Correspondence and requests for reprints:Dr. Chia-Long Lee

Address:Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Cathay General Hospital, No. 280, Sec. 4, Jen-Ai Road, Taipei 106, Taiwan

Identification of Factors That Impact on Patient Satisfaction of Unsedated Upper

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Jung-Pin Chiu

2, Chia-Long Lee

1,3,4, Chi-Hwa Wu

1, Yung-Chih Lai

1, Ruei-Neng Yang

2, and Tien-Chien Tu

1,31

Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Cathay General Hospital, Taipei;

2Shin-Chih, Taiwan;

3

School of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei;

4

School of Medicine, Fu-Jen University, Sinjhuang, Taiwan

Introduction

Todays' esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) has seen an impact and benefits on the diagnostics of gastrointestinal (GI) tract diseases as a result of better endoscopic instrument designs. However, there are still discussions surrounding the question of whether to perform upper GI endoscopy with or

without conscious sedation. The use of sedation has resulted in greater satisfaction from patients and endoscopists

1, though the use of unsedated proce- dure can decrease the risks of patient's morbidity and mortality

2, as well as reduce procedural costs

3. Conscious sedation during endoscopy has gained widespread diffusion and acceptance in the United States, however, in Asia sedation has a relative low

Abstract

This study is designed to validate clinical predictors to patient satisfaction and tolerance for

unsedated upper GI endoscopy in Taiwanese patients. Patients who underwent diagnostic upper GI

endoscopy at Cathay General Hospital, in Taipei, Taiwan from September 2005 to December 2005 were

enrolled. A questionnaire was filled by patient after endoscopic procedure. The clinical predictors for patient

satisfaction were analyzed in this study. A total of 3,087 patients underwent endoscopic examinations

during this period. A satisfactory endoscopy procedure included the male gender (OR= 1.75), advanced

age (OR =1.03), procedure time in the morning (OR =1.58), presence of assistant (OR =1.67), previous

experience (OR =2.16) for upper endoscopy. Unsedated upper GI endoscopy is a feasible, acceptable,

and cost-effective alternative to sedated procedure. It is our suggestion that patients with the above

characteristics had merit in selecting unsedated procedure. ( J Intern Med Taiwan 2009; 20: 359-366 )

Key Words:Satisfaction, Unsedated upper GI endoscopyadoption rate for endoscopy

4, often considering patient's safety and costs over comfort and suitability. The aim of this study is to determine the predictors of satisfaction and tolerance for unsedated upper GI endoscopy. Other studies have previously shown that predictors of tolerance for unsedated upper GI endoscopy can include old age, male gender, decreased pharyngeal sensitivity, and positive outcome of previous endoscopic proce- dures

5,6, though those studies examined only limited and small select groups of patients outside of Taiwan. In this study, it is designed to identify clinical predictors for patient satisfaction and tolerance to unsedated upper GI endoscopy in Taiwan population by using multivariate analysis on a relatively large patient group. Parameters assessed in this study include patient's characteri- stics, previous EGD experience, professional skill of the operator, the scheduled procedure's time of day, total procedural duration, and endoscopy staff assistance.

Materials And Methods

Patient population

A total of 3,087 patients who were scheduled to undergo diagnostic upper GI endoscopy in Cathay General Hospital of Taipei between September 2005 to December 2005 were surveyed. Patients were identified from the outpatient endoscopy schedule.

Our study excluded patients either who were under age of 18 or unwilling to provide consent for unse- dated upper GI endoscopy. In addition, patients were not allowed to participate if they had any known documented allergy to anesthetic spray used, namely lidocaine.

Endoscopic procedure

After administrating the topical pharyngeal spray, each patient underwent diagnostic upper GI endoscopy without sedative medication.

A biopsy procedure was performed for the identification of Helicobacter pylori infection

or potential malignancy in peptic ulcer patients.

All procedures were either performed by an endoscopist or by a fellow under the supervision of an attending staff in randomization. No patient had any information about the background of the operators. A standard 9.8-mm diameter endoscope (Olympus GIF-XQ260) was used in all of the procedures. Fellows were involved in about one- quarter of the total procedures in the morning and afternoon. Procedures in our endoscopy unit were usually performed during 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. A complete endoscopic examination was defined if each anatomic segment of the upper tract, including the esophagus, the stomach, the bulb and second portion of duodenum, was viewed adequately. All patients were given an anonymous questionnaire after the procedure and were asked to fill and return the questionnaire on discharge from the endoscopy unit.

