一個國中生體驗晚期英語浸潤式教學的個案研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) A Case Study of a Junior High School Student’s Initial Learning Experiences in a Late English Immersion Program. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English,. 立. 政 治 大. National Chengchi University. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by Wan-chun Chao May, 2014.

(3) To Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh 獻給我的恩師葉潔宇教授. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(5) Acknowledgments. Devoting all effort to the thesis composition, I am finally allowed to express my gratitude to those who have believed in and supported me. My deepest appreciation goes to my advisor, Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh, for her continuous support,. 治 政 suggestions, inspiration, and encouragement for this work. 大 With her reading my 立 ‧. ‧ 國. Dr. Yeh.. 學. draft patiently and offering valuable feedbacks, I have been greatly benefited from. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank Dr. Chen-kuan Chen, Chin-chi. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. Chao, and Dr. Hsueh-ying Yu, for reading my drafts and giving me constructive. i n U. v. comments and warm encouragement. Also, I want to thank Chung-hsien Wu and. Ch. engchi. Ruo-shi Wang for offering me helpful advices for this thesis. My special thanks are extended to Shelly, the participant of this study. Without her sharing of learning experiences, I would have not been able to bring my work to a successful completion. In addition, I am also grateful to my friends, Claire Chen, Claire Liu, Emily Chen, Renee Wang, and Mirenda Hwang. It is their mental support and encouragement that gives me the oxygen I needed when I felt frustrated in completing this work. iv.

(6) Lastly, I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. It is their unconditional support that makes my pursuit of master degree possible.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Dedication Page........................................................................................................iii Acknowledgements...................................................................................................iv Chinese Abstract........................................................................................................v English Abstract.......................................................................................................vii. 治 政 Chapter One: Introduction.....................................................................................1 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. Chapter Two: Literature Review............................................................................5 2.0. Introduction.....................................................................................................5. ‧. 2.1. An Introduction to Immersion Education........................................................5. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. 2.2. Variation of Immersion Programs...................................................................7. i n U. v. 2.3. Learning Outcome of Immersion Programs....................................................9. Ch. engchi. 2.4. Proficiency Gap and Immersion Programs...................................................13 2.5. Conclusion ....................................................................................................16 Chapter Three: Methodology ...............................................................................19 3.0. Introduction...................................................................................................19 3.1. Criteria of Choosing the Participant..............................................................19 3.2. The Context ..................................................................................................20 3.3 The Participant...............................................................................................22 vi.

(8) 3.4. Method..........................................................................................................24 3.4.1. Diary ..................................................................................................25 3.4.2. Interview.............................................................................................26 3.4.3. Informal Interview/Conversation ......................................................27 3.5. Procedures.....................................................................................................28 3.6. Data Analysis ...............................................................................................30. 政 治 大. Chapter Four: Results ..........................................................................................31. 立. 4.0. Introduction ..................................................................................................31. ‧ 國. 學. 4.1. The First Stage: “I Am awesome.” ...............................................................34. ‧. 4.1.1. Enjoying the New Environment ........................................................34. Nat. io. sit. y. 4.1.1. Fitting in the Community ...............................................................35. er. 4.1.3. Shelly’s English Proficiency .............................................................37. al. n. v i n 4.2. The Second Stage:C “Not h ebacking n g coff,h Ii AmUStill Awesome.”.......................43 4.2.1. Challenging Moments: The Social Studies and Math Class…..........44 4.2.2. Delightful Events: The Science Class ...............................................49 4.2.3. Obligated Routine: Numerous Homework, Quizzes, and Tests.........51 4.3. The Third Stage: Unresolved Conflicts-Concerns for L1 Development....54 4.3.1. The Goals and the Focuses of the International School Curriculum...................................................................................................54 vii.

(9) 4.3.2. Shelly’s Opinions to the Contents of the Chinese Course.................56 4.3.3. Shelly’s Responses to the Evaluation Method in the Chinese Course ..........................................................................................................58 4.3.4. Mr. Chen’s Teaching Philosophy.......................................................61 4.4. Summary of the Findings .............................................................................67 Chapter Five: Discussion and Conclusion...........................................................69. 政 治 大. 5.0. Introduction ..................................................................................................69. 立. 5.1. Factors Leading to Good Adjustment ..........................................................70. ‧ 國. 學. 5.1.1. The Attitude toward and the Proficiency of English.........................70. ‧. 5.1.2. Familiarity toward the Environment and the Academic Content.......73. Nat. io. sit. y. 5.1.3. Learning Dynamics…………………………………………………75. er. 5.1.4. Self-Efficacy, Challenges, and Coping Strategies …………….........77. al. n. v i n C h ...............................................................80 5.2. Factors Hindering the Adjustment engchi U. 5.3. Implication of This Study…………………..................................................83 5.4. Limitation of This Study.. ……………........................................................87 5.5. Recommendation for Future Research ………………………………….....88 5.6. Conclusion ....................................................................................................89 References ...............................................................................................................91. viii.

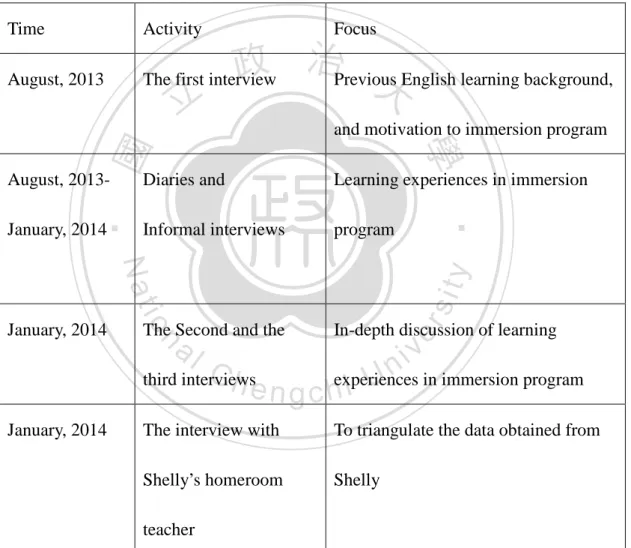

(10) LIST OF TABLES. Table 1. Data Collecting Procedures…………………………………………………29. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. ix. i n U. v.

(11) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士班 碩士論文題要. 論文名稱: 一個國中生體驗晚期英語浸潤式教學的個案研究 指導教授: 葉潔宇博士 研究生: 趙婉君 論文題要內容:. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 本研究探討一個國中生在晚期英語浸潤式教學中的體驗,研究議題包括. ‧. 學習者的學習歷程、學習者所遇到的困難、造成困難的因素、以及學習者如. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. 何面對並解決困難的過程。. i n U. v. 本研究方法採用質性個案研究,研究工具為日記,訪談,以及研究筆記。. Ch. engchi. 研究結果發現,學習者很快就適應沉浸式教學的環境。此研究中指出,學習 者把英文視為工具而非學科的的態度,她優異的英文能力,她對環境以及課 程內容的熟悉度,以及她的課程學習與她的期待相符,這些因素與她良好的 適應狀況習習相關。然而,本研究也發現,在非語言課程中某些老師使用英 文授課之能力對學生的學習帶來負面影響,例如:老師的口音以及老師在使 用英文授課時的能力不足為兩個影響學習者學習語言之因素;除此之外,學 習者對於寫功課的負面情緒也影響了學習的品質。儘管如此,學習者卻能將 x.

