PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

On: 24 October 2010

Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 928470091]

Publisher Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Industry & Innovation

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713424563

The Persistence of Superior Performance at Industry and Firm Levels:

Evidence from the IT Industry in Taiwan

Yi-Min Chena; Feng-Jyh Linb

a Department of Asia-Pacific Industrial and Business Management, National University of Kaohsiung,

Kaohsiung, Taiwan b Department of Business Administration, Feng Chia University, Taichung, Taiwan

Online publication date: 21 October 2010

To cite this Article

Chen, Yi-Min and Lin, Feng-Jyh(2010) 'The Persistence of Superior Performance at Industry and Firm

Levels: Evidence from the IT Industry in Taiwan', Industry & Innovation, 17: 5, 469 — 486

To link to this Article: DOI:

10.1080/13662716.2010.510000

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2010.510000

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Research Paper

The Persistence of Superior

Performance at Industry and Firm

Levels: Evidence from the IT Industry

in Taiwan

YI-MIN CHEN* & FENG-JYH LIN**

*Department of Asia-Pacific Industrial and Business Management, National University of Kaohsiung, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, **Department of Business Administration, Feng Chia University, Taichung, Taiwan

ABSTRACT The industrial organization economics and the resource-based view of the firm have led to disagreements over the question as to which of firm performance at the industry and firm levels has persisted longer since the 1970s. Acknowledging that the IT industry in Taiwan has become very competitive and has demonstrated outstanding performance in the world since the 1990s, this study calculates the persistence in the incremental components of the effects on profitability, and tests hypotheses that conform to the above mainstream views of relative rates of persistence. A persistence partitioning model is fitted to a new data set, and the results show that the incremental effects of firms on profitability persist longer than the incremental effects of industry. In other words, the long-term competitive advantages of IT firms in Taiwan are more predictable and sustainable in regards to firm factors than for industry influences. These findings support the predictions of the resource-based view of the firm, and provide some implications for corporate strategy.

KEY WORDS: Persistence, profitability, IT industry, competitiveness of firms, industry structure

1. Introduction

The performance of the information technology (IT) industry in Taiwan during the last two decades has been outstanding (Chang and Yu, 2001; Saxenian and Hsu, 2001). Much of the conventional wisdom about how companies and nations compete—which often relies on factor endowments that enjoy a comparative advantage that is both competitively decisive and persistent over time—cannot explain the emergence of successful Taiwanese IT clusters such as those found in the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park (HSIP) that are

1366-2716 Print/1469-8390 Online/10/050469 – 18 q 2010 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/13662716.2010.510000

Correspondence Address: Yi-Min Chen, Department of Asia-Pacific Industrial and Business Management, National University of Kaohsiung, 700 Kaohsiung University Road, Nanzih, Kaohsiung 811, Taiwan. Fax: þ886 7 591 9430; Tel.: þ886 7 591 9241. Email: ymchen@nuk.edu.tw

Vol. 17, No. 5, 469–486, October 2010

located far from established centers of technology and skill in the world. Taiwan has been able to create a thriving semiconductor and electronics industrial cluster by creating an institutional framework and leveraging advanced technologies from around the world. This fact has led noted industry and innovation analyst John Mathews to aptly describe it as a “Silicon Valley of the East” (1997). The island’s experience is quite valuable for those emerging countries interested in creating a national policy and innovation strategy for transforming themselves from producers of low-value goods to producers of high-technology products. However, a study dedicated to persistence analysis on profitability differentials among Taiwanese IT firms has not yet been proffered. The majority of previous studies on Taiwanese IT competitiveness have been carried out from an industrial cluster perspective with little attention being paid to the question of the principal source of profits (industrial structure or organizational behavior) among firms. While clusters reveal that the immediate business environment outside companies is important, what happens inside companies plays a vital role as well.

Understanding the determinants of profitability differentials among firms is a key theoretical and empirical issue in the fields of industrial organization economics (IO) and resource-based views of the firm (RBV). IO models theoretically assume that industry structure shapes firm conduct, which in turn determines firm performance. Recently, the results of the IO research suggest that a reciprocal relationship is likely to exist between the external environment and the firm’s strategy that affects the firm’s performance (Henderson and Mitchell, 1997; Stimpert and Duhaime, 1997). Nevertheless, during the 1970s and 1980s, the IO studies were challenged by the strategic management perspective of RBV because of the inability of IO to explain intra-industry heterogeneity in terms of firm profitability. The RBV school argues that the IO insistence on making industry the main unit of analysis based on the structure – conduct – performance framework would render purely deterministic theories irreconcilable. Thus, strategic management researchers of RBV who adopt a flexible view of organizational and environmental change argue that many firms can adapt their strategies and capabilities as competitive environments change, and focus increasingly on individual firm factors and firm-specific idiosyncrasies in the accumulation of valuable, rare and specialized resources to explain differences in intra-industry performance (Wernerfelt, 1984; Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993).

Although the recent variance decomposition studies have tried to determine the relative importance of industry and firm effects on firm profitability (Schmalensee, 1985; Rumelt, 1991; Roquebert et al., 1996; McGahan and Porter, 1997, 2002; Hawawini et al., 2003; Hough, 2006; Short et al., 2007), IO and the strategic management perspective of RBV have led to disagreements for more than 60 years over what matters most to profitability. In addition, some researchers even use many terms for both “capabilities” (e.g. competencies and resources) and “competition” (e.g. industry structure and competitive markets), the basic theme of comparing levels of firm and industry effects is similar. Overall, there is little consensus as to whether organizational capabilities or market competition are more important in shaping firms’ actions and performance (Henderson and Mitchell, 1997).

Following the variance decomposition approach of firm profitability determinants, studies of persistence, the convergence process, on firm performance have recently become a key theoretical and empirical issue in the fields of IO and RBV (McGahan and Porter, 1999). In explaining the sources of firm profitability that vary from the norm in the long term, IO adherents based on the existence of industry heterogeneity argue that industry effects are

enduring, and observed firm effects arise because industrial structure characteristics such as impeding entry and limiting rivalry among participants favor business development. On the other hand, RBV adherents argue that firms achieve extraordinary profits in a line of business in the long term when they operate more efficiently through skill or luck than their competitors do, and that observed industry effects may arise when they are transient compared to differences among firms. Thus, the IO and RBV have different perspectives over the question of what persists longer in terms of firm performance at industry and firm levels.

