聲譽對公司理財之影響

全文

(2) Acknowledgements It’ s time to end my dissertation.. Many thanks should I express to many good. persons who are always by my side.. I am most grateful to my dedicated supervisor, Dr. Victor W. Liu for his helpful guidance and assistance on my research.. He has provided me many constructive. suggestions and criticisms with his profound knowledge in finance and solid research experience.. His efforts of helping me complete this dissertation are highly. appreciated.. I am also indebted to Dr. Anlin Chen for valuable discussions on my. dissertation.. This paper owes much to the thoughtful comments from Dr. Roger, C.. Y. Chen (dissertation chair) and committee members: Dr. David, So-De Shyu, Dr. Chun-An Li, and Dr. Jen-Jsung Huang.. I would like to thank all the nice persons, good friends and colleagues, who have ever encouraged me.. Also, I wish to express many thanks to all of my family. members, my mother, brothers, and sisters, etc. for their considerate support.. A late gratitude is given to my Father in the heaven, in memory of him with my deepest regret.. i.

(3) Abstract For the past half a century, there has been progressive development in corporate finance theories, and among these, corporate financial decisions have been attracting the attention of outsiders.. As the outsiders’learning process of the firm’ s private. information determines the firm’ s value, managers who are concerned with outsiders’ perceptions of their firms try to enhance their firms’short-term reputation through their financial decisions.. However, up to this date, few reputation models have been. applied to predict these financial decisions.. Three corporate finance issues are involved to identify the reputation effects on corporate finance: (1) convertible bond call policies, (2) IPO decisions and activities, and (3) corporate financing policies.. As for the first issue, this study constructs a. two-period reputation model of a convertible bond call policy.. This model concludes. that in equilibrium, a firm with bad management quality and a bad reputation chooses to call, while a firm with good management quality or of a good reputation builds up it reputation by not calling the convertible bonds.. This is consistent with the. signaling theory proposed by Harris and Raviv (1985).. However, the reputation. model here identifies the call policy as a reputation-building mechanism rather than being only a signaling role, and suggests that the reputation rents resolve the discrepancies of the stock’ s post-call price performance.. As for the IPO decisions and activities, this study performs another reputation model to analyze a f i r m’ sr e put a t i one f f e c t sonI PO a ctivities, especially on the decision to go public.. The results yield that a f i r m’ sr e put a t i ondoe sa f f e c tits. decision to go public.. By listing equities publicly, firms with good management. quality and a solid past would anticipate enhancing their reputations, and those with a poor past would anticipate building up good names.. Furthermore, good reputation. firms with bad management quality would anticipate maintaining their reputations by going public.. On the other hand, it is found that good firms over-invest in building. up their reputations and bad firms take advantage of their reputations to go public. Both result in firms’over-going public and IPO mispricing.. This constitutes an. alternative interpretation on IPOs’l ong -run underperformance and the sharp decline ii.

(4) of the survival rate.. As for the corporate financing policies, the other reputation model is constructed by taking both determinants, the costs of financial distress as well as the firm’ s reputation into consideration.. The results show that good management quality firms. with good reputations enjoy their financial flexibility between debt and equity.. Bad. management quality firms take advantage of their good names to issue equities, which leads to over investment.. Good management firms lose their financial accesses due. to bad reputations, which lead to under investment.. Reputations would screen the. bad management quality firms with bad reputations off the market.. This dissertation concludes that reputations indeed affect the three selected corporate financial decisions and suggests further plow on more corporate finance issues.. Key words: reputation, corporate finance, convertible bond call, going-public decision, IPO mispricing, IPO long-run underperformance, capital structure, corporate financing policies. iii.

(5) 摘. 要. 公司理財的理論在過去半世紀裡持續地發展。其中,公司的財務決策吸引許 多外部投資人的關注。當公司的價值決定於外部投資人對公司經營品質的認知, 且公司經理人亦在乎外部投資人對公司的看法時,該經理人作任何財務決策,將 試圖強化其公司的聲譽,形成了聲譽影響公司價值的推論。然而,迄今聲譽模型 仍鮮少應用於公司的財務決策。. 本文將聲譽模型應用於三項公司理財之決策,以界定聲譽對公司理財之影 響:(1)可轉換公司債之贖回政策,(2)初次公開上市之決策與(3)企業融資政策。 首先建構兩期聲譽模型,應用於第一項議題:聲譽對可轉換公司債贖回政策之影 響,並獲致下列之結論:經營品質不佳的公司,會選擇贖回可轉換公司債;而經 營品質佳的公司,則藉由不贖回可轉換公司債建立其聲譽。本文之結論與 Harris 和 Raviv 在 1985 年的論文結果一致,然而,聲譽模型強調除發放信號的效果外, 不贖回可轉債可視為公司建立聲譽與信任的機制。. 在初次公開上市的決策議題中,本文亦建構另一聲譽模型,以分析公司聲譽 對公司初次公開上市決策之影響。其結果顯示公司聲譽確實影響上市與否之決 策。經營品質佳且擁有好聲譽的公司,期盼透過掛牌上市強化其聲譽;經營品質 佳但過去聲譽不佳的公司,期盼透過上市建立其聲譽。經營品質不佳但過去擁有 好聲譽的公司,期盼藉由上市維持其聲譽。然而,研究中亦發現經營品質佳的公 司有過度投資於聲譽的現象,而經營品質不佳的公司則藉其盛名上市。這些現象 導致了公司的過度上市及 IPO 的定價偏誤,也解釋了初次公開上市公司長期股價 表現不佳及存活率大幅下降的原因。. 第三個議題為企業融資政策,本文考量財務危機風險與公司聲譽等兩大因 素,建構一個聲譽模型。其結果顯示經營體質佳且擁有好聲譽的公司,可享有負 債或業主權益融資上之彈性。經營品質不佳但擁有好聲譽的公司,亦可藉其盛名 取得權益資金。但經營品質佳的公司,一旦聲譽不佳,則可能喪失融資管道而錯 失投資良機。經營品質與聲譽均不佳的公司,將在資金市場上被淘汰。 iv.

(6) 本文發現聲譽確實影響上述三項公司理財之決策,並建議在後續研究中進一 步探討聲譽對其他公司財務決策之影響。. 關鍵字:聲譽、公司理財、可轉換公司債贖回政策、初次公開上市、IPO 定價偏 誤、IPO 長期績效不佳、資本結構、企業融資策略. v.

(7) Contents Pages 1. Introduction. 1. 2. Literature Review 2.1 Reputation. 5. 2.2 Convertible Bond Call Policies. 9. 2.3 IPO. 10. 2.4 Corporate Financing Policies. 12. 3. Reputation Effects on Convertible Bond Call Policies 3.1 The Model. 17. 3.2 Equilibria of the Convertible Bond Calling Game. 23. 3.3 Main Reputation Effects and Empirical Evidence. 28. 3.4 Conclusion of Chapter 3. 31. 4. Reputation Effects on IPO Activities 4.1 The Model. 32. 4.2 Equilibria of the Going-Public Decision. 36. 4.3 Main Reputation Effects and Empirical Evidence. 41. 4.4 Over-Going Public, IPO Mispricing, and Long-Run. 43. Underperformance 4.5 Conclusion of Chapter 4. 47. 5. Reputation Effects on Corporate Financing Policies 5.1 The Model. 49. 5.2 Equilibria of the Corporate Financing Policies. 54. 5.3 Main Reputation Effects and Empirical Evidence. 57. 5.4 Conclusion of Chapter 5. 60. 6. Conclusion 6.1 Contribution to the Literature. 62. 6.2 Extensions. 65. Reference. 67. vi.

(8) Figures Figure 1.1 Diagram of the research structure. 4. Figure 3.1 Time line of the call-conversion game. 17. Figure 3.2 The call-conversion game. 19. Figure 4.1 Time line of the IPO model. 33. Figure 5.1 Time line of the Corporate Financing Model. 49. Tables Table 3.1 Notation of the Calling-Conversion Model. 22. Table 4.1 Notation of the IPO Model. 36. Table 4.2 Probability Matrix of Going Public as a Function. 40. of a Firm’ s Quality and Its Reputation Table 5.1 Notation of the Corporate Financing Model. 53. Table 5.2 Decision Matrix of Financing and Investing. 57. vii.

