行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

台灣中、外英語教師教學專業研究與協同教學模式之探討

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 95-2411-H-004-030- 執 行 期 間 : 95 年 08 月 01 日至 97 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學英國語文學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 吳信鳳 共 同 主 持 人 : 馬誼蓮 計畫參與人員: -99:何炳德 報 告 附 件 : 國外研究心得報告 赴大陸地區研究心得報告 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 國際合作計畫研究心得報告 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 98 年 02 月 10 日

Summary Report

台灣中、外英語教師教學專業研究與協同教學模式之探討

Professionalism of Native and Non-native English Language Teachers in

Taiwan and Its Implications on Collaborative Teaching

(Aug. 1, 2006 – July 31, 2008, NSC 95-2411-H-004-030)Research Team:

Primary Investigator: Cynthia H. F. Wu 吳信鳳

Professor, Department of English, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan (e-mail address: cwu@nccu.edu.tw)

Co-investigator: Ruth Martin 馬誼蓮

Instructor, Department of English, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan (e-mail address: rmartin@nccu.edu.tw)

Co-investigator: Peter Herbert 何炳德

Instructor, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan (e-mail address: peterh@ntu.edu.tw)

Submitted by

Department of English

National Chengchi University

(一)

計畫中文摘要 台灣中、外英語教師教學專業研究與協同教學模式之探討 關鍵字:英語非母語教師、英語教學專業、協同教學 英 語 教 師 若 英 語 為 母 語 (native) 則 通 常 會 被 認 為 比 英 語 非 母 語 (non-native) 教師佔優勢。在英語教學領域,母語與非母語教師之差別一直 存在,雖然是否真的與教學優劣相關尚無嚴謹的研究證實。近年來,由於 全世界的英語學習熱潮以及非母語教師的人數眾多,此一議題受到極多的 關注。許多研究(Braine, 1999; Cook, 2002; Liu, 1999; Medgyes, 1994; Samimy & Brutt-Griffler, 1999; Tang & Absalom, 1998)認為教師之母語與其 教學專業並沒有太大關係,英語為母語或非母語教師都可以成為好的英語 教師。但是英語為母語教師之優勢仍為各方所認定。 本研究即在探討這兩組英語教師是否真的因母語不同而有差別? 其差別是否反映於其教學中?是否與其教學專業相關?兩組老師同樣是英 語教師,在同一個英語教學領域,是否有同一套認定之教學專業標準? 若兩組教師確於教學方面因母語不同而有所差別,兩相互補的協同 教學是否為一理想模式?然根據調查(Carless &Walker, 2005),亞洲地區 許多協同教學都遭遇困難,成效不佳。究其原因,主要是因為兩組教師對 專業角色認定不清、對英語教學專業沒有一套共同之教學專業標準,使協 同教學無法真正落實。 本研究以台灣小學英語為母語及非母語英語教師為對象,採問卷調 查及訪談方式,調查其對英語教師之教學專業認知與專業標準認定,並探 究台灣宜蘭及新竹地區之小學協同教學模式,分析其優、缺點,並與研究 結果(調查及訪談)、及相關理論相互印證,期能建立適用英語為外語 (English as a foreign language)的台灣英語教學情境中的英語教師教學專 業標準,並提供協同教學之有效模式,對兩組英語教師之專業發展、協同 教學模式、及台灣之英語教育應有重要啟發及影響。(二)計畫英文摘要

Professionalism of Native and Non-native English Language Teachers in Taiwan and Its Implications on Collaborative Teaching

Key words: non-native English language Teachers, professionalism in ELT, collaborative teaching

A unique issue in the context of English language teaching (ELT) is the distinction between native versus non-native English-speaking teachers. There have been

numerous arguments against the native vs. non-native dichotomy in terms of ELT professionalism (Braine, 1999; Cook, 2002; Liu, 1999; Medgyes, 1994; Samimy & Brutt-Griffler, 1999; Tang & Absalom, 1998), and most of them are legitimate on any ground. Professionalism in ELT obviously cuts across the line of nativeness, i.e., both NETs (English teachers who are native speakers of English) and NNETs (English teachers who are non-native speakers of English) can both be effective English teachers. However, the myth of native speakers being better English teachers persists and the distinction between NETs and NNETs is perceived as important by many. This research aims to investigate how NETs and NNETs are perceived in terms of their professionalism. If there is a perceived distinction between them, is it reflected in their teaching practices and their perception of professionalism? Is there a common set of standards/criteria for professional expertise shared by both NETs and NNETs?

If there is a perceived difference between NETs and NNETs, collaborative teaching has generally been perceived as the best partnership of the two groups of teachers. However, collaborative teaching in East Asian classrooms has faced considerable problems (Carless &Walker, 2005). Although the problems are complex, a lack of a common set of professional values, ethics, and standard practices in the ELT profession seems to lie at the core of the issue. True collaboration between NETs and NNETs will not take place unless a professional common ground is shared.

A study was designed to address the above questions regarding the professionalism of elementary school NETs and NNETs in Taiwan and its implications on collaborative teaching. Two high-profiled NEST/NNEST team teaching English programs in Taiwan’s Yilan and Hsinchu City were studied through questionnaires and face-to-face interviews to investigate these ELT teachers’ perception of and standards for

professionalism. The main purpose of this research is twofold:

of ELT teachers in the EFL context of Taiwan

(2) To inform curricular initiatives in designing effective and sustainable collaborative teaching English programs/models at the elementary school level in Taiwan

台灣中、外英語教師教學專業研究與協同教學模式之探討

Professionalism of Native and Non-native English Language Teachers in

Taiwan and Its Implications on Collaborative Teaching

一、研究背景 Context/Relevance

A unique issue in the context of English language teaching (ELT) is the distinction of native versus non-native English-speaking teachers. Davies (1995) claimed that “[t]he native speaker is a fine myth; we need it as a model, a goal, almost an inspiration. But it is useless as a measure” (p. 157). There have been plenty of arguments against the native vs. non-native dichotomy in terms of ELT professionalism (Braine, 1999; Cook, 2002; Huang, S. D., Huang, P. H., Lu, & Chang, 2005; Huang, S. D., Huang, P. H., Lu, Chang, & Wu, 2005a, 2005b; Liu, 1999; Medgyes, 1994; Samimy & Brutt-Griffler, 1999; Tang & Absalom, 1998), and most of them are legitimate on any grounds. Professionalism in ELT obviously cuts across the line of nativeness, i.e., both NETs (English teachers who are native speakers of English) and NNETs (English teachers who are non-native speakers of English) can be effective English teachers.

However, the term native speaker or professionalism in the area of TESOL may not be taken for granted. No other professional areas seem to have an issue as complex and as “illusive” as native and non-native speakers. As obvious as it may seem, it is actually not clear at all what a native speaker really is. Researchers (Cook, 1999; Liu, 1999) have found it difficult to pinpoint the membership of native speakers of English. Language proficiency may not be a reliable predictor, as all of us have encountered speakers who can “pass as native speakers.” Ethnicity is obviously not a reliable predictor (e.g., an American born Chinese in the U.S. wouldn’t be categorized as a native speaker of English if being a Caucasian were a defining feature). Additionally, neither birth place nor education is a good predictor. A man born in Germany who immigrates to the U.S. at age 6 may not be disqualified as a native speaker of English, while a Chinese who received a Ph.D. in linguistics from a U.S. university and lived there for 30 years may still be a non-native speaker. There isn’t a well accepted set of defining features for a native speaker or for the construct of nativeness.

