行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

從歐盟制度設計、問題解決能力及選民能力剖析歐盟公民

之被代表性

研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 99-2410-H-004-028- 執 行 期 間 : 99 年 08 月 01 日至 101 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學國際關係研究中心 計 畫 主 持 人 : 盧倩儀 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 101 年 11 月 06 日

中 文 摘 要 : 歐盟的民主赤字問題經常被視為一個非議題﹕歐盟既非一個 國家﹐如何能用衡量一個國家民主程度的標準來衡量歐盟﹖ 況且表面上看似被剝奪了的公民影響決策之能力只不過是轉 換為歐盟機構的解決跨國問題的能力而已﹔因此論者常指 出﹕就廣義的民主或是公民所能享受的福祉角度來看﹐歐盟 並無所謂民主赤字問題。本研究以「公民被代表性」作為分 析歐盟民主之概念工具﹐企圖打破以「民主政治容器」之橫 向概念為唯一焦點之研究途徑﹐而以「民主政治對象」為分 析焦點之縱向概念來探索表面上看似被剝奪了的公民影響決 策之能力是否確實能轉換為歐盟機構的解決跨國問題的能 力。本文針對三項假說進行檢驗﹕(1) 歐盟之選民具有在選 舉中做判斷之選民能力﹔(2) 實證上﹐歐盟有具備了完善責 任鏈之代議制度﹔(3) 實證上﹐歐盟在責任鏈的反饋下能有 效為歐盟公民解決問題。其結論指出﹐由於缺乏將被犧牲的 民主代表轉換為問題解決能力之必要條件﹐歐盟公民之被代 表性呈現嚴重的淨流失狀態。為使歐盟被代表性維持在原有 水平﹐必須在制度設計上發揮更大想象力﹐促使選民能力獲 得大幅提昇﹐才能讓被犧牲的民主代表轉換為歐盟問題解決 能力。 中文關鍵詞: 歐盟﹐被代表性、責任、問題解決能力、選民能力

英 文 摘 要 : To what extent do EU policies reflect the interests of European citizens? Is the policy-making process of the EU, according to its design, equipped with the capacity to well represent the citizens? This article adopts a subject-centered—as opposed to the

traditional container-centered—approach and uses the concept of representedness to find answers for these questions. The conventional wisdom suggests that even though citizens lose some representedness under the design of the EU institutions, owing to the enhanced problem-solving capacity of the EU, the overall representedness of the European citizens remains the same. In this article I demonstrate that given the absence of conditions required to transform the loss of representedness into enhanced problem-solving capability, there is a severe net loss of citizen representedness in the EU. In order to bring citizen representedness back as much as possible to the Pareto front line, a lot more institutional

representedness. Given that low voter competence plays a crucial role in both the loss of and the failure to gain citizen representedness, future reforms of the EU need to pay close attention to the issue of voter competence.

英文關鍵詞: European Union, representedness, accountability, problem-solving capacity, voter competence

The Representedness of EU Citizens Analyzed through

Institution Design, Problem-Solving Capacity, and Voter

Competence

從歐盟制度設計、問題解決能力以及選民能力剖析歐盟公民之被代表性 Chien-Yi Lu

Associate Research Fellow

Institute of International Relations, National Chengchi University No. 64, Wan Shou Rd., Wen Shan District, 11666, Taipei, Taiwan

Telephone: (02) 8237-7369 e-mail: cyl@nccu.edu.tw 盧倩儀 副研究員 國立政治大學國際關係研究中心 11666 台北市文山區萬壽路 64 號 Telephone: (02) 8237-7369 e-mail: cyl@nccu.edu.tw

The Representedness of EU Citizens Analyzed through

Institution Design, Problem-Solving Capacity, and Voter

Competence

Abstract

To what extent do EU policies reflect the interests of European citizens? Is the policy-making process of the EU, according to its design, equipped with the capacity to well represent the citizens? This article adopts a subject-centered—as opposed to the traditional container-centered—approach and uses the concept of representedness to find answers for these questions. The conventional wisdom suggests that even though citizens lose some representedness under the design of the EU institutions, owing to the enhanced problem-solving capacity of the EU, the overall representedness of the European citizens remains the same. In this article I demonstrate that given the absence of conditions required to transform the loss of representedness into enhanced problem-solving capability, there is a severe net loss of citizen representedness in the EU. In order to bring citizen representedness back as much as possible to the Pareto front line, a lot more institutional creativity is required to mend the loss of citizen representedness. Given that low voter competence plays a crucial role in both the loss of and the failure to gain citizen representedness, future reforms of the EU need to pay close attention to the issue of voter competence.

Key Words: European Union, representedness, accountability, problem-solving capacity, voter competence

從歐盟制度設計、問題解決能力以及選民能力剖析歐盟公民之被代表性 摘要 歐盟的民主赤字問題經常被視為一個非議題﹕歐盟既非一個國家﹐如何能用衡量 一個國家民主程度的標準來衡量歐盟﹖況且表面上看似被剝奪了的公民影響決 策之能力只不過是轉換為歐盟機構的解決跨國問題的能力而已﹔因此論者常指 出﹕就廣義的民主或是公民所能享受的福祉角度來看﹐歐盟並無所謂民主赤字問 題。本研究以「公民被代表性」作為分析歐盟民主之概念工具﹐企圖打破以「民 主政治容器」之橫向概念為唯一焦點之研究途徑﹐而以「民主政治對象」為分析 焦點之縱向概念來探索表面上看似被剝奪了的公民影響決策之能力是否確實能 轉換為歐盟機構的解決跨國問題的能力。本文針對三項假說進行檢驗﹕(1) 歐盟 之選民具有在選舉中做判斷之選民能力﹔(2) 實證上﹐歐盟有具備了完善責任鏈 之代議制度﹔(3) 實證上﹐歐盟在責任鏈的反饋下能有效為歐盟公民解決問題。 其結論指出﹐由於缺乏將被犧牲的民主代表轉換為問題解決能力之必要條件﹐歐 盟公民之被代表性呈現嚴重的淨流失狀態。為使歐盟被代表性維持在原有水平﹐ 必須在制度設計上發揮更大想象力﹐促使選民能力獲得大幅提昇﹐才能讓被犧牲 的民主代表轉換為歐盟問題解決能力。 關鍵字﹕歐盟﹐被代表性、責任、問題解決能力、選民能力

The Representedness of EU Citizens Analyzed through

Institution Design, Problem-Solving Capacity, and Voter

Competence

The debate on the democratic deficit of the EU is entering into a cul-de-sac. Those who claim that the EU suffers from a democratic deficit consider the Union as wanting in democratic legitimacy. Those who see little problem with the democratic performance of the Union point out that using the criteria for a state to assess the Union in terms of its democracy performance is both inappropriate and misleading. These two views are incompatible with one another only if our notion of democracy is fixated on the political entities and ignores the people. The point of democracy is primarily about people and only secondarily about institutions. If ‘a key characteristic of a democracy is the continuing responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens, considered as political equals’ (Dahl, 1971: 1), then even when the relevant (levels of) institutions/entities are overlapping, entangled, or even messy, the focus should remain on citizens themselves. From a citizen’s perspective, as long as public policies maximize their welfare, it matters little at which level these policies are made. Therefore, to disentangle the theoretical deadlock concerning democratic deficit, this paper proposes to shift the focus back onto the citizens. Instead of analyzing the containers—state, EU, or both—of democracy and fighting over which level matters more, this paper uses the concept of representedness to evaluate the degree to which citizens’ preferences are maximized through policy making under the simultaneously present national and European rules. As such, this study is

subject-centered as opposed to the traditional container-centered approaches. After

elaborating on the concept of representedness, I examine the conventional wisdom which implies that EU citizens have lost some representedness due to the transfer of decision-making power from national governments to the EU but have gained back representedness through the enhanced problem-solving capability found in the supranational body. My analysis shows that whereas a significant loss of citizen representedness did take place, conditions required to transform the loss into enhanced problem-solving capability are missing. Noting that low voter competence and lack of information play a central role in the overall low level of representedness, I conclude by stressing the importance of enhancing voter competence in the EU.