(12) 這些挑戰迎刃而解,本研究發現學習者與同儕間合作學習的互動模式,以及 學習者的高度自我效能與學習策略應用的能力,成功使該學習者克服上述的 學習困難。唯一令學習者不滿的是她的母語課程,研究結果顯示重覆的課本 內容、偏向背誦式的教學方式與考試取向與學習者期待不符合,進而造成她. 政 治 大. 對於自己的母語發展不甚滿意。. 立. 本研究最後針對未來有興趣進入沉浸式教學中的學生、學生家長、以及. ‧ 國. 學. 在教育端的老師與課程設計者提供意見,以期能使學生在沉浸式教學環境中. ‧. 的學習更加豐富。. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xi. i n U. v.

(13) Abstract. The present study explores a junior high school student’s initial learning experiences in a late English immersion program, and it discusses the learner’s learning process, the encountered difficulties, factors leading to the difficulties, and coping strategies.. 立. 政 治 大. A qualitative research method was employed in this case study. Data were. ‧ 國. 學. collected through diary entries, interviews, and research notes. Results of the. ‧. study indicate that the learner made rapid adjustment to the immersing context,. Nat. io. sit. y. and the finding suggests that factors like regarding English as a tool rather than a. er. subject, having a high level of English proficiency, being familiar with the. al. n. v i n C h contents, learningUin an environment that learning environment and the course engchi matches the learner’s expectation are facilitative factors leading to the learner’s effective adjustment. On the other hand, the present study also finds that inadequate level of some non-language-course teachers’ English proficiency is hindering to the learner’s adjustment. For instance, the teacher’s accent and the ability to explain a concept through comprehensible language are two language problems hindering learning acquisition. In addition, the learner’s negative xii.

(14) emotion toward homework also poses a threat to the learning. Nonetheless, the cooperative and collaborative interaction between the learner and the peers, and her high sense of self-efficacy coupled with her flexible learning strategies are influential in helping the learner overcome the above challenges. However, the. 政 治 大. mismatched expectation of the learner’s L1 development in the Chinese course. 立. remains a problem. The overlapped content in the textbook and the requirement of. ‧ 國. 學. rote learning in teaching and testing result in the learner’s dissatisfaction of L1. ‧. development.. Nat. io. sit. y. Lastly, implications and suggestions developed from the discussions were. n. al. er. provided for students, parents, teachers, and curriculum designers to make. Ch. engchi. immersion programs more fruitful for students.. xiii. i n U. v.

(15) Chapter One INTRODUCTION. There has been an increasing interest in English learning in Taiwan, for English has been widely used in science and commerce and is regarded as the language that offers access to the world. Also, mastering a second language has been considered as a stepping stone for educational pursuit and socio-economic advancement in Asian. 政 治 大. areas, such as China, Hong Kong, Korea, and Taiwan. According to Taiwan’s Ministry. 立. of Education (2009), English learning is one of the major tools to increase workforce. ‧ 國. 學. efficiency and international competiveness (Tang, 2011). In response to the trend of. ‧. globalization, Taiwan, like many other Asian competitors, also shows keen concern to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. the need of the communicative ability, which could be seen in the government’s support in primary English curricula for all students and parent’s efforts in offering. al. n. v i n C heither through private their children English learning e n g c h i U institutions or tutoring hours. (Chen, 2013). Among different means of English learning methods, acquiring a high level of English proficiency through immersion programs remains popular around Asian areas, and Taiwan is not immune from the English fever (Krashen, 2003). Immersion education in Taiwan shows its appearance in both public and private institutions, mostly found in private educational system. However, research related to immersion education in Taiwan is very rare, and the research focus is limited to 1.

(16) the investigation of learning outcome or cultural issues. For example, possible impacts of partial English immersion program on kindergarteners are discussed in Chen’s study (2006), and the findings suggested that parents’ and educators’ worry about the devaluation of learners’ native language and culture. On the other hand, studies concerning immersion programs in ESL environment indicate that students who begin immersion education in secondary level are likely to experience the so-called “ language proficiency gap.” It refers to a lack of L2 linguistic. 政 治 大. competences that students might experience because these students, also known as. 立. late immersion students, switch from L1-medium instruction to L2-medium. ‧ 國. 學. instruction at grade 7 or 8 (Johnson and Swain, 1994), and it is beneficial for these. ‧. students to attend sheltered class as a transition to accommodate the use of second. y. Nat. er. io. sit. language as a learning tool (Snow, 2001).. Due to the foreseeable difficulties students might encounter, there is a need to. al. n. v i n conduct a process-oriented study toC explore students’ learning experiences h e nsecondary gchi U here in Taiwan. This study, therefore, intends to explore a junior high student’s learning experiences in acquiring both content and language in a late English immersion program in Taiwan, an EFL context. This study aims to reveal how the learner experiences a new immersing context, makes sense of learning activities, and deals with challenging learning tasks. Also, the underlying factors that involve in and influence the student’s learning situation is discussed. By collecting diary and 2.

(17) interview data through a qualitative case study approach, learner’s perception and affective factors that are hidden to external observers and inaccessible to quantitative instruments will be unearthed. It is hoped that this study could provide a further understanding of how students adjust to an English-medium content learning environment, thereby, offering insight for educators or learners who are currently involved in a late immersion program. To guide the study, the following three research questions are formed.. 政 治 大. 1. What kind of (critical) learning events did the learner experience?. 立. 2. What kind of difficulties did she encounter? If there is any?. ‧ 國. 學. 3. How did she overcome the difficulties?. ‧. 4. What factors would facilitate and hinder the learner’s adjustment?. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 3. i n U. v.

(18) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 4. i n U. v.

(19) Chapter Two LITERATURE REVIEW. 2.0. Introduction This section consists of five parts. It begins with the definitions of immersion education, and is followed by characteristics and variations of immersion programs.. 政 治 大 factors influencing students’ 立 learning outcome are reviewed.. Subsequently, the learning outcome of immersion programs is examined, and finally,. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. 2.1. An Introduction to Immersion Education. sit. y. Nat. The concept of teaching and learning the target language for academic purposes. io. n. al. er. is labeled with different terms, and yet, refers to the same thing. Freeman (2000). i n U. v. uses content-based instruction to indicate such phenomena, while Marsh (2002). Ch. engchi. employees the term, content and language integrated learning (CLIL). And still, the term, immersion education, is widely adopted for programs offering second language as the medium for content leaning. In higher education, this kind of learning is labeled with English taught program (ETP) or English as medium of instruction (EMI). Immersion programs are a form of bilingual education that aims for additive bilingualism by offering at least half of the content instruction through the target language (Lyster, 2007; Swain &Johnson, 1997). Immersion programs 5.

