Luor, T., Lu, H.-P., Tao, Y.-H., Lin, T. M. Y. and Tung, C.-H., Determinants of client intention of software outsourcing vendors - A model from Taiwan's financial industry , Annual Meeting of International Academy of Business and Economics Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, Oct. 19-22, 2008.

Determinants of Client Intention of Software Outsourcing Vendors: A Model from Taiwan’s Financial Industry

Ted (Tainyi) Luor

Graduate school of Management, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC

Information Department, International Bill Finance Corporation, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC. E-mail: a384@ibfc.com.tw

Hsi-Peng Lu

Professor, Department of Information Management National Taiwan University of Science & Technology, ROC.

E-mail: hsipeng@cs.ntust.edu.tw

Yu-Hui Tao1

Professor, Department of Information Management National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan, R.O.C.

E-mail: ytao@nuk.edu.tw

TomM. Y.LIN

Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC.

E-mail: tomlin@ba.ntust.edu.tw

Tung Chi-Hsiang

Information Department, International Bills Finance Corporation, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC. E-mail: a526@ibfc.com.tw

ABSTRACT

While many studies have focused on information software (IS) outsourcing, little is known about the determinants influencing clients’decision on IS outsourcing vendors. This article explores the relationships among client beliefs, factors, and intention, which determine their associations with IS outsourcing vendors in the financial industry—a relatively conventional industry with a preference for rule-regulated and structured activities. Ten factors influencing the decision of outsourcing vendors are first classified into four belief groups; then a simple model explaining client intention and preferences with respect to outsourcing is presented using the Correlation Analysis. Interviews with participants are also conducted to collate information during the classification process. By systematically discussing factors and attempting to bridge the gap between theory and practice, this article presents certain useful findings to theorize the association between IS clients and vendors for Taiwan’s financial industry.

Keyword: information system, outsourcing, security, belief, trust

INTRODUCTION

The volume and range of services being outsourced have notably increased in recent years (Gonzalez, Gasco, and Llopis, 2006). In fact, the study of outsourcing has progressively increased since its early start in the 1960s (Gonzalez et al., 2006). In practice, many companies have been choosing IS outsourcing in response to complicated information systems (IS) and various internal requirements. In literature, many studies focused on IS or Information Technology (IT) outsourcing provide fruitful references for suppliers to formulate their methodologies and strategies for successful IS implementations (Yusufa et al., 2004). A successful IS outsourcing relationship can help outsourcing clients to achieve benefits such as cost-savings, increased flexibility, better quality services, and acquisition of new technology. However, there is little theoretically sound and formal knowledge about the determinants that influence a clients’decision on IS outsourcing vendors. Therefore, it would be a perfect supplement to the existing literature and IS outsourcing suppliers for providing a formal model uncovering the determinants influencing the client’s intention to use an IS outsourcing vendor.

The banking and thrift industries are undergoing a technological metamorphosis (Zhu, Scheuermann, and Babineaux, 2004). This venture has attracted considerable attention and speculation in both the financial and IT communities. In addition, in 2003, expenditures for outsourcing information services totaled USD$500 million, a 14% increase over the previous year. In terms of the types of outsourcing jobs, the services engaged were still mainly software development and maintenance, which accounted for 55.03% of all services (Taylor and Todd,

1995). This paper studies the IS outsourcing factors in the financial industry—a relatively conventional industry with a preference for rule-regulated and structured activities.

The financial industry is an information-intensive industry in which information technology (IT) is becoming increasingly important. Take Taiwan for example. The financial institutions are facing dual competitive pressure in the areas of service quality and administrative efficiency (DGBAS, 2007). Taiwan has also been rated as having a high-performance orientation—the degree to which a society encourages and rewards group members for performance improvement and excellence (Javidan and House, 2001). In 2003, a total of USD$4.2 billion was expended on ITs in the nation, indicating a 25.33% increase over the previous year and accounting for 1.3% of the GDP. In terms of the ratio of information expenditure to total capital, the financial industry, including the banking and insurance industry, ranked as the second largest buyer of ITs (accounting for 16.57% of the total amount), after the manufacturing industry (20.51%). The function and role of IT in an organization are assisting in streamlining business processes via IT, creating a competitive edge through strategic developments, underpinning/enhancing strategic business goals, and maximizing operational efficiencies (Peppard and Ward, 1999). Therefore, Taiwan’s financial industry is an ideal place to investigate the relationships among the variables of IS outsourcing and develop a model for impacting clients’decision on IS outsourcing vendors.

The organization of the remaining paper is as follows: Research Model depicts the variables and the model, Research Method profiles the 12 CIOs and briefly describes the process of conducting this study, Measure and Results examines the summarized results, Discussion presents the interpretation of the results, and Conclusions summarizes this study with limitations and future work.

RESEARCH MODEL

The formulation of the proposed research model is presented first and then the justification of the variables from the literature is analyzed in this section.

Model formulation

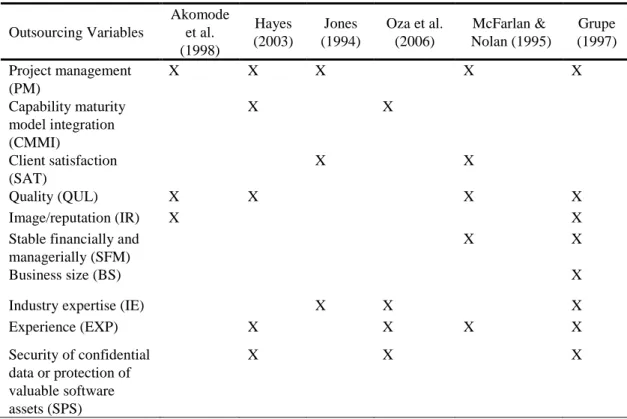

With additional companies outsourcing their software-related operations, issues associated with the management of outsourcing relationships have attracted significant research attention. Many studies have identified numerous outsourcing variables. However, no consistent groups have been found. Our literature analysis resulted in ten external variables with regard to the theoretical research model. These variables, including project management (PM), capability

maturity model integration(CMMI), client satisfaction (SAT), quality (QUL), image/reputation (IR), stable financially and managerially (SFM), business size (BS), industry expertise (IE), experience (EXP), and security of confidential data or protection valuable software asset (SPS), have been posited or demonstrated as being associated with outsourcing in previous researches. Table 1 provides a summary of prior outsourcing variables adopted in this study.

