企業管理碩士班學術英文課程與教學個案研究:以台灣某科技大學為例 - 政大學術集成

322

0

0

全文

(2) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(3) A Case Study on EAP Curriculum and Instruction in Graduate Business Administration Programs in Taiwan. A Dissertation Presented to Department of English. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. National Chengchi University. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. i n U. Ch. v. e nFulfillment In Partial gchi of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Ginger Mei-ying Lin July, 2011.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(5) Dedicated in fond memory to. Professor Cynthia Hsin-feng Wu and Beloved Friend Daniel Trausch 1956-2009. 1977-1998. 獻給恩師吳信鳳教授 暨 摯友 Daniel Trausch 喬大年 1956-2009. 立. 1977-1998. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(6) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(7) Acknowledgements. My greatest appreciation and profoundest gratitude goes first and foremost to my advisors, Prof. I-li Yang and Prof. Shih-guey Joe, for their long-lasting encouragement and guidance. Over the years, Prof. Yang has been constantly providing me with her expertise and patience. She took me under her caring wing when I entered the Graduate Institute of Linguistics at National Chengchi University. Through her guidance, I have not only gained extensive knowledge but also valuable lessons in. 政 治 大 extensive comments on the drafts of this dissertation. Prof. Joe has not only inspired 立 and guided me into the field of ESP, but also offered tremendous support for my many regards of life. She has also expended enormous time and effort to make. ‧ 國. 學. research. My gratitude also goes to the committee members: Dr. Richard Jenn-Rong Wu, Dr. Peng Chin-ching, and Dr. Yi-Ping Huang. They provided invaluable. ‧. comments which have enabled me to make a refined revision. Through their dedication, thoroughness, and persistence, the completion of this dissertation has. sit. y. Nat. become a reality.. er. io. This research would not have been possible without the generous support of Dr.. al. v i n observation which made this research C h possible. ThanksUare also due to the teacher i My warmest thanks further e n ginchish class. who allowed me to distribute questionnaires n. A and Dr. B in the targeted graduate programs. They submitted to my interviews and. go to the questionnaire respondents and student interviewees, especially Allen Chou. I also wish to express my gratitude to those who had helped me during the pilot tests, especially Ethan Liu, Catherine Huang, and Elbert Lan. I would like to express my thanks to all the professors who had taught me during my studies at National Chengchi University. My sincerest gratitude goes to Prof. Po-ying Lin who built a solid academic foundation for me. Without her detailed guidance and love in the past years, I could not have reached this culminating achievement. I would also like to thank Dr. Cynthia Hsin-feng Wu. Although she has left us, her enthusiasm and passion for teaching and research will always remain in my heart.. iv.

(8) My gratitude also goes to my classmates who constantly encouraged me on this long journey of pursuing my Ph.D. degree. Lucy Tsai, Peter Herbert, Yin-ling Chang, Cheng Hua Hsiao, and Brenda Chen accompanied me through the tough times. Thanks also to friends who helped in finding papers and provided warmth: Esther Su, Xiao-ping Xu, and Eric Lin. I am also indebted to friends who stood by me and offered their support in so many ways. Without Amy Chien, I would never have gone on the academic journey. Andrew Starck gave me the courage to become an English teacher. Anna and Ellen have been supporting me with their friendship. Jessica Hsu, May, and Monica had led me on the journey of self-improvement and guided me to achieve my goals. Daniel Trausch and Clarence Trausch have given me the most unbelievable kind of friendship.. 治 政 大 encouragement has has been supporting me in every possible way. His everlasting 立 helped me pass through many ups and downs. He also devotes himself to overcoming My special thanks go to the most unique person in my life, Steven Rogers. He. ‧ 國. 學. obstacles which I encounter in my life, including spending endless time proofreading my drafts and solving all my problems. I cannot have come this far without his great. ‧. support.. Finally, I would like to extend my gratitude to my family: my grandfather, my. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. mother, and my youngest aunt, for their love and support.. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

(9) Table of Contents. Dedication ............................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ................................................................................................... vi List of Tables ......................................................................................................... xii List of Figures ....................................................................................................... xiv Chinese Abstract ................................................................................................... xv English Abstract ................................................................................................... xvi Chapter. 立. 政 治 大. 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1. ‧ 國. 學. Background and Motivation ...................................................................... 2 Purpose of the Study and Research Questions ............................................ 3 Delimitation of the Study........................................................................... 4. ‧. Significance of the Study ........................................................................... 4. sit. y. Nat. Definition of Terms ................................................................................... 5 Overview of the Dissertation ..................................................................... 6. io. er. 2. Literature Review ........................................................................................ 8. al. n. v i n C h ............................................................... English for Academic Purposes 13 engchi U English for General Purposes and English for Specific Purposes................ 8. Curriculum Design .................................................................................. 17 Syllabus Design ................................................................................ 17 Instructional Practices ....................................................................... 19 Collaboration/Team-Teaching Models ........................................ 19 Cultural Issues in EAP ................................................................ 20 Teaching Materials ........................................................................... 22 Program Evaluation .......................................................................... 24 Needs Analysis ........................................................................................ 25 Medium of Instruction and Content-Based Instruction ............................. 31 Summary ................................................................................................. 35 vi.

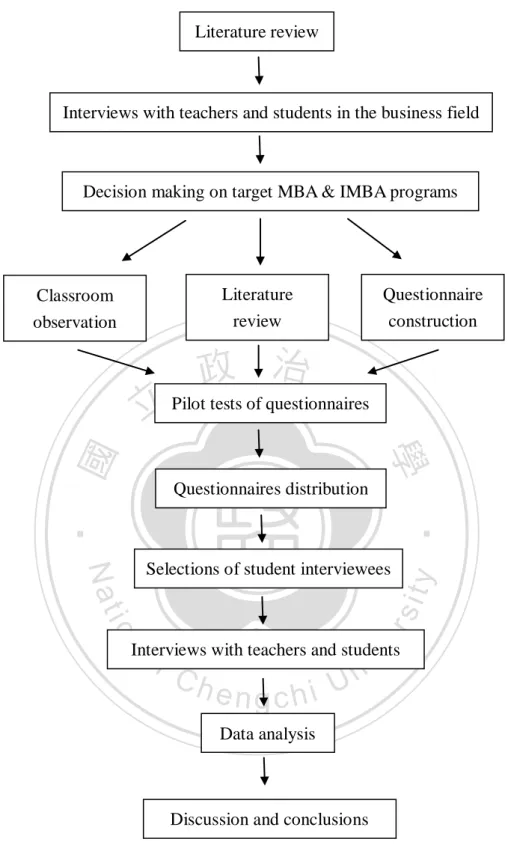

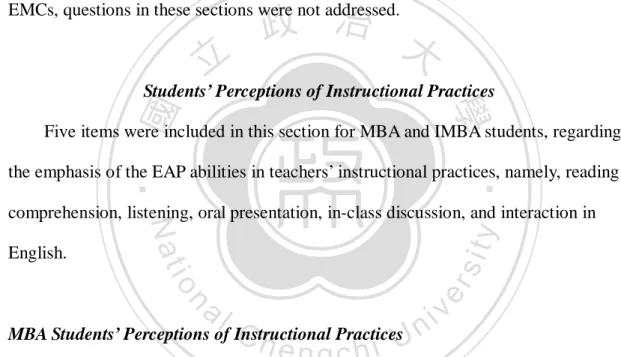

(10) 3. Methodology............................................................................................... 37 Mixed Methods Research ........................................................................ 37 Participants .............................................................................................. 38 Teachers ........................................................................................... 38 MBA Students .................................................................................. 38 IMBA Students ................................................................................. 40 Instruments .............................................................................................. 42 Quantitative Instruments ................................................................... 42 Pre-Questionnaire Construction Interviews ................................. 43 Pilot Tests and Revisions ............................................................ 43 Qualitative Instruments ..................................................................... 45. 治 政 大 Semi-Structured Interviews ......................................................... 48 立 Data Collection Procedures...................................................................... 50 Classroom Observation ............................................................... 45. ‧ 國. 學. Data Analysis .......................................................................................... 53 Quantitative Data Analysis ............................................................... 53. ‧. Qualitative Data Analysis ................................................................. 53 Summary ................................................................................................. 53. y. Nat. sit. 4. Research Findings: Quantitative Results.................................................. 55. al. er. io. Profiles of the Respondents ..................................................................... 55. n. Background Information of MBA Students ...................................... 58. Ch. i n U. v. Background Information of IMBA Students ..................................... 59. engchi. MBA Students’ Experiences of EMCs ............................................. 60 Findings of Research Question One: Perceptions of Academic Curriculum Design .................................................................................. 64 MBA Students’ Perceptions of Academic Curriculum...................... 68 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Academic Curriculum .................... 72 Findings of Research Question Two: Perceptions of Teaching in EAP Courses.................................................................................................... 74 Students’ Perceptions of Instructional Practices ............................... 75 MBA Students’ Perceptions of Instructional Practices ................ 75 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Instructional Practices .............. 76. vii.

