言語及手勢中之隱喻表達 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) The Expression of Metaphor in Speech and Gesture. BY. 立. 治 政 Yu-tung Chang 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. n. a l A Thesis Submitted to the i v n Graduate C hInstitute of Linguistics U e n g c h iof the in Partial Fulfillment Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. July 2014.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2014 Yu-tung Chang All Rights Reserved. iii. i n U. v.

(5) Acknowledgements 致謝. 由衷地感謝我的指導教授徐嘉慧老師。老師耐心的指導,使我能順利完成這份論文。 謝謝老師每週不厭其煩地和我討論,提出許許多多精闢的建議,並騰出時間反覆協助我 修正論文內容。擔任老師的計畫助理期間,老師細心的教導,使我習得許多知識,且有 幸窺見手勢的迷人之處。老師嚴謹的治學態度、對研究的熱誠以及對知識的好奇心,更 讓我認識到面對生活的正向態度。 感謝我的論文口試委員:賴惠玲老師及張妙霞老師。口委老師們提供的寶貴意見, 使這份論文能更加完善。還要感謝 Ruth Martin 老師在百忙之中替我校稿。書信往來間,. 政 治 大 學至研究所,賦與我種種語言學知識的老師。感謝何萬順老師、蕭宇超老師、黃瓊之老 立 師、萬依萍老師、詹惠珍老師、莫建清老師、John Newman 老師、殷允美老師、張郇慧. Ruth 老師溫暖的言辭及鼓勵,亦安定我徬徨的心。知識的累積並非一蹴可幾,謝謝從大. ‧ 國. 學. 老師、鐘曉芳老師以及薩文蕙老師。你們不但傳遞給我不同領域的知識,還有對學問的 思辨方式。特別要感謝助教惠玲學姊,在行政方面提供許多協助。. ‧. 感謝這三年間和我一起前進的大家。感謝培禹學姊、婉君學姊以及侃彧學姊,很高. y. Nat. 興能和你們一起進行手勢分析,討論相關知識。尤其感謝侃彧學姊,協助我完成論文分. sit. 析的 inter-rater reliability 部分。也謝謝語言所 100 級的夥伴們,和你們一同上課、開讀. er. io. 書會與吃喝玩樂的時光,繽紛了我的研究生生活。你們的鼓勵的話語,亦帶給我前進與. al. v i n Ch 感謝好人緣的秋芳、芯妤和莞婷,總是在我的研究需要時,積極幫忙募集受試者。 engchi U 與你們相處永遠不乏趣事,繽紛了我的生活。感謝于涵的傾聽,你的專業與理性,總是 n. 堅持的動力。一齊奮鬥的記憶,我想自己永遠捨不得讓它褪色。. 幫我把灰色心境轉變為明色調,讓我能重整心情繼續前行。謝謝鈺書和芳婷,讓我盡情 撒嬌,你們的安慰和鼓勵,是我重要的精神糧食。 最後要感謝我最愛的家人。謝謝爸爸和媽媽在物質層面及心靈層面的支持。你們的 一言一行都讓我感受到滿滿的關懷和愛,也謝謝你們願意尊重並支持我的決定。感謝弟 弟,總是出其不意地逗我開心,妙語如珠的回應,往往替我稀釋了沮喪或煩躁的心緒。 感謝大家的陪伴,讓我知道自己並非踽踽獨行,且堅持至今。. iv.

(6) Table of Contents. Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ ix Chinese Abstract ....................................................................................................................... xi English Abstract ...................................................................................................................... xiii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1. 政 治 大. 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1. 立. 1.2 The Current Study ............................................................................................................ 7. ‧ 國. 學. CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................... 9 2.1 Conceptual Metaphor in Language .................................................................................. 9. ‧. 2.1.1 Overview of Conceptual Metaphor .................................................................. 10. sit. y. Nat. 2.1.2 The Nature of Metaphor ................................................................................... 13. io. er. 2.1.3 The Embodiment of Metaphor.......................................................................... 17. al. v i n C h Production.............................................................. 2.3 Theoretical Hypotheses of Gesture 26 engchi U n. 2.2 Conceptual Metaphor in Gesture.................................................................................... 21. 2.3.1 The Free Imagery Hypothesis ........................................................................... 26 2.3.2 The Lexical Semantics Hypothesis ................................................................... 28 2.3.3 The Interface Hypothesis .................................................................................. 29 2.4 Summary ........................................................................................................................ 32 CHAPTER 3 DATA AND METHODOLOGY ...................................................................... 35 3.1 Data ................................................................................................................................ 35 3.2 Selection Criteria of Metaphoric Expressions ................................................................ 36 3.3 Classification of Metaphor Types .................................................................................. 41 3.4 Classification of Source-Domain and Target-Domain Concepts ................................... 48. v.

(7) 3.5 Temporal Patterning of Speech and Gesture .................................................................. 51 3.6 Summary ........................................................................................................................ 53 CHAPTER 4 METAPHORS IN LANGUAGE AND GESTURE .......................................... 55 4.1 Cross-Modal Manifestation of Metaphors ..................................................................... 55 4.2 Cross-Modal Manifestation of Source Domains ............................................................ 71 4.3 Cross-Modal Manifestation of Target Domains............................................................. 75 4.4 Cross-Modal Manifestation of Source-Target Correspondences ................................... 80 4.5 Different Types of Cross-Modal Temporal Patterning .................................................. 90 4.6 Summary ........................................................................................................................ 94. 政 治 大. CHAPTER 5 GENERAL DISCUSSION ................................................................................ 97. 立. 5.1 The Habitual Expression of Metaphor Types ................................................................ 98. ‧ 國. 學. 5.2 The Sources and Targets in the Expression of Metaphors ........................................... 100 5.3 The Correspondences between the Source and Target Domains ................................. 103. ‧. 5.4 Speech and Gesture Production.................................................................................... 106. sit. y. Nat. 5.5 Summary ...................................................................................................................... 112. io. er. CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION................................................................................................ 115. al. 6.1 Summary of the Thesis................................................................................................. 115. n. v i n 6.2 Limitations and Future StudyC ....................................................................................... 119 hengchi U. REFERENCES ...................................................................................................................... 122 Appendix 1: Gesture and speech transcription conventions .................................................. 131 Appendix 2: Screenshots for the line drawings in Table 18 .................................................. 132. vi.

