i

國立臺灣大學生物資源暨農學院農業經濟學系 碩士論文

Department of Agriculture Economics College of Bio-Resources and Agriculture

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

運動強度與老人心理健康之探討 Exercise Intensity and Mental Health

of the Elderly in Taiwan

楊豐安 Feng-An Yang

指導教授:張宏浩 博士 Advisor: Hung-Hao Chang, Ph.D.

中華民國 99 年 7 月

July, 2010

i

謝辭

兩年的碩士生活很快地過去了,在這段期間很幸運地能接受張宏浩老師的指 導,使我成長很多。感謝老師,我真的學到很多東西,除了學術研究能力的培養 之外,在做人與做事的態度上,老師也給我很多啟發,讓我知道做人要有責任感,

做事要有責任心。

碩士班兩年的日子,有歡笑也有淚水,首先感謝同門的純嫣,妳是最好的夥 伴,有妳的幫忙事情總是能快速的解決,還有大師兄大川及學妹彥慈、婉婷,很 開心能與你們共事、互相幫忙。當然還有林儂、子凡、致豪及 R97 的好朋友們,

還記得一起熬夜唸書、出遊、聚餐及唱歌的日子,有太多的回憶,謝謝你們。也 要感謝系辦公室最親切的美華姊及系電腦室的秀姬姊,謝謝妳們這兩年來的幫忙 及照顧。

感謝我的家人一直以來對我的付出與支持,雖然碩士班的日子相當忙碌,但 一回到家總是能感受到家庭的溫暖。謝謝老爸、老媽對我的栽培,謝謝老弟的支 持,也謝謝伴我長大的親人們,謝謝你們的鼓勵。

最後要特別謝謝宥苡這六年來的陪伴,謝謝妳陪我渡過大學與碩士生涯的時 光,不管我遇到任何的困難,妳都會仔細聽我訴說及伴我左右。也謝謝妳在我撰 寫論文時,給我最大的包容與體諒,謝謝妳。

楊豐安 謹誌於 國立臺灣大學農業經濟學研究所 中華民國九十九年七月

ii

摘要

過去幾十年來,長期低出生率及死亡率使得台灣人口結構快速老化,此一現 象也帶來許多社會及公共衛生問題,其中老年憂鬱症已備受關注,它除了會降低 生活品質之外,還會造成老人自殺的問題。在影響老年憂鬱的因素當中,運動已 被提及為有效促進老人心理健康的方法,甚而運動強度也被認為是影響老人心理 健康的關鍵因素,但是過去研究運動強度的文獻多以小樣本實驗或橫斷面資料來 分析,對老人最適運動強度的決定也尚未有明確定論。因此本研究探討台灣老人 運動強度與心理健康的關係來做為老人運動處方的參考。

本研究的資料來源為 1996、1999 及 2003 年的中老年身心社會生活狀況長期 追蹤調查,並以運動後喘氣的程度做為衡量運動強度的指標。不同於以往文獻,

本文先建立三期均衡式追蹤資料,並利用固定效果模型來進行實證分析,藉此方 法可以控制潛在無法觀察到的異質性(unobserved heterogeneity)對老人心理健康 之影響。實證結果顯示,運動對老人心理健康有顯著的助益,其中低強度運動較 中強度運動為優;平常規律做低強度運動的老人得到憂鬱症的機率較沒運動的老 人低 12%,然而中強度運動卻對老年憂鬱症沒有顯著的影響。研究結果亦有其政 策意涵:儘管低強度與中強度運動皆可以改善老人心理健康,本研究建議未來推 廣老人運動與心理健康時,需特別注意運動強度,對台灣老人而言,低強度運動 為最適運動強度。

關鍵字:心理健康、憂鬱、運動強度、老人、追蹤資料

iii

Abstract

Due to the high prevalence of depression among the elderly in Taiwan, the objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between exercise intensity and mental health. Although it has been documented that regular exercise is a significant factor associated with older people’s psychological well-being, the optimal pattern of exercise intensity is at best inconclusive.

In contrast to previous studies, this study utilizes a longitudinal survey of the elderly in Taiwan. The nonlinear panel data models are estimated using the fixed-effect method to control for potential unobserved heterogeneity and accommodate the censored and binary outcome variables.

Using personal perceived breathing level as the measurement of exercise intensity, the estimation results revealed that regular exercise contribute to better mental health, but low intensity was much better than moderate intensity. The results also suggested that moderate intensity exercise is not significant of depression, while low intensity exercise had led to twelve percent lower in probability of depression.

Some policy implications can be inferred from our findings. Although the results support that both light and moderate exercise are aggressive tools for improving mental health of the elderly, however, light intensity exercise can be seen as an optimal pattern of exercise for the Taiwanese elderly.

