they are less visible, they will have reduced participation in the resource and reward allocation decision process. Demonstrating fairness through procedural justice can assure the sales force that simply because of its geographical es-trangement, it is not being ignored or inequitably treated when deci-sions about such allocations are made.

Lack of Close Supervision

The limited “human side” of sales supervision becomes especially in-fluential on salespeople’s perceptions of fair treatment from their manag-ers. The lack of close supervision requires sales managers to rely heavily on “indirect supervisory techniques,” such as quotas, territories, compen-sations plans, and expense policies (Stanton and Spiro 1999). Therefore, sales managers need to make sure that both the indirect supervisory tech-nique decisions and the process with which those decisions are made is fair. Given that these “rewards” are key resources available to salespeo-ple, sales personnel will judge whether they are fairly treated by both their supervisors and organizations vis-à-vis such job facets.

Multiple Role Partners

Salespeople have several roles as employees. So, they will likely be committed to multiple constituencies (e.g., supervisor, customers, sales peers). These specific commitments might lessen their global commitment to the organization (Hunt and Morgan 1994). In fact, Roberts, Coulson, and Chonko (1999, p. 3) suggest that “salespeople, as employees in a boundary organization with multiple allegiances and constituencies, may demon-strate less overall organizational commitment.” Salespeople’s perceptions of outcome fairness have been identified as a factor that can increase their organizational commitment (Roberts, Coulson, and Chonko 1999). There-fore, ignoring the impact of various justice perceptions on salespeople’s or-ganizational commitment appears unfounded.

Job Autonomy

The effect of procedural justice is likely to be marked where inde-pendence is highly valued (Triandis 1995). A predominant

characteris-38 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

tic of many sales positions is a high degree of autonomy (Anderson and Dubinsky 2004), a feature that has been found to have a salutary impact on salespeople (e.g., Jolson, Dubinsky, and Anderson 1987). Accord-ingly, sales personnel may place a high value on procedural justice, ow-ing to their potentially feelow-ing deprived of havow-ing minimal voice in or control over the process of resource allocation decisions.

Compensation Program

Salespersons’ perceptions of equity may differ from those of other employees because they are often compensated by some kind of incen-tive pay rather than merely by straight salary (Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995). This situation provides management opportunity to allo-cate another kind of reward–incentive pay–that generally is not avail-able to other kinds of employees. Because it is part of their income, the amount and the process through which this kind of reward is allocated across sales personnel will likely have an impact on salespeople’s per-ceptions of justice.

Lack of Clarity About Performance

Salespeople’s efforts do not always lead to a desired performance outcome, or reward. As expectancy theory (Vroom 1964) predicts, when employee instrumentality is low, a decrease in motivation to per-form follows. However, management can take action to stanch this in-imical impact by demonstrating that the performance-reward linkage (instrumentality) was determined fairly (procedural justice) and offers an equitable reward (distributive justice).

COMPONENTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL JUSTICE

Human behavior is directed by the outcome that people obtain (Lind and Tyler 1988), as individuals care about the outcome they receive (Thibaut and Kelly 1959). Therefore, justice researchers have examined the effect that outcome fairness has on organizational variables. Rooted in Adams’ (1963, 1965) equity theory, distributive justice (i.e., outcome fairness) has been an important topic for many researchers. In the 1970s, stimulated by the work of Thibaut and Walker (1975, 1978), jus-tice researchers discerned that people care not only about the outcome but also the process by which that outcome is determined. Thus,

empiri-Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 39

cal efforts began to focus on the impact that the procedures employed (procedural justice) to determine the outcome have on organizational variables. More recently, procedural justice has been divided into two components. Bies and Moag (1986) advocate that employees not only care about the process or procedures of outcome allocations (which they refer to as “formal procedural justice”), but also how these procedures are implemented– “interactional justice.” In the following sections, de-tails about each of the three justice components are discussed.

Distributive Justice

Distributive justice refers to the perceived fairness of the amount of the reward employees receive (Forger 1977). Homans (1961) pioneered research on distributive justice. He postulated the “rule of distributive justice.” This rule posits that when parties are in a social exchange rela-tionship, (a) the reward of each party will be proportional to the costs of each, and (b) the net rewards, or profits, will be proportional to each party’s investment. Extending Homans’ work, Adams (1963, 1965) proposed his theory of equity. According to equity theory, people will experience “inequity distress” when the ratio of one’s outcome (reward) compared to one’s input (contribution) is unequal to the corresponding ratio of a comparison other (Adams 1963; Cropanzano and Greenberg 1997). Feelings of distributive inequity aroused through such compari-sons can affect important employee work outcomes (e.g., Scharzwald, Koslowsky, and Shalit 1992).

Procedural Justice

Procedural justice refers to the process or procedures by which re-sources are allocated or decisions are made (e.g., policies and proce-dures used to design a compensation program, to evaluate employees’ performance, to provide pay raises) (Hendrix et al. 1998). Research demonstrates that the independent effect of distributive justice does not explain the entire variance in many organizational outcomes. That is, people not only care about the outcome amount, but also its allocation process. Early studies focused on how the structural elements of proce-dural justice influenced individuals’ perceptions of fairness. For exam-ple, voice and process control (Thibaut and Walker 1975), as well as different justice rules such as accuracy of the information and consis-tency of the rule determining the outcomes (Leventhal 1980), were ex-amined vis-à-vis procedural justice.

40 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

In general, findings suggest that people perceive as more fair procedures that give them considerable freedom in communicating their views, and re-act more favorably to such procedures. Indeed, the fre-act that people redound more favorably to an unfair outcome when they feel that fair procedures were utilized is one of the most robust findings in justice research (Lind and Tyler 1988). Barling and Philips (1993, p. 649) conclude that, “when em-ployees perceive the procedures as fair, they are less concerned about what might be perceived as an unfair outcome.” Other researchers have con-firmed this contention (Cropanzano and Folger 1996). Procedural justice has been found to be associated with such employee outcomes as perfor-mance, job satisfaction, extra-role behaviors, organizational commitment, and turnover (Folger and Konovsky 1989; Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991; McFarlin and Sweeney 1992; Moorman 1991).

