The International Joumal of Conflict Management Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 57-76

THE EFFECTS OF PERCEIVED IDENTITY AND

JUSTICE EXPERIENCES WITH AN

ADR INSTITUTION ON MANAGERS'

DECISION PREFERENCES

Shu-Cheng Chi

Hwa-Hwa Tsai

Ming-Hong Tsai

National Taiwan UniversityThis study samples 78 business decision-makers whose cases were part of an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) process, i.e.. the Public Construction Commission (PCC). which operates under the government in Taiwan, between 1997 and early 2000. The authors propose an interaction between two variations of trust—category-based trust and experience-based trust—and hypothesize that decision-makers' per-ceived identity with new versus old government ideology and past justice experiences (with the PCC) would jointly affect their decision prefer-ences. The results partially support these hypotheses. The authors emphasize the critic role of trustworthiness of the third-party ADR providers. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of the find-ings.

Keywords: third party, social identity theory, group-value model, trust Having a trusted third party is vital to the success of the mediation or arbitra-tion of disputes {Wall, 1981;Bazerman&Farber. 1985; Karambayya & Brett, 1989). However, very few studies have examined in detail the source of disputants' trust in their third-party ("TP") mediators and arbitrators. Though several trust models have been proposed in recent hterature (e.g., Shapiro, Sheppard, & Cheraskin, 1992; Lewicki & Bunker, 1996), little is known about how different sources of trust jointly

Note: We gratefully acknowledge the advice and recommetidations of Editor Judi McLean Parks and the three anonymous reviewers. We also would like to thank Raymond Friedman and Jeanne Brett for their valuable comments on earlier versions. And we thank Katie Shonk and Julie Waxgiser for their editorial assistance. This research was partially supported by a grant from the National Science Council in Taiwan (NSC 91 -2416-H-002-015-SSS) to the first author. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Shu-Cheng Chi, Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University, No. I, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei, Taiwan. (nl36@mba.ntu.edu.tw)

affect disputants' views of the trustee. An investigation of such effects will develop theory that enhances our understanding of the construct of trust. In this study, we examine the willingness of disputants in particular cases to re-use an ADR (i.e., alternative dispute resolution) procedure based on their past experiences.

Will disputants' "category-based trust" in a TP system moderate the relation-ship of "experience-based trust" (defmitions below) with their decision preferences? Our study considers this question in a unique environment. We tie our study con-text—^historic shifts in the Taiwanese govemment^to the perceptual frames of the disputants in relation to a governmental ADR system. In addition, we treat the sub-jects' past experiences under the old government {i.e., trust in procedure) and their identity with old and new government ideologies as two separate variables. We propose an interaction between experience and identity. Our theoretical arguments link Lind and Tyler's (1988; Tyler & Lind, 1992) group-value model with self-categorization (Hastorf & Cantril, 1954) and social identity theory (Tajfel & Tumer, 1985), as well as with procedural and distributive justice. This exploration seeks to reduce confusion in the literature regarding the group-value model and relationships between justice, identity, and trust.

We predict that a disputant's willingness to re-use an ADR institution will be strongly influenced by his or her past experiences with the old government and identification with the new government. Our study demonstrates an increasingly fragile trust among members of society. Many scholars suggest that we have entered an era of "networked" organizations (e.g.. Miles & Creed, 1995), in which tempo-rary relationships are increasingly common. Kramer and his associates (Kramer, 1996; Meyerson, Weick, & Kramer, 1996) use the term "swift trust" to depict the vulnerability, uncertainty, and risk inherent in contemporary relationships between individuals and between individual and social institutions. As we will see later, the micro-level personal experiences and macro-level national events present in media-tion and arbitramedia-tion could influence levels of disputants' trust in the ADR institumedia-tion and affect their behavior.

Literature Review

In general, conflicts resulting from contracts can be resolved either in court or

through ADR (Alford & Kaufman, 1999). ADR practices such as arbitration and mediation have proved to be economical and timesaving alternatives to litigation. With the aid of a third party (TP), conflicting parties can negotiate and reach a final resolution. In arbitration, both parties provide evidence to a neutral TP, who makes a final decision. While mediation does allow the parties a chance to express their posi-tions, it does not result in binding decisions. Mediation and arbitration both offer high "process control," as parties have the chance to influence the TP's judgments (Thibaut & Walker, 1975). In advisory arbitration, the TP suggests a decision, but it is not binding (see Zack, 1997, forapracticalreviewof various types of arbitration). Disputants in mediation and advisory arbitration have high "decision control," as they may refuse to accept the settlement proposed by the TP.

S.-C. CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 59

Defining Trust in a TP Context

Disputants seeking solutions via ADR must have some level of trust in the system (Ross & LaCroix, 1996). In this study, we are concemed with defining the antecedents of disputants' trust in a TP institution. "Trust is a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another," write Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, and Camerer (1998, p. 395). Tyler and Degoey (1996) found that a person's willingness to accept the decision of an authority depended upon the authority's trustworthiness, and upon "feelings that an authority made a good-faith effort and treated the parties involved in the conflict fairly" (p. 335). Because ADR involves at least two disputants, each party's trust in the system depends upon how fairly the system treats both sides. Hence, we define a disputant's trust in a TP system as his or her positive expectations of the fairness from the TP system with the acceptance of vulnerability.