(20) follow the strong version of communicative approach, also known as content-based instruction, which is a kind of language instruction featuring the use of subject matter as the content for second language teaching and learning (Freeman, 2000; Snow, 2001). Immersion programs are one type of content-based models that integrate language and content learning with more emphasis on the content. In the following description, the author will use the target language and second language (L2) interchangeably to indicate the language used as medium of instruction in immersion programs.. 立. 政 治 大. The prototypical immersion program was first implemented in Canada in 1965. ‧ 國. 學. (Cummins, 2000; Genesee, 1987; Snow, 2001; Swain & Johnson, 1997) with the. ‧. goal to cultivate learners’ L2 proficiency by using the target language as a vehicle. y. Nat. er. io. sit. for instruction. The rationale for immersion programs could be drawn from input hypothesis proposed by Krashen (1984). Students in an immersion classroom. al. n. v i n C h that is tailored for receive abundant input of target language e n g c h i U students’ level, and thereby comprehensible input (Ellis, 1994). In Krashen’s word, “comprehensible subject-matter teaching is language teaching.” (1984, p. 62). Some may use the immersion label to describe programs that exclusively employee L2 as language instruction. Yet, according to Fortune and Tedick (2008) genuine immersion program should follow the principles listed below. . instructional use of the immersion language (IL) to teach subject 6.

(21) matter for at least 50% of the preschool or elementary day (typically up to grade 5 or 6); if continued at the middle/secondary level a minimum of two-year long content courses is customary, and during that time all instruction occurs in the IL; . promotion of additive bi- or multilingualism and bi- or multilingual literacy with sustained and enriched instruction through at least two languages;. . 政 治 大. employment of teachers who are fully proficient in the language(s). 立. they use for instruction;. ‧ 國. 學. . reliance on support for the majority language in the community at. ‧. large for majority language speakers and home language support for. y. Nat. er. io. . sit. the minority language for minority language speakers; clear separation of teacher use of one language versus another for. n. al. i n C sustained periodsh of time. (pp.9-10).U engchi. v. 2.2. Variation of Immersion Programs In many countries, immersion may function to achieve diverse educational goals and as a response to socio-economic needs. Immersion programs are originated from Canada, aiming to develop high level of French immersion program and attain academic competence without sacrificing students’ native language. 7.

(22) Immersion programs, as an effective second language learning method, also extend its development worldwide. This method of language and content integrated learning is borrowed and adopted to accommodate to the context of borrower countries, such as Spanish immersion program in Culver city, U.S.A., English immersion program in Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan. Thus, a variety of immersion models, differing from entry age to percentage of target language instruction, have been developed, containing the core features mentioned above (Fortune& Tedick, 2008). Based on. 政 治 大. Johnstone (2007) and Snow (2001), there are six main models, early total immersion,. 立. early partial immersion, delayed/middle total immersion, delayed/middle partial. ‧ 國. 學. immersion, late total immersion, late partial immersion. In early immersion model,. ‧. the onset of L2 medium instruction begins in kindergarten or the start of primary. y. Nat. er. io. sit. schooling. The delayed or middle immersion model usually begins in the middle of primary school, such as grade four. Late immersion model usually begins until the. al. n. v i n C hwith adults (Cummins, start of secondary school; it also deals e n g c h i U 2000; Johnstone,. 2007). In partial immersion model, it usually provides 50% of instruction in students’ first langue and 50% of instruction in the target language (Genesee, 1985). Simply put, one variation of immersion programs depends on students’ entrance age, resulting in different amount of exposure to target language; the other depends on the percentage of target language instruction. 2.3. Learning Outcome of Immersion Programs 8.

(23) The success and effectiveness of various immersion programs have reached some consensus in the field of second language education. Ellis (1994) compares research about French immersion (Genesee, 1985 ;1987; Swain & Lapkin, 1982) and concludes that immersion students generally develop normal level of L1, high level of L2 and attain the same or better level in academic subjects. Evaluation of learning outcome also shows that total immersion results in better learning outcome than partial immersion, and early immersion does better than late immersion. A more. 政 治 大. detailed picture of what immersion programs can help students in developing. 立. linguistic, academic, and cognitive competence will be delineated in the following. ‧ 國. 學. section (Cummins, 2000; Lazaruk, 2007).. ‧. Firstly, general research findings consistently show positive learning outcome. y. Nat. er. io. sit. of students’ L2 development in terms of literacy and fluency (Harley, Allen, Cummins, Swain, 1991; Lazaruk, 2007). More specifically, students acquire high. al. n. v i n C hcompetence in L2 U level of discourse and strategic e n g c h i (Swain, 1985) without sacrificing their progress in L1 development and academic achievement, hence, additive bilingualism. However, students’ target language is not well-developed with respects to productive skills and accuracy. Adopting native speakers’ proficiency as evaluating criteria, general finding of early French immersion indicates that early immersion students’ receptive skills have better development compared to productive skills. In 9.

(24) Genesee’s study (1987) of immersion students’ linguistic accuracy, students are found to have inadequate ability in terms of phonology, vocabulary, and grammar of target language development. In the same vein, students are found to approach native-like listening comprehension and reading ability but show weakness in oral ability, especially with respects to grammar and lexicon (Cummins, 2001; Swain, 1996). Although limited grammatical proficiency of L2 is acquired by students, Genesee (1985) points out that compared to non-immersion students, students who. 政 治 大. attend all types of immersion programs are reported to achieve high level of target. 立. language proficiency in all aspects of French. Furthermore, a considerable amount. ‧ 國. 學. of research comes to the same conclusion that accumulated hours of target language. ‧. instruction correlates with high level of L2 proficiency. Turnbull, Lapkin, Hart, and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Swain’s (1998) study discusses the impact of total instruction time in target language proficiency by adopting Senior French Proficiency Test Package for French. al. n. v i n C h performance with immersion, which evaluates the linguistic e n g c h i U respects to four skills. The result indicates that early immersion students outperform middle and late immersion students predominately in speaking ability. Also, it is argued that late immersion students demonstrate a more homogenous ability, which could possibly be attributed to the fact that less motivated students leave late immersion program before grade 12. As for immersion students’ academic development, a number of studies show 10.

(25) that immersion students achieve the same or higher level than their non-immersion counterparts (Genesee, 1987; Swain and Lapkin, 1982). In Trites and Reeder’s (2001) study, quasi-experimental research is conducted with the aims to explore middle immersion students’ mathematic achievement from a French immersion program in Vancouver, Canada. Two groups of students are compared. One is the treatment group who receives 80% target language instruction and 20% native language instruction; the other is the comparison group who receives 50% of target language. 政 治 大. and native language. Both of the group receive target language instruction, French,. 立. since grade 4, and are tested at grade 6 in students’ native language, English. Two. ‧ 國. 學. points are made in Trites and Reeder’s (2001) result section. First, the mathematic. ‧. performance of treatment group is more advanced than comparison group. In other. y. Nat. er. io. sit. words, the intensity, defined as more exposure, of target language instruction lead to positive effect of mathematic acquisition. Secondly, the result proves the. al. n. v i n C h from one language transferability of retrieving knowledge e n g c h i U to another,. interdependence hypothesis, in Cummins’s term (1984). Yet, students’ academic performances in language-rich subjects remain unexplored in Trites and Reeder’s study (2001). A picture with the integrity of immersion student’s academic performance could be found in Marsh, Hau, and Kong’s (2000) study of students’ academic growth in a late English immersion programs in Hong Kong. This study investigates students’ performance on both language (Chinese and English) and 11.