(9) 1. Introduction Since the 1980s, the introduction of the agency problem at various levels of the corporate structure has dominated the literature of corporate finance.. The. mainstream of the agency theory focuses on the incentive of the firm’ s insiders, who play the role of the informed party in the principal-agent relationship. asymmetries plague this agency relationship.. Information. Insiders may have private information. about the firm’ s technology/environment or the realized returns, but outsiders cannot observe the insiders’decision processes and the efforts they exert to make the firm profitable.. Financial contracting thus designs the incentive scheme for insiders that. best aligns the interests of the two parties.. Due to asymmetric information, outsiders try their best to dig into the private information of the firms.. The information originates from observing the firm’ s past. performance, the investment and financing decisions, and analysts’reports, or experiencing the firm’ s products, etc.. Once the new information arrives, the. outsiders update their beliefs about the firm’ s future perspective.. Knowing the. outsiders’learning process, the insiders also try their best to signal the market that they are good.. The learning process by the outsiders is dynamic and gradually forms. the firm’ s reputation.. This makes the firm’ s reputation a key determinant to the. firm’ s value so that the firm exerts great efforts to build up a reputation, maintain its good name, and enhance it.. The economics of reputation has been widely applied to predict a variety of strategic decisions.. Reputation-building models, conducted by Kreps and Wilson. (1982) and Milgrom and Roberts (1982), sketch the incumbents’strategies to deter entry by establishing a reputation for being tough.. Shapiro (1983) formulated a. reputation model to derive the equilibrium price-quality schedule for markets where high quality products are sold at a premium above their cost to compensate the producers for their investment in reputation.. Tadelis (1999) looked at the firm as a. bearer of reputation and proved that a firm’ s name (reputation) is valuable and tradeable.. Cabral (2000) considered an adverse selection model of a firm’ s decision. to stretch its reputation and suggested that for a given level of past performance (reputation), firms use the same name as their base product (reputation stretching) to launch a new product. 1.

(10) Corporate finance issues have been developing for the past half century. Among these, the operations of the financial tools conceal corporate private information most.. Decisions regarding the operations of the financial tools attract. the outsiders’attentions.. As the outsiders’learning process of the firm’ s private. information determines the firm’ s value, managers who are concerned with outsiders’ perceptions of their firms try to enhance their firm’ s short-term reputation through their financial decisions.. But, up until the present, few reputation models have been. applied to predict these financial decisions.. In this dissertation, the author tries the first shot on discovering how reputation affects corporate financial decisions.. Some controversies still exist among the. literature of the informational problems concealed in the financial tools, such as the timing and the information of the convertible bond call, the going public decision, IPO pricing, IPO long-run performance and the firm’ s financing source, etc. Questions are often asked by the market participants, such as: calls really good or bad?. Are convertible bond. Which party in the financial market calls convertible bonds?. The signaling theory proposed by Harris and Raviv (1985) suggests that a decision to call is perceived by the market as a signal of unfavorable prospects.. Contrary to the. signaling theory, the empirical study by Ederington and Goh (2001) found that insiders buy more stocks before and after the conversion-forcing convertible bond calls.. Market professionals (analysts) also tend to raise their earnings forecasts. following a call.. Under such a scenario, the decision to call is not perceived as bad. news by the market as well as by the managers of calling firms.. In Chapter 3 of my. dissertation, a new attempt is made to reconcile the controversies by analyzing the reputation effects on the convertible bond call policies.. Some other questions are also raised by the current and the potential shareholders, such as:. What kind of firm chooses to go public?. Why do firm owners share their. golden pot with the public since the firm makes money for their own selves? reputation affect firms’decisions to go public?. Does. Most studies in the literature. conclude that the average IPO is undervalued at the offer price (e.g. Rock, 1986; Grinblatt and Hwang, 1989; Allen and Faulhaber, 1989; and Welch, 1989); but the study by Purnanandam and Swaminathan’ s (2004) finds that IPO is overpriced. the reasons to IPO long-run underperformance are not universal. 2. Also,. How do the.

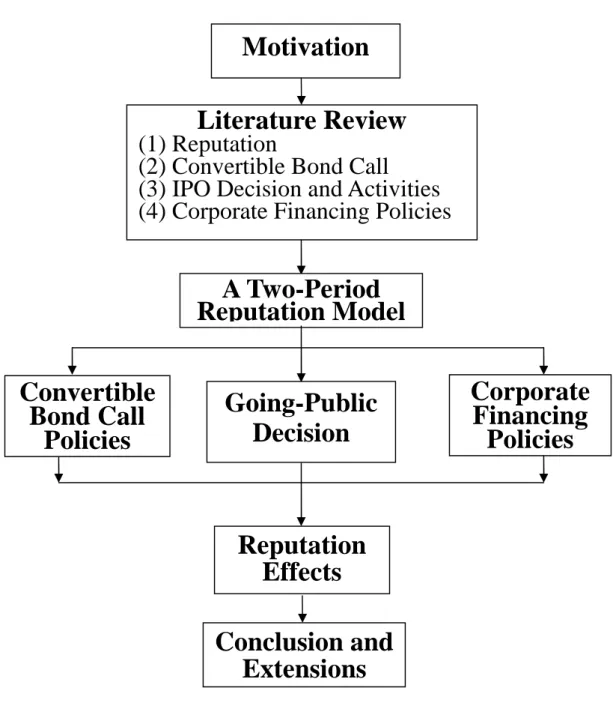

(11) reputation effects work on the IPO activities?. In Chapter 4, these questions will be. answered from the perspective of the firm’ s reputation.. Literature of capital structure leaves a puzzle on when and why firms issue common equities.. The pioneering pecking order theory (Majuluf and Myers, Myers,. 1994) proposed that firms prefer internal funds to finance new projects, then debt and then equity as the last resort. issue equities each year.. But Fama and French (2005) found that most firms. Further, Kay and Titman (2007) also showed that the firms’. histories induce firms to pursue equity financing. corporate financing choices?. How does reputation affect. In Chapter 5, a reputation model is applied to shed. some light on the capital structure puzzle.. Three reputation models are developed to analyze the reputation effects on convertible bond call policies, going public decisions and corporate financing policies. The research structure is constructed as Fig. 1.1. organized as follows.. The rest of this dissertation is. Chapter 2 reviews the literature.. Chapter 3 develops a. reputation model to analyze the reputation effects on convertible bond call policies. Chapter 4 focuses on IPO issues by constructing a reputation model and analyzes the reputation effects on IPO activities. corporate financing policies.. Chapter 5 proposes the reputation effects on. Chapter 6 concludes this dissertation.. 3.

(12) Motivation Literature Review (1) Reputation (2) Convertible Bond Call (3) IPO Decision and Activities (4) Corporate Financing Policies. A Two-Period Reputation Model Convertible Bond Call Policies. Going-Public Decision. Reputation Effects Conclusion and Extensions Figure 1.1 Diagram of Research Diagram. 4. Corporate Financing Policies.

(13) 2. Literature Review 2.1 Reputation The word, reputation, in the Webster dictionary represents for the overall quality, characteristic, or ability as recognized or judged by people in general. for a place in public esteem or regard, e.g. a good name.. It also stands. By definition, reputation is. formed by the counter party throughout the everyday interactions.. Firms are said to. have reputations for selling good quality products, labor for working hard, auditors for being honest, and governments for being rigorous on inflation, and so on. statements regarding reputation share two features.. These. They establish links between. past behavior and expectations of future behavior — the buyers expect good quality products, because good quality products have been provided in the past.. In addition,. they involve behavior that one might not expect in a one-shot interaction — the buyer wonders about the quality of a watch sold in a small stand of the night market, but is more confident of a deal on a watch from a boutique with whom the customer has regularly done business.. Both suggest that reputations are like assets and those who. would like to build up reputations are willing to incur short-run costs for the long-run planning.. There are two approaches to reputations in the repeated games literature (Mailath and Samuelson, 2006).. First, an equilibrium of the repeated game is selected,. involving actions along the equilibrium path that are not Nash equilibria of the stage game.. Players who always choose the equilibrium actions are regarded as. maintaining a reputation for doing so, while enduring punishment if deviating from the equilibrium.. A deviation is interpreted as the loss of one’ s reputation.. The. model proposed by Milgrom and Roberts (1982) is a representative literature of reputation, in which predation is practiced by the incumbent firm not because it is directly profitable to eliminate the particular rival, but rather because it might deter future potential entrants. a predator.. By practicing predation the firm established a reputation as. This reputation leads potential entrants to anticipate that the incumbent. firm will behave similarly if they should enter, and thus entry appears less attractive to them.. The second one is known as the adverse selection approach and possibly signaling as well to reputations.. It begins with the assumption that there are hidden 5.