We wish to link disputants' trust with their future decision preferences. Kramer (1999) summarized two major models of trust: rational choice and relational. Rational choice theorists (e.g., March, 1994) presume that individuals will maximize expected gains and minimize expected losses in transactions. Hence, a rational model of trust assumes one party's sophisticated understanding of the other party's interests (Hardin, 1998). Lewicki and Bunker (1996) use the term "calculus-based trust " to denote "an ongoing, market-oriented, economic calculation whose value is derived by determining the outcomes resulting from creating and sustaining the relationship relative to the costs of maintaining or severing it" (p. 120). They describe deterrence (i.e., threat of punishment) as a dominant motivator; trust is calculated according to the "adequacy and costs of deterrence" (p. 120). In Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies' (1998) words, trust occurs when "one party has reason to be highly confident in another in certain respects, but also has reason to be strongly wary and suspicious in other respects" (p. 447). While the rational model of trust has been proven enormously useful from a normative and prescriptive standpoint, many of its assumptions are empirically untenable. For instance, the mode! assumes that decision-makers' internally consistent value systems or decisions about trust are consciously calculated. The mode! is too narrowly cognitive to apply to affective and socially influenced trust-related decisions.

We adopt relational models of trust for two reasons. First, we do not aim to investigate the factors that may predict disputants' decision tendencies and the consistency or rationality of their decisions. On the contrary, we believe that there should be no "fear of punishment" for disputants if trust is violated. Second, we do not believe that the rational model of trust adequately describes typical dispu-tant-ADR interactions, which may be limited in duration yet significant.

The relational model conceptualizes trust as a social orientation toward others and toward society, and views trust as socially rather than instrumentally motivated. Extending the literature to the relational aspects of mediation and arbitration, we contend that disputants' trust in a TP system is closely related to social contexts. First, a disputant's affiliation with various groups is a critical source of his or her social information processing (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Consequently, social considerations affect managers' decision preferences. Second, disputants' justice

concerns may be highly contingent upon their social contexts. Chi and Lo (2003) found that a person's pre-existing relationships with a punished co-worker and supe-rior jointly affected his or her perceptions of the punishment event. Finally, Taiwan, the site of our study, is considered a collectivistic society (Hofstede, 1980). Most Taiwanese are Chinese descendants who care a great deal about interpersonal guanxis—dyadic relationships based implicitly on mutual interest and benefit (Hwang, 1987). Therefore, the social context of the TP system provides us with clues to managers' decision preferences.

This study explores an interaction between two types of trust found in the TP system: category-based trust and experience-based trust. With regard to the former, we examine how disputants' perceived identity with a TP system (a social category variable) affects their decision preferences. We follow Kramer's (1999) definition of "category-based trust": "trust predicated on information regarding a trustee's membership in a social or organizational category-information which, when salient, often unknowingly influences others' judgments about their trustworthiness" (p. 577). As Brewer (1981) suggests, a person's membership in a salient social category provides a basis for trust by attributing positive characteristics such as honesty and trustworthiness to the other party. Moreover, a person is likely to "empathize strongly with the other and incorporate parts of his or her psyche into their own 'identity' . . . as a collective identity develops" (Lewicki & Bunker, 1996, p. 123).

Trust has often been assumed to be based on past experience between the "trus-tor" and the "trustee." Studies in organizational justice have shown that members' various experiences relate to their commitment to an organization, and thereby to their trust in the organization (Greenberg, 1990). Furthermore, regular communica-tion with a particular party may provide a person with valuable prediccommunica-tions about the other side's behavior; such predictability enhances trust (Shapiro et al., 1992). Kramer (1999) used the term "history-based trust" to depict individual expectations about the other party's trustworthy behavior based upon their "interactional histo-ries." We use the term "experience-based trust" to denote a person's interactional histories with a TP system, and define it as tmst predicated on fairness-related information regarding a disputant's past interactions with the TP system which, when salient, oflen unknowingly influences his or her judgments about the system's tj-ustworthiness. Past experiences provide disputants with valuable information for assessing the TP system's intentions, motives, and trustworthiness.

Disputants' trust in a TP system is closely associated with context. In this study, we investigate the effects of disputants' identification with the government under which the ADR institution operates as well as the effects of their past experiences on future decision preferences. To date, studies have rarely discussed the bases of disputants' trust in institutional providers of ADR. As Friedman (1993) pointed out, individuals' trust in an institution is crucial to creating stable, contractual relation-ships. The credibility of an ADR is, therefore, the key factor in disputants' choices. Identity and Disputants* Trust in TP Systems

Social identity theorists propose that a person's sense of himself or herself exerts a significant effect on his or her perceptions, attitudes and behaviors (Hastorf & Cantril, 1954; Tajfel & Tumer, 1985; Brewer, 1991; Phinney, 1996). When a

S.-C. CHI. H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 61

person defines himself or herself as a member of a group, he or she tends to become prejudiced and discriminatory toward people in the out-group (Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993; Friedman & Davidson, 1999) and to exhibit in-group favoritism (Messick, 1998). Crocker, Luhtanen, Broadnax, and Blaine (1999) found that African-Americans were more willing than Caucasians to believe that the U.S. government was involved in a conspiracy against African-Americans that resulted in unjust treatment and problems in their community. In a simulated negotiation study, Conlon and Ross (1993) found that a disputant's "negative third-party affiliation"^a preexisting negative relationship between the disputant and a third party—reduced the disputant's outcome expectations; however, the third party's settlement suggestions could compensate for the disputants' reservations.

We thus posit that those who perceive themselves as having the same identity (or perceived category membership) as the TP institution body would have a high level of trust in the system and high expectations for it, relative to those who per-ceive themselves as having a separate identity from the system. As argued by Beyer (1981), ideology is fundamental in organizational dec is ion-ma king. Perceived identity that dwells upon a same or different ideology is likely to have a significant impact on decision-makers' preferences. Thus, in the context of this study, those who perceive themselves as having the "same ideology" as the TP institution (i.e., an in-group perception) would have high expectations of it. By contrast, those who perceive themselves as having a "different ideology" from the TP institution (i.e., an out-group perception) would have low expectations of it.