Interactional Justice

The foregoing dialectic suggests that procedural justice is related to certain job outcomes (e.g., Lind and Tyler 1988). Some effects of proce-dural justice, though, have been determined to be related to the interper-sonal treatment employees receive during the enactment of procedural justice. This might include, for example, “showing respect and consid-eration, being sincere and honest, and offering justifications or explana-tions” (Masterson et al. 2000, p. 2). Therefore, procedural justice has been separated into two distinct constructs–“formal (or structural) pro-cedural justice” and “interactional justice,” (Bies and Moag 1986). For-mal procedural justice (hereafter referred to as “procedural justice” for brevity) refers to the structural elements of the process; interactional justice pertains to the interpersonal treatment employees receive during the implementation of the procedures. For instance, recent work has shown that salespeople’s perceptions of their managers’ trustworthi-ness are partially a function of how sales managers seek to develop trust (i.e., a process) with salespeople; such treatment then directly or indi-rectly affects several salesperson work outcomes (Brashear et al. 2003). Research suggests that salespeople’s perceptions of fairness influence the degree of trust they have in their manager (Strutton, Pelton, and Lumpkin 1993).

Fair Process Effect

Research has shown that people’s perceptions of outcome fairness are influenced by their perceptions of procedural justice. When

employ-Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 41

ees believe that decisions in the organization are made through a fair process, they are likely to perceive the outcomes as fair (Barling and Philips 1993; Lind and Tyler 1988). In fact, Moorman (1991) concludes that employees’ perceptions of procedural justice are positively related to their perceptions of distributive justice; this phenomenon has been re-ferred to as the “fair process effect” (McFarlin and Sweeney 1992). This phenomenon is especially likely to occur with negative outcomes (Greenberg 1987a; Lind and Tyler 1988).

Although evidence regarding this association has been established in a non-selling context, no research has been conducted in a sales context. A similar relationship, though, is likely to prevail among salespeople. Certain decisions sales managers make are difficult to quantify accu-rately (e.g., quality of territories, support from management, quota level) (Churchill, Ford, and Walker 1997). As such, substantiating or justifying the decision to salespeople can be fraught with difficulty. Therefore, sales personnel might well be querulous about the decision that was reached. The end result may be a declension in salespeople’s justice perceptions vis-à-vis the outcome (distributive justice). There-fore, the following proposition is posited:

Proposition 1: Salespeople’s perceptions of procedural justice are positively related to their perceptions of distributive justice.

POTENTIAL IMPACT OF ORGANIZATIONAL JUSTICE ON SALESPERSON WORK OUTCOMES

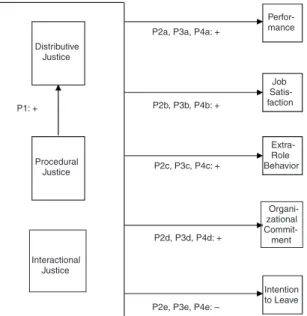

In the following sections, we examine how each justice construct (distributive, formal procedural, and interactional) is likely to be related to five salesperson work outcomes–performance, job satisfaction, ex-tra-role behavior, organizational commitment, and intention to leave/quit (see Figure 1). All studies used in developing the ensuing propositions are summarized in Table 1. Discussion is subdivided by type of organiza-tional justice vis-à-vis the five salesperson work outcomes.

Salesperson performance, job satisfaction, extra-role behavior, orga-nizational commitment, and intention to quit were selected as the job-related responses of interest for several reasons. First, they have re-ceived extensive research attention in the selling arena and are critical to the success of a sales organization (e.g., Churchill et al. 1985; Comer and Dubinsky 1985). Second, an abundance of research in nonsales contexts (subsequently discussed) has found that organizational justice

42 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

is related to these specific work outcomes; whether these same relation-ships are likely to apply in a sales environment is open to debate. Third, extant literature implies that these five variables tend to be related to one another (see Comer and Dubinsky [1985] for a review); therefore, if or-ganizational justice influences one of the salesperson job outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction), its ultimate impact is likely to be on yet another outcome (e.g., organizational commitment). Below, are definitions for each of the five salesperson job-related responses.

• Performance is the manner in which salespeople execute their tasks, responsibilities, and assignments and may affect the kinds and amounts of rewards they receive, thus influencing their moti-vation (Walker, Churchill, and Ford 1977).

• Job satisfaction refers to the affect salespeople have toward their work situation. It is an important precursor of several salesperson job-related outcomes (e.g., commitment, job performance) (see re-view by Comer and Dubinsky 1985).

• Extra-role behavior is employee behavior that is discretionary, that is not specifically recognized by the firm’s reward system, and

Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 43

Distributive Justice

P1: +

Perfor-mance P2a, P3a, P4a: +

Job Satis-faction P2b, P3b, P4b: + Procedural Justice Extra-Role Behavior P2c, P3c, P4c: + Interactional Justice Organi-zational Commit-ment P2d, P3d, P4d: + Intention to Leave P2e, P3e, P4e: –

FIGURE 1. Relationships Among Organizational Justice and Salesperson Work Outcomes

that has a salutary impact on the organization; moreover, it is not part of an employee’s job description and will not lead to punish-ment for failing to exhibit such behavior (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Rich 2001). It can be viewed as “discretionary behaviors on the part of the salesperson that directly promote the effective func-tioning of the organization, without necessarily influencing a salesperson’s objective sales productivity” (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Fetter 1993, p. 71) and is thus indicative of discretionary effort (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Paine 1999).

• Organizational commitment refers to “the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in an organiza-tion” (Mowday et al. 1979, p. 226). It represents the degree to which an individual has internalized (accepted) his or her com-pany’s values, beliefs, and objectives; is willing to expend high ef-fort in light of the firm’s goals; and is desirous of remaining with the organization (Porter et al. 1974). When employees are commit-ted to the organization, they tend to expend efforts that go beyond the expectation of their role, thus benefiting the organization (e.g., Ingram, Lee, and Lucas 1991).

