Towards an Integrated Content-Based Nursing

English Program: An Action Research Study

Hung-Chun Wang Mei-Ying Chuang

Hsin Sheng College of Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management Medical Care and Management rogerhcwang@hotmail.com cathy305@hotmail.com

Hui-Ching Yang

Tien-Hsin Chiu

Hsin Sheng College of Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management Medical Care and Management anita_yaung@hotmail.com halle123@seed.net.tw

Abstract

This study investigates the effectiveness of an integrated nursing English program administered in a junior college in Taiwan. The program was developed in order to integrate nursing education into general English education as a combined curriculum. The program was designed and administered to 370 second-year nursing majors by four language-trained teachers with little ESP (English for Specific Purposes) experience. Three major course themes were covered in the seven-week program, namely, Food Guide Pyramid, Hospital

Admission, and Parts of the Body & Health Problems. At the end of the program, an evaluation survey was given out to probe the learners’ opinions regarding the course design and content. Comments from a group of nursing teachers in a post-instruction seminar were also highlighted to draw out their perspectives on ways in which the program might be improved. Results of the survey indicated that the majority of learners evaluated the program satisfactorily and agreed that the program effectively enhanced their professional knowledge of nursing and four skills in English. The program was also successful in enhancing the students’ interest in learning English. This study may serve as a guide for EFL language-trained teachers to develop related nursing English programs.

Key Words: Nursing English Program, integrated program, action research

INTRODUCTION

English is a mandatory course and is part of the general education requirement in most Taiwanese technical universities. A growing appeal throughout the island in recent years, particularly to technical universities, has emphasized how general English education can facilitate learners’ learning of the subject knowledge in their academic content curriculum. The faculty of non-general education programs is often concerned about how general education can contribute to learning of subject knowledge. As for English education in technical universities, while general English often concentrates on development of language skills (Eslami, 2010), their concerns have led to the recent pedagogical transition of general English education toward more content-based teaching.

The integration of professional subject knowledge in language courses is known as content-based instruction (CBI), which has long been considered an effective approach in language education (Cammarata, 2009). As highlighted in Coyle (2002) and Kong (2009), language teachers may be categorized into language-trained teachers or content-trained ones. Language-trained teachers are often trained in “language teaching methodology and (are) knowledgeable about language and cultures,” while content-trained teachers are grounded in a school’s academic curriculum (Pessoa, Hendry, Donato, Tucker & Lee, 2007). In real classroom settings, it is difficult to find CBI instructors who have an equivalent level of knowledge in both academic content and the target language. When conducting CBI, language-trained teachers often encounter more problems owing to their lack of subject knowledge. The transition towards CBI in their

own teaching can even be a “professionally intimidating experience” (Cammarata, 2009, p. 559). Scaffolds are thus essential to help language-trained teachers facilitate their professional transition with ease, for instance, helping teachers reflect on their own teaching or having teachers work cooperatively (Cammarata, 2009).

Chen (2000) reports on her professional transition from a language-trained teacher towards an ESP (English for Specific Purposes) practitioner through self-training. To cultivate her ESP expertise in production and operations management (POM), she reflected on her teaching in the ESP classroom by keeping a diary, sitting in on a POM class to bolster her subject knowledge, and cooperating with a POM teacher through sharing observations of students’ learning. Her report indicates that a language-trained teacher, even without supervision or ESP experience, can self-train to become an ESP practitioner.

In response to CBI’s growing awareness about general education, an intercollegiate project sponsored by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan was undertaken by a northern/central/southern university in Taiwan (referred to as Y University hereafter) in January 2010, and part of the project aimed to investigate how to teach subject knowledge of nursing and English language skills in an integrated course. This project was administered in four universities and colleges across the island. In one of the target colleges where this study was conducted, four language-trained teachers were invited to develop an integrated content-based nursing English program on an experimental basis. Inspired by Chen’s (2000) self-training experience, they conducted this study by following an action research design.

teaching practitioners, such as teachers, principals, and counselors, to gain insights about various aspects of students, teachers, and the school system (Mills, 2011). As mentioned in Baumfield, Hall, and Wall (2008), it involves a cyclic process in the sense that a cycle of action research begins with problem definition and it encourages the teacher-researcher to address the problem by administering an action plan and eventually evaluating the effectiveness of the action plan through reflection and decisions. More specifically, action research is theoretically grounded in the dynamic interaction of three components in general: intention, process, and audience (Baumfield et al., 2008). Action research usually begins with the intention of a teacher-researcher to examine an issue or problem of interest, which can concern various aspects of students, colleagues, or the school. The teacher-researcher may work individually or cooperatively to decide on research questions that are directly related to his or her experience as a teacher in a school setting. Their enquiry has to stay “within their own domain as teachers” and is often aimed at addressing a practical issue (Baumfield et al., p. 15). In the process stage, the teacher-researcher employs different data collection tools (e.g., questionnaires and observations) and analytical methods (e.g., quantitative method) that can help address the issue. Lastly, action research concludes with the teacher-researcher presenting the findings and contributing to the reflective discussion with members in the “critical community,” which can include teachers and researchers in the same or other schools (p. 7). Moreover, reviewing Kemmis and McTaggart (1988), Baumfield et al. emphasize that insights and reflective thinking gained from the enquiry in a previous cycle of action research can often encourage the teacher-researcher to redefine

the problem and lead to the outset of another cycle of action research. Adopting the design of action research, the four language-trained teachers in this study worked cooperatively to investigate how teachers with little ESP teaching and learning experience could design and teach a content-based nursing English program regardless of their limited knowledge in the content domain. They set up a nursing English program, applied it to 370 nursing majors, and reported the program design to a group made up of nursing faculty in a post-instruction seminar. More importantly, they investigated the effectiveness of the program on the participants’ self-perceived growth in nursing knowledge, English skills, and learning interest. In sum, the study described in this article reports on the process in which the teachers developed the program, 370 participants’ perceptions regarding the design and evaluation of the program, and the nursing faculty’s comments on the program. The study was designed with a threefold purpose:

1. To report on the design and development of a nursing English program that aims to teach subject knowledge of nursing combined with English language skills;

2. To analyze the effectiveness of the nursing English program based on learners’ responses to the program evaluation survey;

3. To identify advantages and problems of the nursing English program from the perspective of the learners and nursing faculty.

