The impact of publicity and subsequent intervention in

recruitment advertising on job searching freshmen’s

attraction to an organization and job pursuit intention

Chun-Hsien Lee1, Fang-Ming Hwang2, Yu-Chen Yeh31Graduate Institute of Human Resource and Knowledge Management, National Kaohsiung Normal University 2Department of Education, National Chiayi University

3Institute of Education, National Chiao Tung University

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Fang-Ming Hwang, No. 85 Wenlong, Mingsuin, Chiayi Hsien 62103, Taiwan. E-mail: fmh@mail.ncyu.edu.tw doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00975.x

Abstract

This study investigates the impacts of publicity exposure and recruiting advertise-ment sequence on freshmen’s job search attraction to organizations and their job decisions. The current research uses a two-factor experiment design, publicity (posi-tive vs. nega(posi-tive) and recruiting ads (detailed vs. general), and recruits 415 under-graduates (seniors are the majority). Results indicate that negative publicity has greater effect on applicant attraction than positive publicity. The perceived truthful-ness of sequential intervening recruiting advertisement rules the reaction to job ad, then further impacts on organizational attractiveness and job pursuit intention. With negative publicity exposure, higher specificity of recruiting advertisement has more significant mitigation effects than lower specificity. This work discusses impli-cations and directions for future research.

Recent recruitment research has shifted toward studies on potential applicants’ attraction to organizations to assist employers in early recruitment stages. Findings show general impressions or recruitment images to be the critical reasons for organizational attractiveness and strong predictors of job choice decisions. Applicants weigh organization image and corporate reputation in job searching, job pursuit, and final job decision (Cable & Graham, 2000; Gatewood, Gowan, & Lautenschlager, 1993; Lemmink, Schuijf, & Streukens, 2003). Owing to the lack of work experience and public access infor-mation about recruited companies, potential applicants in first-time job seeking may infer employment conditions by relying on testimonials and publicity. Information sources outside of organizations’ direct control such as media press or peer word of mouth can impact job seekers’ attitude and beliefs (Collins & Stevens, 2002). Unlike company-provided information sources, noncompany sources do not always act in organizations’ best interests and might extensively influ-ence applicants’ initial attraction to an organization (Rynes & Cable, 2003). Several studies have focused on company-dependent recruitment sources to communicate positive messages and give good experiences to attract applicants (Breaugh, Macan, & Grambow, 2008; Cable & Turban,

2001). However, research is rare with respect to company-independent sources such as publicity, which are not under company control, but spreads positive as well as negative news (Van Hoye & Lievens, 2005). Understanding informa-tion sources and how recruiting practices affect job pursuit activities of potential applicants is important in terms of applicant contact and organization staffing activities (Van Hoye & Lievens, 2009), because if potential job seekers are absent from the application process, a company cannot reach them through recruitment and selection activities (Carlson, Connerley, & Mecham, 2002). Hence, outside conventional recruitment practices likely influence initial attraction to a company before formal recruitment (Slaughter & Greguras, 2009); thus, it is requisite for applicant motivation to process company-related information and to apply for openings (Chapman, Uggerslev, Carroll, Piasentin, & Jones, 2005). Sources by which potential applicants receive employment information thus have the potential to serve as primary influ-ences on initial attitude toward recruiting companies (Rynes & Cable, 2003; Zottoli & Wanous, 2000).

Publicity and recruiting advertisements are distinct in terms of the degree of control over disseminated information (Cable & Turban, 2001; Wang, 2006). The goals of both are to Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2013, 43, pp. 1–13

create awareness, change attitudes, and influence behavior. Where advertising is perceived as inherently manipulative, publicity is viewed as more trustworthy based on the percep-tion of news media as nonmanipulative and more objective (Cameron, 1994). Positive publicity benefits a company; however, negative information is more diagnostic than posi-tive information and seriously attacks a company (Skowron-ski & Carlston, 1987). The printed press frequently uses job advertisements, which play an important role in exerting organizational attraction (Barber, 1998). Job advertisements containing job or organization information, such as pay levels, benefits, and work location, not only influence initial application decisions, but also partially counter the effects of negative publicity about a company on individuals’ attraction to the organization (Van Hoye & Lievens, 2005). Job seekers receive information, not only from recruitment sources that are primarily under the control of an organization, but also from external sources, which are not under the control of an organization; information from nonrecruitment sources or media press has implications for job seekers’ initial interest in an organization as a place to work and is relevant to employ-ment brand equity and employer knowledge (Cable & Turban, 2001, 2003). However, scant research has investigated the effects of these external information sources integrated with recruitment sources of organizational attractiveness and job pursuit (Collins & Stevens, 2002; Kanar, Collins, & Bell, 2010; Van Hoye & Lievens, 2007).

The present study probes the integrating effects of public-ity and recruiting advertisement sequence received by poten-tial applicants on organizational attractiveness and job pursuit intentions. This research employs four designs of positive publicity and general job ad sequence, positive pub-licity and detailed job ad sequence, negative pubpub-licity and general job ad sequence, and negative publicity and detailed job ad sequence, to investigate the incremental contribution of job advertisement on publicity surrounding a company. First, this study applies the information integration theory (Anderson, 1971) to examine potential job seeker’s percep-tion and attitude toward a recruited company, formed from integrating different pieces of information from publicity communication and recruiting advertisement sequence. Second, this study relies on the accessibility–diagnosticity model (Feldman & Lynch, 1988) to investigate differential influences of a sequential job ad specificity (detailed vs. general) after exposure to positive or negative publicity about an unfamiliar recruiting organization on potential job seek-er’s organizational attraction and job pursuit intention. The current study focuses on new entrants into the labor market; because job seekers lack job-seeking experience, they typi-cally weigh heavily upon external sources or peer information for making a job decision (Collins & Stevens, 2002; Van Hoye & Lievens, 2007). Employing undergraduates as participants in this study addresses this situation.

Publicity and recruiting

advertisement on applicant attraction

Research has recognized publicity as an efficient and credible means of marketing communication, exerting greater influ-ence on perceived credibility and purchase intention than advertising (Loda & Coleman, 2005). The value of publicity is tied to how successfully it generates information for a brand, product, or company across various types of media outlets, including broadcast, print, and trade publications. Research believes that publicity has more credibility than advertising because it emerges from company-dependent sources (Meijer & Kleinnijenhuis, 2007); thus, publicity is likely to influence ones’ attitude toward advertising and brands (Stammerjohan, Wood, Chang, & Thorson, 2005). Publicity information that is negative, as opposed to positive, is more attention getting. Negativity effect is a robust finding in impression formation research; namely, negative framing is more effective than positive framing when people process message content (Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy, 1990). People place more weight on negative than positive information, in forming an overall evaluation of a target (Baumeister, Brat-slavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001; Skowronski & Carlston, 1987, 1989).

The primary objective of recruiting advertisements is attracting the attention of quality applicants. In most cases, recruiting ads represent the first mention of potential employment for an applicant (Barber, 1998; Orlitzky, 2007). In some cases, individuals read job ads for the sole purpose of surveying the employment market. Recruiting advertise-ments serve as forums for organizational self-presentation that offer current information about employment exchanges from an employer’s perspective (Rafaeli & Oliver, 1998). Recruiting advertisements and corporate brands affect job seekers’ perceptions of recruiting companies and influence the specifics of their job pursuits.

