台灣與荷蘭輕度智能障礙中學生的個別化教育研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(5) Acknowledgements. This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many people. First of all, the deepest gratitude to advisor 周祝瑛 and committee members 施淑慎 and 洪儷瑜 for their guidance, support and advice. The author is indebted to the staff members of Accent Nijkerk, Taipei Junior High School, and Nan Gang Senior Vocational High School who were all very willing participants in this. 政 治 大. research project. Special thanks as well to Roland Loos and Mr. Cees Hoedjes for assisting in. 立. the Dutch school case selection.. ‧ 國. 學. Finally, the author would like to thank 廖崑志, 朱尹安 and 周欣音 for their invaluable assistance in researching the Taiwanese section of this dissertation, 吳孟淳 for transcribing. ‧. the Taiwanese interviews, and William Trainor for the proofreading of this report.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i. i n U. v.

(6) 摘要. 近來教育的研究,特別是輕度智能障礙的研究有減少的趨勢。通常這一類的學 生會合併其他高出現率的障別,而不同的研究認為這些障別會有不同的特質。本研究 旨在著重中學階段輕度智能障礙學生尤其是個別化教育,因為學者專家共同指出這些 學生需要個別化教育。台灣、荷蘭在中學階段與輕度智能障礙有關的政策也強調符合 學生個別需求、興趣和能力,所以這兩個國家可以在個別化教育這一方面做比較。. 政 治 大 度智能障礙學生有何全國教育政策;期許和需求與關於達成 (2) 兩國的學校與老師如 立. 本論文的目的將研究與比較以下兩方面: (1) 台灣與荷蘭在中學階段之個別輕. ‧ 國. 學. 何落實個別輕度智能障礙學生的教學。為達成此目的,研究者擬蒐集兩國相關教育政 策資料,以及與學校主要成員進行深入的半結構訪談。在資料分析過程中,會著重在. ‧. 兩國的政策和個案學校特殊狀況。而後將相互比較兩國對輕度智能障礙學生之個別化. y. Nat. er. io. sit. 教育政策與學校執行情況,能對兩國的輕度智能障礙學生的個別化教育有所了解。以 增進兩國在此方面的相互學習與借鏡。. al. n. v i n Ch 本研究指出在台灣和荷蘭個別化教育的歷程皆受到不同世界潮流的影響。最明 engchi U. 顯的是現標準化本位改革在台灣已經成為一種趨勢,而學生導向的個別化教育計畫概 念在荷蘭的學校個案是受到支持的。此外,在台灣教育政策和規範的訂定是由中央到 地方,而在荷蘭教育方案的發展則由各校自行訂定。在個案學校的主要研究發現是, 荷蘭個案在個別化教育歷程中被賦予比較多正式責任,而台灣個案相形之下較少。. ii.

(7) 此外,在台灣、荷蘭組成個別化教育的項目在個別的中學低年級和高年級相當不同, 而兩國的中學個別化教育項目同時呈現相同與相異之處。該研究基於研究發現提出部 分建議,並針對未來可能的研究提出建議。. 【關鍵詞】個別化教育、輕度智能障礙、中等教育、台灣、荷蘭. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(8) ABSTRACT. Research into education for, specifically, the mildly mentally impaired has in recent years decreased. Often this population of students is combined with other high incidence disabilities while significant differences in characteristics have been recognized. This research project, therefore, specifically focuses on the population of mildly mentally impaired students in secondary education and particularly individualized education, since there is a consensus among academics that this population of students has a need for a system that. 政 治 大 impaired in secondary education in both Taiwan and the Netherlands also stipulate a program 立 allows for individualized education. Policies regarding education for mildly mentally. ‧ 國. comparability between these two countries is assured.. 學. tailored to a student’s individual needs, interests and abilities and, thus, a level of. ‧. The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate and compare (1) the national policies. sit. y. Nat. for meeting the individual educational wishes and needs of mildly mentally impaired. io. er. secondary education students in Taiwan and the Netherlands and (2) how these policies are. al. v i n Ch researcher collected relevant policy documents e n gandc performed h i U in-depth, semi-structured n. implemented in high-quality school cases in both countries. To achieve this purpose, the. interviews with key staff members at the school cases. During the process of data analysis, due attention was given to the fact that both the countries’ policies, as well as the school cases, are embedded in their own unique contexts. Upon analyzing the gathered data, a comparison of both countries’ individualized education systems for mildly mentally impaired secondary education students was performed, highlighting similarities and differences. The findings of this research project indicate that the process of individualizing education has been shaped by national cultures as well as different worldwide trends in both Taiwan and the Netherlands. Most notably, there has been a drive for standards-based reform. iv.

(9) in Taiwan while in the Netherlands the concept of the student-led IEP has found an advocate in the school case researched. Furthermore, relevant educational policies and regulations are created and enforced in a top-down manner in Taiwan while the Netherlands shows elements of a bottom-up approach. Among the major findings from the school cases is that the Dutch case shows a student who is endowed with a greater degree of formal responsibility in the process of individualizing education than the Taiwanese counterparts at both the lower and upper level school cases. Furthermore, in both countries, individualized education at the lower and upper secondary education stages consists of different elements. The degree to. 治 政 大 on the findings, and differences. This report concludes with recommendations based 立. which these elements are present in Taiwan and the Netherlands shows similarities and. suggestions for possible future research are offered.. ‧ 國. 學. individualized education, mild mental impairment, secondary education,. ‧. io. sit. y. Nat. Taiwan, the Netherlands. n. al. er. Keywords:. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

(10) Table of Contents 摘要. ii. Abstract. iv. Chapter 1. Introduction. 1. 1.1 Research Background and Motivation. 1. 1.2 Research Purpose. 5. 1.3 Research Questions. 5. 政 治 大 1.5 Research Extent and Limitations 立 1.4 Definitions of Terms. Literature Review. 7. ‧ 國. 學. Chapter 2. 6. 2.1 Educational Needs of Mildly Mentally Impaired Students. 9 9. 2.3 Secondary Education Curriculum for Mildly Mentally Impaired Students. y. 18. sit. ‧. 14. 20. Nat. 2.2 Secondary Education Programs for Mildly Mentally Impaired Students. n. al. er. io. 2.4 Individualizing Education for Mildly Mentally Impaired Students 2.5 The Taiwanese Context 2.5.1 Country Profile. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 27 27. 2.5.2 The Education System of Taiwan. 30. 2.5.3 Mildly Mentally Impaired Students in Taiwanese Secondary Education. 34. 2.6 The Dutch Context. 47. 2.6.1 Country Profile. 47. 2.6.2 The Education System of the Netherlands. 50. 2.6.3 Mildly Mentally Impaired Students in Dutch Secondary Education. 53. vi.