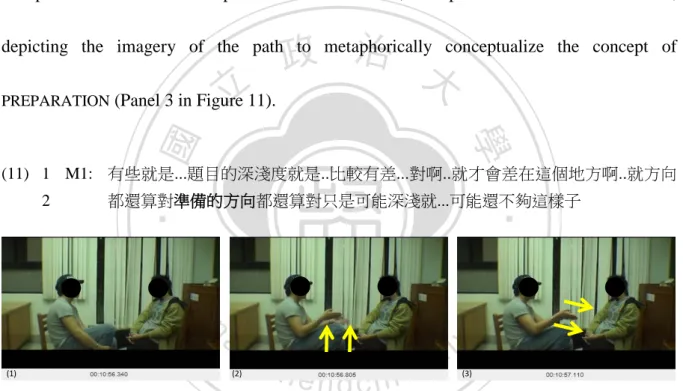

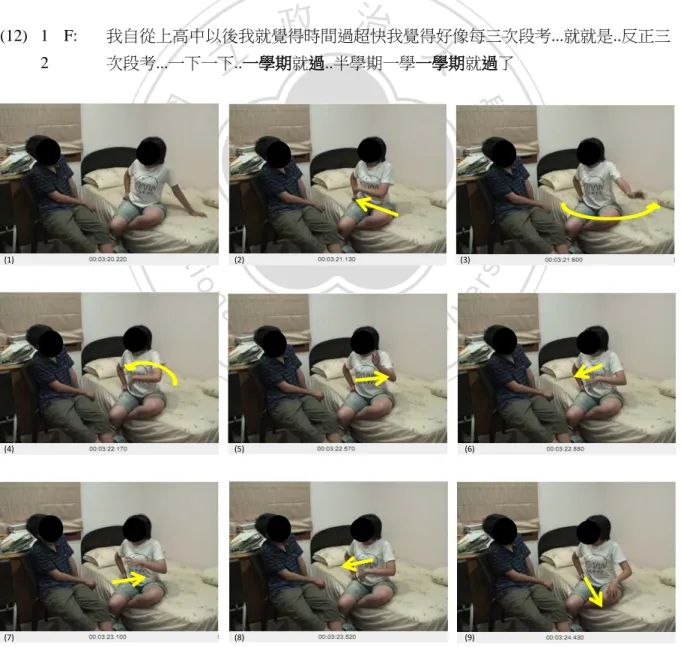

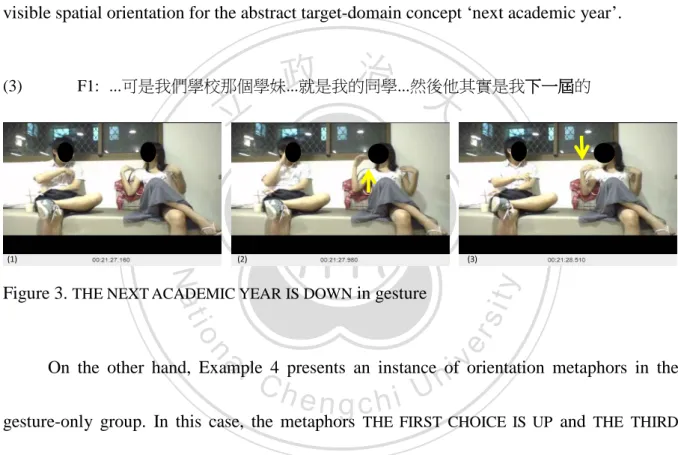

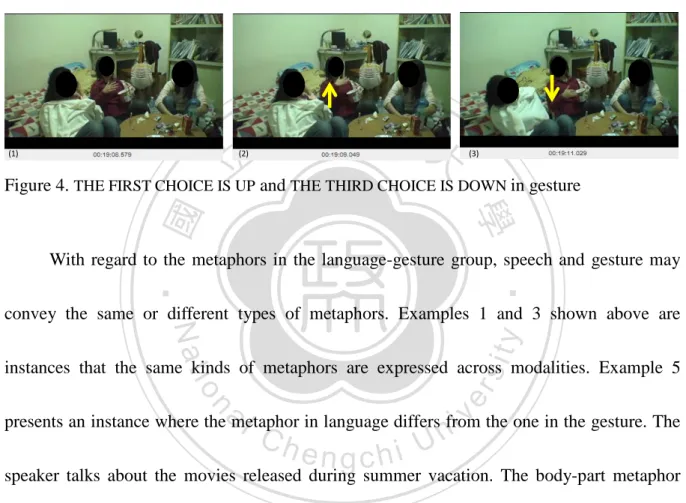

(8) List of Figures. Figure 1. STATE OF CONFUSION IS AN OBJECT in gesture..................................................... 37 Figure 2. HARDSHIP IS AN OBJECT in gesture ........................................................................ 37 Figure 3. THE NEXT ACADEMIC YEAR IS DOWN in gesture ................................................... 38 Figure 4. THE FIRST CHOICE IS UP and THE THIRD CHOICE IS DOWN in gesture ................. 39 Figure 5. THE END OF SUMMER VACATION IS AN OBJECT in gesture .................................. 40 Figure 6. THE FORMER IS THE FRONT in gesture ................................................................... 52 Figure 7. SPEECH CONTENT IS AN OBJECT in gesture............................................................ 59. 政 治 大. Figure 8. A GROUP OF PEOPLE IS A BOUNDED AREA in gesture ........................................... 60. 立. Figure 9. MORNING IS UP and AFTERNOON IS DOWN in gesture............................................ 60. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 10. HIGH TEMPERATURE IS UP in gesture ................................................................... 61 Figure 11. THE DIRECTION OF PREPARATION IS THE DIRECTION OF PATH in gesture ........ 62. ‧. Figure 12. THE PASSAGE OF A SEMESTER IS MOTION in gesture .......................................... 63. sit. y. Nat. Figure 13. SHIFT OF THE SPEECH CONTENT IS MOTION in gesture ....................................... 64. io. er. Figure 14. STOCK MARKET IS A CONTAINER in gesture ........................................................ 65. al. v i n CIShTRANSFERRING OBJECTS Figure 16. PROVIDING KNOWLEDGE in gesture ...................... 67 engchi U n. Figure 15. TAIPEI BASIN IS A CONTAINER in gesture ............................................................ 66. Figure 17. PSYCHOLOGICAL COMPELLING IS PUSHING in gesture ....................................... 68 Figure 18. CHOOSING PASSENGERS IS PICKING OBJECTS in gesture .................................... 69 Figure 19. PLANNING IS WEIGHING in gesture ....................................................................... 72 Figure 20. GOING TO THE LAVATORY IS AN OBJECT in gesture ........................................... 75 Figure 21. LOW LIVING STANDARD IS DOWN in gesture ....................................................... 92 Figure 22. DAYTIME IS AN OBJECT in gesture ...................................................................... 132 Figure 23. THE UNSTABLE TERM OF STOCKS IS A PATH in gesture .................................... 132 Figure 24. KNOWING IS AN OBJECT in gesture ..................................................................... 132. vii.

(9) Figure 25. A SEQUENCE IS AN OBJECT in gesture ................................................................ 133 Figure 26. LIGHT INTENSITY IS AN OBJECT in gesture ........................................................ 133. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. viii. i n U. v.

(10) List of Tables. Table 1. Common source domains of metaphorical expressions in English (Kövecses 2002: 16-20) ......................................................................................................................... 14 Table 2. Common target domains of metaphorical expressions in English (Kövecses 2002: 21-24) ......................................................................................................................... 15 Table 3. Image schemas proposed by Johnson (1987: 126) .................................................... 19 Table 4. Image schemas proposed by Cienki (1997: 12) ......................................................... 49 Table 5. Types of metaphors in Mandarin conversations ........................................................ 56. 政 治 大 Table 7. Source-domain concepts in Mandarin conversations ................................................ 73 立 Table 6. Source-domain concepts and examples ..................................................................... 72. ‧ 國. 學. Table 8. Correspondences between the source domains and the metaphor types ................... 74 Table 9. Target-domain concepts and examples ...................................................................... 76. ‧. Table 10. Target-domain concepts in Mandarin conversations ............................................... 77 Table 11. Correspondences between the target domains and the metaphor types ................... 79. y. Nat. sit. Table 12. Source-to-target correspondences in Mandarin conversations (based on the types of. n. al. er. io. sources) .................................................................................................................... 80. i n U. v. Table 13. One-source-to-many-targets correspondences in metaphors in the language-gesture. Ch. engchi. group ........................................................................................................................ 81 Table 14. One-source-to-many-targets correspondences in metaphors in the gesture-only group ........................................................................................................................ 81 Table 15. Source-to-target correspondences in Mandarin conversations (based on the types of targets)...................................................................................................................... 85 Table 16. Many-sources-to-one-target correspondences in metaphors in the language-gesture group ........................................................................................................................ 85 Table 17. Many-sources-to-one-target correspondences in metaphors in the gesture-only group ........................................................................................................................ 85 Table 18. The many-sources-to-one-target correspondences and examples ........................... 86. ix.

(11) Table 19. Temporal patterning of speech and gestures............................................................ 91 Table 20. Linguistic units of the lexical affiliates of the metaphoric gestures ...................... 109. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

