科學的卡萊爾:《衣服哲學》中的科學、物質、與科學家 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Chang 2. The Scientific Carlyle: Science, Matter, and Scientists in Sartor Resartus. A Dissertation Presented to Department of English,. 政 治 大. National Chengchi University. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. i. i Un. v. e nFulfillment gch In Partial of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Heui-tsz Chang January 2010.

(3) Chang 3. To Orlando, Yuni, and Hilda. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(4) Chang 4. Acknowledgements To write a dissertation is a lonely and isolating experience. It is impossible to accomplish this dissertation personally without the support of numerous people. My sincere gratitude thus goes to my advisor, my committee members, my parents, my friends, and my family. In the first place, I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Chao-ming Chen, who has the attitude and substance of genius in both research and teaching. His truly literary intuition has always made him an oasis of ideas to. 政 治 大 encouragement, supervision, and support from the preliminary to the concluding 立 inspire me and to enrich my study whenever I was lost in thoughts. Without his. ‧ 國. 學. levels, this dissertation would not have been possible.. I gratefully acknowledge my committee members, Dr. Han-ping Chiu, Dr.. ‧. Ying-huei Chen, Dr. Chien-chi Liu, and Dr. Eva Y.I. Chen, for their reading of my. Nat. sit. y. manuscript and for their insightful guidance and helpful advice. They are always the. n. al. er. io. model of literary scholars. My gratitude is also extended to the teachers who taught. i Un. v. me at National Chengchi University, including Dr. Yuan-wen Chi of Academia Sinica.. Ch. engchi. Their insightful instructions were the soil to nurture the growth of this dissertation. I would also like to thank my parents, my sister and my brother. They were always supportive, encouraging me with their best wishes. I am indebted to my friends too, without whose encouragement and support this dissertation would never be finished. Last but not least, I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to my husband, Orlando. His support, encouragement, and unwavering love were the foundation on which our family has been built in the past eight years. To him, our son, Yuni, and our daughter, Hilda, I dedicate this dissertation..

(5) Chang 5. The Scientific Carlyle: Science, Matter, and Scientists in Sartor Resartus. The Table of Contents: Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………..…….iv English Abstract………………………………………………………........................ix Chinese Abstract……………………………………………………………….…….xii Introduction: Science vs. Religion…………………….……..…………………….. 1 I. The Huxley-Wilberforce Encounter in 1860…………………….2` II. Emery Neff’s Study of Thomas Carlyle and John Mill………….5 III. Carlyle in M. A. Abrams’s Natural Supernaturalism……………6 IV. Some Inquiries about the Studies concerning Carlyle and Sartor Resartus……………………………………………………….....7. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Chapter One: Carlyle, a Victorian Sage? ..............................................…………..16 I. Introduction……………………………………………………..16 II. The Modern Interpretations of Carlyle and Sartor Resartus and Their Problems………………………………………………….21 (1) The New Criticism…………………………………………….21 (2) Cultural Criticism……………………………………………...29 III. Problems of Carlyle the Author-God and Theories about the Author…………………………………………………………..34 IV. Problems of the Aesthetic Unity and Foucault’s Archaeological Study…………………………………………………………….40. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Chapter Two: The “Torch of Science”……………………………………………..48 I. Introduction……………………………………………………..48 II. The Twentieth-First Century Complex Thesis of Science-Religion Relation…………………………………………………………51 III. The Torch of Science in Sartor Resartus……………………….61 (1) Carlyle’s “Torch of Science”…………………………………61 (2) Carlyle’s “Torch of Science” and Religion…………………..72 (3) The General Contamination of the Mechanical in the Use of Science and Carlyle’s Urge of Reform………………………...82 IV. The Torch of Science……….…………………………………...93.

(6) Chang 6. Chapter Three: Natural Supernatural Redefined……………………………….. 96 I. Introduction……………………………………………………..96 II. Carlyle’s Early Studies and Natural Theology………………...101 (1) Carlyle’s Early studies...…………………………………….101 (2) Matter in Natural Philosophy……………………………….104 III. Matter in Sartor Resartus……………………………….……..112 (1) Natural Theology and Matter ...…………………………….112 (2) Matter and Spirit, Nature and the Supernatural, Visible and the Invisible……………………………………………………..117 (3) The Break between the Subjective and the Objective Universes……………………………………………………122 (4) Carlyle’s Contemporary Social Disease in All Fields………127 (5) Fantasy……………………………………………………...132 (6) Whole……………………………………………………….135 (7) Teufelsdrockh, the Emblem of the Whole…………………..138 IV. “Natural Supernaturalism”…………………………………….140. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Chapter Four: Teufelsdrockh, More Than a Literary Man…………………….143 I. What Is Carlyle’s “Tailor”?........................................................143 II. Carlyle and Science: Science and the Man of Science in the Early Nineteenth Century……………………………………………147 III. More Than a Literary Man…: Teufelsdrockh and Science……156 (1) The Whewellian Scientist and the Carlylean Scientist….…..156 (2) Teufelsdrockh as a Scientific Great Mind of the Newtonian School……………………………………………………….169 a. “When the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch.”.……………………………………………………..169 b. “The whole is greater than the part.”….…………………...173 c. “[T]he whole world of Speculation might henceforth dig to unknown depths.”………………………………………….177 d. “Call one Diogenes Teufelsdrockh, and he will open the Philosophy of Clothes.”……………………………………182 e. “[T]he Tailor is Not only a Man, but something of a Creator or Divinity.”..…………………………………………………186. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Coda: From the Sagistic Carlyle to the Scientific Carlyle………………………192.

(7) Chang 7. Works Cited………………………………………………………………………..201. Abbreviations: Sartor Resartus “Signs of the Times” “Characteristics”. SR ST CH. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

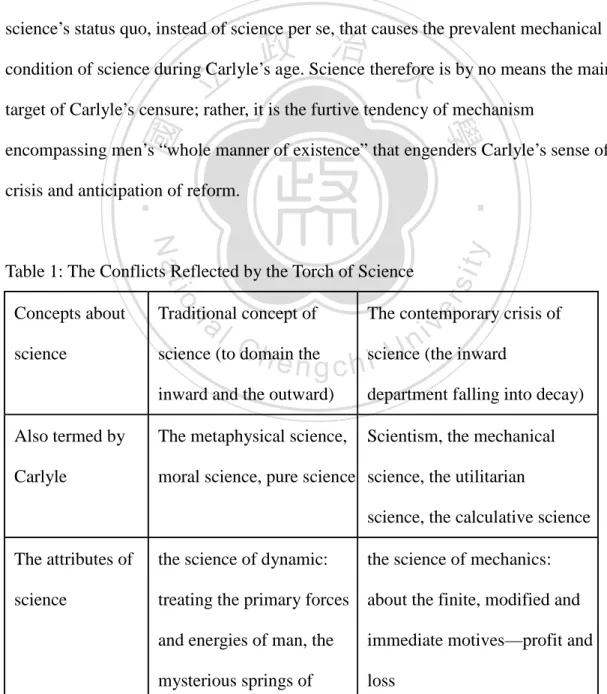

(8) Chang 8. The Scientific Carlyle: Science, Matter, and Scientists in Sartor Resartus. English Abstract There are two purposes of this study. First, to dispel the myth that regards Thomas Carlyle as a sage or prophet and Sartor as an aesthetic unity, and, second, to debunk the myth that assumes a conflict between science and religion, matter and spirit, as well as between philosophers and scientists in Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus.. 政 治 大 and matter, and Sartor was regarded as an aesthetic unity to transmit the Carlylean 立. Carlyle was traditionally supposed to be a “sage-prophet” who rejects science. ‧ 國. 學. philosophy of religion and spirit. The two myths have been consolidated in many social, cultural, and literary studies and need reexamination.. ‧. This dissertation comprises four chapters. The first chapter deals with the. Nat. sit. y. demystification of Carlyle as an “Author-God” to generate new meanings and create a. n. al. er. io. new genre. It also questions Sartor as an “aesthetic unity” to reflect the author’s. i Un. v. sagacity and to stand for a modern bible. To be interpreted through Michael. Ch. engchi. Foucault’s archaeological study, Sartor will be demonstrated as a discursive museum to exhibit the transitions and vicissitudes of thoughts in reference to science, matter, and scientists. Chapter Two treats the religious significance of Carlyle’s “Torch of Science.” Through the theory of a mutually productive relationship between science and religion, this chapter will reveal the sacredness in the “Torch of Science.” Not a destroyer of faith, the “Torch of Science” serves as a religious vehicle to explore the exterior/material world and the interior/spiritual universe. Instead of criticizing the “Torch,” Carlyle encourages the proper use of science and expects spiritual reform.

