國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

漢語他動動詞「推」與「拉」詞彙語意研究

A Lexical Semantic Study of TUI and LA in Mandarin

研究生:洪宛儀

指導教授:劉美君教授

漢語他動動詞「推」與「拉」詞彙語意研究

A Lexical Semantic Study of TUI and LA in Mandarin

研究生:洪宛儀 Student: Wan-Yi Hung

指導教授:劉美君 Advisor: Mei-Chun Liu

國立交通大學

外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics

College of Humanity and Social Science

National Chiao Tung University

in partial Fulfilment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Arts

June 2014

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

i 漢語他動動詞「推」與「拉」詞彙語意研究 研究生:洪宛儀 指導教授:劉美君 國立交通大學外國語文學系外國文學與語言學碩士班

摘要

本研究試圖從詞彙語意學的角度來探討漢語他動動詞「推」與「拉」的研究。主要 會探討三個主要議題:1)漢語他動動詞「推」與「拉」以及其他原型他動動詞的語意區 分;2) 深入討論漢語他動動詞「推」與「拉」跟時貌標記如「著」的相關性;3) 試圖 解釋「推」與「拉」的多種語意擴展之關聯。 根據李(2007)的原型他動動詞移動事件之研究,我們可以區分及解釋他動動詞「推」 與「拉」以及其他原型他動動詞的語意及句法的不同。他動動詞「推」與「拉」通常會 比較側重主事者和受事者之間的致使施力(causing event),而其他原型他動動詞比較側重受事者的移動事件(motion event)。進一步結合李(2007)與 Talmy(2000),我們可以很

明確的區分「推」與「拉」跟時貌標記「著」一起使用的語意區別。當「推」與「拉」

單獨呈現時,通常會比較側重致使事件,而當致使事件變成只是表現出一種移動方式

(Manner)時,也就是說在句法上「推」與「拉」跟時貌標記「著」一起使用的情況之下

([推/拉+著]),通常會強調受事者的移動方式(manner-with-motion)。

最後結合了框架語意(Fillmore and Atkins 1992)、原型理論(Rosch 1973)及概念隱喻

理論(Lakoff and Johnson 1980, Langacker 1987),我們探討了「推」與「拉」語意之句法

的相關連性。為框架詞彙語意理論,本研究提出了一個概念上的架構來描述「推」與「拉」

延伸語意之間的相關連性,也推論了「推」與「拉」的意思都是種這個原型語意延伸出

ii 鑑於認知詞彙語意的角度,本研究提供了一個系統性的框架來分析動詞語意,也呈 現了不同的語言在詞彙化過程中也會有不同的語意選擇與延伸;因此,本研究反映詞彙 擴展的多意性。 關鍵詞: 漢語「推」字,漢語「拉」字, 漢語推拉他動動詞,框架語意學, 詞彙語意學, 語意擴展, 概念隱喻理論, 原型理論

iii

A Lexical Semantic Study of TUI and LA in Mandarin

Student: Wan-Yi Hung Advisor: Mei-Chun Liu

Graduate Institute of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics National Chiao Tung University

Abstract

This study attempts to investigate three issues: 1) to distinguish and explain the distinct

semantic and syntactic differences between a prototypical caused-motion verb with those of

tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull;’ 2) to discuss the aspectual correlations of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull;’ and 3) to explain the interrelationship of the multiplex metaphorical extensions

of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’

Based on Li (2007), we can distinguish and explain the distinct semantic and syntactic differences between a prototypical caused-motion verb with those of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ where the former profiles the motion event focusing on the physical translocation of

the Moved Entity, while the latter profiles the causing event stressing on the force interaction

between the Agent and the Moved Entity. With further incorporation of Li (2007) and Talmy (2000), we’ve presented the distinction of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with or without the

co-occurrence of aspectual marker zhe 著 by showing that without zhe 著, tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ typically emphasizes on the causing event; however, with zhe 著, the causing event

becomes an event that only demonstrates a kind of Manner. Therefore, based on Talmy (2000),

we can thus view [tuī/lā+zhe] as demonstrating a kind of motion-with-manner.

By merging Frame Semantics (Fillmore and Atkins 1992), Prototype Theory (Rosch

1973) and Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, Langacker 1987), we can

examine the semantic-to-syntactic correlations between the various senses of tuī 推 ‘push’

iv

provides a conceptual schema to depict the interrelationship of the multiple senses of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ and provides a systematic and principled analysis of conceptualizing

these multiplex metaphorical extensions with related cognitive-frame elements.

In light of a cognitive-semantic approach of lexical semantics, this study provides a

systematic and unified framework in analyzing and representing verbal semantics and further

representing a clear case study that shows different languages have different manipulations of

lexical senses; therefore, reflecting the multiple senses of lexical extensions.

Keywords: Mandarin TUI, Mandarin LA, Mandarin Push/Pull Verbs, Frame Semantics,

Lexical Semantics, Semantic Extensions, Conceptual Metaphor Theory,

v

誌謝

蟬鳴讚頌著盛夏,溫暖夕陽灑落在小徑上,來到交通大學這個環境,三年的求學 時光即將來到尾聲。當時對語言學還懵懂無知的我,申請上研究所時的興奮依舊記憶猶 新;回想起研究所這段求學過程,經過獨立學習探討的淬鍊,最後獲取了得來不易的果 實,扎實豐富了我的青春時光。 感謝的話語總是訴說不盡,生活中的相處互動是難忘的交集。指導教授劉美君老師 總是有耐心、細心地指導著我,也像好朋友般分享生活上的大小事,遇到困難時可以與 老師談論;亦師亦友中也不失像媽媽一般,花費時間跟心思在我們身上,學生由衷感謝 研究所這期間的指導與照顧。 感謝就讀交大期間所有教導過我的老師們:劉辰生老師、林若望老師、賴郁雯老師、 廖秀真老師、盧郁安老師,謝謝您們在教學上的指導與教誨;還有系辦助理平時的幫忙 與協助;以及最重要的 304 研究團隊夥伴:湯忠豪、周書平、李懿方、胡韵庭,不僅是 平時專注於論文研究與討論,生活上也彼此督促與互相鼓勵,因為有你們的陪伴,讓我 渡過這段煎熬又歡樂的時光;還有學弟妹張睿敬、張哲瑋、楊宛潔,因為你們的提問與 建議幫助我在語料上更加深入思考,你們也是我的開心果。謝謝學長學姐們、同班同學 的寶貴意見,讓我受益良多。還有其他分道揚鑣的大學同窗好友,偶爾重逢相聚遊玩, 放鬆心情外也適時給予關心與打氣加油;謝謝好朋友總是在我身邊適時給予幫助、不厭 其煩陪伴著我,分擔精神上的壓力與當我的靠山。 最後,最深的感謝獻給我親愛的家人。感謝父母當初的決定,讓我獨自一人回來臺 灣念書求學,大學四年加上研究所三年,七年時光看似漫長卻也短暫飛逝,這期間我獨 自學習面對困難,學會獨立,逼迫自己成長;感謝父母多年來的支持與越洋電話中的陪 伴,永遠做我堅強的依靠,父母永遠都是我最好的朋友,最愛的家人。要是沒有你們當 初的決定,我也不會有今日的成就。爸、媽,我做到了!謝謝你們,我愛你們!

vi

Table of Contents

Chinese Abstract………..i English Abstract……….iii Acknowledgement………..v Table of Contents………...vi List of Tables………. ix List of Figures………..…...x Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 The Issues ... 21.2.1 Issue 1: Tuī and Lā as Caused-motion verbs ... 2