(14) information and hidden actions.. Different types of players are expected to play in. different ways.. Each player’ s reputation is defined as her opponents’current beliefs. about her type.. The incomplete information is a device that introduces an intrinsic. connection between past behavior and expectations of future behavior.. This. approach is based on Bayesian updating process — the uninformed party updates her beliefs about the type of the informed party and forms the reputation of the informed party.. Though the reputation model is similar with the signaling game, there are still some distinctions between them.. Signaling games are the simplest kind of games in. which the issues of updating and perception both arise.. In these games, there are two. players: player 1 is the sender, who sends a signal and player 2 is the receiver. Player 1 has private information about his type, t and makes decision d1 in D1 . Player 2, whose type is common knowledge for simplicity, observes d1 and chooses. d 2 in D2 . Before the game begins, it is common knowledge that player 2 has prior beliefs p about player 1’ s type.. Player 1’ s action can depend on his type.. Player 2,. who observes player 1’ s move before choosing her own action, should update her beliefs about t and base her choice of d 2 on the posterior distribution (Fudenberg and Tirole, 1992).. The key distinction between the reputation model and the. signaling game is that, for a reputation model, player 2 forms her beliefs about player 1’ s type by observing player 1’ s past performance, 1 as well as his action, d1 . Thus, in a reputation model, player 1’ s action now depends on his type (private information) as well as his past performance (or his history).. Most studies in the reputation literature in economic theory focus on repeated games with complete or incomplete information (e.g. Selten, 1978; Kreps and Wilson, 1982; and Milgrom and Roberts, 1982).. The focus is mostly on whether reputational. concerns lead firms to act cooperatively and what conditions support such equilibria. However, the asset-like aspect of a firm’ s reputation is mostly ignored.. A firm’ s. reputation is regarded as the firm’ s intangible assets with value imbedded in it.. The. firm’ s name, as a label that summarizes the physical attributes, past behavior, the quality of the firm’ s goods/ services, and other characteristics of the firm, carries the reputation of the firm (Tadelis, 1999).. It follows that recent literature of reputation 6.

(15) focuses on the value of a firm’ s reputation as well as the market for the bearer of reputation, a firm’ s name.. Shapiro (1983) formulated a reputation model to derive the equilibrium price-quality schedule for markets where the customers could not observe product quality prior to purchase.. In such markets, there is an incentive for the producers to. reduce quality and take short-term gains before the customers could catch on.. In. order to avoid such quality cutting, the price-quality schedule involves high quality products selling at a premium above their cost.. This premium compensates the. producers for their investment in reputation.. Tadelis (1999) developed a model in which a firm’ s only asset is its name summarizing its reputation and studied the forces that cause names to be valuable and tradeable assets.. In Tadelis’model the central assumption is that transactions carried. out in the market for names are hidden from potential clients of these firms - that is, the potential clients cannot observe the shift of the name’ s ownership.. Due to the. natural way in which beliefs are updated in the dynamic equilibria, poor past performance will cause a firm’ s name to lose value.. Once the value falls enough, it. is worthwhile to discontinue the firm’ s name and start with a “ clean”record.. Thus,. the adverse selection in Tadelis’formulation plays a crucial role in understanding a firm’ s reputation.. Rob and Fishman (2005) constructed a model where reputation spreads in the market through word of mouth, or referrals: consumers tell other consumers about their experience of some products, causing some firms to grow and other firms to decline.. As a consequence, a firm starts as a small one, grows gradually, and. changes its investment as its reputation is established.. These interrelated processes. of firm growth and reputation formation predict that the longer its tenure as a high-quality producer, the more a firm invests in quality.. Fisher and Heinkel (2007) introduced a self-insurance role for reputation.. In. their model, honesty is endogenous for all types, and the emergence of truth-telling is more cynical.. Corporate insiders such as managers and analysts provide earnings. forecasts to investors accurately when their current circumstances are good and 7.

(16) reputation-building is affordable; those lie when their current circumstances are poor and they require income.. Cabral (2000) then considered an adverse selection model of a firm’ s decision to stretch its reputation.. In the model each firm is characterized by an exogenously. given quality level, which is the firm’ s private information and is applied to any product it sold.. The customers observe the performance of the firm’ s products,. which is an indicator to the firm’ s quality level.. Reputation here is the consumers’. posterior beliefs on the firm’ s quality level given the firm’ s past performance. Looking at the firm’ s decision as an informational problem, Cabral suggested that for a given level of past performance (reputation), firms use the same name as their base product (reputation stretching) to launch a new product. proposed in the decision to stretch a reputation.. Three effects were. First, a firm’ s reputation from its. base product influences the consumers’willingness to pay for a new product sold under the same name, which is regarded as the direct reputation effect.. Second, the. performance of the new product, if sold under the same name, influences the consumers’willingness to pay for future sales of the base product, which is regarded as the feedback reputation effect.. Finally, insofar as the decision to stretch is related. to the firm’ s quality, the simple fact that a firm uses the same name to launch a second product influences the consumers’willingness to pay for the new product, which is regarded as the signaling effect.. The concept of reputation also applies to the aspects of financial management. Diamond (1989) analyzed the joint influence of adverse selection and moral hazard on the ability of reputation to eliminate the conflict of interest between borrowers and lenders about the choice of risk in investment decisions.. The result shows that. incentive problems could be most severe for borrowers with very short track records and become less severe for borrowers who manage to acquire a “ good reputation” . Martinelli (1997) presented a reputation-building model by stating that new firms need to be patient to build and accumulate a good reputation in order to maintain access to the credit market.. Here, reputation is regarded as a tool of screening.. Further in this dissertation, the author would like to develop reputation models on the decisions of corporate finance.. Extended from the concept that the firm’ s 8.

(17) reputation is the firm’ s valuable intangible asset, Cabral’ s reputation model (2000) is applied to determine a firm’ s convertible bond call policies, going public decision, and corporate financing policies.. Three reputation models are constructed to. demonstrate the reputation effects on the above three corporate finance issues respectively.. Two players are involved in the reputation model: the firms’decision. makers and the outsiders who participate in accessing information and observing actions of the firms.. The information sets consist of two dimensions: the histories as. well as the management quality of the firm.. The equilibrium concept used is that of. a Bayesian equilibrium, where there is a strategy profile and posterior beliefs such that the selected strategy maximizes the f i r m’ se xpe c t e dva l ue and the posterior beliefs s a t i s f i e sBa y e ’ sr ul e . Due to the characteristics of the underlying assets involved in the corporate finance issues, the author constructs a two-period model to identify the short-run reputation effects on these corporate decisions.1. 2.2 The Convertible Bond Call Policies The optimal convertible bond call policy selected by management should be one that maximizes the firm’ s market value.. Two major perspectives on this subject have. generated a great amount of literature.. One focuses on the timing to call the. convertible bond (e.g. Ingersoll, 1977a,b; Brennan and Schwartz, 1977; and Asquith, 1995, etc.) or the economic factors that affect the timing to call (Sarkar, 2003).. The. other focuses on the call decisions (to call or not to call), the information conveyed by the call, and the stock’ s post-call performance (e.g. Harris and Raviv, 1985; Ofer and Natarajan, 1987; Ederington and Goh, 2001; and Datta et al., 2003, etc.).. Due to the. inconsistency between the theoretical prediction and some empirical evidences, the second perspective is still in dispute.. Two contraries exist regarding the call decisions: the call and the stock’ s post-call performance.. the information conveyed by. First, the signaling theory proposed. by Harris and Raviv (1985) suggests that a decision to call is perceived by the market as a signal of unfavorable prospects.. Thus, the manager calls after receiving a “ bad”. message and never calls after receiving a “ good”message. 1. This was then supported. This short-run reputation model may be extended to find a long-run effect by applying an overlapping generation model. To identify the short-run v.s. long-run reputation effects on other corporate finance issues, the author attempts to extend the analysis of long-run effect to the future research. 9.