(9) Chang 9. from the “Torch.” The main target of Carlyle’s prod thus is not the “Torch of Science” per se but its status quo, i.e., the abuse of science dominated by utilitarianism and mechanism. In Chapter Three, based on his contemporary natural theology, the philosophy of “Natural Supernaturalism” will be analyzed as Carlyle’s belief in the mutually productive interrelations between spirit and matter as well as the visible and invisible. Never thinking matter as “litter,” Carlyle deems the spiritual and the material as two sides of wholeness, corresponding to and supporting each other. Never questioning man’s use of matter, Carlyle advises his reader to open their inner eye with faith, to. 治 政 penetrate the material form with fantasy, and to see God’s 大truth in the “whole.” 立 In Chapter Four, with the references to Carlyle’s personal experiences, “science” ‧ 國. 學. as a vocation in the 1820s and 1830s, and the philosophy of science and the scientist. ‧. advocated by William Whewell, “Diogenes Teufelsdrockh” will be reanalyzed and. sit. y. Nat. reinterpreted as an ideal proto-scientist wandering and pondering solitarily in the dark.. io. al. er. Moral, spiritual, religious, and philosophical, the scientific thinker purports to defeat the furtive invasions of mechanism and utilitarianism. Not simply “God-born Devil’s. n. iv n C dung,” “Diogenes Teufelsdrockh” encapsulates gist of Carlyle’s clothes h e n g c the hi U. philosophy: a wise speculative scientist searching for the truth of God hidden in every corner of the natural world. Instead of criticizing science and matter, Carlyle in fact laments that man no longer trusts the invisible and the interior but has all his head, heart, and hand contaminated by mechanism and utilitarianism. For spiritual and moral reform, Carlyle places his hope on the scientist holding a Torch. Through the intertextual reading of Sartor, this study shows the interplay, conflict, conciliation, and evolution of the thoughts in reference to Carlyle’s contemporary concepts of science and religion, matter and spirit, as well as scientists and philosophers..

(10) Chang 10. 科學的卡萊爾: 《衣服哲學 科學的卡萊爾: 《衣服哲學》 衣服哲學》中的科學、 中的科學、物質、 物質、與科學家 中文摘要. 本研究有兩目的:第一,打破卡萊爾為智者預言家,與《衣服哲學》為美學 整體之迷思;第二,重探卡萊爾在《衣服哲學》中呈現科學∕宗教與物質∕精神 二元對立之迷思。 在傳統的研究中,卡萊爾一向代表智者預言家,反對科學與物質;而《衣服 哲學》則代表美學整體,忠實地傳達卡萊爾的宗教與精神哲學。然而在過去的研. 治 政 究中,有兩個迷思逐漸固化,而需再次檢驗。首先,卡萊爾為預言哲學家之說誤 大 立 將卡萊爾視為超越主義之起源,而美學整體之說則誤認《衣服哲學》為一完整美 ‧ 國. 學. 學領域,內涵特定中心與主旨。其次,過去學者一致認同的科學∕宗教與物質∕. ‧. 精神二元敵對之說,也令人質疑,因為根據在二十一世紀初之科學宗教歷史的新. sit. y. Nat. 研究,直至十九世紀末,包括卡萊爾在創作其《衣服哲學》期間(1830-31) ,科. io. er. 學與宗教之間並非互有惡意的敵對關係,而是複雜而互惠的交互關係。 本論文包括四個章節,第一章旨在重探卡萊爾具有「作者神格」及《衣服哲. al. n. iv n C 學》內含美學整體之說,試圖破除卡萊爾為意義與文類創造者之迷思,以及質疑 hengchi U. 《衣服哲學》能忠實呈現其「作者父親」之智慧賢能,並代表現代聖經之假說。 以傅科之考古的歷史學研究為基礎,本研究將呈現《衣服哲學》為一論述博物館, 陳列英國於 1820 與 1830 年間,關於科學物質方面的思想,並探討交錯於此觀念 下各類論述的演變、交錯、與興衰。 第二章則探討卡萊爾在「科學火炬」中所內涵的宗教意義。透過二十一世紀 科學宗教歷史的新研究,以科學宗教的互為生產關係為基礎,本研究發現科學之 於卡萊爾並非宗教信仰之破壞者,反而是服務宗教的神聖工具,其「火炬」功能, 不僅能挖掘外在的物質世界,也能深掘內在的精神宇宙。《衣服哲學》於是並非 旨於批判「科學火炬」,而在宣揚其教化功能,宣導科學的善用,並期以科學之.

(11) Chang 11. 火達到復興心靈及內在改革之目的。卡萊爾的真正批判標的,於是並非「科學火 炬」本身,而是「科學火炬」的所處之境,也就是,世人的心靈因受實用主義與 機械主義的支配,而造成對科學火炬之誤用。 根據卡萊爾同時期的自然神學,以精神∕物質及可見∕不可見之間互為生產 的相互關係為基礎,第三章旨於重新檢驗卡萊爾的「自然超自然主義」。物質之 於卡萊爾,實非無用而該摒棄之物,而是開啟精神之門的必要之鑰,因為精神與 物質實為神的一體兩面,互惠與相互對應。實體之物,與無形之精神則同等重要。 卡萊爾於是從未呼籲停用物質,拋棄衣物,他實則建議讀者應當張開其內心之 眼,穿越物質之限制,真實看達上帝之真理。由外至裡,由實體至無形,此認知,. 治 政 才是真正對於神的「一體兩面」的完整認識。 大 立 第四章,根據卡萊爾的個人經驗、1820 與 1830 年間科學家一職的發展、以 ‧ 國. 學. 及威維爾的科學與科學家哲學,本研究將重新定義戴歐吉尼斯‧托服思卓空為一. ‧. 早期理想科學家的原型,也就是孤獨地在黑暗中流浪與沈思的智者。此科學之智. sit. y. Nat. 者一方面道德與精神崇高,一方面又篤信哲學與宗教;他對於科學的致力研究,. io. er. 旨在對抗機械主義與實用主義對當代文化精神的鯨吞蠶食。「戴歐吉尼斯‧托服 思卓空」之名,於是不應簡單地只代表著「生於上帝之魔鬼污糞」。透過對於當. al. n. iv n C 代的理想科學家形象之探討,此名所深含之隱喻於是展現:上帝之真理,深藏於 hengchi U 自然物質世界之所有情境,甚至是任何不起眼之角落;只有透過沈思的智者科學 家,深悟其宗教的使命,才有辦法開啟上帝之真理。 卡萊爾於《衣服哲學》中以嘲諷口吻所批評之對象,並非科學與物質,而是 卡萊爾對世人的失望,因為世人不再相信看不見的內在精神事物,反而任由其 腦、心、與手受控於機械主義與實用主義。卡萊爾於是期待改革,期許沈思的科 學哲人手持神聖的科學火炬,引領世人進行改革,復興傳統的信仰、道德、與精 神。透過文本與社會文化的互文閱讀,本論文於是呈現,收藏在《衣服哲學》論 述博物館之內,關於宗教∕科學、精神∕物質、與哲學人∕科學人等思想之交會、. 矛盾、相融、及衍生。.