Recruitment research notes that publicity is prescreening information in the early stage of hiring and job seekers use early information exposures as signals of unknown company attributes (Kanar et al., 2010). Companies that have name or brand recognition generally attract more applicants, although being familiar and having initially negative views of an organization can have a deleterious effect on recruiting outcomes (Van Hoye & Lievens, 2009). Collins and Stevens (2002) found a positive relationship between publicity and organizational attractiveness, thus strengthening the effect of other recruitment sources; however, they did not examine negative publicity in their study.Van Hoye and Lievens (2005) found that both recruitment advertising and word of mouth mitigated negative publicity effects on organizational attrac-tiveness and job applications. In a later study, Van Hoye and Lievens (2009) reported that negative publicity exerted a destructive effect on organizational attractiveness, while

positive publicity (including by word of mouth) exerted a positive influence on applicant decision making. Research dealing with recruitment advertisements has revealed the benefits of advertisements that include specific information (Mason & Belt, 1986) and additional information (Feldman, Bearden, & Hardesty, 2006; Highhouse, Beadle, Gallo, & Miller, 1998). Highhouse et al. (1998) revealed that job appli-cants can infer certain information from recruiting and phrasing, such as salary ranges, and Lievens and Highhouse (2003) suggested that image-oriented advertising techniques that emphasize a company’s innovativeness, prestige, and sin-cerity can produce additional recruiting benefits. Roberson, Collins, and Oreg (2005) indicated that increased specificity in recruitment messages enhances applicant perceptions of organizational attributes and mediates the relationship between message specificity and pursuit intention. Kanar et al. (2010) noted that job seekers interpret positive and negative information differently and that negative informa-tion has greater influence on job seekers’ organizainforma-tional attraction and recall. Other studies on recruiting sources and message expression have shown that realistic and job-specific information typically provides positive effects on job seeking and job choice. Recruiting advertisements with realistic and specific claims are more likely to create good first impressions (Buckley, Fedor, Veres, Wiese, & Carraher, 1998), arouse posi-tive attitudes toward job openings and recruiting companies (Taylor, 1994), and reduce applicant misperception (Belt & Paolillo, 1982; Mason & Belt, 1986; Werbel & Landau, 1996).

Theory and hypotheses

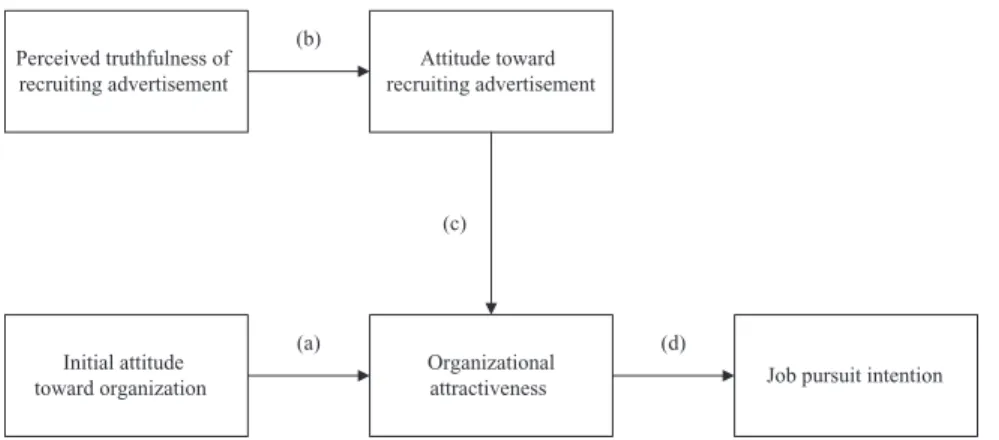

Figure 1 presents a model showing the effects of publicity exposure on initial attitude toward a recruiting organization (first), and the combined effects of a consequent job ad received (sequentially) on organizational attractiveness and job pursuit intention through perceived truthfulness and atti-tude toward the recruiting advertisement. This work first dis-cusses rationales for the relations of the hypothesized model

under the integrated effects of publicity and job ad sequence. Then we discuss the differential influence of publicity valence and job ad specificity on hypothesized linkages.

Information integration theory

Information integration theory assumes that integrating and interpreting different pieces of information, combined with prior attitudes through the valuation and integration process, form and modify attitude. Valuation determines the meaning, importance, and evaluation of information. Inte-gration combines those valued pieces of information (Ander-son, 1971). People integrate each piece of information by adding it to similar information pieces, or by averaging it to a prior set of integrated information when assigning new weights, depending on the weight of information already received. The weight of each information piece relies on its credibility and reliability. The integration theory offers insights into the sequential effect of information stimuli because of inconsistency discounting, indicating that a new piece of information that is inconsistent with an existing information set is assigned a decreased weight (Kim, Yoon, & Lee, 2010). Thus, this study presumes that a potential job seeker will discount the weight of publicity or a job ad if it is inconsistent with information they have already received.

In light of the integration information theory, confirma-tion effect states that nondiagnostic evidence, combined with diagnostic evidence, increases overall evaluation, because people are more sensitive to and gives greater weight to evaluation cues consistent with their currently held beliefs or expectations. Therefore, initial evaluations can become more extreme by introducing either diagnostic or nondiagnostic evidence (LaBella & Koehler, 2004). Thus, the combined effect of publicity and recruiting advertise-ment will be stronger than either publicity-only or recruit-ing advertisement-only condition.

Job seeking encompasses highly involved activities includ-ing job searchinclud-ing, pursuit, and final decision. Potential

Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement Attitude toward recruiting advertisement Initial attitude toward organization Organizational

attractiveness Job pursuit intention (c)

(d) (a)

(b)

applicant reactions to recruiting sources influence how attractive they perceive the recruiting company to be and the enthusiasm with which they pursue job openings (Chapman et al., 2005; Ehrhart & Ziegert, 2005; Turban, 2001). This phase of the current study only draws attention to the hypothesized model and discusses the integration effects of publicity exposure and job ad sequence. According to the information integration theory, publicity carries more weight, but job ads retain their own weight. Hence, the initial attitude toward an organization positively relates to organiza-tional attractiveness, affected by perceived truthfulness of the job ad through attitude toward the job advertisement, leading to applicants’ job pursuit intention.

Hypothesis 1. The initial attitude toward organization with publicity-only exposure will positively relate to organizational attractiveness with publicity and job ad sequence (H1a). The perceived truthfulness of job ad will favor the attitude toward job ad (H1b), and increase organizational attractiveness, affected by pub-licity and job ad collectively (H1c). Finally, organiza-tional attractiveness will positively associate with applicant’s job pursuit intention (H1d).

Job ad is in company’s favor because it is company manipu-lated. The contrast effect also argues that the discrepancy of two distinctive pieces of information will be magnified and distinguishable (Anderson, 1973). The first linkage in Hypothesis 1 is that negative publicity exposure will have greater impact than positive publicity exposure on the hypothesized linkage between initial attitude toward an organization of publicity-only exposure and organizational attractiveness affected by publicity and postjob ad combined.