I. Concept of Representedness

translate citizens’ preferences into public policies. Whether being responsive to voters’ immediate preferences is consistent with the long-term, general public interests is less a concern (Setälä, 2006). In contrast, the liberal view—the view this paper subscribes to—treats the capacities, skills, and judgments of representatives as crucial elements of democratic representation (Sartori, 1987: 170, 384–385). If ‘representation means acting in the best interests of the public’, (Pitkin, 1967; Manin, Przeworski and Stokes, 1999a), then representedness can be defined as ‘the degree to which public policies reflect the interests of the governed’. At which level the public policies are made is less a concern than the degree to which these policies represent citizens’ interests. Since public interests are notoriously difficult to define, measuring representedness becomes problematic. One can, however, identify mechanisms /conditions that have been widely taken as making representation—however difficult to measure—work in modern democracies and use them as a tool in assessing representedness. In general, the more strongly present these mechanisms and conditions are the higher the level of representedness would be. Such an approach allows us to compare the representedness of citizens under different institutional settings and decision-making levels.

This approach recognizes that citizens’ interests are necessarily modified or constrained by the broader international environment, with globalization and regionalization being the most notable constraints. When globalization/regionalization result in problems that can only be solved internationally/supranationally, the form of democratic representation necessarily becomes less direct. Less direct representation, however, does not automatically translate into decreased representedness. If delegating power to international/supranational institutions for the purpose of enhancing transnational problem-solving capacity serves the interests of the citizens, then the representedness of the citizens is maintained. In other words, with the presence of efficient supranational institutions, where citizens lose in relatively direct representation/participation, they gain it back by being served by an albeit distant but more capable problem-solving policy-making body. This trade-off relationship is demonstrated in Figure 1. The Pareto front line denotes a perfectly efficient regional integration in terms of democratic legitimacy: each loss at the front of relatively direct democratic representation is accounted for at the front of problem-solving capacity. When forsaken representation is not compensated by gains in problem-solving capacity, the representedness of the citizens can be said to have decreased. Efforts are then called for to either increase citizen involvement or increase supranational problem-solving capacity in order to meet the Pareto front line.

_______________________________________________________________________________ Figure 1: Trade-off Relationship between Relatively Direct Representation and

_____________________________________________________________________

One of the advantages of applying the subject/citizen-centered representedness approach to probe democratic representation in the EU is that, without placing the blame on either decision-making level, the approach simply helps to sort out whether there is need/room for improvement. Debates on democratic deficit too often slip into a quarrel over whether there is or there isn’t a democratic deficit; and if there is, the newly constructed edifice—the EU—has to take most of the blame. With a citizen-centered approach, the focus is shifted away from the macro-level to the individual joints and linkages in the overall governing system. Since the ultimate task of each joint and linkage in the system is to help bringing the final policy output as close to the interests of citizens as possible, the focal point of investigation would center on: If an individual joint/linkage has succeeded (or failed) in fulfilling its task? If an individual joint/linkage has helped to ensure that citizens are well represented or has it caused a blockage in the representative channels?

.

Ⅱ Institution Design and Loss of Representedness

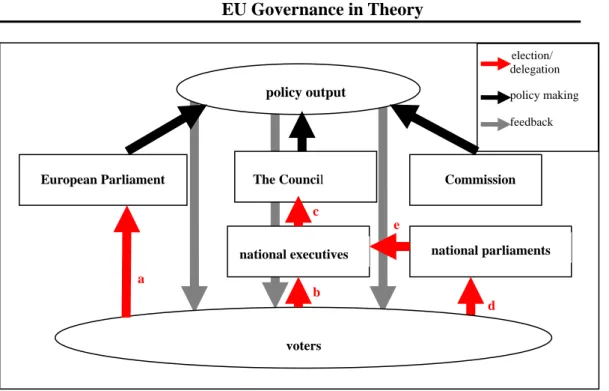

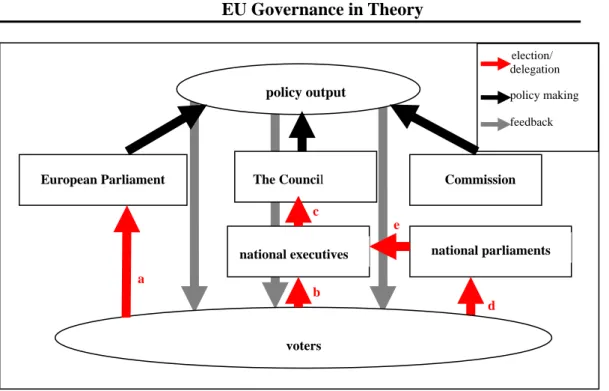

For Pitkin, a representative is someone ‘who is held to account, who will have to answer to another for what he does’ (Pitkin, 1967: 55). Hence, for any political system—whether parliamentary, presidential, or semi-presidential—a necessary condition for citizens to be well represented is working chains of accountability inherent to the system. Only with the presence of working chains of accountability can voters be assured that representatives are motivated to take actions that affect voters positively because voters will be able to sanction unqualified representatives retrospectively in elections. Figure 2 depicts how accountability generally works in

problem-solving capacity (direct) representation

________________________________________________________________ Figure 2: Chains of Accountability Worked through Representative

Institutions in Democratic States.

When public policies are made at the European level, accountability is supposed to work according to Figure 3.

election/ delegation policy making feedback policy output independent agencies executive parliament voters A B

_________________________________________________________________________ Figure 3: Chains of Accountability and Representative Institutions under

EU Governance in Theory

A detailed and in-depth comparison of the red (election/delegation) arrows in the two figures reveals that the chains of accountability work significantly less effectively when policies are made at the European level.

The institutional design of a democratic system needs to meet several conditions in order for the chains of accountability to work well (Manin, Przeworski and Stokes, 1999b: 47-49):

(1) Voters must be able to assign the responsibility for policy outcomes. (2) Voters must be empowered to throw out the rascals.

(3) Politicians must want to be reelected.

(4) Presence of the opposition that can monitor policy-making and inform citizens.

(5) Presence of the media that can monitor policy-making and inform citizens. (6) Presence of instruments for voters to reward and punish those in charge of

policy-making.

Whereas no democratic country was ever able to establish political institutions that meet all these conditions, it is at least possible to compare the

degree to which these conditions are satisfied in different contexts.

Before supranational institutions took over policy-making power in an issue area, citizens determine who the policy makers—and hence the likely direction of policies based on past experiences—should be through elections (arrows A and B

election/ delegation policy making feedback

policy output

European Parliament The Council Commission

national executives national parliaments

voters a b e c d

in Figure 2). Once the decision-making power is shifted into the hands of supranational institutions, as arrows a-e in Figure 3 demonstrate, it becomes extremely difficult for citizens to throw out the rascals because it becomes impossible to identify the persons or parties responsible for bad policies even if voters understand policy implications. If representatives are motivated to make good policies because voters posses the power to sanction unqualified representatives retrospectively in elections, then a close look at arrows a to e in Figure 3 would demonstrate that unqualified representatives have nothing to worry about when they are incapable of making good policies, since voters will not know whom to throw out even when they understand and dislike the policies that came out of the EU.

