1)

A Cohort Analysis of the Transition to First

Marriage among Taiwanese

Yu-Hua Chen* This study analyzes the trends in timing of entry into first marriage among Taiwanese. Applying the life table method, the variations in marriage timing associated with educational attainment and ethnic background are also examined across birth cohorts. The data used in this study come from the Taiwan Social Change Survey project. A comparison between birth cohorts shows that early and universal marriage has shifted toward late and less marriage, a trend being particularly salient among younger Taiwanese. Consistent with expectations, educational attainment is negatively associated with mean age at first marriage. However, the rapid increase in age at marriage and the decreasing proportion of ever-marrying of higher educated women and lowest educated men actually pinpoints a marriage market mismatched in Taiwan. Regardless of gender, Chinese mainlanders were most likely to postpone their marriages than other ethnic groups. Although many female aboriginals were already married in their early twenties, the majority of their male counterparts were staying single in the same age group.

Keywords: cohort anal ysis, mean age at first marriage, gender differences, educational attainment, ethnicity

I. Introduction

The traditional Chinese marriage system was characterized by the overwhelming power of parents. The marital decision was undoubtedly the first step to demonstrate parental control of this important family issue. In order to have complete dominance over the younger generation, romance and courtship among youth were strictly forbidden. Compatibility between

* Assistant Professor, Department of Bio-Industry Communication and Development, National Taiwan University.

two marrying families in terms of socioeconomic status, cultural background and implied value system was the top priority for the marriage match (Yi and Hsung, 1994). Hence, marriage was a process of agreements and rituals rather than an event, and a family based decision rather than a personal choice. Due to these concerns, most parents arranged and directed marriages for their children, so the idea that prospective mates should come from similar economic and social backgrounds has been maintained for decades.

With the drastic transformation from an agrarian society to an industrial society after World War II, several important but traditional family functions have been replaced by modern institutions in Taiwan. The rapid

increase in educational attainment, more pre-marital non-familial

employment and off-family living experiences of young people have caused a change in the relationships and interactions with parents and peers. Therefore, the young generation has become more likely to be involved in the process of mate selection and to participate in the marital decision later. According to a series of KAP (Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice of

Contraception in Taiwan) survey data, the percentage of parent-arranged

marriages declined from over 60 percent in the 1950s to slightly over 10 percent in the early 1980s (Thornton and Lin, 1994). The 2006 Taiwan Social Change Survey shows that more than 50 percent of all marriages are now decided entirely by the couples themselves (Fu and Chang, 2007). While young people now get involved in the mate selection process using their own social networks, Taiwanese parents continue to have an important role in the marriage process. A great majority of young people still date and marry those with parental approval.

The prevalence and timing of marriage in Taiwan have also greatly changed during the past century. In 1905, 47 percent of Taiwanese women aged 15-19 had married and most men married by their middle twenties. At age 30 and above, almost all women had been married (Thornton and Lin, 1994). Marriage was nearly universal among men and women in the

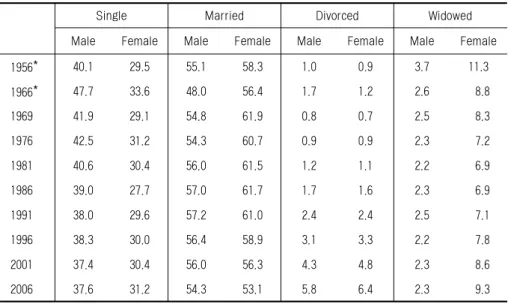

Table 1. Marital Status of 15 Years Old and Above, by Sex: Taiwan, 1956-2006

Single Married Divorced Widowed

Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female

1956* 40.1 29.5 55.1 58.3 1.0 0.9 3.7 11.3 1966* 47.7 33.6 48.0 56.4 1.7 1.2 2.6 8.8 1969 41.9 29.1 54.8 61.9 0.8 0.7 2.5 8.3 1976 42.5 31.2 54.3 60.7 0.9 0.9 2.3 7.2 1981 40.6 30.4 56.0 61.5 1.2 1.1 2.2 6.9 1986 39.0 27.7 57.0 61.7 1.7 1.6 2.3 6.9 1991 38.0 29.6 57.2 61.0 2.4 2.4 2.5 7.1 1996 38.3 30.0 56.4 58.9 3.1 3.3 2.2 7.8 2001 37.4 30.4 56.0 56.3 4.3 4.8 2.3 8.6 2006 37.6 31.2 54.3 53.1 5.8 6.4 2.3 9.3

