國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

構式與詞彙語意之互動:

以框架理論為本之漢語多義詞「帶」的研究

A Frame-based Lexical Constructional Study of the

Polysemic Verb Dài in Mandarin Chinese

研究生:胡韵庭

指導教授:劉美君教授

構式與詞彙語意之互動:

以框架理論為本之漢語多義詞「帶」的研究

A Frame-based Lexical Constructional Study of the Polysemic Verb Dài in Mandarin

Chinese

研究生:胡韵庭

Student: Yun-Ting Hu

指導教授:劉美君教授

Advisor: Meichun Liu

國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

College of Humanity and Social Science

National Chiao Tung University

in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Arts

June 2014

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

中華民國一百零三年六月

構式與詞彙語意之互動: 以框架理論為本之漢語多義詞「帶」的研究 研究生:胡韵庭 指導教授:劉美君教授 外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

摘要

本研究以框架語意學為本,試圖從構式以及詞彙語意之互動探討漢語多義動 詞「帶」其多種語意內涵之關聯。據觀察,漢語「帶」涵蓋九種語意內涵,藉由 結合框架語意之理論與構式語法,本文欲探索「帶」所隱含之多個詞意在其相對 應之語法呈現上其語意與語法互動連結關係。本研究提出「帶」的原型事件,即 核 心 語 意 為 表 達 一 個 致 使 移 動 事 件 (caused-motion event) 。 以 此 原 型 事 件 (prototype) 為 語 意 概 念 基 模 (semantic base) , 本 文 提 出 藉 由 不 同 的 語 意 側 重 (semantic profile)成分輔以框架語意及構詞語法之互動呈現,他動動詞「帶」可 投射出不同之語意內涵。本研究指出「帶」的原型語意為表達一個共移(co-motion) 事件,即主事者和受事者於事件中皆共同移動至某個空間處所並執行某目的性事 件(如:學生帶錢到學校繳註冊費)。透過認知轉換,本文分析「帶」所表之共移 語意亦可側重於主事者與受試者之共行(co-action)事件,亦即主事者帶受事者共 同執行某個活動,表一帶領事件。(如:我帶他環遊世界)。此外,共移事件亦可 側重於表達主事者與受試者之共存狀態(co-existence),視為共移事件的結果,表 一個攜帶事件(如:她身上帶著護照)。以致使移動事件及其所隱含之「帶領」及 「攜帶」的語意面向出發,本文提出「帶」將藉由不同語意框架下參與者角色之 語意延伸或語意面向之側重延展至多個非核心語意,其中包含「帶」(to bring to) 延伸至「接」(to pick up)、「照顧」(to take care of) 、「帶動」、(to activate)「佩帶」 (to wear) 、「帶有」(to be with) 、「呈現」 (to appear with)之語意內涵。本研究 著眼於詞彙之框架語意與構式之互動並佐以語料之證明,為漢語多義詞「帶」所 展現之多個語意面向提出一套有系統性的框架語意分類及語意連結分析,並且於 語言學上語意及語法之互動呈現、詞彙與構式之關聯甚至於認知與語言之互動關 係提供一良好的案例證明。 關鍵詞: 漢語 「帶」 字, 框架語意學, 詞彙語意學, 多義詞, 漢語攜帶類動詞, 語意投射A Frame-based Lexical Constructional Study of the Polysemic Verb Dài in Mandarin Chinese

Student: Yunting Hu Advisor: Meichun Liu

Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

The present study probes into the polysemic nature of the verb dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Mandarin, in which dài 帶 ‘bring’ is found to bear at least nine meaning imports. Integrating Frame Semantic (Fillmore and Atkins 1992) and Construction Grammar (Goldberg 1995, 2010), this study aims to explore the semantic-to-syntactic correlations between the different senses underlining the syntactic realizations of dài 帶 ‘bring’. It is argued that dài 帶 ‘bring’ may profile different semantic scopes from the semantic base: dài 帶 ‘bring’ as a caused-motion verb, with distinct frame-specific roles and morphosyntactic realizations. The basic sense of the caused-motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ depicts a co-motion event in which an agent Mover takes a Co-Movee to undergo a locational change (e.g., xuésheng dài qián dào xuéxiào jiǎo zhùcèfèi 學生帶錢到學校繳註冊費 ‘Students bring the money to the school to pay for the registration fee.’). Nevertheless, due to conceptual transfers, dài 帶 ‘bring’ may be used to profile a dynamic co-action event in leading and initiating an activity (e.g., wǒ

dài tā huán yóu shìjiè 我帶他環遊世界 ‘I took him to travel around the world.’) and

further extended to profile the stative co-existence relation without movement (e.g., tā

shēnshàng dài zhe hùzhào 她身上帶著護照 ‘He brought the passport with him.’).

Based on these three semantic domains, it is postulated that other non-central senses of

dài 帶 ‘bring’ are derived either when the prototypical cases of semantic roles are

mapped unto different semantic relations or when the event highlights a specific semantic attribute. The analysis proposed in this study is substantiated with a detailed corpus analysis of colloconstructional variations. It follows the frame-based lexical constructional approach in delimiting semantically salient features pertaining to lexical frames with a constructional account that captures the form-meaning mapping correlations. The study provides a clear case study that demonstrates the close interaction between semantics and syntax, lexicon and construction and ultimately, cognition and language.

Key words: Mandarin dài 帶, Frame Semantics, Lexical Semantics, polysemic verb, ‘bring’ verb in Mandarin, semantic profiling

誌謝 時光飛逝,轉眼間研究所生涯已進入尾聲。在這執筆寫下誌謝文的一刻,內 心依舊是激動不已,已不知研究所的一切點點滴滴該從何開始訴說,卻也滿心期 待著人生的下一個旅途的來臨。猶想二年半前對於研究所的一切還懵懵懂懂的我, 對於即將踏進陌生的環境並且面對無數未知的挑戰,是如此徬徨,然而今日,我 卻已經是一位能夠獨當一面、成熟穩重,即將邁入社會的新鮮人。在這研究所求 學的階段,我珍惜我所經歷的一切,我也感謝每一位我遇見的人! 首先,我最感謝的人是我的指導教授劉美君老師,謝謝老師在我學習的過程 中,悉心的給予我指導,在學習的過程中,總是給予我明確的方向,突破我研究 上所遭遇的盲點與困惑,並且在最後論文修改的階段,不吝犧牲許多時間幫我修 改論文。跟著老師的研究團隊一路學習,學到的不只是研究,而是思考;且不僅 是學術,更有待人處事的多方領悟。謝謝老師這一路的領導與指教,也謝謝老師 在課外之餘對我們的照顧,讓第一次離鄉求學的我也能感受到家的溫暖! 另外,我也要謝謝曾經教導我音韻學的許慧娟老師、句法學劉辰生老師、語 意學林若望老師以及語音學潘荷仙老師,您們的專業教學讓我在學習語言學各科 目能夠有很好的見識與掌握,能夠在席下聽您們的講課很榮幸也很享受! 此外,我也要特別感謝美君老師研究團隊的每一位成員,謝謝曾經在研究上 幫助過我的學長姐,佳音、睿良、書平、忠豪、孝勇、幸珊、俞汶和瑋芩,特別 謝謝睿良曾細心的給予我 tagging 的指教,也謝謝書平和忠豪總是能為我分擔研 究及行政上許多事,並且不厭其煩聽我訴說和解決我在團隊遭遇的困難與煩惱。 在此我也要感謝我的同窗夥伴懿方總是那麼支持我、鼓勵我,雖然你讓我扛了很 多事,但你每一分感謝我都銘記在心。我的同窗好姊妹宛儀,謝謝妳研究所一路 的陪伴,不管是在生活上還是研究上,因為有妳,讓在這看似乏味的研究所生活 多了好多花漾的色彩,讓我不孤單。另外也要謝謝學弟妹睿敬、哲瑋和宛潔曾在 研究上給予我建議與指教。最後,我要謝謝美君老師所帶領的整個團隊給了我許 多磨練成長的機會,在這個團隊學習及生活的點點滴滴、歡笑與淚水,每一位成 員都將是我研究所階段最值得記憶的片段。 我也要感謝我的研究所同學,霈宸、靜汶和紹任,學妹懿萱和珮儀,室友麗 君,一同就讀研究所的大學好友雨歆和筱純,及貼心好友一鳴、薇如、之之等太 多人這一路上的支持與鼓勵,也謝謝你們這一路上不時還要聽我發牢騷小抱怨, 分享我的心情,太多的感謝說不完,只好跟你們說一句,我愛你們! 最後,我誠摯的感謝我的家人,一路支持我完成我的學業,謝謝爸媽培養我 成為一個勇於追求挑戰的人,也謝謝愛欺負我又很保護我的哥哥一路虧我到現在, 讓我成為更堅強的人,你們的愛與支持永遠都是我最堅強的後盾,我愛你們! 我願將此份論文完成的喜悅,分享給曾經幫助過我的人。 我,期許,帶著這個階段的種種歷練,迎接下一段旅程。

