語言與手勢的觀點表現 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Representations of Viewpoints in Language and Gesture. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. By Pei-yu Hsieh. er. io. sit. y. Nat. n. a l A Thesis Submitted to the i v n C hInstitute of Linguistics U Graduate engchi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. June, 2013. ii.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2013 Pei-yu Hsieh All Rights Reserved. iii. i n U. v.

(5) Acknowledgements 誌謝. 碩士生活在這炙熱的夏季,即將畫下句點。 我能順利完成這份研究和碩士論文,最要感謝的當然是我的指導教授徐嘉慧 老師。老師嚴謹做學問的態度,還有對於學術的熱誠,讓我在語言與手勢上的研 究領域獲益良多。在寫論文的期間,老師總是不厭其煩的給予指導,耐心協助我 修改論文。和老師每週的 meeting 討論,也讓我在論文方面有任何疑問時,能夠 得到老師的指引或解答。跟老師在國科會計畫的助理工作也讓我除了在學術方面 能更精進手勢研究的分析,也學習到許多行政方面的事務。對於老師,我有滿滿 的感謝及感恩。 還要感謝曾經教導過我的老師們。蕭宇超老師獨特且充滿巧思的教學設計以 及正面樂觀的人生態度讓我欽佩,上 OT 課程時的歡樂情景至今依舊歷歷在目。 何萬順老師幽默的上課方式讓我在輕鬆沒有壓力的課堂中學習句法的知識。在黃 瓊之老師的研究方法課程,我學習到了撰寫論文的基本架構。萬依萍老師的心理 語言學,也讓我在有趣的實驗當中發現許多語言學的奧妙之處。莫建清老師的構 詞學,讓我可以將語言學的知識應用在英語教學上。也感謝兩位口試委員詹惠珍. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. y. Nat. 老師和張妙霞老師,給予我寶貴的建議進行論文的修改。另外,也謝謝所上的曾 惠鈴助教,在許多行政上和學務上提供協助。. sit. n. al. er. io. 我還要感謝陪伴我在研究所生活的學長姐和朋友們。感謝書豪和心綸學長在 論文語音和句法分析上的指導和協助。感謝婉君和宇彤,能和你們一起進行手勢 上的研究和討論,並彼此加油打氣讓我在論文寫作之路不覺得孤單。謝謝姿穎, 以獨具一格的繪圖風格,幫我畫了手勢動作的連續圖解,讓我的論文可以圖文並 茂。也謝謝研究所同班的每一位同學,和你們一起上課、參加所上的活動、以及 出遊等都會是我碩士生活最美好和珍貴的回憶。在此也感謝以前就認識的好朋友 們,你們的加油鼓勵都是我動力的來源。 最後感謝一直以支持我完成碩士學位的家人。謝謝爸爸媽媽不管是在經濟的 實際層面,還是心理的精神層面,都給予我最大的支援和鼓勵,並以自己人生淬 煉出來的智慧開導我。謝謝姊姊和姊夫也總在我失落挫敗時,願意傾聽我的心聲, 給我信心和安慰。還有可愛的小咪寶,你天真活潑的笑容,常提醒我這世界有多 麼美好。 在碩士生活畫下句點的同時,也是另一個開始。希望我能擁著滿滿感謝的心, 在人生的路上看見更多美麗的風景。. Ch. engchi. iv. i n U. v.

(6) Table of Contents. Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... v Chinese Abstract .........................................................................................................viii English Abstract ............................................................................................................ ix CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................ 7 2.1 Previous studies ............................................................................................... 7. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.1.1 Labovian narrative framework and evaluation (1967, 1972, 1997).... 13 2.1.2 Goffman and the notion of footing (1981, 1986) ................................ 17 2.1.3 Bakhtin and double-voiced (1981)...................................................... 19 2.1.4 Koven and the analysis of speaker role inhabitance (2002) ............... 25. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 2.1.5 Goodwin and interactive footing (2006) ............................................. 27 2.1.6 McNeill and the gestural manifestations of viewpoints (1992) .......... 36 2.1.7 Interim summary ................................................................................. 37 2.2 Theoretical background ................................................................................. 37 2.2.1 The Free Imagery Hypothesis ............................................................. 38 2.2.2 The Lexical Semantics Hypothesis ..................................................... 43 2.2.3 The Interface Hypothesis .................................................................... 44 2.2.4 Interim summary ................................................................................. 49 2.3 Summary ........................................................................................................ 51 CHAPTER 3 DATA AND METHODOLOGY............................................................ 53 3.1 Data ................................................................................................................ 53 3.2 Third-person past events and the selection criteria ........................................ 54 3.3 Framework of the study ................................................................................. 57 3.4 Linguistic representations of viewpoints ....................................................... 61 3.4.1 Linguistic representations of speaker viewpoint................................. 62 3.4.1.1 Interrogative sentences............................................................. 63. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 3.4.1.2 Speculative expressions ........................................................... 64 3.4.1.3 Suggestive expressions ............................................................ 65 3.4.1.4 Parenthetical remarks ............................................................... 66 v.