• Turnover intention (intention to leave) refers to the likelihood that sales personnel will quit their jobs. As such, it is a proxy measure for job turnover (Comer and Dubinsky 1985). Although some turnover can be beneficial, a company can lose up to $40,000 if a productive salesperson departs and have sunk costs averaging $7,937 incurred in the training program (Roberts, Coulson, and Chonko 1999).

Potential Impact of Distributive Justice on Salesperson Work Outcomes Distributive Justice/Performance Linkage. Empirical work has gen-erally obtained a positive distributive justice/performance linkage in a nonsales environment (e.g., Adams 1963; Alexander and Ruderman 1987; Cropanzano and Randall 1993; Hendrix et al. 1998; Oldham et al. 1992; Shepard, Lewicki and Minton 1993); for exceptions, see Harder (1992), Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991), Pfeffer and Davis-Blake (1982), and Robbins et al. (2000). Tyagi (1982) suggests why the two variables should be positively related in a selling context. Using both equity and expectancy theories, he proposed a two-stage model explain-ing the motivational process of salespeople. He argues that salespeo-ple’s feelings of inequity adversely affect their motivation to perform. More specifically, among other things, inequity can lower their valence

44 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

T ABLE 1 Outcome Variable Type of Justice Distributive J ustice Procedural Justice Interactional Justice Author (year) S ample Hyp . Rel . Author (year) S ample Hyp. Rel . Author (year) S ample Hyp. Rel . Performance A dams (1963) Four studies (+) Taylor et al. (1987) 4 0 Canadian u ndergraduate students from other than psychology department (+) Brewer and Kramer (1986) 88 Undergraduate students in UCLA (+) Alexander and Ruderman (1987) Over 2,000 federal employees (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a p rivately owned pathology lab (+) Tyler e t a l. (1996) College students (+) Greenberg (1990a) Several just ice studies (+) Cropanzano and Folger (1996) Several justice studies (+) Hendrix e t a l. (1998) Employees from textile plants (+) Oldham et al. (1992) 2 6 5 e lectronic data processing employees from 20 departments of a government (+) Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university employees (+) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product company (+) Cropanzano and Randall (1993) Several s tudies (+) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product c ompany (+) Mast erson e t a l. (2000) 651 university employees (+) Shepard, Lewicki and Minton (1993) Several s tudies (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab ns Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants (through mediation o f o c) (+) Pfeffer and Davis-Blake (1982) University Professors ( ) Harder (1992) Professional athletes ( ) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab ns Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a tex-tile product c ompany ns 45

TABLE 1 (continued) Outcome Variable Type of Justice Distributive J ustice Procedural Justice Interactional Justice Author (year) Sample Hyp . Rel . Author (year) Sample Hyp. Rel . Author (year) Sample Hyp. Rel . Job Satis fac tion Folger and Konovsky (1989) 217 first-line e mployees of manufacturing plant (+) Alexander and Ruderman (1987) Over 2,000 federal employees (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a p rivately owned pathology lab (+) Moorman (1991) E m ployees from medium-sized companies (+) Moorman (1991) E m ployees from medium-sized companies (+) Moorman (1991) Employees from me-dium-sized companies (+) Mcfarlin and Sweeney (1992) Employees from a Midwestern bank (+) Mcfarlin and Sweeney (1992) Employees from a Midwestern bank (+) Manogran et al. (1994) 282 hourly production employees from automotive parts manufacturing company (+) Livingstone et al. (1995) 249 outside sales-people from e ight industry (+) Manogran et al. (1994) 282 hourly production employees from automotive parts manufacturing company (+) Masterson and Taylor (1996) 153 university e mployees (+) Leung et al. (1996) Employees from joint venture hotels (+) Leung et al. (1996) Employees from joint venture hotels (+) Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants (+) Martin and Bennett (1996) Employees from financial s ervices company (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab ns Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university e mployees (+) Tang et al. (1996) 200 employees in a medical c enter (+) Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university employees ns Leung et al. (1996) Employees from joint venture hotels ns Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab ns Extra-role Behavior D ittric h and Carroll (1979) 158 clerical employees in 20 departments o f a large m etropolitan area offic e (+) Farh et al. (1990) 195 employees with the T aiwanese Ministry of Communications (+) Moorman (1991) Employees from medium-sized companies (+) 46

Scholl e t a l. (1987) full-time employees of a large northeastern financial institution (+) Konovsky and Folger (1991) (N/A, unpublished manuscript) (+) Niehoff and Moorman (1993) Employees from a national movie theater management company (+) Farh et al. (1997) 227 employees of electronics industry in Taiwan (+) Moorman (1991) Employees from medium-sized companies (+) Manogran et al. (1994) 2 8 2 hourly production employees from automotive parts manufacturing company (+) Net e meyer e t al. (1997) Study 1: 115 salespeople from a c ellular c ompany Study 2 : Real estate salespeople ns (+) Niehoff and Moorman (1993) Employees from a national m ovie theater management company (+) Farh et al. (1997) 227 e mployees of electronics industry in Taiwan (+) Moorman (1991) Employees from medium-sized companies ns Konovsky and Pugh (1994) Employees of a hospital (+) Malat e st a and B yrne (1997) 1 7 2 pairs of university administrative e mployees (+) Niehoff and Moorman (1993) Employees from a national movie theater management company ns Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university employees (+) Mast erson e t al. (2000) University employees (+) Konovsky and Pugh (1994) Employees of a hospital ns Manogran et al. (1994) 2 8 2 hourly production employees from automotive parts man-ufacturing company ns Schappe (1998) Employees from a mid-Atlantic insurance ns Manogran et al. (1994) 2 8 2 hourly production employees fro m a u to m o tiv e parts manufacturing company ns Farh et al. (1997) 227 employees of electronics industry in Taiwan ns Schappe (1998) Employees from a mid-Atlantic insurance ns O rganizational Commit m ent Dubinsky and Levy (1989) 238 retail salespeople (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab (+) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab (+) Mcfarlin and Sweeney (1992) Employees from a Midwestern bank (+) Mcfarlin and Sweeney (1992) Employees from a Midwestern bank (+) Barling a nd Philips (1993) St udent s in p sychology and MBA p rogram (+) Tang et al. (1996) Employees in a m edical center (+) Manogran et al. (1994) 282 hourly production e m p loyees from automotive parts manufacturing company (+) Malat e st a and B yrne (1997) 172 pairs of university administrative employees (+) Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants (+) Masterson and Taylor (1996) 153 university e m-ployees (+) Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants (+) Roberts et al. (1999) 249 outside salespeople from eight industry (+) Malatesta and Byrne (1997) 172 pairs of university administrative employees (+) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product c ompany (+) 47