Data collection

The questionnaire is based on validated Patient Satisfaction Survey (PSS), modified from Rubin and Ware's model

7. Components of the PSS are shown in Table 1. Patients rated each feature with a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from excellent, very good, good, fair, to poor. Higher satisfaction was defined as selected group of excellent, very good to good; Lower satisfaction was as selected group of fair to poor. Data collected from the surveys included demographic data, procedure start time (in the morning or afternoon), total procedure duration, previous experience with endoscopy, Table 1. Features to Evaluate in the Patient Satisfaction Survey

Episodes of examination

Discomfort during procedure

Professional skill of operator

Time of examination

Medical staff assistance

Total procedure time spent

Waiting on day

experience of the operator (fellow and attending) and assistance and encouragement of medical staff.

Statistical Analysis

A statistical software package (STATA

®, StataCorp) was used to design the database structure and to conduct the analysis of the collected survey data in this study. Descriptive analysis was reported as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and percentages with 95%

confidence interval (CI) for categorical variables.

Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney U-test were used to compare patients' characteristics between above- average satisfaction scores and those with below- average satisfaction. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify possible factors that could affect patient's willingness to receiving unsedated upper GI endoscopy. A p value of less than 5% (< 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

Results

There were 3,087 patients scheduled for upper endoscopies during the 4-months study period that were eligible to participate in this study. All of the patients were able to complete the upper GI endoscopy. The mean (±SD) age of the patients was 47.7 (±15) years. There were 1601 (51.9%) female patients and 1486 (48.1%) male patients. Of all the procedures, 733 (23.7%) were performed by supervised fellows, 1824 (59.0%) procedures were conducted by junior attending staff (less than 10 years of work experience), and the remaining 530 (17.3%) procedures were executed by senior attending staff (more than 10 years of work experience). The mean (±SD) procedure duration was 4.3 (±2.1) minutes. In 2184 (70.7%) of the procedures some assistance and/or verbal encouragement to the patients from the medical staff were given, so conversely 903 (29.3%) of the patients received no assistance from the medical staff. In terms of previous EGD experience, 1148

(37.1%) patients underwent the procedures for the first time, and 504 (16.3%) patients had more than 4 episodes of previous experience with upper endoscopy (Table 2). The recorded indications from all of the procedures included 907 (29.4%) cases of vomiting, 757 (24.6%) peptic ulcer diseases, 630 (20.4%) acid regurgitations, 376 (12.1%) dyspepsia, and 417 (13.5%) miscellaneous symptoms. Post procedural comments were also collected from the patients in order to understand the reasons for discomfort experienced during Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

EGD (N=3087)

Gender (M/F)

1486/1601

Age (yr)

Mean, (±SD), range 47.67(±14.99), 18-93

Previous EGDFor the first time 1148

Two times 902

Three times 533

More than four times 504

Indication for EGD

Vomiting 907

Dyspepsia 376

Reflux symptoms 630 Follow-up (e.g., ulcer, 757

Helicobacter pylori) Miscellaneous 417

Diagnosis

Normal 1215

Esophagitis 704

Gastritis 586

Gastroduodenal ulcer 490

Others 92

Procedure time (min)

Mean, (±SD), range 4.29(±2.09), 3-20

Endoscopy performed bySupervised fellow 733

Junior attending staff 1824

Senior attending staff 530

Time of examination8-10 AM / 10-12 AM 1298 /1368 12-2 PM / 2-4 PM 131 /290

Medical staff assistanceYes/ No 2184/ 903

Tolerate the examinationWell/ Poorly 2450/ 637

the procedures. The patients were given multiple choices, including panic sensation, high pharyngeal sensitivity, insufficient application of anesthetic spray, abdominal fullness, assistant presentation, and lack of technology expertise from the staff.

