Partisan Politics and Redistricting in Taiwan,

2005-2007

*

Nathan F. Batto

**Abstract

This paper examines partisan politics in the redistricting process in Taiwan in 2005-2007 to explain why neither major party was able to obtain its best plan in every city or county. Theoretically, the degree of partisanship depends on the extent to which guidelines constrain decision makers, the partisan composition of decision making bodies, and the sequence of action. In this specific case, there were four stages. Redistricting plans went through local election commissions, the Central Election Commission, the legislature, and negotiations between the speaker and the premier. At each stage, the effects of the guidelines, composition, and sequence are considered in detail. In addition, three counties are examined, illustrating the three common patterns: consensus, dominance by the local election commission, and partisan conflict. From a public policy standpoint, the framework presented in this paper provides a way to assess how various reform proposals would alter the incentive and constraints facing various actors. Politically, the framework suggests how future redistricting may differ from the 2005-2007 round, especially if Taiwan has unified government.

Keywords: redistricting, boundary commission, divided government, election commission, electoral system reform

* The author thanks all the people who have read and commented on various drafts of this paper, especially Lu-huei Chen, Karen Long Jusko, Kuniaki Nemoto, and the anonymous referees.

** Assistant Research Fellow, Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica. Email: nbatto@gate.sinica. edu.tw.

On 10 June 2005, Taiwan revised its constitution to replace the old single non-transferable vote (SNTV) electoral system with a new mixed-member majoritarian (MMM) system. Unlike the old system which had featured large, multi-member districts, the new system elected 73 seats in single -member districts. 63 of these seats were located in cities and counties with two or more seats, so new district boundaries had to be draw in these 15 cities and counties. The redistricting process was carried out over the next year and a half, and during that time the two major parties sought repeatedly to obtain plans that would favor their interests. However, several factors combined to make it difficult for either party to secure their optimal plans. Overall, the final plans favored the Kuomintang (KMT) in some areas, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in others, and in many areas, consensus plans were reached. As a result, neither party could claim an outright victory in the redistricting process.

Theoretically, the degree to which a plan will be partisan or non-partisan depends on the extent to which rules and procedures constrain decision makers, the partisan composition of decision making bodies, and the sequence of action, which determines the relative influence of various decision makers. By examining the interaction of these three variables, I identify several concrete factors that frustrated efforts to gain partisan advantage in 2005-2007. First, large units were used as building blocks to construct the electoral districts. This limited the number of viable plans that actors could consider. Second, the first two stages of the redistricting process featured electoral commissions. These commissions were formally non-partisan and mandated to pursue non-partisan goals. Third, while the legislature could veto proposals from the Central Election Commission (CEC), it could not unilaterally amend those plans. This prevented the legislative majority from simply ramming through its favored plans. Fourth, in the event of a legislative veto, the two sides could propose alternatives to the CEC plans, but they were effectively required to come to an internal consensus on any alternative. This was often difficult, and in several cases the disgruntled side failed to propose an alternative plan. Fifth, divided government meant that the final reversion point was a lottery between the KMT and DPP plans. Unified government would have allowed the governing party to unilaterally impose its ideal plan.

Unfortunately, future rounds of redistricting may not go as smoothly as the 2005-2007 round. On the one hand, conditions might change. Most obviously, unified government would drastically alter the balance of power in the critical final stage, transforming it from one in which the two main parties have equal power to one in which the governing party could unilaterally make a decision. On the other hand, the actors may learn from the 2005-2007 experience and

alter their strategies in the future. For example, parties might learn how to more effectively pursue their collective interests. In short, there is clear potential for heightened partisan conflict in future redistricting efforts. This matters because a process defined by sharp partisan conflict could cause the public to see the electoral playing field as biased, and that, in turn, could erode the legitimacy of the democratic system. Various prominent proposals to reform the electoral system could either intensify or mitigate this danger. For example, increasing the number of seats might create more partisan conflict, while moving to a German-style mixed member proportional system might reduce partisan conflict.

This paper makes several contributions to the political science literature. First, it adds to the comparative redistricting literature by describing a concrete case of redistricting in detail. There are surprisingly few well-documented cases of redistricting, especially from outside the United States, and lack of detailed data is one of the largest hurdles facing the development of more generalized theories of comparative redistricting. This particular case has not previously been carefully documented in either the Chinese-or English-language literature. Second, by using a New Institutionalist approach of examining how actors pursued their interests within the constraints of a particular context, this paper focuses attention on several critical features of the process. Third, this paper has public policy implications. As Taiwan prepares for its second round of redistricting following the 2016 legislative elections and as it considers reforming the electoral system, the theoretical logic developed in this paper provides a way to predict the impact of various reform proposals and the likelihood of heightened partisan conflict.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. The second section reviews relevant literature. The third section traces out the redistricting process, and the fourth section discusses constraints on partisanship. The fifth section explores the incentives that the various actors faced in each stage of the redistricting process. The sixth section examines the empirical record, dividing the cities and counties into three different groups and presenting a case study in each group. The seventh section considers the implications for future rounds of redistricting. The eighth section considers several reform proposals and concludes.

I. Pursuit of Partisan Advantage in Redistricting

Literature on redistricting comes overwhelmingly from the American context and focuses extensively on how partisan politicians seek political advantage. Historically, most American

states have processed redistricting plans similarly to normal legislation, needing to first pass the state legislature and then to obtain the signature of the governor. One common observation is that in states with unified government, the redistricting plans tend to have a partisan bias in favor of the majority party. In states with divided government, the plans are more likely to favor incumbents from both major parties (for example, see Butler and Cain 1992, 2; Cain and Campagna 1987; Jacobson 1990, 94-96; Lyons and Galderisi 1995).

In recent years, widespread public dissatisfaction with these outcomes has led reformers to try to remove redistricting from the normal legislative process in order to diminish the influence that elected politicians have over the shape of their electoral districts. As of 2012, thirteen states have delegated some or all of the task to special commissions, which may be comprised partially or entirely of non-legislators and/or non-partisans (Cain 2012).

The much smaller comparative literature echoes the point that not all redistricting is done by legislatures or along partisan lines. According to one study of 87 countries, 43 of the 60 countries that delimit election districts do so by delegating the task to a boundary commission or election commission. In fact, the United States and France are the only countries in this dataset that both rely exclusively on single-seat districts and also allow legislatures the leading role the redistricting process (Handley 2008, 268-269).

Scholars stress three factors that allow these formally non-partisan commissions to prevent partisan influences from infiltrating the redistricting process including the goals and procedures set out in law, the composition of the commission, and the extent to which the commission dominates the redistricting process. In most countries, commissions are instructed to follow a certain set of guidelines or criteria in determining district lines. Some common criteria are equal populations, maintaining communities of interest, geographical compactness, and transportation links. Partisan advantage is rarely acknowledged as a legitimate concern for commission members. In some cases, these guidelines can be quite restrictive, even to the point that McRobie suggests that in New Zealand, redistricting processes “are seldom anything other than arithmetical exercises” (McRobie 2008, 30). Even when there is some wiggle room, commission members must justify their arguments in terms of the stated criteria.