1.2.2 Issue 2: Aspectual correlations of Tuī and Lā ... 5

1.2.3 Issue 3: Multiplex Sense Extensions of Tuī and Lā ... 7

1.3 Scope and Goal ... 12

1.4 Organization of the Thesis ... 13

Chapter 2 Literature Review ... 14

2.1 Previous Works on Motion Events ... 14

2.1.1 Lexicalization Patterns and Co-event Relations... 14

2.1.2 Proto-Caused-Motion Event ... 16

2.1.3 Constructional Analysis of Caused-motion... 17

2.1.4 Proto-Motion Event Schema ... 20

2.1.5 Intermin Summary... 21

2.2 Previous Works on English Push/Pull verbs ... 23

2.2.1 Frame-based Approach ... 23

2.2.2 Alternation-based Approach ... 25

2.3 Previous Works on Chinese Tuī and Lā ... 26

2.3.1 Corpus-Based Lexical Semantic Study of Lā ... 26

2.3.2 Cross-linguistic Semantic Analysis of 推-拉 versus Push-Pull ... 29

vii

Chapter 3 Database, Theoretical Framework and Methodology... 32

3.1 Database ... 32

3.2 Theoretical Framework ... 33

3.2.1 Frame Semantics: Fillmore and Atkins ... 33

3.2.2 Multi-layered Hierarchical Structure ... 34

3.2.3 The Prototype Category Theory: Rosch ... 35

3.2.4 Conceptual Metaphor Theory: Lakoff and Johnson ... 36

3.3 Methodology & Procedure ... 37

Chapter 4 Findings ... 40

4.1 Grammatical and Distributional Frequency: Motional and Non-motional Events ... 40

4.2 Semantic Properties of Tuī and Lā ... 47

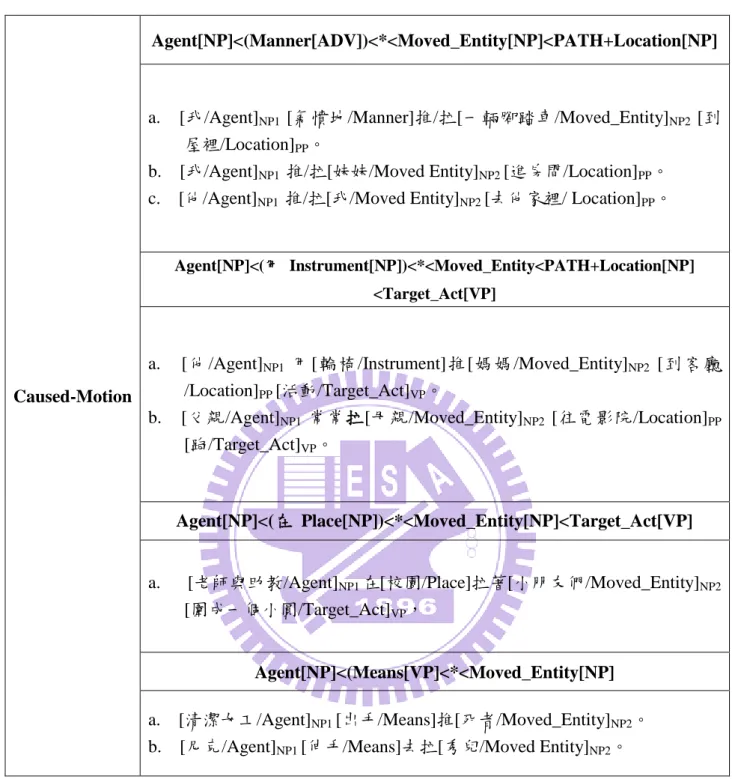

4.2.1 Tuī and Lā as Caused-Motion Verbs: Push and Pull ... 47

4.3 Tuī and Lā co-occurring with Lái and Qù ... 62

4.4 Aspectual Variations of Tuī and Lā ... 67

4.5 Morphological Make-ups ... 73

4.6 Non-motional uses of Tuī and Lā ... 75

Chapter 5 Analysis ... 77

5.1 Conceptual Schema of the Prototype of Tuī and Lā ... 77

5.1.1 The Prototype of Tuī ... 79

5.1.2 The Prototype of Lā... 81

5.1.3 The Semantic and Syntactic Attributes of Prototype Tuī and Lā ... 82

5.2 Tuī and Lā versus Bān and Yí ... 83

5.3 Tuī and Lā with Aspectual Zhe ... 87

5.4 Tuī and Lā with Deictic Lái and Qù ... 92

5.5 Metaphorical Extensions of Tuī and Lā ... 97

5.5.1 Metaphorical Extensions of Tuī ... 98

5.5.2 Metaphorical Extensions of Lā ... 105

viii

5.6.1 Conceptual Schema of Caused-motion ... 113

5.6.2 The Hierarchical Structure of the Frame ... 114

5.6.3 Overview of the Frames ... 124

5.7 Summary ... 127 Chapter 6 Conclusion ... 128 6.1 Conclusion ... 128 6.2 Future Research ... 130 References... 131 Website Resources ... 137

ix

List of Tables

Table 1: Senses of tuī 推 in Chinese Wordnet ... 8

Table 2: Senses of lā 拉 in Chinese Wordnet ... 8

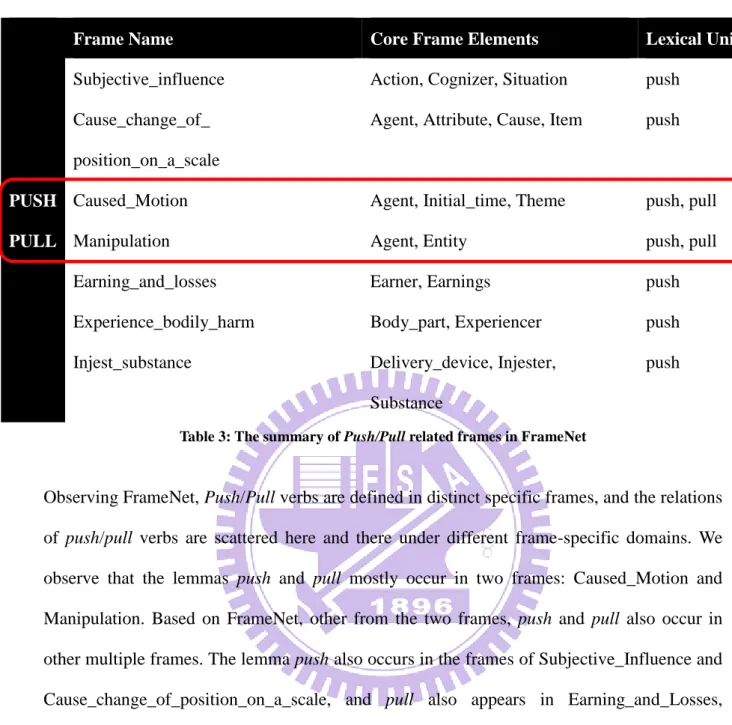

Table 3: The summary of Push/Pull related frames in FrameNet ... 24

Table 4: The summary of Push/Pull related verb classes in Levin (1993) ... 25

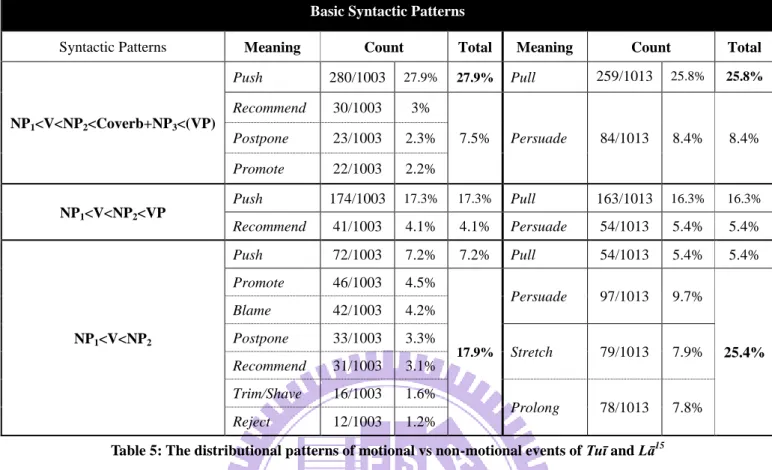

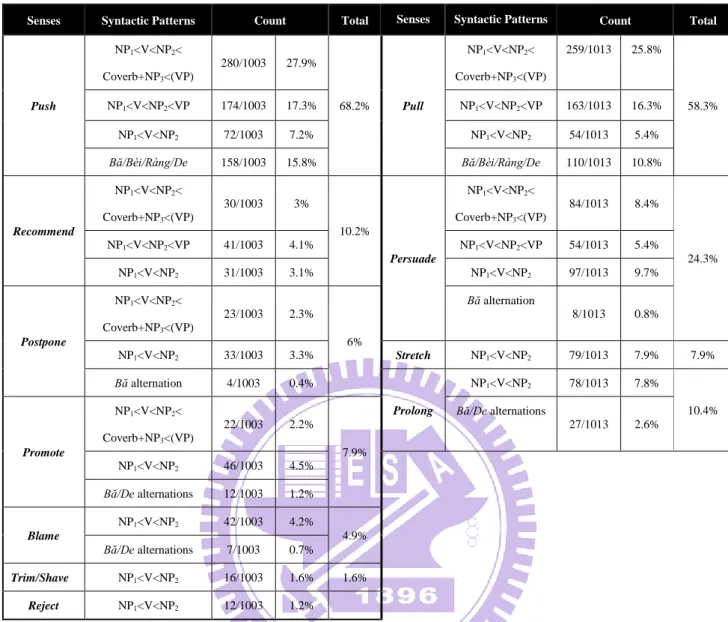

Table 5: The distributional patterns of motional vs non-motional events of Tuī and Lā ... 44