Table 1 Ten IS outsourcing variables

Outsourcing Variables Akomode et al. (1998) Hayes (2003) Jones (1994) Oza et al. (2006) McFarlan & Nolan (1995) Grupe (1997) Project management (PM) X X X X X Capability maturity model integration (CMMI) X X Client satisfaction (SAT) X X Quality (QUL) X X X X Image/reputation (IR) X X

Stable financially and managerially (SFM)

X X

Business size (BS) X

Industry expertise (IE) X X X

Experience (EXP) X X X X Security of confidential data or protection of valuable software assets (SPS) X X X

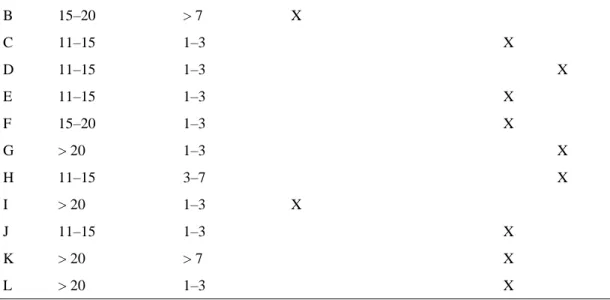

Moreover, ten variables found to affect the outsourcing decision in previous studies are categorized into four belief groups, including management belief (MB), company belief (CB), domain expert belief (DEB), and security belief (SB), based on the opinion of twelve chief information officers (CIOs). The demographic profile of the 12 CIOs with their beliefs is summarized in Table 2. The CIOs all have over 10 years experience of software industry, are currently working in the companies with capital of greater than 100 $USD million, and mostly agree or strongly agree with the 4 belief categories suggested by this study.

Table 2 Demographic profiles of the twelve CIOs associated with their responses to four beliefs categories

Response to four belief categories CIO Interviewee’s

experience in the software industry (number of years) Capital of the company (Unit: USD

$100 million) Stronglydisagree Disagree Neither Agree Stronglyagree

B 15–20 > 7 X C 11–15 1–3 X D 11–15 1–3 X E 11–15 1–3 X F 15–20 1–3 X G > 20 1–3 X H 11–15 3–7 X I > 20 1–3 X J 11–15 1–3 X K > 20 > 7 X L > 20 1–3 X

Table 3 Ten outsourcing variables vs. 4 groups of beliefs by 12 CIOs

Outsourcing Variables Management Company Domain expert Security

Project management (PM) 11 1

Capability maturity model integration

(CMMI) 7 1 4

Client satisfaction (SAT) 5 2 4 1

Quality (QUL) 5 2 5

Image/reputation (IR) 12

Stable financially and managerially

(SFM) 12

Business size (BS) 12

Industry expertise (IE) 2 10

Experience (EXP) 2 4 6

Security confidential data or protection of valuable software asset (SPS)

1 11

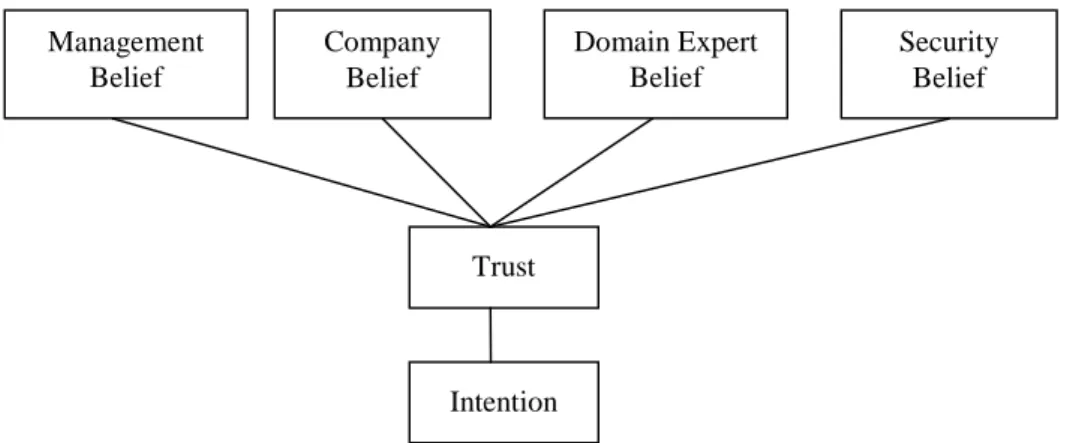

The detailed distribution of how the 12 CIOs related the 10 variables to the 4 beliefs are summarized in Table 3. A simple guideline for assigning the variable to the belief is based on the number of votes by the 12 CIOs. For example, since Project Management has 11 votes on Management belief and 1 vote on the Company belief, it is classified into Management belief. Accordingly, PM, CMMI, SAT and QUL belong to Management belief, IR, SFM, and BS belong to Company belief, IE and EXP belong to Domain Expert belief, and SPS alone belongs to Security.