Although studies on persistence have significantly advanced our understanding of the antecedents of firm profitability, they have tended to focus on firms with diversified business segments in a single country context (e.g. the USA or Spain). Recognizing important differences across countries in the extent to which profit differences persist (Geroski and Mueller, 1990), this study examines the persistence in the incremental components of industry and firm effects on profitability and tests the hypotheses that conform to the above mainstream views of relative rates of persistence by employing Taiwan’s business database for the IT sectors.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. After a brief review of IT industrialization in Taiwan in the next section, Section 3 proposes a decomposition model to examine the persistence of industry and firm effects on firm performance, which largely follows the approaches of Mueller (1986) and McGahan and Porter (1999). The data sample used is discussed in Section 4. Following the most common statistical methodology in Section 4, this study uses the decomposition procedure to examine the persistence of industry and firm effects on profitability. The results in Section 5 show that the incremental effects of the firm on profitability persist longer than the incremental effects of industry. In other words, the long-term competitive advantages of IT firms in Taiwan are more predictable and sustainable in relation to firm factors than to industry influences. Finally, this study concludes with a discussion of the results and some final remarks.

2. Explaining IT Industrialization of Taiwan

In view of their success in the global production networks, Taiwan’s IT sectors have demonstrated a powerful mechanism for industrial upgrading in remote locations like Taiwan, and have served as a good example of industrial clustering that illustrates geographic concentrations of interconnected firms and associated institutions in a similar field. For example, most Taiwanese IT manufacturers of semiconductors, motherboards, notebook computers and monitors to optical scanners, network modems and other computer-related products, are concentrated in the 50-mile industrial area around HSIP. In order to emulate the Silicon Valley achievements, HSIP was created to facilitate the leveraging of advanced technologies from around the world and accelerate the uptake and mastering of these technologies for Taiwanese IT private sector development (Mathews, 1997). Both HSIP in Taiwan and Silicon Valley in California are among the most frequently cited “miracles” of industrialization in the IT era, and HSIP appears as an exemplar of Marshallian external economies (Saxenian and Hsu, 2001). In addition, modeled quite explicitly on California’s Silicon Valley and its interaction with Stanford University (e.g. Bresnahan et al., 2001), HSIP likewise is located next to two of Taiwan’s leading engineering universities, National Chiaotung University and Tsinghua University (Mathews, 1997; Ernst, 2000).

These universities, backed by intensive efforts to upgrade the quality and quantity of technical training of engineers, are favoring a stronger push towards knowledge- and skill-intensive industrial development. Moreover, many Western observers have asserted that Taiwanese IT industries are internationally competitive because of cooperation among rivals, being sheltered from international competition, and selective government intervention in competition orchestrated by the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) and other governmental agencies (Kraemer et al., 1996; Mathews, 1997; Thorbecke et al., 2002). ITRI, which is located within HSIP, was established in 1973—when Taiwan was still seen by the rest of the world as a low-cost manufacturing haven—precisely as a catalyst to lift the country to a new level of technological sophistication (Mathews, 1997; Ernst, 2000).

With a mission to facilitate and accelerate the diffusion of technology, ITRI was an artificially induced industrial ecology oriented towards the creation and sustenance of clusters of new high-tech industries linked directly to the world’s most advanced centers of innovation (Mathews, 1997: 29). A unique IT industrial ecosystem in Taiwan not only brings together knowledge, technical and financial resources (Mathews, 1997), but also demonstrates a central premise of ecological theory that competition shapes the creation of capabilities, and most individual firms attempt to change with the environment with some of them doing so successfully (Hannan and Freeman, 1977; Aldrich, 1979; Carroll and Hannan, 1992). HSIP includes several hundred independent IT enterprises that produce all of the IT components once internalized within a single large IT corporation. Taiwanese IT firms employ common marketing channels and compete with each other in similar customer segments. Within each of these horizontal segments there is, in turn, increasing specialization of production and a deepening social division of labor (Saxenian and Hsu, 2001). One such example is the semiconductor industry. Independent manufacturers specialize in all facets of the business, from design of integrated circuits (ICs) to chip fabrication, packaging, testing and assembly. They also utilize chips in advanced IT products as well as work within different segments of the sector manufacturing materials and equipment. Independent accounts of the performance of producers in HSIP attest to their flexibility, speed and innovative capacity relative to their leading competitors (Ernst, 2000; Saxenian and Hsu, 2001). The IT industry in Taiwan illustrates that competition and vertical cooperation among independent firms account for rising productivity, innovation and new firm formation (Porter, 1990), and competition can coexist with cooperation because they both occur in different dimensions and among different players (Porter, 1998).

While a cluster of independent and informally linked companies and institutions is important to competition and to the definition of industry boundaries, the IT industry in Taiwan is a flourishing export-oriented and market-driven industry. Even publicly funded but privately operated demonstration ventures, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufac-turing Corporation (TSMC) and United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), were quickly privatized and floated on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (TSE) as they achieved commercial success. TSMC, the world’s leading silicon foundry, was founded as a joint venture with the Dutch multinational Philips in 1986 to produce chips for other companies that lacked their own fabrication facilities. Similarly, UMC, another of the world’s important silicon foundries, was founded in order to enter into exclusive manufacturing agreements with American semiconductor firms to produce a wide range of advanced chips (Mathews, 1997). These two leading semiconductor foundry suppliers became “locked into” separate and competitive OEM relationships with the leading US, European and Japanese IT companies. In addition,

the process of recombining technological resources into technological capabilities repre-sents a fusion of technology strategies at the firm level and international technology transfers at the level of the IT sectors as a whole (Cusumano and Elenkov, 1994). Overall, firm-level analysis can provide a dramatic demonstration of the proposition that resources are the source of a firm’s capabilities, and capabilities in turn are the source of a firm’s core competencies, which are the bases of competitive advantages (Brush et al., 2001).

While the creation, nurturing and guidance of HSIP has been entirely a result of the efforts of the Taiwan government and public sector institutions, TSMC and UMC in this cluster compete intensely to win and retain customers. Thus, the IT industry in Taiwan demonstrates that a cluster without vigorous competition among local firms will fail (Porter, 1998). However, even though TSMC and UMC have similar industrial structural characteristics and leveraged resources and capabilities in the same industry, it needs to be asked why there are significant profitability differences among them. Fortunately, the recent variance decomposition studies have tried to understand the determinants of profitability differences among firms since the mid-1980s. As noted by McGahan and Porter (2002: 835), the advantage of using decomposition of variance as a means of identifying the general importance of industry and firm effects on firm profitability is not only simple and statistically robust, but is also an important complement to studies on the “new empirical industrial organization”. To obtain generalized results, future variance decomposition studies may consider exploring non-US data and the relative importance of these effects within subpopulations (McGahan and Porter, 2002). In exploring new data, Khanna and Rivkin (2001) show that the relative importance of the effects may differ radically in non-US settings, and Chen and Lin (2006) and Chen (2010) revisit questions of whether firms’ performance is driven by industry or firm factors by considering the Taiwanese IT sectors. In line with this argument, studying the persistence of profitability at the industry and firm levels in the case of the IT industry in Taiwan has not yet been proffered. Therefore, with respect to the importance of both industrial structures and organizational capabilities to the development of IT industrialization in Taiwan, this study explores the persistence of sources to profitability differences among IT firms.