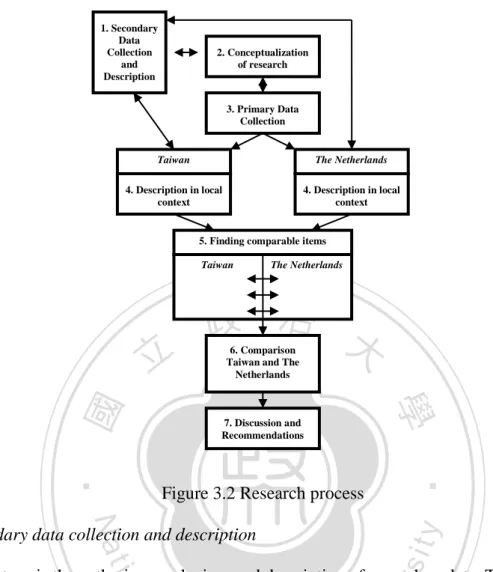

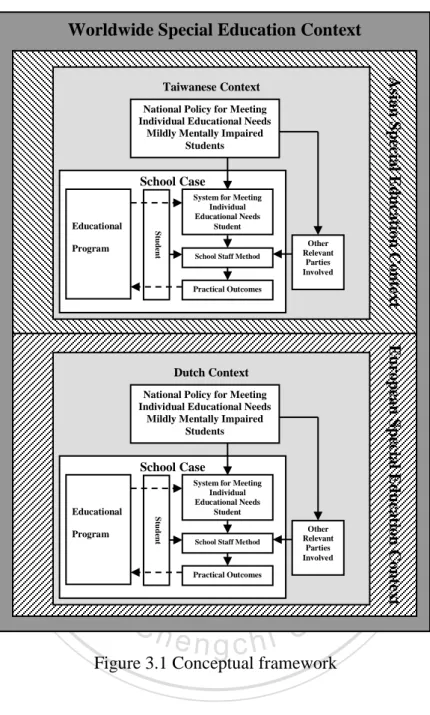

(11) Chapter 3. Research Methodology. 72. 3.1 Research Method. 72. 3.2 Conceptual Framework. 74. 3.3 Research Subject. 75. 3.4 Research Instruments. 78. 3.5 Research Process. 79. 3.6 Data Collection. 81. 3.7 Data Analysis. 83. Chapter 4. 政 治 大. Research Findings. 4.1 Taiwan. 立. 86. 4.1.2. Implementation in Taiwanese School Cases. ‧ 國. Taiwanese Policy. 86. 學. 4.1.1. 86. ‧. Taipei Junior High School. 90 90. sit. y. Nat. School background. 89. io. er. Research participants The school’s programs. n. al. Ch. Individualizing education. engchi U. Nang Gang Senior Vocational High School. v ni. 90 92 98 110. School background. 110. Research participants. 111. The school’s program. 112. Individualizing education. 117. vii.

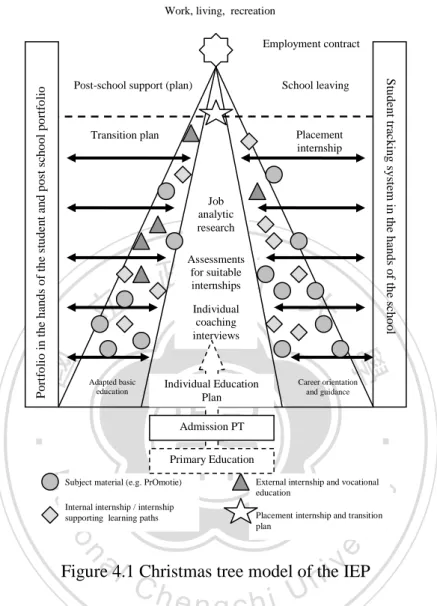

(12) 4.2 The Netherlands. 131. 4.2.1. Dutch Policy. 131. 4.2.2. Dutch School Case Implementation. 135. Accent Nijkerk. 135. School background. 136. Research participants. 136. The school’s program. 138. Individualizing education. 146. 治 政 大 5.1 The Definition of Mildly Mentally Impaired Students 立. Chapter 5. Comparison. 166 166. 5.3 Participants in the Process of Individualizing Education. 169. 學. ‧ 國. 5.2 National Context. ‧. 5.4 System and Tools for Individualizing Education. sit. io. al. er. 5.6 Individual Student Evaluation. n. 5.7 Individualized Education Chapter 6. 174 180. y. Nat. 5.5 Method of Individualizing Education. 173. Ch. engchi U. Conclusions and Recommendations. v ni. 193 195 198. 6.1 Conclusions. 198. 6.2 Recommendations. 201. Appendices. 203. References. 254. viii.

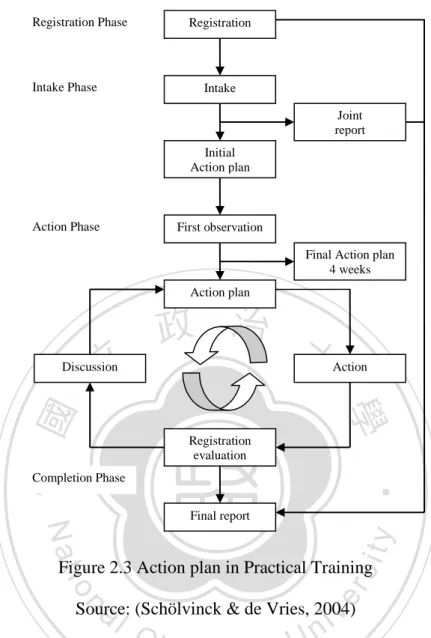

(13) Table of Figures 17. Figure 2.2. Comprehensive Vocational Department vocational exploration. 44. Figure 2.3. Action plan in Practical Training. 65. Figure 3.1. Conceptual framework. 75. Figure 3.2. Research process. 80. Figure 4.1. Christmas tree model of the IEP. 135. Figure 4.2. AKA course. 144. Figure 4.3. Triangle meetings. 政 治 大 Comparison of definition of mildly mentally impaired students 立. 150. Table 5.2. Comparison of national contexts. 171. Table 5.3. Comparison of participants in the student’s individualized. Table 5.1. ‧. ‧ 國. Resource room programs. 學. Figure 2.1. education process. 168. 174. Overview of the IEP contents. Table 5.5. Comparison of system and tools for individualizing education. Table 5.6. Comparison of the method of individualizing education. Table 5.7. Comparison of individual student evaluation. Table 5.8. Individualized education at the lower secondary education level. 196. Table 5.9. Individualized education at the upper secondary education level. 197. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Table 5.4. Ch. engchi U. v ni. 176 179 191 194. List of Appendices Appendix A. Education system of Taiwan. 203. Appendix B. Education system of the Netherlands. 204. Appendix C. Interview protocol Taiwan (Chinese version). 205. Appendix D. Interview protocol Taiwan (English version). 209. ix.

(14) Appendix E. Interview protocol the Netherlands (Dutch version). 214. Appendix F. Interview protocol the Netherlands (English version). 218. Appendix G. (Partial) IEP example Taipei Junior High School. 222. Appendix H. IEP presentation Accent Nijkerk. 230. Appendix I. List of competencies PrOmotie curriculum. 240. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(15) Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1. Research Background and Motivation This research project aims to investigate and compare the national policies for. meeting the individual educational wishes and needs of mildly mentally impaired secondary education students in Taiwan and the Netherlands and how these policies are implemented in high-quality school cases in both countries. While the diagnosis of mild mental impairment is one of the most frequently applied diagnoses of disability (one of the high incidence disabilities), “little current research is. 政 治 大. conducted on this population at the secondary level when considering curriculum and. 立. instructional environments” (Bouck, 2004, p. 368). This is in contrast to the past when “the. ‧ 國. 學. field of mild mental retardation was described as being “center stage” in special. ‧. education…[and] literature was replete with research and programmatic contributions that assessed educational programs for individuals with this disability as well as providing models. y. Nat. er. io. sit. for curriculum and instruction” (Polloway, 2006, p. 186). Researchers, therefore, believe that the field of research into mild mental impairment is becoming endangered (Bouck, 2005;. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. Fujiura, 2003; Polloway, 2004). Bouck (2007) performed a review of Education and Training. engchi. in Developmental Disabilities, which showed that between 1998 and 2005 only 13 studies explicitly referenced students with mild mental impairment. During that same timeframe, two appeared in Exceptional Children and six in Journal of Special Education. Often research on secondary education for students with mild mental impairment was combined with other categories. Most often, these other categories were learning disabilities and emotional impairments, as both are, together with mild mental impairment, high-incidence disabilities. However, research has indicated that there are cognitive differences between children with learning disabilities and mild mental impairment (Scott & Perou, 1993). Furthermore, based. 1.