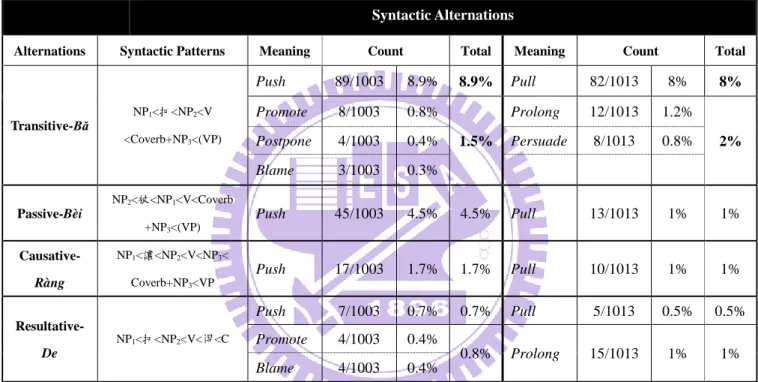

Table 6: The Syntactic alternations of motional vs non-motional events of Tuī and Lā ... 45

Table 7: The Distributional Frequency of Tuī and Lā with Various Senses and Syntactic Patterns ... 46

Table 8: Summary of the core-participant roles in the causal events of Tuī and Lā ... 54

Table 9: Syntactic patterns mapped onto semantic roles ... 58

Table 10: The Semantic Features of the Roles of Motional tuī and lā ... 62

Table 11: The Distributional Frequency of Motional tuī and lā with Deictic lái and qù ... 63

Table 12: The aspectual variations of Tuī and Lā ... 72

Table 13: The distributional frequency of Tuī and Lā with Aspectual Zhe ... 72

Table 14: Morphological make-ups in the events of Tuī and Lā ... 74

Table 15: Various categories of Moved Entity in the events of Tuī and Lā ... 75

x

List of Figures

Figure 1: Typical Caused-motion concept (Li 2007: 24) ... 16

Figure 2: Typical Caused-motion concept (Li 2007: 23) ... 17

Figure 3: English Caused-Motion Construction (Li 1995, 7: 160) ... 18

Figure 4: The Deictic-incorporated Proto-Motion Event Schema (Liu 2013: 19) ... 20

Figure 5: Typical Caused-motion concept of Tuī and Lā ... 22

Figure 6: Serial Motion Event of Tuī and Lā... 22

Figure 7: The frame relation of Push/Pull verbs in FrameNet ... 23

Figure 8: The core meaning of Lā 拉 (Liao 2003: 41) ... 27

Figure 9: Extended meaning of Lā 拉 (Liao 2003: 42) ... 28

Figure 10: Distribution of Categories (Chen 2012:8) ... 29

Figure 11: The prototypical sense schema of Mandarin tuī ... 80

Figure 12: The prototypical sense schema of Mandarin lā ... 81

Figure 13: The prototypical caused-motion conceptual schema ... 85

Figure 14: The prototypical causal event of Tuī and Lā ... 85

Figure 15: The profiled event of prototypical caused-motion verb ... 86

Figure 16: The profiled events of tuī and lā ... 86

Figure 17: The profiled events of tuī and lā ... 89

Figure 18: The image schema of [V+Ø ] ... 90

Figure 19: The image schema of [V+ZHE] ... 91

Figure 20: Speaker as Goal ([V+Lái]) ... 94

Figure 21: Goal = unclear ([V+Qù]) ... 95

Figure 22: Destination as Goal ([V+Qù+Goal]) ... 96

Figure 23: The metaphorical extension of ‘to trim/shave’ ... 99

Figure 24: The metaphorical extension of ‘to recommend/promote’ ... 101

Figure 25: Metaphorical Transfer from spatial domain to non-spatial domain ... 101

Figure 26: The metaphorical extension of ‘to postpone’ ... 102

Figure 27: Temporal events of ‘postponing’ conceptualized as a physical object ... 103

Figure 28: The metaphorical extension of ‘to evade/reject’ ... 104

Figure 29: The Gestalt Conceptual Schema of Metaphorical Extensions of Tuī ... 105

Figure 30: The metaphorical extension of ‘to increase voicing’ ... 107

Figure 31: The metaphorical extension of ‘to persuade/attract’ ... 108

Figure 32: Metaphorical Transfer of “to increase voice and to persuade/attract” ... 108

Figure 33: The metaphorical extension of ‘to prolong’ ... 109

Figure 34: Temporal events of ‘postponing’ conceptualized as a physical object ... 110

Figure 35: The metaphorical extension of ‘to persuade/attract’ ... 111

xi

Figure 37: The Conceptual Schema of Caused-motion ... 113 Figure 38: The Hierarchical Structure of the Frames ... 114 Figure 39: Primary Frames under Caused-motion Archiframe ... 118

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Background

Lexical semantics has always been one of the core issues in both theoretical and applied

linguistics. Recent developments of lexical semantics has shown close interaction between the

semantic properties of lexical items and syntactic behaviors with a general assumption that the

syntactic behavior of a verb, is determined by the meaning of the verb (cf. Levin 1993,

Fillmore 1982, Fillmore and Atkins 1992, Levin and Rappaport 2005, Liu 2002, among others)

and interacts with constructional patterns (cf. Jackendoff 1990, 2002; Goldberg 1995, 2006,

2010). In particular, verbal semantics has always been a central concern, since verbs are

considered to be the core of sentences and crucial in delimiting syntactic structures

(Jackendoff 1983, Levin 1993).

Several pioneering studies have shown great contributions: Fillmore (1971) proposes Frame Semantics, emphasizing that “meanings are relativized to frames;” Levin (1993)

classifies English verbs into semantically distinct classes with a diathesis alternation approach; Goldberg (2005) proposes that “each word sense evokes an established semantic frame;” and

Liu (2002) focuses on Mandarin verbal semantics particularly on the study of Mandarin

near-synonyms with corpus-based approach and proposes that verbal semantics is determined

by its verbal syntactic behaviors. These previous studies have built a solid foundation for the

study of verbal semantics. However, verbs with multiplex sense extentions; that is, a single

verb mapped onto multiple sense domains through metaphorical or metanymic transfers, have

2

In light of the frameworks above, this study attempts to examine the semantic-to-syntactic correlations of the diverse uses and sense extensions of tuī 推 ‘push’

and lā 拉 ‘pull’ by exploring the cognitive semantic mechanisms involved. It will explain the

interrelationship among such diverse usages and analyze the metaphorical extensions of the

core meaning, which can be mapped onto multiple semantic domains that are conceptualized

as related cognitive-frames in the view of Frame Semantics (Fillmore and Atkins 1992).

1.2 The Issues

The issues this study is concerned about include: 1) tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ as

Caused-motion verbs; 2) Aspectual correlations of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull;’ and 3)

Multiplex Sense Extensions of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’

1.2.1 Issue 1: Tuī and Lā as Caused-motion verbs

Mandarin tuī 推 and lā 拉 are equivalent to the English verbs push and pull. As verbs

pertaining to caused-motion, tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ not only posit the semantic and

syntactic properties of a typical caused-motion verb, that is, an Agent exerting an external

force and thus causing a translocational movement of the affected object (Theme/Patient) (Talmy 1985, 2000; Li 2007), but tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ also posit intimate deictic

relations between the Agent and the Moved Entity. In (1) below, presents the prototypical caused-motion event and (2) illustrates the event of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull:’

3

(1) Proto-caused-motion events:

[NP1我][V搬/移][NP2一箱蘋果][PP到屋裡]。

wǒ bān/yí yì-xiāng píngguǒ dào wū-lǐ

I move one-box apple arrive house-inside

‘I moved a box of apples into the house.’

(2) Causal events of tuī and lā:

[NP1我][V推/拉][NP2一輛腳踏車][PP到屋裡]。

wǒ tuī/lā yí-liàng jiǎotàchē dào wū-lǐ

I push/pull one bicycle arrive house-inside ‘I pushed/pulled a bicycle into the house.’

In the above (1) and (2) examples, it clearly demonstrates that the events of tuī 推 ‘push’

and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are quite similar to that of prototypical caused-motion events which usually depict the syntactic pattern of [NP1 V NP2 PP] with the notion of ‘X CAUSES Y TO MOVE

Z’ (Goldberg 1995). This phenomenon of the obligation to have a PP in prototypical

caused-motion event in Chinese is also corresponding to those of English where the PP must

be considered when determining the causal event of a verb (Goldberg 1995). Other from

being verbs pertaining to caused-motion, tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ also posit intimate

deictic relations between the Agent and the Moved Entity as illustrated in (3) and (4):

(3) [Tuī/Lā+NP+Deictic]

我[V推/拉]父親[Deictic來/去]紀念堂。

wǒ tuī/lā fùqīn lái/qù jìniàntang

I push/pull father come/go memorial hall

4

(4) [Tuī/Lā+Deictic]

(a) 民眾[V推/拉Deictic來]一車垃圾包。

mín-zhòng tuī/lā lái yì-chē lèsèbāo

people push/pull come one-car trash bag

‘People pushed/pulled over a pile of trash bags.’