Table of Contents

摘要... i Abstract ... ii Table of Contents ... iv List of Table ... vi List of Figure ... vi Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 11.2 Issue: The Polysemy of dài 帶 ‘bring’... 2

1.3 Scope and Goal ... 6

1.4 Organization of the Thesis ... 7

Chapter 2 Literature Review ... 9

2.1 Previous Works on Caused-motion Events ... 9

2.1.1 The Lexicalization Patterns of Motion ... 9

2.1.2 The Prototypical Caused-motion Event ... 11

2.1.3 Constructional Analysis of Caused Motion ... 13

2.1.4 Proto-Motion Event in Mandarin Chinese ... 15

2.2 Previous Works on English Verbs Bring and Carry ... 17

2.2.1 Levin (1993): Verbs of Sending and Carrying ... 17

2.2.2 Fillmore and Atkins (1992): FrameNet ... 19

2.3 Summary ... 22

Chapter 3 Database, Theoretical Frameworks, and Methodology... 23

3.1 Database ... 23

3.2 Theoretical Frameworks ... 23

3.2.1 Frame-based Lexical Constructional Approach ... 24

3.2.3 The Prototypical Category Theory and Semantic Profile ... 25

3.3 Methodology ... 26

Chapter 4 Findings ... 29

4.1 Distributional Frequency of Multi-Faceted dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 29

4.2 Semantic Distinctions of dài 帶 ‘bring’: Caused-Motion vs. Non-Motional Use ... 34

4.2.1 Dài 帶 ‘bring’ as a Caused-Motion Verb: Bring to ... 35 4.2.2 Dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Non-Motion Uses: Lead (dàiling 帶領) vs. Bring with

(xīdài 攜帶) ... 42

4.2.3 Interim Summary ... 52

4.3 Collocation Patterns ... 52

4.3.1 Collocation Patterns of Caused-motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 52

4.3.2 Collocation Patterns of Non-motional Uses of Dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 55

Chapter 5 Semantic Analysis on the Polysemic Dài 帶 ‘Bring’ ... 59

5.1 The Semantic Base: the Prototype of Caused-motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 59

5.1.1 The Conceptual Schema of Caused-motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 60

5.2 The Semantic Profiles: the Subtypes of dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 62

5.2.1 The Subtype 1: the Sense of Lead (dàiling 帶領) ... 63

5.2.2 The Subtype 2: the Sense of Bring with (xīdài 攜帶) ... 70

5.3 Semantic Extensions of the Prototype and Subtypes of dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 74

5.3.1 Sense Extension of Caused-motion Bring to ... 75

5.3.2 Sense Extensions of Lead ... 78

5.3.3 Sense Extensions of Bring with ... 82

5.4 The Interrelationship of the Multi-faceted Meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 88

5.5 Framed-based Analysis of Caused-motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 89

5.5.1 Conceptual Schema of Caused-motion Archiframe ... 90

5.5.2 The Hierarchical Structure of the Frame ... 92

5.5.3 Overviews of the Frame ... 102

5.6 Summary ... 105 Chapter 6 Conclusion ... 106 6.1 Conclusion ... 106 6.2 Future Research ... 108 References ... 109 Website Resources ... 112

List of Table

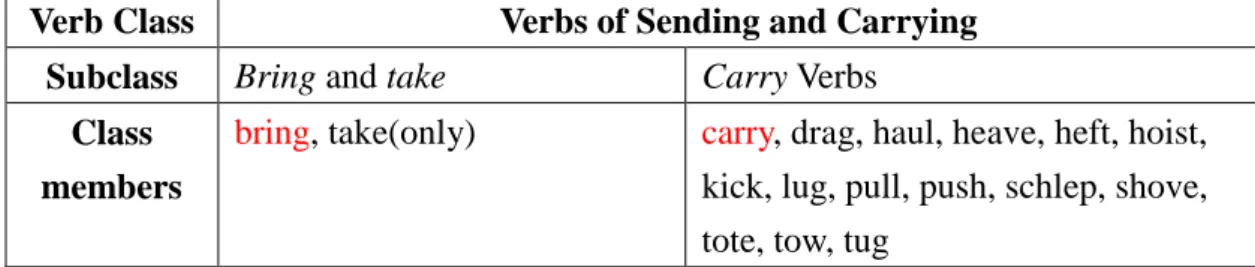

Table 1. Senses of dài 帶‘bring’ in Chinese WordNet ... 3

Table 2. Verbs of Sending and Carrying in Levin (1993) ... 18

Table 3. English Equivalent Lexical Units of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in FrameNet ... 21

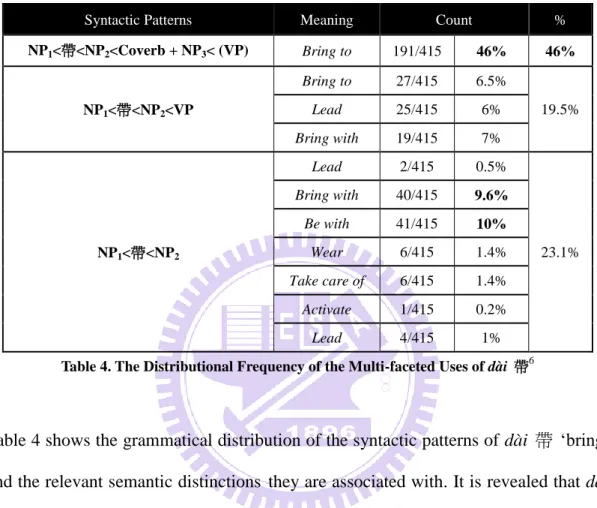

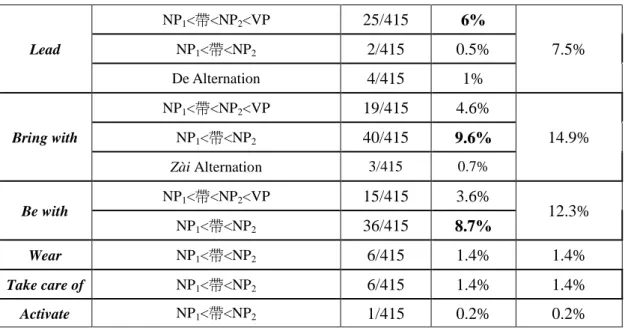

Table 4. The Distributional Frequency of the Multi-faceted Uses of dài 帶 ... 32

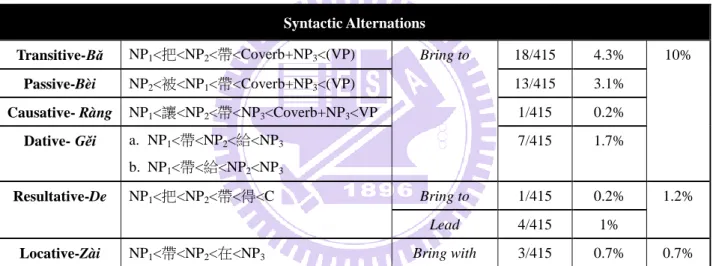

Table 5. The Distributional Frequency of the Multi-faceted Uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ with Respect to Syntactic Alternations ... 33

Table 6. The Distributional Frequency of the Meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ with Respect to the Syntactic Patterns ... 34

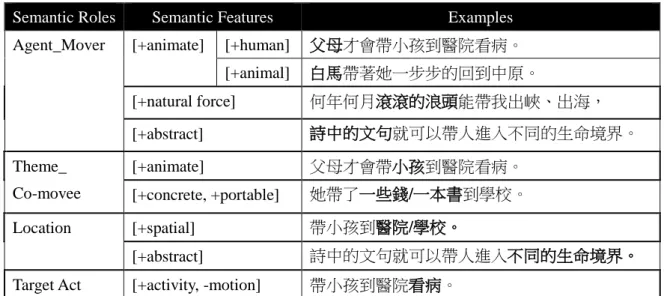

Table 7. The Semantic Features of the Participant Roles of Caused-Motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 42