Lind and Tyler's (1988; Tyler & Lind, 1992) group-value model suggests that individuals' justice perceptions are founded upon their feelings of self-worth and their belief that the group they belong to is functioning properly. According to this view, people desire to understand an authority's stable, underlying motivations in order to predict the authority's future behavior. Based upon the group-value model, a person's past justice experiences serve as an important basis for his or her trust in an authority. Past justice experiences with an ADR institution affect disputants' trust in the system. If disputants have experienced favorable outcomes and procedures, they will have a high level of trust in the ADR institution; if they have not, trust will be low. In this study, disputants had experiences with the "old" ADR institution, but none with the "new" institution at the time data was collected. We expected past experiences with the old system to interact with category membership with both the old and new systems, together predicting the disputants' decision preferences. Our theoretical arguments are explained below.

If disputants do not identify with the ADR institution that caused poor experi-ences, they should not perceive a loss of trust in the institution. Poor experiences that have come from an ADR institution with which one identifies, however, would severely undermine disputants' trust. Empirical evidence has shown an interaction effect between a person's experiences of outcome justice and procedural justice. Brockner, Siegel, Daly, Tyler, and Martin (1997) found that employees' trust in organizational authorities was strongly related to their support for the authori-ties^—especially when they associated unfavorable outcomes with authorities' deci-sions. Ehlen, Magner, and Welker (1999) also found an effect between outcome favorability and procedural fairness on subjects' feelings of resentment.

Furthermore, recent studies have shown that individuals' experiences with injustice from an trusted party trigger negative emotions and a sense of betrayal. Koehler and Gershoff (2003) found that subjects reacted to and punished betrayals more severely than similar crimes. Robinson (1996) attributes employees' reactions to trust violation to fundamental beliefs about respect, codes of conduct, and relationships (cf. Rousseau, 1989). Robinson found that employees perceived inconsistencies between an employer's words and actions as "broken promises," which resulted in a decline in err^loyee motivation.

Thus, we posit that identity with the same ideology may interact with justice experiences, and that the two will jointly affect a person's trust in an authority. Owing to an erosion of perceived fairness, those who strongly identify with the ADR institution when perceiving unjust experiences would have lower trust in the ADR institution than would those with a weak identity.

We also propose that the more one identifies with the current ADR institution, the more trust and positive expectations one will have in the institution. Will such expectations mitigate the negative carry-over effects of past unpleasant injustice experiences? This underlying question echoes the fundamental debate between behavioralism and modem cognitive theories. According to Skinner (1953), a per-son's behavior is a function of his or her past experiences. Positive experiences lead to a more frequent behavior recurrence, while negative experiences reduce its fre-quency. By contrast, Lewin (1951) proposes an "ahistorical" explanation of human behavior: "The choices made by a person in a given situation are explained in terms ofhismotivesandcognitionsatthe time he makes the choice" (cited in Vroom, 1964, p. 14). Based on the latter argument, an individual's expectations of the current ADR system will affect his or her decision preferences more than past experiences will. Following this logic, when a disputant strongly identifies with the current system and thereby has high expectations of it, the effects of past experiences on future preferences will be largely reduced.

Let us reframe these arguments in the context of trust. Williams (2001) argues that a person's perceived social category provides an affective context for trust development. A person's strong identity with an ADR system triggers his or her high expectations of it and affection toward it (cf., Conlon & Ross, 1993). But why would strong-identity disputants disregard or even "forgive" earlier poor experiences with the system? Studies of close relationships have demonstrated the importance of com-mitment in motivating forgiveness (e.g., Finkel, Rusbult, Kumashiro, & Hannon, 2002). Finkel et al. (2002) found that the commitment-forgiveness association rests on individuals' intent to persist in relationships. Committed individuals exert effort without counting what they receive in return or calculating whether their invest-ments will be reciprocated. Therefore, we propose that identification with the ADR institution would enhance a person's willingness to forgive past poor experiences with it.

Again we propose that individual identification with an institution that shares a similar ideology may interact with justice experiences to jointly affect a person's trust in an authority. But, owing to an intention to repair of damaged trust with the ADR institution, those who strongly identify with the institution when perceiving

S.-C. CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 63

unjust experiences would have a higher level of trust in the "new" institution than would those with a weak identity with the institution.

Study Context and the Proposed Hypotheses

The context of this study is a governmental dispute-resolution agency in Tai-wan called the Public Construction Commission under the government of Republic of China, simplified as "PCC." One of the purposes of the PCC is to provide an ADR between the private sector (e.g., construction companies) and the government (including central and local government and all other institutions in the public sec-tors, such as public schools). When a company perceives that its rights have been violated, it can file a case against the government with the PCC. The PCC then appoints a committee member to determine whether the appeal will be accepted for review. Next, the involved disputants are allowed to state their positions to the appointed committee. After reviewing the case, the committee makes a final deci-sion. The PCC's decision is not legally binding. An appeal to a court or to private arbitrators is allowed if the company is not satisfied with the results. Hence, although we use the term "mediation," the PCC's procedure is conceptually similar to advisory arbitration in the United States.

Because we aim to explore sources of disputants' trust in an ADR institution, we surveyed disputants with real experiences with ADR procedures to judge the fairness of its process and outcomes. The study context allows us to explore the interaction effects of disputants' perceived identity with the TP provider of ADR (i.e., the PCC) and of their past justice experiences.

This study investigates cases completed by the PCC between 1997 and early 2000. The sampled time period was late 2000. Six months prior, the "old" govern-ment of the KMT (the party of Kuo-Ming-Tang) had stepped down. For the first time in the 50-year history of the Republic of China in Taiwan, the government fell under the DPP, the Democratic Progressive Party. This change in government took place after our respondents had interacted with the PCC under the "old" government; we sent out our surveys after the "new" government had been established. The survey allows a comparison of the social-identity measxire of trust between the old and new government. Owing to such a dramatic change, we expected people to hold diverse views of the two governments, leading to a wide variance of their collective self-identities.