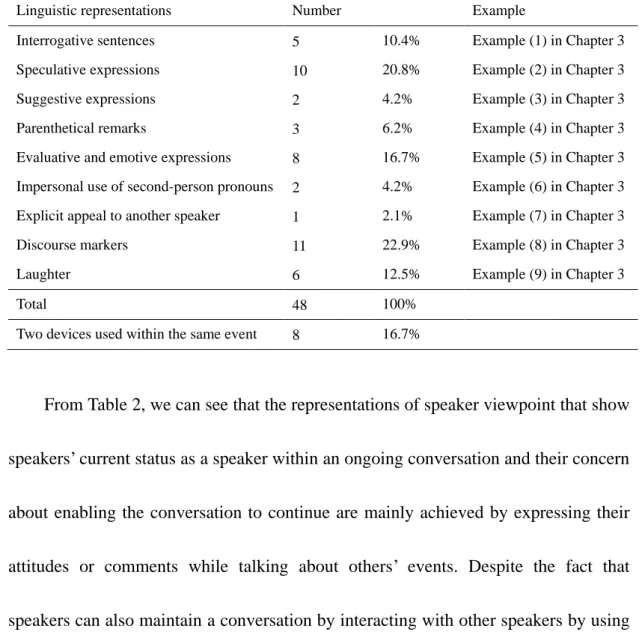

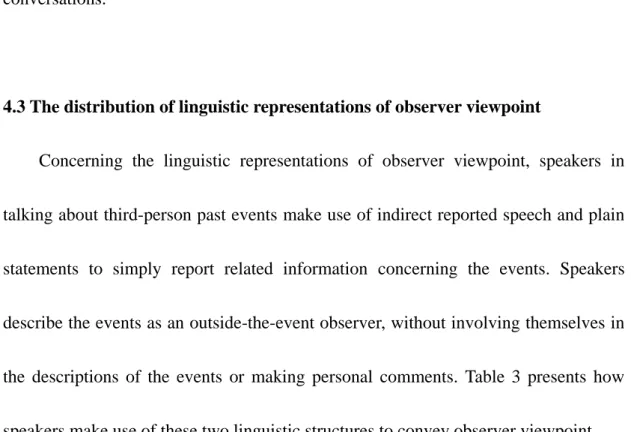

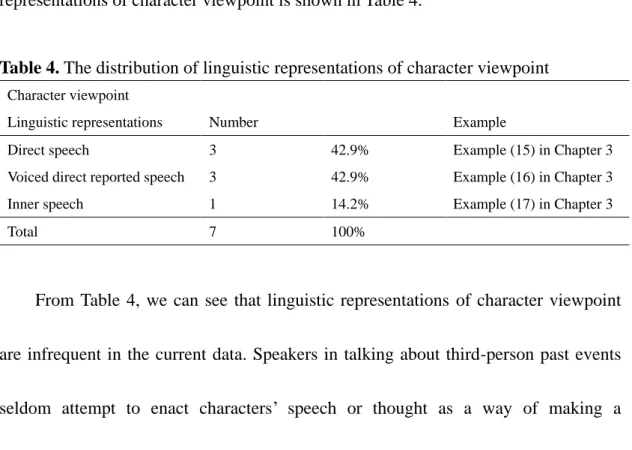

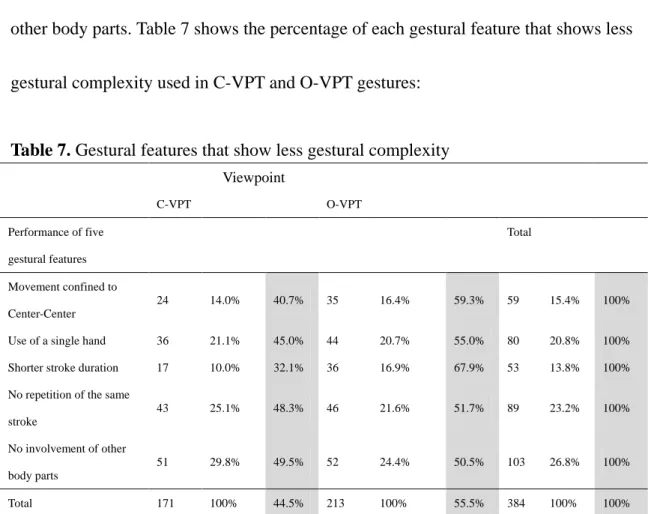

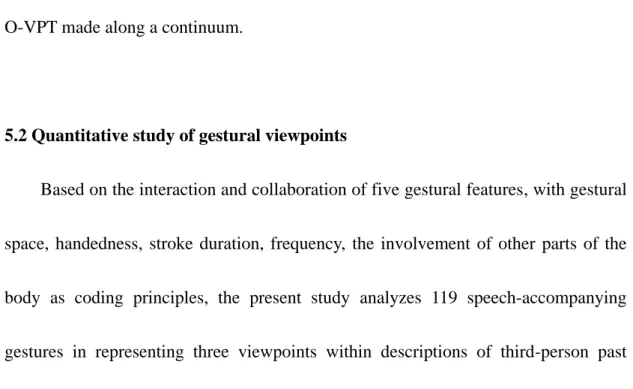

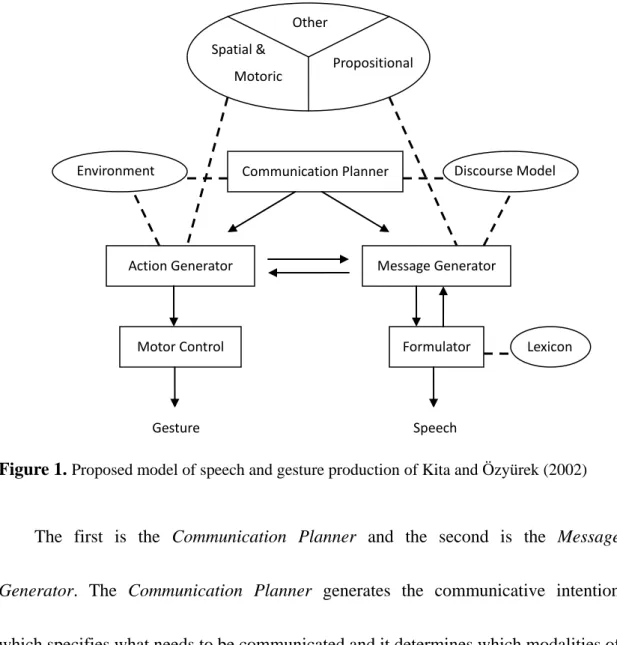

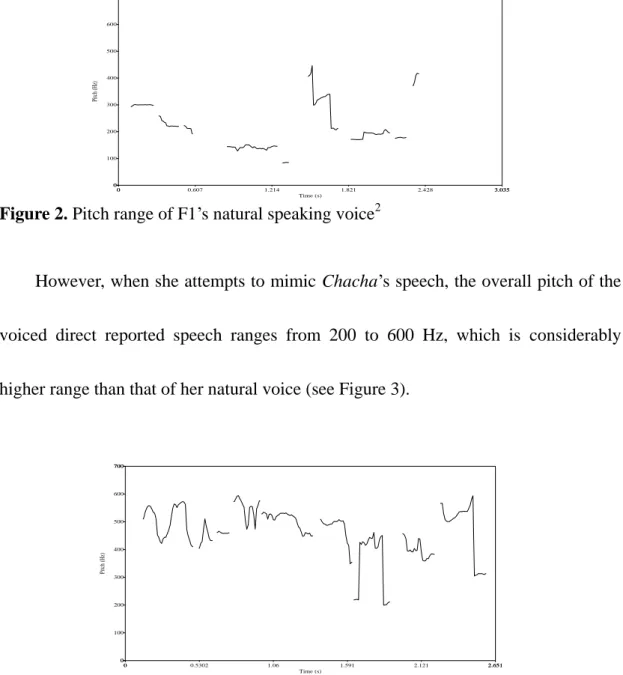

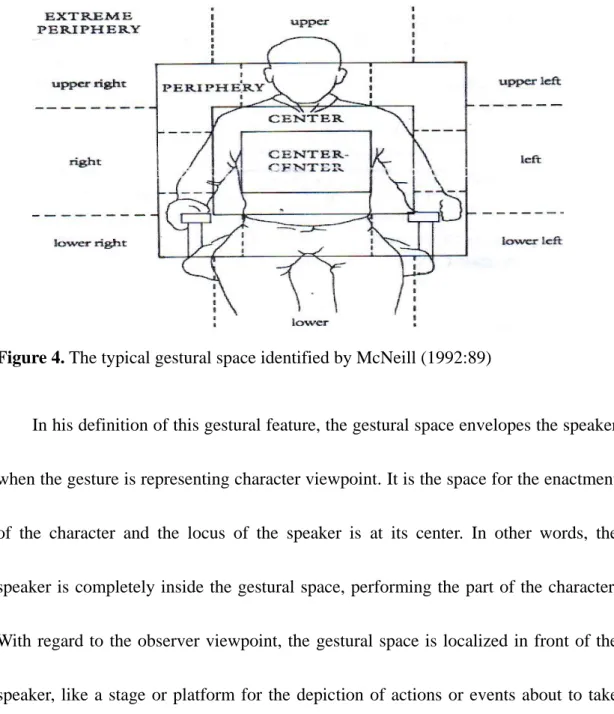

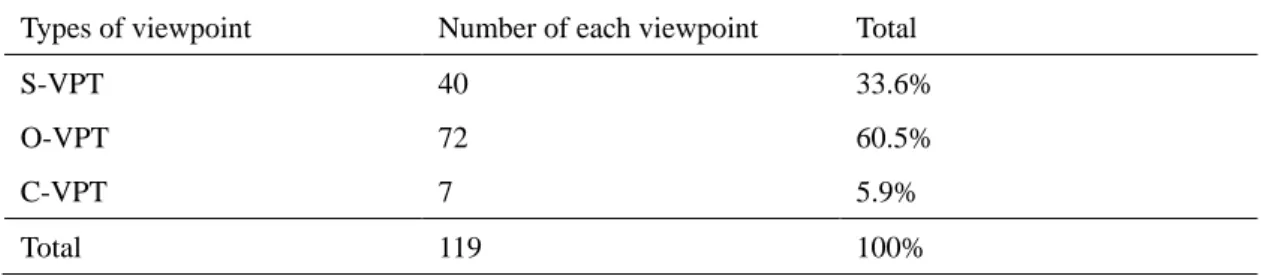

(7) 3.4.1.5 Evaluative and emotive expressions ........................................ 66 3.4.1.6 Impersonal use of second-person pronouns ............................. 67 3.4.1.7 Explicit appeal to another speaker ........................................... 69 3.4.1.8 Discourse markers .................................................................... 69 3.4.1.9 Laughter ................................................................................... 70 3.4.2 Linguistic representations of observer viewpoint ............................... 71 3.4.2.1 Indirect reported speech ........................................................... 72 3.4.2.2 Plain statements ....................................................................... 74 3.4.3 Linguistic representations of character viewpoint .............................. 75 3.4.3.1 Direct speech ............................................................................ 76 3.4.3.2 Voiced direct reported speech .................................................. 78 3.4.3.3 Inner speech ............................................................................. 81 3.5 Interim summary ............................................................................................ 81 3.6 Gestural representations of viewpoints .......................................................... 82 3.6.1 Gestural space ..................................................................................... 86. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 3.6.2 Handedness ......................................................................................... 88 3.6.3 Stroke duration .................................................................................... 89 3.6.4 Frequency............................................................................................ 90 3.6.5 Involvement of other parts of the body ............................................... 90. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 3.7 Interim summery ............................................................................................ 92 3.8 Summary ........................................................................................................ 92 CHAPTER 4 LINGUISTIC REPRESENTATIONS OF VIEWPOINTS .................... 95 4.1 Quantitative study of linguistic viewpoints ................................................... 95 4.2 The distribution of linguistic representations of speaker viewpoint .............. 98 4.3 The distribution of linguistic representations of observer viewpoint .......... 100 4.4 The distribution of linguistic representations of character viewpoint.......... 102 4.5 Summary ...................................................................................................... 103 CHAPTER 5 GESTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF VIEWPOINTS .................... 105 5.1 Gestural features and gestural viewpoints ................................................... 106 5.2 Quantitative study of gestural viewpoints.................................................... 112 5.3 Gestural instantiations of three viewpoints .................................................. 116 5.3.1 Gestural representation of observer viewpoint ................................. 117 5.3.2 Gestural representation of character viewpoint ................................ 119 5.3.3 Gestural representation of speaker viewpoint ................................... 122 5.4 Gesture types................................................................................................ 124. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 5.5 Interim summary .......................................................................................... 133 5.6 The collaborative expressions of linguistic and gestural viewpoints........... 136 5.6.1 Matching—Language and gesture conveying the same viewpoint .. 140 vi.