In addition to the construct of native speakers, professionalism in ELT is also a thorny issue. David Nunan (1999, 2001), as the president of TESOL Association 1999-2000, asked the question: “Is language teaching a profession?” He was struck by the use of the words “profession, professional, and professionalism,” in many other areas, while it seemed to be an unfamiliar construct in an ELT context. What is a profession? And what is meant by professionalism? Are there any widely accepted professional codes or standards of practice in the area of TESOL (teaching English to speakers of other languages)? What are some of the defining features of a professional (presumably good) ELT teacher?

Referring back to the issue of NETs and NNETs in regard to curriculum and pedagogy, collaborative teaching between NETs and NNETs has generally been perceived as the best complement of the two groups of teachers. NETs’ language proficiency and NNETs’ understanding of the students L1 and culture may complement each other and thus achieve the best teaching effect. However, the picture is far from this optimistic. Many

complications could arise when any two teachers are in the same classroom, not to mention a linguistically and culturally different NET and an NNET. Evidence of difficulties in team teaching is abundant in the literature (Carless, 2006; Carless & Walker, 2005), including the experience of programs in Japan, S. Korea and Hong Kong. The major difficulties are related to many factors; however, a lack of a common set of professional values, ethics, and standard practices in the ELT profession lies at the core of this issue.

Due to the global trend of learning English at a younger age, the elementary schools in various parts of Taiwan are under pressure to implement innovative English programs, especially after English was introduced into the formal elementary school curriculum in Taiwan in 2001. Some school districts/elementary schools have started to hire foreign teachers (NETs) to team teach with local NNETs. Among them, the programs in Hsinchu City 新竹市 and in Yilan County/City(宜蘭縣市)are two high profile models, which are quite different from each other. There have been a few studies evaluating these two models (林怡瑾,2002; 葉立婷、白亦方, 2005; 顏國樑、林至成、楊榮蘭,2003; 羅文杏, forthcoming NSC project technical report), but the findings are still preliminary and not substantive enough to inform future educational practice in this regard. As more and more areas in Taiwan are attempting to implement collaborative/team teaching between NETs and NNETs of some sort in their elementary school English classes, this is an area which warrants extensive and timely research.

二、研究目的及研究問題 Purposes and Research Questions

This research aims first to investigate how NETs and NNETs are perceived in terms of their professionalism: whether a perceived distinction (if any) between these two groups of teachers is reflected in their professional practice, such as linguistic competence, language use in class, classroom interactions, and various pedagogical/instructional practices, and whether such a perceived distinction is also related to their professional perception and beliefs, such as recognition of a set of accepted standards of practice and certification in TESOL, attitudes, commitment, or philosophy toward teaching (English), short- and long-term professional development, teacher-student relationships, and so forth.

Through this research, we hope to gain insight into the construct of professionalism, and to be able to establish a common set of professional standards for ELT teachers in the EFL (English as a foreign language) context of Taiwan. Based on the findings on

NNETs. We will first investigate models/programs of collaborative teaching in various parts of the world. The collaborative teaching English programs in Taiwan at the elementary school level will be examined carefully. The findings of this research could provide implications for educational initiatives in designing effective collaborative teaching English programs in Taiwan. In a nutshell, the major purpose of this research is twofold; it is

1. to establish a common set of professional standards/criteria for professional expertise of ELT teachers in the EFL context of Taiwan, and

2. to inform curricular initiatives in designing effective and sustainable collaborative teaching English programs/models at the elementary school level in Taiwan

Based on the above purpose, the questions guiding this research are as follows. 1. Are elementary school NETs perceived differently from NNETs in terms of their

professionalism in Taiwan?

2. What is professionalism for ELT teachers; in particular, what is the common set of professional standards or criteria for professional expertise for ELT teachers in Taiwan? 3. What are the educational implications/applications of the NETs and NNETs in relation to

their professionalism on curriculum, pedagogy, and teacher education?

(1) In terms of curriculum and pedagogy, what may be effective programs/models of collaborative teaching between NETs and NNETs in Taiwan’s elementary schools? (2) In terms of teacher education, what are the factors/conditions conducive to the

development of the professionalism of NETs and NNETs?

三、重要性 Importance

The issue of non-native English teachers’ efficacy has received much attention. Research into this specific area is especially warranted, considering that the overwhelming majority of English teachers throughout the world are non-native speakers and the steady increase in the importance of English as a global means of communication. While English has become the lingua franca for international business, technology, and academia in the ever changing process of globalization, the number of non-native speakers of English in the world has out-numbered native speakers 3 to 1 (Crystal, 1997; Power 2005). The non-native

speakers are actually transforming the global language; Queen’s English may not be the norm. The question “Who owns English?” is attracting global attention. The issue of NETs and NNETs is thus all the more pertinent for the local and global English education.

This study explores the issues of NETs and NNETs and ELT professionalism, and its educational implications on collaborative teaching in Taiwan, which are of interest to numerous groups: NETs and NNETs themselves, parents, students, ELT educators and researchers, school administrators and educational policy makers, and so forth. The

research findings will provide information for both NETs and NNETs to critically reflect on their professional roles, beliefs about ELT professionalism, and how their reflection and beliefs are reflected in their teaching practice. By doing so, it is hoped that the focus of effective teaching may be shifted from the uni-dimensional native versus non-native dichotomy to standards or criteria for professional expertise for ELT teaching.

Taiwan has introduced English into the formal elementary school curriculum from grade 5 in 2001 and from grade 3 in 2005. More and more elementary schools start to implement innovative collaborative teaching English programs to get ahead in this heated English race. Several high-profile collaborative teaching English programs in Taiwan’s public elementary schools (such as Yilan and Hsinchu) have been in operation in the past 4 years, difficulties and problems have arisen due to a lack of true collaboration between NETs and NNETs and a professional standards or criteria for ELT teachers, native or non-native. Findings of this research may provide timely implications and valuable information on good models of teacher cooperation and collaboration in ELT. Exemplary team teaching models can become an important avenue to professional development of both NETs and NNETs and to the mutual understanding of differing cultural and pedagogical viewpoints.

四、國內、外相關文獻探討及研究心得 Literature Review

1. Native vs. Non-native English Teachers: Who are better English teachers?Medgyes (1992) stated that one of the most contested issues in ELT is the

native/non-native speaker issue. The first issue concerns the membership of native speakers. Who, for example, is and is not a native speaker of English? Language proficiency,

generally designated to indicate the membership of nativeness, is itself an illusive construct. We often times encounter speakers who can “pass as native speakers.” Ethnicity is

obviously not a reliable predictor either. From a social-cultural perspective, Liu (1999) discussed a need for change in professional labels. He believed that identification of an individual to be a native speaker or a non-native speaker of English is a difficult if not impossible task. He suggested that both precedence in language learning and language competence determine which label is used. Social identity and cultural affiliation are also determinants in labeling, as is early language environment.

Arva and Medgyes (2000) reminded us that membership of any category is not so much a privilege of birth or education as “a matter of self-ascription” (p. 356). Kramsch (1997) also illustrated: “[a]nyone who claims to be a native speaker is one who is accepted by the group that created the distinction between native and non-native speakers” (p. 363). Either the acceptance or the distinction made by the group is mostly perceptions – the

self-perception of the “native speaker” based on the perception of the group that there is a distinction, instead of a set of defining features.

Regardless of the illusive nature of nativeness, Medgyes (1994) made a clear distinction between NETs and NNETs nevertheless, identifying them as “two different species” (p. 27). He believed that by definition it is not possible for a non-native speaker to achieve

native-speaker competency, regardless of their motivation, aptitude, experience, education, or other factors. Medgyes and his colleague (Arva & Medgyes, 2000) observed the teaching behaviors of NETs and NNETs in the classroom and concluded that the primary advantage attributed to NETs lies in their superior English-language competence. Apart from serving as a “perfect language model,” NETs also provide rich resources of cultural information and tend to motivate students to talk in English.

