The Effects of Gloss Length and EFL Learners’ English

Proficiency Level on Vocabulary Retention

Shih-Han Tsai

University of TaipeiWen-Ying Lin

University of TaipeiAbstract

The present study aimed to examine the effects of gloss length and proficiency level on EFL learners’ vocabulary retention. The participants in the present study were 120 college students from a university in Taipei, Taiwan. Based on the scores of a proficiency test, the participants were divided into 2 groups: high proficiency vs. low proficiency. Each participant of the two groups was further randomly assigned to one of the two treatments: short glosses vs. long glosses. Thus, a total of four groups were formed: high proficient and long gloss (HL), high proficient and short gloss (HS), low proficient and long gloss (LL), and low proficient and short gloss (LS). The participants were then asked to read an assigned article with 18 words glossed and then answer five multiple-choice reading comprehension questions. After the reading task, they were immediately given an unannounced vocabulary test, in the form of matching, on the 18 glossed words. A delayed test was also administered 2 weeks later. The collected data were analyzed by using a two-way-mixed-design ANOVA. The results are summarized as follows. First, the result did not show a significant main effect of gloss length on vocabulary recognition (F(1, 116) = .08, p > .05). Second, the interaction effect between proficiency level and gloss length on the learners’ recognition of the target words was not significant (F(1, 116) =.03, p > .05). Third, the result failed to reveal a significant main effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention (F(1, 116) =.15, p > .05). Finally, the interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on the learners’ performance of vocabulary retention was not found to be significant (F(1, 116) =.09, p > .05). Based on these findings, some pedagogical implications and suggestions for future research were provided.

INTRODUCTION

In Taiwan, where English is taught as a foreign language (EFL), reading has been emphasized in English learning. However, the amount of effort spent does not seem to have paid off in recent years. In particular, in terms of Taiwanese students’ reading performance in the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) in 2010, Taiwan has been reported to rank sixth, falling behind several EFL countries in Asia, such as China and South Korea, and ESL (English as a second language) countries, such as the Philippines (Wang, 2012). Over time, many researchers have been interested in finding the main factors that cause hindrance to comprehending reading texts (e.g., Huang, 1997; Yeh & Wang, 2003). The results generally showed that small vocabulary size has been one of the major culprits that cause ESL/ EFL learners’ difficulties. Language learners in Taiwan, especially senior high students, tend to monotonously memorize large amounts of vocabulary items that are alphabetically arranged in a list. Unfortunately, this kind of rote learning tends to result in inefficient vocabulary retention. In view of this phenomenon, scholars have suggested that learners should enlarge their vocabulary size through extensive reading, which has also been highly promoted and extensively investigated in Taiwan in recent years (e.g., Lee, 2006; Sheu, 2003, 2004; Smith, 2011).

To maximize the effects of vocabulary learning through extensive reading, a number of scholars have recommended numerous methods, one of which is the use of glosses. Glosses are commonly held to be able to provide immediate assistance to learners. Numerous types of glosses, such as verbal gloss or visual gloss, have been suggested and researched. To date, related empirical findings generally have suggested that textual plus pictorial gloss (i.e., L1or L2 definition combined with a corresponding picture) is the most beneficial aid for vocabulary learning (Yanguas, 2009). Concern has also been voiced about whether the effect of textual plus pictorial gloss will vary depending on its length (AbuSeileek, 2011). To put it differently, it remains unexplored whether learners, when given long textual plus pictorial gloss, can perform significantly better than those aided with short gloss. Another related issue worth concern is about whether the effect of gloss on vocabulary retention will be different among learners at different proficiency levels. Collectively, what remains at issue is whether the effect of gloss on vocabulary retention would be influenced by its length, learners’ L2 proficiency level, and/or the interaction between these two factors. Hence, the current study made the first attempt to examine the effect of textual plus pictorial gloss on learners at different

proficiency levels, incorporating the manipulation of gloss length. In view of Taiwanese learners’ declining performance on reading comprehension tests, it was hoped that the results of the present study could provide valuable suggestions for practitioners, such as reading material designers, in choosing appropriate length for textual gloss for reading texts. Specifically, based on the results of the present study, if the learners with low proficiency could perform better when provided with pictorial plus short glosses in reading than when aided with long glosses, the materials with short length of gloss should be chosen particularly for them. On the other hand, if learners with high proficiency could have a better performance when given long glosses than when offered short glosses, materials with long textual definitions should be selected to facilitate their performance on reading and accordingly to enlarge their vocabulary size.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Vocabulary knowledge has long been considered as one of fundamental contributors to the comprehension of a text. The empirical evidence of the crucial role of vocabulary knowledge in reading comprehension and language learning has been obtained in many studies (e.g., August, Carlo, Dressler, & Snow, 2005; Baleghizadeh & Golbin, 2010; Wu & Hu, 2007). Among many variables investigated in Wu and Hu’s (2007) study, vocabulary was found to have a significant and positive correlation with reading achievement and play a main determinant role in reading comprehension. Just as Kruse (1979) put it, “Of prime importance in reading is vocabulary skill” (p. 208). To understand the message in a reading passage, readers first of all have to know the meanings of words and then process the sentences by combining the meanings of words to further grasp the main idea of the text. Nowadays, many teachers acknowledge that when students face an article written in the foreign language, those unknown vocabulary items seem to be their challenge (Grabe & Stoller, 2002). By acquiring large amounts of vocabulary, students can gain more efficiency in reading.

Despite the fact that vocabulary learning is very crucial in language learning, learners may not be able to master all the words needed while reading. Take English learners in Taiwan for example. The students’ exposure to English outside the classroom is quite limited, which may lead to an entire dependence on their teachers and may restrain them from obtaining sufficient input for additional expansion in

These two approaches, intentional and incidental learning, have been extensively investigated and have also shown to be effective for vocabulary learning. The main difference between these two lies in a methodological distinction—whether students are aware of an ensuing test or not. According to Hulstijn (2001), with intentional learning, students are notified in advance about the presence of a test on the specific knowledge after exposure. On the other hand, students will not be forewarned about a following test when they are in an incidental learning environment. Apart from the operational difference, word knowledge gained through incidental learning has also been perceived as a by-product of the main cognitive reading activity (Huckin & Coady, 1999; Kweon & Kim, 2008; Paribakht & Wesche, 1999). In other words, when students are engaged in incidental learning, they are instructed to read a text, with the main focus on the message of the text. When paying attention to the content of the text, they may tend to guess the unknown words from context. As such, Nation (2001) claimed that incidental learning through guessing from context is the most important of all sources of vocabulary learning.