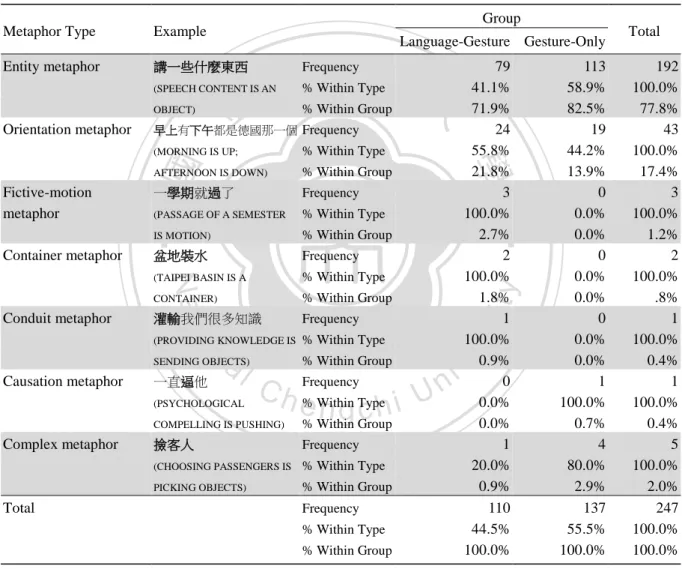

(12) 國. 立. 政. 治. 大. 學. 語. 言. 學. 研. 究. 所. 碩. 士. 論. 文. 題. 要. 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:言語及手勢中之隱喻表達 指導教授:徐嘉慧 博士 研究生:張宇彤 論文提要內容:(共一冊,二萬五千二百三十四字,分六章) 本文旨在研究中文日常會話中語言及手勢之隱喻表達,並根據 Lakoff 和 Johnson 的. 政 治 大. 概念隱喻理論(Conceptual Metaphor Theory),探討語言與手勢之慣常隱喻表達以及兩. 立. 者的互動關係。本文共分析 247 筆隱喻。其中 110(44.5%)筆在語言及手勢中同時傳. ‧ 國. 學. 遞同一類型之隱喻概念;另外 137(55.5%)筆只藉著手勢傳達隱喻概念。 日常會話語料中共發現九種隱喻類型,包括身體譬喻、因果譬喻、傳輸譬喻、容器. ‧. 譬喻、實體譬喻、虛擬移動譬喻、 空間方位譬喻、擬人譬喻以及複合譬喻。此外,根. y. Nat. sit. 據意象圖式之概念,本研究也區分了九種來源域概念:活動、身體部位、容器、虛擬移. n. al. er. io. 動、力、物體、路徑、人與空間。隱喻可以用來表達繁多的目標域概念,以下八種目標. i n U. v. 域概念在語料中至少出現五次:群體、心理活動、具體活動、程度、順序、說話內容、 狀態與時間。. Ch. engchi. 研究發現,實體譬喻(77.8%)及空間方位譬喻(17.4%)在日常會話中最為普遍。 根據 Lakoff 和 Johnson (1980c) ,人們對於實體之經驗提供了多種方式來表達其他抽 象概念,例如我們能集合、分類、量化物體以及確立物體之情勢。Lakoff 和 Johnson 亦表示,空間方位是構成某些概念(例如:高地位)之不可或缺的部分;缺乏空間方位 譬喻,很難利用其他方式表達。因此,日常會話中經常使用實體譬喻及空間方位作譬喻。 空間方位譬喻之來源域概念可以是空間或路徑,而其他類型之譬喻僅來自單一來源域。 最常見的來源域概念為物體,而常見之目標域概念則有狀態、時間及具體活動。有關單 一來源域至多元目標域之隱喻對應,來源域概念包括物體、空間、路徑、虛擬移動、活. xi.

(13) 動及容器,可用以表達多個目標域。有關多元來源域至單一目標域之隱喻對應,目標域 概念包括時間、心理活動、說話內容、順序及程度,可藉由多個來源域表達。 本文亦從三方面探討語言及手勢如何共同表達隱喻概念:語言及手勢之時序、手 勢之關聯詞彙、語言及手勢之語意配合,以瞭解關於語言與手勢產生之不同理論假說。 Lexical Semantic Hypothesis 認為手勢源自於詞項之語意內容,也主張手勢出現之時間通 常先於相關詞彙,以利詞彙搜索。Interface Hypothesis 則認為空間-運動訊息及語言訊息 在產生手勢之過程中相互影響,因此手勢及語言會同時出現,而本研究確實發現手勢大 多與相關詞彙同時出現。再者,17.4%的手勢對應片語,而不限於單詞,此結果與 Lexical. 政 治 大 語言及手勢傳達不同的語意訊息,結果支持 Interface Hypothesis 之論說—手勢和語言可 立 Semantic Hypothesis 之見解相悖。最後,研究發現 55.5%之隱喻僅藉由手勢表達。因此. 各自表意。上述三項結果支持 Interface Hypothesis 之論點。. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xii. i n U. v.

(14) Abstract This thesis explores the linguistic and gestural expressions of metaphors in daily Chinese conversations. Following Lakoff and Johnson’s framework of Conceptual Metaphor Theory, the present study aims to investigate the habitual expressions of metaphors in language and gesture and the collaboration of the two modalities in conveying metaphors. The present study examined 247 metaphoric expressions. The data includes 110 (44.5%) metaphors being conveyed concurrently by speech and gesture—the two modalities expressing the same type of metaphors—and 137 (55.5%) metaphors being conveyed in gesture exclusively. Nine types of metaphors were found in the daily conversations: Body-part, Causation,. 政 治 大 metaphors. Furthermore, based立 on the notion of image schema, nine types of source-domain Conduit, Container, Entity, Fictive-motion, Orientation, Personification, and complex. ‧ 國. 學. concepts were recognized: ACTIVITY, BODY-PART, CONTAINER, FICTIVE-MOTION, FORCE, OBJECT, PATH, PERSON, and SPACE. A great variety of target-domain concepts were realized. ‧. via metaphors; the present study focused on eight types, each occurred more than five times in the data: GROUP, MENTAL ACTIVITY, (physical) ACTIVITY, DEGREE, SEQUENCE, SPEECH. Nat. sit. y. CONTENT, STATE, and TIME.. io. al. er. The results showed that Entity metaphor (77.8%) and Orientation metaphor (17.4%). n. are the most common types in daily conversation. According to Lakoff and Johnson (1980c),. Ch. i n U. v. people’s bodily experiences of physical objects provide basis for viewing other abstract. engchi. concepts; for instance, we can group, categorize, quantify, and identify aspects of objects. They also suggested spatial orientations are essential parts of certain concepts (e.g., high status); without orientation metaphors, it would be difficult to find alternative ways to express the ideas. Therefore, Entity metaphor and Orientation metaphor are frequently employed in metaphoric expressions. Orientation metaphors are based on two source domains, SPACE and PATH; the other types of metaphors are all associated with a single source domain. The most. common type of source domains is OBJECT, whereas the common types of target domains are STATE, TIME, and PHYSICAL ACTIVITY. With regard to the one-source-to-many-targets. correspondences, the source domains of OBJECT, SPACE, PATH, FICTIVE-MOTION, ACTIVITY, and CONTAINER could be used to express numerous target-domain concepts metaphorically. As to the many-sources-to-one-target correspondences, the target-domain concepts of TIME, xiii.

(15) MENTAL ACTIVITY, SPEECH CONTENT, SEQUENCE, and DEGREE could be represented by. multiple source-domain concepts. The collaboration of language and gesture enables us to evaluate the various hypotheses of speech-gesture production, based on the temporal relation between language and gesture, the lexical affiliates of metaphoric gestures, and the semantic coordination across the two modalities. The Lexical Semantics Hypothesis suggests that gestures are generated from the semantic of a lexical item (or a word) and that gestures tend to precede their lexical affiliates to help lexical search. The Interface Hypothesis proposes that spatio-motoric and linguistic information interact with each other during gesture production, so gestures and the related speech will occur at the same time. The present study found that gestures mostly. 政 治 大 associated with grammatical phrases rather than words. This result opposes to the claim of 立 the Lexical Semantics Hypothesis. Last, the present study found that 55.5% of metaphoric. synchronize with the associated speech. Moreover, 17.4% of metaphoric gestures are. ‧ 國. 學. expressions are being conveyed in gesture exclusively. The result supports the argument of the Interface Hypothesis that language and gesture can covey diverse semantic contents. ‧. respectively. Based on the above findings, the current study tends to support the Interface. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Hypothesis.. Ch. engchi. xiv. i n U. v.

(16) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. 1.1 Introduction The notion that metaphor is conceptual can be traced back to Reddy’s (1979) framework on how people conceptualize communication by “conduit metaphor”. In this kind. 政 治 大. of metaphor, people put thought or feelings into words, and language is regarded as a. 立. container which can bodily transfer thoughts or feelings. Namely, linguistic expression is. ‧ 國. 學. structured by following metaphors: IDEAS ARE OBJECTS, LINGUISTIC EXPRESSIONS ARE. ‧. CONTAINERS, and COMMUNICATION IS SENDING (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c). He estimated. Nat. io. sit. y. that “of the entire metalingual apparatus of the English language, at least seventy percent is. er. directly, visibly, and graphically based on the conduit metaphor” (Reddy 1979: 177), which. n. al. i n C suggests that ordinary English is metaphorical to a large extent. heng chi U. v. Lakoff and Johnson further structured the Conceptual Metaphor Theory. Lakoff and Johnson suggested that metaphor is a conceptual mapping from one domain to another domain. The source domain being used to understand another domain is typically concrete; the target domain is rather abstract (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c). However, it should be noted that the target domains we conceptualize via metaphors can be concrete, such as ACTIVITY in ACTIVITIES ARE CONTAINERS (Lakoff and Johnson 1980c: 31) and EYES in THE EYES ARE. 1.

