©2010 Taipei Medical University

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

1. Introduction

The elderly population of Taiwan is rapidly increasing, currently accounting for 10.4% of the population,1 and

has been predicted to increase to 20% of the popula-tion by the year 2025.2 Dementia, a progressive and ir-reversible neurodegenerative disorder, is becoming an increasingly important health issue in countries with Background/Purpose: Individuals with mild-to-moderate dementia often exhibit

depres-sion and apathy as manifested by symptoms of negative affect. The purpose of this study was to determine whether or not reminiscence group therapy (RGT) reduces depression and improves symptoms of apathy.

Methods: The study was one of experimental design with a pre–post control group; 61

residents from two nursing homes were randomly distributed into two parallel groups. An RGT program consisting of 12 sessions, 40–50 minutes per week, was implemented for the residents in the experimental (intervention) group. The instruments used to collect data included the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, the Geriatric Depression Scale, the Apathy Evaluation Scale, and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 15.0.

Results: After 12 sessions, the residents in the intervention group reported a reduction in

depressed mood (Z = –2.99, p < 0.05), and showed specific improvements in their behavior score (Z = –3.10, p < 0.05) and cognition apathy score (Z = –1.95, p < 0.05). Neuropsychiatric Inventory depression scores had also decreased (Z = –2.20, p < 0.05).

Conclusion: RGT has significant efficacy in the treatment of depressed mood and apathy

in patients with mild-to-moderate stage dementia. This non-pharmacological intervention reduced emotional distress among nursing home residents with dementia.

Received: Oct 14, 2009 Revised: Jan 8, 2010 Accepted: Feb 4, 2010 KEY WORDS: apathy; dementia; depression; nursing home; reminiscence therapy

Reminiscence Group Therapy on Depression and

Apathy in Nursing Home Residents With

Mild-to-moderate Dementia

Chia-Jung Hsieh

1, Chueh Chang

2, Shu-Fang Su

3, Yu-Ling Hsiao

4,

Ya-Wen Shih

5,6, Wen-Hui Han

7, Chia-Chin Lin

8*

1School of Geriatric Nursing and Care Management, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan 2Institute of Health Policy and Management, School of Nursing, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 3College of Nursing, National Taipei College of Nursing, Taipei, Taiwan

4Department of Nursing, Kai-Suan Psychiatric Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 5Taipei City Hospital Songde Campus, Taipei, Taiwan

6Tzu Chi College of Technology, Hualien, Taiwan

7Department of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, Yuanpei University, Hsinchu, Taiwan 8School of Nursing, College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan

*Corresponding author. School of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, 250 Wu-Hsing Street, Taipei 110, Taiwan. E-mail: clin@tmu.edu.tw

aging populations.3 Worldwide, the number of individ-uals with dementia is expected to double every 20 years.4 More than 115,000 Taiwanese have dementia, with the numbers expected to increase to more than 220,000 patients by the year 2026.2 The prevalence of dementia among the elderly in Taiwan is 5.5%, but the prevalence among those in institutions providing long-term care and in nursing homes is over 60%.5

In the course of the disease, 80–90% of people with dementia will have neuropsychiatric symptoms.6 Neuropsychiatric behaviors such as apathy, depressed affect, irritability and appetite changes are frequently observed in people with dementia.7,8 Such symptoms may be a predictive factor used in deciding when to place an elderly person in a long-term care facility.9 In the United States, approximately 26–43% of elderly nursing home residents suffer from mild-to-severe depression,10,11 and have an apathy symptom point prevalence of 60.3%.12

Apathy is not depression.12,13 Rather, apathy is de-fined as a lack of motivation not attributable to a di-minished level of consciousness, cognitive impairment, and emotional distress related to daily life.14,15 Apathy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease has been consist-ently associated with relatively more severe cognitive deficits, more severe impairments in daily life activities, higher levels of burden and distress among caregivers, and increased resource use.16,17 Apathy is also associated with reduced levels of functioning, decreased response to treatment, poor illness outcomes, and chronicity.12 The need to provide high-quality mental health care for elders with dementia in nursing home settings is becom-ing a critical issue as the elderly population grows rapidly and institutional care becomes a necessity for some.