Heated debates between "Taiwanese as Taiwanese" vs. "Taiwanese as Chi-nese" identity among political parties in Taiwan have transformed ROC citizens' political choices into an ethnic issue. Consequently, our discussions of trust in the two governments may be translated into collective self-identity, Someone with a high level of trust in the new DPP government is likely to have a strong Taiwanese identification, while someone with a high level of trust in the former KMT govern-ment could be seen as having a Chinese identification. Notably, Huang, Liu, and Chang (in press) propose a culture-specific "theory of dual identity," which claims that people in Taiwan have both a Chinese and Taiwanese identity. Huang et al. argue that when Chinese and Taiwanese identities are activated in a political context, they interact in an antagonistic manner, and that when they are made salient in a cultural context, they are more compatible. In a sample of 828 university students.

Huang et al. found that one's identification as either Taiwanese or Chinese affected evaluations of leaders that followed pattems of in-group favoritism. The two identities were mutually compatible regarding cultural issues, but incompatible regarding politicized allocation decisions and language. (Huang et al., however, admit that it is difficult to draw a clean dividing line between political and cultural domains.)

Drawing upon these arguments, we suggest that disputants' trust in the govern-ment of a particular political party implies either a Taiwanese or Chinese self-identity. A person with a high level of trust in the KMT government will have a strong Chinese identity, while a person with a high level of trust in the DPP government will have a strong Taiwanese identity. Parallel to Huang et al.'s dual-identity hypothesis, we do not assume a bi-polar continuum of party identification, but posit that disputants put their trust in both governments or in nei-ther one. Hoping to maintain strong business relationships with any government, most will not want to identify themselves exclusively with one political party. Consequently, it is likely that some disputants will identify with the ideologies of both the old and new governments. It remains an empirical question as to which identity exerts a stronger impact.

We propose that if perceived identity with the old ADR system is weak (as in the case of perceived weak identity with old government ideology), then past experi-ences will not play a significant role in future decision preferexperi-ences. If, on the con-trary, perceived identity is strong, then past negative experiences do matter. We speculate that a disputant's perceived strong identity with the old government's ideology, despite recognition of unfair treatment by that government, would lead to even stronger resentment toward the ADR agency. In other words, a person's dis-trust in the TP system, whether caused by the process or by its outcomes, will be reinforced when he or she identifies highly with the old government (Brockner et al., 1997; Ehlen et al., 1999). Such joint effects would elevate the person's sense of betrayal, resulting in negative feelings towards the TP system.

Consequently, if disputants did not strongly identify with an ADR system that caused poor experiences, they should not experience feelings of trust violation. Poor experiences with the ADR system, however, would be incongruent with a strong identity with the old system. We propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived identity with old government ideology interacts with justice experiences with third-party dispute systems, jointly affecting disputants' future decision preferences. Rela-tive to disputants with a weak identity with old government ideology, disputants with a strong identity have stronger posi-tive relationships between justice experiences and decision preferences.

We also propose that identity with the ideology of the new government miti-gates the relationship between past experiences and decision preferences. Failing to receive a favorable result (either in terms of process or outcome) might lead to disap-pointment and dissatisfaction with the system. But the more one identifies with the new government ideology, the more he or she would forgive the "wrongdoings" of

S.-C, CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 65

the system (cf. Finkel et al., 2002). As shown by Colon and Ross's (1993) study, since disputants have had no experience with the new government, in-group mem-bers would have high expectations of the PCC. Thus, the more one identifies with new government ideology, the more Hkely he or she will be to disregard bad past experiences and use the new system in the future.

On the other hand, when identity with new government ideology is low, justice experiences might have more of an effect on decision preferences. Hence, these disputants should be less willing to disregard the experiences, leading to a stronger relationship between justice experiences and decision preferences. We thus propose: Hypothesis 2: In the current third-party dispute system, perceived identity interacts with justice experiences, jointly affecting managers' futuje decisions and preferences. Relative to disputants with a weak identity with new government ideology, disputants who identify strongly with new government ideology have weaker positive relationships between justice experiences and deci-sion preferences.

Method

To test our hypotheses, we sampled dispute-resolution cases completed by the PCC under the old government (between 1997 and early 2000). Two disputing par-ties, a government agency and a private company, were involved in each case. We disregarded the government agencies in our sample set, as they were not the focus of the study. We sent 175 questionnaires to the company presidents, senior managers, or managers in charge of the dispute resolution cases. A total of 78 questionnaires were returned by 36 presidents, 24 top managers, and 18 middle managers. More than half of the companies had participated in government contracts for more than 11 years.

Measures

We designed the following scales and assessment items: a Procedural Justice Scale, a Distributive Justice Scale, an Identity with Government Ideology Scale, a Decision Preference Scale, a Time and Cost Scale, one item for Possibility for Future Contracts with Government, and one item for Percentage of Contracts with Government (see Appendix for the questionnaire items). The first three scales measure independent and dependent variables, while the rest measure control vari-ables. The first five scales were measured on a Likert 6-point scale, with " 1 " indicat-ing "strongly disagree" and "6" indicatindicat-ing "strongly agree." Possibility for Future Contracts with Government and Percentage of Contracts with Government were also measured on a Likert 6-point scale, with the former ranging from "extremely likely"

to "extremely unlikely" and the latter ranging from "below 10 percent" to "above 90

percent." Rank officers in the PCC read through the questionnaire to assure its flu-ency and adequacy.