In light of Nation’s (2001) positive comments on incidental learning, most researchers have been more interested in exploring the effect of incidental learning on learners’ performance of learning vocabulary than in examining that of intentional learning. It is believed that the effectiveness of vocabulary learning will be enhanced if students learn vocabulary incidentally. Specifically, an influential publication by Nagy, Herman, and Anderson (1985) argues that words should be learned in an incremental way since the number of words to be learned is too enormous to depend solely on explicit instruction. Hence, through incidental learning, learners can acquire most vocabulary by repeatedly encountering the words. Such beneficial effects have been disclosed in a number of studies (e.g., Kweon & Kim, 2008; Nagy, Herman, & Anderson, 1985; Paribakht & Wesche, 1999; Shu, Anderson, & Zhang, 1995; Wode, 1999), which have asserted that incidental learning accounts for a considerable proportion of the vocabulary growth.

In spite of the claim that vocabulary can be learned more effectively in an incidental way, incidental learning is not without criticism. One of the most seriously attacked limitations, as pointed out by Huckin and Coady (1999), is that guessing obviously takes time and thus slows down the process of reading. Guessing is effective only when the context is fully understood. To comprehend the text, learners will need a certain amount of lexical knowledge to better understand the content. To put it differently, learners can benefit from incidental learning only when they are supplied with adequate prior vocabulary knowledge.

researchers have, therefore, suggested many practical methods. Among the various methods, the use of vocabulary glossary annotations has been adopted widely. According to Nation (2001), a gloss is a short definition or synonym that is presented with the text, either in L1 or L2. As for the goal of glossary notation, Otto and Hayes (1981) defined it as “not only to acquire but also to internalize and apply the skills and strategies that enable them to be independent readers of the full range of material they encounter” (p. 18). As pointed out by Ko (2005), there are many advantages of glosses. For one thing, the provision of glosses prevents students from incorrect guessing if they have little background knowledge or contextual clues. For another, glossing helps minimize the interruption while reading. In fact, glosses function as a bridge between prior knowledge and the new information in the text. Unlike dictionaries, which may distract students’ attention from what they read, glossing can supply readers with immediate access to the definition of the unknown words. In view of these advantages, the use of gloss has prevailed over decades to assist students in reading.

Gloss comes in many different types, such as textual gloss, pictures, sound, and videos. Textual gloss, the original type of gloss is in general presented in a written form containing a brief definition or synonym. After its common use, pictorial gloss arose. Unlike textual gloss, it offers more visual stimuli by providing illustrations which represent what the glossed words mean. Shortly after the inception of pictorial gloss, with increasing interests in sound and videos, came a new form of gloss—sound and video glosses. When provided with a sound gloss, readers can hear the definition of the unknown words, whereas video gloss offers learners both visual and auditory aids. However, because of the resource availability constraints, auditory modes (sound and videos) are excluded from the present study.

Attempts to investigate the effect of textual gloss on vocabulary learning have shown that texts with gloss are more useful for vocabulary retention than texts without it (e.g., AbuSeileek, 2011; Grace, 1998, 2000; Hulstijn, Hollander, & Greidanus, 1996; Yanguas, 2009). For example, Hulstijn et al. (1996) conducted a study to compare the performance on vocabulary retention among French learners who were provided with marginal glosses (gloss located in the margin), those who were allowed to use a dictionary, and those who were supplied with nothing. They found that incidental vocabulary learning was fostered more when students were provided with the meaning of unknown words through marginal gloss or when they looked up the meaning in a dictionary than when no external information concerning

investigated in the field of incidental learning over years (e.g., Akbulut, 2007; Kost, Foss, & Lenzini, 1999; Shahrokni, 2009; Yanguas, 2009; Yeh & Wang, 2003; Yoshii, 2006; Yoshii & Flaitz, 2002). For instance, Yoshii and Flaitz (2002) made an attempt to delve into the effects of pictorial gloss by replicating Kost et al.’s (1999) study in a multimedia environment. Their study was based on Paivio’s (1971, 1991) dual coding theory, which posits that information coded both verbally (textual) and visually (pictorial) is more effective for learning than information coded singularly. Therefore, the combined effects of pictorial gloss and textual gloss were also investigated. Their findings, which were in line with those of Kost et al.’s study, showed that the combination group (annotations with text and picture) significantly outscored the text-only or picture-only group on both the immediate and delayed vocabulary tests. This study, therefore, lent some support to the dual coding theory.

In addition to Paivio’s (1971, 1991) theory, Mayer’s (1997) generative theory of multimedia learning was also the theoretical foundation of the above-mentioned studies. Mayer claims that learners engage in selecting, organizing, and integrating any visual and verbal information from what they see. Learners can thus construct referential connections between two forms of mental representations—the verbal system and visual system. To be more specific, learners learn more effectively when they gain access to both visual and verbal modes elaborating on the presented materials than when there is only one mode or when there is none provided to them.

In addition, another two models—word association model and concept

mediation model—were introduced by Potter, So, Eckhardt, and Feldman (1984).

These two models contend that as a learner’s L2 proficiency increases, a developmental shift can be detected from the word association model to the concept mediation model. Specifically, when seeing a picture, lower proficient learners tend to associate it with words in their L1, and then translate it into their L2 equivalent. On the contrary, as the concept mediation model proposes, higher level learners are more inclined to make a direct association between the picture and the corresponding word in their L2. However, the two models were not supported by Potter and his colleagues’ (1984) empirical findings and therefore await further studies to confirm them.

Along with the possible effect of L2 proficiency, there is another factor that is also believed to have some effects on vocabulary learning, the length of gloss (AbuSeileek, 2011). The cited factor, gloss length, has currently caused a rising concern. A recent study, conducted by AbuSeileek in 2011, sought to not only examine the effects of the gloss in different locations of the text, but also demonstrate the effects of the number of words in glosses. The length of gloss, devised as a within-subject variable, ranged from one word to seven words in length.

All subjects thus encountered all various lengths of glossed words. At the end of the study, the researcher concluded that glosses with three to five words produced more noticeable differences than did those with one to two or six to seven words. However, the subjects in his study were undergraduates, classified as beginner to pre-intermediate EFL learners, and there was no attempt made to explore the effect of gloss on advanced learners. Recognizing such a limitation, AbuSeileek himself therefore suggested that more studies should be conducted along this line to see whether his results could be generalized to learners with higher or advanced proficiency.