(16) on a review of eight studies examining the way students with learning disabilities and mild mental impairment learn with respect to the three instructional contexts of inductive reasoning tasks, guided inquiry, and relatively long-term academic interventions, Caffrey and Fuchs (2007) found that there were relevant differences between learning disabilities and mild mental impairment. Similarly, there are also qualitative differences between individuals with mild impairment and ones with higher levels of impairment. While individuals with moderate and severe mental impairment are expected to require assisted care throughout their lives, the. 治 政 大this means that while students independently and hold steady jobs. In an educational setting 立 majority of individuals with mild impairment are expected to live independently or semi-. with moderate to severe mental impairment may focus on studying employment,. ‧ 國. 學. transportation, recreation, cooking, and social skills, “many children with milder forms of. ‧. intellectual disabilities can learn basic academic skills as well” (Kauffman & Hung, 2009, p.. sit. y. Nat. 452). If these different outcomes are considered, it can be argued that there should be. io. er. significant differences in educational programming (Bouck, 2004). Therefore, in research, “aggregating data for students with [mild mental impairment] with data for either [learning. al. n. v i n disabilities] or moderate and severeC mental makes effective, targeted, and h e impairment ngchi U. informed decision making difficult” (Bouck, 2004, p. 368). If these data (those students diagnosed with mild mental impairment and other high incidence disabilities) are not segregated, the quality of research is affected and questions about the validity of findings can be raised. This researcher intends to make such segregation of data a foundational point of this research project. The current debate about provision of education to mildly mentally impaired students could be broadly defined as a question of where to teach them (inclusive education or special schools) and what to teach them (access to the general curriculum or a functional curriculum. 2.

(17) addressing the daily needs of this particular group of students). However, there is a consensus that this population of students, as well as other special needs students, has a need for a system that allows for individualized education. This entails tailoring education to a student‟s individual interests, strengths, weaknesses, or other educational needs. In recent years, research covering this issue, specifically applied to mildly mentally impaired students, has especially stressed the need for increased student involvement in the process of individualizing education. At one level it is obvious that Taiwan and the Netherlands are two different countries,. 治 政 大 for the mildly mentally importantly, educational systems. Secondary education provision 立. contrasting in, among other things, cultural orientation, levels of economic development, and,. impaired therefore has different features in Taiwan and the Netherlands. While both countries. ‧ 國. 學. try to achieve inclusion of this student population into mainstream education, the educational. ‧. setting is very different.. sit. y. Nat. In Taiwan, mildly mentally impaired students at the lower secondary education level. io. er. mostly attend regular education classes while receiving additional special education services. al. in a resource program. At the upper secondary education level, students attend a vocational. n. v i n Cbuth situated inside a U program specially designed for them e n g c h i regular education school.. In the Netherlands, the mildly mentally impaired students in secondary education (lower and upper level) follow a program specifically designed for this population while also joining their regular education counterparts for vocational classes. The Netherlands has an educational system tracked according to academic ability, and the mildly mentally impaired follow the lowest of the four tracks. Although this track has special education features, it is still considered to be part of mainstream education. Since the mildly mentally impaired also join classes in the track directly above them, inclusion with students without special needs is achieved.. 3.

(18) Educators of mildly mentally impaired students in both countries are required to ensure that the individual needs of these students are met when educating them. It is therefore interesting to see what the meaning of this common feature is in the context of both countries and how the process of individualizing education is achieved in these different educational settings. Although the concept of „best practices‟ is not a concept that travels across international borders easily, the findings are still put into the context of worldwide trends which are relevant to this research project. The reason for this is that both countries‟ policies. 治 政 大 and this particular context circumstances which shape their particular educational programs 立. have been shaped by some of these current trends. Nevertheless, both countries have unique. should also be taken into account. Therefore, the findings of this research project will seek to. ‧ 國. 學. explore the current state of individualized education of mildly mentally impaired students. sit. y. Nat. countries.. ‧. within the historical, socio-economic, cultural, political, and demographic contexts of both. io. er. The value of comparative studies in the field of education is that they help people. al. understand their own educational system as well as that of another country (Fairbrother,. n. v i n 2005). This value is reflected in theC fact Council of Comparative Education hthat e nthegWorld chi U Societies (WCCES), which was formed in 1970, now has 35 member societies spread across the world on six continents (WCCES, 2010). Especially in the era of globalisation, comparative education “should be reinvigorated as a vehicle to assist academics and practitioners to understand the changes around them” (Bray, 2003, p. 219). A comparative research project such as this can also encourage practitioners to appreciate their nations‟ education systems as well as to heighten their awareness of shortcomings (Bray, 2003). The researcher is in the favourable position of having lived in both Taiwan and the Netherlands for extensive periods of time. While Dutch is his mother tongue, he has also. 4.

(19) become sufficiently proficient with the Chinese language that the interviews needed for this research project, as well as the researching of documents (albeit with local support), were performed by the researcher himself in the native language of the countries researched. Considering these circumstances, it can therefore be argued that a comparative research project into the educational provision of these two countries has been a unique opportunity which does not present itself frequently.. 1.2. Research Purpose. 政 治 大 mildly mentally impaired students 立 in the secondary education systems of Taiwan and the. 1. To research and compare national policies for meeting the individual educational needs of. ‧ 國. 學. Netherlands. 2. To investigate and compare the practical implementation of these national policies for. ‧. meeting the individualized educational needs of mildly mentally impaired students in. Nat. al Research Questions n. 1.3. er. io. sit. y. high-quality programs in specific Taiwanese and Dutch school cases. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 1. What are the national policies for meeting individual educational wishes and needs of mildly mentally impaired students in secondary education of Taiwan and the Netherlands? 2. What system, containing which tools, is present for individualizing education of mildly mentally impaired students in the Taiwanese and Dutch secondary school cases? 3. Who performs relevant tasks for individualizing education for mildly mentally impaired students in the Taiwanese and Dutch school cases? 4. When and how often these relevant tasks performed in the Taiwanese and Dutch school cases? 5. Where are relevant tasks performed in the Taiwanese and Dutch school cases? 5.

(20) 6. What are the methods, used by school staff members involved, for individualizing education for mildly mentally impaired students in the Taiwanese and Dutch school cases? 7. What is the rationale, of the Taiwanese and Dutch school cases‟ staff members involved, behind these methods for individualizing education for mildly mentally impaired students? 8. What are the practical outcomes of the methods used for individualizing education for mildly mentally impaired students in the Taiwanese and Dutch school cases? 9. What are the similarities and differences in Taiwanese and Dutch policies regarding individualizing education for mildly mentally impaired secondary education students, and. 政 治 大. what are similarities and differences in the implementation of these policies in the two countries‟ specific school cases?. 學. 1.4. ‧ 國. 立. Definitions of Terms. ‧. Individualized Education. Nat. sit. y. This represents the formal and informal process of adapting secondary education to. n. al. er. io. the individual interests, strengths, weaknesses, or other educational needs of the individual. i n U. v. student. This process can be directed by, but is not limited to, such tools as the Individualized. Ch. engchi. Education Program (IEP) as well as the Individual Transition Plan (ITP), or certain other student support tools.. Mild mental impairment According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) (2002), mental impairment is a “disability characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and in adaptive behaviour, which covers many everyday social and practical skills. This disability originates before the age of 18.”. 6.

(21) The AAIDD (2002) assesses a mildly mentally impaired individual‟s intellectual functioning as being between two to three standard deviations from the mean, or equivalently within the IQ range of 50-55 to approximately 70 points, while also showing concurrent deficits in adaptive behaviour. Mental impairment is also referred to as, among others, mental retardation, mental disability, mental deficiency, cognitive impairment, and, in the United Kingdom, as learning disability (British Institute of Learning Disabilities, 2009), although this should not be confused with the other, more commonly used, conception of learning disabilities (National. 治 政 大 for mildly mentally impaired While both Taiwan and the Netherlands use definitions, 立. Center for Learning Disabilities, 2009).. students in education, based on the one provided by the AAIDD, it is important to note here. ‧ 國. 學. that both countries use slightly different definitions. These definitions will be covered in. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Secondary Education. ‧. detail in the following chapters.. al. n. The term secondary education refers to the stage between the primary (or elementary). i n C phase of education and higher education education). h (or e ntertiary gchi U 1.5. v. Research Extent and Limitations As is common with qualitative case studies, purposive sampling has been used for this. research project. Therefore, the findings from this research project cannot be generalized to other schools in either country. These school cases are not typical examples but instead represent high-quality implementations of national policies. The process of individualizing education for mildly mentally impaired students in secondary education involves a wide range of people. This research project intends to. 7.

