Dynamics of Taiwan-Mainland China Economic

Relations: the Role of Private Firms

Tse-Kang Leng, Ph.D.

Associate Research Fellow

Institute of International Relations, National Chengchi University

64 Wan Shou Rd, Wenshan Taipei, Taiwan, 116 Tkleng@cc.nccu.edu.tw

Dynamics of Taiwan-Mainland China Economic Relations: the Role of

Private Firms

*ThisarticleexaminesTaiwan’seconomic statecraft toward mainland China and the role of the business community in cross-Strait economic interactions. It argues that the realist perspective on economic statecraft cannot explain the current political economy between Taiwan and mainland China. The realist thought of international political economy argues that states are the only meaningful actors in the world economy. In an anarchic international society, relative gains in wealth and power are the goals of actors. The structure of bilateral power, either in political or economic terms, determines the“winners”and “losers”in theinternationalarena.Foreign tradeand investment policies can thus be utilized as an instrument to enhance national interests. Coercive and exchange-oriented “economicstatecraft,”such aseconomicsanctionsand economicaid, should be implemented according to careful calculation of foreign policy goals.1 From this perspective, economic interaction between Taiwan and mainland China could be used to serve political purposes. If the state can control the tempo and trends of economic interaction effectively, trade and investment can be greatly shrunk or expanded according to policymakers’politicaljudgment.

However, research on economic statecraft shows that coercive economic statecraft and economic sanctions do not work well after the rise of new actors such as

*

This article is revised from a paper presented at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars (Washington D.C.) on September 10, 1997.

1

David Baldwin, Economic Statecraft, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1985.

註解: 註解:

non-governmental organizations and multinational corporations (MNCs).2 The home country government has difficulties extending its influence to corporations which acquire their capital, technology, and sales through the international market. As overseas

affiliations becomemore importantto firms,itisthehostcountry’slaws,ratherthan the homecountry policies,thatreally influenceMNCs’daily operations.Hence,thenetresult of market internationalization is that there is greatly intensified competition among states for world market shares. That competition forces states to bargain with firms to locate their operations within the territory of the state, and with national firms not to leave home.3 The realist assumption that states can control economic incentives to conduct political goals thus cannot fully stand. As internationally-oriented firms occupy strategic positions to bargain with home and host countries, states have to adjust their roles in promoting or constraining economic transactions.

Taiwan’seconomicpolicy toward mainland China providesagood examplein examining this new type of interaction between the state and firms. The first section of thisarticlewillanalyzewhy Taiwan’seconomicpoliciestoward mainland Chinaare “irrational”-- that is, the political controversies behind the economic interaction. Out of national security concerns, the Taiwan government has tried to impose restrictions on the businesscommunity’sinvestmentin mainland China.Thesecond section ofthe article explains the governmental policies which regulate such economic activities. Taiwan business people have escaped governmental restrictions and launched new investment projects on mainland China based on their own calculations of economic profits. The real

2 Kenneth Rodman,“ Publicand PrivateSanctionsAgainstSouth Africa,”Political Science Quarterly,

Vol 109, number 2, 1994, pp. 313-334; Gary Hufbauer, Jeffrey Schott, and Kimberly Elliott, Economic

party which they must bargain with are the local authorities of host countries. Hence, these regulative policies have proven not to be so successful. Part three analyzes how the Taiwanesebusinesscommunity hasdealtwith itshomecountry’srestrictive policies, and the benefits and constraints they meet when they invest in mainland China. Finally, this article will re-examine the effectiveness of economic statecraft in the era of market internationalization and the changing role of the state.

Political Controversies in Cross-Strait Relations

Cross-Strait relations have experienced various ups and downs in the past forty-nine years. Prior to Chiang Ching-kuo’sdecision to open up interactionswith mainland China, confrontations between the two sides were an extension of Chinese civil war and a reflection of international bipolar confrontation during the Cold War era. Since 1987, cultural and economic ties between Taiwan and mainland China have been greatly enhanced. Mainland China resumed military pressure on Taiwan after Lee Teng-huei’s visit to the United States in June 1995. The situation escalated into a crisis after mainland Chinalaunched missiletestsnearTaiwan’snorthern and southern portsbeforeTaiwan’s presidential election in March 1996. U.S. aircraft carrier groups were forced to intervene in the Taiwan Strait. As a result, cross-Strait relations reached a new low. Signals of resuming cross-Straits talks did not appear until February 1998.

The first major political obstacle impeding cross-Strait relations is the different interpretation ofthe“oneChinaPrinciple”by thetwo sides.From thePRC’sperspective, “oneChina”meansfirst,thereisonly oneChina;second,Taiwan isaprovinceofChina;

3 Susan Strange,“States,Firms,and Diplomacy,” InternationalAffair

and third, PRC is the sole legitimate government representing the whole of China.

China’ssovereignty residesin thePRC,and Taiwan can enjoy somedegreeofautonomy in domestic affairs. Since Taiwan is a province of China, it can participate in the

international arena only as a local government.4 Underthe“onecountry,two systems“ formula,thedegreeofautonomy which Taiwan enjoyscould even belarger than Hong Kong’s.However,Beijing’sbottom lineisthatthe“onecountry”definitely refersto thePRC.Beijing’sstrategy hasbeen to pressTaipeito open up person-to-person interaction and initiate political dialogue with mainland China while at the same time vetoing Taiwan’sparticipation asafull-fledged political entity in international

organizations.“Peacefulmeans”havebeen adopted in thehopethatthey willnarrow Taiwan’soptionsand giveitno choicebutto negotiateforreunification.ThePRC has reserved the right to use force if these peaceful means fail.