Key words: mental health, depression, exercise intensity, elderly, panel data

iv

Contents

謝辭... i

摘要... ii

Abstract ... iii

Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Motivation ... 1

1.2 Objective ... 3

1.3 Organization ... 4

Chapter 2 Literature Review... 5

2.1 Depression in late life ... 5

2.2 An overview of exercise and mental health among elderly ... 7

2.3 Intensity of exercise ... 9

2.4 Summary ... 13

Chapter 3 Data ... 15

3.1 Source ... 15

3.2 Measures of dependent variables ... 16

3.3 Measures of independent variables ... 18

3.3 Sample Description ... 21

Chapter 4 Methodology ... 26

4.1 Econometric specifications ... 26

4.2 Fixed-effect Tobit model ... 28

4.3 Fixed-effect probit model ... 30

Chapter 5 Results ... 32

5.1 The determinants on mental health... 32

5.2 The determinants on depression ... 35

Chapter 6 Conclusion ... 37

Reference ... 40

v

List of Tables

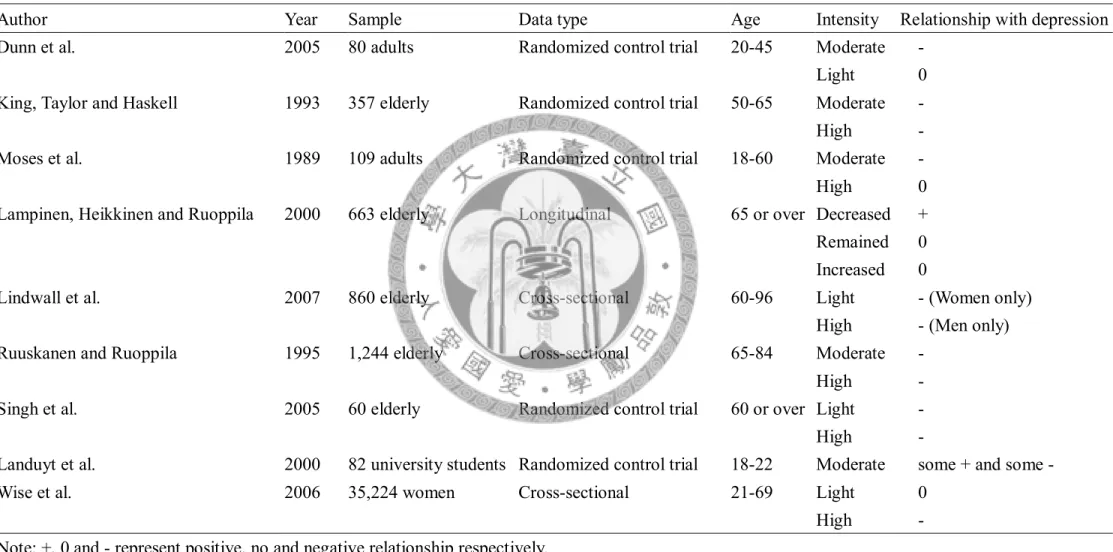

Table 1 Summary table of studies examining the relationship between exercise

intensity and depression ... 14

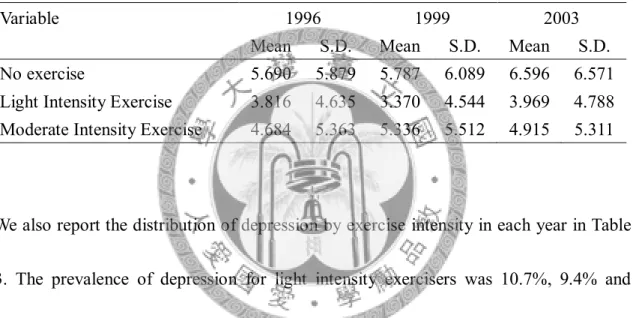

Table 2 Mean score of mental illness by exercise type ... 22

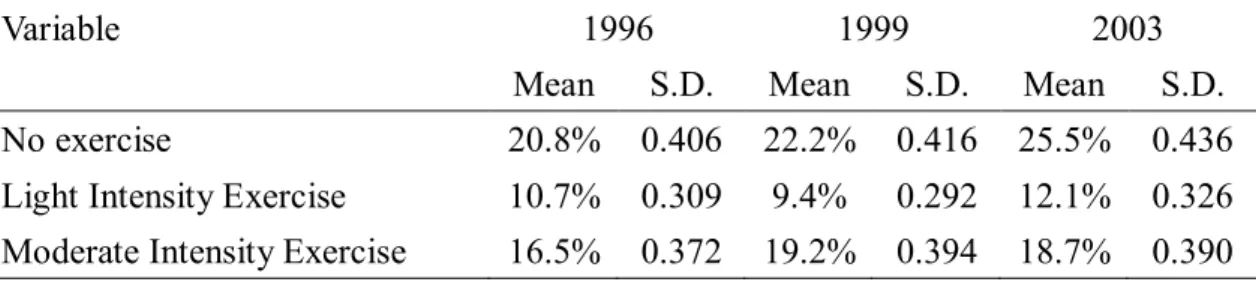

Table 3 Distribution of depression by exercise type ... 23

Table 4 Sample statistics ... 25

Table 5 Estimation of continuous CESD score... 34

Table 6 Estimation of the depression equation ... 35

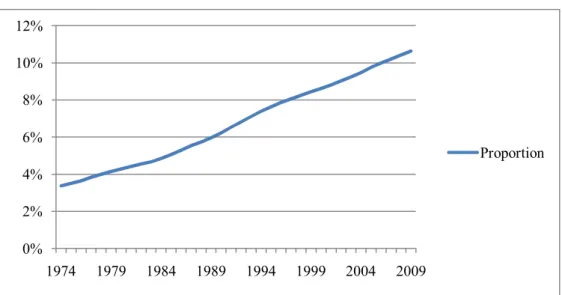

List of Figures Figure 1 The annual proportion of Taiwanese elderly aged 65 or over ... 2

Figure 2 The relationship between exercise intensity and affective benefits ... 11

1

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Motivation

In the past few decades, one of the most significant demographic changes in

Taiwan is the increase in the proportion of the old population. Similar to other

developed and developing countries, Taiwan has experienced a decline in fertility and

mortality rates, which result in a faster process of demographic transition and higher

proportion of older population. To understand the increase in old population in recent

decades, we present the annual proportion of Taiwanese elderly aged 65 or over based

on a statistical report by Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics in

Taiwan (Figure 1). It shows that the proportion of the elderly has increasingly risen and

tripled from 3.4% in 1974 to 10.6% in 2009. Due to the considerable proportion of the

old population, Taiwan is now facing an immense challenge on both social and health

care service.

2

Figure 1 The annual proportion of Taiwanese elderly aged 65 or over

The health care for the elderly has become an important issue in public health

policies, because elderly are more vulnerable to functional transitions than their younger

cohort, which result in a higher hospital use and medical cost (Mor et al. 1994). In

addition to functional disability, mental disorders such as depression among old age

population have also gained increasing prominence. It has been widely recognized that

depression is one of the most common mental disorders among the elderly.

Epidemiological studies have also shown a high rate of prevalence in older adults

among many countries. For example, the estimated prevalence of depression was 33.5%

for Japanese community-dwelling elderly (Wada et al. 2004). Another study raised the

same alarm in Taiwan, Chong et al. (2001) studied 1,500 elderly aged 65 or over in

three communities and found the prevalence of mental illness was 37.7%. This causes

growing concern because depression can substantially reduce quality of life

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

1974 1979 1984 1989 1994 1999 2004 2009

Proportion

3

(Doraiswamy et al. 2002) and cause serious suicide problem (Conwell, Duberstein and

Caine 2002; Wærn et al. 2002). Furthermore, previous researches have documented that

individuals with depression have higher medical care utilization and cost, which yield a

heavy social and economic burden to society (Chan et al. 2006; Sobocki et al. 2007).

An increasing number of studies have identified the potential determinants of

mental health. Among all of the other factors, regular exercise has been shown to have

positive influence on individual's mental well-being. However, the optimal patterns (e.g.

intensity, frequency and duration) of exercise for elderly are still at best inconclusive.

Furthermore, it is crucial to distinguish the intensity of exercise for older adults. Unlike

the general population, elderly health is sensitive to the exercise intensity because too

much exercise will cause adverse health impacts and lower degree of exercise makes

little effect on their health. Since little evidence has been provided regarding the

relationship between exercise intensity and mental health of the elderly, this paper aims

to fulfill the knowledge gap by investigating the optimal intensity of exercise for elderly

health.

1.2 Objective

4

The objective of this study is to examine association between the intensity of

exercise and mental health among the elderly in Taiwan. In addition to exercise, we also

control for family, socioeconomic, health status, lifestyle and social support

characteristics. Several special features may set our study apart from previous studies.

First, in contrast to the small-scale random survey among specific groups, a large-scale

national representative sample of elderly in Taiwan was used. Second, a panel data is

constructed and used for controlling for the individual fixed effect to explore the

relationship between exercise and mental health of the elderly. Additionally, unlike the

epidemic or public studies which usually relied on the qualitative or descriptive analysis,

this study aims to quantify the associations between exercise and mental health.