Composition of the commission is important. Countries that allow legislatures to decide boundaries are faced with a legislative conflict of interest: the people who draw the district lines are precisely the ones who run in them (Cain 2012, 1817). A common complaint is that, instead of voters choosing politicians, politicians choose their voters. Delegating power to

boundary or electoral commissions removes, or at least dilutes, the power of these elected politicians. However, simply replacing elected partisan politicians with unelected partisans only has a minimal effect. McDonald finds a familiar logic in redistricting commissions employed by many US states: when one party has control over the redistricting commission, partisan plans tend to be produced (McDonald 2004). One common strategy to avoid this fate is to try to fill the commission with people with no partisan affiliation. For example, New Zealand’ s boundary commission is dominated by three senior civil servants, the Surveyor-General, the Government Statistician, and the Chief Electoral Officer (McRobie 2008, 30). In Canada, a judge chosen by the chief justice of the province chairs the three-person committee, and the other two members are often scholars (Courtney 2008, 13-14). In Japan, the 1994 redistricting commission included scholars, judges, civil servants, lawyers, and journalists, none of who were party members or elected officials (Moriwaki 2008, 108). Unfortunately, people with no public partisan affiliation do not always act in a non-partisan manner. Cain points out that in Arizona in 2011, the commission descended into bitter partisanship precisely because too many people suspected that the tie-breaking non-partisan member was actually a partisan in disguise (Cain 2012, 1833-1834). Similarly, Cox and Katz (2002) investigate the political affiliation of formally non-partisan judges in the United States and find that redistricting plans are more thoroughly explained when this variable is incorporated into the model. However, while these sorts of experiences from the United States might lead one to conclude that lofty rhetoric about non-partisan goals is simply cheap talk disguising underlying non-partisan motives, evidence from the rest of the world points to a less cynical conclusion. Various authors have noted the lack of overt partisan politics in the redistricting process in Canada (Courtney 2008), New Zealand (McRobie 2008), Mexico (Lujambio and Vives 2008), and Japan (Moriwaki 2008), even to the point that determining the name of Australian electoral districts can be more contentious than drawing the actual district boundaries (Medew 2008, 98). Commission members might place a high value on their public reputation as a non-partisan figure. For example, a civil servant might only rise to a top position in the bureaucracy by years of carefully avoiding partisan stances. Likewise, many judges place a higher priority on adhering to the spirit of the law than to pursuing an advantage for their favored party. In these cases, non-partisan commissioners apparently have actually made decisions according to the non-partisan criteria laid out in the rules.

The third factor, the extent to which the commission dominates the process, affects the degree to which commissions can defend non-partisan decisions from external partisan

influences. Generally speaking, commissions are empowered to make the first proposal. Being the first mover implies a certain amount of power, as first movers can sometimes strategically propose a plan that is difficult for subsequent movers to overturn (Romer and Rosenthal 1978). However, there are many conditions in which the first mover will not be able to dominate the outcome, and subsequent movers’ preferences may become more important. Thus, one way to rank the power of an electoral or boundary commission is to consider the capacity of subsequent movers to overturn its decisions. The weakest commissions are merely advisory. In Iowa and New York, for example, the commission recommends a set of boundaries, but the state legislature retains the right to modify or even discard those recommendations (Cain 2012, 1813-1815). The Washington state commission is somewhat more powerful, as the legislature only has a limited amount of leeway to modify the commission’s plans. Alaska, Idaho, and Montana go even further, as legislatures in those states cannot modify the commissions’ proposals at all (Cain 2012, 1819). However, in the United States, all redistricting plans can be challenged in court, and this may reintroduce a partisan element into the game. Partisans can systematically challenge plans disadvantageous to their own party, and they can seek hearing with friendly judges. Similarly, the possibility of overturning a plan with a referendum can also create a partisan “sore-loser incentive” (Cain 2012, 1808). The most powerful commissions do not face such a hurdle. In Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, the decisions made by the commissions are final.1 In these countries, the electoral commissions are widely regarded as

non-partisan, and the politicians have no opportunity to overturn their decisions (Courtney 2008; Lujambio and Vives 2008; McRobie 2008; Medew 2008).

In sum, the institutional rules play a major role in determining whether a redistricting plan will be determined according to partisan or non-partisan considerations. At one extreme, exemplified by most states in the USA, elected state legislators draw the districts they will personally run in, and these decisions are almost always dominated by partisan considerations. At the other extreme, exemplified by Canada, New Zealand, and Australia,2 plans are drawn

1 McRobie argues that timing also enhances the finality of the commission’s decisions in New Zealand. Because districting plans are formally announced only a few months before the next general election, politicians have to start organizing their campaigns immediately. They simply do not have any spare time to challenge the boundaries (McRobie 2008, 35).

2 It is tempting to attribute the similar outcome in these three countries to their common cultural heritage as former British colonies. However, Courtney points out that prior to the introduction of boundary commissions during the past half century, Canada had a long history of partisan gerrymandering

by commissions dominated by civil servants, judges, and other formally non-partisan figures according to non-partisan and highly constraining guidelines such as equal populations and maintaining communities of interest, and the decisions made by these commissions are final. In between these extremes, the degree of partisanship will vary based on how much influence partisans have within the drafting bodies, the amount of leeway implied in the guidelines, and the ease with which elected politicians can modify the proposals.

II. The Redistricting Process in Taiwan

Redistricting is governed by Article 37 of the Civil Servants Election and Recall Act (CSERA).3 Twenty months before the end of the legislative term, the CEC must send

redistricting plans to the legislature. Plans for each county and city are considered independently. The legislature can either adopt or veto the CEC’s plans; it cannot amend the plans. If the legislature chooses to veto a plan, the CEC must submit a new plan within thirty days. The CEC must consider the objections of the various party caucuses when formulating its revised plan. However, this clause does not require the CEC to follow the legislature’s direction. Legally, the CEC could insist that the legislature’s objections are unreasonable and submit the exact same plan or a modification that the legislature did not request. The resubmitted plans cannot be modified by the legislature. The legislature must either adopt a plan or veto it and continue to appeal to the CEC to modify the proposal. The legislature has until thirteen months before the end of the term to pass all plans. If it cannot meet this deadline, the CSERA empowers the heads of the Legislative Yuan (the speaker) and Executive Yuan (the premier) to jointly decide the redistricting plans for the cities and counties still in dispute. There are no limitations placed on the speaker and premier on how the districts should be drawn or how they should make these decisions. The plan must be promulgated twelve months before the end of the term.

The CSERA dictates that any redistricting plans should consider administrative boundaries, population distribution, geographical environment, transportation networks, and historical legacies. The CEC added a few more concrete guidelines. In a city or county with multiple seats,

(Courtney 2008, 12).

3 The CSERA clause governing redistricting had previously been used to change the multi-member districts in the old SNTV electoral system. Because SNTV allows for a degree of proportionality, past redistricting cases had mostly been uncontroversial. The 2005-2007 redistricting process was the first time that Taiwan had drawn a set of single member districts for a representative assembly.

the population of any single district should not deviate from the county or city mean by more than 15%. Townships4 should not be subdivided unless the population of a township exceeded

115% of the mean. If townships were subdivided, li5 were to be used as units. The CEC also

determined how many seats were to be elected from each district (see Yu 2008, 39-42).

The actual redistricting process included four major stages. First, the CEC delegated power to each county or city’s local election commission (LEC) to formulate a redistricting plan. After consulting with various political interests including incumbent legislators, each LEC typically came up with two to four different plans. These plans were presented at public hearings, giving various interests opportunities to express opinions. LECs spent the latter half of 2005 preparing various plans and held public hearings in January through March 2006. Proposals were submitted to the CEC by the end of March.

In the second stage, the CEC decided which plans to submit to the legislature. In most cases, the CEC simply approved the LEC’s choice. In a few cases, the CEC rejected an LEC plan and substituted an alternative. This generally only happened when the LEC violated one of the CEC’s guidelines, such as drawing districts with too large or too small populations. The CEC submitted its bill to the legislature on May 30, 2006.

Third, the legislature considered the CEC’s proposal. The bill was submitted to the Internal Affairs Committee, which held a hearing on June 19. At this hearing, the plans for most counties and cities were approved without objection, but a few legislators proposed alternative plans. On June 30, the floor submitted the bill to inter-party negotiations.6 There is no further record of the

bill until December 12, when it was brought up on the floor and tabled. On December 15, the floor decided to pass fifteen plans,7 veto four, and reserve judgment on the other six. By law,

4 I use township as a generic term covering the administrative level underneath counties and county-level cities, including cities (shi), towns (zhen), villages (xiang), and districts (qu). Township populations vary

widely, from as few as 1,000 people to as many as half a million people. Most townships have between 20,000 and 100,000 people.