Table 8. The Semantic Features of the Participant Roles of Leading dài 帶 ‘bring’ . 47 Table 9. The Prototypical Semantic Features of the Participant Roles of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Bring with ... 50

Table 10. The Non-Prototypical Semantic Features of the Participant Roles of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Bring with ... 51

Table 11. The Semantic Features of the Participant Roles of the Extended Senses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 51

Table 12. Overview of the Caused Motion Frame ... 104

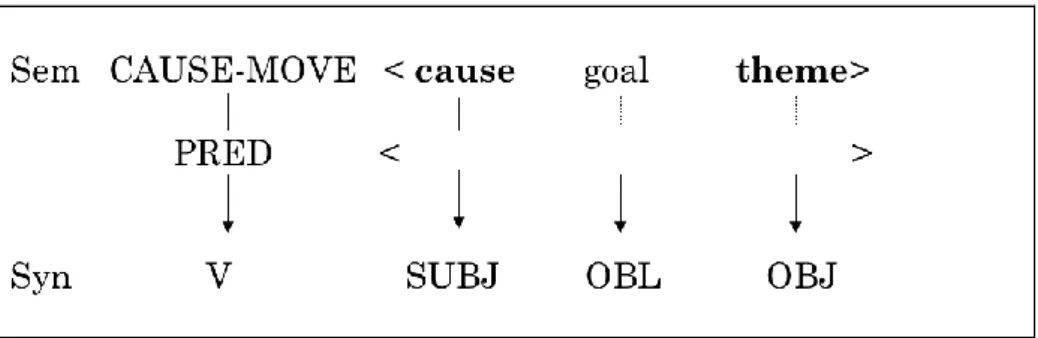

List of Figure Figure 1. English Caused-motion Construction ... 13

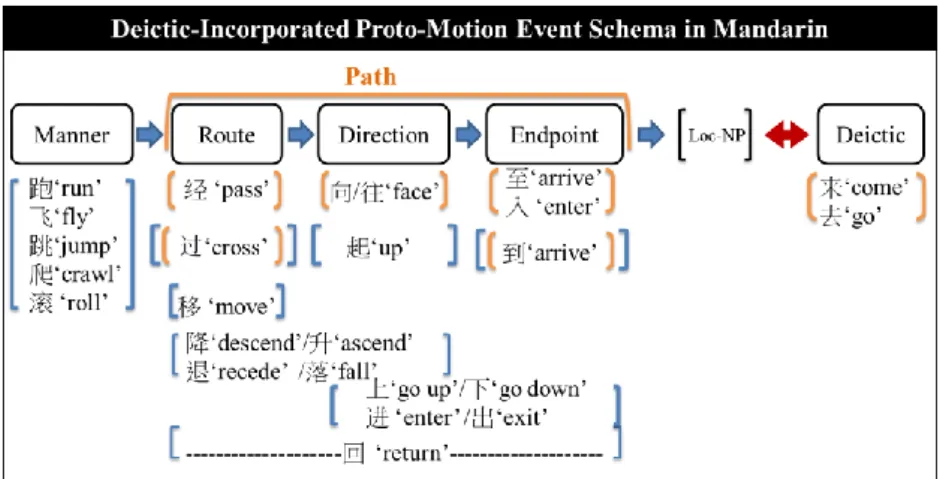

Figure 2. The Deictic-incorporated Proto-Motion Event Schema ... 16

Figure 3. The Prototype Conceptual Schema for Caused-motion dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 60

Figure 4. The Conceptual Schema for Leading dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 63

Figure 5. The Conceptual Schema for Leading dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Relation to Bring to ... 65

Figure 7. The Conceptual Schema for dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Sense of Bring with ... 71

Figure 8. The Conceptual Schema of Bring with in Relation to Bring to ... 73

Figure 9. Conceptual Subschema of Caused-motion Picking up Event ... 76

Figure 10. The Hierarchical Structure of the Interrelationships of the Multi-faceted Meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ ... 89

Figure 11. Conceptual Schema for Caused Motion ... 92

Figure 12. The Hierarchical Structure of Caused Motion Frames ... 93

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Background

Studies of verbal semantics have long been a widely discussed issue in linguistic research. A number of studies on lexicalization, semantic categorization, and semantic-to-syntactic correlation based on verbal meanings have been substantially investigated and proposed (Levin 1992, Fillmore 1982, Fillmore and Atkins 1995, Goldberg 1995, 2010, Liu 2002). With the view that the meaning of a verb may crucially determine its syntactic behavior, Levin (1992) classifies English verbs based on their shared meanings and a wide range of syntactic patterns and alternations. Fillmore and Atkins (1992) propose Frame Semantics noting that the meaning of a verb cannot be understood without the essential knowledge of the real world; that is, “meaning is relativized to frames.” Goldberg (1995) offers a constructional account of the argument structures of verbs, in which the verb meaning is related to the constructional meaning. Liu (2002) investigates the verbal semantics of Mandarin near-synonyms with a corpus-based approach and proposes that verbal semantics is correlated and realized in a verb’s syntactic behavior. These previous studies have set a solid foundation for the study of verbal semantics. However, verbs with multiple meanings; that is, cross-categorical polysemous verbs in Mandarin, have not yet been widely discussed within the above frameworks. As an attempt to further explore the verbal semantics of Mandarin verbs, this study aims at exploring the polysemous verb

dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Mandarin in the views of Frame Semantics (Fillmore and Atkins

1.2 Issue: The Polysemy of dài 帶 ‘bring’

Mandarin verb dài 帶 ‘bring’ is a typical transitive and caused-motion verb that manifests multiple meaning facets. According to the online lexical database Chinese WordNet1, dài 帶 ‘bring’ as a transitive verb is identified with 24 senses which are represented by precise expressions of senses and sense relations, as listed below:

1 Chinese WordNet is conducted by Academia Sinica to serve as a large-scale semantic lexical database for Chinese which embodies a precise expression of sense and sense relations (Huang et al., 2008b). The information of the lexical entry analyzed in this database contain Part of Speech, sense definition, example sentences, corresponding English synset(s) from PrincetonWordNet, lexical semantic relations and so on that are theoretically based on lexical semantics.

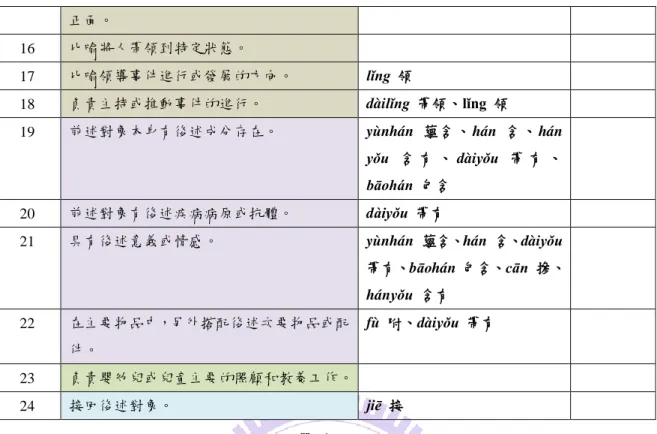

Sense Definition Synonym Variation

1 將物品繫掛在身上。 guà 掛 dài 戴 2 將物品放在能發揮物品功能的人的身體特 定部位。 dài 戴 3 比喻承受特定罪名。 dài 戴 4 比喻過度稱讚特定對象以提高其地位。常與 「高帽」連用。 dài 戴 5 比喻特定男子的配偶與他人交往。常與「綠 帽」連用。 6 有支配權的人使所支配的特定對象跟著自 己移動。 xī 攜、dàiyǒu 帶有 7 使特定對象跟著有支配權的人移動。 xī 攜 8 使特定對象到達特定地點進行特定事件。 9 以法律或其他強制力量將後述對象押到後 述地點。 10 前述物體移動時的力量影響後述物體使其 跟著前述物體移動。 xī 攜 11 購買並將貨品帶回。 12 經過時順便把門或窗戶關上。 13 走在前面,引導前進方向。 dàilǐng 帶領、lǐng 領 14 上級帶領下級做後述事件。 lǐng 領、 shuài 率、shuàilǐng 率領、bù 部、 shuài 帥 15 發揮個人領袖特質帶領後述對象,通常用於

Table 1. Senses of dài 帶‘bring’ in Chinese WordNet

Based on the sense descriptions and synonym pairs, the various senses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ can be further simplified and grouped into six lexical meanings:

