行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

自由貿易思想與近代國家貿易制度的建立

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC91-2414-H-004-028- 執行期間: 91 年 08 月 01 日至 92 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立政治大學政治學系 計畫主持人: 何思因 報告類型: 精簡報告 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 93 年 2 月 19 日

近代國家自由貿易的思想在經兩百年的演進已是經濟學中最重要正統思想之一(Irwin, 1996)。 而近代國家貿易制度的建立,除了受自由貿易思想的影響外,還受到另外兩個思潮的影響。這兩 個思潮一是重商主義,一是福利國家。重商主義係以追求富強為主,也就是假定每個國家的國際 地位係基於該國與他國的相對所得。這個相對所得也就是我方的貿易所得一定是他國之失,反之 亦然。因此在貿易體制上,最好能設置各種貿易機制,只賣不買,以累積外匯,強化國力。第二 個思潮則是基於貿易一定會引起社會經濟的重新分配,因為福利國家一定要顧及這種重新分配後 的弱勢群體,因此在貿易機制上,一定要能確定輸家也要獲得相當補償。因此說的更精確一些, 就是自由貿易的體制,它不能只反應自由貿易的思想,它還有國際政治的顧慮(重商主義),以 及國內政治的顧慮(福利國家)。如果一個國家一意追求自由貿易體制,但這個體制因為缺乏政 治的支柱,它反而不易維持。如果自由貿易體制在設計上,能稍微顧及政治層面,那麼這個體制 才能有向自由貿易方向運作的可能。就美國的自由貿易體制而言,其設計就反應了重商主義及福 利國家的思潮(Goldstein, 1993);日本的貿易制度則更往重商主義的方向傾斜(Johnson, 1982. )。我把這樣的觀察用在解釋台灣的貿易政策(政策亦是制度的一部份)。該文已被 Journal of Contemporary China 初步接受。

Johnson, Chalmers, MITI and the Japanese Miracle, Stanford University Press: 1982. Judith Goldstein, Ideas, Interests, and American Trade Policy, Cornell University Press, 1993.

Douglas A. Irwin, Against the Tide, Princeton University Press, 1996.

Accounting for Taiwan’s Economic Policy toward China

BySzu-yin Ho

Professor of Political Science and

Tse-Kang Leng Associate Research Fellow Institute of International Relations National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan

In early April, Japanese consultant-turned-management guru Kenichi Ohmae and American lawyer-turned-China observer Gordon Chang sparred in Taipei over the future of China and, hence, Taiwan (China Times, April 3, 2003, p.2). Ohmae makes it clear that China is to become an economic power and Taiwan should make good use of China’s potential to develop itself. On the other hand, Chang believes China now harbors high political and commercial risks and Taiwan should diversity its reliance on Chinese market. These two opposing views epitomize the two lines of thinking in Taiwan’s

perennial policy debate regarding its economic relations to China. We will examine in this paper the ideas, institutions, and interests in which Taiwan’s economic policy toward China is embedded. A conclusion will then be drawn.

Ideas in Taiwan’s Economic Policy toward China

Taiwan had long been hailed for its economic development. For example, the World Bank lists Taiwan as one of the East Asian economic miracles (World Bank, 1993). And many professional journal articles and books have probed the success formula of Taiwan—and other East Asian newly industrializing economies (NIEs) as well. While these academic researches differ in the details of East Asian NIEs’ development trajectories, they generally agree that the states in these NIEs had practiced what Robert Wade calls “governed market” (Wade, 1990). The market-conforming policies adopted by the NIEs’ states had strong effects in stimulating economic growth. While this “developmental state” image was tarnished in the wake of 1997 Asian financial crisis, Taiwan’s economic developmental model still retained some luster, as Taiwan escaped the financial turmoil relatively unscathed.

Against this backdrop, we found that Taiwan’s economic policy toward China before 1996 was truly market-conforming. The government did have some regulations on the trade with and investment in China, but none seemed to be outright contradictory with market forces then prevailing. But as 1996 went on, Taiwan’s economic policy toward China became more and more market-non-conforming, culminating in former President Lee’s call for “No Haste, Be Patient” (NHBP) toward Chinese market in September that year.

A chronicle of events in that year should be in order before our analysis. Taiwan held its first popular presidential election in March 1996. In the months leading to the election, China launched missiles into the water territories surrounding Taiwan, thus continuing tensions arising from Lee’s visit to Cornell University in the previous year. The tensions tapered off once Lee became elected. Lee was inaugurated in May and, following Taiwan’s political practice, he had to report to National Assembly (a symbolic, constitutional institution that presumably functions to hold the president accountable). It was in this highly symbolic setting, Lee, in August 1996, called for the Executive yuan to review its China-centered blueprint for

Asia-Pacific Regional Operation Center (APROC). Coming into being in January 1995, the APROC served as the cornerstone of Premier Lien Chan’s cabinet and general policy stance. The APROC, among other things, had in mind to use Chinese mainland as hinterland to develop Taiwan. Lee’s call for a review of the APROC was tantamount to sacking the idea of Taiwan-China development nexus. In September 1996, Lee, in a keynote speech to the National Association of Managers, urged the business community to adopt “NHBP” in decisions to invest in China. In October 1996, Lee addressed the 11th Meeting of the National Reunification Committee in these words,

“…To ensure the security and welfare of the twenty-one million fellowmen in Taiwan area is the bottom line of our survival and development. Therefore the starting point of our mainland policy must be to keep our roots in Taiwan, enhance construction, and strengthen our national power. We must show no haste, be patient, move steadily, and then go afar.”