Recent research suggests that pharmacologic ap-proaches are not effective and may cause harm,4 while several studies have suggested that reminiscence therapy for elders is effective in addressing their psychological health.18,19 Reminiscing is the process of thinking or tell-ing others about one’s past experiences. These studies show that purposeful reminiscence group therapy (RGT) results in reduced depressive symptoms,20–22 maintain-ing or improvmaintain-ing self-esteem23,24 and life satisfaction.24,25 RGT improves social interaction,19,25,26 motivates peo-ple to explore life themes, and increases confidence about their past lives.20,27 However, results have been inconsistent.19,20,23 The reasons for this may include many factors such as the frequency of therapy administered, enjoyment of reminiscence and regrets, and psycho-logical health.18 Apart from the factors relating to the form of intervention, one possible explanation is that such studies did not control for demographic charac-teristics or illness status.21,22,25

In Taiwan, most studies of RGT have focused on eld-erly people living in long-term care facilities,26 nursing homes,23 or community settings,28 and have rarely in-volved residents of institutions with dementia.29 There

have been no prior studies conducted of RGT for resi-dents of institutions with mild-to-moderate stage demen-tia in Taiwan.

Therefore, we hypothesized that, relative to a con-trol group at 3 months, residents in nursing homes who receive RGT intervention would show significantly different outcomes. We designed our study with the goal of developing an effective nursing strategy using non-pharmacological care for patients with dementia. The purpose of this study was to test the effectiveness of RGT for reducing depressed mood and improving symptoms of apathy in nursing home residents with mild-to-moderate stage dementia.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and study design

We used an experimental, pre–post control group design. We recruited subjects from two free-standing nursing homes. The two private nursing homes with 99 beds in northern Taiwan were purposely selected; then we ran-domly assigned each resident to the experimental or control group. Sample size was predicted with a power analysis of 0.8. The inclusion criteria were: ability to speak fluently in Chinese or Taiwanese; and no severely damaged sensory function (e.g., no loss of vision or hearing). Subjects were excluded if they were suffering from delirium. Data were collected from September 2005 to March 2006. Participants were assessed using a structured protocol. Physicians made the diagnoses of dementia based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, and reviewed patients’ medical history, laboratory find-ings, and physical examination results. Treatment group participants received RGT, and all participants were re-assessed at 3 months from baseline. We controlled for the severity of dementia using the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale to determine the degree of severity. This study was approved by the institutional human subjects committee of Taipei Medical University. Permission to conduct this study was given by the administration of the nursing home facilities, and written informed con-sent was obtained from the patients and their caregivers. 2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Clinical Dementia Rating Scale

The severity of dementia was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR). The CDR is a five-point scale where a score of 1 indicates mild and a score of 2 indicates moderate dementia. In assigning CDR scores, the six domains that are used to construct the overall CDR tables are each scored individually. The six domains are memory, orientation, judgment and problem-solving,

community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal.30 Interrater reliability and criterion validity for the global CDR score and the individual domain scores have been demonstrated.31 The CDR has become widely accepted in the clinical setting as a reliable and valid global assess-ment measure for deassess-mentia of the Alzheimer type.30,31 2.2.2. Geriatric Depression Scale

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was developed as a basic screening measure for depression in older adults. There are 15 items.32 The scale has been tested and used extensively with older populations. It is a brief ques-tionnaire in which participants are asked to respond to 30 questions by answering yes or no in reference to how they felt on that day. The GDS represents a reliable and valid screening device for measuring depression in the elderly, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression.32