(17) 2. CONTAINERS FOR THE EMOTIONS (Lakoff and Johnson 1980c: 50). Lakoff and Johnson’s. influential book Metaphors We Live By showed an attempt to respond to Davidson (1978) who claimed that a metaphor does not have senses other than its literal meanings and Searle (1979) who claimed that the truth condition of the literal meaning of a metaphor allows people to have metaphorical interpretations. Lakoff and Johnson rejected the traditional assumption that everyday language is all literal and state “linguistic metaphor is a natural part. 政 治 大. of human language” (Lakoff & Johnson 2003: 247). Also, the locus of metaphor is not in. 立. language but in thought; linguistic metaphor is the surface realization of the conceptual. ‧ 國. 學. metaphor which is based on the correspondence (or the mapping) from a source domain to a. ‧. target domain rather than similarity. 1 They also claimed that metaphor is grounded in both. Nat. io. sit. y. the body experiences and the socio-cultural experiences. Through studying metaphors in. al. er. language, Lakoff and Johnson suggested that conceptual metaphor is systematic and that a. n. v i n metaphor may highlight a certain C aspect an abstractUconcept (i.e., a concept might be h e ofn g chi defined by various metaphors from different facets. Following their framework, Kövecses (2002) studied the common source and target domains of the metaphoric expressions in English. His qualitative study provides evidence for the view that metaphoric correspondences are asymmetrical and that the corresponding direction is generally from a concrete concept to an abstract one.. 1. According to Lakoff (1993: 207), “metaphors are mappings, that is, sets of correspondences.” The term, ‘source-to-target correspondences’, is used in this thesis to refer to cross-domain mappings for the distinction between the conceptual metaphorical mapping and the cross-modal mapping between the linguistic and gestural modalities..

(18) 3. Several studies on metaphors in language in Chinese are based on the Conceptual Metaphor Theory as well. These studies depend mainly on the qualitative analysis of the metaphors collected from dictionaries or pop songs. Yu (1998) investigated the emotion metaphors, time metaphors, and event structure metaphors, Lin (2003) focused on body-part metaphor, Liu (2010) paid attention to the journey metaphor, and Lai (2011) researched the expressions of love metaphor. These works compared metaphoric expressions in Chinese and. 政 治 大. English and proposed that some metaphors are universal. In Wang’s (2010) study on pop. 立. songs, he also focused on the different types of metaphors of LOVE. His quantitative study. ‧ 國. 學. showed that people tend to conceptualize LOVE through event structure metaphors and. ‧. ontological metaphors.. Nat. io. sit. y. The previous studies on language have offered insightful thoughts about conceptual. al. er. metaphor, such as the common source-domain and target-domain concepts, the unidirectional. n. v i n C h the profiles of U correspondences between two domains, e n g c h i metaphors, and the embodiment of metaphors. Nonetheless, many of the studies focus solely on the qualitative data. Based on the insights provided in these studies, the present study would like to examine the metaphoric expressions from both the qualitative and quantitative perspectives. The present study collects metaphoric expressions from conversational data, which allow us to see the cross-modal manifestations of metaphors. With the quantitative data, we can have reliable information about the habitual expressions of metaphors as well as the synchronization and collaboration.

(19) 4. of linguistic and gestural modality. Since metaphor is conceptual, it should be able to be realized in various modalities. Gesture is thought to be a non-linguistic and independent source to reflect our metaphoric thinking (Cienki 2008; Cienki & Müller 2008; Müller 2008; Gibbs 2008b). Despite the fact that gesture is an independent modality to present metaphors, it has a close relationship with language. Regarding the manifestations of metaphors, there are different interactions between. 政 治 大. language and gesture (Cienki 1998; Cienki 2008; Müller 2008; Cienki & Müller 2008; Chui. 立. 2011, 2013). A metaphor may be expressed verbally but not in a co-speech gesture. A. ‧ 國. 學. metaphor may occur in gesture but not in accompanying speech. A metaphor may be jointly. ‧. Nat. io. sit. different metaphors at the same time.. y. manifested in both speech and gesture. Speech and co-speech gesture also can express. al. er. McNeill (1992) applied Lakoff and Johnson’s notion of conceptual metaphor to his. n. v i n C hbelong to one ofUthe gestural types; they “are like study of gesture. Metaphoric gestures engchi iconic gestures in that they are pictorial, but the pictorial content presents an abstract idea rather than a concrete object or event” (McNeill 1992: 14). McNeill observed that metaphoric gestures primarily appear in extranarrative contexts and proposes that the function of metaphoric gestures is to represent ideas which do not have physical forms. Nevertheless, he solely paid attention to the expressions of conduit metaphors (usually presented palm up with an open hand) in which an abstract idea is conceptualized as an object. It should be noted that.

(20) 5. a conduit metaphor is not the only metaphoric gesture; there are other types of metaphoric gesture occurring on a narrative level (Cienki 2008). In McNeill’s (2008) further study on unexpected metaphor—the metaphoric gestures which create images that are not established in the culture—he proposed that they serve to maintain the coherence and fluidity in the discourse as well. Nevertheless, the traditional way to collect gestural data from video records of. 政 治 大. participants narrating the plot of the cartoon comprising elaborate motion events has its. 立. limitation. Such a method helps to produce concrete referential gestures (the iconic gestures). ‧ 國. 學. but decreases the thought and utterances about abstract ideas which might be accompanied by. ‧. metaphoric gestures (Cienki 2008). To gain more metaphoric expressions in gesture, research. Nat. io. sit. y. on other styles of talk which involve abstract topics is needed. Other investigations about. al. er. metaphoric gesture include not only representations in narratives but also other kinds of talk,. n. v i n C h2008), lectures inUcollege (Mittelberg 2008; Núñez such as television interviews (Calbris engchi 2008), conversation interviews (Cienki 2008; Cienki & Müller 2008; Müller 2008), and spontaneous face-to-face conversation (Cienki & Müller 2008). There are studies on metaphoric gesture in Chinese discourse as well. Chui (2011; 2013) investigated the metaphors conveyed by gesture with/without metaphoric speech. In her work, she discussed the grounding of conceptual metaphor in embodied experience and the aspect of metaphoric thinking which reveals people’s focus of attention in real-time conversation..

(21) 6. Previous studies on metaphors in language and gesture have provided abundant insights and visible evidence to the realization and the embodiment of conceptual metaphor; however, most of them only take account of qualitative analysis. In addition, many studies investigate metaphoric expressions in a single modality. Even though some studies pay attention to metaphoric expressions in both language and gesture, how the two modalities interact in presenting metaphoric concepts still needs further exploration and support. This. 政 治 大. study focuses on (a) the metaphors simultaneously conveyed in speech and gesture and (b). 立. the metaphors presented by gesture alone (i.e., the referents of the metaphors are literally. ‧ 國. 學. presented in language) in order to understand the temporal patterning and the collaboration of. ‧. language and gesture. Meanwhile, the qualitative and quantitative methods are incorporated. Nat. io. sit. y. in the present study on conversational data. The qualitative data can provide dependable. al. er. evidence for the habitual expressions of metaphors, the synchronization between language. n. v i n and gesture, and the collaboration C between modalities. The present study then can h e ntheg two chi U further examine whether there are similarities or differences between the metaphors concurrently presented in language and gesture and the metaphors presented in gesture-only. Finally, there are three hypotheses about the production process of speech and gesture: the Free Imagery Hypothesis, the Lexical Semantic Hypothesis, and the Interface Hypothesis. The first hypothesis maintains that gestures are independent from the content of speech and that gestures are produced before the formulation of speech. The second one suggests that.

(22) 7. gestures are generated from the semantics of lexical items. The third one maintains that the information in gesture originates from the representations based on the on-line interaction of spatial thinking and speaking. Kita and Öyzürek (2003) have conducted research on the cross-linguistic expressions of motion events to look at the three hypotheses. They focused on the informational coordination between iconic gestures and their corresponding lexical affiliates. Likewise, the present study investigates the relationship between language and. 政 治 大. gesture, but we will discuss the hypotheses from the perspective of metaphorical expressions.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 1.2 The Current Study. The purpose of the thesis is to discuss: (i) people’s habitual expressions of metaphors to. ‧. conceptualize concepts in daily communication, and (ii) the collaboration of language and. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. gesture in expressing metaphors with regard to the hypothesis of speech-gesture production.. i n U. v. Concerning people’s habitual expressions of metaphors, five questions are addressed. What. Ch. engchi. are the metaphor types people usually convey in daily communication? What are the source and target domains of the metaphors? What sources can be used to conceptualize multiple targets? What targets can be realized by multiple sources? Do the metaphors concurrently occurring in language and gesture and the metaphors occurring in gesture exclusively express similar or different. metaphor types, source/target domains, and source-to-target. correspondences? To discuss the cooperation between language and gesture, a question is addressed. What is the temporal patterning of speech and gesture in presenting metaphors?.