3. The Model and its Operationalization The Model

Recognizing that IT firms in Taiwan are not large corporations, this study uses the term “firm” to designate an autonomous competitive unit within an industry in contrast to the term “company” or “corporation”—a legal entity considered in previous research which owns and operates one or more business units (Rumelt, 1991; McGahan and Porter, 1997, 2002; Mauri and Michaels, 1998; Brush et al., 1999; Ruefli and Wiggins, 2003; Hough, 2006). Thus the term “firm effects” denotes both intra-industry dispersion among theoretical “firms” and differences among “firms” that are not explained by their patterns of industrial activities. In this regard, this study uses the term “firm effects” to include “corporate effects” and “business-unit effects”.

Recent researchers, including Mueller (1986), Cubbin and Geroski (1987), Jacobson (1988), Waring (1996), McGahan and Porter (1999), and Bou and Satorra (2007), have examined the persistence of firm profits, and beginning with McGahan and Porter (1999) the industry and firm effects have been decomposed into fixed components and

incremental components. Since persistence is defined as the percentage of a firm’s profitability in any period before period t that systematically remains in period t (Waring, 1996), persistence is directly relevant to questions of sustainability in the incremental components of effects (McGahan and Porter, 1999). Thus, this study defines persistence as the fraction of the incremental component at time t – 1 that also rises at time t.

Investigating the persistence of the firm and industry effects relies on the following steps in persistence analysis, which is similar to McGahan and Porter (1999). The profit of each firm is partitioned into year, industry and firm effects; we calculate the persistence in the incremental components of the effects on profitability; we test hypotheses that conform to the IO and RBV views of relative rates of persistence. First, we partition the profit of each firm into year, industry and firm effects by using the following descriptive model:

rit¼ m þ X t ftdtþ X it aitditþ bit: ð1Þ

In this model, rit is the accounting profit, that is, return on assets (ROA), of the firm in

industry i at time t. m denotes the average profit over all firms in all years. The term ftis the

increment to profit shared by all firms in year t. ait represents the incremental profit

associated with participation in industry i in year t. The dummy variable, dit, is equal to 1 if

the observation applies to industry i at time t, and 0 otherwise. bit is the residual in the

regression and the incremental profit specifically applied to the firm in industry i at time t. Second, the earlier of the introduced effects tends to capture the increment that is jointly determined when partitioning the profits (McGahan and Porter, 1999). In addition, the IO and RBV schools offer different predictions concerning the relative rates of persistence in the industry and firm effects. For example, an IO view suggests that incremental industry effects should persist longer than incremental firm effects. By contrast, a RBV view suggests that incremental firm effects should persist longer than incremental industry effects. Thus, if the order of entry of the estimates is tested under an IO view and the results show greater persistence in the incremental firm effects than in the incremental industry effects, we can conclude that the findings support the RBV view and do not test the other hypothesis.

Let us first estimate the coefficients in Equation 1 by introducing the means in the following order: year, industry and firm effects, and in the following procedures: (i) we estimate m by using the average profitability of all observations for firms where the average is weighted by size in assets; (ii) the year effects, ft, are obtained from the weighted

average of the residual performance of firms at time t after subtracting m; (iii) the estimates of the industry effects, ait, are obtained from the weighted average of the firm’s profit at time t

after subtracting both m and ft; (iv) the estimates of the firm effects, bit, are obtained from

subtracting all of the m, ft and ait. Then, we use the following equation to calculate the

profitability above or below the norm for each firm at time t : git¼ X t ftdtþ X it aitditþ bit ð2Þ

where ft, ait and bit represent the estimate for each of the years, the estimate for each

industry in each year and the estimate for each firm in each year, respectively. After these estimates are generated from Equation 2, each observation in the study is associated with a single year effect, industry-year effect and a firm-year effect.

Following Mueller (1986), Waring (1996), and McGahan and Porter (1999), we stipulate that, for each firm, the abnormal profit, git, and each of the effects in Equation 2, consists of a

fixed component and an incremental component. Thus git¼ Fgi þ Igit ð3aÞ fit¼ Ffi þ I f it ð3bÞ ait¼ Fai þ Iait ð3cÞ bit¼ Fbi þ I b it: ð3dÞ

Equations 3a through 3d denote the abnormal profit and each of the effects of two terms. In each equation, the first term represents a fixed component (F ) that is constant over the entire period, and the second term represents an incremental component (I ) that is the amount of the effect in a specified year that does not arise in any of the other years in which the firm is represented in the data set (McGahan and Porter, 1999). Following the previous studies, we also stipulate that the incremental component of abnormal profit may follow a first-order autoregressive process, which is of central interest in evaluating persistence:

Igit¼ riIgit 21þ k g it ð4aÞ Ifit ¼ rYr ;iIfit 21þ k f it ð4bÞ Iait ¼ rIn;iIait 21þ k a it ð4cÞ Ibit¼ rFm;iIbit21þ k b it: ð4dÞ

In Equations 4a through 4d, ri, rYr ;i, rIn;i and rFm;i represent the persistence of each

effect, which is the fraction of the incremental component at time t – 1 that also arises at time t. The terms kgit, kfit, kaitand kbitare random disturbances drawn from normal distributions with a mean of zero and unknown variances. Substituting the autoregressive values of Equations 4a through 4d into Equations 3a through 3d, we can represent the abnormal profit of each firm by means of the following expressions:

git¼ fgi þ rigit 21þ 1it ð5aÞ

fit¼ ffi þ rYr ;ifit 21þ tit ð5bÞ

ait¼ fai þ rIn;iait 21þ hit ð5cÞ

bit¼ fbi þ rFm;ibit 21þ uit: ð5dÞ

Each of the intercept terms, fgi, ffi, fai and fbi, in Equations 5a through 5d is a simple function of the fixed component, for example, fbi ¼ ð1 2 rFm;iÞFbi. The objective of this study

is to obtain the estimates of the persistence rate for each effect on profitability, ri, rYr ;i, rIn;i

and rFm;i. Judging whether there is a convergence process toward the mean ROA depends

on the following criteria (taking an example of the estimated rate of persistence in firm effects, rFm;i): (i) If rFm;i,j j, then we have evidence to show that the incremental1

components of the firm effect converge to zero over time. While the estimates of

0 , rFm;i,1 suggest that an especially good year at time t – 1 in terms of profit yields

positive benefits in year t, the estimates of 21 , rFm;i,0 suggest that an especially good

year at time t – 1 has a less-than-average ROA at time t. (ii) If rFm;i.j j, then we have1

evidence to show that the convergence process is incomplete. While a finding of rFm;i.1

implies an accumulation over time in incremental firm effects rather than a convergence to zero, a finding of rFm;i, 21 implies an amplifying oscillation over time in incremental firm

effects (McGahan and Porter, 1999).