A. Arrow “a” in Figure 3:

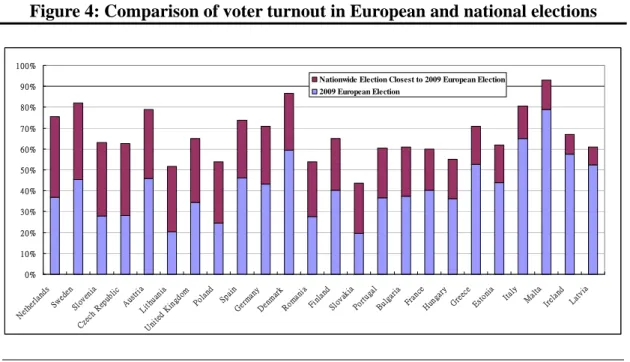

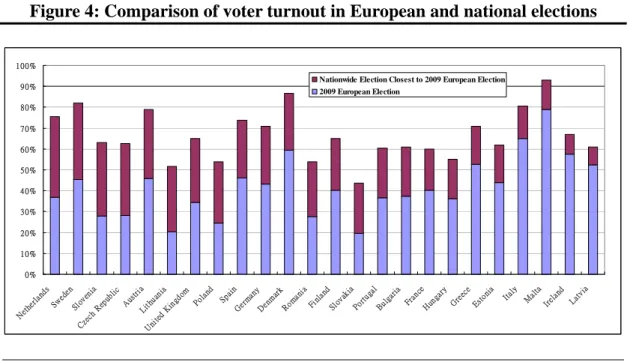

As is well known, the European elections are hardly determined by European issues at all. The elections are instead fought by domestic parties on national rather than European manifestoes, and candidates are selected by domestic party executives. Party competition does not yet exist at the European level. Being second-order elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980), the European elections often end up being more like the confident vote of the ruling parties in individual Member States. Consistent with the mid-term election phenomenon, the domestic ruling parties often fare worse than opposition and smaller parties in EP elections (Thorlakson, 2005: 469; Kritzinger, 2003). When candidates do not compete on European issues, voters are deprived of the opportunity to understand European affairs through elections and election campaigns. Figure 4 shows how much more indifferent voters are to European elections than they are to national elections. Even for voters who are more familiar with European issues, when where a candidate stands on a particular European issue is not even a concern in the campaign, voters are not given true choices between different approaches to EU governance. Given the mismatch between the institutional blueprint and the actual elections, it is not surprising that many MEPs, once elected, ‘not much is heard from them in the Member States’ (Papadopoulos, 2005: 449). In the longer term, when parties do not compete at the European level, rival policy agendas for EU governance cannot be formed other than according to national cleavages. This severely undermines the intended function of the EP according to design (Hix, 1998; Marsh, 1998).

_______________________________________________________________________________ Figure 4: Comparison of voter turnout in European and national elections

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Neth erla nds Swed en Slov enia Czec h Re publ ic Aust ria Lithua nia Uni ted Kin gdom Poland Spai n Ger man y Den mark Rom ania Finl and Slova kia Portu gal Bul garia France Hung ary Gre ece Esto nia Italy MaltaIreland Latv ia Nationwide Election Closest to 2009 European Election

2009 European Election

___________________________________________________________________________________ Notes :Countries where voting is compulsory are excluded from this figure. They include Cyprus, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Source: http://electionresources.org/; http://0rz.tw/lYAND; http://www.idea.int/vt/

___________________________________________________________________________________

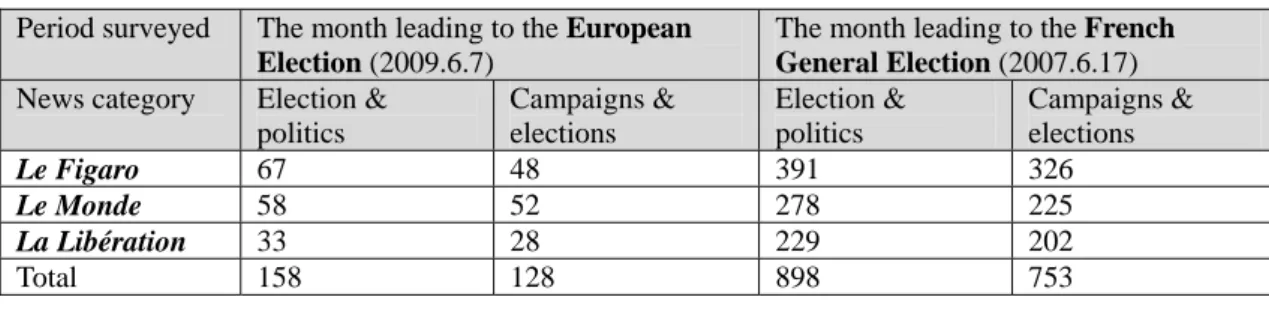

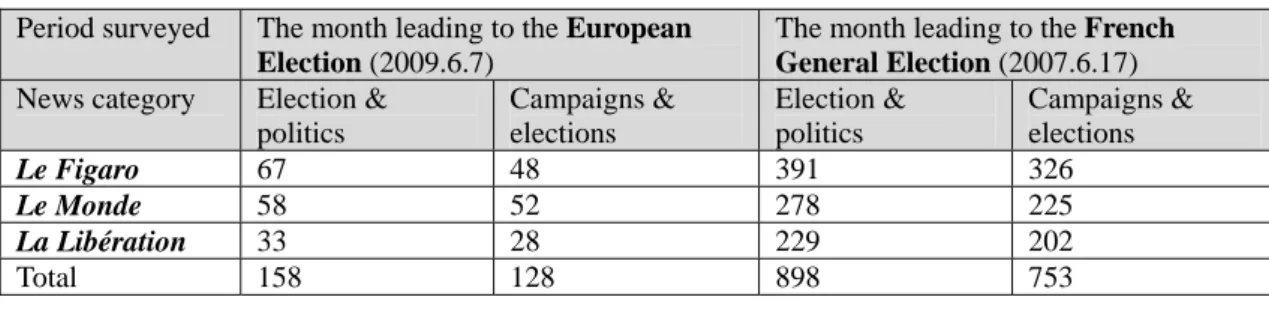

Tables 1-3 compare the amount of attention the media gives to national and European elections in selected member states. In the month leading to the 2009 European Election, the number of reports related to the election in quality newspapers is strikingly low in comparison with the amount of attention the closest national elections receive from the same newspapers in the month leading to the national elections. This pattern is found in the UK, France, and Ireland, and can be expected to be the case in other member states as well.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Table 1: Comparison of British Media Interests in 2009 European Election and 2010 British National Election:

Period surveyed The month leading to the European

Election (2009.6.4)

The month leading to the British

General Election (2010.5.6)

News category Election & politics Campaigns & elections Election & politics Campaigns & elections The Times 34 28 558 756 The Guardian 43 28 511 878 Daily Telegraph 17 11 482 743 Total 94 67 1551 2377 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis _____________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________ Table 2: Comparison of Irish Media Interests in 2009 European Election and

2007 Irish National Election:

Period surveyed The month leading to the European

Election (2009.6.5)

The month leading to the Irish

General Election (2007.6.17)

News category Election & politics

Campaigns & elections

Election & politics Campaigns & elections Irish Times 116 106 449 338 The Irish Independent 26 20 308 235 Total 142 126 757 573 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Table 3: Comparison of French media interests in 2009 European election and

2007 French general election:

Period surveyed The month leading to the European

Election (2009.6.7)

The month leading to the French

General Election (2007.6.17)

News category Election & politics Campaigns & elections Election & politics Campaigns & elections Le Figaro 67 48 391 326 Le Monde 58 52 278 225 La Libération 33 28 229 202 Total 158 128 898 753 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________

To the extent that the amount of reports/stories on a particular issue can indicate the degree of media interests in the issue, figures in Tables 1-3 demonstrate that the British media are about thirty times as interested in national elections as they are in European elections while the French media are almost six times as interested in national than European elections. Given that as much as 80% of national legislation originates from the EU, the fact that the media and voter attention still remain focused on the secondary policy-making venue rather than the primary policy-making venue causes serious problems for the working of democratic accountability (Mair, 2000: 45-46). Since media reports both reflect the low voter appetite and feed into voter indifference or even ignorance, this mutually reinforcing momentum creates further distance between policy-makers and voters and reduces the accountability chain into a lingering thread.