(12) Chang 12. Introduction Science vs. Religion. “Never mind whether religion and science were really in conflict; they were increasingly thought to be in conflict.” (Welch 34). “To change the image radically, what we have in the nineteenth century, from Schleiermarcher and Hegel on, is both a massive effort at mediation or synthesis, a uniting of theology and science.” (Welch 37). 政 治 大 During the twentieth century, it was widely believed among the popular as well 立. ‧ 國. 學. as the intellectual that there had been always warfare relationships between science and religion since the sixteenth century. The contentions triggered by the scientists. ‧. such as Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543), Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), Galieo. Nat. sit. y. Galilei (1564-1642), and Charles Darwin (1809-1882) were the typical examples to. n. al. er. io. support the conflict theory. The Copernicus’s astronomical revolution (1514), namely. i Un. v. the heliocentric (sun-centered) theory, was extensively believed to be the initiation of. Ch. engchi. the war between science and religion in history. After three-century struggles finally, for the warfare-theory believers, the scientific revolution at last reached its eventual victory and overcame religious authority in 1859, the year when Darwin published his Origin of Species. Due to the ideology of the warfare relation between science and religion, some thoughts were believed always oppositional to each other. Deeply rooted in the twentieth-century minds, the concept of “science” implied the physical world, matter, reason, and truth, while that of “religion” referred to the invisible world, spirit, irrationality, and superstition. With these allusions, a scientist was supposedly a.

(13) Chang 13. rationalist and enlightened thinker, who embraced the faith of “to see is to believe.” To the contrary, a religious man was usually assumed intuitional and superstitious, not able to judge by reason but by instinct. To state more plainly, among the twentieth-century minds, concepts of science and the scientist signified cleverness and rationality while those of religion and the religionist denoted ignorance and muddlehead. The famous incident of the 1860 encounter between Bishop Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Henry Huxley is one of the most persuasive examples to portray the idée fixes of a scientist and a religionist. This dramatic incident not only indicates the victories of science and reason over religion and superstition but also. 治 政 marks the ultimate break of science from religion and the 大scientist from the yoke of 立 the Church. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. I. The Huxley-Wilberforce Encounter in 1860. sit. y. Nat. During the warring quarrels over Darwinism in the mid nineteenth century, a. io. al. er. representative science-religion warfare opened fire between Wilberforce the Bishop and Huxley the scientist at a meeting of the British Association in Oxford on June 30,. n. iv n C 1860. Soon after Darwin’s publication of Species (1859), Wilberforce and h eofnOrigin gchi U. Huxley debated on the issue of evolutionism: Wilberforce poured scorn on Darwin’s evolution theory, while Huxley, the mouthpiece of the autonomy of science, bearded Wilberforce and defeated the “prelatical insolence and clerical obscurantism” (Lucas 1996). Since this dramatic event, Wilberforce then was illustrated as an emblem of the stubborn, banal, and irrational Church, and Huxley was as that of the clever, vital, and reasonable science. Not merely popular in the late nineteenth century, this historical event of the Wilberforce-Huxley encounter was prevalent during the early and mid.

(14) Chang 14. twentieth century as well.1 William Irvine, for instance, once adopted this dramatic encounter to caricature the ignorant and muddleheaded bishop and to glorify the intelligent and rational scientist in his 1955 book, Apes, Angels and Victorians: The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution. Even if popular, the 1860 Huxley-Wilberforce encounter however should not be considered a reality. In “Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter,” J. R. Lucas states that even if “[t]he legend of the encounter between Wilberforce and Huxley is well established,” the account yet “must be a largely legendary creation of a later date” (1996). In Darwin’s Forgotten Defenders: the Encounter between. 治 政 Evangelical Theology and Evolutionary Though, D. N.大 Livingstone also argues that 立 the 1860 encounter should be more fictional than actual (Livingstone 33-35) because ‧ 國. 學. there was never the first-hand reference recording the contents of the belligerent. ‧. repartee between the two representative men.2. sit. y. Nat. The two studies above share a common ground: the “history” of the 1860. io. al. er. religion-science encounter should be a legend, not a reality; it is more of a fiction fabricated by the later-day intellectuals. Lucas opines that this encounter is of. n. iv n C significance because it denotes the h divergence of disciplines. e n g c h i U Before 1860, “a largely amateur and unprofessional public” could easily get on science (Lucas 1996). However, after 1860, science gradually became “more of a closed shop…from which amateurs [were] more and more excluded” (Lucas 1996). For Locus, the importance 1. According to Colin Gauld’s research, “References to the Wilberforce-Huxley encounter were found in 63 books. The earliest report was dated 1896 (republished in 1960) while the latest was 1991.” In Gauld’s research, it shows that among the 63 references about the meeting, the major emphasis of the encounter is not the substance of the speeches of the two significant men but the impressions of the two: the ignorant and conservative Wilberforce defeating the clever and rational Huxley. Cauld intends to prove from the references that, Wilberforce-Huxley encounter, whether a reality or not, is of powerful influence to strengthen the impression of a warfare relation between science and religion with the circulation of scientific knowledge (Gauld 2007). 2 J. R. Lucas. “Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter” (http://users.ox.ac.uk/~jrlucas/legend.html) Originally published in The Historical Journal, 22, 2 (1979), pp. 313-330, This page was revised on May 31st, 1996, and most recently revised on August 17th, 2008. 2008 08 23. D. N. Livingstone. Darwin’s Forgotten Defenders: The Encounter Between Evangelical Theology and Evolutionary Thought. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987..

(15) Chang 15. of the encounter consists not in proving the conflict between two systems of thoughts but in signifying a cultural phenomenon; that is, during the end of the nineteenth century, science was no longer a study tolerating the participation of any unprofessional man, such as Wilberforce the Bishop. Around the 1860s, science should have already turned to be a “specialty in which non-professionals [were] disfranchised from the right to express an opinion” (Lucas 1996). Livingstone brings up a similar opinion in his study as well, pointing out that the 1860 encounter might be an imagined legend popularly existing among the intellectuals of the 1890s. Similar to Lucas, Livingstone considers that, at the end of. 治 政 the nineteenth century, there was a rise of new scientists 大who intended to distinguish 立 themselves from the influence of the Church and to strike out a new field of their own. ‧ 國. 學. Livingstone analyzes further that, inasmuch as scientists’ consciousness of a. ‧. necessary separation from the influence of the Church appeared in the 1890s, there. sit. y. Nat. would not have been vehement hostility between the bishop and the scientist during. io. al. er. the 1860s, the age of Darwin’s Origin being published. If the concept of warfare between science and religion was not yet concretized during the 1860s, among the. n. iv n C amateurs or laymen in the years while Carlyle composed Sartor Resartus h eThomas ngchi U. (1830-31), there should not have been thoughts of religious and scientific animosities against each other. Carlyle’s criticism thus should not be targeted at science per se. Supposedly there might have been a more precise object that Carlyle intended to attack. Though seeming not a reality, the imagination of a combative relation between science and religion in the past centuries was popularly circulated in every field of the studies in the twentieth century. Many disciplines in the academic studies had the concept of a warfare theory rooted. In the literary field, too, the ideology of a science-religion war, whether in an implicit or explicit way, dominated scholars’.