The Operationalization

Previous studies on the relative importance of industry, corporate and business-segment effects have mostly relied on accounting returns such as ROA to measure profitability, which reflects historical profits relative to the book value of assets. ROA is calculated by dividing the operating income (i.e. earnings before interest and taxes) by total assets. Although many analysts have debated that ROA does not necessarily capture the net present value of all returns on investment (e.g. Fisher and McGowan, 1983), this study as in previous variance decomposition studies does not formulate an a priori hypothesis regarding the nature and direction of the bias caused by calculations of systemic risk and accounting conventions, and thus proceeds by using ROA as the performance measure.

4. Data Sample and Statistics Data

Data for Taiwan’s IT firms are collected from the Taiwan Economic Journal database (TEJ), which covers macroeconomic indicators and financial reports for 592 IT companies listed and traded on the Taiwan Stock Exchange (TAIEX). The TAIEX is the government authority that monitors the stock transactions of Taiwan’s listed firms.

The industrial classification system in Taiwan is different from that in the USA, one feature of the TEJ being that it does not offer business-level data at the 4-digit SIC code level—a traditional taxonomy that classifies firms into particular industry groups—but rather provides firm-level data at a 3-digit level of industry classification. The TEJ data set suffers from a lack of specificity in terms of industry classification, and this has two consequences for this study. First, since we assign firms according to their primary industry classifications, the analysis underestimates the industry effects to the extent that the firm is diversified beyond its primary industry, even when there are only a few cases. Second, the firm effects are likely to reflect both corporate- and business-level effects. In addition, since the TEJ provides only a 3-digit level of industry classification rather than the 4-digit SIC code for Taiwanese firms, and the firm effects include both corporate- and business-level effects, the panel effects that result in the volatility of profitability increasing with the level of disaggregation may not impact the results of the current study.

Sample

The sample set of IT sectors in Taiwan covers the five-year period from 2000 to 2004, extending from the growth stage into the shake-out stage of the Taiwanese IT industry.

Based on the nature of the fast-paced environment and the fierce business competition, what makes the Taiwanese IT industry even more dynamic is the development of state-of-the-art process technology that outpaces the traditional Moore’s law trend line (Wu et al., 2006). For example, the Taiwanese IC industry in the 1990s developed six new generations of process technology from 1.0 mm (micron) to 0.8, 0.5, 0.25, 0.18 and 0.13 mm. That six new generations were developed within 10 years implies that the ICs moved to smaller sizes at an accelerated pace (Wu et al., 2006). In other words, based on the fierce business competition and the shorter life cycle of each generation of process technology develop-ment, the five-year data period used in the current study has considered the business cycles and long-term industry effects of Taiwan’s IT industry.

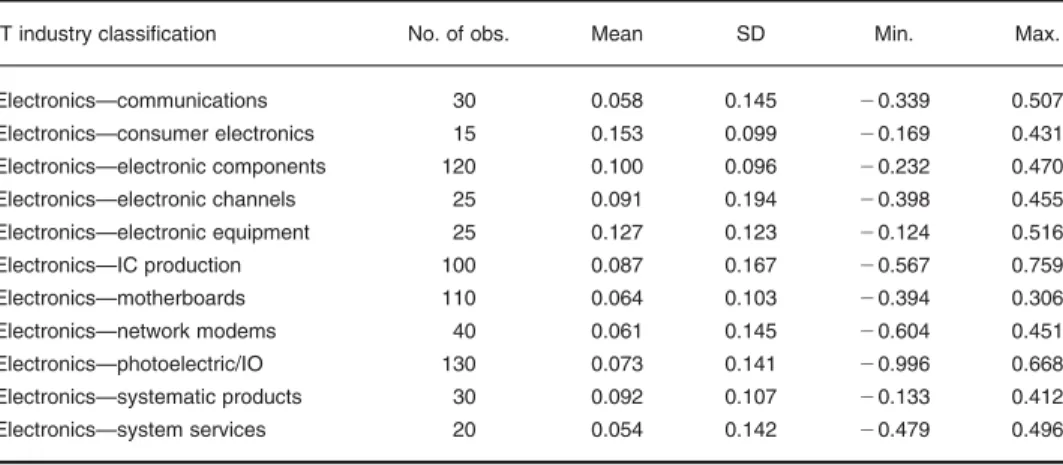

The sample was screened in various ways. In this study we excluded firms that did not contain a primary industry classification, firms that reported results with missing values and firms that were not reported to be active in the same industry classification over the five-year period. The final sample contained 645 observations for 129 firms across 11 sub-industry classifications. Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for Taiwanese IT industries for the years 2000 – 2004 across 11 sub-sectors. Although the mean values of the ROA across IT sub-sectors are positive, IT industries, led by the consumer electronics industry, have more average profits over the five-year period examined. In addition, the number of observations across IT sub-sectors ranges from 15 to 130, and it seems that the empirical results may be dominated by the developments in the dominant sub-sector. However, even in the dominant IT sub-sector with more than 100 observations such as electronic components, IC production, motherboards and photoelectric products, the profitability rates of individual sub-sectors across the IT industries vary quite significantly. In other words, from the descriptive statistics of Taiwanese IT industries, we are uncertain at this point whether the industry effect of the leading sub-sector may dominate the profitability differentials among firms.

Statistics

To calculate the persistence in the incremental components of the effects on ROA, we follow the previous assumption that the incremental component may follow a first-order

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of IT industries in Taiwan for the years 2000 – 2004

IT industry classification No. of obs. Mean SD Min. Max.

Electronics—communications 30 0.058 0.145 20.339 0.507 Electronics—consumer electronics 15 0.153 0.099 20.169 0.431 Electronics—electronic components 120 0.100 0.096 20.232 0.470 Electronics—electronic channels 25 0.091 0.194 20.398 0.455 Electronics—electronic equipment 25 0.127 0.123 20.124 0.516 Electronics—IC production 100 0.087 0.167 20.567 0.759 Electronics—motherboards 110 0.064 0.103 20.394 0.306 Electronics—network modems 40 0.061 0.145 20.604 0.451 Electronics—photoelectric/IO 130 0.073 0.141 20.996 0.668 Electronics—systematic products 30 0.092 0.107 20.133 0.412 Electronics—system services 20 0.054 0.142 20.479 0.496

autoregressive process, AR(1). McGahan and Porter (1999) show that the biased estimates of the persistence rate yielded by ordinary-least-squares (OLS) estimation can be corrected by using the formula developed by Nickell (1981), and conclude that the OLS estimation is more efficient than Nickell’s formula. Since there is no significant difference between the OLS estimates and the unbiased estimates, we only adopt the OLS estimation, collect the estimates of the persistence rate from the firms in our data set, and average across firms by weighting each persistence estimate by the inverse of the variance of the estimate.