Taken together, numerous studies (Akbulut, 2007; Shahrokni, 2009; Tabatabaei & Shams, 2011; Yanguas, 2009; Yeh & Wang, 2003; Yoshii, 2006; Yoshii & Flaitz, 2002) have shown that textual and pictorial glosses can better enhance incidental vocabulary learning. However, learners’ L2 proficiency level has not been examined in those studies, nor has it been incorporated in studies on gloss length. Hence, the present study is the first attempt to examine the effectiveness of picture and L2 gloss while taking into consideration the two variables, the proficiency level and the length of gloss.

Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to examine how college students at different proficiency levels perform on vocabulary retention tests when they are provided with textual and pictorial glosses in reading. The current study also aimed to explore the effect of the length of gloss on students’ performance in vocabulary recognition and retention. Specifically, the present study attempted to address the following four questions:

1. Does the gloss length affect the effectiveness of pictorial and L2 gloss on vocabulary recognition?

2. Is there a significant interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on vocabulary recognition?

3. Does the gloss length affect the effectiveness of pictorial and L2 gloss on vocabulary retention?

4. Is there a significant interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on vocabulary retention?

METHOD

ParticipantsInitially, the present study recruited 135 college students who were enrolled in

Freshmen English at one university in Taipei, Taiwan. They were from the

Department of Music, Department of Mathematics, Department of Psychology and Counseling, Department of Chinese Language and Literature, and Department of English Instruction. Prior to the main study, the participants were classified into two groups at two different proficiency levels (high and low), based on the scores of a proficiency test (i.e, Wide Range Achievement Test 4 to be described below). For the purpose of achieving a clear-cut distinction between the high and the low proficiency levels among the participants, 15 students who scored from 4.6 to 5.0 in Grade Level were excluded from the main study. Hence, the final sample consisted of 120 participants. The participants who scored below the mean in the proficiency test (M = 4.8 in Grade Level) were designated as the low-proficiency group (1 to 4.5 in Grade Level); those who scored above the mean were labeled as the high-proficiency group (5.1 to 9.2 in Grade Level). After that, they were further randomly assigned to one of the two gloss conditions (long glosses and short glosses). As such, there were four groups in total: high proficiency and long gloss (HL group), high proficiency and short gloss (HS group), low proficiency and long length (LL group), and low proficiency and short gloss (LS group). Each of the four groups contained 30 participants.

The participants’ pre-existing knowledge of the glossed words was assessed by a pretest (i.e. the definition supply test to be described below) administered prior to the formal study. The mean score was 1.20 for the HL group, 1.17 for the HS group, 0.63 for the LL group, and 0.97 for the LS group, respectively. These means were then calculated by a one-way ANOVA to further confirm whether there was a significant difference among these four groups with a significance level set at .05. The results showed no significant differences among the four groups with F(3, 116) = 2.16, p > .05, ensuring the equivalence of the four groups’ entry knowledge of the target words.

Instruments

The instruments used in the present study included: (1) a proficiency test, (2) a definition supply test, and (3) a word recognition test. Each of the four tests is described in the following.

Wide Range Achievement Test 4 (WRAT-4)

A subtest of the norm-referenced Wide Range Achievement Test 4 (WRAT-4) (Wilkinson & Robertson, 2006), the green form of the sentence comprehension test was administered. The purpose was to determine the participants’ proficiency levels and to divide them into the high and low proficiency groups. WRAT-4 comprises four subtests—word reading, sentence comprehension, spelling, and math computation. In the latest edition, the interpretation of scores has been improved by the inclusion of grade-based norms. With the addition of the grade-based norms and the extension of age, the usefulness of the test is proper for students in grades K-12 and test takers aged from 5 to 94. Among the four subtests, only sentence comprehension was adopted in the current study due to the fact that the other three subtests measure other irrelevant skills, such as spelling and mathematical ability. The green form of the sentence comprehension test consisted of 50 items, listed in an ascending order of difficulty and based on a modified cloze format. Test takers were required to fill in the blanks to complete the sentences. For example, after reading the sentence “She took off her coat because she felt too __________,” test takers should fill in an appropriate word or two at most for the sentence to make sense. The possible answers provided in the test manual were hot and warm. Although it was suggested that test takers should give oral responses, the participants in the present study were asked to write down the answers due to the time constraints for testing each of the participants. In addition, giving written responses may reveal the participants’ English proficiency more faithfully because students in Taiwan learn English predominantly through reading and writing rather than through listening and speaking. Each item of the test was scored one point. Thus, the maximum possible total score was 50 for the 50 items. According to the manual, the median internal consistency reliability coefficients of this subtest were reported to be .93 for age group and .90 for grade level, respectively.

Definition Supply Test

The pre-existing knowledge test of the target words was given to the participants before the reading task began. The purpose of this test was to make sure that the participants had no knowledge of the 18 target words. The test contained 18 target words and 10 additional words to distract their full attention from the target words (see Appendix A). The 10 words were extracted from the list of 7,000 vocabulary items suggested by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan for college entrance examination. Those words (such as bruise and corridor) were selected because they were closely related to the content of the reading passage. The test was administered in the format of a production task, where the participants were instructed to put a cross mark next to any word they knew and provide an explanation either in L1 or L2. The 10 additional words were included to divert their attention and therefore were not given any points for correct answers. Each correct answer for the 18 target words in this section was awarded one point. Thus, the maximum possible total score for the definition supply test was 18 (the additional 10 words were excluded).

Word Recognition Test

The word recognition test, in a matching format, was designed to assess the participants’ ability to recognize the target words. It contained all 18 target words on the left-hand side, functioning as item stems. The participants had to choose the corresponding definitions out of 23 alternatives on the right-hand side. The definitions in the test were paraphrased so that they were different from the way they have been presented in the reading task. Prior to the administration of the test, the revised version of those definitions was examined by a native speaker. Both the immediate (see Appendix B) and the delayed tests (see Appendix C) were in the same format. The only difference between the two tests was that the order of the stems in the delayed test was different from that in the immediate test to avoid memorization of the answers. The maximum possible total score for the recognition test was 18. The reliability estimates (Cronbach’s α) for scores on the recognition test were .89 and .90 for the immediate and the delayed tests, respectively.

One thing to note is that the pretest and the immediate /delayed test differed in terms of item formats. The reason for adopting different formats was twofold. For one thing, if the matching format had been used in the pretest, the students would have obtained too many clues from the provided definitions of the glossed words.

Hence, it might have influenced the results of the present study. For another, the students might have had a practice or memory effect if the same format had been used for both the pretest and the immediate test.