(16) Chang 16. analyses in the twentieth century. In the analyses of the early nineteenth-century writer like Carlyle, hostilities between science and religion as well as matter and spirit were usually supposed truths and hardly questioned.. II. Emery Neff’s Study of Thomas Carlyle and John Mill In the last chapter of Carlyle and Mill (1926), “Old Foes with New Faces,” Neff concludes the three-hundred-page study with a deep regret: “Who knows how much more the cooperation of Carlyle and Mill, the intellectual leaders of the mid-century, might have accomplished?” (393) Once friends and admirers of each other, Carlyle. 治 政 and John Stuart Mill broke their friendship and became大 foes possessing opposite 立 ambitions and styles. Neff considers that, due to “the incompatibility of their ‧ 國. 學. temperaments,” the “design of cooperation” between the two representatives of the. ‧. Victorian society became “fatal” (393). “Carlyle” and “Mill,” in Neff’s study, hence. sit. y. Nat. stand for two models of the recurrent battles between duel intellectuals: “the. io. al. er. contrasting types like Mill and Carlyle, scientists and artists, positivists and transcendentalists, individualists and authoritarians, constantly recur in the world”. n. iv n C (393-94). Their ideas, beliefs, values, and methodologies to knowledge are h ethoughts, ngchi U so diverse that “[i]t is probable that their division will be eternal, or at least until the success of Carlyle’s jestingly imagined ‘Heaven and Hell Amalgamation Society’” (396). According to his own words, Neff determines that there is no possibility of any mutual interrelation between not only Carlyle and Mill but also the values they represent—science and art, positivism and transcendentalism, as well as reason and religion. Titling his book Carlyle and Mill: an Introduction to Victorian Thought, Neff apparently indicates that Carlyle and Mill are two symbolic figures to represent two streams of ideas in the Victorian society. In the Neffian analysis, Carlyle is influenced.

(17) Chang 17. by German idealists while Mill by French Positivists; Carlyle is religious as well as spiritual while Mill scientific as well as materialistic. Within the two streams of thoughts, suggested by the metaphor of “Heaven and Hell,” dwells bare interrelation but an unbridgeable gulf. Metaphorically, then, Neff asserts an ever confronting force of science in contrast to religion, matter to spirit, as well as a scientist to a religious philosopher. This assumption obviously takes for granted the binaries of science/religion, matter/spirit, and scientist/philosopher in Carlyle’s age. Though first printed in 1926, Neff’s Carlyle and Mill was still influential in the mid-twentieth century and had its reprints in 1952, 1964, and 1974. The success of the. 治 政 Neffian study indicated that the assumptions of the breaks 大 between science-religion, 立 matter-spirit, and scientists-philosophers in the early nineteenth century were ‧ 國. 學. undoubtedly realities and generally agreed among scholars. In the twentieth-century. ‧. researches, Carlyle unquestionably stood for the “philosopher” of “religion” and. io. al. er. contrast with the “scientist” of “science” and “matter.”. sit. y. Nat. “spirit”—the keywords that could be synthesized by the term, transcendentalism—in. n. iv n C III. Carlyle in M.A. Natural Supernaturalism h eAbrams’s ngchi U Not merely belonging to the camp of religion in Neffian dualism, Carlyle also represents an artist to inherit the theological tradition of Christianity in M.A. Abrams’s Natural Supernaturalism (1971). By applying Carlyle’s term in Sartor Resartus, Abrams titles his remarkable study on Romanticism as Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature. With Carlyle’s paradoxical phrase, Abrams analyzes the common significance among Romantic poets and philosophers in both England and Germany. “Natural Supernaturalism” henceforth signifies a specific terminology to demonstrate the Romantic spirit—“to naturalize the supernatural and to humanize the divine” (68)—and to link the.

(18) Chang 18. revolutionary spirit of Romanticism with the Christian tradition in literature. To categorize Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus in the trend of Romanticism, Abrams supposes that Carlyle’s protagonist, as other Romanticists do, undergoes a similar “self-formative educational journey” (Abrams 309). Like the Romantic poets, Teufelsdrockh wanders in the wild nature, “the solitude of the North Cape” (SR 135), to seek spiritual healings. Troubled by the spiritual crisis in a sense of insecurity between the outward chaos and the inner desire, the Romantic pilgrim journeys to quest possible reconciliations between the exterior disorder and interior harmony. In such interpretation, Teufelsdrockh’s biography culminates at the moment of “The. 治 政 Everlasting Yea,” in which, religiously, he perceives an大 ultimate omnipotent power 立 that governs the order and harmony of the entire universe. ‧ 國. 學. Purposefully, Abrams aims to apply Carlyle’s “natural supernaturalism” to. ‧. interpreting Romantic poets’ secularized theology—Romantics unconsciously inherit. sit. y. Nat. the theological tradition of Christianity and transfer the religious concepts, images,. io. al. er. and patterns to the secularized form in nature. Interpreted in this way, Carlyle’s “The Everlasting Yea” is conceived as “a secularized form of devotional experience”. n. iv n C (Abrams 65). To align religion withhRomanticism, Abrams e n g c h i U is contributive to revealing the “assimilation of Biblical and theological elements to secular or pagan frames of reference” (66) in Romantic poets. He argues that though considered hostile to Christian religion, the Romanticists could never escape the “religious formulas” that had been “woven into the fabric of our language” (66). In his analysis, “natural supernaturalism” hence represents a cardinal term to manifest the unbreakable Christian tie woven in the works of Romanticists as well as of Carlyle.. IV. Some Inquiries about the Studies of Carlyle and Sartor Resartus Due to the science-religion conflict assumption (in Neff’s study for instance) as.

(19) Chang 19. well as the unbreakable Christian tie woven in Carlyle’s work (such as in Abrams’), the twentieth-century studies about Sartor Resartus usually explicitly or implicitly related the issue of transcendentalism to the work’s unbreakable bond to Christianity.3 Due to the work’s umbilical cord linking religion and religion’s hostile relation to science, the famous “Torch of Science” (SR 1) in the opening of Sartor thence turned to be a target of Carlyle’s criticism. For instance, the “‘Torch of Science’ expels Mystery and reduces Creation to a material process,” comments Tess Cosslett in The ‘Scientific Movement’ and Victorian Literature (1982: 1). In her analysis, Cosslett assumes that “science” is synonymous with rationalism and materialism. The. 治 政 mechanistic powers of reason and matter efface the intrinsic 大 force originating from 立 intuition and soul. The “Torch of Science” hence murders the Mystery of the Creation ‧ 國. 學. Myth in Christianity. Tantamount to a religious declaration, Sartor Resartus in. ‧. Cosslett’s analysis therefore aims to go for science, reason, matter, and mechanism.. sit. y. Nat. Instead of an exception, Cosslett’s assumption was generally the agreement hinted or. io. al. er. declared in the twentieth-century studies—Carlyle the transcendental philosopher. n. should be of a Christian origin, devoting himself to criticizing science, matter, as well as the scientist.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. However, as investigated by Lucas and Livingstone, if in reality there was neither apparent break nor vehement hostility but merely a fabrication of conflicts 3. The issues of transcendentalism or religion can be discovered in the studies as follows: “Transcendence through Incongruity: the Background of Humor in Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus.” (Abigail Burnham Bloom. The Victorian Comic Spirit: New Perspectives. Ed. Jennifer Wagner-Lawlor. Aldershot, England: Ashgate: 2000. PP153-72.) Bloom’s article is about Carlyle’s usage of irony to reveal his idea of transcendentalism. “Coleridge in Sartor Resartus.” (James Treadwell. Wordsworth Circle. 1998 Winter; 29(1): 68-71). This essay is about Carlyle’s transcendentalism in relation to Coleridge’s Romantic thought. “Sartor Resartus: A Philosophy of a Mystic.” (Yukihito Hijiya. The Carlyle Society Papers-Session 1991-92. Edinburgh: Carlyle Soc..; 1992. PP41-50). Hijiya’s article is on Carlyle’s Romantic spirit, about the pilgrim’s self consciousness and inner life. “‘Shadow-Hunting’: Romantic Irony, Sartor Resartus, and Romanticism.” (Janice L. Haney. Studies in Romanticism. 1978; 17:307-33). “Adam-Kadmon, Nifl, Muspel, and the Biblical Symbolism of Sartor Resartus. (Joseph Sigman. ELH 1974Summer; 41 (2): 233-56). “The Pattern of Conversion in Sartor Resartus.” (Walter L. Reed. ELH1971 Sept; 38(3): 411-31.) And “Sartor Resartus and the Problem of Carlyle’s ‘Conversion.’” (Carlisle Moore. PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 1955 Sept; 70(4): 662-81..