(8) 5.6.2 Mismatching—Gesture conveys different viewpoints from those .conveyed in language........................................................................ 144 5.7 Summary ...................................................................................................... 154 CHAPTER 6 GENERAL DISCUSSION .................................................................. 157 6.1 Summary of findings.................................................................................... 157 6.2 McNeill’s gestural study on viewpoints....................................................... 162 6.3 The Lexical Semantics Hypothesis account................................................. 167 6.4 The Interface Hypothesis account ................................................................ 176 6.5 Summary ...................................................................................................... 184 CHAPTER 7 CONCLUSION ................................................................................... 187 7.1 Summary of the thesis.................................................................................. 187 7.2 Limitations ................................................................................................... 192 Appendix 1: Gesture and speech transcription conventions ...................................... 194 Appendix 2: Abbreviations of linguistic terms .......................................................... 195 Appendix 3: The line drawings’ original screenshots from ELAN ........................... 196. 立. 政 治 大. REFERENCE............................................................................................................. 207. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i n U. v.

(9) 國 立 政 治 大 學 語 言 學 研 究 所 碩 士 論 文 提 要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:語言與手勢的觀點表現 指導教授:徐嘉慧. 博士. 研究生:謝培禹 論文提要內容:(共一冊,四萬三千兩百三十二個字,分七章) 本文旨在探討在中文的日常生活對話當中,當說話者談論到他人過去事件時, 語言與手勢的觀點表現。以 McNeill 曾經提到語言與手勢能夠共同表達觀點的說 法作為根據,本研究也探討這些伴隨著語言的手勢是否和語言表達相同或者是不 同的觀點。 本研究的架構根據 Koven(2002)的說話者角色理論(speaker role inhabitance) 和 McNeill(1992)提出的事件當中人物的觀點(character viewpoint)和旁觀者的觀 點(observer viewpoint),定義了三中觀點—當下說話者觀點(speaker viewpoint)、. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 事件當中人物觀點(character viewpoint)和旁觀者觀點(observer viewpoint)。而在手. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 勢的分析上,本研究提出五個手勢特徵—手勢使用空間範圍,手勢使用單手或是 雙手、手勢表達語意的 stroke 階段執行時間的長短、手勢 stroke 階段同一手部動 作是否有重複的現象,以及手勢是否伴隨身體上其他的動作作為五個手勢觀點分 析的關鍵指標。 量化研究發現,說話者在生活對話當中描述他人過去事件使用搭配語言的手 勢,在每一種觀點的分布和語言上的表現不同。事件當中人物觀點在語言上雖然 鮮少被採用,在手勢上卻是最常被表達的觀點。相反的,儘管當下說話者觀點在 語言上也常出現,手勢上卻很罕見。另外,旁觀者觀點則在語言上和手勢上的分 布都很頻繁。針對同一事件語言與手勢共同表達觀點的量化研究則發現,百分之 六十四點七的手勢表達了和語言不同的觀點。因此,本研究說明儘管語言和手勢 可以合作表達觀點,手勢卻更常表達和伴隨語言不同的觀點。 語言與手勢合作表達觀點的探討不僅說明語言與手勢如何互相協調組織要 表達的訊息和觀點,更進一步引領我們去探討在人與人溝通時,語言與手勢展現 的認知過程。本研究藉由兩個手勢產製的假說—the Lexical Semantics Hypothesis 和 the Interface Hypothesis,提供了針對本研究結果理論上的解釋。而每一個假說. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 也都由相關的研究結果作為證據支持。另外,the Interface Hypothesis 還可以針對 語言與手勢在表達觀點時的分工現象提出合理的解釋。. viii.

(10) Abstract This thesis explores linguistic and gestural representations of viewpoints utilizing the descriptions of third-person past events within Chinese conversational discourse. Following McNeill’s idea that language and gesture are co-expressive in viewpoints, the present study also attempts to investigate whether speakers’ speech-accompanying gesture works in collaboration with language in expressing the same or different viewpoints. The framework of this study utilizes Koven’s (2002) framework of speaker role inhabitance and McNeill’s (1992) notion of character and observer viewpoint, and defines three viewpoints—speaker, character and observer viewpoint. In analyzing gestural viewpoints, the present study recognizes five gestural features—gestural space, handedness, stroke duration, frequency, and the involvement of other parts of the body as five distinctive criteria for use in identifying different viewpoints. Quantitative study of linguistic and gestural viewpoints shows that speech-accompanying gesture in the descriptions of third-person past events within conversational contexts displays different patterns from that of those found in language in the distributions of the three viewpoints. Character viewpoint, which is rarely adopted in language, is the most often conveyed viewpoint in gesture. On the. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. other hand, despite the fact that speaker viewpoint is also commonly expressed in language, it rarely occurs in gesture. Observer viewpoint, in addition, is frequently seen in both the linguistic and gestural channels. With respect to the collaborative expressions of viewpoints in language and gesture concerning a description of the same event, quantitative study shows that 64.7% of all gestures produced in the current data represent a viewpoint different from that conveyed in language. Therefore, this study suggests that while language and gesture are co-expressive in terms of viewpoints, gesture more often collaborates with the accompanying speech in representing different viewpoints. The collaborative expressions of viewpoints in language and gesture suggest how speech and gesture coordinate with each other in organizing information and expressing different viewpoints also lead us to see the cognitive process that underlies both linguistic and gestural modalities within daily human communication. Two hypotheses—the Lexical Semantics and the Interface Hypothesis are referred to in order to provide theoretical accounts for the findings in this study. Each hypothesis is also supported by different pieces of evidence and percentages of gestures produced. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. in the current data. The Interface Hypothesis can further provide an explanation concerning the division of labor between language and gesture in expressing viewpoints, which the Lexical Semantics Hypothesis cannot supply. ix.

(11) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. 1. Introduction In Labov’s (1997) study of viewpoint in oral narratives of personal experience, “[t]he viewpoint of a narrative clause is the spatio-temporal domain from which the. 政 治 大. information conveyed by the clause could be obtained by an observer” (1997:411).. 立. Such definition of viewpoint suggests that a viewpoint is how a narrator sees the. ‧ 國. 學. spatial and temporal aspects of the propositional content conveyed by the narrative. ‧. clause. Viewpoint is how a narrator transfers a personal experience to the audience, or,. Nat. io. sit. y. in other words, how a narrator describes a personal experience to the audience. Apart. er. from the frame of narrative forms, viewpoint could be defined as speakers’. al. n. v i n perspective on things or events C theyhtalk about. Speakers e n g c h i U may speak from perspectives such as those of the characters in the original event, as an outside-the-event observer, or from their own perspective as the current speaker. How a speaker describes an event or from which perspective the event is seen, is at issue. Labov brought up the notion of viewpoint to suggest that it is a characteristic. feature of narratives of personal experience. However, Labov studied viewpoint in narratives that are told in the course of an essentially decontextualized sociolinguistic. 1.

(12) 2. interview, and suggested that only one viewpoint—that seen through the eyes of the narrator at the time of the events referred to can be conveyed. There is no switching of viewpoints in narratives of personal experience told in the course of a sociolinguistic interview. Conversation Analysts have criticized Labov’s approach to narrative discourse in regard to its high degree of decontextualization, and have argued that viewpoint should be examined in narratives produced within the context of. 政 治 大. interactional activities since oral narratives of personal experience are rarely told. 立. outside of an interactive context. In line with this view, scholars of Conversation. ‧ 國. 學. Analysis have preferred to study viewpoint in narratives that occur spontaneously in. ‧. the course of natural conversations.. Nat. io. sit. y. Goffman (1981) brought up the notion of footing, which refers to the. al. er. “participant’s alignment, or set, or stance, or posture, or projected self” (1981:128).. n. v i n footing implies a change in the alignment we take up He suggested that “a change inC hen gchi U to ourselves and the others present as expressed in the way we manage the production or reception of an utterance” (1981:128). This implies that different footings, in which the speaker can take up different alignments within a given speech, are possible. Viewpoint, which is about speakers’ perspectives in talking about things or events, is similar to what Goffman termed as footing. Different viewpoints therefore are also possible since speakers can likewise choose different perspectives on things or events.