(18) by Ofer and Natarajan (1987) and Datta et al. (2003), who stated that there is a short-run negative impact on the firm’ s earnings and a long-run underperformance on the price of common stocks after the calls, respectively.. The other argument is that the decision to call is not perceived as bad news by the market, as supported by Ederington and Goh (2001).. Contrary to the signaling. theory, they found that insiders buy more stocks before and after the conversion-forcing convertible bond calls.. Market professionals (analysts) also tend. to raise their earnings forecasts following a call.. Under such a scenario, the decision. to call is not perceived as bad news by the market as well as by the managers of calling firms. Discrepancies thus far do exist over a stock’ s post-call price performance and the information the call conveys.. Are convertible bond calls really good or bad? market calls convertible bonds?. Which party in the financial. Datta et al. (2003) believed that based on Daniel et. al. (1998), the market response around conversion-forcing bond calls is incomplete. Therefore, a short post-call time horizon is insufficient to draw reliable conclusions regarding the information conveyed by conversion-forcing calls.. From the. perspective of a firm’ s reputation, this dissertation will provide an alternative interpretation to a firm’ s convertible bond call policies.. 2.3 IPO Many established studies in the literature have been generated on initial public offerings, because IPO activities such as the going-public decision, process, and performance, etc. are all important not only from the firm’ s viewpoint, but also from that of the market.. Some empirical studies focusing on some interesting IPO. phenomena include the first-day returns anomaly, underpricing, t he “ hot-issue” market, and the long-run underperformance, etc. (Loughran et al., 1994; Teoh et al., 1998; Loughran and Ritter, 2001, 2002; Ritter and Welch, 2002), while a few take the issuer’ s reputation into consideration.. 2.3.1 The Decision to Go Public What kind of firm chooses to go public?. Why do firm owners share their. golden pot with the public since the firm makes money for their own selves? 10. Does.

(19) reputation affect firms’decisions to go public? on the IPO activities? shareholders.. How does the reputation effect work. Such questions are widely asked by potential and the current. Theoretic analyses on the decisions to go public focus on how. information cost affects a firm’ s decision to go public (e.g. Chemmanur and Fulghieri, 1999).. Chammanur and Fulghieri (1999) analyzed the costs and benefits of two. financing alternatives, going public v.s. remaining private.. Holding other things to. be constant, the key determinant for a firm to go public is the outsiders’evaluation cost of a firm.. Low evaluation cost induces a firm to go public and high evaluation. cost makes a firm go for private equity financing.. However, the firm’ s reputation,. the intrinsic motive for a firm to go public, is supported by some investigative and empirical researches only.. The quality and reputation of a firm’ s top management can have a certifying effect on firm value (Chemmanur and Paeglis, 2005). Going public increases the publicity, reputation, and value of the going public firm (Maksimovic and Pichler, 2001).. Draho (2004) stated that an IPO is valuable, because it directly improves the. reputation.. An investigative research by Brau and Fawcett (2006) also found that. high-tech firms view an IPO more as a strategic reputation-enhancing move than as a financing decision.. Thus, for younger firms with few records to be tracked, building. up the firm’ s reputation and attracting analysts’attention motivate them to go public.. 2.3.2 IPO Mispricing and Long-Run Underperformance Rock (1986) assumed that some investors are perfectly informed about the value of the IPO while the rest is uninformed; underpricing thus becomes compensation to uninformed investors for being allocated a disproportionately large fraction of overpriced IPOs.. Other studies in the literature related to IPO. underpricing take the first-day market price as the “ fair value”of the issuing firm and conclude that the average IPO is undervalued at the offer price (e.g. Grinblatt and Hwang, 1989; Allen and Faulhaber, 1989; and Welch, 1989).. An example like. Welch’ s model (1989) stated that high-quality firms underprice at their IPOs in order to obtain a higher price at a seasoned offering, but a high imitation cost might induce low-quality firms to reveal their quality voluntarily.. Empirical research by Loughran and Ritter (2004) found that IPO underpricing 11.

(20) changed over time.. They concluded that in 1980, it is conceivable that the winner’ s. curse problem and dynamic information acquisition were the main explanations for underpricing.. During the internet bubble, the main reasons are analyst coverage and. side payments to CEOs and venture capitalists.. Contrary to the finding of IPO underpricing, Purnanandam and Swaminathan’ s study (2004) showed IPO overpricing.. They found that in a sample of more than. 2,000 IPOs from 1980 to 1997, the median IPO was significantly overvalued at the offer price relative to valuations based on industry peer price multiples.. Their results. showed that IPOs are overvalued at the offer price, tended to run up in the after market, and reverted to fair value in the long run.. Daniel, Hirshleifer, and. Subrahmanyam (1998) also proved that investors’overconfidence about private information causes initial overvaluation, and underreaction to subsequent public news leads to continuing overvaluation, which is ultimately followed by long-run reversals. This also provides an alternative interpretation to the phenomenon of IPO long-run underperformance.. Schultz (2003) offered an explanation for this phenomenon that more IPOs follow successful IPOs.. When the followers carry a large fraction of the sample and. also underperform in the market, then the average returns of all the IPOs tend to be low.. Shefrin (2002) summarized his study from the viewpoint of behavioral finance.. He suggested that firms are more likely to issue new shares when they face a window of opportunity and that their stocks are overvalued. expect a continuation and bet on trends.. The investors at the same time. They overweight the recent past when. making long-term projections and thus suffer from long-term underperformance. Teoh et al. (1998) attributed the long-run underperformance to the deliberate manipulation of the IPO firm’ s reputation by adopting discretionary accounting accrual adjustments that raise reported earnings relative to actual cash flows before IPO.. 2.4 Corporate Financing Policies Co r por a t ef i na nc i ngpol i c i e sa f f e c tf i r m’ sc os tofc a pi t a la swe l la si t sf i n a nc i a l structure.. As the financial risk of the traded securities increases along with the. innovation of various financial tools, the decision of corporate financing policies 12.

(21) plays a more important role in the rapidly changing environment.. Myers (2001). suggests that there is no universal theory of the debt-equity choice and no reason to expect one.. However, there are several conditional theories.. Traditional capital structure theory began i nModi g l i a nia ndMi l l e r ’ s( he r e a f t e r MM) study in 1958, which proved t ha tunde rt hepe r f e c tma r ke thy pot he s i s ,af i r m’ s value is irrelevant to its capital structure.. That is, under the zero-tax environment, it. does not matter how a firm finances its operation, hence there is no net benefit to using financial leverage.. The corrected MM theory in 1963 proposed that when. taking corporate taxes into consideration, the interest tax shield encouraged corporations to use debt.. Miller (1977) extended the analysis to personal taxes.. Compa r i ngi nve s t or s ’t a xa t i onf r o mi nt e r e s ti nc o meofde bta nddi vi dend income of stocks, Miller found that common stock returns are taxed at significantly lower effective rates than debt returns and thus favors the use of equity financing.. Though. it is difficult to distinguish the net effect, it is widely believed that interest deductibility has the stronger effect.. Fol l owi ngMM’ spa pe r s ,t hes t a t i ct r a de of f. hypothesis emerges, in which firms trade off the benefits of debt financing against the costs of financial distress and pursue an optimal debt ratio.. Myers (1977) concluded. that risky firms should borrow less and safe firms should be able to borrow more before the expected costs of financial distress offset the tax advantages of borrowing.. For most of the traditional theories, they conclude that a firm can pick an optimal mix of debt and equity by focusing on the tradeoffs between the tax benefits of debt and the potential costs of financial distress.. However, according to Myers (1996),. debt benefits begin to be eroded because the firm runs out of income to be shielded from taxes.. Furthermore, Myers (2001) found that the tradeoff theory is in. immediate trouble on the tax front, because it seems to rule out conservative debt ratios by taxpaying firms.. But, the financial distress cost exists, which according to Myers (2001) refers to the costs of bankruptcy or reorganization, and also to the agency costs that arise when the firm’ s creditworthiness is in doubt.. Barclay and Smith (2005) suggested that the. cost of financial distress is an indirect cost associated with the bankruptcy process. For most companies, the most important indirect cost is the loss in value that results 13.