(22) investigate national policies and their subsequent implementations by relevant school staff members. This does not mean that the researcher considers the input of other parties in this process, including the students themselves, to be less significant. On the contrary, these parties‟ contributions could be pivotal to the process of individualizing education, and are deserving of attention. Nevertheless, as research projects are inevitably narrowed down to avoid data overload, interviewing these individuals is beyond the scope of this report.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 8. i n U. v.

(23) Chapter 2 Literature Review This chapter will give an overview of the worldwide context of the “who” (mildly mentally impaired students), “where” (secondary educational program setting), the “what” (secondary education curriculum), and the “how” / “when” (individualizing education). This will be followed by a description of the Taiwanese and Dutch general context, the educational context, and the context of the mildly mentally impaired student population in both these countries‟ secondary education setting.. 2.1. 治 政 Mentally Educational Needs of Mildly Impaired Students 大. 立. While in international researches, the term „retardation‟ “remains the most commonly. ‧ 國. 學. used referent at this time” (Polloway, 2006, p. 184), the term „impairment‟ is also widely. ‧. used. The researcher has opted to use the term „impairment‟ as he believes it to have less negative associations than „retardation‟.. y. Nat. io. sit. Mental impairment “generally refers to delayed intellectual growth and is manifested. n. al. er. in inappropriate or immature reactions to one‟s environment and below average performance. Ch. i n U. v. in the academic, psychological, physical, linguistic, and social domains” (Patton, Payne, &. engchi. Beirne-Smith, 1990, p. 33). Individuals with mild mental impairment “demonstrate adaptive behaviour and intellectual functioning at the upper end of the [mental impairment] continuum” (Patton et al., 1990, p. 198). The American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities has been the leading organization in defining mental impairment (Greenspan, 1999). This organization formerly assessed (currently this assessment is still most often used worldwide) a mildly mentally impaired individual‟s intellectual functioning as being between two to three standard deviations lower than the mean, or equivalently within the IQ range of 50-55 to. 9.

(24) approximately 70 points (AAIDD, 2002). Currently, a definition based on the level of support needed is used by the AAIDD, ranging from intermittent to pervasive. A person with mild mental impairment is now referred to as a person needing intermittent support. Scholars concluded that this new classification model was largely ignored after its introduction (Polloway, Smith, Chamberlain, Denning, & Smith, 1999). Therefore, in Taiwan and the Netherlands, when measuring levels of mental impairment, authorities still refer to the previous AAIDD classification of impairment which ranges from mild to profound (Dosen, 2005; 陳麗如,2005). A more elaborate description the diagnosis of mentally impaired. 政 治 大 Apart from intellectual functioning, standardized tests can also determine concurrent 立. individuals in Taiwan and the Netherlands can be found in sections 2.5.3. and 2.6.3.. ‧ 國. 學. deficits in a mentally impaired individual‟s adaptive behaviour, which is comprised of three skill types (AAIDD, 2002):. ‧. 1. Conceptual skills: language and literacy, money, time, and number concepts; and self. sit. y. Nat. direction. io. al. er. 2. Social skills: interpersonal skills, social responsibility, self-esteem, gullibility, naïveté. v. n. (i.e., wariness), social problem solving, and the ability to follow rules / obey laws and to avoid being victimized. Ch. engchi. i n U. 3. Practical skills: activities of daily living (personal care), occupational skills, healthcare, travel / transportation, schedules / routines, safety, use of money, use of the telephone In summary, the characteristics of the mild variant of mental impairment can be broken down into the following fields relevant to this condition (Patton et al., 1990): 1. Communication skills: ability to listen and speak effectively, can carry on an involved conversation, may have some difficulty understanding some concepts and vocabulary, restricted expressive vocabulary. 10.

(25) 2. Physical dimensions: no major problems 3. Social adjustment: interactions with others are reasonably acceptable, some social skill deficiencies 4. Independent functioning: self-supporting 5. Occupational / vocational level: good potential for competitive employment 6. Academic performance: can achieve academic competence and literacy When it comes to education, Bouck (2007) emphasizes that “[s]tudents with mild mental impairment do not have mild needs”(p. 81). As to the specific educational. 治 政 大 mentally impaired] students [m]any scholars…have noted the difficulties of [mildly 立. characteristics of this population,. whose school performance is characterised by slow learning rates, reliance on. ‧ 國. 學. concrete learning experiences, short term memory weaknesses, demands for frequent. ‧. and specific feedback, and poor generalisation and transfer of learning across contexts. sit. y. Nat. or disciplines (Andrew & Williamson, 1994, p. 3).. io. er. Education of the mentally impaired includes a selection of functional behaviours to be acquired. Functional skills are those skills which are “useful to students that [give] them. al. n. v i n C hof obtaining positive control over their environment in terms e n g c h i U and consistent results” (Patton et al., 1990, p. 317). A skill is functional in nature when: - the skill will be useful and adaptive for that individual, - the learner is able to use the skill in the immediate environment with positive environmental consequences for the learner in daily interactions, - the learner is able to use the skill often, - the skill is a prerequisite for learning more complex skills, - the student becomes more independent as a result of learning the skill,. 11.

(26) - the skill allows the student to qualify for improved or additional services, or services in a less restrictive setting, or - modifies a behaviour because it is harmful or dangerous to self or others (Patton et al., 1990). When considering the educational needs of mildly mentally impaired students, many researchers especially emphasize the two areas of social relationships and self-determination. Based on a historical review of the condition of mild mental impairment, Patton, Polloway and Smith (2000) confirm “that [mild mental impairment] has been, and continues to be, a condition concerned with social competence” (p. 80). While there are multiple. 治 政 conceptualizations of social competence, a common way of大 viewing it is as a judgement of 立. specific social behaviours (social skills) (Gresham & MacMillan, 1997). Upon finishing their. ‧ 國. 學. education, young adults with mild mental impairment often experience employment. ‧. difficulties as well as other adult roles due to a lack of appropriate social behaviour (Black &. sit. y. Nat. Rojewski, 1998). These employment difficulties can ultimately lead to these employees. io. er. losing their job. Research indicates that workers without mental impairment often lose jobs. al. for character reasons while workers with mental impairment more often lose their jobs for. n. v i n C h (Black & Rojewski, reasons involving lack of social awareness e n g c h i U 1998). While adequate social skills will increase the chance of individuals with disabilities to hold a job, these skills also predict important social outcomes in school settings. These outcomes might include peer acceptance, significant others‟ positive judgements of social competence, academic achievement, adequate self-concept, positive attitudes toward school, and freedom from loneliness (Gresham & MacMillan, 1997). Drawing on the evidence from a number of researches, Elksnin and Elksnin (2001) point out that there is “strong evidence that occupationally specific social skills [for individuals with disabilities] may be even more important than academic or vocational skills” (p. 92) and therefore these occupational social. 12.

(27) skills should be included in specific educational programs. Occupational social skills are those social skills related to getting and keeping a job (Elksnin & Elksnin, 2001). Researches related to education for the mentally impaired also often cover the issue of self- determination. Self-determination has been described by Wehmeyer (1996), as “acting as the primary causal agent in one‟s life and making choices and decisions regarding one‟s quality of life free from undue external influence or interference” (p. 24). Self-determined behaviour is shown by actions which have four characteristics (Wehmeyer, 1998a): 1. The person acted autonomously. 2. The person‟s actions were self-regulated. 3.. 治 政 大 The person initiated and responded to the events in a “psychologically empowered” 立 manner.. ‧ 國. 學. 4. The person acted in a self-realizing manner.. ‧. In literature, many advocates can be found for the promotion of self-determination in the. io. al. er. the reasons of the importance attributed to self-determination as:. sit. y. Nat. lives of the mildly mentally impaired as well as other disabilities. Zhang (2001) summarized. n. 1. Self-determination is needed by individuals with disabilities to make successful transitions into adulthood.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2. The ability to exercise choice and self-determination plays a central role in helping individuals with mental impairment improve their quality of life. 3. Individuals with disabilities demand to take charge of their own lives and enjoy selfdetermination. 4. Self-determination facilitates community integration.. 13.