5 The administrative unit below the township is the cun or li. These units are called cun in more rural townships and li in more urban townships. Townships that are large enough to require subdivision in

the redistricting process are all more urban, so I use the term li exclusively in this paper. A single li

generally has between 1,000 and 10,000 people.

6 Inter-party negotiations are a standard part of the legislative process in Taiwan. After bills pass committee and before they are considered by the floor, party leaders meet to try to negotiate a consensus. There is no record kept of these meetings.

the CEC had thirty days to resubmit a new bill for the four counties and cities to the legislature. However, since the deadline for the legislature to pass the redistricting bill was December 31, the CEC simply declined to submit a new bill.

In effect, by failing to act before November 30, the legislature forfeited its right to demand a second bill. It was able to pass the uncontroversial plans and to publicly state objections to the four vetoed plans, but by waiting until mid-December to act, it effectively yielded the final decision to the speaker and premier.8

In the fourth stage, the speaker and premier negotiated throughout January 2007 without much success. They were able to reach consensus on two of the counties, but the other eight remained unreconciled. On January 31, the final day, the Speaker and Premier drew lots to determine which plans would be adopted. The CEC immediately promulgated the new election districts, thus meeting the one year deadline specified in the CSERA.

III. Constraints on Partisanship from Non-Partisan Goals

This section considers the first of the three factors identified by the literature that can affect the degree of partisanship of a redistricting plan. In Taiwan, the various actors were constrained in their ability to draw lines by the criteria established in the CSERA and the guidelines issued by the CEC. None of these were hard, objective limits. Actors were mandated to consider transportation networks, geography, and historical legacies, though it was unclear what this meant in drawing any specific line. The CEC’s guidelines on equal population and the units to be used as building blocks in constructing districts were presented as exactly that: guidelines. While they were intended to be respected in all but extenuating circumstances, they were not presented as inviolable limitations. Nevertheless, these principles did constrain the options available to the various actors.

The 15% limit on population variance was arbitrary, though it seems never to have been seriously defended or challenged. Internationally, there is no universally accepted standard among democracies. At one end, Japanese law allows for deviations as large as 33% from the

four seats.

8 This is not as much of an abdication of power as it might seem. Since the legislature could not demand specific changes, it had no assurance that a second bill would be any better – or even any different – than the first one.

national mean, and Canada aims for districts to differ by no more that 25%. However, both violate even these lax rules with regularity (Courtney 2008; Moriwaki 2008). At the other extreme, deviations in the United States are almost always less than 1%, and one plan was rejected by a court for a deviation of a mere nineteen people (Lublin 2008, 143). Clearly, there are arguments to be made for allowing either larger or smaller deviations. However, these arguments were generally absent during Taiwan’s redistricting process. The CEC presented the 15% principle, and most people accepted it as reasonable without the kinds of philosophical debates that have occurred in other countries.

The requirement to use townships as building blocks, except for the cases in which the townships were too big, proved a fairly significant restriction. In the counties and cities that had to be divided into multiple election districts, the number of townships ranged from thirteen to thirty-three. With such large units, there simply were not many possible combinations to choose from that satisfied the 15% requirement. The number of combinations grew markedly when large townships were split and designers could draw districts using li. Not coincidentally, the main

controversy in most of the plans that ended up in the lottery dealt with how to divide li in large

townships.

The historical legacies mandate further constrained actors. Actors could not simply put any adjacent townships together; some groups of townships were widely understood as more natural than others. For example, in the northwestern corner of Taichung County, Dajia, Daan, and Waipu townships are widely understood as belonging together (see Figure 2). All three share a border with Qingshui to the south, but Qingshui is understood as part of a different group. There are various reasons for this understanding. Economically, Daan and Waipu are smaller towns that are satellites of Dajia. Administratively, the three are grouped together as a police district9 and

as a county assembly district. Geographically, there is a river separating the three of them from Qingshui. Most of the smaller roads connect the three, while only a few large roads, designed more for long distance traffic, cross the river.

One way to understand the desire to respect township boundaries and to group townships like these together is that there were popularly shared mental models (Denzau and North 1994) that politicians had to respect. Another, perhaps more compelling, way is to note that the politicians’ interests, most obviously in their mobilization networks, were deeply embedded within these institutional structures. Either way, there was a strong impulse to try to put these

clusters of townships in the same legislative districts. As a result the number of acceptable puzzle pieces was actually smaller than the number of townships. Actors almost always defended or criticized plans in terms of these historical legacies.

In short, actors did not have much freedom to pick and choose which areas would fit into a district. This is markedly different from the United States, for example, where the basic unit is the (very small) census tract and inconvenient historical factors are simply ignored, allowing politicians the freedom to draw exactly the districts they want (Jacobson 2001, 8). In some areas, these large units left enough room to for intense arguments over how the lines were to be drawn. In others, especially those with only two seats, the constraints were strong enough to preclude much meaningful choice. Moreover, since the redistricting process was supposed to be nonpartisan, arguments for and against the various plans were presented in terms of these nonpartisan constraints. The LECs and the CEC, in particular, had to justify their actions in these terms.

IV. Partisan Incentives and Constraints in the Four Stages

This section looks at the four stages in reverse order to examine the incentives facing actors at each stage. In terms of the three factors affecting the degree of partisanship of a redistricting plan, this section focuses on the second and third factors, the composition of the body making the decision and the impact of that body’s location in the decision process.

The CSERA designated the final stage as a negotiation between the premier and the speaker. In the 2005-2007 period, Taiwan experienced divided government. The DPP had won the presidency in March 2004, and President Chen had appointed fellow DPP member Su Tseng-chang as premier. In December 2004, the KMT-led blue camp had won a majority in the legislature, and that majority had chosen KMT member Wang Jin-pyng as speaker. During the redistricting negotiations, these two acted as representatives10 of their coalitions, the green and

blue camps,11 respectively. Since the CSERA did not instruct them on how to decide in the event

10 In addition to their institutional positions in which their power stemmed from a partisan logic, Premier Su and Speaker Wang also had another reason to act as leaders of their coalitions. In January 2007, both were seeking their party’s presidential nomination and would have wanted to build a broad support base within the party. As it turned out, neither won the nomination.

11 The blue camp was a coalition of the KMT, PFP, New Party, and several independents, while the green camp was a coalition of the DPP and the TSU.

that they could not reach a consensus, they decided to resolve disputes by lottery. If no agreement could be reached, the two sides would draw lots, and each plan would have a 50-50 chance of being adopted.

One prominent school in the literature on legislative organization, most closely associated with Cox and McCubbins (1993; 2005), argues that coalitions of legislators form procedural cartels. Party leaders are endowed with powers to arrange the agenda in ways that benefit the members of the cartel. However, these powers are limited. The first rule for all party leaders is that they must never push bills that will divide their party (Cox and McCubbins 2005, 24). In the redistricting process, the speaker and premier had to decide which, if any, alternatives to the bill proposed by the CEC they would support. Cartel theory suggests that they would only support alternatives that none of the major stakeholders within their coalition opposed. The most important stakeholders were incumbent legislators, and this suggests that any alternate plan that, relative to the CEC plan, had a significant negative impact on the chances of re-election of any incumbent within the coalition would not be supported by the party leader. In this paper, legislators are hypothesized to want to draw districts lines so that (a) support for their party is as high as possible, (b) the district covers as much of their personal vote as possible, and (c) no powerful rival, especially from their own party or camp, would also have a home base in their district. Different legislators will place different priorities these three characteristics. The party leader could be expected to support the most advantageous plan to his party that no major stakeholder stridently opposed. If no such plan could be found, the party leader simply supported the CEC plan.