Another noteworthy variable is trust. In their case study of outsourcing relationships, Zviran et al. (2001) found that the gradual development of trust can lead companies from merely being committed to a contract to becoming long-term strategic partners. There are also many

studies on the effect of trust as an important outsourcing factor (Kishore et al., 2003; Sabherwal, 1999; Lander et al., 2004; Kern and Willcocks, 2000; 2002). Thus, it is reasonable to introduce trust into the uncertain model of clients when they choose an IS outsourcing vendor.

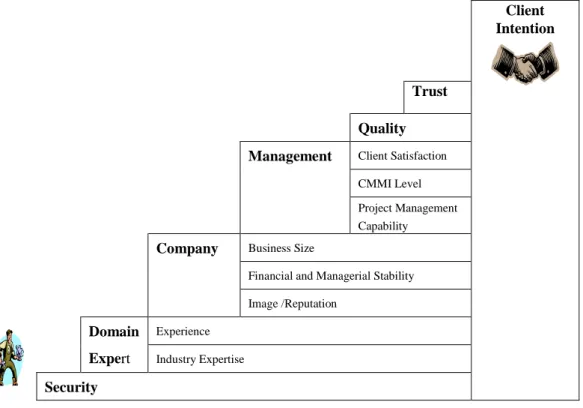

Based on the above derivation, we propose a conceptual model as shown in Figure 1. Briefly speaking, client’s beliefs of Management, Company, Domain Expert and Security impact client trust, which in turn impacts the client’sintention to adopt the software vendor.

Justification of the Variables from the Literature

As can be seen from Table 2, not all the CIOs consented to the idea of categorizing the ten variables into the belief groups. For instance, one CIO who did not agree stated, “It is not easy to find a qualified outsourcing vendor right now; too many restricted criteria only limit you to solve the problem and make you stop.”Another CIO stated, “There are more beliefs or variables that should be considered in IS outsourcing relationships. For example, the commitment to serve for long terms. Qualified vendors may successfully finish the IS project under the consideration of the four beliefs. However, it would be a disaster if the vendors fail to maintain the system.”Despite the voice of disagreement, this study still proceeded as planned and the disagreement was treated as one of the limitations of this study. All variables affecting the outsourcing relationships in our study are delineated as follows.

Management belief. When selecting an outsourcing vendor, MB is also considered. For example, according to one IT manager, “The better the outsourcing vendor management project, the better the outcome, quality, and satisfaction the project will result in.”While the CMMI variable is not yet popular in Taiwan, the trend of adopting CMMI is likely to reflect the trend of adopting the ISO standard in Taiwan’s IT industry in the near future.

Management Belief Company Belief Domain Expert Belief Security Belief Trust Intention

(1) Project management (PM): Better PM can provide better outsourcing quantitative

estimation or measurement capabilities. It is likely that vendors with better PM can achieve better performances than their competitors (Jones, 1994). Leading vendors generally employ a suite of software project management tools, including cost estimation, quality estimation, software planning, and software tracking tools. McFarlan and Nolan (1995) also argued that a firm in the factory quadrant that selects an operationally strong outsourcer may be in trouble if it suddenly moves toward the strategic quadrant and its partner lacks the necessary project management and innovation skills to operate there.

(2) Capability maturity model integration (CMMI): CMMI provides a detailed method for

assessing the maturity of the software development process. CMMI is divided into five levels. Each level represents a different stage of maturity. As the software development process matures and becomes more defined, an organization is able to progress from one level to another (Hather, Burd, and Boldyreff, 1996). Now, customers inquire about these certifications, and more firms are looking to learn or adopt some aspects of the CMMI or other quality practices (Hayes, 2003; Merchant, 2001; Gallagher, 2004; Koch, 2004). If an organization is able to fully satisfy all these criteria, it can be considered as being at a given maturity level. The high maturity status of a company provides a reasonable level of confidence that a company is following the best practices.

(3) Client satisfaction (SAT): Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1988) defined customer satisfaction as the difference between perceived quality and expected quality. Scholars of different academic backgrounds have developed different analyses of customer satisfaction by considering it both theoretically and practically (Chien, Su, and Su, 2002). IS outsourcing is about long-term satisfaction (Jones, 1994). Leem and Yoon (2004) viewed customer satisfaction as a broad concept that includes a perceived evaluation of products and services. They developed a generic survey that could be used for the measurement of customer satisfaction in all service sectors. Service quality (SERVQUAL) also was suggested as a means to measure the service quality of a given information system (Kettinger and Lee, 1997; Pitt and Waton, 1995). Kern and Willcocks (2000) argued that satisfaction in the outsourcing relationship comes aboutnaturally with theachievementoftheclient’sexpectations.

(4) Quality (QUL): The quality will affect the performance of an outsourcing project (Grupe, 1997; Akomode and Irgens, 1998; Hayes, 2003; McFarlan and Nolan, 1995). Increased quality is the realization of a senior executive’s dream of creating agile networks of global IT services (Shih and Fang, 2004). Many companies have recently been choosing IS outsourcing in response to complicated IS and various internal requirements. Yoon and Im (2005) also argued in favor of developing a system to evaluate IS outsourcing customer satisfaction and maintain a high quality of IS outsourcing vendors’services.