Taiwan’sinterpretation on the“oneChina”principleisquitedifferent.From Taiwan’sperspective,thepoliticalreality acrosstheStraitsisthattwo “equalChinese entities”havegoverned Taiwan and mainland China separately for forty-eight years. Although both Taiwan and the mainland are Chinese territories, their political and economic systems are totally different. PRC has never effectively controlled the soil of Taiwan since 1949, and vice versa. Taiwan stresses that any proposals imposing conditionswhich are“suitableonly afterChina’sre-unification with Taiwan are not suitableatthecurrentstage.”5

Thus,themainland’s“onecountry,two systems”formula is notsuitablefora“sovereign state”liketheRepublicofChinaon Taiwan.Taiwan

4 “ TheTaiwan Question and theReunification ofChina”,

Beijing Review, September 6-12, 1993, pp.

arguesthatto reflectthecurrentsituation,theterm of“adivided Chinagoverned by two separatepoliticalentities”ismorerealistic.6

Taiwan’sdomesticsituation renderscross-Strait relations even more complex. From themainland’sperspective,democratization and Taiwan’squestforautonomy areequal to Taiwan independence. Democratization has created new actors in policy-making, as social forces have also received the chance to participate in the decisionmaking process. Policy outcomes, like most democratic regimes, are always the result of compromise among competing groups, the latter of which include both pro-independence and pro-unification factions. According to various opinion polls, although the majority of the Taiwanesepeoplesupportthe“statusquo”,ten to fifteen percentofthepopulation are pro-independence. People who support immediate unification also occupy about fifteen percent. To win the largest number of votes, the Taiwanese government has to find the “gray area”between unification and independence. Otherwise, officials will be condemned as“following in thefootstepsoftheothersideoftheStraits.”Taiwan’s diplomatic initiatives can also be explained as the quest of being recognized as an dignified and autonomous entity.

Hence, Taiwan’smiddle-road policy toward unification has been under severe attack from mainland China.Taiwan’sattemptsto find an autonomousrouteofnational

developmenthasthusbeen explained as“deviating”from theoneChinaprinciple.Hence, even though cross-Strait economic and cultural relations have been greatly improved in the past ten years, Taiwan and mainland China still remain confrontational on political

5

This paragraph appears in Koo Chen-fu’sspeech atUC-Berkeley, September 27, 1996. Koo is the Chair oftheStraitsExchangeFoundation (SEF),Taiwan’ssemi-official institution responsible for talks with its Chinese counterpart. For the full text , see Zhongguo Shibao, September 28, 1996.

issuesand in theinternationalarena.Cooperation in “low politics”hasnotspilled over into “high politics”;7 instead, political differences have cast a shadow over the prospect of forming an integrated economic circle based on equality and mutual benefits. Political conflicts have also influenced Taiwanese leaders in their economic policies toward mainland China.

“JiejiYongren” :Taiwan’sPrinciplesRegarding Cross-Strait Economic

Interactions

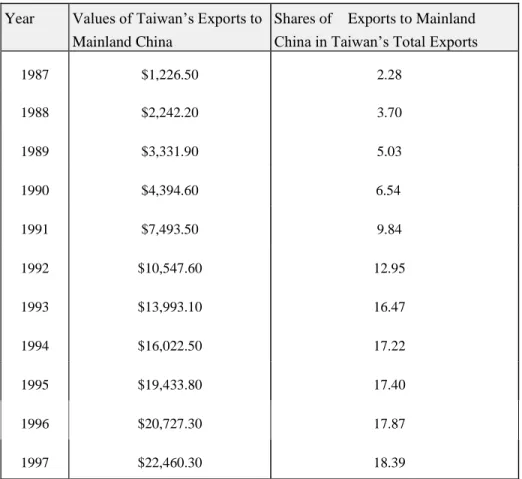

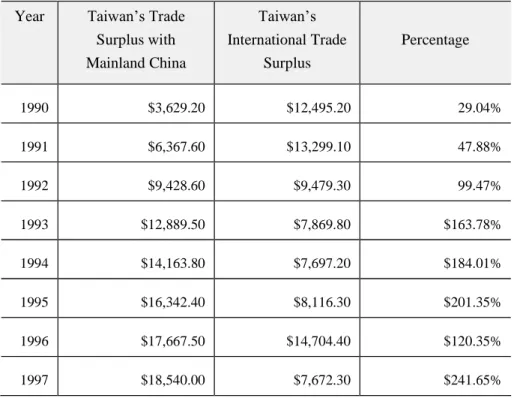

The preceding analysis has outlined the political conflicts between Taiwan and mainland China. Under these circumstances, national security has become a main concern forTaiwan’smainland economicpolicy makers.Theirbasicperception isthatmainland Chinaistrying to “useeconomicinteraction to forcepoliticalconcession”and “ push the business community to encroach on theTaiwanesegovernment.”8 According to statistics shown on Table 1 and Table 2, cross-Strait economic interactions are asymmetrical, as Taiwan’sexportdependenceon mainland China reached 18.39 percent in 1997. Furthermore, if not for its trade surplus with mainland China, Taiwan would actually have an overall international trade deficit. High economic dependence may lead to capital outflow to mainland China, decrease domestic investment, and expose Taiwan to the mainland’spoliticalinterventions. Thishigh economicdependenceand theescalation

6 Taiwan’sGovernmentInformation Officeusestheconceptof“onedivided China” to replace“one

China” in formalpressreleases.SeeZhongguo Shibao, February 3, 1997.