1.3 Organization

This paper is structured as follows: in Chapter 2 we introduce old age depression

and review previous literatures that have examined the impact of exercise on mental

health. Details of data, definitions of the variables and corresponding sample statistics

are provided in Chapter 3. In Chapter 4 we outline the statistical approach and

econometric models. Chapter 5 presents our estimation results that compare

performance of exercise intensity with related determinants, and finally conclusions are

drawn in Chapter 6.

5

Chapter 2 Literature Review

In this chapter, we first review the main theme of depression in late life and then

review the literatures that have attempted to examine the association between exercise

and mental health. The intensity of exercise is expatiated in section 2.3. As indicated,

considerable evidence had been shown exercise can improve individual mental health

and reduce depressive symptoms.

2.1 Depression in late life

Depression is a variety of psychiatric symptom that reflects individual mental

health conditions such as sadness, loneliness and negative self-concept (see Beck and

Alford 2009). In late life, the prevalence of clinical relevant depressive symptoms has

been reported to a wide range from 7.2% to 49% across countries (Djernes 2006). For

example, epidemiological studies on elderly aged 65 or above have reported different

prevalence rates. Prince et al. (1997) conducted a survey of all residents of an electoral

district in London and found that 17% elderly reported pervasive depression. On the

other hand, a higher prevalence of depression can be found in Wada et al. (2004) who

estimated the prevalence of depression was 33.5% for Japanese community-dwelling

6

elderly.

Depression can lead to both physiological and psychological disorders. For

example, Jaffe, Froom and Galambos (1994) compared depressed and non-depressed

elderly patients and found that patients of depressive symptoms had more functional

impairment. The reduction in quality of life can also be attributed to depression.

Doraiswamy et al. (2002) examined 100 elderly with depression and found that

depressed elderly showed a significant reduction in quality of life. In addition, previous

researches have documented that the economic costs of depression had become a heavy

social burden to society. Chan et al. (2006) found that the economic burden of

Taiwanese adult depression rose from US$ 93 million in 2000 to US $140 million in

2002. In Sweden, the cost of depression has doubled from 1997 (€ 1.7 billion) to 2005

(€ 3.5 billion) due to sick live and early retirement (Sobocki et al. 2007).

With the increasing prevalence of depression among old population, researchers

have examined the association between potential determinants and depression. For

example, researchers have consistently indicated that volunteer work is beneficial to

mental health for elderly (Musick and Wilson 2003). Socioeconomic status (SES) is also

important for depression, especially among lower SES elderly. Using cross-sectional

data from Dutch elderly, Koster et al. (2006) found lower SES is a strong predictor of

depression. In addition, regular exercise has been shown to improve individual mental

7

well-being. We will review the related literatures shortly.

2.2 An overview of exercise and mental health among elderly

Over the recent decades, the association between exercise and mental health has

caught increasingly attention. It is of great concern whether exercise is beneficial to

individual psychological well-being. Researchers addressing this issue have

continuously conducted experimental controlled trials as well as observational analysis

that attempted to test its validity (e.g. Mather et al. 2002; Ruuskanen and Ruoppila 1995;

Kritz-Silverstein, Barrett-Connor, and Corbeau 2001).

Most of researchers have consistently agreed the advantage of exercise in terms of

mental health and depression. For example, Mather et al. (2002) used a randomized

controlled trial to study the effects of exercise on older adults. They randomized the 86

patients aged 53 and over to attend either exercise classes or health classes for 10 weeks,

and found that participants in exercise group have a significant reduction in depression

than those in health classes group. Similar evidence can be found in observational

studies. Using a community-based sample in southern California, Kritz-Silverstein,

Barrett-Connor and Corbeau (2001) examined cross-sectional and prospective

8

association between exercise and depression mood of older people. They found that

exercise was significantly negative associated with depression.

In particular, to prevent the elderly from mental illness, researchers have further

compared the efficiency between exercise and standard anti-depression medication

(Babyak et al. 2000; Blumenthal et al. 2007). Babyak et al. (2000) studied how regular

exercise affects the 156 elder patients aged 50 and over with major depression. They

distributed the patients into three groups: exercise group, medication group and

combined therapies group. After 16 weeks of exercise treatments, participants in

exercise group exhibit a significant reduction in depression as those with medication

only and those with combined therapies. The remission rates of depression were 60%,

66% and 69% respectively. The authors also recommended regular exercise as an

alternative treatment instead of antidepressant. On the contrary, some studies showed

opposite results. For instance, Emery and Gatz (1990) showed little change in

psychological well-being for older adults after a 12-week aerobic exercise program.

Researchers are also interested in the mechanisms of antidepressant effect of

exercise. This important issue is also open to more debate. Several hypotheses have

been proposed to explain the anti-depression effect (see Craft and Perna 2004). For example, the endorphin hypothesis assumes that β-endorphins are increasingly released

after exercise which yields an overall enhancement of well-being.

9

Although the mechanisms of antidepressant effect are not transparent, the

relationship between exercise and mental health has been well established, and

researchers have generally drawn a similar conclusion that exercise can lead to better

mental health.

2.3 Intensity of exercise

With growing evidence that exercise is positive associated with mental health, it is

now important to focus further on the relationship between exercise and mental health.

For example, factors such as intensity, frequency and duration play significant roles in

determining individual mental health (see Teychenne, Ball, and Salmon 2008). Among

the factors, the intensity of exercise has come under spotlight in recent years. In addition

to the benefits of exercise, exercise can also result an insignificant change or even

impaired mental health. Therefore, it is important to study the relationship between

exercise intensity and mental health.

There are several ways to measure exercise intensity. For randomized controlled

experiments, the common measurements include heart rates, percentage of maximum

oxygen consumption (Hiilloskorpi et al. 2003) and energy expenditure (Dunn et al.

10

2005). However, supervised exercise training and such intensity measurements are

generally not feasible in observational studies. An alternatively method is to use

metabolic equivalent (MET) values to measure exercise intensity (Ainsworth et al.

2000). The MET values are defined by the levels of breathing efforts across a variety of

physical activity. For example, the MET value is assigned to 2.5 or 3.3 if respondents do

slow walking with “no change in breathing pattern” or “breath somewhat harder than

normal”. To identify the optimal level of intensity, researchers have stimulated a number

of papers to examine how exercise intensity affects mood states.

Since the 1990s, the shape of relationship between exercise intensity and affective

benefits has been found as approximated an inverted-U as displayed in figure 2

(Acevedo and Ekkekakis 2006; Ekkekakis, Hall and Petruzzello 2005). The traditional

inverted-U hypothesis has sketched the idea that moderate exercise is the optimal

intensity level for overall affective benefits; low intensity exercise may insufficiently

cause significant affective changes while high intensity exercise may cause insignificant

or aversive changes (Kirkcaldy and Shephard 1990; Ojanen 1994). Some researchers

have found similar results in normal population. One of the first studies was Moses et al.

(1989), who compared how different intensities of aerobic training affected mood and

mental well-being. After the training program, they found mood improvements were

significantly associated with the moderate exercise rather than high intensity. Similar

11

evidence can be found in Dunn et al. (2005). The authors showed that the degree of

reduction in depression was varied with different exercise intensities; the moderated

exercise was more effective than light exercise.