In order to calculate the sampling variance of the estimate of rFm;i, for

example, the current study follows the standard formula for the sampling variance, that is, Var ðrFm;iÞ ¼ sb2=ðn £ Var ðbitÞÞ, and the standard formula for the population variance

with the inclusion of the estimated persistence rate, est ðrFm;iÞ, that is, sb2¼ ðnVar ðbitÞ 2

est ðrFm;iÞ2nVar ðbit21ÞÞ=n 2 2, where n represents the number of years of firm data. This

approach is also based on the McGahan and Porter (1999) study. By substituting the latter formula for the population variance into the former expression, the sampling variance of the persistence estimate of rFm;iis given by

Var ðrFm;iÞ ¼

Var ðbitÞ 2 estðrFm;iÞ2Var ðbit 21Þ

ðn 2 2ÞVar ðbit21Þ

: ð6Þ

From the previous literature, the IO and RBV schools have different views regarding the estimated rates of persistence for the incremental components of the industry and firm effects, that is, between rIn;i and rFm;i. While the IO school suggests that there is greater

persistence in the incremental industry effects than in the incremental firm effects, that is, rIn;i.rFm;i, the RBV school suggests that there is greater persistence in the incremental

firm effects than in the incremental industry effects, that is, rFm;i.rIn;i. This investigation

uses the t-statistic to test these hypotheses of significant differences between the pair of persistence estimates as implied under the IO and RBV views. If the empirical results are consistent in both sets of estimates, then we interpret the IO and RBV perspectives of the persistence of profitability as being robust.

5. Empirical Results

Using the TEJ database, we test whether the magnitude of the firm and industry effects are sensitive to profitability. Table 2 shows the empirical results of the estimated effects and persistence rates, which are obtained by introducing the means in the following order: the year, industry and firm effects. This order of entry adheres to the IO view. The first section in Table 2 refers to the average estimates of the fixed and incremental components of the effects, and the second section shows the estimated rates of persistence of the effects. Even with the effects being estimated in an order that is most consistent with the industry view, the second section of Table 2 reports the OLS estimates of persistence in the incremental effects and shows that the incremental component of the firm effect is estimated to persist at an average rate of 0.128 per cent, which is greater than that of the industry effects, 2 0.206 per cent. The estimated persistence rate of the firm effect is between 0 and 1, which suggests that the firm effect at time t – 1 year for a firm yields positive benefits for the next year t as well. The estimated persistence rate of the industry effect and the year effect lies between 2 1 and 0, which suggests that the industry effect and year effect at time

Table 2 . Persistence results McGahan and Porter (1999) Current Year Industry Corp. a Firm Sum Year Industry Firm Sum Estimated effects in per cent Average 0.026 1.978 0.741 5.722 8 .468 1.845 1.752 6.661 10.258 Standard deviation 1 .228 6.339 6.093 11.125 11.256 1.571 2.717 7.867 9.963 Average fixed component 1.444 1.139 2.591 9.176 7 .217 0.288 0.308 2 3.010 1.446 Average incremental component 2 1.488 1.194 2 2.230 2 3.982 0 .779 0.006 0.148 0.605 2 2.808 Persistence rate Average OLS estimate 0 .684 0.818 0.536 0.479 0 .537 2 0.041 2 0.206 0.128 0.314 Std d ev. OLS estimate 0 .223 0.330 0.140 0.283 0 .213 0.500 0.487 0.445 0.404 aCorporate-parent effects refer to the effects o f firms from the same corporation.

t – 1 year for a firm yields a less-than-average effect in year t. Overall, that the absolute values of these estimated persistence rates lie between 0 and 1 implies that the conver-gence process is complete and moves toward the mean profit in the long run.

The average absolute value of profits above or below the norm is 10.258 per cent, which is calculated by averaging the estimated effects for high performers and the negative of the estimated effects for low performers. In the first section of Table 2, the firm effects, industry effects and year effects contribute 6.661, 1.752 and 1.845 per cent to the average difference from the norm, respectively, and it should also be noted that the standard deviation of the firm effects is larger than that of the industry effects. The fixed component of firm effects is greater in absolute value terms than the year and industry effects, and is opposite in sign to the effect itself. As a result, the incremental year, industry and firm components are small in relation to each of the effects. To further test the hypotheses between the persistence of the incremental components of the industry and firm effects, we calculate a t-statistic for the distribution of differences between the pair of persistence estimates. The empirical results show that an aggregated t-statistic of 6.23 rejects the null hypothesis that incremental firm effects persist at the same rate as incremental industry effects at the 99.9 per cent confidence level; thus, the incremental firm effects on profitability persist longer than the incremental industry effects. The results support the predictions of the RBV school.

6. Discussion

The findings from this research broaden and deepen our understanding of the variance decomposition study and how the persistence analysis of the incremental industry and firm effects is linked to the Taiwanese IT firms’ performance. Related studies by Chen and Lin (2006) and Chen (2010) have shown that firm effects dominate industry effects and their impact on profitability differentials among IT firms in Taiwan. However, a study dedicated to exploring the question of whether the competitive advantage of Taiwanese IT firms will be sustained longer than their influence on industry has not yet been proffered. Thus, the current study in addressing the issue of whether firm effects persist longer than industry effects advances our understanding of the antecedent of firm profitability.

The empirical results show that incremental firm effects on profitability persist longer than incremental industry effects. Thus, industry effects are found to be more unstable and unpredictable than firm effects in terms of the long-term performance of Taiwanese IT firms. This result is different from McGahan and Porter’s findings on persistence (1999) in that industry effects were found to be more sustainable than firm effects in the case of US firms. In addition, researchers such as McGahan and Porter (1997, 1999) who investigate the sources and persistence of performance differences among firms have most often analyzed industries in a broader context (i.e. many industries in a country), rather than sub-sectors within an industry. However, in order to obtain a deeper understanding of the processes that generate favorable and unfavorable effects at the industry- and firm-specific levels, McGahan and Porter (2002) have suggested that detailed studies at the sub-sectoral level are needed. Thus, the current findings of sub-sector IT firms are quite valuable for those countries interested in creating favorable industrial policies and innovation strategies to develop a high-technology industry. While industrial structural characteristics such as government initiatives and foreign technology transfers may have been necessary to foster IT industry development in Taiwan (Mathews and Cho, 2000), the current persistence

results indicate that these industry factors are mostly insufficient to determine Taiwanese IT firms’ long-term profitability. The most important reason is the phenomenon of industry dynamics that exists in Taiwan’s IT industry. Several underlying factors may explain the industrial dynamic environment related to the unsustainable results of industry effects on IT performance.