However, Medgyes (1992) also argued that NNETs’ weakness in English is exactly their strength and he listed at least five advantages of NNETs: (1) they can be models of successful English learners; (2) they have an advantage in teaching English based on their own

experience of learning English; (3) they can anticipate language differences; (4) they can be more empathetic to the needs and problems of their learners; and (5) they can share with students in their mother tongue. Medgyes (1992) concluded that a teacher’s effectiveness does not depend upon whether he or she is a native or non-native speaker of English.

In response to the claim of a NET being an “ideal language model,” Suarez (2000) pointed out that it has had “disastrous effects on the morale of teachers who feel inferior and inadequate when they compare themselves to their L1 colleagues” (p.1). Some L2 English teachers, according to Suarez, feel that they are also inadequate as teachers because they are not fully proficient in English. The issue, then, is more than just a linguistic one, but could also involve professional power struggles and emotions. In a similar vein, Inbar (2001) further indicated that the division between native versus non-native teachers regarding the superiority of the native speaking English teacher was seen to indicate a power struggle over professional status between the two groups. The results of his study demonstrated the ineffectiveness of teacher classification according to the single criterion of birth, and substantiated context-embedded models in foreign language teaching.

Cook (1999) further argued that the prominence of native speakers in language teaching has blurred the distinctive nature of successful L2 users and created an unattainable goal for L2 learners. He suggested using the positive term “multicompetence” to refer to L2 users instead of using non-native speakers, which focuses on their “language deficiency” and is therefore a negative term. L2 learners should NOT be viewed as “failed native speakers” (p.195). Along a similar vein, Rampton (1990) suggested substituting “expert” for “native” when discussing language proficiency. He claimed that “expertise is learned, not fixed or innate" (p.98) and that "to achieve expertise, one goes through processes of certification, in which one is judged by other people” (p.99).

and on their own terms by being multicompetent, Rampton urged refocusing on the issue of expertise instead of on nativeness. Inbar (2001) also appropriately argued that emphasis on the language proficiency of the native speaking teacher devalues the professional status of language teaching as it disregards subject matter knowledge components acquired through training and professional expertise.

Canagarajah (1999) warned that this narrow sense of NET-only professionalism has prevented NNETs from developing their expertise in ways relevant to their local community needs, apart from forcing them to be obsessed with native-like pronunciation or other narrow linguistic properties. A well-trained NNET could very well be better qualified than a native speaker. NNETs have their unique strengths and contributions to English teaching, such as showing empathy to the needs and problems of their students, providing a good model for emulation, teaching effective language learning strategies, assisting students through sharing their mother tongue, anticipating language learning difficulties, and so forth (Canagarajah, 1999; Cook 1999; Medgyes, 1992; Phillipson, 1992; Tajino & Tajino, 2000). The overall consensus is to shift the notion of experts in English teaching from “who you are” to “what you know” (Rampton, 1990).

Even though the distinction between NETs and NNETs may not and need not be

substantiated in regard to expertise in ELT, the “native speaker fallacy” (Phillipson, 1992) is still a reality and the difference between NETs and NNETs is still widely and generally perceived as real. Echoing Medgyes’ (1992) remark, Carless and Walker (2005) pointed out that NETs’ strengths are the relative weaknesses of the NNETs, while NNETs’ strengths reflect the weaknesses of the NETs. NETs possess a breadth of vocabulary, can use appropriate idiom, have intuitive knowledge about usage and provide an insider’s cultural knowledge of a language community. They engage students in authentic English use, may be less reliant on textbooks as teaching aids, bring different perspectives to materials and thus have some novelty value – at least initially. NNETs can be positive role models for students, are better placed to anticipate students’ language difficulties and make profitable use of the mother tongue with thus richer resources for explaining grammar points. In addition, NNETs are likely to have better familiarity with local syllabuses and examinations and may find it easier to develop close relationships with students. Widdowson (1994) also stressed the advantages of NNETs, who are most familiar with the attitudes, beliefs, and values in the students’ cultural world.

Therefore, instead of positioning NETs and NNETs in two polar opposites, these two groups of teachers may best work side by side in a complementary relationship. We now turn to the literature on collaborative teaching.

Collaborative teaching between NETs and NNETs has generally been perceived as the best partnership of the two groups of teachers. NETs’ language proficiency and NNETs’ understanding of the students L1 and culture may complement each other and thus achieve the best teaching effect. The picture is far from being this optimistic. Many complications could arise when any two teachers are in the same classroom, not to mention NETs and NNETs who are linguistically and culturally different. Evidence of difficulties in team teaching is abundant in the literature, such as the experience of Japan, S. Korea and Hong Kong.

(1) Collaborative/Team Teaching Programs in Hong Kong, S. Korea, and Japan Carless and Walker (2005) reported that team teaching in East Asian classrooms has faced considerable problems. Storey et al. (2001) found there was a lack of genuine

collaboration between NETs and NNETs in Hong Kong secondary schools, with little sharing and understanding of what their counterparts were doing. There was little evidence of successful team teaching, which was often limited, with NNETs acting as passive observers who occasionally helped with translation and discipline in NETs’ classes.

Storey (1998) and Storey et al. (2001) found that low ability students improved most when taught by a combination of NNET and NET rather than one of these alone. NETs reported difficulties in handling lower ability students, with an inability to speak the student’s L1 being a serious disadvantage. There was little shared philosophy between NETs and NNETs, which was exacerbated when NETs were seen as a threat by NNETs. This perceived threat intensified when NETs made critical comments about local teaching and learning practices.

Hong Kong’s NETs are trained and experienced, but they do not have much experience in team teaching. Other schemes, such as Japan’s Japan Exchange and Teaching program (JET), employs mostly untrained native English speaking college graduates to carry out team teaching (Gorsuch, 2002). Tajino and Tajino (2000) reported that this has rarely been successful due to the unclear roles of the NETs and NNETs, lack of training and experience of NETs, and other obstacles.

The South Korean scheme EPIK (English Program in Korea) is based on JET and also failed to engender co-operation between NETs and NNETs (Kwon, 2000) with “cultural differences” being labeled as the chief culprit (Choi, 2002). NETs have mostly been withdrawn from S. Korean schools with some redeployed as instructors in teacher training institutes.

(2) Collaborative/Team Teaching Programs in Taiwan

worth noting. The first is Hsinchu’s co-teaching English program and the second is Yilan’s Fulbright model.

Hsinchu’s Co-teaching English Program

Due to the presence of the Science Park in the city, Hsinchu is relatively more

aggressive in initiating new programs in education than other areas in Taiwan. In 2001, the Hsinchu City Government began implementing a new English program, in which NETs were employed to co-teach with local homeroom teachers or English teachers in Hsinchu’s 26 public elementary schools (林怡瑾,2002). The aims for the program (新竹市國民小學英 語教育實施方案, as cited in 林怡瑾,2002, p. 239) are:

1. to understand and appreciate diverse cultures in order to broaden the students’ value system and global perspective,

2. to foster students’ interest and confidence in learning English as well as appropriate attitude toward learning,

3. to foster students’ daily English conversation skills in order to engage in interpersonal communications; and

4. to acquire new knowledge and concepts through oral communications and basic reading ability.