7

For a more detailed discussion on the relationship between economic interdependence and political cooperation, see Tse-Kang Leng,“ EconomicInterdependenceand PoliticalIntegration Between Taiwan and Mainland China: A Critical Review,”Chinese Political Science Review, V. 26, June, 1996.

of political confrontation since 1995 has led Lee Teng-hui to request the business community to be jieji yongren (cautious and self-restrained ).9

(Table 1 and 2 about here)

Hence,Taiwan’seconomicpoliciestoward mainland Chinacannotbefully understood through cost-benefit analysis. Due to political risk concerns, the state has tried to takepartin thisbooming economicrelationship and “apply thebrakes”to protect national security. Three official principles have been declared in regards to governing cross-Strait economic interactions. The first principle is balance between national security and economic benefits; the Taiwan government will open up economic interactions step by step, depending on the political situation across the Taiwan Strait. The second principle is national interest . The main concern in promoting cross-Strait economic relationsisTaiwan’seconomicautonomy and itscompetitivenessin theinternational market. Economic relations with mainland China should thus enhance, rather than reduce, Taiwan’seconomicsuperiority.Thethird principleisstability;thelong-term goal of Taiwan’seconomicpolicy toward mainland Chinaisto promotelong-term political stability across the Taiwan Strait.10 Under these basic guidelines, issues such as opening direct trade, postal, and transportation links are under consideration, but have not been realized. Some ad hoc treatmentssuch as“off-shore transshipmentcenters”arebeing established.A “NationalDevelopmentConference”convened in late1996 also urged the

8

Lien Chan, Government Report to the Legislative Yuan, September 6, 1996

9

Lee Teng-huei, Opening Remarks at the 3rdConference on Business Management, Taipei, September 14, 1996

10

Cross-Strait Relations and Economic Policies Toward Mainland China, Taipei, Mainland Affairs

governmentto “prudently assessinvestmentby large-scale Taiwanese and make reasonablestandardsforregulation”.11

In brief, Taiwan has tried to achieve multiple goals through its economic

connections with mainland China. However, due to political confrontations, economic benefits have been sacrificed for the sake of protecting national security and autonomy. The speed of opening trade and investment to mainland China has also been influenced by the degree of political intensity across the Taiwan Strait. For example, the jieji

yongren advisory was released in September 1996, a few months after the Taiwan Strait

crisis. In January 1995, Taiwan also released an ambitious plan to build Taiwan as an “Asia-PacificRegionalOperation Center”.Thisplan featuresTaiwan asabasefor multi-national corporation to exploit opportunities in booming Southeast Asia, mainland China, and other regions in the Asia-Pacific market.12 However, in a report to the National Assembly in August 1996, President Lee indicated that the Asia-Pacific Regional Operation Centercould notbe“an instrumentto promoteeconomicrelations with mainland China.”Themain themeofcross-Straitrelationsis“stability”.Even though Taiwan is currently engaged in trade and investment liberalization, cross-Strait economic interactions are thus still subject to government regulations.13 Before the Taiwan Straits crisis in 1996, the main theme of cross-Straitrelations,asTaiwan’s then-Premier Lian Chen indicated, is economic interaction. Later on, the main theme

11

National Development Conference Resolutions, Taipei, National Development Conference Secetariat,

January 1997, pp.19-20.

12

The Plan for Developing Taiwan as an Asia-Pacific Regional Operations Center, Taipei, Council for

Economic Planning and Development, January 5, 1995, p. 5.

13

waschanged to “stability”instead ofeconomicinteraction.Thissharp contrastexplains the contraction policy due to the political rivalry between the two sides.

Taiwan’sInvestmentPoliciesToward Mainland China

The ban on Taiwanese investment in mainland China was lifted in 1991. However, only indirect investment is allowed by the Taiwanese government. Since 1991, indirect Taiwanese investments in mainland have been divided by the government into three categories: those on the permitted list, those on the prohibited list, and special cases. Although theprohibited listhasshrunk since1991,the“specialcase”categories,which list 4309 items, allow economic bureaucracies to determine which projects can be

approved on a case-by-case basis.14 Asforthe“prohibited list”,itincludesinvestmenton infrastructure, high-tech industries, and service sectors.15

In controlling cross-Strait investments, the Taiwanese government has attempted to minimize negative impacts on domestic development, and gradually release restrictions on investment. In May 1997, the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) released a set of new criteriaforrating the“specialcases”categoriesofinvestmentprojects.Forexample, if the industry is labor-intensive and less competitive in the international market, the chance of being approved to invest in mainland China is higher. By the same token, if firmshavemoreinvestmentsin Taiwan’sdomesticmarketand internationalmarketthan mainland China, or accumulate investment capital from the international market rather

14

than Taiwan’sdomesticmarket,therating forapprovalwillalso behigher.16 According to these criteria, economic bureaucracies quantify each investment project and give scores. Moreover, the new criteria sets the ceiling of any single investment project at 50 million US dollars. This new set of regulations is based on the hope that Taiwanese investment in mainland China will be used as an instrument to transfer outdated technologies and labor-intensive industries. Under these new criteria, larger investment projectshaving “reverse” impactsonTaiwan international competitiveness and domestic investment would be greatly constrained.