(26) non-language subjects. Students in the study appear to show poor performance in non-language subjects such as history, geography, and science which are language-rich in nature. Such negative effect of learning content through target language could be attributed to inadequate level of target language proficiency. Students may have to pay excessive attention in order to master basic terminology in a target language, precluding students to have deeper understanding of the content of subject in specific area. The result suggests that prior English skills could minimize. 政 治 大. negative effect, showing consistency with the core concepts of threshold hypothesis. 立. (Cummins, 1987).. ‧ 國. 學. The hypothesis suggests that students with minimum level of both L1 and L2. ‧. proficiency are more likely to benefit from immersion education and avoid. y. Nat. er. io. sit. inadequate development of both languages. Another comment made by Marsh, Hau, and Kong’s (2000) is that students’ academic performance on mathematic shows. al. n. v i n Cand little negative effect because learning mathematic relies more on h eteaching ngchi U. symbolic terminology rather than linguistic term. Also, students’ prior mastery of math before the entry of immersion program seems to be another reason. As for cognitive development, research associated with bilingualism reports that bilingual children possess heightened mental flexibility, creative thinking skills, enhanced metalingustic awareness, and greater communicative sensitivity (Baker, 2006; Lazaruk, 2007). However, according to the threshold hypothesis, positive 12.

(27) cognitive effect is contingent, as suggested in Cummin and Swain’s study (1986). Students who develop age-appropriate competence of one language are regarded to pass the first threshold, which enables the students to avoid negative cognitive effect. It is only when students who attain age-appropriate level in two languages, that is, balanced bilingualism, can the students glean the benefits of bilingualism (Cummin & Swain, 1986; Lazaruk, 2007; Marsh & Hau, 2000). In the context of total immersion program, Cummins (1980) declares that the level of language proficiency. 政 治 大. in two languages is even higher for students to benefit from bilingualism since. 立. students are exposed to more L2 instruction.. Nat. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.4. Proficiency Gap and Immersion Programs. er. io. sit. In addition to target language as medium of instruction, the entry age and the nature of subject matter both have impact on students’ learning. Early immersion. al. n. v i n C h are more like L1Uacquisition in the sense that they students’ experiences of schooling engchi are educated to develop academic literacy through and are taught to socialize into classroom culture via a second language. Although what early immersion students face at school are new language and new content, the knowledge they have to deal with is concrete world knowledge, resulting in fun and new learning. As students progress through education, on the other hand, the academic content becomes more abstract and cognitively demanding (Cummins & Swain, 1986). In other words, late 13.

(28) immersion students have to tackle both new and abstract concept as well as complex language. They are consciously aware of the language gap in understanding the academic content and completing academic tasks through a second language, which they only learned as a subject rather than used as a communicative tool before the entry of an immersion program. Compared to what late immersion students can achieve in their L1, such as understanding abstract knowledge and communicate through sophisticated language, these students may encounter frustration in terms of. 政 治 大. inability to write extensively, and to comprehend lecture or textbook in the L2. This. 立. situation is what Johnson and Swain (1994) called, “language proficiency gap”,. ‧ 國. 學. which happens when late immersion students who switch from L1-medium. ‧. instruction to L2-medium instruction. This gap consists of both linguistic and. y. Nat. er. io. sit. academic competence that are necessary for students who plan to acquire curriculum content through a second language and regard curriculum content as a way to. al. n. v i n Cstudents acquire a second language. Although second language education as h e n receive gchi U a subject before their entry of a late immersion program, the objective, conversational proficiency, adopted by a general second language program remains inadequate and inappropriate for academic learning. Such situation rarely turns positive even with the aid of a dictionary. To bridge such proficiency gap, learners’ motivation and self-confidence play a major role. Besides, the use of students’ L1 and provision of intensive bridging courses are necessary to help students cross the 14.

(29) language threshold level (Johnson and Swain, 1994). In response to the concern of proficiency gap experienced by late immersion student, Enrichment Program (EP) becomes popular to make up for the reduction of English exposure. Li (2008) conducts a study that explores the effectiveness of Enrichment Program in Hong Kong for students who are receiving Chinese as Medium of instruction in junior high school (grade 7-9), and are planning to receive English as medium of instruction in high school (grade 10-12). The intervention lasts for three years,. 政 治 大. beginning at the start of grade 7 and continues until grade 9, during which, students. 立. are found to make improvement in English skills and subject knowledge; yet, the. ‧ 國. 學. effectiveness remains limited. The result indicates that EP students show better. ‧. English skills in mathematics and science-related subjects but not in more. y. Nat. er. io. sit. language-rich subjects such as history and geography. Besides, due to teacher-directed way of teaching in EP, students are found having a lack of higher. al. n. v i n order thinking. Even so, the C implementation h e n g c hof iEPUin Hong Kong shows responses to the notion of proficiency gap that late immersion students may experience. EP serves as an attempt to suit students need where prosperous immersion education has been developed at secondary school in Hong Kong. Another type of transition programs are sheltered classes, where content teachers instruct the content courses in a second language. Students consist of ESL learners. The teachers promote students’ second language proficiency through the use of various instructional strategies and 15.

(30) materials, such as introduction of key terms and useful expression in the beginning of class (Snow, 2001). Although no difference is found in terms of second language proficiency between sheltered students and traditional ESL and EFL students, sheltered students are said to have greater confidence, leading to interactive participation in sheltered class. However, these programs are not an educational panacea for second language learning is complex and multidimensional.. 2.5. Conclusion. 立. 政 治 大. A number of immersion programs targeting Chinese, English, French, Spanish,. ‧ 國. 學. or any other language as medium of instruction have been implemented worldwide,. ‧. and much research has been done to prove the effectiveness of what immersion. y. Nat. er. io. sit. education can bring to students with respects to advanced linguistic proficiency and average academic competence (Cummins, 2000; Genesee, 1985; Hoare and Kong,. al. n. v i n C2008; 2008; Lambert and Tucker, 1972; Li, and Lapkin, 1981). However, it h e Swain ngchi U. does not mean that immersion students are free of learning difficulty. The challenges faced by late immersion students due to proficiency gap (Johnson & Swain, 1994) are an indicator, which shows the students’ need for teacher support during the transitional year or students’ first contact with immersion programs. Thus, more research investigating students’ learning experiences in late immersion programs needs to be done. 16.

(31) In addition, most of research results are concluded from immersion model in second language contexts, to name a few, early French immersion program in Canada, late immersion English program in Hong Kong. Investigation about immersion programs in foreign language contexts remains scarce, particularly in terms of late immersion model for secondary students. Moreover, studies concerning immersion programs mainly focus on students’ learning outcome (academic growth and linguistic proficiency) either through quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method.. 政 治 大. Only few studies focus on leaner’s learning process in participating in an immersion. 立. program (De Courcy, 2002), and nearly no process-oriented study is conducted to. ‧ 國. 學. address late immersion related issues in an EFL context, such as Taiwan. This study,. ‧. therefore, starts from the research gap in the field of immersion education as an. y. Nat. er. io. sit. attempt to shed light on how learners might encounter and tackle learning events, both positive and negative, in a late immersion program.. n. al. Ch. engchi. 17. i n U. v.

(32) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 18. i n U. v.

(33) Chapter Three METHODOLOGY. 3.0. Introduction This chapter presents a detailed account of the methodology adopted in this study, containing sampling techniques, description of the selected case, the research. 政 治 大. context, research design, and data analysis. The researcher first explains why the. 立. case is chosen. Subsequently, the participant’s background and the learning. ‧ 國. 學. community that she belongs to are discussed. Followed by that, the methods for data. ‧. collection are introduced, inclusive of different types of instruments and the. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. procedures, and finally, the data analyzing process is elaborated in the last section.. Ch. 3.1. Criteria of Choosing the Participant. engchi. i n U. v. The purpose of this study is to reveal how a learner experiences a late immersion program and adjusts to an English-medium instructional environment. In order to address the research questions, Shelly is selected as an information-rich case following the notion of purposeful sampling (Patton, 1990). Her experiences might provide informative sources due to the following reasons. The researcher, at the same time, Shelly’s private tutor, had a brief conversation with Shelly about her 19.