If European elections fail to be a channel through which voters can hold policy makers accountable, can citizen representedness be maintained through the Council via elections in the Member States? To begin with, elections are a blunt instrument for rewarding or punishing a party or a coalition even without the complication of multilevel governance: Voters have only one vote to cast, yet the target of evaluation consists of thousands of policies made by the same government (Manin, Przeworski, and Stokes, 1999b: 49-51). Under such circumstances, it is unrealistic to expect voters to reward or punish national governments based on decisions made regarding European affairs through national elections. In general, ministers are judged foremost by their ability to deal with domestic issues. Hence the Council owes its position to election only at several removes, and if European affairs are frequently absent in European elections, they will be even less significant in national elections (Katz, 2001: 56). As a result, even with the rule of transparency properly enforced, national ministers will still enjoy a high level of liberty with regard to the positions they take in the Council meetings. In short, as long as a medium between the citizens and European politics is absent, the voters are unlikely to vote out the ruling parties on the ground of European issues. In fact, contrary to the intention of the institutional design, and because of the difficulty for citizens to understand European affairs, national executives have long used the EU as the scapegoat for any unpopular policies.

As to the argument that, gathering in Brussels and acting in the capacity of the Council do not in anyway change the way national executives are controlled by national parliaments, the shift to majority voting in the Council makes the argument invalid. The veto power of each Member State used to be the single most legitimating element of the integration process (Weiler, 1991); the shift to majority voting now makes it even easier for national executives to get away with their actions or inactions. When the ministers can be outvoted in the Council, the power of the national parliaments to hold the executives accountable for the final policy product is seriously undermined. It also becomes even more unpractical to expect voters to hold their governments responsible for final EU legislations. Under QMV, the executives of nation A can actually be responsible for policies that are unpopular in nation B, but there is no way to hold the former answerable to the latter. Under such circumstances it is also even easier for national executives to use scapegoat strategies.

C. Arrows “d” & “e” in Figure 3:

If the power of the European voters to remove unsuitable elected officials from either the EP or the Council exists only in theory, can voters hold members of national

parliaments responsible for EU policy output? One of the rationales behind increasing the involvement of the national parliaments in EU decision-making is to enhance the understanding of the national parliamentarians of European affairs. While this is a welcoming development, its positive impact on the understanding of European affairs by voters will only be indirect. National parliamentarians do not consider it worthwhile to put energy into European affairs. Given how little voters understand and care about European affairs, such efforts would not be effective in catching voters’ attention and winning votes. ‘No demand, no supply’ can largely explain the ‘it’s not my job’ mentality among national parliamentarians. When the media and the voters are not interested, the national parliamentarians have no incentives to pursue the task of forcing the ministers to disclose all their positions and decisions taken in the Council.

In theory, therefore, the chains of accountability work along the arrows in Figure 3, yet in reality, the chains are barely existent, as is illustrated by arrows a-e in Figure 5. Citizens are bound to be affected by policies made by the EU once such a shift of decision-making level takes place, yet with the tenuous empowerment of citizens in receiving information, obtaining relevant knowledge, assigning responsibilities, and throwing out the rascals, it is very difficult to find evidence that citizens are being

represented.

________________________________________________________________ Figure 5: Chains of Accountability and Representative Institutions under

EU Governance in Reality _____________________________________________________________________ election/ delegation policy making feedback policy output

European Parliament The Council Commission

national executives national parliaments

voters a b e c d

.

Ⅲ Increased Problem-Solving Capacity and Gain in Representedness?

The previous section established that, in terms of institutional design, the lingering threads of accountability have resulted in a sharp decrease of citizen representedness in areas where the EU now holds the policy-making power. If this loss in representedness is compensated by an equally dramatic increase in decision-makers’ problem-solving capacity, then the overall representedness of citizens has been maintained at a level that requires little reform measures. In the debate of democratic deficit, one of the most commonly cited reasons for objecting the notion that the EU has a democratic deficit is that through the role of a regulatory state, the EU’s lack of input-oriented or procedural legitimacy is compensated by its output-oriented or consequential legitimacy resulted from its capacity to solve transnational problems. The EU is at a better position than the member states to resolve many of the problems faced by the states because of the transnational nature of these problems. Among other things, the supranational institutions of the EU are able to eliminate the problem of low credibility of intergovernmental agreements by monitoring and enforcing policies in individual member states (Majone, 1994, 1998, 1999). Governments that are under the pressure of election have no long-term credibility. Hence ‘delegation to an extra-governmental agency is one of the most promising strategies whereby governments can commit themselves to regulatory policy strategies whilst maintaining political credibility’ (Majone, 1996: 4). Moreover, given that regulation is a highly specialized type of policy making that requires a high level of technical and administrative discretion, institutions such as the European Commission and the European Central Bank are better equipped to undertake the task at the supranational level (Majone, 1994, 1996, 1998, 1999).

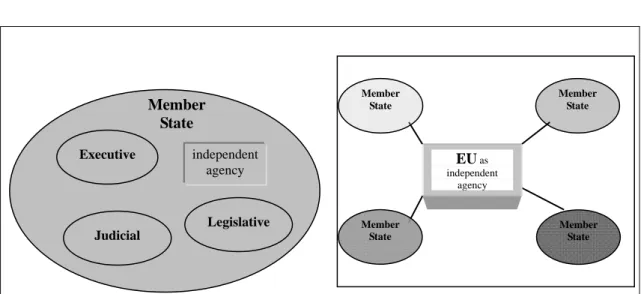

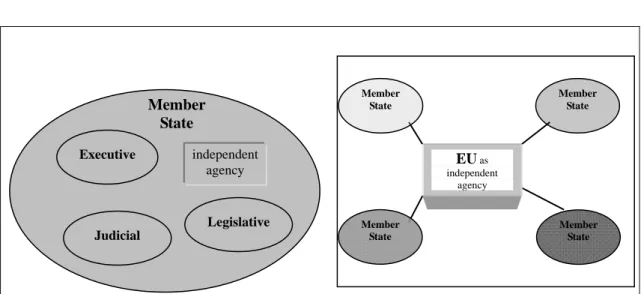

From this perspective, delegating power to non-parliamentarian bodies such as the European Central Bank and the Commission is far from ‘undemocratic’ but is consistent with the practice of most advanced industrial democracies (Moravcsik, 2002: 611-613). In fact, these regulatory institutions fulfill their roles exactly through their independence and autonomy from particular group interests and the pressures of votes. This impartiality required to make the commitments of the Member States credible is the role the European Commission in particular and the EU in general was asked to play. The relative insulation of Community regulators from the short-run political considerations is exactly the comparative advantage of EU regulation (Majone, 1994: 94). It is therefore more reasonable to view the EU as a regulatory state and stop comparing it with a sovereign state. It is due to the problem-solving capacity of this European regulatory state that the publics of the member states were able to achieve goals that they otherwise would have been unable to achieve. Hence,

the EU’s power to impose checks, constraints and corrections on majorities that ‘are not well-informed, rights-regarding, or fairly represented’ must be justified (Keohane, Macedo, and Moravcsik, 2009: 15), as it helps to block the tyranny of majority. If the EU is nothing more than a cluster of regulatory agencies solving transborder externalities that emanate from the integration process, then the EU should be deemed to be performing identical functions as a fourth branch of member state governments. Seen this way, the lingering accountability threads that worried us in Figure 4 should no longer be a concern, since the EU is supposed to be independent and left alone by voters, just like any regulatory agencies in a democratic country. Instead of conceiving of the EU as an undemocratic supranational bureaucracy, the Union should simply be conceived of as one of the many independent agencies of the member states (Figure 5).