1) To wear (guà 掛, dài 戴), as in (1~5)

2) To bring to (somewhere) (xī 攜, dài 帶), as in (6~12) 3) To lead (dàiling 帶領, shuài ling 率領), as in (13~18)

4) To be with (something) (yùnhán 蘊含, dàiyǒu 帶有, bāohán 包含), as in (19~22)

5) To take care of/bring up (zhàogù 照顧、fǔyang 撫養), as in (23) 6) To pick up (jiē 接), as in (24)

In addition to the senses identified in Chinese WordNet, three other senses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ are also observed with a further look at the corpus data, as listed below:

正面。 16 比喻將人帶領到特定狀態。 17 比喻領導事件進行或發展的方向。 lǐng 領 18 負責主持或推動事件的進行。 dàilǐng 帶領、lǐng 領 19 前述對象本身有後述成分存在。 yùnhán 蘊 含 、 hán 含 、 hán yǒu 含 有 、 dàiyǒu 帶 有 、 bāohán 包含 20 前述對象有後述疾病病原或抗體。 dàiyǒu 帶有 21 具有後述意義或情感。 yùnhán 蘊含、hán 含、dàiyǒu 帶有、bāohán 包含、cān 摻、 hányǒu 含有 22 在主要物品中,另外搭配後述次要物品或配 件。 fù 附、dàiyǒu 帶有 23 負責嬰幼兒或兒童主要的照顧和教養工作。 24 接回後述對象。 jiē 接

7) To bring with (something) (xīdài 攜帶): 他身上帶著護照。

tā shēnshàng dài zhe hùzhào

he body-on bring ASP passport ‘He brought the passports with him.’ 8) To activate (dàidòng 帶動):

正妹啦啦隊場邊帶氣氛

zhèng.mèi-lālāduì chăng-biān dài qìfēn

pretty.girl-cheerleader spot-side bring atmosphere

‘The pretty cheerleaders were activating the atmosphere on the side of the court.’

9) To appear/show with (chéngxiàn 呈現): 每個人的臉上都帶著笑容,

Měi.ge.rén de liăn-shàng dōu dài zhe xiàoróng

Everyone DE face-on all bring ASP smile ‘Everybody shows smiles on the face.’

Other from the multiple uses, the corpus data also show that the identification and determination of the lexical meaning of dài 帶 ‘bring’ is at first sight associated with its grammatical behaviors. Three syntactic patterns are found to be frequently associated with three specific lexical meanings, as listed below:

(1) To Bring to: [他]NP1帶[小英]NP2[到]Coverb[醫院]NP3 [看醫生]VP

tā dài XiăoYīng dào yīyuàn kàn yīsheng

‘He brought Xiao-ying to the hospital to see the doctor.’ (2) To lead: [他]NP1帶[大家]NP2[唱歌]VP

tā dài dà- jiā chàng.gē

he bring every-body sing.song ‘He leads everybody to sing.’

(3) To bring with: [他身上]NP1帶著[護照]NP2

tā shēnshàng dài zhe hùzhào

‘He carried the passports with him.’

In (1), dài 帶 ‘bring’ in the use of bring to occurs in the construction realized as [NP1<帶 <NP2<Coverb+NP3<(VP)] where the Coverb usually specifies the Path of motion2. With this construction, dài 帶 ‘bring’ depicts a motional event in which a person or an entity undergoes a locational change. As for (2), dài 帶 ‘bring’ depicts a leading event where the Agent leads and initiates an activity in the sense of lead. Without the encoding of the motional event, leading dài 帶 ‘bring’ is thus found to be associated with the structure of serial verb construction [NP1<帶<NP2<VP] where no path is lexically specified. As for (3), dài 帶 ‘bring’ can also highlight the co-existence relation between the Agent and the Theme without specifying motion or activity in the transitive form [NP1 帶 NP2], which pertains to the meaning of bring with (xīdài 攜帶).

2 In this study, the coverb refers to the path verbs that are mentioned in Liu et al (2013) including dào/

zhì/xiàng/wǎng/shàng/xià/jìn/chū/huí 到/至/向/往/上/下/进/出/回 and the deictic verbs lái/qù 來/去. According to Liu et al (2013), the path of motion is redefined into Route, Direction and Endpoint, and these verbs are claimed to encode different semantic components. Dào/zhì 到/至 ‘arrive, to’ are the Endpoint marking verbs which always take a Loc-NP to denote the endpoint and allow no intervening elements; xiàng/wǎng 向 / 往 ‘face’ belongs to the direction markers that require an immediately following directional reference, the Direction-NP; shàng/xià/jìn/chū 上/下/进/出 encode Direction and Route; and húi 回 ‘return (to)’ encodes three components: Route, Direction, and Endpoint. As for lái/qù 來/去 ‘come/go’, they are used to mark the speaker-oriented deictic center and usually serve as the path delimiters.

Given the multi-faceted meanings mentioned above, the senses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in general fall into two domains: motion vs. non-motion, in which the motional use of

dài 帶 ‘bring’ normally depicts a caused-motion event that is further involved with the

agentive cause. In addition, there seems to be a form-meaning correspondence between the meanings and their grammatical patterns. In view that various senses of a polysemous word may have a shared, central origin, and the links between these senses form a network (Fillmore and Atkins 2000), it is interesting to note how these manifold meanings are originated and semantically related to each other. In order to distinguish each meaning and clarify their interrelations, this study aims to examine the corpus data to find out significant distributional and collocational patterns that might shed light on the distinct lexical meanings. With the defined semantic criteria, this study aims to provide a principled and systematic way to account for the semantic-to-syntactic correlations among different uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’.

1.3 Scope and Goal

The study aims at investigating the concept of caused-motion verb in Mandarin with the focus on the verb dài 帶 ‘bring’. From the corpus data, dài 帶 ‘bring’ differs from other caused-motion verbs such as tuī 推 ‘push’, lā 拉 ‘pull’ and tóu 投, zhí 擲, diū 丟, rēng 扔 ‘throw’ in terms of the causative manner of motion; that is, dài 帶 ‘bring’ behaves as a neutral verb that does not encode force exertion in manner. Moreover, an even more distinct property about dài 帶 ‘bring’ lies in the multiple lexical meanings it manifests, which may be closely related to its neutral status with a non-specified manner. With the focus on the multi-faceted nature of dài 帶 ‘bring’, this study attempts to identify and clarify the various meanings and their semantic-to-syntactic correlations under the conceptual domain of caused-motion event.

To define and categorize different meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’, this study investigates the distributional frequency, collocational patterns, and semantic attributes and distinctions manifested in different uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ with a corpus-based approach. The goal of this study aims to explore the following questions:

1) How can we distinguish and thus categorize the different uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ based on observations of its corpus distribution? That is, what are the specific grammatical and distributional patterns pertaining to the different uses of dài

帶 ‘bring’?

2) Based on the grammatical distribution, what kind of semantic distinctions can be postulated to differentiate the various senses of dài 帶 ‘bring’? That is, what are the semantic criteria underlying each use?

3) What are the interrelations between the semantic distinctions? And what is the process of semantic extensions giving rise to the various meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’?

In aim of answering the above questions, the study starts with a close investigation on the detailed syntactic and collocational behaviors of different uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’. The ultimate goal of the present study attempts to postulate a principled and systematic way to account for the multi-faceted meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ that is underlying the domain of caused motion, which is one of the fundamental domains in human cognition.

1.4 Organization of the Thesis

This study is organized as follows. Chapter one is the general introduction of this study with the background knowledge of the issue. Chapter two reviews previous works on caused-motion events and the corresponded English verbs bring and carry.

Chapter three introduces the database, theoretical frameworks and the applied methodology. Chapter four presents the findings of data that motivate this study. Section five proposes semantic-to-syntactic accounts for the various meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ and also their semantic interrelations. Chapter six concludes the study noting the significance of this thesis and related issues for future studies.

Chapter 2

Literature Review

Motion event has been a widely discussed issue concerned by linguists for recent decades. Caused motion, as the causative counterpart of self-initiated motion events is thus another important issue of discussion under such a concern. Mandarin verb dài 帶 ‘bring’, which literally corresponds to the English verb bring or carry, can be described as a ‘verb of continuous causation of accompanied motion in a deictically-specified direction’ (Gropen et al 1989). However, contrary to English bring, the meaning and uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ are beyond the semantic domain of caused-motion. In this section, the traditional notions of caused-motion events and previous studies on the English verbs bring and carry will be reviewed. Section 2.1 reviews the previous works on caused-motion events in both English and Mandarin and Section 2.2 introduces two different approaches in viewing English verbs bring and carry.