Control Variables. As control variables for the dependent variable (a

respon-dent's decision preference), we used the time and cost of the case under the PCC, the possibility of future government contracts for the focal company, and the percentage The InternationalJournal of Conflict Management, MoX. 15, No. 1

of the company's government contracts in proportion to overall sales in the previous five years. (The higher the scores, the more economical, less costly, and more likely the company's future contracts with the PCC would be.) We used time and cost because these variables influence disputants' choice of ADR. Because most of our sampled firms did a great deal of business with the old government, the data may be skewed. To account for this possibility, we added percentage of government con-tracts as a control variable. A majority of our respondents had frequent business contracts with the government. Finally, a company's future contracts with the government may also affect its use of the PCC, which is a well-known dis-pute-resolution alternative in Taiwan. More than 87 percent of our respondents per-ceived a strong likelihood of engaging in future business contracts with the govern-ment.

Procedural Justice and Distributive Justice Scales. These two scales were adopted and modified from the studies ofTyler and Lind (1992) and their associates. We chose three items for each scale. A sample item for the Procedural Justice Scale was, "The mediators had sufficient professional knowledge in the handling of this dispute." A sample from the Distributive Justice Scale was, "How fair was the out-come you received?" We designed two of three items in the Procedural Justice Scale to relate to the degree of mediators' professional knowledge, thereby putting more emphasis on, in Tyler and Lind's (1992) terms, "trust" than on the "standing" and "neutrality" dimensions of procedural justice. We correlated our version with Tyler and Lind's items via back-translation. The Cronbach alpha was .77 for the Proce-dural Justice Scale and .96 for the Distributive Justice Scale.

Identity with Government Ideology Seale. We designed three items for this scale, both targeting the old and the new governments. For example, one item was, "Do you believe that the old (or new) government usually does what is right?" We averaged three items each to measure respondents' identification with old or new government ideology. Interestingly, we found that the scores for the two subscales were positively correlated (p > .05), which confirmed our earlier argument for two separate identities with government ideology, rather than a single bi-polar identity construct. To be specific, 22 respondents scored above average on both subscales and 16 respondents scored below average. Nineteen respondents scored above average on identity with old government ideology and scored below average on identity with new government ideology (i.e., the "pro-KMTs"), while 7 respondents scored above average on identity with new government ideology and below average on identity with old government ideology (i.e., the "pro-DPPs"). The Cronbach as for the two subscales were .89 and .88, respectively.

Decision Preference Scale. Two questions assessed decision preferences: "Will you file a complaint with the PCC when you have future disputes regarding contracts with government agencies?" and "When someone you know has a dispute with a govenmient agency, will you recommend that s/he go to the PCC to file a complaint?" We averaged the scores for the two items to represent respondents' future preferences for using the PCC as an ADR. The Cronbach a for this two-item scale was .75.

S.-C. CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 67

Results

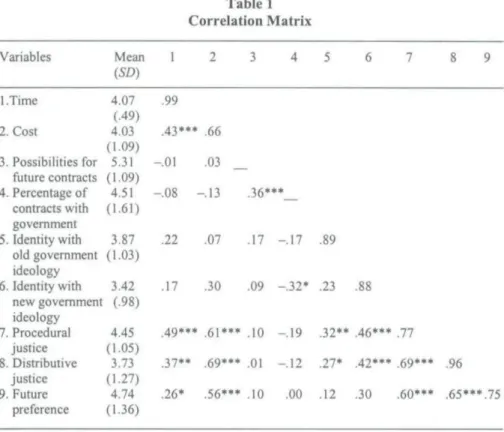

We first conducted a Pearson correlation analysis on our variables (see Table 1). Results indicate that the decision preference indicator was significantly corre-lated to time and cost, procedural justice, and distributive justice {ps < .001 or .05). We also discovered a strong correlation between average scores of procedural justice and distributive justice (r = .69, p < .001). Because the correlation coefficient between the two constructs is below .70, however, we consider the two scales as distinct measurements of each.

Table 1 Correlation Matrix Variables Mean (SD) l.Time 2. Cost .99 4.07 (.49) 4.03 (1.09) 3. Possibilities for 5.31 future contracts (1.09) 4. Percentage of 4.51 -.08 conn-acts with (1.61) government 5. Identity with 3.87 old government (1.03) ideology 6. Identity with 3.42 new govemment (.98) ideology 7. Procedural 4.45 justice (1.05) 8. Distributive 3.73 justice (1-27) 9. Future 4.74 preference (1.36) -.01 .22 .17 66 .03 -.13 .07 .30 .36*** .17 -.17 .89 .09 -.32* .23 49*** .61*** .10 -.19 .32** .46*** .77 .37** .26* .69' .01 -.12 .27* .42' .56*** .10 .00 .12 .30 .69**" .60' .96 .65***.75

. Reliability coefficients are in parentheses along the diagonal. Variable 3,4 each has only one item, thus no Cronbach a scores are reported,

*/j<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001. (two-tailed)

We then conducted a regression analysis. We first ran the regression equation for the control variables, then added four predicting variables: identity with old government ideology, identity with new government ideology, procedural justice, and distributive justice. Finally, we added the four interaction terms between procedural (or distributive) justice and identity with old (or new) govemment ideology. To minimize coUinearity between the main effects of the four predicting variables and the four interaction terms, we mean-centered the four interaction effect The International Journal of Conflict Management, "Vol. 15, No. 1

variables (Aiken & West, 1992). Regression analysis results are depicted in Table 2. Table 2 Regression results Predictor Variable Future Preference

P P

Time CostPossibilities for future contracts

Percentage of contracts with government Identity with old government ideology Identity with new government ideology Procedural justice