(22) from cutbacks in promising investment when the firm gets into financial trouble. When a company files for bankruptcy, the bankruptcy judge effectively assumes control of corporate investment policy.. I might happen that judges fail to maximize. value. Even in conditions less extreme than bankruptcy, highly leveraged companies are more likely than their low-debt counterparts to pass up valuable investment opportunities, especially when faced with the prospect of default.. In such cases,. corporate managers cannot help to postpone major capital projects and to cut the corporate expenses.. A further study by Harris and Raviv (1991) offered an overall review of capital structure theories and identified four categories of determinants of capital structure. First, capital structure is determined by agency costs, i.e., costs due to conflicts of interest.. The second approach to explain capital structure is based on the existence. of asymmetric information.. The third approach focuses on the relationship between. a firm’ s capital structure and its strategy when competing in the product market as well as the characteristics of its product or inputs.. The fourth theory is driven by. corporate control considerations.. To my best knowledge, little literature takes reputation into consideration.. In. Chapter 5, I am going to identify the reputation effects on corporate financing policies. Since this chapter is more related with the second category mentioned by Harris and Raviv (1991), literature review here will focus on the approach of asymmetric information.. Majluf and Myers (1984) proposed that firms prefer internal funds to finance new projects.. If external finance is required, firms start with debt, then hybrid. securities such as convertible bonds and then equity as a last resort.. The main. reasoning behind the pecking order theory is that, if investors are less informed than current firm i ns i de r sa boutt heva l ueoft hef i r m’ sa s s e t s ,e qui t ywi l lbemi s pr i c e dby the market.. If firms finance new projects by issuing equity, underpricing may. benefits new investors more than the NPV of the new project, resulting in a net loss to existing shareholders. positive.. In this case the project will be rejected even if its NPV is. This underinvestment can be avoided if the firm can finance the new. project through a non-sensitive security. 14. Therefore, internal funds and debt are.

(23) preferred to equity by firms. theory of financing.. Myers (1984) referred to this as a “ pecking order”. By taking both asymmetric information and costs of financial. distress into consideration, Myers (1984) concluded that firms do not want to run the risk of falling into the dilemma of either passing by positive NPV projects or issuing stocks at an underpriced value.. Thus, common stocks or risky securities are not. welcomed in corporate financing decisions.. However, a puzzle of when and why firms issue common equity was left. Myers (1984) also commented that a firm may choose to reduce the costs of underinvestment as well as financial distress by issuing stocks just to move the firm down the pecking order.. The signaling theory (Ross, 1977; Heinkel, 1982; Stien,. 1992) states that a firm with favorable prospects will raise new capital through debt financing, while a firm with unfavorable prospects will go through equity financing. Fi r m’ sf i na nc i ngde c i s i ons i g na l sf i r m’ spr os pe c tt hema na g e me ntpe r c e i ve s .. Literature relating to the decision and the timing of securities issuance also tries to clarify the puzzle above.. Studies by Masulis and Korwar (1986), Asquith and. Mullins (1986) showed that firms tend to issue equity following an increase in stock prices, implying that firms that perform well subsequently reduce their leverage.. In. addition, Stulz (1990), Hart and Moore (1995) and Zwiebel (1996) proposed that firms should use relatively more debt to finance assets in place and relatively more equity to finance growth opportunities.. As a result, firms may choose to issue equity. rather than debt in response to an increase in their value, if the change in value is generated by an increase in the perceived value of their growth opportunities.. Fama and French (2005) found that most firms issue or retire equity each year, which is contradictory to the pecking order theory.. The market timing theory. proposed by Baker and Wugler (2002) suggested firms are more likely to issue equity when their market values are high, relative to book and past market values.. As a. consequence, current capital structure is strongly related to historical market values. They concluded that low leverage firms are those that raise funds when their market valuations are high, while high leverage firms are those that raise funds when their market valuations are low.. 15.

(24) Hovakimian, Opler and Titman (2001) suggested t ha taf i r m’ shi s t or yma ypl a y an important role in determining its capital structure.. Kayhan and Titman (2007). confirmed that history does in fact have a major influence on capital structure.. Their. empirical results showed that the cumulative stock return as well as the cumulative profitability has negative impact on the change in leverage, which implies that a firm with a good past will decrease its leverage ratio.. 16.

(25) 3. Reputation Effects on Convertible Bond Call Policies Are convertible bond calls really good or bad? market calls convertible bonds? convertible bond?. Which party in the financial. Does reputation affect a firm’ s decision to call its. Such issues are still in dispute.. Datta et al. (2003) believed that. based on Daniel et al. (1998), the market response around conversion-forcing bond calls is incomplete.. Therefore, a short post-call time horizon is insufficient to draw. reliable conclusions regarding the information conveyed by conversion-forcing calls. Except for the time horizon argument, an alternative insight from the reputation effects is proposed herein to reconcile the discrepancies of the information contents imbedded in the conversion-forcing calls.. 3.1 The Model 3.1.1 General Framework A reputation model is constructed to demonstrate a firm’ s convertible bond call policy when the firm’ s reputation is considered.. In this model the players include the. manager as well as the stockholders of the firm. private information.. The firm has both public and. The public information is in regards to the firm’ s past actions,. which are observable and formulated as a firm’ s reputation.. The private information,. regarded as the intrinsic management quality of the firm, determines the performance of the firm’ s new project.. The manager of the firm makes the call policy to. maximize the firm’ s value.. Given the firm’ s reputation as well as its call policy, the. stockholders update their beliefs associated with the firm’ s quality, which determine the firm’ s future value.. T=0. performance of 1st period observed. Firm established, as Type-G or Type-B. T=1. 1 , firm chooses. Success or failure realized.. the call policy, d {C , NC}. Convert or redeem CB if. Given. Investors update their beliefs. Firm issues CB and. of the firm being good after. executes a new. observing the firm’ s past and the. project.. calling decision.. Figure 3.1.. T= 2. Time line of the call-conversion game 17. not called..

(26) Unlike Harris and Raviv (1985), we apply a two-period model to address the convertible bond call policies.. Consider an economy with three dates, indexed by. T=0, 1, and 2 as shown in Figure 3.1.. At time 0, the firm adopts a new investment. project, which continues for two periods. of stocks outstanding.. The firm has initial wealth E and N shares. To generate funds needed for a new investment project, the. firm also issues D zero-coupon, default-free, callable convertible bonds, each with $1 par value.. At the end of the project, the bonds mature.. If the firm succeeds in the. project, then it will receive H at time 2, with a total firm value of E+H. investment decreases the firm’ s value to E+L (=E-H). 2. calculation, we assume that L<0<D<H and L=-H.. A failed. To simplify the notation and Thus, a default-free bond will. have E-H>D. Figure 3.2 shows the call-conversion game.. At time 1, when the project has. been executed for one period, the investors observe the initial performance of the project, either as successful, S, or as a failure, F, denoted as 1 {S , F } .. At this. 1 {S , F } time, the firm has the option to call the convertible bond.. A firm’ s. action, to call or not to call, is denoted as d {C , NC} .. The aim of this paper is to. discover the reputation effects on a conversion-forcing call, and thus there are three basic assumptions behind this model. convertible bonds.. First, there are no restrictions on the. Second, the bonds are called at a price of zero and the. bondholders will convert their bonds to stocks as long as the convertible bonds are called - that is, it focuses on the case of force conversion as Harris and Raviv (1985) did.. Third, if the bonds are called to convert, then the bonds will be converted to. N shares of common stocks. On the other side, if the firm chooses not to call, then the bondholders will not convert the bonds at time 1.3. At the end of the stage,. the project is realized and the bondholders will decide whether to convert their bonds. As usual, the bondholders choose to convert their convertible bonds when the project is successful.. If the project fails, then the bonds are not converted and the firm. redeems all at par.. 2. 3. The results remain robust for any. L H .. As in Harris and Raviv (1985), there is no reason for the bondholders to convert voluntarily since it. is worth waiting.. 18.

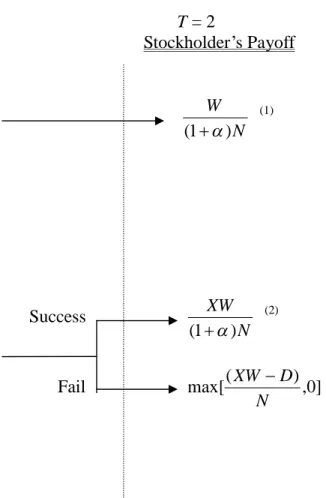

(27) T=0. T=1 Call Policy:. d. T=2 Stockholder’ s Payoff. Bondholders Conversion Decision. Call. W (1 ) N. Convert. (1). ( d C ). 1 {S , F }. Success Not call. XW (1 ) N. Not convert. ( d NC ). Fail. Figure 3.2. The call-conversion game (1) W is the total expected value of a calling firm. (2) XW is the total expected value of a non-calling firm.. 19. max[. (2). ( XW D) ,0 ] N.