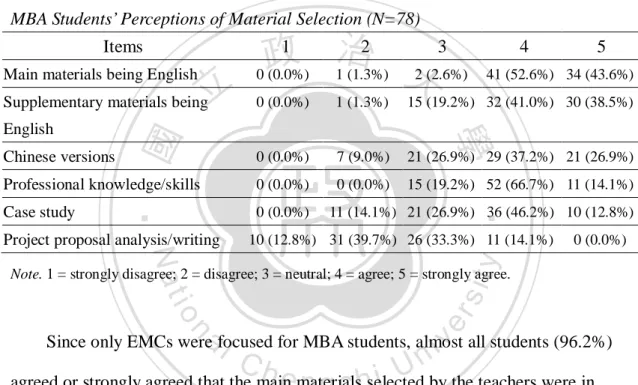

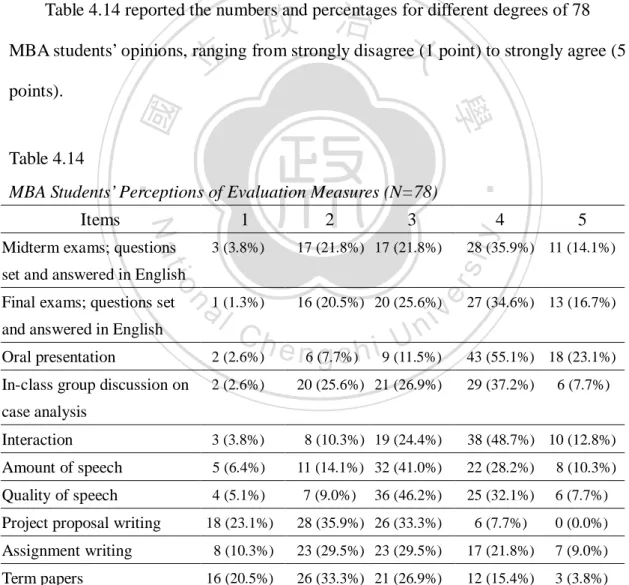

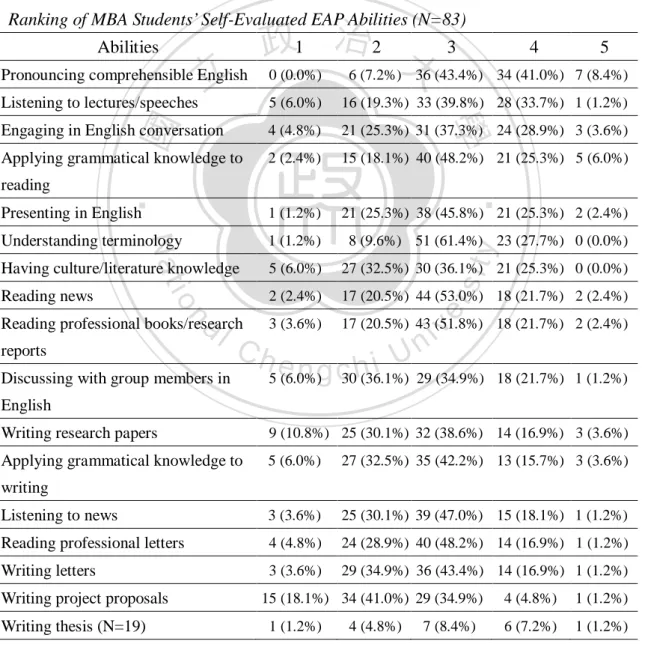

(11) Students’ Perceptions of In-Class Activities Best Facilitating EAP Abilities ........................................................................................... 77 MBA Students’ Perceptions of In-Class Activities Best Facilitating EAP Abilities .......................................................... 78 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of In-Class Activities Best Facilitating EAP Abilities .......................................................... 79 Students’ Perceptions of Material Selection ..................................... 80 MBA Students’ Perceptions of Material Selection...................... 81 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Material Selection .................... 82 Students’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures ................................. 83 MBA Students’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures.................. 83. 治 政 大 Perceptions of EAP Findings of Research Question Three: Students’ 立 Needs ...................................................................................................... 86 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures ................ 84. ‧ 國. 學. MBA Students’ Perceptions of EAP Needs ...................................... 87 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of EAP Needs ..................................... 89. ‧. Findings of Research Question Four: Students’ Self-Evaluated Abilities .. 91 MBA Students’ Self-Evaluated EAP Abilities .................................. 92. y. Nat. sit. IMBA Students’ Self-Evaluated EAP Abilities ................................ 94. al. er. io. Summary ................................................................................................. 96. n. 5. Research Findings: Qualitative Results .................................................... 97. Ch. i n U. v. Profiles of the Programs .......................................................................... 97. engchi. Profiles and Admission Requirements of the MBA Program ............ 97 Profiles and Admission Requirements of the IMBA Program ........... 99 Graduation Regulations ...................................................................101 Preparatory Courses ..................................................................101 Credits ......................................................................................102 Graduation Requirements..........................................................104 Findings of Research Question One: Perceptions of Academic Curriculum Design .................................................................................108 Teachers’ Perceptions of Academic Curriculum Design ..................108 Status Quo of EAP Implementation...........................................108 EMCs .......................................................................................114 viii.

(12) Teachers for the EMCs .............................................................116 Overseas Teacher Training Program .........................................118 Extracurricular Activities and TA System .................................123 Students’ Perceptions of Academic Curriculum Design...................124 Admission Requirements ..........................................................124 Motivations ...............................................................................126 Preparatory Courses ..................................................................128 Credits ......................................................................................129 Graduation Requirements..........................................................131 English Extracurricular Activities .............................................139 Findings of Research Question Two: Perceptions of Teaching in EAP. 治 政 大 ..............................150 Teachers’ Perceptions of Instructional Practices 立 MOI ..........................................................................................150. Courses...................................................................................................149. ‧ 國. 學. In-Class Presentation ................................................................152. Teachers’ Perceptions of Material Selection ....................................155. ‧. Teachers’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures ................................158 In-Class Presentation ................................................................158. y. Nat. sit. Written Exams ..........................................................................159. al. er. io. Participation..............................................................................161. n. Assignments .............................................................................161. Ch. i n U. v. Students’ Perceptions of Instructional Practices ..............................163. engchi. MOI ..........................................................................................164 In-Class Presentation ................................................................179 Interaction.................................................................................182 Teacher Initiation ...............................................................182 Students’ Language Proficiency .........................................186 Cultural Differences ...........................................................187 Special Ways .....................................................................188 Class Size...........................................................................189 Classroom Size ..................................................................190 Teachers’ Instructional Practices in EMCs ................................191 Students’ Perceptions of Material Selection ....................................195 ix.

(13) Language of Materials ..............................................................195 Textbooks .................................................................................197 Handouts ..................................................................................198 Computer Resources .................................................................199 Learner-Generated Materials .....................................................201 Students’ Background Experiences ...........................................203 Students’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures ................................203 In-Class Presentation ................................................................203 Written Exams ..........................................................................204 Participation..............................................................................206 Assignments .............................................................................209. 治 政 大 of Students’ EAP Findings of Research Question Three: Perceptions 立 Needs .....................................................................................................216 Students’ Evaluation of Teachers and TAs ................................213. ‧ 國. 學. Teachers’ Perceptions of Students’ EAP Needs ...............................216 Terminology .............................................................................216. ‧. Reading Skills ...........................................................................218. Oral Communication Skills .......................................................219. y. Nat. sit. Writing Skills............................................................................220. al. er. io. Culture and Literature ...............................................................221. n. Students’ Perceptions of EAP Needs ...............................................224. Ch. i n U. v. Terminology .............................................................................224. engchi. Reading Skills ...........................................................................225 Oral Communication Skills .......................................................227 English Presentation Skills ........................................................228 Journalistic English and World Views .......................................230 Writing Skills............................................................................231 Culture and Literature ...............................................................232 Findings of Research Question Four: Students’ Self-Evaluated Abilities ..................................................................................................234 Terminology .............................................................................235 Reading Skills ...........................................................................235 Oral Communication Skills .......................................................236 x.