(28) 2.2. Secondary Education Programs for Mildly Mentally Impaired Students Secondary education is the stage between the primary phase of education and higher. education (Wellington, 2006). For some students it is their final stage of education (followed by entrance to the job market or work training) but for others it is a preparation for extended education. This can be reflected in, roughly, a „segmentation‟ of secondary education into a vocational path and an academic path. Special classes for students with mental impairment in Europe and the United States. 政 治 大. can be traced back to the nineteenth century. However, only since the beginning of the. 立. twentieth century have the specific needs of individuals with mild limitations been. ‧ 國. 學. recognized (Patton et al., 2000). At first, self contained special schools and classes were established as a method of transferring this particular population out of the regular grades.. ‧. This was in accordance with the predominant paradigm which emphasized segregation in line. y. Nat. io. sit. with a service-based view. The assumption was that pull-out services, often to special classes,. n. al. er. were best practice in education provision for mildly mentally impaired students (Patton et al., 2000).. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In the 1960s and 1970s, the emphasis shifted from teaching students with disabilities in special schools and classes (exclusive education) to teaching these students within the mainstream education system (inclusive education). In line with this new trend of thought, Dunn (1968), in his seminal article Special education for the mildly impaired – Is much of it justified?, called for a stop to the segregation of the mildly mentally impaired from the regular school population. He argued that educators should “stop labeling these deprived children as mentally impaired [and]…stop segregating them by placing them into…allegedly special programs” (p. 6). According to him, labelling would reduce the teacher‟s expectancy for individuals with disabilities to succeed and removing handicapped children from the 14.

(29) regular grades would furthermore significantly contribute to these individuals‟ feelings of inferiority and problems of acceptance. These „slow learning children‟ should therefore be kept in “the mainstream of education with special educators serving as diagnostic, clinical, remedial, resource room, itinerant and / or team teachers, consultants, and developers of instructional materials and prescriptions for effective teaching” (p. 11). The current debate concerning education for the mildly mentally impaired is still centred around the question whether or not this population of students should be taught in separate, special, classes only (exclusive education), or if they should be included in the. 治 政 大inclusion (Kirk, Gallagher, & mainstreaming, can be divided into full inclusion and partial 立 regular classroom (inclusive education). Such inclusive education, also referred to as. Anastasiow, 2000). Full inclusion refers to the student constantly being present in the regular. ‧ 國. 學. classroom with possible additional support coming from professionals in this classroom. ‧. (“push in” support). Partial inclusion, entails a student physically leaving the regular. y. sit. io. er. out” support).. Nat. classroom for part of the day to attend special classes, for instance in the resource room (“pull. al. The inclusion movement has found an advocate in the United Nations which stated in. n. v i n CFramework its seminal Salamanca Statement and h e n g cforhAction i U on Special Needs Education that “[e]xperience in many countries demonstrates that the integration of children and youth with special educational needs is best achieved within inclusive schools that serve all children within a community” (UNESCO, 1994). Inclusive education is in line with the United States‟ regular education initiative (REI), which states that students with disabilities should be served exclusively in regular education classrooms and should not be “pulled out” to attend special classes (Sacks, 2001). One of the main rationales behind this initiative is that inclusive education promotes social interaction between regular students and students with disabilities. The concept of least restrictive. 15.

(30) environment is closely related to this. It involves attempting to educate a special needs child in the environmental setting that maximizes the chances that the child will respond well to the educational goals and objectives set for him or her (Kirk et al., 2000). The REI initiative and its concurrent least restrictive environment policy have also been implemented in various other countries worldwide. Some researchers, however, point out that regular education settings, instead of being less restrictive, can actually be more restrictive as it is not clear which setting most effectively services special needs students (Patton et al., 1990). Therefore, there is a lack of consensus as to what the educational programming should be for secondary. 治 政 full inclusion of students with disabilities. Concerning the 大 negative aspects of full inclusion, 立. students with mild mental impairment. Bouck (2007) summarized research findings related to. she highlights that some of the research found that students perform worse academically, but. ‧ 國. 學. also that students experience social isolation in inclusive settings: “…although physical. ‧. inclusion may occur, very little integration or social inclusion may actually result for students. sit. y. Nat. with mild mental impairment” (Bouck, 2007, p. 83). Concerning positive aspects of inclusion,. io. er. she points out that some researchers found that students with disabilities make more progress. al. in inclusive classrooms than pullout classes while not widening the gap between special. n. v i n C h students. Furthermore, education students and general education e n g c h i U the classroom environment in inclusive settings was rated in reasonably similar ways by students with disabilities and students without disabilities. Bouck concludes that “there is a philosophical push toward including [mildly mentally impaired] students in general education classes without definitive research that suggests this is the most advantageous for this population” (Bouck, 2007, p. 83). Kauffman and Hung (2009) second this thought by stating that “no reliable research has been done on the matter of where students with intellectual disabilities are best taught” (p. 454). On the other hand, critics of categorical service delivery and instruction (e.g. specifically aimed at the mildly mentally impaired or learning disabled) believe that “categorical labels. 16.

(31) lead to overgeneralizations about and stereotypification of students with disabilities, a myopic preoccupation with within-child characteristics, and concomitant disregard for studentenvironment interaction” (Caffrey & Fuchs, 2007, p. 119). Inclusive education entails making use of special education support services defined in a special education resource program. For pullout services a resource room is commonly designated as a place where students receive pedagogical support. In this resource room, special needs students remain in a regular education class but also receive special education through the coordinated efforts of the regular education teacher and the resource room. 治 政 needs students. Figure 2.1 provides an overview of these: 大 立. teacher (Patton et al., 1990). There is a large variation of resource room programs for special. ‧ 國. 學. Teach child within small group on weekly basis in resource room. Ch. engchi U. er. n. al. Resource room teacher. sit. y. ‧. io Teach child on daily basis in resource room individually or in small group. Provide materials and consultation. Continuous assessment of teacher and child needs. Nat. Teach child individually in resource room on a weekly basis. Provide special materials. v ni. Teach child in regular class Teach regular class, regular teacher teaches child. Teach child in resource room for short periods of time and return to regular class full time. Refer for outside help Recommend special class placement. Figure 2.1 Resource room programs Source: (Patton et al., 1990). 17.

(32) If the least restrictive environment principle is maintained, the resource room is preferred to the part-time special class, and the teacher consultant is preferred to the resource room (Kirk et al., 2000).. 2.3. Secondary Education Curriculum for Mildly Mentally Impaired Students The word „curriculum‟ is very much a contested concept. It can be very narrowly. defined as a course of study to be followed while a much broader definition contests that the. 政 治 大. curriculum is all the formal and informal opportunities for learning provided by the school. 立. (Rose, 2007). The term „curriculum‟, in this section, will be referred to as the relatively. ‧ 國. 學. narrow meaning of the particular subject areas and topics that schools and teachers include in their instruction (Brown & Percy, 2007).. ‧. While researchers do not always agree on the extent of the curriculum, two. y. Nat. sit. international developments have greatly influenced curriculum considerations for students. n. al. er. io. with special needs: inclusion and standard-based reform. Many countries “have enacted. Ch. i n U. v. educational reforms that attempt to raise standards and to provide a common set of. engchi. educational experiences for all children” (Rose, 2007, p. 295).. While the educational program setting for mildly mentally impaired students can as of yet not be agreed upon, some believe the specific type of curriculum to be of an even greater importance (Bouck, 2007). Or, in other words, the „where‟ can not be placed over the „what‟ (Kauffman & Hung, 2009). “Historically, curricular and instructional practices in programs for individuals with mild mental retardation varied from theory to practice. In theory, the commitment was clearly to a functional orientation in curriculum and preparation for adulthood” (Patton et al., 2000, p. 83). In practice however, “…courses of study…tended to be watered down regular curriculum” (Dunn, 1968, p. 15). The curriculum for students with 18.