The accessibility–diagnosticity model

The accessibility–diagnosticity model proposes that a preex-isting attitude, product belief, or earlier response determines a related judgment or behavior as a positive function of its own accessibility and diagnosticity, and as an inverse function of the accessibility and diagnosticity of alternatives (Feldman & Lynch, 1988; Herr, Kardes, & Kim, 1991; Lynch, 2006). Accessibility depends on the relevance of and frequency with which an input is used and the extent to which consumers think about and elaborate on an input. Diagnosticity depends on individual knowledgeability and informativeness, in that information is perceived as diagnostic if it assists in discrimi-nating between interpretations or categorizations (Kardes, 2002). The greater the accessibility and diagnosticity of an input for a judgment relative to alternative inputs, the greater the likelihood that it will be used (Simmons, Bickart, & Lynch, 1993).

Advertisement message concreteness, and specific infor-mation about an advertised target, stands as one of several

influential factors responsible for attracting and holding the receiver’s attention (MacKenzie, Lutz, & Belch, 1986). Less specificity detracts from believability and enhances negative attitudes toward both the message and its source (Snyder, 1989). Less informative messages may be purposefully created to induce attitude misperceptions (Preston, 2002, 2003). Hence, the extent of job ad specificity is as good as the degree of accessibility and diagnosticity of recruiting infor-mation exposure.

The diagnosticity approach argues that negative informa-tion is likely to have a stronger effect on impression than positive information, because negative information is more diagnostic or useful for discriminating between alternative judgments than positive information (Skowronski & Carl-ston, 1989). Negative information is also a salient informa-tion cue to job seekers when forming an attitude toward recruiting organizations (Highhouse & Hoffman, 2001). Job seekers expect to receive positive and negative publicity about recruiting organizations, making positive informa-tion less diagnostic and having less effect on their organiza-tional attraction than negative information (Kanar et al., 2010). Job seekers are also likely to use any negative infor-mation as a simple cue to screen an organization from future consideration.

Publicity induces either facilitative or potential inhibitive effects on advertising campaigns (Jin, 2003; Jin, Zhao, & An, 2006). Kim et al. (2010) noted that the combined effects of positive publicity and advertising produce a higher attitude toward brand than either the advertising-only or publicity-only conditions, regardless of product attitude consistency and exposure sequence; however, the combined effects of negative publicity and advertising provide significant con-trast effects. Negative publicity renders advertisements unfit, especially for moderately informed individuals (Meijer & Kleinnijenhuis, 2007), as negative information is often con-sidered more useful or diagnostic than positive information for making decisions (Ahluwalia, Burnkrant, & Unnava, 2000). Hence, this study expects that job ad specificity has dif-ferent effect on job seekers’ perception and attitude toward the recruiting organization when they receive negative pub-licity exposure rather than positive pubpub-licity exposure.

Hypothesis 2. Recruiting advertisement specificity (detailed vs. general) has different effects on negative publicity exposure compared with positive publicity exposure.

Negative information from sources of a company’s direct control is diagnostic, sending the job seeker a clear signal that the company is not a good place to work. A job ad sequence with higher specificity, covering detailed informa-tion cues, has greater effect on job seekers’ receiving nega-tive publicity, than the lower specificity job ad, covering general information cues only, on the hypothesized linkages

among the theoretical model because the detailed informa-tion is diagnostic. When job seekers receive negative public-ity, the detailed recruiting advertisement provides them more accessible, diagnostic, and sufficient information for making a judgment about the organization, and can end the search for additional information in memory. The effects of these highly informative cues lessen in the presence of nega-tive publicity (Feldman & Lynch, 1988; Herr et al., 1991). Hence, this study expects that greater specificity in a recruit-ing advertisement will mitigate the effects of negative pub-licity on potential applicants’ initial reactions to recruiting organizations.

Hypothesis 3. In the condition of negative publicity in a job ad sequence, higher specificity of a recruiting advertisement (detailed job ad) will have greater effect on applicant attraction than lower specificity of a recruiting advertisement (general job ad).

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were undergraduates majoring in business administration; participation was anonymous, vol-untary, and return for a lagniappe included only students who were attending classes on the day of data collection. Among the 435 questionnaires distributed, 415 question-naires were returned, for a response rate of 95%. Female stu-dents made up 69.4% of the sample, and 85% of participants were juniors and seniors.

Design and procedure

This research used a 2 (negative vs. positive publicity)¥ 2 (detailed vs. general recruiting advertisement) factorial design. Time was treated as a within-subject factor because the focus was on whether publicity-based initial assessments of organizational attraction changed after reading one of two types of recruiting ads. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups, and asked to read either negative or positive publicity about an organization. After 10 minutes, they were asked to describe their initial attitudes toward the organization in question, assess the perceived credibility of the publicity they read, and answer three items designed to assess their understanding of the reading materials.

In the next step, participants were randomly assigned to two new groups, asked to read a detailed or general recruiting advertisement, and then asked to assess their perceptions regarding truthfulness and attitude toward the recruiting advertisement, the attractiveness of the organization respon-sible for the advertisement, and how they would feel about applying for a job with the firm.

For data analysis purposes, participants were classified as ND (reading negative publicity and the detailed recruiting advertisement), NP (reading negative publicity and the general recruiting advertisement), PD (reading positive publicity and the detailed recruiting advertisement), or PG (reading positive publicity and the general recruiting advertisement).

Materials

This study created a fictitious multinational high-tech manu-facturing company named PROCOM, and wrote documents for this company as follows.

Publicity was designed as a business magazine article that reported the fictitious high-tech manufacturing interna-tional company, PROCOM. The content is a scenario descrip-tion of the scope and field of the company, market information about PROCOM announced by professional securities or investment institutions, and future business plans. Specifically, negative publicity was stated as the effects of economic downturn on the exportation recession; hence, the company would experience business reduction and imminent downsizing. Positive publicity was mentioned as rapid market demand increase leading to considerable foreign capital investment; accordingly, the company would adopt business expansion and imperative recruitment. Both descriptions were approximately equal in length and pre-sented parallel neutral attribute information as well, namely location, industry, and size.

Recruiting advertisement was manipulated as a mimic newspaper recruiting advertisement. The specificity of adver-tising was classified into general and detailed in this study. The general recruiting ad covered relatively limited and sketchy information. The detailed recruiting ad comprised the specific company description of the company, job title, job content, and candidate requirements; particularly, it showed the estimated compensation, benefit and health insurance packages, and training and development offerings. The sizes of the two recruiting ads were the same and the layouts were similar to actual recruiting advertisements on newspapers.

To validate the written documents used in this research, we performed a pilot test with 29 undergraduate senior students majoring in business administration (12 male, 17 female; mean age= 22 years). One item, “In general, I think ROCOM is high priced in this article” (rated on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1= completely disagree to 7 = com-pletely agree), was used to assess whether the designed documents could be perceived as distinctive. The results indicated a significant difference between positive (M= 5.75, SD = 1.21) and negative publicity (M = 2.29, SD= 1.1) statistically (t = 9.48, p< .01). As part of the pilot test, perceived publicity credibility was measured using

three items written by Smith and Vogt (1995). Responses were given on a scale of 1 (“completely disagree”) to 7 (“completely agree”). Results from a right-tailed t-test per-formed to examine mean scores that exceeded the scale median indicated that the participants perceived significant credibility for both the positive (M= 4.73, SD = 0.92; t= 7.08, p< .01) and negative (M = 4.58, SD = 0.92; t = 6.12, p< .01) designed publicity documents. The perceived informativeness of the recruiting advertisements was assessed using four items written by Feldman et al. (2006), again using the previously described 7-point response scale. The results indicated that the detailed recruiting ad (M= 5.08, SD = 0.78) presented more information than the general recruiting ad (M= 3.73, SD = 0.76) at a statisti-cally significant level (t= 6.75, p< .01). These results sup-ported the validity of the publicity articles and recruiting ads. The pilot test results indicated that the designed materi-als, publicity article, and recruiting ads are valid in this study.