(34) educational plan next year. It was May, 2013. The researcher was told that Shelly was planning to transfer to an immersion program when she turned grade 8. The brief conversation aroused the researcher’s interest in exploring an eighth grader’s learning process in a late total immersion program. According to that conversation, Shelly explained that her mother thinks it could be important and helpful for her to transfer from a regular secondary school to an international school, a late total immersion program, because she expects Shelly to get a bachelor degree abroad and. 政 治 大. the international school functions to prepare her for this kind of educational pursuit.. 立. the transfer happened at the time of data collection.. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat. 3.2. The Context. 學. ‧ 國. After a family discussion, Shelly is persuaded to follow this educational plan, and. K school, a private bilingual school, offering programs from kindergarten to. al. n. v i n C has the research site.UK school provides four grade 12 in northern Taiwan is selected engchi types of programs including kindergarten, elementary school, secondary school, and international school. The first three programs offer identical curriculum of regular public schools, including both Chinese and English classes as well as other non-language subjects; yet, a minor difference could be found in English classes. Students are provided with more instructional hours of English classes and more advanced content of English, including grammar, vocabulary, and literary work. 20.

(35) Note that both secondary school and international school in K school recruit students from grade 7 to grade 12; yet, the medium of instruction is different. The secondary school employs Chinese as the medium of instruction for every subject, except for English class. Apart from Chinese class, the international school, a form of immersion program, adopts English as medium of instruction with an aim to prepare students for overseas study. According to the features concerning entrance age and percentage of instruction in L2, the international school that Shelly attends is a late,. 政 治 大. total immersion program, and hence, the research site is selected.. 立. Among various programs, the international school receives the researcher’s. ‧ 國. 學. major focus because it provides immersion education for students from grade 7 to. ‧. grade 12, which Shelly is involved in. The international school from grade 7 to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. grade 9 is available for students who completed elementary school education while grade 10 to grade 12 requires students to complete junior high school education.. al. n. v i n C hinternational schoolUhave to pass the English Students who want to enter the engchi. proficiency test held by the school. Impressive academic reports from the previous academic year are also necessary before the school committee approves a student’s entrance. The international school adopts the Canadian immersion model in terms of curriculum designs and goals. For instance, the school provides nearly a hundred percent English-mediated instructional environment and aims at additive 21.

(36) bilingualism by offering both Chinese (Shelly’s L1 in this study) and English (her L2 in this study). The school also embraces both Western and Asian educational styles to prepare students for pursuing college education overseas. The courses offered include English, Chinese, Science, Math, Social Studies, Fine Arts, Health and PE, and elective courses. About ninety percent of the above mentioned courses are taught in English, except for the Chinese courses that take up 10 % of the whole curriculum. In addition to the environment characterized by English as a medium of. 政 治 大. instruction, the school is different from public schools in many other ways.. 立. According to the introduction of K school from the official website, the school puts. ‧ 國. 學. more emphasis on cultivating students’ multiple talents (e.g., daily life skills,. ‧. physical fitness, artistic conception, and so on). Students are required to participate. y. Nat. er. io. sit. in a variety of events such as hiking, concerts, and so on. K school also allows their students to have more time to engage in exploratory activities, such as a one-week. al. n. v i n CTaiwan, field trip to Shei-Pa Natioanl Park in are relatively uncommon in the h e n which gchi U test-oriented public education system. Students are also expected to develop academic competence, creativity, critical thinking, and interpersonal skills.. 3.3. The Participant This section provides background information about the selected participant, Shelly, a grade 8 student in an international school of K school at the time of data 22.

(37) collection. Shelly receives all her education from K school since kindergarten. That is, she had attended K school’s kindergarten, elementary school, and secondary school. However, after she completed grade 7, she transferred to its international school, which offers immersion education. It is worth noting that Shelly’s parents had a discussion about the transfer when Shelly completed education in elementary school and when she was about to become a seventh grader. Concerning Shelly’s development of L1 literacy, the parents finally decided to have Shelly go to the. 政 治 大. secondary school first and then attend the international school at grade eight. As a. 立. result, Shelly enters the program a year later than most of the immersion students.. ‧ 國. 學. Before attending the immersion program, what Shelly learned in K school. ‧. about Chinese, Science, Math, Social Studies, and Art are similar to that learned by. y. Nat. er. io. sit. public school students. What makes Shelly different from most of public school students is that she receives English instruction as a subject from both native English. al. n. v i n C h from K school, and speakers and Taiwanese teachers e n g c h i U the content of English classes is more advanced in terms of difficulty level.. Shelly comes from a well-educated family. Her parents have overseas degrees, and they both work for K school as managers in different programs. Being brought up in a family like this, Shelly is always a high achiever in class and is aware of her future career and educational goals. Although the teachers often pay compliment to her overall academic performances, Shelly is not that confident. Shelly’s mother 23.

(38) expects her to achieve more. Under the influence of Shelly’s mother, who expects her daughter to take the same path as she did, Shelly is consciously aware of her educational goals. She will pursuit higher education overseas, and she plans to engage in childhood education as a career. Thus, Shelly follows her parents’ suggestions and entered the immersion program. Although Shelly was going to enter an English learning environment, she was free of anxiety before the new semester begins. Considering the possible language proficiency gap and the new immersing. 政 治 大. context featuring L2-medium instruction, the researcher is interested in how Shelly. 立. is going to make sense of the classes and tackle challenging tasks and difficulties.. ‧ 國. 學. Note that, Shelly’s homeroom teacher, at the same time, the Chinese teacher, was. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 3.4. Method. ‧. also invited to participate in this study to triangulate Shelly’s data.. al. n. v i n C hShelly, experiencesUlate immersion education In order to reveal how the learner, engchi. before and during the first semester, multiple data sets were collected and a qualitative case study approach was adopted. This study draws on three kinds of instruments:. weekly diaries, interviews, and informal interviews/conversations.. Given the double role, that is serving both as a private tutor and an observer, the researcher plays; research notes taken from informal interviews with Shelly were also utilized as research data. 24.

(39) 3.4.1. Diary The participant of the study, Shelly, was asked to keep a weekly diary about her learning events at the first semester in the immersion program. According to Bailey and Ochsner (1983), diary, as a valid research tool, functions to report the diarist’s own perceptions of second language learning experiences including affective factors, language learning strategies, and challenges. The purpose of a diary is to document the first person account of learning experiences (Bailey, 1990), which reveals the. 政 治 大. facet of experiences that may be unavailable for external observers. Thus, diary is. 立. experiences, interpretation of learning events.. 學. ‧ 國. regarded as the major instrument for this study, manifesting the learner’s. ‧. From September 2013 to January 2014, the researcher collected approximately. y. Nat. er. io. sit. twenty diary entries. Concerning the amount of the participant’s homework from the school, the researcher only asked the participant to recall her experiences on. al. n. v i n C hthe weekly introspection weekend for diary writing. With e n g c h i U and retrospection, the richness of data is increased. Also, regular collection of Shelly’s diaries documenting her feeling, perspectives, and belief in the immersion environment is utilized for the researcher to examine, categorize, and analyze significant events, and thus illustrate her learning experiences in depth.. 25.