Note: *Data of 1956 and 1966 refer to Taiwanese people who were 12 years old and above. Source:aStatistics of Household Registration, Department of Civil Affairs, Ministry of the Interior,

Executive Yuan, Taiwan, ROC.

first half of the twentieth century, but this trend was disturbed following an influx of mainlanders in the late 1940s. While there were many married couples in this group of newcomers, there were also a substantial number of unmarried young men in the military. The imbalanced sex ratio in this period produced a marriage squeeze, making it difficult for men, in particular for veterans, to find a potential partner. Table 1 shows that 42.5 percent of men were single in 1976, while for single women the percentage was only 31.2. Marriage was prevalent among women who were thirty years old and above in the same period. However, this substantial gap between genders has narrowed down in recent years because of the natural replacement of the population itself and the adoption of foreign brides (Chen, 2008).

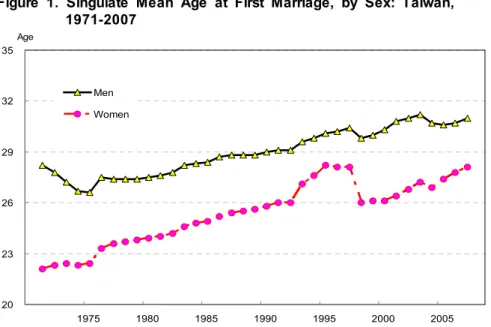

Economic and social changes have led to later marriage in Taiwanese society. Figure 1 shows that the singulate mean age at first marriage

Figure 1. Singulate Mean Age at First Marriage, by Sex: Taiwan, 1971-2007 20 23 26 29 32 35 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Men Women Age

Source: Monthly Report of Household Registration Affairs (Table 9. Median and Mean Age at Marriage Statistics), Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan (http://www.moi.gov.tw/stat/).

remained fairly stable in the mid 1970s, and then suddenly began to increase. Between 1975 and 2005, the mean age at first marriage increased from 26.6 to 30.6 years for men and from 22.4 to 27.4 years for women. For females, the increase in age at marriage was steeper than their male counterparts in the 1990s. By the end of 2007, the singulate mean age at first marriage reached 31.0 years for men and 28.1 years for women. This transition marked Taiwan as being one of the least marrying societies in the world.

The official statistics also show that a growing number of men and women in their thirties have never married. A closer scrutiny from the earliest and latest census data shows that the proportion of women in their early thirties who have never-married increased from 0.8 percent in 1905 to 11.6 percent in 2000. This growth in the single population has caught much attention. While this may only be a continuation of the shift toward late marriage, it may also represent the beginning of a trend toward lifelong singleness. Since in most societies men generally marry women

younger than themselves, the trends of postponement of marriage among women observed in recent birth cohorts may result in a growing share of single population.

Even though marriage is no longer seen as a prerequisite for a couple to live together and have children, marriage in Taiwan has maintained a crucial role in the process of family formation. To address these long-term changes related to first marriage among Taiwanese, this article is structured into five sections. Following the introduction, the second section starts with a brief review and discussion of the relationship between family formation and gender systems in the Chinese context. The third section describes the source of the data sets and explains the analytical strategies employed. The fourth section presents the empirical findings obtained by means of descriptive techniques, the life table method, and the Cox regression model. The final section presents the conclusions and discussion of the findings.