(14) English Presentation Skills ........................................................236 Ways Students Adopted to Improve English .............................237 Summary ................................................................................................238 6. Discussion and Conclusions ......................................................................239 Summary of Major Findings and Discussion ...........................................239 Research Question One: Perceptions of Academic Curriculum Design ............................................................................................239 Research Question Two: Perceptions of Teaching in EAP Courses...........................................................................................244 Instructional Practices ...............................................................244 MOI ...................................................................................244. 治 政 大 Interaction ..........................................................................251 立 Material Selection .....................................................................253 In-Class Presentation ..........................................................248. ‧ 國. 學. Evaluation Measures .................................................................257. Research Question Three: Perceptions of Students’ EAP Needs ......260. ‧. Research Question Four: Students’ Self-Evaluated Abilities............264 Conclusions ............................................................................................265. y. Nat. sit. Pedagogical Implications ........................................................................266. n. al. er. io. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research..........................268. Ch. i n U. v. References .............................................................................................................269. engchi. Appendixes............................................................................................................284 A. MBA Questionnaire ...................................................................................284 B. IMBA Questionnaire ..................................................................................291 C. Interview Questions for Teachers ...............................................................297 D. Interview Questions for MBA Students with EMC Experiences .................298 E. Interview Questions for MBA Students without EMC Experiences ............299 F. Interview Questions for IMBA Students .....................................................300 Vita ........................................................................................................................301. xi.

(15) List of Tables. Table 2.1 Confucian and Western Values Relating to Academic Lectures ............. 21 Table 2.2 Important English Tasks Selected by NNS Graduate Students/Scholars in EFL Contexts .................................................................................... 29 Table 2.3 Difficulties of NNS Graduate Students/Scholars in Using English in EFL Contexts ........................................................................................ 30 Table 3.1 Information of MBA Interviewees ......................................................... 40 Table 3.2 Information of IMBA Interviewees ....................................................... 42. 政 治 大 Students’ Background Information ........................................................ 56 立 MBA Students’ Experiences of EMCs in the MBA Program in. Table 3.3 Classroom Observation Information ...................................................... 48 Table 4.1. 學. ‧ 國. Table 4.2. Taiwan .................................................................................................. 61 Table 4.3 Students’ Perceptions of Academic Curriculum Design ......................... 65. ‧. Table 4.4 Ranking of MBA Students’ Preference for English-Related Courses ..... 71 Table 4.5 Ranking of MBA Students’ Suggested English Extracurricular. y. Nat. sit. Support ................................................................................................. 72. er. io. Table 4.6 Ranking of IMBA Students’ Preference for English-Related Courses .... 73. al. v i n Ch Support ................................................................................................. 74 U i e h n c Instructional Practices on MBA Students’ Perceptions of g Teachers’ n. Table 4.7 Ranking of IMBA Students’ Suggested English Extracurricular. Table 4.8. EAP Abilities ........................................................................................ 76 Table 4.9 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Teachers’ Instructional Practices on EAP Abilities ........................................................................................ 77 Table 4.10 Ranking of MBA Students’ Perceptions of In-Class Activities Best Facilitating EAP Abilities ...................................................................... 78 Table 4.11 Ranking of IMBA Students’ Perceptions of In-Class Activities Best Facilitating EAP Abilities ...................................................................... 80 Table 4.12 MBA Students’ Perceptions of Material Selection ................................. 81 Table 4.13 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Material Selection ................................ 82 Table 4.14 MBA Students’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures ............................. 83 xii.

(16) Table 4.15 IMBA Students’ Perceptions of Evaluation Measures ............................ 85 Table 4.16 EAP Needs in Different Abilities Perceived by MBA and IMBA Students ................................................................................................ 87 Table 4.17 Ranking of MBA Students’ Perceptions of EAP Needs ......................... 88 Table 4.18 Ranking of IMBA Students’ Perceptions of EAP Needs ........................ 90 Table 4.19 MBA and IMBA Students’ Self-Evaluated EAP Abilities ...................... 92 Table 4.20 Ranking of MBA Students’ Self-Evaluated EAP Abilities ..................... 93 Table 4.21 Ranking of IMBA Students’ Self-Evaluated EAP Abilities .................... 95 Table 5.1 Credit Requirements of MBA and IMBA Programs..............................103 Table 5.2 EMCs Offered in MBA and IMBA in Academic Years of 2008 & 2009 .....................................................................................................104. 政 治 大. Table 5.3 Checklist for Graduation Requirements ................................................105. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiii. i n U. v.

(17) List of Figures. Figure 2.1 ESP Classification by Professional Area ................................................ 11 Figure 2.2 Continuum of ELT Course Types ........................................................... 12 Figure 2.3 Categories of English for Language Teaching Purposes ......................... 13 Figure 2.4 Sub-Divisions of EAP ........................................................................... 15 Figure 2.5 Models of CBI....................................................................................... 33 Figure 3.1 Research Procedures ............................................................................. 52 Figure 5.1 MBA Admission Procedures and Requirements ..................................... 99. 政 治 大. Figure 5.2 IMBA Admission Procedures and Requirements ..................................101. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiv. i n U. v.

(18) 國立政治大學英國語文學系博士班 博士論文提要. 論文名稱:企業管理碩士班學術英文課程與教學個案研究: 以台灣某科技大學為例 指導教授:楊懿麗 教授 研究生:林美瑩. 周碩貴 教授. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 論文提要內容:. ‧. 英語在貿易、科技等領域為當今國際交流的主要語言,更是學術界之主要溝 通媒介,在台灣高等教育亦是如此。本研究旨在探討企業管理碩士班學術英文課. sit. y. Nat. 程規劃之現況,以台灣某科技大學之企業管理所及國際企業管理所為對象,採問. io. er. 卷、課室觀察、訪談之研究方式,從教師及學生的觀點深入評析 97、98 學年度 兩所的學術英文課程規劃、實施現況、學生的學術英文需求、及學生自評之學術. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. 英文能力。從兩所學生回收的有效問卷共 98 份,篩選後的學生訪談者共 14 位。. engchi. 兩位授課教師的訪談則分別於 97、98 學年度各進行一次。問卷結果採描述性統 計加以敘述分析,課室觀察及訪談結果則以持續比較法(constant comparison method)進行分析。研究結果顯示兩所之課程規劃均注重培養教師及學生的學術 英文能力;雖教師方面含海外師訓、定期教學研討會,然全英授課課程之師資來 源為一困難。學生方面則從招生至畢業規定,均將促進語文能力納入整體課程規 劃中。教師在教學、教材選擇、評量方面均致力培養學生的學術英文能力。學生 的學術英文需求特別注重術語、讀、口語溝通、上台報告之能力,然本土文化之 知識極待加強。學生普遍自評學術英文能力普通或不佳。本研究結果為商管學術 英文課程規劃者及研究者提供了一個全面性的參考資料。. 關鍵字:學術英文、課程規劃、需求、商用英文 xv.

(19) ABSTRACT. English is the main lingua franca for international communication in fields such as business and technology; it is also the major medium in teaching and learning. This phenomenon has a significant impact on higher education in Taiwan. This. 政 治 大 curriculum design in graduate business administration programs. An MBA and an 立 study aimed to probe into the status quo of EAP (English for Academic Purposes). ‧ 國. 學. IMBA program at a national university of science and technology in Taiwan was targeted. Questionnaires, classroom observation, and semi-structured interviews. ‧. were adopted as research instruments. Teachers’ and students’ perspectives of the. sit. y. Nat. curriculum design, implementation, students’ EAP needs, and students’. io. er. self-evaluated EAP abilities in the academic years of 2008 and 2009 were. al. v i n interviewees were selected. TwoCteachers first interviewed in the academic h e nwere gchi U n. investigated. A total of 98 valid questionnaires were collected, and 14 student. year of 2008, and again in 2009, respectively. The analysis of questionnaires was conducted through descriptive statistics, while the qualitative data was analyzed by constant comparison method. Results of this study indicated that the two programs included nurturing teachers’ and students’ EAP abilities in the curriculum design. For teachers, overseas teacher training and regular teaching seminars were provided. However, finding teachers to teach English-medium courses presented a difficulty. Developing students’ language abilities was included in the overall curriculum design, from admission to graduation regulations. Teachers were committed to xvi.