(13) 3. they talk about. Bakhtin’s double-voiced (1981), which he defined as “another’s speech in another’s language” (1981:324) within reported speech also suggests that two “voices” or two viewpoints can arise from within a single utterance. Koven (2002) in discussing speaker role inhabitance in oral narratives of personal experience within conversational contexts, recognized that speakers may speak from different role. 政 治 大. perspectives. He then developed a framework which identifies three role perspectives,. 立. including that of interlocutor, character, and author, and suggested that speakers. ‧ 國. 學. might constantly switch their role perspectives during the course of their narration.. ‧. As Goffman (1981) mentions, while the study of viewpoint is most often. Nat. io. sit. y. language-linked, paralinguistic markers of language and nonverbal resources. al. er. including “visual back-channel cues, gesticulation, the synchrony of gaze shift, sight. n. v i n C h are also at issueUin expressing viewpoints. and even facial expression” (1981:130) engchi. McNeill (1992) was the first scholar to make a systematic study of viewpoints in resources other than language. In his study on gesture in narrative data in Hand and Mind (1992), he pointed out that viewpoints—“the feeling of distance from narrative” (118), can be conveyed gesturally. He focused on how viewpoints can be inferred from iconic gestures and sees viewpoint from a more purely gestural perspective. Despite the fact that studies on viewpoint have provided insights on how.

(14) 4. language or other, nonverbal devices like gestures are capable of expressing viewpoints, the study of how viewpoints can be conveyed simultaneously through linguistic and nonverbal channels is underdeveloped. Though McNeill has contended that “one area of meaning where speech and gesture are coexpressive is the point of view” (1992:118), his primary focus is on gestural manifestations. How language and gesture collaborate to express viewpoints has never been well investigated.. 政 治 大. The present study thus is an attempt to explore linguistic and gestural. 立. representations of viewpoints utilizing the descriptions of third-person past events. ‧ 國. 學. within Chinese conversational discourse. By focusing the analysis on the. ‧. conversational data, the present study can see how other paralinguistic devices like. Nat. io. sit. y. prosodic features, discourse markers, and laughter which accompany the speech, and. al. er. other embodied nonverbal devices like facial expressions or other bodily movements. n. v i n which accompany the gesture,C may as resources to convey viewpoints. h ealso n gserve chi U Only when viewpoint is studied in conversational data can these paralinguistic cues and nonverbal devices be seen and examined. The present study, first, investigates how language and gestures can jointly express viewpoints that arise during descriptions of third-person past events within the conversational data. Second, following McNeill’s idea that language and gesture are co-expressive in viewpoints, the present study also investigates whether the.

(15) 5. speech-accompanying gesture works in collaboration with language in expressing the same or different viewpoints within the description of an event. In seeking to answer these issues, the present study presents a multi-modal representation of viewpoints, in which viewpoints can not only be represented through language, but also through other embodied resources like gesture. In addition, the way gesture works in collaboration with language in expressing viewpoints can lead us to see the cognitive. 政 治 大. process underlying both linguistic and gestural modalities that are involved in daily. 立. human communication.. ‧ 國. 學. This thesis examines linguistic and gestural viewpoints based on following. ‧. questions. First, how gesture, as an embodied resources, works in collaboration with. Nat. io. sit. y. language in expressing viewpoints that arise from the descriptions of third-person past. al. er. events within conversational contexts? How speakers represent linguistic and gestural. n. v i n viewpoints when talking about C third-person events in an ongoing conversation? h e n g past chi U Does the pattern of the distribution of gestural viewpoints to be similar with that of linguistic viewpoints? Second, in collaborating with language to express viewpoints,. whether the speech-accompanying gesture expresses the same or different viewpoints from that conveyed in language? Third, how the collaboration of viewpoint expressions in language and gesture can lead us to see the cognitive process which underlies both linguistic and gestural channels in human communication?.

(16) 6. The present study is structured according to the following order. In Chapter 2, previous studies concerning viewpoints and theories of gesture production will be reviewed. Chapter 3 introduces the data and methodology of this study. Chapter 4 presents a quantitative study of linguistic viewpoints. Chapter 5 presents a quantitative study of gestural viewpoints and the collaborative expressions of viewpoints in language and gesture. Chapter 6 is a general discussion on how the. 政 治 大. collaborative expressions of linguistic and gestural viewpoint can lead us to see the. 立. cognitive process which underlies both linguistic and gestural channels in human. ‧ 國. 學. communication. Three hypotheses of speech and gesture production—the Free. ‧. Imagery Hypothesis, the Lexical Semantics Hypothesis, and the Interface Hypothesis. Nat. io. sit. y. are referred to in order to explain the process involved in the production of gesture,. al. er. and the relationship between speech production and gesture when gesture collaborates. n. v i n with the accompanying speech C in expressing h e n g cviewpoints. h i U Chapter 7 is a conclusion of this study..

(17) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. This chapter includes two main sections. In the first section, previous studies concerning the issue of viewpoint will be reviewed. Scholars have provided insightful views concerning this notion, and we will see how they discuss this notion in their. 政 治 大. linguistic or gestural studies. In the second section of this chapter, three theoretical. 立. hypotheses of gesture production—the Free Imagery Hypothesis, the Lexical. ‧ 國. 學. Semantics Hypothesis, and Interface Hypothesis that are used to explain the cognitive. ‧. process involved in gesture production while conveying viewpoints with the. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. accompanying speech are then introduced.. 2.1 Previous studies. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The notion of viewpoint has been studied across both literature and linguistic fields. In the linguistic disciplines, most of the previous studies are based on the study of oral narratives of personal experience (Labov & Waletzky 1967, Labov 1972, 1997). Labov first brought up the notion of viewpoint in his study of narrative analysis, and suggested that viewpoint, the point of view from which the action is seen, is how personal experience is transferred from the narrator to the audience.. 7.

(18) 8. Viewpoint has therefore, been identified as one of the most characteristic features of narrative. However, since Labov studied viewpoint in narratives told in the course of a sociolinguistic interview, he has suggested that no switching of viewpoints might occur. Scholars within the tradition of Conversation Analysis have criticized Labov’s approach. to. narrative. discourse,. where. viewpoint. is. studied. in. highly. 政 治 大. decontextualized narratives. They have argued that decontextualized narratives are. 立. more like artificial works in that no account can be provided of the conditions of the. ‧ 國. 學. interactional contexts from which the narratives emerge. In addition, narratives of. ‧. personal experience appear more often in the natural course of daily interactions. If. Nat. io. sit. y. viewpoint is studied in decontextualized narrative discourse, the results will not be. n. al. er. able to reflect the authenticity of how speakers obtain, maintain or even relinquish. Ch. engchi. their rights to tell stories in the natural course. iv n of U interactions. or the different. perspectives that speakers choose to adopt to tell the stories. Scholars in the Conversation Analytic tradition thus have urged that viewpoint should be studied in narratives that are told in natural, spontaneous conversations where different viewpoints might possibly appear. Goffman’s notion of footing (1981), Bakhtin’s double-voiced (1981), Koven’s speaker role inhabitance (2002), and Goodwin’s discussion on interactive footing (2006) all provide insights concerning this issue..

(19) 9. From studies in the Conversation Analytic tradition, viewpoint is seen as a dynamic notion where speakers or storytellers might be able to select or shift between different viewpoints when providing narrations in the course of natural conversations. While most studies of viewpoint are language-linked, scholars have also discussed viewpoint represented through channels other than language, and have seen viewpoint from different perspectives. McNeill (1992) pioneered the systematic study. 政 治 大. of viewpoint from a gestural perspective. In his Hand and Mind, he suggested that. 立. viewpoint can be conveyed gesturally, and focused his study on viewpoints that can. ‧ 國. 學. be inferred from iconic gestures. His work was unprecedented, since most of the. ‧. previous studies had either neglected the multi-modal nature of representations of. Nat. io. sit. y. viewpoint and focused the discussion on language, or had not systematically studied. al. er. viewpoints that are represented through non-verbal channels.. n. v i n In the following sections,C theh present study will e n g c h i U first see how viewpoints are. defined in narratives without taking interactive contexts into consideration. Then the present study will focus on the Conversation Analytic approach in studying viewpoints. McNeill’s gestural study on viewpoint which concerns the multi-modal nature of viewpoint representations will then be introduced. Labov’s approach in studying viewpoint in a decontexualized sociolinguistic interview is introduced in 2.1.1. In section 2.1.2 to 2.1.6, there follow separate introductions of studies that.