Measures

Initial attitude toward an organization was measured using four items written by Sicilia, Ruiz, and Reynolds (2006); responses were given along a 7-point semantic differential scale. Participants were asked to respond to these items after reading the positive or negative magazine article, but before reading the general or detailed recruiting ad. Internal consist-ency for this scale was calculated as .81.

Perceived truthfulness of the recruiting advertisement was assessed using four items created by Feldman et al. (2006). Responses were given along a scale ranging from 1 (“com-pletely disagree”) to 7 (“com(“com-pletely agree”). A sample item was, “The recruiting advertisement appears to be truthful.” Internal consistency for this scale was calculated as .76.

Attitude toward the recruiting advertisement used the scale from Feldman et al. (2006). Participants were asked to respond to the question, “Overall, my attitude toward this recruiting advertisement is . . .” on three bipolar and 7-point items, ranging from 1 (bad/unpleasant/unfavorable) to 7 (good/pleasant/favorable). The internal consistency of this scale was .87.

Perceived organizational attractiveness as a potential employer (after reading both the assigned publicity and recruiting advertisement) was measured using five items from Turban and Keon (1993). Responses were collected along a scale ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 7 (“completely agree”). A sample item was, “I would like to work for PROCOM.” Internal consistency was calculated as .87.

Job pursuit intention was assessed using four separate items from Turban and Keon (1993), using the same 7-point response scale as for organizational attractiveness. A sample

item was, “I would exert a great deal of effort to work for this company.” Internal consistency was calculated as .86.

Manipulation checks

Manipulation checks were conducted with the 415 valid participants. For the item, “In general, I think PROCOM is a good company in this article,” participants who read the article with negative publicity gave lower responses (M= 2.60, SD = 1.32, n = 219) compared with those who read the positive publicity (M= 5.83, SD = 0.90, n = 196) at a statistically significant level (t= 29.41, p< .01). According to these results, two publicity articles clearly created each domi-nated perception as designed. Another indication of credibil-ity for the two articles was that participants who read both versions rated them higher than the median scale at statistically significant levels (positive article: M= 4.66, SD= 0.87, n = 196; t = 18.82, p< .01; negative scale: M = 4.59, SD= 0.97, n = 219; t = 16.61, p< .01).Additionally, par-ticipants perceived the detailed recruiting ad as covering more information than the general recruiting ad significantly (F= 28.32, p< .01). Participants in the ND group gave the highest informativeness scores of the four groups to the recruitment ad (M= 4.58, SD = 0.96 versus 4.4 and 0.95 for the PD group, 3.92 and 1.04 for the PG group, and 3.48 and 1.00 for the NG group). According to these combined results, the four documents used in this study were satisfactory in terms of validity.

Results

This research performed confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate the distinctiveness of the measures used in this study. The model fit of a five-factor measurement model (i.e., initial attitude organization, perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement, attitude toward recruiting advertisement, organizational attractiveness, and job pursuit intention) was assessed and revealed a good model fit (c2[160]= 425.375, p= .00; CFI = .976; RMSEA = .062; RMSEA 90% CI = [.055,.070]; SRMR= .049). The next step linked all the meas-ures of the five constructs to one single factor to perform the Harman’s one-factor test. Results of this one-factor model were: c2 (170)= 2,625.548, p = .00, CFI = .849, RMSEA = .185, RMSEA 90% CI= (.179,191), SRMR = .127, which dis-played a poor model fit. We compared this one-factor model with the five-factor model. The significant chi-square change (Dc2(10)= 2,200.173, p< .001) indicated that the respond-ents of this study could distinguish the five constructs well. Drawing upon the widely used Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003), this work interpreted the lack of fit of the single-factor measurement

model as indicating that common method variance was not a serious problem in the data.1

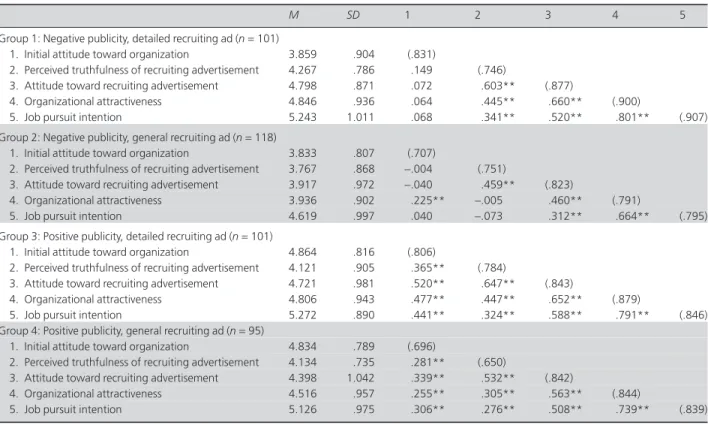

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for the four groups. The results found a statistically signifi-cant association in group 1 and 3 between initial attitude toward organization after exposure to positive publicity, perceived truthfulness of recruiting ads, attitude toward recruiting ads, organizational attractiveness, and job pursuit intention. This study found statistically significant correla-tions among recruiting advertisements, organizational attractiveness, and job pursuit intention.

Participants who read the positive publicity article reported having a better initial attitude toward an organiza-tion (n= 196, M = 4.85, SD = 0.80) than those who read the negative article (n= 219, M = 3.84, SD = .85) significantly (t(413)= 12.34, p< .01). Results from analysis of variance indicated significant differences among the four groups in terms of perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement (F(3, 411)= 7.46, p< .01; Levene c2= .75, p = .52), attitude toward recruiting advertisement (F(3, 411)= 18.99, p< .01;

Levenec2= .34, p = .80), organizational attractiveness (F(3, 411)= 22.64, p< .01; Levene c2= .17, p = .92), and job pursuit intention (F(3, 411)= 11.06, p< .01; Levene c2= .81, p= .49).

This study focused on examining publicity exposure and sequent recruiting advertisement effect. The structural rela-tionships among publicity-induced initial attitude toward organization, perceived truthfulness of subsequent recruiting advertisement, attitude toward the recruiting ad, organiza-tional attractiveness, and job intention can differ due to the manipulation of detailed or general recruiting advertisement after participants read either a positive or negative positive publicity article. In other words, the specificity of recruiting advertisement, detailed or general ad, serves as a moderator on proposed structural relationships. This study tested mod-erating effects by forcing equal path coefficients across levels of recruiting advertisement. If forcing equal path coefficients is not possible, then a moderating effect exists. This study has two baseline models, due to negative and positive publicity experiments.