(20) cultivating students’ EAP abilities in instructional practices, material selection, and evaluation. The EAP needs of terminology, reading, oral communication, and presentation abilities were particularly valued. Nonetheless, students’ knowledge of local culture needed to be strengthened. Students generally rated their EAP abilities average or below average. In sum, this study may be of importance in improving EAP curriculum design in graduate business programs in future.. Key Words: EAP, curriculum design, needs, business English. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xvii. i n U. v.

(21) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. In recent years, due to the impact of globalization and internationalization, English has become an international lingua franca. It has been reported that people around the world who speak English as a foreign or second language have. 政 治 大. outnumbered or will soon outnumber native speakers of English (Graddol, 1997 &. 立. 2000; Mackey, 2007; Warschauer, 2000). Thus, the concept of “world Englishes” has. ‧ 國. 學. been proposed. According to Mackey (2007), “the concept of ‘world Englishes’ is commonly understood as the different varieties or appropriations of English that have. ‧. developed around the world over time” (p. 12).. y. Nat. io. sit. English is the major medium which links fields among trade, science, technology,. n. al. er. and so on (Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1991; Sano, 2002; Seidlhofer, 2005; Tardy, 2004).. i n U. v. This phenomenon also has a significant impact on English instruction in general, from. Ch. engchi. elementary to higher education. It has become a trend to strengthen students’ English abilities at all levels. Crystal in 1999 reported that “at that time of publishing 85% of international organizations used English as their official language; . . . some 90% of all academic texts published in certain fields such as linguistics were in English” (as cited in Mackey, 2007, p. 14). Since English is also the major medium adopted for business, this study specifically focused on how academic English is applied in business in Taiwan. With the trend of globalization, along with the fast economic growth rising from mainland China, many businesspeople are taking interest in getting to know how to 1.

(22) conduct business with Chinese people. Taiwan also serves as the springboard and testing market for those who are interested in entering mainland China markets (Lai, 2011; The Straits Times, 2010). Moreover, more Taiwanese people are hired by foreign companies (Lai, 2011) since the official establishment of business relationship across the Taiwan Straits (BBC news, 2009).. Background and Motivation In mid-1990s, the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan started a reform in. 政 治 大 colleges of technology to be set up or restructured into institutes or universities of 立 technological and vocational higher education, allowing public and private junior. technology. The education orientation gradually turned from non-college bound (i.e.,. ‧ 國. 學. employment-oriented) to college bound. The rapid expansion of the institutes or. ‧. universities in technological and vocational higher education in Taiwan resulted in the. sit. y. Nat. needs of academic English.. io. er. Academic English or English for Academic Purposes (EAP) has been widely discussed abroad but barely touched upon in Taiwan. Its definition and its. al. n. v i n C hto most people on U implementation are largely unclear this island (Su, Chen, & Fahn, engchi. 2007; Wang & Chen, 2007). Hence, in order to gain a clear picture of the status quo of EAP in fields other than English/Foreign Departments in higher education, this study aimed to investigate how EAP is applied in the business field, as there have been more demands on the EAP abilities for graduate students in this field. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, although the needs of academic English have increased, many issues have also been raised from the rapid expansion of the institutes or universities in technological and vocational higher education in Taiwan. For instance, due to the decline in birth rate and the lowering of the threshold for admission, students may not be able to cope with academic texts in English. In 2.

(23) consequence, not many programs in fields other than English/Foreign language institutes could provide English-medium courses. Starting from November 2008, the researcher conducted interviews with many teachers and students in the business field regarding EAP curriculum design and students’ EAP abilities, as part of a National Science Council funded project (NSC 97-2410-H-255-002-MY2). Teachers and students ranging from traditional universities to universities of technology were interviewed. Along the process, it is discovered that the type of university and students’ English proficiency had great. 政 治 大 While looking for qualified interviewees, the researcher discovered that not 立. influence on the application of the EAP curriculum design in Taiwan.. many teachers or students in graduate business programs were willing to participate,. ‧ 國. 學. possibly due to the heavy load in teaching, researching, or studies. Results of the. ‧. interviews also demonstrated that the nature of the universities (national vs. private;. sit. y. Nat. traditional university vs. university of technology) and students’ English proficiency. io. er. had great influence on whether courses or materials could adopt English. Furthermore, not many business programs with English-medium courses were available. Moreover,. al. n. v i n it was difficult for the researcherCto gain support fromU h e n g c h i the teachers for classroom observation in order to probe into in-depth issues. Hence, the researcher finally. targeted an MBA and an IMBA program at a national university of science and technology in which the teachers and students were willing to offer great help for this research.. Purpose of the Study and Research Questions In terms of academic English, graduate students have greater demands than undergraduates in general. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the EAP curriculum applied in the MBA and IMBA programs at the target university, from the teachers’ 3.

(24) and students’ perspectives. The following questions are explored: 1. What are the teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the status quo towards academic curriculum design? 2. What are the teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the instructional practices, material selection, and evaluation measures in EAP courses? 3. What are the teachers’ and students’ perceptions towards graduate students’ EAP needs? 4. How do students evaluate their current academic English abilities?. 政 治 大 立Delimitation of the Study. This study mainly aimed to investigate the status quo of the EAP curriculum. ‧ 國. 學. application perceived by teachers and students in the field of business administration. ‧. in Taiwan. Due to the above-mentioned wide divergence of goals, regulations, and. sit. y. Nat. students’ English proficiency in graduate business administration programs at. io. er. different universities, the scale of this research was only limited to an MBA and an IMBA program in a national university of science and technology. In addition, since. al. n. v i n C hthe results serve toUprovide an in-depth this study is of a descriptive nature, engchi. understanding for three groups of stakeholders—program organizers, teachers, and students. A framework for the EAP curriculum design does not fall into the scope of this research.. Significance of the Study This study is significant for the following two reasons. First, there has been little research into how EAP is applied in the business field in Taiwan, as English in Taiwan serves as a foreign language. Hence, this study can be considered as one of the pioneering cross-disciplinary works in this area. The research findings can provide the 4.

(25) status quo of the EAP curriculum and its related issues in business programs as a useful foundation for future research. Second, the insight into the similarities and differences from the teachers’ and students’ perceptions can provide practical guideline to program organizers, teachers, and students as reference for improving EAP curriculum in the business field.. Definition of Terms This section defines the terms which appeared in this research. Some of them are. 政 治 大. specific to this study while others are commonly used in related literature.. 立. English for Academic Purposes (EAP): In this study, EAP refers to the teaching and. ‧ 國. 學. learning of English for the business field. More specifically, it refers to EAP. ‧. curriculum design, English needs, and English application in the graduate. sit. y. Nat. programs of business administration. Hence, English-medium courses are the. io. er. main focus. In this field, the teaching content emphasized more on professional knowledge. However, for non-native speakers of English, EAP inevitably. al. n. v i n C hsuch as listening, speaking, involves basic English skills reading, and writing. engchi U. Academic English: In this study, academic English refers to the English which. students encounter in their studies at graduate business programs, e.g., specific business terms or concepts. MBA: Graduate Institute of Business Administration. In this study, MBA students are Taiwanese students enrolled in pursuing the degree of Master of Business Administration, excluding those who enrolled in the In-Service MBA program or Executive MBA program (EMBA). IMBA: Graduate Institute of International Business Administration. In this study, IMBA students are Taiwanese students enrolled in the target Graduate Institute 5.

(26) of International Business Administration program, excluding foreign students. Medium of instruction (MOI): MOI refers to the language that a teacher adopts for teaching the classes. In this study, the major MOI adopted by the teachers in the target MBA and IMBA programs are Mandarin Chinese (shortened to Chinese in this study) and English. In addition to Mandarin Chinese and English, the language of Taiwanese mentioned in this study refers to a variant of the Southern Min dialects, and it is the most widely spoken vernacular in Taiwan. EMC: An English-medium course. In this study, an EMC course refers to a course. 政 治 大. that has English listed as the teaching language on the course index information website.. 立. Chinglish: It is “the Sinicized English usually found in pronunciation, lexicology and. ‧ 國. 學. syntax, due to the linguistic transfer or ‘the arbitrary translation’ by the Chinese. sit. y. Nat. English” (Li, 1993, abstract section).. ‧. English learners, thus being regarded as an nunaccepted [unacceptable] form of. io. er. Singlish: It is “a variety of English [has] developed in Singapore which can be seen as a continuum ranging from a basilect, which is barely comprehensive to. al. n. v i n C hand Australian English, speakers of British, American to an acrolect which engchi U. differs from the higher sociolects of the above-mentioned varieties mainly by its distinctive pronunciation, particularly its patterns of intonation” (Platt, 1975, p. 363) Perception: In this study, “perception” refers to a particular way of understanding or thinking by targeted teachers and students regarding the research questions.. Overview of the Dissertation This dissertation comprises six chapters. Chapter 1 introduces the background and issues concerning the research questions. The definitions of terms specific to this 6.

