計畫名稱:我國學生電腦網路沈迷現象與因應策略之研究(總計畫)

計劃編號:NSC89-2520-S-009-008

主 持 人:國立交通大學 教育研究所 周倩

執行期限:89.8.1–90.7.31

Tel: + 886-3-5731808

Fax: + 886-3-5738083

email: cchou@cc.nctu.edu.tw

英文標題:What Makes the Inter net Addictive: Some Tentative Explanations

附 註:This paper was presented in poster session at 109

thAmerican Psychology

Association (APA) Annual Convention, San Francisco, USA. August 26,

2001.

中文摘要

本文之目的是探討為什麼有些網路使用者會沉迷於網路,提出一些可能的解釋。

本文以文獻探討法進行,分為三個向度討論:

(1)網路本身及其內容,

(2)網路

使用者本身,

(3)使用者與使用者之互動。

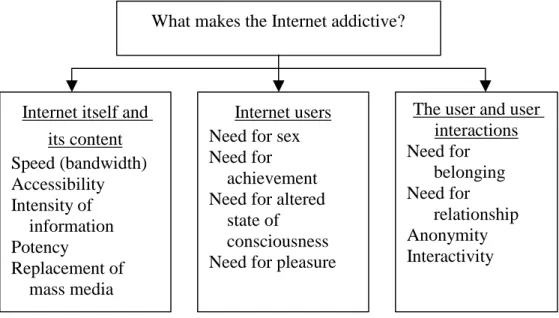

Abstr actThe purposes of this study are to investigate what makes the Internet addictive and provide some tentative explanations. If we consider that some people are addicted to the Internet, then what exactly are they addicted to? Is it the Internet technology in general or particular applications? Is the medium or the message? In order to review and cite relevant literature, the present researcher proposed three angles for the following discussion: (1) the Internet itself including its content, (2) Internet users themselves, and (3) the user and user interactions on the Internet.

Intr oduction

The purposes of this study are to investigate what makes the Internet addictive and provide some tentative explanations. Many researchers, for example, Griffiths (1998, 2000), Young (1998), Chou & Hsiao (2000), have postulated that maladaptive patterns of network use in general and Internet use in particular are forms of addiction. If we assume that some people are addicted to the Internet, to what, exactly, are they addicted? Are users addicted to the technology itself? Are they addicted to particular applications only? Or perhaps to the degree of control and/or anonymity offered by Internet use? It is the medium or the message? Most relevant studies have tried to answer these questions from different perspectives and using different methods or inquiry. This paper offers three categories of relevant literature in order to organize the following discussion; those categories are (1) the Internet itself including its

content, (2) Internet users themselves, and (3) the user and user interactions on the Internet. Of course, while categorizing the literature in this way is useful for purposes of organization and discussion, such a move is reductive in that these categories in fact overlap and interact in complex ways. Figure 1 shows the analysis structure of this paper.

The Inter net Itself and Its Content

Greenfield (1999) states that the unique qualities of the Internet contribute to the potential for Internet addiction— specifically its speed, accessibility, intensity of information accessed online, and the potency (stimulation) of its content. In Chou & Chen’s study (2000), 83 heavy Internet users were interviewed and reported that the Internet features they most appreciated included interactivity, ease of use, availability, and breadth of information accessed online. Interactivity has two aspects: human-computer and interpersonal. Most Internet applications such as the WWW are very easy to use, and thus enhance human-computer interactions; further, some applications, such as chat rooms and email, are especially good at facilitating interpersonal interactions. Availability means easy, low-cost access for users. Abundant and rapidly updated information is another major feature that attracts users to participate online. The diversity of ideas, subjects, attitudes, and opinions presented on the Internet continuously changes users’ perspectives.

Indeed, the popularity of the Internet is definitely in ascendancy. In addition to ease of access and low cost, the Internet’s continuously expanding bandwidth continues to deliver multimedia resources in greater amounts and higher quality. The development of friendlier

What makes the Internet addictive?

Internet itself and

its content

Speed (bandwidth)

Accessibility

Intensity of

information

Potency

Replacement of

mass media

Internet users

Need for sex

Need for

achievement

Need for altered

state of

consciousness

Need for pleasure

The user and user

interactions

Need for

belonging

Need for

relationship

Anonymity

Interactivity

comfortably.