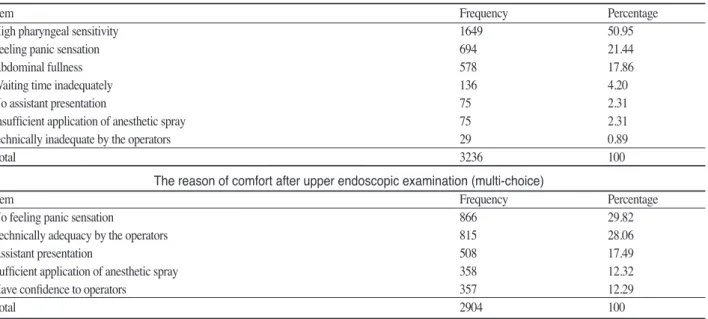

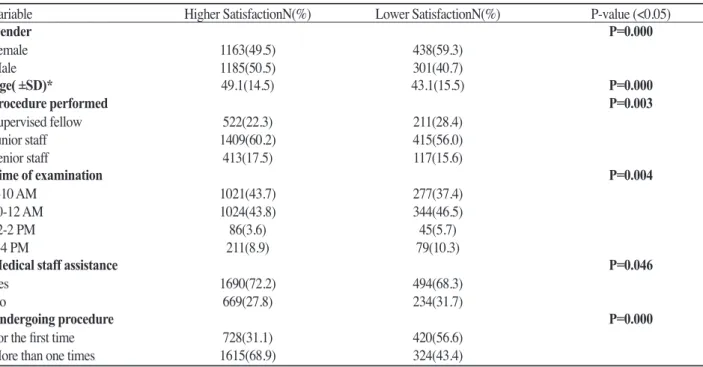

High pharyngeal sensitivity was noted in 1649 (50.9%) of the responses, and panic sensation was found in 694 (21.4%) responses (Table 3). The comparison of patients' characteristics between high and low satisfaction is presented in Table 4. The male gender had a higher satisfaction rate, and the female gender had a lower satisfaction rate; older patients had a higher satisfactory rate. Endoscopic examinations scheduled in the morning gave greater satisfaction. Procedures performed by attending staffs had higher satisfactory rate. Assistance and encouragement of medical staff helped in the elevation of the overall patient satisfaction level.

Table 5 shows the output when multivariate logistic regression models were applied to determine the confounders of patient satisfaction and willingness of receiving unsedated upper GI endoscopic examination. A satisfactory endoscopy procedure included the following predictors: male gender (odds ratio (OR) = 1.75), advancing age (OR=1.03),

procedure time in the morning (OR=1.58), presence of assistant (OR=1.67), and previous experience for upper endoscopy (OR=2.16).

Discussion

In assessing patient's satisfaction and tolerance to unsedated upper GI endoscopy procedures, there are some known influencing factors, including old age, male gender, decreased pharyngeal sensitivity, endoscopist's skill, and assistant's dexterity. In this study, male gender, old age, positive experience on previous endoscopic procedures, and shorter total procedure time were identified as indicators of an overall satisfied unsedated procedure.

Previous studies showed female patients were generally less satisfied with the procedure and had a lower pain tolerance level

1. Several possible explanations were examined and proposed to better understand the variance between male and female subjects. These included (but not limited to) higher panic sensation, functional and visceral sensitivity, cultural differences and physiological expectation

8,9.

Senior patients had strong predictive factors of comfort and willingness

1,10. Several studies sho- wed the importance of advanced age in predicting Table 3. The reason of discomfort after upper endoscopic examination (multi-choice)

Item Frequency Percentage

High pharyngeal sensitivity 1649 50.95

Feeling panic sensation 694 21.44

Abdominal fullness 578 17.86

Waiting time inadequately 136 4.20

No assistant presentation 75 2.31

Insufficient application of anesthetic spray 75 2.31

technically inadequate by the operators 29 0.89

Total 3236 100

The reason of comfort after upper endoscopic examination (multi-choice)

Item Frequency Percentage

No feeling panic sensation 866 29.82

Technically adequacy by the operators 815 28.06

Assistant presentation 508 17.49

Sufficient application of anesthetic spray 358 12.32

Have confidence to operators 357 12.29

Total 2904 100

satisfactory unsedated endoscopy. It has been hypothesized that the elderly showed a physiologic difference in pharyngeal sensory function and a decline in the integrity of the efferent pathway of the gag reflex

11,12. Senior patients had more cardio- pulmonary complications in sedated upper endos- copy. The need for close monitoring during and after the procedure, specialized nursing care and the effects of sedative medications required for more senior patients are seen as disadvantages of seda-

tion. Our study showed satisfaction and tolerance levels increased in older patients.