_____________________________________________________________________ Figure 5: EU as an independent agency of the member states.

_______________________________________________________________________________

According to the regulatory/fourth-branch line of argument, what we thought to be a loss in representedness looking at the institutional design and tenuous accountability mechanism of the EU is after all not a real loss. Voters were meant to be bypassed in order for EU experts to do their jobs of solving collective problems for EU citizens. These experts are in any case not concerned about input from citizens but rely on their expert knowledge to make policies. Moreover, the transfer of policy-making power from national to European level only takes place in issue areas where non-majoritarian, independent regulatory agencies were already heavily depended

election/ delegation policy making feedback policy output independent agencies (including EU) executive parliament voters A B

upon to produce policies even before the transfer of the decision-making power to the European level took place.

Can the conclusion be drawn then that the representedness of citizens has been maintained when policy-making power is transferred to the EU the regulatory state? I demonstrate, by closely examining the EU’s role as the fourth branch of member state governments, that not only does the loss of representedness resulted from the weakened accountability mechanism still matter significantly, but the supposed gain in representedness through enhanced problem-solving capacity found in the European regulatory state is also very limited. First of all, there is little doubt that independence does not automatically results in better problem-solving capacity. Emphasizing expert knowledge and promoting non-majoritarian institutions or networks are seen merely as attempts to paper over the cracks in representative institutions (Bevir, 2010: 4) mainly because ‘…. it is based on the chimera of Pareto-optimal policies and presumes that EU policies always will be successful in achieving their aims’ (Katz, 2001: 58). Ober has pointed out that many well-known policy failures find their common root in the cloistered-experts approach: ‘Gather the experts. Close the door. Design a policy. Roll it out. Reject criticism.’ This policy-making formula is ‘both worse for democracy and less likely to benefit the community,’ because it ‘ignores vital information held by those not recognized as experts’ (2008: 1). It is not based on normative reasons—such as the concept that all those who are affected by a political decision should have a say in its making (Hilson, 2006: 56)—that the cloistered-experts approach is considered bad for democracy. Instead, from a utilitarian point of view, relying too heavily on like-minded experts would simply blunt democracy’s competitive edge. In considering the capacity to solve problems, it is commonly presumed that experts know the best and voters are ignorant. When it is the life experiences of the individuals that define the so-called problems, however, it is the less often recognized elite ignorance rather than voter ignorance that poses a more dangerous threat to good solutions. “The practical problem arises precisely because facts are never so given to a single mind, and because, in consequence, it is necessary that in the solution of the problem knowledge should be used that is dispersed among many people” (Hayek, 1945: 530, cited by Ober, 2008: 17). It is in this sense that Hayek has argued that knowledge possessed by every individual, not just the experts, is useful. (1945: 521, cited by Ober, 2008: 17).

It is true that in the domestic context independent agencies often produce non Pareto-optimal policies as well. The EU, however, is not only significantly even more likely to produce non Pareto-optimal policies, but such policies would also have a more severe negative impact on citizens than those produced by independent agencies within a state. Decision-making in the EU is often characterized as the lowest

common denominator of the member states. Such a result is inherently and logically contradictory with Pareto-optimal policies. Lowest common denominator reflects gives and takes determined by calculation of individual member states. Pareto-optimal results, in contrast, require calculation based on the notion of a European collective good. The chances for the aggregated individual preferences to correspond with the Pareto-optimal results of the collect are extremely slim. The Nice Treaty, for instance, is a compromise aimed at resolving intense disagreements between large and small states. Provisions to the liking of each group had to be included in the Treaty, resulting in the clumsy institutional framework that needed reform shortly after the Nice reform (Tsebelis and Yataganas, 2002). In other words, the conferees in Nice ‘were involved in a collective prisoners’ dilemma game and it was individually rational to insist on their own preferred criterion. As a result, they became collectively worse off by their inability to compromise’ (Tsebelis, 2008: 267).

Crucial to my claim that domestic independent agencies are less likely to make detrimental mistakes in comparison with the EU is the fact that, in spite of their independence, domestic non-majoritarian regulatory agencies are nonetheless ensconced in their own society. In the EU context, the secrecy of the Council, the weakness of political parties, the strength of special interests, and the distance of ordinary citizens from policy networks all render the decisions of independent agencies more detrimental when they are not Pareto optimal. Independent regulatory agencies are the fourth branch at the national level because they are an appendix to

the other three branches. No democratic systems have ever gained legitimacy based

on output legitimacy alone, and neither would the EU (McCormick, 1999). While the strengths of independent agencies are dependent on the isolation from voters, they are also dependent on the quality of the institutions of representative democracy (Bekkers et al., 2007). In fact, too many outputs may even serve to decrease rather than increase the legitimacy of the Union (Jolly, 2007).

Even though independent agencies are independent, such independence takes place within, and is related to, a demos. As much as this demos defines the parameters of the powers of the other three branches of state, so it should form the reference group for whom the independent agency makes decisions. In other words, independence does not exist in a vacuum; a relationship still exists between the insulated agencies and the demos. When the executive or legislative branch of a state delegates regulatory power to an agency, such delegation is deemed legitimate because it does not involve any modification of the demos. The agency responsible for maximizing the interests of the people has an unambiguous concept of who the people are. In assessing whether such agencies have achieved effective regulation, the questions ‘effective for whom’ and ‘Pareto efficient from whose perspective’ have

clear answers. Apart from well-functioning representative bodies, the existence of a lively public sphere is also crucial for keeping independent agencies abreast of the concerns of citizens and what comprises their ideas of the best interests of the nation.

The same conditions do not exist within the EU (Figure 6). The EU is neither equipped with well-functioning representative bodies nor a working public sphere to inform the EU (cum independent agencies isolated from voters) what constitutes the

best interests of the EU. Rather than relieving European voters of the anxiety with

regard to the democratic deficit problem, the interpretation of the EU as functioning just like any other given independent agency can raise a new alarm: Maximizing the interests of Europe as a whole (as defined/understood by a group of experts) may run counter to the interests of individual countries. Who is there to decide when and how one country’s interests should be sacrificed in order to achieve the greater good? Individual citizens’ interests are now determined by a group of experts who somehow – even in the absence of a European public sphere and a well-functioning representative body – just know where the best interests of these individuals – whether German, French, Slovenian or Polish – lie. The EU-as-fourth-branch thesis, in other words, fails to take into consideration that in democracies, even independent institutions ‘are anchored in the legitimacy of democratic mechanisms which link institutions to the public’ (Ward, 2004: 3).

_______________________________________________________________________________ Figure 6. Independent agencies and Demos—contrast between Member State and

EU _____________________________________________________________________ Executive Judicial Legislative independent agency Member State Member State Member State Member State Member State EU as independent agency

Even though independent, domestic agencies are ensconced in a demos and in touch with the public

While functioning as an independent agency, EU is not embedded in a demos. From citizens’ perspectives, therefore, EU rules are externally imposed.