Reading Material and Target Words

The article, “11-year-old Survivor of Floodwaters Saves Her Family,” extracted from Reader’s Digest online, was used as the main reading passage (Jones, 2009). This article was an amazing survival story about a brave 11-year-old girl who stayed calm when the whole family got trapped in an SUV, a car, which was lodged in a logjam in a creek. Without her courageous behavior, the car would have been engulfed by the swelling torrents and the whole family (including her mother and two toddlers) would have drowned. This authentic article was chosen because in extensive reading, it has been suggested that authentic materials should be employed (Berard, 2006; Walmsley, 2011). Furthermore, the magazine, Reader’s Digest, is targeted for the general public and it includes real-life texts that were not written for ESL/EFL purposes.

The selection of glossed words was based on the following criteria. First of all, the results of a pilot study were taken into consideration. In the pilot study, 12 students were recruited and requested to mark the words that they considered difficult or unknown. After that, whether or not those unknown words could be concretely drawn was the second selection criterion. For example, most action verbs and concrete nouns (such as submerge and torrent) were suitable to be glossed because they could be vividly illustrated. As for unknown words (such as foster and

gaping) that could not be illustrated, they were paraphrased or replaced by

synonyms, as suggested by Bell and LeBlanc (2000). At the same time, these modifications were further checked by the same native English speaker, who is a lecturer at the university. After modification, the readability of the text was calculated by the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Readability Formula, which has been proved to be fundamentally valid for a broad spectrum of English readers that includes non-native and native readers as well (Greenfield, 2004). The final text was reduced in length from 996 words to 963 words, with a 5.3 on the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Readability Formula, suggesting that fifth graders in the U.S. could read and understand the text. Based on the results of the proficiency test, the average Grade Level of all the participants was 4.8. Therefore, the readability index (5.3) of

In the present study, short glosses ranged from one to three words, whereas long glosses, were from seven to ten words. Furthermore, the L2 definitions were based on two dictionaries, The American Heritage Dictionary (2001) and Oxford Learner’s

Pocket Dictionary (1991), which have been used by Akbulut (2007) and Shahrokni

(2009), respectively. To meet the requirements of the gloss length, the same native speaker was invited again to revise and refine the definitions so that all the glosses were of the proper length, except for the word, diameter, which was explained in four words as “measurement across a circle.” As for the pictures, they were extracted from the Internet. The textual plus pictorial gloss was provided in an additional sheet instead of at the bottom or in the margin because pictures tend to take up lots of space. Annotated words were given in bold and were numbered.

Procedures

The present study was made up of two phases. One was the pilot study and the other was the main study. Each of the phases is described in the following sections.

Pilot Study

Prior to the main study, a pilot study was conducted on 12 college freshmen (six low-proficiency and six high-proficiency students). The purposes of the pilot study were threefold. First, it was conducted to identify the potential difficulties that might be encountered in the main study. Second, the amount of time for the administrations of tests could be estimated. Finally, it was conducted to choose the target words to be glossed.

The procedures of the pilot study were illustrated in the following. Twelve freshmen were instructed to take a pretest on the target words and then to read the given text. While reading, they also needed to underline the words that were unfamiliar to them. The words that were highlighted by more than half of the students were taken into consideration as the target words for gloss in the main study. After reading the text, they answered the comprehension questions, followed by the immediate vocabulary retention test. The amount of time taken for the tests and the reading task was also recorded. Upon completion of the reading task, they were invited to give comments and feedback on the appropriateness and clarity of the textual definitions of the 18 target words. Their comments on the tests were adopted for further revisions of the tests. An example of their comments that were adopted was that the matching items should be put in the box, as shown in Appendix C, to enhance the neatness of the layout.

Main Study

The main study was conducted in a three–week period, as indicated in Table 1. In the first week, a pretest (the definition supply test, see Appendix A) on the glossed words was administered to test the participants’ existing knowledge of the target words. After the pretest, they were instructed to read the text and then complete the reading comprehension questions. The short glosses were provided to the HS and the LS groups while the long glosses were given to the HL and the LL groups in reading the text. After the reading task, the participants then took the immediate vocabulary test (the recognition test, see Appendix B), which they had no prior knowledge of. Two weeks later, the delayed vocabulary test (the recognition test, see Appendix C) was then administered.

Table 1 Procedures of the Main Study The first week (One hour)

- Pretest (10 minutes)

- Reading Task + Reading comprehension questions (35 minutes) - Immediate vocabulary test (15 minutes)

The third week (15 minutes)

- Delayed vocabulary test (15 minutes)

Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed by using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 17.0. For the purpose of answering the first to the fourth research questions, a two-way-mixed-design ANOVA was conducted, where proficiency level and gloss length were the between-subjects factors and the vocabulary test was the within-subjects factor. Both the gloss length (long vs. short) and the proficiency level (high vs. low) had two levels. The within-subjects factor, the vocabulary tests, included the pretest, the immediate and the delayed tests.

RESULTS

Main Effect of Gloss Length on Vocabulary Recognition (Pretest vs. Immediate)

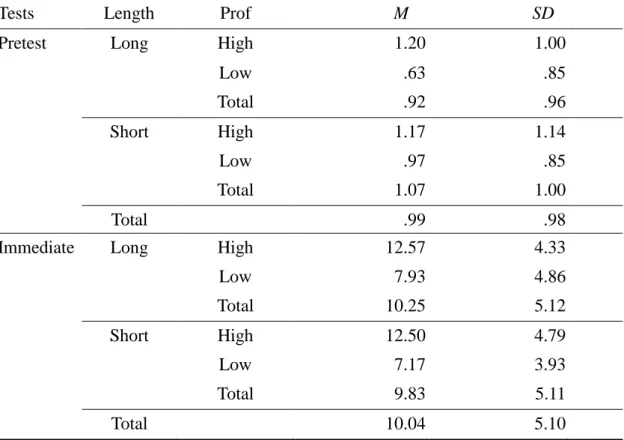

For the purpose of addressing the main effect of gloss length on vocabulary recognition, a two-way-mixed-design ANOVA was conducted, with gloss length (long vs. short) as one of the between-subjects factors and recognition as the within-subjects factor. Recognition referred to the gain score, that is, the total score on the posttest minus the total score on the pretest. In other words, it was operationally defined as the difference in scores between the pretest and the immediate test in the present study. As shown in Table 2, the result failed to reveal a significant difference in recognition between the long and the short gloss length groups (F(1, 116) = .08, p > .05). That is, gloss length did not have a significant effect on vocabulary recognition. Specifically, the means and standard deviations of the performance for the long- and the short-gloss participants on vocabulary recognition are revealed in Table 3. For the participants with the long glosses, they performed better on the immediate test (M = 10.25, SD = 5.12) than on the pretest (M = .92, SD = .96). Likewise, for the participants with the short glosses, they also obtained a higher score on the immediate test (M = 9.83, SD = 5.11) than on the pretest (M = 1.07, SD = 1.00). The gain score of 9.33 for the participants receiving the long glosses appeared to be slightly larger than that of 8.76 for those receiving the short glosses. However, the difference (i.e., .57) in the gain scores between those receiving the long glosses and those receiving the short glosses turned out to be statistically insignificant. That is, the length of glosses was not found to significantly influence the participants’ vocabulary recognition.