Figure 2 The relationship between exercise intensity and affective benefits

Despite the popularity of the hypotheses, considerable different findings are

revealed in extent literatures. For example, Wise et al. (2006) found that vigorous

intensity exercise was more strongly association with reduction in depression than light

intensity exercise. Moreover, Landuyt et al. (2000) examined short-term moderate

exercise effects among 82 university students and found that some participants reported

improvement in mood state but some reported a decline.

While the link between exercise intensity and mental health has been examined for

general population, there are only few papers focusing on older population (Lampinen,

12

Heikkinen, and Ruoppila 2000). Furthermore, these studies have report inconsistent

results. Some reports have argued that both moderated and high intensity exercise could

improve individual mental health. For example, using a randomized controlled trial for

357 elderly aged 50-65, King, Taylor and Haskell (1993) found that both moderate and

high intensity exercise reduced depression. The same conclusion can be found in

Ruuskanen and Ruoppila (1995) who studied the association between physical activity

and psychological well-being among the 1844 elderly in Finland. Based on a

cross-sectional study, they found that both moderated and intense exercise could reduce

depressive symptoms. On the other hand, Singh et al. (2005) studied the clinically

depressed elder patients and showed that high intensity progressive resistance training

(PRT) was more effective for depressive symptoms and quality of life than low intensity

PRT. Conversely, Lindwall et al. (2007) studied 860 Swedish suburb-dwelling elderly

and found that reduction in depression was associated with light exercise for women

only and strenuous exercise for men only.

There was another study which used longitudinal data to examine the long-term

relationship between changes in intensity of exercise and depressive symptoms

(Lampinen, Heikkinen, and Ruoppila 2000). Participants aged 65 or above were first

interviewed in 1988 and resurveyed 8 years later. The authors compared current and

past intensity of exercise and categorized changes in intensity of exercise as a predictor

13

of depressive symptoms. In general, participants who reduced their exercise intensity

had more depressive symptoms than their counterparts.

In summary, we provide studies examining the relationship between exercise

intensity and depression in Table 1.

2.4 Summary

Although evidence is growing on the effectiveness of exercise on depression, there

are several limitations in existing literatures as we reviewed in previous sections. First,

small selected random sample was commonly used in intervention studies. Second,

findings based on cross-sectional studies are not suitable to explore the causal

inferences between exercise and mental health. Third, diverse definition or classification

of exercise intensity may provide different implications for policy recommendation.

Fourth, results from young adults cannot be directly applied without any modification to

the older population. At these points, little is known about how different intensity of

exercise affects the elderly mental health.

14

Table 1 Summary table of studies examining the relationship between exercise intensity and depression

Author Year Sample Data type Age Intensity Relationship with depression

Dunn et al. 2005 80 adults Randomized control trial 20-45 Moderate -

Light 0

King, Taylor and Haskell 1993 357 elderly Randomized control trial 50-65 Moderate -

High -

Moses et al. 1989 109 adults Randomized control trial 18-60 Moderate -

High 0

Lampinen, Heikkinen and Ruoppila 2000 663 elderly Longitudinal 65 or over Decreased + Remained 0 Increased 0

Lindwall et al. 2007 860 elderly Cross-sectional 60-96 Light - (Women only)

High - (Men only)

Ruuskanen and Ruoppila 1995 1,244 elderly Cross-sectional 65-84 Moderate -

High -

Singh et al. 2005 60 elderly Randomized control trial 60 or over Light -

High -

Landuyt et al. 2000 82 university students Randomized control trial 18-22 Moderate some + and some -

Wise et al. 2006 35,224 women Cross-sectional 21-69 Light 0

High -

Note: +, 0 and - represent positive, no and negative relationship respectively.

15

Chapter 3 Data

3.1 Source

To examine the impact of exercise intensity on mental health for Taiwanese elderly,

we use data from Survey of Health and Living Status of the Elderly (SHLSE). The

SHLSE is a longitudinal survey conducted by the Department of Health in Taiwan. The

main objective is to explore the role of elderly in the context of family structure,

economic status, health status, social support and related issues for rapidly aging

population. Therefore, detailed information on socio-demographic characteristics, health

status, employment and other topics are collected.

The baseline survey began in 1989 covered 4,412 elderly aged 60 or over drawn

from 56 communities. A total of 4,049 elderly were successfully interviewed and

achieved a response rate of 92%. Since then, the respondents were traced and

resurveyed in 1993, 1996, 1999 and 2003. However, over one quarter of respondents

had passed away in 1996 and only 2,669 elderly were re-interviewed. In order to

maintain a representative sample of Taiwanese elderly, a younger cohort aged 50-66 was

included in 1996. The survey also added a new sample of elderly aged 50-56 in 2003.

With the appropriate sampling design, the sample is nationally representative for the

middle and elderly population in Taiwan. Further details of the SHLSE can be found in

16

the survey documentations (see Taiwan Department of Health 2008).

Although the survey offers rich information for Taiwanese elderly, the survey

design differs slightly across years. For example, there were 10 items in the

questionnaire for measuring individual mental health in 1996, 1999 and 2003, while

another 17 items and 5 items were included in the questionnaire in 1989 and 1993

respectively; information about exercise behavior was not included in 1989 and 1993,

while it was included in 1996, 1999 and 2003. In order to maintain the consistency of

the data, we only used the last three waves of the survey without the newly added

sample in 2003 in our empirical analysis.

After deleting observations with missing values on key variables in each survey

period, there are 3,564, 3,430 and 3,312 observations in 1996, 1999 and 2003

respectively. Individuals who were not surveyed in entire three periods are also

excluded. The final balanced panel data comprises 1,825 elderly individuals in each

year.

3.2 Measures of dependent variables

The dependent variable in this study is the mental illness of the elderly. Consistent

with the empirical specifications in the previous studies and to show the robustness of

17

our findings, three differential types of the dependent variables are specified. The first

dependent variable, a continuous measure of mental illness, is measured using a 10-item

short version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which

is one of the most valuable tools for helping identify an individual at-risk for depression

(Beekman et al. 1997). The measurement has been used to examine elderly mental

illness (e.g., O’Hara, Kohout, and Wallace 1985) and found adequate validity in Chinese

elderly population (Boey 1999). In SHLSE, 10 questions about mood swings were

included to reflect individual’s mental health condition. Each respondent was asked to

rate each question with a 0-3 scale point whether they had experienced a variety of

symptoms during the past week (e.g. “feel sad,” “feel lonely,” “feel happy”). We then

reversed codes of the positive items, and summed them up with the other 8 items as the

CES-D score. As result, the total points of CES-D scores range from 0 to 30, with

higher scores indicating worse mental health.

Although the CES-D score is widely used for many of the studies, it is commonly

seen that a certain proportions of respondents report zero scores of all of the questions,.

That is, they report no related depressive symptoms for all of the requested questions. In

this case, treating these groups of respondents the same as others may be not appropriate.