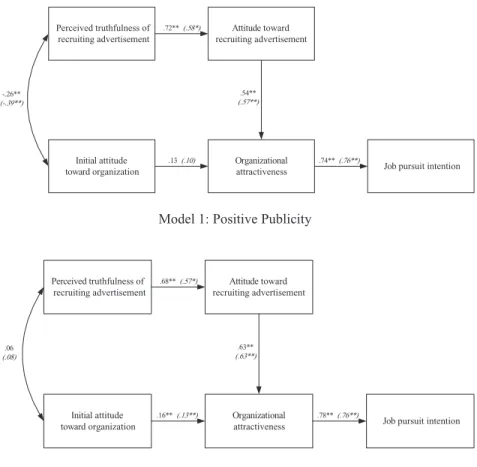

Two baseline models tested the moderating effects with the total sample. Figure 2 presents results for both the positive (PD and PG) and negative (ND and NG) publicity baseline model. The overall fit indices shown in Table 2 reveal well fitting both for the baseline model of positive publi-city (c2

(4)= 8.90, p = .06, RMSEA = 0.079, SRMR = 0.037, 1We also performed Harman’s one-factor test by entering all measurement

items into a principle components analysis and examined the unrotated solu-tion. More than one factor possessing eigenvalue greater than 1.0 emerged, which accounted for 61.52% of variance. The first factor accounted for 38.41% of variance, which showed that the items did not load on a general single factor.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

M SD 1 2 3 4 5

Group 1: Negative publicity, detailed recruiting ad (n= 101)

1. Initial attitude toward organization 3.859 .904 (.831)

2. Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement 4.267 .786 .149 (.746)

3. Attitude toward recruiting advertisement 4.798 .871 .072 .603** (.877)

4. Organizational attractiveness 4.846 .936 .064 .445** .660** (.900)

5. Job pursuit intention 5.243 1.011 .068 .341** .520** .801** (.907)

Group 2: Negative publicity, general recruiting ad (n= 118)

1. Initial attitude toward organization 3.833 .807 (.707)

2. Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement 3.767 .868 -.004 (.751)

3. Attitude toward recruiting advertisement 3.917 .972 -.040 .459** (.823)

4. Organizational attractiveness 3.936 .902 .225** -.005 .460** (.791)

5. Job pursuit intention 4.619 .997 .040 -.073 .312** .664** (.795)

Group 3: Positive publicity, detailed recruiting ad (n= 101)

1. Initial attitude toward organization 4.864 .816 (.806)

2. Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement 4.121 .905 .365** (.784)

3. Attitude toward recruiting advertisement 4.721 .981 .520** .647** (.843)

4. Organizational attractiveness 4.806 .943 .477** .447** .652** (.879)

5. Job pursuit intention 5.272 .890 .441** .324** .588** .791** (.846)

Group 4: Positive publicity, general recruiting ad (n= 95)

1. Initial attitude toward organization 4.834 .789 (.696)

2. Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement 4.134 .735 .281** (.650)

3. Attitude toward recruiting advertisement 4.398 1.042 .339** .532** (.842)

4. Organizational attractiveness 4.516 .957 .255** .305** .563** (.844)

5. Job pursuit intention 5.126 .975 .306** .276** .508** .739** (.839)

GFI= 0.98, CFI = 0.99, c2/df= 2.23) and for the baseline model of negative publicity (c2

(4)= 4.44, p= .34, RMSEA= 0.023, SRMR = 0.030, GFI = 0.99, CFI = 1.00, c2/df= 1.11). The nonstandardized path coefficient from initial attitude toward an organization was significant (g = .16, p< .01) in the negative publicity group, but this path was nonsignificant in the positive publicity group; that is, Hypothesis 1a was only supported in the negative publicity group. This result is consistent with the contrast effect, of a magnified and distinguishable discrepancy of two distinct pieces of information (Anderson, 1973), and that negative publicity exposure will have greater impact than positive publicity exposure on the hypothesized linkage between initial attitude toward an organization of publicity-only

exposure and organizational attractiveness affected by pub-licity and postjob ad combined.

In the positive publicity group model (Figure 2, Model 1), a statistically significant and negative correlation was found between initial attitude toward an organization and perceived truthfulness of a recruiting ad (y = -.26, p< .01). Statistical significance was also noted for the nonstandardized path coefficients from perceived truthfulness of a recruiting ad (g = .72, p< .01), from attitude toward a recruiting ad (b = .54, p< .01), and from organizational attractiveness (b = .74, p< .01). In the negative publicity group model (Figure 2, Model 2), the nonstandardized path coeffi-cients from perceived truthfulness of a recruiting ad (g = .68, p< .01), from attitude toward a recruiting ad (b = .63, p< .01), and from organizational attractiveness (b = .78, p< .01) were all significant. These imply that both positive and negative publicity groups support Hypothesis 1b, 1c, and 1d.

Performing a subgroup analysis requires examining a free estimated model in which path coefficients vary across detailed and general recruitment advertising groups. Exam-ining a fully constrained model requires setting equal path

Initial attitude toward organization

Organizational

attractiveness Job pursuit intention Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement Attitude toward recruiting advertisement .72**(.58*) .13(.10) .54** (.57**) .74**(.76**) -.26** (-.39**)

Model 1: Positive Publicity

Initial attitude toward organization

Organizational

attractiveness Job pursuit intention Perceived truthfulness of recruiting advertisement Attitude toward recruiting advertisement .68**(.57*) .16**(.13**) .63** (.63**) .78**(.76**) .06 (.08)

Model 2: Negative Publicity

Figure 2 Results of baseline model of groups of negative publicity and positive publicity. The values indicate the nonstandardized coefficients. The

standardized coefficients are in parentheses. **p< .01.

Table 2 Overall Fit Indices for the Baseline Models

Model/fit indices c2

(4) p RMSEA SRMR GFI CFI c2/df

Positive publicity 8.90 .06 0.079 0.037 0.98 0.99 2.23 Negative publicity 4.44 .34 0.023 0.030 0.99 1.00 1.11

coefficients for both groups. A significant c2 difference between the free estimated model and the fully constrained model suggests the existence of moderating effects.