(27) study are also provided. Chapter 2 reviews relevant literature and issues on EAP. Chapter 3 illustrates the methodology and research procedures adopted by this research. Chapters 4 and 5 report the quantitative and qualitative research findings respectively. Chapter 6 presents discussion, conclusions, and recommendations for future research.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 7. i n U. v.

(28) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW The literature reviewed will be discussed in five sections. The first section provides the theoretical underpinnings of English for General Purposes (EGP) and English for Specific Purposes (ESP). The second section introduces related literature and research on EAP. The third section presents aspects regarding curriculum design.. 政 治 大. The fourth section concerns needs analysis. The fifth section reviews the medium of. 立. instruction (MOI) and content-based instruction (CBI).. ‧ 國. 學. English for General Purposes and English for Specific Purposes. ‧. Numerous researchers (Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998; Far, 2008; Johns &. y. Nat. io. sit. Dudley-Evans, 1991; Swales, 1988) have pointed out that English Language Teaching. n. al. er. (ELT) or Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) can be divided. i n U. v. into two broad categories: English for General Purposes (EGP) and English for. Ch. engchi. Specific Purposes (ESP). The difference between EGP and ESP has been discussed in terms of theory and practice. According to Hutchinson and Waters (1987), there was no difference in theory between EGP and ESP; however, there was a large difference in practice. As Al-Humaidi (n.d.) aptly defined EGP: English for General Purposes (EGP) is essentially the English language education in junior and senior high schools. Learners are introduced to the sounds and symbols of English, as well as to the lexical/grammatical/rhetorical elements that compose spoken and written discourse. There is no particular situation targeted in this kind of language learning. Rather, it focuses on 8.

(29) applications in general situations: appropriate dialogue with restaurant staff, bank tellers, postal clerks, telephone operators, English teachers, and party guests as well as lessons on how to read and write the English typically found in textbooks, newspapers, magazines, etc. EGP curriculums also include cultural aspects of the second language. (¶ 5). On the other hand, the essentials of ESP root in learners’ needs (Robinson, 1984). More specifically, it is the awareness of learning purposes that makes ESP different from EGP (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987). ESP also seeks the balance between theory and practice. For example, according to Al-Humaidi (n.d.), “The design of syllabuses. 政 治 大 themselves in a particular occupation or specializing in a specific academic field. ESP 立 for ESP is directed towards serving the needs of learners seeking for or developing. courses make use of vocabulary tasks related to the field such as negotiation skills and. ‧ 國. 學. effective techniques for oral presentations” (¶ 4). In view of the scope involved in ESP,. ‧. Hutchison and Waters (1987) regards ESP as “an approach,” rather than “a product.”. sit. y. Nat. Strevens (1988) proposed a definition of ESP by offering four absolute. io. n. al. er. characteristics and two variables:. i n U. v. (1) Absolute characteristics: ESP consists of English language teaching which is: designed to meet specified needs of the learner related in content (i. e., in its themes and topics) to particular disciplines, occupations and activities centered on the language appropriate to those activities in syntax, lexis, discourse, semantics, etc., and analysis of this discourse in contrast with “General English”. Ch. engchi. Variable characteristics: ESP may be, but is not necessarily: restricted as to the language skills to be learned (e.g., reading only) not taught according to any pre-ordained methodology (as cited in Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 13). 9.

(30) Dudley-Evans and St John (1998) later modified the definition of the variable characteristics of ESP: . . ESP may be related to or designed for specific disciplines ESP may use, in specific teaching situations, a different methodology from that of general English ESP is likely to be designed for adult learners, either at a tertiary level institution or in a professional work situation. It could, however, be used for learners at secondary school level ESP is generally designed for intermediate and advanced students. Most ESP courses assume basic knowledge of the language system, but it can be used with beginners (p. 5). 政 治 大 In early days, it was a立 controversial issue whether ESP would be more successful. ‧ 國. 學. than EGP at preparing students to study through the medium of English—a validity issue (Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1991). Higgins (1966) and Allen and Widdowson. ‧. (1974) argued for the case and proposed reforms. However, ESP has been recognized. sit. y. Nat. internationally nowadays and is less of a controversial issue, especially in EFL. n. al. i n U. Nevertheless, as Johns and Dudley-Evans (1991) stated:. Ch. engchi. er. io. (English as a Foreign Language) contexts (Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1991).. v. Controversies and questions within ESP remain. Principal among them are the following: 1. How specific should ESP courses and texts be? 2. Should they [ESP] focus upon one particular skill, e.g., reading, or should the four skills always be integrated? 3. Can an appropriate ESP methodology be developed? (p. 304) Therefore, a debate between a “wide-angle” and a “narrow-angle” approach began. The “wide-angle” approach suggested using specific topics to teach language and skills, instead of teaching English from students’ own disciplines or professions (Hutchison & Waters, 1980, 1987; Spack, 1988; Widdowson, 1983; Williams, 1978). 10.

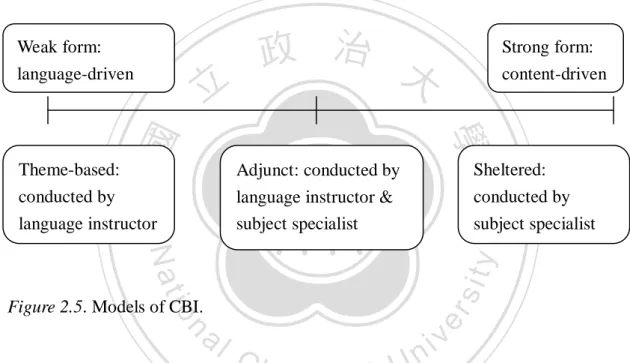

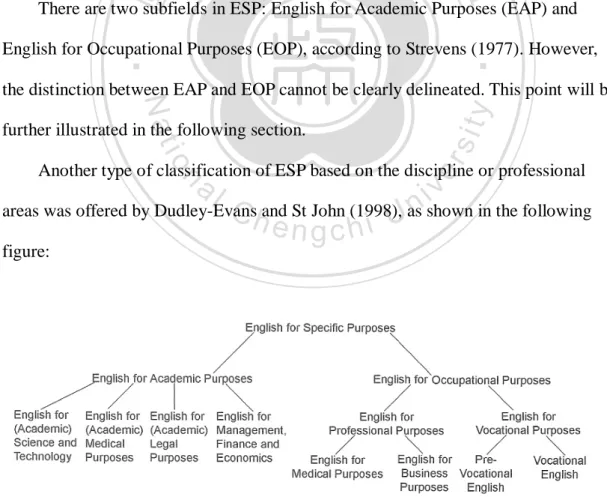

(31) However, the wide-angle approach was not suitable for all ESP courses, especially for graduate students and professionals (Swales, 1990) or in some EFL contexts (Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1991). Team-teaching in ESP demonstrated that students’ specific needs and actual language difficulties displayed in classes needed to be addressed (De Escorcia, 1984; Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1980). In regard to the difference between EGP and ESP, teachers and material designers nowadays take learners’ needs into consideration. As a result, teachers of General English were in fact using ESP syllabuses or materials for teaching. Hence,. 政 治 大 English teaching in general. Clearly the line between where General English courses 立 this phenomenon “demonstrates the influence that the ESP approach has had on. stop and ESP courses start has become very vague indeed” (Anthony, n.d., sec. 3).. ‧ 國. 學. There are two subfields in ESP: English for Academic Purposes (EAP) and. ‧. English for Occupational Purposes (EOP), according to Strevens (1977). However,. io. er. further illustrated in the following section.. sit. y. Nat. the distinction between EAP and EOP cannot be clearly delineated. This point will be. Another type of classification of ESP based on the discipline or professional. al. n. v i n C hand St John (1998),Uas shown in the following areas was offered by Dudley-Evans engchi figure:. Figure 2.1. ESP Classification by Professional Area. (Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998, p. 6) 11.