(33) disabilities was based on the general education curriculum but modified to fit the expected performance level of these students. The idea was to remediate students‟ difficulties and help them achieve in the general curriculum, although at a slower pace (Clark, 1994). In contrast, a functional curriculum is a curriculum designed to teach the skills necessary to live (functional life skills) in an inclusive community (Bouck, 2009). Such a functional curriculum consists of core academic subjects, vocational education, community access, daily living, financial matters, independent living, transportation, social relationships, and self-determination. It is aimed at preparing students to function as independently as. 治 政 大 curriculum feel that the mainstreaming students with disabilities, proponents of a functional 立 possible in an integrated society (Valletutti, Bender, & Sims-Tucker, 1996). When. regular programs should be modified in functional, real-life ways (Valletutti et al., 1996).. ‧ 國. 學. According to a research covering curricula in American inclusive settings, practice shows. ‧. that , “…students with high-incidence disabilities [e.g. mild mental impairment] typically. sit. y. Nat. receive a remedial curriculum, whereas students with low incidence [more severe] disabilities. io. er. tend to receive a functional or life skills curriculum” (Bouck, 2004, p. 369). This is based on. al. the common assumption that only students with severe disabilities need a functional. n. v i n curriculum since students with mildC toh moderate disabilities e n g c h i U are assumed to be able to benefit sufficiently from the general education curriculum, albeit with remedial support (Clark, 1994). In line with this view, Wehmeyer (2006) believes that access to the general curriculum for mildly mentally impaired students should coincide with a focus on student performance standards. These standards, however, should not be narrowly defined performance indicators, as is more common in regular education, but the students should rather be allowed to express themselves in a variety of ways and content information should be provided in multiple and flexible formats. Bouck (2007), nevertheless, believes that “this movement toward increasing academic standards in the general education curriculum stands in contrast to both recent and. 19.

(34) distant research that indicated vocational education and work experiences are associated with better postschool outcomes, including employment” (p. 82). She believes that there is a lack of evidence that suggests the advantages of including mildly mentally impaired students in the general curriculum. While the above shows an apparent lack of consensus among researchers, Andrew and Williamson (1994) argue that there is a need for flexible, multi-faceted curricular pathways where “the key curricular research task is how to provide all [mildly mentally impaired] students with commonly agreed outcomes while addressing each of their particular, context-specific, ecological learning needs” (p. 4).. Individualizing Education for Mildly Mentally Impaired. ‧ 國. 學. 2.4. 立. 政 治 大. Students. ‧. In many countries, the growth of individualism in society has influenced a similar. y. Nat. io. sit. emphasis within the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities (Brown & Percy,. n. al. er. 2007). It has become more accepted that people with disabilities have unique needs, wishes,. Ch. i n U. v. life goals, and capabilities that need to be respected when providing support. This has led to a. engchi. general shift to individualize planning and instruction.. Individualized education entails a special needs student undergoing individual comprehensive evaluation prior to, and during, placement in a specific educational setting (Strickland & Turnbull, 1990). Within this setting, the support services are determined to assure appropriate education for the individual special needs student. Important is to note that individualized education should be determined by individualized needs, not availability (T. E. C. Smith, Polloway, Patton, & Dowdy, 2004). In contrast to general education, special education can include individualization along eight dimensions of instruction. The special education teacher can (Kauffman & Hung, 2009): 20.

(35) 1. vary the pacing or rate of instruction so that it is more appropriate for the individual, 2. increase the intensity of instruction by presenting more trials for a given learning task, 3. be more relentless in working with a student to ensure the acquisition of a concept or skill, 4. provide a more highly or tightly structured environment, 5. provide more explicit and immediate reinforcement for targeted behaviour or the acquisition of particular skills, 6. provide a lower pupil - teacher ratio allowing greater individualization, 7. provide a curriculum appropriate to the student‟s level of functioning and needed skills,. 治 政 大 use more frequent and precise monitoring and assessment. 立 or. 8.. Prior to individualizing planning and instruction, a comprehensive educational. ‧ 國. 學. assessment should give an overall picture of the student‟s functioning level, pinpoint the. ‧. specific strengths and weaknesses in the student‟s behavioural repertoire, and clarify the. sit. y. Nat. logical next steps in the student‟s development (Patton et al., 1990).. io. al. er. The emphasis on an individualized approach to educate special needs students can be. n. clearly seen in the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Special needs education incorporates the proven principles of sound pedagogy from which all children may benefit. It assumes that human differences are normal and that learning must accordingly be adapted to the needs of the child rather than the child fitted to preordained assumptions regarding the pace and nature of the learning process (UNESCO, 1994, p. 7). Two of the most common tools for tailoring education to special needs students‟ wishes and needs are the Individualized Education Program (IEP) and the Individual transition plan (ITP). These particular tools are used in many countries although the names. 21.

(36) are not necessarily the ones mentioned above. Furthermore, it can also be the case that these two tools are not so clearly separated in certain countries. However, they generally have features which are similar to the tools mentioned below.. Individualized Education Program (IEP) A well-known tool for individualizing education is the Individualized Education Program (IEP). Although the specifications of this particular program differ per country, the IEP generally contains the following major elements (Patton et al., 1990):. 治 政 大 in order of importance using - Prioritized annual goals. Goals may be selected and arranged 立 - Statement of present levels of functioning. The assessment process determines these levels.. the criteria for selecting functional behaviours.. ‧ 國. 學. - Short-term instructional objectives. These objectives should be behavioural objectives that. ‧. provide a clear direction for instruction and ongoing evaluation of student progress.. sit. y. Nat. - Special education and related services. Services in addition to those of a classroom teacher. io. er. which are needed in order to have a program that meets all of the child‟s educational needs. - A statement describing the extent of the child‟s participation in regular educational. al. n. v i n C hvaries according toUthe child‟s special needs and programs. The extent of participation engchi. limitations, and also to a country‟s level of inclusion practices for special needs students. - Time line of the initiation and duration of services. - Objective criteria and evaluation procedures. The formation of an IEP is done by a team of which the members can have a wide range of backgrounds. They can include teachers, psychologists, school administrators, parents, student advocates, nurses, social workers, various therapists, and the student affected (Patton et al., 1990). The exact formation of the team normally depends on the individual student‟s specific needs.. 22.

(37) IEPs are also called Individual Education Plans in certain countries, e.g. the Netherlands, Canada, and the United Kingdom.. Individual transition plan (ITP) Special needs student transition is the process of moving from one educational stage to the next and eventually to (independent) living in society and (competitive) employment. Most often it is understood as the transition from school to the post-school environment, although some countries (including Taiwan) support a student‟s transition from one. 治 政 大 on Career Development and to the post-school environment, the United States based Division 立 educational stage to the next. When considering student transition as a process of moving on. Transition (DCDT), defines it as follows:. ‧ 國. 學. Transition refers to a change in status from behaving primarily as a student to. ‧. assuming emergent adult roles in the community. These roles include employment,. sit. y. Nat. participation in post-secondary education, maintaining a home, becoming. io. er. appropriately involved in the community, and experiencing satisfactory personal and. al. social relationships. The process of enhancing transition involves the participation and. n. v i n C h adult agency services, coordination of school programs, e n g c h i U and natural supports within the community (Halpern, 1994, p. 117). It should be noted that the transition planning usually occurs in conjunction with the IEP planning process (Sands, Bassett, Lehman, & Spencer, 1998). The most common tool for. transition planning is the Individual transition plan (ITP). This tool, again for its more narrow use of preparing for the post-school environment, can contain such planning components as (Wehman, 2002): - input and participation by the student and his or her family of choice in postsecondary education, employment, community living, etc.;. 23.