Company belief. Some survey participants considered CB as the primary source when initially selecting an outsourcing vendor. As one CIO stated, “We are choosing an outsourcing vendor that can help and cooperate with us and serve as a long-term partner.” Another IT manager said, “Because the outsourcing vendor has strong financial support from her mother company, we don’t have to worry about whether there will be bankruptcy or shut-down problems which may cause the outsourcing project to break down.”Other factors categorized in CB were the vendor’s business size, reliability, and cost. For example, as one CIO stated, “The bigger the outsourcing vendor, the more experienced staff it will have.” Nevertheless, an IS outsourcing vendor, who has twenty-five years’experience in the IT industry and fifteen years of IS outsourcing experience, stated, “In my IS outsourcing career, there were about thirty cases from about thirty customers. Most of them were in the financial industry, and they cared more about the performance of the IT system than other variables. Some of them cared about the size of my business, which was not as big as that of other vendors. They even duly and diligently visited my company, but we could still beat other competitors. It was because we let our customers believe that we were small but strong and capable of concentrating our efforts, and we finally proved that we could be their long-term partner.”

(1) Image/reputation (IR): The image of the outsourcing vendor will affect the result of selecting an outsourcing vendor (Gonzalez, Gasco, and Llopis, 2006; Grupe, 1997; Akomode and Irgens, 1998). Initially, reputation is a critical variable for trust. This reputation leads to good references and a stable relationship in software outsourcing (Oza et al., 2006). For upper-level managers, reputation is an important determinant of trust as they handpick individuals for inclusion in the outsourcing project (Lander et al., 2004).

(2) Stable financially and managerially (SFM): Financial stability and funding can help the outsourcing vendors to stay competitive in the outsourcing arena (Grupe, 1997; McFarlan and Nolan, 1995).

(3) Business size (BS): Some businesses are too small to provide adequate staff support. Although such businesses deploy as wide a variety of systems, software packages, and networks as their larger counterparts and encounter an equal number of related problems, they have fewer resources with which to resolve problems. Therefore, a larger business size can provide more resources to solve problems (Grupe, 1997).

Domain expert belief. DEB was another critical belief considered by some survey participants. As a CIO stated, “I liked to choose an outsourcing vendor who possessed the mandatory skills required to help us to finish an IS project. However, as time went by, some other successful cases showed me that even a vendor without domain business knowledge

could finish the case successfully through better communication and interaction between the user and the vendor. This has changed my stereotypical view of outsourcing vendors.”He went on to argue that a vendor without experience was more likely to forget the burden of old cases and create an innovative project.

(1) Industry expertise (IE): The outsourcing vendor should have expertise in the company’s industry and in the kinds of software the company uses. If the outsourcing vendor serves direct competitors, it will be imperative to ensure adequate confidentiality (Jones, 1994; Akomode and Irgens, 1998; Kishore et al., 2003). An additional difficulty pertains to the qualification of the provider’s staff, although in theory, outsourcing provides access to technical knowledge and IS specialists’expertise. Besides, it often happens that in practice, outsourcing vendors are supported by the same staff as before (Fowler and Jeffs, 1998; Glass, 1996; Gonzalez et al., 2005), as this staff has been transferred from the client side to the vendor side.

(2) Experience (EXP): The vendor’sexperience and resources will help to implement the solution (Grupe, 1997). Oza et al. (2006) found that the critical variables for achieving critical trustin an outsourcing relationship includepreviousclients’references and experience of the vendor in outsourcing engagements. The information provided by the vendors can be considered as highly reliable as these vendors have long experience in the software industry and outsourcing business as well as senior positions in the company.

Security belief. One IT manager stated, “When outsourcing an IS project, I am very afraid of our confidential data being transferred into the hands of a competitor, or the advantage created from the cases being copied.”According to another CIO, “Both outsourcing contract term and internal management should be considered when outsourcing IS services for providing information security assurance.”Further, an IS outsourcing vendor stated, “Regarding security belief, in my experience there are different opinions between an IT-background and a non-IT-background person. The non-IT-background person who is responsible for the IS outsourcing case will care more about the security belief than the one who has an IT background.”These opinions demonstrate that security is another variable. Unless companies spend time to evaluate all the risks and whether it is a good fit for their individual circumstances, outsourcing can be a lesson in lost time, money, quality, and productivity (Hayes, 2003). In many cases, the outsourcing vendor will have access to the outsourcing client’s data which may be commercially sensitive; it is important to ensure that confidentiality is respected by making express provisions to this effect. Information security aims at ensuring the integrity and privacy of data owned by the company (Lee, 1996). Grover et al. (1994) and Lacity and Hirschheim (1993) also discussed security issues.

Grupe (1997) and Blackley et al. (1996) have argued about transferring sensitive issues such as business objectives, technology plans, and business data to a third party (the service provider or an outsourcing vendor). Information security is an integral part of all outsourcing activities. When the IT function is provided in-house, it falls under the outsourcing customer’scontrol. However, the customer can no longer retain full control of information security when IS is outsourced (Lee, 1996). Rottman and Lacity (2006) also suggested segmenting outsourcing projects to protect intellectual property.

Trust. Oza et al. (2006) suggest that trust is an important component in many business relationships. This includes intercompany relationships, whether cooperative ventures or subcontracting relationships, and relationships among different divisions of a single company. Iyer and Kusnierz (1996) also argue that the success of outsourcing depends to a great extent on developing good working relationships and building trust between organizations and their external contractors. This creates new challenges for internal control and fraud prevention. Trust in software outsourcing relationships involves clients and vendors having positive expectations of each other’sactions,whilehaving arationalintention of maintaining their relationship in the awareness of the risks involved.

Intention (INT). We conducted questionnaire surveys with twelve IS outsourcing experts related to the IS outsourcing service industry, academia, and the government in order to generate customer-intention-affecting variables and to verify extracted key variables from the literature reviews. We then defined all customer-intention-affecting variables. Subsequently, we made an evaluation of intention for IS outsourcing when choosing outsourcing vendors.

RESEARCH METHOD

This section describes the research method used to test the research model and hypotheses. Based on the proposed model for IS outsourcing relationships, both data collection methods of personal interview and survey are adopted. The research model required a great deal of information to be gathered from the survey participants. As CIOs and survey participants often do not have the time for in-depth interviews, we decided to administer both questionnaires and short interviews.