(b) *民眾[V推/拉Deictic去]一車垃圾包。

mín-zhòng tuī/lā qù yì-chē lèsèbāo

people push/pull go one-car trash bag

*‘People pushed/pulled away a pile of trash bags.’

A closer look at examples (3) and (4), we observe that there’s not only a causal relation

between the motion event and the causing event (Talmy 1976, 1985, 1991, 2000; Li 2007), but there’s also an intimate deictic relation between the Agent and the Moved Entity in the

events of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’ In (3), we can either say wǒ tuī/lā fùqīn lái/qù

jìniàntang 我推/拉父親來/去紀念堂 ‘I pushed/pulled my dad to come/to go to the memorial

hall.’ However, in (4), it is more preferred to say mín-zhòng tuī/lā lái yì-chē lèsèbāo 民眾推/

拉來一車垃圾包 ‘People pushed/pulled over a pile of trash bags,’ that is, tuī 推 ‘push’ and

lā 拉 ‘pull’ plus deictic lái 來 ‘come’ ([Tuī/Lā+lái]) meaning to push/pull over than to say

*mín-zhòng tuī/lā qù yì-chē lèsèbāo *民眾推/拉去一車垃圾包 *‘People pushed/pulled

away a pile of trash bags,’ that is, tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ plus deictic qù 去 ‘go’

([Tuī/Lā+qù]) meaning to push/pull away. Why is this the case and how can we deal with such

collocational constraints? Why is movement towards the speaker better than movement away from the speaker? Moreover, how can we explain the following cases in (5) where tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are immediately followed by zǒu 走 ‘to leave,’ which, like qù 去

5

(5) [Tuī/Lā+ zǒu]

(a) 工務單位出動推土機[V推V走]巨石。

gongwù dānwèi chū-dòng tuītǔjī tuī zǒu jùshí

service division set-out bulldozer push go huge-stone

‘The service division set-out bullozers to push away huge stones.’

(b) 每天都有南方來的客商[V拉V走]十幾車土豆,

měitiān dōu yǒu nánfang lái de kè-shāng lā zǒu shí jǐ chē tǔdòu

everyday all have southern come POSS merchants pull go ten more car potato

‘Southern merchants come everyday to pull away more than a dozen cars of potatoes.’

1.2.2 Issue 2: Aspectual correlations of Tuī and Lā

Other from observing that tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ depict intimate relations with

deictic lái 來 ‘come’ and qù 去 ‘go,’ we also discover that, based on corpus distributions,

the majority of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ as verbs pertaining to caused motion,

frequently collocate with aspectual marker zhe 著 instead of other aspectual markers such as le 了 and guò 過1

as illustrated in the examples below:

(6) [V + ASP]

(a) 他推著輪椅進學校上課,

tā tuī zhe lúnyǐ jìn xuéxiào shàng-kè

1

The present study only considered tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with the collocation of aspectual marker zhe 著 and not other aspectual markers such as le 了 and guò 過 for tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ plus zhe 著 occupies the majority of the data set and there are some collocational constraints that changes the semantics of the verbs.

6

he push ASP wheelchair enter school class ‘He pushed the wheelchair into school for classes.’

(b) 他們會拉著你到一個人少的角落,

tāmén huì lā zhe nǐ dào yí-ge rén shǎo de jiǎoluò they will pull ASP you arrive one people few DE corner

‘They will pull you to a corner where less people are around.’

(c) 母親推著小孩參觀美術館,

mǔqīn tuī zhe xiǎohái cānguān měishùguǎn mother push ASP child visit museum

‘Mother pushed the child to visit the museum.’

(d) 王叔叔拉著母親一起合照,

wáng shúshu lā zhe mǔqīn yìqǐ hézhào

Wang uncle pull ASP mom together take-picture

‘Uncle Wang pulled mom to take a picture together.’

Therefore, the examples in (6) lead us to wonder: Whether or not the collocation of aspectual marker zhe 著,have similar semantic properties as those without one? If so, under

what circumstances do we choose to use zhe 著 and when without it? And if not, what are the

7

1.2.3 Issue 3: Multiplex Sense Extensions of Tuī and Lā

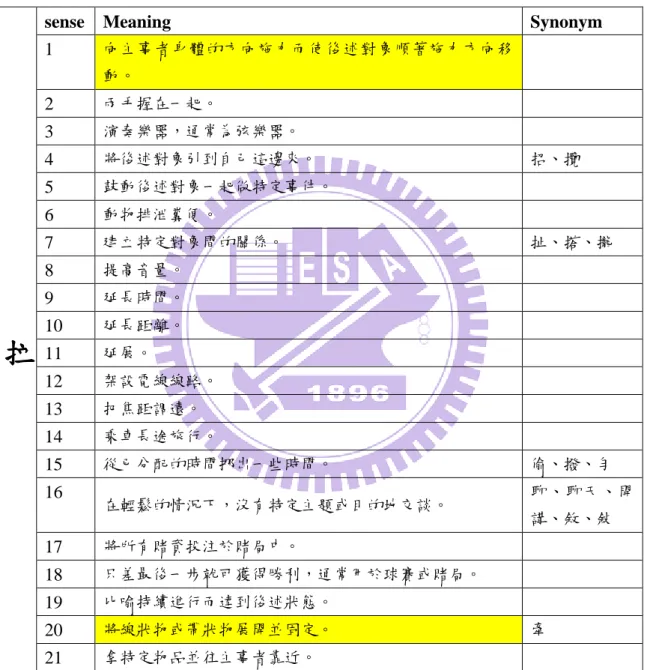

Mandarin verbs tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are transitive and semantically diverse

with multiplex sense extensions. According to the online lexical database, Chinese Wordnet2,

tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are identified with 18 and 21 senses respectively which are

embodied by precise expressions of sense and sense relations as shown in the following

tables:

推

sense Meaning Synonym

1 反主事者身體方向施力而使後述對象順著施力方向移 動。3 2 比喻逃避責任或義務。 踢 3 比喻將預定的時間往後移。 延期、延後、 延 4 比喻拒絕接受後述對象。 5 比喻公布並推銷後述對象。 6 比喻眾人同意讓後述對象擔任特定職務。 公推、推舉、 舉 7 比喻介紹後述對象的優點讓大眾知道。 8 認為後述對象最符合前述描述。 9 比喻使事件發展到後述狀態。 10 根據前述訊息來判斷並得知後述結論。 11 從時間參考點開始計算。 12 用工具在物體表面修剪長在該物體表面的後述對象,通常 是較短的毛髮或草。 推移 13 筋骨損傷時,用手調整身體結構,治療疾病。 嚕 14 用手或特定工具在皮膚表面揉搓。 15 把焦距調近。

2 Chinese WordNet is constructed by Academia Sinica to serve as a large-scale semantic lexical

database for Chinese with precise expressions of sense and sense relations (Huang et al., 2008b). The information of the lexical entry analyzed in this database contain the following: parts-of-speech, sense notions, examples, corresponding English synset(s) from Princeton WordNet, lexical semantic relations and much more that are theoretically based on lexical semantics.

3 The highlighted sense descriptions represent the motional uses of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ that involve

8 16 演奏弦樂器時手指按住弦向掌心施力,使音產生由高到低 的律動,通常用於吉他。 17 比喻贊成他人所發表的言論。 18 以推動的方式使特定液狀物質均勻地分佈在特定物體的 表面上。

Table 1: Senses of tuī 推 in Chinese Wordnet

拉

sense Meaning Synonym

1 向主事者身體的方向施力而使後述對象順著施力方向移 動。 2 兩手握在一起。 3 演奏樂器,通常為弦樂器。 4 將後述對象引到自己這邊來。 招、攬 5 鼓動後述對象一起做特定事件。 6 動物排泄糞便。 7 建立特定對象間的關係。 扯、搭、攏 8 提高音量。 9 延長時間。 10 延長距離。 11 延展。 12 架設電線線路。 13 把焦距調遠。 14 乘車長途旅行。 15 從已分配的時間挪出一些時間。 偷、撥、勻 16 在輕鬆的情況下,沒有特定主題或目的地交談。 聊、聊天、開 講、敘、敍 17 將所有賭資投注於賭局中。 18 只差最後一步就可獲得勝利,通常用於球賽或賭局。 19 比喻持續進行而達到後述狀態。 20 將線狀物或帶狀物展開並固定。 牽 21 拿特定物品並往主事者靠近。

Table 2: Senses of lā 拉 in Chinese Wordnet

Based on the above sense descriptions along with their synonym sets, these findings have

revealed that tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ posit multiplex senses where both motional and

9

of these lexical entries.