LITERATURE REVIEW

English Needs in the EFL/ESL Medical Context

The issue of EFL (English as a Foreign Language)/ESL (English as a Second Language) students’ learning needs for ESP has been widely studied, and research in this direction is often directed at developing a curriculum that can better address learners’ needs (e.g., Bosher & Smalkoski, 2002; Chia, Johnson, Chia, & Olive, 1999; Shi, Corcos, & Storey, 2001). In an EFL context, Chia et al. (1999) studied Taiwanese college students’ perceptions of English needs in a medical context. They gave out a needs survey to 349 medical majors drawn from various years in a medical college to probe their perceptions toward the importance of English language use and skills needed in their studies or future career and their suggestions for developing an English language curriculum for incoming freshmen. Results of the survey indicated most respondents agreed that English was essential for their studies and their future career. Also, the most important subskill training needed for freshmen is the ability to understand conversations or lectures in English. To help succeed in a medical program, the majority of the respondents considered the ability to read textbooks an important skill to master. In addition, to most of them, an ideal curriculum is one that allows freshmen to concentrate on learning basic English skills, with course materials partly relevant to the medical context, as a bridge to elective ESP courses offered in higher years.

Empirical studies in ESL settings also demonstrate learners’ English learning needs for different subject fields, and for nursing or medical majors, oral communication skills are often deemed the most

essential in ESP education (e.g., Bosher & Smalkoski, 2002; Shi et al., 2001). Bosher and Smalkoski (2002), for example, explored the needs of a group of immigrant nursing majors in the United States, and they discovered that the most difficult and desirable skill is effective communication with clients and colleagues in the medical setting. They further designed a speaking and listening course aimed at enhancing learners’ oral communication skills for a health-care setting by shaping students’ skills including information-gathering techniques and demonstrating assertive communication. Their evaluation of the course also indicated the success of the course in shaping learners’ clinical communication skills.

The study by Shi et al. (2001) concentrated on the use of student performance data in clinical settings to develop a curriculum tailor-made for medical students in Hong Kong. By analyzing the students’ discursive interaction with experienced doctors during several ward-teaching sessions, Shi et al. identified essential diagnostic thinking skills and linguistic needs for medical majors in Hong Kong, including language support to present case histories, and describe or report examinations. Based on their analysis of the authentic data, the researchers further redesigned an existing course to address medical students’ required language skills, for instance, by discussing common clinical communication problems or rehearsing language skills in task-based role-plays. A course evaluation survey indicated that the program was deemed helpful and effective in many ways.

Focusing on the Integration of Subject Knowledge in English Courses

approach in second language education and it provides a channel for learners to learn the target language and reinforce their academic knowledge (Curtain & Haas, 1995; Curtain & Pesola, 1994). Content-based programs can also help “reinforce the existing school curriculum” (Pessoa et al., 2007, p. 103). Kasper’s (1994; 1997) and Song’s (2006) studies on CBI, for example, demonstrate the effect of content-based instruction on ESL learners’ academic progress. Focusing on a group of ESL students, Kasper (1997) intended to investigate the effect of CBI on those students’ academic performance at different stages, by comparing their post-instruction exams and graduate rates. He discovered that the experimental content-based group outperformed the control non-content-based group in many post-instruction exams, and in their progress to mainstream curriculum and graduation rate. Kasper thus concludes that implementing CBI can facilitate students’ current and subsequent academic performance. Similarly, Song (2006) tested the long-term effects of CBI on ESL learners’ future academic performance in university, and she also discovered that those who received CBI performed better than those who did not in many measures including their English proficiency test pass rates and graduation rates.

However, there have been different findings with regard to whether CBI can equally enhance students’ language skills and subject knowledge. An effective CBI, according to Pessoa et al. (2007), is one that can draw equal attention to language and content through conversation that enhances students’ ability to use and develop the language, as well as their understanding of metalanguage such as language forms. Although some research (e.g., Rodgers, 2006) has shown that CBI can effectively enhance learners’ content

knowledge and linguistic abilities, empirical studies (Dalton-Puffer, 2007; Pessoa et al., 2007; Stoller & Grabe, 1997) have also demonstrated the challenge for teachers to balance their pedagogical foci between language and content. In the study by Pessoa et al. (2007), their observations of two Spanish teachers demonstrated that one teacher felt it challenging to deal with both content and language. Also, Dalton-Puffer (2007) analyzed 40 CBI sessions for Grades 6-13 students who were taught in English and found that CBI teachers were often more concerned about content than language.

Another issue worth noting is that the pedagogical transition towards content-based teaching is never easy, particularly for language-trained teachers who often have limited knowledge of the target subject matter. In a content-based English course, the teacher may easily overemphasize the language and ignore the content or vice versa (Dalton-Puffer, 2007; Pessoa et al., 2007; Stoller & Grabe, 1997). Although the transition is a difficult process, Bosher and Smalkoski (2002) and Chen (2000) also highlight that language teachers can improve their setting of class objectives and teaching in ESP classes by gaining experience in the target subject field.

Grounded in the findings of empirical studies (e.g., Rodgers, 2006; Song, 2006) which show content-based instruction can facilitate academic learning and linguistic skills, the study described in this article aims to report on the process undertaken by four language-trained teachers. Those teachers developed an integrated, content-based nursing English program with emphasis on both language and content teaching. The study as an action research also examines the effectiveness of the program, reflecting on students’ learning experiences and nursing faculty’s perspectives.

METHODOLOGY

Mills (2011) proposes that the process of action research often engages the teacher-researcher in four different stages, namely, focus identification, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and development of an action plan. This section will present the major issue of enquiry and methods for data collection and analysis, with results of the data analysis discussed in the next section and suggestions for future curriculum development.

Participants

The participants were 370 college students drawn from eight classes in the second-year division of a nursing college in Taiwan. The students were all nursing majors aged around 17 and enrolled in a required three-credit second-year English course administered in the first three years at the school. Second-year students were selected because they had richer subject knowledge than the first-year students, as well as more weekly class meetings than third-year students. As a school-wide requirement, all 370 students took an English proficiency test measuring their listening and reading proficiency prior to the study. Adopted from General English Proficiency Test: Elementary-Level Mocked Tests (Kuo, 2009), the listening and reading tests were appropriate for testing the receptive language skills of students with three years of learning through junior high school. The listening section was comprised of 30 questions measuring learner listening skills in three areas, namely, Picture Question (10 items), Response to a Question (10 items), and Short Conversation (10 items), with each question being worth 4 points, resulting in a

total score of 120. Similarly, the reading section comprised three sections, namely Vocabulary and Structure (10 items), Cloze Test (10 items), and Reading Comprehension (10 items), and each question was also worth 4 points, resulting in a total of 120. On average, the participants’ listening proficiency (M = 77.08; SD = 15.92) was better than their reading proficiency (M = 60.09; SD = 13.61). The range of participants’ scores for each section was 16-120 for listening, 24-96 for reading, and 57-209 for the entire test, and it is reasonable to conclude that the participant group comprised learners of diverse English proficiency levels.