Ⅱ. Theoretical Considerations on the Changes in

Marriage

For several decades social science studies have documented the salient transformation of family patterns in the industrialized world, recently including Chinese societies. Marriage rates have decreased considerably and consensual unions seem to have gradually secured their status within interpersonal and familial relations. Since family formation often comes later in life, scholars argue that marriage has started to lose its hegemony as a dominant context for childbearing and childrearing. In other words, the very low fertility outcomes were believed to be associated closely with these changes in marriage per se. To raise the fertility rate that is already far below the replacement level, several pro-natal interventions and policies have been or are being adopted in industrial countries. Nevertheless, for policy makers and scholars, the effectiveness of these measures remains to

measures, encouraging marriage and family formation is considered as a priority in the Chinese context.

Having reached high levels in the 1960s, the period indicators for first marriage began a clear process of decrease in most Western societies. A variety of theories have been proposed to account for the postponement of first marriage and the dissolution of conjugal union. In the literature, two theories have drawn the most attention: the new home economics (Becker, 1981) and the second demographic transition (van de Kaa, 1987; Lesthaeghe, 1995). According to Becker, the key variables are the increase in educational attainment and in jobs available in the labor market for women. The increased autonomy and economic independence of higher educated women have reduced the material convenience of getting married. The economic wealth that they can attain by investing in themselves and their career is far greater than in their roles as wife and mother.

While Becker contests the view that the rapid increase in marital and family dissolution is related to the consequences of the economic independence of women, the theory of the second demographic transition tends to favor the role of ideational changes. The views presented by van de Kaa and Lesthaeghe argue that the increase in individual autonomy in both the public and private spheres is at the basis of the changes in the process of family formation. The transformation in marriage and family values has lead individuals to choose a favorable lifestyle without being concerned about inter- or intra-generational social contracts. As a result, the decrease in marriages and the increase in consensual unions can be seen as an expression of non-traditionalist attitudes. The changing attitude towards marriage has actually occurred in parallel with substantial changes in gender roles, both in and out of the household. The enhancement of educational opportunity for women and labor force participation has effectively narrowed the gender gap in economic returns and social status in the past few decades.

their first partnership without the conjugal bond, marriage is still the event that sanctions the beginning of life together for a couple in Taiwan. Many studies have evidence that only applying the specialization framework fails to explain the association between women's economic resources and the transition to marriage. Since women take overwhelming responsibility for household tasks and childcare, it is difficult for them to combine work and family responsibilities. The incompatibility of work and family is widely noted in the region of East Asian, and it is believed to be associated with the stability of family and women's economic resources (Retherford et al., 2001; McDonald, 2002). Moreover, many studies indicate that the majority of single women expect and intend to marry at some point in their lives. The latest Taiwan Social Change Survey confirms that the majority of respondents will eventually marry, although the proportion of never married has been increasing (Fu and Chang, 2007). This is similar to the trend found in Japan (Kaneko et al., 2008).

The difficulty of crossing social strata in marriage between people of different levels of educational attainment has been taken as an indicator of societal openness. Using data from 23 countries, Ultee and Luijkx's (1990) empirical study indicates that industrial societies differ in their levels of educational homogamy. In this regard, it is suspected that the traditional Chinese norm of family compatibility in the marriage match may lose its importance in modern Taiwanese society. Comparing the 1975 and 1990 data, an overall trend toward increased educational herterogamy in Taiwan can be ascertained (Raymo and Xie, 2000). With more educational opportunities available for women, scholars also find that marriage becomes less frequent as distance in schooling increases (Tsai, 1996; Tsay, 1996). However, it should be pointed out that although the strength of ethnic homogamy has decreased over time (Tsai, 1996), a positive association between the husband's and wife’s social classes can still be found (Tsay, 1996).

In this article, a cohort-based analysis is employed for describing the long-term trend in the timing of entry into first marriage. Since gender

differentials are still important in the Chinese family system, the comparison in mean age at first union formation between men and women across different cohorts is provided. In addition, the effects of educational attainment and ethnicity on marriage are discussed in detail.