Business Reactions to Governmental Regulations -- Bargaining with the Home Country

Reactions toward the new governmental regulations have been mixed. In May 1997 year, two conflicting opinion poll results were released. The Ministry of Economic Affairs indicated that in an opinion poll that of the general public, 94 percent agreed that “nationalsecurity should bethefirstpriority in initiating economicpolicies toward

mainland China”;46 percentagreed thatthegovernmentshould “increaserestrictionson investmentin mainland China”;and 20 percentagreed thatthe“currentrestrictions should remain thesame”.17

In contrast, the Chinese National Federation of Industries, Taiwan’speak businessassociations,released adifferentpollresult.In asurvey of Taiwan business people in mainland China, 50 percent of them did not agree with the jieji

15

Gongshang Shibao, May 29, 1997

16

Zhongyang Ribao, May 29, 1997.

17

yongren policy. Furthermore, 30 percent of the them planned to expand, instead of

withdraw, their investments in mainland China.18

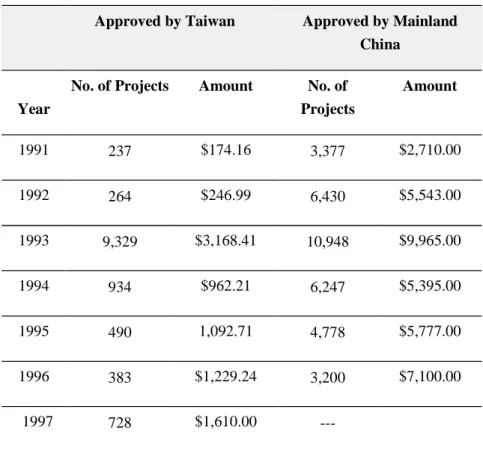

Technical factors, such as the way questionnaires are asked, may influence poll results. However, this sharp difference in results emphasizes the ambition of the economic bureaucracies to promote their regulatory polices, and the reluctance of the businesscommunity to follow thegovernment’slead.Generally speaking,official policies are lagging behind business incentives. According to the“StatuteGoverning RelationsBetween PeopleofTaiwan and theMainland Area,”alltheinvestment activities in China must be approved in advance by the Taiwanese government. However, the statistics show that most of the investment projects on mainland China from Taiwan are not screened by the Taiwan government. For example, in 1996, Taiwan statistics indicate that US$1.2 billion and 383 investment projects were approved by the government. However, the mainland statistics shows that US$7.1 billion and 3200 investment projects from Taiwan were negotiated. Table 3 displays this sharp contrast.

(Table 3 about here)

As Taiwanese enterprises have become internationalized, it is becoming harder for the government to control capital flows to mainland China. The most recent trend for the Taiwanese enterprises is to obtain capital in the international capital market to support their mainland projects. The favorite places for Taiwanese business communities are Singapore and Hong Kong. Wong-Wong Cookies Company, the biggest Taiwanese company of this kind in mainland China, has accumulated more than US$63 million from the Singaporean stock market. Even though Hong Kong has been an integral part of

18

China since July 1, 1997, many Taiwanese companies are optimistic about its highly liberalized capital market and are utilizing Hong Kong as a base of financial

management .19 Other multi-national corporations, such as Formosa Plastics, use their branch companies or subsidiaries in a third country to undertake their projects in

mainland China. Moreover, Taiwanese investors can bring their capital out of Taiwan by transferring foreign exchange earned from exports. Exporters sometimes retain their foreign exchange to invest in mainland China. According to Citibank in Taipei, the amount of foreign exchange retained by Taiwanese exporters increased form US$2.89 billion in 1987 to US$24 billion in 1991. A large portion of this foreign exchange flows directly into China , and Taiwan has been unable to control this capital outflow. 20 In reality , if the investors own double nationality and do not have residence status in Taiwan, their investment activities are outside legal restrictions.21

Another factor which may contribute to the difficulties in controlling business activities is the increase of channels through which capital can be acquired. According to various surveys, small and medium Taiwanese businesses in mainland China acquire about 56-59 percent of their capital from Taiwan, 25 percent from mainland China, and 13 percent from a third country.22 However, as China has gradually opened up its market in the service sector, this situation is gradually changing. More foreign banks have set up their branch offices in mainland China and provided necessary loans to the Taiwanese

19

Jingji Ribao, March 3, 1997.

20

Tse-Kang Leng, The Taiwan-China Connection: Democracy and Development Across the Taiwan

Straits, Boulder, Westview Press, 1996, p.114

21

According to the current Nationality Law in Taiwan, it is legal to have a double nationality.