Table 1 shows the results of a biodata survey from the program evaluation survey employed in this study. Accordingly, the majority of the 370 participants were female students (n = 349, 94.32%), while the minority were male students (n = 21, 5.68%). As for their perceived English proficiency, most stated that their proficiency was acceptable or above (n = 282, 76.2%), while a smaller group indicated that their proficiency was poor or worse (n = 88, 23.8%). In addition, a much larger group of students mentioned that their interest in learning English was average or above (n = 348, 94.1%), while only a few students indicated their low interest in learning (n = 22, 5.9%).

Design of the Nursing English Program (NEP)

Initial reflection. English education has long been a

requirement for fulfilling general education in the target five-year college. When students enter college, they receive a three-year English education in order to develop their general English proficiency and daily communication skills.

Table 1

Results of the Biodata Survey

Participants Gender Male Female 21 349 (5.68) (94.32) Perceived Proficiency Very Poor

Poor Neutral Good Very Good 27 61 234 43 5 (7.3) (16.5) (63.2) (11.6) (1.4) Perceived Motivation Very Uninterested

Uninterested Neutral Interested Very Interested 2 20 216 110 22 (0.5) (5.4) (58.4) (29.7) (5.9)

Note. The number in parentheses shows the percentage.

These are important for them to pass either future entrance examinations for advanced study or English proficiency exams to get certificates that can boost their competitiveness in the job market. Having taught English to nursing majors for several years, one of the four teachers often questioned whether he was teaching the skills students really needed in the workplace. Teaching vocabulary about animals, sports, foods, and shopping seemed glaringly irrelevant and unrelated to nursing majors’ academic and professional needs.

A common complaint about students’ English proficiency from nursing faculty further indicated that a change was needed. When students finish their three-year English education, they may have adequate vocabulary and grammatical knowledge for survival in a foreign country, but oftentimes they struggle in their medical terminology classes where complicated words such as cholecystitis

and psychoanalysis may intimidate them. They have problems reading many of those words clearly, let alone memorizing them. Also, when students undertake their clinic training, there are often complaints about their problems understanding prescriptions written in English either by themselves or nursing supervisors. In this way, students’ learning in the first three-year general English program has often been called in question.

However, making a change is never easy. For language-trained teachers with little nursing knowledge, teaching nursing English was often a daunting challenge. Also, as highlighted in Cammarata’s (2009) study that appropriate CBI-based materials are less available, it is true that textbooks for nursing English on the market are often too difficult for EFL learners in Taiwan, and the lack of good teaching materials further made the change harder to make.

In January 2010, an intercollegiate project sponsored by the Ministry of Education was proposed by Y University to investigate how to integrate nursing education into general education. As invited by the host university, the four teachers as “seed teachers” of the target college participated in the project to design a nursing English program on an experimental basis. The four teachers (two male teachers and two female teachers), who are also the primary researchers in this study, were all language-trained teachers with little ESP teaching or learning experience. They all had experience teaching general English to nursing students for two to ten years. All of them hold a M.A. degree either in TESOL or Linguistics.

Planning the curriculum. As a requirement of the intercollegiate

project, the four teachers aimed to develop a nursing English program, apply it to students, and share with fellow teachers about its

effectiveness in an intercollegiate teacher seminar. A three-stage plan was adopted to develop a nursing English program, namely, (1) analysis of students’ learning and career needs, (2) selection of course materials, and (3) assessment of students’ academic performance (Figure 1). In the initial phase, in the face of the limited time they had before the program was scheduled to begin, they adopted a teacher-based analysis of learner needs to establish teaching objectives and select course themes based on their understanding of learners’ future career needs. Three course themes were eventually selected, namely, Food Guide Pyramid, Hospital Admission, and Parts of the Body & Health Problems. Food Guide Pyramid was selected because this topic may complement students’ learning in a two-credit Nutrition class they were taking at the time of the study. Hospital Admission and Parts of the Body & Health Problems were adopted as a response to the growing number of foreign visitors and laborers on this island, which also implies an increasing concern about nurses’ oral communication skills in assisting foreign patients in the clinical setting. Specific pedagogical objectives and the respective language and content foci of the three course themes are discussed in Appendix A. Generally speaking, by the end of the program, students were expected to be able to perform the following skills.

Language-Based Skills:

1. Understand words for foods in the six food groups;

2. Demonstrate appropriate communication skills when handling patients;

3. Read patient records in English, define abbreviated forms on the form, and use English to instruct patients to fill out patient records;

4. Understand vocabulary for different parts of the body and common health problems;

5. Give patients suggestions for common health problems and medicine-taking instructions in English.

Content-Based Skills:

1. Distinguish the six food groups and identify common foods in each group;

2. Understand the nutritional value, suggested daily intake of each food, and daily calorie intake for women/men;

3. Understand the responsibilities and important qualities of a hospital receptionist;

4. Distinguish remedies for common health problems; 5. Demonstrate dos and don’ts for taking medicine.

In the materials selection stage, the four teachers intended to find learning materials that align with the objectives of the program. Materials were drawn from a variety of sources for teaching EFL/ESL students nursing and medical English, including LiveABC’s 3-D Animated Dialogues: Life and Recreation (2009), Survival English (Viney, 2004), Oxford English for Careers: Nursing 1 (Grice, 2009), and other online resources. Selected materials were adapted and made into either separate handouts or PowerPoint slides, and students could have access to all materials on a password-protected school website.

The final stage of the program development pertains to assessment of students’ academic performance. In addition to regular class quizzes testing students’ vocabulary, two other measurements were employed, namely, a medical poster group project and a paper-and-pencil test on nursing English. For the poster group project,

groups of participants were required to design an English poster related to any topic in nursing, such as introducing hospital facilities as in the form of a picture dictionary or any first-aid step-by-step instruction like the Heimlich Maneuver. On the other hand, a paper-and-pencil test was developed to measure the participants’ linguistic and academic knowledge. Linguistically, it tested the ability to read patient records, medical dialogues, and a text about duties of a hospital receptionist. Academically, it assessed learners’ ability to categorize foods in the food pyramid, and to match remedies for different diseases. Figure 1

Program Development Procedure

Assessment of students’ academic performance Analysis of learner learning

and career needs

Selection of course materials

Identify learner needs and the objectives of the program.