2.1 Previous Works on Caused-motion Events 2.1.1 The Lexicalization Patterns of Motion

Talmy (2000) proposes a cognitive semantics account on the lexicalization patterns of motion events. It suggests that a motion event contains four internal components: Figure, Move, Path, and Ground, in which the Figure is a movable object; the Ground is a reference object or frame; the Path is what followed or site occupied by the Figure object with respect to the Ground object; and the Move refers to the occurrence of translational motion. Thus, a typical motion event is depicted as ‘an object (the Figure), under a motional act (Move), moving or located with respect to a location (the Ground) following a path or site at issue.’ (Talmy 2000: 25) In addition, he also points out that motion events can be associated with two external co-event

components: Manner and Cause, as illustrated in (4) below:

(4) a. The pencil rolled off the table. [Move+Manner]

b. I pushed the keg into the storeroom.

[Move+Cause] (Talmy 2000, vol. II: 26, 4)

In (4a), the verb rolled expresses how the pencil moves and so expressed as Manner, whereas pushed in (4b) specifies an external force of I that causes the keg to move and so describes the cause of the event. In other words, Manner and Cause can conflate with Move encoded in the motion verb so as to describe the way of the occurrence of motion.

Talmy (2000) further identifies the constructions underlying the co-event conflation in order to account for the relations that the co-event bears to the main Motion event. The patterns are indicated by the forms WITH-THE-MANNER-OF and WITH-THE-CAUSE-OF that function semantically like the subordinating preposition or conjunction of a complex sentence (Talmy 2000: 29). Therefore, the unconflated paraphrases of the English motion expressions for (4) can be further illustrated as below:

(5) a. The rock rolled down the hill

=[The rock MOVED down the hill] WITH-THE-MANNER-OF [the rock rolled]

=[I AMOVED3 the keg into the storeroom] WITH-THE-CAUSE-OF [I kicked the keg].

(Talmy 2000 vol. II: 30)

Under the lexicalization patterns and the co-event conflations, it has revealed by Talmy (2000) that the translational motion event can usually be divided into two types: self-intiated motion event and caused-motion event.

2.1.2 The Prototypical Caused-motion Event

Concerned with the notion of caused-motion, Li (2007) identifies and defines the conceptual prototype of a caused-motion event from the cognitive-based approach and Prototype Theory. According to Li (2007), the basic concept of the caused-motion event involves two causally-related entities or subevents, in which one entity causes the other to undergo a certain change of location. Thus, it is postulated that the typical caused-motion event involves with two required events: causing event and motion event, as represented below:

(6) Typical Caused-motion Event

Causer Causing Action Theme Motion Causing event Motion event

(Li 2007: 23)

As to the internal elements conceptualized in the caused-motion event, it is

3 The subscript “

A” is placed before a verb to indicate that a verb is agentive. (AMOVED= CAUSE to

suggested that the on-going event as a whole is perceived as consisting of five internal components: Causer, Theme, Driving Force, Motion, and Path, which come together form a gestalt of the conceptual structure of caused motion with the meaning: ‘the Causer causes the Theme to move along a Path.’ Thus, the schematic representation of a typical caused-motion concept can be represented as below:

(7) Typical Caused-motion concept

Causer Driving Force Theme Motion Path

(Li 2007: 24)

In such a conceptual structure, the Causer is the source of the Driving force; the Theme is the energy goal entity who undergoes a change of location resulted by the impact of the Driving force exerted by the Causer; and the Driving force is the transmitted energy exerted by the Causer onto the Theme. Based on the above concepts, Li thus defines the prototypical caused-motion event as consisting of a human Causer volitionally exerts physical force acting upon a physical theme that immediately causes the theme to move along a Path to a physical space.

Incorporating the accounts of motion events proposed by Talmy (2000) and Li (2007), we can categorize dài 帶 ‘bring’ as a caused-motion verb for two reasons. For one, dài 帶 ‘bring’ is a verb that lexicalizes the co-event component Cause requiring an agentive causer. For the other, the event denoted by dài 帶 ‘bring’ usually requires two subevents: a causing event and a motion event. Take (8) as an example:

(8) 我 帶 錢 到 學 校 Causing event + Motion event

wǒ dài qián dào xuéxiào

I bring money arrive school ‘I brought the money to school.’

But it should be noted that in the motion event of dài 帶 ‘bring’, there involves the concurrent movement of Agent and Theme, which can be ascribed to the inherent lexical meaning of dài 帶 ‘bring’, which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 5. Thus in (8), the Agent 我 ‘I’ and the Theme 錢 ‘money’ both undergo the movement.

2.1.3 Constructional Analysis of Caused Motion

In addition to the lexical and cognitive approaches to caused motion, there are constructional-based accounts for caused motion event encoded in English and Chinese. Under the framework of Construction Grammar, Goldberg (1995) defines English caused motion as structurally following the pattern: [SUB [V OBJ OBL] and such a form is associated with the meaning ‘X CAUSES Y TO MOVE Z’; that is, the causer

argument directly causes the theme argument to move along a path designated by the directional phrase. The form-meaning correspondence can be represented by the following figure:

With the mapping of the syntactic form and the constructional meaning, it is postulated that any lexical verb will be associated with the sense of caused motion under this construction whether or not it encodes the sense of motion. For instance, the verb

sneeze in ‘the napkin is sneezed off the table.’

As for Mandarin Chinese, Pan and Chang (2005) make a comparison of English and Chinese caused-motion constructions and conclude with some characteristics for the Chinese case. It has pointed out that Chinese caused-motion event can be expressed by the V-Direction Structure, as in tā bă mùtong tí shànglái le 他把木桶提上來了 ‘He has lifted the buckets up.’ or the V-Preposition Structure, as in tā bă chē kāi dào nánjīng

le 他把車開到南京了 ‘He has driven the car to Nanjing.’ In addition, Chinese

commonly use causative markers, such as bǎ 把, shǐ 使, or rang 讓 to express causative motion. As for English, the caused-motion notion in English can only be expressed by a single pattern: the caused-motion construction (i.e., [NP1 V NP2 PP]) and there exist no causative markers in English. On the other hand, Chinese shows more various ways in expressing the Path of motion. In Chinese, the path can be encoded by a preposition or non-predicate verb following a main verb to indicate the direction, such as V在, V到, V向, V往, V上來, V下來, V進來, V出來, V回來, whereas the path of motion in English can only be marked by preposition. The contrast can be shown in (9) and (10):

(9) Chinese caused-motion pattern: a. 他把車開到南京了。

tā bǎ chē kāi dào nánjīng le

he BA car drive arrive Nanjing le ‘He drove the car to Nanjing.’ b. 他把球扔向了我。

he BA ball throw face le me ‘He threw the ball to me.’ c. 我們把羊群放出去了。

wǒmen bǎ yang.qún fàng chū.qù le

we BA goats.group release out.go le ‘We had let go of the goats out.’ (10) English caused-motion pattern:

a. He threw the stone into the river. b. Jane sewed a button onto the jacket.

Accordingly, a typical Chinese caused-motion construction may show various patterns in encoding a caused-motion event, either with a transitive V-O sequence plus a locational or directional prepositional phrase, or with an overt causative alternation marked by a causative marker, as will be clear in the use of dài 帶 ‘bring’.

2.1.4 Proto-Motion Event in Mandarin Chinese

Concerning motion event in Mandarin Chinese, Liu et al (2013) on the conceptual basis identify and propose the proto-motion sequences in Mandarin. It is identified that Mandarin motion event contains five salient semantic components: Manner, Route, Direction, Endpoint, and Deictic, in which Route, Direction, and Endpoint are the redefined morphemes of the traditional notion of Path. With these components, a

Deictic-Incorporated Proto-Motion Event Schema is proposed (Figure 2), which observes the natural motion progression following the left-to-right linear sequence: from Manner to Route to Direction and to Endpoint. The proto-motion event schema thus demonstrates an iconic representation of Mandarin motion event.

Figure 2. The Deictic-incorporated Proto-Motion Event Schema

Following the schema, it is observed that motion verbs may lexicalize one or more of the semantic components in the sequence, such as in the following example:

(11) 球 [滾]Manner[落]Route[進]Direction[到]Endpoint[洞裡]Loc-NP[來]Deictic

qiú gǔn- luò- jìn- dào dònglǐ lai

ball roll fall enter arrive hole-inside come

‘The ball rolled and fell down into the hole.’