(40) 3.4.2. Interview Semi-structured interviews were conducted three times during the first semester, and interview protocols were designed in advance. Due to the fact that Shelly is a teenager whose attention span is more limited than adults, each interview lasted for 30-60 minutes. Since the participant shares the same native language, Chinese, with the researcher, Shelly was allowed to use either Chinese or English to express herself. In addition to the language, the fact that the researcher has been a private. 政 治 大. tutor for Shelly for the previous two years helps to develop rapport.. 立. The first interview was held in August, 2013. It is before Shelly enters the. ‧ 國. 學. program with the aim to understand her previous English learning experiences, her. ‧. motivation to transfer from the regular secondary school to the immersion program. y. Nat. er. io. goals.. sit. at grade seven, her preparation before the program starts, and her future educational. al. n. v i n C h were conducted U The second and the third interviews e n g c h i during the first semester.. The primary goal of these interviews are to discuss the learning experiences in the immersion program and explore the issues of language and academic development based on the events or situations documented in Shelly’s diary. Also, the information collected from the first interview act as a base for comparison of the second interview data and diary. In order to triangulate Shelly’s statements, a semi-structured, two-hour 26.

(41) interview with Shelly’s home teacher was also held in the end of Shelly’s first semester in the immersion program in K school.. 3.4.3. Informal Interview/Conversation The researcher, who at the same time, the private tutor for Shelly, visited her twice a week during school days at the time of data collection to assist Shelly to complete her homework. The dual roles of the researcher and the tutor allowed the. 政 治 大. researcher to participate in Shelly’s homework completing process, during which the. 立. researcher had the chance to initiate conversations with her and double check on the. ‧ 國. 學. appropriateness of the researcher’s interpretation of the written diary without delay.. ‧. In the mean time, given that the duty of the tutor is to assist Shelly to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. complete her school work, the researcher/ private tutor also had the opportunities to observe Shelly’s language performance, academic behavior, and her feelings during. al. n. v i n C h to complete homework. tutoring hours when she managed e n g c h i U Research notes were. taken during the torturing hours twice a week for the first semester, in which casual conversations with Shelly were documented. These data were included with the aim of triangulating the primary data. Besides, the researcher often initiated casual conversations with Shelly by asking questions, probing for more detailed and descriptive answers. Finally, the researcher regards her one-on-one instruction to and company with Shelly every 27.

(42) week as valuable opportunities to confirm the messages conveyed through the weekly diaries. A lot of conversations between the researcher and Shelly during tutoring hours were documented in the form of research notes to reinforce the richness of information.. 3.5. Procedures Data for the present research project were collected through three sources,. 政 治 大. diaries, interviews, and informal interviews from August, 2013 to January, 2014.. 立. The following explication reveals the details of data collection (see table 1). First,. ‧ 國. 學. the first interview was conducted before the beginning of the new semester in the. ‧. immersion program. Then, Shelly was given diary forms with clear instruction. y. Nat. er. io. sit. (Nunan and Bailey, 2009), guiding her to record learning events, such as challenges and a sense of fulfillment every week within the first semester. According to the. al. n. v i n schedule announced on the official C website the semester started from h e ofn Kgschool, chi U late August, 2013 to mid-January, 2014, allowing the researcher to collect approximately 20 diary entries. Since the researcher, also the private tutor, had the access to reach the participant every week, informal interviews were conducted in the form of casual conversations when the researcher found the diary data needed more details or clarification. After the collection of primary data, the second and the third interviews were conducted right after the end of the semester for the researcher 28.

(43) to have an in-depth understanding of Shelly’s learning experiences of the first semester. Interview questions were designed based on diary information. Lastly, an interview with Shelly’s homeroom teacher, Mr. Chen, was conducted after Shelly’s final exam.. Table 1. Data Collecting Procedures Time. Activity. August, 2013. The first interview. 政 治Previous 大English learning background, and motivation to immersion program. 學. ‧ 國. 立. Focus. Diaries and. Learning experiences in immersion. January, 2014. Informal interviews. program. sit er. io. The Second and the. In-depth discussion of learning. The interview with. To triangulate the data obtained from. Shelly’s homeroom. Shelly. al. v i n Ch third interviews i U in immersion program e n g c hexperiences n. January, 2014. y. Nat January, 2014. ‧. August, 2013-. teacher. 29.

(44) 3.6. Data Analysis The researcher conducted an inductive approach to examine, categorize, and interpret the data that consists of diary, interviews, and research notes collected from September 2013 to January 2014 in the form of written mode. Among all the data, the primary data, diaries written by Shelly, underwent initial selection and analysis through the researcher’s reconstruction of meaning. It was a process that involved the analysis of the content, context, and form of the diary entries (Pavlenko, 2007).. 政 治 大 not said were taken into consideration. 立 During the analyzing process, the researcher. The first step was to examine the content of diary data. What was said and what was. ‧ 國. 學. attended to the factors lying behind Shelly’s learning events. Next, the researcher. ‧. selected and categorized the data and then identified learning events that showed. sit. y. Nat. significance to Shelly. After that, the researcher analyzed the secondary data, which. io. n. al. er. contained informal interviews with Shelly, research notes, and the triangulating. i n U. v. interview with her homeroom teacher to validate the initial analysis concluded from. Ch. engchi. diary. At this stage, the analysis served as a base for the design of follow-up interview questions. After the completion of the second interview and the third interview, the recordings were transcribed verbatim. These data were examined, categorized, and interpreted again. Themes related to Shelly’s learning experiences occur, demonstrating the results of this study.. 30.

(45) Chapter Four RESULTS 4.0. Introduction Shelly, as a new grade eight student in the international school, took fifteen courses in total in the first semester; yet, the hours of each course in a semester and the teacher’s nationality vary. Among the fifteen courses, six of them account for. 政 治 大. 75% of the entire subject allocation for one semester. There are three language. 立. courses (namely, Chinese, English Literature, and Language Art) and three. ‧ 國. 學. academic courses (namely, Math, Science, and Social Studies). Throughout the. ‧. semester, each of the courses is offered on a five-hour-per-week basis. Such courses. y. Nat. er. io. sit. as English Literature, Language Art, Science, and Social Studies are instructed in English by native speakers of English while the rest of them are lectured in English. al. n. v i n C h mostly Taiwanese. by non-native speakers of English, e n g c h i U Because Shelly spends most of her time engaging in the six courses, and she repetitively addresses the learning experiences in these courses, the finding of this study will place most emphasis on them. As stated in the research questions, the aim of the research is to explore Shelly’s learning experiences in an immersion environment of the first semester.. Through the process of data analysis, the researcher discovers that how Shelly finds 31.