2.2.3. Apathy Evaluation Scale, clinician-administered We used the Apathy Evaluation Scale, clinician-administered (AES-C), to measure indicators of apathy in the previous 4 weeks.15 It is a questionnaire that is used to evaluate behavior, cognition and emotion sub-scales. The items are rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 4 (very characteristic). The AES-C has multiple forms, which have been shown to have good reliability and validity.33,34 Higher scores indicate higher levels of apathy, reflecting a lower level of motivation to get things done during the day. 2.2.4. Neuropsychiatric Inventory

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) was developed to assess psychopathology in patients with dementia and other neuropsychiatric disorders. The NPI has 12 subareas, and we used the two subareas of apathy and depression.35 Severity multiplied by frequency is cal-culated for each behavioral change during the previ-ous month or since the last evaluation. Cronbach’s α for overall reliability of the NPI was 0.88 and the con-current validity was good, as shown by an acceptable correlation between NPI scores and other validated measurements.35,36

All the scales were administered by a single investiga-tor to maintain uniformity across the two groups. Infor-mation on neuropsychiatric symptoms was obtained from the nursing home staff by using the NPI. The staff were asked to rate the frequency and severity of various disturbances on the NPI as noted in the preceding month. 2.3. RGT protocol

Research teams who specialized in geriatric psychi-atric nursing served as leaders and co-leaders in the

RGT. The topic of the RGT centered on life span issues, which was carefully designed for elders who were able to share their stories with other elderly people. The 12-session, 40–50 minutes/week RGT program was imple-mented for residents in the experimental group. The components of all the sessions had clear structures and guidelines for the leaders and co-leaders to facili-tate the group interventions. The leader frequently en-couraged participants to tell their stories and to gather old photos, albums, or meaningful materials to use when they shared their personal life experiences on, for example, friendships, work experience, and signifi-cant events. Residents were also encouraged to think of the group as an opportunity to have fun in life re-views. We designed the research protocol to include 18 activities suitable for all elderly patients residing in long-term care.19,37 The principles used to design the in-tervention were derived inductively from nursing text-books, care planning guides and nursing information systems.

We also created a safe and comfortable environment for the participants, which required a brightly lit, sizea-ble space with a quiet, warm and relaxed atmosphere. Being able to sit in a circle allowed participants to have eye contact, to hear and to communicate with the others in the group whenever they wanted. The group leader and co-leader were responsible for closely observing the participants for increased agitation and anxiety dur-ing the meetdur-ing. A week before and 3 months after the intervention, all participants were asked to complete questionnaires. The reason residents were observed for 3 months was because that was the average length of the intervention program.

Reminiscence therapy is a nurse-initiated intervention that has the advantage of being cost-effective, thera-peutic, social and recreational for the institutionalized older adult.19 Reminiscence therapy has been shown to be a valuable intervention for elderly patients,29 and the therapy may prove to be a beneficial alternative to more traditional treatment modalities for reducing the effects of depressive symptoms.19 It is an attractive, non-stigmatizing and easy-to-administer intervention.20 2.4. Data analysis

We used the χ2 and Mann-Whitney tests to compare the demographic characteristics of the experimental and control groups. We computed the means, standard deviations, and ranges for the outcome measures and treatment characteristics. Using the Wilcoxon signed-ranked test, we compared the effects of RGT in each group. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a nonparamet-ric statistical hypothesis test for the case of two related samples or repeated measurements on a single sample. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with a significance level of 0.05; all analyses were two-sided.

3. Results

There were 33 participants in each group at the begin-ning of the study, but four in the experimental group and one in the control group had withdrawn by the end of the study. One individual died in a manner unre-lated to the project. The observed power for this study was 0.9.