If we understand the Internet as a kind of mass medium, then the possibility surfaces that the Internet is in the process of replacing or substituting for a part of traditional media (i.e., television, radio, newspapers, magazines, books, and so on) (Chou & Chen, 2000). Grohol (1999) suggests that societal acceptance and promotion of the Internet must also be considered. If most of the information we need in our daily lives (e.g., from mass media) can be easily and cheaply obtained from the Internet, and activities (e.g., writing letters, making phone calls) can also be carried out from the Internet, it is no leap to predict that more and more people will spend more and more time on the Internet.

Young (1998) concludes that the Internet itself is not addictive, but specific applications embedded with interactive features appear to play a significant role in the development of pathological Internet use. Griffiths (1997, 1998) argues that the

structural characteristics

of particular activities are responsible for reinforcement, may satisfy users’ needs, and may actually facilitate excessive or pathological use. Structural characteristics, in his words, refer to the features that manufacturers design into their products. For example, the high degree of “interactivity” embedded in chat rooms and games may define alternative realities for their users. The “anonymity” of some Bulletin Board Systems may encourage the verbal disinhibition of many Taiwan high school students (Lin & Tsai, 2000). Similarly, the “undo” button, which allows gamblers to click on the screen and then automatically redo the last bet, may draw more and more gamblers to “virtual casinos” (King & Barak, 1999). Griffith (2000) argues that by examining such structural characteristics, we may gain a better understanding of what users’ needs are, how information is presented or misrepresented, and how users’ cognition is influenced and distorted.Inter net User s

In addition to examining the Internet itself and its contents, it is also important to examine what user’s needs are, and how the Internet meets those needs.

Suler (1999) argues that understanding such needs can illuminate how and why some people become pathologically involved with the Internet. The six needs he identifies include (1) sexual needs, (2) the need for an altered state of consciousness, (3) for achievement and mastery, (4) for belonging, (5) for relationships, and (6) the need for self-actualization and the transcendence of self. In this section,

sexual needs

,the need for achievement and mastery

,and

the need for pleasure

are discussed. The need for belonging and the need for relationshipsSex is always a popular topic in mass media; sex on the Internet— “cybersex” or “netsex” — is no exception. Suler (1999) claims that people become preoccupied with online sexual activities for the same two basic reasons people exhibit obsessive behavior regarding sex in any context: satisfaction of biological needs, and a variety of purely psychological and social needs. Sexual pursuits on the Internet can be both social and non-social. Social cybersex can become addictive because it is an easily accessed, anonymous, and medically safe way to satisfy one’s biological drive and psychological needs. In a non-social sexual situation, Internet users can easily and anonymously obtain pornographic images and animations and video clips; the Internet offers an almost infinite supply of such materials. Morahan-Martin & Schumacher (2000) report that pathological users are more likely than others to use the Internet’s adults-only resources. Young (1997) also suggests that sexual fulfillment is one of the potential explanations for pathological Internet use. However, Delmonico & Carnes (1999) argue that the process of becoming sexually addicted is a very complex one, and while the Internet provides a powerful way for sex addicts to act out their addictions, researchers have yet to provide conclusive evidence to support a claim that Internet use and sexual addiction have a causal relationship.

Suler (1999) also discusses the Internet’s ability to fulfill users’ needs for achievement and mastery. For many users who enjoy mastering the various technical features of software applications, computers and networks offer a motivating and rewarding cycle of challenge, experimentation, mastery, and success. For users who are less motivated by technological mastery, the challenges of discovering and becoming familiar with the various cultures and peoples represented on the Internet can be a never-ending source of fulfillment of curiosity and self-esteem. However, problems occur, as Suler notes, when obsessions with Internet achievement and mastery become a never-ending pursuit, but underlying needs are not fully met by Internet use. Kandell (1998) also works with the concept of users’ desire to exercise control over the computer and the Internet. This sense of control can be realized in human-computer contexts by a series of command-actions, as well as in interpersonal contexts wherein the user decides what, when, where, and with whom to communicate, and how to proceed with such communication.

Suler’s notion of the need for an altered state of consciousness (Suler, 1999) raises similarly interesting questions as Young’s concept of

unlocked personalities

and creatingonline

persona

(Young, 1997). Suler argues that people have an inherent need to alter theirconsciousness, to experience reality from different perspectives, and cyberspace may be a new and important arena in which to satisfy that need. For example, one’s sense of time, space, and personal identity can be changed on the Internet. Moreover, online personas,

parts of their personality, and allowing individuals to expand the range of emotions experienced and expressed toward others. Morahan-Martin (1999) also believes that the ability to change oneself online— an ability enhanced by the Internet— can be liberating. The ability to alter self-presentation, for example, to change the way other people perceive you, allows users to try out different ways of presenting themselves and interacting with others. These experiments are healthy most of the time; however, problems emerge when people have difficulty in “logging off” from their online personas as well as from the Internet.