Select appropriate teaching materials that can address the objectives.

Identify how to appropriately measure students’ academic performance in subject knowledge and English skills.

Evaluation survey of the Nursing English Program. A

program evaluation survey was administered to the participants in order to probe learners’ perceptions regarding the course design (see Appendix B). This survey was aimed at exploring the participants’ perceptions towards various aspects of the program design, including effectiveness on enhancing four English skills, nursing knowledge and learning interest. It was developed by the first author and reviewed by the others. The survey consisted of three major sections, namely, bio-data survey, course evaluation, and evaluation of the teaching themes. First, the bio-data survey asked questions related to the learner’s gender, self-perceived English proficiency, and motivation for learning English. The second section, course evaluation, consisted of nineteen questions regarding how well participants agreed the program helped improve their nursing knowledge, four skills, learning interest, and so on. All of the statements were evaluated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Strongly Disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Agree, to (4) Strongly Agree. Following this was evaluation of the teaching themes. This section consisted of six questions in total, with the first four questions tapping learners’ opinions regarding how well they were satisfied with the three themes discussed in the program. These four questions were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) Very Dissatisfied, (2) Dissatisfied, (3) Neutral, (4) Satisfied, to (5) Very Satisfied. Question 5, also evaluated on a five-point scale, pertained to learners’ opinions regarding whether enough time was allocated to the NEP. The last question of the survey investigated the necessity of integrating the Nursing English Program into general English education from the learners’ perspectives, and it was evaluated on a

four-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) Very Unnecessary, (2) Unnecessary, (3) Necessary, and (4) Very Necessary.

Data Collection Procedure

The program was administered to the participants as part of their course requirements in the general English courses. It started in the eleventh week in the spring semester of 2010, and lasted seven weeks (approximately 14 hours). Prior to the outset of the program, instruction was primarily based on a textbook. After the program started, the teachers spent one to two hours conducting the nursing English teaching in regular three-hour class meetings and the rest of the time on textbook teaching. In the final week, the program evaluation survey was given out to the participants to elicit their opinions regarding the design and content of the program. The survey was anonymously completed in a class meeting, and the response rate was 100%. In addition, a post-instruction seminar was hosted by the target college two weeks after the program ended in order for the four teachers to discuss the design of the nursing English program with nursing faculty. Comments elicited from the participating nursing faculty were analyzed to highlight possible improvements to the nursing English program.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in both quantitative and qualitative traditions. On the one hand, learner responses to the survey were analyzed by means of exploratory factor analysis and descriptive statistics to investigate the strength of learner agreement in several groups of statements. On the other hand, learner responses as

follow-up to questions 1 and 6 in the third section of the survey were presented qualitatively to examine reasons why they liked or disliked the course themes and why they agreed or disagreed with the integration of nursing and general English.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Course Evaluation

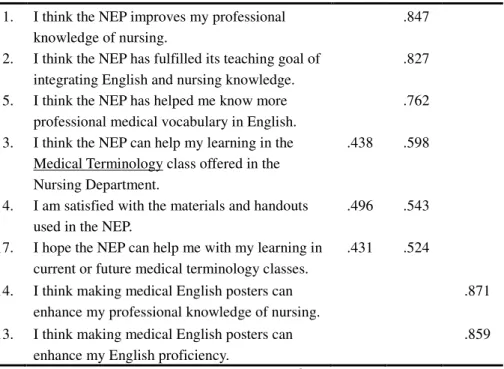

The 19-item course evaluation section of the survey was factor-analyzed through exploratory factor analysis using the Principle Component method of extraction. The scree plots indicate that three factors should be retained, with their eigenvalues greater than 1. Using the loading of .40 as the cutoff value, the analysis showed that seven items, i.e. items 3, 4, 11, 12, 16, 17, and 18, loaded on more than one of the factors and they were thus deleted and not included in our discussion. Table 2 demonstrates the rotated factor patterns of this survey, which also indicate that the remaining 12 items can be grouped in three factors, with 53.516% of total variance explained by the first factor, 6.797% by the second factor, and 5.731% by the third factor. First of all, items 7, 9, 8, 10, 6, 15, and 19 loaded on the first factor. These items primarily focused on learners’ perceptions toward different aspects of English learning, such as the four skills and learning interest, so the first factor was labeled as “Perception toward English Learning.” Secondly, items 1, 2, and 5 loaded on the second factor. These three items primarily emphasized the learning of nursing knowledge and its integration with English. The second factor was labeled as “Perception toward Nursing and its

Integration with English.” Lastly, items 14 and 13 loaded on the third factor. These two items primarily explored the participants’ perceptions toward the activity of designing medical English posters, thus the third factor was labeled as “Perceptions toward Designing Medical English Posters.”

Table 2

Rotated Factor Patterns of the Course Evaluation Survey

Item FIa FIIb FIIIc

7. I think the NEP has enhanced my oral communication skills.

.784

9. I think the NEP has enhanced my reading proficiency in English.

.770

8. I think the NEP has enhanced my listening proficiency in English.

.760

10. I think the NEP has enhanced my interest in learning English.

.707

6. I think the NEP has familiarized me with more grammatical patterns in English.

.703

18. Speaking overall, I am satisfied with the course content covered in the NEP.

.673 .403

15. I like the NEP more than learning based on the textbook before the midterm.

.653

19. I hope my English class in the third year can be still oriented to the NEP.

.633

12. I think we have enough time for practice in class.

.589 .452

11. I think the NEP is rich in its content. .537 .434 16. I think the NEP achievement test (that is, the

final exam) should assess both English and the professional knowledge of nursing that students learn in the NEP.

1. I think the NEP improves my professional knowledge of nursing.

.847

2. I think the NEP has fulfilled its teaching goal of integrating English and nursing knowledge.

.827

5. I think the NEP has helped me know more professional medical vocabulary in English.

.762

3. I think the NEP can help my learning in the Medical Terminology class offered in the Nursing Department.

.438 .598

4. I am satisfied with the materials and handouts used in the NEP.

.496 .543

17. I hope the NEP can help me with my learning in current or future medical terminology classes.

.431 .524

14. I think making medical English posters can enhance my professional knowledge of nursing.

.871

13. I think making medical English posters can enhance my English proficiency.

.859

Note. N = 370; NEP = nursing English program. aFI = Perception toward English learning; bFII = Perception toward nursing knowledge and its integration with

English; cFIII = Perceptions toward designing medical English posters.