Data from this study indicates that endoscopic examinations scheduled in the morning have higher satisfaction as compared to afternoon sessions. It is also interesting to note that the comfort level of the patients were also higher during the morning procedures. This finding indicates patients could break their fasting earlier and decrease their hunger pains. Generally spea- Table 4. Comparison of patients' characteristics in high and low satisfaction (N=3087)

Variable Higher SatisfactionN(%) Lower SatisfactionN(%) P-value (<0.05)

Gender P=0.000

Female 1163(49.5) 438(59.3)

Male 1185(50.5) 301(40.7)

Age( ±SD)* 49.1(14.5) 43.1(15.5) P=0.000

Procedure performed P=0.003

Supervised fellow 522(22.3) 211(28.4)

Junior staff 1409(60.2) 415(56.0)

Senior staff 413(17.5) 117(15.6)

Time of examination P=0.004

8-10 AM 1021(43.7) 277(37.4)

10-12 AM 1024(43.8) 344(46.5)

12-2 PM 86(3.6) 45(5.7)

2-4 PM 211(8.9) 79(10.3)

Medical staff assistance P=0.046

Yes 1690(72.2) 494(68.3)

No 669(27.8) 234(31.7)

Undergoing procedure P=0.000

For the first time 728(31.1) 420(56.6)

More than one times 1615(68.9) 324(43.4)

*t-test

Table 5. The characteristics affecting patients' willingness of receiving unsedated upper GI endoscopic examination

OR S.E 95% CI P-Value(P <0.05)

Gender (M:F) 1.754 0.116 1.396-2.204 0.000

Age (Old: Young) 1.033 0.004 1.025-1.042 0.000

Episodes of examination 2.168 0.116 1.726-2.724 0.000

Degree of discomfort 2.890 0.321 1.544-5.438 0.001

Total procedure time 0.915 0.027 0.867-0.966 0.001

Fellow : Junior attending 0.752 0.186 0.522-1.083 0.125

Fellow : Senior attending 0.733 0.219 0.477-1.127 0.157

Time of examination (8-10AM: 2-4PM) 1.582 0.230 1.008-2.482 0.046

Time of examination (10-12AM: 2-4PM) 1.124 0.198 0.762-1.220 0.555

Time of examination (12-2PM: 2-4PM) 1.120 0.323 0.595-2.109 0.725

Medical staff assistance 1.675 0.231 1.064-2.636 0.026

OR= Odds Ratio; SE=standard error; CI=Confidence Interval

king, waiting times are an important determinant for patient satisfaction in varying examination

13. Meanwhile, a shorter waiting time before endos- copy may ameliorate patient anxiety.

Our patients with previous endoscopy experience showed patient perception to endosco- pist's technical skill had the most important predictor for satisfaction

14. The comfort and tolerance to endoscopic procedures increased when performed by an experienced endoscopist. In our study, patients had a higher satisfaction when the procedures were performed by junior and senior attending staff. The willingness of fellow-related unsedated upper GI endoscopic procedures is low.

The comparative odd ratio is 0.752 and 0.733 respectively.

In our study, high pharyngeal sensitivity was the most frequent cause for discomfort after endoscopy examination. The presence of increased pharyngeal sensitivity had an important impact in patient satisfaction

15,16. Pharyngeal anesthetic spray was administrated to all the patients by the standard procedure, which avoided confounding variation. In this study the assessment of the gag response of the patients was not quantified. The second frequent reason for discomfort was the panic sensation felt by the patient. In previous studies, investigators showed pre-endoscopic anxiety score had a significant impact on satisfaction and acceptance for the procedure

1. Patient anxiety, likely related to personality and culture, is of crucial impact on patient satisfaction. An endoscopy is associated with an increase in anxiety, but endoscopists' ability to estimate and anticipate anxiety is poor

17. Campo et al

18found that poor tolerance of an endoscopy is related to apprehension and a high level of anxiety.

Adequate explanation, background music, modification of room lighting and interior decor- ation, and even colored uniforms for nurses have all been suggested to release patient anxiety. Our study is not structured to measure the anxiety and panic

level of our patients. Several studies related to the usage of small-caliber endoscope for unsedated upper gastrointestinal examination have shown variable results of patient tolerance and acceptance.