In (11), the leftmost verb V1 gǔn 滾 ‘roll’ lexically encodes Manner; V2 luò 落 ‘fall’ encodes both Route and Direction; V3 jìn 進 ‘enter’ lexicalizes Direction and Endpoint, and the rightmost V4 specifies Endpoint.

Based on Liu et al (2013), we can observe that Mandarin dài 帶 ‘bring’ depicts a

serial motion event that is further involved with a Cause or Causing event, as can be seen from the following example:

(12) 我帶學生 [跑]Manner[到]Endpoint[校外]Loc-NP[去]Deictic Cause +

wǒ dài xuéshēng pǎo dào xiào.wài qù

I bring students run arrive campus.outside go

‘I brought the students to run to the outside of the campus.’

2.2 Previous Works on English Verbs Bring and Carry

Since the polysemic verb dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Mandarin literally corresponds to the English verb bring or carry, it is assumed that this verb may share some similarities and differences to its English equivalents. In this section, two previous works on English verbs bring and carry will be reviewed from two different approaches. Section 2.2.1 reviews Levin’s (1993) alternation-based approach on the classification of bring and

carry verbs and Section 2.2.2 introduces the frame-based approach on bring and carry

in FrameNet.

2.2.1 Levin (1993): Verbs of Sending and Carrying

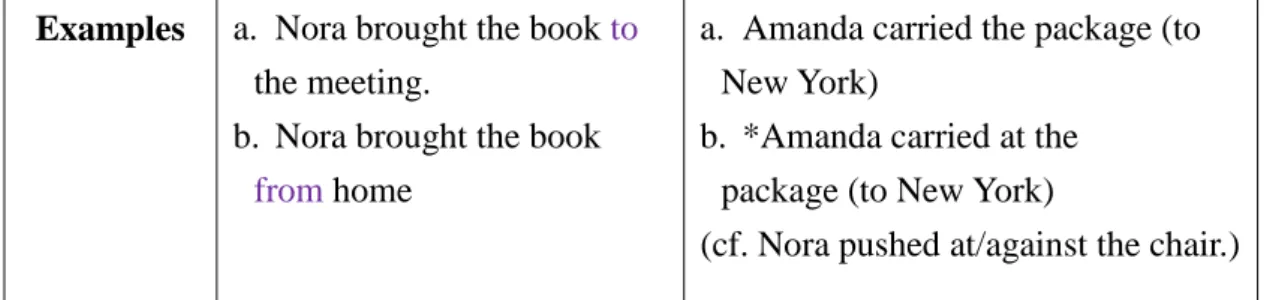

Levin (1993) assumes that verbal behaviors, particularly with respect to the expression and interpretation of its arguments, provide key evidence to investigate the lexical meaning of verbs. Under this assumption, Levin (1993) sets a pioneering work on the classification of English verb based on the alternative syntactic verbal behaviors. According to Levin (1993), English verb bring and carry are classified under the Verbs of Sending and Carrying, in which bring and carry are associated with two subclasses. Table 2 presents the classification of the two verbs:

Verb Class Verbs of Sending and Carrying

Subclass Bring and take Carry Verbs

Class members

bring, take(only) carry, drag, haul, heave, heft, hoist, kick, lug, pull, push, schlep, shove, tote, tow, tug

Examples a. Nora brought the book to the meeting.

b. Nora brought the book from home

a. Amanda carried the package (to New York)

b. *Amanda carried at the package (to New York)

(cf. Nora pushed at/against the chair.)

Table 2. Verbs of Sending and Carrying in Levin (1993)

The verbs bring and take as a subclass has been described as the causative counterparts of come and go. In addition, they are set apart from other verbs by the presence of the deictic component of meaning and the lack of a meaning component that specifies the manner in which the motion is brought out. Moreover, these verbs can also be used as verbs of change of possession brought about by a change of position, as shown by their ability to occur in dative alternation.

(13) Dative Alternation:

a. Nora brought the book to Pamela.

b. Nora brought Pamela the book.

(Levin 1993:134)

As for carry, which is under the subclass of Carry Verbs, has been described as relating to the causation of accompanied motion which must be overtly specified in a prepositional phrase. But differ from other class members that are cross-listed as verbs of exerting force such as push and pull, carry is a verb that does not encode sense of force exertion, as can be seen from the evidence that verbs of exerting force allow conative at phrase while verbs of causation of accompanied motion does not. (e.g. Nora

pushed at/against the chair vs. *Amanda carried at the package (to New York))

To sum up the above descriptions, bring and carry have the following shared and distinct characteristics: 1) both are verbs of causative motion that must be specified

overtly by the deictic component in the prepositional phrase, 2) bring does not specify Manner; carry does not encode force exertion. As to the contrast between them, bring can be used as a verb of change of possession brought about by a change of position, while carry seems not, as shown by their contrast in the dative alternation in (14ab) and (14cd):

(14) Dative alternation: bring vs. carry a. Nora brought the book to Pamela b. Nora brought Pamela the book

c. Amanda carried the package to Pamela. d. ?Amanda carried Pamela the package

2.2.2 Fillmore and Atkins (1992): FrameNet

FrameNet (https://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/), created by Charles J. Fillmore and his colleagues in University of California Berkeley, is an online lexical database for English lexicon devised on the basis of frame semantics. It is built up based on the semantic frames of English lexicon, each of which is clearly defined by the core and non-core frame elements together with the support of syntactic evidence extracted from actual texts. In FrameNet, different verbs that share the same frame elements can be in the same semantic frame. Thus, one frame may contain several lemmas of verbs that share similar semantic attributes. Futhermore, FrameNet also shows the associations of different frames by graphing the hierarchical and interrelated structures that demonstrate the frame-to-frame relationships.

According to FrameNet, English verb bring and carry are classified under the

Bringing Frame. This frame is defined as follows with an example:

The Agent, a person or other sentient entity, controls the shared Path by moving the Theme during the motion. The Carrier may be a separate entity, or it may be the Agent's body.”

e.g. Karl CARRIED the booksacross campus to the libraryby truck.

The core frame elements involved in this frame are Agent, Theme, Carrier, Goal, Path, Source, and Area. The lexical units included in this frame are: bring.v,

carry.v, bear.v, convey.v, drive.v, ferry.v, get.v, haul.v, motor.v, portable.a, take.v, transport.v, and etc. According to the FrameGraphers4, Bringing Frame is under the

Motion and Cause_motion Frame in ‘Using’ relationship5 as they share the same background frame information of the elements: Area, Goal, Path, and Source pertaining to these frames.

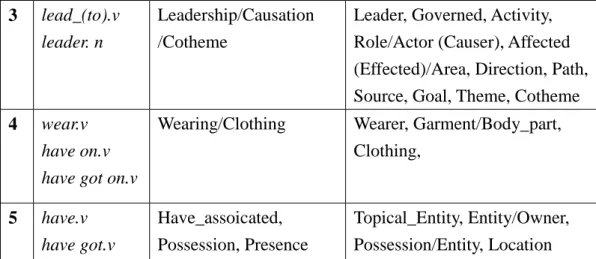

Other from English verbs bring and carry, due to the polysemic nature of dài 帶 ‘bring’, the English equivalent lexical units of different meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ (noted in Section 1.2) can also be associated with multiple frames in FrameNet, which is summarized in Table 3.

English Lexical Units

Semantic Frames Core Frame Elements

1 bring.v Bringing/Causation Agent, Theme, Carrier, Goal, Path, Source, Area/Actor (Causer), Affected (Effected) 2 carry.v Bringing/Carry_goods Agent, Theme, Carrier, Goal, Path, Source, Area/Distributor, Goods

4 FrameGrapers in the FrameNet shows the connections of several frames, demonstrating the frame-to-frame relationships by different arrows representing respectively the relationships of Inheritance, Using, Precedes, Perspective_on, Inchoative_of, Causative_of, and See_also.

5 In FrameGraper, ‘Using’ relationship refers to a frame that uses part of background information (some core frame elements) of another frame.