22

Tehchang Lin, Zhonghua Minguo Zhong Xiao qi ye zai Guangdong Sheng di Touzi yu Liangan Zheng

Jing Hudong Guanxi ( Taiwanese investment in Guangdong and the Politics of Economic Interaction

business community. Local banks in mainland China have also eased their restrictions in lending to Taiwanese enterprises. Furthermore, the mainland government is considering allowing Taiwanese banks to set up branch offices in the mainland, opening the stock market for Taiwanese businesses, and further releasing other financial restrictions on the Taiwanese business community.23 In reality, to better serve the business community, Taiwanese banks have been well-prepared to set up branch offices in mainland under official prohibitions. Although the mainland government has declared that some

Taiwanesebankshavebeen setup,Taiwan’sInvestmentScreening Committeehasnot found any proof of such activities.24

Based on interviews carried out by the author in Guangzhou and Shengzhen in 1997, the jieji yongren policy has not had significant impacts on small and medium-size businesses from Taiwan; they are many steps ahead of government policies, and will continue to be so in the foreseeable future. Medium-sized enterprises have extended their reach in the anticipation that prohibitions will be lifted. For example, although the government still bans investment on cement industries in mainland China, major cement companies have began to establish factories and other related industries, i.e., aggregate materials, in preparation.25 Cement industries have also used the collective bargaining power of trade unions to press the Taiwanese government to lift the restrictions.26

Therealtargetofregulatory policiesisTaiwan’sbig enterprises. In June 1990, after severalvisitsto China,Y.C.Wang,thepresidentoftheFormosaGroup,Taiwan’s “dragon head”in plasticand petro-chemical industries, announced a plan to build a US$5

23

Gongshang Shibao, June 19, 1997

24

Lien He Bao, March 12, 1997; Gongshang Shibao, July 3, 1997.

25

billion petrochemical complex on Haicang Island near Xiamen in Fujian province. The Haicang project came as a major shock to policymakers in Taiwan, as the US$5 billion investmentwasaboutequalto Taiwan’stotaldomesticinvestmentbetween 1980 and 1989, and thus opened a new era of state-business bargaining. In late 1991, under pressure from high-ranking officials, Wang declared that the Haicang project was

“postponed”,butnotcanceled.Atthesametime,heurged thegovernmentto re-negotiate terms for a new petrochemical complex in Taiwan. In June 1992, the government finally approved Wang’sprojectto build aUS$9.5 billion naphthacrackerin southern Taiwan, much bigger than the mainland project. Furthermore, The Formosa Group also struck a deal with the government under which the company agreed to fund much ofthezone’s infrastructure in return for long-term low-cost financing of US$5.4 billion. Other concessions included a five-year tax break, low-cost water supplies, and a government agreement to fund port development and other costs.27

Y.C.Wang’ssecond attemptto challengeTaiwan’smainland economicpolicy has been his power plant project in Zhangzhou, Fujian province. In May 1996, the US$3 billion investment project was approved by the mainland’sStateCouncil.Many extraordinary preferential treatments, such as low-cost land and tax breaks, were granted. Preliminary construction was launched in May, 1996.28 When the news was released in mid-1996, it caused a majorshock to Taiwan’smainland economicpolicies.

Formosa’spowerplantprojectisatypicalcasein underlining how multinational corporationscan evadeahomecountry’scontrol.In thisUS$ 3 billion investment,the

26

Liangan Jingmao Tongxun, July , 1997, p.35

27

For a detailed discussion ofWang’scase,seeLeng,1996.

28

mother company only contributes US$ 400 million, or approximately 14 percent of the total.Formosa’soverseassubsidiarieswillplay the majorroleoftheinvestors. Internationalbanks,including Japan’sMitsubishiand Sumitomo and severalGerman banks, have expressed their interest in loaning more than 2 billion US dollars.29 In other words, major financial support has been from international, rather than domestic, sources. According to the reviewing rules of the Economic Screening Committee, Taiwanese companies’foreign subsidiariescan freely investin mainland Chinawithoutreporting to thegovernmentifthemothercompanies’stock sharedoesnotexceed 20 percent.In the Formosa case, the mother company holds only 10.6 percent of the stock.30 In other words, in legalterms,thegovernmentwould find itdifficultto block Y.C.Wang’smainland project.

Although Wang finally submitted the investment project to the government for review, he himself withdrew the proposal afterwards under the pressure of the MOEA. However, as in the Haicang case, this project has not come to a stop; Wang has made it clearthattheZhangzhou projectwillnotbeused to “supportthebandit”,claiming thathe intends to support more Taiwanese companies in mainland China, import more

equipmentfrom Taiwan,and enhanceTaiwan’sinternationalcompetitivenessthrough economicdivision oflaborwith mainland China.Hehasstated thathewillwaitfor“no morethan oneyear”foragovernmentresponse.31

29

Zhongguo Shibao, July 9, 1996.

30

Zili Zaobao, May 29, 1996.

31

The Taiwanese Business Community in Mainland China -- Interactions with Host Countries

Asindicated earlier,themain concern ofTaiwan’spolicy regarding investmentin mainland China is that the Taiwan business communitymay becomea“politicalhostage” if cross-Strait relations grow more tense. However, Taiwan business people have

gradually developed their own strategies of survival, forming a relationship of coexistence with local governments, and thus protecting their economic interests and maintaining their autonomy in doing business in the mainland.