Table 3 indicates the results of the course evaluation survey, which tapped the participants’ perceptions of the course content in the nursing English program. First of all, as for the participants’ perceptions toward the effectiveness of the program on various aspects of English learning, the participants expressed a rather positive attitude toward the effectiveness of the program. They agreed that the design of the NEP enhanced their English proficiency in areas such as listening and reading and their learning interest. Further, as shown in item 19, the participants in general hope that their third-year English class can be also directed at the NEP. Nevertheless, item 15, resulting in the lowest mean score and the highest standard deviation,

implies agreement with the statement was more variable. While 72.2% of the participants preferred the NEP to textbook teaching that features general English training, another 27.8% favored textbook-based learning (see Appendix B). This indicates that the NEP as a content-based ESP program was not fully accepted by all the participants.

Second, with respect to the participants’ perceptions toward the effectiveness of the program on their growth in nursing knowledge and medical English, as indicated in questions 2, 5, and 1, the NEP successfully integrated nursing knowledge into English classes, developing the participants’ English and nursing knowledge at the same time. Lastly, with regard to the participants’ reactions to the activity of designing medical English posters, the results for questions 13 and 14 indicate that most of the participants agreed that making medical English posters enhanced their English proficiency (83.6%) and professional knowledge of nursing (83.0%).

Evaluation of the NEP Course Content

The third section of the questionnaire consisted of six questions mainly dealing with learners’ degree of satisfaction toward the three content themes administered in the NEP. The first four questions, evaluated on a 5-point scale ranging from (1) Very unsatisfied to (5) Very satisfied, tapped learners’ perceptions regarding the theme selection as a whole or individually. As shown in Table 4, the means of learner responses ranging from 3.58 to 3.75 indicated above-average satisfaction in the selection (cronbach’s α = .87).

Table 3

Statistical Results of the Course Evaluation

Factor/Statement M SD

I. Perception toward English Learning

9. I think the NEP has enhanced my reading proficiency in English.

3.06 .60

6. I think the NEP has familiarized me with more grammatical patterns in English.

3.05 .59

19. I hope my English class in the third year can be still oriented to the NEP.

3.01 .71

8. I think the NEP has enhanced my listening proficiency in English.

3.00 .61

7. I think the NEP has enhanced my oral communication skills.

2.97 .63

10. I think the NEP has enhanced my interest in learning English.

2.97 .68

15. I like the NEP more than using learning based on the textbook before the midterm.

2.86 .76

II. Perception toward Nursing and its Integration with English 2. I think the NEP has fulfilled its teaching goal of

integrating English and nursing knowledge.

3.21 .49

5. I think the NEP has helped me know more professional medical vocabulary in English.

3.21 .52

1. I think the NEP improves my professional knowledge of nursing.

3.20 .49

III. Perceptions toward Designing Medical English Posters 13. I think making medical English posters can enhance my

English proficiency.

3.01 .65

14. I think making medical English posters can enhance my professional knowledge of nursing.

Question 5 further explores learner perceptions concerning the time allocation for the NEP, and it was evaluated on a 5-point scale ranging from (1) Very insufficient to (5) Very Sufficient. According to the results, 87% of the participants indicated an average acceptable level or above, while 13% thought it was inadequate. In addition, question 6, which was evaluated on a four-point scale ranging from (1) Very unnecessary to (4) Very necessary, intended to elicit learners’ opinions regarding the necessity of integrating nursing and English learning. Results show that 326 (88.1%) of the participants agreed that the integration was (very) necessary, while only 44 (11.9%) disapproved of the integration.

Focusing on question 1 specifically, the researchers further aimed to investigate the reasons behind learners’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the three course themes. For this purpose, the researchers categorized all the responses elicited as a follow-up to question 1 and categorized them into two major categories, namely, reasons for satisfaction and reasons for dissatisfaction. First of all, regarding the reasons for satisfaction, 97 responses were elicited. Table 5 shows that the reasons most participants agreed upon pertain to the fact that the three course themes were deemed meaningful, practical and useful to the participants’ clinical training and future profession. Also, many participants stated that the three themes helped develop their vocabulary, oral communication skills with patients, and nursing knowledge. Many also believed the course themes had a great impact on reviewing their nursing knowledge. On the other hand, the 21 objecting responses are mostly related to the view that the course content was incomprehensible, or was too easy or limited in its content and time allocation (see Table 6).

Table 4

Results of the Individual Evaluation of NEP Course Content

M SD

(4) How do you evaluate your satisfaction with the teaching content and materials selection for Parts of the Body & Health

Problems?

3.75 .75

(3) How do you evaluate your satisfaction with the teaching

content and materials selection for Hospital Admission? 3.71 .77 (2) How do you evaluate your satisfaction with the teaching

content and materials selection for Food Guide Pyramid? 3.63 .75 (1) Speaking overall, how satisfied are you with the selection of

the three course themes (food guide pyramid, hospital admission, and parts of the body & health problems)?

3.58 .75

(5) Speaking overall, do you think that allocating one to two hours

for the Nursing English Program is sufficient? 3.30 .83 (6) Do you think that General English education should integrate

nursing English teaching? 3.01 .53

Table 5

Categorized Learner Responses Supporting the Integration

Category Description of categorized responses NP (1) It is meaningful/practical/useful to our clinical training

and future profession in the hospital.

26 (2) I learned new vocabulary/phrases/sentence

patterns/dialogues/medical vocabulary/oral communication skills (with patients).

26

(3) It helps me develop my professional nursing/medical knowledge or review what I learn in medical classes.

20 (4) It helps me understand more knowledge / many

important things / that I am not usually in contact with.

10

(5) Simply very satisfied/interesting/great/good/ 7 (6) Not very difficult. Vocabulary is not too hard. 2

(7) Miscellaneous 6

Table 6

Categorized Learner Responses Rejecting the Integration

Category Description of categorized responses NP (1) I didn’t understand at all. / It’s hard to understand. / It’s

difficult.

9 (2) The content is too simple/ not rich enough / quite

limited.