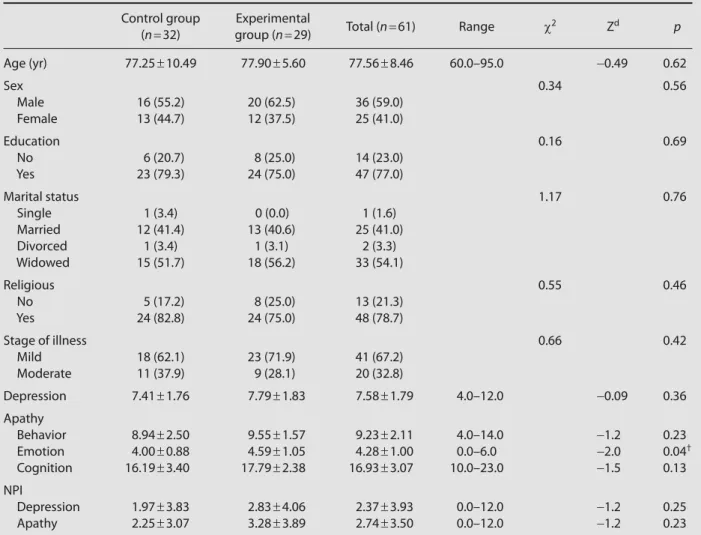

Dementia patients were primarily male (59.0%) and had mild dementia (67.2%), with a mean age of 77.56 ± 8.46 years (Table 1). At the start of the RGT intervention program, there were no significant differences as mea-sured by t test between the experimental and control groups with regard to demographic characteristics, ill-ness stage, depression and behavior, such as cognitive and apathy symptoms.

3.1. Effects of RGT

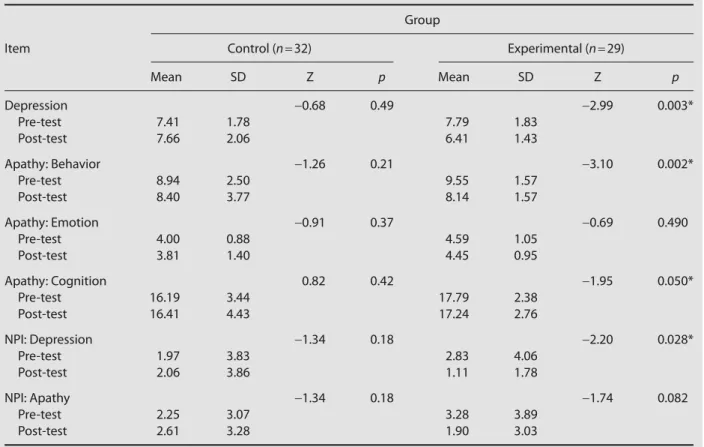

After the 12-week RGT protocol was completed for the experimental group, the level of depression and the three dimensions of apathy symptoms were reevaluated

for both groups of participants. As shown in Table 2, the depression score (Z = −2.99), and the behavior (Z = −3.10) and cognitive (Z = −1.95) apathy symptom groups all showed a marked improvement in the experimental group (p < 0.05). Only one variable, the emotional apa-thy symptom, showed no significant difference. NPI de-pression scores had also decreased (Z = −2.20, p < 0.05). In the control group, all variables showed no significant differences after statistical analysis.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that RGT is associated with reduced symptoms of negative affect in institutionalized residents, after controlling for important confounding demographic variables. The re-sults of this study support the hypothesis that RGT can improve depression and apathy symptoms in nursing home residents with mild-to-moderate stage demen-tia. The current findings are consistent with those of prior studies that showed reduced depression20–22 and

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the nursing home residents before reminiscence group therapy*