The above aims are quite sound and positive. However, it was an unusual practice for the Hsinchu City government to commission private language schools to recruit, train, support, and manage the foreign teachers. In other words, the elementary schools in Hsinchu City not only had no control over the foreign teachers placed into their classrooms, but also had to accept the assignment from a privately run language coaching school. Such a practice put the success or failure of the city-wide English program into the hands of the commissioned language coaching school. In 林怡瑾’s master thesis, she found through interviews with the foreign teachers that the quality of management of the language coaching school was below average. The foreign language teachers complained that their working contracts were often times not honored by the language coaching school, causing a high turnover rate of the foreign teachers. The supply and stability of the foreign teachers have thus become a liability of the program.

In addition to the poor management of the foreign teachers, the quality of the

pre-service teacher training and in-service teacher support has also been less than satisfactory. For the first year, there has been a two week pre-service orientation for foreign teachers, which the interviewees felt was far from enough for the 61% of foreign teachers who are not English majors and the 77.1% who have no experience teaching in elementary schools even in their own countries (林怡瑾, 2002, pp. 124-125). The in-service teacher support has been sporadic. There are other problems with the program besides foreign teachers; the teaching materials were considered less than satisfactory by teachers.

the first year. A task force was formed to do the evaluation and they spent about half a day in each of the 26 schools to produce an overall evaluation. Even the Hsinchu City

Education Bureau, the division directly supervising the program and in charge of the program evaluation, admitted that the program evaluation was “hasty and insufficient” (林怡瑾, 2002, p. 95).

The program evaluation of the Hsinchu co-teaching mode by 顏國樑、林至成、楊榮蘭 (2003)also indicated difficulties in true collaboration between NETs and NNETs, poor management by the private language school (leading to high turnover rate of the foreign teachers), mixed credentials of the foreign teachers, and so forth.

蔡立婷、白亦方(2005) analyzed the major problems of the Hsinchu program as follows:

1. Differential understanding of the division of labor as well as the professional roles of NETs and NNETs.

2. Poor quality of teaching due to foreign teachers’ lack of teaching experience; poor quality of co-teaching due to local teachers’ lack of communicative skills in English.

3. High turnover rate of the foreign teachers, resulting in curricular instability and discontinuity.

4. Lack of true collaboration due to a mismatch in personality characteristics and work ethics between NETs and NNETs.

However, 蔡立婷、白亦方(2005) also mentioned the advantages of the program such as foreign teachers serving as authentic language models and providing diverse cultural exposure. The students’ speaking, listening, and pronunciation were perceived to be improved under the instruction of foreign teachers.

Yilan’s Fulbright Program

Yilan has adopted quite a different approach from Hsinchu(蔡立婷、白亦方,2005; 學 術交流基金會, 2005). The program has been co-organized by the Fulbright Scholar Program in Taiwan and the Yilan County Elementary Education English Advisory Group (宜 蘭縣國教英語輔導團) since 2001. The Yilan County Elementary Education English Advisory Group is a formal administrative group under Yilan County. The majority of the group members are experienced English teachers.

The Fulbright Scholar Program in Taiwan works with the Fulbright Scholar Program in the U.S. in recruiting U.S. college graduates with outstanding credentials who have an interest in Taiwanese culture and in teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL). Each year 12 of them are selected and placed in 12 “seed elementary schools” in Yilan. These 12 young Fulbrighters go through a month long pre-service training on TEFL and cultural orientation. They need to work 35 hours per week in the assigned school, with 20 teaching hours and 15 hours campus residence. The Yilan County English Advisory Group is

responsible for orientating these Fulbrighters and for providing a bridge between them and the local elementary schools/teachers.

During their year-long service, workshops and support group gatherings take place every other week, helping these foreign teachers with difficulties/problems in teaching and their life here in general. These biweekly workshops/gatherings are coordinated and organized by the English Advisory Group and an advising TESOL specialist/researcher from the U.S., usually a faculty member in TESOL taking a year’s leave from his/her university. In addition, these young Fulbrighters are taking weekly Chinese lessons throughout the year.

Both the pre- and in-service training of the Yilan foreign teachers are obviously much better organized than those in Hsinchu. The mechanism built into the processes of foreign teacher recruitment has almost eliminated the problem of high turnover rate. Both the English Advisory Group in Yilan and the Fulbright Scholar Program in Taiwan have helped to establish the consistency and stability of this collaborative English teaching program. However, no formal evaluation has been conducted so far to investigate the Yilan program in terms of its teaching quality, curriculum design, learning outcome, and overall program effectiveness.

(3) Plight of collaborative teaching: What went wrong and what can be done? Based on the information of the Hsinchu and Yilan programs as well as the relevant experiences from other areas of Asia, collaborative teaching English programs between NETs and NNETs can produce positive effects such as (1) exposure of authentic English language and cultural diversity, (2) enhancement of real English language use in the classroom and students’ comfort level of using English, (3) promotion of teacher development through true collaboration between NETs and NNETs, and so forth.

However, the tremendous problems and difficulties arising in collaborative teaching have often times outweighed its advantages. As Carless and Walker (2005) analyzed earlier, collaborative teaching in East Asian classrooms has faced considerable problems. A major difficulty lies in the lack of understanding of the professional roles of NETs and NNETs. The two groups of teachers do not share the same set of standards or beliefs in

professionalism in ELT. Such a lack of mutual understanding is reflected in their

attitude/philosophy toward teaching, work ethics, and pedagogical practices. The unclear roles result in inappropriate division of labor, in wasted effort and teacher resources, and most devastatingly, in conflicts and resentment between NETs and NNETs which almost always guarantee failure of the program.

A related problem is the imbalanced or differential demands for the English language competence, teaching qualifications and accountability. NETs are hired mainly for their “nativeness,” often times compromising their credentials and competence to

teach in the local educational contexts. NETs are thus usually not held accountable for grades and administrative duties. Misunderstandings often arise due to NETs’ lack of experience and training, and local teachers’ lack of communicative skills in English. Conflicts in personality characteristics between NETs and NNETs due to cultural

misunderstanding also affect the effectiveness of collaborative teaching. Such a mismatch precludes true collaboration, leading also to high turnover rate of NETs and resulting in curricular instability and discontinuity. Other problems are mostly related to the poor quality of program administration and lack of coordination at both the program and the institutional levels.

Although the above difficulties and problems are complex, a lack of a common set of professional values, ethics, and standard practices in the ELT profession seems to lie at the core of the scheme. True collaboration between NETs and NNETs will not take place unless a professional common ground is established. It is only when NETs and NNETs share common ground that they can then reflect on collaborative teaching and attempt the

“peer-mentoring” (J. Liu, President-elect of TESOL 2005, personal communication, Nov. 13, 2005) of each other throughout the realm of TESOL.

(4) Taiwanese ELT Teachers’ Perception of Professionalism

To further pursue the issue, we might first want to ask: Is there a common set of

professional values, ethics, and standard practices in the ELT profession shared by NNETs in Taiwan? And how do they perceive themselves compared with NETs? Huang, et al. (2005a, 2005b) have investigated Taiwanese NNETs’ perceptions of their professional status in relation to NETs. Two hundred and thirty-eight elementary and secondary school English teachers were sampled from the northern part of Taiwan. Their data show that 70% of the respondents considered themselves competent ELT teachers when compared to NETs. The three most important factors related to their self-perception of professionalism are fair English proficiency, good teaching skills, and self-motivated professional growth.

However, the two studies by Huang et al. (2005a, 2005b) are based on

questionnaire-elicited self-reports, which reflect the responding teachers’ stated attitudes or practices rather than their actual behaviors. Stated behaviors may very well be influenced by various noises, such as the respondents’ perceptions, beliefs, and anticipated expectations of the people who are giving the questionnaire. Actual teaching practices in the classroom of both NETs and NNETs are needed to validate the perception studies. Also, diverse perspectives from NETs, parents, students, and school administrators are also required to cross check data in order to have a full picture of the issue. The issue, then, turns around again to professionalism in ELT.