(46) her niche in the new academic environment is closely resembled to the process of acculturation-experiencing euphoria due to the new surrounding, facing and taking challenges, and finally accepting or rejecting the new way of learning. (Note that, the researcher does not mention the fourth stage-full recovery for Shelly’s adjusting experiences, for it might be an ongoing process and there is no obvious evidence reporting Shelly’s full acceptance to the new environment in the first semester.) Therefore, to best capture Shelly’s adjustment to the environment, the. 政 治 大. layout of research findings will be presented in the chronological order.. 立. In order to offer a comprehensive presentation of Shelly’s learning experiences,. ‧ 國. 學. the researcher utilizes the transcription of the interviews, translated diary entries. ‧. (which is originally written in Chinese with a slight degree of code mixing in. y. Nat. er. io. sit. English), and notes taken by the researchers during informal interviews to present Shelly’s learning stories and her feelings to the new surrounding in particular.. al. n. v i n C hthe new environment Generally, there are two factors making e n g c h i U novel to Shelly. Due to the change of instructional language from L1 to L2, she experiences a high degree of novelty in the three academic courses (namely, Math, Science, and Social Studies). Also, the textbooks Shelly is studying are designed by a foreign publisher, so the scope and the content differ from those designed by Taiwan’s local publishers. For example, in terms of history, the section of Chinese dynasty only takes up a chapter in World History for Social Studies, the textbook used by international school 32.

(47) students, while the same section is explained in full details and takes up an entire volume in the history book published by local publishers. The findings of this study are categorized into three sections based on a chronological order for that Shelly’s learning experiences feature a beginning stage of excitement, a subsequent stage of a mixture of enjoyment and challenges, and then a stage of conflicts with the teacher. Note that the categorized stages should be viewed as a continuous emotion of Shelly which does not disappear when she moves. 政 治 大. on to the next stage. In fact, the stages illustrate a distinct state of emotion of Shelly. 立. in a certain period of time. In-depth discussion of Shelly’s responses to the. ‧ 國. 學. curriculum will be elaborated on in the first section-“I am awesome” and the. ‧. second one-“Not backing off, I am still awesome”. The first section delineates. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Shelly’s adjustment to the new environment and important factors influencing her adjustment, her experiences, and her different emotional state. The second one. al. n. v i n reveals Shelly’s responses toCthe courses. Factors that have impact hthree e nacademic gchi U on her attitude, either negative or positive, will be covered.. And for language. courses, it is significant to note the fact that the two English courses are not unfamiliar to Shelly since she has been enrolled in those courses since the start of elementary school. Also, English courses always adopt English as the medium of instruction. Thus, Shelly feels the English courses are not too much different before the transfer. However, the Chinese course is different. Although the Chinese course 33.

(48) employs the same material, the teaching focus and evaluating method are not the same. Shelly reports her point of views by sharing her expectation of Chinese learning and expressing her dissatisfaction with the L1 learning. Descriptions related to Shelly’s feelings about her L1 development in the international school will be dealt with in the third section: Unresolved conflicts-Concerns for L1 development.. 4.1. The First Stage: “I Am Awesome”. 政 治 大. During the first month in the international school, Shelly is full of joy,. 立. excitement, and confidence. This honeymoon like stage, according to the diary, is. ‧ 國. 學. more revealing from the beginning few weeks and fades out a little on particular. ‧. courses later. Analysis of the data reveals that there are three factors influencing. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Shelly’s learning experiences. Firstly, she enjoys some of the classes. Secondly, she soon fits in the communities naturally because of her familiarity with the. al. n. v i n environment. Thirdly, due to havingC a high of English proficiency, she does not h elevel ngchi U struggle too much to position herself in the English-medium-instruction environment.. 4.1.1. Enjoying the New Environment The learner accepts the new environment before long and seems to respond to it with excitement about the new and interesting classes, such as Social Studies 34.

(49) and Science. In her second diary entries, she wrote:. Everything in the international school is conducted in English, including Math, Science, and Social Studies. Fortunately, I have studied in the secondary school for a year, so I am ok with Math. As for Science and Social Studies, the teachers are really interesting. I am attracted to those classes indeed….The teachers in the international school are kind to me, and they are amiable. I’m happy. (The. 政 治 大. second diary of Shelly, September 6, 2013). 立. ‧ 國. 學. Some of the excitement turns into consistent interests toward the subjects. ‧. throughout the first semester. For example, Shelly expresses that she has grown fond. y. Nat. er. io. sit. of the way the science teacher gives lectures. The teacher incorporates fun videos that are related or not related to class materials, such as a cartoon, the Simpson, and. al. n. v i n hands-on activities and jokesCinto Further discussion of the learner’s h ethenclass. gchi U responses to the curriculum will be addressed in the next section.. 4.1.2. Fitting in the Community Secondly, the learner soon finds harmony between her and the people around her and regards herself as a member of the environment, a new academic community to her. She not only holds positive attitude to the teachers but also to her peers in the 35.

(50) international school. She almost blends in the social groups on the first day by making new friends, knowing what to do and not missing anything in school. Shelly is satisfied with her adjusting ability.. I can blend in with the environment on my first day in the international school, and I do not miss anything. I am proud of myself. It’s also nice to meet good friends on the first day. (The first diary of Shelly, August 6, 2013). 立. 政 治 大. Shelly’s remark presents her enjoyable and exciting experiences in the. ‧ 國. 學. international school. The facts that she feels welcomed by the teachers and peers and. ‧. finds the classes are interesting appear to facilitate her enjoyment in learning. In. y. Nat. er. io. sit. addition, Shelly’s homeroom teacher, Mr. Chen, even wrote an email to her mother to compliment on how well Shelly adapts to the new environment. In the interview. al. n. v i n C his vivacious, active, with Mr. Chen, his impression of Shelly e n g c h i U and extrovert. It is not the only reason that explains how soon the adaptation is; the other reasons that help Shelly to feel at home in the new environment is the fact that the learner still stayed in K school and attends the English courses for all students in K school. These courses include English Literature and Language Art, which Shelly has been enrolled in since grade one in elementary school, so she is familiar with the contents, the teachers, and the classmates. In other words, the transferring experience is not 36.

(51) full of new things, but with some familiar English courses and classmates. As pointed out in Mr. Chen’s interview.. …Shelly has an active personality. When I asked some of her classmates who go to the same English classes with her to take care of her…. It turns out that there is no need to do so. She is extrovert enough, and she only transfers from one program to another in the same school. Her ability to adapt is better than. 政 治 大. other transfer students. (The interview with Mr. Chen, January, 22, 2014). 學. ‧ 國. 立. 4.1.3. Shelly’s English Proficiency. ‧. Thirdly, in order to fully explore what roles Shelly’s English proficiency plays,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. the discussion about the learner’s English proficiency will be described through two perspectives—Shelly’s contact with English before the transfer and her language. al. n. v i n using experiences during theCfirst in the international school. h esemester ngchi U. The delineation of Shelly’s previous exposure to English covers three aspects: attitude toward English, English using experiences, and English learning path. To begin with her attitude toward English, it is more about a tool to communicate than a subject to learn. This concept has been rooted before Shelly receives schooling. Shelly spent her early childhood with her parents in Canada when her parents were in pursuit of their master degree there. Shelly recalled the experiences of listening to 37.

(52) English songs and watching English cartoons when she was two years old in Canada.. I learned a little English….like listening to the songs for many times, and I could sing along; watching TV, I knew how to say thank you…. (The first interview with Shelly, August, 31, 2013). 政 治 大. Shelly’s first contact with English happens in an authentic context. However,. 立. Shelly and her parents move back to Taiwan after her parents completed their studies.. ‧ 國. 學. Then she continues such exposure to natural English annually by taking trips and. ‧. visiting relatives with her parents during winter and summer vacations in the U.S.. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Shelly explains that “you have to use English for everything, such as buying things.” These English using experiences make Shelly believes that “English is a language. al. n. v i n C h either in the situation she must learn and use for communication” e n g c h i U of overseas travelling or future job hunting.. Regarding the English learning experiences, Shelly’s family moved back to Taiwan when she is about the age of kindergartener, and then the parents registered Shelly at K school in Taiwan. Thus, Shelly receives her formal education, including the learning of English since then. Yet, Shelly’s English learning takes place not only in the school but also at home. Shelly’s father asked her to memorize every word in 38.