(20) Chang 20. between science and religion in the early nineteenth century, did Carlyle assuredly intend to design a story that simply targets science? If Carlyle indeed aimed to criticize science per se, why did he state definitely that he could not find any solution in either English or French philosophies but have to turn to the “scientific watch-tower” (SR 2) of the German to look for the key to straighten out his contemporary spiritual crisis? Or, if Carlyle indeed deemed that the modern science in his age was guilty of spoiling his contemporaries’ spiritual progress, why did he declare his belief of an integration of man and nature as well as being and nothingness by stating, “This [the integration] is no metaphor, it is a simple scientific fact” (199)?. 治 政 Furthermore, if science was unquestionably in opposition 大to spirit and religion during 立 his age, entirely synonymous to mechanism and materialism, why did Carlyle praise ‧ 國. 學. Teufelsdrockh’s philosophy in one of the concluding chapters of Sartor with the. sit. y. Nat. of thy part yield richer fruit” (203).. ‧. phrase, “this [Science of Clothes] is a high one, and may with infinitely deeper study. io. al. er. According to the evident passages found in Carlyle’s own work, I opine that what Carlyle intended to criticize should not be the “Torch of Science” itself.. n. iv n C Provided that Carlyle took his philosophy as a “science” and considered the h e nofgclothes chi U philosophy to integrate the microcosm with macrocosm as a “scientific fact,” the conception of “science” in Sartor should stand for a more positive and prominent meaning. The tendencies to take the “Torch of Science” as a negative term and as Carlyle’s object of ridicule might probably be correspondent to the twentieth-century assumption of the science-religion struggle in the past centuries. The binary opposition of science and religion thus severed Carlyle the Christian philosopher from the “Torch of Science,” simultaneously tagging religion with spirit and science with matter. The past analogy of religion with spirit and science with matter, gradually, caused the word “science” in Sartor an ambiguous term and made the reading of.

(21) Chang 21. Sartor a torturous journey. The warfare assumption in fact hardly helped understand the difficult work but incidentally created more obstacles to entangle the reader in the whirlpool of Carlyle’s thoughts. Therefore, what if there was not warfare relation between science and religion, matter and spirit, as well as scientists and philosophers/religionists during Carlyle’s early age? What if in reality Carlyle did not directly aim at attacking “science” in Sartor but others? And what if during Carlyle’s age there was positive correspondence than hostile belligerence between science and religion? To get rid of the haunting assumption of the warfare theory, I then intend to examine Carlyle’s Sartor from a. 治 政 more positive viewpoint to treat the science-religion interrelation. With this new 大 立 aspect, the Neffian binaries represented by Carlyle and Mill supposedly may be ‧ 國. 學. shattered, and Carlyle’s imagination of an “Amalgamation” of “Heaven and Hell”. ‧. may turn to be possible.. sit. y. Nat. During the late twentieth and the early twenty-first centuries, doubting the. io. er. conflict thesis, some scholars have started to reexamine the warfare assumption and expanded new discourses concerning the science and religion interrelationships.4. al. n. iv n C Recent significant publications about between science and religion h einteractions ngchi U. include: “Dispelling Some Myths about the Split between Theology and Science in the Nineteenth Century” (1996) by Claude Welch, Victorian Science in Context (1997) 4. Nowadays, there are many academic institutes working on the subject of “science and religion interrelation.” For instance, Metanexus Institute in the United States is a global institute assembling scholars from departments of theology, history and philosophy of science, medical ethics, chemistry, and so on to deal with the subject of science-religion relationship. The website is http://www.metanexus.net/. In Cambridge University in England as well, there is The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion ( http://www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/faraday/ ). Other scholarly searches for the issue of “Science and Religion” can be found on the following websites: “Counterbalance: Science and Religion Project” (http://www.counterbalance.org/), “The Center for Theology and Science” (http://www.ctns.org/), “Science and Religion: Scholarly Organization and Resources” (http://www.religiousworlds.com/science.html), “Integral Science Organization: Individuals and their Works Relating to Integral Science” (http://www.integralscience.org/), “Science and Religion Forum: Seeking both Intelligibility and Meaning” (http://www.srforum.org/), “Institute of Religion, Science, and Social Studies” (http://www.religion.sdu.edu.cn/), “Global Perspectives: on Science and Spirituality” (http://www.uip.edu/gpss_major/), and “The Boston Theological Institute: Science and Religion” (http://www.bostontheological.org/programs/science_and_religion.htm)..

(22) Chang 22. edited by Bernard Lightman, Science and Theology (1998) by John Polkinghorne, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) by E. O. Wilson, both The Foundations of Dialogue between Science and Religion (1998) and Science and Religion: An Introduction (1999) by Alister McGrath, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life (1999) by Stephen Jay Gould, Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction (2002) edited by Gary Ferngren, Science and Religion 1450-1900: From Copernicus to Darwin (2004) by Richard G. Olson, etc. Generally, among these studies, there are general similarities. Firstly, they expect to discover new discourses within the supposed unbridgeable gulf between science. 治 政 and religion. Rather than oversimplifying the science-religion 大 relation as severe 立 hostility as the previous studies have done, the new studies intend to disclose ‧ 國. 學. possibilities and complexities between the two disciplines. Secondly, the new. ‧. science-religion scholars unanimously believe that before the end of the nineteenth. sit. y. Nat. century, science and religion shared a mutual relation, supporting and corresponding. io. al. er. to each other. In other words, between the two disciplines, there were harmony and interaction rather than malice and belligerence. Thirdly, these studies all agree that,. n. iv n C instead of a reality, the conflict theory of a socially constructed discourse h eisnmore gchi U. during the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. About a hundred years, the misconception of science-religion struggles has occupied our conception of the science-religion relation and misled our understanding of the past history. The new studies hence propose to expel the myth of the conflict assumption for the purpose of collapsing the disciplinary boundaries, looking for mutual interrelations among different fields of studies, and reexamining the past studies misled by the warfare thesis. In this dissertation, the new study about the mutual interrelation between science and religion thus will be introduced to reexamine “the Torch of Science” in Carlyle’s.

(23) Chang 23. Sartor. Rather than getting bogged into the conflict discourse and simply criticizing science and matter based on the Neffian binary opposition, this study will have Sartor been analyzed by demolishing the borderlines between science/religion, matter/spirit, and scientist/philosopher in order to represent more faithfully Carlyle’s concepts of “science,” “matter,” and “scientist.” I will argue that, more than criticizing science, matter, and the man of science, Carlyle in truth perceives and foresees the danger of the possible breaks of the harmonious relations between science/religion, matter/spirit, and the literary man/the scientific man. By fabricating a Clothes Philosophy, in a ridicule tone, he then proposes to remind his contemporaries of the intrusion of. 治 政 materialism, mechanism, and utilitarianism that will bring 大 about gaps and ruptures to 立 break the integrated unity into two poles. Carlyle never aims at strengthening the ‧ 國. 學. break between science and religion or matter and spirit. Instead, anticipating and. ‧. worrying the probable breaks of science from religion, matter from spirit, and the man. sit. y. Nat. of science from that of classics/religion, Carlyle in fact, on one hand, purports to. io. al. er. criticize the utilitarian use of science as well as the materialization of religion among. n. his contemporaries and, on the other, prospects to inform his readers of the true. C h and “religion.”U n i meanings, values, and uses of “science” engchi. v. There will be four chapters in this dissertation. The first chapter includes a literature review and an introduction of theoretical bases. From the review, this study will reveal the problems of the past analyses in reference to Carlyle and Sartor, that is, the beliefs in the sage theory and in the unity myth. From the theoretical discourses of Roland Barthes and Michael Foucault, the myth of Carlyle as a transcendentalist sage will be questioned and Sartor as an aesthetic unity to center the themes of spirit and religion will be dispelled. Freed from the sage and unity myths, both Carlyle and Sartor then will become texts and discursive sites to transmit the confrontations, transitions, as well as vicissitudes of diverse thoughts..