(20) 10. follow in the tradition of Conversation Analysis. Section 2.1.2 introduces Goffman’s footing, section 2.1.3 Bakhtin’s double-voiced, section 2.1.4 Koven’s speaker role inhabitance in narratives, section 2.1.5 Goodwin’s interactive footing, which is built on Goffman’s notion of footing, and section 2.1.6 McNeill’s gestural study, following all linguistic studies on viewpoint. Section 2.1.7 contains a summary of these previous studies.. 立. 政 治 大. 2.1.1 Labovian narrative framework and evaluation (1967, 1972, 1997). ‧ 國. 學. Labov (Labov & Waletzky 1967, Labov 1972, 1997), in developing a framework. ‧. to analyze narratives of personal experience, brought up the notion of the evaluative. Nat. io. sit. y. function of narratives, which is the precedent notion similar to viewpoint. In his. al. er. framework, he suggested that stories not only have a denotative content which serves. n. v i n C h but also haveUan evaluative function. In his as the referential function of narratives, engchi earlier work with Waletzky (1967), he defined the evaluation of narratives as “the part of the narrative that reveals the attitude of the narrator by emphasizing the relative importance of some narrative units as opposed to others” (Labov & Waletzky 1967:37). It is through this evaluative function that storytellers are able to show their perspectives on the events narrated. The concept of evaluative function can therefore be considered as the precedent notion similar to that of viewpoint as discussed in the.

(21) 11. present study. In addition, through the use of evaluative clauses, a storyteller can achieve the evaluative function. The evaluative clauses are described as “narrative clauses in an irrealis mood” (Labov 1972:403), and many linguistic devices are identified as evaluative clauses that can achieve evaluative function. Reported speech is one device among many that a storyteller can use to evaluate a narrative. While several linguistic. 政 治 大. devices are identified to achieve evaluative function, as Labov himself has noted, the. 立. evaluation is rarely to be found in any denotationally explicit proposition. Rather, it is. ‧ 國. 學. often embedded throughout the very telling of the story. As a result, the same. ‧. linguistic form might contribute to both referential and evaluative functions. Nat. io. sit. y. concurrently, which leads to difficulty in distinguishing them. Whether the storyteller. al. er. is evaluating the events or narrating, it is difficult for the denotative content to be. n. v i n distinguished. How a storytellerCcan linguistic device to purely make an h eusenagsingle chi U evaluation and show his perspective toward the narrative is hard to be seen.. In his later work (1997), Labov also come up the term viewpoint, which he explained as the process by which personal experience is transferred from the narrator to the audience. He defined viewpoint as “the spatio-temporal domain from which the information conveyed by the clause could be obtained by an observer” (1997:411). Following this view, viewpoint is how the storyteller sees the events narrated, or the.

(22) 12. perspective that they choose to present the narratives. In addition, Labov identified that events can only be seen through the eyes of the narrator in oral narratives of personal experience (1997). In other words, there is only one viewpoint, which that of the perspective of the narrator in oral narratives of personal experience. There is no switching between viewpoints. Speakers in narrating personal experience do not “take an impersonal viewpoint, and enter into the. 政 治 大. consciousness of any or all of the actors” (Labov 1997:411).. 立. Different from Labov’s study which focuses on first-person oral narratives, the. ‧ 國. 學. present study does not analyze viewpoints in narratives of personal experience. In. ‧. talking about personal experiences, the present study suggests that speakers might. Nat. io. sit. y. speak from the perspective of a narrator or the perspective of characters in the. n. al. justified. Since both the. er. personal event. However, in this case, the two perspectives would be hard to be. i n C narrator the character is h eandn g chi U. v. the speaker himself in. first-person experience, the “present I” as a narrator and the “past I” as the character is indistinguishable. To avoid ambiguity in analysis, the present study focuses on the study of third-person past events. Personal experiences are excluded in the current data. What leads to the finding concerning only one viewpoint could be adopted in Labov’s study, in particular that of the viewpoint of the narrator in oral narratives,.

(23) 13. might seriously due to the fact that Labov’s approach in narrative discourse focuses on the narrative forms that were told in the course of a sociolinguistic interview. These oral narrative discourses are “essentially monologues and show a degree of decontextualization” (Labov 1997:397), and are artificial works. Conversation Analysts have criticized Labov’s approach to narrative discourse with regard to its high degree of decontextualization, and have argued that viewpoint. 政 治 大. should be examined in narratives within interactional activities since oral narratives of. 立. personal experience are rarely told without interactive contexts. Narratives more often. ‧ 國. 學. appear or are embedded within interactive contexts. The decontextualized narratives. ‧. cannot account for the interactive contexts from which they emerge and cannot reflect. Nat. io. sit. y. the possibility that different perspectives might be involved as speakers are narrating. al. er. in interactive contexts. Conversation Analysis scholars thus have urged that viewpoint. n. v i n should be studied in narrativesCthat in the course of natural h eoccur n g spontaneously chi U. conversations. In this light, how a storyteller might possibly adopt different perspectives while narrating within conversational contexts could be seen.. 2.1.2 Goffman and the notion of footing (1981, 1986) Following the Conversation Analytic tradition, Goffman (1981) brought up the term footing in illustrating the alignment that speakers take up to themselves and other.

(24) 14. co-participants during the production of an utterance. Based on his definition, footing can be summarized as the “participant’s alignment, or set, or stance, or posture, or projected self” (1981:128). He suggested that during the course of multi-party interaction, participants might constantly change their footings, and these changes are considered as a persistent feature of natural talk. He further pointed out that storytelling within the conversational context provides a clear example to illustrate. 政 治 大. participants’ frequent change and negotiation of footings. Since during the telling of a. 立. tale in natural interaction, speakers are “likely to break narrative frame at strategic. ‧ 國. 學. junctures” to “recap for new listeners, to provide encouragement to listeners, to wait. ‧. for the punch line, or gratuitous characterizations of various protagonists in the tale,. Nat. io. sit. y. or to backtrack to make a correction for any felt failure to sustain narrative. al. er. requirements such as contextual detail, proper temporal sequencing, dramatic build-up,. n. v i n C h The speaker whoU does the narration therefore, and so forth” (Goffman 1981:152). engchi. must often shift between, and simultaneously take up multiple footings, or embed one footing within another, which often results in a multi-layered “one man show” (Goffman 1986:547). As suggested, the “change in footing is very commonly language-linked; or if not, at least can be figured through paralinguistic markers of language, or nonverbal devices like gestures, visual back-channel cues, the gaze shift or even the facial expression” (Goffman 1981:128)..

(25) 15. In recognizing the dynamic nature of footing in that footing might frequently shift, Goffman offered an important framework of participation that is central to the dialogic organization of human language and breaks the roles of ‘speaker’ and ‘hearer’ into a set of distinctive capacities. For the ‘speaker’, a complex set of different entities are distinguished within a single strip of reported speech, including three distinctive roles—animator, principal, and author. Animator refers to the party. 政 治 大. whose voice is actually being used to produce the speech, or the “sounding box”. 立. (1981:144) in Goffman’s term. Principal refers to the party who is socially. ‧ 國. 學. responsible for having performed the action carried out in events described in the. ‧. original utterance of the talk, and could be said to be the character in the scene of the. Nat. io. sit. y. original talk. Author of the talk refers to the party who constructed the phrase said,. al. er. rather than the current storyteller. These three roles are constructed as different voices. n. v i n arising in the production of a C given h ereported i U which speakers often use in n g c hspeech, storytelling within conversational contexts. Goffman further noted that the talk of speakers in everyday conversation can encompass an entire theater, and that speakers very often embed one footing within another. Likewise, the notion of ‘hearer’ is also divided into several role capacities, including official participants, eavesdroppers, over-hearers, bystanders, and audiences. In brief, Goffman provided a powerful model for systematically analyzing the complex theater of different kinds of.

(26) 16. ‘speakers’ that can co-exist within a single strip of reported speech in a story, and separated different role capacities that could all be generalized as ‘hearers’. While the notion of footing and the framework developed by Goffman shed light on the complex lamination of different role capacities that could arise from structurally the same utterance in narratives within conversational contexts, several questions have been subject to criticism. First, while the notion of ‘speaker’ is. 政 治 大. decomposed into a laminated structure encompassing different kinds of entities, the. 立. notion of ‘hearer’ has been criticized as not being distinguished in an equivalent. ‧ 國. 學. fashion. Even though several categories concerning hearers have also been brought up,. ‧. they are treated as “structurally simple and undifferentiated” (Goodwin 2006:26). The. Nat. io. sit. y. different kinds of ‘hearers’ are mainly categorized in a static fashion which does not. al. er. seem to be built through the interactive participation within the ongoing course of the. n. v i n C has in the case forU‘speakers’, it is hard to find description of the action. Unlike engchi structurally different ‘hearers’ within a single utterance.. Second, Goffman seems to have provided only a typology of participants, and the precise role that language and other non-verbal resources play in the speaker’s representations of particular footings is vague. In other words, Goffman did not apply a systematic framework to discuss how footings can be manifested through linguistic devices or other semiotic signs, with the result that there is no linguistic support for.