Four studies in particular have emphasized users’ need for pleasure, and their pursuit of fulfillment of that need from the Internet. Indeed, people need fun, relaxation and pleasure to live balanced lives. Scherer (1997) finds that dependent Internet users report more personal or leisure time online (M = 7.8 hours) than nondependent users (M=3.7 hours). In other words, Internet-dependent students spend twice as much time online for leisure activities than do other students. Chou, Chou & Tyan’s study (1999) found that Taiwan college students’ Internet addiction scores were positively correlated with their total communication pleasure scores, in particular the “escape pleasure” scores and “interpersonal relationship pleasure” scores. Internet addicts seem to agree that they experience more pleasure in escaping from real life worries and responsibility through the pleasures of communicating with others online.

Chou & Hsiao’s study (2000) also found that the addicted group’s pleasure experience scores were significantly higher than those of the non-addicted group. Morahan-Martin & Schumacher (2000) report similar findings: the Internet provides a place to relax, escape pressures, and seek excitement. In their study, those with Internet-related problems were more likely than others to use the Internet for recreation and relaxation, wasting time, and gambling. Before the Internet gained its present popularity (when computers were mostly standalone), Griffith (1991) had already observed that some people used computer games for arousal or excitement while others used them as a form of escape. Problems arose when people gave up almost all other leisure time and activities to pursue online pleasures, exhibiting an intense preoccupation with the Internet.

The User and User Inter actions on the Inter net

The Internet, in many ways, is not only an information superhighway, it is a powerful social domain that connects its users around the world. As mentioned above, Suler (1999) argues that whether Internet use is healthy, pathologically addictive, or somewhere in between is determined by users’ multiple needs and how the Internet meets those needs. In particular, he addresses two interpersonal needs:

the need to belong

andthe need for relationships

. Everyone needs interpersonal contacts, social recognition, and a sense of belonging to livehealthy and balanced lives. Young (1997) also provides an explanation of online “social support” for Internet addiction. Social support is formed by groups of people who engage in regular computer-mediated communication with one another over extended periods of time. With routine or frequent visits to a particular newsgroup, chat room, or Bulletin Board System, in Taiwan’s case, familiarity and a sense of belonging can be established. As Morahan-Martin (1999) observe, the more time users spend online, the more likely they are to use the Internet for emotional support, meeting new people, and interacting with others. Young (1997) argues that a group dynamic of social support answers a deep and compelling need in people, especially those whose real lives lack social supports.

Qualitative as well as quantitative analysis indicates that two of the leading factors underlying pathological use of the Internet are the “anonymity” and the “interactivity” of online interpersonal communications. Young, Pistner, O’Mara, and Buchanan (1999) suggest that anonymity is associated with four general areas of dysfunction. Among them, two are interpersonal, the first being that the Internet provides a virtual context in which overly shy or self-conscious individuals are allowed to interact in a socially safe and secure environment. However, over-dependence on online relationships may result in significant problems with real life interpersonal and occupational functioning. The second dysfunction involving the anonymity of the Internet is cyber-affairs or extramarital relationships formed online which negatively impact marital or family stability. Scherer (1997) also argues that the anonymous nature of some Internet services and the elimination of visual cues may decrease social anxieties in online relationships for college students.

As mentioned above, “interactivity” has two aspects of particular importance for this discussion: human-computer interactions and human-human interactions. The Internet not only provides its users with the opportunity to encounter new people, it also provides additional— if not primary— communication tools for coping with existing relationships. This is frequently observed on college campuses. Scherer (1997) has found that 97.7% of college-student subjects have weekly access to the Internet in order to maintain relationships with family and friends. Chou & Hsiao (2000) provide similar findings: one student subject noted that, “You know somebody is always out there, you are not alone.” The authors observed that this “accompaniment” function is more desirable for many users than that of a television set or a radio, because the interactive feature of the Internet enables college students to connect with others reciprocally at any time; they do not just passively receive broadcast information from outside.

He argues that late adolescents and young adults contend with strong psychological and developmental dynamics. College-age students and non-students face two tasks: developing a sense of identity, and developing meaningful and intimate relationships. In some cases, addictive behavior serves as a coping mechanism for adolescents having trouble negotiating these developmental challenges. Kandell notes that college students frequently overuse the Internet’s two-way communication applications such as chat rooms, email, and Multi-User Dimension games. The danger for college students lies in the possibility that their Internet may become the central focus of their campus lives— particularly since most students are already negotiating the difficult terrain of identity and relationships.