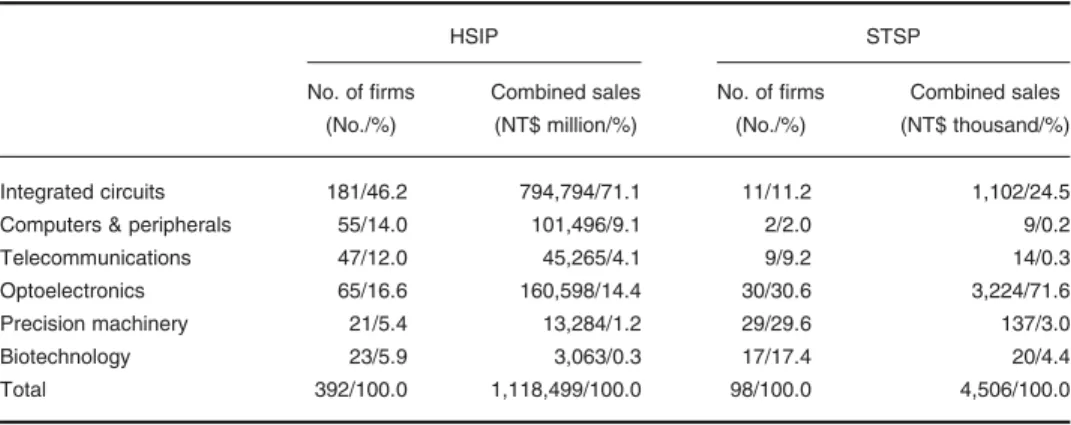

First, while industrial clustering is often cited as the source of Taiwan’s IT success (Chen, 2002), industrial clustering is a necessary but not sufficient factor accounting for a Taiwanese IT firm’s long-term performance. Following the success of the Taiwanese IT clusters in HSIP since the 1990s, the Taiwan government has continued to intervene in high-tech industry development by establishing many new science-based industrial parks and providing considerable resources and manpower to achieve a superior production environment that can then contribute to overall economic development. For example, HSIP was established in 1980 with a primary goal to develop the semiconductor industry, and the Southern Taiwan Science Park (STSP) was established in 1996 with its primary goal being to develop the optoelectronics industry, and Central Taiwan Science Park (CTSP) was established in 2007 with a primary goal to develop aviation, precision machinery and optoelectronics. A comparison of HSIP and STSP in terms of the number of firms in the park and the combined sales by each high-tech industry, provided in Table 3, indicates that industrial clustering has a high degree of industrial overlapping between the two parks even with different primary goals. This high-level industrial similarity increases inter-firm competition in the international markets, and makes high-tech firms’ long-term profitability more volatile. Therefore, we argue from the findings of unsustainable industry effects that inappropriate government interventions in establishing many similar industrial parks may impact firms’ long-term profitability. This study serves as a useful reference for countries wishing to adjust their industrial policies related to industrial clustering and the firm’s long-term profitability.

Second, while endogenous growth theory and innovation theory have stressed the importance of knowledge spillovers in favoring industrial clustering, Tsai (2005) finds that substantive sectoral and spatial knowledge spillovers are the major motivating forces for the regional concentration patterns of Taiwanese IT industries. Theoretically, the role of knowledge spillovers across firms can generate increasing returns and ultimately economic

Table 3. Number of firms and combined sales in HSIP vs. STSP for the year 2006

HSIP STSP No. of firms (No./%) Combined sales (NT$ million/%) No. of firms (No./%) Combined sales (NT$ thousand/%) Integrated circuits 181/46.2 794,794/71.1 11/11.2 1,102/24.5 Computers & peripherals 55/14.0 101,496/9.1 2/2.0 9/0.2 Telecommunications 47/12.0 45,265/4.1 9/9.2 14/0.3 Optoelectronics 65/16.6 160,598/14.4 30/30.6 3,224/71.6 Precision machinery 21/5.4 13,284/1.2 29/29.6 137/3.0

Biotechnology 23/5.9 3,063/0.3 17/17.4 20/4.4

Total 392/100.0 1,118,499/100.0 98/100.0 4,506/100.0

Note: HSIP ¼ Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park; STSP: Southern Taiwan Science Park.

growth (Griliches, 1986; Romer, 1986; Grossman and Helpman, 1991; Krugman, 1991). However, a substantial degree of knowledge spillovers across firm boundaries in Taiwanese IT industries reveals not only the advantage of collaborative learning and information sharing, but also the disadvantage of closely substitutable innovations among firms and the lack of a solid foundation in tech infrastructure to respond to the environment of high-tech dynamism, which renders the industrial clustering advantage and the firms’ long-term performance somewhat fragile.

In addition, successful industrial clustering has also spurred the emergence of high-tech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) clustering into industrial parks, and has initiated a radical shift to a more fragmented industrial structure organized around networks of increasingly specialized producers. For example, once internalized within a single large corporation, independent Taiwanese enterprises specialize in each production process of the semiconductor industry such as chip design, fabrication, packaging and testing. While this vertically disintegrated industrial system in Taiwanese IT industries provides opportunities and networks for mutual learning and information diffusion, independently specialized IT firms are more dependent on the collaborative R&D efforts both within and between industries to stimulate innovative activity, rather than as the result of individual efforts (Tsai, 2005). Therefore, although knowledge spillover effects are different for different sub-sectors within Taiwanese IT industries (Tsai, 2005), we argue that a vertical disintegration system of Taiwanese IT industries stimulating intra- and inter-industry know-ledge spillovers may distort the timing and willingness of direct R&D investments and impact the individual firm’s long-term profitability.

Finally, a vertical disintegration system for Taiwanese IT industries not only provides the advantage of flexible specialization and mutual learning between different firms in the production process, but also reveals the disadvantage of strong pressures on pricing from their customers, usually the world’s largest IT-brand companies. Driven by this vertical disintegration system, the world’s largest IT-brand companies have since the early 1990s not only engaged in foreign direct investment, but have also resorted to the offshore outsourcing of production to meet the trend towards globalization. As many brand marketers have tended to concentrate their core competencies on brand-name resources and R&D and to outsource the remainder of the value chain to the global supply chain, the landscape of IT industrial competition has consequently been reshaped since the late 1990s. For example, to allow customers to choose what they want, when and how, and at the lowest prices in the PC industry, Compaq outsourced every element of the value chain, with the exception of marketing, to Taiwanese subcontractors. By doing so, Compaq handed over its production and inventory costs to these subcontractors, who were also required to produce and deliver sub-system products on tight schedules and in tune with the wide variety of consumer demands. Thus, the Taiwanese firms have had to ensure that everything was synchronized up and down the supply chain, but have also had competitive prices when facing a profound change in the industrial system and inter-firm competition within the industry. We argue from the results of unstable industry effects that a vertical disintegration system of Taiwanese IT firms in establishing global supply chains may increase inter-firm competition, weaken their bargaining power in the industrial system and impact firms’ long-term performance.

Faced with the above necessary but not sufficient industrial characteristics, industrial clustering, the state’s role in actively intervening in the industry’s structure, knowledge

spillovers, a vertical disintegration system and the strong bargaining power of IT brand marketers that may impact firms’ long-term profitability, most Taiwanese IT firms now rely on their intra-organizational capabilities to strategically respond to the tensions in different ways at different stages (Hsu, 2006).