(24) Chang 24. The second chapter will aim at justifying Carlyle’s “Torch of Science” and revealing the “Torch’s” religious significances. Via the reexamination of the new studies to assert the mutually productive relation between science and religion in the nineteenth-century England, the main target that Carlyle intends to criticize in Sartor will appear: it is not the “Torch of Science” per se but its status quo. In other words, instead of intrinsically problematic, science is criticized by Carlyle because his contemporaries use science improperly with their intentions dominated by utilitarianism and mechanism. For Carlyle, the “Torch of Science” is of religious powers. Rather than destroying religious faith, the Torch of Science” serves as a. 治 政 sacred vehicle to explore not only the exterior/material大 world but also the 立 interior/spiritual universe. Accordingly, Carlyle never intends to avoid and criticize ‧ 國. 學. the “Torch;” instead, he encourages the proper use of science and even takes the. ‧. “Torch” as a potent vehicle to restore and reform the spiritual world.. sit. y. Nat. In the third chapter, the inseparable interrelation between spirit and matter as. io. al. er. well as the indivisible mutuality between the visible and the invisible in Sartor will be explored. To analyze from the concept of natural theology that was once popular. n. iv n C during Carlyle’s early age, I will argue Carlyle deems the spiritual and the h ethat ngchi U. material as the two sides of a unity—“a whole,” or God—that always correspond to and support each other. Through his theory of “natural supernaturalism,” Carlyle thus proclaims his faith in a mutually productive relation between the matter in the physical world and the spirit in the metaphorical world. Instead of a break between matter and spirit, from the matter in “nature” and the spirit in the “supernatural” Carlyle perceives the philosophy of a “whole.” Matter should not be jettisoned; yet, the seer has to open his inner eye to penetrate the true philosophy clothed in matter. Since matter is significant to be the “purse” to cloak the spirit, Carlyle never advises to take off the Clothes or to break off from matter; rather, he instructs his reader to.

(25) Chang 25. open the inner eye and to be wise for seeing into the truth of the “whole.” In the fourth chapter, I intend to examine Teufelsdrockh the protagonist in relation to “science” by references of Carlyle’s personal experiences, “science” as a vocation in the 1820s and 1830s, and the philosophy of science and the scientist advocated by William Whewell (1794-1866). As long as Carlyle opens Sartor with the “Torch of Science,” the protagonist named Teufelsdrockh supposedly represents the holder of the Torch to propagate Science. If Teufelsdrockh is highly related to science, then, who is he? More than a literary man or a philosopher, Teufelsdrockh should be a proto-scientist, an ideal scientist to be moral, spiritual, religious, and. 治 政 philosophic simultaneously. As the mutual relation between 大 science and religion, the 立 relation between the literary/religious man and the scientific man is harmonious and ‧ 國. 學. correspondent as well. For the ideal man of science, the purpose of the scientific study,. ‧. hence, is not for utilitarian application but religious exploration and spiritual. sit. y. Nat. improvement. In such circumstances, as a religious scientist, Teufelsdrockh reveals. io. al. er. that, on one hand, science is moral and religious during Carlyle’s early age, and on the. n. other, a scientist’s task is to discover the principle of God’s law in nature and to. C h in the principles.U n i practice His love and wisdom hinted engchi. v. In Coda, there will be concluding remarks about struggles and negotiations of the thoughts in “Carlyle” and “Sartor.” First, not simply a Victorian sage to seek religious solace and spiritual progress by creating Teufelsdrockh, “Carlyle” as a proper name indicates the confrontations, conflicts, and compromises of the ideas of science/religion, spirit/matter, as well as the literary/religious man/the scientific man in the 1820s and 1830s. Secondly, more than an aesthetic unity to illuminate transcendentalism, Sartor as a discursive museum exhibits the quarrels and alterations of the conflicting ideas in reference to science/religion and matter/spirit. As indicated by G. B. Tennyson that “Carlyle’s scientific inclinations have never been very.

(26) Chang 26. thoroughly explored” (21 note), hopefully, this study will provide new insights into “Carlyle’s scientific inclinations” and new thoughts on science and religion around 1820s and 1830s in England through the perspective on the nineteenth-century science-relation relations.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(27) Chang 27. Chapter One Carlyle, a Victorian Sage?. In English departments in particular…it has been unthinkable entirely to ignore the prose writings of figures such as Carlyle, Arnold, Ruskin, and company. But at the same time, it has been hard to know quite what to do with them. (Collini 14). [It is] language which speaks, not the author. (Barthes 168). [A] text is made of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures. 政 治 大. and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody,. 學. ‧ 國. 立. contestation. (Barthes 171). I. Introduction. Walter Whitman highly praised Thomas Carlyle as “a representative author, a. ‧. literary figure” (par. 2) of the nineteenth century in an elegiac prose. For Whitman, it. y. Nat. io. sit. was not merely Carlyle’s “literary merit” but his “touch of the old Hebraic anger and. n. al. er. prophecy” (par. 5) that made him a great poet of his age. Whitman then added further. Ch. i Un. v. that it was not appropriate to use the term, “prophecy,” to describe Carlyle’s value;. engchi. rather, “prophet” would be proper since “it mean[t] one whose mind bubble[d] up and pour[d] forth as a fountain, from inner, divine spontaneities revealing God” (par. 5). Three decades later, in Robert Huntington Fletcher’s A History of English Literature (1918), Carlyle again was praised as “a social and religious prophet, lay-preacher, and prose-poet, one of the most eccentric but one of the most stimulating of all English writers” (Par. 1). Since then “prophet-poet” was almost synonymous with Carlyle from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth. Due to Whitman’s appreciation and the early twentieth-century scholarly appraisal, “Thomas Carlyle” the name almost equates the term, sage-prophet, during.

(28) Chang 28. the years from 1860s to 1980s.5 Sartor Resartus, reflecting its author’s sagacity, hence stood for a modern spiritual-bible to moral- and life-philosophy. To ally Carlyle to a sage and Sartor Resartus to the Bible, generally, the traditional twentieth-century scholars all agreed that, firstly, Carlyle was a conscious “Author-God” purposefully creating a unique philosophy, elevating Carlyle as the founder of nineteenth-century transcendentalism. Secondly, Sartor Resartus was an aesthetic unity structurally organized and rhetorically coherent to center Carlyle’s theme of moral philosophy of man and man’s life. The “sage-prophet” discourse was problematic because, to take the author as. 治 政 an ultimate creator and the text as a complete unity, scholars 大 mistook the author as the 立 origin to produce meanings, and the work as an artistically-arranged structure of an ‧ 國. 學. aesthetic unity. They opined that, first, the author was able to create a never-said. ‧. discourse, able to dominate the meaning, to work for the author’s own intent, and able. sit. y. Nat. to combine all contested meanings congenially to each other. Second, they supposed. io. al. er. that there was necessarily an aesthetic unity to the work to combine the rhetoric, imagery, structure, and theme in the work via the author’s intention, forming. n. iv n C compatible interrelations between author work. A critic, consequently, was h e nand gchi U responsible for revealing the center of the work and to discover the aesthetic interrelations hidden within the labyrinthine meanings. Based on these assumptions, the twentieth-century traditional studies of Carlyle and Sartor thus mainly focused on the aesthetic unity of the work and the moral purposes of the author. To regard Carlyle as a prophet-sage and Sartor as a moral-philosophical instruction, the traditional scholars in fact sanctified both the author and the book. To be hallowed, the author was supposed to precede the book to “nourish the book” 5. Around 1930s and 1940s, however, due to the rise of Nazism and the eruption of the Second World War, Carlyle lost his reputation of a prophet-poet for his early affiliation with Goethe and Schiller as well as his enthusiasms about German Romanticism and transcendentalism (Tennyson 1984: xiv)..