(23) 8. The thesis is organized in the following order. Chapter 2 reviews previous studies concerning the issues about conceptual metaphor and the theoretical hypotheses about speech and gesture production. Chapter 3 introduces the data used in this study and the methodology adopted to examine the metaphoric expressions. Chapter 4 reports the analysis of the cross-modal manifestation of metaphors. Chapter 5 shows the general discussion and compares the present study with the previous research. Chapter 6 is a conclusion of the thesis.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(24) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. The thought that metaphor is not restricted to the realm of literature has been widely accepted since Lakoff and Johnson’s study of conceptual metaphor in 1980. After that, a large number of studies on metaphor in language as well as metaphor in gesture provide evidence. 政 治 大. to support the conceptual and embodied view of metaphor. This chapter contains three main. 立. sections. In Section 2.1, the notion of conceptual metaphor proposed by Lakoff and Johnson. ‧ 國. 學. and the past studies on the metaphoric expressions in language are discussed. In Section 2.2,. ‧. the previous studies on the gestural manifestations of conceptual metaphors are reviewed. In. Nat. io. sit. y. Section 2.3, three theoretical hypotheses concerning the cognitive process underlying speech. n. al. er. and gesture production are introduced. Section 2.4 is the summary.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2.1 Conceptual Metaphor in Language. In Lakoff and Johnson’s framework, the word metaphor refers to the “metaphorical concept” in thought and is presented in a form with small capital letters, for example, LOVE IS A JOURNEY (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c: 6). The term metaphorical expression refers to the. surface manifestation of a metaphorical concept. Language is an essential modality for us to understand the metaphors. Although we are not normally aware of our conceptual system, we can explore the system by studying language, since communication shares the same system. 9.

(25) 10. we use in thinking (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c). In addition, metaphor is central to our ordinary language semantics due to the fact that everyday abstract concepts like time, state, and change can be metaphorical (Lakoff 1993). The research on the metaphoric expressions in language provides a way for us to look at what conceptual metaphor is like. An overview of conceptual metaphor is presented in Section 2.1.1. Studies on metaphors in language which allow us to see the nature of conceptual metaphor are reviewed in Section 2.1.2. The studies. 政 治 大. on the embodiment of conceptual metaphor are discussed in Section 2.1.3.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 2.1.1 Overview of Conceptual Metaphor. According to Lakoff and Johnson, “[t]he essence of metaphor is understanding and. ‧. experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another” (1980a: 455, 1980c: 5). Namely,. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. metaphor can be conceived as a conceptual mapping from one domain to another domain. i n U. v. (Lakoff 1993). The conceptual domain used to understand another domain is called source. Ch. engchi. domain. The conceptual domain that is comprehended is called target domain. The source domain is typically concrete, physical, and delineated; on the contrary, the target domain is typically abstract, non-physical, and less delineated (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c). For example, JOURNEY is the more concrete source domain and LOVE is the more abstract target domain in. the metaphor LOVE IS A JOURNEY. There are also instances that concrete ideas can be understood in terms of metaphors, such as LAND AREAS ARE CONTAINERS (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c: 29) and INANIMATE OBJECTS ARE PEOPLE (Kövecses 2002: 58). A.

(26) 11. metaphor—a conceptual mapping—is a set of correspondences (Lakoff 1993). When we refer to LOVE IS A JOURNEY, the mapping covers a set of correspondences: the lovers correspond to the travelers, the lovers’ goal to the destination of the journey, and so on. Metaphorical correspondences obey the Invariance Principle that “[m]etaphorical mappings preserve the cognitive topology (that is, the image-schema structure) of the source domain, in a way consistent with the inherent structure of the target domain” (Lakoff 1993: 215). The inference. 政 治 大. pattern of a target follows the inference pattern of a source.. 立. There are four false views of metaphor: metaphor is a rhetorical device—a matter of. ‧ 國. 學. language; metaphor is based on similarity; all concepts are literal not metaphorical; and. ‧. concepts are disembodied (Lakoff 1993; Lakoff & Johnson 2003). Lakoff and Johnson’s. Nat. io. sit. y. Conceptual Metaphor Theory argues against these views. First, metaphor is in thoughts not in. al. er. language. Conceptual metaphors can be realized in both linguistic and non-linguistic ways. n. v i n C gestures, such as cartoons, rituals, sculptures, so on. The cultural ritual that a baby is h e n gand chi U carried upstairs to pray for success manifests the metaphor STATUS IS UP (Lakoff 1993: 241-242). The sculptures of oversized heroes manifest the metaphor SIGNIFICANT IS BIG (Kövecses 2002: 58). The locus of metaphor is not in language but thought, which indicates that metaphors can be conveyed by the modalities other than linguistic expressions. Second, metaphor is typically based on source-to-target correlations in our experience not inherent similarities. For instance, the metaphor MORE IS UP is grounded in the experience that adding.

(27) 12. more water into a container will lead to the water level rising. The event of adding more water is not similar to the event of the water level raising. Moreover, a metaphor may be based on “perceived structural similarity” (Kövecses 2002: 71). For example, the source of the metaphor LIFE IS A PLAY is not inherently like its target, yet we still perceive some similarities between the LIFE and the PLAY. The relationship between a role and his/her performing ways in a play is similar to the relationship between a person and his/her action in. 政 治 大. real life. It is the use of a metaphor that creates perceived similarities (Lakoff & Johnson. 立. 2003). Third, metaphor is indispensable in our conceptualization of the world. Even the. ‧ 國. 學. mundane concepts like TIME, QUANTITY, and STATE are understood via metaphors. Since. ‧. most our everyday concepts to define our world are metaphorical, how we think and what we. Nat. io. sit. y. do would be associated with metaphors (Lakoff & Johnson 1980a, 1980c). Fourth, conceptual. al. er. metaphor can be shaped by our body experiences. For example, the metaphor ANGER IS. n. v i n HEAT is grounded in the experienceC that a person feels hot he n g c h i Uwhen he/she is angry. In addition, there are metaphors which depend on our social and cultural practice (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c, 2003). VIRTUE IS UP is a metaphor with social and culture basis because virtue is the standard embedded in the culture and set by the society. To sum up, metaphor is the conceptual correspondence between two domains in the way that the logic of a source is used to understand the inference of a target. The Conceptual Metaphor Theory maintains four significant views about metaphors: metaphor is in thoughts;.

(28) 13. metaphor is based on the correlations or the structural similarity between two domains; metaphor helps to structure our ordinary conceptual system; and metaphor can be grounded in the body or socio-cultural experiences.. 2.1.2 The Nature of Metaphor In this session, we will focus on the nature of conceptual metaphor through its manifestation in linguistic modality. The partial characteristic of conceptual metaphor is. 治 政 discussed first. The target domain of a metaphor is normally 大 more abstract, and the source 立 ‧ 國. 學. domain of a metaphor is usually more concrete. Most of the time, a single abstract concept is not completely or exactly defined by a single concrete concept. Lakoff and Johnson (1980b). ‧. suggested that an abstract concept is normally understood in terms of more than one concrete. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. concept. A cluster of metaphors are used to understand an abstract concept, and each. i n U. v. metaphor partially defines the concept. For instance, the focuses are different in the following. Ch. engchi. two expressions: Life is empty for him (Lakoff & Johnson 1980c: 51) and He’s holding all the aces (ibid.). In the former expression, life is comprehended as a container, and the emphasis is on the content of life. In the latter one, life is understood in terms of a gambling game, and we pay attention to how people live rather than what is in life. These examples denote that “abstract concepts are not defined by necessary and sufficient conditions” (Lakoff & Johnson 1980b: 200). The partial nature of metaphor shows that a concept may be reasoned in terms of different sources which profile different sematic aspects. Based on this notion, the present.

(29) 14. study examines what the targets are that people tend to conceptualize through various sources. Next, we will focus on the direction of metaphorical correspondences. Kövecses’s (2002) finding supports the notion that metaphorical correspondences usually go from the more concrete and delineated domains to the abstract and less delineated domains. He collected the linguistic expressions of metaphors in dictionaries (e.g., Cobuild Metaphor. 政 治 大. Dictionary) to survey the common sources and targets in his qualitative study. The frequent. 立. sources given by him are arranged in Table 1.. ‧ 國. 學. Table 1. Common source domains of metaphorical expressions in English (Kövecses 2002: 16-20). n. Ch. sit. y. Example the heart of the problem a healthy society He is a donkey. the fruit of her labor She constructed a theory. conceptual tools He tried to checkmate her. Spend your time wisely. What’s your recipe for success? a warm welcome She brightened up. I was overwhelmed. He went crazy.. er. io. al. ‧. Nat. Source The human body Health and illness Animals Plants Buildings and construction Machines and tools Games and sports Money and economic transactions (business) Cooking and food Heat and cold Light and Darkness Forces Movement and direction. engchi. i n U. v. These sources are concrete in general, and they are what we are familiar with. Kövecses also mentioned that basic entities and the properties of the entities are common source domains as well. The sources suggest that metaphor is grounded in our bodily experience or socio-cultural practices. For instance, heat/cold and light/darkness associate.