This is in stark contrast with what Lee said in the 10th Meeting of the same committee in April 1995,

“In the face of global economic trends, Chinese must complement and benefit each other by sharing experiences. Taiwan’s economic development must make good use of China’s market. And China can learn from Taiwan’s experiences in economic development. With our trade with and investment in China, we can assist China in its way to economic prosperity.”

Harking back to events and political discourses in 1996 and beyond, we find two ideas behind the change in Taiwan’s economic policy toward China, one explicit, one implicit. The explicit idea is security concern, the implicit Taiwan’s nationalism. Concern with Taiwan’s security was obvious in Lee’s talks in occasions aforementioned. In its “Policy Background Statement on Investment in China” issued by the Ministry of Economic Affairs in June 1997, the MoEA mentioned “national security” or “threat from China” five times. The statement concludes with this remark: “[b]ased on principles of national security and economic development the Ministry must reasonably regulate Taiwan’s investment in China.” (MoEA, 1997) Other agencies, like Mainland

Affairs Council, also echoed this security concern in their relevant policy statements. Even after NHBP was replaced by current government’s “Active Opening, Effective Regulation” (AOER) policy regarding investment in China, the theme of security is still alive and well. In the “Policy Background Statement on AOER regarding Investment in China,” jointly issued on November 1991 by seven government agencies, terms like “economic security” or “economic strategy” are employed nine times to justify the new set of regulations (Mainland Affairs Council, et.al., 2001).

Taiwan’s nationalism can also account for the economic policy shift. Broadly speaking, nationalism or some other related cultural ideas could have strong impact on economic policy making (Johnson, 1967; Rohrlich, 1987; Shulman, 2000). Conversely, economic performance also bears upon the rise of nationalism (Helleiner, 1998; Crane, 1999). The mutual influence between nationalism and economic performance can be traced back to the nation-states’ pursuit of power and wealth since the seventeenth century (Viner, 1948). Taiwan nationalism can be observed in two ways: Lee’s expressions and the general trend in Taiwan identity. Lee had adroitly expressed Taiwan nationalism in terms of various political slogans and statements. Example abound (Lee, 1999):

--Taiwan as a “Common-Fate Community” (1993); --“Taiwan’s Sovereignty Belonging to the People” (1994);

--“The Sadness of Being a Native Taiwanese” in a published interview with Japanese writer Shima Ritaro (1994);

--“What the People Long for Is Always on My Mind,” speech title in Cornell University (1995);

--“New Taiwanese Principle” (1998); --“Special State-to-State Theory” (1998); --“Big Taiwan Nationalism” (1999).

Lee’s symbolic uses of language are exactly what Edelman calls “rhetorical evocations” (Edelman, 1971). Lee indeed has been instrumental in cultivating Taiwan nationalism.

It is not necessary for us to elaborate on the origin of Taiwan identity here. Suffice it to say that events since the 1895 Sino-Japanese War have formulated the collective memory and identity of Taiwanese (Chu and Lin, 2001). What is

interesting in the 1990s is that demographic groups (in terms of ethnicity, age, education, and gender) had all experienced an upward trend in Taiwan identity at the expense of Chinese identity. And it has been demonstrated that this trend toward Taiwan identity can best be attributed to periodic effects, that is, events in the 1990s caused the increase in Taiwan identity (Ho and Liu, 2002). Being diplomatically isolated, Taiwan has long prided itself on economic development and democracy. We therefore surmise that the rise of Taiwan nationalism was not just coincidental with Taiwan’s economic policy change toward China.

Institutions and Taiwan’s Economic Policy toward China

Scholars generally agree that Taiwan’s economic performance benefited from the political foundation provided by the KMT party-state (Wade, 1990; Chu, 1999). There were several components in this KMT-centered political foundation. First, by being the dominant party up until the year of 2000 when the KMT lost presidential election to the DPP, the KMT was powerful enough to draw a demarcation line between the state bureaucracy and the private interests. This means that the KMT was able to provide sufficient political protection for the bureaucracy to design and implement what it regarded as good industrial policies. Second, the KMT-controlled-state was able to control every major section of the financial sector: the public banks, private banks (Cheng,1993), local financial institutions (Ho and Lee, 1999), and a variety of finance companies. This control of finance, either through the regulatory regime or through the KMT party enterprises, gave the KMT tremendous leverage over the business community. Third, the state-business relationship is relatively flexible, which allowed for resilient adjustment capability (Hamilton, 1999).