David Nunan, as the president of TESOL Association 1999-2000, asked the question: “What is professionalism?” He was struck by the use of the words “profession, professional, and professionalism,” in many other areas, while it seemed to be an unfamiliar construct in an ELT context. What is a profession, and what is meant by professionalism then? According to the Cobuild Dictionary, "a profession is a type of job that requires advanced education and training." The Newbury House Dictionary defines professionalism as "the qualities of competence and integrity demonstrated by the best people in the field." In Nunan’s view, it is fundamental that a set of criteria be established for deciding whether an area of activity, such as English language teaching, qualifies as a profession. He suggested taking at least four criteria into account:

(a) the existence of advanced education and training,

(b) the establishment of standards of practice and certification, (c) an agreed theoretical and empirical base, and

(d) the work of individuals within the field to act as advocates for the profession.

The above four criteria apply to the ELT profession as a whole. Along the pedagogical level, the second criterion, an established set of standards of practice may be most relevant to classroom teachers. What is good language teaching? What are the defining features of a good language teacher? Harold B. Allen (1980, as cited in Brown, 2001, p. 429) once offered the following list of attributes of a good language teacher:

1. Competent preparation leading to a degree in TESL 2. A love of the English language

3. Critical thinking

4. The persistent urge to upgrade oneself 5. Self-subordination

6. Readiness to go the extra mile 7. Cultural adaptability

8. Professional citizenship

9. A feeling of excitement about one’s work

Such a list appears to be too general to be useful. All it says is that a good ELT teacher needs to love his or her work (2, 9), wants to do better (4, 5, 6, 8), and possibly get a degree in TESL (1), which could apply to almost any profession except for the cultural note, which could easily apply to a good world traveler or anybody who’s internationally orientated.

Brown (2001) offered a checklist of good language-teaching characteristics. This list contains the following four major categories (there are 5 to 12 sub-categories under each of the major categories, see Appendix I).

1. Technical knowledge 2. Pedagogical skills

3. Interpersonal skills 4. Personal qualities

The pursuit of a set of good language-teaching characteristics is sometimes

institutionalized into benchmark standards for teachers, such as the case in Hong Kong. Coniam and Falvey (2002) have established a benchmark for the Hong Kong government for ELT teachers in Hong Kong. The battery of tests evaluates teachers on their language ability along five components: reading, writing, listening, speaking, and language awareness. There are two oral tests, one of which is an observation of classroom language. The

rationale of a benchmark standard is not targeted at any specific group of ELT teachers. In principle, it should be implemented in a way by which both NETs and NNETs can be measured in a wider variety of ways with the same set of criteria. However, since greater emphasis was put on speaking in the case of Hong Kong, local NNETs believed that they were the true target of this assessment and this bred resistance.

A more complete benchmark is that of Wong Fillmore and Snow (2000) who stated that teachers need to have a basic knowledge of language structure: phonology, syntax,

morphology, discourse analysis, semantics. They should also know about language and cultural diversity, sociolinguistics, language development, second language teaching and learning, the language of academic discourse and text analysis. However, she is referring more to the content area teachers in American classrooms teaching immigrant children.

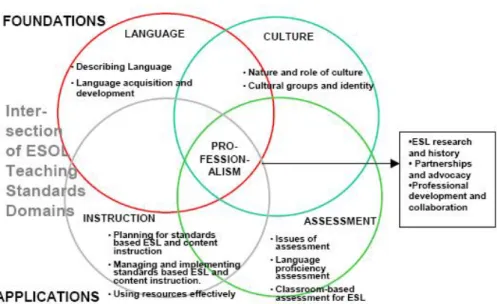

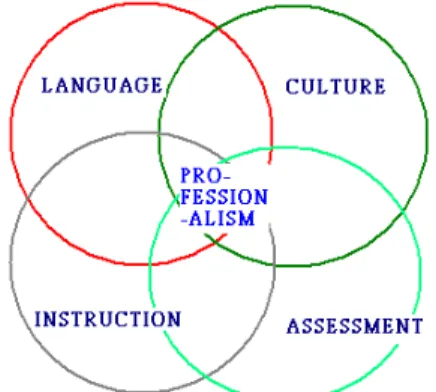

By far the most elaborate set of standards for ESL teachers as well as programs is the “TESOL/NCATE Program Standards” (TESOL, 2003), i.e., “Standards for the accreditation of initial programs in P-12 ESL teacher education.” These standards are used to evaluate whether an English teacher preparation program can receive national recognition. The standards are based on five domains, which are language, culture, instruction, assessment, and professionalism (see the figure below). Each domain is further divided into standards, resulting in a total of thirteen standards. Preparation programs are to provide evidence of teacher candidates’ dispositions, knowledge, and skills across the five domains and thirteen standards. To evaluate the evidence, a set of performance indicators under every standard is used. The indicators can be met a three proficiency levels, approaches standards, meets standard, or exceeds standard.

Figure 1. An interrelated framework of domains and standards for the accreditation of initial programs in P-12 ESL teacher education (TESOL, 2003, p.4)

In the domain of language underlie two standards, “describing language” and “language acquisition and development”. Teachers must show their understanding of language as a system by demonstrating their knowledge of phonology, morphology, syntax and other components of language. They must also possess the knowledge of first and second language acquisition. In the domain of culture underlie two standards, “nature and role of culture” and “cultural groups and identity.” Teachers must know the effect of culture in language development and academic achievement. In the domain of instruction underlie three standards, “planning for standards-based ESL and content instruction”, “managing and implementing standards-based ESL and content instruction” and “Using resources effectively in ESL and content instruction”. Teachers must understand standards-based practices when planning, implementing and managing ESL and content instruction. In the domain of assessment underlie three standards, “issues of assessment for ESL, “language proficiency assessment” and “classroom-based assessment for ESL”. Teachers must understand various issues of assessment and how to use the proper assessment instruments to gain insights into students’ language growth.

In the center domain of professionalism underlie three standards, “ESL research and history”, “partnerships and advocacy”, and “professional development and collaboration.” Teachers must possess the knowledge of the history of ESL teaching and the advances in the field so as to apply it in their instructions. They are the advocates for students and those in the profession; they also collaborate with colleagues when necessary.

These domains are not independent of one another; they are interrelated, with

professionalism positioned at the center of the framework. For example, an understanding of language acquisition in the language domain will definitely affect applications in

instruction, culture and assessment; knowledge of issues of assessment is bound to be related to the domains of language, instruction, and culture.

The criteria in the TESOL/NCATE Program Standards are not completely applicable to ELT teachers in Taiwan, since they are primarily established standards for L2 teachers in U.S. classrooms, using U.S. methods and materials, working within the local educational systems to help immigrant children learn English and integrate into the predominately

English-speaking society. However, their list does provide a clear framework and taxonomy of skills that can shed light on creating a profile of the kind of ELT teacher needed in Taiwan classrooms.