Distributive justice Identity with old

government ideology Identity with new

government ideology Identity with old

Government ideology Identity with new

Government ideology .02 .59*** .14 ,05 ,01 .14 .13 .04 .30** .17 .32* .45** Procedural justice Procedural justice Distributive Justice Distributive Justice .02 .12 .24* .02 .38** .33** .33* .39** .28* .05 .05 .33* AdjA^ F AR^ F

4f

N .34 8.25*** 4 57 .57 10.09*** .24 7.69*** 8 57 .63 8.86*** .08 3,01* 12 57 */7<-O5. **p<.Ol. * * V < . 0 0 1 .Cost was a predictor of fiiture decisions (p = .59,p < .001); the less costly PCC was relative to other ADR systems, the higher the preference for it. The other three control variables (time, the possibility for future government contracts, and percentage of govenunent contracts) were not significant (p > .05). Tbe respondents' identity with old government ideology reached a significance level of .01 (p = -.30). (The negative sign means that the more a person identifies with the old govern-ment's ideology, the less likely he or she is to use the PCC when involved in a dis-pute with a government agency or to recommend it to others.) The Beta coefficient of procedural justice reached a significance level of .05 (P = .32) and the Beta coeffi-cient of distributive justice reached a significance level of .01 (p = .45). Thus, the more favorable a person's past justice experiences, the more likely he or she will be to use the PCC or recommend it to others. Lastly, though the Beta coefficient of

S.-C. CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 69

distributive justice (.45) appears to be larger than that of procedural justice (.32), this difference did not reach a .05 significance level. This indicates that the former does not explain greater variance than the latter in predicting willingness to engage in ftiture interactions with the ADR.

Finally, we found significant interaction effects between procedural justice and identity with old government ideology at a level of .01 (3 - .28) and significant interaction effects between distributive justice and identity with new government ideology at a level of .05 (P = -.33). The other two interaction terms did not reach a significance level of .05. The change in R-square by the four interaction terms equaled .08 with a significance level of .05. Hence, our hypothesis was partially supported. Figures 1 and 2 show the directions of the interaction findings.

We interpreted this interaction by examining the regression weights (simple slopes) of past experience at one standard deviation above and one standard devia-tion below the mean for identity with government ideology. We found that perceived procedural justice was significantly related to future decision preferences when identity with old government ideology was strong (P - .74,/? < .01) but not when it was weak (P = -.05, p > .05). Additionally, perceived distributive justice was signifi-cantly related to future decision preferences when identity with new government ideology was weak (p = .93,p< .01) but not when it was strong (p =-.15,/? > .05).

Figure 1

Interaction Effects of Justice Experiences and Identity with Old Government Ideology

6.00 5.50 5.00 4.50 4.00 3.50 • 3.00 -• 2.50 -2.00

1.50

+

1.00 5.28 3.07Identity with old Govemment ideology-Low Identity with old Govemment ideology-High

Procedural Procedural Justice-Low High

In Figure 1, our findings suggest that respondents with a high level of identity with old govemment ideology and low procedural justice would be the least likely to

use the PCC as an ADR or to recommend the PCC to other companies. We did not find the same joint effect with distributive justice. Figure 2 shows that despite a poor past experience with distributive justice, respondents with a high level of identity with new govemment ideology would prefer to use the PCC in future disputes or would recommend it to others. We did not find the same joint effect with procedural justice.

To summarize, our results showed that when people assess a third-party system, their trust in the system comes from two sources: perceived identity with the system and past justice experience. Each provides a disputant with some basis of trust. Those lacking both sources of trust, however, may think more carefiilly about whether to use the ADR in the future.

Discussion

This study examines the social-psychological bases of disputants' trust in a TP system by investigating real-world company decision-makers' preferences for an ADR institution, their subjective evaluations of their "identity" with the institution, and their justice experiences with the institution. Researchers have suggested that, in an era in which relationships within and across organizations are often fleeting, persistent trust in someone is rare, if not impossible.

This study offers theoretical contributions by relating social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1985) to the group-value model (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Lind,1992) in the mediation and arbitration literature. Instead of treating justice as a dependent variable, as was done by the group-value model, we seek to demonstrate how justice experiences may predict a disputant's choice of behavior and a compo-nent of his or her trust in the TP system. Indeed, the disputants' past experiences in our study were critical in their decision-making.

To consider the combined effect of identity and past experience with the ADR system, we introduced social identity theory and built our arguments around the concept of trust. We proposed that a disputant's identity with the system either enhanced the relationship between past experience and future decision preferences or mitigated it. We interpreted the vast differences between these experiences by arguing that identifying with a "new" system wipes out the unpleasant experiences and leads to forgiveness (cf Finkel et al., 2002). By contrast, poor experiences under one system with which a person identifies create a sense of betrayal and high levels of resentment (Robinson, 1996; Koehler & Gershoff, 2003). To enhance our under-standing of the phenomenon in question, we used two versions of trust ("cate-gory-based" and "experience-based") to depict the theoretical underpinning of the role of identity and justice experiences.

A self-interest, or instrumental, model of justice (e.g., Folger & Konovsky, 1989; Niehoff & Moorman, 1993) may also be employed to explain our results. As shown in Figure 1, we found that when disputants' identity with the old govemment ideology was low, procedural justice experience was unrelated to decision prefer-ence. That is, the disputants all were willing to try the new TP. Here, the perceived identity of the TP system acted as a filter for and a magnifier of justice experience (cf Shapiro & Brett, 1993). When disputants detected a shared identity, they were more

S.-C. CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 71

likely to attribute poor experiences to the old govemment. If they did not, then their experiences did not matter.