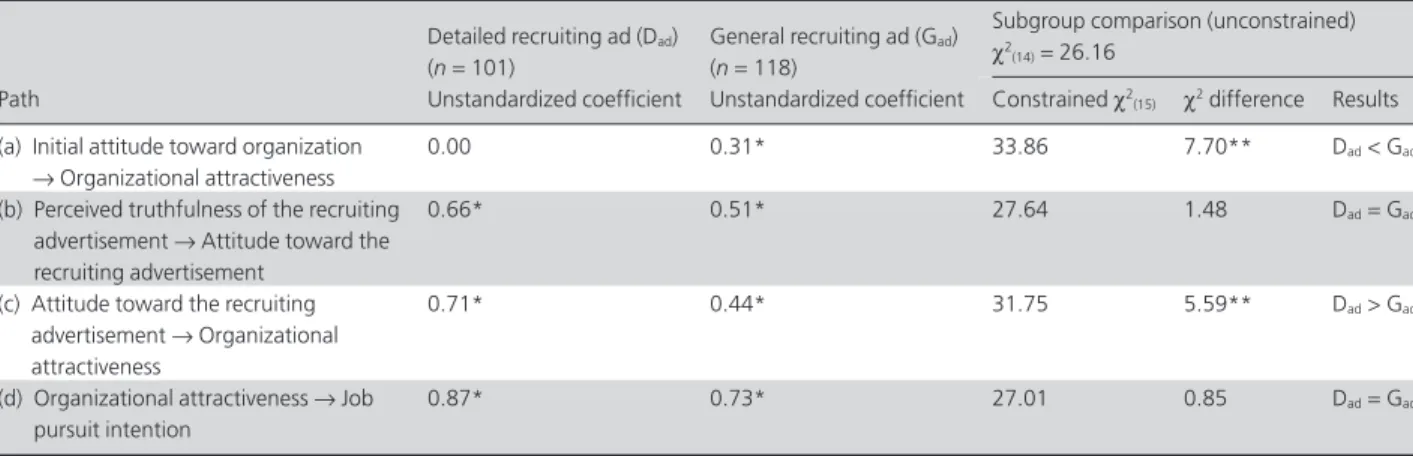

Thec2statistics for the free estimated and the fully con-strained models of positive publicity group were 12.54 (df= 14) and 12.73 (df = 18). The c2difference between these two models was 0.29, while df= 4, and nonsignificant at a = 0.05, indicating that no moderating effect exists in the positive publicity group model, whether the detailed or the general recruiting advertisement was intervened. Thec2 sta-tistics for the free estimated and the fully constrained models of the negative publicity group were 26.16 (df= 14) and 40.79 (df= 18). The c2difference between these two models was 14.63, while df= 4, and significant at a = 0.05, indicating that moderating effects do exist in the negative publicity group model when recruiting advertisement was intervened. This also supports Hypothesis 2, that the specificity of recruiting advertisement (detailed vs. general) only has impact on the proposed structural relations for those participants reading the negative publicity article.

While the full path coefficients reveal moderating effects in the negative publicity group, this research further exam-ined the moderating effects of individual paths using thec2 difference. Table 3 presents the moderating effects for indi-vidual paths of the negative publicity group. The results shown in Table 3 indicate that path a (initial attitude toward organization → organizational attractiveness) and path c (attitude toward the recruiting job advertisement→ organi-zational attractiveness) evidence significant c2 difference between group ND and NG. However, the effects of per-ceived truthfulness of a recruiting ad on attitude toward the recruiting ad and organizational attractiveness on job pursuit intention are similar across both groups because path b and path d have a nonsignificant c2 difference between group ND and NG. That is, Hypothesis 3 is par-tially supported because only two hypothesized linkages

have significant differences between a detailed and a general job ad in negative publicity exposure.

Furthermore, the influence of initial attitude toward an organization resulting from negative publicity on organiza-tional attractiveness intervened in a consequent recruiting advertisement was weaker for individuals who read the detailed recruiting advertisement compared with those who read the general recruiting advertisement. In negative public-ity exposure, less strength of path a (initial attitude toward organization→ organizational attractiveness) implies higher mitigation of consequent job ad intervention. Results of the subgroup comparison indicate significant difference on path a and the unstandardized coefficient shows that the value of a detailed job ad is less than the value of a general job ad; that is, the detailed job ad has greater mitigating effect than the general job ad in negative publicity than the sequent job ad. The significant difference of path c (attitude toward the recruiting job advertisement → organizational attractive-ness) also reveals that the detailed job ad has greater effect on attitude toward ad and organizational attractiveness. This also means that the effect of attitude toward the recruiting advertisement on organizational attractiveness was stronger for individuals who read the detailed recruiting advertise-ment than for those who read the general recruiting advertisement. In sum, in negative publicity exposure, the consequent detailed recruiting advertisement indeed has greater impact on organizational attraction than the general recruiting advertisement.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This study contributes to recruitment research by examin-ing the effect of positive or negative publicity and subse-quent detailed or general recruiting advertisement on

Table 3 Results of Multigroup Comparison

Path Detailed recruiting ad (Dad) (n= 101) Unstandardized coefficient General recruiting ad (Gad) (n= 118) Unstandardized coefficient

Subgroup comparison (unconstrained) c2

(14)= 26.16

Constrainedc2

(15) c2difference Results

(a) Initial attitude toward organization → Organizational attractiveness

0.00 0.31* 33.86 7.70** Dad< Gad

(b) Perceived truthfulness of the recruiting advertisement→ Attitude toward the recruiting advertisement

0.66* 0.51* 27.64 1.48 Dad= Gad

(c) Attitude toward the recruiting advertisement→ Organizational attractiveness

0.71* 0.44* 31.75 5.59** Dad> Gad

(d) Organizational attractiveness→ Job pursuit intention

0.87* 0.73* 27.01 0.85 Dad= Gad

organizational attractiveness and job pursuit intention. Results reveal that negative publicity significantly affects initial organizational attitude more than positive publicity. Perceived truthfulness of job ad through attitude toward advertisement affected organizational attractiveness in pub-licity, then job ad sequence.

This study also found that specificity of recruiting adver-tisement (detailed vs. general) exerts a different effect on theoretical hypothesized linkages among participants who read negative publicity, but not among those who read posi-tive publicity. For those reading negaposi-tive publicity, the detailed job ad strengthened the effects of attitude toward recruiting advertisement on organizational attractiveness, more so than the general job ad did. Participants who received the detailed job ad also exerted weaker effect on the relationship between initial attitudes toward an organiza-tion of negative publicity-only exposure and organizaorganiza-tional attractiveness affected by negative publicity and job ad com-bined than those who received general job ad correspond-ingly. Stated another way, the detailed job ad significantly weakened negative publicity effect on applicant attraction than the general job ad did. Hence, this study argues that the extent of job ad specificity relates to job seekers’ perception of the job ad and recruiting companies in negative publicity exposure.

The primary finding of this study highlights the moderat-ing effect of recruitmoderat-ing advertisement specificity on a company suffering negative publicity rather than facing posi-tive publicity. One likely explanation is the recognition that publicity is more trustworthy than advertising (Cameron, 1994; Hallahan, 1999; Wang, 2006; Wang & Nelson, 2006). Potential applicants probably give more confidence to posi-tive publicity than recruiting advertisement; therefore, a sub-sequent recruiting ad may offer additional reference sources. Furthermore, the potential applicant in this scenario may not distinguish between a detailed and a general recruiting advertisement. In contrast, this finding also might be due to negativity effect, in that negative information is considered more diagnostic or informative than positive information (Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy, 1990; Skowronski & Carlston, 1989), but positive or neutral information is less useful for categorizing purposes (Herr et al., 1991). For those applicants who read negative publicity, more specific recruiting advertisements might provide more useful information for diagnostic evaluation purposes—in other words, specific advertisements provide organizational clues to weigh against negative publicity. These results are compatible with those reported by Pullig, Netemeyer, and Biswas (2006), who used Pham and Muthukrishnan’s (2002) search-and-alignment model to show that negative publicity may negatively affect the initial attitude toward an organization. Our findings are in line with Chapman et al.’s (2005) proposed model, that reaction to recruiting sources affects attitude toward a

recruited company, which in turn affects job pursuit intention.