(53) a children’s English dictionary before elementary school, and this activity stopped when she had acquired all the vocabulary. English is never a difficult language to learn for Shelly. There is almost no obstacle that Shelly encounters during kindergarten and elementary school. Shelly described in the interview,. ….English (courses) is easy because I have learned it since little, and I have been to Canada. But I just hate doing homework. It makes me really tired….As. 政 治 大. for English learning, I can pick it up quickly. Teachers always love me because. 立. I get good grades (mostly in English classes)…. (The first interview with Shelly,. ‧ 國. 學. August, 31, 2013). ‧ y. Nat. er. io. sit. When the researcher asks Shelly about her feeling for English courses, she always responds that “It’s just as usual.” When she says that, it means the grades are. al. n. v i n Calso as good as usual. This excerpt a typical attitude that Shelly has h erepresents ngchi U. toward schooling-considering homework as a tiresome routine but still being able to keep top scores. Again, more discussion concerning her responses to the curriculum will be found in the second section. Shelly continues her academic path in K school. Students in this school receive English education from a specialized English program, offering two courses for students from grade one to grade twelve. In general, the students in this program are 39.

(54) equipped with four skills through student-centered practice. It is their aims to develop each individual as critical thinker, independent life-long learner, and effective communicators. More specifically, one of the courses, English Literature, purports to foster students’ ability in appreciating and understanding a variety of fiction and non-fiction texts, and the other, Language Art, intends to enhance students’ ability in grammar construction, various form of writing, oral fluency, vocabulary acquisition, and reading comprehension skills. All English courses are. 政 治 大. divided into four levels: intermediate, advanced, mainstream, and honors. Currently,. 立. Shelly attends the mainstream English classes. Immersing in an English learning. ‧ 國. 學. environment like this, there is no doubt that Shelly possesses a high level of English. Nat. er. io. sit. y. ‧. ability. Evidence is also shown in the interview with Mr. Chen.. ….Shelly does not have difficulties in learning. I did not find any. Other. al. n. v i n students who transfer from theC other in K school or other school have h eprograms ngchi U an adjustment period. However, Shelly’s adjustment period is relatively short because she has the tool. This adjustment period is more about adopting English as a medium of instruction. For those students, English was a subject, but now a tool. If you do not have this tool, you might fail…. (The interview with Mr. Chen, January, 22, 2014). 40.

(55) Mr. Chen’s evaluation of Shelly’s English proficiency is in agreement with Shelly’s own evaluation. Shelly regards English as a tool she had already mastered; transferring to an English-medium environment does not cause her any anxiety. Besides, according to the research notes taken from conversations with Shelly during the break of tutoring hours, Shelly appears to be a good language learner and she is good at using the language to learn new content. For example, Shelly thinks Biology is a little challenging when she was in the secondary school; yet, she is. 政 治 大. quite engaged in the Science class in the international school. She compares the two. 立. courses under different course titles and considers they are actually similar on the. ‧ 國. 學. content level. She described,. ‧ y. Nat. er. io. sit. ….Explaining these concepts in Chinese are more complicated in English. For example, when I see the English word “corrosion”, I know it contains the. al. n. v i n meaning that somethingCishdestroyed slowly. On e n g c h i U the other hand, I did not see this meaning by just looking at the Chinese character. (An informal interview with Shelly on the eighteenth week, January, 8, 2014). This excerpt manifests that Shelly takes advantage of her tool, English, in acquiring content knowledge. On another occasion, the researcher/tutor reviews the school work with Shelly, and there is a new term that is unknown to both of them. 41.

(56) When the researcher/tutor is about to check the dictionary to translate the unknown word into her native language, Chinese, for better comprehension, the attempt is stopped by Shelly. She says, “You’ll know the meaning if you keep reading. The following paragraph will explain it.” From this example, it is clear that Shelly did not rely on her native language to learn things; rather she is certain that the meaning of unknown word exists in the larger context, so she decides to adopt a “whole-context strategy” for reading comprehension instead of a “dictionary strategy”.. 立. 政 治 大. What is more, Shelly is now viewing both Chinese and English as major tools. ‧ 國. 學. to communicate. When it comes to casual conversations with peers on smart phone. ‧. or iPad, she chooses the most convenient typing system to convey the message. y. Nat. er. io. sit. rather than deciding a language that she is more familiar with to use.. Furthermore, concerning Shelly’s language use during the first semester in the. al. n. v i n international school, the researcher C analyzes choices in the diary h e ntheglanguage chi U. reports, it is found that Shelly uses an English term to indicate the new knowledge she learned from the Science class. The following excerpt presents the original language in the diary entry (cf. p50).. Science class lǎo shī gěi wǒ men mián huā táng zuò model,gěi lǎo shī jiǎn chá wán jiù kě yǐ chī diào,rán hòu zài huà yì zhāng tú,gěi tóng xué cāi nǐ zuò de 42.

(57) shì na ge element. (The thirteenth diary of Shelly, December, 6, 2013). According to the above descriptions of Shelly’s English learning and using experiences, she is undoubtedly equipped with optimal English proficiency to learn in an English-medium environment. Bedsides, K school has its own evaluating method to make sure that the English proficiency of the students they are recruiting are qualified to acquire content knowledge through English as a medium of instruction.. 立. 政 治 大. For Shelly, in a nut shell, her high English proficiency, satisfaction of her own. ‧ 國. 學. education, and good social relationship create a smooth start of her first semester in. ‧. the international school, which is enough for her to sense accomplishment as a. er. io. sit. y. Nat. student.. al. n. v i n 4.2. The Second Stage: “NotC Backing I Am Still Awesome” h e noff, gchi U In this section, the researcher will elaborate on Shelly’s attitude toward academic learning in the international school and her responses to the curriculum. First of all, it is not surprised to report that most teenagers go to school only out of their parents’ order and governmental regulations. Shelly is one of such teenager. To a higher degree, Shelly considers going to school a nuisance. Even though the learner continuously express how doing homework and reviewing school subjects 43.

數據

相關文件

(“Learning Framework”) in primary and secondary schools, which is developed from the perspective of second language learners, to help NCS students overcome the

Through study in various knowledge contexts and through engaging in a range of learning activities, students will acquire technological concepts and knowledge and develop

0 allow students sufficient time to gain confidence and the skills of studying in English, allow time for students to get through the language barrier, by going through

(a) Classroom level focusing on students’ learning outcomes, in particular, information literacy (IL) and self-directed learning (SDL) as well as changes in teachers’

Achievement growth in children with learning difficulties in mathematics: Findings of a two-year longitudinal study... Designing vocabulary instructio n

Learning Strategies in Foreign and Second Language Classrooms. Teaching and Learning a Second Language: A Review of

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea. Singapore

個人、社會及人文教育 |英國語文教育| 藝術音樂教育 | STEM 教育 全球意識與文化敏感度 |體驗學習| 接觸大自然