3 lead_(to).v leader. n

Leadership/Causation /Cotheme

Leader, Governed, Activity, Role/Actor (Causer), Affected (Effected)/Area, Direction, Path, Source, Goal, Theme, Cotheme 4 wear.v

have on.v have got on.v

Wearing/Clothing Wearer, Garment/Body_part, Clothing, 5 have.v have got.v Have_assoicated, Possession, Presence Topical_Entity, Entity/Owner, Possession/Entity, Location

Table 3. English Equivalent Lexical Units of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in FrameNet

Table 3 shows that the use of dài 帶 ‘bring’ may correspond to different verbs in English, which in turn proves that dài 帶 ‘bring’ indeed manifests the cross-frame nature of lexical meanings. Each lexical meaning, under FrameNet, is categorized in different or shared semantic frames with distinct frame-specific elements. For examples, except for Bringing Frame, English verbs bring and carry are also respectively belong to Causation and Carry_goods Frame. Causation Frame describes a background idea where some event is responsible for the occurrence of another event (or state); that is, a Cause or Actor causes an Effect or Affected. As for

Carry_goods Frame, it describes a situation where a Distributor sells, lends, or

otherwise distributes a class of Goods. And it is noted that the Distributor may carry some particular goods, but may not have it on hand at that exact moment.

FrameNet indeed provides a useful overview of the semantic information regarding bringing verbs in English. Nevertheless, due to the fact that the semantic frames defined in FrameNet are based on English lexicon, the definition and the defined frame elements may not be felicitous in defining the verbal semantics of Mandarin verbs. In addition, FrameNet did not concern the constructional pattern, so the subtle meaning distinction cannot be retrieved and recognized among the different

lexical units within the same frame. Therefore, to complement FrameNet with constructional criteria, this study will incorporate the constructional analysis in order to provide a more comprehensive and fine-grained account for the polysemic verb dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Mandarin.

2.3 Summary

In this chapter, different approaches to the studies of motion events and bringing verbs in English have been reviewed. On the conceptual basis, Talmy (2000) explored the lexicalization patterns of the motion event, while Li (2007) identified the prototypical notion of caused motion with the Prototype Theory. Within a constructional framework, Goldberg (1995) proposed English caused-motion construction considering the form-meaning correspondence, while Pan and Chang (2005) claimed the various patterns for Chinese caused-motion constructions. Liu et al (2003) looked into the unique sequential order of motion verbs and postulated the prototypical linear sequence in Mandarin motion event. On the other hand, Levin (1993) and Fillmore and Atkins (1992) viewed and classified English bring and carry respectively from the alternation-based and frame-based approach.

Though numerous studies have focused on motion events, few studies have paid attention to the unique behaviors of Mandarin dài 帶 ‘bring’ as a frequently occurring verb in the motion domain. With a corpus-based investigation, this study aims to go beyond the above studies by looking into the collocational patterns, and the semantic-to-syntactic attributes to account for the polysemic dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Mandarin in light of the conceptual and grammatical structures of caused motion.

Chapter 3

Database, Theoretical Frameworks, and Methodology

3.1 Database

The corpus data used in this study are selected from two sources: 1) Academic Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese (http://db1x.sinica.edu.tw/kiwi/mkiwi/), which collects literary works on different topics and registers, and is now currently contains ten millions words; 2) the Chinese Word Sketch Engine (CWS) (http://wordsketch.ling.sinica.edu.tw/), which provides the functions of the query of keywords and collocation associations. Other sources used in this study also include: 1) the on-line resource Google search engines (http://www.google.com/) and FrameNet (https://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/).

Among all the databases, Sinica Corpus contains 3050 lexical entries of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in total, while Gigawords in Chinese Word Sketch Engine contains 79064 entries of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in total. Some of the data are selected and analyzed as the key data in the present study.

3.2 Theoretical Frameworks

The present study aims to explore the polysemy of dài 帶 ‘bring’ by adopting the frame-based lexical constructional approach, which integrates the framework of Frame Semantics (Fillmore and Atkins 1992) and Construction Grammar (Goldberg 1995, 2010). In addition, the theoretical foundations laid on the studies of polysemy, including Langacker’s semantic profile and the prototypical theory, are also adopted to account for the manifold meaning relatedness of dài 帶 ‘bring’. The above mentioned theoretical frameworks will be briefly reviewed in this section.

3.2.1 Frame-based Lexical Constructional Approach

The frame-based lexical constructional approach is a new framework proposed and adopted by this study which combines Frame Semantics and the constructional approach given by Fillmore and Atkins (1992) and Goldberg (1995). The core conception of the two approaches will be given in this section and followed by an overview of these two approaches.

Frame Semantics is the theory of linguistics proposed by Fillmore and Atkins (1992) that defines the meanings of a lexicon based on the conceptual background knowledge. That is, one cannot understand a word without accessing to the essential knowledge related to the word. Under this assumption, every lexicon is proposed to evoke one or more semantic frames which own a set of core frame elements that are defined by the participant roles involved in the event. Also, it is noted that the profile of different frame elements will lead to different syntactic realizations. Hence, verb meanings can be distinguished and identified through different frame elements and relevant syntactic behaviors that verbs are involved with.

As for the constructional approach proposed by Goldberg (1995), the theory of Construction Grammar takes constructions as basic units of language. The construction itself represents “form-meaning correspondences that exist independently of a particular verb.” (Goldberg 1995:1) That is, the semantics of the construction is not compositionally derived from other constructions existing in the grammar. Moreover, CG recognizes the fact that the relations of verb and construction are interrelated but independent. The basic meaning of a construction relies on both verbs’ profiled participant roles and the argument roles associated with the construction, as demonstrated by the difference between rob and steal:

(15) rob <thief target goods>

steal <thief target goods> (Goldberg 1995:45)

As an overview of the above two approaches, Frame Semantics indeed provides overall frame-relevant semantic information of the participant roles that a verb may involve with and offers a way to categorize different semantic frames for a wide range of lexical items. Nevertheless, it ignores a crucial fact about the construction that a verb may participate in and hence may sometimes fail to capture the constructional meaning that interacts with the lexical meaning of verbs. On the other hand, construction grammar provides a new way to analyze the composition of the arguments on the basis of form-meaning correspondences. However, this theory is somehow too powerful and overgeneralized, so that it may ignore the semantic-to-syntactic restrictions and variations manifested by lexical verbs that fall into the same semantic class.

In view of the above, this study incorporates the above two approaches to explore the interactions of lexical semantics and construction that underlie the syntactic realizations of the polysemic verb dài 帶 ‘bring’ in Mandarin Chinese. Together with a detailed bottom-up analysis of the corpus data, this study aims to ultimately offer a more fine-grained categorization and semantic anlaysis on the multi-faceted meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’.

3.2.3 The Prototypical Category Theory and Semantic Profile

In addition to frame-based and constructional-based frameworks, the present study also adopts the frameworks of the Prototypical Category Theory and Semantic Profile to account for the semantic relation of the multiple meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’. According to Rosch (1978:36), prototypes can be defined as the ‘clearest cases of category membership defined operationally by people’s judgments of goodness of

membership in the category’. A prototype of a category is thus viewed as a salient exemplar of the category. In other words, people categorize objects on the basis of the resemblance of the shared attributes between the prototypical members of the category and the objects. For examples, sparrows, robins, and etc are the prototypical instances of the category birds, but chickens, ostriches, and penguins are not the central members and thus are non-prototypical cases. Taylor (1995) further explicates two interpretations of prototype. One is that we can apply prototype to the central member or the cluster of central members of a category, but we can also understand prototype as a schematic representation of the conceptual core of a category (Taylor 1995:59).

As for the concept of semantic profile proposed by Langacker (1987), it concerns the conception of the distinction between the scope of a predication and the entity designated by it, which is called as base and profile. The profile is defined as a kind of focal point, suggesting the special prominence of the designated element, while the base is the encyclopedic knowledge that the concept presupposes. As noted by him, ‘the semantic value of an expression derives from the designation of a specific entity identified by its position within a larger configuration.’ (Langacker 1987:183) Moreover, a single base forms a domain when it supports a number of different profiles. For instance, Circle is the base domain for the concept of arc, center, and circumstance since they are the concepts profiled by the configuration of Circle.

With the above theoretical concepts, this study aims to deal with the semantic relatedness of the polysemous dài 帶 ‘bring’ by applying the concept of prototypicality and the semantic base and profile in an aim to clarify the interrelationships among them.

3.3 Methodology

dài 帶 ‘bring’, this study adopts a corpus-based method to substantiate the findings

and analysis for this research. The procedure for the present research includes the following five steps:

Step 1: Collecting the corpus data

As a corpus-based study, the beginning step for this study is to collect as much as data of dài 帶 ‘bring’ from the selected databases. In this study, the main data come from the Sinica Corpus and Word Sketch Engine. Parts of the data are extracted from Google Search Engine.