Mainland China’sbasicpolicy hasbeen to separatepoliticaldifferencesfrom economic interactions, and to utilize economic benefits to promote more political openness.Afterthemainland’smissiletestsof1995,theconfidenceofTaiwanese investors significantly decreased. According to an opinion poll of Taiwan business people conducted at the end of 1995, 72.36 percent of the respondents agreed that conflicts in the Taiwan Straits would influence their confidence in investment, and 84.1 percent agreed that such conflicts would increase the political risks of investment.32 Some reports even indicated that mainland China tended to block Taiwaneseinvestors’attemptsto withdraw capital from mainland China; legal and commercial disputes were also on the rise.33

Under such a situation, the Chinese central government attempted to appease the Taiwan business community. Beijing has stressed that the missile tests were aimed at discouraging effortsto create“two Chinas”and notordinary Taiwanese.Jiang Zemin also emphasized that political disputes should not interfere with economic cooperation. Regardless of the political situation, the Chinese government has pledged to do its best to

32

protect the legal rights of Taiwanese businessmen.34 Moreover, after the Taiwan Straits Crisisof1996,theStateCouncil’sTaiwan AffairsOffice decided to provide big Taiwanese enterprises with more preferential treatment and expedite the reviewing process.Attracting Taiwan’stop 100 companiesto investon mainland Chinahasbeen linked with “attacking theTaiwan independenceattemptsoftheTaiwanese

government”.35

The ultimate goal of the Chinese government is to continue to attract Taiwaneseinvestment,and to usesuch relationship asleverageto influence Taiwan’s policy-making toward mainland China. The Taiwanese business community in mainland Chinathusbecomesthecoreofmainland China’sunited frontstrategy.

In reality, the Taiwan community has gradually become an integral part of the mainland’slocaldevelopment.In contrastto foreign directinvestmentfrom Japan, US, and other advanced countries, Taiwanese (as well as Hong Kong) business people share the same cultural, ethnic, and linguistic background with host areas. This cultural advantage makes it easier for them to merge with local interests. Since most Taiwanese investment in mainland China has been in labor-intensive industries, 30,000 Taiwanese companies have created millions of job opportunities for locals. Some Taiwanese factories have recruited thousands of employees from various provinces, and serve as centers of manufacturing, recreation, and even education. In other words, Taiwanese investments have not just brought capital and technology to the mainland. They have created asocialnetwork closely connected with theprosperity ofChina’scoastal areas.

33

Lien He Bao, September 11, 1995.

34

Renmin Ribao, August 30, 1996.

35

The Taiwan business community has also developed a relationship of coexistence with local mainland officials. As Taiwanese investment has contributed to local prosperity, and thus enhanced the power of local officials, the latter have offered

necessary services to Taiwanese investors. Local Taiwan Affairs Offices have maintained close ties with individual enterprises, but their relationships are far from confrontational; these offices are well-organized, and report to parallel CCP units. Below the State Council and provincial governments, each county has its own Taiwan Affairs Office, and maintains close horizontal connections with other such offices. Taiwan business people have been reluctant to cooperate with Taiwan Affairs Office officials, but they have not been shy in bringing criticisms to their attention. Most of these criticisms concern the Chinese Customs Service and unreasonable local taxes. Nevertheless, the business community has spent much of its energy to develop good guanxi (relationships) with local officials in order to enable their business to run smoothly. Both local governments and Taiwan businessmen pay only lip service to certain executive orders from the Central Government.Forinstance,the“five-day work week”orderhas not been fully respected by local authorities, as factory workers have requested work on Saturday in order to earn moremoney.Factory ownershaveacceded to “publicopinion”,and localgovernments have not objected to this arrangement.

The Taiwan business community has also organized collective power to protect its rights in mainland China. By the end of 1996, there were forty-three“Taiwan Business Associations”in mainland China.TheDonguan Taiwan BusinessAssociation isan example: in 1993 there were only 360 member companies, but by the end of 1996, it included 1403 members.Themain goalsoftheAssociation areto “protectlegalrights, take care of the living, improve the investment environment, and maintain the good

image”ofTaiwan businesspeople.36

Leaders of local Taiwan Business Associations regularly return to Taiwan and attend seminars organized by the government. During the Taiwan Straits crisis in 1995, they suggested the Taiwan government to restrain itself and open up direct trade, postal, and communication links with mainland China.37 In addition, during an annual trip to mainland China,Taiwan’sChineseNationalFederation of Industries (CNFI) submitted a proposal to Jiang Zemin which suggested that the mainland should postpone political controversies and protect the legal rights of Taiwan business people.38

However, the collective bargaining power of the Taiwanese business community should not be exaggerated. The operation of the Taiwanese Business Associations are closely supervised by localTaiwan AffairsOffices,which always“recommend”deputy directors as their representatives. Furthermore, forming a nation-wide Association of Taiwanese Business has also been blocked by the Chinese central government, which intends to develop the Association as an intermediary to control the Taiwan business community. Horizontal linkage among these associations and any attempt to form a pressure group to challenge the central authorities are not allowed.

Anotherfactorwhich may affectTaiwan businesspeople’sbargaining poweris competition from advanced countries’multi-national corporations. The decrease of competitiveness of Taiwan firms as compared to MNCs has been associated with the adjustmentofmainland China’sforeign tradepolicies.In mid-1996, mainland China decided to reduce tariffs from an average of 35.9 percent to 22 percent. At the same time,

36

An interview with Mr. Hong-teng Yeh , President of the Dongguan Taiwan Business Association, on December 5, 1996.