(38) - participation of parents and guardians who are well informed; - annual goals along with steps to reach those goals; a list of skills required to function on the job and in the community; - specific information on who is responsible for each aspect of the process, including referrals to appropriate agencies, job placements, on-the-job-training, and job follow-up; - a longitudinal format (that begins a number of years before graduation); - coordination with the IEP during the school years and with the individual rehabilitation plan or service plan;. 治 政 大to understand and take - a user-friendly format that is easy for parents and students 立 - encouragement of the coordinated efforts of all appropriate agencies;. ownership of.. ‧ 國. 學. Methods of individualizing education have been influenced by person-centred. ‧. planning approaches for organizing assistance for people with disabilities. Person-centred. sit. y. Nat. planning was developed in the United States in the late 1970s and it is represented by a. io. er. family of approaches and techniques, which share certain characteristics (Mansell & Beadle-. al. Brown, 2004). Central to person-centred planning is that it is individualized and that it places. n. v i n C h In doing so, person-centred the person with a disability at the centre. planning (Mansell & engchi U Beadle-Brown, 2004):. 1. aims to consider aspirations and capacities expressed by the service user rather than needs and deficiencies; 2. attempts to include and mobilize the individual‟s family and wider social network, as well as the resources from the system of statutory services; and 3. emphasizes providing the support required to achieve goals, rather than limiting goals to what services typically can manage.. 24.

(39) When using the person-centred planning approach in planning transition, the Unites States based National Center on Secondary Education and Transition (NCSET) argues that “[i]t is critical for the young adult with a disability to actively participate in the transition planning meetings” (NCSET, 2004, p. 5). Instead of being a passive observer, the young person needs to be a leader in this process. This also means that this leader is also endowed with certain responsibilities, such as identifying what he / she wants for the future, what kind of support is needed to achieve goals, and coming prepared to share this information with their planning team. Furthermore, “[p]erson-centered planning is a way to identify a student‟s. 治 政 大 p. 2). students as they strive to achieve their dreams” (NCSET, 2004, 立. individual goals and to help students, families, and professionals craft plans that will support. Apart from a the person with special needs being at the centre of a transition planning. ‧ 國. 學. meeting, literature similarly emphasizes special needs students to take control in their IEP. ‧. meetings as “[i]nvolvement in education planning, decision making, and instruction can take. sit. y. Nat. many forms, from students generating their own IEP goals and objectives to students tracking. io. er. their progress on self-selected goals or objectives” (Wehmeyer, 1998a, p. 5). This researcher believes that such involvement is beneficial to the student as “[r]esearch indicates that. al. n. v i n Cchoose students who have the opportunity to activities, show enhanced motivation” h e nschool gchi U (Wehmeyer, 1998a, p. 9). Therefore, “[t]he IEP meeting is the fulcrum for education. programming and provides a unique opportunity to give students more control over their education programs” (Wehmeyer, 1998a, p. 8). This concept is known as a „student-led IEP‟ or „self-directed IEP‟. Student-led IEPs have advocates in a great number of scholars (Martin et al., 2006; Mason, McGahee-Kovac, & Johnson, 2004; Powers et al., 1998; Sands et al., 1998; Wehmeyer, 1998a). These researchers argue that if IEP meetings are not student-led, “students attending their meetings do not know what to do, do not understand the purpose of. 25.

(40) what is being said, and feel as if none of the adult participants listen to them when they do talk” (Martin et al., 2006, p. 300). Wehmeyer (1998a) identified certain barriers to involvement in education planning by students with disabilities. Among these were: -. Student competence to make decisions. Certain educators believe that adolescents with disabilities are incapable of participating in the decision-making process.. -. Student motivation. Among a number of educators, there is a perceived lack of motivation on behalf of the disabled students to participate in meetings and education programs.. -. 政 治 大. Complexity of education process. Educational planning is considered to be too complex for students by certain educators.. 立. Although these barriers exist, researches claim that they have proved that these. ‧ 國. 學. barriers are caused by misconceptions (Wehmeyer & Lawrence, 1995). Apart from having. ‧. actual competence to make decisions, past researches also show a wide range of benefits for. sit. y. Nat. students if they are enabled to make decisions. Among these are: increased motivation, higher. io. er. self-determination, higher levels of conceptual learning, increased retention, higher levels of. al. self-efficacy, and fewer behaviour problems (Doll & Sands, 1998). Furthermore, if a lack of. n. v i n Cithis often due to the U motivation is observed by educators, e n g c h i fact that the student has no control over the process of education planning (Wehmeyer, 1998a). As for the education process being too complex for students with disabilities, Wehmeyer (1998a) believes that the incorrect assumption is that students need to independently perform all educational activities. Students do not need to plan on their own but are supported in this process. Therefore, “[t]he IEP and ITP meetings provide an opportunity for the student to see him- or herself as having control over his or her life and for significant others to see the student as capable and competent” (Wehmeyer, 1998b, p. 154). If students want to become key agents in their own. 26.

(41) adult lives, “emphasis must be shifted from transition planning for youth to transition planning with youth” [emphasis in the original] (Powers et al., 1998, p. 188). The above also stresses the importance of the student‟s family involvement in the planning process. Most importantly, families should encourage and support the student in taking charge of the situation. “Our experiences in working with teenagers suggest that when educators and families are provided with information, strategies, and validation of their support capabilities, educators and families become increasingly interested and proficient in assisting youth to become active in transition planning” (Powers et al., 1998, p. 192).. 治 政 goals, even if they seem unrealistic (2004). They stress that大 “failure is not necessarily 立. The NCSET also emphasizes the need for students to explore and create their own. something to be avoided; it is a natural part of life” and “a person who is protected from. ‧ 國. 學. failure is also protected from potential success” (NCSET, 2004, p. 7). Enabling students to. y. sit er. io. The Taiwanese Context a. n. 2.5. Nat. pathways to success.. ‧. explore can be a memorable educational experience and can lead to discovering other. 2.5.1 Country Profile. iv l C n hengchi U. Taiwan is located in East Asia on two straits, the Taiwan strait off the south-eastern coast of China, and the Luzon strait connecting the South China Sea with the Pacific Ocean. Taiwan has a total area of 35,980 square kilometres (Library of Congress, 2005). The eastern two-thirds of Taiwan is mainly mountainous with a number of mountains topping 3,000 meters. The western part is made up of rolling hills that slowly descend into plains eventually reaching the coast. Taiwan also lays claim to a number of small populated islands. While Taiwan is currently officially known as the Republic of China, internationally it was formerly known as Formosa. This name was given to them by the Portuguese („formosa‟. 27.

(42) meaning „beautiful‟ in Portuguese) upon their arrival to the island in 1624. Before the arrival of the Chinese and the Europeans, the island was already home to Austronesian people whose first settlements can be dated back to 15,000 years ago (Y. S. Chen & Jacob, 2002). Spain was the first European nation to establish settlements in Formosa in 1628 but they were soon driven out by the Dutch in 1632. The Dutch themselves were driven out in 1662 by the Chinese trader Zheng Chenggong who controlled the island for twenty years while staying loyal to the emperor of the former Ming Dynasty (1368-1643). However, in 1683 the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) took control of the island which eventually led to the island gaining status as mainland China‟s Taiwan province in 1885.. 治 政 Taiwan was ceded to the Japanese after the Chinese大 were defeated in the First Sino立. Japanese War (1894-1895). The island made for a good strategic outpost with a source of raw. ‧ 國. 學. materials and Japan intended to make Taiwan a model colony for their expanding empire.. ‧. The Japanese introduced compulsory primary education to Taiwan even before it was. sit. y. Nat. introduced in Japan itself. While the period of Japanese rule brought Taiwan into the modern. io. er. age, scholars also see this period as the creation of a separate identity from mainland China. al. (Library of Congress, 2005). When the Japanese were defeated in 1945, the Republic of. n. v i n C h國民黨) arrived in U China under the Kuomingtang (KMT, e n g c h i Taiwan and brought Chinese. political, economic, and cultural influence which led to friction and clashes with the local population. After the KMT was defeated by the Chinese Communist Party in 1949, they fled the mainland and re-established their base in Taiwan. This led to economic and military support from the United States government and combined with heavy investments from the United States and Japan in the island‟s industry, the island prospered. During the economic boom of the 1960s Taiwan was the fastest growing economy in the world and was named as one of the four Asian Tigers (together with South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore).. 28.