Ⅲ. Data Source and Analytical Methods

1. Data

The data used to study the trends in first union formation were derived from the Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS) conducted by the Institute of Sociology of Academia Sinica. Since the first TSCS nation-wide survey completed in 1985, the project has followed 5 year cycles that rotate selective modules in order to capture the time-series of social changes. The family module has run through up to four cycles of survey operations, which enables researchers to further understand family and marriage changes from longitudinal perspectives. In this paper, all four cycles of the family module, conducted in 1991, 1996, 2001, and 2006, were used to explore the abovementioned research questions.

To ensure the representativeness of the TSCS project, a three stage and stratified random sampling design was employed in each survey. The sampling procedures are summarized as follows: First, all the townships in Taiwan were assigned to one of the 10 strata based on key socioeconomic indicators (The strata were decreased to 7 by combining the most urbanized areas in the 2006 survey). Several towns were then sampled from each stratum. Second, two villages were drawn from each selected town. The final stage was to randomly draw a number of households from each village and only one adult family member in each household was randomly chosen for completing the face-to-face interview (Chiu, 1991, 1996; Chang and Fu, 2002; Fu and Chang, 2007).

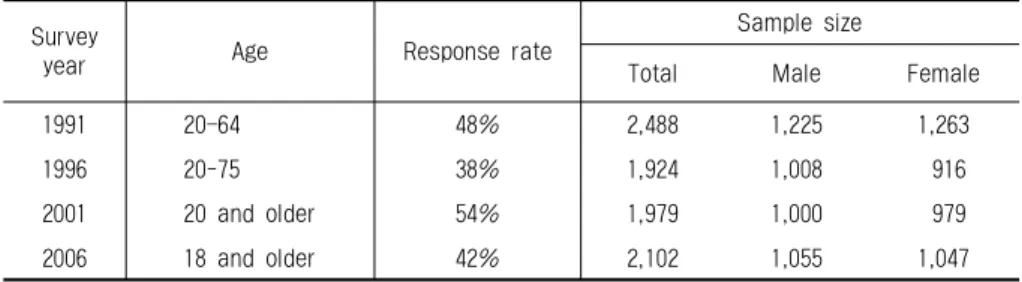

The sample characteristics of the four TSCS family modules are shown in Table 2. There are slight differences in age range in the four surveys,

Table 2. Sample Characteristics of the Four TSCS Family Modules, 1991-2006

Survey

year Age Response rate

Sample size

Total Male Female

1991 20-64 48% 2,488 1,225 1,263

1996 20-75 38% 1,924 1,008 916

2001 20 and older 54% 1,979 1,000 979

2006 18 and older 42% 2,102 1,055 1,047

with the lower end being extended to 18 years old and the upper limit being omitted in recent surveys. The highest response rate was completed in the 2001 survey, yielding a 54% response rate. While the other three surveys have slightly lower response rates, several statistical tests have been made to ensure the representativeness of each survey. In total, there were 8,493 respondents including 4,288 males and 4,205 females. For the purpose of marriage study, 306 respondents born after 1980 were excluded from the analysis.

2. Measures and analytical methods

The event of central interest in this study is entry into first marriage. In Chinese society, the first marriage marks one of the most important transitions from adolescence to adulthood within the life course framework.

While non-marital cohabitation has become increasing prevalent in the

West, it is to some extent a precondition of marriage or simply a transitory life course for younger cohorts in the East. Undoubtedly, marriage still owns its legitimate status and plays the main institutional role for entry into parenthood in Taiwan. In this regard, only the pathway toward first marriage is examined and compared in the analysis.

Since only two family modules had collected respondent job information at the time of first marriage, employment status is not included in this research framework. Individual characteristics are employed including age,

education and ethnic background only. All respondents were categorized

into nine birth cohorts, the oldest one born before 1940, 1941-1945,

1946-1950, 1951-1955, 1956-1960, 1961-1965, 1966-1970, 1971-1975 and

1976-1980. Education was coded into five categories: elementary school or less, junior high school, senior high school, 2 or 3 years college, and university or above. Four ethnic groups were included: Fukkien, Hakka, mainlander and aboriginals.