(30) 15. with our perceptual experience. Forces and movement relate to our motor experiences. Games and commercial activities are the socio-cultural practice we perform in everyday life.. Table 2. Common target domains of metaphorical expressions in English (Kövecses 2002: 21-24). 立. Example He was bursting with joy. She is hungry for knowledge. that was a lowly thing to do I see your point. What do we owe society? the president plays hardball the growth of the economy the built a strong marriage That’s a dense paragraph. Time flies. Grandpa is gone. She has reached her goals in life. the God’s sheep (sheep = follower). 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Target Emotion Desire Morality Thought Society/ Nation Politics Economy Human relations Communication Time Life and death Events and action Religion. The common targets given by Kövecses are arranged in Table 2. He roughly classified. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. the most frequent targets into psychological states and events (emotion, desire, morality, and. i n U. v. thought), social groups and process (society, nation, politics, economy, human relationship,. Ch. engchi. and communication), and personal experiences and events (time, life, death, and religion). Compared to the frequent sources, these targets are more abstract and less delineated. We may say the healthiness/illness of the society, yet we do not commonly talk about the society of healthiness/illness. Kövecses then concluded that metaphors are normally unidirectional; that is, the corresponding direction between the sources and targets is asymmetry. Furthermore, some metaphors are universal. Expressions in Chinese are compared with expressions in English in several qualitative studies on metaphors in Chinese (including.

(31) 16. Mandarin and Southern Min). In Yu’s (1998) study, metaphors in Mandarin were collected from dictionaries to compare with the expressions of emotion metaphors, time as space metaphors, and event structure metaphors in English. Lin (2003) obtained data from dictionaries and compared the body-part metaphor in Southern Min with the ones in Mandarin and English. Lai (2011) used data in pop songs to explore the sources for the metaphor about LOVE in Southern Min. Metaphoric expressions of love in Southern Min,. 政 治 大. Mandarin, and English are compared in her study. She also found that multiple source. 立. domains (e.g., FOOD, PLANT, and GAMBLING) map to the target-domain concept of LOVE.. ‧ 國. 學. The above studies investigated metaphors from cross-language perspective, and it was found. ‧. some metaphors are universal and some are culture specific. In Wang’s (2010) quantitative. Nat. io. sit. y. study, he gathered data from pop songs to examine love metaphors in Mandarin. He also. al. er. found love can be realized by different types of metaphor. Results show that the event. n. v i n C hmetaphor are the most structure metaphor and the ontological e n g c h i U frequent types of metaphors to express LOVE. Kövecses’s (2002) study in English supported that source domains are more concrete, that target domains are more abstract, and that the corresponding direction is asymmetrical. The cross-linguistic research (Yu 1998; Lin 2003; Lai 2011) revealed there are some universal metaphors shared by different cultures. Wang’s (2010) and Lai’s (2011) investigations on love metaphors provided evidence for the notion that an abstract concept.

(32) 17. can be defined by different metaphors which highlight different semantic elements of the concept. The findings also showed that a single target-domain concept can map to multiple sources. Except for Wang’s study of LOVE metaphor, all the studies mentioned above only employ qualitative analysis. The present study attempts to analyze the data in both quantitative and qualitative ways to gain dependable information about the habitual expressions of metaphors and the correspondences between the two domains.. 治 政 2.1.3 The Embodiment of Metaphor 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. Embodied cognition holds the view that cognition is rooted in the body’s interaction with the world (Wilson 2002; Gibbs 2005). Such view rejects that “cognition is computation. ‧. on amodal symbols in a modular system” but proposes that cognition is grounded in. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. simulations, situated action, and, bodily states (Barsalou 2008: 617). With regard to language. i n U. v. comprehension, empirical evidence demonstrates that language is grounded in bodily action.. Ch. engchi. In Glanberg and Kaschak’s (2002) study, participants decided whether a sentence is sensible after reading a sentence of which the implied direction was manipulated (e.g., open the drawer implies action toward body). Results revealed that bodily action can facilitate or interfere with our understanding of a sentence. Hauk et al. (2004) used event related fMRI to record brain activity in a passive reading task. It was found words referring to actions of different body-parts would activate different brain areas which may be activated by actual movement of the tongue, fingers, or feet. The findings implied that the meaning of action.

(33) 18. words correlate with the physical body action. According to the Conceptual Metaphor Theory, “which metaphors we have and what they mean depend on the nature of our bodies, our interactions in the physical environment, and our social and cultural practices” (Lakoff & Johnson 2003: 247). Metaphoric expression in language also provides evidence for the embodied cognition. Johnson (1987) and Lakoff (1987) introduced the notion of “image schema” to. 政 治 大. metaphorical projection. An image schema is “a recurring dynamic pattern of our perceptual. 立. interactions and motor programs that gives coherence and structure to our experience”. ‧ 國. 學. (Johnson 1987: xiv) and following is a more specific definition of image schemata:. ‧. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. [T]hey are not Objectivist propositions that specify abstract relations between symbols and objective reality...they do not have the specificity of rich images or mental pictures... A schema consists of a small number of parts and relations, by virtue of which it can structure indefinitely many perceptions, images, and events. In sum, image schemata operate at a level of mental organization that falls between abstract propositional structures, on the one side, and particular concrete images, on the other” (Johnson 1987: 28-29). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Image schemas are studied as the embodied bases for metaphoric extensions in past research (Johnson 1987; Lakoff 1987, 1993; Lakoff & Johnson 1999; Kövecses 2002; Gibbs 2005, 2006; Johnson 2007). Three important aspects of image schema relate to the grounding of meaning (Johnson 2005: 21-22, 2007: 139). First, image schema is part of the thing that makes bodily experience to have meaning for us. Second, image-schematic structure has a logic which makes it possible for us to make sense of our everyday experiences. Third, image.

(34) 19. schema is not merely mental or merely bodily, but a contour of body-mind. Johnson (1987) proposed a selective list of image schemas which he thought to be the more important image schemas (see Table 3). It should be noted that “the image schema list has never constituted a closed set” (Hampe 2005: 2). If one defines schema more loosely than Johnson does, it is possible to extend the list. 2 Nevertheless, the core of the standard inventory of image schemas is on the basis of Johnson’s list of schemata and many of the image schemas offered. 政 治 大. by Johnson are frequently discussed in other studies.. 立. Table 3. Image schemas proposed by Johnson (1987: 126). PART-WHOLE FULL-EMPTY. MASS-COUNT. LINK. CENTER-PERIPHERY. NEAR-FAR. SCALE. MERGING. SPLITTING. MATCHING. SUPERIMPOSITION. y. CONTACT. al. PROCESS. n. SURFACE. io. ITERATION. Nat. CYCLE. RESTRAINT REMOVAL. ATTRACTION. sit. PATH. COMPLUSION. COUNTERFORCE. er. ENABLEMENT. BALANCE. OBJECT. Ch. ‧. BLOCKAGE. ‧ 國. CONTAINER. 學. Image Schema. v ni. COLLECTION. engchi U. The metaphor MORE IS UP is an instance based on the SCALE schema which is grounded in the experience that when we add more water into a container, the water level rises. Such an image-schematic based metaphor is treated as a member of the “primary metaphor” category, which shows a straightforward correlation to our ordinary embodied experience (Lakoff & Johnson 1999; Gibbs 2005, 2006). Unlike primary metaphor,. 2. Some image schemas were not included in Johnson’s list: FRONT-BACK (Lakoff 1987), UP-DOWN (Lakoff 1987), (Mandler 1992), LEFT-RIGHT (Krzeszowski 1993; Clausner & Croft 1999), FORCE (Cienki 1997; Clausner & Croft 1999), IN-OUT (Clausner & Croft 1999), and SPACE (Clausner & Croft 1999). SELF MOTION.

(35) 20. “compound” or “complex” metaphor does not suggest a direct experiential basis (Lakoff and Johnson 1999; Gibbs 2005, 2006). The complex metaphor A PURPOSEFUL LIFE IS A JOURNEY does not directly relate to the image schema but it is still embodied. This metaphor. is built up by the primary metaphors (PURPOSE ARE DESTINATIONS and ACTIONS ARE MOTIONS) and the cultural knowledge that people are believed to have purposes in life and to. act to achieve the purposes (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 60-61).. 政 治 大. Empirical evidence also reveals that people’s understanding of metaphorical language. 立. is based on non-linguistic experience. In the experiment made by Gibbs et al. (1997), people. ‧ 國. 學. made lexical decisions to letter-strings related to metaphor (e.g. heat) faster after they read. ‧. the idioms (e.g., blew his stack) with metaphorical implications. The result showed that. Nat. io. sit. y. people could compute embodied representations as soon as they understand the idioms with. al. er. metaphorical meaning. Research made by Gibbs et al. (2004) investigated people’s. n. v i n interpretation of metaphors realizedC inhlanguage (based on e n g c h i UDESIRE IS HUNGER) about human desires. Their research tests participants’ acceptability of different linguistic expressions of desire. Results implied that embodied knowledge could be the primary source of metaphorical meaning and understanding. In Wilson and Gibbs’s (2007) experiment, people’s reaction time for comprehending the metaphors was faster in the matching prime condition when they practiced or imagined the priming actions which relate to the metaphors. The results demonstrated that real and imagined body movements associated with metaphorical.