4. Teacher Knowledge and Expertise in Teaching

Tsui (2003) took a different approach in studying professionalism in ELT teachers. She explored further the concept of expertise in teaching based on her qualitative study with four EFL teachers in Hong Kong. She described the expert teacher as having a rich

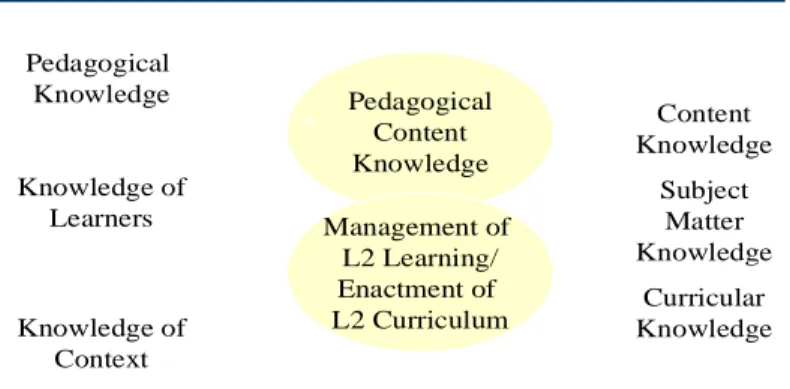

knowledge base including knowledge of students, as a group and as individuals, knowledge of subject matter, curriculum and materials, classroom organization, student learning, teaching strategies, school, family, educational and social environment. Modified from Shulman (1986)’s concept of teacher knowledge as content knowledge, Tsui (2003) listed seven aspects of knowledge of subject matter: (1) content knowledge; (2) the major facts and concepts of the discipline; (3) pedagogical content knowledge, i.e. how to represent this knowledge to students, using analogies, examples, illustrations, explanations and

demonstrations; (4) curricular knowledge of programs and materials; (5) general pedagogical knowledge of teaching and learning; (6) knowledge of educational aims and objectives; (7) knowledge of learner characteristics and knowledge of other content, outside the teacher’s specific subject domain. The interrelatedness of these aspects of knowledge is illustrated in the figure below.

Tsui (2003) defended that as lawyers and medical doctors, language teachers possess

Pedagogical Content Knowledge

Teacher Knowledge as Content Knowledge

(Shulman, 1986) Pedagogical Knowledge Knowledge of Learners Knowledge of Context Content Knowledge Subject Matter Knowledge Curricular Knowledge Tsui, 2003 Management of L2 Learning/ Enactment of L2 CurriculumFigure 2. Teacher knowledge as content knowledge (Modified from Shulman, 1986 by Tsui, 2003)

professional knowledge, but she specified that the teacher knowledge is knowledge in action: it is theory refined and tested dialectically by practice, thus becoming “situated knowledge.” As Tsui remarked, we have all encountered such teachers, whose lessons flow smoothly, integrating new knowledge into what was taught in previous lessons, who understand the needs of their students, know what they have studied before and can anticipate their questions and difficulties. They command student respect, motivate students to learn, maintain

student interest, get students involved in tasks and sustain student attention.

Along the line of teacher knowledge, Luo (2004, 2005) also investigated the knowledge base for elementary EFL teachers in Taiwan. Her data with four practicing and four

pre-service teachers indicate that the practicing teachers are more able to focus on developing “knowledge in action” by relying more on experiential knowledge and learning on the job, while pre-service EFL teachers try to apply theoretical knowledge to teaching practice. The approach of the pre-service EFL teachers, i.e., focusing on theoretical applications in actual teaching, happens to be the main emphasis of most of the EFL teacher education programs in Taiwan, which are perceived to be less than effective by both groups of teachers according to Luo’s other study (2005).

Studies of Tsui and Luo have rich implications for the elementary EFL teachers in Taiwan. Both used the distinctions of novice and expert teachers to explore teacher knowledge. Tsui examined the nature and actual manifestation of teacher knowledge in action, while Luo looked at the strategies these two groups of teachers adopted to understand the knowledge base of an EFL teacher in Taiwan.

5. Professionalism and NETs vs. NNETs

If NETs and NNETs are perceived to be essentially “two different species” (Medgyes, 1994, p. 27), could there be a common set of professional standards or criteria for expertise for both groups? According to Medgyes (1994) and Arva and Medgyes (2000), the following hypotheses can be made regarding the differences between NETs and NNETs. 1. NETs and NNETs differ in their language proficiency.

2. NETs and NNETs differ in their teaching behavior.

3. The difference in language proficiency results in difference in teaching behavior. 4. NETs and NNETs can be equally good teachers in their own terms.

Based on the four hypotheses, Arva and Medgyes (2000) then proceeded to illustrate the perceived differences in the use of English in class and in teaching behavior between NETs and NNETs, using contrastive descriptive comparisons, such as: NETs speak better English, use real language, and use English more confidently, while NNETs speak poorer English, use bookish English, and use English less confidently. In regard to teaching, descriptive

a variety of materials, tolerate errors, supply more cultural information, and so forth; while NNETs teach items in isolation, favor frontal work, use a single textbook, correct/punish for errors, supply less cultural information, etc. Some teaching traits which sound less

favorable to NETs are: NETs are less committed, have far-fetched expectations, are less insightful in attitude to teaching the language, and so forth; while NNETs are more committed, have realistic expectations, are more insightful in attitude to teaching the language, etc. Their illustration of the perceived differences were claimed to be validated by Medgyes’ empirical studies (1994) with 325 participants from 11 countries.

Such dichotomous contrasts between NETs and NNETs (Arva & Medgyes, 2000; Medgyes, 1994) in a professional context are hardly convincing, considering the

multi-dimensional nature of teaching and learning as well as teachers and learners. The descriptions of the comparison are obviously loaded with value judgment and emotional appeal. It almost sounds satirical when Medgyes (1994) announced, after he presented his findings in such a way, that differences do not imply advantages or disadvantages, and teachers should be hired solely by their professional virtue, not their language background.

The issues of the NETs and NNETs are much deeper and more complex than the picture presented by Arva and Medgyes. The simplistic framework laid out by Arva and Medgyes above may not do justice in explaining the extremely complex picture of NET and NNETs. There are multiple dimensions at work in an interconnected and dynamic way. Linguistically, the framework should first take into consideration teachers’ as well as students’ diverse language backgrounds (their L1, L2, or even L3) and how these languages are used and perceived at home and in the larger society. Pedagogically, how the classroom interactions and instructional goals are achieved through the use of these languages should be surveyed. Attention should be paid to how learning activities are structured and

implemented in relation to teacher’s language background and teaching behaviors.

Two vitally important dimensions are totally missing from Medgyes’ framework. The first is the cultural dimension. How does the teacher’s and students’ cultural background interact with the language use and teaching practice in the classroom? Do teachers and students share similar cultural beliefs and norms? And how does that affect the learning and teaching in the classroom? Learning outcome/assessment is another crucial dimension missing from the framework. When the efficacy/effectiveness or professionalism of NETs/NNETs was mentioned in the fourth hypothesis, we are not sure at all what it was meant by “good teachers in their own terms.” “Good teachers” can be an illusive term to begin with; “in their own terms” introduces even more ambiguities and confusion. When we examine the issues of NETs and NNETs in relation to ELT professionalism, all the above concerns and dimensions are over simplified or missing in Arva and Medgyes and should be carefully studied.

五、研究方法與進行步驟 Method and Procedures

A study was conducted to answer the research questions regarding the professionalism of NETs and NNETs in Taiwan and its implications on collaborative teaching. This study examines ELT teachers’ perception and standards of their professionalism. It involves 1. the perception of ELT teachers’ professionalism in Taiwan, investigating how NETs and

NNETs assume their respective roles and identities, and

2. whether they perceive themselves as professional ELT teachers and by what standards/criteria.