In the following section, the analysis of trends in first marriage is divided into two parts. In the first part, the cohort variations in timing of entry into first marriage are examined. Although the cohorts covered in the four TSCS surveys had reached very different stages in their marriage by the time of data collection, the life table method provides the cumulative

proportions of ever-married men and women and permits us to draw

conclusions before completing the process of first marriage within a given cohort. In the second part, the life table method and multivariate Cox regression model are employed to explore the influence of gender, educational attainment and ethnic background on union formation. The specification of the models and covariates are discussed in the sections that follow.

Ⅳ. Trends in First Marriage

1. Timing of entry into first marriage

The presentation of the findings starts from a descriptive analysis. The period life table for transition to first marriage yields estimates not only of age at first marriage but also the proportion ever-marrying by age 45. The TSCS data permit us to follow the trends starting from the cohorts born at the beginning of the twentieth century until those born in the 1970s. These are the generations that represent the nuptiality trends of the past few decades. The analysis uses five-year birth cohorts as the main units. Cohort membership can be related to particular social and cultural contexts that

people face while growing up and starting their adult lives. More importantly, the changes across cohorts actually reflect the impact of rapid socio-economic transformation and exposure to Western ideas and values among Taiwanese.

The panels of Figure 2 present the timing of entry into first marriage for Taiwanese men and women by means of survivorship functions. Both panels reveal a continuous and extensive shift toward a delayed entry into first marriage. With respect to males, there was virtually no change in the timing of entry into first marriage among the cohorts born before 1960. The union formation was mainly concentrated at the later end of the age spectrum. Figure 2a shows that the biggest increase in the cumulative percentage occurred beyond age 30 and about 95 percent of members in these cohorts had entered conjugal union by age 45. In the following

generations, from the 1961-1965 cohort to the 1976-1980 cohort, the

percentage of men who entered their first marriage before age 30 has decreased proportionally. Remarkably, there has only been about one third of the youngest male cohort born in the late 1970s who have experienced first marriage by the time of data collection.

It should be noted that there is a significant difference between the oldest cohort and others. While the data show that marriage was nearly universal for Taiwanese women born before 1940, the proportion of ever-married was about 93.7 percent for their male counterparts by age 45. The lower marriage rate of the oldest male cohort could be partially explained by the temporal marriage squeeze when the marriage market was disturbed after the influx of Mainland Chinese in the late 1940s. Among this wave of immigrants there were a substantial number of unmarried young men in the military. The imbalanced sex ratio of the oldest cohort made it difficult for men to find a wife.

Unlike their male counterparts, the postponement of first marriage for Taiwanese women was proportionally extended across female cohorts. It was conventional for the oldest female cohort, born before 1940, to get married very early. Figure 2b shows that 35 percent of them had already

Figure 2a. Timing of Entry into First Marriage of Men, by Birth Cohort

married by the age of 20 and ten years later about 97 percent of the oldest women had entered conjugal union. On the contrary, for those born

in the early 1970s, the proportion of ever-married women was only

two-thirds by the age of 30. The data even illustrate further delayed

marriage among the youngest women (the 1976-1980 cohort). However, we

should be cautious in interpreting these estimates due to there being fewer cases collected in comparison with the other cohorts.