Against this institutional background, Lee was at the peak of his power when he made the policy turnaround in the summer of 1996. Being elected with fifty-four percent of the total votes as the first native president in the first popular presidential election in Taiwan, Lee had garnered a high degree of legitimacy. His KMT party held an overwhelming majority in the Legislative

yuan, and the opposition DPP was basically Lee’s personal ally. He

re-appointed his vice president, Lien Chan, as the Premier, further bolstering his grip on the Executive yuan. With political power and institutions centered in his presidency, Lee bypassed all relevant agencies in making the policy announcements. Given the scope and direction of this policy change, Lee

never encountered much significant opposition from the bureaucracy, the legislature, the DPP, and even the business community. The reaction of the bureaucracy and the business community is worth mentioning. In the immediate wake of Lee’s call for reassessment of the APROC design, relevant agencies were scrambling to find words to insure the public that the APROC was really compatible with Lee’s new policy. On one occasion, Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) and the MoEA jointly stated that Taiwan’s economic relations with China should be on the conservative side. On the same day, a task force formed by the same two agencies sent their memo to the Executive

yuan arguing for more opening toward China so as to enhance Taiwan’s

competitiveness (United Daily, September 11, 1996, p.3). The MoEA didn’t issue its policy statement under the new policy until June 1997, some ten months after Lee fired the first policy-change salvo in August 1996. Several big businesses, including Tai Plastic and the President Enterprise, withdrew from the MoEA their applications for government approval for investment projects in China. Several top businessmen cautioned that government policy must be compatible with market forces lest many businesses will evade all government regulations—“to go underground,” only to no avail.

When DPP’s Chen assumed the presidential office in 2000, he could not afford the institutional luxury his predecessor enjoyed. Chen was elected by less than forty percent of the total votes. His party was vastly outnumbered in the legislature. The bureaucracy had never taken orders from a party that was not KMT. Chen definitely needed time to consolidate his power. By the time when Chen replaced the NHBP with his own “Active Opening, Effective Regulation” policy in September 2001, many had already invested into the Chinese market, disregarding government regulations. To many in the business community AOER is nothing more than a rationalization of fait

accompli, as it is a open secret that many investors could simply route their

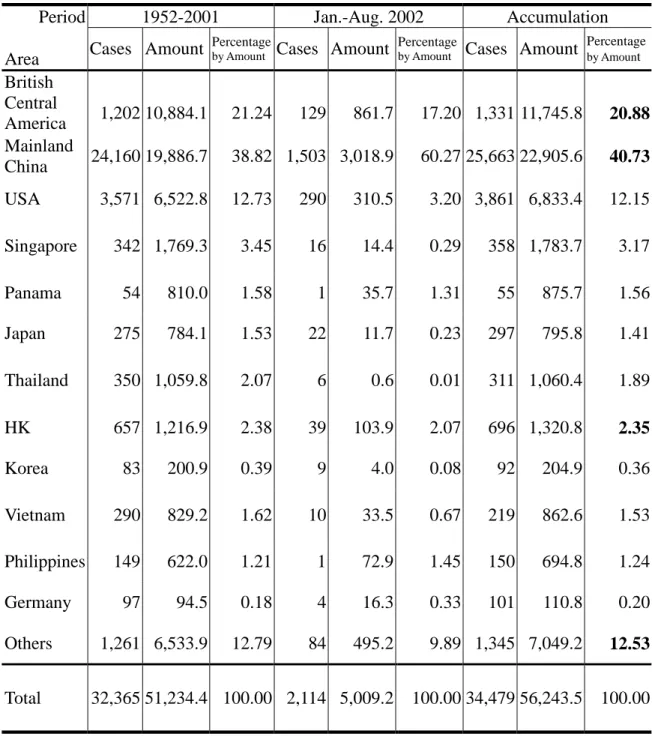

money to a third country, then transfer the fund to China. Table 1 bears this out.

Table 1 about here

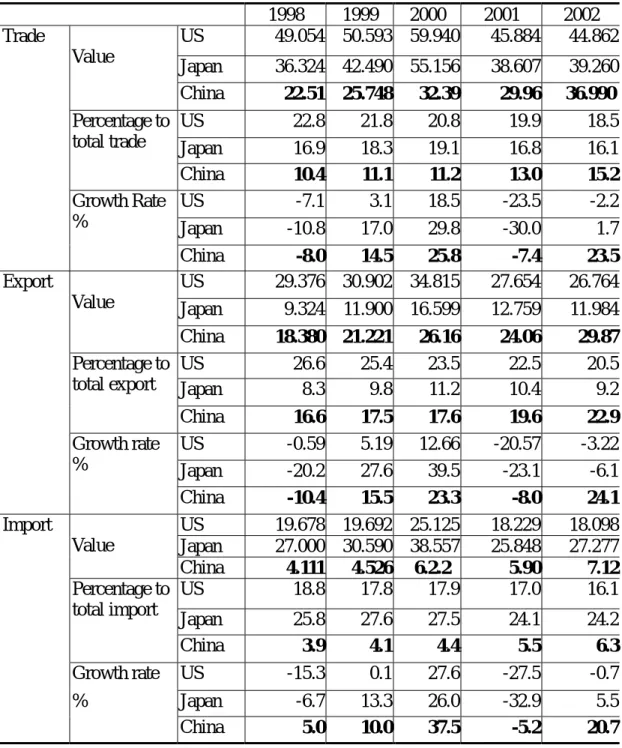

Despite the institutional distortion and political intervention, economic interaction between Taiwan and China continued to boom in the past decade. Cross-Straits economic relations are characterized by “civilian governance”. (Leng, 2003, p. 177; Leng, 2002b , p. 267 ) The private sector takes the lead. Table 2 demonstrates the general trend of cross-Straits trade relations in the past five years. Overall trade value continues to grow in an impressive rate. In 2002, China surpassed US and became the biggest market of Taiwanese exports. The 2002 data also shows that Taiwan's export to China constitutes more than one fifth of Taiwan's total exports, and enjoys 24.1% of growth from the previous year. In contrast, Taiwanese imports form China is minimum to Taiwan's total imports. Taiwan's trade surplus to China reached US$ 22.75 billion in 2002. In other words, Taiwan's international trade dynamics are boosted up by its trade surplus with China. Without such trade surplus, Taiwan's international trade will certainly be in deficit. In the past five years, Taiwan's economic dependence on China has evolved from an estimation to reality.