37

China also canceled some preferential treatment to foreign enterprises such as export tax deductions and tax-free import of equipment. Among the tariff reduction items, mineral, chemical and textile materials enjoyed a reduction of 45 percent, as well as some high-tech products such as integrated circuit and computer key parts. These are the items which American and Japanese multi-national corporations export to China; hence, they have enjoyed the largest benefit. In contrast, the major Taiwanese exports to China are mechanical instruments, plastic products, and other intermediate products. These items enjoy lessbenefitsunderChina’stariffreductions.39

Since the majority ofTaiwan’s exportsto ChinasupportTaiwanesecompanies’investments,theoperating costsofthese companies are relatively higher compared to other advanced countries.

Mainland China’spolicy ofattracting foreign directinvestmentisalso in transition. Since1994,China’spolicy ofattracting foreign directinvestmenthasgradually shifted from being “location oriented”to “industry oriented”.Preferentialtreatmentssolely for coastal special economic zones (SEZs) are gradually being replaced by other policies which boost strategic industries such as infrastructure, bio-chemicals, and advanced electronics. Labor intensive industries are no longer mainland favorites. Service sectors such as banking, trading, and insurance which Euro-American and Japanese companies specialize in are especially welcomed.

These new policies have placed Taiwanese firms conducting labor-intensive manufacturing industries under great pressure from MNCs. In other words, Taiwanese enterprises have to compete with MNCs in areas which Taiwan does not have obvious comparativeadvantages.TakeShanghai,forexample:afterDeng Xiaoping’s“southern

38

tour”in 1992,Shanghaifinally regained itsposition asthe“locomotive”forthe mainland’seconomicdevelopment.Shanghai’sdevelopment strategy also reflects China’sambition ofattracting morehigh-tech industries and service sectors in preparing for the next century. MNCs invest in Shanghai in order to enter the huge domestic market and utilize high-quality human resources. However, in Shanghai, Taiwanese investments are relatively small. According to statistics, in June 1996, Taiwan was the sixth largest investor in Shanghai, next to Hong Kong, Japan, the US, Great Britain and Singapore. Taiwan’sinvestmentamountconsisted ofonly 4.85 percentofShanghai’stotalforeign direct investment. In the national sphere, Taiwan ranks number two, next only to Hong Kong in the investment value.40 In Shanghai’s domestic market, Taiwanese firms find it difficult to compete with the large-scale marketing campaigns from MNCs such as Coca Cola and Sony.

Instead of competing with MNCs, some Taiwanese enterprises have begun to form “strategicalliances”with foreignfirms to develop the mainland market. These joint venturesfocuson themainland’sdomesticmarket,ratherthan utilizing mainland China as a base for processing export goods.41 MNCs provide capital and technology to the joint venture, and the Taiwanese partners use their cultural and language advantages to

establish manufacturing centers and market networks. A recent case is the alliance

between Taiwan’sMitacGroup and IBM.Afterbuying aunprofitablemainland computer company, Mitac sought an alliance with IBM to make and sell personal computers in

39

Zili Zaobao, April 22, 1996.

40

Gongshang Shibao, August 19, 1996.

41

Fongshuo Yang,“Taishang qiye yun yong guoji tseluei lianmeng qianjin dalu shichang zhi fenxi”(An Analysis of Taiwanese Strategic Alliances in the Mainland Market), Jingji qingshi ji pinglun (Economic Situation and Analysis), November, 1996, p. 62.

mainland China. IBM provides advanced technologies and key parts to Mitac, and its brand name is also a powerful vehicle to boost domestic sales. Through this strategic alliance, IBM products have entered the mainland market, and Mitac has gained more protection of its investment in mainland China. This trend of international strategic alliances is on the rise, as some MNCs have established the so-called “GreaterChina Center”in eitherHong Kong orTaiwan,and sought partners to invest in mainland China.

Conclusion: State Versus Market in Cross-Strait Economic Relations

International-oriented firmshavebeen amajorchallengeto Taiwan’sconstraining economic policies toward mainland China, as regulative policies do not have substantial binding effects on these firms. For Taiwanese enterprises in mainland China, what really counts is the attitude of local mainland officials, the local investment environment, and macro-economicpolicies.Taiwan’sregulativepolices may influence the political risk assessment of large enterprises in the short term, but they may also open new rounds of state-business bargaining for more liberal policies in the medium and long run. National security isTaipei’smain concern,butTaiwan’sactivebusinesscommunity hasblurred the line between economic and political concerns.

In contrast to the success of state intervention in promoting export-oriented growth in the60sand 70s,Taiwan’scross-Straiteconomic policy isin facta“marketconstraint” policy. This policy aims at reversing market mechanisms and the international trend of developing theemerging mainland Chinamarket.Compared to the“market

augmentation”policy in theeconomictake-off period of 60s and 70s, this market policy needs even closer cooperation from the business community. However, as the preceding analysis shows, the internationalization of market and enterprise operations has made it

more difficult for the state to control capital flows and investment activities. It is the international market, not the incompetence of the state, that has created the gap between governmental policies and investment behavior.

Thus, the state must replace its negative policies with more positive ones in order to adjust to the trend of internationalization. The best way to fight the challenge is to become more international; if the state helps Taiwanese firms to enhance their

competitiveness in the international capital market and operate their businesses through various strategic alliances with international firms, Taiwan will not have to worry about possible mainland economic sanctions. As internationalization deepens, sanctioning Taiwanese firms would mean sanctioning all related parties in the world. This

internationalization strategy would therefore increase economic efficiency and national security at the same time.