(36) 21. phrases can facilitate people’s immediate comprehension of the metaphors.. 2.2 Conceptual Metaphor in Gesture So far, we have discussed the studies on linguistic expressions of metaphors. However, some scholars suspect that the language-based analysis can directly reflect the pattern of our thought (Murphy 1996, 1997; Glucksberg 2001). It is suggested that evidence from different aspects other than language is needed for the discussion about metaphor. Gestural studies. 治 政 may help to enhance the cognitive reality of metaphors.大 Since metaphors are conceptual, 立 ‧ 國. 學. language is not the exclusive realization of metaphors. Gesture is regarded as an independent non-verbal modality where we may find the metaphorical expressions (Cienki 2008; Cienki. ‧. & Müller 2008; Müller 2008; Gibbs 2008b). In McNeill’s Hand and Mind, he declared:. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. Gestures are like thoughts themselves. They belong, not to the outside world, but to the inside one of memory, thought, and mental images. Gesture images are complex, intricately interconnected, and not at all like photographs. Gestures open up a wholly new way of regarding thought process, language, and the interaction of people (McNeill 1992: 12).. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Likewise, Cienki (2008) claims that spontaneous gestures are produced unconsciously while speaking and that they can provide insight into thought formulation. According to McNeill (1992: 14), metaphoric gestures are “like iconic gestures in that they are pictorial, but the pictorial content presents an abstract idea rather than a concrete object or event...[and] presents an image of the invisible—an image of an abstraction”. The imagery presented by a metaphoric gesture serves as the source domain, and the abstract concept which the imagery.

(37) 22. conveys is the target domain. The research on gestures can provide insight for the issue about metaphor. Metaphoric gestures do not merely duplicate what we find in metaphors conveyed in language; they may profile different aspects of metaphorical concepts (Cienki 2008; Cienki & Müller 2008). For instance, the temporal ordering may be realized via the metaphors with different spatial orientations. In European languages, the future is thought to be located ahead of us and the. 政 治 大. past event comes to us before the future event (Cienki 2008). We may say I did X before Y. 立. where X is the past event, yet it is unusual to say I did X to the left of Y to mean the same idea.. ‧ 國. 學. However, Calbris (2008: 43) found a gestural data that the order of time is metaphorically. ‧. expressed via the left-right orientation. In the example offered by Calbris, the speaker’s left. Nat. io. sit. y. index finger moves to the left to present the metaphor PAST IS LEFT; his right index finger. er. moves to the right to realize the metaphor FUTURE IS RIGHT. Although the metaphors based. al. n. v i n on left-right orientation are rare in C linguistic the gestural data can provide evidence for h e ndata, gchi U the cognitive reality for the metaphors PAST IS LEFT and FUTURE IS RIGHT. The case. suggests. that. gestures. can. provide. additional. evidence. of. the. source-to-target. correspondences. Gesture is not only an important modality to reflect our thought but also an independent source to reinforce the psychological reality of conceptual metaphors. Müller (2008) examined data taken from narrative interviews and conversations and finds that.

(38) 23. metaphor is presented in linguistic and gestural modalities at the same time. The finding supports the view that metaphor is not a phenomenon of language. He also observed that metaphors are not just single lexical terms or idioms. Gestural data shows that a metaphor can persist over longer pieces of discourse and supports the assumption that a metaphor can be the product of the general cognitive process structuring an entire argument. Spontaneous gesture is “[a]nother important form of embodiment in language”. 政 治 大. (Barsalou 2008: 629). In the past research on language, image schema has been studied as the. 立. embodied source of metaphors. With regard to the gestural modality, Cienki’s (2005). ‧ 國. 學. investigation proves that image schema could be used reliably to characterize co-speech. ‧. gesture. In his experiment, participants watch videos clips showing a person making hand. Nat. io. sit. y. gestures with or without sound. After watching each clip, they need to choose an appropriate. al. er. description for the hand movement by circling a word from a given list which contains. n. v i n several terms of image schema andCthe Results show that the category of other h term e n other. gchi U. was seldom used. Although each stimulus provokes a variable response, there is a statistically reliable agreement about what schema would be elicited by each gesture. Despite the idiosyncratic forms of the gestures with the same meaning, most of them shared a basis in our experience. Image schemas might provide common patterns underlying idiosyncratic gestures (Cienki 2005). Furthermore, image schema is proposed to be one of the iconic symbols that build the foundation for metaphoric projections in gesture by Mittelberg (2008). In her.

(39) 24. research, semiotic theory and conceptual metaphor theory are combined in the analysis of the lectures by linguistic professors. Gestural expressions help us explore the embodied nature of conceptual metaphor. At the same time, metaphoric gestures offer visible evidence for how metaphors are grounded in non-metaphoric embodied patterns. Núñez (2008) examined the lectures by mathematicians to look at the foundation of mathematics. He analyzes the mathematical expressions to. 政 治 大. discuss pure mathematical ideas such as approaching limits and oscillating function. The. 立. expressions are used to describe facts about numbers or the result of the operations with. ‧ 國. 學. numbers, and there is nothing really moving. For instance, Núñez observed that a professor. ‧. moves his right hand back and forth horizontally while he uttered still oscillate (2008: 108).. Nat. io. sit. y. The linguistic expressions about mathematics may be accompanied with spontaneous. al. er. gestures depicting the fictive motions for the static numbers. Therefore, Núñez claimed that. n. v i n C h are not simplyUdead metaphors. He also concludes metaphoric expressions about mathematics engchi that mathematics, the most abstract concept, is ultimately grounded in the human body. There are studies on the metaphoric gestures in the conversation in Chinese as well. In Chui’s (2011, 2013) studies on Chinese discourse, she maintained that gesture can provide visible evidence for the presence of source domains in metaphorical correspondences. She also claimed that many metaphors in language are substantiated by metaphoric gestures. The manifestations of metaphors in the use of hand gesture demonstrate that metaphorical.

(40) 25. expressions are not lexicalized. The bodily experiences can affect the performance of metaphors in gesture, revealing that “even the most clichéd metaphoric phrases are not understood through simple retrieval of their meanings stored in a phrasal, mental lexicon” (Gibbs 2008a: 295). Furthermore, Chui (2011) found that gestures may provide additional information about which aspect of the concept gains a speaker’s focus of attention in real-time communication. The metaphor TIME IS SPACE can be realized in different spatial. 政 治 大. orientations which conveys different viewpoints. For instance, PAST is gestured forward with. 立. time-moving perspective and backward with an ego-moving perspective at different moments. ‧ 國. 學. of speaking. In general, “gestures make knowledge and the situated-dynamic aspect of. ‧. cognition visible” (Chui 2013: 61).. Nat. io. sit. y. Previous research on metaphors in gesture has provided considerable empirical. al. er. evidence for the reality of metaphorical thinking and the embodiment of metaphor in body. n. v i n C h Different kinds ofUgestural expressions of metaphors experiences and socio-culture practices. engchi can be found in these studies as well. However, the past studies in gesture merely adopt qualitative analysis. To discuss the habitual expressions of different metaphor types as well as. the source and target domains in metaphorical correspondences, the present study would like to apply quantitative analysis in the investigation of metaphors in gesture in conversations. The present study is then able to have reliable evidence from the quantitative data to compare the metaphors in language and gesture and the metaphors in gesture-only..

(41) 26. 2.3 Theoretical Hypotheses of Gesture Production The study on the collaboration of language and gesture in expressing metaphor may lead us to understand the cognitive process of speech and gesture production. In this section, three hypotheses about the process of the coordination of speech and gesture in conveying information are introduced: the Free Imagery Hypothesis, the Lexical Semantic Hypothesis, and the Interface Hypothesis. These hypotheses disagree with one another in whether the. 政 治 大. formulation of speech influences gesture production. In the following sub-sections, each. 立. hypothesis is discussed.. ‧ 國. 學. 2.3.1 The Free Imagery Hypothesis. ‧. Some scholars (Krauss et al. 1996, 2000; de Ruiter 2000) stand for the Free Imagery. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Hypothesis which maintains the view that gestures are generated independently before the. i n U. v. processes of speech formulation take place. Based on Levelt’s (1989) speech production. Ch. engchi. model, Krauss et al. (1996, 2000) proposed a model which is capable of generating both speech and gesture. In Levelt’s (1989: 9-13) speech production model, three stages are distinguished: “conceptualizing”, “formulating”, and “articulating”. At the conceptualizing stage, propositional knowledge is drawn to construct the communicative intention. The “Conceptualizer” serves to transform the communicative intention into a “preverbal message”, a conceptual structure which is the input of the “Formulator”. At the formulating stage, the preverbal message is translated into a linguistic structure. At the articulating stage, an overt.