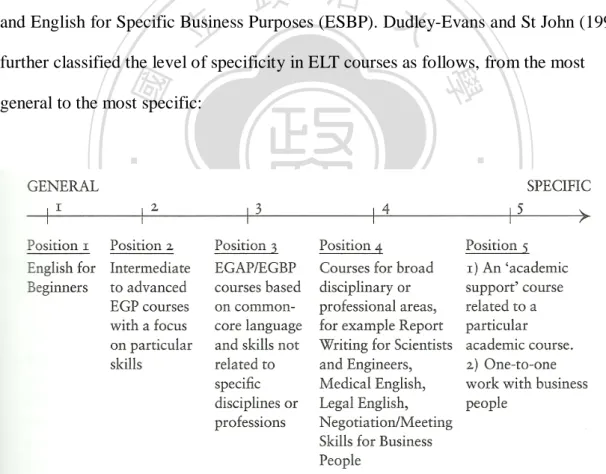

(32) Although English for Business Purposes (EBP) was categorized under EOP, EBP could be a unique category by itself: This classification places English for Business Purposes (EBP) as a category within EOP. EBP is sometimes seen as separate from EOP as it involves a lot of General English as well as Specific Purposes English, and also because it is such a large and important category. A business purpose is, however, an occupational purpose, so it is logical to see it as part of EOP. (Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998, p. 7). 政 治 大 and English for Specific Business Purposes (ESBP). Dudley-Evans and St John (1998) 立 EBP could also be divided into English for General Business Purposes (EGBP). further classified the level of specificity in ELT courses as follows, from the most. ‧ 國. 學. general to the most specific:. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Figure 2.2. Continuum of ELT Course Types. (Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998, p. 9). As demonstrated in Figure 2.2, two types of courses were categorized as the most specific ones. One type was academic courses, and the other was one-to-one. 12.

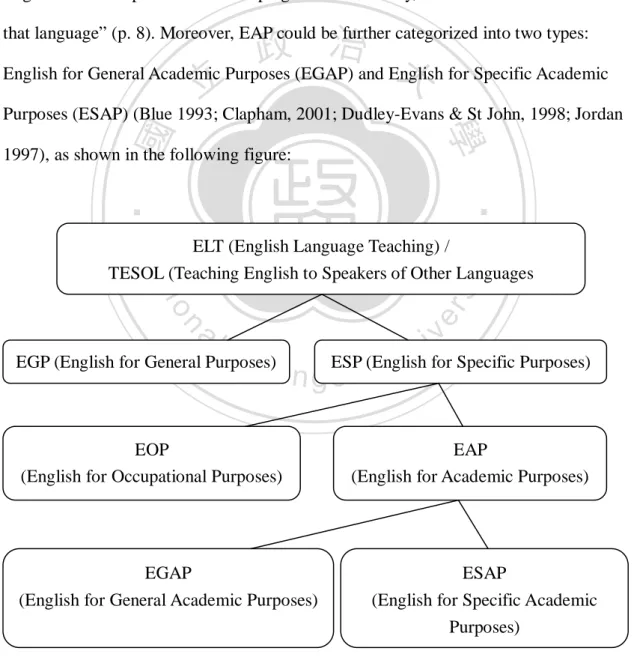

(33) work with business people.. English for Academic Purposes As pointed out by Jordan (1997), “EAP is needed not only for educational studies in countries where English is the mother tongue, but also in an increasing number of other countries for use in the higher education sector” (p. xvii). Flowerdew and Peacock (2001) defined English for Academic Purposes (EAP) as “the teaching of English with the specific aim of helping learners to study, conduct research or teach in. 政 治 大 English for General Academic Purposes (EGAP) and English for Specific Academic 立 that language” (p. 8). Moreover, EAP could be further categorized into two types:. Purposes (ESAP) (Blue 1993; Clapham, 2001; Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998; Jordan. ‧ 國. 學. 1997), as shown in the following figure:. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat. ELT (English Language Teaching) / TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. al. n. v i n Ch EGP (English for General Purposes) (English for Specific Purposes) e n g ESP chi U EOP (English for Occupational Purposes). EAP (English for Academic Purposes). EGAP (English for General Academic Purposes). ESAP (English for Specific Academic Purposes). Figure 2.3. Categories of English for Language Teaching Purposes. 13.

(34) Jordan (1997) proposed seven main study skills to be focused for EGAP: . academic reading. . vocabulary development. . academic writing. . lectures and note-taking. . speaking for academic purposes. . reference/research skills. . examination skills. 政 治 大. Three areas were included in ESAP, according to Jordan (1997):. 立. academic discourse and style. . subject-specific language. . materials design and production. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. . Although there are two main branches in ESP, EAP is often the main focus in. y. Nat. er. io. al. sit. education, as Johns and Dudley-Evans (1991) stated:. n. For most of its history, ESP has been dominated by English for academic purposes, . . . EAP continues to dominate internationally. However, the increased number of immigrants in English-speaking countries and the demand for MBA courses in all parts of the world have increased the demand for professional and business English, vocational English (VESL/EVP in the U. S., EOP in the U.K.), and English in the workplace (WPLT) programs. (p. 306). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. EAP, being one branch of ESP, also overlaps with EOP to a great extent, as depicted in the following figure:. 14.

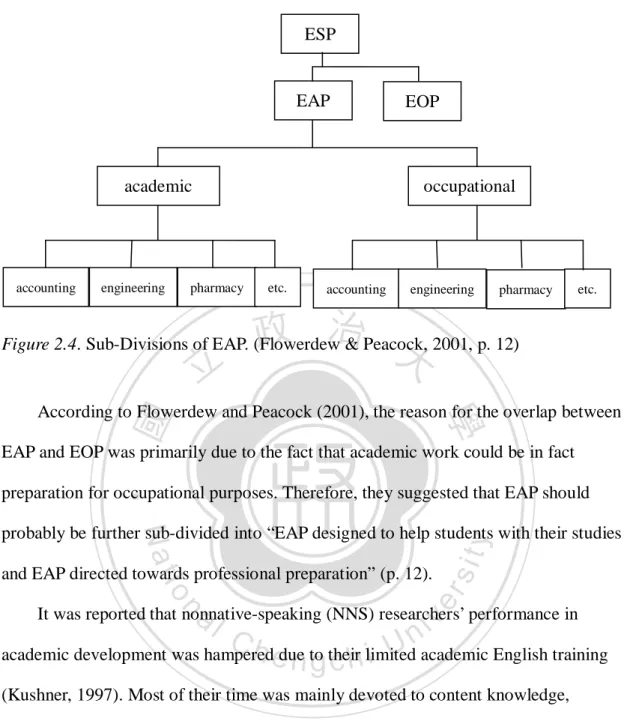

(35) ESP. EAP. academic. accounting. engineering. EOP. occupational. pharmacy. etc.. accounting. engineering. pharmacy. etc.. 政 治 大. Figure 2.4. Sub-Divisions of EAP. (Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 12). 立. ‧ 國. 學. According to Flowerdew and Peacock (2001), the reason for the overlap between EAP and EOP was primarily due to the fact that academic work could be in fact. ‧. preparation for occupational purposes. Therefore, they suggested that EAP should. n. al. er. io. and EAP directed towards professional preparation” (p. 12).. sit. y. Nat. probably be further sub-divided into “EAP designed to help students with their studies. i n U. v. It was reported that nonnative-speaking (NNS) researchers’ performance in. Ch. engchi. academic development was hampered due to their limited academic English training (Kushner, 1997). Most of their time was mainly devoted to content knowledge, instead of language learning (Jenkins, Jordan, & Weiland, 1993; Orr & Yoshida, 2001). Furthermore, studies indicated that most NNS researchers were not satisfied with their own English abilities although they acknowledged the importance of English (Kuo, 2001; Orr & Yoshida, 2001; Tsui, 1991). Hence, research progress was often slackened with NNS researchers due to their English deficiency (Yang, 2006). Swales (1990) further emphasized that it was wrong to treat EAP programs as remediation, and pointed out that helping postgraduate students to achieve English competence. 15.