Table 2 about here

The huge Taiwanese exports to mainland China are driven by investment activities of Taiwanese business people. However, a huge gap exists between official estimation and real investment value to China. According to official statistics from Taiwan's Ministry of Economic Affairs released in July, 2002, the Taiwanese have invested 22.1 billion US dollars to China since 1992. The mainland Chinese authorities estimate that the "negotiated value" of Taiwanese investments reach US $59.9 billion (China Times, September 19, 2002). According Peng Huai-nan, Chairman of Central Bank of Taiwan, the accumulated Taiwanese investments to China in the past decade may be around US $104.5 billion (Central News Agency, March 18, 2002). Peng's estimation reconfirms the huge gap existing between official data and business activities across the Taiwan Straits. In other words, the real economic dynamics across the Taiwan Straits come from autonomous actions from the business community. Governmental interventions from Taiwan play only a marginal role in regulating this unique economic relationship.

The following pages will introduce the cases of semi-conductor industries, notebook PC production, and venture capital to demonstrate the gap between top-down incentives and bottom-up dynamics of cross-strait economic relations.

“Hybrid” Taiwanese Firms and Economic Statecraft

The semi-conductor production plays a key role in Taiwan's information technology industry that is closely linked with Taiwan's economic security. The long-delayed decision by the Taiwanese government to allow semi-conductor companies to invest in China was settled on April 2002 with the final decision being a compromise between the two national goals.

The pro-open globalists in Taiwan argue that the mainland initiatives should be regarded as one crucial step in Taiwan's globalization strategy vis-à-vis of IT development. Since the size of the Chinese market and the lower costs of production there enhance China's competitive advantages, the expansion of Taiwanese IT firms to China seems to be a rational choice as far as strengthening Taiwan’s competitiveness goes. There is little question that Chinese firms will learn or even "borrow" Taiwanese technology and know-how in IC production and design. To cope with such challenges from the mainland, Taiwan must upgrade its R & D capacities instead of isolating itself from the global division of labor. Furthermore, since Taiwan does not control the key technologies in the global supply chain, China may obtain know-how from the US, Japan and other advanced nations if it cannot be obtained from Taiwan firms. Once China establishes direct links with key component holders and excludes Taiwan's participation, Taiwan's strategy of globalization will, most assuredly, be put in jeopardy. At the current stage, the entry of the Taiwanese IC industry in the Chinese market will consolidate Taiwan's strategic role in global IC design and manufacturing.

The hard-core conservatives have made national security the first item of priority on the policy-making agenda. They claim that Taiwanese technology and know-how in silicon wafer manufacturing will be lost to China after the "cluster effects" are realized in major Chinese production centers. The "cluster effects" also refers to the moving out of the whole supply chain in the IT industry in general, and the silicon wafer production in particular. The mass movement of foundries to China will also cause serious unemployment problems in Taiwan. Given the fact that Taiwan does not control key technology in the production process, the cluster effect will facilitate the process for the Chinese to become the leading IC manufacturers in a short period of time. Once China becomes the dominant force in IC design and production, Taiwan's economy will be controlled and dependent on China, and Taiwan's national security will be in great danger. The "magnet attraction" of China will destroy Taiwan's grand strategy of globalization if Taiwan does not adopt balancing acts.

Adopting a principle of "positive opening, effective management", Taiwan's Cabinet announced four guidelines in governing semi-conductor industries:

wafer foundries on mainland China;

(2) The level of technology is limited to 8-inch wafers or bellow;

(3) Whoever invest in 8-inch wafers in mainland China must launch a new investment project on 12-inch wafers in Taiwan; and

(4) The production of key components and R & D capacities must be kept in Taiwan (China Times, March 9, 2002; United Daily News, April 25, 2002). The first case under review in the new regulative scheme was the application of TSMC to set up wafer foundries in Shanghai. After 10 months of bureaucratic deliberation, the Taiwanese government finally finished the "first stage" procedure of approval. Subsequent reviewing on other related details such as financial matters may take another six months. In the real world, however, IT producers such as TSMC cannot wait for such as long time for final approval. The Sunjiang township, the targeted location of TSMC's wafer foundry in Shanghai, had already made necessary arrangements for the arrival of TSMC well before the approval of the Taiwan side. Facing the cutting-throat competition in global wafer production, the Taiwanese wafer makers have no choice but to take early initiatives in the mainland market. The reason of early move is to "deter" domestic and foreign wafers for market shares by occupying a strategic position in China. Taiwanese IT companies have their own estimation and strategies to explore the mainland Chinese market. Waiting for the final approval from the Taiwanese government could only delay their business arrangements of global division of labor.