7. Concluding Remarks

In considering whether the effects were sustained over the entire period, our results indicate that firm effects are able to generate positive incremental benefits in relation to profit in the future. In other words, firm effects were found to be more stable and predictable than industry effects in regard to the Taiwanese IT industry. Although corporate management by itself cannot build core competencies, which generally reside within an organization and consist in part of organizational routines (Nelson and Winter, 1982), Nelson (1991) argues that to some extent profitability differentials are the result of different strategies that are used to guide decision-making at various levels in firms, and top management may have an important role in targeting and helping to develop and sustain organizational capabilities (Castanias and Helfat, 1991). Thus, while corporate management and corporate strategy in theory have some impact on, but not complete control of, corporate-level factors that influence profitability (Bowman and Helfat, 2001), the current persistence findings indicate that these firm factors are mostly sufficient for determining the Taiwanese IT firms’ long-term profitability. Several underlying strategies may explain the RBV related to the sustainable results of firm effects on IT performance.

A vertical disintegration system of Taiwanese IT industries not only reveals the environment of industry dynamics, but also facilitates the adaptation of the agile strategy adopted by IT firms to its environment (Wu et al., 2006). First, when faced with rapid business cycles and dynamic long-term industry effects, Taiwanese IT firms have managed their strategies along the life cycle of the IT industry in response to the paradigm shift in their external environments and at the same time have shaped the industrial structure to favor their evolution. For example, while the Taiwanese foundry industry evolves along its life cycle from the embryonic stage to the growth stage and to the shake-out stage, the strategic focus of the foundry business model migrates from manufacturing-centric to technology-centric, to the current customer-centric (Wu et al., 2006). Thus, over the last two decades, the evolution of Taiwanese IT firms’ strategic initiatives corresponding to the industrial structural change not only implies a relatively shorter life cycle, but also illustrates that IT firms building competitive advantages over their competitors differ themselves along the cycle.

Second, although both TSMC and UMC in the 1990s entered into the growth stage of the Taiwanese IC industry, UMC abandoned its position as Taiwan’s leading integrated device manufacturer and became a dedicated wafer foundry provider in May 1995 after recognizing the potential benefits of the cost advantage of the foundry business model. While faced with an industry focus in the foundry business that was shifting from a manufacturing-centric focus to a technology-centric focus and TSMC’s dominance in the foundry business, UMC adopted a differentiation strategy in establishing partnerships with identified customers through joint ventures. On the other hand, to secure its leadership in market share and enlarge the gap in manufacturing capacity between TSMC and UMC, TSMC crystallized its focus on business practices such as process technology and manufacturing excellence, and adopted a merger and acquisition strategy to expand its

fabrication capacity to meet the projected increase in customer demand. Thus, such strategic changes and moves by TSMC and UMC illustrate the adaptation of an agile strategy to the competitive nature of customers’ demands for faster design cycles, shorter time-to-market and quality products, and the rapidly changing structure of the semiconductor industry worldwide (Wu et al., 2006).

Third, Taiwanese IT firms have “gone global” by re-deploying their production networks overseas so as to maintain their cost efficiency to better serve their customers since the mid-1990s (Chen, 2002). Since then, the competitive pressures from a vertically disintegrated industry system and an acute labor shortage and relatively high costs have eroded profit margins and triggered the moving of Taiwanese IT industries offshore. Although firms may establish different degrees of territorial linkages with their hosting regions at different times in different economic periods, Taiwanese IT firms in order to take advantage of learning and innovative capabilities act strategically in the internationalization process to buffer themselves from local disturbances and to exploit their competences or mobilize local resources to explore new business models (Hsu, 2006). For example, Acer Peripherals, renamed BenQ after 2003, relocated its plants to China in the mid-1990s, and adopted the strategy of “the hen brought the little chickens together with it” that convinced the whole subcontracting partner system to move together to expand their overseas operations. However, not all organizational configurations of Taiwanese IT firms were transmitted overseas. For example, the R&D department and certain products that needed high precision production processes, which local technical skills could not match, remained in Taiwan.

In addition, from the perspectives of corporate management and technological diversity, Chen (2010) used patents information from the US Patent Office to estimate the technological diversification of Taiwanese IT industry at the level of firm resources for knowledge-based relatedness, and found that both the specialized and diversified corporate technological strategies mattered to the development of IT firms in Taiwan. Overall, we argue from the findings regarding the sustainable firm effects that the adaptation of an agile strategy and a corporate technological strategy corresponding to a highly dynamic industry environment may impact the IT firms’ long-term profitability.

Finally, the distinct backgrounds and different entrepreneurial styles of firms’ leaders can explain the differences in technology firms’ behavior (Liu et al., 2005). In other words, the behavioral differences of Taiwanese IT entrepreneurs in exploring and exploiting organizational resources and technological systems provide evidence that corporate strategy matters to the firms’ long-term performance. Overall, the current findings of firm effects are more persistent in relation to profitability and yield more evidence in support of the idea that Taiwanese IT firms gained competitive advantage by deploying their intra-organizational capabilities, by strengthening their core competencies and by adopting different corporate strategies at different stages. This contrasts with the traditional top-down approach to global competitiveness across firm boundaries. To develop a more fine-grained study of cross-national comparisons of firm performance, future research could examine the same effects in industries other than the Taiwanese IT industry.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Industry and Innovation Editor-in-Chief Mark Lorenzen, members of the editorial board and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

References

Aldrich, H. E. (1979) Organizations and Environments (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall).

Barney, J. B. (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage, Journal of Management, 17(1), pp. 99 – 120.

Bou, J. C. and Satorra, A. (2007) The persistence of abnormal returns at industry and firm levels: evidence from Spain, Strategic Management Journal, 28(7), pp. 707 –722.

Bowman, E. H. and Helfat, C. E. (2001) Does corporate strategy matter?, Strategic Management Journal, 22(1), pp. 1 –23.

Bresnahan, T. F., Gambardella, A. and Saxenian, A. L. (2001) “Old economy” inputs for “new economy” outcomes: cluster formation in the new Silicon Valleys, Industrial & Corporate Change, 10(4), pp. 835 – 860.

Brush, C. G., Greene, P. G. and Hart, M. M. (2001) From initial idea to unique advantage: the entrepreneurial challenge of constructing a resource base, Academy of Management Executive, 15(1), pp. 64 –78.

Brush, T. H., Bromiley, P. and Hendrickx, M. (1999) The relative influence of industry and corporation on business segment performance:

an alternative estimate, Strategic Management Journal, 20(6), pp. 519 – 547.

Carroll, G. R. and Hannan, M. T. (1992) Dynamics of Organizational Populations (New York: Oxford University Press).

Castanias, R. P. and Helfat, C. E. (1991) Managerial resources and rents, Journal of Management, 17, pp. 155 – 171. Chang, C. Y. and Yu, P. L. (2001) Made by Taiwan: Booming in Information Technology Era (Singapore: World Scientific).

Chen, S.-H. (2002) Global production networks and information technology: the case of Taiwan, Industry and Innovation, 9(3),

pp. 249 – 265.