Table 2 Summary of the ANOVA in the Mixed Design for Overall Score Source SS df MS F p Between Group 5673.73 6 Prof 432.02 1 432.02 35.06 .00* Length 1.07 1 1.07 .08 .77* Prof x Length .42 1 .42 .03 .85* (between factor)

Test (within factor) 4914.15 1 4914.15 558.66 .00*

Test x Prof 317.40 1 317.40 36.08 .00*

Test x Length 4.82 1 4.82 .55 .46*

Test x Prof x Length 4.27 1 4.27 .49 .49*

Within Group 2449.80 232

Block 1429.43 116 12.32

Residual 1020.37 116 8.80

Total

Note. *p < .05.

Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of the Pretest and the Immediate Vocabulary Test Tests Length Prof M SD

Pretest Long High 1.20 1.00

Low .63 .85 Total .92 .96 Short High 1.17 1.14 Low .97 .85 Total 1.07 1.00 Total .99 .98

Immediate Long High 12.57 4.33

Low 7.93 4.86 Total 10.25 5.12 Short High 12.50 4.79 Low 7.17 3.93 Total 9.83 5.11 Total 10.04 5.10

Interaction Effect between Gloss Length and Proficiency Level on Vocabulary Recognition (Pretest vs. Immediate)

The second research question aimed at exploring the interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on vocabulary recognition. A two-way-mixed-design ANOVA was conducted with the vocabulary tests (the pretest and the immediate test) as the within-subjects factor and proficiency level (high vs. low) and gloss length (short vs. long) as the between-subjects factors. As shown in Table 2, the interaction effect between proficiency level and gloss length on vocabulary recognition was not statistically significant (F(1, 116) = .03, p > .05). The effect of gloss length on vocabulary recognition did not vary depending on the learners’ English proficiency level. That is, whatever proficiency level the learners were at, the effect of gloss length on their vocabulary recognition remained the same.

Main Effect of Gloss Length on Vocabulary Retention (Immediate vs. Delayed)

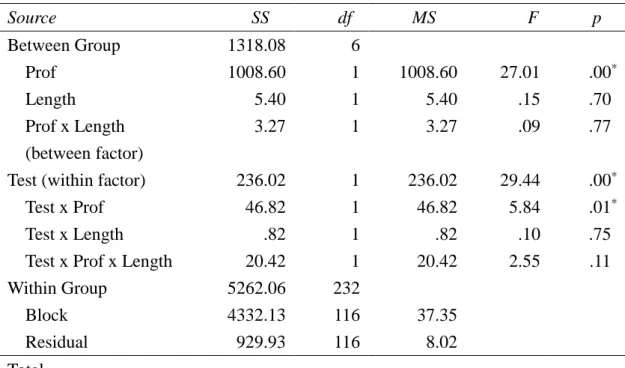

For the purpose of answering the third research question, which examined the main effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention, a two-way-mixed-design ANOVA was conducted, with gloss length (long vs. short) as one of the between-subjects factors and retention as the within-subjects factor. Retention referred to the ability to retain the meaning of a word after a given period of time. In the present study, it was operationally defined as the difference between the delayed and the immediate tests. As can be seen in Table 4, the result failed to reveal a significant difference in vocabulary retention between the long- and the short-gloss groups (F(1, 116) = .15, p > .05). Gloss length did not have a significant effect on vocabulary retention. Table 5 displays the mean scores and standard deviations in terms of the immediate and the delayed tests for the long and the the short gloss length groups. For the participants with the long glosses, they obtained a lower score on the delayed test (M = 8.15, SD = 4.65) than on the immediate (M = 10.25, SD = 4.59). Likewise, as for the participants with the short glosses, they had a lower score on the delayed test (M = 7.97, SD = 5.35) than on the immediate test (M = 9.84, SD = 4.36). The difference of 2.10 in the long-gloss participants’ retention between the immediate and the delayed tests tended to be slightly larger than that (difference of 1.87) for those with the short glosses. However, the difference between 2.10 and 1.87 was not significant, indicating that gloss length had a trivial influence on vocabulary retention.

Table 4 Summary of the ANOVA in the Mixed Design for Overall Score Source SS df MS F p Between Group 1318.08 6 Prof 1008.60 1 1008.60 27.01 .00* Length 5.40 1 5.40 .15 .70* Prof x Length 3.27 1 3.27 .09 .77* (between factor)

Test (within factor) 236.02 1 236.02 29.44 .00*

Test x Prof 46.82 1 46.82 5.84 .01*

Test x Length .82 1 .82 .10 .75*

Test x Prof x Length 20.42 1 20.42 2.55 .11*

Within Group 5262.06 232

Block 4332.13 116 37.35

Residual 929.93 116 8.02

Total

Note. *p < .05.

Table 5 Descriptive Statistics of the Vocabulary Tests (Immediate vs. Delayed) for

Long and Short Length Groups

Immediate Delayed

Length M SD M SD

Long 10.25 4.59 8.15 4.65

Short 9.84 4.36 7.97 5.35

Interaction Effect between Gloss Length and Proficiency Level on Vocabulary Retention (Immediate vs. Delayed)

The fourth research question focused on the interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on vocabulary retention. A two-way-mixed-design ANOVA was conducted with the vocabulary tests (the immediate and the delayed tests) as the within-subjects factor and proficiency level (high vs. low) and gloss length (short vs. long) as the between-subjects factors. As demonstrated in Table 4, the interaction effect between proficiency level and gloss length on vocabulary retention was not statistically significant (F(1, 116) = .09, p > .05). The effect of

DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The aims of the present study were to examine the main effect of gloss length on vocabulary recognition and vocabulary retention. Significant effects were expected prior to conducting the present study. Surprisingly, it turned out that no significant main effect was found for gloss length on either vocabulary recognition (F(1, 116) = .08, p > .05) or vocabulary retention (F(1, 116) = .15, p > .05). One plausible explanation for failing to find the significant main effect might be memory constraints. As noted by Craik and Lockhart (1972), “the subject processes the material in a way compatible with or determined by the orienting tasks” (p. 677). The participants knew that they would be tested on their reading comprehension but had no prior knowledge of the subsequent vocabulary tests on the glossed words. The participants, therefore, might strengthen their memory trace by rehearsing only the required information about the reading text in their working memory and then further reconstruct into mental representations. As such, without paying as much attention to those glossed words as they did to the reading text, it would be likely for the present study to have failed to find a significant main effect of gloss length.