Econometrically, this problem is consistent with the censoring problems of the observed

data. To accommodate this issue, we define a censored CES-D score by treating those

18

who have zero scores of the overall CES-D score differently. In what follow, a tobit

model is used to estimate this type of the dependent variable.1

The third dependent variable is a binary variable measuring whether the individual

has depression or depressive symptoms. Because the survey didn’t include depression in

individual’s history of disease, we introduce a suggested cut-off point at CES-D ≥ 10 to

identify the elderly with clinically relevant levels of depression. This optimal cut-off

point was first established and analyzed by Andresen et al. (1994), and has been widely

used by many studies in examining elderly depression (e.g., Schulz et al. 2000).

3.3 Measures of independent variables

Exercise intensity measurement

All respondents were firstly divided into non-exercisers (no exercise) and

regular-exercisers (exercise at least once per week). Because further information of

exercise intensity was also obtained for regular-exercisers including duration, sweat rate

and breathing effort. Among the indicators, breathing effort has been used to measure

the intensity of exercise in another context (Wai et al. 2008).2 Because detailed

1 In Seplaki et al.(2006), they argued that a special treatment has to be made to disentangle those who report zero overall CES-D scores and those who don't. We follow their approach to make a distinction between those two types of respondents.

2 See Wai et al. (2008) for detailed information of using MET to measure exercise intensity.

19

information on types of exercise (e.g. walking, jogging and swimming) was not

collected in the survey, to calculate the metabolic equivalent (MET) values as used for

clinical or medical studies is not available. Instead, we used personal perceived

breathing level as an approximate indicator of exercise intensity. Three possible answers

of breathing effort were “no change in breathing”, “slight increase in breathing” and

“significant increase in breathing”. Considering elderly are prone to change in breathing

pattern after exercise and less likely to have vigorous exercise due to functional

transition, we classified those who report “no change in breathing” as having light

exercise, and the remaining respondents were classified as doing moderate exercise

among those report regular exercise at least once per week.3 To sum, three differential

types of exercise intensity are specified: for those who don't exercise at least once per

week, those who usually work out with light intensity; and those who usually work out

with moderate or even stronger intensities.

Other Independent Variables

In addition to exercise intensity, we also controlled for other potential determinants

that are related to mental health. Drawing on previous studies on mental health among

elderly, the potential determinants included family characteristics, socioeconomic

characteristics, health status, lifestyle and social support (see Djernes (2006) for a

3 There are less than 2% respondents reporting breathing much harder than normal.

20

review).

Family characteristics include marital status and whether an individual lived alone.

The socioeconomic variables include employment and family income (combined with

income of the respondent and his or hers spouse if present). In SHLSE, two questions

were asked related to family income. The first question asks each respondent to report

their family income per month if they can accurately indicate the absolute value, while

the second question asks each individual to check the approximate categories of their

family income if they don't have precise answer of their family income. In what follow,

the family income variable was created for those who reported the absolute values and

used the midpoint for each of income category for those who only check their income

status.

Similar to the definition of Seplaki et al. (2006), health status is assessed by an

index of mobility impairments. Respondents were asked to use a 0-to-3 scale to rate the

hardship for each activity. Selected activities included standing continuously for 15

minutes, squatting, raising hands overhead, grasping or turning objects with fingers,

lifting a 12kg object, running a short distance (20-30m) and climbing 2-3 flight of stairs.

The resulting mobility impairment scale ranges from 0 to 21 with higher scores

indicating more mobility limitation.

Two lifestyle indicators, drinking and smoking, of each individual are also

21

specified. Both drinker and smoker are coded as a binary variable reflecting

respondent’s self-reported current smoking or drinking behaviors. Since empirical

evidence has shown that social networking is also crucial to determine the mental health

of the elderly (Blazer 1983; Musick and Wilson 2003), we define two variables related

to social activities or social support. The first variable indicates the social score, which

is defined based on the number of community each respondent participates (e.g.

political party and religious community). The second variable reflects the volunteer

works which each individual involved. A binary variable of volunteer work is defined to

indicate whether the respondent offers to perform a social service voluntarily.

3.3 Sample Description

To highlight the differences in mental health by different intensities of exercise

degree, we report the mean CES-D scores by exercise intensity in each year in Table 2.

As exhibited, among three exercise groups, non-exercisers have the highest CES-D

scores in each year. Moreover, their mental health has worsened during the 3 survey

periods. The average CES-D score was 5.69 in 1996 and 5.79 in 1999 and increased to

6.60 in 2003. On the other hand, regular-exercisers had a better mental health condition.

Moreover, substantial differences in CES-D scores are evident among different types of

22

exercise intensities: light intensity exercisers had lower CES-D scores by 1-2 points

than moderate exercisers. The CES-D scores were 3.82 (4.68), 3.37 (5.34) and 3.97

(4.92) in 1996, 1999 and 2003 respectively for light intensity exercisers (moderate

exercisers).

Table 2 Mean score of mental illness by exercise type

Variable 1996 1999 2003

Mean S.D. Mean S.D. Mean S.D.

No exercise 5.690 5.879 5.787 6.089 6.596 6.571

Light Intensity Exercise 3.816 4.635 3.370 4.544 3.969 4.788 Moderate Intensity Exercise 4.684 5.363 5.336 5.512 4.915 5.311

We also report the distribution of depression by exercise intensity in each year in Table

3. The prevalence of depression for light intensity exercisers was 10.7%, 9.4% and

12.1% in each year. Moderate intensity exercisers have a higher proportion of

depression, 16.5%, 19.2% and 18.7% of the elderly have depression in 1996, 1999 and

2003 respectively. Non-exercisers have the highest proportion of depression; the

corresponding proportions are 20.8%, 22.2% and 25.5%.

23

Table 3 Distribution of depression by exercise type

Variable 1996 1999 2003

Mean S.D. Mean S.D. Mean S.D.

No exercise 20.8% 0.406 22.2% 0.416 25.5% 0.436

Light Intensity Exercise 10.7% 0.309 9.4% 0.292 12.1% 0.326 Moderate Intensity Exercise 16.5% 0.372 19.2% 0.394 18.7% 0.390

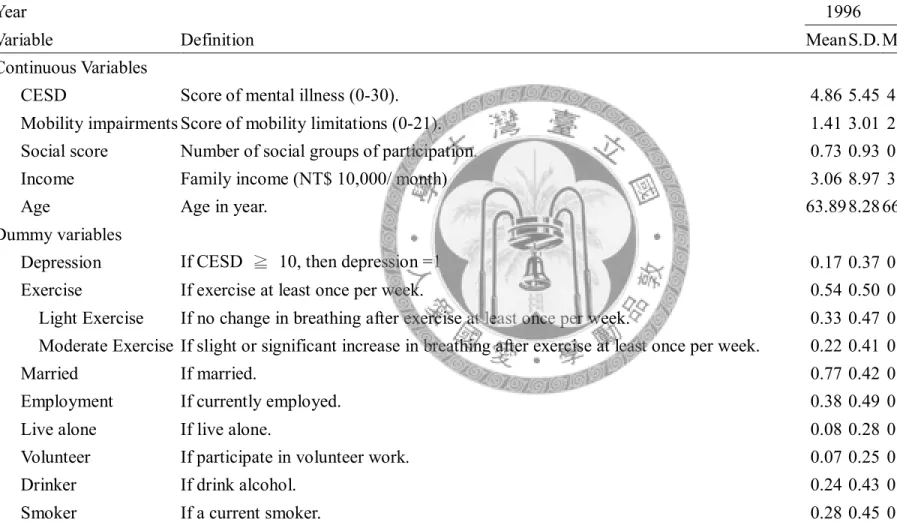

Detailed definitions and sample statistics of each variable are presented in Table 4.