Control group Experimental

Total (n = 61) Range χ2 Zd p (n = 32) group (n = 29) Age (yr) 77.25 ± 10.49 77.90 ± 5.60 77.56 ± 8.46 60.0–95.0 −0.49 0.62 Sex 0.34 0.56 Male 16 (55.2) 20 (62.5) 36 (59.0) Female 13 (44.7) 12 (37.5) 25 (41.0) Education 0.16 0.69 No 6 (20.7) 8 (25.0) 14 (23.0) Yes 23 (79.3) 24 (75.0) 47 (77.0) Marital status 1.17 0.76 Single 1 (3.4) 0 (0.0) 1 (1.6) Married 12 (41.4) 13 (40.6) 25 (41.0) Divorced 1 (3.4) 1 (3.1) 2 (3.3) Widowed 15 (51.7) 18 (56.2) 33 (54.1) Religious 0.55 0.46 No 5 (17.2) 8 (25.0) 13 (21.3) Yes 24 (82.8) 24 (75.0) 48 (78.7) Stage of illness 0.66 0.42 Mild 18 (62.1) 23 (71.9) 41 (67.2) Moderate 11 (37.9) 9 (28.1) 20 (32.8) Depression 7.41 ± 1.76 7.79 ± 1.83 7.58 ± 1.79 4.0–12.0 −0.09 0.36 Apathy Behavior 8.94 ± 2.50 9.55 ± 1.57 9.23 ± 2.11 4.0–14.0 −1.2 0.23 Emotion 4.00 ± 0.88 4.59 ± 1.05 4.28 ± 1.00 0.0–6.0 −2.0 0.04† Cognition 16.19 ± 3.40 17.79 ± 2.38 16.93 ± 3.07 10.0–23.0 −1.5 0.13 NPI Depression 1.97 ± 3.83 2.83 ± 4.06 2.37 ± 3.93 0.0–12.0 −1.2 0.25 Apathy 2.25 ± 3.07 3.28 ± 3.89 2.74 ± 3.50 0.0–12.0 −1.2 0.23

changes in apathy symptoms. The changes were evi-dent in activities that stimulated motivation in demen-tia residents14,38 and improved social interaction.19,25,26 The possible explanation for the meaning of past expe-riences to the program is that when experience/feeling is shared, the process of integration in their lives is im-proved.21 The group situation is a powerful trigger for individuals to share their story. The group dynamic of catharsis may also have contributed to reducing nega-tive affect.

RGT is an important non-pharmacological interven-tion that is associated with improvement in affect, and may thus help to quickly reduce the emotions and be-havior that are associated with depression, and improve apathy symptoms. It has been pointed out that partici-pating in RGT allows patients more chances to interact with their environments and, by inducing autobiographic memory, RGT can play a role in reconstructing memory throughout life in addition to its stabilizing role.39 During each RGT session, residents were stimulated to recall past events over the course of their whole life experience and to talk with others, sharing their opinions. Reminiscing is about remembering, putting things together again, seeking, recovering and communicating meaning. When they expressed and released emotions, the participants experienced the supportive atmosphere of the group, which created a sense of being accepted and valued

as a group member, a finding congruent with those of previous studies.20–23 We put every session of life review into a life span perspective. The systematic program could help us identify the developmental precursors and antecedent conditions for elderly people’s expression. Life review is an adaptive response to aging for those who have encountered marked difficulties in life.20,39 No residents showed increased agitation or anxiety during the intervention. Instead, some reported experiencing pleasure. It is useful to apply RGT in the early treatment of depression,21–40 as one of the functions of reminisc-ing is to foster interpersonal relationships that could increase motivation to respond to life situations.41

Other non-pharmacologic interventions to reduce negative affect, such as exercise intervention, rarely in-volve recalling memories or verbal training.42 Providing optimal care for individuals with dementia is a signifi-cant challenge in long-term institutional care. In the West, recent studies on lives disrupted by the events of World War II illustrate how such historical events interfere with normal life processes and the potential outcome of such experiences for appreciating, thinking, and com-municating new insights and values.20,41,42 Emphasizing cultural heritage is helpful and can raise very impor-tant issues when we arrange interventions that deal with aging and personal meaning. Healthy psychologi-cal functioning is beneficial not only to the individual

Table 2 Effect of reminiscence group therapy on depression

Group

Item Control (n = 32) Experimental (n = 29)