(36) exceeding average native speakers was important as English is the main lingua franca in worldwide research. In regard to the application of EAP in higher education in Taiwan, Joe and Lin (2010, 2011) investigated teachers’ and graduate students’ perceptions towards EAP curriculums in business colleges in Taiwan. Ten professors who had taught EMCs (English-medium courses) in graduate programs or instructed graduate students to write English theses, and 12 graduate students from business colleges in Taiwan were interviewed. Results showed that teachers (subject specialists) had not heard of the. 政 治 大 EMCs they had taught. The perceptions of EAP for business graduate programs from 立 term EAP; therefore, their interpretations greatly differed—mainly relating to the. teachers’ perspectives included six areas or types of courses:. . professional courses. . English reading and writing abilities. . research methods. . case study. . business English. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. basic professional terminology. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. . Ch. engchi. i n U. v. On the other hand, business graduate students’ perceptions towards EAP consisted of five English abilities: . comprehension of professional terminology. . English conversation. . EAP materials reading. . oral presentation. . EAP writing From the findings of Joe and Lin (2010, 2011), professional terminology was no 16.

(37) doubt directly related to EAP. Reading and writing for EAP were also considered as important by both teachers and students. However, for teachers in the business field, the word “academic” was mostly associated with professional courses such as research methods and case study. For students, English conversation was considered as EAP, which was connected to what teachers meant by “business English.” In addition, business graduate students considered oral presentation skills important in EAP, while teachers did not particularly mention them.. 政 治 大 The term curriculum has had a wide variety of definitions (Finney, 2002; 立 Curriculum Design. Richards, 2001; Rodgers, 1989). The narrowest definition could be the synonym of. ‧ 國. 學. syllabus. However, under the broader definition of curriculum, Kelly (1989) argued. ‧. that the following must be included:. Nat. io. sit. y. the intentions of the planners, the procedures adopted for the implementation of those intentions, the actual experiences of the pupils resulting from the teachers’. n. al. er. direct attempts to carry out their or the planner’s intentions, and the ‘hidden learning’ that occurs as a by-product of the organization of the curriculum, and, indeed, of the school. (as cited in Richards & Renandya, 2002, p. 70). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. The teaching and learning of EAP faces its unique challenges and issues. Hence, the curriculum or course designers have to face these challenges and take them as opportunities for changes. In the following sections, literature review regarding syllabus design, instructional practices, teaching materials, and program evaluation will be presented.. Syllabus Design A syllabus consists of the detailed description of course objectives, procedures, 17.

(38) and contents (Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001; Richards & Schmidt, 2002). Many approaches were proposed for EAP syllabus design, and these approaches were greatly influenced by research in applied linguistics. Eight approaches to EAP syllabus design were summarized by Flowerdew and Peacock (2001). The first was Lexicogrammar-based approach, which concerned the teaching of vocabulary and sentence structure. Although it was influenced by register analysis in the 1960s and 1970s, it is still influential to date. The second was Function-notional-based approach in the 1970s, in opposition to the previous. 政 治 大 which emphasized cohesion and coherence of the texts. The fourth was 立. form-focused approaches. Next was the Discourse-based approach in the late 1970s,. Learning-centered approach, proposed by Hutchison and Waters (1987). It. ‧ 國. 學. emphasized what learners had to do in class in order to learn language items and skills,. ‧. meaningful and appropriate content, as well as communication in the classroom. The. sit. y. Nat. fifth was the Genre-based approach, which adopted authentic materials to build up. io. er. students’ awareness of the conventions and genre. The next approach was the skills-based approach, which concentrated on particular skills. According to. al. n. v i n Flowerdew and Peacock (2001),C this approach has been h e n g c h i Uvery important because it. started some EAP courses to meet students’ needs. Another important approach was content-based approach, which claimed that content would increase learners’ motivation. The final approach was task-based approach, in which the teacher was a “guide and advisor rather than omniscient source of knowledge” (Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 184). In this approach, students were given tasks, and teachers could assist students through modeling, providing feedback, and organizing learners’ cognitive structure.. 18.

(39) Instructional Practices In regard to teachers’ actual instructional practices in the classroom, collaboration or team-teaching models, as well as cultural issues relating to EAP are introduced.. Collaboration/Team-Teaching Models According to Flowerdew and Peacock (2001), the collaboration between specialists in different disciplines has become popular in EAP field. For example,. 政 治 大 encountered problems concerning language teachers not being able to fulfill students’ 立 Johns and Dudley-Evans (1980) reported that overseas students in the U.K.. needs for completing academic work. In order to help teachers and students overcome. ‧ 國. 學. the problems, Johns and Dudley-Evans (1980) conducted a team-teaching experiment. ‧. to a small class of graduate students. They stated that a language teacher needed to be. sit. y. Nat. able to help both subject teachers and students:. n. al. er. io. [a language teacher] needs to be able to grasp the conceptual structure of the subject his students are studying if he is to understand fully how language is used to represent that structure; to know how the range of different subjects are taught during the course; and to observe where and how difficulties arise in order that he can attempt to help both student and subject teacher to overcome them. (p. 8). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Later on, Flowerdew (1993) reported that a similar team-teaching experiment in a larger scale was conducted to beginning university students in Oman. A science course was team-taught by paired science and language teachers. Lectures and the assigned reading were focused. The language teachers would observe and video record the science classes. The recordings would then be used in the English classes. Moreover, English and science teachers would collaborate to write and edit the. 19.

(40) teaching materials for both science and English classes. Barron (1992) also proposed two collaborative teaching methods for subject specialists and language teachers: The first of these is the subjects-specialist informant method, where the subject specialist provides insights into the content and organization of texts and the processes of the subject. The second is the consultative method, where the subject specialist is brought in to participate at specific stages in a course. He/she may suggest topics for projects, give lectures, assist in the assessment of students’ work, and run discussions, among a whole range of activities. (as cited in Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 19). 政 治 大 Johns (1997) further suggested that EAP literacy specialists be “mediators” 立. among administrators, faculty, and students. She believed that EAP literacy teachers. ‧ 國. 學. should encourage subject specialists and students to work together and examine how. ‧. factors such as texts, roles, and contexts could better function to serve the EAP needs.. sit. y. Nat. The literacy teacher should educate both subject teachers and students to understand. io. er. the nature of academic literacy in their fields and the overall issues involved in a language program designed to help students in their disciplines.. n. al. Cultural Issues in EAP. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. There could be a mismatch between EAP teachers and learners from different cultures. According to Flowerdew and Peacock (2001), “Such mismatches may occur both where curricula with an ‘Anglo’ bias are employed in non-Anglo settings and where overseas NNSs study in Anglo countries” (p. 20). In other words, problems may occur in the application of EAP among English as the first, second, or foreign language contexts. For example, in a large-scale EAP project funded internationally in Egypt, Holliday (1994) discovered that foreign pedagogic models were imposed in non-Anglo EAP settings. Hence, scholars (Barron, 1992; Holliday, 1994) strongly 20.

(41) proposed that greater sensitivity to the social context should be taken into account for local EAP curricula. In a 3-year ethnographic study on academic classes conducted at an English-medium university in Hong Kong, Flowerdew and Miller (1995) found that four cross-cultural communication breakdowns may occur: ethnic culture, local culture, academic culture, and disciplinary culture. Ethnic culture concerned the contrasting ethnic backgrounds of the overseas teachers and students. Local culture regarded the overseas teachers not being familiar with the local settings. Academic. 政 治 大 and so on across cultures. Disciplinary culture referred to the unfamiliarity students 立 culture was concerned with the values, assumptions, attitudes, patterns of behavior. encountered in class in terms of the theories, concepts, terms, and so forth in the target. ‧ 國. 學. discipline. Flowerdew and Miller (1995) elaborated on the academic culture, as. io. sit. y. Nat. Table 2.1. ‧. shown in the following table:. er. Confucian and Western Values Relating to Academic Lectures. al. n. v Western i n C h lecturer valued respect for authority of lecturer e n g c h i U as a guide and facilitator lecturer should not be questioned lecturer is open to challenge Confucian. . student motivated by family and pressure to excel. student motivated by desire for individual development. positive value placed on effacement positive value placed on self-expression and silence of ideas emphasis on group orientation to learning. emphasis on individual development and creativity in learning. Note. From “On the notion of culture in second language lectures,” by J. Flowerdew and L. Miller, 1995, TESOL Quarterly, 29(2), p. 348. The term Confucian for East Asians had a rich meaning which consisted of Chinese historical, cultural, and traditional philosophical patterns.. Numerous studies (Benson, 1989; Cortazzi & Jin, 1994; Dudley-Evans & Swales, 21.