In our sample, the mean age of the elderly was about 64 in 1996. The mean CES-D

scores of the elderly were 4.86, 4.74 and 5.09 in 1996, 1999 and 2003 respectively; the

corresponding prevalence of depression were 17%, 16% 18%. The popularity of

exercise has increased, in 1996 only 54% elderly did exercise regularly, while in 2003,

almost 70% elderly did exercise regularly. Comparing the percentage of exercise for

various intensities, we find that both light and moderate exercise has increased 6% from

1996 to 2003, and the moderate exercise rate is roughly 10-15% which is lower than the

proportion of the light exercise.

About 77% of the elderly were married in 1996 and 8% reported that they were

living alone. In 2003, the percentage of married elderly has decreased to 68%, and 11%

report they were living alone. Employment rate in our sample has declined

tremendously during the survey periods. While nearly 40% of the elderly were currently

employed in 1996, only 18% reported being employed in 2003. The average family

24

income per month was about NT$ 30,000, 35,000 and 26,000 in 1996, 1999 and 2003

respectively.

The mobility limitations were low for elderly across year. The mean scores of

mobility impairments were less than 4 in three survey periods. Drinking and smoking

were highly prevalent among older adults. 24% (28%), 29% (25%) and 26% (21%) of

the elderly were drinker (smoker) in 1996, 1999 and 2003 respectively. Social

participation rate was quietly low in entire survey periods. The average number of social

groups of participation was less than 1. In addition, the rate of participation in volunteer

work was less than 10%.

25

Table 4 Sample statistics

Year 1996 1999 2003

Variable Definition Mean S.D. Mean S.D. Mean S.D.

Continuous Variables

CESD Score of mental illness (0-30). 4.86 5.45 4.74 5.50 5.09 5.68

Mobility impairments Score of mobility limitations (0-21). 1.41 3.01 2.04 3.42 3.48 4.69 Social score Number of social groups of participation. 0.73 0.93 0.79 0.94 0.66 0.95

Income Family income (NT$ 10,000/ month) 3.06 8.97 3.48 4.49 2.57 3.40

Age Age in year. 63.89 8.28 66.89 8.28 70.89 8.28

Dummy variables

Depression If CESD ≧ 10, then depression =1 0.17 0.37 0.16 0.37 0.18 0.39

Exercise If exercise at least once per week. 0.54 0.50 0.63 0.48 0.67 0.47

Light Exercise If no change in breathing after exercise at least once per week. 0.33 0.47 0.39 0.49 0.39 0.49 Moderate Exercise If slight or significant increase in breathing after exercise at least once per week. 0.22 0.41 0.24 0.43 0.28 0.45

Married If married. 0.77 0.42 0.74 0.44 0.68 0.47

Employment If currently employed. 0.38 0.49 0.29 0.46 0.18 0.38

Live alone If live alone. 0.08 0.28 0.09 0.29 0.11 0.31

Volunteer If participate in volunteer work. 0.07 0.25 0.09 0.29 0.07 0.26

Drinker If drink alcohol. 0.24 0.43 0.29 0.45 0.26 0.44

Smoker If a current smoker. 0.28 0.45 0.25 0.44 0.21 0.41

* The balanced panel data include 1,825 respondents in each year.

26

Chapter 4 Methodology

The main objective of this research is to study the relationship between intensity of

exercise and mental health. Utilizing a panel data from SHLSE, the fixed-effect model

is estimated. We will begin the discussion of this section by introducing the formal

specification of each econometric model, and then we pay special attention on

fixed-effect Tobit and fixed-effect probit models in section 4.2 and 4.3.

4.1 Econometric specifications

To reach our goal, several econometric issues need to be tackled. First, it is

necessary to control for unobserved heterogeneity problem to address the effects of

exercise on mental health. Because there are likely to be some unobservable

components which jointly determine both exercise behavior and mental health, without

controlling for such effects will lead to be biased estimations. For instance,

unobservable personal characteristics, such as personality and motivation, may be

related to mental health. This would be true if those who are more introverted or less

motivated had less chance to work out and a higher depression tendency.4 Due to the

4 If such variables are unobserved, they will be captured by random error term, which results in a

27

lack of valid and convincing instruments of these variables, we use the

individual-specific fixed effects model to control for the effects of unobserved

heterogeneity on mental health of the elderly. Second, it is a need to correct the

censoring problem which violates the basic assumption of the least-squared estimation.

If a specific individual was not depressed at all, the estimations of the CES-D equations

will be zero. Therefore, treating those groups of people as the same as other groups of

respondents are not appropriate. Third, since our third dependent variable is classified

into two classes, it is reasonable to use a binary regression model rather than ordinary

least squares estimation.

In a panel data model, a popular estimation method is to use fixed-effect model.

Unlike the general linear panel data model, the random error term uit is decomposed to

individual-specific effects and an idiosyncratic error in fixed-effect model.5 Using a

fixed-effect estimation, we are able to control for all unobserved time-invarying

individual-specific factors that are related to mental health.6

Assuming that the individual's continuous CES-D score of mental health (yit) is

determined by a linear combination of exercise behavior and other time-varying

independent variables, the effect of exercise intensity on mental health can be estimated

correlation between exercise variables and random error term.

5 The general linear panel data model is specified as: yit=α+xitβ+uit, where yit and xit are dependent variable and independent variables respectively; uit is a random error term for individual i at time t.

6 In contrast to fixed-effect model, the random-effect model assumes that vi are random variables.

28

using the following fixed-effect OLS model:

_ β _ β β ,

it it M it L it i it

y M exercise L exercise x v

(1)where the subscript i and t refer to individual and time period respectively; M_exerciseit

and L_exerciseit represent the indicators of moderate and light exercise intensities

respectively. The reference group is those who don't work out regularly at least once per

week. Thus, the parameters βM and βL represent the effects on mental health score of

each corresponding group compared to the reference group; xit is a vector of other

independent variables with corresponding vector of the parameters β; vi is

individual-specific time-constant effect and εit is assumed to be a mean-zero,

constant-variance random error term that is uncorrelated with the independent variables.

4.2 Fixed-effect Tobit model

About 28% people reported zero CES-D scores in each year. Due to the censoring

nature of the second defined dependent variable, a fixed effect Tobit model is specified

with the following equation. In our sample,

* _ β _ β β ,

it it M it L it i it

y M exercise L exercise x v

(2) where y*it is a unobservable latent variable of the censored CES-D score of eachindividual's mental health; M_exerciseit, L_exerciseit, xit, vi and εit are defined as above.