(28) 3.1.2 Management Quality and Firm’ s Reputation As mentioned in the previous section, the project will continue for two periods and the outcomes will be realized at time 2. completed.. There is no payoff before the project is. As the project is being realized, the firm’ s value will increase or. decrease by H, depending on whether the project succeeds or fails.. The proceeds for. the new project depend on the management quality of the firm being either good (denoted as a type-G firm) or bad (denoted as a type-B firm). private information.. Management quality is. The prior probability of the firm being good is p.. The model further assumes that, with probability , a type-G firm will succeed in the project, whereas a type-B firm will succeed with probability 1 . P( S G ) P( F B) 1 P( F G ) P( S B) . Hence: (3.1). The managers of the firm know their probability , but the public know the distribution of only.. Thus, the firm’ s expected value equals:. v( p ) p [ ( E H ) (1 )( E H )] (1 p )[(1 )( E H ) ( E H )] E (2 p 1)(2 1) H. (3.2). As shown in Figure 3.1, the firm’ s performance within the first period is observable, which forms an inference as to the management’ s quality.. At the initial. stage, the stockholders observe the performance of the project and learn the initial quality of the firm.. A firm’ s performance within the first period is denoted as. 1 {S , F } . After learning the performance of the initial stage, the bondholders and the stockholders update their belief of the firm’ s type to a probability of. p1 P(G 1 )1 . We may refer to this posterior as the firm’ s current reputation. The current decisions a firm has to make are to call or not to call at time 1.. The. bondholders respond to the firm’ s call policy and the stockholders update their belief d of the firm being a good type to p P(G 1 , d )1 {S , F } and d {C , NC} . 1. As proposed by Wilson (1985), there are longer-term consequences due to the effect of the current decision on the future reputation.. Here, since the management’ s. quality is private information, the outsiders infer from the firm’ s current decisions as 20.

(29) to the firm’ s future performance.. Imagine that after the completion of the new project, success or failure will be realized.. At time 2, the stockholders further update the posterior to be. d p P(G 1 , d , 2 )1 {S , F } , d {C , NC} and 2 {S , F } . At the current 12 d stage, p is regarded as the outsider’ s anticipation of the firm’ s future reputation. 12. It is believed that a good management quality firm is more likely to have a successful historical performance and hence carry with it a successful name - that is, higher performance is “ good news”regarding a firm’ s quality (Milgrom, 1981), and so we assume that 1 / 2 .. Furthermore, for a firm with a successful history, the. stockholders are more likely to perceive it as a type-G firm. p Sd p Fd d {C , NC} .. Thus, we have. The notation of the calling-conversion model is shown as. Table 3.1. 3.1.3 The Expected Value of the Firm Assume that the firm’ s decision-makers are risk-neutral and the ma na g e me nt ’ s primary goal is to maximize stoc khol de r s ’we a l t h,and so the financial policies are to maximize the firm’ s value, including the convertible bond call decision. t probability of a firm to call its bonds equals g .. type and refers to a firm’ s reputation.. The. The subscript t refers to the firm’ s. The firm’ s expected value is a function of. the investors’beliefs associated with the firm’ s type after an understanding of the firm’ s action as well as its current and future reputation.. To simplify the calculation,. we further assume there is no discounting. If the firm calls its convertibles at time 1, then in the case of forcing conversion the expected value per share for a type-G firm to call will be: G 1. V. C v( p ) 1. . (1 ) N. (3.3). The expected value per share for a type-B firm to call will also be: B 1. V. C v( p ) 1. . (1 ) N. (3.4). 21.

(30) Table 3.1.. Notation of the Calling-Conversion Model. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------E. Firm’ s initial wealth. N. Firm’ s initial shares of stocks outstanding. D. Total amount of the convertible bonds. H. The amount a firm generates for a successful project. L. The amount a firm generates for a failed project. d. Firm’ s call policies. (C,NC). C: to call ; NC: not to call. . The proportion of the stocks converted from the bonds. t. Fi r m’ st y pede pe ndi ngont hequality of a firm’ s management (Good or. (G, B). Bad).. . Probability that a type-G firm will succeed.. . Firm’ s performance set as a signal of a firm’ s reputation, either as a. ( 1 , 2 ). success or failure, {S,F}.. P S G P F B .. 1 : Fi r m’ sperformance in the first period.. 2 : Fi r m’ sperformance in the second period. p d p. prior belief that the firm is type-G Posterior that the firm is type-G, given the f i r m’ scalling decision. andf d C , NC i r m’ s reputation. 1 , 2 , 1 {S , F }, 2 {S , F } . V. The expected value per share for a firm to call. NV. The expected value per share for a firm not to call. t g. Probability that a firm will call the CBs at time 1, given t G, B and S, F .. 22.

(31) From (3.3) and (3.4), we find that, in the case of forcing conversion, the stockholders suffer a dilution cost due to an addition of the converted shares to the original shares outstanding.. If the convertible bonds are not called at time 1, then the bondholders will update their belief to pNC .. The expected value per share for a type-G firm not to call is:. v( p NC1S ) (1 )[v( p NC1F ) D] NVG . (1 ) N N. (3.5). The expected value per share for a type-B firm not to call is: (1 ) v( p NC1S ) [v( p NC1F ) D] NVB . (1 ) N N. (3.6). From (3.5) and (3.6), the bondholders convert their convertible bonds voluntarily when the project succeeds at time 2.. In this case, the dilution cost still exists.. project fails, then the bondholders will not convert.. If the. Though there is no dilution cost,. the firm pays for all the debt.. 3.2 Equilibria of the Convertible Bond Calling Game The equilibrium concept used in the model is that of a Bayesian equilibrium defined as below. Definition:. t A Bayesian equilibrium is a set of conditional calling probabilities g ,. t G, B, and 1 , 2 , a ndas e tofs t oc khol de r s ’be l i e f s p , d. t d C , NC, and 1 , 2 ; where (i) g maximizes the f i r m’ s d. expected valve and (ii) p s a t i s f i e sBa y e ’ sr ul e . The model constructed in the previous section has multiple Bayesian equilibria, which are consistent with any kind of beliefs.. These equilibria contain pure. strategies under both degenerate and non-degenerate probability distributions of the outsiders’beliefs.. Lemma 3.1. The features of these equilibria are discussed below.. For each historical performance 1 {S , F } , there exists a pooling equilibrium where no firm will call the convertible bonds - that is, t g 0t .. 23.

(32) Proof Suppose that, by observing a firm calling a bond, the stockholders believe the firm to be type-B.. C Therefore, p 0 .. It follows that:. C v( p ) [ E (2 1) H ] 1 VG1 0 (1 ) N (1 ) N. (A3.1). C v( p ) 1. [ E (2 1) H ] 0 (1 ) N (1 ) N. B 1. V. (A3.2). v( pNC1S ) (1 ) [v( p NC1F ) D] NV (1 ) N N {[ E (2 1) H ] (1 )(1 )[ E (2 1) H D]} G . (1 ) N. 0 (A3.3). (1 ) v( p NC1S ) [v( pNC1F ) D] NV (1 ) N N (1 )[ E (2 1) H D]} {(1 )[ E (2 1) H ] B . (1 ) N. 0 (A3.4). After the algebraic calculation, the boundary [. D ,1) is obtained so that E D. (A3.3)-(A3.1)>0 and (A3.4)-(A3.2)>0. Q.E.D.. This implies that if the proportion of the stocks converted from the bonds is large enough ( [. D ,1) ), then no matter what type the firm is, the expected value for a E D. non-calling firm will be higher than that for a calling firm.. Thus, the firm will not be. better off to announce a call-back of the convertibles at time 1.. Lemma 3.1 is a common result in the reputation model.. If we make those. beliefs sufficiently unfavorable to one side of the players, then we can support a pooling equilibrium.. In this case, calling a bond is a zero-probability event, and we. can refer to such an event with the belief that the firm is of the lowest quality, thus making “ no calling”an equilibrium.. An equilibrium with a zero-probability event is. defined as a degenerate equilibrium.. The degenerate pooling equilibrium is due to. 24.