On the basis of Chinese WordNet with the multiplex senses of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉

‘pull,’ a further view into corpus distribution has also proved that tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are associated with wide ranges of sense extensions, where tuī 推 ‘push’ appears to

bear at least six extended senses and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with at least three extended senses other

than the prototypical meaning of to push and to pull as listed below:

(7) The multiplex sense extensions of Tuī 推 ‘push’

(a) Extension 1: to recommend someone or something to the outside world (tuī-jiàn推薦 ‘recommend’)

兩院主動推代表。

liǎng yuan zhǔdòng tuī dàibiǎo

two court initiate push representative

‘The two courts are initiatively recommending representatives.’

(b) Extension 2: to promote or advertise a product to the outside world (tuī-xiāo推銷 ‘promote’)

他們也在本地推 ichon-Kun 周邊產品,

tā-mén yězài běndì tuī ichon-Kun zhōu-biān shāngpǐn

they also at local push ichon-Kun surrounding product

‘They are also promoting ichon-Kun surrounding products at local places.’

(c) Extension 3: to postpone a previously set temporal event (tuī-yán推延 ‘postpone’) 占旭剛再度推婚期。

10

zhànxùgāng again push wedding date

‘Zhang Xu-Gang is postponing the wedding date again.’

(d) Extension 4: to evade or shrink responsibility or obligation (tuī-xiè推卸 ‘refuse’) 雙方互推責任。

shuāng fang hù tuī zérèn

two sides mutual push responsibility

‘The two sides are mutually shrinking off responsibilities.’

(e) Extension 5: to trim or shave hairy parts of body or surface (tuī-diào推掉 ‘trim’) 什麼年代了居然還有人規定要去推頭髮!

shéme nián-dài le jūrán hái yǒu rén guīding yào qù tuī tóu-fǎ

what decade ASP surprisingly still have people require to go push hair

‘What decade is today that still have some people requiring to go to trim their hair.’

(f) Extension 6: to reject an offer or invitation (tuī-diào推掉 ‘reject’) 林老師又再推邀請。

lín lǎo shī yòu zài tuī yāoqǐng

lin teacher again is push invitation

‘Teacher Lin is pushing off invitations again.’

(8) The multiplex sense extensions of Lā 拉 ‘pull’

(a) Extension 1: to extend or delay a time that is set previously (lā-cháng拉長 ‘lengthen’) 記者又在拉時間,

11

reporter again pull time

‘The reporter is prolonging the time again.’

(b) Extension 2: to increase voice (lā-kāi拉開 ‘increase’) 今晚心血來潮,突然很想拉嗓子!

jīn wǎn xīn-xiě-lái-cháo túrán hěn xiǎng lā sǎngzi

tonight heart-blood-come-wave suddenly really want pull throat ‘Tonight I suddenly have the feeling of increasing my voice.’

(c) Extension 3: to persuade/attract/gain consumers from buying or joining an

organization or company (lā-lǒng拉攏 ‘persuade/attract’) 業者都在動腦筋拉客人。

yèzhě dōu zài dòng nǎojīn lā kèrén

industry all is move brain pull consumer

‘All industries are thinking of ways to attract consumers.’

In order to account for the intimate deictic relations between the Agent and the Moved Entity in the events of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ the collocational constraints of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with the occurrence of aspectual marker zhe 著, and their possible wide

ranges of sense extensions, the following research questions are thus raised:

1. In general, what are the distinct grammatical and distributional patterns

underlying tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull?’ More specifically, how can we explain the deictic (lái 來 ‘come’/qù 去 ‘go’) relations between the Agent and the Moved Entity that are occurring with tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull?’ What are the collocational constraints of aspectual markers in the events of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā

12

拉 ‘pull’ based on corpus distributions?

2. Based on the observations of syntactic behaviors, what kind of generalizations can be made as to the semantic-to-syntactic correlations? That is, what are the distinct semantic criteria and conceptual principles revealed in the distributional patterns of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull?’

3. How can we explain the wide ranges of metaphorical extensions underlying the different uses of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull?’ How are the different senses interrelated? What is the principled account for dealing with such a diverse range of uses?

1.3 Scope and Goal

The scope of this paper is limited to the transitive usages of Mandarin caused-motion

verbs: tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ as main predicates, with the focus of observing the

construction of [V+NP expressions]. With a further look into corpus data, the distributional

frequencies and collocational patterns reveal that tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ depict both

motional and non-motional distinctions which correspond to our classification and

categorization of the causal events of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’4 and the metaphorical

extensions of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ through the exploration of frame-specific semantic

roles of the complement NP(s).

4 The events of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are those that are categorized and classified under the frame of

13

By integrating Frame Semantics (Fillmore and Atkins 1992), Prototype Theory (Rosch

1973, 1978) and Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff and Johnson 1980, Langacker 1987),

the goal of this study aims to explore the cognitive-semantic motivations of the multiplex metaphorical extensions of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ and examine the

semantic-to-syntactic correlations among the various senses of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’

On the basis of frame-based verbal semantic approach, this paper further aims to provide

a conceptual schema to depict the interrelationship of the multiple senses of tuī 推 ‘push’ and

lā 拉 ‘pull’ that are constructed under one single verb sense and provides a systematic and

principled analysis for the conceptualization of the multiplex extended senses of tuī 推 ‘push’

and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with related cognitive-frame elements.

1.4 Organization of the Thesis

The thesis is organized as follows: Chapter 1 presents the general introduction of the

study along with some background knowledge relevant to the issues. Chapter 2 reviews

previous works related to the studies on English and Mandarin motion events, how English

Push/Pull verbs relate to those of Mandarin tuī 推 and lā 拉, and previous studies on Mandarin tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’ Chapter 3 lists the database, theoretical framework and

methodology applied. In Chapter 4, corpus observations on grammatical and distributional

patterns will be presented. Chapter 5 proposes a frame-based analysis on Mandarin tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’ Last but not least, Chapter 6 concludes the thesis with related issues

14

Chapter 2

Literature Review

Tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ as verbs pertaining to caused-motion in Mandarin,

correspond to verbs of exerting force: Push/Pull verbs in English (Levin 1993). As indicated

by Levin (1993), these verbs have a causal relation of exerting a force onto an entity where

push and pull are different in meaning with respect to the direction of force being exerted. As

caused-motion verbs, push and pull are also categorized as verbs under the frame of

Caused_Motion from the perspective of Frame Semantics (Fillmore 1982). However, contrary to English push/pull, tuī 推 and lā 拉 not only posit properties of a caused-motion verb, but

they also demonstrate intimate deictic relations between the Agent and the Moved Entity. In

this section, the traditional notions of motion events and the previous studies on the semantic

distinctions of English Push/Pull verbs and Chinese tuī 推 and lā 拉 will be briefly reviewed.

2.1 Previous Works on Motion Events

2.1.1 Lexicalization Patterns and Co-event Relations

From the perspective of Cognitive Semantics, Talmy (2000) proposes that a motion event

typically involves four internal components: Figure, Move, Path, and Ground which are

defined as an object (the Figure), under a motional act (Move), moving or located with

respect to a location (the Ground) followed by a path or site (the Path). Besides the above

four internal components, a motion event can also be associated with two additional external

15

(9) (a) The pencil rolled off the table.

[Move+Manner]

(b) I pushed the keg into the storeroom.

[Move+Cause] (Talmy 2000, vol. II: 26, 4)

The examples in (9) illustrate the typical motion events which are exhibited by the verbs

rolled and pushed. In (9a), rolled expresses how the pencil moves and thereby expressing the

Manner of motion, while in (9b), pushed exerts an external force that causes the pencil to

move and thus describing the Cause of motion. The two external co-event components

Manner and Cause thus divide the translational or spatial motion event into two types:

self-initiated motion (9a) and other-initiated motion (9b). In order to define the co-event

relations, Talmy proposes the co-event conflation patterns which conflate the main motion

event and the subordinate co-event with the forms WITH-THE-MANNER-OF and

WITH-THE-CAUSE-OF as the following examples illustrate:

(10) (a) MOVE + Manner

The rock rolled down the hill.

= [The rock MOVED down the hill] WITH-THE-MANNER-OF [the rock

rolled].

(b) MOVE + Cause

I kicked the keg into the storeroom.

16

= [I AMOVED the keg into the storeroom]

WITH-THE-CAUSE-OF [I kicked the keg]5.

(Talmy 2000:30)

Under the lexicalization patterns and the co-event conflations proposed by Talmy (2000), the

translational motion events can thus be divided into two groups: self-motion event and

caused-motion event which usually involves an external force/cause.