The seemingly reasonable argument that the EU is but just one of the independent institutions of the member states as is shown in Figure 5 becomes problematic once we are reminded that these independent institutions are simultaneously shared by 27 countries. If making policies that reflect the long-term preferences of the governed can be challenging even for domestic independent institutions, the representedness of citizens is bound to fall dramatically when these institutions become transnational or supranational, shared by 27 societies but anchored in none. The loss of representedness resulted from weakened chains of accountability in the representative institutions is therefore not gained back by the creation of even the most uncorrupt, benign, ambitious, effective, and competent Eurocracy that is remote from the citizens.

What about the argument that the transfer of policy-making power from national to European level only takes place in issue areas where non-majoritarian, independent regulatory agencies were depended upon to produce policies even before the transfer of the decision-making power to the European level took place? The competence of the Union has continually expanded over the past decades. With the increased number of issue areas where qualified majority voting is the norm in the Council, only issues of taxation and foreign policy are now left exclusively in the hands of member state governments. It is, therefore, not true that the EU only intervene in areas where independent regulatory agencies were heavily depended upon to produce policies even before the transfer of the decision-making power to the European level took place. Still, Moravcsik insists that if an issue falls within the competence of the Union it must be because the issue is not salient for voters. Hence the EU is active in producing Europe-wide, binding policies only in the areas of trade, industry, standardization, soft power, foreign aid, and agriculture. In contrast, as far as fiscal, social welfare, health care, social security, and education policies are concerned, the member state governments continue to be the main policy-makers (Moravcsik, 2002: 603).

Given that EU competence expanded over time and citizens’ perceptions of issue salience change over time, the claim that the EU will always only deal with non-salient issues is questionable. Even if the observation that the EU deals only with non-salient issues is accurate, policy-making regarding these issues should still be subjected to democratic scrutiny. In fact, having excluded all salient issues, the only thing left to be scrutinized necessarily concerns these issues. To what extent is the EU capable of being responsive to citizens’ needs in these areas? In order to gauge the extent to which member state societies realize that the context of policy-making in such issues has now become European, I analyze media reports on these issues.

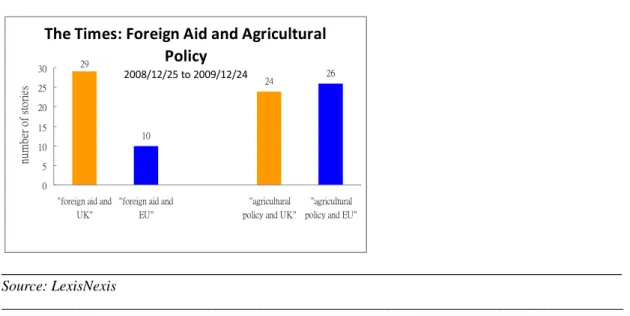

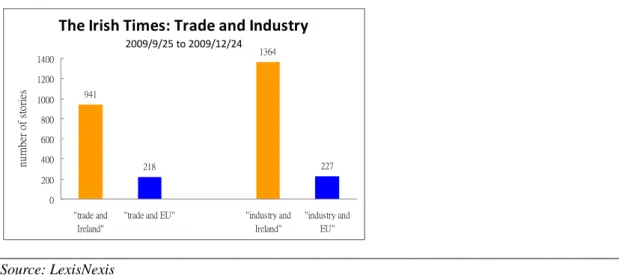

Figures 7-12 are comparisons of contexts (national or European) in which the British, Irish, and French media report the stories on the so-called non-salient issues. As these figures show, the contexts in which the non-salient, EU-in-charge issues are reported in the media continue to be national rather than European.

_______________________________________________________________________________ Figure 7: Contexts of Stories relating to Trade and Industry in The Times in a 3

month period The Times: Trade and Industry 2009/9/25 to 2009/12/24 1102 156 144 2403 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500

"trade and UK" "trade and EU" "industry and UK" "industry and EU" nu m b er o f st o ri es ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________

Figure 8: Contexts of Stories relating to Foreign Aid and Agricultural Policy in The Times in a 1 year period

The Times: Foreign Aid and Agricultural Policy 2008/12/25 to 2009/12/24 10 24 26 29 0 5 10 15 20 25 30

"foreign aid and UK"

"foreign aid and EU"

"agricultural policy and UK"

"agricultural policy and EU"

nu mb er o f st or ie s _____________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ Figure 9: Contexts of Stories relating to Trade and Industry in The Irish Times in

The Irish Times: Trade and Industry 2009/9/25 to 2009/12/24 941 218 1364 227 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 "trade and Ireland"

"trade and EU" "industry and Ireland" "industry and EU" nu m ber o f st or ie s ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________

Figure 10: Contexts of Stories relating to Foreign Aid and Agricultural Policy in The Irish Times in a 1 year period

The Irish Times: Foreign Aid and Agricultural Policy 2008/12/25 to 2009/12/24 35 6 40 36 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

"foreign aid and Ireland"

"foreign aid and EU"

"agricultural policy and Ireland"

"agricultural policy and EU"

nu m b er o f st or ie s ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________

Figure 11: Contexts of Stories relating to Trade and Industry in Le Figaro in a 3 month period

Le Figaro: Trade and Industry 2009/9/25 to 2009/12/24 142 119 181 154 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 "trade and France"

"trade and EU" "industry and France" "industry and EU" nu m b er o f st o ri es ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Figure 12: Contexts of Stories relating to Foreign Aid and Agricultural Policy in

Le Figaro in a 1 year period

Le Figaro: Foreign Aid and Agricultural Policy 2008/12/25 to 2009/12/24 113 132 17 20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

"foreign aid and France"

"foreign aid and EU" "agricultural policy and France" "agricultural policy and EU" nu m b er o f st or ie s ___________________________________________________________________________________ Source: LexisNexis ___________________________________________________________________________________

To sum up, the above analysis challenges the belief that the overall representedness of citizens has not decreased due to the increased problem-solving capacity of the EU. Among other things, independence and expertise do not automatically translate into problem-solving capacity. Twenty-seven societies sharing one independent agency not embedded in any of them also creates a big problem even for the most capable, uncorrupt, and benign bureaucracy. Finally, good problem-solving capability hinges on good communication with citizens and effective scrutiny, elements that are conspicuously missing from the picture of EU governance.

Ⅳ. Voter Competence and Representedness of EU Citizens

The concept of representedness helps to direct our attention from the

citizens are being represented. We can thus refrain from placing blames on either the European or the national level. Concerns over democratic deficit are no longer about whether there is or there isn’t one. The concept of representedness allows us to compare the degree to which interests of citizens are reflected in public policies before and after decision-making power is transferred to the European level. Abandoning the either/or dichotomy, the representedness approach highlights the importance of focusing on the room for improvement in designing institutions and making policies that can better represent citizens.

The previous sections have established that in the absence of conditions mechanisms/conducive to the working of accountability, the degree to which citizen interests are reflected in public policies has decreased due to the reduced possibilities for citizens to hold policy makers accountable once decision-making power is transferred to the European level. Treating the EU as an independent regulator meant to be insulated from voters is equally problematic because, unlike in the domestic context, the superimposed EU is not ensconced in a corresponding society. Yet it is important to note that the loss of representedness may not have been caused entirely by European integration per se: it is quite possible that globalization would have created an even greater hiatus between interests of citizens and policy outcomes had the EU not stepped in. This is not to say that however the current design and practices are they are necessarily the best possible design and practices in reflecting citizen preferences. The subject-centered approach reveals how representedness is lost in the way when the transfer occurs. In this section I focus on the missing links and possible ways to regain the representedness of citizens.