Furthermore, the new regulatory scheme fails to recognize the reality that Taiwanese wafer makers have transformed themselves into "hybrid" firms in China. In other words, the target of regulation on "Taiwanese firms" has become unclear. Founded in April 2000, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC, or Zhongxin), a US$1.46 billion worth of Taiwanese semiconductor company located in Shanghai’s Zhangjiang High-Tech Park, is a good example. Registered as an American company, SMIC is treated by the Chinese government as a leading indicator of domestic IC development. In addition to attracting human resources from leading Taiwanese semiconductor firms, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (TSMC) and United Microelectronics Corp (UMC) with which SMIC has a working relationship, SMIC’s major human resources come from overseas Chinese and returning mainland Chinese students trained abroad. SMIC has attracted at least seventy senior Taiwanese IC engineers from major US IT firms, such as Intel, AT&T, Motorola, Texas Instrument (TI), Hewlett-Packcard (HP) and Micron. SMIC's technical team consists of 2,500 talented IC designers and managers (Leng, 2002c, p. 246).

strict limitations with regard to talent and technology transformation to China, "hybrid" companies, such as SMIC, still have plenty of channels in which to grow. The Taiwanese IT firms are also clever in establishing international and local networks. Since SMIC is registered as an American company, many Taiwanese regulations governing cross-Strait investment are not applicable. To cope with the new Taiwanese laws regulating IT talent flows to China, SMIC plans to help Taiwanese engineers obtain passports from the third country (United Daily News, July 24, 2002). In the year 2002, SMIC reached agreements with Toshiba and Chartered Semi-Conductor Manufacturing (CSM) of Singapore to improve its production capacity and introduce advanced technologies. Toshiba will transfer its 8-inch foundry, while CSM will transfer its 0.18 micron technology to SMIC. In exchange, Toshiba and CSM is each expected to hold 5% of SMIC's stock (Commercial Times, September 24, 2002; United Daily News, July 24, 2002). At the current stage, the Taiwanese government only allows 0.25 micron technology to be transferred to China.

The case of the semi-conductor industry demonstrates that the “hybrid” type of IC firms play the role of integrating technology, know-how, and human resources in the global Chinese community. The ultimate goal of these global-oriented firms is to localize the human power and establish webs of state-business relationship in China. Companies like SMIC could not be classified as a pure “Taiwanese”, “Chinese”, or “American” firm. In the long run, strategies of localization will help sustain SMIC’s power base on mainland China while pursuing global goals of networking.

Multinational Corporations and Cross-Straits Economic Interaction

Another aspect of the failure of the Taiwanese state to regulate cross-Straits economic relations is the interactive efforts between Taiwanese firms and multi-national corporations. The operation of Taiwanese notebook PC producers provides a good example.

Taiwan's PC industry has developed an unique way to occupy a strategic place in the world market. Although almost unknown to PC consumers, the Taiwanese notebook PC producers, such as Quanta, has surpassed Toshiba as the world's No.1 notebook computer manufacturer in 2001. In the past decades, Quanta has evolved from a pure Original Equipment Manufacturing (OEM) vendor into a major ODM producer of the world's major PC brands. The Taiwanese notebook PC producers also develop an interdependent relationship with global name holders such as Dell, IBM, and Apple. In this unique patron--client relationship, multi-national IT firms still maintain flexibility in manipulating the balance.

international brand holders and Taiwanese notebook PC contractors. The Taiwanese state finds it difficult to regulate such joint efforts in the global division of labor. On the other hand, Taiwanese firms had already arrange their mainland projects well before being requested to do so by their ODM hosts. The Taiwanese government did not lift its restrictions on notebook PC investments to China until Nov 2001. In reality, most major Taiwanese manufacturers had already established their networks of up-stream suppliers of key parts one step ahead of governmental policies. In order to succeed, the complete supply chain must move with major contractors, hence creating clusters of Taiwanese notebook PC producers in mainland China.

The "mainland initiatives" on the part of Taiwanese PC manufacturers has created a new division of labor across the Taiwan Straits. This new type of business networking is dubbed as "Made in China, by Taiwan". In the past few years,

Taiwanese firms have made substantial contribution to China's global share of the IT market. In 2001, output from mainland factories occupied about 5.5% of Taiwanese notebook PC production, and the figure is expected to soar up to around 40% in 2002 (Xu, 2002.). At the current stage, the home bases of Taiwanese notebook PC firms are in charge of taking orders and performing R & D functions. Their production lines are being moved to China to reduce costs. To illustrate this, Compal maintains a work force of about 4,000 in Taiwan to tend to such matters as accounting and sales,

research and development and the one factory it still has there. Compal's notebook PC factory in suburban Shanghai has accelerated production capacity from 150 thousand to 250 thousand units per month this year. With the enhancement of productivity in China, Compal will make 60% of its notebooks in China. Compal also realizes its "China Direct Shipping, CDS" model and attempts to complete the production process within 24 hours (Cheng, 2002 , p. 104.). Quanta has also been building up its

Taiwan-based R& D team from 750 now to 2,000 by 2005 so that customers can outsource more of their design work to the Taiwanese ( Einhorn , 2001, p.79).

The new division of labor in the notebook PC sector benefits both sides of the Taiwan Straits. To retain its competitive advantage in the global networking, Taiwan needs to enhance its R & D caliber and global logistics capacities.

Global networking also strengthens Taiwan’s role in international division of labor in the notebook PC sector. Different from the OEM model of mass production in the traditional industry, Taiwanese ODM firms control key sectors of timely design and adaptation in the production process. These strategic advantages enhance Taiwan’s bargaining chips in allying with international brand-holders. The “made in China, by Taiwan” model of IT production demonstrates the complex interdependence between MNCs, Taiwanese ODM firms, and production centers in China.