(27) 17. his analysis. What language or other paralinguistic, and even non-verbal resources could be used to represent certain kinds of footings is not investigated. Following the Conversation Analytic tradition, Goffman discussed footing in conversational contexts to see how different voices might arise in reported speech in storytellings within conversations, and moreover, how multiple footings might possibly be shifted between or simultaneously taken up within a single utterance. His. 政 治 大. study is insightful in pointing out that footing, to be studied in narratives within. 立. conversations, is not a static notion where only one voice can be found within a single. ‧ 國. 學. strip of reported speech. Different speaker roles could arise, shift between, or even be. ‧. embedded one within the other during the course of storytelling within conversations.. Nat. io. sit. y. Indeed, the notion of viewpoint, which is concerned the speakers’ perspective on the. al. er. things they talk about, is exactly what Goffman has termed as footing. As different. n. v i n footings are possible, differentCviewpoints also arise as speakers talk about h e n gcould chi U different events within conversations.. 2.1.3 Bakhtin and double-voiced (1981) Bakhtin (1981) came up with his notion of double-voiced, which also concerns how different viewpoints can arise from a single reported utterance. He explained the notion of double-voiced as “another’s speech in another’s language”, which “serves to.

(28) 18. express authorial intentions but in a refracted way” (1981:324). He suggested that double-voiced discourse “serves two speakers at the same time and expresses simultaneously two different intentions”; “one the direct intention of the character who is speaking, and the refracted intention of the author” (1981:324). In fact, Bakhtin’s notion seems to be similar to that of Volosinov’s study on the interactive organization of language in 1973. In Volosinov’s study, he attempted to investigate. 政 治 大. how a speaker could incorporate the talk of another into a current utterance and how. 立. another’s talk can be transformed. He argued that reported speech is an appropriate. ‧ 國. 學. device to use to study this issue, in which a single utterance constitutes a site where. ‧. the voices of multiple speakers can dynamically interact with each other. He thus. Nat. io. sit. y. made a binary distinction between reporting and reported speech events, in which. al. er. reporting event refers to the current utterance happened; whereas reported speech. n. v i n C hquoted. FollowingUVolosinov’s distinction, Bakhtin event refers to another’s talk being engchi argued that speakers are able to integrate a prior narratable speech event into the current speech event, negotiating the dynamic inter-relation between the two sets of speech events and speakers. Scholars who followed Bakhtin’s notion have further adopted a comparably binary set of speaking roles of narrator and character concerning the correspondence between the narration of the speech event and the narrated event..

(29) 19. While. the. binary. related. distinction. between. narrator/character. and. narrating/narrated event have been frequently emphasized in work in the Conversation Analytic tradition, he himself also suggested that the possibility of more complex participation frameworks and possible speaking roles and events within the same utterance involved could be probed in a further step. Related to the present study, Bakhtin’s double-voiced also suggests that different speaking roles, or perspectives, or. 政 治 大. viewpoints, are possible in different speech events.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 2.1.4 Koven and the analysis of speaker role inhabitance (2002). ‧. Based on Labov’s idea of evaluation, Goffman’s notion of footing and Bakhtin’s. Nat. io. sit. y. idea of double-voiced, Koven (2002) developed a framework of speaker role. al. er. inhabitance which is also concerned with the speakers’ perspectives in narratives. n. v i n Ch during the course of ongoing conversations. respect to his notion of speaker role e n gWith chi U. inhabitance, he attempted to distinguish between the referential and socio-pragmatic dimensions of oral narratives of personal experience. In narrating a personal experience within a conversational context, a speaker not only tells the denotative meanings of the story, which corresponds to the referential function of the narrative, but also attempts to maintain the ongoing conversation. The speaker should not only take up a stance toward the narrated events, but also toward his current.

(30) 20. co-conversationalists to maintain the ongoing conversation. The way that a speaker should constantly take up different stances during the course of narrating in a conversation is therefore the socio-pragmatic aspect of the narratives. How a storyteller strategically tries to align himself with particular perspectives in telling a series of personal experiences thus is the focus of Koven’s study. He distinguished three role perspectives—interlocutor, author, and character that speakers orchestrate. 政 治 大. in the performance of a narrative of personal experience, and defined these roles. 立. according to the speech events that they emerge from:. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. (1) There is the larger context of the interview or conversation in which the stories are told. (Here the relevant speaker roles are those of co-conversationalists or interlocutors.). y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. (2) There is the event of narration itself, in which the speaker takes on the role of storyteller, obtaining an extended turn at talk in which he/she narrates. (Here the relevant speaker roles are those of narrator/author and listener/audience).. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. (3) There is the narrated speech event, which is presupposed and invoked in the event of narration. (Here the relevant speaker roles are those of the narratable and perfomable characters).. Koven suggested that speakers in narrating personal experience in conversational context must constantly perform, coordinate and shift among these three roles and might use a range of indexical linguistic resources to perform and move between each role. He thus used a series of examples from his corpus of narratives of personal.

(31) 21. experience in French and Portuguese to describe the devices which speakers might use in French and Portuguese to occupy these three roles. For interlocutory role inhabitance, he suggested that many devices could work to represent this role inhabitance but they “contribute relatively less referential or propositionally explicit information, and more purely interactional and attitudinal information” (Koven 2002:180) than devices from an authorial role perspective.. 政 治 大. These devices, for example, involve parenthetical remark, in the use of which the. 立. speaker steps out of the narrative frame to make explicit comments, and where there. ‧ 國. 學. is a shift to a markedly higher or lower register to indicate the speakers’ attitude or. ‧. affect where its degree is more increased than that in the narrated event; quantifying. Nat. io. sit. y. intensifiers that serve to quantify a speaker’s gradient affective involvement;. al. er. discourse markers like quoi ‘okay’ that are not part of the advancement of the plot. n. v i n C assessment which point to speakers’ current events; and other paralinguistic h e n g cofhthei U devices like laughter and gasps. For authorial role inhabitance, he pointed out that the devices often include the combination of a first-person pronoun or verb form and a past tense or historical present verb. The tenses in French and Portuguese include the passé composé in French or the preterite in Portuguese, the imperfect and the pluperfect in both French and Portuguese. By the use of the verb form and these tenses, speakers are able to present the event as having occurred at a place and time.

(32) 22. clearly distinct from the current event of speaking. In terms of character role inhabitance, multiple modes of reported speech including both direct and indirect quote can be used to represent this perspective. In identifying a wide range of linguistic devices that instantiate different role inhabitance, Koven provided clear evidence to illustrate that the speaker’s perspectives in narrating personal experience within the ongoing conversation can be linguistically-manifested.. 立. 政 治 大. In addition to exploring different speaker role inhabitances and linguistic. ‧ 國. 學. indexical devices that instantiate speakers’ perspectives in talking about personal. ‧. experiences within conversational contexts, Koven further attempted to prove that the. Nat. io. sit. y. role distinction is salient for listeners of the story. He asked a French-Portuguese. n. al. er. bilingual to perform narratives of personal experience in her two languages, in which. Ch. engchi. her Portuguese version of the story was more. iv n weighted U. toward character role. inhabitance. He then asked listeners to talk about the differences they noticed between two tellings of the same event, in particular about their impressions of the speakers’ attitudes as a storyteller and as a character in the story. The result turns out to be that listeners were able to note the distinction between the speaker’s current attitude at the moment she told the story (interlocutory role inhabitance), as opposed to her presentation of herself at the time of the original narrated event (character role.

(33) 23. inhabitance) in both of the French and Portuguese versions. In addition, they agreed that the speaker was more involved and the story was more animated and faithful in the Portuguese version overall, since more characters in the story are quoted and character role inhabitance is more loaded in the Portuguese story. In sum, Koven employed an experimental task to demonstrate that the notion of role inhabitance is not a single dimensional as to just about how speakers locate and perform themselves,. 政 治 大. but is also salient for listeners in that they are able to distinguish the different roles. 立. involved in the narratives of personal experience.. ‧ 國. 學. Concerning the diachronic study on the notion of viewpoint, Koven is insightful. ‧. in providing a linguistically systematic framework to clearly identify and instantiate. Nat. io. sit. y. three role inhabitances—that of the interlocutory, authorial, and character roles. er. involved in the narratives of personal experience. In addition, as innovative. al. n. v i n C hnot been explicitlyUbrought up in previous studies, interlocutory role involvement was engchi. his framework explains how a speaker in narrating personal experiences within a larger conversational context aligns himself concerning the past event, as well as positions. himself. within. the. ongoing. interaction.. Speakers’ simultaneous. involvements in both the narrated event and the ongoing conversation are taken into consideration. Problems also arise from Koven’s framework, in particular concerning the.