2. The impact of educational attainment on mean age at first marriage

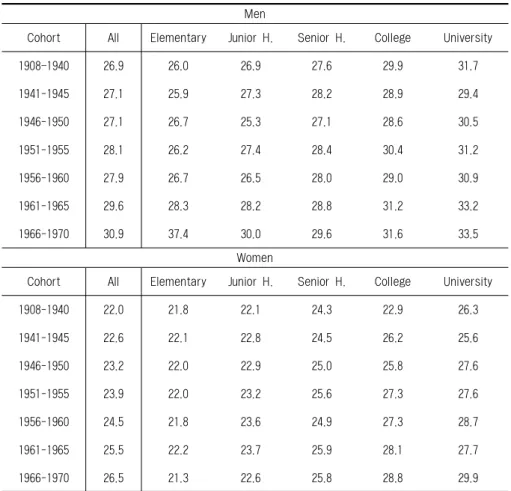

Differences in the timing of first marriage across birth cohorts can also be summarized by mean age at entry into first marriage. Because the overall proportion of ever-married for the sample born after 1970 was still less than fifty percent by the time of data collection, the comparison is limited to cohorts between 1908-1940 and 1966-1970 in this part of the analysis. In addition to doing a cohort comparison, Table 3 presents trends in mean age at first marriage for both genders by education computed by the life table method.

The evidence from Table 3 generally confirms the prevailing tendency toward late marriage observed in the past few decades. With respect to men, the mean age at marriage was already quite high at 27 years among men born before 1950, and it continually increased by 1 or 2 more years in the following birth cohorts. The mean age difference in entry into marriage was about 4 years between the oldest and the youngest male cohorts. While Taiwanese women were more likely to get married earlier than their male counterparts, the results show that the trend of delaying marriage had been adopted among older cohorts and became a more salient tendency in recent years. It is important to note that, in the same generation, the oldest women started their first union formation 5 years earlier than their male counterparts. Regarding the recent cohorts born in the 1960s, the mean age difference has been narrowed to 3.5 years.

Table 3. Trends in Mean Age at First Marriage, by Sex and Educational Attainment

Men

Cohort All Elementary Junior H. Senior H. College University

1908-1940 26.9 26.0 26.9 27.6 29.9 31.7 1941-1945 27.1 25.9 27.3 28.2 28.9 29.4 1946-1950 27.1 26.7 25.3 27.1 28.6 30.5 1951-1955 28.1 26.2 27.4 28.4 30.4 31.2 1956-1960 27.9 26.7 26.5 28.0 29.0 30.9 1961-1965 29.6 28.3 28.2 28.8 31.2 33.2 1966-1970 30.9 37.4 30.0 29.6 31.6 33.5 Women

Cohort All Elementary Junior H. Senior H. College University

1908-1940 22.0 21.8 22.1 24.3 22.9 26.3 1941-1945 22.6 22.1 22.8 24.5 26.2 25.6 1946-1950 23.2 22.0 22.9 25.0 25.8 27.6 1951-1955 23.9 22.0 23.2 25.6 27.3 27.6 1956-1960 24.5 21.8 23.6 24.9 27.3 28.7 1961-1965 25.5 22.2 23.7 25.9 28.1 27.7 1966-1970 26.5 21.3 22.6 25.8 28.8 29.9

Consistent with expectations, educational attainment is negatively associated with mean age at first marriage. Taiwanese men with lower and moderate education were still likely to marry in their late twenties. However, we should be cautious in the estimation of mean age at marriage for elementary-educated men being 37.42 years. Despite the relatively small number of respondents at this education level, which may have resulted in less reliable estimation, from the viewpoint of marriage formation, low educational attainment evidently translates into reduced attractiveness and

therefore constitutes a disadvantage for males in the Taiwanese marriage market. With respect to college and university educated men, the tendency of delaying marriage is quite significant, with mean age extended to 33 years for university graduates.

The impact of education is dissimilar between Taiwanese men and women. Starting from the bottom of the educational hierarchy, women who only completed compulsory education (elementary and junior high schools) feature as a prominent trend towards early union formation, compared to other higher educated women. In contrast, the increase in educational attainment has significantly postponed the timing of first marriage among younger female cohorts. The most remarkable long-term change is found in women with college education, with mean age entering into marriage at 22.9 years for the oldest cohort and 28.8 years for the youngest cohort. Since the number of women with a university education was small and most actually married in their late twenties, it is not surprising to observe a relatively moderate change in their mean ages at marriage.