Another possible explanation for these findings is that the participants in the present study might have attended to the pictorial glosses more than to the textual glosses. That is, the results might have been influenced by the participants’ learning styles. Just as pointed out by Yeh and Wang (2003), Taiwanese EFL learners showed a strong preference for visual stimuli. It was likely that the participants in the present study had tried to memorize the meaning of the new words by processing the pictures instead of the textual gloss. If the participants had attended more to the pictures than to the textual definitions, it was likely that they had difficulty in recalling the L2 definitions when taking the immediate and the delayed tests, where they were asked to match the appropriate meaning with the target words. As Taylor (2006) commented in his meta-analysis, where studies adopted traditional or CALL (Computer-Assisted Language Learning) glosses were analyzed, pictorial aides placed next to textual gloss might be interesting to the learners. However, even with the pictorial aids, the textual glosses tended not to last for a long period if comprehension was their primary aim.

As for the insignificant interaction effects found on both vocabulary recognition (F(1, 116) = .03, p > .05) and vocabulary retention (F(1, 116) = .09, p > .05), one plausible explanation is the participants’ linguistic competence. Due to the fact that learners’ limited L2 linguistic competence may pose an obstacle to their comprehension of a text, even when the low-proficiency participants were aided

with either long or short glosses in reading, the 18 target words still appeared difficult for them. On the other hand, given that the high-proficiency participants had a good command of English, they might tend to perform better than their low-proficiency counterparts regardless of whatever gloss length they were provided with.

One final point worth noting is that the results of the present study did not lend support to the word association model and concept mediation model proposed by Potter, So, Eckhardt, and Feldman (1984), who elucidated that the effectiveness of glosses may vary depending on learners’ proficiency levels. These two models were not supported by the results of the present study, where no significant interaction effect was found between proficiency level and gloss length. Hence, the tenability of these two models needs to be further examined.

Based on the results of the current study, the conclusions pertinent to each of the four research questions can be drawn as follows: (1) there was no significant main effect of gloss length on vocabulary recognition, indicating that gloss length did not have a significant effect on vocabulary recognition; (2) the interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on vocabulary recognition was not significant. No matter what proficiency level the participants were at, the effect of gloss length on their vocabulary recognition remained the same; (3) there was no significant main effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention, suggesting that gloss length had trivial influence in terms of vocabulary retention; and (4) the interaction effect between gloss length and proficiency level on vocabulary retention was not statistically significant. No matter what proficiency level the learners were at, the effect of gloss length on their vocabulary retention remained the same.

Some pedagogical implications can be derived from the results of the present study for language teachers in teaching vocabulary to EFL learners. As the current study showed, the participants recognized most of the target words after reading. Thus, language teachers should provide activities to make short-term learning develop into long-term memory. Numerous activities to facilitate the effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention have been recommended. For instance, as suggested by Gairns and Redman (1986), if short glosses are to be used in the reading, such as synonym, the retention can be improved by asking students to read with those newly-learned words underlined and supplied with two definitions—one is correct and the other is incorrect. The students need to choose the synonym out of the two definitions with the contextual clues. Likewise, if long glosses are adopted in the

make an attempt to reach an agreement on their understanding of those glosses. In sum, with plenty of exposure to glosses through the aforementioned activities, they will be engaged in a deep cognitive processing, thus leading to the retention of the words.

On the other hand, the results of the present study were subject to the following limitations. To start with, the participants were recruited from one university only. It remains unknown about whether or not the results can be generalized to students from other universities in Taiwan. Moreover, if a broad range of learners at different proficiency levels can be recruited from universities located in different areas, participants can be classified to achieve a more clear-cut distinction from high and low proficiency levels than they were in the present study.

Meanwhile, the results of the present study were also subject to the types of gloss and the words selected for glossing. In the present study, all of the four groups were provided with both pictorial and textual glosses simultaneously. It remains unknown whether or not the participants attended to the pictures more than they did to the textual glosses. Besides, the words glossed in the present study may not be the key words for comprehending the text, which may reduce the effectiveness of the glosses on vocabulary retention. Hence, the generalizability of the results should be made with caution.

In addition, there were also some limitations inherent in the instruments used in the present study. First, the format of the instrument used in the present study to assess vocabulary retention was susceptible to guessing. The format of matching only requires the learners to associate the target word with another word or phrase that carries the same meaning (Read, 2000). Learners can choose the right definition inevitably by the process of eliminating or guessing. That is, students still can guess the meaning of the words without learning them. Therefore, to ascertain whether the learners know the words or not, it is suggested that future studies include a purer measure to assess the retention of words, such as a production task, which requires learners to produce the meaning of the target words either in their L1 or L2.

While the study has its limitations, it is hoped that it can provide a basis for future research along this line. Several directions for future research are recommended in the following paragraphs.

First of all, this study was conducted in an attempt to find out the effect of gloss length on learners’ performance on vocabulary retention across only two proficiency levels (high vs. low). Future research is needed to address the issue by recruiting a larger sample size to extend our understanding of the effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention of Taiwanese students with various levels of L2 proficiency. Besides, as mentioned above, if a larger number of learners can be recruited, the

issue of whether learners pay more attention to the pictures than to the textual gloss can be closely examined by including additional groups provided with textual glosses only.

A further concern regarding the reading text is that due to the constraint of scope, only one reading text was used in the present study. A large body of literature has found that both the rhetorical organization and the topic of a reading text can affect learners’ comprehension (Carrell, 1984, 1987; Lee, 1986). Given that only narrative was used in the present study, it remains unknown about whether its results can be generalized to different rhetorical modes. Hence, future research should be conducted to further probe into the effect of gloss length on learners’ performance on reading comprehension across different types of rhetorical modes or topics.