The Loophole of Regulation? Venture Capital and Global Networking

Another emerging driver to boost cross-Straits economic relations is the active venture capitalists and their companies. This case also demonstrates that the global operation of VC is out of the reach of the Taiwanese state. In the past decade, Taiwanese VC has added fuel and helped create global networks for mainland Chinese and Taiwanese firms. Taiwanese professional managers have become fundamental pillars in the development of the Chinese market for international VC firms. The common practice of these firms is to register as an American or Hong Kong VC company and attract capital from the Greater China region and international sources. For instance, the Taiwan-based H & Q Asia Pacific is among the first foreign VC pioneers in China. With a total US$ 1.6 billion fund, H & Q Asia Pacific has invested more than $US 200 million in China. Major targets of investment include the two largest Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturers in Shanghai--Zhang Rujing's SMIC and Winston Wong's Grace Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp (GSMC). In the past ten years, H & Q has introduced American VC experiences as well as sophisticated, well-trained and gifted experts from Taiwan to mainland China. Not only capital but also human resources are undeniably the two necessary pillars of the scaffolding in the building of global networks of IT production.

The common characteristic of Taiwanese VC companies is in the globalization of their funding and management. In many cases, capital from mainland Chinese sources constitutes half of the total. In the global visions of such VC firms, one criterion for selecting Taiwanese start-up investment projects is their potential to expand and prosper in China. At the same time, these Taiwanese VC firms have established branches in major Chinese cities and trained first-generation VC managers there. American venture capitalists are becoming bridges to link Taiwanese and Chinese companies. Warburg Pincus, an American VC company, has established strategic alliances with Taiwanese venture capitalists to develop the Chinese market. One crucial goal of Warburg Pincus is to help to promote the cooperation among high-tech firms across the Taiwan Strait.

Taiwanese VC investment could closely link up with China’s drives for globalization and capital-market reform. In the initial stage, China’s VC companies were organized by local governments, but these companies, for the most part, lacked professional personnel and marketing capacity. Recently China has begun to acknowledge the importance of attracting foreign VC to link Chinese start-up companies with international talent, sales routes, and capital markets (People’s Daily, December 30, 2000), and as a consequence, state-backed VC firms are being restructured like those in the West in order to compete in the market. For one,

Shanghai Venture Capital Corporation (SVCC), a Shanghai city-owned VC firm, enjoys considerable autonomy in operating in accordance with market mechanisms, and SVCC has begun establishing strategic links with other Chinese VC firms, such as Shanghai New Margin Venture Capital (SNMVC), controlled by Chinese President Jiang Zemin’s son, Jiang Mianheng. The complex networking with local and international technology centers gives Taiwan a unique advantage to compete with other Asian nations in the VC market in China (Leng, 2002a, p. 243) .

Taiwanese VC companies also play an important role of helping to enhance state-business relationships across the Taiwan Straits. In the case of GSMC, the alliance between Winston Wong, son of the Taiwanese tycoon Wang Yung-ching, and Jiang Mianheng demonstrates the foundation of GSMC's political networks in China. GSMC has, in the meantime, also succeeded in attracting supports from Crimson Asian Capital and Crimson Velocity, both of which belong to the Crimson Fund. Founder of Crimson Fund Gu Zhongliang is the son of Gu Liansong, head of Taiwan's prestigious China Trust Group. In addition to introducing global networks of manufacturing and management, Taiwanese VCs help strengthen local networks of relationships. In the era of globalization, this "localization" of networks is still the key of success in China.

Given the fact stated above, the Taiwanese state lacks effective instruments to regulate or even punish "illegal" Taiwanese VC activities on China. The only substantial instrument is to prohibit governmental development funds from investing on mainland China-oriented VCs. In late 2002 and early 2003, the Taiwanese government forced two Taiwanese VC with governmental funds shares to withdraw new projects from GSMC and SMIC in Shanghai. For those who attract funds from international sources, the state can only use indirect ways or resort to moral principles to persuade them.

Just like the case of semi-conductor and notebook PC companies, the major problem of Taiwan's regulatory scheme is the difficulty in defining the target. In addition to their capacities in attracting global funds, Taiwanese venture capitalists endeavor to localize their operation and establish complex state-business networking in China. The real ‘target’ for regulation should be the momentum and long-term ambition of these venture capitalists in utilizing the mainland Chinese market as the power house of global operation. Such activities combining strategies of globalization and localization are not constrained by the governmental intervention, especially regulations from the investors’ home country. Actions by the Taiwanese state to punish illegal venture capital activities only serve as a symbol to demonstrate the willingness of the government to balance national security and economic benefits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we find that the ideas behind Taiwan’s economic policy toward

China are as vibrant as ever, the political foundation for a coherent and feasible policy is eroding, and commercial interests are digressing from Taiwan government’s policy goals. This picture, however, is far from being complete. To further understand Taiwan’s economic policy toward China, we may want to probe:

First, ideas’ role in policy-forming stage. The economic historian Trentmann, in observing the idea of free trade in its inceptive stage in the late Victorian and Edwardian era, has this to say, “…free trade can conceptualized as a convergence of ideas about liberal politics and society sufficient to generate collective allegiance and

action” (Trentmann, 1998, p.235, italic not original). That is, whether free trade is

true or false isn’t really the point. The point is that idea can serve as a rally point where political forces would converge and interact. Almost daily, one can observe Taiwan’s political discourses surrounding on identity, on Taiwan Independence, on “love for Taiwan,” and so on. These ideas, or more precisely, the political forces around these ideas, have strong bearing on the formation of Taiwan’s economic policy toward China. The Taiwan Solidarity Union’s (a political party formed by Lee after he was expelled from the KMT) vehement opposition to DPP government’s decision to open 8-inch wafer investment is a case in point.