Figure 2

Interaction Effects of Justice Experiences and Identity with New Government Ideology

6.00 5.50 5.00 4 . 0 0 •• 3.50 3.00 2.50 + 2.00 1.50 1.00 5.28

5.14 •Identity with new

Govemment ideology-Low

Identity with new Govemment ideology-High Distributive Justice-Low Distributive Justice-High

Similarly, as seen in Figure 2, when disputants' identity with the new govem-ment ideology was low, distributive jtistice experience was positively related to decision preference. Again, the perceived identity of the TP system acted as a filter or magnifier. When disputants detected a similar identity, they were optimistic about the govemment. But if they did not, their decision tendencies followed their experi-ences.

Overall, our findings illustrate the critical role of trust in a TP system in affecting managers' preferences for an ADR. Our findings supplement the existing literature on the group-value model and on organizational justice in general. We show that the social contexts in which trust evolves predicate the relationships between perceived justice and human behaviors, a line of research that deserves further exploration.

Limitations, Implications, and Future Directions

Nevertheless, our study has several limitations. First, because we found only two out of foxu- significant interaction terms, we state our findings with caution. Second, we collected only 78 respondents from a sample of all PCC cases. There are a number of different ADRs available in Taiwan, including those provided by pri-vate arbitration associations. As our data represent only a small sample of all ADR disputants in the country, the findings should be cautiously generalized across national/cultural botmdaries. Finally, we questioned people who had had experience with the old govemment but no experience with the new one. As a result, we could only partially test possible interaction effects. An ideal sample would require

respondents with experience with the old or new government, as well as experience with a similar and/or different government ideology. Unfortunately, we were unable to acquire such a full-scale sampling.

The study has a number of practical implications. First, it provides evidence of the importance of credibility of third parties in an ADR system. Based upon our findings, an ADR institution should pay serious attention to its bases of trust. The institution's knowledge of disputants' rationale for trusting {or distrusting) it could suggest intervention strategies. For example, as Kolb (1985) noted, mediators often attempt to shape disputant beliefs early in an intervention. After discovering each side's beliefs, mediators may choose to lower one disputant's expectations while elevating the other side's expectations.

Second, most of otir respondents were either owners or top managers of their companies and some expressed serious concerns of loss of trust in the ADR institu-tion. We recommend that disputants repair damaged trust by actively disregarding negative experiences and recasting the system in a new light (cf Murphy & Han^-ton, 1988). Moreover, we want to caution that unrealistic, high expectations of an ADR institution may bring about even greater disappointment and dissatisfaction. Disputants should recognize their tinderlying biased assumptions and acknowledge when they need to be adjusted.

Finally, TP system providers should view diversity as both a challenge and an opportunity. They must equip themselves with the ability to appreciate and cope with differences in cultural ideologies and past experiences. Often, ADR providers will find themselves confronted with those who had negative past experiences with the system or who fail to identify with the system for some other reason. In such cases, providers need to seek a "superordinate" identity (Huo, Smith, Tyler, & Lind, 1996) for the ADR institution to prevent disputants ft-om forsaking them simply due to an "identity-based" bias. Finally, the institution should work toward establishing a professional image that will override past experiences that could affect managers' decisions about which ADR institution to use.

An understanding of factors correlated with dispute resolution in Taiwan will benefit companies across the globe. This study provides evidence for the importance of identity issues in Chinese societies. Western businesspersons need to understand the factors that affect local managers' perceptions of various dispute resolution channels. Furthermore, our findings are likely to apply to other identity issues, such as gender and education. Expanding this work to a broader set of identity issues would doubtless be a promising avenue for researchers.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1992). Multiple regressions: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alford, H. J., & Kaufman, K. C. (1999). Alternative dispute resolution: What is it. Federation of Insurance <& Corporate Counsel Quarterly, 49, 433-440. Bazerman, M. H., & Farber, H. S. (1985). Analyzing the decision-making processes

of third parties. Sloan Management Review, 27 (1), 39-48.

S.-C. CHI, H.-H. TSAI, AND M.-H. TSAI 73

Beyer, J. M. (1981). Ideologies, values, and decision making in organizations. In P. C. Nystrom & W. H. Starbuck (Eds.), Handbook of organizational design (Vol. 2, pp. 166-202). New York: Oxford University Press.

Brewer, M. B. (1981). Ethnocentrism and its role in interpersonal trust. In M. B. Brewer & B. E. Collins (Eds.), Scientific inquiry and the social sciences (pp. 214-231). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 475-482.

Brockner, J., Siegel, P. A., Daly, J. P., Tyler, T., & Martin, C. (1997). When trust matters: The moderating effect of outcome favorability. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 558-583.

Chi, S. C , & Lo, H. H. (2003). Taiwanese employees' justice perceptions of co-workers' punitive events. Journal of Social Psycholog); 143, 27-42.

Conlon, D. E., & Ross, W. H. (1993). The effects of partisan third parties on negotia-tor behavior and outcome perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology. 78, 280-290.

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R., Broadnax, S., & Blaine, B. E. (1999). Belief in U.S. govemment conspiracies against blacks among black and white college students: Powerlessness or system blame. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25 941-953.

Ehlen, C. R., Magner, N. R.. & Welker, R. B. (1999). Testing the interactive effects of outcome favourability and procedural fairness on member's reactions towards a voluntary professional organization. Journal of Occupational and Organiza-tional Psychology. 72, 147-161.

Finkel, E. J., Rusbult, C. E., Kumashiro, M., & Hannon, P. A. (2002). Dealing with betrayal in close relationships: Does commitment promote forgiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology!. 82, 956-974.

Folger, R., & Konovsky, M. A. (1989). Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Academy of Management Journal 32

115-130.

Friedman, R. A. (1993). Bringing mutual gains bargaining to labor negotiations: The role of trust, understanding, and control. Human Resource Management 32 435^59.