Concluding Remar ks

As Rudall (1996) remarks, most psychologists have told us that we should not be surprised at the evolution of new behavioral conditions when technological advances are changing our society so rapidly and in such revolutionary ways. Indeed, we should not be surprised, but we must be prepared to face the notion that the Internet is changing the way we live, and not always for the better. Young (1999b) notes that the study of Internet addiction is often complicated by the perceived value of technological growth, by the societal promotion of Internet use, and by the positive image of the Internet. However, as Kendall’s analogy (1998) suggests, while exercise is good and people require it, over-exercise may have a destructively negative impact on human health. Internet use may be similar in the disparity of its impact, determined almost exclusively by amount and type of use.

The above review of studies on reasons of Internet addiction has progressed along with the growth of the Internet itself. From one perspective, the findings in this paper suggest that over-use or abuse of technology can have significant negative impacts on our lives. From another perspective, existing findings lead to reflection on how to appropriately and safely use technology. As Stern (1999) states, technologies, by definition, increase our capacities and abilities. However, at the same time, they may also enhance our ability to produce maladaptive behavior, and expose both frailties and inabilities. It is crucial for us to recognize that technologies are bound to impact on us in both positive and negative ways. Research on Internet addiction is one step toward understanding and evaluating the effects of these impacts.

Refer ences

Chou, C., Chou, J., & Tyan, N. N. (1999). An exploratory study of Internet addiction, usage and communication pleasure - The Taiwan’s case.

Internatinal Journal of Educational

Chou, C., Chen, S. H., & Hsiao, M. C. (1999).

Internet Addiction, usage, and gratifications –

The Taiwan’s college students’ case

. Poster presented at 107th American PsychologyAssociation (APA) Annual Convention, Boston, USA. August 20-24, 1999.

(Computers

& Education

,35

(1), pp. 65-80, 2000.)Chou, C., & Chen, S. H. (2000).

Internet addiction among Taiwan college students – An

on-line interview study.

Poster presented at the 108th American Psychology Association(APA) Annual Convention, Washington, D. C., USA.

Delmonico, D. L., & Carnes, P. J. (1999). Virtual sex addiction: When cybersex becomes the drug of choice.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2

(5), 457-463.Greenfield, D. N. (1999). Psychological characteristics of compulsive Internet use: A preliminary analysis.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2

(5), 403-412.Griffiths, M. D. (1991). Amusement machine playing in childhood and adolescence: A comparative analysis of video games and fruit machines.

Journal of Adolescence

. 14, 53-73.Griffiths, M. (1997). Psychology of computer use: XLIII. Some comments on ‘addictive use of the Internet’ by Young.

Psychological Reports

, 80, 80-82.Griffiths, M. (1998). Internet addiction: Does it really exist? In J. Gackenbach (ed.),

Psychology and the Internet: Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal

implications

. NY: Academic Press.Griffiths, M. (2000). Does Internet and computer ”addiction” exist? Some case study evidence.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3

(2), 211-218.Grohol, J. M. (1999). Too much time online: Internet addiction or healthy social interactions.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2

(5), 395-401.Lin, S. S. J, & Tsai, C. C. (2000).

Sensation seeking and Internet dependence of Taiwanese

high school adolescents.

Poster presented at the 108th American Psychology AssociationAnnual Convention, Washington, D. C., USA.

Kandell, J. J. (1998). Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1

(1), 11-17.King, S. A., & Barak, A. (1999). Compulsive Internet gambling: A new form of an old clinical pathology.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2

(5), 441-456.Morahan-Martin, J. M., & Schumacker, P. (2000). Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 16, 13-29.

Morahan-Martin, J. M. (1999). The relationship between loneliness and Internet use and abuse.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 2

(5), 431-439.Scherer, K. (1997). College life on-line: Healthy and unhealthy Internet use.

Journal of

College Student Development

, 38(6), 655-665.Young, K. S. (1997).

What makes the Internet addictive: Potential explanations for

pathological Internet use

. Paper presented at the 105th American PsychologicalAssociation Annual Convention, Chicago, IL, USA.

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1

(3), 237-244.Young, K. S., Pistner, M., O’Mara, J., & Buchanan, J. (1999). Cyber disorders: The mental health concern for the new millennium.