Moreover, a comprehensive study about the effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention could not possibly be carried out if it did not incorporate a wide range of testing techniques or item formats tapping the constructs concerned. As noted by Wolf (1993), “different assessment tasks yield different, and not necessarily comparable results” (p.475). Different item formats or testing devices may yield different results from learners. For example, the format of production, a more demanding task than recognition, requires learners to go through deep, elaborative processing to produce their own answers either in their L1 or L2. The retention of vocabulary can be assessed by asking learners to offer the definition of the word. As such, it eliminates the possibility of guessing. Hence, future studies should employ different types of item formats or testing techniques to explore the effect of gloss length on vocabulary retention. It is also unclear which glosses the participants paid more attention to—the pictorial glosses or the textual glosses. Hence, it is suggested that some follow-up interviews be made or comprehensive questionnaires be distributed to get a clear picture about which kind of gloss participants think can offer the most immediate assistance.

On the whole, future research following these suggestions may help gain more insights into the effect of gloss length in the field of L2 vocabulary learning. In addition, it may also help researchers draw clear conclusions about the effect of gloss length on L2 vocabulary learning, thus guiding instructors and material designers towards pedagogically sound practices.

Akbulut, Y. (2007). Effects of multimedia annotations on incidental vocabulary learning and reading comprehension of advanced learners of English as a foreign language. Instructional Science, 35, 499-517.

August, D., Carlo, M., Dressler, C., & Snow, C. (2005). The critical role of

vocabulary development for English language learners. Learning Disabilities

Research & Practice, 20(1), 50-57.

Baleghizadeh, S., & Golbin, M. (2010). The effect of vocabulary size on reading comprehension of Iranian EFL learners. Linguistic and Literary Broad

Research Innovation, 1(2), 33-46.

Berard, S. A. (2006). The use of authentic materials in the teaching of reading. The

Reading Matrix, 6(2), 60-69.

Bell, F. L. & LeBlanc, L. B. (2000). The language of glosses in L2 reading on computer: Learners’ preferences. Hispania, 83(2), 274-285.

Carrell, P. L. (1984). The effects of Rhetorical organization on ESL readers. TESOL

Quarterly, 18(3), 441-469.

Carrell, P. L. (1987). Content and formal schemata in ESL reading. TESOL

Quarterly, 21(3), 461-481.

Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A Framework for Memory Research, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 671-684.

Gairns, R., & Redman, S. (1986). Working with Words. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. (2002). Teaching and researching in reading. London: Pearson Longman.

Grace, C. (1998). Retention of word meanings inferred from context and sentence-level translations: Implications for the design of beginning level CALL software. Modern Language Journal, 82, 533-544.

Greenfield, J. (2004). Readability Formulas for EFL. JALT Journal, 26(1), 5-24. Huang, T. L. 黃自來 (1997). 談加強字彙教學之必要性. The Proceedings of the

3rd International Symposium on English Teaching (pp.159-167). Taipei: Crane

Publishing Co.

Huckin, T., & Coady, J. (1999). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 181-193.

Hulstijn, J. H. (2001). Intentional and incidental second language vocabulary learning: A reappraisal of elaboration, rehearsal and automaticity. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognitive and second language instruction (pp. 258-286). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hulstijn, J. H., Hollander, M., & Greidanus, T. (1996). Incidental vocabulary learning by advanced foreign language students: The influence of marginal glosses, dictionary use, and reoccurrence of unknown words. The Modern

Language Journal, 80, 327-339.

Jones. T. (2009, April). 11-year-old Survivor of Floodwaters Saves Her Family. Reader’s Digest, Retrieved from

http://www.rd.com/true-stories/survival/11yearold-survivor-of-floodwaters-sa ves-her-family/

Ko, M. H. (2005). Gloss, comprehension, and strategy use. Reading in a Foreign

Language, 17(2), 125-143.

Kost, R., Foss, P., & Lenzini, J. J. (1999). Textual and pictorial glosses: Effectiveness on incidental vocabulary growth when reading in a foreign language. Foreign Language Annals, 32(1), 89-113.

Kruse, A. F. (1979). Vocabulary in context. ELT Journal, 33(3), 207-213.

Kweon, S. O., & Kim, H. R. (2008). Beyond raw frequency: Incidental vocabulary acquisition in extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 20(2), 191-215.

Lee, J. F. (1986). Background knowledge and L2 reading. The Modern Language

Journal, 70(4), 350-354.

Lee, S. Y. (2006). A one-year study of SSR: University level EFL students in Taiwan.

The International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 2(1), 6-8.

Manser, M. H. (Ed.). (1991). Oxford learner’s pocket dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (1997). Multimedia learning: Are we asking the right questions?

Educational Psychologist, 32(1), 1-19.

Nagy, W. E., Herman, P. A., & Anderson, R. C. (1985). Learning words from context.

Reading Research Quarterly, 20, 233-253.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Otto, W., & Hayes, B. (1981). Glossing for improved comprehension: Progress and prospect. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Reading Forum (2nd, Satasta, FL, December 10-12, 1981).

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and verbal processes. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Pickett, J. P. (Ed.). (2001). The American heritage dictionary. New York: Dell Publishing Company.

Potter, M. C., So, K., Eckardt, V., & Feldman, L. B. (1984). Lexical and conceptual representation in beginning and proficient bilinguals. Journals of Verbal

Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23(1), 23-38.

Read, J. (2000). Assessing Vocabulary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shahrokni, S. A. (2009). Second language incidental vocabulary learning: The effect

of online textual, pictorial, and textual pictorial glosses. The Electronic

Journal for English as a Second Language, 13(3), retrieved from

http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volumes13/ej51/ej51a3

Sheu, S. (2003). Extensive reading with EFL learners at beginning level. TESL

Reporter, 3(2), 8-26.

Sheu, S. (2004). The effects of extensive reading on learners' reading ability development. Journal of National Taipei Teachers College, 17(2), 213-228. Shu, H., Anderson, R. C., & Zhang, H. (1995). Incidental learning of word meanings

while reading: A Chinese and American cross-cultural study. Reading Research

Quarterly, 30(1), 76-95.

Smith, K. (2011). Integrating one hour of in-school weekly SSR: Effects on proficiency and spelling. The International Journal of Foreign Language

Teaching, 7(1), 1-7.

Tabatabaei, O., & Shams, N. (2011). The effect of multimedia glosses on online computerized L2 text comprehension and vocabulary learning of Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(3), 714-725.

Taylor, A. (2006). The effects of CALL versus traditional L1 glosses on L2 reading comprehension. CALICO Journal, 23(2), 309-318.