The third stage was the legislative stage. Although the blue camp held a narrow majority over the green camp, most business in the Taiwanese legislature is conducted by consensus. An objection by a single legislator often suffices to block an item on the agenda. Of course, this objection can be overridden by a roll call vote, but roll call votes have to be carefully stage-managed. The coalition must notify all its members that a vote will be taken so that all will know to attend that session, and often the party must expend considerable efforts to mobilize members, especially if members do not particularly want to go on record as being for or against a particular measure. Because of these high transaction costs, consensus is the preferred model. No roll call votes were taken in the redistricting process. Since only plans that had consensus could pass, any legislator could stop the passage of the CEC plan and send it to the next stage.

could hope for a better outcome. To get this, she would need to propose an alternate plan that her party leader would support. This way, she would have a 50% chance of winning the lottery and getting her favored plan. This requires proposing a plan that all the other major stakeholders in the coalition do not object to. Formulating such a plan is no easy task. Each line on the map can be seen as a bargain aggregating and weighing the preferences of myriad interests. Forging such a complete set of bargains would have been particularly challenging in the bigger counties and cities, with more seats, more stakeholders, more complex webs of interests, and more lines on the map to be negotiated. Any change in one line might require changes in a number of other lines which, in turn, might cause an uproar. While the LEC had institutional mechanisms and sufficient time to sort out these problems, legislators wishing to produce an alternate plan often did not.

On the other hand, the legislator could simply be position-taking. In this case, the purpose of her opposition to the CEC plan would be primarily aimed at mollifying the dissatisfaction of her constituents. In these cases, the legislator might propose an alternate plan that looked good from the perspective of her constituents, even if that plan had almost no chance of winning the support of the party leader.

In the second stage, the CEC decided on a plan to send to the legislature. During 2006-2007, the CEC was a subordinate body of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. In the past, the Internal Affairs minister had also chaired the CEC, but by this period this was no longer the case. According to Article 8 of the CSERA, members of the CEC are appointed by the president at the request of the premier. There must be some nonpartisan members, and no more than two-fifths can come from any single party.

In practice, the CEC had a mildly partisan slant in favor of the president’s party, which in the 2005-2007 period was the DPP. However, this partisan slant was tempered by a strong opposition presence in the CEC. Moreover, as an officially non-partisan body, the CEC had to justify all its decisions strictly in the non-partisan terms set out in the CSERA and in its own guidelines. This meant that the CEC generally was only able to make changes favorable to the green camp when the LEC plan blatantly violated those non-partisan criteria.

Leaving aside minor adjustments with very little political impact, the CEC acted as follows. If the LEC plan did not violate any of the non-partisan criteria, the CEC approved it. If a plan that favored the green camp violated some criterion, the CEC urged a modification but did not insist on it. If the LEC plan both favored the blue camp and violated some criterion, the CEC rejected

it and substituted a plan more favorable to the green camp. There were two instances of this, in Taichung City and in Taoyuan County. The Taichung City case, in particular, illustrates the limits of the CEC’s power. The blue camp stakeholders in Taichung City had formed a consensus around the LEC’s plan. When the CEC rejected it,12 blue camp legislators simply proposed

the LEC plan to the Speaker who supported it all the way to the lottery. Thus, the CEC’s action did not block the blue camp’s favored plan. At most, the CEC put a plan favorable to the green camp on the table. However, the green camp seemed to universally favor this plan, and it is likely that they would have proposed it to the premier even if the CEC had approved the LEC plan. In short, it is probable that there would have been a lottery between the two plans regardless of the CEC’s decision. In the other case, Taoyuan County, the CEC’s action was more consequential. In the LEC plan, the population of three of the six districts deviated by more than 15%. The CEC rejected this plan, and the blue camp made no attempt to reintroduce it in later stages. It is likely that there were important people within the blue camp who did not want to violate the 15% guideline and would have appealed to the Speaker not to support the plan in the final stage. Thus, the CEC could only effectively reject a plan if the camp supporting it was not unified in that support.

LECs were the first movers in the redistricting process. LECs are officially subordinate to the CEC. According to Article 8 of the CSERA, members of LECs are appointed by the Premier at the request of the CEC. There must be some nonpartisan members, and no more than half can come from any single party. In practice, LECs are dominated by the local city or county executive. In nearly every case, the chair of the LEC was either the executive or the deputy executive. As such, it is reasonable to assume that the LEC made decisions in accordance with the local executive’s preferences.13 Thus, to the extent that the LEC had viable alternatives to

choose from, it could be expected to propose a plan benefitting the local governing party in some way. Even so, LECs were still formally non-partisans and had to at least pay lip service to the non-partisan guidelines.

12 The CEC rejected the plan because it split an administrative district with a population far below the 115% threshold.

13 This paper concentrates on partisan preferences. However, preferences could also be factional or personal.

V. Three Patterns

The redistricting processes in the fifteen cities and counties with at least two seats fell into three distinct patterns. The first pattern includes consensus cases. In these cases, the choice proved fairly uncontroversial because historical legacies determined the district boundaries or significantly reduced the number of lines to be drawn. These tended to be smaller cities and counties. The outstanding feature of the second pattern is the dominant role played by the LECs. In these cases, the LEC plan gave some clear advantage to the local governing party, but the other party never managed to propose a substantial challenge to the LEC plan. These tended to be the larger cities and counties. The third pattern, partisan competition, includes cases in which each camp championed a plan that conferred upon them a distinct advantage. These cases tended to include the medium-sized cities and counties.

The empirical strategy of this paper is as follows. First, I discuss the general pattern observed in all of the cases in a particular category. Second, I focus on one case within that category, illustrating how the pattern played out in a specific context. In several instances, I speculate on how a particular plan affected a specific stakeholder’s interests. Since successful politicians rarely try to justify public choices by explaining to voters how those choices will affect their personal self-interest, it is usually necessary to assume a certain set of interests. As previously mentioned, stakeholders are assumed to want districts in which their party is popular, they have a strong personal vote, and in which they have fewer rivals for the seat. The extent to which a particular plan aligns with those interests is evaluated by examining the electoral record.

Some observers have judged the effects of the redistricting process by the results of the 2008 election (for example, see Teng, Wu, and Ko 2010). This is problematic. There was a substantial partisan swing away from the DPP and toward the KMT in 2008. As a result, the KMT easily won districts that had been expected to narrowly lean to the KMT or that had been expected to be tossups, and it even managed to win many districts that had been expected to be solid DPP seats. Looking through the lens of 2008, it appears that all the carefully drawn lines were meaningless. However, very few people expected such a large partisan swing while the redistricting process was being carried out in late 2005 through early 2007. The 2012 election did not feature a similar massive partisan swing, but it was temporally much further away from the redistricting process. At any rate, the best information available to actors at the time would have been the 2004 legislative election results (Wu 2008). The 2004 election, conducted under SNTV

rules, is also a good indicator of incumbents’ personal votes. Because of this, I judge the various plans by the results of the 2004 legislative election.

1. Consensus

The first category includes consensus cases. In these seven cities and counties, the redistricting process proved to be fairly uncontroversial. There were three main reasons that these cases could be resolved rather easily. First, there were often pre-existing focal points that conveniently divided the population into appropriately sized pieces. For example, people in Yunlin County often talk about their county in terms of the coastal and inland regions. The politicians’ interests follow these lines, as most are markedly stronger in one region or the other. Since Yunlin County had two seats, it was fairly easy to settle on one coastal and one inland district. Moreover, there was already a pre-existing division. The National Assembly districts used in 1991 and 1996 had already divided the county into equal-sized coastal and inland districts, and it was quite easy to simply adopt those districts. County assembly districts were another commonly used focal point. Again, politicians’ mobilization networks are often embedded within these county assembly districts. Most legislators are supported by several county assembly members, and some were themselves former county assembly members. In Yunlin County, each of the legislative districts included three county assembly districts. These pre-existing focal points were much easier to find in smaller cities and counties, especially those that only had two seats. All but one of the two-seat cities and counties fell into the consensus pattern (see Table 1).

Second, a city or county might end up in the consensus category because a complex choice could be reduced to a much simpler one. In some districts with three or four seats, it was often possible to come to a consensus on one or two of the districts, leaving only one line to be drawn. Sometimes this was because there was a focal point that defined some, but not all, of the districts. In other cases, the requirements of geographic contiguity, equal population, and respect for administrative boundaries simplified the choices.