In the first stage, as seen in the previous section, we conducted the short interviews with twelve CIOs and classified 10 variables into MB, CB, DEB, and SB. To assess the research model in the second stage, we conducted a questionnaire-based survey to collect data from IT managers or staff employees of Taiwan’sfinancialindustry.Participants were asked to fill out the questionnaire, based on their experiences of working with one particular IS outsourcing

vendor.

The preliminary instrument was initially reviewed for comprehensiveness and unambiguity by some faculties, doctoral candidates, and Executive Master of business administration (EMBA) students who had also worked in the financial industry. The measurement sufficiency of the proposed measures was also examined in a realistic context by some IT experts in the financial market in order to verify the suitability of the written expressions, the clarity of the information, and the response formats. It was concluded that no particular problems existed in the survey instrument.

Invitation e-mails were sent out to more than 300 people, including IT managers and employees working in Taiwan’s financial industry. The e-mail explained the purpose of the study and requested peoples’participation. The investors were asked to click on the URL link provided in the e-mail message, which was linked to the Web-based online survey instrument. A coupon valued at 100 Taiwanese dollars (about USD$3) was offered to encourage participation.

Each participant was asked to complete a questionnaire that included the measures of the ten variables, attitude, trust, and three types of intentions. All items had five-point scales anchored with “lowest consent level”(1),“highest consent level”(5),and “neutral level of consent”(3).The questionnaire items can be seen in Table 5 in the next section. Overall, 102 experts with work experience in IS outsourcing responded to our survey.

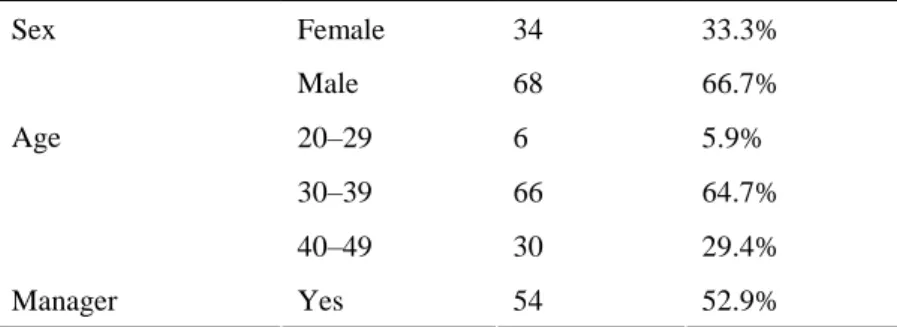

MEASURES AND RESULTS

The individual demographic profiles of the study participants, including those of the CIOs and IT managers or staff, are summarized in Table 4. Briefly speaking, one third of the participants are female, majority of them fall into 30-39 age group, one half are in the manager level, and three fourth have background in IT. This profile roughly matches the stereotype of Taiwan IT professions based on our assessment.

Table 4 Demographic profiles of the 102 study participants

Female 34 33.3% Sex Male 68 66.7% 20–29 6 5.9% 30–39 66 64.7% Age 40–49 30 29.4% Manager Yes 54 52.9%

No 48 47.1%

Yes 76 74.5%

IT background

No 26 25.5%

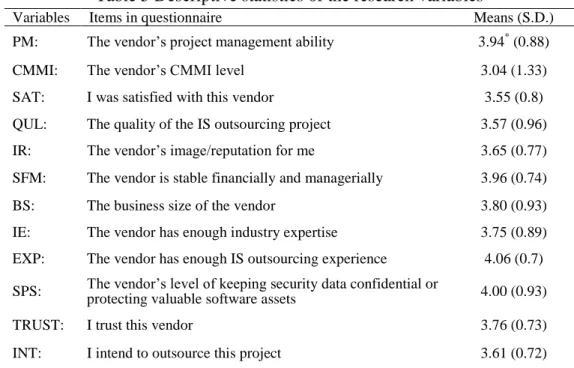

The descriptive statistics of the mean and standard deviation (S.D.) for the ten variables are summarized in the last column of Table 5. Among them, all but one have averages above 3.5, which is on the somewhat consent level of the five-point scale used in this study. In particular, EXP and SPS are above 4.0 and PM and SFM are close to 4.0, which indicate a pretty strong level of consent. On the other hand, CMMI is just a little bit over the neutral level of 3.0, which is an indication of it being a relatively less dependent variable. As mentioned in the above section, the descriptions of the questionnaire items are shown in the second column of Table 5.

Table 5 Descriptive statistics of the research variables

Variables Items in questionnaire Means (S.D.)

PM: Thevendor’sprojectmanagementability 3.94*(0.88) CMMI: Thevendor’sCMMIlevel 3.04 (1.33) SAT: I was satisfied with this vendor 3.55 (0.8) QUL: The quality of the IS outsourcing project 3.57 (0.96) IR: Thevendor’simage/reputation forme 3.65 (0.77) SFM: The vendor is stable financially and managerially 3.96 (0.74) BS: The business size of the vendor 3.80 (0.93) IE: The vendor has enough industry expertise 3.75 (0.89) EXP: The vendor has enough IS outsourcing experience 4.06 (0.7)

SPS: protecting valuable software assetsThevendor’slevelofkeeping security data confidential or 4.00 (0.93)

TRUST: I trust this vendor 3.76 (0.73)

INT: I intend to outsource this project 3.61 (0.72)

* the averages are based on the five-point scale, where 1 indicates the lowest consent level and 5 for highest consent level.