29

Instead of observingy*it, we observe yit:

* *

if 0 0 otherwise.

it it

it

y y

y

(3)

The estimators can be obtained by using maximum likelihood method with the

following likelihood function:

1

1 1

α α

1 1 ,

it it

d d

N T

it it i it i

i t

y z v z v

L

(4)where dit is an indicator that equals 1 (0) if yit > 0 (≤0); Φ(.) and (.) are cumulative

density function (CDF) and probability density function of standard normal distribution

respectively; note that we use z itα here to represent whole independent variables for

convenience.

As indicated in Greene (2003), the quantitative effects of the exogenous variables

are better presented by the marginal effects: which measure the changes in exogenous

variables on the conditional expected means of the mental health scores. Note that the

calculation of marginal effects is not trivial in nonlinear models, because taking direct

partial derivatives are not applicable for exogenous dummy variables (Greene 2003).

The appropriate formulates of the marginal effects for continuous and binary

independent variables are presented below. Here we distribute the independent variables

into a specific dummy variable (dit) and all the other variables (cit) for convenience.

Given the conditional mean function:

30

β β

[ , ] [ ] [ β β ]

( β β ),

it c it d i

it it it it c it d i

it c it d i

c d v

E y c d c d v

c d v

(5)

the marginal effects are

[ , , ] β β

β [ ]

it it it i it c it d i

TC c

it

E y c d v c d v

ME c

(6)

for continuous variables and

1 0 1 0 1[ , 1] [ , 0]

β β

TD it it it it it it

it c i it it it it d it

ME E y c d E y c d

c v

(7)

for each dummy variable, where 1it and

are evaluated at

it1 (citβcβd vi) /

;0

it and

are evaluated at

it0 (citβcvi) /

(Greene 2004). The corresponding standard errors are computed by delta method (Greene 2003).4.3 Fixed-effect probit model

Our third dependent variable is a binary indicator of depression which is defined

using the appropriate cut-off point (i.e. CES-D score ≥ 10 for depression; and 0

otherwise). If the unobserved latent variable is indicated by the continuous variable Iit

*,

we incorporate the same independent variables discussed above and use the following

fixed-effect probit model:

* _ β _ β β .

it it M it L it i it

I M exercise L exercise x v

(8)31

Given the observed rule if a binary indicator Iit = 1 for Iit* > 0:

1 if * 0 0 otherwise.

it it

I

I

(9)

The estimators can be obtained by using maximum likelihood method with the

following likelihood function:

11 1

α 1 α ,

it it

d d

N T

it i it i

i t

L z v z v

(10)where dit is an indicator that equals 1 (0) if Iit =1 (=0); Φ(.) is CDF of standard normal

distribution.

The mean function for fixed-effect probit model is

[ it it, it] ( itβc itβd i).

E I c d

c

d

v

(11)The corresponding marginal effects for fixed-effect probit model are

[ , , ]

β ( β β )

it it it i

PC c it c it d i

it

E y c d v

ME c d v

c

(12)

for continuous variables and

[ , 1] [ , 0]

( β β ) ( β )

PD it it it it it it

it c d i it c i

ME E y c d E y c d

c v c v

(13)

for each dummy variable (Greene 2004).

32

Chapter 5 Results

In this chapter, we examine the effect of exercise intensity and related variables on

mental health and depression. We begin our discussions of our results by presenting for

the case of the continuous and censored specifications of the mental health dependent

variables. The estimation results for our third binary dependent variable, whether each

individual is defined as depression or not, are exhibited in section 5.2.

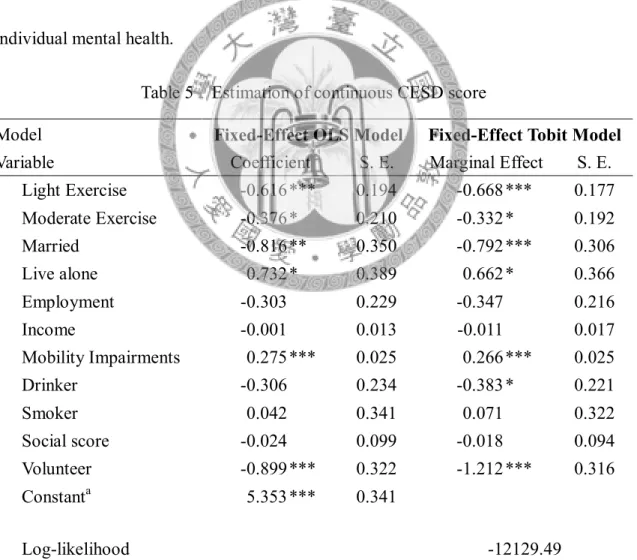

5.1 The determinants on mental health

The estimation results of the fixed-effect OLS and fixed-effect Tobit model are

presented in Table 5. We report two sets of regression models: the first part is the results

of the fixed-effect OLS model, and the second part is the marginal effect of the

fixed-effect Tobit model. The estimated coefficients of the Tobit model are not reported

because they show no meanings of the magnitudes or quantitative effects of the

exogenous variables on mental health. In general, the estimated coefficients and implied

marginal effects are consistent for the two models, though quantitative differences do

observed.

The results, most noticeably, indicated that regular exercise dose significantly

improve elderly mental health. However, the intensity of exercise plays an important

33

role in determining mental health. In particular, evidence shows that the effect of light

exercise is more substantial than the effect of moderate exercise. The estimates indicate

that comparing to non-exercisers, light intensity exercisers lead to a lower CES-D score

by 0.62 point in the OLS model, and by 0.67 point in the Tobit model. On the other

hand, the effects are subtle for moderate intensity exercisers; they have a lower CES-D

score by about 0.3-0.4 point in these two models. This improvement is roughly half as

long as light intensity exercisers. One possible interpretation is that moderate intensity

exercise may be too much for maintaining the necessary health condition of the elderly.

Therefore, moderate intensity exercise is not as effective as light intensity exercise on

elderly health.

Among the other factors, family characteristics are also significantly associated

with mental health among the elderly. First, evidence points to a positive relationship

between marital status and mental health. Elderly with a spouse or partner have better

mental health by about 0.8 point in these two models. Second, living alone is negatively

associated with mental health. The estimated marginal effect is 0.66 in the Tobit model,

and a slightly higher effect is found in the OLS model (0.73). Health status also plays an

important role on mental health. Both OLS and Tobit results indicate that an additional

score of mobility impairment increases the CES-D score by 0.27 point.

Regarding to the two lifestyle indicators, current drinkers are more likely to have

34

better mental health, though the effect is only significant in the Tobit model. The

marginal effect of drinker implies that the CES-D scores of drinkers are 0.38 compared

to non-drinkers. As to the roles of social support, interestingly, we find a strong and

significant relationship between volunteer work and mental health. The estimated

coefficient in the OLS model shows that the CES-D scores of volunteers are reduced by

approximately 0.9 point. The quantitative size of this effect (1.2) is much larger in the

Tobit model. This likely reflects that volunteer involvement is beneficial to improve the

individual mental health.