Walmsley, M. (2011, April). Automatic Glossing for Second Language Reading. Paper presented at the 9th New Zealand Computer Science Research Student

Conference (NZCSRSC). Abstract retrieved from

http://flax.nzdl.org/reader/files/Walmsley_NZCSRSC_2011.pdf

Wang, X. W. (2012). 台灣區代表發布「2010 年台灣與國際產學英語能力差距報 告」。TOEICNewsletter, 27,16-21。取自

http://www.toeic.com.tw/file/12045015/pdf

Wilkinson, G. S., & Robertson, G. J. (2006). WRAT4 Wide Range Achievement Test

Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Wode, H. (1999). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 243-258.

Wolf, D. F. (1993). A comparison of assessment tasks used to measure FL reading comprehension. Modern Language Journal, 77(4), 473-489.

Wu, H. Y., & Hu, P. (2007). Major factors influencing reading comprehension: A factor analysis approach. Sino-US English Teaching, 4(9), 14-19.

Yanguas, I. (2009). Multimedia glosses and their effect on L2 text comprehension and vocabulary learning. Language Learning and Technology, 13(2), 48-67. Yeh, Y., & Wang, C. W. (2003). Effects of multimedia vocabulary annotations and

learning styles on vocabulary learning. CALICO Journal, 21(1), 131-144. Yoshii, M., & Flaitz, J. (2002). Second language incidental vocabulary retention:

The effect of text and picture annotation types. CALICO, 20(1), 33-58. Yoshii, M. (2006). L1 and L2 glosses: Their effects on incidental vocabulary

APPENDIX A

Definition Supply Test

Instructions: Please put an “X” in the box if you know that word, and write the meanings either in English or Chinese.

[ ] huddle _____________________ [ ] corridor ____________________ [ ] torrent _____________________ [ ] submerge __________________ [ ] prickly _____________________ [ ] dumbfounded________________ [ ] roar _______________________ [ ] brake______________________ [ ] windshield _________________ [ ] circuit _____________________ [ ] hoist ______________________ [ ] logjam _____________________ [ ] silhouette __________________ [ ] bruise _____________________ [ ] diameter ___________________ [ ] haul _______________________ [ ] altitude ____________________ [ ] cinch ______________________ [ ] flimsy _____________________ [ ] thermometer ________________ [ ] sprawl _____________________ [ ] toddler _____________________ [ ] reunion ____________________ [ ] culvert _____________________ [ ] sway ______________________ [ ] porch ______________________ [ ] clutch _____________________ [ ] assault _____________________

APPENDIX B

Immediate Word Recognition Test

Instructions: Please match the words in the left column with the correct meaning on the right-hand side.

__ submerge __ toddler __ logjam __ hoist __ huddle __ clutch __ diameter __ dumbfounded __ flimsy __ windshield __ torrent __ culvert __ brake __ prickly __ porch __ cinch __ haul

[A] to raise something up to a higher position

[B] a strong and fast-moving stream of water or other liquid [C] to go below the surface of an area of water

[D] a piece of transparent material fixed at the front of cars [E] a device for slowing or stopping a moving car

[F] a crowded mass of logs blocking a river [G] a pipe for steam or vapor to release

[H] badly made and not strong enough for the purpose for which it is used

[I] the dark shape and outline of someone or something [J] unable to speak because of surprise

[K] to be held on the surface of liquid [L] to gather closely in a group or in a pile [M] to pull with effort or force

[N] a straight line going from one side of a circle to the other side, passing through the center

[O] measurement from bottom to top

[P] covered with sharp-pointed stuff on the skin of plants [Q] a tunnel that carries a river or a pipe for water under a road [R] to grasp something very tightly

[S] to fasten something tightly around one’s waist [T] device in a car for speeding up

[U] a small area at the entrance of a building that is covered by a roof

APPENDIX C

Delayed Word Recognition Test

Instructions: Please match the words in the left column with the correct meanings on the right-hand side.

__ huddle __ clutch __ logjam __ prickly __ silhouette __ culvert __ diameter __ dumbfounded __ porch __ windshield __ brake __ torrent __ hoist __ toddler __ flimsy __ cinch __ haul __ submerge

[A] a pipe for steam or vapor to release [B] to gather closely in a group or in a pile

[C] a straight line going from one side of a circle to the other side, passing through the center

[D] a piece of transparent material fixed at the front of cars [E] a device for slowing or stopping a moving car

[F] to pull with effort or force

[G] a child who is just beginning to walk

[H] badly made and not strong enough for the purpose for which it is used

[I] to raise something up to a higher position [J] unable to speak because of surprise

[K] to be held on the surface of liquid

[L] the dark shape and outline of someone or something [M] to go below the surface of an area of water

[N] device in a car for speeding up [O] measurement from bottom to top

[P] covered with sharp-pointed stuff on the skin of plants [Q] a crowded mass of logs blocking a river

[R] to grasp something very tightly

[S] to fasten something tightly around one’s waist

[T] a tunnel that carries a river or a pipe for water under a road [U] a small area at the entrance of a building that is covered by

a roof

[V] without a point or sharp edge

註釋長度與 EFL 學生英文程度對單字記憶之影響 蔡詩涵 臺北市立大學英語教學系 林文鶯 臺北市立大學英語教學系 摘要 本研究旨在探討註釋長度以及 EFL 學生英文程度對於北部一所大學 大一學生在閱讀理解能力與字彙記憶上的影響。研究對象為台灣北 部一所大學的 120 位大一學生。學生依照 WRAT-4 程度測驗的結果及 註釋的長短分為四組,分別為高能力長註釋組(HL),高能力短註 釋組(HS),低能力長註釋組(LL),和低能力短註釋組(LS)。 受試者在單字註釋的幫助之下閱讀一篇文章,並完成五題選擇題, 測驗其閱讀理解能力。接著,受試者在未事先被告知的狀態下接受 單字測驗,以配合題的方式來測驗其對於十八個註釋單字的記憶。 兩週後,受試者接受相同的單字測驗。資料分析採用完全相依設計 二因子變異數分析以探究註釋長度以及學生英文程度對於其字彙記 憶上的影響。研究結果顯示:一、註釋長度的主要效果在字彙辨認 方面也未達到顯著水準 F(1, 116) = .08, p > .05)。二、學生程 度與註釋長度的交互效果在字彙辨識上並未達到顯著水準(F(1, 116) = .03, p > .05)。三、註釋長度的主要效果在單字記憶方面 也未達到顯著水準(F(1, 116) = .15, p > .05)。四、學生程度與 註釋長度的交互效果在單字記憶上並未達到顯著水準(F(1, 116) = .09, p > .05)。本研究最後並提供對英語教學之應用,以及對未 來研究的建議。 關鍵字:註釋長度、英文程度、單字記憶