Whether we look at the loss of representedness through the institution design (discussed in section one) or the failure to gain representedness by way of enhancing problem-solving capacity (discussed in section two), voters’ inability to understand and influence policy output seems to be the key. Without sufficient publicity of decision making, even if there are periodical elections, they cannot be seen as an effective retrospective way of rewarding or sanctioning politicians (Strøm, 2000). In addition, publicity of decision making can even change representatives’ policy preferences. Having to be prepared to justify their standpoints publicly renders representatives more committed to beliefs and values that are generally acceptable (Elster, 1998). However, publicity may have this effect only if representatives consider voters competent (Setälä, 2006).

Whenever information, knowledge, publicity of decision making, and voter competence were made an issue in EU governance, scholars unconvinced of the existence of the EU’s democratic deficit would quickly point out that voters are ignorant not just about European affairs: In the domestic context voters have limited

knowledge about the impact of policies on their welfare when casting votes in national and local elections as well (Becker, 1958, 1983; Peltzman, 1976; Stigler, 1975). If voter ignorance is not considered as detrimental to the representedness of citizens at the national level, neither should it be at the European level.

Indeed, in most democracies, citizens’ control over policy makers is at best highly imperfect. When voters have incomplete information, the chains of accountability can never work well enough to induce representation. Accordingly, elections are far from sufficient in insuring that governments would do their best to maximize citizens’ interests (Fearon, 1999; Manin, Bernard, Przeworski, and Susan, 1999b: 44-50). Imperfection in the working of the chains of accountability, however, does not render accountability irrelevant. The fact that chains of accountability become lingering threads when decision-making power is transferred to the EU still has significant implications. Where voters possess only limited substantial information and knowledge about issues and candidates, they tend to follow elite cues and rely on party identification when casting votes. Using heuristics and informational shortcuts is considered both efficient and rational for voters given limited time, energy and ability (Bartels, 1996; Downs 1957: 259; Lupia, 1994, 2001, 2006; Popkin, 1991: 14).That domestic voters have something to refer to when exercising their power of democratic control even in the absence of substantial information and knowledge is crucial information in assessing whether some citizen representedness is being lost when the policy-making power is transferred to the EU. Taking availability of

substantial information and heuristics and informational shortcuts as the key

elements of voter competence, I demonstrate how citizen representedness is reduced when voter competence decreases.

Based on the voter competence view, it is reasonable to assume that if

(1) Accessing substantial information is as—but not more—difficult for citizens in the European context as it is in the national context,

(2) Citizens can compensate for the lack of information and knowledge by following elite cues and party identification in the EU as they can within their own countries,

then handing policy-making power to the EU should have little impact on the representedness of citizens. The reality, however, is that not only is it significantly more difficult for citizens to obtain information regarding policies made by the EU than by their own governments, but using elite cues and party identification as informational shortcuts is also much more difficult at the European level. I will analyze the latter first. To the extent that voters fail to process on their own substantial information on issues and policies, elite cues and party identification become the main factors in determining whether those considered accountable for policy outcomes will

be rewarded or punished by voters. Given the homogeneity of elite views on European integration as reflected in positions of political parties and mainstream media (Parsons, 2007: 1139), not only are voters left with a narrow range of choices at elections, but picking up elite cues and voting according to party identification will also not yield different policy outcomes.

Even if positions on European integration among domestic political parties are sufficiently pluralistic and elite cues can be followed in a meaningful way, the low availability of substantial information still constitutes a problem for voter competence. This is because voters do not rely exclusively on elite cues and party identification at all times. If voters simply cast their votes as were instructed by parties or elites they most identify with, accountability becomes irrelevant. Under such circumstances, whether public policies are made at national or European level would make little difference; as far as voters have elites they trust and parties they identify with, the level of representedness would appear to be maintained regardless of the level in which decision-making takes place. Studies have shown, however, voters do not simply cast their votes as were instructed by the political parties and elites they most identify with without exercising any independent judgments. Rather, parties and elites serve only as a filter for voters to interpret policy implications assess past performance. In other words, while voters’ assessment of the compatibility of a proposition or a candidate is heavily influenced by parties and elite cues, a direct relationship still exists between issues/policies on the one hand and the average, not-very-knowledgeable voters on the other. The more knowledgeable a voter is about issues and policy implications, the more capable she is in assessing the compatibility of a proposition or a candidate with her own preferences (Hobolt, 2009; Harrington, 1993; Popkin, 1991: 14). Information, in other words, can be filtered by elites and parties, but not replaced by them.

Hence, to the extent that voters do exercise independent judgments it matters if information regarding policies and issues is readily available. To the extent voters are taking shortcuts through parties and elites, it matters what it is that parties and elites are filtering for voters. At the national level, whether voters bother to receive and process information regarding policies and issues or not, such information is usually readily available. The same cannot be said about the EU. At the national level, parties and elites filter for voters what is being debated at the domestic political and public policy arena. At the European level, parties and elites still filter for voters what is being debated at the domestic political arena. It is in this sense that accountability is considered to be functioning satisfactorily at the national but not the European level. With reduced voter competence, the representedness of citizens is unlikely to remain at the same level when policy-making is shifted to the European level.

Ⅴ. Conclusion

Is there room for improvement in bringing EU policies closer to citizens’ welfare and interests? The prevalent what is, is right mentality presumes the EU institution design to be good enough and that citizens are being well represented. According to this view, the reduced opportunities for citizens to influence policies are worthwhile given that the necessarily capable regulatory EU state is bound to solve more problems and take better care of citizens. This paper used the concept of representedness to gauge the loss and gain occurred since policy-making power was transferred to the EU. Through the examination of institutional design where a loss of representedness is thought to have occurred, and the problem-solving capability of the EU where a gain of represented is thought to have taken place, I found that while there is overwhelming evidence for the loss of representedness, such loss rarely transforms into increased problem-solving capability as planned. In order to bring citizen representedness back as much as possible to the Pareto front line, a lot more institutional creativity is required to mend the loss of citizen representedness. Given that the reason for the loss and the failure to gain citizen representedness can both be traced to the low voter competence, more attention needs to be paid to voter competence in the future reforms of the EU. If democracy originally meant ‘the capacity to act in order to effect change lay with a public composed of many choice-making individuals,’ or simply ‘the capacity of a public to do things’ (Ober, 2008:5, 12), then ignorance and low voter competence should not be treated as a given, but something the government needs to work on to capacitate the community in order to gain the ‘democratic advantage’ against rivals and competitors.

Notes

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the UACES Exchanging Ideas on Europe

2010—Europe at Crossroads in September 2010 at the College of Europe, Bruges.

1 Such as policing financial markets, controlling the risks of new products and new technologies, protecting the health and economic interests of consumers, reducing environmental pollution, etc. Majone, 1994: 85.

References

Bartels, Larry. (1996). Uninformed Voters: Information Effects in Presidential Elections., American Journal of Political Science, 40 (1): 194-230.

Becker, Gary S. (1958). Competition and Democracy. Journal of Law and Economics, 1: 105-9.

Becker, Gary S. (1983). A Theory of Competition among Pressure Groups for Political Influence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98: 371-400. Bekkers, V., Dijkstra, G., Edwards, A. and Fenger, M. (2007). Governance and the

Democratic Deficit: An Evaluation. In V. Bekkers, G. Dijkstra, A. Edwards and M. Fenger (Ed.), Governance and the Democratic Deficit – Assessing

the Democratic Legitimacy of Governance Practices (pp. 295-312).

Aldershot: Ashgate.

Bekkers, V., Dijkstra, G., Edwards, A. and Fenger, M. (2007). Governance and the

Democratic Deficit – Assessing the Democratic Legitimacy of Governance Practices. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Bevir, Mark. (2010). Democratic Governance. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Dahl, Robert. (1971). Polyarchy—Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Downs, Anthony. (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper-Collins.