(29) Chang 29. (Barthes 170). The author and the book hence “[stood] automatically on a single line divided into a before and an after” (170). For instance, the author, Carlyle, stood for the father of the book, Sartor, which represented the child to deliver faithfully the father’s idea and for posterity. Carlyle, the transcendentalist, then spontaneously left his noble spirit to his child, Sartor. “Carlyle,” as the name of the father, thus typified the center of thoughts, and Sartor, as a pious child, signified an aesthetic unity to convey the central idea of the author-father, Carlyle. The author-father was sacred and noble, since he was the fountainhead originating thoughts and wisdom, and the book-child was stable and dependable, because the lessons pouring from the book. 治 政 were true to the author’s intention. There seemed to be大 clear boundaries between the 立 author-father and the book-child. The father-author stationed himself high in heaven ‧ 國. 學. to leave his message in his book-child in the mundane world. The responsible and. ‧. trustworthy book-child never betrayed the father’s command and never diverged from. sit. y. Nat. its duty of advice, instruction, and moralization. According to such an interpretation,. io. al. author-father and Sartor the book-child.. er. there were necessarily the stable and reliable interrelations between Carlyle the. n. iv n C The hallowed author-child assumption modern h e n g ofc h i U studies, however, overvalues. the author. Due to the characteristics of the meanings—neither transparent nor steadfast—the author is by no means the ultimate origin and the sole creator of the work and the work itself is on no account an aesthetic unity able to combine the conflicting opinions and to work for morality only. The position of Carlyle, instead, should not be as high aloft as heaven but an indexical node to point a convergence of multiple discursive practices among the complex web of meanings. More than a transcendental figure to “create” meanings, the author should be regarded as an agent to transmit “already-said” meanings. Furthermore, the hallowed author-child assumption also misinterprets the.

(30) Chang 30. book-child as a closed territory. Meanings, however, due to their characteristic referring and deferring, are never stable within an assumed intact-border of the work. Meanings thus exceed the supposed boundaries of the book form, flowing across the imaginary boundaries of the work. Without any limits, the completion of the work and its aesthetic unity hence never exists but turns out to be merely the New Critic’s romantic imagination. Instead of taking the work as an accomplished art, late twentieth-century scholars then replace “work” by “text,” to highlight the attributes of borderlessness and intertextuality. Since they are borderless, meanings of a text can no longer be self sufficient but will be interrelated to the contexts of the text itself. The. 治 政 text is never independent but always relying on other texts. 大 立 To regard a work as a text, then, neither the author is the origin of meanings nor ‧ 國. 學. is the text the end of meanings. The “author can only imitate a gesture that is always. ‧. anterior, never original” and the “the book itself is only a tissue of signs, an imitation. sit. y. Nat. that is lost, infinitely deferred” (Barthes 170). Namely, neither is the author a. io. al. er. sanctified “Author-God” nor is the work an artistic unity and of biblical-like guidance. Meanings, whether the “already-said” or the “never-said” (Foucault Knowledge 25). n. iv n C stream through the book, flowing over of the book itself, even, over the h ethen bound gchi U author’s intentional control. Provided that “a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’. meaning (the message of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash” (Barthes 170), then, does “Carlyle” still represent, as in George P. Landow’s Elegant Jeremiahs, one of the “far-off Hebraic utterers, a new Micah or Habbukak” to “bubble forth [his words] with abysmic inspiration” (21)? On condition that the “oeuvre can be regarded neither as an immediate unity, nor as a certain unity, nor as a homogeneous unity” (Foucault Knowledge 24), then, does Sartor still represent, in John Holloway’s prominent The.

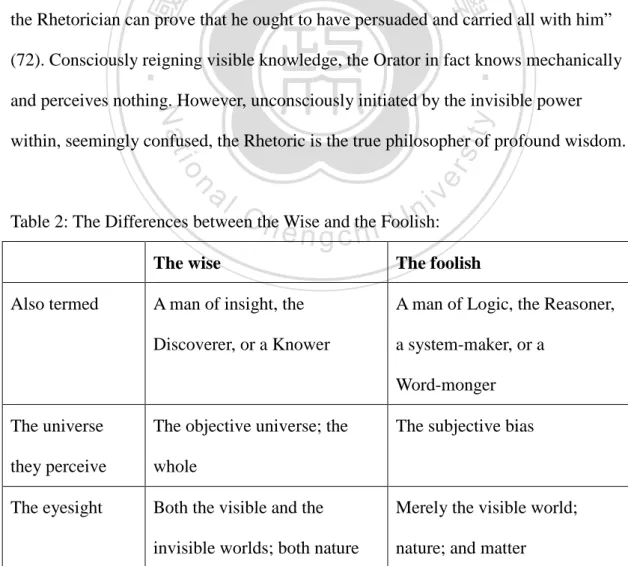

(31) Chang 31. Victorian Sage, an aesthetic unity “to express notions about the world, man’s situation in it, and how he should live” (1)? Simply put, what is Carlyle? Is Carlyle indeed a sagacious Author-God, not only generating new meanings of Victorian prophecy but also creating a new form of the sage-prose writing? And what is Sartor Resartus? Is Sartor indeed an aesthetic unity, not only faithfully conveying the Author-God’s meanings and independently standing for other meanings? The purpose of this chapter hence is to reexamine “Carlyle” the author and to review “Sartor Resartus” the text from the concepts of the author and the text. Instead. 治 政 of honoring Carlyle the sage-philosopher and lauding the 大aesthetics and the morals in 立 Sartor in the manner of the New Critics of traditional studies, I shall, first, reconsider ‧ 國. 學. Carlyle the author from the concepts based on Barthes’s death of the author and. ‧. Foucault’s author function, and second, to review Sartor the text from Foucault’s. sit. y. Nat. archaeological viewpoint. With the interrogation of the author’s status and the work’s. io. al. er. unity, I will argue that, first, more than a stereotype of a Victorian prophetic sage, “Carlyle” functions as a proper name to indicate the adaptation, transformation, and. n. iv n C modification of certain ideas such as matter, spirit, nature, the hscience, e n g creligion, hi U. supernatural, scientists, and philosophers. Second, more than an aesthetic unity about the spiritual elevation of a lost philosopher, Sartor the text stands for a discursive site of the confrontation, conflict, and contradiction of multiple voices, resembling a museum that exhibits the ideas such as the visible, the invisible, the wise, the foolish, the Baconian scientist, and the Newtonian scientist of early nineteenth century Britain. Before freeing the author and the work from the traditional myths of an all-powerful “Author-Father” and an obedient “book-child,” this study will start with a review of the past studies in reference to Carlyle and Sartor. This review is of two.