Reliability estimates (coefficient alphas) for the four groups of beliefs of the research model are shown in the last column of Table 6. Since security has only one item, its reliability is unavailable. Among the other three beliefs, only Management belief has a reliability coefficient higher than 0.8, which is considered adequate. As for the other two beliefs, namely Company belief and Domain Expert belief, their reliability coefficients are less adequate since they are 0.6454 and 0.5671. Therefore they will be marked as limitations of this study in the Conclusion section.

Belief Item α Project management (PM)

Capability maturity model integration (CMMI) Client satisfaction (SAT)

Management

Quality (QUL)

0.8097

Image/reputation (IR)

Stable financially and managerially (SFM) Company

Business size (BS)

0.6454

Domain expert Industry expertise (IE) 0.5671 Experience (EXP)

Security Security of confidential data or protection of

valuable software assets (SPS) NULL

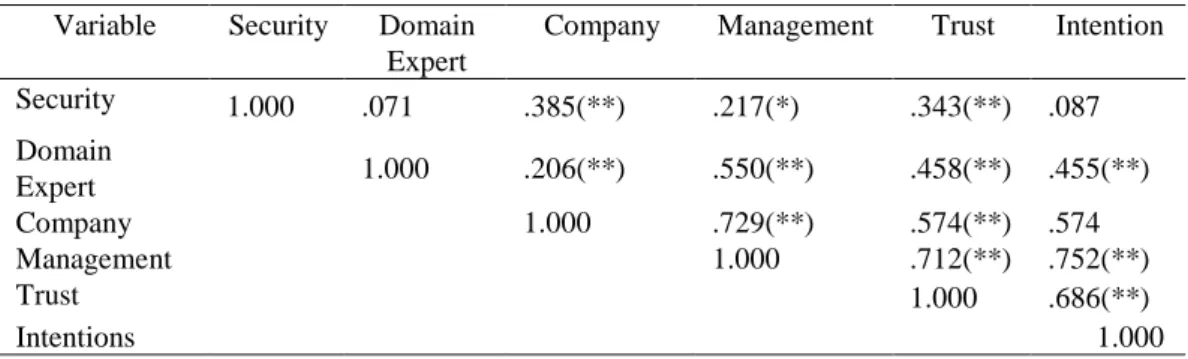

Using our research model, the ten variables were categorized into four beliefs. MB, CB, and DEB consisted of more than one variable; only one variable was categorized under SB. Therefore, we assumed that the values of MB, CB, and DEB could be equal to the average of the associated variables and be calculated by MB = (PM + CMMI + SAT + QUL ) / 4, CB = (IR + SFM + BS ) / 3, and DEB = (IE + EXP ) / 2. Table 7 summarizes the correlation coefficients among the four beliefs, trust, attitude, and the responses to the three types of intentions. For the 102 participants, all the beliefs with trust are at least significant at the 0.05 levels. In other words, the conceptual model is fully supported by the data collected in this study.

Table 7 Correlation matrixes for the four belief groups, trust, and intentions

Variable Security Domain Expert

Company Management Trust Intention

Security 1.000 .071 .385(**) .217(*) .343(**) .087 Domain Expert 1.000 .206(**) .550(**) .458(**) .455(**) Company 1.000 .729(**) .574(**) .574 Management 1.000 .712(**) .752(**) Trust 1.000 .686(**) Intentions 1.000

** and * denote that correlation is significant at the 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively. Note: The means (standard deviations) are shown on the diagonal

When comparing the values from the four beliefs, we found that they can be ranked in the following order: SB, DEB, CB, and MB, as shown in the third column of Table 8. The results imply that in the financial industry where employees are considered to be conventional and prefer rule-regulated and structured activities, SB is considered more seriously than the other three beliefs in IS outsourcing.

Belief Value Rank Factors Value Rank Security 4.00 1 Security of confidential data or

protection of valuable software assets

4.00 2

Domain Expert 3.90 2 Industry expertise 3.75 5

Experience 4.06 1

Image/reputation 3.65 6

Financial and managerial stability 3.96 3

Company 3.80 3

Business size 3.80 4

Project management capability 3.49 9

CMMI level 3.04 10

Client satisfaction 3.55 8

Management 3.41 4

Quality 3.57 7

DISCUSSION

According to the statistical analyses and CIO interview data, three implications can be derived as described next.

Implication 1: Security—the most important concern

The findings of our survey indicated security was the most important among the four beliefs, and 2nd important variable among the ten variables in Table 8. One outsourcing vendor in our survey stated that most of his customers considered security issues when choosing an IS outsourcing vendor, although it was not the most important factor when compared with the other factors. However, security of data or physical assets is one of the most frequently cited concerns in many IS outsourcing studies; in addition, poor security, whether a breach that causes customer distrust or a catastrophic event that affects data or processes (Hayes, 2003; Jones, 1994), has been known to cost companies their money and reputation.

Therefore, while considering IS outsourcing services, companies in the financial industry request vendors to provide information on security issues and base their expectations of IS management and control on this information. Herein, we suggest that an information security standard that specifies high-level security requirements should be focused on and provided by vendors when clients issue their outsourcing requirements. While outsourcing IS services in the financial industry, it is essential that security issues, including roles, responsibilities, and accountability, are clearly defined and well understood by both clients and vendors. Specific security aspects must be included in both service level agreements (SLAs) and the security requirements of contracts. In our survey, some interviewees also mentioned their opinions on confidential data. For example, one CIO stated, “We provide all the stuff related to the outsourcing project; therefore, all the tasks related to IS outsourcing including program coding or document editing should be done on-site.”