Practical implication

Inducing positive publicity facilitates organizational reputa-tion and enhances initial attracreputa-tion to a company. A company could sensationalize positive publicity by the fol-lowing marketing communication practices. First, by offer-ing an initiative and information to media about company news and activities in terms of press releases or a press con-ference. Second, a necessary condition for media coverage is an active effort by companies to utilize marketing public relations; this effort includes teasers of commercials and interviews with the figurehead or spokesperson in the advertisement, enabling news media to put together their own segments and voice-overs (Jin, Suh, & Donavan, 2008). These advertising campaigns would focus on “importance” and “interesting” cues, and celebrity figures could generate extensive publicity for the endorsed brand to capture media attention (Erdogan, Baker, & Tagg, 2001). Finally, this study suggests that public relation efforts to relate to newsworthi-ness result in high publicity, such as creating good buzz in terms of corporate sponsorships, fulfilling corporate social responsibility (CSR), and positive word of mouth with company-driven events.

Managing negative publicity is very difficult, even when an organization knows it will soon appear. Dean (2004) sug-gested that the most appropriate response to restoring a company’s image is combining corrective action and com-pensation (“reduction of offensiveness”) strategies. Managers of companies suffering from negative publicity should focus on their reputation for social responsibility and a willingness to make appropriate responses. While CSR might visibly enhance stakeholders’ identification with a firm, this strategy is more effective for companies with long CSR histories, but in all cases firms must be willing to address skepticism about claims that they make (Vanhamme & Grobben, 2009).

Compared with advertisements specifically written to recruit new employees, studies have shown corporate image advertising to positively affect the quantity and quality of an organization’s applicant pool (Collins & Han, 2004) as well as job seekers’ perceptions of the organization. Companies can also use corporate advertising affiliated with corporate marketing efforts to promote themselves to external labor markets to enhance organizational awareness and familiarity, and to strengthen both employment brand and its attractive-ness to potential applicants (Cable & Turban, 2001, 2003; Chapman et al., 2005; Van Hoye & Lievens, 2009).

Finally, companies suffering from negative publicity can use specific recruiting advertisements to soften destructive impacts. Catching the attention of potential applicants most likely requires persuasive and attractive cues. We suggest

posting links to additional information via recruiting websites, brochures, and online or call inquiry services. The results of this study strongly suggest that companies include external information sources in their recruitment mix for their perceived credibility and to impact both organizational attractiveness and pursuit of job openings.

Limitations and future research

The main limitations to this study concern the generalizabil-ity of our interpretations and findings. First, the experimental design of this study depended on carefully manipulating information sources and timing participant access to them. Without this, it would be very difficult to investigate the topic empirically by assessing potential candidates’ attraction to organizations and how positive or negative publicity affects those attitudes. Future researchers might time their studies according to prescheduled or annual reports such as CSR or Fortune magazine’s annual ranking efforts.

Second, this research did not consider the effects of reading positive or negative publicity in a range of sources, which could very well produce different effects. Marketing research-ers have found that perceptions of publicity expertise and media credibility moderate the effects of publicity on

consumers; researchers may want to extend this finding to employee recruitment and applicant job decision making. Various media primarily present publicity, but certain types of publicity (e.g., technical reports or professional market analyses) aim at very specific targets. Researchers may investi-gate the specific domain of publicity impacts on specific applicants’ recruiting, such as headhunting talents or profes-sional workers.

Third, this study used a fictitious company to prevent the confounding effects of participant familiarity with and atti-tudes toward actual firms. We cannot claim that our findings can be generalized to well-known companies or newborn/ low-profile companies. According to Cable and Turban (2003), employer branding influences job-seeking behaviors; therefore, future researchers may be interested in investigat-ing positive or negative publicity effects involvinvestigat-ing brand familiarity and corporate reputation effects.

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Science Council in Taiwan for provid-ing research grants (NSC 95-2416-H-017 -002, NSC 96-2416-H-017 -001) to support this study.

References

Ahluwalia, R., Burnkrant, R. E., & Unnava, H. R. (2000). Consumer response to negative publicity: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Marketing

Research, 37, 203–214.

Anderson, N. H. (1971). Integration theory and attitude change. Psychological

Review, 78, 171–206.

Anderson, R. E. (1973). Consumer dissatis-faction: The effect of disconfirmed expectancy on perceived product per-formance. Journal of Marketing Research,

10, 38–44.

Barber, A. E. (1998). Recruiting

employ-ees: Individual and organizational per-spectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Fink-enauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General

Psychology, 5, 323–370.

Belt, J. A., & Paolillo, J. G. P. (1982). The influence of corporate image and specifi-city of candidate qualifications on response to recruitment advertisement.

Journal of Management, 8, 105.

Breaugh, J. A., Macan, T. H., & Grambow, D. M. (2008). Employee recruitment: Current knowledge and important areas for future research. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International review of

industrial and organizational psychology

(Vol. 23, pp. 45–82). New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Buckley, M. R., Fedor, D. B., Veres, J. G., Wiese, D. S., & Carraher, S. M. (1998). Investigating newcomer expectations and job-related outcomes. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 83, 452–461.

Cable, D. M., & Graham, M. E. (2000). The determinants of job seekers’ reputation perceptions. Journal of Organizational

Behavior, 21, 929–947.

Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. B. (2001). Establishing the dimensions, sources, and value of job seekers’employer knowledge during recruitment. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and

human resources management (Vol. 20,

pp. 115–164). New York: Elsevier

Science.

Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. B. (2003). The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity

perspective. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 33, 2244–2266.

Cameron, G. T. (1994). Does publicity outperform advertising? An experimen-tal test of the third-party endorsement.

Journal of Public Relations Research, 6,

185–207.

Carlson, K. D., Connerley, M. L., & Mecham, R. L. (2002). Recruitment evaluation: The case for assessing the quality of applicants attracted. Personnel

Psychology, 55, 461–490.

Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (2005). Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 90, 928–944.

Collins, C. J., & Han, J. (2004). Exploring applicant pool quantity and quality: The effects of early recruitment practice strategies, corporate advertising, and firm reputation. Personnel Psychology, 57, 685–717.

Collins, C. J., & Stevens, C. K. (2002). The relationship between early recruitment-related activities and the application decisions of new labor-market entrants:

A brand equity approach to recruitment.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1121–

1133.

Dean, D. H. (2004). Consumer reaction to negative publicity: Effects of corporate reputation, response, and responsibility for a crisis event. Journal of Business

Com-munication, 41, 192–210.

Ehrhart, K., & Ziegert, J. (2005). Why are individuals attracted to organizations?

Journal of Management, 31, 901–919.

Erdogan, B., Baker, M., & Tagg, S. (2001). Selecting celebrity endorsers: The practi-tioner’s perspective. Journal of

Advertis-ing Research, 41, 39–48.

Feldman, D. C., Bearden, W. O., & Hardesty, D. M. (2006). Varying the content of job advertsiements: The effects of message specificity. Journal of Advertising, 35, 123–141.

Feldman, J. M., & Lynch, J. G. (1988). Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, inten-tion, and behavior. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 73, 421–435.

Gatewood, R. D., Gowan, M. A., & Lauten-schlager, G. J. (1993). Corporate image, recruitment image, and initial job choice

decisions. Academy of Management

Journal, 36, 414–427.

Hallahan, K. (1999). Content class as a contextual cue in the cognitive process-ing of publicity versus advertisprocess-ing.

Journal of Public Relations Research, 11,

293–320.

Herr, P. M., Kardes, F. R., & Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective.

Journal of Consumer Research, 17, 454–

462.