(34) 24. linguistic manifestations he analyzed. Since Koven studied speaker role inhabitance of personal experience from a French-Portuguese bilinguals’ narratives corpus, the linguistic instantiations he analyzed are inevitably language-specific. Many of the indexical devices that he identified might not be applicable to narratives data in other languages. For example, with respect to the linguistic manifestations of authorial role inhabitance,. Koven. suggested. that. certain. verb. conjugation. and. tense. 政 治 大. performance—past tense or historical present verb in particular, is an instantiation of. 立. authorial role inhabitance. However, there are certain languages like Chinese in. ‧ 國. 學. which tense performance is not represented through verb forms but through other. ‧. devices like time expressions. And, time expressions, moreover, do not always appear. Nat. io. sit. y. in every Chinese utterance. It would be hard to justify that authorial role inhabitance. n. al. er. does not exist if time expressions are not observed. Koven’s analysis of different. Ch. engchi. indexical devices as linguistic manifestations of. iv n three U speaker. role involvements. might seem to be able to account for the linguistic representations of speakers’ perspectives only in certain languages. While Koven’s linguistic representations concerning different role inhabitances are language-specific, his framework takes speakers’ perspectives that might arise due to the ongoing conversational contexts and the narrated events into consideration. The present study therefore, follows Koven’s framework in identifying the ways in which.

(35) 25. different viewpoints emerge as speakers describe past events within an ongoing conversation, and especially addresses the use of his interlocutory role that has never been mentioned in previous studies. By studying viewpoints in Chinese conversational data, the present study also aims to come up with linguistics representations that could complement or amend Koven’s language-specific manifestations.. 立. 政 治 大. 2.1.5 Goodwin and interactive footing (2006). ‧ 國. 學. In reviewing Goffman’s footing and his deconstruction of speakers within a. ‧. single reported utterance (1981, 1986), Goodwin also came up with certain insightful. Nat. io. sit. y. opinions building on and responding to Goffman’s framework. He developed his. al. er. argument by suggesting two inadequacies of Goffman’s model. First, he criticized. n. v i n C h only a typologyUof laminated speakers within a Goffman’s model in that it provides engchi. single strip of utterance rather than “analysis of how utterances are built through the participation of structurally different kinds of actors within ongoing courses of action” (Goodwin 2006:17). Speakers and hearers can both contribute to the further proceeding of the ongoing interaction. Second, he pointed out that Goffman’s discussion of footing requires utterances that have rich syntax; like reported speech, where clauses in which the talk of another is embedded within a larger utterance by.

(36) 26. the current speaker. Indeed, many previous scholars like Volosinov (1972) and Bakhtin (1981) also place emphasis on the study of reported speech. As an improvement of the two flaws in Goffman’s framework, Goodwin further suggested that the nature of participation should be analyzed as “a temporally unfolding process through which separate parties including both speakers and hearers demonstrate to each other their ongoing understanding of the events they are engaged in by building. 政 治 大. actions that contribute to the further progression of these very same events” (2006:27).. 立. He thus brought up a discussion of interactive footing that seeks to probe how the. ‧ 國. 學. voices or the perspectives of different participants, including both speakers and. ‧. hearers, within a multi-party dialogue can shape each other and jointly unfold the. Nat. organized visible actions like eye gaze and gestures.. al. er. io. sit. y. interaction of the further proceeding of the narrative description through the use of. n. v i n In many examples in his C study footings, Goodwin attempted to h eofninteractive gchi U. demonstrate that the notion of footing should not be restricted to the talk and consciousness of a single speaker, rather it can be investigated more richly by focusing on multiple sequences of talk by different parties. In addition, Goodwin offered a powerful insight into the notion of footing, in which the speaker’s position can be shaped by mutual participation with different parties through not only language, but also through other visible embodied interaction which are used together to.

(37) 27. contribute to and build the ongoing interaction. Even though the focus of the present study does not attempt to see how speakers’ footings or perspectives can be shaped by mutual participation within the dialogue, Goodwin’s discussion on interactive footing is also insightful for the present study. Goodwin suggested that speakers’ voices or perspectives can not only be represented or shaped by only language, but also by other nonverbal devices like eye gaze or. 政 治 大. gestures. Following McNeill’s (1992) systematic study of gestural representations of. 立. viewpoints (discussed in the following section), Goodwin also noted the multi-modal. ‧ 國. 學. representations of viewpoints and further attempted to demonstrate that these. ‧. Nat. al. er. io. sit. during mutual participation in a conversation.. y. embodied representations can serve as devices to shape participants’ viewpoints. n. v i n 2.1.6 McNeill and the gesturalC manifestations (1992) U h e n g c hofiviewpoints In his Hand and Mind (1992), McNeill suggested that gestures, unconstrained by language-like conventions, can not only convey semantic meanings, but also express pragmatic content. In examining the relationship of gesture to ongoing, real-time storytelling, McNeill also suggested that viewpoint is one area of meanings where gesture can co-express with speech. Since McNeill’s main focus is on narrative data, he denoted the notion of viewpoint as “the feeling of distance from the narrative”.

(38) 28. (1992:118). A given narrative can be portrayed as if it were being experienced, or as if it were being seen from a distance. Two viewpoints—the character viewpoint (C-VPT) and observer viewpoint (O-VPT) are therefore recognized. In addition, definitions of C-VPT and O-VPT are described on the basis of the different performances of iconic gestures. In representing C-VPT, the iconic gesture may seem to re-enact the character, and the depiction is dispersed over the narrator’s body in an appropriate way. The. 政 治 大. narrator’s hand plays the part of the character’s hand, and the narrator’s body enacts. 立. the part of the character’s body. On the other hand, in representing O-VPT, the gesture. ‧ 國. 學. may appear to display an event such as showing that the narrator seeks to keep some. ‧. distance from the story. The depiction of characters is concentrated in the hand, and. Nat. io. sit. y. the narrator’s body is an onlooker outside the narrative. In addition to how the. n. al. distinguishing C-VPT or. er. characters of a narrative are represented through iconic gestures could be a criterion in. v i n C h gestural spaceUis also O-VPT, engchi. a key element in. distinguishing these two viewpoints. A C-VPT gesture incorporates the speaker’s body into the gestural space, and the speaker’s hands represent the hands of the character. An O-VPT gesture in contrast, excludes the speaker’s body from the gestural space and his hands play the part of the character as a whole. McNeill further suggested that in the narrative data he studied, 60% of iconic gestures have an O-VPT, and 40% a C-VPT..

(39) 29. Despite the fact that McNeill defined viewpoints from a gestural perspective, his notion of character viewpoint is equal to that of Koven’s (2002) character role inhabitance defined from a linguistic perspective, in which both are concerned with the speakers’ attempts to enact the characters of the narratives whether through the speech or gestural channel. On the other hand, McNeill’s observer viewpoint also can be equated to Koven’s authorial role inhabitance. In Koven’s authorial role. 政 治 大. inhabitance, speakers are storytellers or narrators outside of the event, which is also. 立. to express the viewpoints are different.. 學. ‧ 國. the core value of McNeill’s observer viewpoint despite the fact that the channels used. ‧. Indeed, McNeill’s purpose in studying gestural viewpoints is to see how gesture. Nat. io. sit. y. can reflect the discourse structure as narrators proceed through the narrative. Different. al. er. kinds of gesture or gesture performances might reveal the narrative structure, and the. n. v i n C h also serves asUa clue. According to McNeill, representation of gestural viewpoints engchi storytelling refers to the entire set of events that make up the conveying of a story by one person to another, and it is structured on multiple levels. References to events or incidents from the fictive world of the story are called the narrative level. Sentences at this level follow a certain order that together compose the story line, which is called the temporal constraint, so that listeners are able to understand that those sentences are part of the story. In addition to narrate the story plot, narrators also make explicit.

(40) 30. references to the structure of the story. Clauses present the story about the story that are interwoven within the narrative level constitute the meta-narrative level. For example, in McNeill’s narrative data, a narrator says and uh the first scene you see is uh to comment on the story structure and manipulate the story as whole a unit. Storytellers also make references to their own experience to the event of storytelling itself, and this is called the para-narrative level. At this level, narrators speak for. 政 治 大. themselves and try to focus on their relationship to listeners. For example, they might. 立. ask listeners whether they have ever heard any story similar to the one that is being. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. told before.. In identifying these three narrative levels—narrative level, meta-narrative level,. Nat. io. sit. y. and para-narrative level, McNeill pointed out that different kinds of gesture tend to. al. er. appear in one level over others. Iconic gestures in most of the cases appear at the. n. v i n C ha series of story events. narrative level, where they exhibit e n g c h i U C-VPT and O-VPT thus are most often observed in the narrative level with the frequent occurrences of iconic gesture. In addition to the observation that C-VPT tends to appear in the narrative level and events of greater importance, the shifts between C-VPT and O-VPT within a narration are not at all random. McNeill followed Church’s (Church et al. 1989) classifications of event as central or peripheral, and suggested that more central events.