3

(3) Time is insufficient. 3

(4) There is too much content. 2

(5) Miscellaneous 4

Further, learners’ responses to question 6 were also scrutinized in order to elicit the reasons why the participants supported or rejected the integration of nursing into English classes. From the 326 consenting participants, 111 responses indicated reasons for support. Table 7 shows the consenting learner responses. The reasons that most participants agreed upon pertain to the opinion that the program was deemed practical, helpful, and useful to their clinical training, other professional classes, and future nursing career. A number of responses were directed at the increased learning of English, nursing knowledge, nursing English, or medical terminology. Also, the program was believed to review or complement the participants’ learning in other nursing classes so they could develop their English proficiency and nursing knowledge at the same time. Moreover, many participants agreed that the program enhanced their professional nursing knowledge and skills directly or cultivated their oral communication skills in the workplace. In addition, other miscellaneous responses included the effectiveness of the program in enhancing the participants’ competitiveness in the job market.

In contrast, as shown in Table 8, reasons for rejecting the integration mostly concern the limited content in the NEP. Eight students responded that English classes should not teach about nursing but rather should teach about real-life issues, helping students improve their communication skills and overall English proficiency. If they learn about nursing in English classes, they are afraid that they are not learning English. Also, five participants stated that the program fatigued and troubled them, making it hard to digest the content. Furthermore, several responses indicated that English classes in the general English program should focus on developing learners’ grammatical knowledge, laying a foundation needed for their medical terminology or other medical English classes. Others pointed out that integration was unnecessary since vocabulary comprising a portion of their English classes had already been covered during their professional training; they wanted English classes to focus on English, not nursing.

Table 7

Categorized Learner Responses Supporting the Integration

Category Description of categorized responses NP (1) It is practical/helpful/useful to our clinical training, other

professional classes/training, and future nursing career.

37 (2) We can learn more and widely (as nursing majors). / We can

learn more English/nursing knowledge/nursing English/medical terminology.

27

(3) The NEP helps review/complement our learning in nursing classes. / We can develop our English and nursing knowledge at the same time. / English and nursing are related and applicable to both.

20

(4) It enhances our professional nursing/medical skills and knowledge. 13 (5) Daily and medical conversations are important to medical staff. 3 (6) Learning English as a second/international language is very

important.

2

(7) Simply great / very satisified 2

Table 8

Categorized Learner Responses Rejecting the Integration

Category Description of categorized responses NP (1) English classes should not be limited to nursing training

and should be broad enough to cover real-life issues such as daily conversation.

8

(2) I feel troublesome/tired/frustrated/hard to digest the content.

5 (3) My English grammar is poor and needs improving in

regular English classes. / We can’t communicate with medical terms without knowing how to use grammar. / English classes should lay the essential foundation for medical/nursing English.

5

(4) NEP is not necessary since we already have medical terminology classes. / Nursing classes teach nursing and English classes teach English. / Nursing training is already covered in other nursing classes.

4

(5) Miscellaneous 3

Pedagogical Suggestions from Nursing Teachers

A post-instruction seminar was hosted by the school authority in which the four teachers reported on the design of the NEP to a group of faculty including 12 teachers from the nursing department. This face-to-face conference was a valuable channel for the four teachers to understand whether the design of the integrated program addressed nursing faculty’s expectations. The 12 teachers of nursing generally expressed positive responses to the innovative design of English classes catering to nursing majors. Nevertheless, the comments from nursing faculty were mostly directed at how effectively the nursing English program can equip learners with adequate English skills they need to facilitate learning in other nursing courses, rather than how much more the students know about

nursing after the program.

Their comments can be generally categorized into three areas, namely, emphasis on English pronunciation, vocabulary teaching, and materials selection. First of all, the nursing faculty emphasized that English classes should improve students’ pronunciation and phonetic knowledge, particularly linking sounds and consonant clusters like ph, th, sh, and ch. As highlighted in their responses, many nursing majors have problems pronouncing these sounds, and thus can not read medical terminology clearly. Second, teaching medical terminology and English affixation was considered an essential objective of the program. Several teachers stated that English courses should cover some medical terminology, and crucially, important prefixes and suffixes in English such as psycho- (meaning mind) in psychology and psychiatrist, and hydro- (meaning water) in hydronephrosis and hydropathy. Third, particularly regarding the teaching materials, their comments pointed out that the selection of course materials can be improved by increasing the difficulty level and broadening the issues discussed in the program. To sum up, it seems that pedagogical suggestions from the nursing faculty focus on how effectively the nursing English program can enhance learners’ English abilities to succeed in their English-related nursing courses such as Medical Terminology.

DISCUSSION

This study aims to examine the effectiveness of a content-based nursing English program in which the teachers combined the

instruction of nursing and English language skills. According to Curtain and Haas (1995) and Curtain and Pesola (1994), the main pedagogical emphasis of content-based instruction is to help learners develop their language skills and subject knowledge combined. Based on the 370 learners’ responses to the program evaluation survey, our content-based nursing English program has fulfilled this pedagogical objective. Analyzing learner responses has revealed agreement among most participants that the program was practical and useful to their learning and clinical training. The program also had a complementary effect, reinforcing learners’ subject knowledge of nursing and facilitating what they had learned in other academic content courses. This further echoes Rodger’s (2006) finding that CBI can promote learning in both academic content and language skills.

However, although the program was largely successful in cultivating most learners’ language skills and academic content knowledge, it is also undeniable that a small group of learners failed to follow the program. Their failure may be attributed to their inexperience in joining a content-based English course or their low English proficiency level. This result also underscores the fact that, while a pedagogical transition toward ESP is quick and often considered necessary, not every student can follow the transition. On the other hand, the finding of Chia et al. (1999) indicated that most medical students expected their first-year English class to concentrate on training of basic English skills with some medical English input, as an academic bridge preparing them for other ESP-oriented courses in higher years. Likewise, several learners in this study also responded that general English classes should emphasize the training of basic language skills to equip them with essential linguistic

knowledge they need to pursue success in future ESP courses. Based on these results, this study further reveals a potentially important question that needs to be pursued in future research: When is the best time for students to begin their ESP education? While teachers need time and education to get them ready for the pedagogical transition toward ESP, learners may also need time to become linguistically prepared for ESP.

As indicated in some participants’ responses, the program was limited in its management of the balance between content and language teaching. Some students thought that the program might have lost its pedagogical focus on language, making them feel that they were not learning the language. This confirms the findings of Stoller and Grabe (1997), Pessoa et al. (2007) and Dalton-Puffer (2007), that CBI instructors often find it hard to maintain a balance between content and language, and so CBI was often vulnerable to loss of its language-learning focus. On the basis of these results, as highlighted in Cammarata (2009), while language-trained teachers are making their pedagogical transition toward ESP, they may need scaffolding from professional teacher-training programs or support from other English teachers and nursing faculty with regard to how to design or teach a content-based ESP program.