Secondly, the truthfulness or falseness of the “security” argument in Taiwan’s economic policy toward China. The security argument was always couched in Hirschmanian terms (Hirschman, 1945), even though we now know that Hirschman’s argument may have to be qualified in important ways (Ritschl, 2001). But being so intuitively true, the security argument is by and large taken at its face value. Indeed, we are yet to see much meaningful debate regarding the security argument. The truthfulness or falseness of the “security” argument is of intrinsic value to Taiwan’s decision-makers, as they have to take ultimate responsibility for the strategic-political implications of economic relations with China.

Thirdly, the “boomerang” effect on Taiwan’s domestic politics of economic relations with China. Whether in the realms of trade and investment, we need better specify how trade (and investment in) with China influences Taiwan’s distribution, and, hence, its politics. Taiwan-specific studies along the lines suggested by scholars like Rogowski or Frieden are far and between (Rogowski, 1989; Frieden,

1991).

Finally, we need to better understand the high politics involved in making economic policy toward China. The relative position of relevant agencies in this policy realm, in our views, is of particular importance. We therefore call for more studies in this aspect.

Table 1. Taiwan’s Approved Outward Investment by Country (Area)

Unit: US$ million, %Period 1952-2001 Jan.-Aug. 2002 Accumulation

Area Cases Amount

Percentage

by Amount Cases Amount

Percentage

by Amount Cases Amount

Percentage by Amount British Central America 1,20210,884.1 21.24 129 861.7 17.20 1,331 11,745.8 20.88 Mainland China 24,160 19,886.7 38.82 1,503 3,018.9 60.27 25,663 22,905.6 40.73 USA 3,571 6,522.8 12.73 290 310.5 3.20 3,861 6,833.4 12.15 Singapore 342 1,769.3 3.45 16 14.4 0.29 358 1,783.7 3.17 Panama 54 810.0 1.58 1 35.7 1.31 55 875.7 1.56 Japan 275 784.1 1.53 22 11.7 0.23 297 795.8 1.41 Thailand 350 1,059.8 2.07 6 0.6 0.01 311 1,060.4 1.89 HK 657 1,216.9 2.38 39 103.9 2.07 696 1,320.8 2.35 Korea 83 200.9 0.39 9 4.0 0.08 92 204.9 0.36 Vietnam 290 829.2 1.62 10 33.5 0.67 219 862.6 1.53 Philippines 149 622.0 1.21 1 72.9 1.45 150 694.8 1.24 Germany 97 94.5 0.18 4 16.3 0.33 101 110.8 0.20 Others 1,261 6,533.9 12.79 84 495.2 9.89 1,345 7,049.2 12.53 Total 32,365 51,234.4 100.00 2,114 5,009.2 100.00 34,479 56,243.5 100.00

Source: Cross-Straits Economic Statistics Monthly, Mainland Affairs Council, Taipei, August, 2002, p. 29

Table 2. Taiwan's Foreign Trade with China, US and Japan

Unit: US$ billion;%1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 US 49.054 50.593 59.940 45.884 44.862 Japan 36.324 42.490 55.156 38.607 39.260 Value China 22.51 25.748 32.39 29.96 36.990 US 22.8 21.8 20.8 19.9 18.5 Japan 16.9 18.3 19.1 16.8 16.1 Percentage to total trade China 10.4 11.1 11.2 13.0 15.2 US -7.1 3.1 18.5 -23.5 -2.2 Japan -10.8 17.0 29.8 -30.0 1.7 Trade Growth Rate % China -8.0 14.5 25.8 -7.4 23.5 US 29.376 30.902 34.815 27.654 26.764 Japan 9.324 11.900 16.599 12.759 11.984 Value China 18.380 21.221 26.16 24.06 29.87 US 26.6 25.4 23.5 22.5 20.5 Japan 8.3 9.8 11.2 10.4 9.2 Percentage to total export China 16.6 17.5 17.6 19.6 22.9 US -0.59 5.19 12.66 -20.57 -3.22 Japan -20.2 27.6 39.5 -23.1 -6.1 Export Growth rate % China -10.4 15.5 23.3 -8.0 24.1 US 19.678 19.692 25.125 18.229 18.098 Japan 27.000 30.590 38.557 25.848 27.277 Value China 4.111 4.526 6.2.2 5.90 7.12 US 18.8 17.8 17.9 17.0 16.1 Japan 25.8 27.6 27.5 24.1 24.2 Percentage to total import China 3.9 4.1 4.4 5.5 6.3 Growth rate US -15.3 0.1 27.6 -27.5 -0.7 Japan -6.7 13.3 26.0 -32.9 5.5 Import % China 5.0 10.0 37.5 -5.2 20.7 Sources:http://www.mof.gov.tw/statistic/trade/2301.htm; http://www.mof.gov.tw/statistic/trade/2311.htm; http://cus.trade.gov.tw/cgi-bin/pbisa60.dll/customs/uo_base/of_start; http://www.moea.gov.tw/~ecobook/eco/9201eco.doc;

References

Cheng, Tun-jen. 1993. “Guarding the Commanding Heights: The State as Banker in Taiwan.” In Stephan Haggard, Chung H. Lee, and Sylvia Maxfield, eds., The Politics

of Finance in Developing Countries. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Cheng Zhangyu, "Chen Ruicong yao renbao na diyi" (Chen Ruicong Urges Compal becomes No. 1), Global View Maganize, May 1, 2002,

China Times. 2003. April 3, p.2.