Elster, Jon. (1998). Deliberation and Constitution Making. In Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fearon, James D. (1999). Electoral Accountability and the Control of Politicians: Selecting Good Types versus Sanctioning Poor Performance. In Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin (Eds.), Democracy,

Accountability, and Representation (pp. 55-59). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Harrington, Joseph E. (1993). Economic Policy, Economic Performance, and Elections. American Economic Review, 83: 27-42.

Hayek, Friedrich A. (1945). The Use of Knowledge in Society. American Economic

Review, 35: 519-30.

Hilson, C. (2006). EU Citizenship and the Principle of Affectedness. In R. Bellamy, D. Castiglione, and J. Shaw (Eds.), Making European Citizens—Civic Inclusion

in a Transnational Context (pp.56-74). New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Hix, Simon. (1998). Elections, Parties and Institutional Design: A Comparative Perspective on European Union Democracy. West European Politics, 21 (3): 19-52.

Hobolt, Sara. (2009). Europe in Question—Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jolly, M. (2007). The European Union and the People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Katz, Richard, S (2001). Models of Democracy—Elite Attitudes and the Democratic Deficit in the European Union. European Union Politics, 2(1): 53-79. Keohane, R., Macedo, M. and Moravcsik, A. (2009). Democracy-Enhancing

Multilateralism. International Organization, 63(Winter): 1-31.

Kritzinger, S. (2003). The Influence of the Nation-State on Individual Support for the European Union. European Union Politics, 4 (2): 219-241.

Lupia, Arthur (1994). Shortcuts Versus Encyclopedias: Information and Voting Behavior in California Insurance Reform Elections. American Political

Science Review, 88(1): 63-76.

Lupia, Arthur. (2001). Dumber than Chimps? An Assessment of Direct Democracy of Voters. In L.J. Sabato, H.R. Ernst, and B.A. Larson (Eds.), Dangerous

Democracy? The Battle over Ballot Initiatives in America. New York:

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Lupia, Arthur. (2006). How Elitism Undermines the Study of Voter Competence.

Critical Review, 18 (1): 217-32.

McCormick, J. (1999). Understanding the European Union. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press Ltd.

Mair, Peter. (2000). Mair, The Limited Impact of Europe on National Party System.

West European Politics, Vol. 23, no. 4: 27-51.

Majone, Giandomenico. (1994). The Rise of the Regulatory State in Europe. West

European Politics, 17 (3): 77-101.

Majone, Giandomenico. (1996). Regulating Europe. London: Routledge.

Majone, Giandomenico. (1998). Europe’s ‘Democratic Deficit’: The Question of Standards. European Law Journal, 4 (1): 5-28.

Majone, Giandomenico. (1999). The Regulatory State and its Legitimacy Problems.

West European Politics, 22 (1): 1-24.

Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski, and Susan C. Stokes. (1999a). Introduction. In Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin (Eds.), Democracy,

Accountability, and Representation (pp.1-26). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski, and Susan C. Stokes. (1999b). Elections and Representation. In Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin (Eds.), Democracy, Accountability, and Representation (pp. 27-54).

Marsh, Michael. (1998). Testing the Second-Order Election Model after Four European Elections. British Journal of Political Science, 28: 591-607. Moravcsik, Andrew. (1998). Europe’s Integration at Century’s End. In Andrew

Moravcsik (Ed.), Centralization or Fragmentation? Europe Facing the

Challenges of Deepening, Diversity, and Democracy (pp.1-58). New York:

Council on Foreign Relations.

Moravcsik, Andrew. (1998). Centralization or Fragmentation? Europe Facing the

Challenges of Deepening, Diversity, and Democracy. New York: Council on

Foreign Relations.

Moravcsik, Andrew. (2000). Democracy and Constitutionalism in the European Union.

ECSA Review, 13: 2.

Moravcsik, Andrew. (2002). In Defence of the Democratic Deficit: Reassessing Legitimacy in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 40 (4): 603-24.

Ober, Josiah. (2008). Democracy and Knowledge—Innovation and Learning in

Classical Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Papadopoulos, Yannis. (2005). Implementing (and Radicalizing) Art. I-47.4 of the Constitution: Is the Addition of Some (Semi-)Direct Democracy to the Nascent Consociational European Federation Just Swiss Folklore?. Journal

of European Public Policy, 12 (3): 448-467.

Parsons, Craig. (2007). Puzzling out the EU role in national politics. Journal of

European Public Policy, 14(7): 1139.

Peltzman, Sam. (1976). Toward a More General Theory of Regulation. Journal of

Law and Economics, 19: 209-87.

Pitkin, H.F. (1967). The concept of representation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Popkin, Samuel L. (1991). The Reasoning Voter: Communication and Persuasion in

Presidential Campaigns. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Przeworski, Adam, Bernard Manin, and Susan C. Stokes. (eds.) (1999). Democracy,

Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Reif, Karlheinz and Hermann Schmitt. (1980). Nine Second-Order National Elections: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results.

European Journal of Political Research, 8: 18-36.

Sartori, Giovanni. (1987). The Theory of Democracy Revisited. London: Chatham House.

Setälä, M. (2006). On the problems of responsibility and accountability in referendums. European Journal of Political Research, 45: 699–721.

Stigler, George J. (1975). The Citizen and the State: Essays on Regulation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Strøm, K. (2000). Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies.

European Journal of Political Research, 37: 261–289.

Thorlakson, Lori. (2005). Federalism and the European Party System. Journal of

European Public Policy, 12 (3): 468-487.

Tsebelis, G. (2008). Thinking About the Recent Past and the Future of the EU. Journal

of Common Market Studies, 46(2): 265-292.

Tsebelis, G. and Yataganas, X. (2002). Veto Players and Decision-Making in the EU after Nice: Policy Stability and Bureaucratic/Judicial Discretion. JCMS, Vol. 40, No. 2: 283–307.

Ward, D. (2004). The European Union Democratic Deficit and the Public Sphere – An

Evaluation of EU Media Policy. Oxford: IOS Press.

Weiler, J. H. H. and Joseph H. H. (1991). The Transformation of Europe. Yale Law

The Representedness of EU Citizens Analyzed through

Institution Design, Problem-Solving Capacity, and Voter

Competence

從歐盟制度設計、問題解決能力以及選民能力剖析歐盟公民之被代表性 Chien-Yi Lu

Associate Research Fellow

Institute of International Relations, National Chengchi University No. 64, Wan Shou Rd., Wen Shan District, 11666, Taipei, Taiwan

Telephone: (02) 8237-7369 e-mail: cyl@nccu.edu.tw 盧倩儀 副研究員 國立政治大學國際關係研究中心 11666 台北市文山區萬壽路 64 號 Telephone: (02) 8237-7369 e-mail: cyl@nccu.edu.tw

The Representedness of EU Citizens Analyzed through

Institution Design, Problem-Solving Capacity, and Voter

Competence

Abstract

To what extent do EU policies reflect the interests of European citizens? Is the policy-making process of the EU, according to its design, equipped with the capacity to well represent the citizens? This article adopts a subject-centered—as opposed to the traditional container-centered—approach and uses the concept of representedness to find answers for these questions. The conventional wisdom suggests that even though citizens lose some representedness under the design of the EU institutions, owing to the enhanced problem-solving capacity of the EU, the overall representedness of the European citizens remains the same. In this article I demonstrate that given the absence of conditions required to transform the loss of representedness into enhanced problem-solving capability, there is a severe net loss of citizen representedness in the EU. In order to bring citizen representedness back as much as possible to the Pareto front line, a lot more institutional creativity is required to mend the loss of citizen representedness. Given that low voter competence plays a crucial role in both the loss of and the failure to gain citizen representedness, future reforms of the EU need to pay close attention to the issue of voter competence.

Key Words: European Union, representedness, accountability, problem-solving capacity, voter competence