In addition, to complement Chen’s (2000) study, this study has indicated that language-trained teachers could train themselves to be ESP practitioners through cooperation. Their experience working cooperatively provides an example of how language-trained teachers with little nursing knowledge can shift their teaching toward ESP. This is particularly important in an EFL country like Taiwan, where there is a growing need for ESP education, and where many English

teachers are language-trained with limited knowledge in other professional subject domains. The present study can thus serve as a guide for EFL language-trained teachers to develop a nursing English program to align with the growing needs for ESP education.

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

In conclusion, this study as an action research illustrates the process in which four language-trained teachers cooperated to develop an integrated content-based nursing English program. It further stresses the idea that nursing English can be integrated into a regular general English course, and the integration is helpful to and welcomed by most of the EFL learners. However, this study has several limitations, and these indicate issues to be pursued in future research. First of all, course themes were selected by the four teachers based on their own analysis of learners’ future career needs, rather than depending on the participants’ learning needs and interests. Future research may take learner needs into greater consideration by conducting a needs analysis survey so that the program can be truly tailor-made for students.

Second, Baumfield et al. (2008) mentioned that insights gained from a cycle of action research may encourage the teacher-researcher to redefine the problem and to take a further step to plan another cycle of action research to address the problem. This study only presents one cycle of action research and does not indicate how the four teacher-researchers address the problems they encountered and the suggestions they received from the participants and the nursing

faculty by designing another nursing English program. Nevertheless, it is hoped that the findings presented in this study can draw ESP teachers’ attention to some suggestions for developing nursing English programs, and also result in more action research to be conducted as a follow-up cycle.

Lastly, EFL teachers often have limited subject knowledge for CBI (Cloud, 1998), and the weaknesses of the program as highlighted in the post-instruction seminar by the nursing faculty also pointed out the importance of having nursing professionals join the team of course development. Ideally, many weaknesses would have been spared if there had been nursing professionals working or commenting on the program design prior to its implementation. Future research focusing on developing a content-based nursing English program should thus recruit several nursing faculty for help with the design. If nursing faculty are involved in the process of curriculum development, they can give immediate responses to the course content to maximize the benefits of the content-based ESP program. Support from nursing faculty may also turn many language-trained teachers’ “professionally intimidating [ESP] experience” (Cammarata, 2009, p. 559) into a good and fruitful journey.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The design of the nursing English program was initially presented at the inter-collegiate teacher seminar entitled Developing Nursing-based General Education Curriculum, with partial findings

of this study orally presented at the 2010 Conference on Improving Teaching and Research Quality of General Education hosted by Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments on the previous drafts of this article.

REFERENCES

Baumfield, V., Hall, E., & Wall, K. (2008). Action research in the classroom. London: Sage Publications.

Bosher, S., & Smalkoski, K. (2002). From needs analysis to curriculum development: Designing a course in health-care communication for immigrant students in the USA. English for Specific Purposes, 21, 59-79.

Cammarata, L. (2009). Negotiating curricular transitions: Foreign language teachers’ learning experience with content-based instruction. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 65(4), 559-585.

Chen, T.-Y. (2000). Self-training for ESP through action research. English for Specific Purposes, 19, 389-402.

Chia, H.-U., Johnson, R., Chia, H.-L., & Olive, F. (1999). English for college students in Taiwan: A study of perceptions of English needs in a medical context. English for Specific Purposes, 18(2), 107-119.

Cloud, N. (1998). Teacher competencies in content-based instruction. In M. Met (Ed.), Critical issues in early second language training: Building for our children’s future (pp. 113-124).

Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman/Addison-Wesley.

Coyle, D. (2002). Against all odds: Lessons from content & language integrated learning in English secondary schools. In D. W. C. So & G. M. Evans (Eds.), Education and society in plurilingual contexts (pp. 37–55). Brussels: VUB Brussels University Press. Curtain, H., & Haas, M. (1995). Integrating foreign language and

content instruction in grades K-8. Retrieved August 19, 2010, from http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/int-for-k8.html

Curtain, H., & Pesola, C. A. B. (1994). Languages and children: Making the match. Foreign language instruction for an early start grades K-8. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Eslami, Z. R. (2010). Teachers’ voice vs. students’ voice: A needs analysis approach to English for academic purposes (EAP) in Iran. English Language Teaching, 3(1), 3-11.

Grice, T. (2009). Oxford English for careers: Nursing 1. NY: Oxford University Press.

Kasper, L. F. (1994). Improved reading performance for ESL students through academic course pairing. Journal of Reading, 37, 376-384.

Kasper, L. F. (1997). The impact of content-based instructional programs on the academic progress of ESL students. English for Specific Purposes, 16(4), 309-320.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner. Geelong: Deakin University.

content-trained teachers’ and language-trained teachers’ pedagogies? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 66(2), 233-267.

Kuo, B. (Ed.). (2009). General English Proficiency Test: Elementary-level Mocked Tests

(全民英檢初級模擬試題)

. Taipei: SanMin Bookstore.LiveABC’s 3-D animated dialogues: Life and recreation (2009). Taipei: LiveABC Interactive.

Mills, G. E. (2011). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Pessoa, S., Hendry, H., Donato, R., Tucker, G. R., & Lee, H. (2007). Content-based instruction in the foreign language classroom: A discourse perspective. Foreign Language Annals, 40(1), 102-121.

Rodgers, D. M. (2006). Developing content and form: Encouraging evidence from Italian content-based instruction. The Modern Language Journal, 90(3), 373-386.

Shi, L., Corcos, R., & Storey, A. (2001). Using student performance data to develop an English course for clinical training. English for Specific Purposes, 20, 267-291.

Song, B. (2006). Content-based ESL instruction: Long-term effects and outcomes. English for Specific Purposes, 25, 420-437. Stoller, F. L., & Grabe, W. (1997). A six-T’s approach to content-based

instruction. In M. A. Snow & D. M. Brinton (Eds.), The content-based classroom: Perspectives on integrating language and content. White Plains, NY: Addison-Wesley Longman.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Hung-Chun Wang holds an MA degree in TESOL from National Kaohsiung Normal University, and he is currently a PhD candidate on the TESOL program at National Taiwan Normal University. He teaches at Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management, Taiwan. His research interests include second language acquisition and discourse analysis.

Mei-Ying Chuang holds an MA degree in TESOL from Long Island University, New York. She teaches at Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management, Taiwan.