China Times, September 19, 2002.

Central News Agency, March 18, 2002.

China Times, March 9, 2002;

Chu, Yun-han. 1999. “Surviving the East Asian Financial Storm: The Political Foundation of Taiwan’s Economic Resilience.” In T.J. Pempel, ed., The Politics

of the Asian Economic Crisis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Chu, Yun-han, and Jih-wen Lin. 2001. “Political Development in 20th-Century Taiwan: State-Building, Regime Transformation and the Construction of National Identity.” China Quarterly 165: 102-129.

Commercial Times, September 24, 2002; United Daily News, July 24, 2002.

Crane, George T. 1999. “Imaging the Economic Nation: Globalization in China.” New Political Economy 4:2, pp.215-232.

Edelman, Murray. 1971. Politics as Symbolic Action: Mass Arousal and

Quienscence. New York: Academic Press.

Einhorn , Bruce, "Quanta's Quantum Leap", Business Week, November 5, 2001, p.79.

Frieden, Jeffry A. 1991. “Invested Interests: The Politics of National Economic Policies in a World of Global Finance.” International Organization 45, pp. 425-451.

Hamilton, Gary G. 1999. “Organization and Market Processes in Taiwan’s Capitalist Economy.” In Marco Orru, Nicole Woolsey Biggart, and Gary G. Hamilton, eds. The Economic Organization of East Asian Capitalism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Helleiner, Eric. 1998. “National Currencies and National Identies.” American

Behavioral Scientist 41:10, pp.1409-1436.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1945. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Ho, Szu-yin, and Lee Jih-chu. 2001. “The Political Economy of Local Banking in Taiwan.” Issues & Studies 37:4, pp. 69-89.

Ho, Szu-yin, and I-chou Liu. 2002. “The Taiwanese/Chinese Identity of the Taiwan People in the 1990s.” The American Asian Review 20:2, pp.29-74.

Johnson, Harry G. 1967. Economic Nationalism in Old and New States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, Teng-huei. 1999. Taiwan’s Assertions (Taiwan de ju chang). Taipei, Taiwan: Yuan-liu Publisher.

Leng, Tse-Kang , 2003. "Sovereignty at Bay? Business Networking and Domestic Politics of Informal Integration between Taiwan and Mainland China". In Philip Regnier and Fu-Kuo Liu ed. Regionalism in East Asia:

Paradigm Shifting?. London: Curzon/Routldege. Chapter 10, pp. 176-196.

Leng, Tse-Kang, March/April, 2002a. "Economic Globalization and IT Talent Flows : The Taipei/Shanghai/Silicon Valley Triangle". Asian Survey, 42:2, pp. 230-250.

Leng, Tse-Kang, April, 2002b. "Securing Cross-Straits Economic Relations: New Challenges and Opportunities". Journal of Contemporary China. , 11: 31, pp. 261-279.

Leng, Tse-Kang ,2002c Zixun Chanye Quanqiuhua de Zhengzhi Fenxi : Yi Shanghai

Shi Fazhan Weili(A Political Analysis of Information Technology Industries: Shanghai in Global Perspective) Taipei: Ink.

Li Kun, “Fengxian touzi ye xuyao liyong waizi (Venture capital also needs foreign investment), People’s Daily, overseas edition, December 30, 2000.

Mainland Affairs Council, et.al. Executive yuan, Taiwan. 2001. Policy Background Statement on AOER regarding Investment in China.

Ministry of Economic Affairs, Executive yuan, Taiwan. 1997. Policy Background Statement on Investment in China.

Ritschl, A.O. 2001. “Nazi Economic Imperialism and the Exploitation of the Small: Evidence from Germany’s Secret Foreign Exchange Balances, 1938-1940.” The

Economic History Review 56:2, pp.324-345.

Rohrlich, Paul Egon. 1987. “Economic Culture and Foreign Policy: the Cognitive Analysis of Economic Policy Making.” International Organization 41:1, pp.61-92.

Rogowski, Ronald. 1989. Commerce and Coalitions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shulman, Stephen. 2000. “Nationalist Sources of International Economic Integration.” International Studies Quarterly 44:3, pp.365-390.

Trentmann, Frank. 1998. “Political Culture and Political Economy: Interest, Ideology, and Free Trade.” Review of International Political Economy 5:2. pp.217-251.

United Daily News , September 11, 1996. United Daily News, April 25, 2002.

United Daily News, July 24, 2002.

Viner, Jacob. 1948. “Power versus Plenty as Objectives of Foreign Policy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries.” World Politics 1, pp.1-29.

Wade, Robert. 1990. Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of

Government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton

World Bank. 1993. “The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy.” New York, NY: Published for the World Bank (by) Oxford University Press.

Xu Jiahui, "Taiwan Jianchan, Dalu Liangchan" (Decreasing production in Taiwan, increasing outputs in mainland China", Global View Magazine, November 16, 2002.