1. Sampling

Elementary school NETs and NNETs in Yilan and Hsinchu were the target

population of this study on two grounds: access to both groups of teachers in these two areas and demand for research. Within the current teacher education system of Taiwan, foreign teachers are basically excluded from the system, i.e., no foreign teachers could be certified within the system to be legally hired by the pubic secondary or elementary schools in Taiwan. This is the case from elementary through high school level, but not at the college level. However, due to the global trend of learning English at a younger age, the elementary schools in various parts of Taiwan are under pressure to implement innovative English programs, especially after English was introduced into the formal elementary school curriculum in Taiwan in 2001. More and more elementary schools have started to hire foreign teachers (NETs) to team teach with local NNETs. Evidence has also shown that though co-teaching between NETs and NNETs is a promising

pedagogical model, success has been rare due to various problems. This is an area which warrants extensive and timely research. Among the areas in Taiwan with NETs and NNETs co-teaching in the elementary school classrooms, Hsinchu and Yilan have generally been considered two high profile cases.

2. Instrument and Procedures

Data were collected through the following two ways: (1) Questionnaire Survey

A questionnaire was developed to investigate the perceived professionalism of

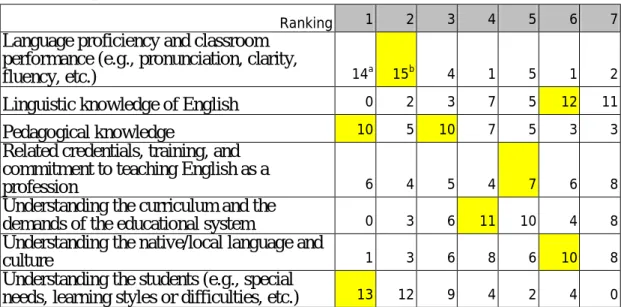

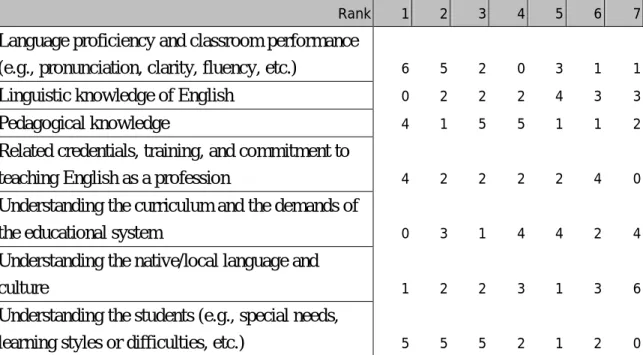

elementary school NETs and NNETs in Yilan and Hsinchu (see Appendix II). The overall content of the questionnaire drew on Brown’s (2001) good language-teaching characteristics (see Appendix I), “TESOL/NCATE Program Standards” (TESOL, 2003, see Figure 1 in the literature review section), Tsui’s conceptual framework on teacher knowledge and expertise (see Figure 2 in the literature review section), Arva and Medgyes’ interview sheet (2000, p.

371, see Appendix III), and other relevant literature.

The questionnaire contains the following four groups of questions:

1. Basic information of the participants, including their personal (such as gender or age) and professional background (for example, their highest degrees and specialization).

2. Perceived criteria/standards for professional English teachers in regard to the English language

3. Perceived criteria/standards for professional English teachers in regard to the classroom instruction

4. Perceived criteria/standards for professional English teachers in regard to the local culture and context

These four groups of questions represent four interrelated domains which constitute the perceived professionalism of both NETs and NNETs. Among the four, “Language” and “Instruction” are the major domains, and “Personal & Professional” as well as “Culture & Context” are the minor domains. Each domain took up 4 to 12 questions in the

questionnaire and altogether there were 40 questions.

Under the language domain, for example, the importance of a professional English teacher’s proficiency of the English language was checked, the interrelationship between the English language teachers’ and students’ L1 (Chinese) and L2 (English) were also asked, as well as how these languages were used and perceived at home and in the larger society in Taiwan. Under the instruction domain, various pedagogical concerns were investigated, including classroom interactions, how instructional goals were achieved through the use of language (including both L1 and L2). Under the culture and context domain, for example, the questions included the role of the local culture and educational system, such as the understanding of the micro-level culture (common practice and norms) of learning and

teaching in the classroom, the pedagogical, curricular and administrative culture of the school, as well as the macro-level culture (beliefs and values) of the larger society in Taiwan.

The questionnaire took an on-line form and it was in English for both NETs and NNETs to avoid possible translation discrepancies. The on-line questionnaire was first pilot tested by elementary school ELT teachers and university professors/researchers in the field of TESOL. The website was given to these teachers and the professors/researchers. The feedback was collected from the on-line version, oral interviews in person or by telephone, and through e-mail messages. Based on the rich feedback and extensive discussions among the research team members, the questionnaire had gone through multiple revisions before it was finalized. The website was then given to the Yilan and Hsinchu NETs and NNETs. After 6 weeks of time, the website was closed and the data were analyzed.

(2) Interviews

Interviews will be conducted with willing NETs and NNETs based on the response to the questionnaire. A note at the end of the questionnaire extended an invitation to

respondents who were interested in being interviewed afterwards. They were asked to give their contact information to indicate their interest. A 20 to 40 minute semi-structured interview was conducted in a face-to-face setting depending on feasibility and the

respondent’s preference. The purpose of the interview is to get information which could not be derived or was not clear from the questionnaire. Issues of NETs and NNETs and

professionalism will be further pursued. Arva and Medgyes’ interview sheet (2000, p. 371, also see Appendix III) was serve as an initial reference and was revised extensively.

Permission was asked to audio-record the interview and the audio-recorded interviews were transcribed within a week and analyzed afterwards.

4. Analysis

(1) Data grouping: By NET/NNET

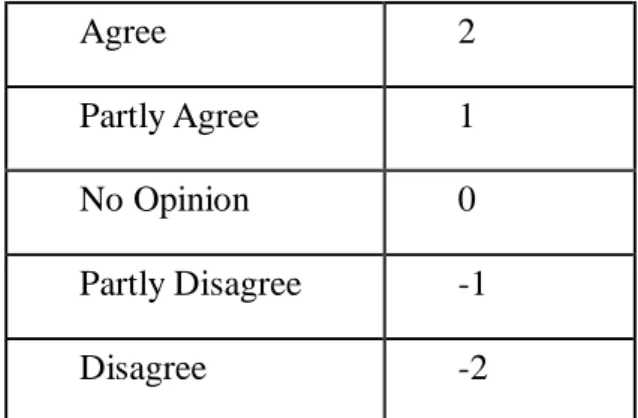

Due to the small sample size (n=53 in total, including 31 NETs and 22 NNETs), the questionnaire data were analyzed with descriptive statistics to understand the trends and patterns in perceived professionalism of NETs and NNETs. The data were analyzed as a group, and then by NET/NNET. Further analyses were conducted by education level and academic specialty (e.g., English major vs. non-major), by geographical area, by teaching credentials and experience, by gender, and so forth, to see how various factors interact with the native vs. non-native distinction. Based on the survey data, the interviews pursued the information not available from the questionnaire. Results of the questionnaire survey and the interviews were cross-verified and examined; points of convergence and divergence between the questionnaire responses and the interview exchanges were further analyzed. (2) Coding

respondents, including their age range, education (e.g. highest degree and specialty),

language background and language use (e.g., percentage of language instruction), co-teaching experience, and so forth (see Appendix II). Questions 13 to 40 were the second part of the questionnaire concerned the professionalism, i.e., qualities of good ELT teaching.

Respondents were asked to rate the qualities using a 5-level scale, and each level of the scale was then coded with a score as shown in the following table.

Table 1. Coding scheme of Question 13-40 in the Questionnaire

Agree 2

Partly Agree 1

No Opinion 0

Partly Disagree -1

Disagree -2

Part three of the questionnaire was a ranking task with the question: “What contributes most to the success of an ELT professional?” The respondents were given seven items (see Appendix II) and asked to rank the seven items from 1 to 7 in order of importance (with #1 as the most important). The ranks given were counted and percentages were calculated.