(33) the assumption of the investors’degenerate beliefs regarding a firm’ s type. Proposition 3.2 proposes another degenerate equilibrium.. Lemma 3.2. For each historical performance 1 {S , F } , there exists a pooling equilibrium where both types of firms will call the convertible bonds t that is, g 1t .. Proof In Lemma 3.1 the assumptions t equilibrium g 0 .. B g 0 and. G g 0. form a pooling. Consider the other assumption that the stockholders believe. the firm to be type-G when observing a firm calling.. C Therefore, let p 1 .. It. follows that: C v( p ) 1S. [ E (2 1) H ] 0 (1 ) N (1 ) N. (A3.5). C v( p ) [ E (2 1) H ] 1S VB1 0 (1 ) N (1 ) N. (A3.6). G 1. V. v( pNC1 S ) (1 ) [v( pNC1 F ) D] NVG (1 ) N N {[ E (2 1) H ] (1 )(1 )[ E (2 1) H D]}. (A3.7) (1 ) N. v( pNC1 S ) (1 ) [v( pNC1 F ) D] NV (1 ) N N [ E (2 1) H D]} {(1 )[ E (2 1) H ] (1 ) . 0. B . (1 ) N. 0 (A3.8). After the algebraic calculation, the boundary (0,. D ] is obtained so that E D. (A3.5)-(A3.7)>0 and (A3.6)-(A3.8)>0. Q.E.D.. Here forms another degenerate equilibrium under investors’degenerate beliefs. Lemma 3.2 implies that if the proportion of the stocks converted from the bonds is small enough ( (0,. D ] ), then no matter what type the firm is, the expected E D 25.

(34) value of a calling firm is higher than that for a non-calling firm.. The firm will hence. choose to announce a call-back to the convertibles at time 1.. Lemma 3.1 and. Lemma 3.2 analyze the conditions for two degenerate equilibria to exist.. In this. paper we focus on two non-degenerate equilibria under investors’non-degenerate beliefs.. Propositions 3.1 and 3.2 will show the features of these two equilibria.. Proposition 3.1. For a given level of the firm’ s reputation, there exists a separating equilibrium where type-G firms will not call the convertible bonds, while type-B firms will call as long as the reputation effects G dominate the dilution effects - that is, g 0 and g B 1.. Proof Comparing the marginal benefit ( MB ) from calling convertible bonds for a type-G firm with that for a type-B firm, (A9) is obtained. MB (VG1 NVG ) (VB1 NVB ) (2 1){[(1 )v( pNC1 F ) v( pNC1 S )] /(1 ) N D / N } (A3.9) Assume that the reputation effects dominate the dilution effects so that we have. (1 )v( pNC1F ) v( pNC1S ) .. We then have (A3.9)<0 so that VG1 NVG 0 and. VB1 NVB 0 . There exists a subgame equilibrium where type-G firms will not call, while type-B firms will. Q.E.D.. In Proposition 3.1 a separating equilibrium exists as the investors believe that the reputation value which a firm will obtain from a future successful project will exceed the dilution loss due to the voluntary conversion at time 2.. The benefit from calling. the convertible bonds is negative for a good management quality firm, which prompts a type-G firm not to call the convertible bonds.. On the other side, the benefit from. calling the convertible bonds is positive for a bad management quality firm, which indicates that a type-B firm will make a conversion-forcing call at time 1.. As a. type-B firm recognizes its future failure of the project, it calls back the convertible bonds at time 1 to force conversion rather than to repay the debt, D, at time 2.. 26.

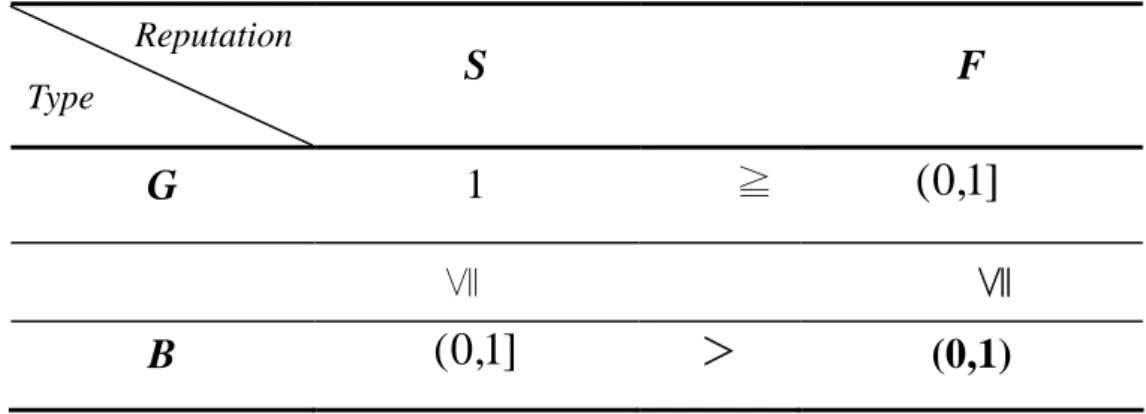

(35) Proposition 3.2. There exists a separating equilibrium where those firms who have obtained good reputations will not call the convertible bonds, while the others who have suffered bad reputations will call as long as past reputation dominates - that is, g St 0 and g Ft 1t {G, B} .. Proof No matter what type the firm is, the value for a calling firm with a successful past is:. v( p SC ) VSt , (1 ) N. (A3.10). and the value for a calling firm with a failed past is:. v( p FC ) VFt . (1 ) N. (A3.11). Furthermore, the expected value for a non-calling firm with a successful past is: NC NC v( p SS ) (1 ) [v( p SF ) D] NV , (1 ) N N t S. (A3.12). and the expected value for a non-calling firm with a failed past is: NC NC (1 ) v( p FS ) [v( p FF ) D] NVFt . (1 ) N N. (A3.13). Comparing the marginal benefit ( MB t ) from calling convertible bonds for firms with good reputations with that for firms with bad reputations, (A3.14) is obtained. MB t (VSt NVSt ) (VFt NVFt ) NC NC NC NC [v( pSC ) v( pFC )] [(1 )v( pFF ) v( pSS )] (1 ) [v( pFS ) (1 )v( pSF )]. (1 )(2 1) D (A3.14) Assuming that the past reputation dominates,4 the second and the third terms of the right-hand side will be negative, which makes (A3.14) also be negative. is negative, VSt NV St 0 and VFt NV Ft 0 .. As (A3.14). There exists a subgame equilibrium. where the good reputation firms will not call, while the bad reputation firms will. Q.E.D.. 4. The outsiders believe that firms with a successful past are more likely to be type-G firms, no matter whether the projects are successful or a failure in the second period. 27.

(36) In Proposition 3.2 another separating equilibrium exists as the investors believe that the firm with a good past is more likely to be a good firm.. Under such a belief,. the reputation value which a firm obtained from its past success will exceed the dilution loss associated with the voluntary conversion at time 2.. Thus, the benefit. from calling the convertibles is negative for a good reputation firm, which induces a good reputation firm to not call the convertible bonds.. On the other side, the benefit. from calling is positive for a bad reputation firm, which makes a bad reputation firm call the convertible bonds at time 1.. Again, the choice by a bad reputation firm is. due to a fear of eroding the firm’ s endowment wealth when it is necessary to repay the debt at time 2.. 3.3 Main Reputation Effects and Empirical Evidence According to the analyses from the equilibria of the convertible bond calling game, we propose three information effects in the decision to call the convertible bonds.. First, as stated in Proposition 3.1, the performance of the project in the 2nd. period influences the firm’ s value.. Future success with a non-calling policy adds a. reputation value to the firm, which is regarded as the feedback reputation effect. Second, as stated in Proposition 3.2, the firm’ s reputation influences the firm’ s value. Past success with a non-calling action adds a reputation value to the firm. regarded as the direct reputation effect.. This is. Third, combining Proposition 3.1 and. Proposition 3.2, the firm conveys a signal of good management quality by not calling its convertibles.. On the contrary, calling will signal the firm’ s poor performance in. the future and is regarded as the signaling effect.. 3.3.1 Feedback Reputation Effect In Proposition 3.1 as long as the reputation effect dominates the dilution effect, the firm with good management quality will not call the convertibles - that is, if the investors believe that the reputation value obtained from future success exceeds the dilution cost due to the voluntary conversion at time 2, then firms should wait until time 2 instead of making a conversion-forcing call at time 1.. However, those that. make a conversion-forcing call must perceive a failure in the future. A conversion-forcing call in advance can prevent a failed firm from repaying at time 2. Hence, we find that a type-B firm calls the convertible bond.. 28.