(42) 27. speech is produced by the “Articulator”. Krauss and colleagues (1996, 2000) suggested that the knowledge in working memory can be encoded in both propositional and non-propositional formats and that speech and lexical gestures involve two production systems operating. In their model, propositional formats are managed by the conceptualizer, the formulator, and the articulator. The non-propositional formats in working memory are the origins of the gestures (Krauss et al.. 政 治 大. 1996: 24). A “spatial/dynamic feature selector” transforms the non-propositional. 立. representations into the abstract “spatial/dynamic specifications” which are translated by a. ‧ 國. 學. “motor planner” into a “motor program”. The motor program then provides the motor system. ‧. Nat. io. sit. before speech formulation takes place.. y. with instructions for performing the overt gestures. In their model, gestures are produced. al. er. De Ruiter (2000) proposed another model of speech-gesture production, the Sketch. n. v i n C h as well. UnlikeUKrauss and his colleagues’ model, Model, which is built on Levelt’s model engchi. the Sketch Model suggests that gestures are managed by the conceptualizer which also processes speech. At the conceptualizing stage, the communicative intention is split into a propositional part which is transformed into a preverbal message and an imagistic part is transformed into a “sketch” (de Ruiter 2000: 292). After the conceptualizing stage, gesture and speech are processed independently. The sketch with relevant information will be sent to the “gesture planner”. The gesture planner then builds a motor program for the motor-control.

(43) 28. modules for executing the overt gestures. According to de Ruiter (2000: 299), “although the preverbal message and the sketch are constructed simultaneously, the preverbal message is sent to the formulator only after the gesture planner has finished constructing a motor program and is about to send it to the motor-execution unit.” The models proposed by Krauss and his colleagues and by de Ruiter are similar in that gestures are generated before speech formulation takes place. The Free Imagery Hypothesis, hence, implies that gesture and speech. 政 治 大. are processed independently and predicts that the information expressed in gesture will not be. 立. influenced by the information encoded in speech.. ‧ 國. 學. 2.3.2 The Lexical Semantics Hypothesis. ‧. Studies (Schegloff 1984; Butterworth & Hadar 1989) sustaining the Lexical Semantics. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Hypothesis suggest that gestures are produced from the information encoded in the affiliated. i n U. v. lexical items of the accompanying speech. Such a view was originally proposed by Schegloff. Ch. engchi. (1984: 273), who claimed that “hand gestures are organized...by reference to the talk...[and] various aspects of the talk appear to be the ‘source’ for gestures affiliated to them”. Butterworth and Hadar (1989) proposed that lexical items generate iconic gestures through the semantic features (e.g., forms, directions, and measures) that can be reflected in the configurative properties of the gesture, such as (e.g., force, trajectory, and speed). Such a view indicates that the features of lexical items are the sources of iconic gestures. They suggest gesture typically reflects only part of the meaning, which is opposed to McNeill’s.

(44) 29. (1985) claim that the meaning of gesture is holistic and synthetic. Moreover, it was proposed that “speech production processes dominate gesture production so that the latter must conform to speech productive constraints” (Butterworth & Hadar 1989: 172). Iconic gestures are thought to be generated from the result of the computational stage of the selecting of the lexical items. Differing from McNeill's (1985) account, Butterworth and Hadar’s claim places the origins of iconic gestures after linguistic. 政 治 大. construction rather than with it. The Lexical Semantics Hypothesis implies that the. 立. information expressed in gesture will be influenced by the content of the speech. Namely,. ‧ 國. 學. representational gestures only encode information which is encoded in affiliated lexical items.. ‧. What is not expressed in the accompanying speech will not be encoded in gesture.. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. 2.3.3 The Interface Hypothesis. i n U. v. The Interface Hypothesis was proposed in Kita and Öyzürek’s (2003) cross-language. Ch. engchi. study in the informational coordination between speech and gesture. Their study suggested that gestures are generated from “an interface representation between speaking and spatial thinking” (Kita & Öyzürek 2003: 17). Such interface representation is the spatio-motoric representation including the spatial and action information which is organized for speaking. The Interface Hypothesis maintains that gestures encode non-linguistic and spatio-motoric properties of their referents and structure the information about the referents “in the way that is relatively compatible with linguistic encoding possibilities” (Kita & Öyzürek 2003: 17)..

(45) 30. Kita and Öyzürek’s hypothesis follows Slobin’s (1987, 1996) “thinking for speaking” and McNeill’s (1992) Growth Point Theory of utterance generation. Thinking-for- speaking means that thinking is carried out on-line during speaking; it involves “picking those characteristics of objects and events that (a) fit some conceptualization of the event, and (b) are readily encodable in the language” (Slobin 1987: 435). Hence, the information organized for producing speech in a certain language is decided by “interaction between. 政 治 大. representational resources of the language and processing requirement for the speech. 立. production system” (Kita & Öyzürek 2003: 17). For instance, a certain concept may parallel. ‧ 國. 學. an accessible specific expression in one language but not in another. Such linguistic. ‧. difference is thought to be visible in co-speech gestures according to the Growth Point. Nat. io. sit. y. Theory in which the organization of speech involves the interaction of imagistic thinking and. al. er. linguistic thinking. The growth point refers to the speaker’s minimal idea unit which can. n. v i n develop into a full utterance with C gesture, of image and linguistic U h e nandg itc ish ai combination meaning (McNeill 1992). There is a mutual influence between image and language; furthermore, image and language are not the translation of each other (McNeill & Duncan 2000). From this perspective, image and language are equal to thinking-for-speaking. Based on these arguments, the Interface Hypothesis claims that the imagery underlying a gesture is shaped by the formulation of language as well as the spatio-motoric properties of the referent which may not be expressed in language (Kita & Öyzürek 2003: 18)..

(46) 31. Kita and Öyzürek further proposed a speech and gesture production model which builds on Levelt’s (1989) speech production model, with some modifications. In their model, Levelt’s Conceptualizer is split into two parts: the Communication Planner and the Message Generator. The Communication Planner generates communicative intention and decides which modalities of expression to be involved. Once the communicative intention is generated in the Communication Planner, it is sent to the Message Generator and the Action. 政 治 大. Generator. The Message Generator takes the communicative goal and discourse context into. 立. account, formulating a proposition to be verbally expressed. The gesture, on the other hand, is. ‧ 國. 學. generated from the Action Generator. A spatio-motoric representation produced by the Action. ‧. Generator can be transformed into a propositional format and passed onto the Message. Nat. io. sit. y. Generator. A proposition produced by the Message Generator can be transformed into a. al. er. spatio-motoric format and passed onto the Action Generator as well. The contents generated. n. v i n by the two generators incline to C converge the exchange of information (Kita & h e nthrough gchi U Öyzürek 2003: 29). The message produced by the Message Generator is sent to the Formulator. Before a proposition is readily verbalized, the Message Generator receives direct feedback from the Formulator (Kita & Öyzürek 2003: 29). In the model, the information exchange between the Message Generator and the Action Generator and the interaction between the Formulator and the Message Generator are on-line and bi-directional. Therefore, The content of a gesture is decided by: (a) the communicative intention which does not fully.

數據

相關文件

Promote project learning, mathematical modeling, and problem-based learning to strengthen the ability to integrate and apply knowledge and skills, and make. calculated

Building on the strengths of students and considering their future learning needs, plan for a Junior Secondary English Language curriculum to gear students towards the

Language Curriculum: (I) Reading and Listening Skills (Re-run) 2 30 3 hr 2 Workshop on the Language Arts Modules: Learning English. through Popular Culture (Re-run) 2 30

- Informants: Principal, Vice-principals, curriculum leaders, English teachers, content subject teachers, students, parents.. - 12 cases could be categorised into 3 types, based

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

Define instead the imaginary.. potential, magnetic field, lattice…) Dirac-BdG Hamiltonian:. with small, and matrix

name common laboratory apparatus (e.g., beaker, test tube, test-tube rack, glass rod, dropper, spatula, measuring cylinder, Bunsen burner, tripod, wire gauze and heat-proof

Microphone and 600 ohm line conduits shall be mechanically and electrically connected to receptacle boxes and electrically grounded to the audio system ground point.. Lines in