2.1.2 Proto-Caused-Motion Event

Following the framework of Talmy’s motion events, Li (2007) attempts to focus on

caused-motion events and classify Mandarin caused-motion verbs into prototypical versus

non-prototypical ones. A Caused-motion event, according to Li (2007), involves five internal

chain-effected components: Causer, Driving Force, Theme, Motion, and Path which made

up the conceptual structure of a typical caused-motion event as illustrated below:

Figure 1: Typical Caused-motion concept (Li 2007: 24)

Based on Li (2007), a typical caused-motion event consists of a series of subevents: the

causing event and the motion event, where the two entities or subevents have a causal relation,

with one causing the other to undergo a translocational change, that is, the motion is initiated

5 The subscript “

A” is placed before a verb to indicate that the verb is agentive. (AMOVED= CAUSE to MOVE)

(Talmy 2000)

Typical Caused-motion concept

17

and controlled by an external causer. This typical caused-motion event is illustrated below6:

Figure 2: Typical Caused-motion concept (Li 2007: 23)

With the above five internal components and the association of the two subevents, Li (2007)

further proposes that a prototypical caused-motion event consists of ‘a human Causer

volitionally exerts physical force and acted directly on a physical Theme and immediately caused the physical theme to move along a physical Path in a physical space.’

2.1.3 Constructional Analysis of Caused-motion

Other from the lexical and cognitive approaches to caused-motion, there are

constructional-based approaches to account for both English and Chinese caused-motion

verbs regarding the form-to-meaning correspondences. Under the framework of Construction

Grammar, Goldberg (1995) defines English caused-motion as structurally following the

pattern: [SUB [V OBJ OBL] with the meaning of ‘X CAUSES Y TO MOVE Z’; that is, ‘the

causer argument directly causes the theme argument to move along a path designated by the

directional phrase.’ The form-meaning correspondence can be represented in figure 3:

6

An example for the involvement of two subevents given by Li (2007) could be: ‘Mary pushed Jim into the room,’ which involves one entity moves from one location to another location under the direct impact of an external causer.

Motion event

Subevent 1

CauserCausing Action

Subevent 2

ThemeMotion

18

Figure 3: English Caused-Motion Construction (Li 1995, 7: 160)

The above figure illustrates the mapping of the syntactic form and the constructional meaning

which postulates that any lexical verb, either encode or not encode the sense of motion will be

associated with the sense of caused-motion once situated under such construction. For

instance, the verb sneeze as in ‘Frank sneezed the napkin off the table.’

As for the analysis of caused-motion in Chinese, Pan and Chang (2005) did a

comparative study on English and Chinese caused-motion construction and pointed out that

the crucial distinction between Chinese and English lies in the use of causative markers. In

Chinese, causative markers such as bǎ 把, shǐ 使, or rang 讓 are commonly used to

express causative motions, whereas in English, the notion of caused-motion can only be

expressed by the rigid pattern of (i.e. [NP1 V NP2 PP]).

Moreover, Chinese illustrates vast ways of encoding the path of motion. A caused-motion

event in Chinese can usually be expressed by a main verb following a preposition or a non-predicate verb to indicate the direction or path of motion, such as V 在 ‘at,’ V 到 ‘ arrive,’

V 向 ‘face,’ V 往 ‘go toward,’ V 上來 ‘go up,’ V 下來 ‘come down,’ V 進來 ‘come in,’ V 出來 ‘come out,’ V 回來 ‘come back,’ whereas in English, path can only be encoded in a

preposition as shown in the following contrastive pairs (11) and (12):

(11) English caused-motion pattern:

19

(b) Jane sewed a button onto the jacket

(12) Chinese caused-motion pattern: (a) 他把車開到南京了。

tā bǎ chē kāi dào nánjīng le

he BA car drive arrive Nanjing le ‘He drove the car to Nanjing.’

(b) 他把球扔向了我。

tā bǎ qiú rēng xiàng le wǒ

he BA ball throw face le me ‘He threw me the ball.’

(c) 我們把羊群放出去了。

wǒ men bǎ yang.qún fàng chū.qù le

we BA goats.group release out.go le ‘We’ve released the goats.’

Based on Pan and Chang (2005), a typical caused-motion construction in Chinese may show

various patterns when encoding a caused-motion event. It may be involved in either a

causative sentence with non-predicate verb or a BA-construction with V-Preposition patterns (e.g., tā bă chē kāi dào nánjīng le 他把車開到南京了 ‘He drove the car to Nanjing’) or

V-Directional patterns (e.g., tā bă mùtong tí shànglái le 他把木桶提上來了 ‘He lifted up the

20 2.1.4 Proto-Motion Event Schema

Besides the notion of motion events proposed by Talmy (2000), Li (2007), and Goldberg

(1995), Liu et al. (2013) also proposes a proto-motion event schema consisting of five

essential semantic components: Manner, Route, Direction, Endpoint, and Deictic that

pertain to a prototypical motion event. According to Liu (2013), a motion event may be

conceptualized as the sequence of how a journey or motional contour is formed with the

starting point of ‘a chosen Manner, via a certain Route, in a given Direction, towards a

targeted Endpoint and finally approaching the Destination (normally manifested as a Loc-NP).

Optionally, a further specification of Deictic orientation can be added.’ Given the semantic

components pertaining to a proto-motion event and incorporating them in an iconic sequence

of sub-motion events and morphemes, the following Proto-Motion Event Schema (PMS)7 is

being proposed:

Figure 4: The Deictic-incorporated Proto-Motion Event Schema (Liu 2013: 19)

7 The double-arrowed head situated in between Locus-NP and Deictic represents the order of the two elements

21

With the proposed PMS, every motion verb can be plotted under a sub-portion of the event

schema. That is to say, every motion verb contains at least one semantic component that

encodes a sub-portion of the schema and if there is found to be more than one component

involved in a motion verb, the range of its meaning follows the left to right order of the

components on the given schema with the default sequence of a serial motion event as

illustrated in example 13 below:

(13) 球 [滚]Manner[落]Route[進]Direction[到]Endpoint 洞里[来]Deictic

qiú gǔn luò jìn dào dònglǐ lái

ball roll fall enter arrive hole come ‘The ball rolled and fell into the cave near me.’

By observing (13) above, the leftmost verb V1 gǔn 滾 ‘roll’ lexically encodes Manner; V2 luò 落 ‘fall’ encodes both Route and Direction; V3 jìn 進 ‘enter’ lexicalizes Direction and Endpoint, and the rightmost V4 dào 到 ‘arrive’ specifies Endpoint with an additional deictic marker lái 來 ‘come’ (which is optional) to indicate the relative position to the speaker.

2.1.5 Intermin Summary

Based on Talmy’s (2000) lexicalization patterns which distinguished

motion-with-manner and motion-with-cause, Li (2007) further states that typical

caused-motion concept involves two subevents (causing event and motion event) that are

causally related to each other, and Goldberg (1995) specifies a caused-motion construction

with the typical syntactic form of [SUBJ [V OBJ OBL]]. In view of these three studies, we

22

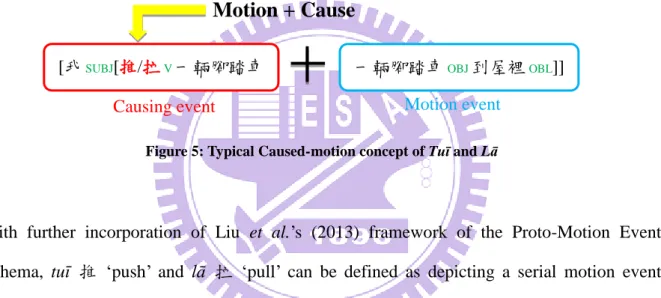

Based on Talmy (2000), tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ are said to be motion verbs that

are conflated with the co-event component Cause. Based on Li (2007), tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ as verbs pertaining to caused-motion, also consist the subevents of causing event

and motion event where the former and the latter are causally related to each other. Moreover,

based on Goldberg (1995), tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ also appear in the typical

caused-motion construction with the syntactic pattern of [SUBJ [V OBJ OBL]] as shown in

figure 5 below with the incorporation of Talmy (2000), Goldberg (1995) and Li’s (2007)

frameworks:

Figure 5: Typical Caused-motion concept of Tuī and Lā

With further incorporation of Liu et al.’s (2013) framework of the Proto-Motion Event Schema, tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ can be defined as depicting a serial motion event

with the further involvement of a causing event as illustrated below:

Figure 6: Serial Motion Event of Tuī and Lā

我推/拉他 [跑]Manner[到]Endpoint[會議廳]Loc-NP[去]Deictic

Causing event Motion event

Motion event

Causing event

[我SUBJ[推/拉V一輛腳踏車 一輛腳踏車OBJ到屋裡OBL]]