TABLE 1 (continued) Outcome Variable Type of Justice Distributive J ustice Procedural Justice Interactional J ustice Author (year) S ample Hyp. Rel . Author (year) S ample Hyp. Rel . Author (year) S ample Hyp. Rel . Organizational Commit m ent (c ont.) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product c ompany (+) Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university employees (+) Manogran e t a l. (1994) 2 8 2 hourly production employees from automotive parts manufacturing company ( ) Manogran et al. (1994) 282 hourly production employees from automotive parts manufacturing company ( ) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product company (+) Mast erson e t a l. (2000) 651 university employees ns Folger and Konovsky (1989) 217 first-line e mployees of manufacturing plant ns Barling and Philips (1993) Students in psychology and MBA program ns Barling and Philips (1993) St udent s in p sychology and MBA p rogram ns Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university employees ns Intention to Leave Scholl e t a l. (1987) full-time employees of a large northeastern financial institution ( ) Alexander and Ruderman (1987) Over 2,000 federal employees ( ) Mast erson and Tay-lor (1996) 153 university employees ( ) Alexander and Ruderman (1987) Over 2,000 federal employees ( ) Masterson and Taylor (1996) 153 university employees ( ) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product company ( ) Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants ( ) Roberts et al. (1999) 249 outside salespeople from eight industry ( ) Hendrix et al. (1998) Employees from textile plants ( ) Roberts et al. (1999) 249 outside salespeople from eight industry ( ) Mast erson e t al. (2000) 651 university employees ( ) Mast erson e t a l. (2000) 651 university employees ( ) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product c ompany ( ) Robbins et al. (2000) Employees from a textile product company ( ) Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab ns Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a p rivately owned pathology lab ns Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991) Employees of a privately o wned pathology lab ns 48

and instrumentality, two essential components of expectancy theory of motivation (Vroom 1964).

When salespersons perceive rewards as inequitable (e.g., they earn more/less than their peers because of a good/poor territory rather than by expending additional effort), they likely attach a lower valence (i.e., desirability of the reward) to their reward. The need to achieve equity might have a greater impact on salesperson motivation to perform than the desire to maximize economic gains (Tyagi 1982). That is, a too large but inequitable amount of pay may engender a lower valence than a smaller but equitable amount of pay. The lower valence attached to the reward precipitates the lower motivation to perform (Vroom 1964).

If salespeople perceive that they are not compensated based on their performance level, feelings of inequity are also likely to arise (Chur-chill, Ford, and Walker 1979). Such perceptions about reward inequity likely depress their belief that good performance will bestow on them desired outcomes (i.e., instrumentality). Experiments in sales confirm this viewpoint (e.g., Litwin and Stringer 1968). So, when rewards are not consistently contingent on performance, sales personnel are likely to perceive an increased risk of not being equitably compensated and therefore reduce their instrumentality beliefs.

The foregoing discussion implies that equitable perceptions play an important role in determining salespeople’s motivation to perform. The linkage between salespeople’s motivation and performance has clearly been demonstrated in previous research (e.g., Churchill et al. 1985; Comer and Dubinsky 1985). Hence, it appears reasonable to offer the following proposition:

Proposition 2a: Salespeople’s perceptions of distributive justice will be positively related to salespeople’s performance.

Distributive Justice/Job Satisfaction Linkage. Research in non-sales settings generally suggests that distributive justice will have a salutary impact on job satisfaction (Folger and Konovsky 1989; Hendrix 1998; Leung et al. 1996; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994; Martin and Bennett 1996; McFarlin and Sweeney 1992; Moorman, 1991; Tang et al. 1996). A similar situation is likely to prevail in selling because the outcome performance of salespeople is relatively easy to quantify (e.g., whether quota is achieved or exceeded). As such, it should be reason-ably uncomplicated for salespeople to compare the ratio between their input and output to others’ ratios; the result of this comparison is likely

Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 49

to influence the affect (job satisfaction) sales personnel have toward their jobs. The nature of the sales position suggests a possible rationale.

Salespeople’s feelings of inequity can come from many sources. Al-though salespeople typically obtain most organizational rewards that colleagues in other functional areas receive (e.g., recognition, salary raises, fringe benefits, promotions), they also pay attention to whether they are being treated fairly vis-à-vis such sales job features as assign-ment of territories, accounts, sales quotas, and expense accounts (Tan-ner and Castleberry 1986). Outside salespeople tend to have numerous contacts with both salespersons from other organizations and custom-ers, both important sources of information (Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995). These contacts should assist sales personnel to detect unfair treatment. Indeed, facets of both internal and external equity (e.g., raise, fringe benefits, promotion, incentive, salary, recognition) have been discerned to be positively related to salesperson job satisfac-tion (Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995). These findings imply that salespeople compare themselves not only with sales peers in their own organization, but also with salespeople outside of the organization and that both comparisons can have a significant impact on salespeo-ple’s job satisfaction. Thus, the following proposition is proposed:

Proposition 2b: Salespeople’s perceptions of distributive justice are positively related to their job satisfaction.

Distributive Justice/Extra-Role Behavior Linkage. Organ (1988) claims that distributive justice brings about extra-role behavior of em-ployees when emem-ployees have a social exchange relationship rather than one that entails purely an economic exchange (Blau 1964; Robin-son, Kraatz and Rousseau 1994) with their employers. Based on equity theory (Adams 1963), people feel tension when they are treated unfairly (either over- or under-rewarded). As a consequence, in order to reduce the tension they feel, they decrease extra-role behavior when underpaid and increase it when overpaid. Netermeyer et al. (1997) reviewed previ-ous justice literature and proposed a positive association between re-ward allocation fairness (distributive justice) and salesperson extra-role behavior (through the mediating effect of job satisfaction). This asser-tion was supported in one of their two samples. Farh, Earley, and Lin (1997) investigated the effect of distributive justice on extra-role behav-ior of Chinese employees and observed that distributive justice is posi-tively related to various facets of extra-role behavior. Notwithstanding the foregoing findings, other empirical studies have noted that when

50 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

procedural justice (a combination of both formal procedural justice and interactional justice) was taken into consideration, the effect of distribu-tive justice was vitiated (Konovsky and Pugh 1994; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994; Moorman 1991; Niehoff and Moorman 1993).