Implication 2: Trust as a bridge between beliefs and intentions

Many studies have ascertained variables that influence trust. In this regard, trust could be differentiated into two parts (Oza, 2006): achieving trust in outsourcing relationships and maintaining trust in ongoing outsourcing relationships. Trust is also considered to be an extremely delicate issue in outsourcing relationships. Our study demonstrated that the four beliefs—SB, CB, DM, and MB—can serve as trust-achieving variables. This is consistent with other recent works on outsourcing relationships (Oza, 2006; Zviran et. al, 2001). Therefore, trust can serve as an intermediary connecting belief with intentions. From a practical perspective, our study shows that the combination of the four groups of beliefs and trust is positively correlated with intentions as seen in Table 7.

Implication 3: Suggested model for acquiring client intention

Based on the analytical outcomes resting on the ten factors, four beliefs, and a bridge connecting them with client intentions, we propose a model, as shown in Figure 2, which can chart the vendor’s path and help increase the client’s intention in it. Our study categorizes client beliefs pertaining to outsourcing into four types, wherein catering to each type constitutes a step toward attracting client intentions for vendors. However, each step rests on factors that need to be adequately strong to bear the weight of the client-vendor association and allow vendors to advance.

Trust Quality Client Satisfaction CMMI Level Management Project Management Capability Business Size

Financial and Managerial Stability

Company

Image /Reputation Experience

Domain

Expert Industry Expertise

Security

Client Intention

Addressing SB is the first step for vendors toward garnering client intentions. SB comprises only one factor, and this factor is of paramount importance because clients will not outsource work to vendors who cannot guarantee protection of their security assets.

The second step for vendors is catering to DEB, which comprises two factors: industry expertise and experience. A capable expertise provides adequate support to handle all applications. By recruiting, training, retraining, and retaining qualified staff in order to offer specialized services for clients’ company-specific problems, outsourcing vendors can positively affect the trust and intentions of clients. Further, vendors should also possess expertise in client industries and software. In cases where outsourcing vendors serve the direct competitors of their clients, ensuring adequate confidentiality is imperative for the vendors. Herein, experience and resources of vendors facilitate the implementation of solutions (Grupe, 1997). Critical variables in realizing trust in an outsourcing relationship include previous clients’referencesand vendors’experiencein outsourcing engagements.Ifthesecriteriaare met, information provided by the vendors can be considered as highly reliable.

Ensuring CB constitutes the third step for vendors en route to securing client intentions. This step is laid on the foundations of the following three factors: image/reputation, financial and managerial stability, and business size. The reputations of outsourcing vendors affect their chances of receiving outsourcing assignments (Gonzalez et.al, 2005). Initially, reputation is a critical variable for trust in the field of software outsourcing in that it leads to good references and stable relationships. For top managements, reputation is an important determinant of trust when they handpick individuals for outsourcing projects (Lander et. al, 2004). Financial stability and funding can help outsourcing vendors stay competitive in the outsourcing arena (Grupe, 1997; McFarlan and Nolan, 1005). Some small businesses can fall short of providing adequate staff support even when they deploy as wide a variety of systems, software packages, and networks as their bigger counterparts and resolve equally as much related problems. This is because they possess fewer problem-solving resources. Therefore, the larger the business size, the more are the resources available for problem solving.

The fourth step of advancement for vendors is guaranteeing MB, which comprises the following four factors: project management capability, CMMI level, client satisfaction, and quality. Better project management capabilities can translate into better quantitative outsourcing estimation or measurement capabilities, thereby helping vendors achieve better performances than their competitors. Leading vendors generally employ a suite of project management tools, including cost estimation, quality estimation, software planning, and software tracking tools. For example, a firm in the factory quadrant that selects an operationally strong outsourcer may encounter difficulties if it suddenly shifts to the strategic quadrant where its partner lacks the necessary project management and innovation skills to

operate. Secondly, CMMI provides a detailed method for assessing the maturity of the software development process. Lastly, Satisfaction in an outsourcing relationship comes about naturally with the meeting of client expectations. The more satisfied a client is with a vendor, the more trust and intention the vendor is guaranteed. High quality of IS outsourcing services by vendors can maintain IS outsourcing customer satisfaction.

After vendors understand and satisfy client beliefs, akin to taking developmental steps, they are led to the bridge of trust that connects them with clients, helping them attract client intentions. Our study ascertains that trust is highly correlated with client intentions. Vendors who satisfy client beliefs and the included factors better their chances of gaining client trust and securing outsourcing assignments.

CONCLUSIONS

This study is one of the first to explore clients’reasoning process when they choose an IS outsourcing vendor and proposes a theoretical-based model to address this issue in the context of the financial industry. With the analytical approach used in this study, we believe that this study presents useful and practical findings for IS outsourcing vendors to acquire client’sintention to adopt.

Despite our careful work, a few limitations need to be noted when using the practical model and implications of this study. First of all, there are only 10 variables and 4 beliefs considered in this study. Some of the CIOs stated that more variables and beliefs may be needed to comprehend the basis on which the clients choose the software outsourcing vendors. Secondly, the reliability coefficients of the four beliefs are not comfortably adequate to analytical standards. More questionnaire items and variables may be needed to improve current measurements. Thirdly, if designed appropriately with the second limitation considered together, the research model can use a more formal method like structured equation method to fit the research model and test the model path. Finally, only the respondents in Taiwan’sfinancial markets are surveyed in this study. Although the findings may be useful to its scope, they are certainly not representative of the entire Taiwanese financial industry or participants elsewhere. Future research will be necessary to examine these relationships in other financial markets or to compare the results with other industries and demonstrate the managerial implications of these comparisons.

REFERENCES

Akomode, O.J., Lees, B., and Irgens, C. (1998), “Constructing customized models and providing information to support IT outsourcing decisions”, Logistics Information Management, Vol. 11, No 2, pp. 114–127.