One study showed the procedure might be well- tolerated and granted high sensitivity and specificity for detecting upper GI disease

18. However, other studies prove patient acceptance of ultrathin endoscopic examination without sedation did not improve tolerance between standard and small- caliber instruments

19. Again, our study was not designed to compare the impacts of different endoscope diameters.

Unsedated upper GI endoscopy offers several advantages. Patients can participate fully during and after the procedure, can immediately resume their routine activities, and do not require an escort. The cost of unsedated procedure is lower than sedated procedure. One study showed a 36%

cost reduction comparing two groups

20. The risk of sedated-related cardiopulmonary compromise can be avoided in conventional procedure. In conclu- sion, unsedated upper GI endoscopy is a feasible, acceptable, and cost-effective alternative to sedated procedure. Male gender, advanced age, shorter total procedure time, previous experience of upper GI endoscopy, experienced operators, scheduled examination in the morning, medical stuff assist- ance are associated with satisfactory outcomes from the patients. It is our suggestion that patients with the above characteristics had merit in selecting unsedated upper GI endoscopy. Our findings support the need for the Taiwan medical society to further examine the benefits of upper GI endoscopy without sedation as a comfortable and more beneficial procedure for both the patient and the medical profession.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wang Pa-Chun for his help in

statistical analysis; and the participating members

of the Division of Gastroenterology at Cathay General Hospital

References

1. Froehlich F, Schwizer W, Thorens J, Kohler M, Gonvers J-J, Fried M. Conscious sedation for gastroscopy: patient tolerance and cardiorespiratory parameters. Gastroenterology 1995; 108: 697-704.

2. Keefe EB, Schrock TR. Complications of gastrointestinal endoscopy. In: Sleisenger MH, editor. 5th ed. Philadelphia:

Saunders, 1993: 301-8.

3. Fleischer D. Monitoring for sedation: perspective of the gastrointestinal endoscopist. Gastrointest Endosc 1990; 36:

S19-22.

4. Waye JD. Worldwide use of sedation and analgesia for upper intestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 50: 888-91.

5. Hedenbro JL, Lindbolm A. Patient attitudes to sedation for diagnostic upper endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol 1991; 26:

1115-20.

6. Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, et al. Identification of factors that influence tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 111: 201-4.

7. Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, et al. Patients' rating of outpatient visits in different practice setting. JAMA 1993:

270: 835-40.

8. Tan CC, Freeman JG. Throat spray for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is quite acceptable to patients. Endoscopy 1996;

28: 277-82.

9. Zaman A, Hapke R, Sahagun G, Katon R. Unsedated peroral endoscopy with a video ultrathin endoscope: patient acceptance, tolerance, and diagnostic accuracy. Am J Gastroenterol 1998; 93: 1260-3.

10.Mulcahy HE, Kelly P, Banks M, Farthing MJG, Fairclough PD, Kumar P. Factors associated with tolerance to unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 47: AB128.

11.Shaker R. A wake-up call? Unsedated versus conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy ( editorial ). Gastroenterology 2000; 117: 1492-5.

12.Davies AE, Kidd D, Stone SP, et al. Pharyngeal sensation and gag reflex in health subjects. Lancet 1995; 345: 487-8.

13.Antonio Sa'nchez del R1'o, Juan Salvador Baudet, Onofre Alarco'n Ferna'ndez, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 19: 896-900.

14.Ross WA. Premedication for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy Gastrointest Endosc 1989; 35: 120-5.

15.Campo R, Brullet E, Montserrat A, Calvet X, Rivero E, Brotons C. Topical pharyngeal anesthesia improves tolerance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a randomized doubleblind study. Endoscopy 1995; 27: 659-64.

16.Hedenbro JL, Ekelund M, Jansson O, Lindblom A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

to evaluate topical anaesthesia of the pharynx in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy 1992; 24: 585-7.

17.Jones MP, Ebert CC, Sloan T, et al. Patient anxiety and elective gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 38: 35-40.

18.Sorbi D, Gostout C, Henry J, Lindor K. Unsedated small caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus conventional EGD: a comparative study. Gastroenterology 1999; 117: 1301-7.

19.Dumortier J, Ponchon T, Scoazec J-Y, et al. Prospective evaluation of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy:

feasibility and study on performance and tolerance.

Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 49: 285-91.

20.Reul TG, John PC, Mindie H, et al. Unsedated Ultrathin EGD Is Well Accepted When Compared With Conventional Sedated EGD: A Multicenter Randomized Trial.

Gastroenterology 2003; 125: 1606-12.

非麻醉上消化道內視鏡受檢病人之滿意度影響原因

邱榮彬2

李嘉龍

1,3,4吳啟華

1賴永智

1楊瑞能

2涂天健

1,31

台北國泰醫院 腸胃內科

2

汐止國泰醫院 腸胃內科

3

台北醫學大學 醫學院

4