(41) 31. are given the C-VPT; while more peripheral ones are given the O-VPT. Central events can be either the initiation of goal actions, main goal actions, or outcomes of goal actions; while peripheral ones include setting statements, subordinate actions, responses to actions and outcomes. Two viewpoints appear in different contexts, on the basis of these definitions regarding central or peripheral events. McNeill provided statistics to show this—71% of C-VPT gestures appeared with central events, and. 政 治 大. 93% percent of O-VPT gestures appeared with peripheral events. A speaker’s. 立. narration which comes from McNeill’s narrative data can serve as an example to. ‧ 國. 學. illustrate. The narrator is describing a series of events of a scene from a cartoon, in. ‧. which one character Sylvester, tries to reach a second character Tweety, by climbing. Nat. io. sit. y. up the inside of a drainpipe. Two successive events about one of the characters. al. er. Sylvester—he [comes out the bot]tom of the drainpipe, and he’s [got this] big bowling. n. v i n C hdifferent viewpoints. ball inside him are described from e n g c h i U As the narrator talked about ‘come out’, he made an O-VPT gesture. Since the first event was considered as the intervening event that was used to support the more important upcoming event, it got the O-VPT. As for the second event, it concerned the cause and effect of the whole. story and was considered as the main point of the scene. Thus, it got the C-VPT. Many other examples in McNeill’s narrative data support this finding. In McNeill’s data, though all of the gestures were iconics and all of the clauses were at the.

(42) 32. narrative level, the events were not equal in terms of their importance for the advancing of the story line. Gestures with C-VPT or O-VPT can suggest this difference and the study of these gestures can be used to study the narrative structure. While McNeill studied gestural viewpoints within narrative data, he also provided linguistic manifestations of viewpoints. In his quantitative study, he generalized that the C-VPT gesture tends to appear with transitive verbs and single. 政 治 大. clause sentences, and the O-VPT gesture with intransitive or stative verbs and. 立. multi-clause sentences (complex sentence). He further suggested that it is through. ‧ 國. 學. gestural manifestation that linguistic manifestation may be made obvious and clear.. ‧. Without the speech-accompanying gestures that represent different viewpoints, these. Nat. hard to draw any attention to them.. al. er. io. sit. y. linguistic forms that are also capable of conveying viewpoints are unobvious and it is. n. v i n C h therefore, gestural According to McNeill’s study, e n g c h i U and linguistic manifestations. achieve equivalent results in terms of ‘distance’ for a given viewpoint. In the C-VPT gesture, speakers walk into the scene of the narrative and insert themselves into the gestural space. In the linguistic parallel there are single clauses and transitive verbs that also function to represent the speakers as walking into the events narrated. With a single clause, “there is a minimal grammatical separation of the event from the speaker” (1992:120). With a transitive verb, the events being narrated are as if under.

(43) 33. magnification. A typical example given by McNeill as an illustration of a C-VPT is and drops it down the drainpipe. In the gesture, the narrator’s hand appeared to grasp the bowling ball and shove it down the drainpipe, which description is provided from the viewpoint of the character, and the action is accompanied in language by a single clause and a transitive verb ‘drop’. In terms of an O-VPT in gesture, speakers exclude themselves from the gestural space to express that they are outside of the events. 政 治 大. narrated. Linguistically, the O-VPT correspondingly appears with complex sentences. 立. and intransitive or stative verbs which allow speakers to keep some distance from the. ‧ 國. 學. events described. Complex sentences, according to McNeill, “interpose distance from. ‧. the action in its own configuration” (1992:120). One example cited by McNeill is he. Nat. io. sit. y. tries climbing up the side of the building, where the act of climbing is presented in the. al. er. embedded clause and the upper clause (he tries) implies that the action is seen from. n. v i n the point of view of an outsideCobserver story. While McNeill acknowledged h e n ofg the chi U. that the correspondence between gestural and linguistic manifestations with regard to the same viewpoint is not always definite, the speech-gesture co-expressions of the same viewpoint are pretty much correspondent in terms of the distance from the narratives. The present study does not analyze transitive/instransitive or stative verbs and single clause/multi-clause sentences as linguistic manifestations of viewpoints, as.

(44) 34. suggested by McNeill. In McNeill’s study, linguistic and gestural representations of viewpoints are not independently analyzed. In addition, linguistic manifestations of certain viewpoints are distinguishable and obvious only when the gestural representations are first identified. The present study, different from McNeill’s analysis, analyzes linguistic manifestations of viewpoints by observing and analyzing various linguistic structures and paralinguistic devices that could possibly represent. 政 治 大. different viewpoints that speakers make use of in talking about third-person past. 立. events within conversational contexts, rather than deducing them from gestural. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. representations.. To sum up, McNeill brought up the notion of viewpoint in his study on gestures. Nat. io. sit. y. within narratives, and proved that viewpoint can not only be conveyed through. al. er. language, but also can be manifested through embodied channels like gestures.. n. v i n However, since McNeill’s focusC is h on gestures, his definition e n g c h i U of viewpoint is primarily and purely seen only in regard to the gestural aspects. In other words, he provided a definition of the notions of character and observer viewpoint by describing different gestural performances. The problem in this approach is that linguistic manifestations are presented as merely additive correspondents with speech-accompanying gestures, rather than independent realizations of a certain viewpoint. McNeill is using gestural definition to deduce linguistic manifestations, instead of directly analyzing linguistic.

(45) 35. devices that could possibly convey viewpoints. In other words, McNeill has not systematically. studied. the. collaboration. between. linguistic. and. gestural. representations in expressing viewpoints. In addition, McNeill focused his study of viewpoint only on iconic gestures, overlooking the capabilities of other gesture types in expressing viewpoints. Despite the fact the performance of other gesture types to represent viewpoints might not be as. 政 治 大. multi-dimensional as iconic gestures, other gesture types like metaphoric, deictic and. 立. spatial gestures are also potential in expressing viewpoints. The study of the use of. ‧ 國. 學. iconic gestures, indeed, might also be more fruitful for the finding of examples of. ‧. expression of viewpoints.. Nat. io. sit. y. McNeill’s study is insightful in that it recognizes the multi-modal nature of the. al. er. representations of viewpoints. He has shown that the representations of viewpoints are. n. v i n C hthe embodied, non-verbal not confined to language, and that e n g c h i U devices like gestures can also powerfully express viewpoints. His identifications of character and observer viewpoint are also important, since they suggest the existence of different viewpoints that can also be inferred from gestural aspects. Even though the definitions of these two terms are illustrated from a purely gestural perspective, the present study follows McNeill’s concept of these two viewpoints and attempts to supply a definition that can better account for both the linguistic and gestural viewpoints..

(46) 36. 2.1.7 Interim summary Linguistic studies have provided various insights on the issue of viewpoint. In Labov (Labov & Waletzky 1967, Labov 1972, 1997), the notion of viewpoint was studied in narratives within a sociolinguistic interview. However, this approach has been criticized concerning the opinion that viewpoint should not be studied in decontextualized narratives. Scholars within the Conversation Analytic tradition have. 政 治 大. urged the study of viewpoint in narratives within the course of natural and. 立. a. framework. that. deconstructs. 學. developed. ‧ 國. spontaneous conversations. Goffman (1981) brought up the notion of footing, and “speakers”. into. three. speaker. ‧. roles—animator, principal, and author within a single reported speech. However, he. Nat. io. sit. y. placed too much emphasis on how different speaker roles might be invoked within a. n. al. er. single reported speech, rather than how a single speaker can use different linguistic. Ch. engchi. devices to speak from different perspectives.. iv n Bakhtin (1981) U. also proposed. double-voiced to discuss the point that speakers are able to integrate a prior narratable speech event into the current speech event, in which two voices are invoked from two sets of speech events. Koven (2002) also developed a framework for analyzing speakers role inhabitance in narratives of personal experience, and identified three roles—interlocutor, character, and author arising in the course of the narration. While Koven provided linguistic instantiations of each speaker’s role, his data mainly.

數據

相關文件

Work tasks include editing, drafting, and retouching professional documents in accordance with APEC format requirements, as well as editing speech

that study in the past, sum up, interconnected system produce, influence the intersection of industrial area and future testing amount of ' economic and regional de

• When a system undergoes any chemical or physical change, the accompanying change in internal energy, ΔE, is the sum of the heat added to or liberated from the system, q, and the

- Through exploring current events and social topics in project work and writing newspaper commentary at junior secondary level, students are provided with the

In 2006, most School Heads perceived that the NET’s role as primarily to collaborate with the local English teachers, act as an English language resource for students,

Learning Strategies in Foreign and Second Language Classrooms. Teaching and Learning a Second Language: A Review of

[7] C-K Lin, and L-S Lee, “Improved spontaneous Mandarin speech recognition by disfluency interruption point (IP) detection using prosodic features,” in Proc. “ Speech

從視覺藝術學習發展出來的相關 技能與能力,可以應用於日常生 活與工作上 (藝術為表現世界的知