Blackley, J. and Leach, J. (1996), “Security considerations in outsourcing IT services”, Information Security Technical Report, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 11–17.

Chien, T.K., Su, C.H., and Su, C.T. (2002), “Implementation of a customer satisfaction program: a case study”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 102, No. 5, pp. 252–259.

The Directorate General of Budget, The Executive Yuan, Taiwan (2007),“StatisticalAnalysis of ROC Computer Resources Survey”, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), pp. 9–24. http://eng.dgbas.gov.tw/public/Data/512917332271.doc

Fowler,A.and Jeffs,B.(1998),“Examining information systems outsourcing: a case study from the United Kingdom”, Journal of Information Technology, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 111–26. Gallagher, J. (2004), “Uncovering offshore secrets”, Insurance & Technology, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 35–38.

Glass, R.L. (1996),“The end oftheoutsourcing era”, Information Systems Management, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 89–91.

Gonzalez, R., Gasco, J., and Llopis, J. (2006) “Information systems outsourcing: a literature analysis”, Information & Management, Vol. 43, pp. 821–834.

Gonzalez, R., Gasco, J., and Llopis, J. (2005), “Information systems outsourcing risks: a study of large firms”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 105, No. 1, pp. 45–62.

Grover, V., Cheon, M., and Teng,T.C.(1994),“A descriptivestudy on theoutsourcing of information systems functions”, Information & Management, Vol, 27. No 1, pp. 33–44. Grupe, F. (1997), “Outsourcing the help desk function”, Information Systems Management, Vol. 14, No 2, pp. 15–22.

Hather, R.M., Burd, E.L., and Boldyreff, C. (1996), “A method for application management maturity assessment”, Information and Software Technology, Vol. 38, pp. 701–709.

Hayes, M. (2003), “Precious connection”, InformationWeek, Vol. 960, pp. 34–40.

Iyer, N.K. and Kusnierz, R. (1996), “You can outsource many activities but not fraud!”, Information Security Technical Report, Vol. 1. No, 3, pp. 33–37.

Javidan, M. and House, R.J. (2001), “Cultural acumen for the Global Manager: Lessons from project GLOBE”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 29. No. 4, pp. 289–305.

Jones, C. (1994), “Evaluating software outsourcing options”, Information Systems Management, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 28–33.

Kern, T. and Willcocks, L. (2000), “Exploring information technology outsourcing relationships: theory and practice”, Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 9, pp. 321–350.

Kern, T. and Willcocks, L. (2002), “Exploring relationships in information technology outsourcing: the interaction approach”, European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 3–19.

Kettinger, W. and Lee, C. C. (1997), “Pragmatic perspectives on the measurement of information systems service quality”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 19, pp. 223–240.

Kishore, R., Rao, H.R., Nam, K., Rajagopalan, S., and Chaudhury, A. (2003), “A relationship perspective on IT outsourcing”, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 46 No. 12, pp. 87–92.

Koch, C. (2004), “Bursting the CMM Hype”, CIO, Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 1–6.

Lacity,M.C.and Hirschheim,R.(1993),“Theinformation systemsoutsourcing bandwagon”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 73–86.

Lander, M., Purvis, R., McCray, G., and Leigh, W. (2004), “Trust-building mechanisms utilized in outsourced IS developmentprojects:a casestudy”,Information & Management, Vol. 41, pp. 509–528.

Lee, M. (1996), “IT outsourcing contracts: practical issues for management”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 96, No.1, pp. 15–20.

Leem, C.S. and Yoon, Y.K. (2004), “A maturity model and an evaluation system of software customer satisfaction: the case of software companies in Korea”, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 104, No. 4, pp. 347–354.

McFarlan, F. and Nolan, R. (1995), “How to Managean IT Outsourcing Alliance”, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 9–23.

Merchant, K. (2001), “IT Sector hopes it can turn problems into solutions”, Financial Times. London (UK), pp. 13–15.

Oza, N., Hall, T., Rainer, A., and Grey, S. (2006), “Trust in software outsourcing relationships: an empirical investigation of Indian software companies”, Information and Software Technology, Vol 48, pp. 345–354.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., and Berry, L.L. (1988), “SERVQUAL: a multi-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 64, pp. 12–40.

Peppard, J. and War, J. (1999), “Mind the Gap: diagnosing the relationship between the IT organization and the rest of the business”, Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 8, pp. 29–60.

Pitt, L.F., Waton, R.T., and Kavan, C.B. (1995), “Service quality: a measure of information systems effectiveness”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 19, pp. 173–187.

Rottman, J. and Lacity, M. (2006), “Proven practices for effectively offshoring IT work”, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 56–63.

Sabherwal, R. (1999), “The role of trust in outsourced IS development projects”, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 80–86.

Shih, Y. and Fang, K. (2004), “The use of a decomposed theory of planned behavior to study Internet banking”, Internet Research, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 213–223.

Taylor, S. and Todd, P. (1995), “Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models”, Information Systems Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 144–176.

Yoon, Y. and Im, K. (2005), “An evaluation system for IT outsourcing customer satisfaction using the analytic hierarchy process”, Journal of Global Information Management, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 55–77.

Yusufa, Y., Gunasekaranb, A. and Abthorpe, M.S. (2004), “Enterpriseinformation systems project implementation: A case study of ERP in Rolls-Royce”, International Journal of

Production Economics, Vol. 87, pp. 251–266.

Zhu, Z., Scheuermann, L., Babineaux Jr., B.(2004),“Information network technology in the banking industry”,Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 104, No. 5, pp. 409–417. Zviran, M., Ahituv, N., and Armoni, A. (2001), “Building outsourcing relationships across the global community: the UPS-Motorola experience”, Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 313–333.