Third, sometimes it was possible to find consensus on the choices that remained because the major stakeholders were able to find a solution that all found acceptable.

The seven cities and counties in the consensus category featured very little partisan conflict. This may have been because all relevant political forces simply agreed on the lines, but this consensus may also have been due to the use of big building blocks. Because townships could not be divided, many contentious plans were simply never proposed.

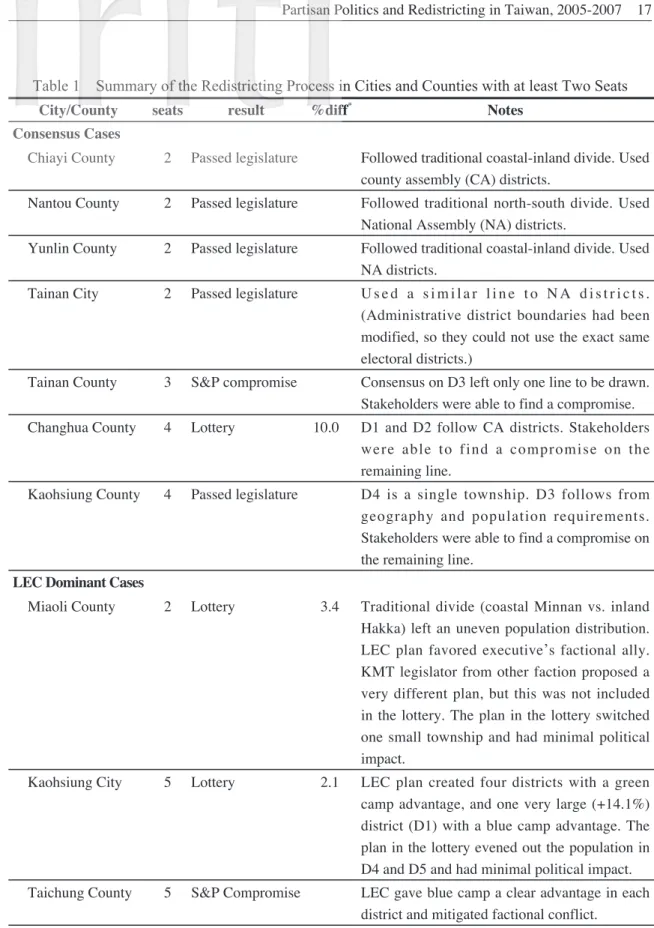

Table 1 Summary of the Redistricting Process in Cities and Counties with at least Two Seats

City/County seats result %diff* Notes

Consensus Cases

Chiayi County 2 Passed legislature Followed traditional coastal-inland divide. Used county assembly (CA) districts.

Nantou County 2 Passed legislature Followed traditional north-south divide. Used National Assembly (NA) districts.

Yunlin County 2 Passed legislature Followed traditional coastal-inland divide. Used NA districts.

Tainan City 2 Passed legislature U s e d a s i m i l a r l i n e t o N A d i s t r i c t s . (Administrative district boundaries had been modified, so they could not use the exact same electoral districts.)

Tainan County 3 S&P compromise Consensus on D3 left only one line to be drawn. Stakeholders were able to find a compromise. Changhua County 4 Lottery 10.0 D1 and D2 follow CA districts. Stakeholders

were able to find a compromise on the remaining line.

Kaohsiung County 4 Passed legislature D4 is a single township. D3 follows from geography and population requirements. Stakeholders were able to find a compromise on the remaining line.

LEC Dominant Cases

Miaoli County 2 Lottery 3.4 Traditional divide (coastal Minnan vs. inland Hakka) left an uneven population distribution. LEC plan favored executive’s factional ally. KMT legislator from other faction proposed a very different plan, but this was not included in the lottery. The plan in the lottery switched one small township and had minimal political impact.

Kaohsiung City 5 Lottery 2.1 LEC plan created four districts with a green camp advantage, and one very large (+14.1%) district (D1) with a blue camp advantage. The plan in the lottery evened out the population in D4 and D5 and had minimal political impact. Taichung County 5 S&P Compromise LEC gave blue camp a clear advantage in each

Taipei City 8 Lottery 2.7** LEC plan left only one good district (D2) for green camp. The plan in the lottery would have given the blue camp a further slight advantage by shifting voters from D8 to D5. This plan also shifted some voters from D6 to D8.

Taipei County 12 Lottery 0.5 LEC protected the local executive’s hometown by dividing it into two districts (D6, D7) and not adding any outside areas. These were the two smallest districts (-13.3%, -11.7%) in the county. LEC plan also gave the blue camp a small advantage in both of these districts instead of creating one blue and one green district. The alternate plan shifted a few voters from D5 to D4 and had minimal partisan impact.

Partisan Conflict Cases

Pingtung County 3 Lottery 18.3 The DPP plan gave the green camp an edge in each district, and each incumbent had an optimal district. The KMT plan created one good district for the blue camp and one good district for an allied independent.

Taichung City 3 Lottery 20.5*** The KMT plan gave the blue camp an edge in each district and put its incumbents into different districts. The DPP plan created one tossup district.

Taoyuan County 6 Lottery 14.4 The KMT plan put three DPP incumbents into D2. The DPP plan put two of them in D3 and left only one in D2. The DPP plan traded a reduction in the blue camp advantage in D3 for an increase in the blue camp advantage in D6, where it had no incumbents. Further, the DPP plan put a Minnan KMT incumbent’s hometown into a primarily Hakka district (D2).

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission. Notes: *

% diff is calculated by dividing the population that would have changed districts by the total population. Only plans in the lottery are considered.

**

The alternate plan in Taipei City was never formally proposed by the LEC, CEC, or in the legislature, and I have not been able to find the details of the plan. However, since it was included in the lottery, there must have been a complete plan. I assume the plan transferred exactly the number of residents from D6 to D8 necessary to achieve equal populations between these two districts.

***

In Taichung City, population figures for the KMT plan are not available. The %diff was calculated using eligible voters in the 2004 legislative elections.

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission.

Notes: (A) Under Yang’s plan, this township moved from D4 to D2. (B) Under Yang’s plan, this township moved from D3 to D4. (C) Under Yang’s plan, this township moved from D4 to D3.

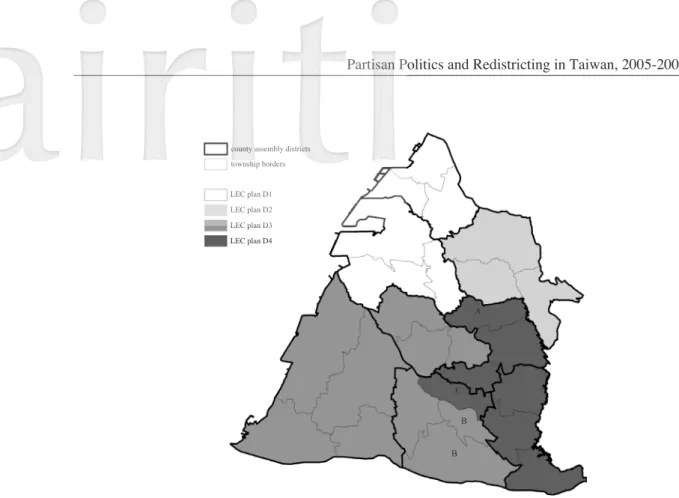

Figure 1 Map of Changhua County

These patterns are nicely illustrated in Changhua County, which has four seats (see Figure 1). With 26 townships, a compact geographical shape, no major rivers or mountains within the county borders, and a fairly homogenous ethnic population, one might expect that Changhua could be divided in many different ways. Instead, the process turned out to be fairly simple. Changhua has four major population centers, one in each corner of the county. The three townships in the county assembly district in the northeastern corner of the county have enough people to form a legislative district (D2). Likewise, the six townships in the two county assembly districts in that northwestern corner of the county are also big enough to form a legislative district (D1). Thus, these conveniently available focal points reduce the choice to the relatively simple task of dividing the remaining areas into two equal-sized districts. This task is a little harder. The southwestern (D3) and southeastern (D4) districts meet in the seventh county assembly district. Because both D1 and D2 are slightly undersized, both D3 and D4 must be slightly oversized, and putting all of the seventh county assembly district into one or the other would produce a district that exceeded the 15% threshold. As a result, the seventh county assembly district had to be divided. This did not turn out to be as contentious as one might have expected. The various

county assembly districts township borders LEC plan D1 LEC plan D2 LEC plan D3 LEC plan D4 A B B C

stakeholders settled on a plan, and, until very late in the process, it appeared that there would be no opposition at all to the LEC plan. One reason that it turned out to be so easy to divide the seventh county assembly district is that none of the incumbent legislators were from any of the four townships in that district. None of them were markedly stronger in one township than the others, so all of them were relatively indifferent to which of the four townships ended up in their district and which ended up in the other district (see Table 2).