Admittedly, research results are mixed regarding the distributive jus-tice/extra-role behavior linkage in a nonsales milieu. The nature of the sales position, as well as studies in the selling arena, though, may beto-ken the direction of the association between these two variables. First, sales personnel usually represent multiple role partners in the execution of their job–their clients, their manager or organization, even their co-workers; this situation affords salespeople opportunity to engage in a panoply of extra-role behaviors. A partial condition for engaging in such discretionary effort is the perception that they are being treated fairly: “If sales personnel perceive that they are not rewarded justly . . . [they will be] unlikely to take on additional work . . .” (Dubinsky and Skinner 2002, p. 593).

Second, as noted earlier, sales personnel typically have much job lati-tude (e.g., Castleberry and Tanner 1986). They can thus allocate their time essentially as they deem appropriate. If they feel aggrieved about reward allocations (perceived inequity), they are likely to adjust their behavior accordingly (Adams 1963; Dubinsky and Skinner 2002). Cer-tain situational constraints (e.g., need to achieve quota) conceivably will prevent sales personnel from reducing their in-role work efforts in such situations, but they may well decrease their extra-role behaviors according to the degree to which they perceive organizational unfair-ness (Robinson, Kraatz, and Rousseau 1994).

Third, team selling has increased in pervasiveness and will most likely continue to do so (Ingram 1996). Performing extra-role behaviors within a team can enhance teamwork effectiveness and efficiency. However, working in teams can make it difficult for salespeople to form a linkage between their specific input and possible rewards. This nebu-lousness might lead to inaccurate equity perceptions. Indeed, there might even be circumstances under which sales personnel do not feel re-warded for something they perceive merits rewarding. Consequently, the aggrieved parties will conceivably reduce their extra-role behavior to adjust for their cognitive dissonance (Adams 1963).

And fourth, recent studies have found that extra-role behaviors of salespeople are a stronger determinant of sales mangers’ evaluation of the performance of their sales personnel than objective productivity (Mackenzie, Podsakoff, and Fetter 1993; Netemeyer et al. 1997).

Sales-Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 51

people who perceive the same input/output ratio as those of others might obtain different rewards because their levels of extra-role behav-iors differ. Along the same line, salespeople may acquire the same re-wards even though they have different objective productivity because of discordant levels of extra-role behaviors demonstrated by them. When extra-role behaviors are considered part of performance evalua-tion criteria, stating clearly what is rewarded or at least appreciated in the organization (distributive justice) conceivably will have a positive effect on extra-role behaviors. These foregoing arguments lead to the following proposition:

Proposition 2c: Salespeople’s perceptions of distributive justice are positively related to their extra-role behavior.

Distributive Justice/Organizational Commitment Linkage. Hendrix et al. (1998, p. 614) assert that outcome fairness will have a positive ef-fect on employees’ organizational commitment because “an equitable distribution of a pay raise strengthens the bond of loyalty between em-ployees and their company.” Indeed, many studies in industrial and or-ganizational psychology have found a positive link between distributive justice and nonsales employees’ organizational commitment (e.g., Hendrix et al. 1998; Robbins et al. 2000; Tang and Sarsfield-Baldwin 1996). Although non-selling research generally has found that a fair outcome is positively related to increased employee organizational commitment, a few studies have obtained a nonsignificant finding (Barling and Philips 1993; Folger and Konovsky 1989; Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991).

Despite some inconsistent evidence about the distributive justice/or-ganizational commitment linkage in nonsales settings, results using sales samples are consistent. Dubinsky and Levy (1989) surveyed 238 retail salespeople and found that facets of distributive justice are posi-tively related to organizational commitment. Using a sample of 249 field salespeople, Roberts, Coulson, and Chonko (1999) discerned that facets of internal and external equity (a form of distributive justice) are significant predictors of organizational commitment. Furthermore, they concluded that, contrary to previous findings (e.g., Folger and Konovsky 1989; McFarlin and Sweeney 1992), distributive justice has a greater impact on employee organizational commitment than does procedural justice.

The foregoing findings and discussion allow the following proposi-tion to be proffered:

52 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

Proposition 2d: Salespeople’s perceptions of distributive justice are positively related to their organizational commitment.

Distributive Justice/Intention to Leave Linkage. Only one study was found that observed a nonsignificant distributive justice/intention to quit relationship (Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991). More recent work, however, has generally tended to determine that nonsales employees’ perceptions of distributive justice are negatively related to their inten-tion to quit (Alexander and Ruderman 1987; Hendrix et al. 1998; Rob-bins et al. 2000). Using a sample of field salespeople, Roberts, Coulson, and Chonko (1999) discerned that external perceptions of salary or pro-motion inequity lead to higher turnover intentions. This finding is intu-itively appealing because salespeople have contacts with clients and salespeople from outside organizations (Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995) and thus have increased opportunity to obtain relevant information regarding external equity issues. Perceived inequity rela-tive to other referent organizations may well lead salespeople to con-sider alternate sales jobs. The findings suggest that a fair outcome should lead to a decreased intention to quit among sales personnel.

Proposition 2e: Salespeople’s perceptions of distributive justice are inversely related to their intention to leave the organization. Potential Impact of Procedural Justice on Salesperson Work Outcomes

Procedural Justice/Performance Linkage. Empirical work in indus-trial and organizational psychology has found that procedural justice is a significant, positive predictor of performance (e.g., Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991; Taylor, Moghaddam, Gamble, and Zellerer 1987). Cropanzano and Folger (1996) reviewed several empirical studies and reported that individual performance increased significantly when a negative outcome was accompanied by fair procedures but decreased when a negative outcome was followed by unfair procedures. They aver (p. 81): “If administrative conduct and procedures are just, people are predicted to work within the system (e.g., increased performance).”