(43) While economically they were doing very well, politically Taiwan was less successful. In 1971 China took over their seat in the United Nations Security Council which led to international isolation. Domestically, Taiwanese had been living under martial law from 1948 to 1987 but as international pressure increased, national elections were held for the first time in 1996. The reigning KMT won but lost in the following elections of 2000, and again in 2004, to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP, 民進黨) who were promoting distancing the island from mainland Chinese influence. The KMT regained control of the government in the elections of 2008. Taiwan at the moment still has a political climate which is very much. 政 治 大 The current population of Taiwan stands at a little over 23 million with a population 立. polarized between the two main parties (DPP and KMT).. ‧ 國. 學. growth rate of 0.23% (Government Information Office, 2010). The population is split into four general groups: Fukinese (people who immigrated to Taiwan from the Fukine province. ‧. in China before 1949), Hakka (people who immigrated from Guangdong province in China. sit. y. Nat. before 1949), Mainlander (people who immigrated from China after 1949), and Indigenous. io. er. Taiwanese. These four groups can be divided into two larger groups. The majority being: the. al. v i n Ch U other group represents the non-Han Austronesians, population, which e n g cthe h iindigenous n. Han Chinese, consisting of the Fukinese (74%), Mainlanders (14%), and Hakka (10%). The. accounts for the final two percent of the population (Y. S. Chen & Jacob, 2002). Taiwan has heavily populated urban areas which was home to just under seventy percent of the population in 2004 (Government Information Office, 2004).These Taiwanese urban areas are considerably more developed than the rural areas. Furthermore, rural Taiwanese are generally assumed to have more conservative values than do urban residents (Yi, Kung, Chen, & Chu, 2008).. 29.

(44) About half of the Taiwanese population is a member of a religious association. Among these, 42.9% are Buddhist, 35.6% Taoist, 6.6% I-Kuan Tao, 4.7% Protestant, 4.1% Islam, and 2.3% Roman Catholic (Library of Congress, 2005). Taiwan, in 2009, had a nominal GDP of US$ 16,442 per capita which translated into a GDP at PPP of US$31,834 per capita (Government Information Office, 2010). That same year, the GDP had a negative growth of 1.9% and the GDP per capita at PPP ranked 43rd in the world (Central Intelligence Agency, 2010). Inflation for 2010 was estimated at 1.3% and the unemployment rate estimate for 2010 was 5.2% (Central Intelligence Agency, 2010).. 2.5.2. 政 治 大 The Education System of Taiwan 立. ‧ 國. 學. Like other East Asian societies, Taiwan‟s education has been influenced by Confucian values (Chou & Ho, 2007). Confucius considered learning to be human‟s most important. ‧. defining characteristic (Yao, 2003). A result of the Confucian tradition is that Chinese society. sit. y. Nat. in Taiwan places an emphasis on credentialism and examination systems where the. io. er. examinations are expected to be fair and allow for social upward mobility (Chou & Ho, 2007).. al. v. n. Parents place high value on academic performance and the school curriculum, therefore,. i n C h etheir focuses heavily on preparing students for n gexaminations. chi U. The educational process in Taiwan is viewed as a two-fold activity (D. C. Smith, 1991). It is the transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next along with the concept of development of new ideas through understanding the old. Therefore, education involves acquiring knowledge and understanding of that which has already been accepted. This is reflected in the use of symbols in Chinese written language which can only be learned through memorization. In secondary education, memorization, drilling, and examinations are common teaching methods. Schools are also the place where values, morals, and ethical priorities will be learned. In summary, “[t]he essence of Confucianism is to provide all people. 30.

(45) with an education that includes both basic knowledge and moral precepts” (Kang, Lovett, & Haring, 2002, p. 13). After Japan‟s defeat in World War II, Taiwan quickly replaced its Japanese educators by their own intellectuals who had received their educational training in the United States. Eventually, the American style “six-three-three-four” system was adopted (Chou & Ho, 2007). This system encompasses six years of primary education, three years each for both lower and upper secondary education, followed by four years of undergraduate tertiary education. After this, graduate school programs can take one to four years and doctoral. 治 政 大 In 1968, nine-year compulsory education was established encompassing six years of primary 立 degree programs anywhere between two and seven years, depending on the department.. education and three years of junior secondary education (Ministry of Education, 2007).. ‧ 國. 學. Currently, there are plans to include senior secondary education as part of compulsory. ‧. education, making it a 12-year program.. sit. y. Nat. Upper secondary education can be divided into normal senior, senior vocational,. io. er. comprehensive, single discipline, experimental, and combined high schools (Chou & Ho,. al. 2007). The two most common among these are the normal and vocational institutions.. n. v i n C h high-quality professionals Normal senior high schools aim to nurture with a global outlook engchi U while senior vocational high schools strive to develop technical manpower for economic development (Ministry of Education, 2007). Senior vocational high schools are similar to normal senior high schools but place a heavier emphasis on practical and vocational skills. They offer courses in areas such as agriculture, industry, business, maritime studies, marine products, medicine, nursing, home economics, drama and arts (Ministry of Education, 2007). Junior high school graduates can also opt to follow a five-year junior college program while senior high school graduates can also decide to enter a junior college, although they only need to follow a two-year course. Most junior high school graduates currently take the Basic. 31.

(46) Competency Test before being admitted to a specific senior high school (Chou & Ho, 2007). Students can also be admitted to a school based on recommendations or after registering and being assigned. The effect of this system is that a major streaming exercise takes place between lower and upper secondary education, dividing students into different academic tracks based on their test results (Chou & Ho, 2007). The transition of upper secondary education to tertiary education is much the same as the one from lower onto upper secondary education, leading to students to strive “to score highly on the MPPCS [Multiroute Promotion Program for College-bound Seniors] at the end of their third year in order to attend universities” (Chou & Ho, 2007, p. 360).. 治 政 Class sizes at the junior secondary level average at 大 33 students, senior secondary 立. education has an average of 40 students, and senior vocational secondary education 42 (教育. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 部,2010a).. Relevant to current compulsory education is the recent „nine-year integrated. sit. y. Nat. curriculum‟ reform. This, controversial, curriculum reform was implemented in 2001. One of. al. er. io. the principles identified by the government for this curriculum reform being: “[t]o encourage. v. n. the development of individuality and the exploration of one‟s potentials” (教育部,2003),. Ch. engchi. i n U. which shows a focus on the individual student. This recent reform entailed integrating the six grades of primary education and the three grades of junior secondary education into a nineyear continuous curriculum. To achieve this, the following goals and objectives were developed (教育部,2003): - Integration of seven study fields: language arts, health and physical education, social studies, arts and humanities, mathematics, technology and science, and integrative activities (of all of these, language arts take about 20 – 30% of the total number of classes) - Cultivation of ten core competences: ability to understand self and develop individual potential; ability to appreciate, perform and create; ability to plan career and learn in all life;. 32.

數據

Outline

相關文件

Define instead the imaginary.. potential, magnetic field, lattice…) Dirac-BdG Hamiltonian:. with small, and matrix

Without such insight into the real nature, no matter how long you cul- tivate serenity (another way of saying samatha -- my note) you can only suppress manifest afflictions; you

becoming more widespread and schools are developing policies that allow students and teachers to connect and use their own portable equipment in school … in 75% of

5.1.1 This chapter presents the views of businesses collected from the business survey, 12 including on the number of staff currently recruited or relocated or planned to recruit

To explore different e-learning resources and strategies that can be used to successfully develop the language skills of students with special educational needs in the

educational needs (SEN) of students that teachers in the mainstream English classroom need to address and the role of e-learning in helping to address these needs;.. O To

educational needs (SEN) of students that teachers in the mainstream English classroom need to address and the role of e-learning in helping to address these needs;.. O To

Explore different e-learning resources and strategies that can be used to successfully develop the language skills of students with special educational needs in the..