Highhouse, S., Beadle, D., Gallo, A., & Miller, L. (1998). Get ’em while they last! Effects of scarcity information in job advertisements. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 28, 779–795.

Highhouse, S., & Hoffman, J. R. (2001). Organizational attraction and job choice. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.),

International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 16, pp.

37–64). New York: Wiley.

Jin, H. S. (2003). Compounding consumer interest: Effects of advertising campaign publicity on the ability to recall

subse-quent advertisements. Journal of

Adver-tising, 32, 29–41.

Jin, H. S., Suh, J., & Donavan, D. T. (2008). Salient effects of publicity in advertised brand recall and recognition. Journal of

Advertising, 37, 45–57.

Jin, H. S., Zhao, X., & An, S. (2006). Examin-ing effects of advertisExamin-ing campaign publicity in a field study. Journal of

Advertising Research, 46, 171–182.

Kanar, A. M., Collins, C. J., & Bell, B. S. (2010). A comparison of the effects of positive and negative information on job seekers’ organizational attraction and attribute recall. Human Performance, 23, 193–212.

Kardes, F. R. (2002). Consumer behavior and

managerial decision making (2nd ed.).

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Kim, J., Yoon, H. J., & Lee, S. Y. (2010).

Inte-grating advertising and publicity. Journal

of Advertising, 39, 97–114.

LaBella, C., & Koehler, D. J. (2004). Dilution and confirmation of probability judg-ments based on nondiagnostic evidence.

Memory & Cognition, 32, 1076.

Lemmink, J., Schuijf, A., & Streukens, S. (2003). The role of corporate image and company employment image in explain-ing application intentions. Journal of

Economic Psychology, 24, 1–15.

Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. (2003). The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56, 75–102.

Loda, M. D., & Coleman, B. C. (2005). Sequence matters: A more effective way to use advertising and publicity. Journal

of Advertising Research, 45, 362–372.

Lynch, J. G. (2006).

Accessibility-diagnosticity and the multiple pathway

anchoring and adjustment model.

Journal of Consumer Research, 33,

25–27.

MacKenzie, S. B., Lutz, R. J., & Belch, G. E. (1986). The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effec-tiveness: A test of competing explana-tions. Journal of Marketing Research, 23, 130–143.

Maheswaran, D., & Meyers-Levy, J. (1990). The influence of message framing and issue involvement. Journal of Marketing

Research, 27, 361–367.

Mason, N. A., & Belt, J. A. (1986).

Effective-ness of specificity in recruitment

advertising. Journal of Management, 12, 425–432.

Meijer, M., & Kleinnijenhuis, J. (2007). News and advertisements: How negative news may reverse advertising effects.

Journal of Advertising Research, 47, 507–

517.

Orlitzky, M. (2007). Recruitment strategy. In P. F. Boxall, J. Purcell, & P. Wright (Eds.), The oxford handbook of human

resource management (pp. 273–299).

Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pham, M. T., & Muthukrishnan, A. V.

(2002). Search and alignment in

judgment revision: Implications for brand positioning. Journal of Marketing

Research, 39, 18–30.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and rec-ommended remedies. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Preston, I. L. (2002). A problem ignored: Dilution and negation of consumer information by antifactual content.

Journal of Consumer Affairs, 36, 263–283.

Preston, I. L. (2003). Dilution and negation of consumer information by antifactual content: Proposals for solutions. Journal

of Consumer Affairs, 37, 1–21.

Pullig, C., Netemeyer, R. G., & Biswas, A. (2006). Attitude basis, certainty, and challenge alignment: A case of negative brand publicity. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 34, 528–542.

Rafaeli, A., & Oliver, A. L. (1998). Employ-ment ads: A configurational research agenda. Journal of Management Inquiry,

7, 342–358.

Roberson, Q. M., Collins, C. J., & Oreg, S. (2005). The effects of recruitment message specificity on applicant attrac-tion to organizaattrac-tions. Journal of Business

and Psychology, 19, 319–339.

Rynes, S. L., & Cable, D. M. (2003).

Recruit-ment research in the twenty-first

century. In W. Borman, D. Ilgen, & R. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (Vol. 12, pp. 55–76). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Sicilia, M., Ruiz, S., & Reynolds, N. (2006). Attitude formation online: How the

consumer’s need for cognition affects the relationship between attitude towards the website and attitude towards the brand. International Journal of Market

Research, 48, 139–154.

Simmons, C. J., Bickart, B. A., & Lynch, J. G. (1993). Capturing and creating public opinion in survey research. Journal of

Consumer Research, 20, 316–329.

Skowronski, J. J., & Carlston, D. E. (1987). Social judgment and social memory: The role of cue diagnosticity in negativity, positivity, and extremity biases. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 52,

689–699.

Skowronski, J. J., & Carlston, D. E. (1989). Negativity and extremity biases in impression formation: A review of expla-nations. Psychological Bulletin 105, 131– 142.

Slaughter, J., & Greguras, G. (2009). Initial attraction to organizations: The influ-ence of trait inferinflu-ences. International

Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17,

1–18.

Smith, R. E., & Vogt, C. A. (1995). The effects of integrating advertising and negative word-of-mouth

communica-tions on message processing and

response. Journal of Consumer

Psychol-ogy, 4, 133–151.

Snyder, R. (1989). Misleading characteris-tics of implied-superiority claims.

Journal of Advertising, 18, 54–61.

Stammerjohan, C., Wood, C. M., Chang, Y., & Thorson, E. (2005). An empirical investigation of the interaction between publicity, advertising, and previous brand attitudes and knowledge. Journal

of Advertising, 34, 55–67.

Taylor, G. S. (1994). The relationship between sources of new employees and attitudes toward the job. Journal of Social

Psychology, 134, 99–110.

Turban, D. B. (2001). Organizational attrac-tiveness as an employer on college cam-puses: An examination of the applicant population. Journal of Vocational

Behav-ior, 58, 293–312.

Turban, D. B., & Keon, T. L. (1993). Organi-zational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied

Psychol-ogy, 78, 184–193.

Vanhamme, J., & Grobben, B. (2009). “Too good to be true!” The effectiveness of CSR history in countering negative pub-licity. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 273– 283.

Van Hoye, G., & Lievens, F. (2005).

Recruitment-related information

sources and organizational attractive-ness: Can something be done about

negative publicity? International Journal

of Selection and Assessment, 13, 179–187.

Van Hoye, G., & Lievens, F. (2007). Social influences on organizational attractive-ness: Investigating if and when word of mouth matters. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 37, 2024–2047.

Van Hoye, G., & Lievens, F. (2009). Tapping the grapevine: A closer look at word-of-mouth as a recruitment source. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 94, 341–352.

Wang, A. (2006). When synergy in market-ing communication online enhances audience response: The effects of varying advertising and product publicity mes-sages. Journal of Advertising Research, 46, 160–171.

Wang, S. L. A., & Nelson, R. A. (2006). The effects of identical versus varied advertis-ing and publicity messages on consumer response. Journal of Marketing

Commu-nications, 12, 109–123.

Werbel, J. D., & Landau, J. (1996). The effec-tiveness of different recruitment sources: A mediating variable analysis. Journal of

Applied Social Psychology, 26, 1337–1350.

Zottoli, M. A., & Wanous, J. P. (2000). Recruitment source research: Current status and future directions. Human

Resource Management Review, 10, 353–