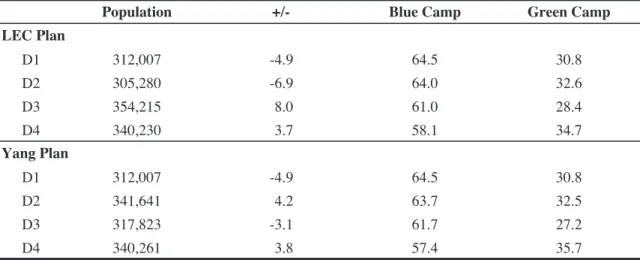

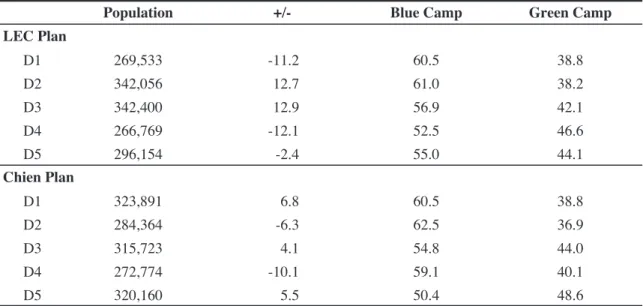

Table 2 Changhua County Redistricting Plans

Population +/- Blue Camp Green Camp

LEC Plan D1 312,007 -4.9 64.5 30.8 D2 305,280 -6.9 64.0 32.6 D3 354,215 8.0 61.0 28.4 D4 340,230 3.7 58.1 34.7 Yang Plan D1 312,007 -4.9 64.5 30.8 D2 341,641 4.2 63.7 32.5 D3 317,823 -3.1 61.7 27.2 D4 340,261 3.8 57.4 35.7

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission.

Notes: Total population=1,311,732; average district population=327,933. The last two columns show the percentage of the vote won by all Blue and Green Camp candidates, respectively, in the 2004 legislative elections.

Late in the legislative stage, an independent legislator affiliated with the blue camp, Yang Chung-tse, proposed an alternative to the LEC plan. Yang’s plan was very similar to the LEC plan. It split the seventh county assembly district in slightly different way and also shifted one other township between D4 and D2 to satisfy the population requirements. It should be noted that Yang was not from any of these townships, and his plan increased his chances of winning by only a moderate amount.14 However, as none of the other stakeholders from the blue camp were

from any of the affected townships, they were mostly indifferent to Yang’s plan. The Speaker supported Yang’s plan in the lottery, where it lost to the LEC plan. Thus, even though this case eventually ended up in the lottery, the two plans in the lottery were similar enough that they can be considered as two versions of the same general consensus.

14 In the 2004 election, Yang won 11.1% of the votes in the LEC’s proposed D3, while he won 12.1% in his plan’s D3.

2. LEC Dominant

The second pattern includes five cities and counties in which the LEC proved dominant. Like the areas in the first pattern, the LEC plan was never fundamentally challenged. Unlike those areas, the areas in the second pattern faced real choices, and the choices made in the LEC plan conferred significant advantages on the local executive’s party. Another way of saying this is that there were viable alternatives that would have been significantly better for the other camp. However, these alternatives were either not proposed or proposed but not supported by the party leader in the lottery stage. As argued above, party leaders were only predisposed to support alternative plans that were not opposed by any of the major stakeholders within the camp. In these LEC dominant cases, all significant alternatives ran afoul of this condition. In every case, it is possible to point to some stakeholder whose interests would have been seriously compromised by the alternate plan and who would have protested vigorously. As a result the camp was never able to come to an internal consensus on an alternate plan that differed fundamentally from the LEC plan. While most of these cases eventually did end up with a lottery, there were no substantive challenges to the LEC plan. Rather, the alternate plans were rough copies of the LEC plan with only one or two very minor changes. Table 1 shows the percentage of the total population that would have been shifted to another district in the other plan in the lottery. In each case in this category, it is less than 4% of the total population. Generally, the changes had almost no partisan impact. In short, regardless of the lottery result, the winning plan was either the LEC plan or almost identical to the LEC plan.

The LEC dominant pattern was most likely to appear in bigger cities and counties. Even though only five of the fifteen cities and counties with at least two seats fell into this pattern, these five held more seats (32) than the other ten combined (31). The size and complexity of these areas meant that they were less likely to have focal points that might reduce the redistricting process to a trivial choice or a choice that could easily be resolved. Moreover, that very size and complexity worked against the local opposition party. With more stakeholders, the chances that at least one fared relatively well under the LEC plan were high. Redrawing one line could require redrawing most or all of the lines, and negotiating new lines among so many stakeholders was extremely difficult. Size empowered the LEC.

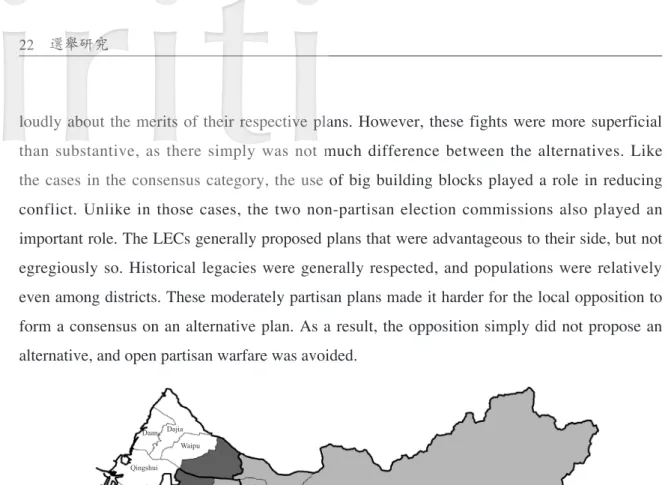

Cities and counties in the LEC dominant category did not end up with open partisan conflict. To be sure, most of these cases ended up in the lottery, and the two camps argued

loudly about the merits of their respective plans. However, these fights were more superficial than substantive, as there simply was not much difference between the alternatives. Like the cases in the consensus category, the use of big building blocks played a role in reducing conflict. Unlike in those cases, the two non-partisan election commissions also played an important role. The LECs generally proposed plans that were advantageous to their side, but not egregiously so. Historical legacies were generally respected, and populations were relatively even among districts. These moderately partisan plans made it harder for the local opposition to form a consensus on an alternative plan. As a result, the opposition simply did not propose an alternative, and open partisan warfare was avoided.

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission.

Figure 2 Map of Taichung County

The LEC dominant pattern is nicely illustrated by Taichung County, which had five seats (see Figure 2). The local executive in Taichung County was from the KMT, so it is reasonable to expect advantages for the blue camp in the LEC plan. Two are particularly evident. First, the LEC plan gave the blue camp a clear partisan advantage in each of the five districts. As will be seen, it would have been possible to formulate a plan in which there was at least one tossup district, so the LEC plan was clearly better for the blue camp.