(37) On the other side, those that will succeed at time 2 will wait for the voluntary conversion.. Since these firms that will succeed are more likely to be perceived as. type-G firms, the future success (good reputation) adds value to firms with good management quality.. Thus, a type-G firm will not make a call on the convertibles.. We call this the feedback reputation effect.. The prediction is consistent with the empirical study by Ofer and Natarajan (1987).. Except for the stock price reaction, they directly tested the firm’ s economic. performance and saw a significant decline in the firm’ s earnings after the call. Further in their study, they identified that the call was due to the expectation of a future decline.. Hence, if the firm anticipates a success in the future, then it chooses. not to call so as to obtain the reputation value in addition to its original firm value.. 3.3.2 Direct Reputation Effect As in Proposition 3.2, assuming that the past reputation dominates, the investors believe that those succeeding in the 1st period are more likely to be type-G firms, no matter whether they will succeed or not in the 2nd period.. In this case, those firms. that have had good reputations will obtain a reputation value and choose not to call the convertibles.. We call this the direct reputation effect.. On the contrary, those. having had bad reputations are less likely to be perceived as type-G firms. Accordingly, a decrease in the firm’ s value forces a type-B firm with bad reputation to make a conversion-forcing call at time 1.. The essence of this reputation model is to identify that it is indeed a reputation-building activity not to call back the convertible bonds.. As emphasized. by Wilson (1985), the key ingredient of the reputation effects is that a player can adopt actions that sustain the probability assessments made by other participants which yield long-term consequences.. In our application model of the convertible. bond calling game, if a firm continues to establish its reputation by not calling its convertible bonds, then it builds up its long-term reputation to be a firm of good management quality and hence generates trust in the firm by bondholders and stockholders.. This gives another reason for the discrepancies between the short-term price 29.

(38) reversal and the long-run underperformance of the calling firm’ s common stock. Contrary to the positive short-run stock price performance found by Byrd and Moore (1996) and Ederington and Goh (2001), Datta et al. (2003) evaluated the long-term effect on the common stock price after the call and found that over a five-year post-call period, the common stocks of calling firms underperform their benchmarks. In their view, they agreed with Daniel et al. (1998) by stating that the relatively short post-call time horizon examined by previous studies, like Byre and Moore (1996) or Ederington and Goh (2001), is insufficient to draw reliable conclusions regarding the information conveyed by conversion-forcing bond calls.. We further suggest that it is. the accumulated rent generated from the firm’ s reputation that is being neglected when evaluating in the short run - that is, when the firms play in an economy with infinite generations, they accumulate their reputation rents by not calling the convertible bonds in the long run.. 3.3.3 Signaling Effect Based on Propositions 3.1 and 3.2, we conclude a signaling effect as proposed by Harris and Raviv (1985).. Harris and Raviv (1985) looked at a firm’ s decision as an. informational problem and proposed a signaling theory stating that a decision to call is perceived by the market as a signal of unfavorable prospects.. Thus, the manager. calls after receiving a “ bad”message and never calls after receiving a “ good” message.. The separating equilibrium obtained in the reputation model implies that a type-G firm will not call the convertible bonds. succeed in time 2.. A type-G firm is also more likely to. Thus, not calling conveys good news for the firm’ s future.. On. the other side, a type-B firm will choose to make a conversion-forcing call and a type-B firm is more likely to fail in the future.. Hence, calling signals a bad future. for the firm’ s project.. Empirical studies by Ofer and Natarajan (1987) and Datta et al. (2003) confirm the signaling theory.. Ofer and Natarajan (1987) found that a firm’ s earnings decline. significantly after convertible calls.. Datta et al. (2003) evaluated data over a. five-year post-call period, seeing that the common stocks of calling firms underperform their benchmarks.. Both prove that a conversion forcing call conveys 30.

(39) bad news.. 3.4 Conclusion of Chapter 3 The issue of an optimal convertible call policy has generated a lot of discussion in the literature.. Some suggest that calling signals bad prospects for the calling firms,. while others do not.. The contributions of reputation model to the literature are as. follows.. First, as for the convertible bond call decision, the prediction of this model is consistent with the signaling hypothesis, where a good management quality firm will call the convertible bond and a bad management firm will not.. Thus, a convertible. bond call is regarded as a bad news. However, unlike Harris and Raviv (1985), the author reduces the model to a two-period game.. By assuming that the outsiders can. observe the 1st period performance of the project, the outsiders can assess the firm’ s reputation at T=1.. This formulation reduces the outsiders’learning process.. Further, this model takes af i r m’ sr e put a t i onva l uei nt oc ons i de r a t i ona ndpr ovides an alternative a ppr oa c ht oi nve s t i g a t eaf i r m’ sc onve r t i bl ec a l lpol i c y . Except for the signaling role, we identify that for a firm with a successful history as well as good management quality, the choice of non-calling is a reputation-building activity. Hence, the call policy also plays as a mechanism to build up a firm’ s reputation.. Further, the author proposes that reputation does affect a firm’ s convertible bond call policies. call policies.. Two more reputation effects on the decision of convertible bond. The feedback reputation effect suggests that the firm’ s future success. adds a reputation value to the firm, making non-calling to be optimal for the good firm.. The direct reputation effect suggests that the firm which has had a good. reputation obtains a reputation value, again making non-calling the optimal choice for the good firm.. The essence of the reputation model implies that non-calling is a. reputation-building activity.. If the firm is always playing the non-calling activity,. then it establishes trust to the bondholders as well as the stockholders concerning management quality.. This reputation rent reconciles the disputes of the impacts on. the common stock price performances.. 31.

(40) 4. Reputation Effects on IPO Activities What kind of firm chooses to go public?. Why do firm owners share their. golden pot with the public since the firm makes money for their own selves? reputation affect firms’decisions to go public? on the IPO activities? shareholders.. Does. How does the reputation effect work. Such questions are widely asked by potential and the current. Theoretic analyses on the decisions to go public focus on how. information cost affects a firm’ s decision to go public (e.g. Chemmanur and Fulghieri, 1999).. But the intrinsic motive that drives a firm to go public, such as the firm’ s. reputation, is less discussed.. In this chapter, the author is going to construct a. reputation model to analyze how information contents (the firm’ s reputation levels) affect a firm’ s decision to go public.. Reputation models have been applied to predict a variety of managerial decisions (e.g. Kreps and Wilson, 1982; Milgrom and Roberts, 1982; Tedelis, 1999 and Cabral, 2000, etc.), but to my best knowledge, this is the first reputation model on IPO activities.. To identify the reputation effects on IPOs, this paper assumes a firm needs. funds for a new project.. The firm chooses between going public or not in order to. generate funds needed.. The firm’ s value is determined by the firm’ s management. quality, which is private information to the public.. Investors assess their beliefs of. the management quality as being good through three steps:. (1) their observations of. the firm's past performance, (2) the firm’ s going public decision, and (3) their expectations of the firm’ s future performance.. This formulation meets the features. of reputations, which establish links between past behavior and expectations of future behavior (Mailath and Samuelson, 2006).. 4.1 The Model An economy with three dates is considered, indexed by T=0, 1, and 2 as shown in Figure 4.1. T=0).. The firm is established at the beginning of the first period (time 0 or. After one period of operation (time 1 or T=1), the firm decides to participate. in a new project and needs funding for this investment.. In this section I am going to. analyze the firm’ s reputation effects on the decision to go public.. Thus, the. manager’ s choice is whether to generate the funds needed through the public markets or not, regardless of some other alternative financing tools.. If the manager chooses. to generate the funds from the public, then the firm needs to go public and sell a 32.

數據

Outline

相關文件

With λ selected by the universal rule, our stochastic volatility model (1)–(3) can be seen as a functional data generating process in the sense that it leads to an estimated

The analytic results show that image has positive effect on customer expectation and customer loyalty; customer expectation has positive effect on perceived quality; perceived

Regarding Flow Experiences as the effect of mediation, this study explores the effect of Perceived Organizational Support and Well-being on volunteer firemen, taking volunteer

Secondly, in Chapter 3 we analyze the effect of differentiated soft recreational activity marketing strategies used by firms on the prices of recreational service, profits,

Finally, with extending Nerlove and Arrow’s advertising model and considering the adjustment cost of advertising expenditures as well as learning effect accumulated by

The permutation performance of Tango Route March (Tango_RM) can get the most approach effect of best prediction permutation.. The method of permutation effect analysis takes

Based on the DOE analysis, THM containing chlorine ( CHC 3 +CHCl 2 Br) formation was dominantly affected by bromide ion with negative effect and concentration of humic

(1)The service quality has positive direct effect on customer satisfaction;(2)The customer satisfaction has positive direct effect on customer loyalty; (3)The trust has