Friedman, R. A., & Davidson, M. N. (1999). The black-white gap in perceptions of discrimination. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 7, 203-228. Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, B. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C.

(1993). Tlie common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of School Psychology. 4, 1-26.

Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16, 399-432.

Hardin, R. (1998). Trust. New York: Russell Sage.

Hastorf, A. H., & Cantril, H. (1954). They saw a game: A case study. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49, 129-134.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Huang, L., Liu, J. H., & Chang, M. (in press). The "double identity" of Taiwanese Chinese: A dilemma of politics and culture rooted in history. Asian Journal of Social Psychology.

Huo, Y. J., Smith, H. J., Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1996). Superordinate identifica-tion, subgroup identificaidentifica-tion, and justice concems: Is separatism the problem; is assimilation the answer? Psychological Science. 7, 40-45.

Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology. 92. 944-974.

Karambayya, R., & Brett, J. M. (1989). Managers handling disputes: third-party roles and perceptions of faimess. Academy of Management Journal. 32, 687-704.

Koehler, J. J., & Gershoff, A. D. (2003). Betrayal aversion: When agents of protec-tion become agents of harm. Organizaprotec-tional Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90,244-261.

Kolb, D. M. (1985). To be a mediator: Expressive tactics in mediation. Journal of Social Issues, 41, 11-26.

Kramer, R. M. (1996). Divergent realities and convergent disappointments in the hierarchic relation: trust and the intuitive auditor at work. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in Organizations (pp. 216-245). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kramer. R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569-698.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. M, Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trusl in organizations (pp.

114-139). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23, 438-458. Lewin, K. (1951). Field theor\> in social science, (edited by Dorwin Cartwright),

New York: Harper.

Lind, E. A.. & Tyler, T. R. (1988) The social psychology of procedural justice.'Htv^

York: Plenum Press.

March, J. G. (1994). A primer on decision making. New York: Free Press.

Messick, D. M. (1998). Social categories and business ethics. Business Ethics

Quarterly. I, 149-172.

Meyerson, D., Weick, K. E., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Swift trust and temporary groups. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp.

166-195). Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

Miles, R. E.. & Creed, W. E. D. (1995). Trust in organizations: A conceptual framework linking organizational forms, managerial philosophies, and the opportunity costs of controls. In R. M. Kramer & T, R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 16-38). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Murphy, J. G., & Hampton, J. (1988). Forgiveness and mercy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Niehoff, B. P.. & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad-emy of Management Journal. 36. 527-556.

S.-C. CHI, H,-H. TSAI. AND M.-H. TSAI 75

Phinney, J. S. (1996). When we talk about American ethnic groups. What do we mean? American Psychologist. 51, 918-927.

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574-599.

Ross, W., & LaCroix, J. (1996). Multiple meanings of trust in negotiation theory and research: A literature review and integrative model. International Journal of Conflict Management. 7,314-360.

Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2, 121-139.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393-404.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224-252. Shapiro, D. L., & Brett, J. M. (1993). Comparing three process underlying

judg-ments of procedural justice: A filed study of mediation and arbitration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1167-1177.

Shapiro, D. L., Sheppard, B. H., & Cheraskin, L. (1992). Business on a handshake. Negotiation Journal, 8, 365-377.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan. Tajfel, H., & Tumer, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior.

In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale. NJ: Eribaum.

Tyler, T. R., & Degoey, P. (1996). Trust in organizational authorities: The influence of motive attributions on willingness to accept decisions. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 331-356). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, 115-191). New York: Academic Press.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

Wall, J. A. (1981). Mediation: An analysis, review, and proposed research. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 25, 157-180.

Williams, M. (2001). In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. Academy of Management Review. 26, 377-396.

Zack, Jr. J. G.. (1997). Resolution of disputes: The next generation. AACE Interna-tional Transactions, 2, 50-54.

Appendix Survey Questionnaire Cost and Time Scale

1. What was the amount of money you spent on PCC mediation compared to other litigation channels, such as court?

2. All things considered, do you think you got your money's worth from filing with the PCC?

3. Was the duration of time you expected to spend with the PCC less than if you had gone through the court system?

4. What was the duration of time you expected to spend with the PCC as compared to the arbitration process?

5. Considering what had to be done, do you think the time it took for your case to get resolved was time-consuming?

Item for Possibilities for Future Contracts

Do you expect that you will be dealing with govemment contracts again in the future? (extremely likely to extremely unlikely)

Item for Percentage for Contracts with Government

1. On average, what is the approximate percentage of your contracts with govemment in proportion to your overall sales in the past five years? (below 10%, 10-30%, 30-50%, 50-70%, 70-90%, above 90%)

Trust in Government Scale

1. Do you believe that the old govemment usually does what is right? 2. Do you believe the new govemment usually does what is right?

3. What do you think of the performance of most old govemment agencies? 4. What do you think of the performance of most new government agencies?

5. Do you respect the political institutions and govemment agencies of the old ROC govem-ment?

6. Do you respect the political institutions and govemment agencies of the new ROC govemment?

Items for Decision Preferences

1. Will you file a complaint with the PCC when you have future disputes regarding contracts with govemment agencies?

2. When someone you know has a dispute with a govemment agency, will you recommend that s/he go to the PCC to file the complaint?

Procedural justice Scale

1. Did the mediator try to be fair to you?

2. The mediators had sufficient legal knowledge in the processing of the dispute. 3. The mediators had sufficient professional knowledge in the handling of this dispute. Distributive justice Scale

1. How fair was the outcome you received?

2. How satisfied were you with the dispute resolution result? 3. Do you agree with the mediation (dispute resolution) result?

Received: April 8, 2004 Accepted after two revisions: January 14, 2004