23 2.2 Previous Works on English Push/Pull verbs

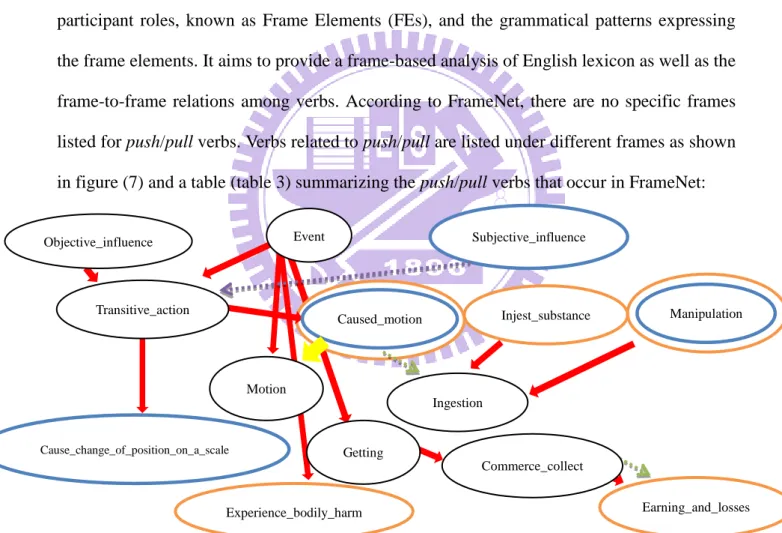

2.2.1 Frame-based Approach

The FrameNet Project (http://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/), created by the Institute of

California Berkeley, is an online lexical database that provides a frame-based analysis of

English lexical items. FrameNet provides each frame with its essential frame-specific

participant roles, known as Frame Elements (FEs), and the grammatical patterns expressing

the frame elements. It aims to provide a frame-based analysis of English lexicon as well as the

frame-to-frame relations among verbs. According to FrameNet, there are no specific frames

listed for push/pull verbs. Verbs related to push/pull are listed under different frames as shown

in figure (7) and a table (table 3) summarizing the push/pull verbs that occur in FrameNet:

Figure 7: The frame relation of Push/Pull verbs in FrameNet8

8 Figure 7 is not the original FrameGrapher (which shows the connections of several frames, demonstrates the

frame-to-frame relationships by different arrows representing respectively the relationships of Inheritance, Using, Precedes, Perspective_on, Inchoative_of, Causative_of, and See_also.) from FrameNet, this is a combined and merged version by the author of this paper with all the related frames for English Push/Pull verbs. Event Motion Subjective_influence Cause_change_of_position_on_a_scale Caused_motion Ingestion Transitive_action Manipulation Objective_influence Injest_substance Getting Commerce_collect Earning_and_losses Experience_bodily_harm

24

Table 3: The summary of Push/Pull related frames in FrameNet

Observing FrameNet, Push/Pull verbs are defined in distinct specific frames, and the relations

of push/pull verbs are scattered here and there under different frame-specific domains. We

observe that the lemmas push and pull mostly occur in two frames: Caused_Motion and

Manipulation. Based on FrameNet, other from the two frames, push and pull also occur in

other multiple frames. The lemma push also occurs in the frames of Subjective_Influence and

Cause_change_of_position_on_a_scale, and pull also appears in Earning_and_Losses,

Experience_bodily_harm, and Injest_substance.

However, even though push and pull occur with many other frames, all of them still have

an assumption in common of exerting physical force onto someone or something in order to

move them towards or away from oneself. By observing FrameNet, we believe that the events

of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’ its deictic relations between the Agent and the Moved entity

and its fruitful multiplex metaphorical extensions could not be fully accounted since

FrameNet based its analysis purely on English lexicon.

PUSH PULL

Frame Name Core Frame Elements Lexical Units

Subjective_influence Action, Cognizer, Situation push

Cause_change_of_

position_on_a_scale

Agent, Attribute, Cause, Item push

Caused_Motion Agent, Initial_time, Theme push, pull

Manipulation Agent, Entity push, pull

Earning_and_losses Earner, Earnings push

Experience_bodily_harm Body_part, Experiencer push

Injest_substance Delivery_device, Injester,

Substance

25 2.2.2 Alternation-based Approach

Other from analyzing English verbal semantics from the perspective of frame-based

approach, Levin (1993) focuses on English verb classes and alternations through the

perspective of alternation-based approach by investigating the expressions and interpretations

of different argument realizations of verbs. Based on this approach, Levin (1990: 185)

claimed that verbal behaviors provide the key evidence for the investigation of lexical

realizations of verbs. According to Levin, Push/Pull verbs are classified into three subclasses9:

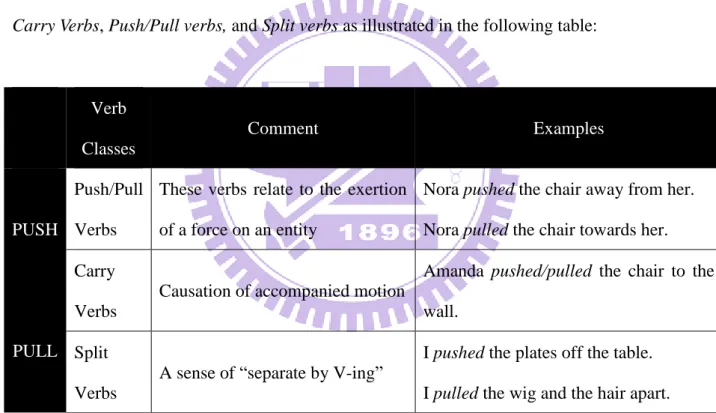

Carry Verbs, Push/Pull verbs, and Split verbs as illustrated in the following table:

Table 4: The summary of Push/Pull related verb classes in Levin (1993)

By observing table 4, it is found that English push/pull verbs are classified under three distinct verb classes based on the differences of verbal behaviors. According to Levin’s classification,

it illustrates clearly the syntactic distinctions without any further semantic characteristics of

9

Other from these three subclasses, push is also involved in the verb class of Funnel Verbs. However, we did not consider this verb class since we are more concerned with the verb classes that are shared by both class members of push and pull.

Verb Classes Comment Examples PUSH PULL Push/Pull Verbs

These verbs relate to the exertion

of a force on an entity

Nora pushed the chair away from her.

Nora pulled the chair towards her.

Carry

Verbs

Causation of accompanied motion

Amanda pushed/pulled the chair to the

wall.

Split

Verbs

A sense of “separate by V-ing”

I pushed the plates off the table.

26

each verb classes.

Based on Levin’s classification, we found that the first two verb classes correspond to

our syntactic patterns in Chinese. The first verb class of Push/Pull verbs correspond to our syntactic pattern of [NP1 V NP2 PP] such as: wǒ tuī/lā yí-liàng jiǎo-tà-chē dào wūlǐ 我推/拉 一輛腳踏車到屋裡 ‘I pushed/pulled a bicycle into the house’ and the second verb class of

Carry verbs correspond to our syntactic pattern of [NP1 V 著 NP2 VP] as in chénglong tuī/lā zhe wǒ méi-mìng-dì pǎo 成龍推/拉著我沒命地跑 ‘Jack Chen pushed/pulled me running

madly.’ However, by comparing the similar alternations as well as the semantic-to-syntactic

relations, it might not be fully adequate to describe the events of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull,’

their deictic relations between the Agent and the Moved Entity and their multiplex extended

senses, since it is found that Mandarin may display other alternation patterns that are distinct

from those of English push/pull verbs, due to the typological variations between the structures

of the two languages.

2.3 Previous Works on Chinese Tuī and Lā

2.3.1 Corpus-Based Lexical Semantic Study of Lā10

Based on corpus analysis, Liao (2003) manages to identify the semantic properties of

Mandarin Force Compulsion verb lā 拉 ‘pull’ through the examination of its grammatical

functions and collocational distributions. According to its grammatical functions, Liao (2003)

proposes that lā 拉 ‘pull’ can take a direct object with Ba-construction. With further

observation through collocational patterns, Liao (2003) observes that lā 拉 ‘pull’ can take

10 This paper originally focuses on the identification of semantic properties of Mandarin Force Compulsion

near-synonym set: lā 拉, tuō 拖, and 扯 chě; however, we only considered lā 拉 ‘pull’ for it is more relevant to the present study.

27

both concrete ([+animate]) and abstract (time, duration and relationship) object NPs. In the [+animate] concrete object NP, lā 拉 ‘pull’ may take either human entities or body parts (eg.,

hand). As for the [-animate] concrete object NPs, lā 拉 ‘pull’ may take both small mass

hand-manipulable objects (e.g., microphone) and large mass non-hand-manipulable objects

(e.g., car). With further view into the post verbal-DE complement, it is found that lā 拉 ‘pull’

often selects a path resultative with a descriptive complement, where it allows both vertical

and horizontal directional compliment.