Table 5 Estimation of continuous CESD score

Model

Fixed-Effect OLS Model Fixed-Effect Tobit Model

Variable Coefficient S. E. Marginal Effect S. E.

Light Exercise -0.616 *** 0.194 -0.668 *** 0.177 Moderate Exercise -0.376 * 0.210 -0.332 * 0.192

Married -0.816 ** 0.350 -0.792 *** 0.306

Live alone 0.732 * 0.389 0.662 * 0.366

Employment -0.303 0.229 -0.347 0.216

Income -0.001 0.013 -0.011 0.017

Mobility Impairments 0.275 *** 0.025 0.266 *** 0.025

Drinker -0.306 0.234 -0.383 * 0.221

Smoker 0.042 0.341 0.071 0.322

Social score -0.024 0.099 -0.018 0.094

Volunteer -0.899 *** 0.322 -1.212 *** 0.316

Constanta 5.353 *** 0.341

Log-likelihood -12129.49

Note: S.E. = standard error. ***, ** and * indicated the significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels.

a STATA reports the constant term as average value of the fixed effects.

35

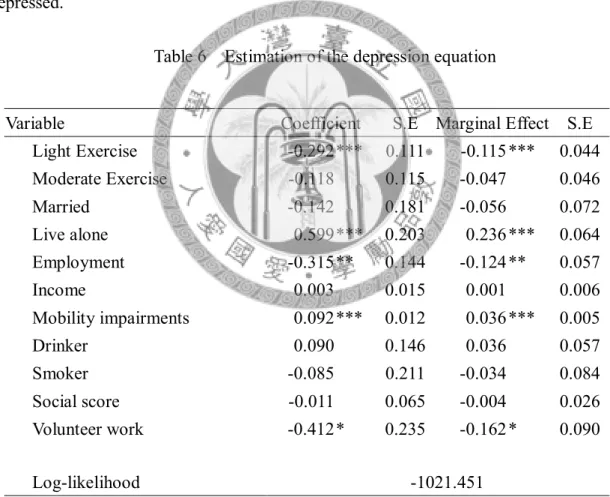

5.2 The determinants on depression

Our third dependent variable, whether the individual has depressive symptoms or

not, is coded as a binary response. The estimates from the fixed-effect probit model are

shown in Table 6. In addition to the estimated coefficients, we also report the marginal

effects to quantify the effects of the exogenous variables on the probability of being

depressed.

Table 6 Estimation of the depression equation

Variable Coefficient S.E Marginal Effect S.E

Light Exercise -0.292 *** 0.111 -0.115 *** 0.044 Moderate Exercise -0.118 0.115 -0.047 0.046

Married -0.142 0.181 -0.056 0.072

Live alone 0.599 *** 0.203 0.236 *** 0.064 Employment -0.315 ** 0.144 -0.124 ** 0.057

Income 0.003 0.015 0.001 0.006

Mobility impairments 0.092 *** 0.012 0.036 *** 0.005

Drinker 0.090 0.146 0.036 0.057

Smoker -0.085 0.211 -0.034 0.084

Social score -0.011 0.065 -0.004 0.026

Volunteer work -0.412 * 0.235 -0.162 * 0.090

Log-likelihood -1021.451

Note: S.E. = standard error. ***, ** and * indicated the significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels.

The results present a notable difference between light and moderate intensity

exercise on the likelihood of being depressed, which is different from the exercise

intensity effects on mental health. In the fixed-effect probit model, moderate intensity

36

exercise is not significant to determine the likelihood of depression, while light intensity

exercise leads to a lower probability of being depressed: 11.5% at the 1% level of

significance. This is a reasonable result, as those moderate intensity exercisers might

receive less benefits from exercise, which results in insufficient efforts to fighting

against depression. The empirical literature is inconclusive on the relationship between

exercise intensity and depression of the elderly. Our result is similar to Lindwall et al.

(2007), who found that light intensity exercise had a strong effect on elderly women, but

differs to Singh et al. (2005), who found high intensity PRT was more effective than low

intensity PRT.

Living alone appears to exert an influence on depression. The estimated marginal

effect indicates that elderly who live alone have a higher probability of being depressed

(23.6%). In addition, working status is associated with depression. Elderly who have a

current job are less likely to suffer from depression. On average, they have 12.4% lower

in probability of being depressed, holding other things constant.

As in mental health equation, health status is also significant in determining

psychological disorders. An additional score of mobility impairment increases the

likelihood of depression by 3.6%. Volunteer work can reduce depression as well. The

estimated marginal effect suggests that volunteers for social activities have a 16.2%

lower in probability of being depressed.

37

Chapter 6 Conclusion

Old age depression has been one of the widely studied topics in public health.

Researchers have examined the association between potential determinants and

depression among the elderly, and have demonstrated that exercise is an effective

treatment for mental illness. Although little attention had been paid to examine the

intensity of exercise on mental health, the findings are still inconclusive. In addition,

few studies are conducted specifically on the elderly population. In this study, we

provide new evidence on the effects of exercise intensities on mental health by using a

longitudinal survey of Taiwanese elderly. A more sophisticated econometric model is

then applied to control for potential unobserved heterogeneity. We also take the issues

of limited dependent variables into account, and use panel version of nonlinear models.

The estimation results indicate that exercise behavior, family characteristics,

socioeconomic status, health status, lifestyle and social support play important roles on

elderly mental health and depression. Most importantly, our estimation results suggest

that exercise be good for mental health of the elderly, but significant difference does

exist in different degree of intensities. In contrast to traditional inverted-U hypothesis

which assumes that moderate intensity exercise is the optimal pattern for positive

affective change, our results indicate that light intensity exercise is much better than

moderate intensity exercise for elderly mental health. In addition, our results also

38

suggest that light intensity exercise decreases the likelihood of depression, while

moderate intensity exercise doesn’t. Some policy implications can be inferred from our

findings for Taiwan’s public health policy. In order to promote mental health and reduce

symptoms of depression among the elderly, it is important to encourage them to exercise

regularly. Furthermore, our results suggest that interventions on psychological outcomes

should focus on exercise intensity. For Taiwanese elderly, light intensity exercise (i.e. no

change in breathing after exercise) is better to enhance elderly mental health.

Although we have investigated the relationship between exercise intensity and

mental health among the elderly, several limitations are revealed. First, because our

exercise intensity measurement is constrained by the data, it may be difficult to

distinguish the effects of exercise intensity on mental health in this study from previous

literatures that used a variety of intensity measurements. Second, both non-response in

sequent survey waves and missing values on key variables contribute to sample attrition

in our panel data, which reduces the sample size and thus reduces precision of estimates.

Third, some interviews were conducted with proxies who were not asked for any of

subjective questions (e.g. self-report health). This may lead to potential sample selection

bias, because it is reasonable to believe those individuals are more likely to be in poor

health and depressed.