A similar situation is likely to prevail in a selling milieu. When sales personnel receive an outcome perceived of as unjust, they will still work hard if procedures are fair. As noted earlier, because sales personnel generally are geographically estranged from their managers, they may not have opportunity to participate in a decision that affects them (e.g., pay raises); consequently, they are unlikely to know the details of the

Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 53

discussion that ultimately led to the final decision. But if salespeople feel confident that the rules employed to make the decision were fair, then they are likely to accept the decision (Cropanzano and Folger 1996). Furthermore, many management decisions (e.g., territory as-signments, account asas-signments, quota levels) have an impact on sales-persons’ rewards. When sales personnel believe that the rewards they are receiving have been determined fairly, they are likely to seek to per-form at levels that will bestow on them desirable rewards (Walker, Churchill, and Ford 1979).

The aforementioned discussion leads to the following proposition: Proposition 3a: Salespeople’s perceptions of formal procedural justice are positively related to their performance.

Procedural Justice/Job Satisfaction Linkage. Organizational psy-chologists suggest that procedural justice in an organization enhances employees’ performance by first increasing their satisfaction (Lind and Tyler 1988). Admittedly, salespeople are usually physically and so-cially separated from their organization, which is likely to reduce their input into key management decisions. Thus, their knowing that the pro-cedures used to allocate resources are fair seems paramount. Such apperception should afford them opportunity to proceed with their work without being concerned that their absence jeopardized their situation vis-à-vis the decision (Dubinsky et al. 1986). Ensuring sales personnel that their interests have or will be taken into consideration should have a favorable effect on their job satisfaction (Leventhal 1980). Research supports this notion in non-sales arenas (e.g., Leung et al. 1996; Moorman 1991; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994). Consequently, the following proposition is promulgated:

Proposition 3b: Salespeople’s perceptions of procedural justice are positively related to their job satisfaction.

Procedural Justice/Extra-Role Behavior Linkage. Some evidence from industrial and organizational psychology indicates that extra-role behavior is positively related to formal procedural justice (Masterson et al. 2000; Niehoff and Moorman 1993). Despite these findings, other studies have demonstrated a non-significant relationship between for-mal procedural justice and employee extra-role behavior (Farh, Earley, and Lin 1997; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994; Moorman 1991; Schappe 1998).

54 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

The inconsistent results regarding the association between proce-dural justice and employee extra-role behavior do not provide a clear picture of what the relationship between these two variables might be in a selling context. Again, the nature of the selling position can possibly shed further light on this issue. Field sales personnel generally have rel-atively little interaction with their supervisor–they are managed from afar–or even with their sales peers (Dubinsky et al. 1986). Essentially, there is likely to be some organizational estrangement owing to this physical separation. This situation may increase salespeople’s ambigu-ity regarding what is happening in the organization and how this will in-fluence them. If they feel that they are being treated equitably vis-à-vis reward allocation processes, however, their potential discomfort about company fiats or activities that may affect them might be assuaged. Feelings of fairness conceivably would impel them to expend discre-tionary effort and engage in extra-role behavior.

Additionally, according to the group-value theory (Tyler, Degoey, and Smith 1996), employees treated with dignity and respect will com-municate the message that they are valued members in the organizations. When salespeople feel respected and valued in their organizations, they are more likely to value the harmony of the organization and feel that they should go for “the extra mile” for this organization. For example, giving salespeople the opportunity to provide input in the decision-making pro-cess will probably be perceived of as fair not only because it allows salespeople to have an impact on resource allocation but also because it conveys the message that the sales group values their opinions (Tyler, Degoey, and Smith 1996). Under these circumstances, salespeople seemingly should be motivated to maximize the benefits for the whole group rather than just for themselves.

Also, there may be an increased tendency for sales managers to as-sess salespersons’ extra-role behavior during performance evaluations. Therefore, sales managers should make the procedures of decision making more consistent and unbiased (Mackenzie, Podsakoff, and Fet-ter 1993; Netemeyer et al. 1997). Salespeople’s enhanced perceptions of procedural justice should then increase extra-role behavior, as they will no longer feel unfairly treated simply because the procedures about decision making process are not clear.

Individuals tend to identify the accountable party when dealing with injustice (Folger and Cropanzano 1998). Once they identify the party, their reactions are then targeting at the responsible party. Compared with interactional justice, the structural element of procedural justice appears to be derived from the organization rather than salespeople’s

Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 55

superiors (Masterson et al. 2000). Therefore, procedural justice should mainly have an impact on organization-oriented extra-role behavior rather than supervisor-oriented extra-role behavior. Hence, we propose the following proposition:

Proposition 3c: Salespeople’s perceptions of procedural justice are positively related to their organization-oriented extra-role be-havior.

Procedural Justice/Organizational Commitment Linkage. Save for nonsignificant findings of Barling and Philips (1993), the preponderance of studies has demonstrated a positive relationship between procedural justice and organizational commitment (Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994; Masterson et al. 2000; Masterson and Taylor 1996; McFarlin and Sweeney 1992; Robbins et al. 2000). Hendrix et al. (1998, p. 614) suggest a possible explanation for these findings: “[Employees’ perceptions of fair procedures are] likely to cause workers to have faith in the system, which may lead to higher organizational commitment, regardless of outcome.” Similar logic should conceivably apply in a selling context.

Because sales personnel are usually physically and psychologically separated with their superiors and their colleagues (Dubinsky et al. 1986), they may be worried about being “out of sight, out of mind.” Therefore, there is a need to demonstrate to them that they are actually treated fairly because the structure of the procedure (which is fixed) is fair. For example, they can have input into decisions that are made in the organization. Sales managers also have to demonstrate that the proce-dures are the same for everybody (unbiased principle). And, if salesper-sons feel that the decision is not fair, they should also have the right to appeal (Leventhal 1976)–even just to speak out why quota was not achieved for the month. These psychological consequences of the “fair procedure” effect (McFarlin and Sweeney 1992) should reduce their concern about the “out of sight, out of mind” effect and therefore lead to stronger faith in the organization in terms of the decision-making pro-cess.