Incorporating Frame-based approach, Liao (2003) classifies lā 拉 ‘pull’ under the frame

of Force-Compulsion with the elements of Force (the notion of direction), Mass (the qualities of the objects) and Acceleration (the speed of the action). The notion of lā 拉 ‘pull’ can be

read as ‘someone exerts the force on a target and causes a contact on the target.’ In this frame,

four participants are involved: Force-Initiator, Acceptor, (Path), and (Goal) where the roles

of Path and Goal are optional. With this notion in mind, the core meaning of lā 拉 ‘pull’

posits the sense of movement towards the direction of the force-initiator as in tā lā wǒ qù tā

jiālǐ 他拉我去他家裡 ‘He pulled me to his house.’

Adopting the Force Schema Theory, Liao (2003) further illustrates the core meaning of

lā 拉 ‘pull’ as well as its extended meanings as illustrated in the following force schemas11:

Figure 8: The core meaning of Lā 拉 (Liao 2003: 41)

11

In the force schemas, TR represents the Trajector and LM represents the Landmark which are generalizations of Figure and Ground in Langacker’s (1986) concepts. The LM is understood as the ground, the TR as an entity and the arrows represent the directionality of PATH.

28

Figure 9: Extended meaning of Lā 拉 (Liao 2003: 42)

In the figures above, the force-initiator may either stay still as in wǒ lā yǐzi guò lái 我拉 椅子過來 ‘I pulled the chair (to come over)’ (figure 8) or moves along with the acceptor as in

sheng-dàn lǎogonggong hé rén bàn yǎn de xúnlù lā zhe sānlúnchē guàng xiào yuán 聖誕老

公公和人扮演的馴鹿拉著三輪車逛校園 ‘Santa Claus and a people disguised as a reindeer

pulled a tricycle strolling through the campus’ (figure 9). In figure 8, the lines pointing to the

four different directions signal that the force-initiator does not undergo a translocational

movement, while it is the acceptor that moves toward the force-initiator. In figure 9, the

directionality of force is still towards the force-initiator, but at this time, it is the movement of

both the force-initiator and the acceptor. According to Liao (2003), this extended meaning

derives from the prototypical meaning of lā 拉 ‘pull.’ A possible reason for such co-motion

event might be that, based on Liao’s explanation, the acceptor ‘car,’ for example, is

semantically a moving object; therefore, the force-initiator would be affected by the acceptor

and as a result, moves along with it.

Liao (2003) then adopts Lakoff’s (1980) Metaphor Theory to explain the metaphorical extensions of lā 拉 ‘pull.’ Liao divides the extensions into two types: one has to deal with

human relations, while the other has to deal with time-lengthening. In the human relation, lā 拉 ‘pull’ can extend to mean the distance of human relation as in chéng zhǎng shǐ rén de jù lí

yuè lā yuè yuǎn 成長使人的距離愈拉愈遠 ‘Growth makes people’s distances farther and

29

sense of helping out as in lā tā yī bǎ 拉他一把 ‘Give him a hand.’ Under time-lengthening,

lā 拉 ‘pull’ can mean to extend a temporal event as in wèi le gong chéng jìn xíng shun lì shī gong qí xiàn bù dé bù lā cháng 為使工程進行順利,施工期限不得不拉長 ‘In order to

make the construction go smoothly, the deadline of the work cannot but lengthen for a period

of time.’

2.3.2 Cross-linguistic Semantic Analysis of 推-拉 versus Push-Pull

Based on a cross-linguistic analysis, Chen (2012) manages to focus on the reversive verb

pairs: tuī-lā 推-拉 and Push-Pull in Mandarin and English in order to compare and contrast

the lexical-semantic relations of their semantic ranges in both literal and metaphorical senses.

Chen (2012) categorizes the antonymous verb pairs into three classes: 1) personal: actions done on one’s body parts or mental processes, 2) social: actions on other people, and 3)

instrumental: actions on inanimate objects and tools in order to distinguish the patient roles

onto which the actions are imposed as shown in the following bar chart:

30

From the above chart, it shows that among the three categories, tuī 推—lā 拉 and

push-pull frequently perform actions under the instrumental category, that is, on instruments,

inanimate objects, and vehicles. Moreover, it is also shown that tuī 推 and push, compared to

their counterparts lā 拉 and pull, barely perform actions under the personal category.

Zooming into the personal category, it is observed that tuī 推 and push barely apply

actions on body parts except when it posits some surface contact as in yòng nèi jiā zhǎng lì

xiàng shēn qián xiǎo hé shàng bèi xīn yì tuī 用內家掌力向身前小和尚背心一推 ‘Use one’s

internal energy delivered through the palm to push the little monk’s back’ . In contrast, lā 拉

and pull usually requires the fingerly action as in shǒu lā shǒu 手拉手 ‘holding onto one’s

hand(s).’ Also, in both Chinese and English, pulling a face is being used metaphorically

meaning unable to raise or lower one’s social position relative to the addressee’s as in rán hòu

zì jǐ yòu hěn ài miàn zǐ lā bú xià liǎn lái gēn tā dào qiàn 然後自己又很愛面子,拉不下臉來

跟他道歉 ‘Because I had too much for my self-esteem, I was not able to pull my face down

for an apology.’

As for the social category, there are two types of movements: 1) Patient moving towards

or away from Agent and 2) both Agent and Patient move together with a constant distance

between them. In lā 拉 and pull, the actions usually involve an additional dimension on the

Patient—that is, the degree of willingness or conformation to move. This then brings to the

metaphorical extension of‘to attract’as in wèi le lā xué sheng jūn yā dī jià qián 為了拉學 生,均壓低價錢 ‘In order to attract students, the price is pressed down.’

In the instrumental category, tuī 推 and push are often used with furniture (door, bed,

chair) and vehicles (bike, trolley, wheelchair), while lā 拉 and pull are usually used with cloths

(string, rope, curtain) and objects with a line (plug). Moreover, tuī 推 and push appear to

provide a sense of multi-directional expansion which lead to the metaphorical extension of ‘selling a product’ as in tí gong suǒ xū kè chéng ér fēi yìng tuī kè chéng chǎn pǐn 提供所需課

31 2.3.3 Intermin Summary

In the previous sections, Liao (2003) and Chen (2012) have analyzed the semantic

properties and metaphorical extensions of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’ In Liao (2003), she

has identified the semantic properties of lā 拉 ‘pull’ through grammatical functions and

collocational distributions and categorizes lā 拉 ‘pull’ under Force Compulsion frame which

further divides the metaphorical extensions into two types: 1) human relationship and 2)

time-lengthening. On the other hand, Chen (2012) categorizes the metaphorical extensions of

tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ into three verb classes: 1) personal, 2) social, and 3)

instrumental.

However, they did not clearly explain the process of such metaphorical transfers and the

interrelationships among the diverse usages of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull.’ Moreover, they

did not go in dept to consider the intimate deictic relations between tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with deictic lái 來 ‘come’ and qù 去 ‘go’ and the collocational constraints of tuī 推

‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ with aspectual markers such as zhe 著. Therefore, this paper aims at

classifying and categorizing tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ under the frame of Caused_Motion

and aims to provide a principled account to explain such diverse usages of tuī 推 ‘push’ and

32

Chapter 3

Database, Theoretical Framework and Methodology

3.1 Database

The main body of data collected and analyzed in the present study comes from

real-occurring data in Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus of Mandarin Chinese (Sinica

Corpus)12 (http://dbo.sinica.edu.tw/SinicaCorpus/index.html/), which contains a total of ten

million words, consisting of vast topics ranging from society, life, literature, philosophy,

science and art along with computational tools for searching and making collocations

developed by the CKIP group in Academia Sinica, Taiwan. Another database is the Chinese

Word Sketch 13 (http://wordsketch.ling.sinica.edu.tw/), which contains grammatical

co-occurrence statistics and various distributional patterns. In addition to the two main

corpora above, other sources come from the FrameNet (http://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu/), the

Chinese Wordnet, (http://lope.linguistics.ntu.edu.tw/cwn/), and the most popular

daily-updated search engine “Google Search” (http://www.google.com.tw/).

12

Sinica Corpus contains a total of 316 lexical entries of tuī 推 ‘push’ and 538 lexical entries of lā 拉 ‘pull,’ and all of the lexical entries of tuī 推 ‘push’ and lā 拉 ‘pull’ have been observed.

13 Gigaword in Chinese Word Sketch (CWS) contains a total of 13501 lexical entries of tuī 推 ‘push’ and 25376

lexical entries of lā 拉‘pull’ where 687 entries of tuī 推 ‘push’ and 475 entries of lā 拉 ‘pull’ have been observed.