Second, the LEC plan mitigated conflict between the KMT’s two local factions. The LEC plan had a very small D1 (-11.2%) and a very large D2 (+8.8%). This disparity could easily have been mitigated by switching Shalu and Wuqi townships between the two districts.15 However,

15 This would have left D1 3.6% below and D2 1.2% above the average. This change was mooted at a

Chien plan districts township borders LEC plan D1 LEC plan D2 LEC plan D3 LEC plan D4 LEC plan D5 Daan Dajia Waipu Qingshui Wuqi Shalu Taiping Dali

this switch would have caused problems within the KMT’s local factions. Under the LEC plan, Yen Chin-piao, a Shalu-based independent allied with the blue camp and a member of the Black faction, was in the same district (D2) as another Black faction incumbent. The switch would have put him into a district (D1) with a Red faction legislator. From the blue camp’s perspective, negotiating a compromise between two Black faction members over who would be the nominee probably looked much easier (see Table 3).

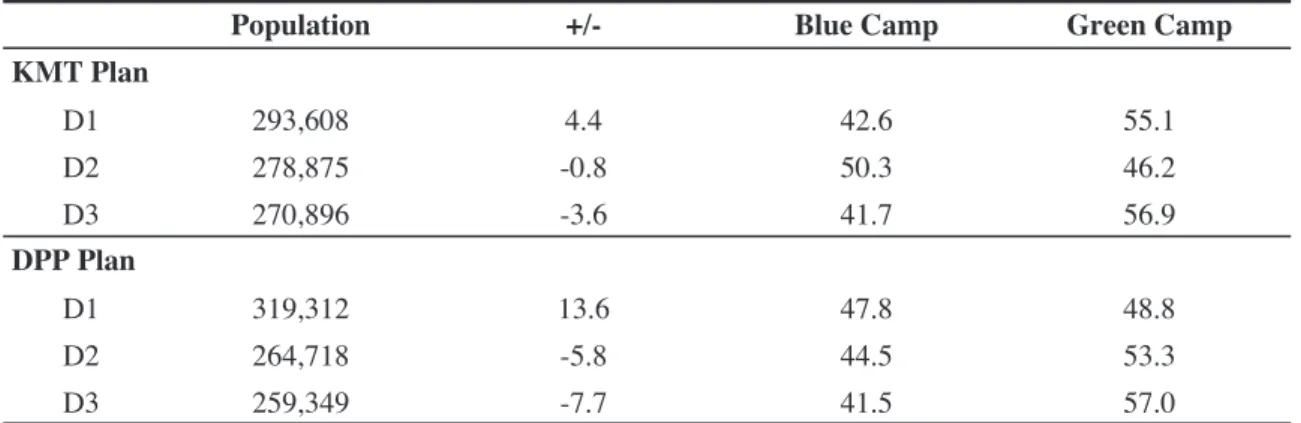

Table 3 Taichung County Redistricting Plans

Population +/- Blue Camp Green Camp

LEC Plan D1 269,533 -11.2 60.5 38.8 D2 342,056 12.7 61.0 38.2 D3 342,400 12.9 56.9 42.1 D4 266,769 -12.1 52.5 46.6 D5 296,154 -2.4 55.0 44.1 Chien Plan D1 323,891 6.8 60.5 38.8 D2 284,364 -6.3 62.5 36.9 D3 315,723 4.1 54.8 44.0 D4 272,774 -10.1 59.1 40.1 D5 320,160 5.5 50.4 48.6

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission.

Notes: Total population=1,516,912; average district population=303,382. The last two columns show the percentage of the vote won by all Blue and Green Camp candidates, respectively, in the 2004 legislative elections.

The LEC plan was approved by the CEC. In fact, the KMT-dominated LEC may have acted strategically to avoid giving the DPP-leaning CEC any excuse to overturn its plan. In an early version of the LEC plan, Taiping and Dali townships were combined to form D3, even though their combined population was 16.8% above the mean. However, the LEC eventually decided not to challenge the guideline instructing that all deviations should be less than 15%. In the plan that that the LEC submitted to the CEC, around 12,000 people were shifted out of Dali and into D2, bringing the population of D3 down to only 12.9% above the mean.

The LEC plan met with opposition in the legislature. There were two alternative plans proposed. Notably, neither of these plans involved switching Shalu and Wuqi townships between

D1 and D2, even though that seemed to be an obvious proposal for the green camp. In fact, there is a good reason that the green camp might not be able to agree on that alternative. The DPP had an incumbent based in D1, but not in D2. Moreover, the green camp was much stronger in Wuqi, where it won 40.6% of the vote in 2004, than in Shalu, where it only won 32.8%. The incumbent in D1 would have almost certainly have vigorously opposed this switch if it had been proposed.

A former DPP legislator, Chien Chao-tung, supported by supported by incumbent PFP legislator Feng Ting-kuo, proposed a fundamentally different plan. Chien and Feng, both based in Dali, faced the same problem in the person of KMT legislator Chiang Lien-fu, a very strong politician from Taiping. Feng did not want to compete with Chiang for the nomination, and Chien did not want to face Chiang in the general election. Chien’s plan would have resolved this problem by putting Taiping and Dali into different districts. Under Chien’s plan, Chiang would have shifted to another district (D4), and Chien and Feng would have had a chance to face each other in the Dali district (D3). This change required a substantial change in every other district as well.16 From the DPP’s point of view, this plan also would have had the advantage of

creating a district (D5) in which the two camps had nearly even levels of support. Despite this, Chien’s plan was never seriously considered. Perhaps it is not surprising that Feng was unable to convince Speaker Wang to oppose the LEC plan since the LEC plan generally was beneficial to the blue camp. However, green camp politicians were also unable to unite behind this alternative. It is quite easy to point to politicians who would have been losers. Three of the four incumbent DPP legislators would have been worse off under Chien’s plan.17 Moreover, it lumped together

unorthodox groupings of townships. Of the traditional seven county assembly districts,18 five

were split up, and one of the others was combined with a township connected only by a few mountain roads. Not only would this have thrown the DPP’s mobilization networks into disarray, ambitious county assembly members hoping to move up to the legislature in the future would

16 Compared with the LEC plan, 46.9% of the population would have moved to a new district in Chien’s plan.

17 Comparing his best districts in the LEC plan and Chien’s plan, Tsai Chi-chang’s 2004 vote share declined from 15.8% to 14.0%. Kuo Chun-ming went from 9.3% to 8.6%, and he would have been put in the district that was divided by mountains. Hsieh Hsin-ni went from 12.0% to 10.4%, and her best two townships, Taiping and Dali, would have been split up. The only winner was Wu Fu-quei, whose vote share would have increased from 15.0% to 18.2%. Wu would also have been a winner in the sense that his best district was the tossup district created in the Chien plan.

have found their supporters scattered into separate legislative districts. In short, most green camp politicians in the county would have found something to dislike about their new district.

The second proposal was much more modest. This change would have put Dali back together again, moving the 12,000 Dali residents shifted to D2 to meet the 15% guideline back into D3. This would have had almost no partisan impact and affected a mere 0.8% of the total population of Taichung County. In other words, this change would have been nearly irrelevant. In the end, neither the Speaker nor the Premier decided to support this change all the way to the lottery, but this proposal is typical of the minimal changes that did make it to the lottery in the other LEC dominant cases.

In sum, the complexity of Taichung County meant that the LEC’s position as first mover was a tremendous advantage. Once the LEC proposed a plan, the other side was not able to agree on a fundamentally different alternative. As a result, the LEC was able to secure significant partisan advantages for the local governing party.

3. Partisan Conflict

Three cities and counties experienced a third pattern, that of outright partisan conflict. As in the second pattern, the choice facing the LEC was not trivial. The LEC had substantively different alternatives to choose from and selected the one most advantageous to the local governing party. Unlike in the second pattern, in these three cases the other camp was able to settle on a fundamentally different alternative. Whereas the plans in the lottery in the second pattern differed by less than 4%, the alternatives in this pattern shifted 15-20% of the population to a new district.