Chen, Y.-M. (2010) The continuing debate on firm performance: a multilevel approach to the IT sectors of Taiwan and South Korea, Journal

of Business Research, 63(5), pp. 471 – 478.

Chen, Y.-M. and Lin, F.-J. (2006) Regional development and sources of superior performance across textile and IT sectors in Taiwan,

Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 18(3), pp. 227 – 248.

Cubbin, J. and Geroski, P. (1987) The convergence of profits in the long run: inter-firm and inter-industry comparisons, Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4), pp. 427 – 442.

Cusumano, M. and Elenkov, D. (1994) Linking international technology transfer with strategy and management: a literature commentary, Research Policy, 23, pp. 195– 215.

Ernst, D. (2000) What permits David to grow in the shadow of Goliath? The Taiwanese model in the computer industry, in: M. Borrus, D. Ernst & S. Haggard (Eds), International Production Networks in Asia: Rivalry or Riches, pp. 108 –138 (London: Routledge).

Fisher, F. and McGowan, J. (1983) On the misuse of accounting rates of return to infer monopoly profits, American Economic Review,

73(1), pp. 82 –97.

Geroski, P. A. and Mueller, D. C. (1990) The persistence of profits in perspective, in: D. C. Muller (Ed.), The Dynamics of Company Profits:

An International Comparison, pp. 187 – 204 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Griliches, Z. (1986) Productivity, R&D and basic research at the firm level in the 1970’s, American Economic Review, 76, pp. 141 –154.

Grossman, G. and Helpman, E. (1991) Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Hannan, M. T. and Freeman, J. H. (1977) The population ecology of organizations, American Journal of Sociology, 82, pp. 929– 964. Hawawini, G., Subramanian, V. and Verdin, P. (2003) Is performance driven by industry- or firm-specific factors? A new look at the

evidence, Strategic Management Journal, 24(1), pp. 1 –16.

Henderson, R. and Mitchell, W. (1997) The interactions of organizational and competitive influences on strategy and performance,

Strategic Management Journal, 18(6), pp. 5 –14.

Hough, J. R. (2006) Business segment performance redux: a multilevel approach, Strategic Management Journal, 27(1), pp. 45– 61. Hsu, J.-Y. (2006) The dynamic firm – territory nexus of Taiwanese informatics industry investments in China, Growth and Change, 37(2),

pp. 230 – 254.

Jacobson, R. (1988) The persistence of abnormal returns, Strategic Management Journal, 9(5), pp. 415 – 430.

Khanna, T. and Rivkin, J. (2001) Estimating the performance effects of business groups in emerging markets, Strategic Management

Journal, 22(1), pp. 45 – 74.

Kraemer, K., Dedrick, J., Hwang, C.-Y., Tu, T.-C. and Yap, C.-S. (1996) Entrepreneurship, flexibility, and policy coordination: Taiwan’s

computer industry, Information Society, 12, pp. 215 –249. Krugman, P. R. (1991) Geography and Trade (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Liu, T.-H., Chu, Y.-Y., Hung, S.-C. and Wu, S.-Y. (2005) Technology entrepreneurial styles: a comparison of UMC and TSMC,

International Journal of Technology Management, 29(1/2), pp. 92 – 115.

Mathews, J. A. (1997) A Silicon Valley of the east: creating Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, California Management Review, 39(4), pp. 26 – 54.

Mathews, J. A. and Cho, D.-S. (2000) Tiger Technology: The Creation of a Semiconductor Industry in East Asia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Mauri, A. J. and Michaels, M. P. (1998) Firm and industry effects within strategic management: an empirical examination, Strategic

Management Journal, 19(3), pp. 211 –219.

McGahan, A. M. and Porter, M. E. (1997) How much does industry matter, really?, Strategic Management Journal, 18(1), pp. 15 – 30.

McGahan, A. M. and Porter, M. E. (1999) The persistence of shocks to profitability, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(1), pp. 143 – 153.

McGahan, A. M. and Porter, M. E. (2002) What do we know about variance in accounting profitability?, Management Science, 48(7), pp. 834 – 851.

Mueller, D. C. (1986) Profits in the Long Run (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Nelson, R. R. (1991) Why do firms differ and how does it matter?, Strategic Management Journal, 12(8), pp. 61 –74.

Nelson, R. R. and Winter, S. G. (1982) An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University

Press).

Nickell, S. (1981) Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects, Econometrica, 19(6), pp. 1417 –1426.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993) The cornerstones of competitive advantage: a resource-based view, Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), pp. 179 – 191.

Porter, M. E. (1990) The Competitive Advantage of Nations (New York: Free Press).

Porter, M. E. (1998) Clusters and the new economics of competition, Harvard Business Review, 76(6), pp. 77 –90.

Romer, P. M. (1986) Increasing returns and long-run growth, Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), pp. 1002 –1037.

Roquebert, J. A., Phillips, R. L. and Westfall, P. A. (1996) Markets vs. management: what “drives” profitability?, Strategic Management Journal, 17(8), pp. 653 – 664.

Ruefli, T. W. and Wiggins, R. R. (2003) Industry, corporate and business-segment effects and business performance: a non-parametric approach, Strategic Management Journal, 24(9), pp. 861 – 879.

Rumelt, R. P. (1991) How much does industry matter?, Strategic Management Journal, 12(3), pp. 167 – 185.

Saxenian, A. L. and Hsu, J.-Y. (2001) The Silicon Valley—Hsinchu connection: technical communities and industrial upgrading, Industrial

& Corporate Change, 10(4), pp. 893 –920.

Schmalensee, R. (1985) Do markets differ much?, American Economic Review, 75(3), pp. 341 – 351.

Short, J. C., Ketchen, D. J., Palmer, T. B. and Hult, T. M. (2007) Firm, strategic group, and industry influences on performance, Strategic

Management Journal, 28(2), pp. 147 –167.

Stimpert, J. L. and Duhaime, I. M. (1997) Seeing the big picture: the influence of industry, diversification, and business strategy on

performance, Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), pp. 560 – 583.

Thorbecke, E., Tung, A.-C. and Wan, H., Jr. (2002) Industrial targeting: lessons from past errors and successes of Hong Kong and

Taiwan, World Economy, 25(8), pp. 1047 – 1061.

Tsai, D. H. A. (2005) Knowledge spillovers and high-technology clustering: evidence from Taiwan’s Hsinchu Science-based Industrial

Park, Contemporary Economic Policy, 23(1), pp. 116 – 128.

Waring, G. F. (1996) Industry differences in the persistence of firm-specific returns, American Economic Review, 86(5), pp. 1253– 1265. Wernerfelt, B. (1984) A resource-based view of the firm, Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), pp. 171 – 180.

Wu, S.-Y., Hung, S.-C. and Lin, B.-W. (2006) Agile strategy adaptation in semiconductor wafer foundries: an example from Taiwan, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73(4), pp. 436 – 451.