Based on the preceding discussion, the following proposition is pos-ited:

Proposition 3d: Salespeople’s perceptions of procedural justice are positively related to their organizational commitment.

56 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

Procedural Justice/Intention to Leave Linkage. Evidence has tended to find a significant inverse relationship between procedural justice and employees’ intention to leave the organization (Masterson et al. 2000; Masterson and Taylor 1996; Robbins et al. 2000). Only one study was found that failed to support the inverse procedural justice/intention to quit relationship (Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991).

The physical separation between sales personnel and their manager seemingly makes procedural justice a vital factor in order to retain salespeople in the organization. Salespeople might feel that their ab-sence from the sales office engenders suboptimal consequences vis-à-vis their participation in the decision-making process. Perceptions of fair process in the organization should conceivably decrease the like-lihood of salespeople’s feeling mistreated simply because of their phys-ical separation (Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995). Salespeople might decide to leave the organization when they perceive inequity originating from unjust procedures, as self-termination can be a result of perceived inequity (Dittrich and Carroll 1979; Skarlicki and Folger 1997). Therefore, increasing their perception of organizational proce-dural justice might well reduce turnover intentions of salespeople.

The previous discussion allows the following proposition to be prof-fered:

Proposition 3e: Salespeople’s perceptions of procedural justice are inversely related to their intention to leave the organization. Potential Impact of Interactional Justice on Salesperson Work Outcomes

Interactional Justice/Performance Linkage. Much work has been done showing the positive effect of interactional justice on performance (Brewer and Kramer 1986; Hendrix et al. 1998; Masterson et al. 2000; Robbins et al. 2000; Tyler, Degoey, and Smith 1996); see Konovsky and Cropanzano [1991] for an exception). Sales managers can have a strong impact on salespeople’s performance (Walker, Churchill, and Ford 1977). In fact, research in sales management suggests that how sales managers treat their salespeople is positively related to their per-formance (Castleberry and Tanner 1986; Tanner and Castleberry 1990). If managers allocate to some salespersons better territories, smaller quotas, or more generous expense accounts, those salespeople should have an increased chance of being successful (Dubinsky 2000). Sales-people with less auspicious working conditions, however, might well regard their situations to be unjust and thus may lower their motivation

Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 57

to perform because they do not expect their efforts to engender the de-sired performance. The foregoing thus suggests the following proposi-tion:

Proposition 4a: Salespeople’s perceptions of interactional justice are positively related to their performance.

Interactional Justice/Job Satisfaction Linkage. Respectful treatment from management seemingly betokens a favorable relationship be-tween the company and employees. Tyler, Degoey, and Smith (1996) provide a possible explanation for this effect using social identity the-ory. Social identity theory avers that people interact with others because they use others as a source of information about their social identities. In other words, people make inferences about their status based on the treatment they receive. Save for one exception (Leung et al. 1996), rela-tively similar expectations and findings have been noted in nonsales contexts (e.g., Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991). Indeed, some people consider interactional justice as the social aspect of procedural justice because it contains two main elements: (a) pride and respect and (b) in-formation justification (e.g., Cropanzano and Greenberg 1997).

Fair treatment can convey to salespersons that they are respected within their organization (Strutton, Pelton, and Lumpkin 1993) (a la so-cial identity theory). Treating salespeople fairly and with respect is likely to induce salespeople to possess pride in their organization and contribute to favorable perceptions of their managers (Rich 1998). Pre-vious work in sales management suggests that how sales managers treat their salespeople is positively related to their job satisfaction (Castle-berry and Tanner 1986; Tanner and Castle(Castle-berry 1990). Perceptions of favorable interactional fairness likely lead individuals to feel that they are a valued employee and therefore develop a sense of pride working in their organization; such feelings could conduce to a positive impact on job satisfaction (Rich 1998).

In general, the foregoing previous research and logic suggest the fol-lowing proposition may be offered:

Proposition 4b: Salespeople’s perceptions of interactional justice are positively related to their job satisfaction.

Interactional Justice/Extra-Role Behavior Linkage. Although Schappe (1998) found no significant association between interactional justice and extra-role behavior of nonsales employees, most prior work has

ob-58 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

tained a positive relationship between these two variables (Farh, Earley, and Lin 1997; Malatesta and Byrne 1997; Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994; Masterson et al. 2000; Moorman 1991; Niehoff and Moorman 1993). In a selling milieu, though, interactional justice will likely chiefly affect salespeople’s extra-role behavior toward their managers. According to Folger and Cropanzano (1998), individuals tend to identify the accountable party when dealing with (in)justice. Once they identify the party, their reactions are then targeted toward it. Sales managers conceivably represent the party primarily responsible for salespeople’s perceptions of interactional justice (owing to their po-tential connectedness with and impact on their sales personnel). The ex-change relationship between sales managers and subordinates can be enhanced when salespeople feel fairly treated interpersonally; the result is salespeople’s increased likelihood of engaging in tasks that are outside the purview of their job description–extra-role behaviors (Castleberry and Tanner 1986)–that facilitate the manager’s work efforts (a la a quid pro quo). Therefore, interactional justice should mainly have an effect on supervisor-oriented extra-role behaviors rather than organization-oriented extra-role behavior. Hence, we proffer the following:

Proposition 4c: Salespeople’s perceptions of interactional justice are positively related to their supervisor-oriented extra-role behavior. Interactional Justice/Organizational Commitment Linkage. Work in industrial and organizational psychology has generally demonstrated a positive association between interactional justice and employee organi-zational commitment (Barlin and Philips 1993; Hendrix et al. 1997; Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991; Malatesta and Byrne 1997; Robbins et al. 2000). Despite these findings, some empirical efforts have ob-tained different results: a nonsignificant relationship (Masterson et al. 2000) and a negative association (Manogran, Stauffer, and Conlon 1994). Conceivably, perceived fairness of interpersonal treatment should lead to increased salesperson organizational commitment.