The critical feature separating the second and third patterns was that, in the third pattern, the alternative plan did not significantly harm the interests of anyone in the local opposition camp. All the major stakeholders were either better off or indifferent. As seen in the second pattern, this is a significant threshold, and the difficulty of achieving this threshold increases with size. Perhaps it is not surprising that in two of the three cases in this category, there were effectively only two seats to be decided. Both Taichung City and Pingtung County were apportioned three seats, but in both cases, there was consensus on one of the seats. However, the third case demonstrates that complexity was not a deterministic factor. Taoyuan County had six seats, and there was a consensus around only one of these seats. That left five seats to fight over. Nevertheless, the DPP was able to converge on an alternate plan. The plan not only made

the DPP better off from the standpoint of the whole party, but more importantly, it did not make any incumbent substantially worse off.19 Thus, while generally speaking, the third pattern was

more likely to occur in medium sized cities and counties, this is a useful reminder that size is not a deterministic factor. The political skill needed to find plans that everyone in the camp could agree on also mattered.

Significantly, these three cases are arguably the three cases in which the LEC plans most overtly pursued partisan advantage. As noted above, the LEC plans in both Taoyuan County and Taichung City violated the CEC’s guidelines. The Pingtung LEC plan was within the CEC’s guidelines, but only barely (see Figure 3). The fact that these LEC plans were so overtly partisan may have played a role in helping the opposition to unite around an alternative plan.

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission.

Figure 3 Map of Pingtung County

19 The only DPP incumbent whose vote share in his best district declined under the DPP plan was Peng Tian-fu. However, this drop was very small, from 9.1% to 8.9%.

DPP plan districts township borders KMT plan D1 KMT plan D2 KMT plan D3 Pingtung City Wandan

The third pattern is illustrated with the case of Pingtung County (see Figure 3). Pingtung had a DPP local executive and was apportioned three seats. Both parties agreed on D3 in the southern part of the county, so the question was how to divide the northern part into the remaining two districts. The main controversy dealt with the more urban areas centered on Pingtung City and Wandan Township. These areas are more favorable to the blue camp than the rural areas, possibly because Pingtung’s Mainlander population is disproportionately located in the urban areas. The plan proposed by the LEC split the urban areas and combined them with surrounding rural areas to form D1 and D2. This created one district (D1) in which the DPP had a very small advantage, one (D2) in which it had a moderate advantage, and one (D3) in which it had a very large advantage. The partisan intent of this plan is clear from the uneven population distribution. The average district should have 281,126 people, and Pingtung City alone had 212,753. In an effort to negate the blue camp’s advantage in Pingtung City, the LEC plan added as many rural townships as possible to it to form D1. The result was a district that had 319,312 people, 13.6% over the mean, and a very slight green camp advantage. The LEC plan also helped the DPP by placing its incumbents in different districts (see Table 4).20

Table 4 Pingtung County Redistricting Plans

Population +/- Blue Camp Green Camp

KMT Plan D1 293,608 4.4 42.6 55.1 D2 278,875 -0.8 50.3 46.2 D3 270,896 -3.6 41.7 56.9 DPP Plan D1 319,312 13.6 47.8 48.8 D2 264,718 -5.8 44.5 53.3 D3 259,349 -7.7 41.5 57.0

Source: Data compiled by author from newspaper reports and Central Election Commission.

Notes: Total population=843,379; mean district population=281,126. The last two columns show the percentage of the vote won by all Blue and Green Camp candidates, respectively, in the 2004 legislative elections.

The CEC approved the LEC plan, but blue camp legislators proposed an alternative in the legislature. This plan, which I label the KMT plan, packed the urban areas together to form

20 Lin Yu-sheng was clearly stronger in D1 than in D2 (11.5% to 8.6%), and Cheng Tsao-min was clearly stronger in D2 than in D1 (13.0% to 10.4%).

one blue-leaning district (D2) and two districts with very large green majorities. Moreover, the KMT plan threw the DPP incumbents’ plans into disarray. Under the KMT plan, two DPP incumbents had roughly the same support levels in both D1 and D2.21 However, it is

not sufficient to demonstrate that the KMT plan was better for the blue camp as a whole; it is necessary to show that it was also better for all the major stakeholders. In 2004, the blue camp elected three legislators in Pingtung. One of these, Liao Wan-ju, was based in D3 and would have been indifferent to the two plans.22 Wu Jin-lin clearly benefitted under the KMT plan. Wu

was from Wandan township and enjoyed strong support in Pingtung City. The KMT plan put his best two areas together in a district (D2) that favored the blue camp.23 The third blue camp

incumbent, independent Tsai Hau, is the critical one. Tsai was based in D1, a district with a significantly larger green camp advantage in the KMT plan than in the LEC plan. There are two reasons that Tsai was happy with this arrangement, and both stem from the fact that he was an independent rather than a KMT member. On the one hand, Tsai had to worry about competition from the KMT. Because the blue camp was so weak in D1, the KMT was more willing to forego nominating its own candidate and to yield the district to Tsai. On the other hand, as an independent, Tsai was just as concerned about his own vote share, which increased from 14.0% in D1 in the LEC plan to 15.2% in D1 in the KMT plan, as he was about the overall blue camp vote share.

With the blue camp unanimously supporting the KMT plan and the green camp equally united around the LEC plan, there was no compromise to be found. The party leaders supported their respective plans all the way to the lottery, in which the KMT plan was chosen.

4. Implications for Future Redistricting Cycles

Many of the decisions made in 2005-2007 hinged on specific factors or conditions that may not always be present in future redistricting cases. This section explores what might be expected to happen if certain variables are altered. Above all, what would change if redistricting were conducted under unified government? Additionally, how might parties adapt to obtain better outcomes?

21 In D1 and D2, Lin had 10.8% and 9.6%, respectively. Cheng had 11.9% and 11.5% respectively. When the KMT plan won in the lottery, both Lin and Cheng declined to run for re-election.

22 Rather than run in the heavily pro-DPP D3, Liao managed to win a spot on the party list in 2008.

23 Wu eventually did not run for re-election. Instead, he took a position as Vice President of the Examination Yuan in the new Ma Administration.

The non-partisan guidelines set out in the CSERA and in the CEC’s directives clearly constrained decision-makers in the 2005-2007 round. In several cases, the population requirements and the need to respect township boundaries and historical or physical links made it difficult for politicians to come up with alternate plans, especially in the cities and counties with fewer seats. In the future, these constraints will be joined by another: the current legislative districts. Especially in cases in which the number of seats in the city or county does not change, the existing districts will be a powerful focal point. In addition to people being used to them, incumbents will have invested significant time and resources in building up personal votes along those boundaries.

Nevertheless, two factors might erode the power of these constraints. First, administrative reform in 2010 combined Taichung City and County, Tainan City and County, and Kaohsiung City and County, which collectively elect 22 of the 73 (30.1%) district seats. The new, bigger cities have more seats and more possible combinations of administrative districts. For example, consider Taichung. Whereas the old Taichung City and County had three and five seats, respectively, the new Taichung City has eight. Moreover, geography limited the choices in 2005-2007, since Taichung County wrapped around Taichung City (see Figure 2). There were not many possible ways to deal with Taiping, for example, since it is connected to the township to the east by only a few small mountain roads. In the future, Taiping might combined with one or more administrative districts from the former Taichung City. This added flexibility could mean significantly more choices, and that, in turn, could lead to more partisan conflict.

Second, the tradition of keeping groups of townships together might fade. There are no hard institutional rules that country assembly districts or other groups of townships have to stay together. They are held together by cultural ideas of what is natural and by politicians’ mobilization networks. If one party is disadvantaged because the other party has a politician with a potent mobilization network, it might want to break up such a grouping. Over time, parties could chip away at the cultural notions of which townships naturally belong together. This would effectively increase the number of building blocks and choices, which in turn might lead to more partisan conflict.

While the effect of guidelines would not be significantly affected by unified government, this would have a major impact on the composition of the decision-making bodies and their capacity to affect the final plan. In 2005-2007, the two major parties were on relatively even footing. The KMT controlled a few more local governments, but the DPP also held several cities