4. Reliability and Validity

The content of the questionnaire drew on relevant studies and conceptual frameworks in the literature (see above in ‘questionnaire survey” section for references) to ensure its

theoretical base. An ad hoc advisory committee of four local and international researchers/scholars in this area of expertise were formed to review the content of the questionnaire and to give comments for revisions. Before distribution, the questionnaire was pilot tested to further check the reliability and validity. Comments were invited from the ELT teachers in the pilot tests as important information for revising the questionnaire.

As for the interview, a semi-structured interview sheet was developed. The interviews were conducted based on the questionnaire responses, and extended to other issues of NETs and NNETs and professionalism. Recurring themes and concerns about ELT profession gleaned from the NNETs interview data were grouped into thematic patterns, validated through cross triangulation procedures, compared with relevant studies, and eventually built into an integrated framework for ELT professionalism.

5. Results and Discussions

Altogether 56 ELT teachers filled out the on-line survey during the 6 weeks of time. However, three of them did not indicate their status as NETs or as NNETs, so there were 53 in total valid questionnaires, with 31 of them as NETs and 22 as NNETs. There were 47 of them answered all the questions.

Section I. Background Information

Question #1-12 were concerned with the respondents’ background information. The following tables display the descriptive statistics of the whole group and by NETs and NNETs.

1. Gender:

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count female 75.0% 39 64.5% 20 90.5% 19 male 25.0% 13 35.5% 11 9.5% 2 answered question 52 31 21 skipped question 4 0 1 2. Age:

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count 24 or under 35.8% 19 58.1% 18 4.5% 1 25-34 15.1% 8 6.5% 2 27.3% 6 35-44 34.0% 18 19.4% 6 54.5% 12 45-55 13.2% 7 12.9% 4 13.6% 3 56 or above 1.9% 1 3.2% 1 0.0% 0 answered question 53 31 22 skipped question 3 0 0 5. Highest Degree:

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Bachelor's 62.3% 33 87.1% 27 27.3% 6 Master's 34.0% 18 12.9% 4 63.6% 14 Doctorate 3.8% 2 0.0% 0 9.1% 2 answered question 53 31 22 skipped question 3 0 0

6. If you do not have a degree in TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages), have you taken any TESOL-related courses?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Yes 56.5% 26 39.3% 11 83.3% 15 No 43.5% 20 60.7% 17 16.7% 3 answered question 46 28 18 skipped question 10 3 4

7. Do you have a teaching certificate?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Yes 65.3% 32 51.7% 15 85.0% 17 No 34.7% 17 48.3% 14 15.0% 3 answered question 49 29 20 skipped question 7 2 2

7a. For what age group(s) or level(s)?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count preschool/ kindergarten 5.7% 2 5.9% 1 5.6% 1 primary/ elementary 82.9% 29 76.5% 13 88.9% 16 secondary 31.4% 11 52.9% 9 11.1% 2 answered question 35 17 18 skipped question 21 14 4

8. What is your total number of years of teaching experience?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Years: 9.91 45 8.80 26 11.42 19

Months (if less

than a year) 3.18 11 1.28 7 6.5 4

answered question

50 30 20

skipped question 6 1 2

9. What is your total number of years teaching English?

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Years: 8.8 40 7.68 22 10.16 18

Months (if less

than a year) 4.58 17 4.38 13 5.25 4

answered question 50 30 20

skipped question 6 1 2

10. Approximately how many hours per semester of language teaching-related in-service training (e.g., workshops, lectures, conferences, orientations, etc.) do you participate in?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count none 4.1% 2 6.9% 2 0.0% 0 1-5 hours 10.2% 5 6.9% 2 15.0% 3 6-15 hours 24.5% 12 13.8% 4 40.0% 8 16-30 hours 28.6% 14 37.9% 11 15.0% 3 31 hours or more 32.7% 16 34.5% 10 30.0% 6 answered question 49 29 20 skipped question 7 2 2

11. What is the percentage of English as your language of instruction in class?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count less than 10% 0.0% 0 0.0% 0 0.0% 0 around 25% 4.0% 2 0.0% 0 10.0% 2 around 50% 32.0% 16 24.1% 7 45.0% 9 around 75% 24.0% 12 24.1% 7 25.0% 5 other (please specify the percentage) 32.0% 16 44.8% 13 15.0% 3 answered question 50 29 20 skipped question 6 2 2

12. Have you had any native/non-native co-teaching experience?

All Native Non-native

Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Response Percent Response Count Yes 85.7% 42 86.2% 25 85.0% 17 No 14.3% 7 13.8% 4 15.0% 3 answered question 49 29 20 skipped question 7 2 2

Based on the tables above, it is clear that overall there are more female ELT

male; while in the NET group, 11 out of 31 are male. The sampled teachers are quite young, especially the NET group, 18 out of 31 are 24 years or under. In terms of the educational background, much more NNETs have higher degrees (14 out of 22, or 63.6% have master’s degrees) than NETs (27 out of 31, or 87.1% have bachelor’s degrees). Most NNETs (15 out of 22 or 83.3% vs. 11 out of 28 or 39.3% of NETs) have taken TESOL-related courses and have teaching certificates (17 out of 22 or 85% vs. 15 out of 29 or 51.7% of NETs). More NNETs have higher average of years of teaching English (10.16 years) than NETs (7.68 years) do.

In comparison, NETs in the sample seem to spend more time on in-service training programs/workshops (22 out of 29, or 72.4% spend 16 to 31 hours per semester on average vs. 9 out of 20 or 45% in the NNET group). In terms of the language of instruction, it is obvious that NETs use more English in class (20 out of 29 or 68.9% use more than 75% of English in class) than do NNETs (8 out of 20 or 40% use more than 75% of English in class.

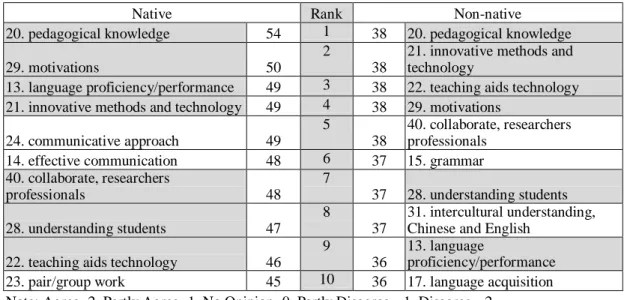

Section II. Question #13-40

Based on the 5-level scale, the scores were summed up for each of the 28 questions, and the result was presented in the following figures. Figure 1 was listed by a

descending order.

n Figure 1. Overall Scores (NETs + NNETs) of the Question #13 to 40 listed by a descending order

90 86 85 84 83 83 82 82 81 79 79 79 78 77 77 76 73 72 72 71 67 67 64 63 62 55 50 50 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 20. pedagogical knowledge 29. motivations 21. innovative methods and technolo 40. collaborate, researchers professionals 13. language proficiency/performance 24. communicative approach 22. teaching aids technology 28. understanding students 14. effective communication 15. grammar 31. intercultural understanding, Chinese and English 32. assessment 23. pair/group work 18. curriculum 30. social cultural diversity 33. variety of assessment 19. parent & society 17. language acquisition 26. order in classroom 25. local language explanations 27. drilling and practicing 35. socio-economic family background 39. relevant research 34. help prepare tests and exam 37. beliefs and values learning 38. professional training credentials 16. linguistic knowledge 36. communicating with parents

Overall Scores (Native + Non-native)

Note: an=47; bAgree=2, Partly Agree=1, No Opinion=0, Partly Disagree= -1, Disagree= -2 Note: an=53; bAgree=2, Partly Agree=1, No Opinion=0,