There are at least two ways that interactional justice may influence salespeople’s organizational commitment. First, advantageous and fair interpersonal treatment is likely to affect salespeople’s satisfaction with the praise they receive through their interactions. This, in turn, can aug-ment salespeople’s organizational commitaug-ment (Hendrix et al. 1998). Second, fair treatment from superiors should lead employees to feel re-spected and proud of the organization; such feelings can facilitate their identifying with and internalizing the values of the organization (Brewer

Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 59

and Kramer 1986). Value internalization is a hallmark of salespeople’s organizational commitment (Ingram, Lee, and Lucas 1991). Therefore, the following proposition is promulgated:

Proposition 4d: Salespeople’s perceptions of interactional justice are positively related to their organizational commitment.

Interactional Justice/Intention to Leave Linkage. Investigations in industrial and organizational psychology have typically found an in-verse association between interactional justice and employees’ inten-tion to leave (Greenberg 1990; Masterson and Taylor 1996; Masterson et al. 2000; Robbins et al. 2000). Konovsky and Cropanzano (1991), however, discerned that employees’ perceptions of the fairness of inter-personal treatment are unrelated to intention to leave.

Although no published research has examined the effect of interactional justice on salespeople turnover intention, Castleberry and Tanner (1986) suggest that the way sales managers treat their subordi-nates determines the quality of their exchange relationship and can in-fluence turnover intentions. For example, if sales managers give “cadre” salespeople (those having a good exchange relationship) higher or more flexible expense accounts or negotiate harder for them in order to obtain enhanced concessions (e.g., discounts, expedited delivery time, enhanced financing terms), they are likely to view their situation as favorable and that the manager is facilitating their performance. As such, sales personnel are likely to view their organization as being sup-portive of their efforts and desirous of seeing them succeed (in contrast to sales personnel who do not receive such auspicious treatment). Such perspectives will conceivably lead salespersons to have a desire to re-main in the organization, rather than thinking about departing. There-fore, we propose the following proposition:

Proposition 4e: Salespeople’s perceptions of interactional justice are inversely related to their intention to leave the organization.

DISCUSSION

The major purpose of this paper was to develop a set of justice-based propositions in a selling context. Although recognition of organiza-tional fairness has been growing in the sales literature, most of the extant literature has focused on the equity of resource allocations (e.g.,

60 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING

pay raise amount, promotion, fringe benefits, territory assignment, quota level) (Dubinsky and Levy 1989; Livingstone, Roberts, and Chonko 1995; Tyagi 1982, 1985)–or on distributive justice. Although outcome fairness is a critical component of organizational justice, it does not repre-sent the entire picture. A major contribution of this paper was to articulate the importance of the process in making such decisions, the manner in which the procedures are executed, and their impact on various organiza-tional outcomes. The current paper conceptualized organizaorganiza-tional justice as a multidimensional concept so as to enhance understanding of its dif-ferential effects. Prior to the present research effort, the overriding as-pects of organizational justice (distributive, formal procedural justice, and interactional) and their potential effects on various salesperson job outcomes had not been examined separately.

Relationships Among Justice Constructs

The relationships among different justice constructs was an additional focus of the current research. Although work in industrial and organiza-tional psychology has demonstrated that employees have greater job sat-isfaction when they perceive that the outcome and the process through which the outcome was determined are fair (a high correlation between distributive justice and formal procedural justice) (Barling and Philips 1993; Cropanzano and Greenberg 1997), this same relationship had never been considered in a selling context. The nature of the sales posi-tion, as well as findings from previous industrial and organizational psy-chology empiricism, implies that a similar association can be expected. In addition, although little published research has been done, interactional justice may well influence salespeople’s perceptions of procedural jus-tice. For example, Greenberg (1990) noted that perceptions of procedural justice are enhanced when adequate and sincere explanations are offered for organizational outcomes (a la fair interactional justice). Additionally, the more sincere an explanation is perceived to be, the fairer it is per-ceived to be. As such, interrelationships among different justice con-structs (distributive, procedural, and interactional justice) should be explored in a sales setting to gain an increased understanding of justice dynamics in this venue.

Managerial Implications

If the propositions developed here obtain empirical support, then sev-eral managerial implications outlined below will apply. A major

impli-Chia-Chi Chang and Alan J. Dubinsky 61

cation of previous procedural justice research in a legal context is that it is possible to enhance social life by establishing proper procedures without allocating additional resources (Lind and Tyler 1988). This in-ference has applicability in organizational settings. For instance, con-ceivably salesperson work outcomes can be enhanced by improving salespeople’s perceptions of fairness without consuming more organi-zational resources. Because organiorgani-zational justice can influence an ar-ray of salespeople’s outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment), sales managers should seek to use procedures that are fair and treat their sales personnel equitably whenever dispensing out-comes/rewards (e.g., compensation, territories, quotas). In addition, based on the findings of previous justice research, one major element of justice is the opportunity to express one’s voice. Therefore, if sales managers allow subordinates to express their voice when making deci-sions concerning such issues as territory or account assignments, these efforts may have a salutary impact on key work-related behaviors and attitudes of sales personnel (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational com-mitment, performance).

Furthermore, instead of passively waiting for sales subordinates to express their opinions, sales managers may even want to solicit employ-ees’ input about certain matters in order to enhance people’s percep-tions of fairness. Doing so requires two-way communication between managers and salespeople that informs salespeople that their view-points are truly desired and important and their interests are of concern in the decision-making process (Greenberg 1986).

When in instances that the procedures of the organization are not es-tablished or executed by salespeople’s own managers, sales personnel will likely have negative reactions if they view the procedures to be un-fair. When this happens (i.e., the organizational procedures have been fixed), sales managers will need to explain why and how those deci-sions were made. Through such efforts, they will be engaging in interactional justice. If the managers provide fair interpersonal treat-ment of their sales personnel, sales subordinates should have enhanced fairness perceptions. As such, managers will be conveying to the sales-people that they are respected in the organization (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler, Degoey, and Smith 1996). This, in turn, can enhance salesper-sons’ work behaviors and attitudes (Konovsky and Cropanzano 1991; Lind and Tyler 1988).

Moreover, there are also a couple of principles that sales managers can follow in order to increase their subordinates’ perceptions of proce-dural justice. For example, sales managers should strive to be accurate

62 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS MARKETING