Currently two major polices are being carried out by the Taiwan government to expedite the speed of internationalization. The first is to increase domestic investment on high-tech industries.Thisisbased on thehopethatTaiwan can createa“verticaldivision oflabor”in internationalization,and thuskeep capital-intensive industries and R & D sectors on domestic soil. If this is realized, Taiwan does not need to worry about the “hollowing out”effectofmanufacturing industries.Moving outoflabor-intensive industries to mainland China and Southeast Asian countries will be a natural trend under the framework of the vertical division of labor. The second attempt of internationalization would beto build Taiwan asan “Asia-PacificRegionalOperationsCenter(APROC)”; that is, to establish Taiwan as a specialized regional center for manufacturing, sea and air transportation, financial services, telecommunications, and media enterprises. To implement this plan, thousands of economic regulations need to be revised, the

infrastructuremustbeimproved,and “threelinks” with mainland Chinamustberealized. Hence, the APROC plan is playing the role of catalyst to promote internationalization. Both industrial upgrading and the APROC require strong governmental support and state intervention. This kind of intervention is a more positive way to introduce international factorsto enhanceTaiwan’sinternationaleconomiccompetitiveness.

The ascendance of the business community in cross-Strait relations also poses a majorchallengeto therealistperspectiveofeconomicstatecraft.Although the“spill-over effect”ofeconomicinteraction in solving politicaldisputesshould not be exaggerated, the Taiwan business community has utilized its economic resources to develop strategies of survival as cross-Strait relations has encountered difficulties. Equipped with skills in international marketing and financial management, Taiwanese firms have gained

bargaining power with both sides of the Taiwan Straits. Solving economic issues, such as improving the investment environment and protecting business interests, may serve as a bridge to open new rounds of direct talks between Taiwan and mainland China.

Compared to foreign MNCs, Taiwanese firms have a better chance to penetrate into the local socio-economicnetwork,and then becomean integralpartofChina’seconomic development. If this scenario materializes, cutting Taiwanese investment would mean a haltto themainland’scontinuousdomesticdevelopment.From amorepositive perspective, since the state will be unable to reverse market forces, it should go along with them and improve efficiency and further develop the mainland market. After a careful calculation of the international economic situation and the importance of

mainland projectsin Taiwan’sglobalinvestmentstrategies,investing in mainland China could providemore,ratherthan less,ofaguaranteeforTaiwan’snational security.

Year ValuesofTaiwan’sExportsto Mainland China

Shares of Exports to Mainland Chinain Taiwan’sTotalExports

1987 $1,226.50 2.28 1988 $2,242.20 3.70 1989 $3,331.90 5.03 1990 $4,394.60 6.54 1991 $7,493.50 9.84 1992 $10,547.60 12.95 1993 $13,993.10 16.47 1994 $16,022.50 17.22 1995 $19,433.80 17.40 1996 $20,727.30 17.87 1997 $22,460.30 18.39

Sources: Liangan Jingji Tongji Yuebao (Monthly Report of Cross-Straits Economic

Statistics), Taipei, Mainland Affairs Council, February 1997, P.24 & 26; Jin Chukou Tongji Yuebao ( Monthly Statistics of Exports and Imports , Taiwan Area, R.O.C.), Taipei,

Ministry of Finance, February 28, 1998, p. 10.

Table 1 Ta

i

wan’

s

Ec

onomi

c

De

pe

nde

nce

on

Mai

nl

and

Chi

na

Units: Percentage U.S. millions

Year Taiwan’sTrade Surplus with Mainland China Taiwan’s International Trade Surplus Percentage 1990 $3,629.20 $12,495.20 29.04% 1991 $6,367.60 $13,299.10 47.88% 1992 $9,428.60 $9,479.30 99.47% 1993 $12,889.50 $7,869.80 $163.78% 1994 $14,163.80 $7,697.20 $184.01% 1995 $16,342.40 $8,116.30 $201.35% 1996 $17,667.50 $14,704.40 $120.35% 1997 $18,540.00 $7,672.30 $241.65%

Sources: Liangan Jingji Tongji Yuebao (Monthly Report of Cross-Straits Economic

Statistics), Taipei, Mainland Affairs Council, February, 1997, P.25; Jin Chukou Tongji

Yuebao ( Monthly Statistics of Exports and Imports , Taiwan Area, R.O.C.), Taipei,

Ministry of Finance, February 28, 1998, p. 10.

Table 2

Tai

wan’

s

Tr

ade

Surpl

us

wi

t

h

Mai

nl

and

China in Its Total Trade Surplus

Approved by Taiwan Approved by Mainland China

Year

No. of Projects Amount No. of

Projects Amount 1991 237 $174.16 3,377 $2,710.00 1992 264 $246.99 6,430 $5,543.00 1993 9,329 $3,168.41 10,948 $9,965.00 1994 934 $962.21 6,247 $5,395.00 1995 490 1,092.71 4,778 $5,777.00 1996 383 $1,229.24 3,200 $7,100.00 1997 728 $1,610.00

---Source: Liangan Jingji Tongji Yuebao (Monthly Report of Cross-Straits Economic

Statistics), Taipei, Mainland Affairs Council, February, 1997, P.28; Mainland Affairs

Council Data, February 28, 1998.