Hui-Ching Yang holds an MA degree in TESOL from Long Island University, New York. She teaches at Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management, Taiwan.

Tien-Hsin Chiu holds an MA degree in Linguistics from National Chung Cheng University, Taiwan. He teaches at Hsin Sheng College of Medical Care and Management, Taiwan.

APPENDIX A

Description of the Three Course Themes

Topic Time Objective Language/Content focus Food Guide

Pyramid

4 hrs Learn about names of foods in the six food groups and the nutrition value and suggested daily intake of each food

Language

· Vocabulary about food and food groups Content

· Healthy and unhealthy food types

· Suggested daily intake of foods

· Daily calories needed for women/men

· Classification of food types Hospital

Admission

6 hrs Learn about the responsibilities of a hospital receptionist and easy-to-use English communication skills when handling patients. Learn to read patient records written in English and to use English to instruct patients to fill out patient records

Language

· Reading texts about responsibilities and

qualities of a hospital receptionist

· Vocabulary about personality and jobs

· Dialogues in medical context including buying medicine and registering

· Abbreviated forms on a patient’s record

Content

· Responsibilities and qualities of a hospital

receptionist

· Learning to read patient records in English Parts of the Body & Health Problems 4 hrs Learn about English vocabulary for different parts of the body, common health problems and suggestions for health problems, English instructions for taking medications Language

· Explaining health problems in English

· Vocabulary about parts of the body, health

problems, remedies, and medicine taking

instruction Content

· Dos and don’ts when taking medications

APPENDIX B

English Translation of the Program Evaluation Survey

A. Biodata survey: (Please check)

1. Class: _________________

2. Sex: □ Female (94.32%) □ Male (5.68%)

3. Of all the students in your class, you think your English proficiency is: □ Very Poor (7.3%) □ Poor (16.5%) □ Neutral (63.2%)

□ Good (11.6%) □ Very Good (1.4%)

4. How do you evaluate your motivation for learning English:

□ Very Uninterested (0.5%) □ Uninterested (5.4%) □ Neutral (58.4%) □ Interested (29.7%) □ Very Interested (5.9%)

B. Course evaluation:

Statement SD D A SA

1. I think the NEP improves my professional knowledge of nursing.

1 (0.3) 11 (3.0) 270 (73.0) 88 (23.8)

2. I think the NEP has fulfilled its teaching goal of integrating English and nursing knowledge.

1 (0.3) 11 (3.0) 267 (72.2) 91 (24.6)

3. I think the NEP can help my learning in the Medical

Terminology class offered in the Nursing Department.

2 (0.5) 34 (9.2) 251 (67.8) 83 (22.4)

4. I am satisfied with the materials and handouts used in the NEP.

3 (0.8) 28 (7.6) 265 (71.6) 74 (20.0) 5. I think the NEP has helped me

know more professional medical vocabulary in English.

2 (0.5) 13 (3.5) 260 (70.3) 95 (25.7)

6. I think the NEP has familiarized me with more grammatical

patterns in English.

7. I think the NEP has enhanced my oral communication skills.

3 (0.8) 70 (18.9) 233 (63.0) 64 (17.3) 8. I think the NEP has enhanced

my listening proficiency in English.

5 (1.4) 55 (14.9) 246 (66.5) 64 (17.3)

9. I think the NEP has enhanced my reading proficiency in English.

5 (1.4) 42 (11.4) 250 (67.6) 73 (19.7)

10. I think the NEP has enhanced my interest in learning English.

10 (2.7) 62 (16.8) 227 (61.4) 71 (19.2) 11. I think the NEP is rich in its

content.

3 (0.8) 32 (8.6) 255 (68.9) 80 (21.6) 12. I think we have enough time for

practice in class.

8 (2.2) 73 (19.7) 238 (64.3) 51 (13.8) 13. I think making medical English

posters can enhance my English proficiency.

8 (2.2) 53 (14.3) 237 (64.1) 72 (19.5)

14. I think making medical English posters can enhance my professional knowledge of nursing.

6 (1.6) 57 (15.4) 233 (63.0) 74 (20.0)

15. I like the NEP more than learning based on the textbook before the midterm.

17 (4.6) 86 (23.2) 200 (54.1) 67 (18.1)

16. I think the NEP achievement test (that is, the final exam) should assess both English and the professional knowledge of nursing that students learn in the NEP.

5 (1.4) 33 (8.9) 263 (71.1) 69 (18.6)

17. I hope the NEP can help me with my learning in current or future medical terminology classes.

1 (0.3) 13 (3.5) 267 (72.2) 89 (24.1)

18. Speaking overall, I am satisfied with the course content covered in the NEP.

5 (1.4) 35 (9.5) 264 (71.4) 66 (17.8)

19. I hope my English class in the third year can still be oriented to the NEP.

12 (3.2) 54 (14.6) 221 (59.7) 83 (22.4)

C. Evaluation of individual course themes:

1 Speaking overall, how satisfied are you with the selection of the three course themes (food guide pyramid, hospital admission, and parts of the body & health problems)?

□ Very dissatisfied (1.4%) □ Dissatisfied(1.6%) □ Neutral (44.9%)

□ Satisfied (42.2%) □ Very Satisfied (10.0%)

Please specify your reason: _________________________________________ 2 How do you evaluate your satisfaction with the teaching content and materials

selection for Food Guide Pyramid?

□ Very dissatisfied (0.5%) □ Dissatisfied(2.4%) □ Neutral (43.0%)

□ Satisfied (41.4%) □ Very Satisfied (12.7%)

3 How do you evaluate your satisfaction with the teaching content and materials selection for Hospital Admission?

□ Very dissatisfied (0.3%) □ Dissatisfied(2.7%) □ Neutral (38.6%)

□ Satisfied (42.7%) □ Very Satisfied (15.7%)

4 How do you evaluate your satisfaction with the teaching content and materials selection for Parts of the Body & Health Problems?

□ Very dissatisfied (0.3%) □ Dissatisfied (2.2%) □ Neutral (35.9%) □ Satisfied (45.9%) □ Very Satisfied (15.7%)

5 Speaking overall, do you think that allocating one to two hours for the Nursing English Program is sufficient?

□ Very insufficient (2.2%) □ Insufficient (10.8%) □ Neutral (48.6%)

□ Sufficient (31.6%) □ Very Sufficient (6.8%)

6 Do you think that General English education should integrate nursing English teaching in it?

□ Very unnecessary (0.8%) □ Unnecessary (11.1%) □ Necessary (74.1%) □ Very Necessary (14.1%)