Step 2: Observing and examining the data

With the collected data, the second step begins to observe any possible linguistic phenomenon revealed in the data, including both semantic and syntactic information such as argument structures, participant roles, collocations or lexicalization patterns of the verb.

Step 3: Sorting out the semantic meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’

In order to account for the multi-faceted meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’, with the preliminary observation of the data, the third step comes to sorting out the possible meanings manifested in dài 帶 ‘bring’.

Step 4: Categorizing the syntactic realizations of different meanings

The fourth step is to classify and categorize all the syntactic patterns of the data with regards to their associations with the meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’.

Step 5: Analyzing the semantic and syntactic correlations of the data

Finally, the above classifications of the semantic-to-syntactic relationships of

dài 帶 ‘bring’ will be analyzed on the basis of the theoretical frameworks

Following these steps, interesting findings of the corpus data will be first presented in the next chapter, and a detailed semantic analysis of the data will be provided in Chapter 5.

Chapter 4

Findings

This chapter aims to show some important findings obtained from corpus observations. These findings illustrate the basic semantic and syntactic phenomena manifested in Mandarin dài 帶 ‘bring’, which serve as crucial clues for the identification of different uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’. Section 4.1 presents the distributional frequency of dài 帶 ‘bring’ regarding the syntactic patterns and the semantic meanings, Section 4.2 shows the findings of the semantic distinction of the predominant motional and non-motional uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in terms of their defining patterns, participant roles and semantic attributes, Section 4.3 gives the collocation patterns of both motional and non-motional use with respect to their collocated morphemes and collocational restrictions. With these findings, the clues for the classification and definition of the multiple meanings of dài 帶 ‘bring’ will be established and the detailed analysis of the semantic relatedness and a framed-based analysis will be given in Chapter 5.

4.1 Distributional Frequency of Multi-Faceted dài 帶 ‘bring’

As indicated in the previous chapters, dài 帶 ‘bring’ is a verb that is found to bear multiple meanings. As suggested by Chinese WordNet and with the addition of corpus observation, dài 帶 ‘bring’ is found to exhibit at least nine meaning imports, repeated here as below:

1) To wear (pèidài 佩帶)

布希總統胸腔上帶著電子心臟監聽器,

Bush-president chest-on wearASP electric-heart-audio.monitor ‘President Bush wears a cardiac audiomonitor on his chest.’ 2) To bring to (dài 帶)

他帶小英去醫院看醫生

tā dài XiăoYīng qù yīyuàn kàn yīsheng

he bring Xiăo-Yīng go hospital see doctor

‘He brought Xiao Ying to the hospital to see the doctor.’ 3) To lead (dài ling 帶領)

他帶大家唱歌

tā dài dàjiā chàng.gē

he bring every-body sing.song ‘He leads everybody to sing.’ 4) To be with (dài yǒu 帶有)

這位女性並不帶男性特徵,

zhè-wèi nǚxìng bìng bú dài nánxìng tèzhēng

this-CL female Adv Neg bring male characteristic ‘This woman does not possess any masculine feature.’ 5) To take care of/bring up (zhào gù 照顧、fǔ yang 撫養)

我在家帶兩歲多的女兒,

wǒ zài.jiā dài liăng-suì.duō de nǚér

I at-home bring two-year.more DE daughter

‘I was taking care of my two-year-old daughter at home.’ 6) To pick up (jiē 接)

民宿的老闆娘還會到車站帶我。

Mínxiŭ de lăobănniáng hái.huì dào chēzhàn dài wǒ

‘The hostel hostess would come to the station to pick me up.’ 7) To bring with (xīdài 攜帶)

他身上帶著護照。

tā shēn shàng dài zhe hùzhào

he body-on bring ASP passport ‘He brought the passport with him.’ 8) To activate (dàidòng 帶動)

正妹啦啦隊場邊帶氣氛

zhèng.mèi-lālāduì chăng.biān dàiqìfēn

pretty.girl-cheerleader spot.side bring atmosphere

‘The pretty cheerleaders were activating the atmosphere on the side of the court.’

9) To appear/show with (chéngxiàn 呈現): 每個人的臉上都帶著笑容,

Měi.ge.rén de liăn-shàng dōu dài zhe xiàoróng

Everyone DE face-on all bring ASP smile ‘Everybody shows smiles on the face.’

Regarding the nature of polysemy, numerous studies have pointed out that polysemy is a single lexeme with distinct but etymologically related senses (Lyons 1977, 1995, Ravin and Leacock 2000). Also, polysemy is a gradient that straddles the border line between total semantic identity and distinctness and thus there is a meaning common to the sub-meanings (Tuggy 1993, Greeraerts 1993, Deane 1988). Taking dài 帶 ‘bring’ as a polysemic verb, we may thus wonder how the distinct meanings given in 1) to 9) are related to each other and in overall presents a prototype category. That is to say, what might be the predominant core meaning that pertains to the prototypical use

of dài 帶 ‘bring’? In order to explore this issue, the results of the investigation on the distributional frequency of dài 帶 ‘bring’ with respect to various uses and their syntactic patterns are presented as below:

Syntactic Patterns Meaning Count %

NP1<帶<NP2<Coverb + NP3< (VP) Bring to 191/415 46% 46% NP1<帶<NP2<VP Bring to 27/415 6.5% 19.5% Lead 25/415 6% Bring with 19/415 7% NP1<帶<NP2 Lead 2/415 0.5% 23.1% Bring with 40/415 9.6% Be with 41/415 10% Wear 6/415 1.4% Take care of 6/415 1.4% Activate 1/415 0.2% Lead 4/415 1%

Table 4. The Distributional Frequency of the Multi-faceted Uses of dài 帶6

Table 4 shows the grammatical distribution of the syntactic patterns of dài 帶 ‘bring’ and the relevant semantic distinctions they are associated with. It is revealed that dài 帶 ‘bring’ mainly occurs in three syntactic patterns: 1) NP1<帶<NP2<Coverb+NP3<(VP) 2) NP1<帶<NP2<VP and 3) NP1<帶<NP2, and among them the first pattern is the most salient and predominant one (occupied 46%), which is mostly associated with the use of dài 帶 ‘bring’ in the sense of bring to. The second and third patterns, serial verb construction (SVC) and simple transitive pattern, occupy about two times less than the first one. In these two patterns, SVC is used

6 The distributional frequency is based on the first 300 and 200 instances of Sinica and Gigawords, among them only 415 entries are taken into account as the usable data. The meaning of pick up and appear/show in dài 帶 are not included in this Table due to their low frequency in occurrence and the limited selected database in distributional frequency count. Nevertheless, they do appear in the corpus and the syntactic pattern they mostly involve pertains to the transitive pattern.

mainly for the sense of bring to, lead, and bring with in nearly equal frequency, while the transitive pattern is associated more freely with all the other senses. But among these uses, the senses of bring with and be with show a higher frequency.

Other from the three major types of constructions dài 帶 ‘bring’ occurs in, it is also observed from the corpus that dài 帶 ‘bring’ in the sense of bring to can participate in the most diverse ranges of syntactic alternations, as shown in the following Table. As for other uses, only dài 帶 ‘bring’ in the sense of lead and bring

with are involved with syntactic alternations, such as resultative De construction and

locative Zài construction.

Syntactic Alternations

Transitive-Bă NP1<把<NP2<帶<Coverb+NP3<(VP) Bring to 18/415 4.3% 10% Passive-Bèi NP2<被<NP1<帶<Coverb+NP3<(VP) 13/415 3.1% Causative- Ràng NP1<讓<NP2<帶<NP3<Coverb+NP3<VP 1/415 0.2% Dative- Gěi a. NP1<帶<NP2<給<NP3 b. NP1<帶<給<NP2<NP3 7/415 1.7% Resultative-De NP1<把<NP2<帶<得<C Bring to 1/415 0.2% 1.2% Lead 4/415 1%

Locative-Zài NP1<帶<NP2<在<NP3 Bring with 3/415 0.7% 0.7% Table 5. The Distributional Frequency of the Multi-faceted Uses of dài 帶 ‘bring’ with Respect to

Syntactic Alternations

Given the distribution of syntactic patterns with the associated meanings, Table 6 provides another view by showing the distribution of the lexical meanings with respect to the possible syntactic patterns they may respectively involve.

Meanings Syntactic Patterns Count Total

Bring to

NP1<帶<NP2<Coverb + NP3< (VP) 191/415 46%

62.2%

NP1<帶<NP2<VP 27/415 6.5%