3. Social/cultural variation in the timing of union formation

Since ethnicity is an aspect of social and cultural differences, it is important to examine variations in timing of first marriage across four major ethnic groups constituting Taiwanese society. Divided by ethnic background of respondents, Figures 3a and 3b presents the mean age at first marriage for men and women, respectively. Both panels indicate that Fukkien and Hakka, the largest and second largest group, share a similar marriage pattern across birth cohorts. Chinese mainlanders, except for the oldest cohorts who migrated to Taiwan before or after the Civil War, have generally completed higher education in that they were more likely to get married later than their Taiwanese counterparts. Nevertheless, the delaying trend among the younger male cohorts seems to indicate a disappearance of variation in the three groups.

Figure 3a. Mean Age at First Marriage of Men, by Ethnic Background 30.94 27.93 29.58 28.12 27.13 27.05 26.95 18 23 28 33 38 1908-1940 1941-1945 1946-1950 1951-1955 1956-1960 1961-1965 1966-1970 All Men Fukkien Hakka Mainlander Aboriginal Age

Figure 3b. Mean Age at First Marriage of Women, by Ethnic Background

26.54 25.54 24.51 23.95 23.24 22.62 21.98 18 23 28 33 38 1908-1940 1941-1945 1946-1950 1951-1955 1956-1960 1961-1965 1966-1970 All Women Fukkien Hakka Mainlander Aboriginal Age

in recent times, aboriginals have a relatively different marriage trend between men and women. Regardless of the birth cohorts of aboriginal women, early marriage marks it as an important event during their life course transition. With respect to men, on the contrary, there were many younger male aboriginals married in their early thirties. However, since the number of aboriginal cases is too small, it is not appropriate to compare and examine the major socio-economic characteristics across ethnic groups in order to more fully explore the possible reasons.

Ⅴ. Conclusions and Discussion

The preceding cohort analysis of the trends in timing of entry into first marriage reveals noticeable variations as well as diversity across generations and social groups in Taiwan. The traditional pattern of early and universal marriage has been replaced by late marriage and probably less marriage as well. For younger cohorts, the results show that men are getting married in their early thirties, and, in fact, the pace of delaying union formation across male cohorts is more predictable compared to women. While the mean age at first marriage of the youngest female cohort was still smaller

than that of men, the proportion of never-married among these younger

female cohorts deserves more attention in future research.

The impact of educational attainment and ethnicity on the timing of nuptiality has been demonstrated as well. The increase in levels of education is associated with delaying marriage, especially among highly educated Taiwanese women. In terms of ethnicity, the mean age at first marriage of Chinese mainlanders is higher than other ethnic groups because of their on average higher educational attainment. In addition, the disadvantageous status of the aboriginals refers to the diverse processes of family formation for both genders, with men getting married even later than Chinese mainlanders and women continuously marrying young. The dynamics of gender discrepancy in timing of first marriage have fairly

reflected the unfavorable socioeconomic status of aboriginals in recent years. As a theoretical argument mentioned in the literature review, the effect of Taiwanese women's economic independence on nuptiality has been in evidence, except for female aboriginal people (who are more likely to get married early for securing personal or family economic conditions). As women increasingly move into career-oriented jobs, a further postponement of marriage of young working women may be expected. These increases in educational attainment and labor force participation have been especially crucial factors in promoting individualism that is incompatible with the traditional family system.

The parent-child relationship is generally viewed as more important and enduring than the husband-wife relationship in the Chinese context. The patrilineal family system also puts stigma on children born outside of marriage. If such a traditional family system is practiced as well, it is clear that the trend of delaying marriage is much more prevalent among women (Mason, Tsuya and Choe, 1998). The report of the 2006 Taiwan Social Change Survey shows that a notable finding on changing attitudes is that

non-traditional attitudes are much more prevalent among women than

among men and there are very large differentials by marital status. For example, the belief that “it is necessary to be married to have a child” and “the traditional gender division of labor, with the husband being the breadwinner and the wife taking care of the family” remains strong among Taiwanese, but on average single women are least likely to agree with these traditional family attitudes than single men and married people (Fu and Chang, 2007). Putting these changes altogether, the attractiveness of marriage has declined for the younger female cohorts.