(42) 1980) pointed out the problems encountered by NNS students of English within the English-speaking countries in the EAP contexts. For instance, Cortazzi and Jin (1994) found that there were contrasting expectations between Chinese research students and their British supervisors. A number of articles (Cortazzi, 1990; Pennycook, 1996; Scollon, 1996) also noted a common cultural problem towards the attitudes of plagiarism whether in L1 (first language), ESL (English as a Second Language), or EFL contexts. It was reported that different academic cultures may have different interpretations towards the concept of plagiarism.. 立. 政 治 大 Teaching Materials. ‧ 國. 學. It has been an uphill struggle for students to read English texts in an EFL context,. ‧. let alone reading English texts in their academic subjects. Hence, factors influencing. sit. y. Nat. students’ comprehension of academic texts have been investigated. Clapham (1996). io. er. conducted a large-scale empirical study to examine the effect of background knowledge on reading test performance to three groups of students: business studies. al. n. v i n C hsciences, and physical and social science, life and medical science and technology. engchi U The investigation included reading passages taken from six sources on the. International English Language Testing System (IELTS): academic journals, popularizations (written for common educated people), study documents, adaptation of university papers, government reports, and textbooks. Clapham (1996) pointed out that several factors would influence the degree of comprehension for reading the academic texts, despite the fact that there were various text types and different backgrounds of the readers. Factors such as students’ familiarity of the concepts or terms, the amount of the terminology used, and the lexical cohesion had great impact on reading comprehension. Also, whether the terminology was explained in the texts 22.

(43) and whether the texts demanded an understanding in one particular discipline all played a crucial role in the readers’ comprehension of academic texts. Based on a large-scale empirical study, Clapham (2001) reported that there might be an English threshold level for students to activate background knowledge in terms of text comprehension, particularly when the texts are highly subject-specific. She found that “background knowledge becomes less important at higher ability levels, as learners become able to make use of all the linguistic cues in any given text” (as cited in Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 5). Clapham (2001) concluded that the topics and. 政 治 大 She also suggested that the rhetorical function might have an effect on the specificity 立. genres of the texts should be checked with specialists in the field, especially genres.. of a text. For instance, in her study, the texts describing scientific processes were. ‧ 國. 學. more specific than introductions to academic articles. Although there seemed to be no. ‧. agreement about what an academic text consisted of, texts came from academic. sit. y. Nat. sources were still suggested as teaching materials for EAP courses. She further. io. er. suggested that students read and listen to EGAP academic texts approved by teachers. These texts should include “different rhetorical functions such as introductions,. al. n. v i n reports of research methods andC discussions of resultsU h e n g c h i which are common across most disciplines” (p. 99). As for ESAP texts, teachers need to ensure that students had the appropriate background knowledge before adopting such texts. There were several forms in the academic articles (Bazerman, 1988; Swales, 1990), which made it difficult to generalize the specificity of the texts. Many kinds of discourse were also likely to appear in one single publication (Clapham, 2001; Dudley-Evans & Henderson, 1990). For example, the introduction section might be easier to read, while the following sections might contain a highly specialized description. These factors also contributed to the difficulty level of the comprehensibility for readers. 23.

(44) Each discipline has its own specialized style of language use, and the style should be incorporated into the teaching materials. There has been an increasing number of EAP materials designed for different disciplines by the publishers to satisfy teachers’ as well as learners’ needs. Northcott (2001) reported that “pre-sessional EAP programmes for prospective MBA students in the UK are increasing in frequency” and that “publishers are evincing interest in producing MBA-specific teaching materials for L2 [second language] English speakers preparing to attend MBA programmes” (p. 16). Hence, Kuo (1993) suggested that teachers use the published. 政 治 大. textbooks as a data bank and adopt the most appropriate materials for EAP courses.. 立. Program Evaluation. ‧ 國. 學. There has been an increasing interest for educators and curriculum planners to. ‧. carry out curriculum evaluation since the 1960s (Richards, 2001). Different aspects. sit. y. Nat. can be adopted to evaluate a language program (Richards, 2001; Sanders, 1992; Weir. io. er. & Roberts, 1994). These aspects included curriculum design, syllabus and program content, classroom processes, materials of instruction, teachers, teacher training,. al. n. v i n C h learner motivation, students, monitoring of pupil progress, institution, learning engchi U. environment, staff development, and decision making. According to Richards (2001), the concerns of these aspects were as follows: . curriculum design: quality of program planning and organization. . syllabus and program content: relevance; difficulty levels; efficiency of the assessment procedures. . classroom processes: extent to which a program is implemented appropriately. . materials of instruction: specific materials that help students learn. . teachers: teaching methods; perceptions of the program; teaching content. . teacher training: training that teachers have received 24.

(45) . students: students’ gain; perceptions of the program; students’ participation. . monitoring of pupil progress: in-progress evaluations of student learning. . learner motivation: teachers’ effectiveness in helping learners to achieve goals. . institution: administrative support; resources. . learning environment: fulfillment of environment for students’ educational needs. . staff development: extent to which the school provides opportunities for staff to increase their efficiency. . decision making: administrators’ or teachers’ decisions which result in learner. 政 治 大 In addition, the evaluation for EAP particularly concerned the need to collect 立 benefits. implementation (Hewings & Dudley-Evans, 1996).. sit. y. ‧. Nat. Needs Analysis. 學. ‧ 國. information and evaluate all aspects of the curriculum, from planning to. io. er. The need of English for nonnative speakers, as pointed out by Flowerdew and Peacock (2001), included conducting business, gaining access to technology and. al. n. v i n C hacademic publication. expertise, and having international As ESP was addressed as an engchi U approach (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987), course designs should revolve around. learners’ needs. Strevens (1988) concluded that the rationale for ESP was based on four claims: . being focused on the learner’s needs, it wastes no time is relevant to the learner is successful in imparting learning is more cost-effective than “General English” (as cited in Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 13). Needs analysis has drawn scholars’ attention since the 1970s (Braine, 2001; 25.

(46) Hutchinson & Waters, 1987), and results of needs analysis studies have a great impact on ESP programs, including course design, material selection, teaching and learning, and evaluation (Orr, 2001; Strevens, 1988). Hutchinson and Waters (1987) claimed that for ESP course design, the first step should be to identify the target situation, and then to analyze the language features in that context. Kuo (2001) further added that difficulties students would face should also be identified. In other words, needs analysis and problem analysis should both be considered in ESP course design (Johns & Dudley-Evans, 1991). Although needs. 政 治 大 remains controversial (Cameron, 1998; Richterich, 1983; Stufflebeam, McCormick, 立 analysis is considered crucial in ESP course design, the definition of needs analysis. Brinkerhoff, & Nelson, 1985; West, 1994).. ‧ 國. 學. Flowerdew and Peacock (2001) defined needs analysis and pointed out the. ‧. relationship between needs analysis and EAP:. Nat. y. sit. n. al. er. io. There is a general consensus that needs analysis, the collection and application of information on learners’ needs, is a defining feature of ESP and, within ESP, of EAP. Needs analysis is the necessary point of departure for designing a syllabus, tasks and materials. With its concern to fine tune the curriculum to the specific needs of the learner, needs analysis was a precursor to subsequent interest in ‘learner centeredness.’ (p. 178). Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Flowerdew and Peacock (2001) further addressed the importance of the continuity of needs analysis, and commented that students should take part in course planning. Moreover, teachers should also make sure that learners be aware of the outline of the goals for the course, and even for each lesson. Since learners of different proficiency levels may well be found in an EAP classroom, Flowerdew and Peacock (2001) suggested that “needs analysis needs to reflect this likely variation in target audience” (p. 179).. 26.

數據

+7

相關文件

(2)本所研究生必須修畢必修課程及修滿 36 學 分,通過碩士論文後發給畢業證書;修業期

臺中榮民總醫院埔里分院復健科 組長(83年~今) 中山醫學大學復健醫學系職能治療 學士.. 南開科技大學福祉科技與服務管理研究所

分署 崑山科技大學 私立 技專校院 財務金融 財富管理與行銷學程 136 雲嘉南. 分署 大同技術學院 私立 技專校院

C7 國立台中護理專科學校護理科 台中市 主任 C8 中臺科技大學老人照顧系 台中市 助理教授 C9 中山醫學大學公共衛生學系 台中市 助理教授 C10

國立臺北教育大學教育經營與管理學系設有文教法律碩士班及原住民文

國立高雄師範大學數學教育研究所碩士論文。全國博碩士論文資訊網 全國博碩士論文資訊網 全國博碩士論文資訊網,

Specifically, the senior secondary English Language curriculum comprises a broad range of learning targets, objectives and outcomes that help students consolidate what they

- allow students to demonstrate their learning and understanding of the target language items in mini speaking