(32) Chang 32. purposes: on one hand to discover the confinements of previous studies and on the other to delve into the blind points for further breakthrough. After an epistemological review of the Carlyle studies in the past centuries, then, there will be the interrogations of the author and the work to succeed.. II. The Modern Interpretations of Carlyle and Sartor Resartus and Their Problems (1) The New Criticism With regard to the studies concerning Carlyle and Sartor, Emery Neff, who. 治 政 published Carlyle and Mill in 1926 and Carlyle in 1932, 大can be said to be the pioneer 立 of Carlylean studies. The earliest scholar of the New Critic trend, Neff focused his ‧ 國. 學. studies on the historical events during the nineteenth century, Carlyle’s biography,. ‧. Carlyle’s literary purposes and Carlyle’s moral lessons. In Neff’s analysis, “Carlyle. sit. y. Nat. and Mill,” the two representative figures of the nineteenth century stand for the. io. al. er. models of intellectual opposites in the recurrent philosophical battles: “the contrasting types like Mill and Carlyle, scientists, and artists, positivists and transcendentalists,. n. iv n C individualists and authoritarians, constantly in the world” (1974: 393-94). Neff’s h e n grecur chi U analysis is typically the dualism to divide good from the evil, religion from science, transcendentalism from positivism, as well as spirit from matter. For instance, Carlyle is regarded as a stereotypical spiritualist, moralist, and transcendentalist, while John S. Mill (1806-73) is the stereotypical figure symbolizing a utilitarian, mechanical, and scientist. Even if not openly declaring it, Neff in fact praised Carlyle greatly and took sides with him because, during the early twentieth century, the demand for moral lessons and spiritual sublimation in literature still prevailed. Neff’s dualism in analyzing Carlyle and Mill also indicates the significance of literature to conduct social responsibility..

(33) Chang 33. After Neff, however, the studies concerning Carlyle and his “non-fiction prose” were slumberous because during several decades from 1930s to 1970s, the dominant Anglo-American studies fell into the myth that, as Stefan Collini comments, “the almost religious significance attached to the concept of ‘literature’ was coming to be focused on the Holy Trinity of poetry, drama and the novel” (16).6 “[N]on-fiction prose,” neither poetry, nor drama, nor the novel, was ignored because its form, “nearly limitless” (17), resisted any categorization. Hardly defined and classified, the study of non-fiction prose then undergone a spell of neglect. Not until the heyday of New Criticism during the 1950s and 1960s was there increased debate of the legitimacy in. 治 政 research of “non-fiction prose writing,” including those大 of Carlyle’s, in orthodox 立 Anglo-American literary studies. A group of scholars, kindled enthusiasm for ‧ 國. 學. legitimating the studies concerning not only the works of Carlyle, but also those of. ‧. John Newman (1801-90), John Ruskin (1819-1900), and Matthew Arnold (1822-88).. sit. y. Nat. These scholars discovered the similarities in rhetoric techniques, aesthetics and. io. al. er. morals among non-fiction prose writers and started to categorize these writers and. n. their works. The studies of the “non-fiction prose” henceforth increased from the. Ch 1950s and peaked during the 1960s.. engchi. i Un. v. In order to legitimate non-fiction prose writings, John Holloway published The Victorian Sage: Studies in Argument in 1953, intending to define a new category for the non-fiction prose writers in the literary field. In his study, Holloway on one hand redefined writers, titling Carlyle, Newman, Ruskin and the others as “Victorian Sages,” and on the other, generalized the aesthetics, literariness, and purposes (morals) in the “sagistic writings.” Holloway assumed that during the Victorian age, a new mode of literary genre, “sagistic writing,” had sprung up—in the form of the. 6. The other reason for the stillness of the Carlyle study is the taboo of Nazism and Germanism during and after the Second World War..

(34) Chang 34. “non-fiction prose” and for the purpose of moralizing. He further induced that among these sagistic writings, there were several attributes in common. First, “[t]heir work reflect[ed] an outlook on life, an outlook which for most or perhaps all of them was partly philosophical and partly moral” (1). Namely, the sagistic writings were of enlightening purposes, aiming to lead the reader to a philosophical and moral life. Second, in order to “[quicken] the reader to a new capacity for experience,” the sages “work[ed] in the mode of the artist in words…, by virtue of an appeal to imagination as well as intelligence, and by virtue of a wide and subtle control over the reader’s whole experience” (10). That is to say, the sages were conscious of the difficulty to. 治 政 conduct the reader to “the good” and hence skillfully applied 大 literary techniques of 立 imagination and narrative to tempt the reader’s interest. ‧ 國. 學. Holloway justified the studies of non-fiction prose in The Victorian Sage. ‧. through categorizing the common ground of their purposes and deducing the. sit. y. Nat. universality of the literary techniques among the non-fiction prose writers. He. io. al. er. reasoned that on the surface the sages argued differently in theories, but in a deeper sense, they were characteristically the same in adopting “illustrative incidents” (12). n. iv n C and their use of “figurative language” to turn their difficult arguments into simple h e(13) ngchi U stories for their reader’s to grasp their meaning. Different in opinions, all of the Victorian sages were keen to “[quicken] the reader” (13) with their new philosophies by similar techniques. The sages hence on the one hand were conscious of their contemporary socio-cultural problems and on the other aware of their duties to rectify the people. In Holloway’s criticism, for instance, the Victorian sages acknowledged their outstanding intelligence and reckoned themselves to be above the common people and piercing into the future and managing the hereafter. Holloway’s sages hence were saints, standing aloft beyond the masses by their sensitive perceptions and special mission..

(35) Chang 35. Among all of the prose writers in Holloway’s The Victorian Sage, Carlyle was the most typical model of the traditional sage, one who adopted illustrative incidents and figurative language to create easily the understood knowledge for the “Life-Philosophy” (Holloway 21). In purpose, Carlyle “want[ed] to state, and to clinch, the basic tenets of a ‘Life-Philosophy’” (21), and he believed that “Knowledge of God comes from confident belief in Him” (22). In literary method, Carlyle was gifted in using “Biblical language” and “wildest rhetoric” (24) to create persuasive effect and to succeed in his moralizing purpose. Holloway considered that Sartor, “In a word…[was] anti-mechanism” (23). To convey this central tenet, in Holloway’s. 治 政 view, Carlyle adopted three techniques to achieve the purpose 大 of “anti-mechanism” in 立 his philosophy. First, he used “a wild, passionate energy run[ning] through [his work], ‧ 國. 學. disorderly and even chaotic, but leaving an indelible impression of life, force, vitality”. ‧. (26). Second, Carlyle was gifted in using “the dramatization of discussion” (27) to. sit. y. Nat. give impression to his readers. The third feature of Carlyle’s work was his prosperous. io. al. er. usage of figurative language in rhetoric devices that not only helped his readers easily become involved in the mythic character but also, most importantly, create the. n. iv n C literariness of his work, pushing hishwork into the legitimate e n g c h i U category of English literature. Holloway’s study, principally, aimed to recognize the legitimate status of the non-fiction prose writings in literary studies, to compete the non-fiction prose with the Holy Trinity of poetry, drama, and the novel. Even if declaring that his study was “not evidence for one theory” (290), in fact, Holloway achieved redrawing the boundaries of “non-fiction prose” writing and to redefine the limitless genre through the purpose and technique. His definition of “sage literature,” though, was not theoretically successful, and stirred up a wave of “drawing the boundaries” for non-fiction prose later. During the 1960s, there was proliferation of the studies concerning the “sagistic.

數據

Outline

相關文件

(2)Ask each group to turn to different page and discuss the picture of that page.. (3)Give groups a topic, such as weather, idols,

Having found that the fines as a whole are a measure falling within the scope of Article XI:1 and contrary to that provision, the Panel need not examine the European

Krajcik, Czerniak, & Berger (1999) 大力倡導以「專題」為基礎,教導學生學習科 學探究的方法,這種稱之為專題導向的科學學習(Project-Based Science,

In our Fudoki myth, the third, sociological, “code” predominates (= the jealous wife/greedy mistress), while the first, alimentary, code is alluded to (= fish, entrails), and

The PE curriculum contributes greatly to enabling our students to lead a healthy lifestyle with an interest and active participation in physical and aesthetic

Understanding and inferring information, ideas, feelings and opinions in a range of texts with some degree of complexity, using and integrating a small range of reading

Promote project learning, mathematical modeling, and problem-based learning to strengthen the ability to integrate and apply knowledge and skills, and make. calculated

健行學校財團法人健行科技大學 清雲科技大學 台灣首府學校財團法人台灣首府大學 致遠管理學院 大華學校財團法人大華科技大學 大華技術學院 醒吾學校財團法人醒吾科技大學