In Taiwanese society, the combination of the traditional family system and differences in gender role expectations between men and women, single and married people, and younger and older generations has made marriage a very difficult institution to enter, especially for marriageable single women. The tendency of delayed marriage among Taiwanese is confirmed

in this study and other research. The very limited pro-natal policy and government actions so far appear to have had no significant effect on raising marriage rates, which in turn may result in a growing proportion of

never-marrying.

References

Becker, G. 1981. The Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Chen, Yu-Hua. 2008. “The Significance of Cross-Border Marriage in a Low

Fertility Society: The Case of Taiwan.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 39(3): 331-352.

Chen, Yu-Hua and Yang-Chih Fu. 2002. Report for the 2001 Taiwan Social Change Survey. Taipei: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica.

Chiu, Hei-Y uan. 1991. Report for the 1991 Taiwan Social Change Survey. Taipei: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica.

______. 1996. Report for the 1996 Taiwan Social Change Survey. Taipei: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica.

Fu, Yang-Chih and Chin-Fen Chang. 2007. Report for the 2006 Taiwan Social Change Survey. Taipei: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica.

Kaneko, R., T. Sasai, S. Kamano, M. Iwasawa, F. Mita and R. Moriizumi. 2008. “Attitudes toward Marriage and the Family among Japanese Singles.” The Japanese Journal of Population 6(1): 51-75.

Lesthaeghe, R. 1995. “The Second Demographic Transition: An Interpretation.” Pp. 17-62 in Gender and Family Change in Industrialized Countries, edited by K. O. Mason and A. M. Jensen. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Mason, K. O., N. Tsuya, and M. K. Choe (eds.). 1998. The Changing Family in

Comparative Perspective: Asia and the United States. Honolulu: East-West Center.

McDonald, P. 2002. “Gender Equity in Theories of Fertility Transition.” Population and Development Review 26(3): 427-440.

Raymo, J. M. 1998. “Later Marriages or Fewer? Changes in the Marital Behavior of Japanese Women.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 60: 1023-1034. ______. 2003. “Educational Attainment and the Transition to First Marriage

Among Japanese Women.” Demography 40(1): 83-103.

Raymo, J. M. and M. Iwasawa. 2005. “Marriage Market Mismatches in Japan: An Alternative View of the Relationship between Women’s Education and Marriage.” American Sociological Review 70(5): 801-822.

Rindfuss, R. R., M. Choe, L. L. Bumpass, and N. Tsuya. 2004. “Social Networks and Family Change in Japan.” American Sociological Review 69(6): 838-861.

Retherford, D. R., N. Ogawa, and R. Matsukura. 2001. “Late Marriage and Less Marriage in Japan.” Population and Development Review 27(1): 65-102. Thornton, A. and Hui-Sheng Lin (eds.). 1994. Social Change and the Family in

Taiwan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

van de Kaa, D. J. 1987. “Europe's Second Demographic Transition.” Population Bulletin 42(1).

Yi, Chin-Chun and Ra-May Hsung. 1994. “Mate Selection Networks and the Educational Assortative Mating in Taiwan: An Analysis of Introducer.” Pp. 135-178 in The Social Image of Taiwan: Social Science Approaches (in Chinese), edited by Chin-Chun Yi. Yat-Sen Sun ISSP Book Series 33. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Yu-Hua Chen is Assistant Professor of Rural Sociology at the National Taiwan University. She is an editorial board member of the Taiwanese Journal of Population Studies. Her research and teaching specialties are family demography, sociology of development, rural sociology, and social research methods. Recently, she is working on the project of intergenerational transmission of reproductive behaviors and attitudes among Taiwanese. Email: yuhuac@ntu.edu.tw

(Received on April 9, 2009; Accepted on May 2, 2009)