Mean SD Z p Mean SD Z p Depression −0.68 0.49 −2.99 0.003* Pre-test 7.41 1.78 7.79 1.83 Post-test 7.66 2.06 6.41 1.43 Apathy: Behavior −1.26 0.21 −3.10 0.002* Pre-test 8.94 2.50 9.55 1.57 Post-test 8.40 3.77 8.14 1.57 Apathy: Emotion −0.91 0.37 −0.69 0.490 Pre-test 4.00 0.88 4.59 1.05 Post-test 3.81 1.40 4.45 0.95 Apathy: Cognition 0.82 0.42 −1.95 0.050* Pre-test 16.19 3.44 17.79 2.38 Post-test 16.41 4.43 17.24 2.76 NPI: Depression −1.34 0.18 −2.20 0.028* Pre-test 1.97 3.83 2.83 4.06 Post-test 2.06 3.86 1.11 1.78 NPI: Apathy −1.34 0.18 −1.74 0.082 Pre-test 2.25 3.07 3.28 3.89 Post-test 2.61 3.28 1.90 3.03

but also to society and to future generations.41 For an aging society, it is important to coherently integrate individuals’ daily lives with their prior experience and present environment.

4.1. Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. First, the study did not use a double-blinded randomized design, which prevented us from determining whether or not the effects noted would have occurred in the absence of RGT. Second, we did not evaluate the long-term effects of the RGT intervention, and so have only shown the short-term benefits of RGT.

5. Conclusion

The results of our study indicate that RGT significantly improved depression and apathy symptoms in nursing home residents with dementia. This study controlled for the cognitive function of each dementia patient, and then tested the effect of RGT. Reminiscence has become an increasingly popular approach to promot-ing the mental health of the elderly. Reminiscence in-tervention supports Erikson’s original insight into the dynamics of integrity in late life.42

We believe that our findings may be useful for design-ing elderly care programs because dementia is one of the most feared illnesses of aging and is frequently cited as a reason for renewed life meaning in positive aging. The RGT protocol used in this study can serve as a refer-ence for future studies developing non-pharmacological intervention for elderly in institutional care.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan [DOH 95-TD-M-113-062-(2)(2/2)]. We are grateful to all the nursing home residents, their caregivers and the nursing home admin-istrators who supported this project.

References

1. Department of Health, Executive Yuan. The Survey of Status of Elderly Population in Taiwan. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Health, Executive Yuan, 2008.

2. Department of Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan. Population Housing Census: Statistical Analysis Abstract. Taipei, Taiwan: Department of Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, 2008.

3. Lonie JA, Tierney KM, Herrmann LL, Donaghey C, O’Carroll RE, Lee A, Ebmeier KP. Dual task performance in early Alzheimer’s disease, amnestic mild cognitive impairment and depression. Psychol Med 2009;39:23–31.

4. Morris JC. Dementia updates 2005. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2005;19:100–17.

5. Chiu YC, Shyu Y, Liang J, Huang HL. Measure of quality of life for Taiwanese persons with early to moderate dementia and related factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23:580–5.

6. Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, Steffens DC, Norton MC, Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC. The persistence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:19–26.

7. Cummings JL, McPherson S. Neuropsychiatric assessment of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Aging Clin Exp Res 2001;13:240–6.

8. Hsieh CJ, Chang CC, Lin CC. Neuropsychiatric profiles of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in Taiwan. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:570–7.

9. Aalten P, de Vugt ME, Jaspers N, Jolles J, Verhey FR. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Part I: findings from the two-year longitudinal Maasbed study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:523–30.

10. Starkstein SE, Mizrahi R, Power BD. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology, clinical correlates and treatment. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008;20:382–8.

11. Luchsinger JA, Honig LS, Tang MX, Devanand DP. Depressive symptoms, vascular risk factors, and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23:922–8.

12. Yeager CA, Hyer L. Apathy in dementia: relations with depression, functional competence, and quality of life. Psychol Rep 2008;102: 718–22.

13. Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, Masterman D, Miller BL, Craig AH, Paulsen JS, et al. Apathy is not depression. J Neuropsychiatr 1998;10:314–9.

14. Marin RS. Differential diagnosis and classification of apathy. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:22–30.

15. Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res 1991;38:143–62. 16. Starkstein SE, Petracca G, Chemerinski E, Kremer J. Syndromic

validity of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:872–7.

17. Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, Geldmacher DS. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1700–7.

18. McKee KJ, Wilson F, Chung MC, Hinchliff S, Goudie F, Elford H, Mitchell C, et al. Reminiscence, regrets and activity in older peo-ple in residential care: associations with psychological health. Br J Clin Psychol 2005;44:543–61.

19. Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, Arean PA, Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interven-tions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in pa-tients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:2182–8.

20. Bohlmeijer E, Smit F, Cuijpers P. Effects of reminiscence and life re-view on late-life depression: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:1088–94.

21. Bohlmeijer E, Valenkamp M, Westerhof G, Smit F, Cuijpers P. Creative reminiscence as an early intervention for depression: results of a pilot project. Aging Ment Health 2005;9:302–4. 22. Jones ED, Beck-Little R. The use of reminiscence therapy for the

treatment of depression in rural-dwelling older adults. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2002;23:279–90.

23. Chao SY, Liu HY, Wu CY, Jin SF, Chu TL, Huang TS, Clark MJ, et al. The effects of group reminiscence therapy on depression, self esteem, and life satisfaction of elderly nursing home residents. J Nurs Res 2006;14:36–45.

24. Lin YC, Dai YT, Hwang SL. The effect of reminiscence on the eld-erly population: a systematic review. Public Health Nurs 2003;20: 297–306.

25. Cook EA. Effects of reminiscence on life satisfaction of elderly female nursing home residents. Health Care Women Int 1998;19: 109–18.

26. Hsiao CY, Yin TJC, Shu BC, Yeh SH, Li IC. The effects of reminis-cence therapy on depressed institutionalized elderly. J Nurs 2002; 49:43–53.

27. Wang JJ. The comparison of effectiveness among institutional-ized and non-institutionalinstitutional-ized elderly people in Taiwan of remi-niscence therapy as a psychological measure. J Nurs Res 2004;12: 237–45.

28. Pittiglio L. Use of reminiscence therapy in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Lippincotts Case Manag 2000;5:216–20.

29. Sheu PY, Wang YY, Lee YY, Liu SJ, Chiu LJ, Hsieh CJ. The efficacy of reminiscence therapy for elderly patients with mental illness. New Taipei J Nurs 2005;7:33–44. [In Chinese]

30. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–4.

31. Morris JC. Clinical Dementia Rating: a reliable and valid diag-nostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9:173–6.

32. Sheikh J, Yesavage J. Geriatric Depression Scale: recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 1986;5:165–73. 33. Lueken U. Development of a short version of the Apathy Evaluation

Scale specifically adapted for demented nursing home residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:376–85.

34. Clarke DE. Apathy in dementia: an examination of the psychomet-ric properties of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;19:57–64.

35. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–14.

36. Matsumoto N, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Hyodo T, Ishikawa T, Mori T, Toyota Y, et al. Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale (NPI-D) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Brief Questionnaire Form (NPI-Q). No To Shinkei 2006;58:785–90.

37. Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neu-ropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 162:1996–2021.

38. Saul S, Saul SR. Application of joy in group psychotherapy for the elderly. Int J Group Psychother 1990;40:353–63.

39. Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, Orrell M, Davies S. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;CD001120. 40. Bourgeois MS, Dijkstra K, Hickey EM. Impact of communication

interaction on measuring self- and proxy-rated depression in dementia. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 2005;13:37–50.

41. Coleman PG. Uses of reminiscence: functions and benefits. Aging Ment Health 2005;9:291–4.

42. Williams CL, Tappen RM. Exercise training for depressed older adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health 2008;12: 72–80.